Abstract

To understand the potential and limitations of the different available surgical techniques used to treat large, long-bone diaphyseal defects by focusing on union, complication, re-intervention, and failure rates, summarizing the pros and cons of each technique. A literature search was performed on PubMed, Web of Science, and Cochrane databases up to March 16th, 2022; Inclusion criteria were clinical studies written in English, of any level of evidence, with more than five patients, describing the treatment of diaphyseal bone defects. The primary outcome was the analysis of results in terms of primary union, complication, reintervention, and failure rate of the four major groups of techniques: bone allograft and autograft, bone transport, vascularized and non-vascularized fibular graft, and endoprosthesis. The statistical analysis was carried out according to Neyeloff et al., and the Mantel–Haenszel method was used to provide pooled rates across the studies. The influence of the various techniques on union rates, complication rates, and reintervention rates was assessed by a z test on the pooled rates with their corresponding 95% CIs. Assessment of risk of bias and quality of evidence was based on Downs and Black’s “Checklist for Measuring Quality” and Rob 2.0 tool. Certainty of yielded evidence was evaluated with the GRADE system. Seventy-four articles were included on 1781 patients treated for the reconstruction of diaphyseal bone defects, 1496 cases in the inferior limb, and 285 in the upper limb, with trauma being the main cause of bone defect. The meta-analysis identified different outcomes in terms of results and risks. Primary union, complications, and reinterventions were 75%, 26% and 23% for bone allografts and autografts, 91%, 62% and 19% for the bone transport group, and 78%, 38% and 23% for fibular grafts; mean time to union was between 7.8 and 8.9 months in all these groups. Results varied according to the different aetiologies, endoprosthesis was the best solution for tumour, although with a 22% failure rate, while trauma presented a more composite outcome, with fibular grafts providing a faster time to union (6.9 months), while cancellous and cortical-cancellous grafts caused less complications, reinterventions, and failures. The literature about this topic has overall limited quality. However, important conclusions can be made: Many options are available to treat critical-size defects of the diaphysis, but no one appears to be an optimal solution in terms of a safe, satisfactory, and long-lasting outcome. Regardless of the bone defect cause, bone transport techniques showed a better primary union rate, but bone allograft and autograft had fewer complication, reintervention, and failure rates than the other techniques. The specific lesion aetiology represents a critical aspect influencing potential and limitations and therefore the choice of the most suitable technique to address the challenging large diaphyseal defects.

Subject terms: Surgical oncology, Trauma

Introduction

Large diaphyseal defects (LDD) of long bones are a complex and relatively common clinical problem in orthopaedic surgery. LDD are by definition considered incapable of spontaneous healing and therefore represent an indication for surgery, accounting for millions of surgical procedures per year1. Bone loss can be the result of a variety of aetiologies: high-energy trauma, tumour resection, congenital defects, bone resection for non-union, necrosis, and osteomyelitis2. Reconstruction of LDD remains a surgical challenge due to healing difficulties, associated lesions, and the high risk of complications and need for reinterventions. The issues with reconstructing segmental defect are related to the structural and functional importance of long bones, and the high mechanical stress forces involved, particularly for the inferior limb when subjected to weight-bearing. Moreover, LDD can be accompanied by concomitant soft tissue damage and infection2.

LDD have been increasingly studied and several options have been proposed to address this challenge. Bone autografts and allografts were, historically, the first treatments to be developed3–6. Vascularized fibular grafts were then introduced to increase osseointegration and vitality of the reconstructed bone7. In the last decades, bone transport and distraction osteogenesis increased their popularity and, more recently, novel internal lengthening techniques, combined autograft-allograft reconstructions, titanium mesh cages and bioactive membranes were introduced to allow complex biological reconstructions8–10. Intercalary endoprosthesis reconstructions are also possible, particularly when rapid recovery is preferred over long-term durability11. Despite the efforts and advancements in surgical techniques, a consensus on the best surgical approach for long bone diaphysis defects has not been reached, yet. LLD reconstruction impacts heavily on patients, with often long and painful recovery and uncertain outcomes. Thus, it is of outmost importance to understand pros and cons of each option and properly chose the best treatment strategy for each patient.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to understand potential and limitations of the different available surgical techniques used to treat large long-bone diaphyseal defects by focusing on union, complication, re-intervention, and failure rates.

Materials and methods

Literature research

A review protocol was created according to the preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (www.prisma-statement.org). A comprehensive search was performed in the bibliographic databases PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Wiley Cochrane Library from inception up to 16 March 2022. The following terms were used “(diaphyseal OR segmental OR intercalary) AND bone defect AND treatment”, no filters of any type were applied, and the choice “all fields” was applied, when relevant Inclusion criteria were: patients, both male and female, with a diagnosis of segmental bone defects in the diaphysis of the long bones, undergoing surgical treatment of any type for these defects. Comparative and non-comparative studies, with no limitations on the follow-up were included. Case reports or case series describing ≤ 5 cases and articles in languages other than English were excluded. Preclinical and ex vivo studies, studies involving mixed series with not only diaphysis defects, and review articles were also excluded. The purpose of the study was to analyse the main outcomes (primary union, complications, re-interventions, and failures of the different available surgical techniques used to treat large long-bone diaphyseal defects.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (PF, LS) screened all articles on the title and abstract and whether they met the inclusion criteria. After the first screening, the articles that met the inclusion criteria were evaluated on full-text eligibility and were excluded if they met one of the exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). In case of disagreement between the two reviewers (PF, LS) a third reviewer was consulted to reach a consensus (CC).

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Meta-Analyses) flowchart of the study selection process.

Data were independently extracted on a preconceived data extraction form using Excel (Microsoft). The following data were extracted: first author, journal, year of publication, level of evidence, population characteristics, cause of bone loss, surgical technique, graft characteristics, fixation method, surgery time, union rate, complications, reintervention, time to full weight-bearing, functional outcomes, and amputation. In case of missing data, an attempt to contact the corresponding author was made; in case of studies with data upon request, they were asked to the corresponding author. Delayed union was defined as the failure to reach bone union within 6 months after reconstruction, whereas non-union was defined as the failure to reach bone union at the time of the last follow-up after 6 months12. After independent data collection, the reviewers compared the extracted data.

Included articles were sorted in homogenous groups based on the surgical technique used. The interventions were classified into four main groups according to the treatment strategy: vascularized and non-vascularized fibular graft, bone autograft and allograft, bone transport, endoprosthesis. Comparable outcomes were also analysed between different groups of techniques, and their results were descriptively discussed. A meta-analysis was performed focusing on union, complication, re-intervention, and failure rates.

