Abstract

The corneal endothelium has a crucial role in maintaining a clear and healthy cornea. Corneal endothelial cell loss occurs naturally with age; however, a diagnosis of glaucoma and surgical intervention for glaucoma can exacerbate a decline in cell number and impairment in morphology. In glaucoma, the mechanisms for this are not well understood and this accelerated cell loss can result in corneal decompensation. Given the high prevalence of glaucoma worldwide, this review aims to explore the abnormalities observed in the corneal endothelium in differing glaucoma phenotypes and glaucoma therapies (medical or surgical including with new generation microinvasive glaucoma surgeries). Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) is increasingly being used to manage corneal endothelial failure for glaucoma patients and we aim to review the recent literature evaluating the use of this technique in this clinical scenario.

1. Introduction

Glaucoma is a group of conditions with varying pathophysiological processes, which cause progressive optic neuropathy associated with characteristic structural damage to the optic nerve and associated visual field loss [1]. The condition can be caused by various pathophysiological processes. Worldwide, glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide with a global prevalence of 3.54% in people aged 40–80 years with the highest prevalence being in Africa [2].

Corneal endothelial abnormalities, including a reduction in cell count and morphology, have been detected in glaucoma patients [3]. The corneal endothelium is a monolayer of hexagonal cells, which plays a critical role in regulating corneal hydration and thus transparency [4]. The cells are highly interdigitated and possess apical junctional complexes that, together with abundant cytoplasmic organelles, including mitochondria, are indicative of their crucial role in active fluid transport [5]. The abnormal endothelial changes observed in glaucoma are due to multiple influences including the intraocular pressure (IOP), aqueous humour abnormalities, medication use, and surgical interventions [3]. This review article aims to describe the endothelial changes seen in glaucoma and the role Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) has in managing corneal endothelial cell loss in glaucoma patients.

In preparing this article, electronic database searches were performed for English publications using the following search terms; glaucoma (including different types of glaucoma), glaucoma surgery (including different types of glaucoma surgery), glaucoma medication (including different types of glaucoma topical therapy), corneal endothelium, and Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). The databases analysed included Medline, Embase, ClinicalTrials.gov, and PubMed. From the searches, all articles pertaining to the relevant topic were included in this review.

1.1. Assessment of the Corneal Endothelium

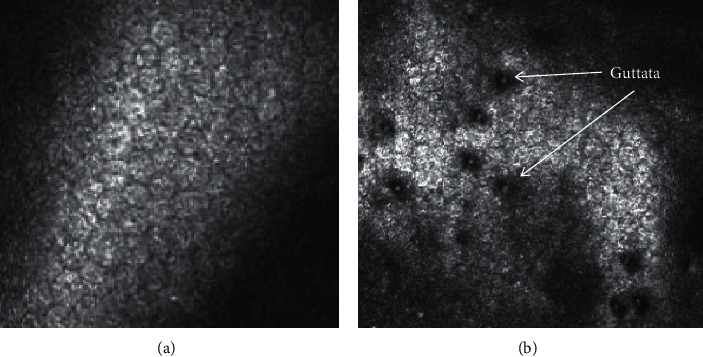

Slit-lamp biomicroscopy can detect macroscopic changes in the corneal endothelium and corneal endothelial diseases, such as Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD). Precise examination of corneal endothelial cell density (ECD) or cell count can be evaluated using, most commonly, specular microscopy or in vivo confocal microscopy (see Figure 1). Endothelial density is defined as the number of cells present in a 1 mm2 area.

Figure 1.

Confocal microscopy of corneal endothelial cells. (a) Normal endothelial cells with a regular hexagonal shape. (b) Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy shows a loss of defined hexagonal shape, increased cell size, and the formation of guttata (as labelled).

1.2. Endothelium and Ageing

As mentioned, the corneal endothelium is a monolayer of hexagonal cells which maintain homeostasis of corneal hydration and transparency [4]. It sits upon a collagen basement membrane called Descemet's membrane. At birth, the Descemet's membrane is 3 µm thick, but this increases with age to an average of 13 µm at 70 years of age.

Corneal transparency is maintained by the active transport of ions across Na+/K+ ATPase pumps [6]. These pumps continually function to preserve the clarity of the cornea even if the IOP within the anterior chamber rises [7]. The integrity of the corneal endothelial monolayer is critical in maintaining this physiological function. The average corneal ECD during adulthood is 2500 cell/mm2, but natural ageing results in both the deterioration in number and morphology of these cells, including cell size and pleomorphism (loss of hexagonal shape) [8–10]. The rate of cell loss is constant throughout life at a rate of approximately 0.6% per year after the age of 18 [11]. This cell loss increases the permeability of the endothelial barrier and reduces its ability to pump fluid out of the corneal stroma and maintain corneal transparency [12]. Corneal endothelial cells show limited replicative ability in vivo [13].

Additionally, the ability of the Na+/K+ ATPase pumps deteriorates with age, decreasing from 32 µamps.cm−2 in people aged 60 years old to 22 µamps.cm−2 in those aged 90 (natural variation is ±6 µamps.cm−2) [14]. These age-related changes are well documented in the literature. Studies have reported that as the morphology of the corneal endothelial monolayer alters with age, it loses its barrier permeability as a result of a lower resistance at the intracellular junctions of the apical cell membranes [15]. Carlson et al. [16] reported in a study of corneas aged 5–79 years old that the number of hexagonal cells significantly decreased with age, but the number of pentagonal and heptagonal cells increased simultaneously [16]. In addition, they observed a 23% increase in endothelial permeability to fluorescein with age but found no differences in corneal thickness or pump rate. The flow rate of aqueous also remained stable. The authors concluded that as the cell morphology altered with age, the cell barrier became more permeable [16].

Age-related loss and changes of the corneal endothelium usually do not have much clinical relevance unless further cell loss is encountered in diseases such as FECD or surgical intervention. In these cases, the cell loss eventually overwhelms the ability for the corneal endothelium to maintain homeostasis leading to irreversible corneal oedema and blindness [12].

1.3. Influence of the Aqueous Humour on Corneal Endothelial Cells

The biological mechanisms responsible for the gradual loss of corneal endothelial cells are likely multifactorial including environmental, hormonal, and immune responses which may be responsible for cell migration, senescence, and apoptosis/necrosis of cells within the anterior segment during normal ageing [17]. As mentioned, corneal endothelial cells display limited proliferative capacity, although this is lower in older donors compared to younger ones [18]. A study on donor corneas also demonstrated that the length of the G1 phase of the cell cycle in corneal endothelial cells is longer in older donors (50 years) compared to younger donors (30 years) [13]. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) may be partly responsible for this as it reportedly inhibits degradation of the G1-phase inhibitor, p27kip1, thus preventing the cells from entering into S-phase [19].

The anterior chamber and aqueous humour have immunosuppressive effects that permit inflammatory mediators and cells to circulate within the eye [20]. TGF-β2 [21] and α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone [22] are the dominant immunosuppressive molecules within the aqueous humour. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β2 is known to be present within aqueous humour in normal eyes, which is in direct contact with the corneal endothelium [23]. Trivedi et al. demonstrated that significantly more TGF-β2 is present in the aqueous of older eyes without glaucoma [24].

Additional levels of inflammatory cytokines within the aqueous humour such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-1, and interferons (IFNs) are known to increase with age [25]. In vitro, they have been shown to induce apoptosis in corneal endothelial cells [25]. Intraocular surgery, such as cataract surgery, which is usually performed on older patients, has also been shown to increase cytokine levels associated with inflammation and apoptosis including interleukins, TNF-α, IFN-γ, TGF-β, and monocyte chemo-attractant protein-1 (MCP-1) [26, 27]. Cataract surgery can also lead to long-term alterations of the intraocular microenvironment in normal, glaucomatous [28], and FECD eyes [29].

2. Changes in the Corneal Endothelium Parameters in Glaucoma

Research has shown that TGF-β plays a crucial role in the aetiology of glaucoma, with significantly elevated levels identified in the anterior chamber of glaucomatous eyes [30]. TGF-β is a key mediator of fibrosis in all organs [31], through the excess production of extracellular matrix proteins including collagens and fibronectin [32, 33]. In addition, fibroblasts transform into highly contractile myofibroblasts, as demonstrated by the expression of alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) [34–36] or mesenchymal transformation in endothelial cells [37]. Collectively, these changes result in cellular and molecular changes in the trabecular meshwork causing a reduction of outflow facility and hence raised IOP [38].

A reduction in the endothelial cell count has been demonstrated in different types of glaucoma. Three hypotheses have been formulated for this: damage from direct compression of the corneal endothelium because of higher IOP; alteration of both the corneal endothelial cell layer and the trabecular meshwork in patients with glaucoma (e.g., due to TGF-β); and glaucoma medication toxicity [39]. The relevance of endothelial cell loss in glaucoma is important to consider if patients are to undergo intraocular surgery.

