Abstract

We developed a biocatalyst by cloning the styrene monooxygenase genes (styA and styB) from Pseudomonas fluorescens ST responsible for the oxidation of styrene to its corresponding epoxide. Recombinant Escherichia coli was able to oxidize different aryl vinyl and aryl ethenyl compounds to their corresponding optically pure epoxides. The results of bioconversions indicate the broad substrate preference of styrene monooxygenase and its potential for the production of several fine chemicals.

Very few bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas that are able to degrade styrene have been studied (1, 9, 13, 17). Styrene degradation can occur through two different routes: the first involves the oxidation of the side chain and the second involves the oxidation of the aromatic ring (3, 12, 15, 16). Recently, we localized and characterized the genes responsible for the oxidation of styrene to phenylacetic acid in Pseudomonas fluorescens ST. Sequence analysis and biotransformation experiments allowed the identification of the functions of the styA and styB genes, which encode the styrene monooxygenase responsible for the formation of styrene oxide (1). In addition, we have verified that the product was (S)-styrene oxide in optically pure form. This outcome has stimulated our interest in the development of a biocatalyst for the production of different chiral epoxides, whose formation is interesting since they are valuable building blocks in the manufacture of optically active compounds (4).

Biocatalyst construction.

In order to design a biocatalyst for the production of optically pure epoxides, the 3.0-kb PstI-EcoRI region identified from the genomic library of P. fluorescens ST and cloned in pTZ19R, leading to pTPE30, was investigated (1, 9). We amplified by PCR a fragment of plasmid pTPE30 spanning the region from nucleotide 39 upstream to nucleotide 1947 downstream of styA and styB, which encode styrene monooxygenase, using the synthetic oligonucleotides OLI1 (5′-TTTCCTTTTTTGCTGCTGGTC-3′) and OLI2 (5′-TTTTGTTGTTTTGTTCGTTGC-3′). The 1.9-kb amplified fragment was cloned in the pTZ18R vector, yielding plasmid pTAB19. Then, we transformed Escherichia coli JM109 with pTAB19 carrying the styA and styB genes, which led to the recombinant strain JM109(pTAB19), which was used for the bioconversion of different substrates.

Biotransformation products obtained with styrene monooxygenase of P. fluorescens ST.

To investigate the substrate preference of the enzyme, biotransformation experiments were performed with different substrates. Cells of E. coli JM109(pTAB19) were grown with shaking at 37°C on mineral medium (M9) supplemented with 20 mM glucose, 1 mM thiamine, and 200 μg of ampicillin per ml. When the culture reached an A600 of 0.5, transcription from the lacZ promoter was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM. Then, cells were harvested and resuspended to an A600 of 2.0 in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) containing 20 mM glucose. Cell suspensions (100 ml in 500-ml flasks) were incubated at 30°C on a rotary shaker in the presence of the substrates, supplied at 0.5 g/liter. After 4 h, the culture samples were extracted with three equal amounts of ethyl acetate. The solvent was evaporated under vacuum, unless volatile compounds were extracted, in which case the solvent was evaporated at atmospheric pressure. Compounds were then purified by standard chromatography on silica gel with a hexane-ethyl acetate mixture (50:50).