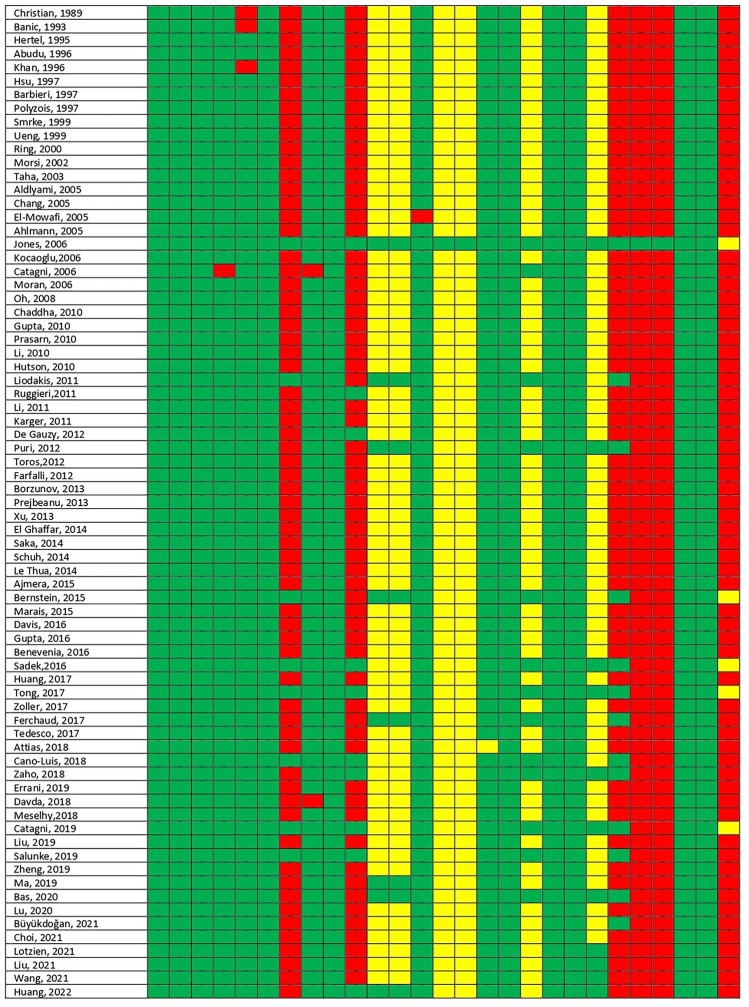

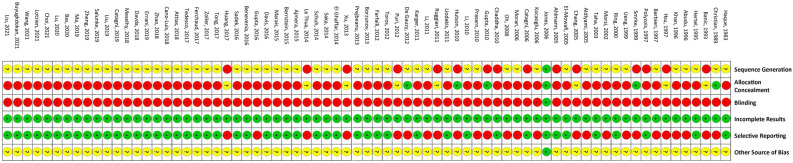

Assessment of risk of bias and quality of evidence

The Downs and Black’s “Checklist for Measuring Quality”13 and the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias (RoB) 2.0 tool was used to evaluate the risk of bias14. The first contains 27 ‘yes’-or-'no’ questions across five sections; and provides a numeric score out of a scale of 32 points. The five sections include questions about the overall quality of the study (10 items), the ability to generalize the findings of the study (3 items), the study bias (7 items), the confounding and selection bias (6 items), and the power of the study (1 item). Rob 2.0 is designed into a fixed set of bias domains, focusing on different aspects of trial design, conduct, and reporting. Within each domain, a series of questions ask information about features of the trial relevant to the risk of bias. A proposed judgement about the risk of bias arising from each domain is generated by an algorithm, based on answers to these questions. The risk of bias can be judged as 'Low', 'Some concerns', or 'High'. The quality of evidence for all outcomes was graded using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation, which classifies the quality of evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low15. Evidence from RCT will start at high quality and be selected to be downgraded by 1 or 2 levels depending on risk factors such as the risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias. Assessment of risk of bias and quality of evidence were completed independently for all outcomes by 2 authors (PF, LS) and a third author (CC) solved any possible discrepancy reaching consensus.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out according to Neyeloff et al.16 using Microsoft Excel. The Mantel–Haenszel method was used to provide pooled rates across the studies. A statistical test for heterogeneity was first conducted with the Cochran Q statistic and I2 metric and was considered the presence of significant heterogeneity with I2 values ≥ 25%. When no heterogeneity was found with I2 < 25%, a fixed-effect model was used to estimate the pooled rates and 95% CIs. Otherwise, a random-effect model was applied, and an I2 metric was evaluated for the random effect to check the correction of heterogeneity. The studies' rate confidence intervals were carried out using the continuity-corrected Wilson interval. The influence of the various techniques, as divided into the four groups, on union rates, complication rates, and reintervention rates was assessed by a z test on the pooled rates with their corresponding 95% CIs. Descriptive statistics were performed to describe the sociodemographic and injury-related characteristics of the patients included in the retrieved studies. Continuous variables were expressed as pooled means with their confidence intervals and standard deviation, using Excel (Microsoft).

Results

Study selection

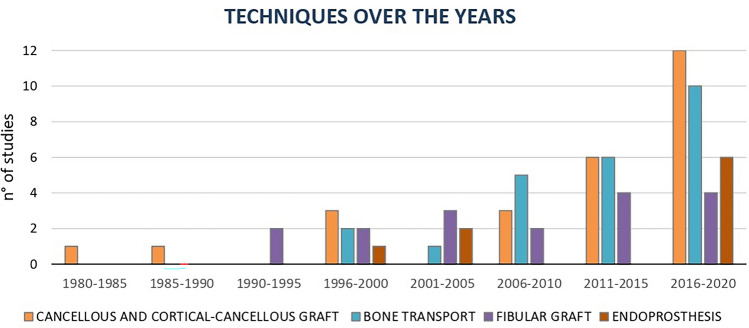

A total of 7903 articles were retrieved after a search on PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases. After removal of duplicates, screening of the title and abstract, and full-text assessment, 74 articles were included for the quantitative synthesis. A summary of the study selection process is shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). The studies were published between 1983 and 2022, thus showing results obtained in the last 39 years, with an increasing number of studies on the treatment of diaphyseal bone defects over time (Fig. 2). Regarding the level of evidence, one study was a Level two randomized controlled trial, seven were Level three comparative studies, and 66 were Level four case series. A summary of all study characteristics is shown in Table 1. Four main groups of reconstruction techniques were evidenced: Bone allograft and autograft (27 study arms), bone transport techniques (25 study arms), vascularized and non-vascularized fibular graft (19 study arms), and endoprosthesis (9 studies). Among them, six studies presented different techniques and were analysed for each technique within the corresponding category. Three studies presented data that were not possible to categorize homogenously, and seven studies presented data that could not be used for the meta-analysis. Thus, a meta-analysis was performed on 64 of the included studies for the union, complication, reintervention, and failure rate. Other aspects could not be used for the meta-analysis because of heterogeneity or lack of data.

Figure 2.

Graphic representation of the trend, over the years, of the four major groups of techniques.

Table 1.

Summary of all the studies characteristics. VFG (vascularised fibular graft), NVFG (non-vascularised fibular graft), BTON (Bone Transport Over Intramedullary Nail), PMMA (Poly Methyl Methacrylate), IMT (Induced Membrane Technique).

| Article | Study design | F-UP | N° of PTS (M:F) | Aetiology | Technique | Defect (CM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haque41 | Case series | NA | 20 (16:4) | Trauma | Hemicylindrical sliding bone graft, bone graft, tibio-fibular synostosis | 3.5 |

| Christian17 | Case series | 27 | 8 (8:0) | Trauma | Massive autogenous cancellous bone graft | 10.2 |

| Banic66 | Case series | 17.3 | 7 (NA) | Trauma | VFG: double strut VFG + cancellous bone graft | 11.6 |

| Herte67 | Case series | 32 | 12 (9:3) | Trauma, Tumor | VFG + cancellous bone graft | 12 |

| Abudu82 | Case series | 65 | 18 (14:4) | Tumor | Endoprosthesis | 21 |

| Khan68 | Case series | 90 | 8 (5:3) | Trauma | VFG + cancellous bone graft | 5 |

| Hsu69 | Case series | 36 | 30 (16:4) | Tumor | VFG + corticocancellous bone graft | 12.9 |

| Barbieri18 | Case series | NA | 12 (10:2) | Trauma | Corticocancellous bone autograft | NA |

| Polyzois61 | Case series | 38 | 42 (29:13) | Trauma, Osteomyelitis, Congenital, Nonunion | Ilizarov distraction osteogenesis | 6 |

| Smrke63 | Case series | 115 | 20 (17:3) | Infection | Ilizarov distraction osteogenesis, Ljubljana traction | 10.4 |

| Ueng42 | Case series | 58 | 15 (14:1) | Nonunion | Corticocancellous bone autograft, VFG | NA |

| Ring19 | Case series | 31 | 15 (9:6) | Nonunion | Autogenous bone graft | 3 |

| Morsi70 | Case series | 32.5 | 7 (6:1) | Nonunion | NVFG | 4.7 |

| Taha80 | Case series | 59.9 | 8 (6:2) | Tumor, Trauma, Osteomyelitis | NVFG | 10.4 |

| Aldlyami84 | Case series | 107 | 35 (22:13) | Tumor | Endoprosthesis | 19 |

| Chang71 | Case series | 24 | 14 (NA) | Tumor | VFG + intercalary allograft | NA |

| El-Mowafi52 | Case series | 27 | 16 (12:4) | Infection | Ilizarov distraction osteogenesis | 6.4 |

| Ahlmann83 | Case series | 21.6 | 6 (4:2) | Tumor | Endoprosthesis | 12.3 |

| Jones20 | RCT | 12 | 30 (NA) | Trauma | Allograft + BMP-2, autograft | 3.8 |

| Kocaoglu54 | Case series | 47.3 | 13 (8:5) | Osteomyelitis | Bone transport over intramedullary nail (BTON) | 10 |

| Catagni48 | Case series | 70.8 | 7 (6:1) | Osteomyelitis, Trauma, Infection | Ilizarov distraction osteogenesis | 15.1 |

| Moran72 | Case series | 36 | 7 (5:2) | Tumor | Capanna technique | 13 |

| Oh57 | Case series | NA | 12 (12:0) | Osteomyelitis | Bone transport over intramedullary nail (BTON) | 5.8 |

| Chaddha49 | Case series | 23.5 | 25 (25:0) | Trauma | Ilizarov distraction osteogenesis | 8.9 |

| Gupta21 | Prospective | NA | 23 (15:8) | Nonunion | Modified Nicoll's technique | 4.7 |