Interestingly, in 1997, Gagnon et al. reported that despite the reduction in cell numbers, the morphology of corneal endothelial cells (including the percentage of hexagonal cells and coefficient of variation in cell area) did not differ significantly when different types of glaucoma patients were compared to controls [39]. Whilst increased intraocular pressure had been associated with deceased corneal endothelial cell density, no significant correlation between cell density and duration of the glaucoma has been identified [39, 40]. Table 1 provides a summary of corneal endothelial density changes in different forms of glaucoma.

Table 1.

Corneal endothelial densities in different forms of glaucoma.

| Control mean (cells/mm2) | Control SD (cells/mm2) | No. controls | Cases mean (cells/mm2) | Cases SD (cells/mm2) | No. of cases | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ocular Hypertension | |||||||

| Baratz et al., 2006 [70] | 2415 | 300 | 21 | 2331 | 239 | 26 | 0.6 |

| Chawla et al., 2021 [71] | 2509.1 | 298.5 | 91 | 2559.8 | 268.2 | 8 | 0.588 |

|

| |||||||

| All forms of glaucoma | |||||||

| Gagnon et al., 1997 [39] | 2560 | 306 | 52 | 2154 | 419 | 102 | <0.0001 |

| Novak Stroligo et al., 2010 [68] | 2528 | 306 | 100 | 2148 | 317 | 100 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||||

| Acute PACG | |||||||

| Setala et al., 1979 [43] | 2392 | 346 | 25 | 2161 | 633 | 25 | N/A |

| Bigar et al., 1982 [44] | 2243 | N/A | 20 | 1534 | N/A | 20 | 0.002 |

| Malaise-Stals et al., 1984 [45] | 2398 | 380 | 174 | 1640 | N/A | 44 | N/A |

| Chen et al., 2012 [47] | 2559 | 50 | 50 | 2271 | 80 | 40 | 0.002 |

| Sihota et al., 2003 [46] | 2461 | 321 | 30 | 1597 | 653 | 30 | <0.001 |

| Verma et al., 2018 [50] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2504.0 | 558.1 | 74 | N/A |

|

| |||||||

| Subacute ACG | |||||||

| Sihota et al., 2003 [46] | 2461 | 321 | 30 | 2396 | 271 | 30 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| PACG-unspecified | |||||||

| Gagnon et al., 1997 [39] | 2560 | 306 | 52 | 2000 | 585 | 30 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||||

| PACS | |||||||

| Varadaraj et al., 2017 [51] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2676.8 | 270.0 | 466 | N/A |

| Verma et al., 2018 [50] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2582.0 | 472.8 | 51 | N/A |

|

| |||||||

| CACG | |||||||

| Tham et al., 2006 [49] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2271.7 | 312.9 | 39 | N/A |

| Chen et al., 2012 [47] | 2559 | 50 | 50 | 2379 | 50 | 44 | 0.316 |

| Sihota et al., 2003 [46] | 2461 | 321 | 30 | 2229 | 655 | 30 | <0.001 |

| Varadaraj et al., 2017 [51] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2681.2 | 275.7 | 127 | N/A |

| Verma et al., 2018 [50] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2523.8 | 406.8 | 234 | N/A |

| Chawla et al., 2021 [71] | 2509.1 | 298.5 | 91 | 2378.2 | 677.9 | 13 | 0.588 |

|

| |||||||

| ACG Unspecified | |||||||

| Novak Stroligo et al., 2010 [68] | 2528 | 306 | 100 | 2113 | 243 | 24 | N/A |

|

| |||||||

| NTG | |||||||

| Lee et al., 2015 [52] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2380 | 315.4 | 30 | N/A |

| Cho et al., 2009 [40] | 2723.6 | 300.6 | 91 | 2696.7 | 303.9 | 87 | 1 |

| Chawla et al., 2021 [71] | 2509.1 | 298.5 | 91 | 2420.6 | 515.7 | 19 | 0.588 |

|

| |||||||

| HTG | |||||||

| Gagnon et al., 1997 [39] | 2560 | 306 | 52 | 2226 | 311 | 55 | <0.0001 |

| Cho et al., 2009 [40] | 2723.6 | 300.6 | 91 | 2370.5 | 392.3 | 49 | <0.001 |

| Lee et al., 2015 [52] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2530 | 320.4 | 28 | N/A |

| Yu et al., 2019 [72] | 2959 | 236 | 60 | 2757 | 262 | 60 | <0.001 |

| Chawla et al., 2021 [71] | 2509.1 | 298.5 | 91 | 2517.9 | 245.3 | 39 | 0.588 |

|

| |||||||

| ACG Unspecified | |||||||

| Knorr et al., 1991 [59] | 2302 | 394 | 4432 | 1812 | 297 | 123 | <0.001 |

| Seitz et al., 1995 [60] | 2372 | 276 | 33 | 2214 | 251 | 16 | N/A |

| Inoue et al., 2003 [61] | 2362 | 327 | 30 | 2337 | 407 | 19 | N/A |

| Wali et al., 2009 [62] | 2460 | N/A | N/A | 2483 | 511.2 | 78 | N/A |

| Zheng et al., 2011 [63] | 2738.7 | 233.3 | 27 | 2240.7 | 236.6 | 27 | <0.0001 |

| Wang et al., 2012 [64] | 2562 | 18 | 20 | 2505 | 284 | 7 | N/A |

|

| |||||||

| XFS and senile cataract | |||||||

| Quiroga et al., 2010 [65] | 2482 | N/A | 356 | 2315 | N/A | 61 | 0.002 |

| Tomaszewski et al., 2014 [66] | 2503 | 262 | 84 | 2297 | 359 | 68 | 0.0008 |

| Bozkurt et al., 2015 [67] | 2363 | 229.3 | 51 | 2299.5 | 213.9 | 33 | 0.48 |

| PXG and senile cataract | |||||||

| Tomaszewski et al., 2014 [66] | 2503 | 262 | 84 | 2241 | 363 | 65 | 0.000005 |

| Bozkurt et al., 2015 [67] | 2363 | 229.3 | 51 | 2199.5 | 176.8 | 19 | 0.02 |

|

| |||||||

| PXG | |||||||

| Knorr et al., 1991 [59] | 2302 | 394 | 4432 | 1482 | 267 | 59 | <0.001 |

| Seitz et al., 1995 [60] | 2372 | 276 | 33 | 2014 | 254 | 69 | N/A |

| Inoue et al., 2003 [61] | 2362 | 327 | 30 | 2332 | 336 | 7 | N/A |

| Wali et al., 2009 [62] | 2460 | N/A | N/A | 2438 | 503.4 | 48 | N/A |

| Novak Stroligo et al., 2010 [68] | 2528 | 306 | 100 | 2024 | 254 | 16 | <0.0001 |

| Wang et al., 2012 [64] | 2562 | 18 | 20 | 2186 | 2 | 13 | N/A |

| Chawla et al., 2021 [71] | 2509.1 | 298.5 | 91 | 2392.2 | 258.4 | 12 | 0.588 |

|

| |||||||

| Juvenile Open Angle Glaucoma | |||||||

| Urban et al., 2015 [73] | 2955.5 | N/A | 33 | 2639.5 | N/A | 66 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||||

| Congenital glaucoma | |||||||

| Guigou et al., 2008 [74] | 3470 | 357 | 401 | 2922 | 553 | 69 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Congenital and secondary juvenile glaucoma | |||||||

| Wenzel et al., 1989 [75] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2780 | N/A | 20 | N/A |

SD, standard deviation; PACG, primary angle closure glaucoma; PACS, primary angle closure suspect; CACG, chronic angle closure glaucoma; NTG, normal tension glaucoma; XFS, pseudoexfoliation syndrome; PXG, pseudoexfoliation glaucoma; HTG, high tension primary open angle glaucoma.

2.1. Angle Closure Glaucoma

Angle closure glaucoma is caused by obstruction of the trabecular meshwork by iris tissue, which prevents the drainage of aqueous humour and therefore a rise in IOP in the eye, which often results in optic nerve damage [41]. Corneal endothelial cell loss has been frequently reported after acute angle closure glaucoma (AACG) [42–48] and chronic angle closure glaucoma (CACG) [46, 49]. Multivariate analysis for AACG found that duration of the acute attack was the only factor independently associated with reduced corneal ECD (p < 0.001) [47]. As demonstrated in a study which analysed AACG patients into two groups, an AACG attack was less than 72 hour durations or more than 72 hours duration [46]. Mean endothelial cell count in eyes which had a shorter duration (<72h) was 2016 ± 306 cells/mm2 compared to 759 ± 94 cells/mm2 in those who had AACG for more than 72 hours (p < 0.001) [46]. Two more recent studies which evaluated the cell count and morphological characteristics of corneal endothelial cells revealed no clinically significant differences across the angle closure disease spectrum (primary angle closure suspect, primary angle closure glaucoma, and previous acute angle closure glaucoma) [50, 51].

