Abstract

Introduction

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) are two cholinergic enzymes catalyzing the reaction of cleaving acetylcholine into acetate and choline at the neuromuscular junction. Abnormal hyperactivity of AChE and BChE can lead to cholinergic deficiency, which is associated with several neurological disorders including cognitive decline and memory impairments. Preclinical studies support that some cannabinoids including cannabidiol (CBD) and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) may exert pharmacological effects on the cholinergic system, but it remains unclear whether cannabinoids can inhibit AChE and BChE activities. Herein, we aimed to evaluate the inhibitory effects of a panel of cannabinoids including CBD, Δ8-THC, cannabigerol (CBG), cannabigerolic acid (CBGA), cannabicitran (CBT), cannabidivarin (CBDV), cannabichromene (CBC), and cannabinol (CBN) on AChE and BChE activities.

Methods

The inhibitory effects of cannabinoids on the activities of AChE and BChE enzymes were evaluated with the Ellman method using acetyl- and butyryl-thiocholines as substrates. The inhibition mechanism of cannabinoids on AChE and BChE was studied with enzyme kinetic assays including the Lineweaver-Burk and Michaelis-Menten analyses. In addition, computational-based molecular docking experiments were performed to explore the interactions between the cannabinoids and the enzyme proteins.

Results

Cannabinoids including CBD, Δ8-THC, CBG, CBGA, CBT, CBDV, CBC, and CBN (at 200 µM) inhibited the activities of AChE and BChE by 70.8, 83.7, 92.9, 76.7, 66.0, 79.3, 13.7, and 30.5%, and by 86.8, 80.8, 93.2, 87.1, 77.0, 78.5, 27.9, and 22.0%, respectively. The inhibitory effects of these cannabinoids (with IC<sub>50</sub> values ranging from 85.2 to >200 µM for AChE and 107.1 to >200 µM for BChE) were less potent as compared to the positive control galantamine (IC<sub>50</sub> 1.21 and 6.86 µM for AChE and BChE, respectively). In addition, CBD, as a representative cannabinoid, displayed a competitive type of inhibition on both AChE and BChE. Data from the molecular docking studies suggested that cannabinoids interacted with several amino acid residues on the enzyme proteins, which supported their overall inhibitory effects on AChE and BChE.

Conclusion

Cannabinoids showed moderate inhibitory effects on the activities of AChE and BChE enzymes, which may contribute to their modulatory effects on the cholinergic system. Further studies using cell-based and in vivo models are warranted to evaluate whether cannabinoids' neuroprotective effects are associated with their anti-cholinesterase activities.

Keywords: Cannabinoids, Cannabidiol, Acetylcholinesterase, Butyrylcholinesterase, Kinetic assays, Docking

Introduction

The cholinergic system is comprised of a wide distribution of neurons throughout the central nervous system which controls essential functions such as learning, memory, sleep, and stress regulation [1]. Cholinergic system dysfunctions are associated with neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Lewy body dementia, and atypical Parkinson's disease [2]. Further, cholinergic deficiency in the CNS induces cognitive deficits including attentional impairments [3]. Cholinergic neurotransmission is mediated by the hydrolysis of choline-based esters by acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) [4]. AChE is the most abundant cholinergic enzyme in the human body and is found in red blood cells, in the brain at the neuromuscular junction, and at neuronal synapses [5]. Additionally, the under-reported enzyme BChE is found in less abundance in widespread areas throughout the body, such as the liver, central nervous system, blood serum, and glial cells [5]. AChE specifically catalyzes acetylcholine, and BChE acts as a nonspecific modulatory cholinesterase hydrolyzing many choline esters, yet its function is not well established [5]. In AD, BChE is also associated with Aβ aggregates in key brain regions responsible for learning and memory decline, such as the hippocampus, cerebellum, amygdala, and cerebral cortex [6]. Further, cholinesterases also play a role in proper immune functioning, which is altered during neurodegeneration. The termination of the anti-inflammatory system is activated by AChE binding to erythrocytes, and BChE is also implicated due to its presence in blood serum [7]. Specifically, acetylcholine binds to the α 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor inducing immune mediators, and AChE and BChE terminate the anti-inflammatory pathway [7].

Due to the importance of cholinesterases to the nervous system and immune functioning, inhibitors targeting these enzymes are therapeutic modalities against neurodegenerative diseases. In a systematic review of randomized clinical trials, cholinesterase inhibitors were effective against cognitive decline in Parkinson's disease patients [8]. In addition, cholinesterase inhibitors comprise three out of the four drugs on the market approved to treat AD by the US FDA: galantamine, tacrine, and donepezil [7, 9]. Galantamine, an approved competitive inhibitor of AChE, is a naturally derived alkaloid compound [10]. Mechanistically, galantamine acts upon the allosteric site of nAChRs to increase acetylcholine populations which are deficient in AD [10]. Galantamine has been shown to improve the negative symptoms of neurodegeneration, such as memory, cognition, and everyday functioning in cases of mild-moderate dementia [10]. As of 2018, galantamine, from the Amaryllidaceae family, was the only natural product drug approved for AD treatment [7]. Therefore, there are limited natural product-based drugs targeting the cholinergic system to treat neurodegenerative diseases. Medicinal plants and their derived natural products are a promising avenue for the discovery of drugs against neurodegeneration due to their extensive structural diversity and demonstrated anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticancer effects [11]. Natural products have been previously studied for their mechanisms against cholinesterases and antioxidant activity [7].