| Hutson63 | Case series | 58 | 18 (13:5) | Trauma | Bone transport | 9.4 |

| Prasarn22 | Case series | 60 | 15 (9:6) | Nonunion | Tricortical iliac crest bone graft | 2.1 |

| Li73 | Case series | 34.1 | 11 (5:6) | Tumor | Capanna technique | 12.1 |

| Liodakis55 | Case series | 61.2 | 22 (17:5) | Trauma | Monorail technique | 7.4 |

| Ruggieri33 | Case series | 29 | 24 (11:13) | Tumor | Modular intramedullary segmental defect fixation system | 10 |

| Li74 | Case series | 27.7 | 7 (4:3) | Tumor | Capanna technique | 10.6 |

| Karger23 | Case series | NA | 84 (79:5) | Trauma | Induced membrane technique | 6.8 |

| De Gauzy (2012) | Case series | NA | 27 (17:10) | Trauma | Induced membrane technique, bone transport, autograft, VFG | NA |

| Puri34 | Case series | 34 | 32 (24:8) | Tumor | Resection, irradiation and reimplantation of bone | 19 |

| Toros81 | Case series | 37 | 6 (3:3) | Nonunion | VFG | NA |

| Farfalli24 | Case series | 73 | 26 (13:13) | Tumor | Intercalary allograft | NA |

| Borzunov47 | Case–control | NA | 83 (54:29) | Trauma, Osteomyelitis, Congenital, Tumor | Ilizarov distraction osteogenesis, gradual tibialisation of the fibula | 12.8 |

| Prejbeanu32 | Case–control | 30 | 12 (6:6) | Tumor | Intramedullary nail + PMMA | 9 |

| Xu (2013) | Case series | 29 | 30 (21:9) | Nonunion | Ilizarov distraction osteogenesis | 6.4 |

| El Ghaffar25 | Prospective | 24 | 12 (12:0) | Trauma | Two-stage reconstruction: debridement + pin, then corticocancellous bone grafting | NA |

| Saka26 | Case series | 32 | 8 (5:3) | Nonunion | (Modified Nicoll's technique) | 1.8 |

| Schuh75 | Case series | 52 | 53 (26:27) | Tumor | VFG, NVFG | NA |

| Le Thua76 | Case series | NA | 26 (18:8) | Trauma, Osteomyelitis, Nonunion | VFG | 10.8 |

| Ajmera44 | Case series | 15 | 25 (25:0) | Trauma | Bone transport | 5.5 |

| Bernstein46 | Case series | 33 | 58 (39:19) | Trauma | Ilizarov distraction osteogenesis, bone transport over intramedullary nail (BTON) | 5.3 |

| Marais58 | Case series | 28 | 7 (NA) | NA | Bone transport | 7 |

| Davis27 | Case series | 42 | 7 (5:2) | Nonunion | Staged reconstruction technique (allograft + IM nail) | 4.9 |

| Gupta28 | Case series | 21.5 | 9 (7:2) | Nonunion | Induced membrane technique | 5.2 |

| Benevenia88 | Case series | 14 | 41 (27:14) | Tumor | Endoprosthesis | NA |

| Sadek35 | Case–control | NA | 30 (24:6) | Nonunion | Two-steps debridment + iliac graft vs one-step Ilizarov distraction osteogenesis | 4.6 |

| Huang85 | Case series | 9 | 16 (6:10) | Tumor | Intercalary endoprosthesis | 10.2 |

| Tong36 | Case–control | 25.3 | 39 (30:9) | Osteomyelitis | Induced membrane technique, Ilizarov distraction osteogenesis | 6.8 |

| Zoller29 | Case series | 18.3 | 9 (8:1) | Trauma | Induced membrane technique | 6.4 |

| Ferchaud53 | Case series | 62 | 7 (NA) | Trauma | Bone transport over intramedullary nail (BTON) | 7.2 |

| Tedesco86 | Case series | 39 | 6 (3:3) | Tumor | Endoprosthesis | NA |

| Attias30 | Case series | 55 | 17 (14:3) | Trauma | Cancellous bone graft (Titanium mesh cage) | 8.4 |

| Cano-Luis77 | Case series | 166.8 | 14 (13:1) | Trauma | VFG | NA |

| Zaho90 | Case series | 8.6 | 9 (4:5) | Tumor | Endoprosthesis | 7.8 |

| Errani78 | Case series | 96 | 81 (56:25) | Tumor | Massive bone allograft + VFG | 15.9 |

| Davda51 | Case series | NA | 10 (8:2) | Nonunion | Bone transport over intramedullary nail (BTON) | 7 |

| Meselhy59 | Prospective | 40.5 | 14 (10:4) | Osteomyelitis, Trauma | Ilizarov distraction osteogenesis | 13.2 |

| Catagni50 | Case–control | 43.3 | 86 (77:9) | Trauma, Nonunion, Osteomyelitis | Bifocal fibular transfer, trifocal fibular transfer | 13 |

| Liu79 | Case series | 65.1 | 15 (9:6) | Tumor | VFG + autograft | 19.8 |

| Salunke37 | Case series | 30.9 | 28 (NA) | Tumor | NVFG, extracorporeal radiotherapy autograft | 14.9 |

| Zheng87 | Case series | 13.7 | 49 (23:26) | Tumor | Endoprosthesis | 9.2 |

| Ma31 | Case series | 19.1 | 51 (32:19) | Trauma | Cancellous wrap + titanium mesh cage/line mesh/line-binding, IMT | 5.9 |

| Bas45 | Case series | 25.7 | 40 (26:14) | Trauma, Nonunion | Bone transport over intramedullary nail (BTON) | 7.1 |

| Lu56 | Case series | 25.8 | 12 (10:2) | Trauma, Nonunion | Bone transport | 6.7 |

| Choi38 | Case series | 18 | 8 (4:4) | Trauma | Autologous iliac graft | 2.6 |

| Lotzien39 | Case series | 33.1 | 31 (30:1) | Nonunion | Induced membrane technique | 8.3 |

| Huang (2021) | Comparative | 29.1 | 77 (54:23) | Trauma, Osteomyelitis | Bone transport + graft + internal fixation / bone transport | 13.5 |

| Wang40 | Case series | NA | 42 (17:25) | Trauma | Induced membrane technique | 6.3 |

| Büyükdoğan89 | Case series | 17 | 22 (15:7) | Tumor | Endoprosthesis | 10 |

| Liu65 | Case series | 28.2 | 12 (10:2) | Osteomyelitis | Bone transport | 5.1 |

Patients and treatments characteristics

A total of 1781 patients were included in the analysis: 1496 cases with inferior limb reconstruction and 285 cases with upper limb reconstruction (tibia 60.0%, femur 24.5%, humerus 7.1%, radius 4.7%, and ulna 3.7%). While 15 articles reported mixed series of both inferior and upper limbs, 13 articles focused only on the upper limb reconstruction and 46 articles presented only results on the inferior limb. The average bone defect was 9.0 cm (range 1.6–31 cm). The aetiology of the defects included trauma in 751 cases (42.2%), tumour in 554 cases (31.1%), non-union after previous treatment in 289 cases (16.2%), infection in 177 cases (9.9%), and congenital defect in ten cases (0.6%). Aetiology of the defects are shown in Table 2. Gender was represented by 70.4% men and 29.6% women, and age presented a range of 2–86 years. The mean follow-up was 40.9 months (range 1 to 157 months). Results obtained for each treatment group are analysed in detail in the following paragraphs. Table 3 shows a summary of the results. Moreover, data are also reported quantifying the primary union, time to union, complication, reintervention, and failure rates of the different treatments based on the main aetiology subgroups trauma and tumour (see Tables 4 and 5 for details). A summary of complications is reported in Table 6.

Table 2.

Summary of bone defect causes.

| Treatment groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causes of bone defect | Fibular graft (%) | Bone graft (%) | Bone transport (%) | Endoprosthesis (%) | Various techniques (%) |

| Tumor | 73.1 | 18.8 | 1.0 | 100 | 0 |

| Trauma | 17.1 | 53.7 | 55.6 | 0 | 75.8 |

| Nonunion | 6.7 | 23.9 | 20.1 | 0 | 24.2 |

| Infection | 3.1 | 3.6 | 21.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Congenital defect | 0 | 0 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 |

Table 3.