2.2. Open Angle Glaucoma

High tension primary open angle glaucoma (HTG) patients have a raised IOP despite an anatomically unoccluded angle, which results in optic nerve damage. In normal tension glaucoma (NTG), patients demonstrate optic nerve damage despite having a normal intraocular pressure and an open angle. Research demonstrates that there is a reduction in corneal endothelial cell density in HTG; however, the limited analyses of these changes when compared to NTG present conflicting findings [40, 48, 52]. One group found comparable cell counts between NTG and HTG patients: 2,343 ± 394 and 2,326 ± 231 cells/mm2, respectively [48]. Whilst others have reported significantly lower endothelial cell counts in NTG versus HTG patients (2,380.0 ± 315.4 vs. 2,530.0 ± 320.4 cells/mm2, p = 0.04), that is 6.3% less in NTG(54). Lee et al. postulated that in NTG a hypoperfusion mechanism accounted for both progressive optic neuropathy and endothelial cell density reduction [52].

Cho et al. found that the patients with HTG had a significantly lower endothelial cell density than controls (p < 0.001), but NTG patients had a similar cell density compared to controls [40]. The benefit of the Cho et al.'s study was that patients had no previous history of treatment with glaucoma medications. Analysis of 18,665 donor corneas received at the Lion's Eye Institute demonstrated that a past ocular history of glaucoma (in 2.7%) did not significantly affect endothelial cell density (p = 0.094), although the type of glaucoma was not specified [53].

2.3. Pseudoexfoliative Glaucoma

Pseudoexfoliative glaucoma (XFG) is the most common cause of open angle glaucoma worldwide [54, 55]. It is characterized by deposition of pathological greyish-white extracellular fibrillar protein components (PEX material) in multiple ocular tissues which is comprised of constituents of the basement membrane and elastic fibre components [56]. Deposition of this PEX material in the trabecular meshwork obstructs aqueous outflow and almost 50% of pseudoexfoliation syndrome (XFS) patients will ultimately develop XFG in their lifetime [57]. Electron microscopy has revealed large clumps of pseudoexfoliation material adhering to the corneal endothelium and this becomes incorporated into the posterior Descemet's membrane [58]; these may lead to early corneal endothelial decompensation. Patients with XFS and/or XFG have been consistently found in multiple studies to have lower corneal endothelial cell density than controls [59–68]. However, multiple groups have demonstrated that there is no significant difference between the endothelial cell density between patients with XFS alone compared to XFG [66].

Comparison of cell densities in all cell layers of the cornea have been found to be significantly lower in XFS eyes compared to age matched controls [63]. A Japanese study found a higher degree of pleomorphism and polymegathism in PEX eyes compared to control eyes, with the coefficient of variation of the cell area being significantly higher and the percentage of hexagonal cells was significantly lower in XFS [63]. Miyake et al. also demonstrated similar findings [69]; however, this was in contrast to another Japanese population [61] and in other regional studies in which there was no significant difference found in these coefficients of variation of cell size and frequency of hexagonality between XFS and control cataract patients: Paraguay population [65], Turkish population [67], and Chinese population [64]

3. Glaucoma Medications and Corneal Endothelium

Kwon et al. analysed the effect of topical medications used to treat glaucoma on the corneal endothelium in 134 donor corneas at the Lion's Eye Institute. No statistically significant reduction of ECD in patients on glaucoma medication was found. The mean ECD for donors not on glaucoma medication and pooled donors on glaucoma medication was 2561 ± 348 and 2516 ± 320 cells/mm2, respectively (p = 0.42) [76]. Analysis of ECD in patients on the ocular hypertensive treatment study (OHTS) demonstrated there was no statistically significant difference between those who had been observed for six years (n = 21) compared to those treated with any topical medications (n = 26) −2415 ± 300 compared to 2331 ± 239 cells/mm2, respectively (p = 0.6) [70]. There was no significant difference in the percentage of hexagonal cells between the two groups at six years either (p = 1.0). Other human studies have also not found a deleterious effect of topical glaucoma medications on ECD [77–79].

Gagnon et al. demonstrated that patients on three or four glaucoma medications had lower cell counts that patients receiving one or two medications [39]. This may be due to a correlation between disease severity and/or medication toxicity. Combined topical agents available for glaucoma treatment have also been analysed [73, 80, 81]. Two studies analysing the effects of latanoprost [80], brinzolamide/latanoprost [80, 81], and latanoprost/timolol [81] for shorter periods of two-three months also demonstrated no significant effect on corneal ECD.

Urban et al. analysed the difference in endothelial cell count in patients with juvenile open angle glaucoma treated with carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, prostaglandin analogue, beta blocker, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (CAI)/beta blocker combination. [73] They found no statistical difference in endothelial cell count between these four groups. Ayaki et al. exposed human cultured corneal endothelial cells to different glaucoma medications preserved and nonpreserved. They reported that cell viability in the presence of a commonly used preservative in eye drops (benzalkonium chloride) was markedly lower, especially with higher concentrations and longer exposure [82].

There has been concern over the use of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and potential deleterious effects on the cornea. The corneal endothelium function relies on a bicarbonate pump to reduce corneal resurgence, for which carbonic anhydrase is a catalyst. However, central ECD cannot directly relate to endothelial function because of the significant functional reserve of this cell layer. No conclusive findings have been observed between carbonic anhydrase inhibitor use and corneal ECD loss [78, 79, 83].

Recently, there has been increasing interest in the use of Rho kinase inhibitors for glaucoma therapy due to the effects on the cytoskeleton of TM cells and Schlemm's canal cells which result in changes of cell morphology and permeability [84]. Netarsudil is the first Rho kinase inhibitor approved for glaucoma therapy in the US. Data from subjects who had 3 months of therapy with either netarsudil 0.02%/latanoprost 0.005% fixed combination (n = 126), netarsudil 0.02% (n = 143) only, or latanoprost 0.005% (n = 146) only compared to baseline found to have no significant difference or effect on ECD or morphology [85]. A significant decrease was observed in the central corneal thickness (CCT) in the fixed combination group (−6.4 µm) compared to the two individual component groups (latanoprost (−1.2 µm) or netarsudil (−3.3 µm)), which may indicate that the potential effects of each drug on CCT are additive, although the magnitude of the observed effects is likely of negligible clinical significance [85].

A summary of changes observed in studies evaluating the effect of topical medications on corneal endothelial density is shown in Table 2. In conclusion, the active ingredients in topical ocular medications have little effect on the corneal endothelium [12]; however, the preservatives used within the medication can potentially affect corneal endothelial physiology [82].

Table 2.

Effect of topical medication on corneal endothelial cell density (CECD).

| % mean cell CECD change at 1 year to baseline (SD) | Number of patients | Citation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prostaglandin analogues | |||

| Latanoprost | 0.3 (2.2) | 127 | [86] |

| −2.3 | 18 | [87] | |

| −3.2 (6 months) | 54 | [88] | |

| −0.04 (3 months) | 146 | [85] | |

|

| |||

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor | |||

| Dorzolamide | No significant difference | [79] | |

| 0.2 | 7 | [78] | |

| −3.6 (5.0) | 148 | [83] | |

|

| |||

| Beta blocker | |||

| Timolol | −4.5 (4.2) | 72 | [83] |

| 0.1 (1.8) | 126 | [86] | |

| Betoxalol | −4.2 (3.6) | 78 | [83] |

|

| |||

| Rho Kinase Inhibitor | |||

| Netarsudil 0.02% | 0.6 (3 months) | 143 | [85] |

|

| |||

| Combined therapy | |||

| Latanoprost-timolol | 0 (2.5) | 126 | [86] |

| Latanoprost-brinzolamide | −0.6 | 16 | [87] |

| Netarsudil 0.02%/latanoprost | 0.6 (3 months) | 126 | [85] |

4. Corneal Endothelium and Glaucoma Surgery

Endothelial cell damage and reducing ECD have been observed in most anterior segment procedures, including various types of glaucoma surgery [89]. Firstly, all implants within the anterior chamber can result in progressive endothelial cell loss [90] including glaucoma drainage devices, although the mechanism is unknown. Secondly, endothelial damage can be caused by a shallow or flat anterior chamber which occurs frequently after trabeculectomy or other filtering glaucoma surgeries [91]. Thirdly, the microinvasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) may cause damage related to their close proximity to the endothelium.

5. Glaucoma Drainage Devices (GDDs)

Numerous studies have evaluated endothelial cell loss after the implantation of tube drainage devices; however, varying methodologies used to quantify ECD, combination surgeries, and differing postoperative management strategies make it difficult to directly compare these studies.

5.1. Ahmed Valve

Statistically significant endothelial cell loss occurs following Ahmed valve implantation [90, 92–97]. Central corneal endothelial cell loss is reported to be between 7.6% and 11.5% (p < 0.05) at six months [90, 93, 94, 97], between 10.5% and 15.3% (p < 0.05) at 12 months [90, 93, 94] and one study reports 15.4% (p < 0.05) at 24 months [94]. A five-year retrospective case series reported that the cumulative risk of corneal decompensation following Ahmed valve insertion is 3.3% [92]. The same study demonstrated accelerated corneal endothelial cell density loss in eyes that had an Ahmed valve compared to fellow glaucomatous eyes which were medically managed (decrease of 7.0%/year and 0.1%/year, respectively; p < 0.001) [92]. However, the rate of loss decreased over time and was no longer statistically significant after two years compared to the controls [92].

