Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to explore whether 25% as the cutoff value of fat infiltration (FI) in multifidus (MF) could be a predictor of clinical outcomes of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) patients.

Methods

A total of 461 patients undergoing posterior lumbar interbody fusion for LSS with 1-year follow-up were identified. After sex- and age-match, 160 pairs of patients were divided into a FI < 25% group and a FI ≥ 25% group according to FI of MF at L4 on preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. Patient-reported outcomes including the visual analog scale scores (VAS) for back pain and leg pain and the Oswestry disability index (ODI) scores were evaluated. Bone nonunion and screw loosening were evaluated by dynamic X-ray.

Results

After matching, there was no significant difference in age, sex, body mass index, fusion to S1, number of fusion levels, osteoporosis, spondylolisthesis, smoking and diabetes. FI ≥ 25% group had significantly higher VAS for back pain, VAS for leg pain and ODI than FI < 25% group at 1-year follow-up. However, there was no significant difference in the change of them from baseline to 1-year follow-up between the two groups. In light of complications, FI ≥ 25% group had a significantly higher rate of bone nonunion than FI < 25% group, whereas there was no significant difference of screw loosening rates between the two groups.

Conclusion

MF FI might be a pragmatic cutoff value to predict bone nonunion in LSS patients, but it has little predictive value on screw loosening and postoperative improvement of symptoms.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13018-022-03186-2.

Keywords: Clinical outcome, Fat infiltration, Lumbar spinal stenosis, Multifidus

Background

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) has been one of the most common causes of surgery with a growƒing burden in an aging population [1]. Although surgical treatment has succeeded in relieving pains of patients, several complications and unabated pain still occur after surgery in LSS patients [2].

Studies have revealed that the paraspinal muscle degeneration, a universal phenomenon among old people, is implicated in multiple degenerative lumbar pathologies [3–5]. Lumbar multifidus (MF) is one of paravertebral muscles, playing an important role in stabilizing lumbar spine. Fat infiltration (FI) is a frequently used indicator to assess the degeneration of muscle composition [5].

Currently, the predictive value of paraspinal muscle morphometry for several surgical disciplines inclusive of metastatic disease, trauma and fracture on image examination is being unearthed [6–8]. Degeneration of MF has been proved to be related to several lumbar diseases including LSS [9–11]. However, the cutoff value of FI has not been established, leading to a poor use in clinical application. Liu et al. attempted to divide patients into two groups by using 25% as the cutoff value. They finally suggested that FI in MF could be a potential predictor of improvement of functional status and symptoms in LSS patient [12]. However, the sample size of the study was relatively small. Besides, the association between FI and surgical complications has not been investigated.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to demonstrate whether 25% as the cutoff value of MF FI could be a predictor of postoperative symptoms and complications of LSS patients.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board, with the requirement for informed consent being waived (M2020496). Hospitalized patients undergoing posterior lumbar interbody fusion for LSS between July 2011 and December 2016 were reviewed. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged ≥ more than 40 years, (2) underwent lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and lumbar computed tomography (CT) within 3 months before the index surgery, (3) underwent follow-up of ≥ 12 months. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) previous spinal surgery, (2) patients with bone tumor, ankylosing spondylitis, diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis or secondary osteoporosis, (3) previous or current hormone therapy and (4) patients with spondylolisthesis (> grade 1) or scoliosis (> 10°). A total of 461 patients were identified.

Patient-reported outcomes

Patient-reported outcomes, including the visual analog scale scores (VAS) for back pain and leg pain and the Oswestry disability index (ODI) scores ranging from 0 to 100, with the highest score indicating the worst disability, were evaluated at baseline and 1-year follow-up. Clinically significant improvement (CSI) in each domain of interest was defined as improvement rate ≥ 50% for VAS-back, improvement rate ≥ 50% for VAS-leg or improvement rate ≥ 40% for ODI [12].