Summary of all outcomes.

| Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups of treatment | Primary union | Time to union | Complication | Reintervention | Failure |

|

Bone allograft and autograft 27 studies, 564 patients |

75% (C.I. 72%–78%) |

7.8 months (1–27 months) |

26% (C.I. 22%–30%) |

23% (C.I. 19%–28%) |

8% (C.I. 6%–11%) |

|

Bone transport 25 studies, 676 patients |

91% (C.I. 89%–93%) |

8.9 months (3–52 months) |

62% (C.I. 59%–65%) |

19% (C.I. 16%–22%) |

8% (C.I. 6%–10%) |

|

Vascular and non-vascular fibular graft 19 studies, 327 patients |

78% (C.I. 73%–82%) |

8.3 months (2–33 months) |

38% (C.I. 33%–43%) |

23% (C.I. 19%–28%) |

8% (C.I. 5%–12%) |

|

Endoprosthesis 9 studies, 202 patients |

NA | NA |

26% (C.I. 21%–32%) |

20% (C.I. 15%–28%) |

22% (C.I. 18%–28%) |

Table 4.

Summary of trauma studies outcomes.

| Trauma outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups of treatment | Primary union | Time to union | Complication | Reintervention | Failure |

|

Bone allograft and autograft 12 studies, 294 patients |

89% (C.I. 85%–91%) |

8.9 months (1–27 months) |

22% (C.I. 18%–28%) |

20% (C.I. 15%–27%) |

1% (C.I. 1%–3%) |

|

Bone transport 8 studies, 176 patients |

90% (C.I. 85%–93%) |

9.8 months (4–22 months) |

69% (C.I. 64%–74%) |

42% (C.I. 34%–51%) |

NA |

|

Vascular and non-vascular Fibular graft 4 studies, 30 patients |

89% (C.I. 76%–96%) |

6.9 months (2–33 months) |

40% (C.I. 27%–56%) |

41% (C.I. 27%-56%) |

9% (C.I. 3%–24%) |

Table 5.

Summary of tumor studies outcomes.

| Tumor outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups of treatment | Primary union | Time to union | Complication | Reintervention | Failure |

|

Bone allograft and autograft 5 studies, 106 patients |

82% (C.I. 73%–88%) |

NA |

39% (C.I. 31%–48%) |

31% (C.I. 23%–40%) |

NA |

|

Vascular and non-vascular fibular graft 9 studies, 246 patients |

74% (C.I. 68%–79%) |

8.4 months (2–27 months) |

38% (C.I. 33%–44%) |

26% (C.I. 21%–31%) |

13% (C.I. 9%–19%) |

|

endoprosthesis 9 studies, 202 patients |

NA | NA |

26% (C.I. 21%–32%) |

20% (C.I. 15%–28%) |

22% (C.I. 18%–28%) |

Table 6.

Summary of all complications.

| Groups of treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | Fibular graft | Bone graft | Bone transport | Endoprosthesis | Various techniques |

| Fracture | 23.9% (31) | 4.9% (9) | 3.8% (16) | 11.3% (8) | 2.7% (1) |

| Infection | 11.5% (15) | 28.0% (51) | 24.7% (105) | 7.1% (5) | 10.8% (4) |

| Donor site morbidity | 2.3% (3) | 2.7% (5) | 1.4% (6) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Nonunion | 16.7% (22) | 25.3% (46) | 9.6% (41) | 0% (0) | 21.6% (8) |

| Limb deformity | 6.2% (8) | 3.3% (6) | 7.5% (32) | 2.9% (2) | 13.5% (5) |

| Vascular injury | 0.8% (1) | 1.6% (3) | 0.7% (3) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Flap necrosis | 2.3% (3) | 4.4% (8) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 8.2% (3) |

| Mechanical problems | 4.6% (6) | 8.2% (15) | 4.7% (20) | 64.3% (36) | 0% (0) |

| Wound deiscency | 11.5% (15) | 3.3% (6) | 6.6% (28) | 2.9% (2) | 0% (0) |

| Nerve palsy | 2.3% (3) | 0.5% (1) | 4.0% (17) | 4.3% (2) | 13.5% (5) |

| Hematoma | 0% (0) | 1.1% (2) | 0.9% (4) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Osteomyelitis | 0.8% (1) | 0% (0) | 1.6% (7) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Pseudoarthrosis | 0.8% (1) | 0% (0) | 2.6% (11) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Rom limitation | 2.3% (3) | 3.3% (6) | 15.3% (65) | 0% (0) | 29.7% (11) |

| Chronic pain | 3.9% (5) | 0% (0) | 2.4% (10) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Implant allergy | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0.5% (2) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Limb length Discrepancy | 4.6% (6) | 3.8% (7) | 8.2% (35) | 2.9% (2) | 0% (0) |

| Delayed union | 5.4%(7) | 9.3% (17) | 6.1% (26) | 4.3% (3) | 0% (0) |

Bone allograft and autograft

Bone allograft and autograft was used in 27 study arms17–43 for a total of 564 patients (mean age 35.0 years): the inferior limb was involved in 78.2% of the cases, while the upper limb accounted for 21.8% of the cases. The defect was exclusively due to trauma in twelve studies, non-union in nine studies, tumour resection in five studies, and infection in one study. The average bone defect was 7.3 cm (range 0.5–27.8 cm), and the average follow-up was 33.3 months (range 6–180 months). A two-stage induced membrane technique (IMT) was used in seven studies, with massive autologous cancellous bone graft as a second step after the polymethacrylate spacer, while in nine studies cortical-cancellous iliac bone autograft was used, fixed either with external or internal fixation devices. In two studies autogenous cancellous bone graft was used alone, fixed with a plate and screws, while intercalary allograft with cancellous bone graft was used in two studies. Two studies reported the usage of titanium mesh cages with autologous bone graft, two studies the reimplantation of extracorporeal devitalized cancerous bone, one study reported the use of BMP-2, one study reported the application of multiple wrapped cancellous bone autograft methods, and another study reported a solution with an intramedullary nail and polymethacrylate spacer as a definitive treatment. Four studies did not report data on primary unions; in the others, the pooled union rate was 75% (C.I. 72%–78%). The average time to union was 7.8 months (range 1–27 months). Complications were reported 182 times, with a mean of 26% (C.I. 22%–30%) (details in Table 6). The reintervention rate was 23% on average (C.I. 19%–28%), and the failure rate was 8% (C.I. 6%–11%). Outcomes of trauma and tumor treatment are detailed in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. A specific analysis of the two-step Masquelet technique28,29,36,39,40 underlined a primary union rate of 53%, a complication rate of 15.0%, a reintervention rate of 27.2%, and a failure rate of 15.0%. Finally, in the studies on bone allografts or autografts used alone17–20,22,24,25,30,33,42 a pooled primary union rate of 87.0%, a time to union of 5.3 months, a complication rate of 31.0%, a reintervention rate of 26%, and a failure rate of 3.9% were reported.

Bone transport

Bone transport with distraction osteogenesis has become over the years one of the most used techniques for bone regeneration. A total of 25 studies used a bone transport technique35,36,43–65 for a total of 676 patients (mean age 35.4 years). The inferior limb was involved in 98.1% of the cases, while the upper limb accounted for 1.9% of the cases. The defect was exclusively due to trauma in seven studies, infection in seven studies, to non-union in three studies, while eight studies reported mixed aetiology. The average bone defect was 8.8 cm (range 2.7–28 cm), and the average follow-up was 35.7 months (range 6–168 months). The Ilizarov method with external fixation was used in 15 studies35,36,46–50,52,56,59–62,65, intramedullary nailing and/or external fixation was used in eight studies43,45,51,53–55,57,64, a monolateral external fixation was used in one study44, and bone transport with a five-ring circular external fixator in one study58. One of the studies in the Ilizarov group was a case–control comparing bifocal versus trifocal fibular transfer, showing better primary union rate, fewer complications and reinterventions in the trifocal group. The primary union was obtained in 91% of the patients (C.I. 89%–93%); the mean external fixator time was 8.9 months (range 3–52 months). Complications were reported 425 times, with a pooled ratio of 62% (C.I. 59%–65%) but most of them were minor complications and did not require any invasive intervention (details in Table 6). The reintervention rate was 19% (C.I. 16%–22%), and the failure rate was 8% (C.I. 6%–10%). Outcomes of trauma treatment are detailed in Table 4.

A subgroup of six studies45,46,50,51,53,54,57 focusing on the bone transport approach showed a primary union rate of 89.7% with a mean external fixator time of 6.6 months (range 4.2–9.3 months), a complication rate of 66.9%, a reintervention rate of 29.8% and a failure rate of 3.7%.

