Abstract

Despite tremendous efforts in the past two years, our understanding of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), virus–host interactions, immune response, virulence, transmission, and evolution is still very limited. This limitation calls for further in-depth investigation. Computational studies have become an indispensable component in combating coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to their low cost, their efficiency, and the fact that they are free from safety and ethical constraints. Additionally, the mechanism that governs the global evolution and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 cannot be revealed from individual experiments and was discovered by integrating genotyping of massive viral sequences, biophysical modeling of protein–protein interactions, deep mutational data, deep learning, and advanced mathematics. There exists a tsunami of literature on the molecular modeling, simulations, and predictions of SARS-CoV-2 and related developments of drugs, vaccines, antibodies, and diagnostics. To provide readers with a quick update about this literature, we present a comprehensive and systematic methodology-centered review. Aspects such as molecular biophysics, bioinformatics, cheminformatics, machine learning, and mathematics are discussed. This review will be beneficial to researchers who are looking for ways to contribute to SARS-CoV-2 studies and those who are interested in the status of the field.

1. Introduction

Since its first case was identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has expeditiously spread to as many as 226 countries and territories worldwide and led to over 433 million confirmed cases and over 5.9 million fatalities as of February 2022. This pandemic has also brought a massive economic recession globally. Countries all around the world have implemented a variety of policies to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic (https://stip.oecd.org/covid/).

Many SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have already obtained use authorization worldwide (https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/science/coronavirus-vaccine-tracker.html). Additionally, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has given emergency use authorization to the oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor PAXLOVID (PF-07321332) developed by Pfizer1,2 (https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-receives-us-fda-emergency-use-authorization-novel). However, COVID-19 has a high infection rate, high prevalence, long incubation period,3 asymptomatic transmission,4−6 and potential seasonal patterns.7 SARS-CoV-2 keeps evolving into new infectious and antibody resistant variants.8−10 Therefore, it is imperative to understand the viral molecular mechanism,11 to track its genetic evolution,12 and to continuously improve the efficacy of its antiviral drugs and antibody therapies.

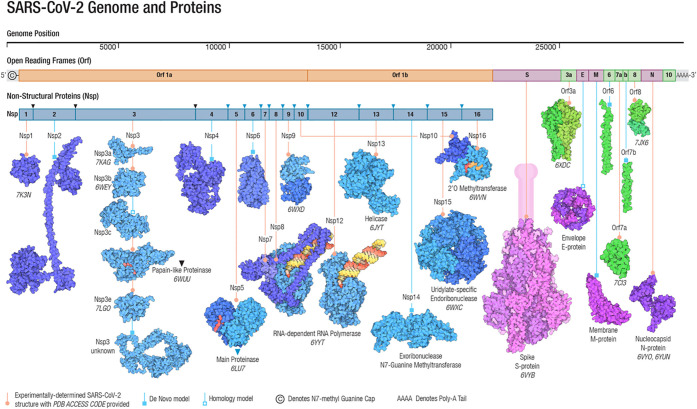

Belonging to the β-coronavirus genus and coronaviridae family, SARS-CoV-2 is an unsegmented positive-sense single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA) virus with a compact 29,903 nucleotide-long genome, and the diameter of each SARS-CoV-2 virion is about 50–200 nm.14 In the first 20 years of the 21st century, β-coronaviruses have triggered three major outbreaks of deadly pneumonia: SARS-CoV (2002), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (2012), and SARS-CoV-2 (2019).15 Like SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 also causes respiratory infections, but at a much higher infection rate.16,17 The complete genome of SARS-CoV-2 comprises 15 open reading frames (ORFs), which encodes 29 structural and nonstructural proteins (nsps), illustrated in Figure 1. The 16 nonstructural proteins nsp1–nsp16 get expressed by protein-coding genes ORF1a and ORF1b, while four canonical 3′ structural proteins, spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins, as well as accessory factors, are encoded by another four major ORFs, namely ORF2, ORF4, ORF5, and ORF9 (see Figure 1).18−21

Figure 1.

Genomics organization and proteins of SARS-CoV-2. Adapted with permission from ref (13). Copyright 2021 John Wiley and Sons.

The viral structure of SARS-CoV-2 can be found at the upper right corner of Figure 2. This structure is formed by the four structural proteins: the N protein holds the RNA genome, the S protein helps the virus enter into the host cell, and the M and E proteins define the shape of the viral envelope.22 The studies on SARS-CoV-2 as well as previous SARS-CoV and other coronaviruses have mostly identified the functions of these structural proteins, nonstructural proteins, as well as accessory proteins, which are summarized in Table 1. Their 3D structures are also largely known from experiments or predictions, which can be found in Figure 1.

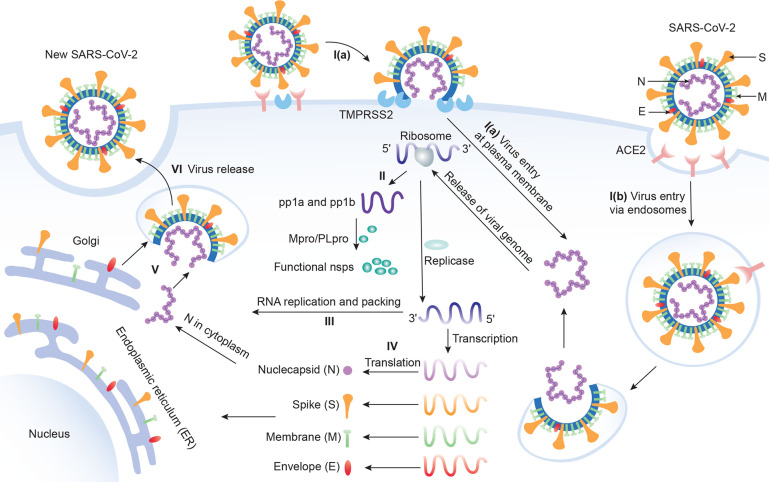

Figure 2.

Six stages of the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle. Stage I: Virus entry. I(a): Virus can enter the host cell via plasma membrane fusion. I(b): Virus can enter the host cell via endosomes. Stage II: Translation of viral replication. Stage III: Replication. Here, nsp12 (RdRp) and nsp13 (helicase) cooperate to perform the replication of the viral genome. Stage IV: Translation of viral structure proteins. Stage V: Virion assembly. Stage VI: Release of a virus.

Table 1. Descriptions of SARS-CoV-2 Proteins and 3D Structures.

| proteins | 3D structures |

|---|---|

| nsp1 (180 residues) inhibits host innate immune functions by interaction with the human 40S subunit in ribosomal complexes. Its carboxyl terminus (C-terminus) binds to and obstructs the ribosomal mRNA entry tunnel, thereby inhibiting the antiviral response triggered by innate immunity or interferons. The nsp1–40S ribosome complex further induces an endonucleolytic cleavage near the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) of host mRNAs, targeting them for degradation. By suppressing host gene expression, nsp1 facilitates efficient viral gene expression in infected cells and evasion from the host immune response.27 | nsp1: 7K7P (X-ray 1.77 Å),28 7K3N (X-ray 1.65 Å),29 7EQ4 (X-ray 1.25 Å),30 7OPL (cryo-EM 4.12 Å);31 nsp1–40S: 6ZOK (cryo-EM 2.80 Å), 6ZOL (cryo-EM 2.80 Å), 6ZOJ (cryo-EM 2.80 Å),27 etc. |

| nsp2 (638 residues) may play a role in the modulation of the host cell survival-signaling pathway by interacting with the host factors, prohibitin 1 and prohibitin 2, which are involved in maintaining the functional integrity of the mitochondria and protecting cells from various stresses. It appears that nsp2 could change the intracellular milieu and perturb host intracellular signaling.32 | 7MSX (cryo-EM 3.15 Å), 7MSW (cryo-EM 3.76 Å),32 etc. |

| nsp3 (1945 residues) includes the papain-like protease (PLpro) and some multipass membrane proteins. PLpro is responsible for cleaving and releasing nsp1, nsp2, and nsp3. PLpro also possesses a deubiquitinating/delSGylating activity and processes both “Lys-48”- and “Lys-63”-linked polyubiquitin chains from cellular substrates. It cleaves preferentially interferon stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) from substrates in vitro, which can play a role in host ADP-ribosylation by binding ADP-ribose. In addition, nsp3 participates together with nsp4 in the assembly of virally induced cytoplasmic double-membrane vesicles necessary for viral replication and antagonizes innate immune induction of type I interferon by blocking the phosphorylation, dimerization, and subsequent nuclear translocation of host interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3). It also prevents host NF-κB signaling.33,34 | Residues 819–929: 7KAG (X-ray 3.21 Å). Residues 1024–1192 (ADP-ribose phosphatase domain): 6WEY (X-ray, 0.95 Å),35 6WCF (X-ray 1.06 Å).36 Residues 1570–1877 (PLpro): 6W9C (X-ray 2.70 Å).37 Etc. |

| nsp4 (500 residues) is a multipass membrane protein. Together with nsp3, it participates in the assembly of virally induced cytoplasmic double-membrane vesicles, which is necessary for viral replication.38 | AlphaFold prediction.39 |

| nsp5 (306 residues) is the main protease (Mpro/3CLpro) of SARS-CoV-2. It takes charge of cleaving and releasing nsp4–nsp16. Additionally, it recognizes substrates containing the core sequence [ILMVF]-Q-|-[SGACN] and is also able to bind an ADP-ribose-1″-phosphate. Moreover, it plays a role in nsp maturation.22 | 6LU7 (X-ray 2.16 Å),40 etc. |

| nsp6 (290 residues) is a multipass membrane protein. Working with nsp3 and nsp4, it induces double-membrane vesicles (autophagosomes) in infected cells from their endoplasmic reticulum. It also limits the expansion of these autophagosomes that are no longer able to deliver viral components to lysosomes.41,42 | AlphaFold prediction.39 |

| nsp7 (83 residues) plays a role in viral RNA synthesis. It forms a hexadecamer with nsp8 that may participate in viral replication by acting as a primase. Alternatively, it may synthesize substantially longer products than oligonucleotide primers.43 | 6M5I (X-ray 2.50 Å), 7BV1 (cryo-EM 2.80 Å), 7BV2 (cryo-EM 2.50 Å)44 |