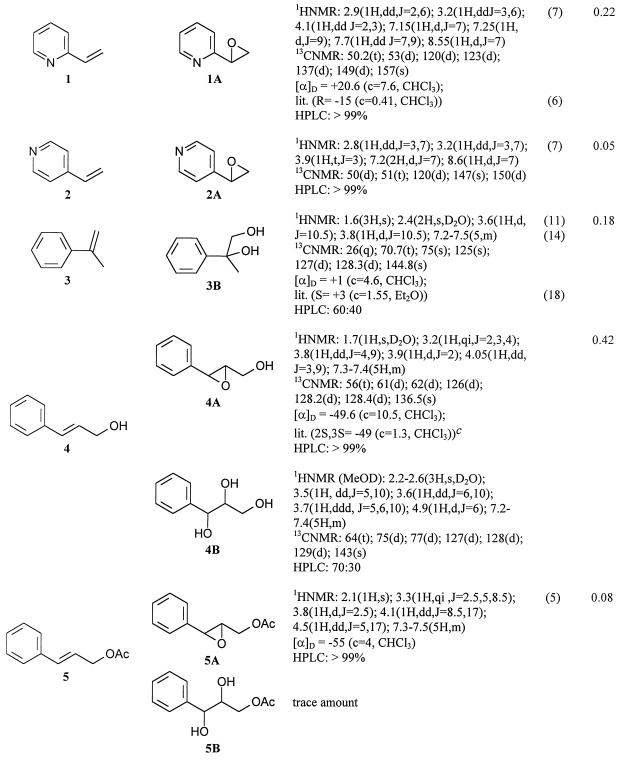

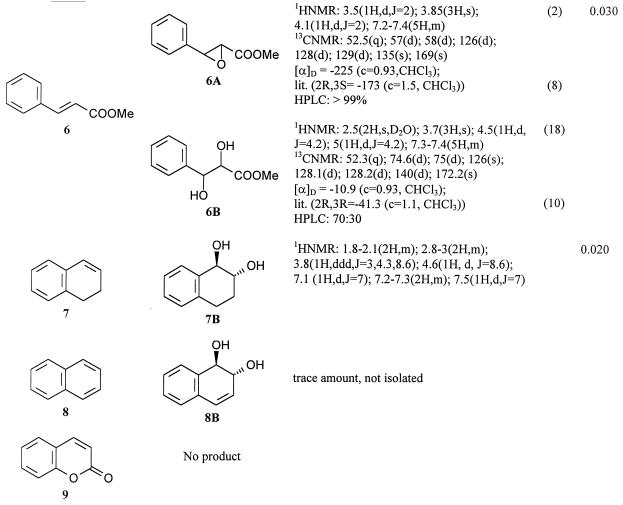

The transformation of three groups of compounds was investigated: vinyl aromatic derivatives (Table 1, substrates 1 and 2), disubstituted ethylenes conjugated with a benzene ring (Table 1, substrates 3 to 6), and cyclic disubstituted ethylenes conjugated with a benzene ring (Table 1, substrates 7 to 9). All these compounds, except substrate 9, gave biotransformation products. Yields and products are correlated with the structures. In particular, vinyl and 1,2-disubstituted ethylenes gave the corresponding epoxides as their main products, while compounds 3 and cyclic double bonds gave their corresponding hydrolyzed derivatives. Some other structural characteristics seem to be important in favoring microbial oxidation, the most important being the absence of an electron withdrawing group conjugated to the double bond and the preference for acyclic double bonds. These characteristics affected mainly yields that were decreased by their missing electron withdrawing groups. Consequently, yields were high for compounds 1, 3, 4, and 5 (0.3 to 0.5 g/liter); conversely, compound 8 gave only a trace amount of product and compound 9 was not transformed. Even if yields were not optimized, compounds 1 and 4 were completely transformed in 4 h. Common problems presented by many experiments were the isolation and purification of the products. In fact, epoxides are frequently volatile and direct evaporation of the extraction or chromatographic solvents caused an important decrease in isolated products (Table 1, substrates 1, 2, and 5). However, careful evaporation of the solvents at atmospheric pressure without overheating allowed for good recovery of the products.

TABLE 1.

NMR characteristics and optical activities of bioproducts obtained with styrene monooxygenase from P. fluorescens ST

Spectra with CDCl3 were recorded at 300 MHz. Chemical shifts are referenced to those of tetramethylsilane. Abbreviations: qi, quintet; c, concentrations; lit., literature; MeOD, methanol-d; coupling constants (J) are in hertz.

Yields were not optimized.

Sold by Fluka Chemie AG.

Identification and characterization of the epoxides.

From the biotransformation experiments we obtained five epoxides: 1A, 2A, 4A, 5A, and 6A (Table 1). They are all known compounds, and their identification was made by comparison. Where possible, more nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data have been added. Optical purity was measured by two means: by comparison of [α]D values with reported values and by use of a chiral-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) column (CHIRALCEL OD-H). All the epoxides seemed to be optically pure, and the known epoxides also had the expected absolute configuration. These data in addition to the already determined optical purity of the styrene oxide confirm the geometric selectivity of the enzyme.

Identification and characterization of the 1,2-diols.

The only by-products obtained from the epoxides were the hydrolyzed products. These were 1,2-diols, and they represented trace by-products from the bioconversions of compounds 4, 5, and 6; however, they were the only isolated products for compounds 3 and 7. Compound 8 showed trace amounts only of the diol. The optical purity depended on the substrate, and results demonstrated that hydrolysis is not stereoselective. In fact, both with purified products, with which a comparison with published [α]D values was possible (products 3B and 6B), and with an unpurified mixture (product 4B), with which the only data came from chiral HPLC, the diols were always optically impure, but the purity level varied from 20% (product 3B) to 40% (product 6B).

Conclusions.