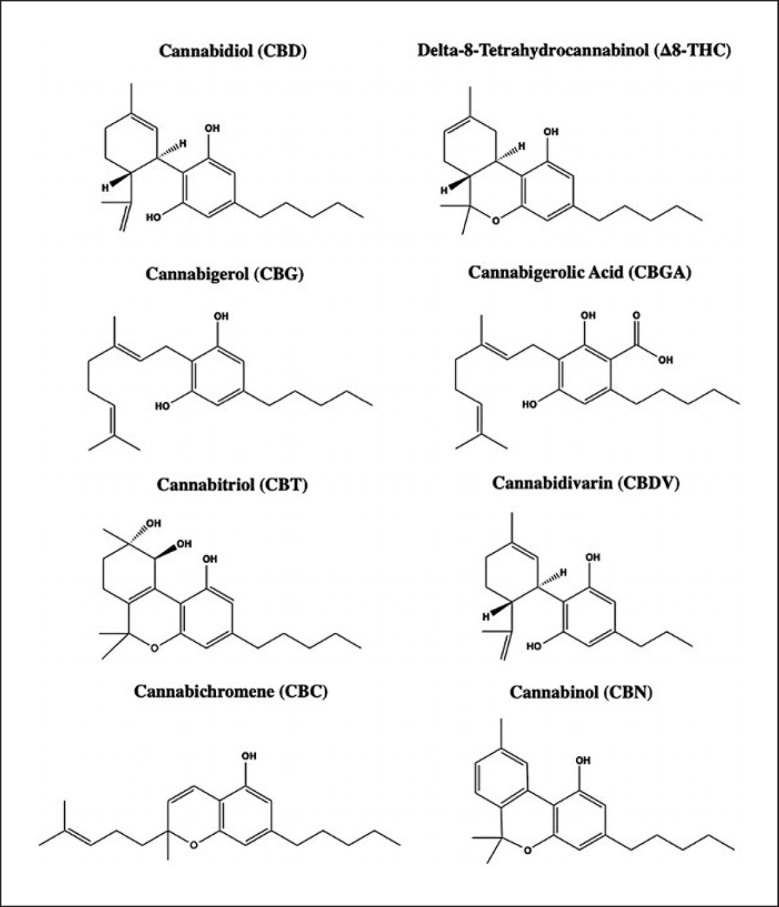

Previously published work from our group has shown that medicinal plants and their derived natural products show neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties. For instance, a maple syrup-derived extract demonstrated inhibition of neuroinflammatory markers related to neurodegeneration in vivo [12]. We also demonstrated that several medicinal plant extracts, most notably Mucuna pruriens (velvet bean), Punica granatum (pomegranate), and Curcuma longa (turmeric), showed inhibitory effects on AChE activity [13]. Notably, cannabinoids from Cannabis sativa (C. sativa) have been increasingly evaluated in studies to treat chronic pain, inflammation, multiple sclerosis, post-traumatic stress disorder, and neurological diseases, specifically AD [14]. Recently, our group reported that cannabidiol (CBD), a major nonpsychotropic compound in C. sativa, was shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory effects through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [15]. Cannabinoids have also garnered attention due to their interaction with the endocannabinoid system [16]. Specifically, CBD is considered a leading compound for the development of treatment for neurodegenerative diseases due to its neuroprotective effects and efficacy without psychotropic symptoms [17]. Furthermore, a study implicated that phytochemicals of C. sativa, including several cannabinoids, are inhibitors of AChE, which is supported by data obtained from computational modeling studies [18]. In addition, multiple cannabinoids have been reported to inhibit AChE and BChE in rat serum [19]. Furthermore, a recent study found that a methanolic extract of leaves showed inhibitory effects against both AChE and BChE, but the active compounds were not identified [20]. However, the inhibitory effects of cannabinoids against AChE and BChE activities, as well as their underlying mechanism of action, remain not clear. Therefore, our study sought to characterize the inhibitory effects of a panel of cannabinoids (see their chemical structures shown in Fig. 1), on the cholinesterases activities through in vitro spectrophotometric methods, kinetic assays, and molecular docking analyses.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of cannabinoids including CBD, Δ8-THC, CBG, CBGA, CBT, CBDV, CBC, and CBN.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Cannabinoids including CBD, Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabigerol (CBG), cannabigerolic acid (CBGA), cannabicitran (CBT), cannabidivarin (CBDV), cannabichromene (CBC), cannabinol (CBN), and galantamine were purchased from Cayman Chemical Co (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). AChE enzyme from Electrophorus electricus, BChE enzyme from equine serum, Ellman's reagent (5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid [DTNB]), acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCI), S-butyrylthiocholine iodide (BTCI), and Tris hydrochloride (Tris-HCl) buffer were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Enzyme Activity Assays

