Abstract

Meaningful reductions in racial and ethnic inequities in chronic diseases of aging remain unlikely without major advancements in the inclusion of minoritized populations in aging research. While sparse, studies investigating research participation disparities have predominantly focused on individual-level factors and behavioral change, overlooking the influence of study design, structural factors, and social determinants of health on participation. This is also reflected in conventional practices that consistently fail to address established participation barriers, such as study requirements that impose financial, transportation, linguistic, and/or logistical barriers that disproportionately burden participants belonging to minoritized populations. These shortcomings not only risk exacerbating distrust toward research and researchers, but also introduce significant selection biases, diminishing our ability to detect differential mechanisms of risk, resilience, and response to interventions across subpopulations. This forum article examines the intersecting factors that drive both health inequities in aging and disparate participation in aging research among minoritized populations. Using an intersectional, social justice, and emancipatory lens, we characterize the role of social determinants, historical contexts, and contemporaneous structures in shaping research accessibility and inclusion. We also introduce frameworks to accelerate transformative theoretical approaches to fostering equitable inclusion of minoritized populations in aging research.

Keywords: Chronic illness; Disparities (health, racial); Diversity and ethnicity; Research participation

Chronic diseases of aging disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minoritized populations, who are more likely to develop and die from age-related conditions including cardiovascular and cardiopulmonary disease, type 2 diabetes, cancers, and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (Hill et al., 2015). Minoritized populations, particularly those who are older, are also at greater risk for contracting and experiencing poorer outcomes due to coronavirus disease 2019 (Walubita et al., 2021). They also frequently experience suboptimal treatment and care when they seek assistance (Artiga et al., 2020; Institute of Medicine, 2003). These intersecting and cumulative disparities in risk exposure, disease severity, and care quality compound persistent inequities across the life span, including life expectancy and health-related quality of life (Singh et al., 2017). Despite their disproportionate risk for poorer age-related health outcomes, minoritized older adults (i.e., older adults who belong to racial and ethnic minoritized communities) are perpetually underincluded in aging research (National Institutes of Health [NIH], 2019). We use the term minoritized throughout this forum article as, unlike the term minority, it highlights that certain groups are rendered into a minority rather than assuming that individuals are minorities based on features of their identity.

The importance of including minoritized groups in health research has been recognized for decades, with NIH policies encouraging inclusion since the mid-1980s (Taylor, 2008). These policies were extended and formalized by the passage of the Revitalization Act of 1993 (PL 103-43), which mandated the inclusion of racial/ethnic minorities and women in research. Despite explicit requirements for inclusion and reporting outlined in these policies, the past 28 years have yielded minimal improvements—and the aging field is no exception (Brewster et al., 2019).

Disparities in research inclusion among minoritized older adults have been traditionally conceptualized as simple, ahistorical or without context, and/or with vague constructs, such as “mistrust,” that often lay outside of scientific inquiry and institutional or investigator obligation (Jaiswal & Halkitis, 2019). Efforts to improve recruitment and retention of minoritized older adults in aging research have not been implemented systematically and frequently lack explicit theoretical or empiric direction (Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al., 2019). The resulting and continued inadequate diversity in aging research has become increasingly apparent as minoritized older adults constitute the fastest-growing demographic in the United States, but interventions capable of alleviating late-life health disparities remain elusive or nongeneralizable to these populations (Zimmerman & Anderson, 2019). Ultimately, underinclusion of populations with the greatest burden of disease obfuscates efforts to elucidate and better understand underlying disease pathologies, risk, and protective factors that underlie age-associated conditions and introduce substantial selection biases that threaten both internal and external validity (Deters et al., 2021; Gleason et al., 2019). Beyond the scientific necessity of inclusive research is the ethical imperative of justice, which has garnered increasing attention among scholars and advocacy organizations (Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al., 2021; Resendez & Monroe, 2020). Fulfilling justice in research is foundational to cultivating practices that promote health equity through an equal valuation of the well-being of all persons, the correction of injustices, and providing resources according to need, rather than impartially, to facilitate access to research (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019).

The science of inclusion—encompassing engagement, recruitment and retention, shared decision making, and participant agency—has reemerged in recent years as a field evolving rapidly to provide a base of foundational theory and empirical evidence in this area (Glover et al., 2018; Griffith et al., 2021; Lincoln et al., 2021; Shin & Doraiswamy, 2016). This forum article responds to the ongoing and urgent need for robust discussion and critical analysis of scientific inclusion of racial and ethnic minoritized communities in aging research. We summarize approaches to understanding research participation among minoritized older adults and articulate the need for more historically situated, sociopolitical frameworks for addressing accessibility, participation, and inclusivity in aging research. We aim to stimulate discussion regarding the role of structural and social determinants, historical and contemporary discrimination, and racial hegemony—the dominance and privilege one racial group is conferred over others—in perpetuating a research enterprise that still largely excludes those with the greatest burden of disease (Omi & Winant, 2015). Our forum concludes with a discussion of emergent frameworks for fostering equitable inclusion of racial and ethnic minoritized populations in aging research. We believe that, despite the dedicated efforts of many scientists, disparities endured by minoritized older adults will persist absent deep and critical reflection into our approaches, and the myriad implicit assumptions that underpin them.