The reaction products obtained in bioconversion experiments performed with a recombinant strain producing styrene monooxygenase from aryl ethenyl compounds can be grouped into epoxides and hydrolyzed products. All the epoxides were optically pure and had the same absolute configuration. The epoxide yields depended on the structure characteristics; in particular, they were high for acyclic compounds without electron withdrawing groups. In two cases (Table 1, substrates 3 and 7) the only products were the 1,2-diols and they did not maintain the optical purity predicted for the epoxide intermediates.

In this work we have demonstrated that E. coli JM109(pTAB19) carrying styrene monooxygenase genes cloned from P. fluorescens ST converts aryl ethenyl compounds to the corresponding epoxides in optically pure forms and with good yields. Thus, the engineered E. coli strain shows great promise as an efficient biocatalyst for the production of important chiral building blocks.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the CNR, MURST-CNR Biotechnology Program L.95/95, and the MURST Research Program of National Relevance—1997.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beltrametti F, Marconi A M, Bestetti G, Colombo C, Galli E, Ruzzi M, Zennaro E. Sequencing and functional analysis of styrene catabolism genes from Pseudomonas fluorescens ST. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2232–2239. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2232-2239.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conan A, Sibille S, Perichon J. Metal exchange between an electrogenerated organonickel species and zinc halide: application to an electrochemical, nickel-catalyzed Reformatsky reaction. J Org Chem. 1991;56:2018–2024. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu M H, Alexander M. Biodegradation of styrene in samples of natural environments. Environ Sci Technol. 1992;26:1540–1544. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furuhashi K. Biological routes to optically active epoxides. In: Collins A N, Sheldrake G N, Crosby J, editors. Chirality in industry. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1992. pp. 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghelfi F, Grandi R, Pagnoni U M. Regiospecific conversion of α,β-epoxy acetates to 3-chloro-2-hydroxy acetates. Gazz Chim Ital. 1995;125:215–217. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imuta M, Kawai K, Ziffer H. Product sterospecificity in the microbial reduction of α-haloaryl ketones. J Org Chem. 1980;45:3352–3355. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kloc K, Kubicz E, Mlochowski J. A novel approach to functionalization of azines. Oxiranyl and thiiranyl derivatives of pyridine, quinoline and isoquinoline. Heterocycles. 1984;22:2517–2522. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Legters J, Thijs L, Zwanenburg B. A convenient synthesis of optically active 1H-aziridine-2-carboxylic acids (esters) Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:4881–4884. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marconi A M, Beltrametti F, Bestetti G, Solinas F, Ruzzi M, Galli E, Zennaro E. Cloning and characterization of styrene catabolism genes from Pseudomonas fluorescens ST. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:121–127. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.121-127.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthews B R, Jackson W R, Jacobs H A, Watson K G. Synthesis of aryl carbohydrate synthons and 2,3-dihydroxypropanoic derivatives of high optical purity. Aust J Chem. 1990;43:1195–1214. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakajima M, Tomioka K, Iitaka Y, Koga K. Highly enantioselective dihydroxylation of olefins by osmium tetroxide with chiral diamines. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:10793–10806. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nöthe C, Hartmans S. Formation and degradation of styrene oxide stereoisomers by different microorganisms. Biocatalysis. 1994;10:219–225. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panke S, Witholt B, Schmid A, Wubbolts M G. Towards a biocatalyst for (S)-styrene oxide production: characterization of the styrene degradation pathway of Pseudomonas sp. strain VLB120. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2032–2043. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.6.2032-2043.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedragosa-Moreau S, Archelas A, Furstoss R. Microbiological transformations. 32. Use of epoxide hydrolase mediated biohydrolysis as a way to enantiopure epoxide and vicinal diols: application to substituted styrene oxide derivatives. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:4593–4606. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srivastava K C. Biodegradation of styrene by Thermophilic bacillus isolates. In: Copping L G, Martin R E, Picket J A, Buck E C, Bunch A W, editors. Opportunities in biotransformations. London, England: Elsevier Applied Science; 1990. pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Utkin I B, Yachimov M M, Matveeva L N, Kozlyak E I, Rogozhin I S, Solomon Z G, Bezborodov A M. Degradation of styrene and ethylbenzene by Pseudomonas species Y2. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;77:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Velasco A, Alonso S, Garcia J L, Perera J, Diaz E. Genetic and functional analysis of the styrene catabolic cluster of Pseudomonas sp. strain Y2. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1063–1071. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1063-1071.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitman C P, Craig J C, Kenyon G L. Synthesis, chioptical properties and absolute configuration of α-phenylglicidic acid. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:1183–1192. [Google Scholar]