| nsp8 (198 residues) plays a role in viral RNA synthesis. It forms a hexadecamer with nsp7 that may participate in viral replication by acting as a primase. Alternatively, it may synthesize substantially longer products than oligonucleotide primers.43 | 6M5I (X-ray 2.50 Å), 7BV1 (cryo-EM 2.80 Å), 7BV2 (cryo-EM 2.50 Å).44 |

| nsp9 (113 residues) functions in viral replication as a dimeric ssRNA-binding protein.45 | 6W4B (X-ray 2.95 Å),46 6WXD (X-ray 2.00 Å),47 etc. |

| nsp10 (139 residues) plays a pivotal role in viral transcription. It forms a dodecamer and interacts with both nsp14 and nsp16 to stimulate their respective 3′-5′ exoribonuclease and 2′-O-methyltransferase activities in viral mRNAs that cap methylation.45 | 6ZCT (X-ray 2.55 Å),48 6ZPE (X-ray 1.58 Å),48 etc. |

| nsp11 (13 residues) is a pp1a cleavage product at the nsp10/11 boundary. For pp1ab, it is a frameshift product that becomes the N-terminal of nsp12. Its function, if any, is currently unknown.45 | None |

| nsp12 is the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) performing both replication and transcription of the viral genome. Specifically, it catalyzes the synthesis of the RNA strand complementary to a given RNA template. The RdRp of SARS-CoV-2 can be inhibited by the nucleoside analogue Remdesivir.45 | 6M71 (cryo-EM 2.90 Å),49 6YYT (cryo-EM 2.90 Å),50 etc. |

| nsp13 (Helicase) (932 residues) is a multifunctional superfamily 1 helicase capable of using both double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) as substrates with 5′-3′ polarity. In addition to working with nsp12 in viral genome replication, it is also involved in viral mRNA capping. It associates with nucleoprotein in membranous complexes.51 | 5RLH (X-ray 2.38 Å),49 6ZSL (X-ray 1.94 Å),52 etc. |

| nsp14 (601 residues) possesses two different activities: (1) an exoribonuclease activity on both single-strand RNA (ssRNA) and dsRNA in a 3′ to 5′ direction; (2) a N7-guanine methyltransferase (viral mRNA capping) activity. It acts as a proofreading exoribonuclease for RNA replication, thereby lowering the sensitivity of the virus to RNA mutagens.53 It always interacts with nsp10.45 | Exoribonuclease domain: 7DIY (X-ray 2.69 Å),54 7QGI (X-ray 1.65 Å), 7QIF (X-ray 2.53 Å), etc. |

| nsp15 (346 residues) is the nidoviral RNA uridylate-specific endoribonuclease (NendoU) that favors the cleavage of RNA at the 3′-ends of uridylates. The loss of nsp15 affects both viral replication and pathogenesis. It is also required for the evasion of host cell dsRNA sensors.55 | 6WLC (X-ray 1.82 Å),56 etc. |

| nsp16 (298 residues) is activated by and interacts with nsp10. Its 2′-O-methyltransferase activity mediates mRNA cap 2′-O-ribose methylation to the 5′-cap structure of viral mRNAs. Since N7-methyl guanosine cap is a prerequisite for binding of nsp16, it plays an important role in viral mRNAs cap methylation which is essential to evade the immune system. It may also work against host cell antiviral sensors.45 | 6W4H (X-ray 1.80 Å),57 etc. |

| ORF2 (Spike (S) protein) (1273 residues) binds to the host ACE2 receptor and internalizes the virus into the endosomes of host cells with the usage of human TMPRSS2 for priming in human lung cells. S protein consists of three chains and its stalk domain contains three hinges, giving the head unexpected orientational freedom. One single chain can be cleaved into two subunits, S1 and S2. S1 interacts with the host receptor, initiating the infection. S2 mediates fusion of the virion and cellular membranes by acting as a class I viral fusion protein. The current model of S protein has at least three conformational states: prefusion native state, prehairpin intermediate state, and postfusion hairpin state. During viral and target cell membrane fusion, the coil regions (heptad repeats) assume a trimer-of-hairpins structure, positioning the fusion peptide in close proximity to the C-terminal region of the ectodomain. The formation of this structure appears to drive apposition and subsequent fusion of viral and target cell membranes.25 | Spike protein: 6VSB (cryo-EM 3.46 Å),17 etc. RBD-ACE2 complex: 6VW1 (X-ray 2.68 Å),58 etc. |

| ORF3a (275 residues) is a multipass membrane protein that forms homotetrameric potassium sensitive ion channels (viroporin). It upregulates expression of fibrinogen subunits fibrinogen alpha (FGA), fibrinogen beta (FGB), and fibrinogen gamma (FGG) in host lung epithelial cells. It also induces apoptosis in cell culture. Additionally, ORF3a downregulates the type 1 interferon receptor by inducing serine phosphorylation within the interferon (IFN) alpha-receptor subunit 1 (IFNAR1) degradation motif and increases IFNAR1 ubiquitination. More importantly, it activates both NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome and contributes to the generation of the cytokine storm. It may also modulate viral release.59 | 6XDC (cryo-EM 2.9 Å),60 7KJR (cryo-EM 2.08 Å).60 |

| ORF3b (22 residues) along with nucleocapsid protein and ORF6 and ORF3b (22 residues) appears to block induction of type I interferons (IFN-I). This 22-residue variant is also present in SARS-CoV-2-related viral genomes in bats and pangolins.61 | None |

| ORF4 (Envelope (E) protein) (75 residues) is a single-pass type III membrane protein playing a central role in virus morphogenesis and assembly; it acts as a viroporin and self-assembles in host membranes forming pentameric protein–lipid pores that allow ion transport. It is also involved in the induction of apoptosis.62 | Residues 8–38: 7K3G (solid-state NMR)63 |

| ORF5 (Membrane protein) (222 residues) is the most abundant structural component of the virion and very conserved. It mediates morphogenesis, assembly, and budding of viral particles through the recruitment of other structural proteins to the ER-Golgi-intermediate compartment (ERGIC). It also interacts with N for RNA packaging into the virion.64 | AlphaFold prediction39 |

| ORF6 (61 residues) appears to be a virulence factor. It disrupts cell nuclear import complex formation by tethering karyopherin alpha 2 and karyopherin beta 1 to the membrane. Retention of import factors at the ER/Golgi membrane leads to a loss of transport into the nucleus, thereby preventing STAT1 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 1) nuclear translocation in response to interferon signaling and, thus, blocking the expression of ISGs that display multiple antiviral activities.65 | 7VPH (X-ray 2.8 Å)66 |

| ORF7a (121 residues) is a type I membrane protein that plays a role as an antagonist of bone marrow stromal antigen 2 (BST-2), disrupting its antiviral effect. As BST-2 tethers virions to the host’s plasma membrane, ORF7a binding inhibits BST-2 glycosylation and interferes with this restriction activity. ORF7a may suppress small interfering RNA (siRNA) and also may bind to host integrin, alpha L (ITGAL), thereby playing a role in attachment or modulation of leukocytes.67 | Residues 16–82: 6w37 (X-ray 2.90 Å) |

| ORF7b (43 residues) is a type III integral transmembrane protein in the Golgi apparatus. In SARS-CoV-2, it appears to be a viral attenuation factor. It may be involved in the human infectivity of SARS-CoV-2.68 | None |

| ORF8 (43 residues) might be a luminal ER membrane-associated protein. It may trigger the activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) activation and affect the unfolded protein response (UPR). Like ORF7b, it may be involved in the human infectivity of SARS-CoV-2.68−70 | 7JTL (X-ray 2.04 Å),71 etc. |

| ORF9a (N protein) (419 residues) packages the positive strand viral genome RNA into a helical ribonucleocapsid (RNP) and plays a fundamental role during virion assembly through its interactions with the viral genome and membrane protein. It also plays an important role in enhancing the efficiency of subgenomic viral RNA transcription as well as viral replication. It may modulate transforming growth factor-beta signaling by binding host smad3.21 | Residues 41–174: 6M3M (X-ray 2.70 Å),72 etc.. Residues 247–364: 6ZCO (X-ray 1.36 Å).73 Etc. |

| ORF9b (97 residues) plays a role in the inhibition of the host’s innate immune response by targeting the mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS). Mechanistically, it usurps the itchy E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (ITCH) to trigger the degradation of MAVS, TNF receptor associated factor 3 (TRAF3), and TRAF6. In addition, it can cause mitochondrial elongation by triggering ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of dynamin-1-like (DNM1L) protein.74 | 6Z4U (X-ray 1.95 Å) |

| ORF9c (70 residues) is located in the N-coding region and interacts with various host proteins including Sigma receptors, implying involvement in lipid remodeling and the ER stress response. It might also target NF-κB signaling.75 | None |

| ORF10 (38 residues) interacts with factors in the Cullin 2 (CUL2) RING E3 ligase complex and thus may modulate ubiquitination.75 | 7BYF (X-ray 2.5 Å)76 |

With these SARS-CoV-2 proteins, the intracellular viral life cycle of SARS-CoV-2 can be realized.23 This life cycle has six stages as shown in Figure 2. The first stage is the entry of the virus. SARS-CoV-2 enters the host cell via either endosomes or plasma membrane fusion. In both ways, the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 first attaches to the host cell-surface protein, angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Then, the cell’s protease, TMPRSS2, cuts and opens the S protein of the virus, exposing a fusion peptide in the S2 subunit of S protein.24 After fusion, an endosome forms around the virion, separating it from the rest of the host cell. The virion escapes when the pH of the endosome drops or when cathepsin, a host cysteine protease, cleaves it. The virion then releases its RNA into the cell.25 After the RNA release, polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab are translated. Notably, facilitated by viral papain-like protease (PLpro), nsp1, nsp2, nsp3, and the amino terminus of nsp4 from the pp1a and pp1ab are released. Moreover, nsp5– nsp16 are also cleaved proteolytically by the main protease.26 The next stage of the life cycle is the replication process, where nsp12 (RdRp) and nsp13 (helicase) cooperate to perform the replication of the viral genome. Stages IV and V are the translation of viral structural proteins and the virion assembly process. In these stages, structural proteins S, E, and M are translated by ribosomes and then present on the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and are transported from the ER through the Golgi apparatus for the preparation of the virion assembly. Meanwhile, multiple copies of the N protein package the genomics RNA in the cytoplasm, which interacts with another three structural proteins to direct the assembly of virions. Finally, virions will be secreted from the infected cell through exocytosis.