Participation of Minoritized Older Adults in Aging Research: The Science of Inclusion

In 2003, The Gerontologist published a collection of papers in a Special Issue entitled “The Science of Inclusion” edited by Leslie Curry, PhD and James Jackson, PhD, which called for the establishment of an empirical science of recruitment and retention (Curry & Jackson, 2003). A subsequent 2011 Special Issue on “The Science of Recruitment and Retention among Ethnically Diverse Populations” edited by Peggye Dilworth-Anderson, PhD presented additional studies outlining strategies and models of recruitment and retention, covering the use of community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches, community advisory boards, attention to relationships, and trust (Dilworth-Anderson, 2011).

Across several seminal publications, these scholars identified the importance of adopting methodologically rigorous, theoretically informed strategies to foster participation of minoritized older adults in research, and transitioning toward an empiric rather than anecdotal approach to understanding the science of inclusion (Curry & Jackson, 2003; Dilworth-Anderson, 2011; Dilworth-Anderson & Cohen, 2010). The past 20 years have seen a consistent, though small, evolution of published studies and other reports focused largely on (a) nonempiric reports of recruitment strategies or techniques (frequently site-specific reports of “lessons learned”); (b) descriptive studies evaluating individual-level beliefs, attitudes, and willingness to participate in research; (c) qualitative and survey-derived appraisals of barriers and facilitators to study enrollment and participation; and (d) research participation decision making (Areán et al., 2003; Ford et al., 2008; George et al., 2014; Mody et al., 2008; UyBico et al., 2007; Yancey et al., 2006). These represent important contributions and insights but have encompassed very few rigorous empiric evaluations of strategies or approaches—and as such have not yet yielded actionable knowledge capable of producing more inclusive research practices.

While many of these studies and reports may be shaped by implicit theoretical assumptions, such as those congruent with CBPR approaches, explicit descriptions of theories of participation, engagement, and inclusion are sparse. This is where we focus our attention. Using an emancipatory and social justice praxis, we suggest that underinclusion in research represents a specific form of social exclusion, which for minoritized older adults is juxtaposed against a lifetime of unequal participation and opportunity. We understand emancipatory and social justice perspectives as constituting a critical social analysis (Fairclough, 2013) rooted in the pursuit of emancipation from “constraints of privileged dominant health and social discourses and practices” (Kagan et al., 2014, p. 2). This pursuit is supported by a critical analysis of historical and current social environments and the fundamental determinants that underpin them. We posit that effective interventions to address participation disparities necessitate both progress in an empiric science of inclusion and in a critical interrogation of the sociopolitical determinants of exclusion across multiple levels of influence.

Conceptualizing Exclusion

While sparse, studies on research participation decision making among minoritized older adults have largely emphasized individual-level factors, such as participant attitudes and beliefs toward research, religiosity, and willingness. These individual-level factors are often removed from broader historical, structural, and social contexts that shape accessibility and participatory actions. Broadly, a decision-making discourse focused on individual participant-level factors such as these implicitly imposes a unidirectional moral obligation on participants to align their interests and goals with those of investigators and their institutions while it frees those institutions from their own obligations and shortcomings. Furthermore, compelling evidence suggests that although minoritized participants may hold different attitudes toward research than White participants, they are not less willing to participate in research—suggesting that other factors beyond interindividual differences drive participation (Areán et al., 2003; Ford et al., 2008; George et al., 2014; Mody et al., 2008; UyBico et al., 2007; Yancey et al., 2006). Hence, the need exists to examine the underinclusion of minoritized older adults in aging research from a structural (beyond the individual) perspective.

Labeling inclusion also necessitates careful labeling of exclusion and its historical and contemporaneous origins. Many minoritized older adults encounter aging and age-related health needs over the backdrop of a life course of systematic social exclusion (Mathieson et al., 2008). The concept of systematic social exclusion specifies the dynamic interplay between processes that beget unequal opportunity, surrounding the power relationships and the dimensions of deprivation and disadvantage that result from exclusion.

