Abstract

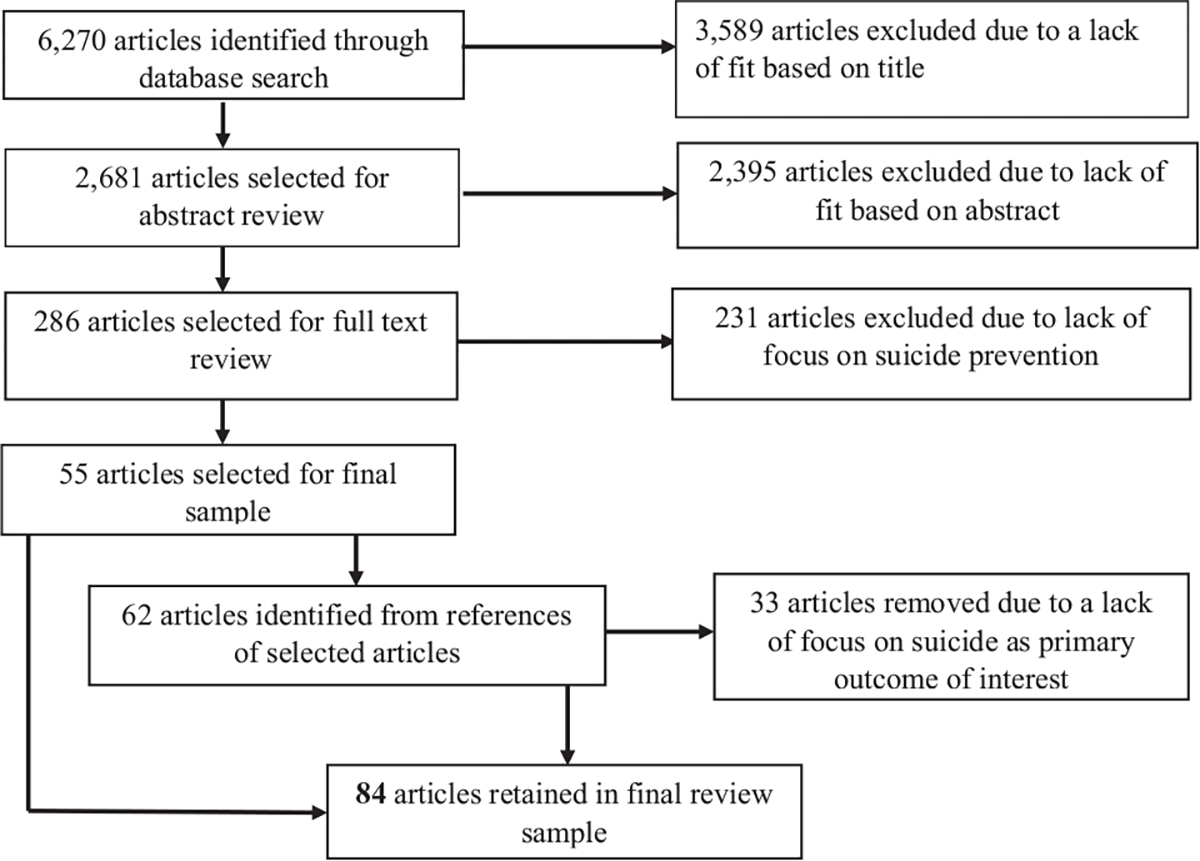

Peers of individuals at risk for suicide may be able to play important roles in suicide prevention. The aim of the current study is to conduct a scoping review to characterize the breadth of peer-delivered suicide prevention services and their outcomes to inform future service delivery and research. Articles were selected based on search terms related to peers, suicide, or crisis. After reviews of identified abstracts (N = 2681), selected full-text articles (N = 286), and additional references (N = 62), a total of 84 articles were retained for the final review sample. Types of suicide prevention services delivered by peers included being a gatekeeper, on-demand crisis support, crisis support in acute care settings, and crisis or relapse prevention. Peer relationships employed in suicide prevention services included fellow laypersons; members of the same sociodemographic subgroup (e.g., racial minority), workplace, or institution (e.g., university, correctional facility); and the shared experience of having a mental condition. The majority of published studies were program descriptions or uncontrolled trials, with only three of 84 articles qualifying as randomized controlled trials. Despite a lack of methodological rigor in identified studies, peer support interventions for suicide prevention have been implemented utilizing a diverse range of peer provider types and functions. New and existing peer-delivered suicide prevention services should incorporate more rigorous evaluation methods regarding acceptability and effectiveness.