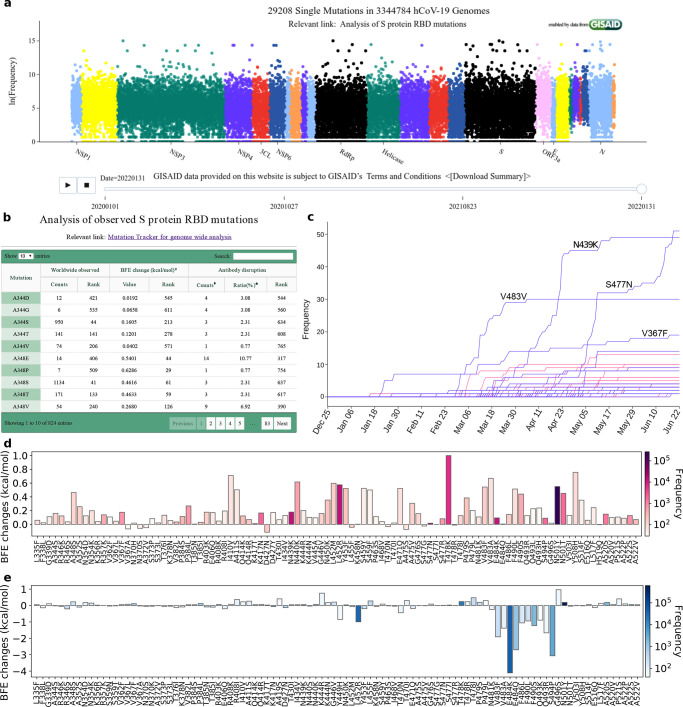

Since the initial outbreak of COVID-19, the raging pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has lasted over two years. We do have many promising vaccines, but they might have side effects and their full side effects, particularly, long-term side effects, remain unknown. To make things worse, nearly 29208 unique mutations have been recorded for SARS-CoV-2 as shown by Mutation Tracker (https://users.math.msu.edu/users/weig/SARS-CoV-2_Mutation_Tracker.html). All of these reveal the sad reality that our current understanding of life science, virology, epidemiology, and medicine is severely limited. Ultimately, the core of the challenges is the lack of molecular mechanistic understanding of many aspects, namely coronavirus RNA proofreading, virus–host cell interactions, antibody–antigen interactions, protein–protein interactions, protein–drug interactions, viral regulation of host cell functions, including autophagocytosis and apoptosis, and irregular host immune response behavior such as cytokine storm and antibody-dependent enhancement. Molecular-level experiments on SARS-CoV-2 are both expensive and time-consuming and require heavy safety measures. Moreover, disparities among reported experimental binding affinities can be more than 100-fold for the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of S protein binding to ACE2 or antibodies (see Table 1 of ref (77)). All these complicated realities make the understanding of the viral evolution and transmission mechanism one of the most challenging tasks.

On the other hand, computational tools provide alternative approaches in understanding viral evolution and transmission with higher efficiency and lower costs. The increasing computer power, the accumulation of molecular data, the availability of artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, and the development of new mathematical tools have paved the road for mechanistic understanding from molecular modeling, simulations, and predictions. RBD residues 452 and 501 were predicted to “have very high chances to mutate into significantly more infectious COVID-19 strains” in summer 202078 and were later confirmed in the prevailing SARS-CoV-2 variants Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, Theta, Epsilon, Kappa, Lambda, Mu, and Omicron. These predictions,78 achieved via the integration of deep learning, biophysics, genotyping, and advanced mathematics, are some of the most remarkable events. Additionally, 3,696 possible RBD mutations were classified into three categories with different appearance likelihoods, namely, 1149 most likely, 1912 likely, and 625 unlikely.78 The predicted “most likely” partition successfully contained all the newly observed RBD mutations, until the recent appearance of S371L from Omicron BA.1. Most remarkably, the mechanism governing SARS-CoV-2 evolution and transmission, i.e., natural selection via mutation-strengthened infectivity, was discovered in July 202078 when there were only 89 RBD mutations with the highest observed frequency of merely 50 globally.78 In April 2021, this mechanism was confirmed beyond any doubt. By using 506,768 sequences isolated from patients, the authors demonstrated that the predicted binding free energy (BFE) changes of the 100 most observed RBD mutations out of 651 existing RBD mutations are all above the BFE change of −0.28 kcal/mol, indicating evolution favors variants having higher infectivity.79 Moreover, using network-based modeling for drug repurposing, Baricitinib was found to be a potential treatment for COVID-19.80 These extraordinary results prove that computational approaches spearhead the discovery of new drugs and the mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 evolution and transmission.

Considering intensive research activities in molecular modeling, simulations, and predictions of SARS-CoV-2, it has become essentially impossible for experts and researchers to go through the literature. It is important to present a methodology-centered review to enable readers to grasp the current status of SARS-CoV-2 modeling, simulations, and predictions. In this review, the purpose is to provide a general introduction of molecular-level methodologies for SARS-CoV-2 modeling, simulations, and predictions from the aspects of biophysics, mathematical approaches, and machine learning, including deep learning, bioinformatics, and cheminformatics. A wide variety of molecular-level methodologies is described, followed by their applications to SARS-CoV-2. Comments and discussions are presented. Future perspectives are provided in the Concluding Remarks.

2. Methods and Approaches

2.1. Biophysics

The molecular modeling of viruses and their interactions with host cells involves a variety of aspects of biology, biophysics, biochemistry, virology, immunology, computer science, statistics, and mathematics. This section starts with thermodynamics and electrostatics, followed by discussions on molecular dynamics, normal-mode analysis, Monte Carlo methods, molecular docking, and binding free energy analysis, and ends with density-functional theory and quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics methods.

2.1.1. Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a foundation of biological science. The laws of thermodynamics are basic principles of biology that govern biological, chemical, and physical processes in all living organisms as well as viruses. The relations among internal energy, Helmholtz free energy, Gibbs free energy, enthalpy, entropy, temperature, volume, and pressure underpin biophysics. The Gibbs–Helmholtz equation describes the thermodynamics calculating changes in the Gibbs energy of a system as a function of temperature. It is a separable differential equation that is given as

| 1 |

where ΔG is the change in Gibbs free energy, ΔH is the enthalpy change, T is the absolute temperature, and P is the constant pressure.

In the study of the N protein of SARS-CoV, it was shown that the N protein shows its maximum conformational stability near pH 9.0. The oligomer dissociation and protein unfolding occur simultaneously.81 In the denaturation of the N protein by chemicals, the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) of unfolding at temperature (T) is calculated by the solution of the Gibbs–Helmholtz equation

| 2 |

where Tm is the transition temperature, ΔHm is the enthalpy of unfolding at Tm, and ΔCp is the heat capacity change.

2.1.2. Electrostatic Modeling

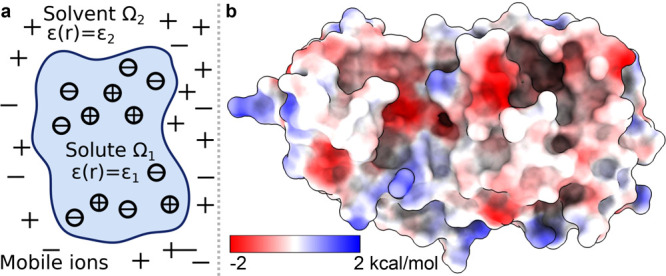

In biomolecular studies, electrostatic interactions are important due to their ubiquitous existence in solvation, molecular recognition, molecular interactions, protein–ligand binding, antibody–antigen binding, intramolecular interactions, etc. Electrostatics can be computed using explicit solvent or implicit solvent models as shown in Figure 3. However, including explicit solvent models in free energy calculation is computationally expensive due to their detailed description of solvent molecules. Using an atomic description of the solute molecule, implicit solvent models describe the solvent as a dielectric continuum.82−86 A wide variety of two-scale implicit solvent models has been developed for electrostatic analysis, including Poisson–Boltzmann (PB),83,87 generalized Born (GB),88−91 polarized continuum,92,93 and differential geometry-based models.94,95 GB models give an efficient approximation of PB models but provide only heuristic estimates for electrostatic energies, while PB methods offer more accurate methods for electrostatic analysis.86,89,95−99

Figure 3.

(a) Illustration of the PB model, in which the molecular surface separates the computational domain into the solute region Ω1 and solvent region Ω2. (b) Electrostatic potential of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro based on the PB model.

2.1.2.1. Generalized Born Model

The GB model is devised to offer a relatively simple and computationally efficient approach to calculate electrostatic solvation free energy.88−91 Under an appropriate parametrization for a given system, a GB solver can achieve accuracy as a PB solver.100 The GB approximation of electrostatic solvation free energy can be given as

| 3 |

where Ri is the effective Born radius of the ith atom, dij is the distance between atoms i and j, ϵ1 is the dielectric constant of the solute, ϵ2 is the dielectric constant of the solvent, qi is the partial charge of atom i, β = ϵ1/ϵ2, α = 0.571412, and A is the electrostatic size of the molecule. Additionally, the function fij is given as

| 4 |

The effective Born radius Ri is calculated via a boundary integral:

| 5 |

where ∂Ω1 is the molecular surface, such as the solvent-excluded surface, dS is the infinitesimal surface element vector, ri represents the position of atom i, and r shows the position of the infinitesimal surface.

2.1.2.2. Poisson–Boltzmann Model

As illustrated in Figure 3, the PB model describes a two-scale treatment of electrostatics. The interior domain Ω1 contains the solute biomolecule with fixed charges, and the exterior domain Ω2 contains the solvent and dissolved ions separated by the interface Γ. While various surface models are available, the most commonly used ones are the molecular surface or solvent excluded surface. A biomolecule in domain Ω1 consists of a set of atomic charges qk located at atomic centers rk for k = 1, ..., Nc, with Nc as the total number of charges. On the other hand, domain Ω2 contains the mobile ions, whose charge source density is approximated by the Boltzmann distribution. The linearized PB model is always applied:

| 6 |

where ϕ(r) is the electrostatic potential, ϵ(r) is a dielectric constant given by ϵ(r) = ϵ1 for r ∈ Ω1 and ϵ(r) = ϵ2 for r ∈ Ω2, and κ is the inverse Debye length representing the ionic effective length. Interface conditions are involved on ∂Ω1, which are given as

| 7 |

where ϕ1 and ϕ2 are the limit values when approaching the interface from inside or outside the solute domain and n is the outward unit normal vector on ∂Ω1. For the far-field boundary condition of the PB model, lim|r|→∞ϕ(r) = 0 is implied. Therefore, the electrostatic solvation free energy can be calculated by

| 8 |

where ϕ0(rk) is the solution of the PB equation as if there were no solvent–solute interface.