A primary consequence of social exclusion is social deprivation (Chandola & Conibere, 2015), which manifests as systematic denial of social capital whereby expectations of trustworthiness and reciprocity interwoven into daily life are differentially shaped based on race, gender, class, and ability (Putnam, 2000). Similar to (and reinforced by) structural racism, systematic social exclusion yields multiple, interlocking disadvantages that ultimately operate across levels of influence that we can understand as mechanisms of exclusion. Social exclusion extends into institutional settings responsible for leading research efforts. Sustained underinclusion of minoritized older adults in aging research may be perpetuated in part by deeply entrenched and largely “invisible” norms of social exclusion fostered within institutions. Institutional norms may benefit from the invisibility of “productive ignorance” that discourages open discourses that could disrupt established practices and policies that foster exclusion from research participation among minoritized groups (Perron & Rudge, 2015). In other words, practices that contribute to underinclusion operate at multiple levels beyond the individual participant and researcher or research center. Yet, interventions to address participation are almost exclusively designed and implemented at the individual participant level and rarely address the larger systems and structures that may be operating and driving exclusion behind the scenes.

How Does Participation Happen?

A persistent gap in knowledge is the lack of understanding regarding how research participation decisions, and ultimately participation, occur. In any given situation, an individual’s attitudes, beliefs, and general degree of willingness may not be sufficient to produce research participation. A theoretical understanding of how research participation happens, centering the lived experience of minoritized older adults, is needed to tailor recruitment strategies to specific vulnerabilities along the decision-making process. Participation decisions are both situation-specific and rooted in broader historical contexts and contemporaneous structures, such as structural racism, ageism, xenophobia, and other forms of discrimination.

As such, research participation has been shaped by well-known and lesser-known human rights and ethical violations carried out on predominantly minoritized and impoverished persons. These include the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, the Guatemalan Syphilis Study, and numerous other unethical experiments (Washington, 2006). The U.S. Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, in particular, is commonly referenced as a major cause of distrust toward research, particularly among African American participants (Millet et al., 2010). Recently, scholars have argued that the U.S. Syphilis Study is too often invoked as a rationale for ongoing low participation among minoritized groups and that it is important to highlight that medical mistrust is not only based on historical traumas, but on ongoing disrespect, devaluation, and discrimination toward minoritized communities (Boyd et al., 2020; Jaiswal & Halkitis, 2019; Scharff et al., 2010). In fact, findings from qualitative and survey studies identify the U.S. Syphilis Study as just one element among a lifetime of discrimination contributing to skepticism and distrust (Bates & Harris, 2004; Brandon et al., 2005; Scharff et al., 2010). Furthermore, mistrust is misunderstood to exist primarily within the individual or community level; rather, mistrust is mired within a system that perpetuates racism and inequity. In viewing mistrust as a phenomenon created and maintained at the individual and community level, rather than a byproduct of racist and inequitable systems, culpability for trust is inappropriately placed on minoritized individuals and communities rather than investigators and institutions (Jaiswal & Halkitis, 2019). Minoritized groups are effectively and paradoxically blamed for their responses to past abuse and burdened with the need to be the solution to a problem they did not create. Conversely, investigators and institutions are not held to a sufficiently high standard for demonstrating the trustworthiness necessary to begin to repair prior and current abuses (Jaiswal & Halkitis, 2019).

Minoritized older adults face broader historical and contemporaneous structural determinants perpetuated by and across institutions, including health care. These include direct or familial experiences with Black codes, lynching, segregation, internment camps, and forced sterilization, along with a life course of experiences with macro- and microaggressions and practices such as redlining and gentrification. Minoritized older adults have also experienced interpersonal and structural racism in the pursuit and receipt of health care, with their help-seeking behaviors commonly labeled as divergent or “nonadaptive” such as avoidant or noncompliant, which may lead to delayed care and reinforcement of existing disparities (Institute of Medicine, 2003).

Conceptualizing Inclusion: A Focus on Conceptualizations of Trust

The field of aging research is only beginning to question the rhetoric that shapes conceptualizations of trust in aging research. This rhetoric frequently casts blame and places the onus of responsibility for action and forgiveness on minoritized populations rather than on institutions and researchers and does not accurately identify underlying causes of mistrust. This is just one of many deceptively nuanced manifestations of racialized hegemonies that prioritize access to collective social processes, such as research, for White populations as a preferential and referent norm (Boyd et al., 2020; Portacolone et al., 2020; Scharff et al., 2010). This hegemony problematizes rather than engages diverse values and needs of minoritized populations. Centering White populations in research translates to culturally incongruent or underdeveloped recruitment strategies that, upon failure, label minoritized communities as “too costly” or “too difficult” to reach. Rather, centering the experiences and needs of minoritized older adults is fundamental to developing a social justice framework that recognizes the larger systemic context of past and ongoing abuses and that ultimately drives the bidirectional development of culturally meaningful and responsive outreach, recruitment, retention, and engagement.