Vascular and non-vascular fibular graft

The fibular graft was the elective technique in 19 studies37,42,43,66–81, for a total of 327 patients (mean age 22.2 years): the inferior limb was involved in 81.3% of the cases, while the upper limb accounted for 18.7% of the cases. The defect was exclusively due to tumor resection in nine studies, trauma in four studies, and non-union after previous treatment in three studies, while three studies reported mixed aetiology. The average defect was 13.4 cm (range 1–25 cm). The average follow-up was 62.8 months (range 6–276 months). In all except four studies, the graft was a vascularized fibular graft, in some cases used in combination with cortical-cancellous bone autograft or allograft. The primary union was achieved in 78% of the patients (C.I. 73%–82%), in an average time of 8.3 months (range 2–33 months). Complications were reported 130 times, with a complication rate of 38% (C.I. 33%–43%) (details in Table 6). The reintervention rate was 23% on average (C.I. 19%–28%), and the failure rate was 8% (C.I. 5%–12%). Outcomes of trauma and tumor treatment are detailed in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. A subgroup of studies focused specifically on the Capanna technique72,74, reporting a primary union rate of 82.7%, in an average time of 7.6 months, a complication rate of 43.8%, a reintervention rate of 25.3%, and a failure rate of 8%. For non-vascular fibular grafts37,70,75,80 the mean primary union rate was 73.0%, with a complication rate of 49.0% and a reintervention rate of 42.0%.

Endoprosthesis

Intercalary endoprosthesis was chosen as a solution to the diaphyseal bone defect in nine studies82–90, for a total of 202 patients (mean age 52.7 years). Bone defects involved the inferior limb in 54.5% and the upper limb in 45.5% of the time, and the aetiology of the defect was tumour resection in all the retrieved studies. The bone defect measured on average 13 cm (range 6–28 cm), and the follow-up of the studies was 35.2 months (range 1–306 months). A meta-analysis on the primary union rate was not performed due to the lack of data in the retrieved studies; however, it was possible to calculate the complication rate (mean 26%, C.I. 21%–32%), total complications 60, and the reintervention rate (mean 20%, C.I. 15%–28%). The meta-analysis on failure rate showed a mean of 22% (C.I. 18%–28%).

Risk of bias and quality of evidence

The Downs and Black’s Checklist13 gives each study an excellent ranking for points ≥ 26, a good ranking for points between 20 and 25, a fair ranking for points between 15 and 19, and a poor ranking for a score ≤ 14 points. Accordingly, among the retrieved studies four studies were classified as poor, 50 studies as fair, and ten studies as good (Fig. 3). The main factors influencing the study quality was the inaccuracy of some studies in reporting data and results. The Rob 2.0 tool14 reported that one study was to be considered at “low risk of bias”, 53 studies with “some concerns for bias”, and 20 studies at “high risk of bias” (Fig. 4). Based on the GRADE tool, the quality of evidence of all the four primary outcomes (primary union, complications, reintervention, and failures) was judged ranging from “low” to “very low”.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias of all the included studies, evaluated in accordance with the “Downs and Black’s tool for assessing the risk of bias”.

Figure 4.

Risk of bias of all the included studies, evaluated in accordance with the Rob 2.0 tool.

Discussion

The main finding of this meta-analysis is that different treatments offer suitable results to address the complex diaphyseal bone defects, but each one showing specific indications, strengths, and critical aspects. Despite an overall high final union rate, relatively high complication and reintervention rates were retrieved, with important differences among the various treatments, which should be considered when choosing the proper surgical approach.

The correct approach for a LDD should be chosen considering each patient individually, weighing the pros and cons of each technique, aiming to achieve safe and reproducible outcomes with low reintervention rates. The results from this meta-analysis contribute to shed some light in this direction. In particular, the first finding brought to the attention by this systematic review is the inclusion of 74 studies for a total of 1781 patients; such large numbers underline the importance of diaphyseal bone defect treatment. A lot of research efforts have been put into this field, which also shows an evolution over time. A temporal trend emerged when investigating the various treatments for LDD (Fig. 2): during the 80 s and until the mid-90 s there were only a few studies, mainly focused earlier on bone allograft or autograft and, later, on vascularized or non-vascularized fibular grafts17,41,66,67. Then, from the end of the 90 s, more and more studies were progressively published, along with a growing interest in other approaches such as bone transport and endoprosthesis54,57,60–62,82–84. Finally, in the last years, all treatments were increasingly addressed but with a focus above all on bone transport and, also due to the impulse of new augmentation procedures, with several studies on bone allograft or autografts27–29,31,35,36,45,50,51,53,56,59,77,91.

Traditionally, the surgical management of LDD involved bone grafting92, relying on the combination of mechanical stability and an osteoinductive substrate. In this meta-analysis, bone allografts or autografts have been used alone or within more advanced biological augmentation techniques. Among the retrieved studies, the mean primary union rate was 75%, an important finding both in terms of an overall good outcome, but also for the low heterogeneity of the findings, underlying the reliability and consistency of the results obtained by this approach17–43. Moreover, while a similar time to union and reintervention rates were found for other techniques, this approach presented one of the lowest complication and failure rates (Table 3). Interestingly, results obtained with bone allografts or autografts used alone17–20,22,24,25,30,33 seemed to align with those of more complex combined procedures, apart from a major rate of complications, underlining the need for better-targeted studies to demonstrate the real potential of biological augmentation techniques for cancellous or cortical-cancellous bone grafting. Finally, in the early 2000s, the Masquelet technique started to raise interest, a two-stage reconstruction technique based on cancellous bone graft and induced membrane technique93. Since then, the induced membrane technique was increasingly used; five studies where it was reported as a single technique could be included in this meta-analysis28,29,36,39,40, showing overall results comparable to those of the other autograft or allograft techniques.

The use of autologous fibular graft has been also well documented over time, either vascularized or non-vascularized. The vascularized fibula was introduced in 1975 by Taylor et al.7 to maximize the healing potential and bone viability while taking advantage of the possibility of treating simultaneously soft tissue damage through combined tissue flaps. In this meta-analysis only four studies used exclusively non vascularized fibula, while in the majority vascularized fibula was used, either pedicled or free. Overall, the non-vascularized fibula showed less satisfactory results in terms of primary union, complications, and reintervention rate as compared to the vascularized fibula. The use of a fibular graft proved to be a demanding surgery94, with the meta-analysis underlying similar results in terms of time to union and need for reinterventions, but the lower primary union and higher failure and complication rates with respect to other approaches. Moreover, the majority of complications were severe and mainly represented by fractures, which often healed at the last follow up but caused long-term discomfort and healing time. In light of these limitations, Capanna et al.95 combined allograft and intramedullary VFG to strengthen the construct. However, even with technique modifications and the latest developments, fibular grafts remain a challenging surgical approach96,97.

The bone transport technique with distraction osteogenesis with external fixation is another well-known treatment introduced in 1969 by Ilizarov for bone lesions98. Nowadays, it remains one of the most useful and versatile approaches to address critical-size defects99, with the overall higher primary union rate among the possible strategies. However, there are well-known downsides: it takes several months and a fully compliant patient to be completed, and there is a high risk of complications100. These aspects emerged clearly from this meta-analysis; the mean primary union rate was 91% but with a complication rate of 62%35,36,43–65. The large majority of complications were due to infection, especially superficial pin tract infections that often resolved without any further operative intervention49,54,56,57,59. Other relevant problems were ROM limitations, limb length discrepancy and deformity. To overcome these problems, in the last decades new bone transport techniques using intramedullary devices were introduced, minimizing external fixation time and joint contractures, thus increasing patient compliance and satisfaction, while achieving bone union faster101–103. Finally, a comparison between bifocal or trifocal bone transport was reported in one study50, finding the first to be quicker, more effective, and with a lower complication rate. Further RCTs are needed to confirm the potential and limitations of new bone transport techniques for the treatment of diaphyseal defects.

In the case of short life expectancy or other contraindications to biological reconstruction, intercalary endoprosthesis has been proposed for diaphyseal defects104. Endoprosthesis provides a valid solution when aiming for early weight-bearing, immediate stability, and fast recovery, but this comes at the price of high risks of mechanical complications such as aseptic loosening and periprosthetic fractures33. Therefore, the main indication is for elderly cancer patients whose healing capacity is poor and the rapid restoration of function is more important than the long term durability11. This was confirmed by the meta-analysis, the mean age of endoprosthesis patients was 52.7 years old, greater than that of the other techniques, and all of the patients had a diaphyseal tumour82–86,88–90. The complication rate was 26%, the reintervention rate 20%, and, most important, a 22% failure rate was retrieved, confirming the limits of endoprosthesis as a long-lasting solution105. Future improvements aiming to better prosthesis stability, such as changes in prosthesis design or better fixation methods, are needed to provide a better solution in terms of outcome and complications for these complex and fragile patients.