Due to their success in describing biomolecular systems, the PB and GB models have attracted wide attention in both the mathematical and biophysical communities.101−103 Meanwhile, much effort has been given to the development of accurate, efficient, reliable, and robust PB solvers. A large number of methods have been proposed in the literature, including the finite difference method (FDM),104 finite element method (FEM),105 and and boundary element method (BEM).106 The emblematic solvers in this category include Poisson–Boltzmann surface area (PBSA),107,108 Delphi,109,110 adaptive Poisson–Boltzmann solver (ABPS),97,111 matched interface and boundary-based Poisson–Boltzmann (MIBPB),98,102,112 chemistry at Harvard macromolecular mechanics (CHARMM) PBEQ-Solver,104 and treecode-accelerated boundary integral (TABI) PB solver.113,114

The PB and GB models have been applied to SARS-CoV-2 studies including protein–ligand binding and protein–protein binding energetics. The surface electrostatic potential values of S protein and Mpro were calculated for SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 with almost the same values for both viruses,115 as well as the SARS-unique domain.116 When focusing on the RBD of S protein binding to ACE2, slightly higher binding energy was revealed for SARS-CoV-2 compared to SARS-CoV because of enhanced electrostatic interactions with the negative electrostatic potential of ACE2 and positive electrostatic potential of RBD.117 For the fusion cleavage site on S protein, mutations near the cleavage site caused changes in the electrostatic distribution of the S protein surface.118 Antigens targeting SARS-CoV-2 from T cells were studied using the electrostatic surface potentials.119 By studying the surface potential of S protein, it was shown that the pH and salt concentration changed dramatically in terms of scale and sign for electrostatic interactions.120 Recently, Dung et al. proposed a theoretical model to elucidate intermolecular electrostatic interactions between a virus and a substrate. Their model treats the virus as a homogeneous particle having surface charge and the polymer fiber of the respirator as a charged plane. The electric potentials surrounding the virus and fiber are influenced by the surface charge distribution of the virus. The PB equation was used to calculate the electric potentials. Then, Derjaguin’s approximation and a linear superposition of the potential function were extended to determine the electrostatic force.121

2.1.3. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

Macromolecular structures are highly dynamic rather than static. X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) reveal that even the same molecule can adopt multiple conformations.122,123 On the other hand, conformational change plays a significant role in biomolecular functions. While NMR is limited to small biomolecules and X-ray crystallography can only provide static structures, MD simulation is an effective way to investigate biomolecular conformational changes.124,125 The Poisson–Boltzmann-based MD is also studied.126 Furthermore, thanks to high-performance computing platforms such as graphical processing units (GPUs), current MD simulations can reveal conformational changes of biomacromolecules such as proteins, DNA, and RNA in the time scale of milliseconds (ms).127

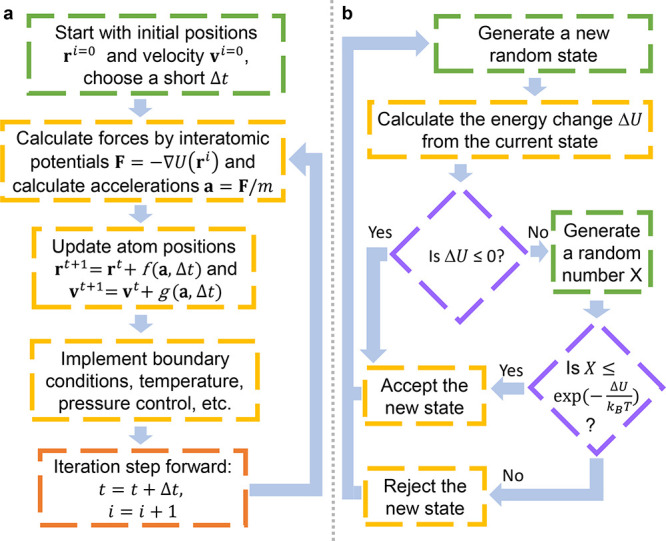

MD simulation is becoming an invaluable computational method commonly used for understanding the biomolecular structure and dynamics of atoms in macromolecules (proteins and RNA). Describing internal forces in the structure with simple mathematical functions, the motions are determined by using Newton’s second law.128 In Figure 4a, a general MD algorithm is demonstrated, where potential energy functions (force field), energy minimization, environment settings, ensembles, and solvation are included. In the prediction of atom positions and velocities, equations are given by a standard Taylor expansion. Classical interatomic potentials or quantum mechanisms are applied to calculate forces, which is followed by the correction of positions and velocities with some functions f, g of a, and Δt by energy minimization. Among all their effects on MD simulations, a collection of suitable force field functions is of fundamental importance to all other dynamics methodologies, which will be introduced first.

Figure 4.

(a) Workflow of molecular dynamics simulations. (b) Workflow of the metropolis Monte Carlo method.

Molecular Mechanics Force Field. A molecular mechanics force field is a set of functions equipped with an associated set of parameters, describing the interactions between atoms. The energy function for nonbonded interactions is associated with simple pairwise additive functions, van der Waals and electrostatic forces, of nuclear coordinates only, while for bonded groups, that is the forms of chemical bonds, bond angles, and bond dihedrals.129 For example, the functional form of a typical force field such as AMBER130 is given as

|

9 |

where kr and kθ are the force constants for the bond lengths and bond angles, respectively. Here, r and θ are a bond length and a bond angle, r0 and θ0 are the equilibrium bond length and bond angle, ω is the dihedral angle, kn is the corresponding force constant, n is the multiplicity, and phase angle γn takes values of either 0° or 180°. The nonbonded part of the potential is represented by the Lennard-Jones repulsive Aij and attractive Bij terms for Coulomb interactions between partial atomic charges (qi and qj). Here, Rij is the distance between atoms i and j. Finally, ϵ is the dielectric constant that considers the medium effect that is not explicitly represented and usually equals 1.0 in a typical solvated environment where the solvent is represented explicitly. The nonbonded terms are calculated for atom pairs that are either separated by more than three bonds or not bonded. CHARMM is another popular force field.131 Polarizable models, such as the AMOEBA force field,132 have been developed to achieve higher accuracy. To tackle systems with an excessive number of atoms, coarse-grained models are also developed. In these models, a group of atoms is represented by a “pseudo-atom”, so the number of atoms is largely reduced.133 Popular coarse-grained models are the Go̅ model,134 MARTINI force field,135 united-residue (UNRES) force field,136 etc.

Energy Minimization. Energy minimization methods are applied to efficiently optimize molecular structures. In a complex system of N atoms, the potential energy function, such as eq 9U(rN), has its global minimum. It is extremely computationally expensive to provably locate the global minimum. With an unrefined molecular structure equipped with a force field, energy minimization methods can be iteratively applied to molecular systems. The steepest descent method is one of the most popular iterative descent methods, which uses derivatives of various orders and points the path toward the nearest energy minimum. Thus, the force is calculated by

| 10 |

where r is the vector of the atomic coordinates.

Solvation. In an aqueous environment, a protein is solvated in a pure or ion-containing water environment, and explicit solvent models are computationally expensive. To avoid using water explicitly in modeling, numerous implicit solvent models have been developed.82−93 Two implicit solvent models, the Poisson–Boltzmann method and the generalized Born model, have been described in previous sections. In addition, there are explicit solvent models such as the transferable intermolecular potential with 5 points model,137 the extended simple point charge model,138 and the flexible simple point charge model water models.

Since MD simulations can provide many samplings, one can calculate the free energy change between different states from these samplings. Typical binding free energy calculation methods based on MD simulations are the molecular mechanics energies combined with Poisson–Boltzmann or generalized Born and surface area continuum solvation (MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA),108,139,140 free energy perturbation (FEP),141 thermodynamic integration,142 metadynamics,143 and steered MD simulations.144 Recently, a method that is more efficient than normal-mode analysis, called WSAS (work and social adjustment scale),145 was developed to estimate the entropic effect in the free energy calculation.

2.1.3.1. MD Simulations Revealing Conformational Changes

The most important application of MD simulations is to investigate the dynamical properties of SARS-CoV-2 proteins and the interactions between proteins and inhibitors. Moreover, Mpro and S protein are the two main targets of SARS-CoV-2 proteins to investigate, while some studies focused on PLpro. For larger systems, coarse-grained MD simulations are implemented.

Mpro. To enhance sampling of conformational space, a microsecond-scale Gaussian accelerated MD simulation to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro was performed,146 where the simulations identified cryptic pockets within Mpro, including some regions far from the active site. The 2 μs MD trajectories of the apo form of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro indicated that the long loops, which connect domains II and III and provide access to the binding site and the catalytic dyad, carried out large conformational changes.147 Additionally, MD simulations were applied to compare the dynamical properties of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and SARS-CoV Mpro, which suggests that the SARS-CoV Mpro has a larger binding cavity and more flexible loops148 and reveals the key interactions and pharmacophore models between the Mpro and its inhibitors.149 Recently, Sanjeev et al. used MD simulations to study the impact of a crowded environment on drug–Mpro complexes, suggesting that crowding enhances the difference in the dynamics of apo- vs drug-bound complexes.150 Lamichhane et al. not only ran MM/PBSA calculation but also used the analysis by dihedral angle distribution and radial distribution functions to confirm the strong interactions between inhibitor N3 and Mpro.151

S Protein. MD simulations were performed to study the binding of S protein and ACE2,152−156 which were the most important studies of S protein. Notably, a 100 ns MD simulation of the complexes of human ACE2 and S protein from SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV showed that the SARS-CoV-2 complex was more stable.156 Grishin et al.’s MD simulation suggests disulfide bonds play a critical role in S protein–ACE2 binding and the flexibility of the surface loops increases when the four disulfide bonds of the domain are reduced.157 As for temperature, MD simulations at different temperatures suggested S protein had a stronger binding at a low temperature.158 Abdalla et al. investigated the effects of mutations on S protein stability and solubility through MD simulations in a 100 ns period.159 Inhibitor and antibody binding to ACE2 was studied by MD simulations.160−162 One of the studies suggested that the SARS-CoV-2 S protein can interact with a nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) inhibitor.161 Moreover, ACE2-Fc fusion proteins with the SARS-CoV-2 S protein RBD were simulated by a glycosylated molecular model.163 In a steered MD model, a semiopen intermediate state was observed of the transition between closed and open states of S protein.164 Further study was about the motion of glycans in S protein by a 1 μs MD simulation, uncovering the detail of the S protein glycan shield.165 A recent interesting study by Lupala et al. performed an MD simulation of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein with ACE2 from different species. Their findings suggest that the ACE2 proteins of bovine, cat, and panda form strong binding interactions with RBD, while in the cases of rat, least horseshoe bat, horse, pig, mouse, and civet, the ACE2 proteins interact weakly with RBD.166