Keywords: Peer group, Suicide, Crisis

Introduction

To address steadily increasing suicide deaths, the U.S. Surgeon General’s national suicide prevention strategy (2012) and other guidelines have included recommendations that peer support be integrated into the care of individuals at high risk for suicide (Hedegaard et al., 2020; National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2019; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2012).

Peer support occurs on a continuum according to the degree to which support is mutual and loosely structured (e.g., mutual support group; Moos, 2003; Pistrang et al., 2008; Roberts et al., 1999) versus unidirectional and structured (e.g., peer support specialist delivering a curriculum; Davidson et al., 2006). Mutual peer support groups have a long tradition of providing support to individuals in recovery from mental health crises, and historically, these groups grew out of a desire for alternatives to psychiatric hospitalization (Galanter, 1988; Kryrouz et al., 2002). Within mutual peer support groups, receiving emotional support, sharing experiences, and building connections outside of meetings are key components of effective support. More recently, peer support has been increasingly integrated into community mental health treatment services with the development and growth of the peer support specialist (or peer specialist) workforce. Peer specialists are individuals trained to utilize their lived experiences of mental health challenges and recovery to support others. Peer specialists report that their work often includes discussions of suicide, though there are not well-established professional standards among peer specialists for suicide prevention training (Scott et al., 2011).

According to Valenstein et al. (2016), peer support services can be characterized by the degree of healthcare system integration, relationship, and mental health status of the peers; content and focus of the interactions (e.g., supportive, educational, case management); mode of interaction (e.g., in-person, telephone); and duration and frequency of interactions. Peer support has the potential to address suicide risk through multiple mechanisms. Peers providing emotional support and sharing their experience of recovery could increase perceived connectedness and reduce hopelessness among support recipients, two key factors for preventing suicidal ideation according to the interpersonal theory of suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010). Peer support may also reduce suicide risk by decreasing stigma, increasing orientation to personal growth and recovery, and encouraging active care engagement (Salvatore, 2010; Holmes et al., 2013; Suicide Prevention Resource Center, 2018). Despite guidelines recommending greater incorporation of peers into suicide prevention, the recent growth of peer services in community mental health care, and a theoretical rationale for peer support in suicide prevention, there has been little synthesis of the evidence on how peer support has been applied to suicide prevention.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found mixed evidence for the effectiveness of peer support for improving mental health outcomes. A review of mutual support groups found benefits (e.g., treatment adherence, symptom burden) across a range of outcomes in seven of 12 studies focusing on conditions such as depression/anxiety, bereavement, and serious mental illness (Pistrang et al., 2008). Two meta-analyses focusing on depression care found that peer support was effective for improving depression symptoms compared with no additional treatment and similarly effective as therapist-delivered treatments (Bryan & Arkowitz, 2015; Pfeiffer et al., 2011;). In contrast, a meta-analysis of peer support for individuals with serious mental illness found insufficient evidence for symptom reduction or reducing hospitalizations, although some evidence was found for improving hope (Beck et al., 2006; Lloyd-Evans et al., 2014).

A review of relevant literature demonstrates that there have not been any systematic evaluations of peer support on suicide outcomes and there are not enough high-quality randomized controlled trials on this topic to perform a meta-analysis. We therefore sought to describe the breadth of suicide prevention-focused peer support interventions to characterize the current state of the field to inform future research and program development. To this end, we conducted a systematic scoping review, which differs from a systematic literature review in that systematic literature reviews “guide clinical decision-making, the delivery of care, and policy development” with respect to a specific practice whereas scoping reviews map the available evidence to identify important concepts and characteristics and identify gaps in the literature (Munn et al., 2018). This scoping review was designed to address the following questions: (1) In what ways have peers been involved in the delivery of suicide prevention services?; (2) What is the evidence regarding the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of peers providing suicide prevention services?; and (3) What are the implications of the current evidence base for implementation of peer-based suicide prevention services and for future research?