Radiographic evaluation

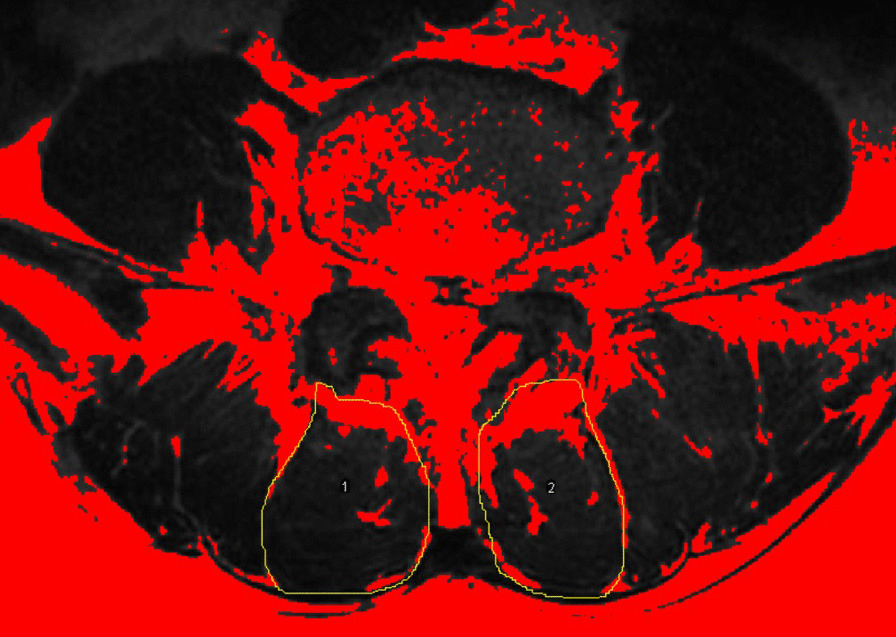

All enrolled patients had undergone preoperative MRI of lumbar area with Signa HDxt 3.0 T (General Electric Company). The fatty infiltration (FI) of bilateral MF was evaluated at the superior end plate level of L4 from T2-weighted images using the thresholding technique in ImageJ software version 1.5 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, Fig. 1) [13, 14]. To test the reliability, all muscular parameters of 20 patients were randomly selected and were measured by two observers independently. After 3 weeks, the same measurements were performed by one observer. The ICCs for both intra-rater and inter-rater reliability were > 0.8.

Fig. 1.

Measurements of paraspinal muscular parameters on axial T2-weighted MRI (a 55-year-old man). Regions of multifidus at L4 level were outlined by yellow lines. Thresholding technique to highlight fatty area (red area)

Segmental fusion status and screw loosening were evaluated by dynamic X-ray after 1-year follow-up by two observers independently. We defined the bone nonunion as (1) there was no continued bone fusion mass at any fusion segment and (2) any motion (greater than 3 mm or 3°) on flexion/extension plain radiographs [15]. Screw loosening was defined when a 1-mm or wider circumferential radiolucent line around the pedicle screw was confirmed on spine radiograph at 1-year follow-up [16]. Observers were blinded to clinical information, and the evaluation of complications was separated from muscular measurements.

Statistical analyses

All enrolled patients were divided into a FI < 25% group and a FI ≥ 25% group according to FI of MF at L4. To reduce the bias, we selected patients with FI ≥ 25% to match to patients with FI < 25% in a 1:1 manner according to age (the difference was less than 3 years) and sex. As a result, 320 patients were selected in this study (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

Previous study has reported that the mean value of MF FI in patients with lumbar diseases was close to 25% [17]. Besides, Peng et al. have revealed that MF FI in 70–79 years group was 25.84% [18]. Moreover, Liu et al. have divided patients into FI < 25% and FI ≥ 25% groups to investigate the relationship between MF FI and surgical prognosis [12]. In terms of level selection, increased FI of paraspinals has been found particularly at L4/5 [19].On the other hand, Crawford et al. have shown that the fat content at L4 best represents that of the entire lumbar region in healthy participants, providing a time-efficient capture of lumbar paravertebral FI [20]. Therefore, in the current study, we considered an FI of MF at L4 ≥ 25% as the exposure and defined it as significant fatty infiltration versus an FI < 25% as insignificant fatty infiltration [12].

The age- and sex-matching process was performed with the case–control matching (CCM) function of SPSS. The Mann–Whitney U test or ANOVA (for continuous data) and Chi-square test (for categorical data) were conducted to determine the statistical difference. Intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated to test the intra- and inter-rater reliability. Statistical significance was set at P value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp).