The inhibition of AChE and BChE by cannabinoids was evaluated using a spectrophotometric method with minor modifications [13]. Briefly, Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM; pH 8; 100 µL) and AChE or BChE enzyme (5 U/mL; 20 µL) were added to a 96-well plate. Next, each cannabinoid (including CBD, Δ8-THC, CBG, CBGA, CBT, CBDV, CBC, and CBN) in Tris-HCl buffer (20 µL) was added a well to reach to concentrations ranging from 25 to 200 µM. The 96-well plate was incubated in the dark for 20 min at 37°C. The DTNB solution (0.75 mM) was mixed with either ATCI (for AChE inhibition) or BTCI (for BChE inhibition) in a 1:2 ratio, and then the mixture (60 µL) was added to each well. The solutions were incubated for 5 min at room temperature, and the absorbance of each well was recorded at a wavelength of 405 nm using a microplate reader (SpectraMax M2, Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Galantamine (at concentrations ranging from 0.03 to 30 μg/mL), a competitive inhibitor for AChE and BChE, was used as the positive control, and the Tris-HCl buffer containing no cannabinoids was used as the blank control. The inhibition rate of each reaction was calculated using the following formula:

% Inhibition = ([ΔAbscontrol−ΔAbssample]/[ΔAbscontrol]) × 100

Kinetics of AChE and BChE Inhibition

CBD, a representative cannabinoid, was selected for further studies of cannabinoids' enzyme inhibition mechanism using a kinetic assay as previously reported with minor modifications [21]. Briefly, a mixture of Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM; 100 µL), AChE or BChE enzyme (5 U/mL; 20 µL), CBD (50 and 150 µM; 20 µL), DTNB (0.75 mM 40 µL), and substrate (ATCI or BTCI, respectively; concentrations of 0.0625, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 mM; 20 µL) were added to a 96-well plate. The absorbance of each well was recorded at a wavelength of 405 nm using a microplate reader (SpectraMax M2, Molecular Devices Corp.,). The kinetic parameters including the Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) and maximum reaction velocity (Vmax) were obtained from the nonlinear regression (curve fit) Michaelis-Menten plots. The Lineweaver-Burk plots were obtained by plotting the inverse substrate concentrations versus the inverse of the reaction rate.

Molecular Docking Analysis

Molecular docking experiments were conducted to predict the theoretical binding affinities of cannabinoids to AChE and BChE enzyme proteins, and compared with galantamine (as a positive control). The chemical structures of all ligands were obtained from PubChem in a mol format, which was converted into a pdb file. The crystallographic 3D structure of the human AChE (PDB code: 5HFA) and BChE (PDB code: 6ESY) enzyme proteins was obtained from the RCSB PDB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org). Molecular docking software including the AutoDock Tools 1.5.6 and Biovia Discovery Studio Version 4.5 were used to predict the binding pockets. First, the protein and ligands were prepared by removing water and existing ligand molecules on the protein and adding polar hydrogens. A grid box was established according to the interactions which corresponded to the predicted binding pocket and enzyme active sites. The cannabinoid and galantamine ligands were docked to the AChE or BChE enzyme proteins. Next, the interactions between each ligand and the respective enzyme protein were analyzed via AutoDock Tools and Discovery Studio to obtain binding parameters including binding energy, final intermolecular energy, final total internal energy, torsional free energy, unbound system's energy, and the estimated inhibition constant.

Results

Cannabinoids Inhibit AChE and BChE Enzyme Activities

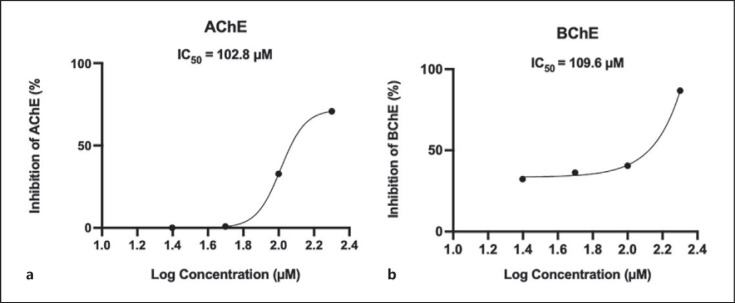

CBD (at concentrations of 25, 50, 100, and 200 µM) inhibited the activities of AChE and BChE enzymes in a concentration-dependent manner with inhibition rates of 0, 0, 32.8, and 70.8%, and 32.3, 36.3, 40.6, and 86.8%, respectively. The inhibition IC50 value of CBD on AChE and BChE were comparable (102.8 vs. 109.6 µM) (shown in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Inhibitory effects of CBD (at 25, 50, 100, and 200 µM) on AChE and BChE activities. The IC50 values were calculated using a nonlinear regression curve-fit analysis.