Critical and reflective valuation of the lived experiences of minoritized older adults makes evident the inadequacy of situating research participation disparities around singular events and constructs, such as the U.S. Syphilis Study, mistrust, or even individual belief systems. These are important areas of investigation; however, conceptualizations of participation detached from the structural forces and hegemonic norms that foster the exclusion serve to maintain and reinforce these very structures. Ahistorical and acontextual approaches to fostering participation risk perpetuating a narrative that endorses expectations for participants to invest in research and perform “altruistic” acts for their family or community, that neither acknowledges nor responds to their concerns and specific needs. Practices that center and prioritize White, privileged populations that are normalized under White racial hegemony are more clearly identified as paradoxical and oppressive through the engagement of an intersectional and emancipatory praxis. The paradox is apparent in linking the residual divestment in the health of non-White communities with demands for their investment in institution-centered research goals, which further erodes the confidence and relationship building needed to foster trust.

The onus of “trust” is frequently placed on the participant. Recruitment strategies are often discussed as practices intended to help researchers fulfill their goals and are sometimes disbanded when even minimal goals or requirements are “met.” We propose that deeper paradigmatic shifts are needed to foster equitable inclusion through emancipatory, social justice-oriented approaches that require investigators and institutions to invest meaningfully and consistently in racial and ethnic minoritized communities. Critical theory positions trust not just as a person’s attribute to be cultivated, but as a feature of research accessibility. Progress toward investigator and institutional trustworthiness also requires a purposeful questioning of deeply fixed beliefs about the research itself—including the notion that the predominant purpose of research is to develop generalizable knowledge, recruitment strategies as nonscientific (e.g., community investment), and the absolved accountability of investigators to cultivate trust. This belief system propagates a set of policies and practices that situate community investment and related recruitment strategies as inherently nonscientific and shields investigators from making necessary community investment to cultivate trustworthiness. We suggest that this narrow conceptualization of research purpose and benefit comprises a hegemonic power that is principally designed to meet the research participation needs of predominantly White, English-speaking, privileged, and resourced populations. Designing participation pathways with minoritized populations at the center calls for a broader understanding of the value and function of research and of the interlocking and additive mechanisms that drive exclusion.

Mechanisms of Exclusion: Accessible for Whom?

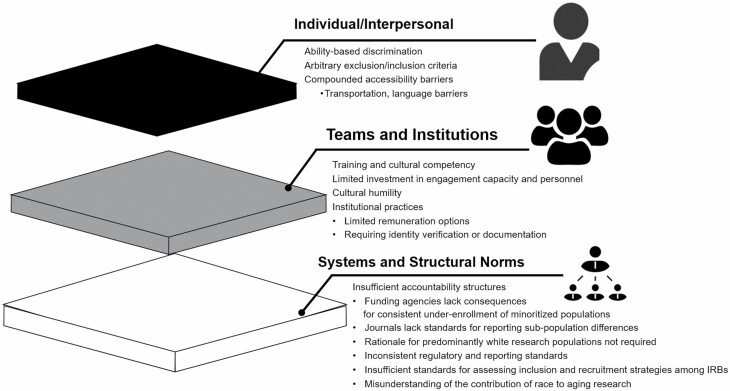

An important priority for future research is to disambiguate shared and distinct mechanisms driving exclusion, and the conditions under which they operate or are effectively interrupted. This will necessitate moving away from obscure notions of “challenges” and “strategies” and moving toward labeling, defining, and contextualizing the various functions of exclusionary norms. We can understand these mechanisms as operating at multiple intersecting levels of influence: individual/interpersonal, within teams and institutions, and in the broader systems and structures of research practices (Figure 1). Common examples of individual-level exclusionary practices include arbitrary exclusion criteria that disproportionally affect populations with higher chronic disease burden, ability-based description such as cognitive status, or study design features that limit participation to those with access to transportation or to those who speak English. Of note, while more than 67 million people in the United States speak a foreign language (Zeigler & Camarota, 2019), there is an increasing requirement for English fluency among clinical trials registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, particularly in areas with higher poverty rates (Egleston et al., 2015). Within study teams and institutions, interpersonal discrimination, lack of cultural humility (Lincoln et al., 2021), unwillingness to engage in activities to promote trustworthiness, and inflexible institutional policies such as limited options for participant remuneration may perpetuate underinclusion (Watson et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms that perpetuate exclusion from aging research across intersecting levels of influence.

Within the broader structures that shape the research enterprise, a consistent lack of accountability and guidance contributes to continued underinclusion and underreporting of systemic inequities. For example, it was not until 2016 that the Food and Drug Administration issued guidance on the collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials (Food and Drug Administration, 2016). Participation opportunities are distributed unequally across all stages of the research process in part because the opportunities to meet their requirements are unequally distributed in society—as is the case of varying experiences with the social determinants of health. For example, study requirements often impose inaccessible financial, transportation, or logistical challenges on participants, with minimal consideration to how unequally distributed these opportunities are. Minoritized older adults are also more likely to face financial, social, emotional, and logistical (i.e., time scarcity) consequences associated with caregiving or meeting their own health needs.