Results

A total of 461 patients have been received in our study, with an average age of 60 years. The whole patients have been divided into FI < 25% group (n = 235) and FI ≥ 25% group (n = 226). Before CCM, the average age was 58.0 and 62.0 years in FI < 25% and FI ≥ 25% groups, respectively (P < 0.001). There was also a significant difference in sex and osteoporosis between two groups (both P < 0.001). However, VAS for back pain (5.1 vs. 5.4, P = 0.268), VAS for leg pain (5.8 vs. 6.1, P = 0.186) and ODI (41.0 vs. 41.5, P = 0.591) had no significantly difference between the two groups. The data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparisons of clinical data at baseline between MF FI ≥ 25% and FI < 25% groups in complete cohort

| Variable | FI ≥ 25% (n = 226) | FI < 25%(n = 235) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62.0 ± 7.3 | 58.0 ± 7.4 | < 0.001** |

| Sex (male/female) | 69:157 | 116:119 | < 0.001** |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.0 ± 3.4 | 26.1 ± 3.3 | 0.815 |

| Fusion to S1 (no: yes) | 134:92 | 145:89 | 0.533 |

| Number of fusion levels | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 0.937 |

| Osteoporosis (no: yes) | 145:79 | 185:47 | < 0.001** |

| Spondylolisthesis (no: yes) | 123:67 | 121:40 | 0.035* |

| Smoking (no: yes) | 194:32 | 200:35 | 0.823 |

| Diabetes (no: yes) | 189:37 | 201:34 | 0.571 |

| MF FI (%) | 36.3 ± 9.2 | 18.3 ± 4.7 | < 0.001** |

| Baseline | |||

| VAS for back pain | 5.4 ± 2.0 | 5.1 ± 2.2 | 0.268 |

| VAS for leg pain | 6.1 ± 2.1 | 5.8 ± 2.3 | 0.186 |

| ODI | 41.5 ± 18.8 | 41.0 ± 20.3 | 0.591 |

The numbers in bold represented that there was significant difference between the two groups

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Based on CCM, we successfully matched 160 pairs of patients. After CCM, there was no significant difference in age, sex, body mass index (BMI), fusion to S1, number of fusion levels, osteoporosis, spondylolisthesis, smoking and diabetes (all P > 0.15, Table 2). For the baseline data, FI ≥ 25% group had slightly higher VAS for back pain, VAS for leg pain and ODI than FI < 25% group without significant difference (all P > 0.05, Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparisons of clinical data and patient-reported outcomes after case–control matching

| Variable | FI > 25% (n = 160) | FI < 25% (n = 160) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.7 ± 7.0 | 59.9 ± 6.7 | 0.231 |

| Sex (female/male) | 56:104 | 56:104 | 1.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9 ± 3.6 | 26.0 ± 3.4 | 0.929 |

| Fusion to S1 (no:yes) | 93:67 | 100:60 | 0.424 |

| Number of fusion levels | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 0.581 |

| Osteoporosis (no:yes) | 113:47 | 115:45 | 0.805 |

| Spondylolisthesis (no:yes) | 88:48 | 90:36 | 0.244 |

| Smoking (no:yes) | 132:28 | 141:19 | 0.155 |

| Diabetes (no:yes) | 137:23 | 138:22 | 0.872 |

| MF FI (%) | 36.6 ± 9.7 | 18.9 ± 4.5 | < 0.001** |

| Baseline | |||

| VAS for back pain | 5.4 ± 2.0 | 5.3 ± 2.3 | 0.819 |

| VAS for leg pain | 6.0 ± 2.1 | 5.9 ± 2.4 | 0.931 |

| ODI | 41.3 ± 18.6 | 40.6 ± 19.9 | 0.684 |

The numbers in bold represented that there was significant difference between the two groups