Although the exact mechanism causing corneal endothelial cell loss after tube surgery is unknown, it is likely to be multifactorial. For example, changes in the circulation patterns of aqueous humour due to the glaucoma tube have been shown to adversely affect the endothelial cell viability [98–102]. In addition, the glaucoma drainage device itself may induce a breach in the blood-aqueous barrier, either by intermittent tube-uveal touch and/or chronic trauma from intermittent tube-corneal touch caused by heavily rubbing the eye or forcefully blinking, resulting in an increase of influx of oxidative, apoptotic, and inflammatory proteins, potentially causing corneal endothelial damage [98, 101, 103, 104].

A two-year prospective study of 41 eyes evaluated corneal ECD in various locations of the cornea before and after Ahmed valve insertion [94]. After 24 months, the greatest loss was seen in the supratemporal area (22.6%), closest to the site of the tube, whereas the central cornea showed the smallest decrease (15.4%) [94]. A one-year study of 30 eyes reported similar results [90]. Another study of 33 eyes with superotemporally placed Ahmed valves used the difference between supratemporal and inferonasal ECD as an estimate of the change in total ECD [95]. Distance from the tip of the tube to the cornea was significantly associated with fewer endothelial cells superotemporally compared with inferotemporally. Each millimetre that the tube was closer to the endothelial surface was associated with 353.1 fewer endothelial cells superotemporally (p = 0.02) [95]. No significant change in the cell morphology has been reported, except one study that documents an increase in the polymegathism and pleomorphism of corneal endothelial cells in the early postoperative period, but these returned to baseline after six months [90, 94, 105]. In addition, a comparison of sulcus sited Ahmed valve compared to anterior chamber sited valves demonstrated that the mean monthly central endothelial cell loss was significantly higher in tubes sited in the anterior chamber [106, 107]. There was also a significant increase in endothelial cell size in anterior chamber tubes compared to those placed in the sulcus [107]. Furthermore, increasing age of the patient and tube location in the anterior chamber were significantly associated with faster endothelial cell loss [106]. These findings support the theory that tubes closer to the cornea potentially result in increased endothelial cell loss.

When compared to trabeculectomy, Ahmed valves have demonstrated significantly higher endothelial cell loss [93, 96]. In a prospective study of 40 eyes that had Ahmed valves inserted compared with 28 eyes that underwent trabeculectomy, mean central corneal endothelial cell density decreased by 9.4% at 6 months and 12.3% at 12 months compared with baseline values (both, p < 0.001) in the Ahmed valve group [93]. Whist the decrease was less marked in the trabeculectomy group, there was a 1.9% loss at 6 months and 3.2% loss at 12 months (p = 0.027 and p = 0.015, respectively) [93]. In the Ahmed valve group, there was a significant decrease in the corneal ECD between baseline to 6 months and between 6 and 12 months (p < 0.001 and p = 0.005, respectively). However, in the trabeculectomy group, a significant decrease was observed only between baseline to 6 months (p = 0.027) [93]. This study demonstrated that the corneal endothelial cell loss was not only greater in the Ahmed valve group but also persisted for longer. Another study involving 18 patients reported similar findings that corneal endothelial cell loss was statistically significant and higher in the Ahmed group compared to the trabeculectomy group (p > 0.001) [96].

5.2. Molteno Implant

A cohort study directly comparing Ahmed valves in 29 eyes with Molteno implants in 28 eyes demonstrated no significant difference in central corneal endothelial cell loss (11.52% and 12.37%, respectively) after 24 months [108]. They also noted minor increases in central corneal endothelial cell area for both implants. These findings suggest that the type of implant may not matter, rather the presence of a silicone tube in the anterior chamber.

5.3. Baerveldt Glaucoma Drainage Device

Two prospective studies have evaluated the effect of the Baerveldt (BV) glaucoma drainage device on the corneal endothelium [109, 110]. The first study found that after 36 months, central and peripheral corneal ECD had decreased by 4.54% per year and 6.75% per year, respectively (p < 0.001) [109]. Moreover, corneal endothelial cell loss was related to the distance from the tube, with patients with a shorter tube-corneal (TC) distance experiencing an annual loss of 6.20% in the central cornea and 7.25% in the quadrant closest to the BV compared to those with longer TC distances who had an annual loss of 4.11% in the central cornea and 5.77% in the quadrant closest to the BV (p < 0.001) [109].

A second recent study of 64 eyes found that the mean percentage central ECD and peripheral ECD loses at five years were 36.8% and 50.1%, respectively [110]. Tube insertion in the vicinity of, or anterior, to Schwalbe's line as well as a shorter tube length were significantly associated with endothelial cell loss over time [110]. This suggests significant corneal endothelial cell loss with Baerveldt glaucoma drainage devices, particularly in the quadrant closest to the valve.

6. Trabeculectomy

Surgical trauma produced by trabeculectomy and the adjuvant use of mitomycin C (MMC) reduces ECD. Indeed MMC has been found in the aqueous humour after trabeculectomy [111], the presence of which could inhibit periodic repair of DNA as human corneal endothelium is primarily a nonreplicative tissue [112]. Additionally, short-term exposure of human corneal endothelial cells to MMC has shown the formation and interaction of free radicals that cause corneal swelling and disruption of intracellular endothelial organelles [113].

A number of studies showed that ECD loss after trabeculectomy with MMC was 1.9% to 18% [105, 114–121]. However, the results were derived from a relatively small number of cases with short postoperative follow-up periods (i.e., most were 12 months). A study with a longer follow-up of 24 months found the mean ECD decrease was 9.3%, but subgroup analysis demonstrated this was higher in XFG (18.2%) and uveitic glaucoma (20.6%) compared to 1.8% in POAG [122]. Two prospective randomised clinical studies on humans demonstrated endothelial cell damage at 3 and 12 months after MMC trabeculectomy [114, 115], but a subsequent study confirmed significant cell loss occurs during or immediately after MMC-augmented trabeculectomy [123]. Additionally, the active endothelial adaptations observed with no change in ECD between 3 and 12 months suggests that MMC has no prolonged toxic effect on the corneal endothelium. The grade of iridocorneal touch after an overdraining trabeculectomy is also correlated with an increased reduction in ECD [91].

Use of an anterior chamber maintainer or an injection of viscoelastic into the anterior chamber during trabeculectomy might provide more protection for the corneal endothelial cells [120, 124].

7. Deep Sclerectomy

There is presently only one published study evaluating the changes in ECD after deep sclerectomy (DS) and trabeculectomy [116]. The authors reported a significant reduction in cell loss between sclerectomy and trabeculectomy, 2.6% vs. 7% in central cornea, and 3.3% vs. 10.6% in upper cornea, respectively. They hypothesized the reason for this difference is because DS is less invasive than trabeculectomy as it does not penetrate the anterior chamber. When either DS or trabeculectomy was combined with cataract surgery, the difference was not statistically significant [116]. It is important to remark that this study compared DS with trabeculectomy without the use of antimetabolites.

8. Microinvasive Glaucoma Surgeries (MIGS)

In the last 10 years, microinvasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) have been increasingly used as an approach for treating glaucoma. MIGS can be divided into three main groups: Schlemm's canal MIGS, suprachoroidal MIGS, and subconjunctival MIGS.

8.1. Schlemm's Canal MIGS

The iStent (Glaukos Corp., San Clemente, CA, USA) has shown a moderate effect in controlling IOP [125, 126]. In a series of 10 Japanese eyes with OAG undergoing standalone implantation of 2 first-generation iStents, no change in ECD was observed through 6 months of follow-up [127]. An evolution of the iStent, the iStent Inject, has been developed to increase the efficacy of this device [128]. The iStent Inject's pivotal trial evaluated ECD and found a 13.1% reduction at 24 months postoperatively in the iStent-phaco group compared to a 12.3% reduction in eyes going phacoemulsification only [128]. The majority of the reduction in the ECD occurred within the first 3 months [128]. Similarly, a further study found a reduction of 9.0% (n = 21) at a mean follow-up of 18.2 months, as well as a significant reduction in the percentage of hexagonal cells [128].

In a prospective, uncontrolled case series of 20 eyes undergoing combined iStent-phaco, mean ECD decreased from 2290 to 1987 cells/mm2 (13.2% decrease) at 12 months [129]. Evaluation of 12-month data after the implantation of 2 iStent Inject devices combined with phacoemulsification (n = 54) found a 14.6% reduction in the endothelial cell count from baseline (2417 ± 417 cells/mm2 at baseline to 2065 ± 536 cells/mm2 at 12 months, p = 0.001) which was comparable to patients undergoing phaco alone (-14.4%) [130].