Next Steps: Advancing the Science of Inclusion Through Theory

Appropriate to its early stages, studies of the science of inclusion have focused largely on questions surrounding research recruitment, as a concrete and familiar stage in the process that may facilitate participation. As efforts to address broader historical and structural factors that shape participation grow, development and refinement of theoretical perspectives that are responsive to these constructs are needed to produce specific conceptual frameworks and resultant strategies and practices. We posit that such theoretical advancements will benefit from perspectives grounded in emancipatory and social justice praxis situated within an understanding of the lived experience of minoritized older adults broadly and with respect to research. To stimulate discussion and scholarship in this area, we conclude with a summary of common attributes and propositions within emergent conceptual frameworks and an illustrative example.

Emergent social justice-informed approaches to research engagement among minoritized older adults emphasize common attributes of reciprocity, investment, empowerment, and sustained bidirectional relationships that serve functions beyond those of researchers’ scientific goals. Two representative examples include an Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) approach (Green-Harris et al., 2019) and the NGAGE model, which refers to “Network, Give first, (then) Advocate for research, Give back, and Evaluate (related efforts)” (Denny et al., 2020). Both approaches emphasize first establishing community-based relationships and structures that address community-identified needs and facilitate communities’ strengths, all linked to knowledge-generation and material investments into racial and ethnic minoritized communities.

The ABCD approach is informed by Kretzmann and McKnight (1993) ABCD community-engagement principles and maintains that sustainable engagement results from (a) assessing the resources and skills available in communities, (b) organizing around issues that move community members into action, and (c) community members determining priorities and action steps. Similarly, the NGAGE model is a locally developed and team-based approach to developing and sustaining relationships with demographically diverse communities who are underincluded in aging research, such as African Americans/Blacks and Hispanics/Latinos. As a community-centered and participant-oriented approach, the NGAGE model engenders trust with diverse communities prior to any discussion of research participation. Furthermore, whether persons participate in research or not, the NGAGE model facilitates bidirectional and mutually beneficial exchanges of knowledge and resources between researchers and communities based on research findings and related information to, ultimately, build community capacity regarding healthy cognitive aging. Overall, these investments from these models and more serve to establish relationships that are mutually beneficial, reciprocal, and built on trust. These investments also offer a modicum of restorative justice regarding past and contemporaneous mistreatment and exclusion of minoritized older adults from research that can be authentically established, cultivated, and sustained over time. Empowerment recognizes community members as experts, validates, and acts upon their perspectives and expertise. An underlying proposition across these approaches is an assumption that it is the researchers’ responsibility to remediate sources of mistrust and other mechanisms that drive research exclusion such as inequitable distribution of benefits for research participation toward institutions rather than toward minoritized communities.

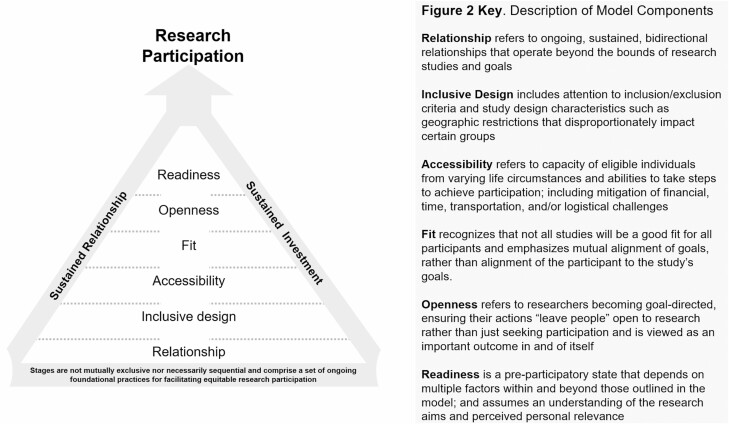

Another emergent model, the Participant and Relationship-Centered Research Engagement Model, views research as a form of relationship. This model extends intersectionality and social determinants frameworks to research participation by prioritizing participant needs and systematically addressing socioeconomic determinants (i.e., unmet needs) that may limit the accessibility to research (Figure 2). The model outlines six stages that facilitate research accessibility and inclusive participation: sustained relationship and investment, inclusive design, accessibility, fit, openness, and readiness. Research participation is situated as a by-product of these practices which aim to cultivate a sense of openness and readiness toward research opportunities. The model postulates that research relationships operate at and require cultivation across multiple levels: between individuals, between units such as a study team and an individual, and between institutions and individuals as well as their broader community. The model proposes that a series of outcomes result from sustained reciprocal relationships and investment, with openness toward research rather than participation serving as the end goal.