In addition, cannabinoids including Δ8-THC, CBG, CBGA, CBT, and CBDV also showed moderate inhibitory activity against AChE and BChE with an IC50 value of 91.7, 96.1, 92.7, 100.3, and 85.2 µM and 131.8, 107.1, 107.2, 117.5, and 119.9 µM, respectively (shown in Table 1). Two of the cannabinoids, namely, CBC and CBN, showed weak inhibitory activities against AChE and BChE with an inhibition rate of 13.7 and 30.5%, and 27.9 and 22.0%, respectively, at the concentration of 200 µM. The positive control, galantamine, showed inhibitory effects on AChE and BChE with an IC50 of 1.21 and 6.86 µM, respectively (shown in Table 1).

Table 1.

Cannabinoid inhibition of cholinesterase activity displayed by IC50 values and inhibition percentage at varied concentrations

| AChE |

BChE |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | IC50 | inhibition % at |

IC50 | inhibition % at |

|||||||

| μΜ | 25 μΜ | 50 μΜ | 100 μΜ | 200 μΜ | μΜ | 25 μΜ | 50 μΜ | 100 μΜ | 200 μΜ | ||

| Δ8-THC | 91.7 | 8.4 | 24.5 | 46.3 | 83.7 | 131.8 | 18.0 | 22.2 | 29.5 | 80.8 | |

| CBG | 96.1 | 26.5 | 35.8 | 65.5 | 92.9 | 107.1 | 14.3 | 12 | 20.8 | 93.2 | |

| CBGA | 92.7 | 13.2 | 19.9 | 51.4 | 76.7 | 107.2 | 31.3 | 38.5 | 43.8 | 87.1 | |

| CBT | 100.3 | 2.8 | 0 | 27.8 | 66.0 | 117.5 | 32.8 | 34.3 | 40.5 | 77.0 | |

| CBDV | 85.2 | 20.4 | 31.6 | 58.8 | 79.3 | 119.9 | 0 | 0 | 10.3 | 78.5 | |

| CBC | >200 | 0 | 0 | 7.7 | 13.7 | >200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27.9 | |

| CBN | >200 | 9.4 | 14.8 | 16.1 | 30.5 | >200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22.0 | |

| Galantamine | 1.2 | 9.2 | 12.8 | 63.7 | 96.6 | 6.9 | 2.4 | 9.2 | 55 | 83.5 | |

Galantamine is used as a positive control.

CBD Is a Competitive Inhibitor of AChE and BChE

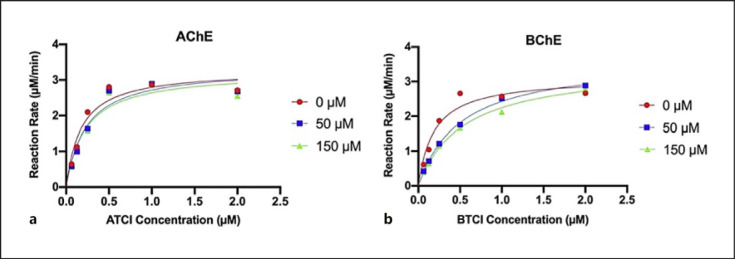

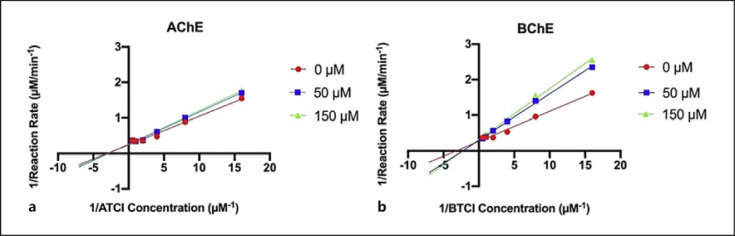

CBD as a representative cannabinoid was selected to study the mechanism of inhibition on AChE and BChE by analyzing its inhibition kinetics. The Michaelis-Menten plot of CBD's inhibition on AChE showed a slight reduction in reaction rate at two CBD concentrations (50 and 150 µM) suggesting that CBD inhibits AChE activity (shown in Fig. 3a). Similarly, for the kinetics of BChE inhibition, the Michaelis-Menten plot showed a greater reduction in reaction rate at 50 and 150 µM, suggesting that CBD inhibited BChE activity (shown in Fig. 3b). In addition, the Lineweaver-Burk plots of CBD's inhibition of AChE and BChE were constructed with two CBD concentrations near the IC50 (50 and 150 µM) and varying concentrations of substrate ATCI and BTCI (0.0625–2 µM) (shown in Fig. 4). The Lineweaver-Burk plots are double-reciprocal plots depicting comparable y-intercepts and a difference in slopes with CBD concentrations supporting a mode of competitive inhibition (shown in Fig. 4). CBD inhibition was not concentration dependent for either enzyme. This result of competitive inhibition was also supported by the kinetic inhibition parameters including constant maximal velocity (Vmax) and Michaelis constant (Km), in which Km values were increased with CBD concentrations of 50 and 150 µM as compared to control, and Vmax values remained relatively constant (shown in Table 2). Data obtained from the enzyme kinetic assays suggested that CBD is a competitive inhibitor of both cholinergic enzymes, AChE and BChE.