PLpro and Other Proteins. MD simulations were also used to investigate the conformational changes of other SARS-CoV-2 proteins. For PLpro, researchers performed pH replica-exchange CpHMD (constant pH molecular dynamics) simulations to estimate the pKa values of Asp/Glu/His/Cys/Lys side chains and assessed possible proton-coupled dynamics in SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and MERS-CoV PLpros.167 They also suggested a possible conformational-selection mechanism by which inhibitors bind to the PLpro. Supervised MD simulations were employed to investigate the unbinding pathways of GRL0617 and its derivates from PLpro.168 Sun et al. applied MD simulations and topological and electrostatic analyses to study the effects of palmitoylation on an E protein pentamer. Their results indicated that the structure of the palmitoylated E protein pentamer was more stable while the loss of palmitoylation caused the pore radius reduced and even collapsed, which might help the drug design for the treatment of COVID-19.169

2.1.3.2. Coarse-Grained MD Simulations

Modeling the whole SARS-CoV-2 in a fine grid is extremely time-consuming, if not impossible. To study the behavior of SARS-CoV-2, a coarse-grained model based on the data from a combination of cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography was employed in a complete virion model.170 More importantly, the binding between S protein and ACE2 or antibodies can be studied by coarse-grained MD simulations.171 Bai et al. also used their own coarse-grained models to predict mutation-induced binding affinity changes between Mpro and human ACE2.172 With replica-exchange umbrella sampling MD simulations, a comparison of the binding of SARS-CoV-2 S protein and SARS-CoV S protein to human ACE2 revealed that the SARS-CoV-2 binding to human ACE2 is stronger than that of SARS-CoV.173 The infectivity induced by mutations on S protein is another problem after studying the binding of ACE2 and S protein, where coarse-grained MD simulations were employed to reveal the dynamics impact of mutations T307I and D614G174 or SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.1.7 and P1.175 The impacts of mutations to antibodies CR3022 and CB6 were also predicted.176 Lastly, glycan shield effects on drug binding are also studied via multiscale coarse-grained MD simulations.177

2.1.4. Normal-Mode Analysis

Compared to molecular dynamics simulations, normal-mode analysis (NMA) has its advantages in dealing with the flexible motions accessible to a protein system at a steady-state position. Based on the equation of motion, normal-mode analysis studies molecular structure conformation by a restoring force acting on a vibrational system perturbed slightly at its equilibrium. Achieving its efficiency for large proteins and protein complexes, NMA is widely applied in large molecules and homology modeling studies, as well as evolutionary and stability analysis of proteins. Additionally, for computational efficiency, the elastic network model (ENM), Gaussian network model (GNM), and anisotropic network model (ANM) are developed and applied to similar problems.

The derivation of normal-mode analysis starts from the equations

of motion. It is formulated from Lagrange’s second kind equation,

with the Lagrangian  , where Ek and U are the kinetic and potential energies of the molecular

system, respectively.178−180 The potential energy U is

calculated by eq 9. The

system is defined to be in a potential minimum of equilibrium where

the generalized forces acting on it are eliminated. In this Lagrangian

mechanical system

, where Ek and U are the kinetic and potential energies of the molecular

system, respectively.178−180 The potential energy U is

calculated by eq 9. The

system is defined to be in a potential minimum of equilibrium where

the generalized forces acting on it are eliminated. In this Lagrangian

mechanical system  , M is a configuration

space and Lagrangian

, M is a configuration

space and Lagrangian  , where r ∈ M, v is the velocity vector at position r, and t is the time. They thus define the

generalized coordinates r̂ and apply the Taylor

expansion to the potential energy. The equation can be formulated

as

, where r ∈ M, v is the velocity vector at position r, and t is the time. They thus define the

generalized coordinates r̂ and apply the Taylor

expansion to the potential energy. The equation can be formulated

as

| 11 |

where ri is the ith component of the instantaneous configuration and ηi = ri – r̂i. Here, the Einstein summation convention is used. Note that eq 11 studies the mechanism system at equilibrium, and therefore, the first term can be set to zero in terms of the minimum value of the potential with the second term zero at any minimum. We can rewrite the potential energy to be

| 12 |

where Uij is the Hessian matrix. As for the kinetic energy Ek, it is given as

| 13 |

where M is a diagonal matrix of the mass of each particle. By applying Lagrange’s equation, the equations of motion can be given as

| 14 |

with one oscillatory solution ηi = aij cos(ωjt + δj), where aij is the amplitude of oscillations, ωj is the frequency, and δj is a factor. Here, it is easy to obtain the eigenvalue problem UA = λA, where A is an eigenvector of the aforementioned Hessian matrix and λ is an eigenvalue which is the square of frequency ωk. The eigenvector is also referred to as a normal-mode vector for a particle’s movement in terms of direction and distance with a certain frequency.

2.1.4.1. Elastic Network Model

Though NMA has computational efficiency compared to MD simulation, its computation is still expensive, especially for proteins containing tens of thousands of atoms. Additionally, one assumption of NMA requires energy minimization to ensure the starting conformation is at equilibrium. This minimization process might distort the structure, leading to a different structure from the experimental one. Therefore, a variety of coarse-grained approximate algorithms has been developed to overcome these limitations.181,182 Among them, the elastic network model (ENM) is widely applied.

The ENM simplifies the force fields used in standard NMA by a harmonic potential183

| 15 |

where dij is the distance between the ith and jth atoms, dij0 stands for the distance at the initial structure, and k mimics the spring constant in Hooke’s law. RC is a cutoff and usually is set between 7.0–8.0 Å, according to the distances between nonbonded atoms.184 More studies consider the Cα atoms only, for their sufficiency in backbone motion investigation. Many generalizations implemented the ENM’s idea to reformulate potential functions.

2.1.4.2. Gaussian Network Model and Its Generalization

One of the generalizations is the Gaussian network model (GNM),185 which is considered the most efficient one, using the discrete Laplacian matrix instead of the Hessian matrix. The expected residue fluctuations constructed by the GNM are in great agreement with the Debye–Waller factor (a.k.a. B factor). More precisely, the B factor of the ith α carbon atom (Cα) in an N-particle coarse-grained representation of a biomolecule can be obtained by the generalized GNM (gGNM) method186,187

| 16 |

where agGNM is a fitting parameter and (Γ–1)ii is the ith diagonal element of the matrix inverse Γ–1. Here, Γ is the generalized Kirchhoff matrix

|

17 |

where ri are positions of Cα, the kernel functions Φ can be generalized exponential functions or generalized Lorentz functions, and ηj are the characteristic distances.186,187 If the kernel functions are set to be {0, 1} with distance ∥ri – rj∥ outside or inside a fixed cutoff distance, then the Kirchhoff matrix becomes the Laplacian matrix and the GNM is recovered.

2.1.4.3. Anisotropic Network Model and Its Generalization

Another popular method is the anisotropic network model (ANM),183,188 which gives extra information about the directionality of the fluctuations. The B factor of ith Cα in an N-particle coarse-grained biomolecule can be displayed by the generalized ANM method186,187

| 18 |

where agANM is a fitting parameter and (H–1)ii is the ith diagonal element of the matrix inversion of Hessian matrices.

2.1.4.4. Applications to SARS-CoV-2

The SARS-CoV-2 Mpro is used as one of the most popular target proteins for drug repurposing in applications. According to the stability analysis by NMA, the inhibitor repurposing of SARS for COVID-19 may be challenging.148 With further investigations of Mpro by the ENM, possible noncompetitive inhibiting binding sites were suggested189 (see Figure 5). Moreover, the SARS-COV-2 S protein is another target for inhibitor repurposing. In the comparison of the S proteins of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV, the ANM was employed to study the dynamic modes of the S proteins, revealing that the receptor binding motif had high vertically upward motion.190 In ref (191) ENM-based analysis tools were applied for the allosteric modulation region of the S protein with ACE2, and it was indicated that hepcidin induces an inhibitory effect on the binding affinity of the S protein and ACE2. The stability and flexibility of mutations can be examined by normal-mode analysis, especially the mutations on RBD or high-frequency mutation D614G of the S protein175,192,193 and on other SARS-CoV-2 proteins.193,194

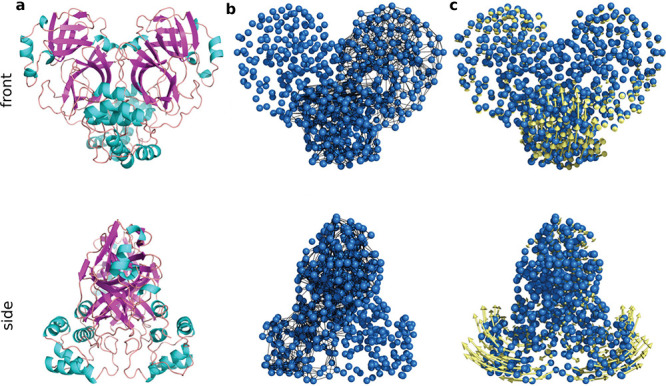

Figure 5.

Illustration of the ENM on SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.189 Reproduced with permission from ref (189). Copyright 2021 Dubanevics and McLeish under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. (a) Mpro secondary structure. (b) Elastic model of Mpro. Cα atoms are in blue, and node-connecting springs are in black. (c) The first real vibrational mode eigenvectors are in yellow.