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

At 1-year follow-up, FI ≥ 25% group had significantly higher VAS for back pain, VAS for leg pain and ODI than FI < 25% group (2.8 vs. 3.2, P = 0.017; 2.3 vs. 2.8, P = 0.039; 17.1 vs. 21.7, P = 0.010, respectively; Table 3). However, there was no significant difference in the change of them from baseline to 1-year follow-up between FI < 25% and FI ≥ 25% groups (all P > 0.05, Table 3). The proportion achieving CSI with respect to VAS for back pain in FI < 25% group was higher than that in FI ≥ 25% group , but not statistically significant (52.2% vs 48.9%, P = 0.913). Moreover, no significant differences in the proportion achieving CSI of VAS for leg pain (70.0% vs. 58.0%, P = 0.548) and ODI (61.8% vs. 58.5%, P = 0.879) were found between the two groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparisons of the Improvement of Patient-Reported Outcomes At 1-year follow-up After Case–Control Matching

| Variable | FI > 25% (n = 160) | FI < 25% (n = 160) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| At 1-Year Follow-Up | |||

| VAS for back pain | 3.2 ± 2.3 | 2.8 ± 2.2 | 0.017* |

| VAS for leg pain | 2.8 ± 2.4 | 2.3 ± 2.5 | 0.039* |

| ODI | 21.7 ± 15.1 | 17.1 ± 14.1 | 0.010* |

| Change | |||

| Change of VAS for back pain | 2.5 ± 2.7 | 2.5 ± 2.9 | 0.527 |

| Change of VAS for leg pain | 3.2 ± 3.0 | 3.7 ± 3.5 | 0.212 |

| Change of ODI | 17.9 ± 17.7 | 21.0 ± 23.0 | 0.549 |

| Rates of CSI | |||

| Improvement rate of VAS for back pain ≥ 50% | 69:66 | 55:60 | 0.913 |

| Improvement rate of VAS for leg pain ≥ 50% | 55:76 | 34:79 | 0.548 |

| Improvement rate of ODI ≥ 40% | 56:79 | 47:76 | 0.879 |

The numbers in bold represented that there was significant difference between the two groups

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

In light of complications, bone nonunion occurred in 12 patients in FI < 25% group, which was significantly lower than 40 patients in FI ≥ 25% group (P < 0.001; Table 4). Screw loosening had a higher ratio to occur in FI ≥ 25% group than FI < 25% group, whereas there was no significant difference in screw loosening rates between the two groups (41 vs 55, P = 0.073; Table 4). Further, we performed a subgroup analysis according to screw loosening. The rate of bone nonunion was higher in the patients with screw loosening than in those without (41.7% vs. 5.4%, p < 0.001). In the patients without screw loosening (n = 224), the rate of patients with MF FI ≥ 25% in the nonunion group was higher than that in the union group but without significant difference (5.7% vs. 5%, p = 0.824). However, in the patients with screw loosening (n = 96), the nonunion group had a significantly higher rate of MF FI ≥ 25% than the union group (61.8% vs. 14.6%, p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Comparisons of Complications at 1-Year Follow-Up After Case–Control Matching

| Variable | FI > 25% (n = 160) | FI < 25% (n = 160) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone nonunion (yes) | 40 | 12 | < 0.001** |

| Screw loosening (yes) | 55 | 41 | 0.073 |

The numbers in bold represented that there was significant difference between the two groups

**P < 0.01

Discussion

In this study, we found that bone nonunion had a significantly higher risk to occur in FI ≥ 25% group. In accordance with the present results, previous studies have also demonstrated that as fat deposit of paraspinal muscles increased, the incidence of bone nonunion increased [21, 22]. Besides, Choi et al. [23] indicated that muscle cross-sectional area, another indicator of paraspinals degeneration, was also associated with bone nonunion. These findings might corroborate the idea that the degeneration of MF plays an important role in bone union. MF, as the most medial and largest of the paraspinal muscles, can provide most stability to the lumbar segments. Therefore, FI could influence the normal functions of MF and thereby deteriorate the process of bone union [24]. On the other part, previous study revealed significant correlations between FI of paraspinals and vertebral bone marrow fat content [25]. Because osteoblasts and adipocytes share a common precursor in the bone marrow, increased adipogenesis might be associated with decreased osteoblastogenesis [26, 27]. Another hypothesis suggested that high paraspinals FI were detrimental for bone union as it might reduce vascular ingrowth into fusion mass [28].