Fig. 3.

Michaelis-Menten kinetic plots of substrate concentration (µM) versus reaction rate (µM/min) for CBD concentrations of 0 µM, 50 µM, and 150 µM for AChE (a) and BChE (b).

Fig. 4.

Lineweaver-Burk kinetic plots of the inverse substrate concentration (µM-1) versus the inverse reaction rate (µM/min) for CBD concentrations of 0 µM, 50 µM, and 150 µM for AChE (a) and BChE (b).

Table 2.

CBD inhibition kinetics on cholinesterase activity

| AChE |

BChE |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| concentration, μΜ | Km, μΜ | Vmax, μΜ/min–1 | concentration, μΜ | μΜ | Vmax, μΜ/min–1 |

| 0 | 0.18 | 3.28 | 0 | 0.18 | 3.11 |

| 50 | 0.23 | 3.34 | 50 | 0.51 | 3.66 |

| 150 | 0.22 | 3.23 | 150 | 0.54 | 3.46 |

Km (µM) and Vmax (µM/min–1) values of CBD concentrations below and above the IC50, with ATCI/BTCI as the substrate.

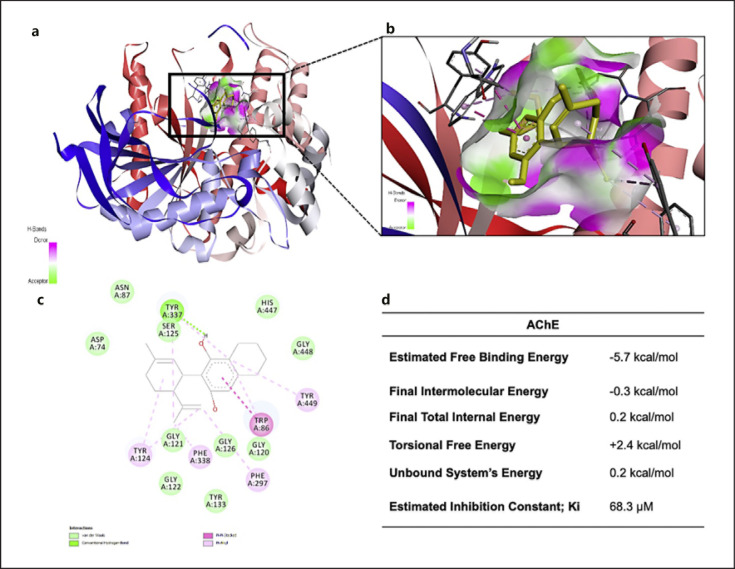

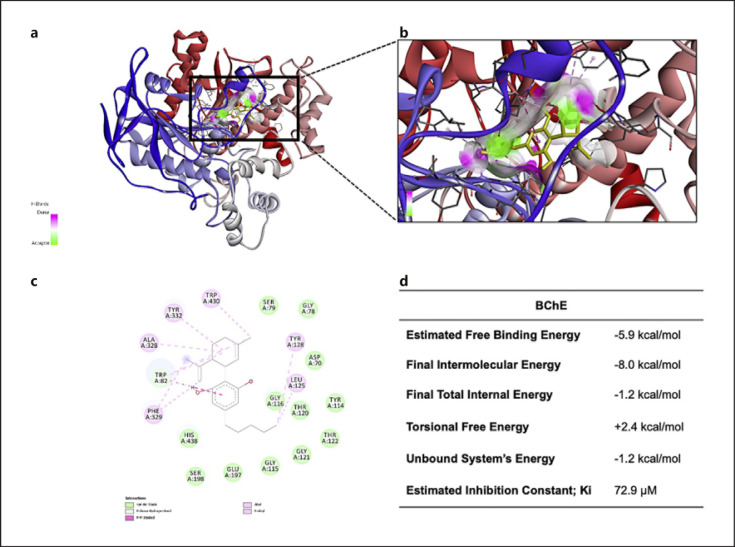

Cannabinoids Interact with AChE and BChE Enzyme Proteins

The mechanism of cannabinoids' inhibition on AChE and BChE was further explored by characterizing the ligand-protein binding interactions with molecular docking experiments in comparison with galantamine. As shown in Figure 5a and b, a suitable binding pocket of CBD on AChE protein was identified based on its theoretical binding energies and proximity to the AChE active site. The ligand-protein interaction analysis showed that CBD can bind to AChE protein by forming molecular forces, such as hydrogen bond and Pi-Pi stacked bond, with the protein's amino acid residues including TYR337 and TRP86, respectively (shown in Fig. 5c). Binding parameters of CBD and AChE, including binding energy, final intermolecular energy, final total internal energy, torsional free energy, unbound system's energy, and the estimated inhibition constants, are summarized in Figure 5d. Similarly, the binding pocket of CBD on BChE protein was identified by comparison of binding energies and association with the enzyme active site (shown in Fig. 6a,b). The ligand-protein complex was stabilized by bonding formed between CBD and BChE protein's amino acid residue TRP82, which formed Pi-donor hydrogen bonds and Pi-Pi stacked interactions (shown in Fig. 6c). A similar interaction was observed in the galantamine-BChE complex where binding force was formed between the ligand and amino acid TRP82. CBD's predicted binding parameters for BChE protein, such as estimated free binding energy, final intermolecular energy, final total internal energy, torsional free energy, unbound system's energy, and the estimated inhibition constant, are listed in Figure 6d.

Fig. 5.

Molecular docking of CBD to AChE displaying associated predicted interactions. The AChE enzyme is depicted in blue, white, and red. CBD is depicted in yellow, and H-bonds are indicated by pink (donor) and green (acceptor). a CBD docked to an AChE-binding pocket associated with the active site and enlarged depiction of the AChE-binding pocket with CBD (b). c Two-dimensional molecular binding interactions between CBD and AChE predicted by AutoDock Tools. d Summary of molecular docking binding parameters between CBD and AChE predicted by AutoDock Tools.