Ivantis, Inc., (Irvine, CA, USA) developed a new device in 2014 called the Hydrus Microstent [131]. A retrospective nonrandomised clinical study comparing the endothelial changes after a Hydrus (Hydrus, Ivantis, Irvine, CA) MIGS implant combined with cataract surgery (n = 37) versus cataract surgery alone (n = 25) did not show any difference in endothelial parameters 6 months [132]. The HORIZON study found that the ECD reduced from 2417 ± 390 cells/mm2 at baseline to 2056 ± 483 cells/mm2 at 3 years in the combined phacoemulsification and Hydrus (n = 369) group compared to a reduction from 2426 ± 371 cells/mm2 at baseline to 2167 ± 440 cells/mm2 at 3 years in the phaco alone group (n = 187) [133]. This reduction was initially related to the surgical procedure and the addition of the Microstent induced an incremental nonsignificant loss in mean central cell count of 2% (approximately 75 cells/mm2) [133]. This finding may be related to the additional surgical manipulation with insertion and removal of additional cohesive viscoelastic when placing the device. Sequential visit-to-visit changes in endothelial cell counts were consistent between the study groups and this was not statistically significant [133]. After the initial loss in cell count related to the surgery, no difference was found in the year-to-year change in the proportion of eyes with 30% endothelial cell loss between groups [133].

8.2. Suprachoroidal MIGS

Suprachoroidal MIGS target the uveoscleral pathway to reduce the IOP. Cypass (Alcon, Ft. Worth, TX, USA) [134], a suprachoroidal MIGS was unfortunately recalled in 2018 as the 5-year data demonstrated high rates of endothelial cell loss (3% per year in the Cypass group compared to 1% control phaco alone) that were deemed to compromise its safety [135]. At month 60, the mean percent of changes in ECD was −20.4% (95% CI, −23.5% to −17.5%) in the phaco and Cypass group (n = 282) and −10.1% (95% CI, −13.9% to −6.3%) in the control group (n = 67) [135]. In addition, 9 adverse events were possibly related to ECD loss, including 3 eyes with transient focal corneal oedema and 4 eyes that required Cypass trimming due to protrusion. The prominent position of the device within the anterior chamber was deemed to be the reason for the changes observed and in some instances the Cypass stent has been explanted due to corneal decompensation [136].

8.3. Subconjunctival MIGS

Subconjunctival MIGS include the XEN subconjunctival implant gel stent (Aquesys, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA/Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA). One study evaluated standalone phacoemulsification (n = 15) and found a mean reduction of ECD by 14.5% at 24 months compared to a mean reduction of 14.3% at 24 months in the combined phaco/XEN surgery (n = 17). The difference in percentage reduction of ECD between the 2 groups was not significant (p = 0.226) [137]. A further study compared trabeculectomy (n = 31) to XEN gel stents (n = 49) and found a significantly higher rate of cell loss at 3 months in the trabeculectomy group (-10%) than the XEN gel stent group (-2.1%) when compared to baseline [138].

In recent years, the Preserflo (formerly InnFocus) (Santen Co., Japan), which creates a bleb by the insertion of an 8.5 mm polymeric in anterior chamber via a scleral pocket, has come to the market. Results showed no significant difference at 6 months between endothelial cell loss in 26 eyes with Preserflo (gain of 2.7%) compared to 26 after trabeculectomy (loss of 3.2%) [139]. Both procedures significantly changed the coefficient of variation but had no significant changes on percentage of hexagonal cells. The endothelial cell count was evaluated at one year as part of a 2 year prospective randomised multicentre study of the Microshunt (n = 395) versus trabeculectomy (n = 132) [140]. Endothelial cell loss was similar in both groups at year 1 (05.2% after Microshunt implantation and -6.9% after trabeculectomy). One patient in the Microshunt group experienced endothelial cell loss of 9.4% between 6 months and 1 year, which was presumed to be due to the proximity of the device to the cornea [140].

The Ex-Press mini glaucoma shunt (Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, TX) is a further subconjunctival Microshunt. Studies have compared the Ex-Press shunt with trabeculectomy and Ahmed valves [105, 119]. In a 3-month prospective study, no significant reduction in corneal ECD occurred in the Ex-Press group (1.3%, p > 0.05) [105]. Unlike the trabeculectomy group which had a significant decrease of 3.5% at 1 month (p = 0.012) and 4.2% at 3 months (p = 0.007), and the Ahmed valve group, where a significant decrease of 3.5% was seen after 3 months (p = 0.04) [105], a further group found reduction of endothelial cell count after Ex-Press implantation by 3.5%, but no significant difference between trabeculectomy and the Ex-Press shunt [119]. Other groups, however, have demonstrated cases of corneal decompensation after the Ex-Press stent and significant reductions of endothelial cell count (4% at 24 months from baseline), which may have been due to intermittent endothelial contact [141, 142]. In addition, the endothelial cell loss has been observed to be significantly higher in the superior cornea, which is close to the shunt site (-17.6%) compared to the inferior cornea (-11.7%) [143].

Alternative MIGS interventions include Ab interno-trabeculotomy with the Trabectome device (NeoMedix, Tustin, CA, USA) which has been shown to have minimal effects on corneal endothelial cells at 6 months and up to 36 months postoperatively [144, 145]. A goniotomy with the Kahook Dual Blade (KDB, New World Medical, Rancho Cucamonga, CA) has been shown to reduce the endothelial cell density by only 3.4% at a mean follow-up of 18.2 months after procedure (n = 21) with no significant effect on other morphological parameters [146]. Furthermore, the Excimer Laser Trabeculotomy (ELT, Glautec AG, Nurnberg, Germany) [147], the Fugo Blade (MediSurg Research and Management Corp., Norristown, PA, USA) [98, 148], the Ab interno-canaloplasty (ABIC) [99, 100], and the gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy (GATT) [101] could potentially have an impact on the endothelial cell count. No studies are presently available in the literature in regard to these.

9. Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK) Use in the Management of Glaucoma-Related Endothelial Cell Loss

Corneal endothelial cell loss can subsequently result in corneal decompensation, and this continues to be a common comorbidity after glaucoma surgery [102]. The introduction of Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) and Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) has replaced the use of penetrating keratoplasty (PK) as the standard of care for endothelial disorders [103]. In the presence of glaucoma drainage devices, higher rates of corneal graft failure and increased ECD loss are observed after penetrating keratoplasty and DSAEK; as suggested earlier, the reasons for this are multifactorial [104, 149–153].

DMEK surgery is increasingly used as a method of treating corneal endothelial dysfunction and shows reduced rejection rates and faster visual recovery when compared to DSAEK [154–156]. A key benefit is that the rapid visual recovery and reduction in corneal oedema allows for early visual field testing or optic nerve examination to decide on further glaucoma management [157]. Another advantage of DMEK is that the taper of topical corticosteroids postoperatively is quicker than that after PK and DSEK. The quicker taper potentially lowers the risk of IOP elevation, resulting from the steroid response [158]. The steroid IOP response rates after DMEK and DSAEK have been shown to be 15% and 17%, respectively (p = 0.768) [159, 160]. These are not any higher than expected for any patient on long-term steroidal treatment [159, 160].

Performing a DMEK surgical procedure is, however, more challenging in eyes with previous glaucoma surgery. For example, the presence of corneal oedema, a tube shunt, anterior synechiae, previous trabeculectomy, or an abnormal anterior segment can make the surgery more difficult [157]. Studies have been performed to evaluate the outcomes and complications of DMEK surgery after glaucoma surgery, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

A table to show the previous studies performed evaluating the clinical outcomes of DMEK after glaucoma surgery.

| Paper | Number of patients | Previous glaucoma surgery | Length of follow-up | VA improvement | Rate of ECD loss postop | Primary graft failure | Rebubbling rates | Secondary graft failure | Postoperative IOP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alshaker et al., 2021 [160] |

N = 48 DMEK, N = 41 DSAEK |

62.5% tube, 37.5% trab only, 61.0% tube, 39.0% trab only |

30.0 ± 15.5 months, 33.9 ± 22.5 months |

Postoperative BCVA was significantly better in DMEK group at 24 months (p = 0.047) | 57%, 50% (p = 0.886) at 36 months |

14.6%, 14.6% (p = 1.0) |

25.0%, 19.5% (P = 0.615 |

20.8%, 19.5% (p = 1.0) |

14.6%, 17.1% (IOP: 25–45 mmHg) (P = 0.768) |

| Fili et al., 2021 [161] |

N = 16 DMEK, N = 9 DSAEK, N = 15 PK |

68.8% trab, 43.8% tube, 100.0% trab, 22.2% tube, 80.0% trab, 40% tube, |

24 months | Final BCVA at 24 months 0.34 ± 0.29 0.17 ± 0.18 0.06 ± 0.07 |

50.7%, 48.9%, 42.7% at 12 months (P < 0.45) |

6.25%, 11.11%, 0 |

N/A | 12.5%, 33.33%, 13.33% |

6.25%, 11.11%, 0 |

| Bonnet et al., 2020 [158] |

N = 11 medically treated GL, N = 38 surgically treated Gl, N = 41 no GL |

55.3% previous trab, 68.4% previous tube | 38.4 ± 11.2 months | Achieved BCVA of ≥20/20, 46%, 8%, 49% (p < 0.01) |