Further, we found that high FI would affect the bone union in the patients with screw loosening, whereas FI did not have such effect once patients did not occur screw loosening. It suggested that high MF FI might play a secondary role in the bone nonunion. In patients with unsatisfied screw fixation, low MF FI could be a protective factor of bone nonunion, which indicated that a rehabilitation training of paraspinal muscles was instrumental [29]. Previously, Lee et al. [21] quantified the fat content using a subjective semiquantitative scale and proposed that above grade 1 of FI at surgery was a risk factor. Our finding, while preliminary, suggested that 25% could be an available cutoff value to distinguish high-risk group for bone nonunion.

In light of screw loosening, the relationship between MF FI and screw loosening was still controversial. In our study, the incidence of screw loosening was higher in FI ≥ 25% group than in FI < 25% group , but without significant difference. This outcome was contrary to that of Kim et al. who reported that greater FI of MF had significant effects on the S1 screw loosening in 156 patients with degenerative lumbar diseases [30]. In contrast, a retrospective study of 137 degenerative lumbar scoliosis (DLS) patients by Leng et al. [16] demonstrated that FI of MF was irrelevant to screw loosening in corrective surgery, which was consistent with our study. A possible explanation for this might be that the degeneration of paraspinal muscles can affect screw loosening observably only in long level fusion. Leng et al.’s study might support this speculation. They found that degeneration of psoas muscles and erector spinae could affect screw loosening in six- or more-level fusion in corrective surgery for DLS, whereas the four- or five-level fusion had no this influence [16].

Our findings also revealed that the MF FI was not related to postoperative improvement of function status and symptoms of LSS patients. These results were in line with those of previous studies [31]. In a prospective multicenter cohort study, Betz et al. [31] found that fatty degeneration had rarely prognostic value of improvement in symptoms in LSS treatment. Similarly, Bhadresha et al. [32] reported that there was a tendency toward greater improvements between baseline and 12-month follow-up in patients with Goutallier stage 1 or lesser (low FI), but these improvements did not differ significantly. However, contrary findings also exist in the current research [13, 33]. A study based on MRI and 2-year follow-up of patients from Kjersti et al. demonstrated that lower pre-treatment fat infiltration rate predicted greater improvement of pain and ODI [33]. In addition, Wang et al. [13] indicated that preoperative MF FI was significantly correlated with postoperative ODI and ODI improvement. This discrepancy might be attributed to diverse diseases, surgical methods and follow-up durations in studies.

In general, our results could not support the hypothesis of association between FI and the improvement of symptoms. In a community-based study, they also found no association between paraspinal muscles density and the occurrence of low back pain [34]. A possible explanation for this might be that FI may just play a small part in pain. Several muscular reasons including lower muscle strength, muscle atrophy, FI and inflammatory may act together on the occurrence of pain [35].

Limitations

There are some limitations in this study. Firstly, this study was a retrospective study, which might cause the bias. But 320 subjects after case–control matching were included in our study, whose sample size was larger than previous studies. Besides, the methods to distinguish the adipose tissue vary in different studies, leading to a deviation of FI [16], while we applied the threshold technique which can automatically differentiate fat from lean muscles and has a good reliability.

Conclusions

In conclusion, bone nonunion had a significantly higher rate to occur in FI ≥ 25% group. However, there were no differences in the incidence of screw loosening and postoperative improvement in functions and symptoms between FI ≥ 25% and FI < 25% groups.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Representative patients. Fig (a), a 52-year-old man with MF FI < 25% before surgery. Fig (b), a 54-year-old woman with MF FI > 25% before surgery.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- CCM

Case-control matching

- CSA

Cross-sectional area

- CSI

Clinically significant improvement

- CT

Computed tomography

- DLS

Degenerative lumbar scoliosis

- FI

Fat infiltration;

- LSS

Lumbar spinal stenosis

- MF

Multifidus

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ODI

Oswestry Disability Index

- VAS

Visual analog scale

Authors’ contributions

GH, DZ and XL conceived the project and analyzed the data. All authors contributed toward the interpretation and the collection of the data. All authors wrote and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Clinical Cohort Construction Program of Peking University Third Hospital, China National Key Research and Development Program (2018YFB1307700) and the Accurate Diagnosis and Treatment Technology of Bone and Joint Diseases Research.