Figure 2.

The participant and relationship-centered research engagement model.

Considerable resources exist to help investigators identify approaches to cultivating bidirectional relationships through CBPR and community-owned and managed research practices. Attention to inclusive design can be fostered by engagement with minoritized older adults who may be better able to identify exclusionary practices. Studies require inclusive designs from inception, including attention to inclusion/exclusion criteria and study design characteristics such as geographic restrictions that disproportionately affect certain groups. Accessibility refers to the capability of eligible individuals from varying life circumstances and abilities to take the necessary steps to achieve participation; this includes institutional mitigation of the financial, time, transportation, and/or logistical challenges that disproportionately burden minoritized participants. Examples of practices that strengthen accessibility include providing participants flexible participation opportunities, such as respite care for caregivers, providing materials in participants’ preferred language and at an accessible reading level, access to transportation, access to research opportunities in local communities, and providing resource connections to address substantial unmet needs that limit participation. The domain of fit recognizes that not all studies will be a good fit for all participants: not all participants may value the study question, or be in a situation to accommodate participation even if they do value the study. Fit emphasizes mutual alignment of goals, rather than alignment of the participant to the study’s goals.

The model proposes that a series of outcomes result from sustained reciprocal relationships and investment, with openness toward research representing a more proximal endpoint than participation. Openness to learning about and engaging with research outside the act of participation is viewed as an important outcome in and of itself. Openness also refers to researchers becoming goal-directed, ensuring their actions “leave people open” to research rather than only seeking participation. Similarly, readiness is a preparticipatory state that depends on multiple factors within and beyond those outlined in the model. Readiness assumes an understanding of the research aims and perceived personal relevance. Participation is not the end goal but is self-renewing and sets up the next experience. Successful research participation is aligned and mutually beneficial for both the researcher and the participant. Ideally, participation perpetuates more openness to research through positive experiences, such as being recognized for contributions to research, learning about results and outcomes made possible through one’s participation, and having opportunities to be a part of a broader community of research participants.

The Participant and Relationship-Centered Research Engagement Model is being implemented and evaluated in the design of a research engagement intervention, the Brain Health Community Registry. The ABCD approach and the NGAGE model have similarly informed research engagement practices. Evaluation of the effectiveness of these models necessitates responsiveness to their underlying principles and assumptions, which call for integration of measures beyond research recruitment and retention. We are hopeful that further research and theory development in scientific inclusion will inform and strengthen these approaches as well methods for their evaluation.

Progress in alleviating health disparities among minoritized older adults will require considerable gains in their inclusion in aging research. As the science of inclusion continues to develop, paradigmatic shifts in how researchers view and operationalize research recruitment practices will benefit from emancipatory and social justice praxis that serve to disrupt the boundaries of frequently unquestioned practices and norms that perpetuate exclusion. It is our contention that this evolving field needs theoretical perspectives that move beyond unidimensional conceptualization of participation toward intersecting individual, institutional, and research systems-level practices and norms. We encourage and invite further scholarship, discussion, and critique regarding important features that shape participation practices including those not addressed in detail here, such as the role of industry, institutional, federal, and public reporting policies that can also contribute to shifting standards that prioritize inclusive and equitable aging research.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K76AG060005 to A.G.-B.). This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or the U.S. Government.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Areán, P. A., Alvidrez, J., Nery, R., Estes, C., & Linkins, K. (2003). Recruitment and retention of older minorities in mental health services research. The Gerontologist, 43(1), 36–44. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artiga, S., Orgera, K., & Pham, O. (2020). Disparities in health and health care: Five key questions and answers.Kaiser Family Foundation.https://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Disparities-in-Health-and-Health-Care-Five-Key-Questions-and-Answers [Google Scholar]