2.1.5. Monte Carlo Methods

Monte Carlo (MC) methods rely on repeated random sampling to obtain optimized numerical results. In principle, Monte Carlo methods can be used to solve any problems having a probabilistic distribution.195 When the probability distribution of the variable is parametrized, researchers often use a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampler,196 whose central idea is to design a judicious Markov chain model with a prescribed stationary probability distribution. By the ergodic theorem, the stationary distribution is approximated by the empirical measures of the random states of the MCMC sampler. Recently, a machine-learning-based implicit solvent Monte Carlo method was developed to predict the molecular structure.197

Importantly, metropolis Monte Carlo methods198 are popular in molecular modeling. As shown in Figure 4b, the essential idea is that, if the energy of a trial conformation is lower than or equal to the current energy, it will always be accepted. If the energy of a trial conformation is higher than the current energy, then it will be accepted with a probability determined by the Boltzmann (energy) distribution,

|

19 |

where j is the current conformation, i is the new conformation,  is the probability to accept the

new conformation,

ΔUij is the energy

difference between i and j, kB is the Boltzmann constant,

and T is temperature. Therefore, the evolution of

molecular conformations can be simulated. There are several aspects

of MC applications regarding SARS-CoV-2. An MC simulation of ionizing

radiation damage to the SARS-CoV-2 found that γ-rays produced

significant S protein damage but much less membrane damage.199 Thus, the γ-rays were proposed as a new

effective tool to develop inactivated vaccines. A metropolis MC sampling

process was applied to simulate a pharmacokinetic model of the human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) drug darunavir against SARS-CoV-2.200 MC modeling was also implemented in the analysis

of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro201 and N protein.202 Studies focusing on Mpro and S protein are

introduced as follows.

is the probability to accept the

new conformation,

ΔUij is the energy

difference between i and j, kB is the Boltzmann constant,

and T is temperature. Therefore, the evolution of

molecular conformations can be simulated. There are several aspects

of MC applications regarding SARS-CoV-2. An MC simulation of ionizing

radiation damage to the SARS-CoV-2 found that γ-rays produced

significant S protein damage but much less membrane damage.199 Thus, the γ-rays were proposed as a new

effective tool to develop inactivated vaccines. A metropolis MC sampling

process was applied to simulate a pharmacokinetic model of the human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) drug darunavir against SARS-CoV-2.200 MC modeling was also implemented in the analysis

of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro201 and N protein.202 Studies focusing on Mpro and S protein are

introduced as follows.

Mpro. Liang et al. used protein energy landscape exploration (PELE) Monte Carlo simulations for a blind binding site search and the best binding poses for these binding sites.203 Their simulations found that compounds such as cyanidin-3-O-glucoside and hypericin have the strongest interactions with the active sites. Their PELE also identified additional binding sites for hypericin with comparable interaction energies.203 A coarse-grained Monte Carlo simulation was integrated with other computational methods to reveal the relationship between the rigidity and enzymatic function for Mpro,204 while the Mpro inhibitory activity of aromatic disulfide compounds was studied by the weight search of MC simulations for the QSAR (quantitative structure–activity relationship) model.205

S Protein. Two major directions of the S protein are mutation studies,206,207 namely G614D and N501Y, and binding problems about ACE2,117,208 antibodies,171 and peptide-based inhibitors.171,208,209 To estimate the density of states of the S protein system, the Wang and Landau Monte Carlo method was applied to study the human ACE2 complexes with SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV S protein RBDs,208 while the difference between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV was studied.210 In the study of the heterogeneity of glycosylation on the S protein trimer make up, the MC approach was applied to calculate the glycan mass distribution because of the enormous number of possible glycoforms.211

2.1.6. Molecular Docking

As shown in Figure 6a, molecular docking, which can predict the binding conformation of a ligand on its binding site, is one of the most popular methods in the structure-based drug design.213,214 A typical docking program includes two key components: a scoring function to calculate the binding energies of different conformations and a search algorithm to sample the conformational degrees of freedom and locate the global energy minimum from all the sampled conformations.215 Traditional scoring functions are derived from physical models such as molecular mechanism force fields. In recent years, more and more machine-learning-based scoring functions have been developed, which outperform traditional scoring functions in many cases.216−219 In addition to regular docking, ensemble docking220 considers the dynamics of the receptor and docks a ligand to various receptor conformations (often yielded from molecular dynamics simulation). Molecular docking is well-established in early stage drug discovery. As a result, during the pandemic, to seek drug leads, docking studies have been performed targeting a variety of SARS-CoV-2 proteins.

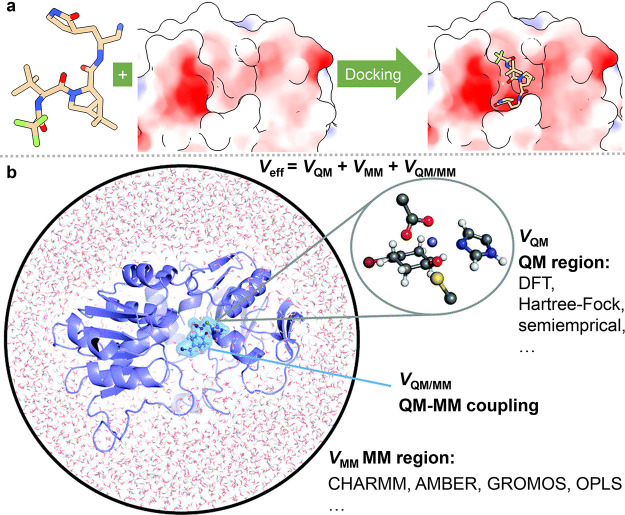

Figure 6.

(a) Procedure of molecular docking simulation. (b) Procedure of quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) calculation.212 Reproduced with permission from ref (212). Copyright 2017 Royal Society of Chemistry.

Mpro. One important source for searching for SARS-CoV-2 treatments is existing drugs. In a quite extensive drug repurposing work, 7173 purchasable drugs, including 4574 unique compounds and stereoisomers, were docked and their binding affinities to Mpro were predicted.221 As a result, diosmin, hesperidin, and MK-3207, with a docking score of −10.1 kcal/mol, were suggested as the most potent inhibitors. A collection of 8625 drugs or compounds from FDA, drugbank, and Zinc data sets were docked to Mpro,222 and seven drugs such as metyrapone could maintain key interactions within the active site of the enzyme suggested by the crystallographic complex structures, revealing their repurposing potential. Additionally, Sencanski et al.223 and Gurung et al.224 both screened about 1400 FDA-approved drugs with docking, predicting that dihydroergotamine has a promising affinity. Docking was used to evaluate the potency of around 100 approved protease inhibitors, and it suggested that faldaprevir has the strongest binding affinity.225 In a screening of roughly 7100 molecules, several natural molecules such as δ-viniferin, myricitrin, taiwanhomoflavone A, lactucopicrin 15-oxalate, nympholide A, afzelin, biorobin, hesperidin, and phyllaemblicin B were identified.226 Many other studies222,227−236 have also docked and repurposed existing drugs against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

Natural products are popular inhibition candidates. In a study of 1000 active phytochemicals from Indian medicinal plants by molecular docking, rhein and aswagandhanolide were predicted to have binding affinities over −8.0 kcal/mol.237 In a study of 100 natural and nature-inspired products from an in-house library to Mpro, leopolic acid A is predicted to have the highest affinity of −12.22 kcal/mol.238 From mushrooms and other herbal or natural compounds, colossolactone VIII239 and eugenin240 were identified as having a high affinity to Mpro. It is predicted that from Amphilophium paniculatum leaves, luteolin 7-O-b-glucopyranoside (cynaroside) has the highest affinity of −9.54 kcal/mol.241 All of them also predicted ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) properties of their compounds. Moreover, a variety of natural products were also investigated by docking-based virtual screening, including syzygium aromaticum, cassia acutifoliaaloe vera, rhus spp., moroccan medicinal plants, fungal metabolite, millet, tannins, neem leaves, nigella sativa, etc.242−256

Some researchers focus on peptides and small compounds from other sources. Tsuji et al.257 screened compounds from the ChEMBL (chemical database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties) database258 to Mpro via docking, suggesting that the compound CHEMBL1559003 with a binding affinity of −10.6 kcal/mol is the most potent. In a set of 13535 Mpro compounds, the consensus of the docking scores from the five different pieces of docking software evaluates the potency.259 Udrea et al.260 predicted the binding affinities of 15 phenothiazines, where the compound sulphoridazine (SPZ) was reported as the most effective. Ghaleb et al.261 also studied some pyridine N-oxide compounds, indicating the most potent one with a predicted pIC50 (the negative log of the IC50 when converted to molar) value of 5.294. More similar works can be found in the literature.262−270

S Protein. Many researchers focus on the binding interactions of S protein and the host ACE2 or antibodies. A docking calculation was applied to construct the complexes of SARS-CoV-2 S protein and SARS-CoV S protein binding to ACE2,271 which suggested that there were more residue interactions between SARS-CoV-2 S protein and ACE2 than that of SARS-CoV S protein. It also leads to a higher binding affinity and is consistent with a recent experiment.272 In a study of ACE2s from cats, tigers, hamsters, dogs, and ferrets via homology modeling and docking, it was shown that the cat and tiger ACE2s could potentially interact with S protein RBD and share the same virus-binding interface with ACE2, whereas the dog, ferret, and hamster ACE2 were not predicted to establish stable interactions with S protein RBD.273 A docking simulation suggested ACE2 polymorphisms from different human races could change the ACE2 affinity to SARS-CoV-2 S protein.274 For other receptors, S protein cannot strongly bind to the human dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 (DPP4) receptor,275 while S protein RBD was able to bind to many amyloidogenic proteins, initiating aggregation of these proteins and leading to neurodegeneration in the brain.276 Interestingly, a recent docking study by Kazybay et al. suggested that the Omicron variant EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) was one of the potential binary partners of the S RBD that binds almost with equal affinity as the RBD–hACE2 complex.277 Hanai et al. used docking studies to suggest that Omicron’s binding to ACE2 was stronger than Delta’s and Alpha’s.278

More investigations were carried out to repurpose existing drugs to S protein or find inhibitors for S protein. In a study of screening FDA-approved drugs, iron oxide nanoparticles were suggested for COVID-19 treatment.279 Existing drugs, such as amentoflavone, ledipasvir, tenofovir, levodopa, lopinavir, and ubrogepant, against S protein were investigated.280−283 For natural products inhibiting S protein, studies focusing on indigenous food additives, herbal constituents, antioxidants, traditional medicinal plants, tea, and others284−289 suggested potent inhibitors such as phycocyanobilin, phycoerythrobilin, phycourobilin, folic acid, hinokiflavone, and phytochemicals. Lastly, some other compounds are repurposed to inhibit the S protein. Mohebbi et al.290 screened more than 1 billion compounds from the databases ZINC Pharmer and Pharmit in silicon. The docking of dermaseptin-based antiviral peptides to the S protein was studied.291 Some drugs were identified with high binding potential against the ACE2–S protein interaction pocket, such as Atazanavir, Grazoprevir, Saquinavir, Simeprevir, Telaprevir, and Tipranavir.292