Fig. 6.

Molecular docking of CBD to BChE showing associated molecular interactions. The BChE enzyme is depicted in blue, white, and red. CBD is depicted in yellow, and H-bonds are indicated by pink (donor) and green (acceptor). a CBD docked to a BChE-binding pocket associated with the active site and enlarged depiction of the BChE-binding pocket with CBD (b). c Two-dimensional molecular binding interactions between CBD and BChE predicted by AutoDock Tools. d Summary of molecular docking binding parameters between CBD and BChE predicted by AutoDock Tools.

Additionally, the interactions between other cannabinoids (including CBT, CBGA, CBG, Δ8-THC, and CBDV) and enzyme (AChE and BChE) proteins were analyzed by obtaining their binding parameters at the same binding pocket as CBD's (shown in Table 3). Similar to CBD, these cannabinoids had comparable estimated binding parameters including free binding energy (ranging from −4.9 to −5.9 kcal/mol for AChE and −3.7 to −5.6 kcal/mol for BChE) and inhibition constant (ranging from 51.2 to 256.8 µM for AChE and 72.9–1,860 µM for BChE). In comparison, galantamine (a positive control) can bind to the same binding pocket as the cannabinoids for both AChE and BChE proteins with comparable binding energy (−8.17 and −5.07 kcal/mol, respectively) and inhibition constant (1.03 and 190.6 µM, respectively).

Table 3.

Molecular docking generated binding parameters between cannabinoids and AChE/BChE

| AChE |

BChE |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabinoid | free binding energy, kcal/mol | inhibition constant; Ki, μΜ | free binding energy, kcal/mol | inhibition constant, Ki, μΜ |

| Δ8-THC | –5.5 | 100 | –5.0 | 236.2 |

| CBG | –5.2 | 144.8 | –4.6 | 431.2 |

| CBGA | –4.9 | 256.8 | –3.7 | 1,860 |

| CBT | –5.4 | 106.1 | –5.4 | 112.2 |

| CBDV | –5.9 | 51.2 | –4.4 | 622.6 |

| Galantamine | –8.2 | 1.03 | –5.1 | 190.6 |

Galantamine is used as a positive control.

Discussion

Cannabinoids have been reported to show various health benefits, including neuroprotective effects against neurodegenerative diseases. However, research is lacking in terms of whether cannabinoids can alter the activities of cholinesterases, in the context of the AD cholinergic hypothesis. Cholinergic deficiency is a key component of AD pathology, leading to cognitive decline. The cholinergic hypothesis has led to increased development of cholinesterase inhibitors [9]. Anticholinesterases are currently leading therapeutic options due to their ability to increase cholinergic populations at the neuronal synapse which has shown to improve cognitive dysfunctions in AD patients [7]. It is noted that natural product-derived AChE inhibitors have been studied as potential management for AD [22].