- Bates, B. R., & Harris, T. M. (2004). The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis and public perceptions of biomedical research: A focus group study. Journal of the National Medical Association, 96(8), 1051–1064. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, R. W., Lindo, E. G., Weeks, L. D., & McLemore, M. R. (2020). On racism: A new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog, 10. doi: 10.1377/hblog20200630.939347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon, D. T., Isaac, L. A., & LaVeist, T. A. (2005). The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: Is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(7), 951–956. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, P., Barnes, L., Haan, M., Johnson, J. K., Manly, J. J., Nápoles, A. M., Whitmer, R. A., Carvajal-Carmona, L., Early, D., Farias, S., Mayeda, E. R., Melrose, R., Meyer, O. L., Zeki Al Hazzouri, A., Hinton, L., & Mungas, D. (2019). Progress and future challenges in aging and diversity research in the United States. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 15(7), 995–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.07.221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandola, T., & Conibere, R. (2015). Social exclusion, social deprivation and health. In Wright J. D. (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (second edition) (pp. 285–290). Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.14087-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curry, L., & Jackson, J. (2003). The science of including older ethnic and racial group participants in health-related research. The Gerontologist, 43(1), 15–17. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny, A., Streitz, M., Stock, K., Balls-Berry, J. E., Barnes, L. L., Byrd, G. S., Croff, R., Gao, S., Glover, C. M., Hendrie, H. C., Hu, W. T., Manly, J. J., Moulder, K. L., Stark, S., Thomas, S. B., Whitmer, R., Wong, R., Morris, J. C., & Lingler, J. H. (2020). Perspective on the “African American participation in Alzheimer disease research: Effective strategies” workshop, 2018. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 16(12), 1734–1744. doi: 10.1002/alz.12160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deters, K. D., Napolioni, V., Sperling, R. A., Greicius, M. D., Mayeux, R., Hohman, T., & Mormino, E. C. (2021). Amyloid PET imaging in self-identified non-Hispanic Black participants of the anti-amyloid in asymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease (A4) study. Neurology, 96(11), e1491–e1500. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson, P. (2011). Introduction to the science of recruitment and retention among ethnically diverse populations. The Gerontologist, 51(Suppl. 11), S1–S4. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson, P., & Cohen, M. D. (2010). Beyond diversity to inclusion: Recruitment and retention of diverse groups in Alzheimer research. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 24(Suppl), S14–S18. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f12755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egleston, B. L., Pedraza, O., Wong, Y. N., Dunbrack, R. L., Jr, Griffin, C. L., Ross, E. A., & Beck, J. R., (2015). Characteristics of clinical trials that require participants to be fluent in English. Clinical Trials (London, England), 12(6), 618–626. doi: 10.1177/1740774515592881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis (pp. 35–46). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. (2016). Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials: Guidance for industry and food and drug administration staff (Report No. FDA-2016-D-3561). https://www.fda.gov/media/75453/download

- Ford, J. G., Howerton, M. W., Lai, G. Y., Gary, T. L., Bolen, S., Gibbons, M. C., Tilburt, J., Baffi, C., Tanpitukpongse, T. P., Wilson, R. F., Powe, N. R., & Bass, E. B. (2008). Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer, 112(2), 228–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, S., Duran, N., & Norris, K. (2014). A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), e16–e31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A., Jackson, J. D., & Wilkins, C. H. (2021). The urgency of justice in research: Beyond COVID-19. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 27(2), 97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A. L., Jin, Y., Gleason, C., Flowers-Benton, S., Block, L. M., Dilworth-Anderson, P., Barnes, L. L., Shah, M. N., & Zuelsdorff, M. (2019). Recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in Alzheimer’s disease research: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 5, 751–770. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, C. E., Norton, D., Zuelsdorff, M., Benton, S. F., Wyman, M. F., Nystrom, N., Lambrou, N., Salazar, H., Koscik, R. L., Jonaitis, E., Carter, F., Harris, B., Gee, A., Chin, N., Ketchum, F., Johnson, S. C., Edwards, D. F., Carlsson, C. M., Kukull, W., & Asthana, S. (2019). Association between enrollment factors and incident cognitive impairment in Blacks and Whites: Data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Center. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 15(12), 1533–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover, C. M., Creel-Bulos, C., Patel, L. M., During, S. E., Graham, K. L., Montoya, Y., Frick, S., Phillips, J., & Shah, R. C. (2018). Facilitators of research registry enrollment and potential variation by race and gender. Journal of Clinical and Translational Research, 2(4), 234–238. doi: 10.1017/cts.2018.326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green-Harris, G., Coley, S. L., Koscik, R. L., Norris, N. C., Houston, S. L., Sager, M. A., Johnson, S. C., & Edwards, D. F. (2019). Addressing disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and African-American participation in research: An asset-based community development approach. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 11, 125. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, D. M., Bergner, E. M., Fair, A. S., & Wilkins, C. H. (2021). Using mistrust, distrust, and low trust precisely in medical care and medical research advances health equity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 60(3), 442–445. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C. V., Pérez-Stable, E. J., Anderson, N. A., & Bernard, M. A. (2015). The National Institute on Aging Health Disparities Research Framework. Ethnicity & Disease, 25(3), 245–254. doi: 10.18865/ed.25.3.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care , Smedley, B. D., Stith, A. Y., & Nelson, A. R. (Eds.). (2003). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. National Academies Press (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, J., & Halkitis, P. N. (2019). Towards a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of medical mistrust informed by science. Behavioral Medicine, 45(2), 79–85. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2019.1619511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, P. N., Smith, M. C., & Chinn, P. L. (2014). Philosophies and practices of emancipatory nursing: Social justice as praxis. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kretzmann, J. P., & McKnight, J. L. (1993). Building communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community’s assets. Center for Urban Affairs and Policy Research, Neighborhood Innovations Network. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, K. D., Chow, T., Gaines, B. F., & Fitzgerald, T. (2021). Fundamental causes of barriers to participation in Alzheimer’s clinical research among African Americans. Ethnicity & Health, 26(4), 585–599. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2018.1539222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson, J., Popay, J., Enoch, E., Escorel, S., Hernandez, M., Johnston, H., & Rispel, L. (2008). Social exclusion: Meaning, measurement and experience and links to health inequalities: A review of literature. WHO Social Exclusion Knowledge Network Background Paper, 1, 91. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/media/sekn_meaning_measurement_experience_2008.pdf.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Millet, P. E., Close, S. K., & Arthur, C. G. (2010). Beyond Tuskegee: Why African Americans do not participate in research. In R. L. Hampton, T. P. Gullotta, & R. L. Crowel (Eds.), Handbook of African American health (pp. 51–79). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mody, L., Miller, D. K., McGloin, J. M., Freeman, M., Marcantonio, E. R., Magaziner, J., & Studenski, S. (2008). Recruitment and retention of older adults in aging research. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56(12), 2340–2348. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02015.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Keenan, W., Sanchez, C. E., Kellogg, E., & Tracey, S. M. (Eds.). (2019). Achieving behavioral health equity for children, families, and communities: Proceedings of a workshop. National Academies Press (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health . (2019). Report of the Advisory Committee on Research on Women’s Health, fiscal years 2017–2018: Office of Research on Women’s Health and NIH Support for Research on Women’s Health. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sites/orwh/files/docs/ORWH_BR_MAIN_final_508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Omi, M., & Winant, H. (2015). Racial formation in the United States. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Perron, A., & Rudge, T. (2015). On the politics of ignorance in nursing and health care: Knowing ignorance. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Portacolone, E., Palmer, N. R., Lichtenberg, P., Waters, C. M., Hill, C. V., Keiser, S., Vest, L., Maloof, M., Tran, T., Martinez, P., Guerrero, J., & Johnson, J. K. (2020). Earning the trust of African American communities to increase representation in dementia research. Ethnicity & Disease, 30(Suppl. 2), 719–734. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.S2.719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Resendez, J., & Monroe, S. (2020). A vision for equity in Alzheimer’s research in 2020. UsAgainstAlzheimer’s. https://www.usagainstalzheimers.org/blog/vision-equity-alzheimers-research-2020 [Google Scholar]