Different techniques are applied for the treatment of different types of patients and lesions, which could influence the results in terms of outcomes and complications. Among the four groups of techniques retrieved, the bone defect causes that led to the surgical intervention were different: bone allograft and autograft and bone transport were used mainly for traumatized patients (53.7% and 55.6%), almost all patients with a diaphyseal bone defect caused by infection were treated with bone transport techniques, while tumor resection was the indication of 73.1% of the fibular graft and 100% of the endoprosthesis (Table 2).

In this light, a specific investigation was performed to define the results of the treatment options when addressing the same etiological target. The main aetiology groups are represented by tumor and trauma (Tables 4 and 5). Concerning tumors, it is interesting to underline the lower indications for some techniques: bone transport was not applied and when bone allograft and autograft, as well as fibular grafts, were used, they offered lower results than for other treatment indications. Furthermore, this sub-analysis revealed that, despite the previously mentioned limitations, endoprosthesis still presents the lower complication and reintervention rates with respect to the other options (Table 5). Finally, a specific analysis was focused on the trauma that was the most common cause of LDD. In these patients, similar results were achieved in terms of primary union rate, but marked differences were found for different treatment options (Table 4). Fibular grafts provided a faster time to union with respect to other treatment indications and showed to gain a two-to-three months advantage versus other solutions for patients affected by trauma (Table 4). On the other hand, high complication, reintervention, and failure rates were documented in these patients, which suffered fewer complications, reinterventions, and failures when treated with bone allografts and autografts (Table 4).

This systematic review and meta-analysis included numerous studies and a high number of patients. Nonetheless, there are limitations to point out. Among all, the risk of bias and the low level of evidence of the studies, as documented by the Downs and Black’s Checklist for Measuring Quality, the Rob 2.0 tool and the GRADE system. Another limitation is the lack of prospective PROSPERO registration. Furthermore, the high heterogeneity of the included studies for defect aetiology, patient populations, and techniques, add to the literature weaknesses. In light of all this, there is a clear need for standardized, properly designed comparative studies to search for the best clinical practice in each specific scenario. However, important indications could be drawn from the meta-analysis of the available literature. First of all, this meta-analysis documented that many options are available to treat LDD, but no one appears as an optimal solution in terms of safe, satisfactory, and long-lasting outcomes, which urges the development of better surgical strategies. Moreover, many aspects have to be taken into account when choosing the most suitable approach for LDD, as results in terms of primary union rate and time to union time, as well as risks in terms of complication, reintervention, and failure rates. The results of this meta-analysis underlined the potential and limitations of the different treatment options according to the different clinical scenarios, which could help the clinicians in understanding the advantages, disadvantages, and overall, the most suitable option when treating the challenging LDD.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Elettra Pignotti for her help with the statistical analysis.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, G.F.; methodology, A.D.M.; investigation, data curation and writing—original draft preparation, P.F. and L.S.; writing—review and editing, C.E. and G.F.; supervision, G.F. and C.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Pietro Feltri and Luca Solaro.