47.6%, 63.8%, 44.0% (p < 0.05) |

0%, 0%, 0% |

18.2%, 15.8%, 19.5% (p = 0.93) |

0%, 41.6%, 2.4% (p < 0.05) |

54.5%, 26.3%, 34.1% (IOP >24 mm Hg or >8 increase) (p = 0.21) |

| Sorkin et al., 2020 [162] |

N = 51 surgically treated Gl, N = 43 controls |

49.0% previous tube, 13.7% trab and tube, 37.3% previous trab |

37.9 ± 15.2 months, 33.8 ± 13.5 months |

Mean BCVA improved from 1.82 ± 0.88 logMAR preop to 1.06 ± 0.87 at 6 months (no comparison to controls) | 74%, 52% at 48 months (P = 0.004) |

15.7%, 11.6% P = 0.766 |

23.5%, 30.2% P = 0.491 |

47.1%, 0% P < 0.001 |

7.8% (control group not reported) |

| Boutin et al., 2020 [163] | N = 27 | 44.4% prior tube, 33.3% prior trab, 14.8% trab and tube, 3.7% trab and gold Microshunt, 3.7% prior tube and hydrus |

14.6 ± 6.1 months | Mean BCVA improved from 1.34 ± 0.65 logMAR preop to 0.50 ± 0.33 at 1 year | 50.4% at one year (P = 0.001) |

3.7% | 18.5% | 10.3% | 3.7% |

| Lin et al., 2019 [164] |

N = 46 DMEK N = 46 DSEK |

48% prior trab, 78% prior tube, 50% prior trab, 74% prior tube |

12 months | Improved by -0.89 logMAR, -0.62 logMAR (p = 0.005) |

N/A N/A |

2% 2% (p = 0.65) |

22% 9% (p = 0.14) |

0% 17% (p = 0.006) |

30% IOP elevation, 36% IOP elevation (increase >8 mmHg) (p = 0.66) |

| Birbal et al., 2018 [153] | N = 23 | 65% trabeculectomy, 100% tubes (85% 1 tube, 15% 2 tubes) |

19 ± 17 months | BCVA improved by ≥ 2 Snellen lines in 73% | 71% | 8.7% | 21.7% | 8.7% | 9% (IOP >24 mmHg or >10 mmHg increase) |

| Aravena et al., 2017 [165] |

N = 14 medically treated GL, N = 34 surgically treated Gl, N = 60 no GL |

52.9% tube only, 14.7% trab and tube, 32.3% trab only |

9.7 ± 7.3 months | Achieved BCVA of ≥20/25, 71.4%, 32.4%, 62.6% P < 0.0001 |

29.9 ± 12.0%, 44.6 ± 17.8%, 32.7 ± 11.3%, P = 0.001 |

0, 0, 1.7% P = 1.0 |

21.4%, 23.5%, 23.3% |

0, 0, 0 |

50.0%, 14.7%, 23.3% (p = 0.001) |

N: number; DMEK: Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty; DSAEK: Descemet striping automated endothelial keratoplasty; BCVA: best corrected visual acuity; ECD: endothelial cell density; IOP: intraocular pressure; GL: glaucoma.