RdRp. RdRp is another target for docking inhibitors from existing drugs or traditional medicines. In a data set of 7922 approved or experimental drugs, Nacartocin has the highest binding affinity.293 Beg et al.294 screened 70 anti-HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) or anti-HCV (hepatitis C virus) drugs, reporting that the drug paritaprevir has the highest binding affinity. Aftab et al.295 studied 10 antiviral drugs and revealed that Remdesivir’s docking score was the highest, but Padhi et al.194 showed that the docking affinity of remdesivir is relatively low. Meanwhile, many researchers screened potential drugs in traditional medicinal compounds. Theaflavin was reported to have the highest binding affinity among a data set of 83 traditional Chinese medicinal compounds plus their similar structures from the ZINC15 database.296 Pandeya et al.297 also investigated some biologically active alkaloids of argemone mexicana. Other RdRp drug repurposing works can be found in the literature.298−301

Other Targets. Some docking studies selected the SARS-CoV-2 PLpro as their targets. Choudhury et al.302 docked 27 existing drugs to PLpro and predicted stallimycin to be the best inhibitor. Similarly, Li et al.303 repurposed 21 drugs to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 PLpro and reported neobavaisoflavone as the most potent candidate. Mohideen et al.304 revealed that the binding affinity of the natural product thymoquinone to the E protein is −9.01 kcal/mol. Borgio et al.305 screened 23 FDA-approved drugs to target the helicase of SARS-CoV-2 and reported vapreotide having a binding affinity of −11.58 kcal/mol as the most potent candidate. Mahmud et al.306 showed that drugs such as valrubicin, aprepitant, and saquinair have excellent docking scores to SARS-CoV-2 nsp15. Khan et al.307 used docking to study the interaction between N protein and nsp3.

Multiple Targets. Many researchers studied the whole SARS-CoV-2 or multiple SARS-CoV-2 proteins for more potent inhibitors. In an analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-COV-2 involving homology modeling and molecular docking, a data set of 78 commonly used antiviral drugs for SARS-CoV-2 proteins was selected.22 By using molecular docking on 2631 US FDA-approved small molecules, five drugs (avapritinib, bictegravir, ziprasidone, capmatinib, and pexidartinib) were suggested as candidates against SARS-CoV-2 proteins. In a study of docking 11 antiviral drugs to Mpro, S protein, PLpro, nsp10, nsp16, and nsp9, ritonavir, lopinavir, and remdesivir were selected as drug candidates against SARS-CoV-2.308 Other approved structural analogs, such as telbivudine, tenofovir, amprenavir, and fosamprenavir, were identified as potent drugs for SARS-CoV-2 by molecular docking.309 On a data set consisting of 2285 FDA-approved drugs and 1478 Taiwan National Health Insurance-approved drugs (https://covirus.cc/drugs/), a virtual screening targeting S protein, Mpro, PLpro, RdRp, N protein, hACE2, and human cellular TMPRSS2 were conducted.310 Chandel et al.311 repurposed about 2000 FDA-approved compounds targeting S protein and nsp9, reporting that Tegobuvir was the most potent candidate to S protein and Conivaptan was the most potent candidate to nsp9. Many works considered two different protein targets. Elmezayen et al.312 virtually screened 4500 approved or experimental drugs against Mpro and human TMPRSS2, finding out that ZINC000103558522 has the highest binding affinity to Mpro and ZINC000012481889 has the highest binding affinity to the TMPRSS2. Via the DockThor-VS platform, Guedes et al.313 predicted the binding affinities of over 40 approved drugs to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, S protein, PLpro, RdRp, N protein, and nsp15. The binding affinities of the compounds protoporphyrin IX, verteporfin, and chlorin e6 to Mpro, S protein, ORF3a, ORF9b, and ORF7a were studied.314 In addition, some components such as essential oil components,315 organosulfur compounds,316 and methisazones317 were investigated. It was exhibited that rutin has some inhibitory effect on SARS-CoV-2 proteins.318 Phytochemicals from the traditional medicines were also investigated by docking, such as those from traditional Himalayan medicinal plants,319 Indian traditional medicinal plants,320−333 Chinese traditional medicines,334 and Brazilian herbal medicines.335

Targeting Mpro, S protein, and RdRp, Parvez et al.298 studied some plant metabolites. Maurya et al.336 investigated yashtimadhu (glycyrrhiza glabra) active phytochemicals, and Alexpandi et al.337 simulated quinoline-based inhibitors. Flavonoids might inhibit Mpro, S protein and RdRp as well.338,339 Against the S protein and nsp15S, Sinha et al.340 screened 23 saikosaponins and reported that saikosaponin V was potent to both targets. Montelukast was predicted to be potent to both Mpro and RdRp341 as well as Camptotecin.287 Srikanth et al.342 and Agrawal et al.343 virtually explored the potential of andrographolide as well as other antivirals, antibiotics, antiparasitics, flavonoids, and vitamins in inhibiting S protein and RdRp. Another molecular docking of compounds such as coumarins, porphyrins, propolis, or existing drugs can be found in refs (344−349).

2.1.7. Binding Free Energy Calculations

In the study of SARS-CoV-2, protein–protein and protein–ligand interaction processes are essential. Some of these processes are investigated through molecular biophysics, such as the binding free energies for protein–ligand and protein–protein complexes. To estimate the binding free energies, classical methods such as FEP and thermodynamic integration (TI) methods are computationally expensive, while many other methods are developed considering efficiency, such as the molecular mechanics/Poisson–Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) method,350,351 the molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) method,351,352 the linear interaction energy (LIE) method,353 the chemical Monte Carlo/molecular dynamics (CMC/MD) method,354,355 the pictorial representation of free energy components (PRO-FEC) method,356 etc. Among these methods, MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA are widely applied for their accuracy and efficiency.

2.1.7.1. MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA

In the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA approaches,108 the binding free energy ΔΔGbind for binding between a ligand and a protein receptor in the form of a protein–ligand complex can be calculated by

| 20 |

where ΔGcomplex is the total free energy of the complex and ΔGprotein and ΔGligand are the total free energies of the protein and ligand in solvent, respectively (see Figure 7). The free energy for each individual body can be calculated by

| 21 |

where G* are referring to the total free energies of the complex, protein, and ligand, ⟨VMM⟩ is the average molecular mechanical potential energy in a vacuum of eq 9, and TS is the entropic contribution to the free energy with the temperature T and the entropy S in a vacuum. ΔGsol is the free energy of solvation

| 22 |

The polar solvation energy ΔGsolpolar is calculated by solving the PB equation or the GB equation, and the nonpolar solvation energy ΔGsol is evaluated by cavity formation in the solvent and van der Waals interactions between solvent and solute. More details about the PB and GB models can be found in section 2.1.2.

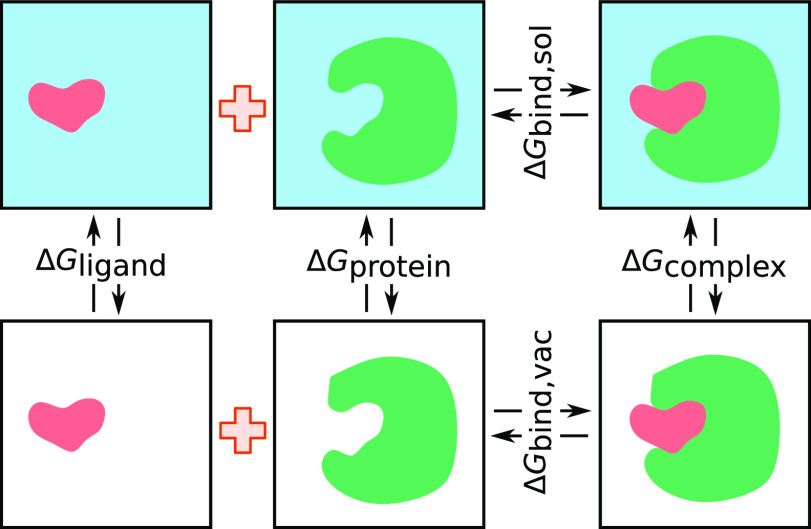

Figure 7.

Illustration of the thermodynamic cycle of MM/PB(GB)SA calculations. ΔGcomplex is the total free energy of the complex, and ΔGprotein and ΔGligand are the total free energies of the protein and ligand in solvent, respectively. ΔGbind,sol and ΔGbind,vac are the total free energies in solvent and in vacuum, respectively.

2.1.7.2. MD-Based Methods

Besides MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA, other binding free energy calculation methods such as FEP, metadynamics, and steered MD simulations were also applied to evaluate the binding affinities of inhibitors to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro or S protein.

FEP. MD simulations and FEP calculations were considered to uncover the mechanism of the stronger binding of SARS-CoV-2 S protein to ACE2 by Wang et al.357 They compared the hydrogen-bonding and hydrophobic interaction networks of SARS-CoV-2 S protein and SARS-CoV S protein to ACE2 and calculated the free energy contribution of each residue mutation from SARS-CoV to SARS-CoV-2. FEP calculations indicated that the N501Y mutation on the SARS-CoV-2 S protein enhanced the binding to host ACE2.358 FEP calculations indicated the E484Q/L452R mutations significantly reduce the binding affinity between the RBD of the Kappa variant and the antibody LY-CoV555.359 Ngo et al.360 first docked about 4600 drugs or compounds to Mpro and then used steered MD simulations to rescore the top 35 compounds. They reevaluated the top three compounds using FEP free energy calculations. Zhang et al.361 docked remdesivir and ATP to RdRp and used FEP to calculate the binding free energy, indicating that the binding of remdesivir was about 100 times stronger than that of ATP and it can inhibit the ATP polymerization process. FEP calculations were performed by Hassan et al.,362 Allam et al.,363 and Alhadrami et al.364

Thermodynamic integration (TI). In a recent work,365 the authors used MD simulations to explore the structural coordination and dynamics associated with the SARS-CoV-2 nsp13 apo enzyme, as well as its complexes with natural ligands. The binding free energy and the corresponding mechanism of action by TI calculations were presented for three small molecules that are revealed as efficient inhibitors of the previous SARS-CoV nsp13 enzyme.