References

- 1.Stanovici J, Le Nail LR, Brennan MA, Vidal L, Trichet V, Rosset P, et al. Bone regeneration strategies with bone marrow stromal cells in orthopaedic surgery. Curr. Res. Transl. Med. 2016;64(2):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.retram.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reichert JC, Saifzadeh S, Wullschleger ME, Epari DR, Schütz MA, Duda GN, et al. The challenge of establishing preclinical models for segmental bone defect research. Biomaterials. 2009;30(12):2149–2163. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enneking WF, Morris JL. Human autologous cortical bone transplants. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1972;87:28–35. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mankin HJ, Doppelt SH, Sullivan TR, Tomford WW. Osteoarticular and intercalary allograft transplantation in the management of malignant tumors of bone. Cancer. 1982;50(4):613–630. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820815)50:4<613::AID-CNCR2820500402>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mankin HJ, Gebhardt MC, Tomford WW. The use of frozen cadaveric allografts in the management of patients with bone tumors of the extremities. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1987;18(2):275–289. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(20)30391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panagopoulos GN, Mavrogenis AF, Mauffrey C, Lesenský J, Angelini A, Megaloikonomos PD, et al. Intercalary reconstructions after bone tumor resections: A review of treatments. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. Orthop. Traumatol. 2017;27(6):737–746. doi: 10.1007/s00590-017-1985-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor GI, Miller GD, Ham FJ. The free vascularized bone graft. A clinical extension of microvascular techniques. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1975;55(5):533–544. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197505000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choong PF, Sim FH. Limb-sparing surgery for bone tumors: New developments. Semin. Surg. Oncol. 1997;13(1):64–69. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2388(199701/02)13:1<64::AID-SSU10>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gugenheim JJ., Jr The Ilizarov method. Orthopedic and soft tissue applications. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1998;25(4):567–578. doi: 10.1016/S0094-1298(20)32449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roffi A, Krishnakumar GS, Gostynska N, Kon E, Candrian C, Filardo G. The role of three-dimensional scaffolds in treating long bone defects: Evidence from preclinical and clinical literature-a systematic review. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017;2017:8074178. doi: 10.1155/2017/8074178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mavrogenis AF, Sakellariou VI, Tsibidakis H, Papagelopoulos PJ. Adamantinoma of the tibia treated with a new intramedullary diaphyseal segmental defect implant. J. Int. Med. Res. 2009;37(4):1238–1245. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houben RH, Rots M, van den Heuvel SCM, Winters HAH. Combined massive allograft and intramedullary vascularized fibula as the primary reconstruction method for segmental bone loss in the lower extremity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JBJS Rev. 2019;7(8):e2. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.18.00166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neyeloff JL, Fuchs SC, Moreira LB. Meta-analyses and Forest plots using a microsoft excel spreadsheet: Step-by-step guide focusing on descriptive data analysis. BMC. Res. Notes. 2012;5:52. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christian EP, Bosse MJ, Robb G. Reconstruction of large diaphyseal defects, without free fibular transfer, in Grade-IIIB tibial fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1989;71(7):994–1004. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198971070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbieri CH, Mazzer N, Aranda CA, Pinto MM. Use of a bone block graft from the iliac crest with rigid fixation to correct diaphyseal defects of the radius and ulna. J. Hand Surg. (Edinb. Scotl.) 1997;22(3):395–401. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(97)80411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ring D, Jupiter JB, Quintero J, Sanders RA, Marti RK. Atrophic ununited diaphyseal fractures of the humerus with a bony defect: Treatment by wave-plate osteosynthesis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Vol. 2000;82(6):867–871. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B6.0820867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones AL, Bucholz RW, Bosse MJ, Mirza SK, Lyon TR, Webb LX, et al. Recombinant human BMP-2 and allograft compared with autogenous bone graft for reconstruction of diaphyseal tibial fractures with cortical defects. A randomized, controlled trial. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2006;88(7):1431–1441. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta DK, Kumar G. Gap nonunion of forearm bones treated by modified Nicoll's technique. Indian J. Orthop. 2010;44(1):84–88. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.58611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prasarn ML, Ouellette EA, Miller DR. Infected nonunions of diaphyseal fractures of the forearm. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2010;130(7):867–873. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-1016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karger C, Kishi T, Schneider L, Fitoussi F, Masquelet AC. Treatment of posttraumatic bone defects by the induced membrane technique. Orthop. Traumat. Surg. Res. OTSR. 2012;98(1):97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farfalli GL, Aponte-Tinao L, Lopez-Millán L, Ayerza MA, Muscolo DL. Clinical and functional outcomes of tibial intercalary allografts after tumor resection. Orthopedics. 2012;35(3):e391–e396. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120222-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghaffar KAE, Diab RA, Kotb AME-M. Management of Infected nonunited femoral fracture with large bone defects: A technique. Tech. Orthop. 2019;34:30–34. doi: 10.1097/BTO.0000000000000296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saka G, Sağlam N, Kurtulmuş T, Avcı CC, Akpınar F. Treatment of diaphyseal forearm atrophic nonunions with intramedullary nails and modified Nicoll's technique in adults. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 2014;48(3):262–270. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2014.3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis JA, Choo A, O'Connor DP, Brinker MR. treatment of infected forearm nonunions with large complete segmental defects using bulk allograft and intramedullary fixation. J. Hand Surg. 2016;41(9):881–887. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta G, Ahmad S, Mohd Z, Khan AH, Sherwani MK, Khan AQ. Management of traumatic tibial diaphyseal bone defect by "induced-membrane technique". Indian J. Orthop. 2016;50(3):290–296. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.181780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zoller SD, Cao LA, Smith RA, Sheppard W, Lord EL, Hamad CD, et al. Staged reconstruction of diaphyseal fractures with segmental defects: Surgical and patient-reported outcomes. Injury. 2017;48(10):2248–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attias N, Thabet AM, Prabhakar G, Dollahite JA, Gehlert RJ, DeCoster TA. Management of extra-articular segmental defects in long bone using a titanium mesh cage as an adjunct to other methods of fixation: A multicentre report of 17 cases. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-b(5):646–651. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B5.BJJ-2017-0817.R2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma Y, Gu S, Yin Q, Li H, Wu Y, Zhou Z, et al. Application of multiple wrapped cancellous bone graft methods for treatment of segmental bone defects. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019;20(1):346. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2713-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prejbeanu R, Vlad Daliborca C, Dumitrascu V, Vermesan D, Mioc M, Abbinante A, et al. Application of acrylic spacers for long bone defects after tumoral resections. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013;17(17):2366–2371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruggieri P, Mavrogenis AF, Bianchi G, Sakellariou VI, Mercuri M, Papagelopoulos PJ. Outcome of the intramedullary diaphyseal segmental defect fixation system for bone tumors. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011;104(1):83–90. doi: 10.1002/jso.21893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puri A, Gulia A, Jambhekar N, Laskar S. The outcome of the treatment of diaphyseal primary bone sarcoma by resection, irradiation and re-implantation of the host bone: Extracorporeal irradiation as an option for reconstruction in diaphyseal bone sarcomas. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Vol. 2012;94(7):982–988. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B7.28916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadek AF, Laklok MA, Fouly EH, Elshafie M. Two stage reconstruction versus bone transport in management of resistant infected tibial diaphyseal nonunion with a gap. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2016;136(9):1233–1241. doi: 10.1007/s00402-016-2523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tong K, Zhong Z, Peng Y, Lin C, Cao S, Yang Y, et al. Masquelet technique versus Ilizarov bone transport for reconstruction of lower extremity bone defects following posttraumatic osteomyelitis. Injury. 2017;48(7):1616–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salunke AA, Shah J, Chauhan TS, Parmar R, Kumar A, Koyani H, et al. Reconstruction with biological methods following intercalary excision of femoral diaphyseal tumors. J. Orthop. Surg. (Hong Kong) 2019;27(1):2309499018822242. doi: 10.1177/2309499018822242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi SW, Bae JY, Shin YH, Song JH, Kim JK. Treatment of forearm diaphyseal non-union: Autologous iliac corticocancellous bone graft and locking plate fixation. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res OTSR. 2021;107(8):102833. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2021.102833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lotzien S, Rosteius T, Reinke C, Behr B, Lehnhardt M, Schildhauer TA, et al. Reconstruction of septic tibial bone defects with the masquelet technique and external ring fixation-a low healing rate and high complication and revision rates. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2021;35(9):e328–e336. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000002065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang P, Wu Y, Rui Y, Wang J, Liu J, Ma Y. Masquelet technique for reconstructing bone defects in open lower limb fracture: Analysis of the relationship between bone defect and bone graft. Injury. 2021;52(4):988–995. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haque IU. The treatment of tibial diaphysial bone defects in adults. Med. J. Zamb. 1983;17(3):65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ueng SW, Wei FC, Shih CH. Management of femoral diaphyseal infected nonunion with antibiotic beads local therapy, external skeletal fixation, and staged bone grafting. J. Trauma. 1999;46(1):97–103. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199901000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sales de Gauzy J, Fitoussi F, Jouve JL, Karger C, Badina A, Masquelet AC. Traumatic diaphyseal bone defects in children. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. OTSR. 2012;98(2):220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ajmera A, Verma A, Agrawal M, Jain S, Mukherjee A. Outcome of limb reconstruction system in open tibial diaphyseal fractures. Indian J. Orthop. 2015;49(4):429–435. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.159638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bas A, Daldal F, Eralp L, Kocaoglu M, Uludag S, Sari S. Treatment of tibial and femoral bone defects with bone transport over an intramedullary nail. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2020;34(10):e353–e359. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernstein M, Fragomen AT, Sabharwal S, Barclay J, Rozbruch SR. Does integrated fixation provide benefit in the reconstruction of posttraumatic tibial bone defects? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2015;473(10):3143–3153. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4326-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borzunov DY, Chevardin AV. Ilizarov non-free bone plasty for extensive tibial defects. Int. Orthop. 2013;37(4):709–714. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-1799-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Catagni MA, Camagni M, Combi A, Ottaviani G. Medial fibula transport with the Ilizarov frame to treat massive tibial bone loss. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2006;448:208–216. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000205878.43211.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chaddha M, Gulati D, Singh AP, Singh AP, Maini L. Management of massive posttraumatic bone defects in the lower limb with the Ilizarov technique. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2010;76(6):811–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Catagni MA, Azzam W, Guerreschi F, Lovisetti L, Poli P, Khan MS, et al. Trifocal versus bifocal bone transport in treatment of long segmental tibial bone defects. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-b(2):162–169. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B2.BJJ-2018-0340.R2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davda K, Heidari N, Calder P, Goodier D. 'Rail and Nail' bifocal management of atrophic femoral nonunion. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-b(5):634–639. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B5.BJJ-2017-1052.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.El-Mowafi H, Elalfi B, Wasfi K. Functional outcome following treatment of segmental skeletal defects of the forearm bones by Ilizarov application. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2005;71(2):157–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferchaud F, Rony L, Ducellier F, Cronier P, Steiger V, Hubert L. Reconstruction of large diaphyseal bone defect by simplified bone transport over nail technique: A 7-case series. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. OTSR. 2017;103(7):1131–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kocaoglu M, Eralp L, Rashid HU, Sen C, Bilsel K. Reconstruction of segmental bone defects due to chronic osteomyelitis with use of an external fixator and an intramedullary nail. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2006;88(10):2137–2145. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liodakis E, Kenawey M, Krettek C, Ettinger M, Jagodzinski M, Hankemeier S. Segmental transports for posttraumatic lower extremity bone defects: Are femoral bone transports safer than tibial? Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2011;131(2):229–234. doi: 10.1007/s00402-010-1129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu Y, Ma T, Ren C, Li Z, Sun L, Xue H, et al. Treatment of segmental tibial defects by bone transport with circular external fixation and a locking plate. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020;48(4):300060520920407. doi: 10.1177/0300060520920407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oh CW, Song HR, Roh JY, Oh JK, Min WK, Kyung HS, et al. Bone transport over an intramedullary nail for reconstruction of long bone defects in tibia. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2008;128(8):801–808. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marais LC, Ferreira N. Bone transport through an induced membrane in the management of tibial bone defects resulting from chronic osteomyelitis. Strateg. Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2015;10(1):27–33. doi: 10.1007/s11751-015-0221-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meselhy MA, Singer MS, Halawa AM, Hosny GA, Adawy AH, Essawy OM. Gradual fibular transfer by ilizarov external fixator in post-traumatic and post-infection large tibial bone defects. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2018;138(5):653–660. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-2895-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu K, Fu X, Li YM, Wang CG, Li ZJ. A treatment for large defects of the tibia caused by infected nonunion: Ilizarov method with bone segment extension. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2014;183(3):423–428. doi: 10.1007/s11845-013-1032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Polyzois D, Papachristou G, Kotsiopoulos K, Plessas S. Treatment of tibial and femoral bone loss by distraction osteogenesis. Experience in 28 infected and 14 clean cases. Acta Orthop. Scand. Suppl. 1997;275:84–88. doi: 10.1080/17453674.1997.11744753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smrke D, Arnez ZM. Treatment of extensive bone and soft tissue defects of the lower limb by traction and free-flap transfer. Injury. 2000;31(3):153–162. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(99)00253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hutson JJ, Jr, Dayicioglu D, Oeltjen JC, Panthaki ZJ, Armstrong MB. The treatment of gustilo grade IIIB tibia fractures with application of antibiotic spacer, flap, and sequential distraction osteogenesis. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2010;64(5):541–552. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181cf9fb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang Q, Xu YB, Ren C, Li M, Zhang CC, Liu L, et al. Bone transport combined with bone graft and internal fixation versus simple bone transport in the treatment of large bone defects of lower limbs after trauma. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022;23(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s12891-022-05115-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu Y, Yushan M, Liu Z, Liu J, Ma C, Yusufu A. Treatment of diaphyseal forearm defects caused by infection using Ilizarov segmental bone transport technique. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021;22(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-03896-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Banic A, Hertel R. Double vascularized fibulas for reconstruction of large tibial defects. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 1993;9(6):421–428. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hertel R, Pisan M, Jakob RP. Use of the ipsilateral vascularised fibula for tibial reconstruction. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Vol. 1995;77(6):914–919. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.77B6.7593105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khan MZ, Downing ND, Henry AP. Tibial reconstruction by ipsilateral vascularized fibular transfer. Injury. 1996;27(9):651–654. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(96)00080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hsu RW, Wood MB, Sim FH, Chao EY. Free vascularised fibular grafting for reconstruction after tumour resection. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Vol. 1997;79(1):36–42. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B1.0790036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morsi E. Tibial reconstruction using a non-vascularised fibular transfer. Int. Orthop. 2002;26(6):377–380. doi: 10.1007/s00264-002-0378-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chang DW, Weber KL. Use of a vascularized fibula bone flap and intercalary allograft for diaphyseal reconstruction after resection of primary extremity bone sarcomas. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005;116(7):1918–1925. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000189203.38204.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moran SL, Shin AY, Bishop AT. The use of massive bone allograft with intramedullary free fibular flap for limb salvage in a pediatric and adolescent population. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006;118(2):413–419. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000227682.71527.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li J, Wang Z, Guo Z, Chen GJ, Fu J, Pei GX. The use of allograft shell with intramedullary vascularized fibula graft for intercalary reconstruction after diaphyseal resection for lower extremity bony malignancy. J. Surg. Oncol. 2010;102(5):368–374. doi: 10.1002/jso.21620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li J, Wang Z, Pei GX, Guo Z. Biological reconstruction using massive bone allograft with intramedullary vascularized fibular flap after intercalary resection of humeral malignancy. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011;104(3):244–249. doi: 10.1002/jso.21922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schuh R, Panotopoulos J, Puchner SE, Willegger M, Hobusch GM, Windhager R, et al. Vascularised or non-vascularised autologous fibular grafting for the reconstruction of a diaphyseal bone defect after resection of a musculoskeletal tumour. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-b(9):1258–1263. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B9.33230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lê Thua TH, Pham DN, Boeckx W, De Mey A. Vascularized fibular transfer in longstanding and infected large bone defects. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2014;80(1):50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cano-Luís P, Andrés-Cano P, Ricón-Recarey FJ, Giráldez-Sánchez MA. Treatment of posttraumatic bone defects of the forearm with vascularized fibular grafts. Follow up after fourteen years. Injury. 2018;49(Suppl 2):S27–s35. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Errani C, Ceruso M, Donati DM, Manfrini M. Microsurgical reconstruction with vascularized fibula and massive bone allograft for bone tumors. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. Orthop. Traumatol. 2019;29(2):307–311. doi: 10.1007/s00590-018-2360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu T, Ling L, Zhang Q, Liu Y, Guo X. Evaluation of the efficacy of pasteurized autograft and intramedullary vascularized fibular transfer for osteosarcoma of the femoral diaphysis. Orthop. Surg. 2019;11(5):826–834. doi: 10.1111/os.12528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Taha WE, Blachut PA, Meek RN, MAcLeod M. Intramedullary nailing and ipsilateral fibular transfer for the reconstruction of segmental tibial bone defects. Oper. Orthop. Traumatol. 2003;15(2):188–207. doi: 10.1007/s00064-003-1067-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Toros T, Ozaksar K, Sügün TS, Ozerkan F. Reconstruction of humeral diaphyseal non-unions with vascularized fibular graft. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 2012;46(3):149–153. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2012.2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Abudu A, Carter SR, Grimer RJ. The outcome and functional results of diaphyseal endoprostheses after tumour excision. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Vol. 1996;78(4):652–657. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.78B4.0780652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ahlmann ER, Menendez LR. Intercalary endoprosthetic reconstruction for diaphyseal bone tumours. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Vol. 2006;88(11):1487–1491. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B11.18038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aldlyami E, Abudu A, Grimer RJ, Carter SR, Tillman RM. Endoprosthetic replacement of diaphyseal bone defects Long-term results. Int. Orthop. 2005;29(1):25–29. doi: 10.1007/s00264-004-0614-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huang HC, Hu YC, Lun DX, Miao J, Wang F, Yang XG, et al. Outcomes of intercalary prosthetic reconstruction for pathological diaphyseal femoral fractures secondary to metastatic tumors. Orthop. Surg. 2017;9(2):221–228. doi: 10.1111/os.12327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tedesco NS, Van Horn AL, Henshaw RM. Long-term results of intercalary endoprosthetic short segment fixation following extended diaphysectomy. Orthopedics. 2017;40(6):e964–e970. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20170918-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zheng K, Yu XC, Hu YC, Shao ZW, Xu M, Wang BC, et al. Outcome of segmental prosthesis reconstruction for diaphyseal bone tumors: A multi-center retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):638. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5865-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Benevenia J, Kirchner R, Patterson F, Beebe K, Wirtz DC, Rivero S, et al. Outcomes of a modular intercalary endoprosthesis as treatment for segmental defects of the Femur, Tibia, and Humerus. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2016;474(2):539–548. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4588-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Büyükdoğan K, Göker B, Tokgözoğlu M, İnan U, Özkan K, Çolak TS, et al. Preliminary results of a new intercalary modular endoprosthesis for the management of diaphyseal bone metastases. Joint Dis. Relat. Surg. 2021;32(3):713–720. doi: 10.52312/jdrs.2021.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhao J, Yu XC, Xu M, Zheng K, Hu YC, Wang F, et al. Intercalary prosthetic reconstruction for pathologic diaphyseal humeral fractures due to metastatic tumors: Outcomes and improvements. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2018;27(11):2013–2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schileo E, Feltri P, Taddei F, di Settimi M, Di Martino A, Filardo G. A taper-fit junction to improve long bone reconstruction: A parametric In Silico model. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021;124:104790. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2021.104790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hinsche AF, Giannoudis PV, Matthews SE, Smith RM. Spontaneous healing of large femoral cortical bone defects: Does genetic predisposition play a role? Acta Orthop. Belg. 2003;69(5):441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Masquelet AC. Muscle reconstruction in reconstructive surgery: Soft tissue repair and long bone reconstruction. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2003;388(5):344–346. doi: 10.1007/s00423-003-0379-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Beris AE, Lykissas MG, Korompilias AV, Vekris MD, Mitsionis GI, Malizos KN, et al. Vascularized fibula transfer for lower limb reconstruction. Microsurgery. 2011;31(3):205–211. doi: 10.1002/micr.20841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Capanna R, Bufalini C, Campanacci M. A new technique for reconstructions of large metadiaphiseal bone defects. 1993.