10. Conclusions

In summary, we have outlined the endothelial cell changes which occur due to glaucoma itself, as well as those which occur as a result of its medical and surgical management, including new generation MIGS devices. We have explored the use of DMEK for the management of corneal endothelial failure and the recent literature illustrating the results including complications after performing DMEK for postglaucoma endothelial loss. Additional studies are required to investigate the cause of the accelerated endothelial cell loss in glaucoma patients undergoing DMEK surgery and assessment of glaucoma progression related to DMEK surgery.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Foster P. J., Buhrmann R., Quigley H. a., Johnson G. J. Prevalence surveys. British Journal of Ophthalmology . 2002:238–243. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tham Y., Li X., Wong T. Y., Quigley H. A., Aung T., Ed F. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040 A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology . 2020;121(11):2081–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janson B. J., Alward W. L., Kwon Y. H., Bettis D. I., Fingert J. H., Provencher L. M. Glaucoma-associated corneal endothelial cell damage: a review. Survey of Ophthalmology . 2018;63(4):500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edelhauser H. F. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science . 2006. The balance between corneal transparency and edema: the proctor lecture. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zavala J., Ló Pez Jaime G., Barrientos C. R., Valdez-Garcia J. Corneal endothelium: developmental strategies for regeneration. Eye . 2013;27(January):579–588. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonanno J. A. Molecular mechanisms underlying the corneal endothelial pump. Experimental Eye Research . 2012;95(1):2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mergler S., Pleyer U. The human corneal endothelium: new insights into electrophysiology and ion channels. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research . 2007;26(4):359–378. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edelhauser H. F. The balance between corneal transparency and edema: the Proctor Lecture. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science . 2006;47(5):1754–1767. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinivas S. P. Dynamic regulation of barrier integrity of the corneal endothelium. Optometry and Vision Science . 2010;87(4):E239–54. doi: 10.1097/opx.0b013e3181d39464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng H., Jacobs P. M., McPherson K., Noble M. J. Precision of cell density estimates and endothelial cell loss with age. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill . 1985;103(10):1478–1481. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050100054017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bourne W. M., Nelson L. I. L., Hodge D. O. Central corneal endothelial cell changes over a ten-year period. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science . 1997;38(3):779–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourne W. M., McLaren J. W. Clinical responses of the corneal endothelium. Experimental Eye Research . 2004;78(3):561–572. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joyce N. C. Proliferative capacity of the corneal endothelium. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research . 2003;22(3):359–389. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wigham C. G., Hodson S. A. Physiological changes in the cornea of the ageing eye. Eye . 1987;1(Pt 2):190–196. doi: 10.1038/eye.1987.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.John T. Corneal Endothelial Transplant DSEAK, DMEK and DLEK . New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers,Medical Publishers Pvt. Limited; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson K. H., Bourne W. M., McLaren J. W., Brubaker R. F. Variations in human corneal endothelial cell morphology and permeability to fluorescein with age. Experimental Eye Research . 1988;47(1):27–41. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(88)90021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bourne W. M. Biology of the corneal endothelium in health and disease. Eye . 2003;17(8):912–918. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Senoo T., Joyce N. C. Cell cycle kinetics in corneal endothelium from old and young donors. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science . 2000 Mar;41(3):660–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim T. Y., Kim W.-I., Smith R. E., Kay E. P. Role of p27Kip1 in cAMP- and TGF-{beta}2-Mediated antiproliferation in rabbit corneal endothelial cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science . 2001;42(13):3142–3149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denniston A. K., Kottoor S. H., Khan I., Oswal K., Williams G. P., Abbott J. Endogenous cortisol and TGF-beta in human aqueous humor contribute to ocular immune privilege by regulating dendritic cell function. The Journal of Immunology . 2011;186(1):305–311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeuchi M., Kosiewicz M. M., Alard P., Streilein J. W. On the mechanisms by which transforming growth factor-beta 2 alters antigen-presenting abilities of macrophages on T cell activation. European Journal of Immunology . 1997;27(7):1648–1656. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor A. W., Yee D. G., Nishida T., Namba K. Neuropeptide regulation of immunity. The immunosuppressive activity of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (alpha-MSH) Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences . 2000;917:239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasquale L. R., Dorman-Pease M. E., Lutty G. A., Quigley H. A., Jampel H. D. Immunolocalization of TGF-beta 1, TGF-beta 2, and TGF-beta 3 in the anterior segment of the human eye. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science . 1993;34(1):23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trivedi R. H., Nutaitis M., Vroman D., Crosson C. E. Influence of race and age on aqueous humor levels of transforming growth factor-beta 2 in glaucomatous and nonglaucomatous eyes. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics . 2011;27(5):477–480. doi: 10.1089/jop.2010.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sagoo P., Chan G., Larkin D. F., George A. J. Inflammatory cytokines induce apoptosis of corneal endothelium through nitric oxide. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science . 2004;45(11):3964–3973. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tu K. L., Kaye S. B., Sidaras G., Taylor W., Shenkin A. Effect of intraocular surgery and ketamine on aqueous and serum cytokines. Molecular Vision . 2007;13(July):1130–1137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schauersberger J., Kruger A., Müllner-Eidenböck A., Petternel V., Abela C., Svolba G., et al. Long-term disorders of the blood-aqueous barrier after small-incision cataract surgery. Eye . 2000;14(Pt 1):61–63. doi: 10.1038/eye.2000.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoue T., Kawaji T., Inatani M., Kameda T., Yoshimura N., Tanihara H. Simultaneous increases in multiple proinflammatory cytokines in the aqueous humor in pseudophakic glaucomatous eyes. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery . 2012;38(8):1389–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthaei M., Gillessen J., Muether P. S., Hoerster R., Bachmann B. O., Hueber A. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)-Related cytokines in the aqueous humor of phakic and pseudophakic Fuchs’ dystrophy eyes. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science . 2015;56(4):2749–2754. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prendes M. A., Harris A., Wirostko B. M., Gerber A. L., Siesky B. The role of transforming growth factor β in glaucoma and the therapeutic implications. British Journal of Ophthalmology . 2013;97(6):680–686. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richter K., Konzack A., Pihlajaniemi T., Heljasvaara R. Redox- fibrosis : impact of TGF β 1 on ROS generators , mediators and functional consequences. 2015;6:344–352. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlunck G., Meyer-ter-Vehn T., Klink T., Grehn F. Conjunctival fibrosis following filtering glaucoma surgery. Experimental Eye Research . 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saika S., Yamanaka O., Sumioka T., Miyamoto T., Miyazaki K. ichi., Okada Y. Fibrotic disorders in the eye: targets of gene therapy. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research . 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamm E. R., Fuchshofer R. What increases outflow resistance in primary open-angle glaucoma? Survey of Ophthalmology . 2007;52(6 SUPPL) doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Acott T. S., Kelley M. J. Extracellular matrix in the trabecular meshwork. Experimental Eye Research . 2008;86:543–561. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardali E., Sanchez-Duffhues G., Gomez-Puerto M. C., ten Dijke P. TGF-β-induced endothelial-mesenchymal transition in fibrotic diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2017 doi: 10.3390/ijms18102157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma J., Sanchez-Duffhues G., Goumans M. J., ten Dijke P. TGF-β-Induced endothelial to mesenchymal transition in disease and tissue engineering. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology . 2020;8(April):1–14. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleenor D. L., Shepard A. R., Hellberg P. E., Jacobson N., Pang I. H., Clark A. F. TGFβ2-induced changes in human trabecular meshwork: implications for intraocular pressure. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science . 2006 doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gagnon M., Boisjoly H. M., Brunette I., Charest M., Amyot M. Corneal endothelial cell density in glaucoma. Cornea . 1997;16:314–318. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cho S. W., Kim J. M., Choi C. Y., Park K. H. Changes in corneal endothelial cell density in patients with normal-tension glaucoma. Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology . 2009;53(6):569–573. doi: 10.1007/s10384-009-0740-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ritch R., Lowe R. F. The Glaucomas . 1996. Angle-closure glaucoma. Mechanisms and epidemiology; p. p. 801. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olsen T. The endothelial cell damage in acute glaucoma. On the corneal thickness response to intraocular pressure. Acta Ophthalmologica . 1980;58(2):257–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1980.tb05719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Setala K. Corneal endothelial cell density after an attack of acute glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmologica . 1979;57(6):1004–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1979.tb00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bigar F., Witmer R. Corneal endothelial changes in primary acute angle-closure glaucoma. Ophthalmology . 1982;89(6):596–599. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(82)34744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malaise-Stals J., Collignon-Brach J., Weekers J. F. Corneal endothelial cell density in acute angle-closure glaucoma. Ophthalmologica . 1984;189:104–109. doi: 10.1159/000309393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sihota R., Lakshmaiah N. C., Titiyal J. S., Dada T., Agarwal H. C. Corneal endothelial status in the subtypes of primary angle closure glaucoma. Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology . 2003;31(6):492–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2003.00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen M.-J., Jui C., Liu -Ling, Cheng C.-Y., Lee S.-M. Corneal Status in Primary Angle-Closure Glaucoma with a History of Acute Attack . 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zarnowski T., Lekawa A., Dyduch A., Turek R., Zagorski Z. Corneal endothelial density in glaucoma patients. Klinika Oczna . 2005;107:448–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tham C. C., Kwong Y. Y., Lai J. S., Lam D. S. Effect of a previous acute angle closure attack on the corneal endothelial cell density in chronic angle closure glaucoma patients. Journal of Glaucoma . 2006 doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000212273.73100.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verma S., Nongpiur M. E., Husain R., Wong T. T., Boey P. Y., Quek D. Characteristics of the corneal endothelium across the primary angle closure disease spectrum. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science . 2018;59(11):4525–4530. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-24939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varadaraj V., Sengupta S., Palaniswamy K., Srinivasan K., Kader M. A., Raman G. Evaluation of angle closure as a risk factor for reduced corneal endothelial cell density. Journal of Glaucoma . 2017;26(6):566–570. doi: 10.1097/ijg.0000000000000669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee J. W. Y., Wong R. L. M., Chan J. C. H., Wong I. Y. H., Lai J. S. M. Differences in corneal parameters between normal tension glaucoma and primary open-angle glaucoma. International Ophthalmology . 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10792-014-0020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwon J. W., Cho K. J., Kim H. K., Lee J. K., Gore P. K., Mccartney M. D. Analyses of Factors Affecting Endothelial Cell Density in an Eye Bank Corneal Donor Database . 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Damji K. F. Progress in understanding pseudoexfoliation syndrome and pseudoexfoliation-associated glaucoma. Canadian journal of ophthalmology Journal canadien d’ophtalmologie . 2007;42(5):657–658. doi: 10.3129/i07-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ritch R., Schlotzer-Schrehardt U., Aasved H., Aasved H., Aasved H., Aasved H. Exfoliation syndrome. Survey of Ophthalmology . 1975;45(4):265–315. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zenkel M., Schlötzer-Schrehardt U. The composition of exfoliation material and the cells involved in its production. Journal of Glaucoma . 2014;23(8 Suppl 1):S12–S14. doi: 10.1097/ijg.0000000000000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ritch R. Exfoliation syndrome-the most common identifiable cause of open-angle glaucoma. Journal of Glaucoma . 1994;3(2):176–177. doi: 10.1097/00061198-199400320-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schlotzer-Schrehardt U. M., Dorfler S., Naumann G. O. Corneal endothelial involvement in pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill . 1993;111(5):666–674. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090050100038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knorr H. L., Junemann A., Handel A., Naumann G. O. [Morphometric and qualitative changes in corneal endothelium in pseudoexfoliation syndrome] Fortschritte der Ophthalmologie: Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft . 1991;88(6):786–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seitz B., Muller E. E., Langenbucher A., Kus M. M., Naumann G. O. [Endothelial keratopathy in pseudoexfoliation syndrome: quantitative and qualitative morphometry using automated video image analysis] Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde . 1995;207(3):167–175. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1035363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Inoue K., Okugawa K., Oshika T., Amano S. Morphological study of corneal endothelium and corneal thickness in pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology . 2003;47(3):235–239. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(03)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wali U. K., Bialasiewicz A. A., Rizvi S. G., Al-Belushi H. In vivo morphometry of corneal endothelial cells in pseudoexfoliation keratopathy with glaucoma and cataract. Ophthalmic Genetics . 2009;41:175–179. doi: 10.1159/000210831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng X., Shiraishi A., Okuma S., Mizoue S., Goto T., Kawasaki S. In vivo confocal microscopic evidence of keratopathy in patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science . 2011;52(3):1755–1761. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang M., Sun W., Ying L., Dong X.-G. Corneal endothelial cell density and morphology in Chinese patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome. International Journal of Ophthalmology . 2012;5(2):186–189. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2012.02.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quiroga L., van Lansingh C., Samudio M., Peña F. Y., Carter M. J. Characteristics of the corneal endothelium and pseudoexfoliation syndrome in patients with senile cataract. Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology . 2010;38(5):449–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tomaszewski B. T., Zalewska R., Mariak Z. Evaluation of the endothelial cell density and the central corneal thickness in pseudoexfoliation syndrome and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. Journal of Ophthalmology . 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/123683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bozkurt B., Güzel H., Kamış Ü., Gedik Ş., Okudan S. Characteristics of the anterior segment biometry and corneal endothelium in eyes with pseudoexfoliation syndrome and senile cataract. Turkish Journal of Orthodontics . 2015;45(5):188–192. doi: 10.4274/tjo.48264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Novak-Stroligo M., Alpeza-Dunato Z., Kovacević D., Caljkusić-Mance T. Specular microscopy in glaucoma patients. Collegium Antropologicum . 2010;34(Suppl 2):209–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miyake K., Matsuda M., Inaba M. Corneal endothelial changes in pseudoexfoliation syndrome. American Journal of Ophthalmology . 1989;108(1):49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baratz K. H., Nau C. B., Winter E. J., McLaren J. W., Hodge D. O., Herman D. C. Effects of glaucoma medications on corneal endothelium, keratocytes, and subbasal nerves among participants in the ocular hypertension treatment study. Cornea . 2006;25(9):1046–1052. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000230499.07273.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chawla K., Gadaginamath S., Shah A. K. Comparison of central corneal thickness and endothelial cell density in patients with various types of glaucoma and patients without glaucoma: a case-control study. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research . 2021;15(8):6–11. doi: 10.7860/jcdr/2021/48907.15227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu Z. Y., Wu L., Qu B. Changes in corneal endothelial cell density in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. World Journal of Clinical Cases . 2019;7(15):1978–1985. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i15.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Urban B. Bakunowicz-??Azarczyk A, Michalczuk M, Kr??towska M. Evaluation of corneal endothelium in adolescents with juvenile glaucoma. Journal of Ophthalmology . 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/895428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guigou S., Coste R., Denis D. [Central corneal thickness and endothelial cell density in congenital glaucoma] Journal Francais D’ophtalmologie . 2008;31(5):509–514. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(08)72468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wenzel M., Krippendorff U., Hunold W., Reim M. [Corneal endothelial damage in congenital and juvenile glaucoma] Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde . 1989;195(6):344–348. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1050052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kwon J. W., Rand G. M., Cho K. J., Gore P. K., Mccartney M. D., Chuck R. S. Association between Corneal Endothelial Cell Density and Topical Glaucoma Medication Use in an Eye Bank Donor Population . 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lass J. H., Khosrof S. a., Laurence J. K., Horwitz B., Ghosh K., Adamsons I. A double-masked, randomized, 1-year study comparing the corneal effects of dorzolamide, timolol, and betaxolol. Dorzolamide Corneal Effects Study Group. Archives of Ophthalmology . 1998;116(8):1003–1010. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.8.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Giasson C. J., Nguyen T. Q. T., Boisjoly H. M., Lesk M. R., Amyot M., Charest M. Dorzolamide and corneal recovery from edema in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. American Journal of Ophthalmology . 2000;129(2):144–150. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaminski S., Hommer a., Koyuncu D., Biowski R., Barisani T., Baumgartner I. Influence of dorzolamide on corneal thickness, endothelial cell count and corneal sensibility. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica . 1998;76(October 2015):78–79. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1998.760114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nakamoto K., Yasuda N. Effect of concomitant use of latanoprost and brinzolamide on 24-hour variation of IOP in normal-tension glaucoma. Journal of Glaucoma . 2007;16(4):352–357. doi: 10.1097/ijg.0b013e318033b491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miura K., Ito K., Okawa C., Sugimoto K., Matsunaga K., Uji Y. Comparison of ocular hypotensive effect and safety of brinzolamide and timolol added to latanoprost. Journal of Glaucoma . 2008;17(3):233–237. doi: 10.1097/ijg.0b013e31815072fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ayaki M., Iwasawa A., Inoue Y. Toxicity of antiglaucoma drugs with and without benzalkonium chloride to cultured human corneal endothelial cells. Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ) . 2010;4:1217–1222. doi: 10.2147/opth.s13708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lass J. H., Simpson C. V., Eriksson G. A double-masked, randomized 1-year study comparing the corneal effects of latanoprost and timolol. 1999;116:p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moura-Coelho N., Tavares Ferreira J., Bruxelas C. P., Dutra-Medeiros M., Cunha J. P., Pinto Proença R. Rho kinase inhibitors—a review on the physiology and clinical use in Ophthalmology. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. . 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00417-019-04283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wisely C. E., Sheng H., Heah T., Kim T. Effects of netarsudil and latanoprost alone and in fixed combination on corneal endothelium and corneal thickness: post-hoc analysis of MERCURY-2. Advances in Therapy . 2020;37(3):1114–1123. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01227-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lass J. H., Eriksson G. L., Osterling L., Simpson C. V. Comparison of the corneal effects of latanoprost, fixed combination latanoprost-timolol, and timolol: a double-masked, randomized, one-year study. Ophthalmology . 2001;108(2):264–271. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakano T., Inoue R., Kimura T., Suzumura H., Tanino T., Yamazaki Y. Effects of brinzolamide, a topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, on corneal endothelial cells. Advances in Therapy . 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12325-016-0373-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kalınlığı L. K., Sayısı E., Kamara Ö., Etkileri A. U. The effects of latanoprost on corneal thickness , endothelial cell density , topography; anterior chamber depth and axial length. pp. 4–9.