- Scharff, D. P., Mathews, K. J., Jackson, P., Hoffsuemmer, J., Martin, E., & Edwards, D. (2010). More than Tuskegee: Understanding mistrust about research participation. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 21(3), 879–897. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J., & Doraiswamy, P. M. (2016). Underrepresentation of African-Americans in Alzheimer’s trials: A call for affirmative action. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 8, 123. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G. K., Daus, G. P., Allender, M., Ramey, C. T., Martin, E. K., Perry, C., Reyes, A. A. L., & Vedamuthu, I. P. (2017). Social determinants of health in the United States: Addressing major health inequality trends for the nation, 1935–2016. International Journal of Maternal and Child Health and AIDS, 6(2), 139–164. doi: 10.21106/ijma.236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, H. A. (2008). Implementation of NIH inclusion guidelines: Survey of NIH study section members. Clinical Trials, 5(2), 140–146. doi: 10.1177/1740774508089457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UyBico, S. J., Pavel, S., & Gross, C. P. (2007). Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: A systematic review of recruitment interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(6), 852–863. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0126-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walubita, T., Beccia, A., Boama-Nyarko, E., Goulding, M., Herbert, C., Kloppenburg, J., Mabry, G., Masters, G., McCullers, A., & Forrester, S. (2021). Aging and COVID-19 in minority populations: A perfect storm. Current Epidemiology Reports, 8, 63–71. doi: 10.1007/s40471-021-00267-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington, H. A. (2006). Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present. Doubleday Books. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, B., Robinson, D. H., Harker, L., & Arriola, K. R. (2016). The inclusion of African-American study participants in web-based research studies: Viewpoint. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(6), e168. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey, A. K., Ortega, A. N., & Kumanyika, S. K. (2006). Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annual Review of Public Health, 27, 1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler, K., & Camarota, S. A. (2019). 67.3 million in the United States spoke a foreign language at home in 2018. Center for Immigration Studies, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, F. J., & Anderson, N. W. (2019). Trends in health equity in the United States by race/ethnicity, sex, and income, 1993–2017. JAMA Network Open, 2(6), e196386. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]