- 96.Errani C, Alfaro PA, Ponz V, Colangeli M, Donati DM, Manfrini M. Does the addition of a vascularized fibula improve the results of a massive bone allograft alone for intercalary femur reconstruction of malignant bone Tumors in children? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2021;479(6):1296–1308. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Feltri P, Solaro L, Errani C, Schiavon G, Candrian C, Filardo G. Vascularized fibular grafts for the treatment of long bone defects: Pros and cons. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 98.Ilizarov GA, Ledyaev VI. The replacement of long tubular bone defects by lengthening distraction osteotomy of one of the fragments. 1969. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1992;280:7–10. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tsuchiya H, Tomita K, Shinokawa Y, Minematsu K, Katsuo S, Taki J. The Ilizarov method in the management of giant-cell tumours of the proximal tibia. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Vol. 1996;78(2):264–269. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.78B2.0780264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Aktuglu K, Erol K, Vahabi A. Ilizarov bone transport and treatment of critical-sized tibial bone defects: A narrative review. J. Orthop. Traumatol. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Orthop. Traumatol. 2019;20(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s10195-019-0527-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Raschke MJ, Mann JW, Oedekoven G, Claudi BF. Segmental transport after unreamed intramedullary nailing. Preliminary report of a "Monorail" system. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1992;282:233–240. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199209000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Paley D, Herzenberg JE, Paremain G, Bhave A. Femoral lengthening over an intramedullary nail. A matched-case comparison with Ilizarov femoral lengthening. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1997;79(10):1464–1480. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199710000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Simpson A, Cole AS, Kenwright J. Leg lengthening over an intramedullary nail. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Vol. 1999;81(6):1041–1045. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B6.0811041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fuchs B, Ossendorf C, Leerapun T, Sim FH. Intercalary segmental reconstruction after bone tumor resection. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Assoc. Surg. Oncol. 2008;34(12):1271–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zekry KM, Yamamoto N, Hayashi K, Takeuchi A, Alkhooly AZA, Abd-Elfattah AS, et al. Reconstruction of intercalary bone defect after resection of malignant bone tumor. J. Orthop. Surg. (Hong Kong) 2019;27(1):2309499019832970. doi: 10.1177/2309499019832970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]