The evaluation of natural products with inhibitory activities against AChE and BChE has previously been studied with alkaloids, terpenes, flavonoids, and sterols [22]. However, the inhibition of cannabinoids on the enzyme activities of both AChE and BChE, and their mechanisms of action are not well studied. Therefore, we sought to explore the inhibitory effects of a panel of cannabinoids on both AChE and BChE activities. Data from the enzyme activity assays showed the inhibitory effects of cannabinoids against the cholinesterases AChE and BChE. Some cannabinoids displayed moderate inhibition (in the micromolar range) supporting their potential as lead compounds for the further development of cannabinoid-based therapeutics. All of the tested compounds exhibited a trend of a higher inhibition rate against AChE than BChE, suggesting that cannabinoids may have inhibition selectivity toward AChE, but further studies using cells- and animal-based models are needed to confirm this. It is noted that, apart from cannabinoids, other phytochemicals in Cannabis are reported to show anti-cholinesterase activity. For instance, flavonoids, a group of polyphenols commonly found in medicinal plants including Cannabis, are reported to show inhibitory effects on cholinesterase activity [23]. For example, flavonoids, such as quercetin and genistein, showed inhibitory effects on AChE and BChE activities, respectively [24]. In addition, essential oils derived from Cannabis showed in vitro anti-AChE effects [25]. Therefore, phytochemicals from Cannabis may collectively contribute to the overall inhibitory effects on cholinesterases of Cannabis extracts.

Molecular docking was utilized to explore possible binding interactions between cannabinoids and the two cholinesterase proteins. The computational data including the free binding energy for CBD binding to AChE were in agreement with a previously reported study (−5.7 vs. −7.6 kcal/mol) [18]. Further, the estimated inhibition constant (Ki) was comparable to data from the experimental assay (IC50 values). In addition, our docking data, showing that TYR337 residue was the binding site of AChE, and TYR124 is the peripheral anionic site, were supported by findings from a reported study [26]. Additionally, to date, this is the first study to show the inhibitory effects of minor cannabinoids on BChE enzyme activity, as well as the possible binding model of cannabinoids to BChE protein using a molecular docking method. Overall, data from the in vitro (enzyme inhibition assay) and in silico (molecular docking) experiments support cannabinoid selectivity toward the inhibition of AChE over BChE. The inhibitory effects of cannabinoids on AChE and BChE are less potent as compared to the known natural product-based selective AChE inhibitor (i.e., galantamine) [27], suggesting that further studies are required to modify the structures of cannabinoids for enhanced anti-AChE activity. In addition, further studies using cell-based in vitro assays and in vivo models are warranted to evaluate the anti-cholinesterase effects of cannabinoids and to elucidate their mechanism of action. Notably, CBD has also been identified as a reversible inhibitor of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor that increases the acetylcholine level in rats [24]. Further, inhibition of cholinesterases increases the acetylcholine level at the synaptic cleft in various brain regions, which is associated with a decline of acetylcholine populations due to AD progression [25]. Restoring cholinergic transmission and mediating the endocannabinoid system may also be accounted for the alleviation of the AD symptoms associated with memory and cognitive decline [25]. Further pharmacological studies are warranted to investigate the potential effects of cannabinoids on the acetylcholine system and their potential development as a management of AD.

Conclusion

In summary, several cannabinoids exhibited moderate inhibitory effects against the activities of cholinesterases including AChE and BChE. In addition, enzyme kinetic studies suggested that CBD is a competitive inhibitor of both AChE and BChE. Further mechanistic studies using molecular docking methods explored the binding capacity between cannabinoids and AChE and BChE proteins. Findings from the experimental- and computational-based assays suggested that cannabinoids are more selective for the inhibition of AChE, which shed light on the development of cannabinoids-based treatment for neurodegenerative diseases but further cells- and animal-based studies are warranted to evaluate cannabinoids' efficacy.

Statement of Ethics

No human subjects or animal experiments were involved in this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No external funding received for this study.

Author Contributions

T.P. conducted the enzymatic assays and molecular docking experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript draft. C.L. supervised the enzymatic assays and molecular docking experiments. H.M. and N.P.S. conceived, designed the overall project, and edited the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data obtained in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Spectrophotometric data were obtained from equipment and services located at the RI-INBRE Centralized Research Core Facility at the University of Rhode Island in Kingston, RI, USA. The RI-INBRE Core Facility is funded by the Institutional Development Award (IDeA) Network for Biomedical Research Excellence from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institute of Health under grant number P20GM103430.