- 89.Ho J. W., Afshari N. A. Advances in cataract surgery: preserving the corneal endothelium. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology . 2015;26(1):22–27. doi: 10.1097/icu.0000000000000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim C. S., Yim J. H., Lee E. K., Lee N. H. Changes in corneal endothelial cell density and morphology after Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation during the first year of follow up. Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology . 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Smith D., Gregory L., Kim A., David C. The Effect of Glaucoma Filtering Surgery on Corneal Endothelial Cell Density . 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim K. N., Lee S. B., Lee Y. H., Lee J. J., Lim H. B., Kim C. Changes in corneal endothelial cell density and the cumulative risk of corneal decompensation after Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation. British Journal of Ophthalmology . 2015 doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim M. S., Kim K. N., Kim C.-S. Changes in corneal endothelial cell after ahmed glaucoma valve implantation and trabeculectomy: 1-year follow-up. Korean Journal of Ophthalmology . 2016;30(6):1011–8942. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2016.30.6.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lee E.-K., Yun Y.-J., Lee J.-E., Yim J.-H., Kim C.-S. Changes in corneal endothelial cells after ahmed glaucoma valve implantation: 2-year follow-up. American Journal of Ophthalmology . 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Koo E. B., Hou J., Han Y., Keenan J. D., Stamper R. L., Jeng B. H. Effect of Glaucoma Tube Shunt Parameters on Cornea Endothelial Cells in Patients with Ahmed Valve Implants . 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Akdemir M. O., Acar B. T., Kokturk F., Acar S. Clinical outcomes of trabeculectomy vs. Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation in patients with penetrating keratoplasty: (Trabeculectomy vs. Ahmed glaucoma valve in patients with penetrating keratoplasty) International Ophthalmology . 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10792-015-0160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mendrinos E., Dosso A., Sommerhalder J., Shaarawy T. Coupling of HRT II and AS-OCT to evaluate corneal endothelial cell loss and in vivo visualization of the Ahmed glaucoma valve implant. Eye . 2008;23:1836–1844. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Francis B. A., Singh K., Lin S. C., Hodapp E., Jampel H. D., Samples J. R. Novel glaucoma procedures: a report by the American Academy of ophthalmology. Ophthalmology . 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Körber N. Canaloplasty Ab Interno - A Minimally Invasive Alternative . Germany: Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Davids A. M., Pahlitzsch M., Boeker A., Winterhalter S., Maier-Wenzel A. K., Klamann M. Ab Interno Canaloplasty (ABiC)—12-Month Results of a New Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS) Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lavia C., Dallorto L., Maule M., Ceccarelli M., Fea A. M. Minimally-invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) for open angle glaucoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One . 2017 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hau S., Barton K. Corneal complications of glaucoma surgery. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology . 2009;20(2):131–136. doi: 10.1097/icu.0b013e328325a54b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Borroni D., Rocha De Lossada C., Parekh M., Gadhvi K., Bonzano C., Romano V. Tips, tricks, and guides in descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty learning curve. Journal of Ophthalmology . 2021;2021:9. doi: 10.1155/2021/1819454.1819454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Anshu A., Price M. O., Price F. W. Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty: long-term graft survival and risk factors for failure in eyes with preexisting glaucoma. Ophthalmology . 2012;119(10):1982–1987. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Casini G., Loiudice P., Pellegrini M., indara S. A. T., Martinelli P., Passani A. Trabeculectomy versus EX-PRESS shunt versus ahmed valve implant: short-term effects on corneal endothelial cells. American Journal of Ophthalmology . 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang Q., Liu Y., Thanapaisal S., Oatts J., Luo Y., Ying G. S. The effect of tube location on corneal endothelial cells in patients with ahmed glaucoma valve. Ophthalmology . 2021;128(2):218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.06.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Godinho G., Barbosa-Breda J., Oliveira-Ferreira C., Madeira C., Melo A., Falcão-Reis F. Anterior chamber versus ciliary sulcus ahmed glaucoma valve tube placement: longitudinal evaluation of corneal endothelial cell profiles. Journal of Glaucoma . 2021;30(2):170–174. doi: 10.1097/ijg.0000000000001700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.N1 N., Nassiri N., Majdi N. M., Salehi M., Panahi N., Djalilian A. R. P. G. A. Corneal endothelial cell changes after Ahmed valve and Molteno glaucoma implants. Ophthalmic Surgery, Lasers and Imaging . 2011;42(5):394–399. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20110812-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tan A. N., Webers C. A. B., Berendschot T. T. J. M., De Brabander J., De Witte P. M., Nuijts R. M. M. A. Corneal Endothelial Cell Loss after Baerveldt Glaucoma Drainage Device Implantation in the Anterior Chamber . 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hau S., Bunce C., Barton K. Corneal endothelial cell loss after Baerveldt glaucoma implant surgery. Ophthalmology Glaucoma . 2021;4(1):20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Seah S. K., Prata J. a., Minckler D. S., Koda R. T., Baerveldt G., Lee P. P. Mitomycin-C concentration in human aqueous humour following trabeculectomy. Eye . 1993;7(Pt 5):652–655. doi: 10.1038/eye.1993.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]