Availability of data and materials

The data used and analyzed during the current study were available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board, with the requirement for informed consent being waived (M2020496).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Gengyu Han, Da Zou and Xinhang Li contributed equally to this article

References

- 1.Jensen RK, Jensen TS, Koes B, Hartvigsen J. Prevalence of lumbar spinal stenosis in general and clinical populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J. 2020;29(17):2143–2163. doi: 10.1007/s00586-020-06339-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lurie J, Tomkins-Lane C. Management of lumbar spinal stenosis. BMJ. 2016 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beneck GJ, Kulig K. Multifidus atrophy is localized and bilateral in active persons with chronic unilateral low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2012;93(2):300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belavy DL, Armbrecht G, Richardson CA, Felsenberg D, Hides JA. Muscle atrophy and changes in spinal morphology is the lumbar spine vulnerable after prolonged bed-rest? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36(2):137–145. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181cc93e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalichman L, Carmeli E, Been E. The association between imaging parameters of the paraspinal muscles, spinal degeneration, and low back pain. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:2562957. doi: 10.1155/2017/2562957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourassa-Moreau É, Versteeg A, Moskven E, Charest-Morin R, Flexman A, Ailon T, et al. Sarcopenia, but not frailty, predicts early mortality and adverse events after emergent surgery for metastatic disease of the spine. Spine J. 2020;20(1):22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2019.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tee YS, Cheng CT, Wu YT, Kang SC, Derstine BA, Fu CY, et al. The psoas muscle index distribution and influence of outcomes in an Asian adult trauma population: an alternative indicator for sarcopenia of acute diseases. Eur J Trauma Emerg S. 2020;47:1007. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01360-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byun SE, Kim S, Kim KH, Ha YC. Psoas cross-sectional area as a predictor of mortality and a diagnostic tool for sarcopenia in hip fracture patients. J Bone Miner Metab. 2019;37(5):871–879. doi: 10.1007/s00774-019-00986-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faur C, Patrascu JM, Haragus H, Anglitoiu B. Correlation between multifidus fatty atrophy and lumbar disc degeneration in low back pain. BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2019;20:414. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2786-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandelli F, Nüesch C, Zhang Y, Halbeisen F, Netzer C. Assessing fatty infiltration of paraspinal muscles in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: Goutallier classification and quantitative MRI measurements. Front Neurol. 2021;12:656487. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.656487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu HF, Wang GL, Zhou ZJ, Fan SW. Prospective study of long-term effect between multifidus muscle bundle and conventional open approach in one-level posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Orthop Surg. 2018;10(4):296–305. doi: 10.1111/os.12402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Liu Y, Hai Y, Liu T, Guan L, Chen X. Fat infiltration in the multifidus muscle as a predictor of prognosis after decompression and fusion in patients with single-segment degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: an ambispective cohort study based on propensity score matching. World Neurosurg. 2019;128:e989–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W, Sun Z, Li W, Chen Z. The effect of paraspinal muscle on functional status and recovery in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15(1):235. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-01751-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dohzono S, Toyoda H, Takahashi S, Matsumoto T, Suzuki A, Terai H, et al. Factors associated with improvement in sagittal spinal alignment after microendoscopic laminotomy in patients with lumbar spinal canal stenosis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016;25(1):39–45. doi: 10.3171/2015.12.SPINE15805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou D, Muheremu A, Sun Z, Zhong W, Jiang S, Li W. Computed tomography Hounsfield unit-based prediction of pedicle screw loosening after surgery for degenerative lumbar spine disease. J Neurosurg Spine. 2020;32:1–6. doi: 10.3171/2019.11.SPINE19868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leng J, Han G, Zeng Y, Chen Z, Li W. The effect of paraspinal muscle degeneration on distal pedicle screw loosening following corrective surgery for degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2020;45(9):590–598. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyun JK, Lee JY, Lee SJ, Jeon JY. Asymmetric atrophy of multifidus muscle in patients with unilateral lumbosacral radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32(21):E598–602. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318155837b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng X, Li X, Xu Z, Wang L, Cai W, Yang S, et al. Age-related fatty infiltration of lumbar paraspinal muscles: a normative reference database study in 516 Chinese females. Quant Imag Med Surg. 2020;10(8):1590–1601. doi: 10.21037/qims-19-835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooley JR, Walker BF, Ardakani ME, Kjaer P, Jensen TS, Hebert JJ. Relationships between paraspinal muscle morphology and neurocompressive conditions of the lumbar spine: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2018;19(1):351. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2266-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crawford RJ, Filli L, Elliott JM, Nanz D, Fischer MA, Marcon M, et al. Age- and level-dependence of fatty infiltration in lumbar paravertebral muscles of healthy volunteers. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37(4):742–748. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CS, Chung SS, Choi SW, Yu JW, Sohn MS. Critical length of fusion requiring additional fixation to prevent nonunion of the lumbosacral junction. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35(6):E206–211. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181bfa518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katsu M, Ohba T, Ebata S, Haro H. Comparative study of the paraspinal muscles after OVF between the insufficient union and sufficient union using MRI. BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2018;19(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2064-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi MK, Kim SB, Park CK, Malla HP, Kim SM. Cross-sectional area of the lumbar spine trunk muscle and posterior lumbar interbody fusion rate: a retrospective study. Clin Spine Surg. 2017;30(6):E798–803. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlaeger S, Inhuber S, Rohrmeier A, Dieckmeyer M, Freitag F, Klupp E, et al. Association of paraspinal muscle water-fat MRI-based measurements with isometric strength measurements. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(2):599–608. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5631-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sollmann N, Dieckmeyer M, Schlaeger S, Rohrmeier A, Syvaeri J, Diefenbach MN, et al. Associations between lumbar vertebral bone marrow and paraspinal muscle fat compositions-an investigation by chemical shift encoding-based water-fat MRI. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:563. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schellinger D, Lin CS, Hatipoglu HG, Fertikh D. Potential value of vertebral proton MR spectroscopy in determining bone weakness. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(8):1620–1627. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Justesen J, Stenderup K, Ebbesen EN, Mosekilde L, Steiniche T, Kassem M. Adipocyte tissue volume in bone marrow is increased with aging and in patients with osteoporosis. Biogerontology. 2001;2(3):165–171. doi: 10.1023/A:1011513223894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bawa M, Schimizzi AL, Leek B, Bono CM, Massie JB, Macias B, et al. Paraspinal muscle vasculature contributes to posterolateral spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1975) 2006;31(8):891–896. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000209301.15262.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee C-S, Kang K-C, Chung S-S, Park W-H, Shin W-J, Seo Y-G. How does back muscle strength change after posterior lumbar interbody fusion? J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;26(2):163–170. doi: 10.3171/2016.7.SPINE151132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JB, Park SW, Lee YS, Nam TK, Park YS, Kim YB. The effects of spinopelvic parameters and paraspinal muscle degeneration on S1 screw loosening. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2015;58(4):357–362. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2015.58.4.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Betz M, Burgstaller JM, Held U, Andreisek G, Steurer J, Porchet F, et al. Influence of paravertebral muscle quality on treatment efficacy of epidural steroid infiltration or surgical decompression in lumbar spinal stenosis-analysis of the lumbar spinal outcome study (LSOS) data: a Swiss prospective multicenter cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1975) 2017;42(23):1792–1798. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhadresha A, Lawrence OJ, McCarthy MJ. A comparison of magnetic resonance imaging muscle fat content in the lumbar paraspinal muscles with patient-reported outcome measures in patients with lumbar degenerative disk disease and focal disk prolapse. Global Spine J. 2016;6(4):401–410. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1583290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Storheim K, Berg L, Hellum C, Gjertsen Ø, Neckelmann G, Espeland A, et al. Fat in the lumbar multifidus muscles - predictive value and change following disc prosthesis surgery and multidisciplinary rehabilitation in patients with chronic low back pain and degenerative disc: 2-year follow-up of a randomized trial. BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2017;18(1):145. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1505-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalichman L, Hodges P, Li L, Guermazi A, Hunter DJ. Changes in paraspinal muscles and their association with low back pain and spinal degeneration: CT study. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(7):1136–1144. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1257-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noonan AM, Brown SHM. Paraspinal muscle pathophysiology associated with low back pain and spine degenerative disorders. JOR Spine. 2021;4(3):e1171. doi: 10.1002/jsp2.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Representative patients. Fig (a), a 52-year-old man with MF FI < 25% before surgery. Fig (b), a 54-year-old woman with MF FI > 25% before surgery.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and analyzed during the current study were available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.