References

- 1.Ferreira-Vieira HT, Guimaraes MI, Silva RF, Ribeiro MF. Alzheimer's disease: Targeting the cholinergic system. Cur Neuropharmacol. 2016 Jan 22;14((1)):101–15. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666150716165726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pepeu G, Grossi C, Casamenti F. The brain cholinergic system in neurodegenerative diseases. Arrb. 2015 Jan 10;6((1)):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane RM, Potkin SG, Enz A. Targeting acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase in dementia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005 Aug 5;9((01)):101. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705005833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao T, Ding KM, Zhang L, Cheng XM, Wang CH, Wang ZT. Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activities ofβ-carboline and quinoline alkaloids derivatives from the plants of genuspeganum. J Chem. 2013;2013:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mushtaq G, Greig NH, Khan JA, Kamal MA. Status of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase in Alzheimer's disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014 Nov 21;13((8)):1432–9. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666141023141545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darvesh S, Cash MK, Reid GA, Martin E, Mitnitski A, Geula C. Butyrylcholinesterase is associated with β-amyloid plaques in the transgenic APPSWE/PSEN1dE9 mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012 Jan 1;71((1)):2–14. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31823cc7a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dos Santos TC, Gomes TM, Pinto BAS, Camara AL, Paes AMA. Naturally occurring acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and their potential use for Alzheimer's disease therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2018 Oct 18;9:1192. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pagano G, Rengo G, Pasqualetti G, Femminella GD, Monzani F, Ferrara N, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015 Jul;86((7)):767–73. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valasani KR, Chaney MO, Day VW, ShiDu Yan S. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: structure based design, synthesis, pharmacophore modeling, and virtual screening. J Chem Inf Model. 2013 Aug 26;53((8)):2033–46. doi: 10.1021/ci400196z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott LJ, Goa KL. Galantamine: a review of its use in Alzheimer's disease. Drugs. 2000 Nov;60((5)):1095–122. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan RA. Natural products chemistry: the emerging trends and prospective goals. Saudi Pharm J. 2018 Jul;26((5)):739–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose KN, Barlock BJ, DaSilva NA, Johnson SL, Liu C, Ma H, et al. Anti-neuroinflammatory effects of a food-grade phenolic-enriched maple syrup extract in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nutr Neurosci. 2021 Sep 2;24((9)):710–9. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2019.1672009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W, Ma H, DaSilva NA, Rose KN, Johnson SL, Zhang L, et al. Development of a neuroprotective potential algorithm for medicinal plants. Neurochem Int. 2016 Nov;100:164–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klimkiewicz A, Jasinska A. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids. Psychiatria. 2018 Jun 27;15((2)):88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu C, Ma H, Slitt AL, Seeram NP. Inhibitory effect of cannabidiol on the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome is associated with its modulation of the P2X7 receptor in human monocytes. J Nat Prod. 2020 Jun 26;83((6)):2025–9. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bielawiec P, Harasim-Symbor E, Chabowski A. Phytocannabinoids: useful drugs for the treatment of obesity? Special focus on cannabidiol. Front Endocrinol. 2020 Mar 4;11:114. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iuvone T, Esposito G, de Filippis D, Scuderi C, Steardo L. Cannabidiol: a promising drug for neurodegenerative disorders? CNS Neurosci Ther. 2009 Mar;15((1)):65–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furqan T, Batool S, Habib R, Shah M, Kalasz H, Darvas F, et al. Cannabis constituents and acetylcholinesterase interaction: molecular docking, in vitro studies and association with CNR1 rs806368 and ACHE rs17228602. Biomolecules. 2020 May 13;10((5)):758. doi: 10.3390/biom10050758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdel-Salam OME, Ome AS, Ya K. The inhibition of serum cholinesterases by cannabis sativa and/or tramadol OPEN ACCESS [Internet] J Neurol Forecast. 2019;2 Available from: https://scienceforecastoa.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karimi I, Yousofvand N, Hussein BA. In vitro cholinesterase inhibitory action of Cannabis sativa L. Cannabaceae and in silico study of its selected phytocompounds. In Silico Pharmacol. 2021 Dec 21;9((1)):13. doi: 10.1007/s40203-021-00075-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma H, Wang L, Niesen DB, Cai A, Cho BP, Tan W, et al. Structure activity related, mechanistic, and modeling studies of gallotannins containing a glucitol-core and α-glucosidase. RSC Adv. 2015;5((130)):107904–15. doi: 10.1039/C5RA19014B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed F, Ghalib R, Sasikala P, Mueen Ahmed K. Cholinesterase inhibitors from botanicals. Pharmacogn Rev. 2013;7((14)):121–30. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.120511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uriarte-Pueyo II, Calvo M. Flavonoids as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18((34)):5289–302. doi: 10.2174/092986711798184325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orhan I, Kartal M, Tosun F, Sener B. Screening of various phenolic acids and flavonoid derivatives for their anticholinesterase potential. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2007;62((11–12)):829. doi: 10.1515/znc-2007-11-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smeriglio A, Trombetta D, Alloisio S, Cornara L, Denaro M, Garbati P, et al. Promising in vitro antioxidant, anti-acetylcholinesterase and neuroactive effects of essential oil from two non-psychotropic Cannabis sativa L. biotypes. Phytother Res. 2020;34((9)):2287–302. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhananjayan K, Sumathy A, Palanisamy S. Molecular docking studies and in-vitro acetylcholinesterase inhibition by terpenoids and flavonoids. Asian J Research Chem. 2013;6((11)):1011–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harvey AL. The pharmacology of galanthamine and its analogues. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;68((1)):113–28. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)02002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data obtained in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.