Metadynamics. Researchers docked 16 artificial-intelligence generated compounds by Bung366 to Mpro and then ran metadynamics to calculate their binding affinity and predicted some potential inhibitors.367 Metadymics simulations were used to predict the affinities of three neem tree extracts to S protein.368

Steered MD Simulations. Steered MD simulations were used to dock drugs and marine compounds to Mpro, to infer the top inhibitors by Tam et al.369,370 MM/PBSA and steered MD simulations suggest that the adsorption of the ACE2 on specific silane monolayers could increase its affinity toward the S protein RBD, which could help develop biosensing tools efficient toward any variants of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein.371

Semiempirical Free Energy Force Field Methods. A semiempirical free energy force field372 was also adopted to calculate the affinities of 16 drugs to S protein.373

In most applications, MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA calculations are used to select the trajectories or rank the drugs. The applications of MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA on SARS-CoV-2 proteins are discussed below.

Mpro. Docking, MD simulations, and MM/PBSA binding free energy calculations were applied to investigate around 10000 drugs or experimental drugs from the DrugBank.374 These compounds were first screened by docking, and then MD-based MM/PBSA binding free energy calculations were performed on the top 36 compounds. The reported binding data were the consensus of docking and MM/PBSA prediction, and leuprolide was the top one. Very similar work also screened thousands of compounds from the DrugBank by docking and MM/GBSA MD simulations.375 Gahlawat376 implemented an MM/GBSA procedure on 2454 FDA-approved or experimental drugs, 138 natural products, and 144 other inhibitors to predict the MM/GBSA binding free energy of the top ones screened by docking. MM/PB(GB)SA was also implemented for trajectory selection.377,378 In addition, Sharma et al.379 also implemented MM/PBSA to screen 2100 drugs as well as 400 other compounds and reported that cobicistat had the highest binding affinity of −11.42 kcal/mol. Cobicistat, flavin adenine dinucleotide, and simeprevir were suggested through drug ranking according to binding energy by MM/PB(GB)SA calculations. Other assessments based on docking and MM/PB(GB)SA calculations focused on specific drugs or compounds such as ravidasvir, lopinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, teicoplanin, GC-376, calpain XII, calpain II, anti-HIV drugs, doxorubicin, chloroquine, quinoline, hydroxychloroquine, noscapine, echinocandins, coumarins, and their derivatives.380−417

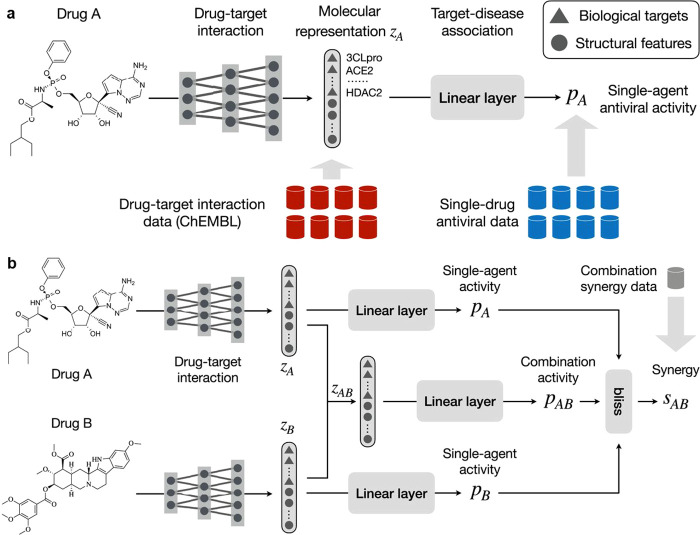

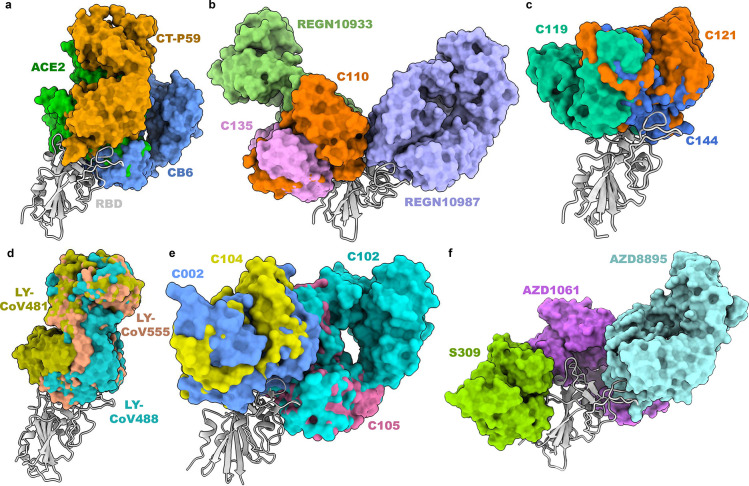

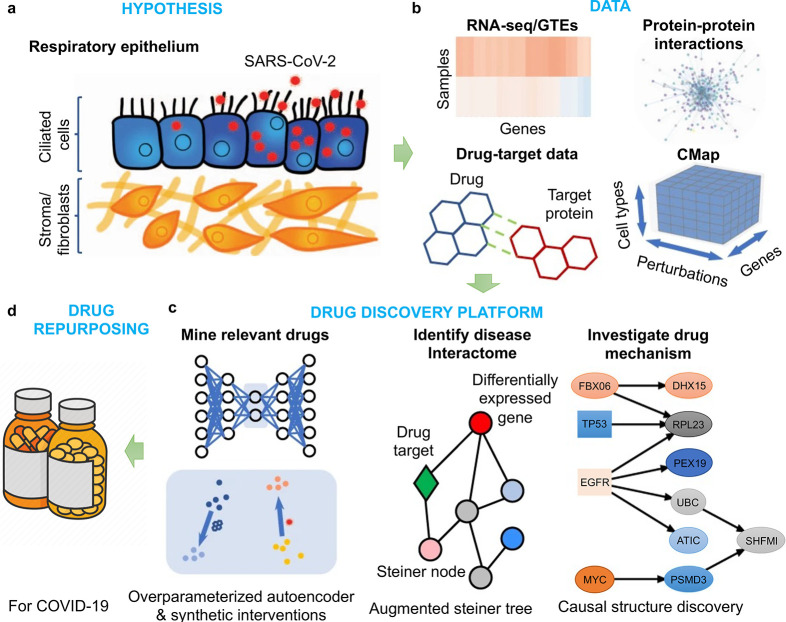

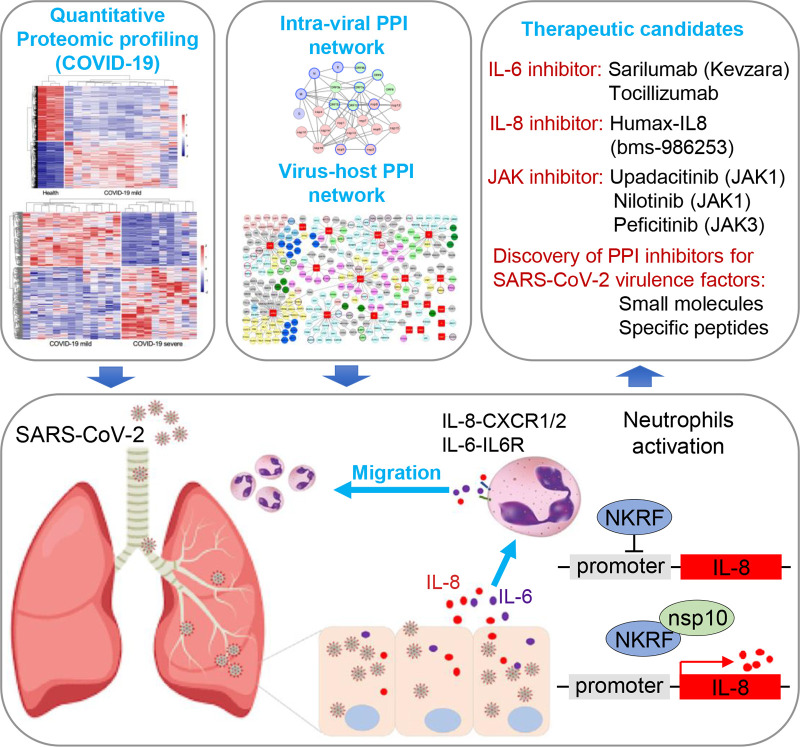

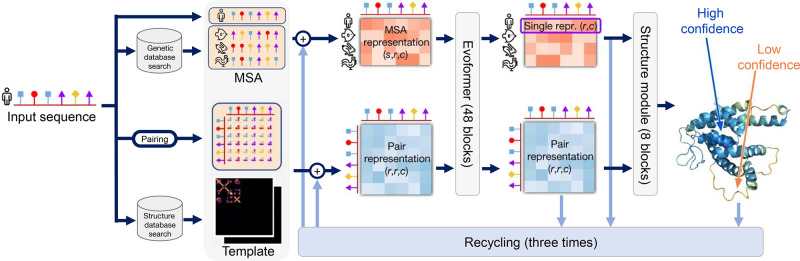

MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods were also applied to predict the potency of natural products to Mpro. Ibrahim et al.418 virtually screened the MolPort database containing 113,756 natural or natural-like products (https://www.molport.com) by docking. The top 5,000 compounds were selected and subjected to MD simulations combined with MM/GBSA binding affinity calculations, and the compound MolPort-004-849-765 was predicted to have the highest binding free energy. Kapusta et al.419 also performed docking on 13,496 natural or natural-like products from MolPort, and the top 15 were chosen for rescoring by MM/GBSA calculations. The authors reported MolPort-039–338–330 as the most potent one. Prajapati et al.420 investigated 1830 secondary metabolites of fungal via docking, and additional MM/GBSA calculations were performed on the top from compounds. Mahmud et al.421 screened 1480 natural plant products from the literature initially by docking scores, and then the best 10% were rescored by MM/GBSA. Other natural product sources screened by docking and MM/PB(GB)SA against Mpro were flavonoid-based phytochemical constituents of calendula officinalis, phytochemicals in Indian ginseng, food compounds, marine natural polyketides, malaria-box compounds, cressa cretica compounds, strychnos nux-vomica products, ayurvedic compounds, moringa oleifera compounds, withania sp. products, stilbenolignans from plants, acridinedione analogs, alkaloids from justicia adhatoda, tea plant products, neem compounds, turmeric compounds, echinacea angustifolia products, Withania somnifera (ashwagandha) products, cyperus rotundus Linn products, salvia plebeia products, lichen compounds, curcuma longa products, and polyphenols from broussonetia papyrifera.422−458