Methods

To identify candidate articles, the authors developed search terms with a shared focus on peers and suicide prevention based on terms used in previous literature reviews on these topics. Articles were selected based on the intersection of search terms related to “peers,” “suicide,” and “crisis.” Search terms used to identify articles related to peer-based interventions (“peer”) were based on a combination of search terms used in prior peer support meta-analyses (Bryan & Arkowitz, 2015; Chien et al., 2013; Fuhr, et al., 2014; O’Connor & Delaney, 2007; Pfeiffer et al., 2011) and included “peer,” “peer group,” “self-help group,” “support group,” “mutual,” “peer support,” “paraprofessional,” “social support,” “network,” “advice,” “counsel,” and associated combinations. Search terms for “suicide” were based on those included in a recent systematic review of suicide prevention (Zalsman et al., 2016) which included “suicide,” as well as the subheadings “suicide, attempted,” and “prevention and control.” Terms representing “crisis” were also included because this term has been used in the literature to encompass suicidal periods of intense distress (Dalgin et al., 2011; Gilat et al., 2011; Greenfield et al., 2008; Migdole et al., 2011), the specific terms used were “crisis,” “crisis intervention,” crisis services,” “emergency services, psychiatric,” “crisis intervention services,” “crisis intervention/methods,” “crisis intervention/organization and administration,” and “hospitals, psychiatric.”

Searches were conducted during July of 2019 of PubMed, PsychINFO, and Web of Science and included materials from all available years. Searches were limited to English-language articles and book chapters. All articles that included the search terms of interest were included in our review without further restriction due to the paucity of literature in this area. Although the role of peer support among children and adolescents is important, we did not feel we could adequately address this additional body of literature within the limits of a single manuscript and therefore limited our review to studies on adult populations. The initial literature search resulted in 6270 references which contained combinations of terms included in the “peer”, “suicide”, and/or the “crisis” search terms. A review of the titles of these references was conducted by one of the authors (NB) and resulted in excluding 3589 articles as poor fits to our research questions. Abstracts for the remaining 2681 articles were screened by three authors (NB, JG, and JJ) using a structured review based on a series of yes/no questions for each reference.

The five inclusion/exclusion questions used to screen each article were “Does this article have a mental health focus?”, “Was the population of focus adult (18+)?”, “Did the article focus on an intervention?”, “Did the article focus on peer-based service delivery?”, and “Was the focus of the intervention on suicide prevention or crisis management?”. Only articles that met criteria based on these questions were further reviewed. We used a broad definition of “peer” for our peer-based service criteria, including members of the general public (or “laypersons”), those who share membership in an organization or community subgroup, and peer support providers with lived experience of mental health challenges. We chose this broad definition in keeping with the goal of identifying all relevant models of peer support for suicide prevention, therefore preferring to err on the side of over-inclusion to avoid excluding potentially relevant studies.

This initial screening eliminated 2395 references as poor fits to the main questions of interest. Full text of the remaining 286 references was doubly reviewed by three of the authors (NB, PP, and JC), resulting in 55 initial manuscripts meeting eligibility criteria. Abstracts for each of the references cited in each of these manuscripts were screened using the same five inclusion/exclusion questions used in the initial search, resulting in the identification of 62 additional article abstracts. Upon review of the full text of these 62 articles, 29 were eligible for inclusion and 33 did not meet study criteria, resulting in a final sample of 84 products. This screening and approval process mirrors suggested standard methods for conducting a scoping review (Peters et al., 2015). This review process is represented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Scoping review search flow diagram

Each included study was coded in terms of its intervention characteristics and evaluation of the intervention. Each intervention was classified based on the function of the peer interactions (e.g., identify and offer support to persons at risk for suicide), the basis of the peer relationship (member of the same organization, lived experience of mental health challenges), and the modality of peer interactions (in-person individual, in-person group, telephone, online message boards). These dimensions and categorizations were based on a categorization scheme described by Valenstein et al. (2016) to conceptualize variations in peer-based intervention characteristics and support the tracking of such variations in specific areas likely to impact the delivery and experience of peer-based care. Other intervention characteristics included in the Valenstein scheme, such as the level of integration with the health system or the mental health status of the peer, were incorporated into the function and relationship categories. This classification scheme was then refined in an iterative and inductive process to provide an organizational structure to summarize the results. We also evaluated the quality of research methods within the studies included in our review sample based on guidelines from the United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF, 1989). To identify potential gaps in research, we also categorized studies according to the degree to which functions represented components of the Comprehensive Approach to Suicide Prevention (CASP) framework. The CASP framework includes eight core strategies that describe different approaches to suicide prevention and one focus area for postvention (Suicide Prevention Resource Center, 2018).

Several additional articles were identified which did not strictly match our search parameters but provided valuable context for the scoping review. These are briefly discussed in the Results section, albeit with less detail than articles meeting our search parameters.

Results

Each of the 84 included studies was categorized as providing one of four primary functions: gatekeeper, on-demand crisis support, crisis support in an acute care setting, and crisis/relapse prevention. Within these categories, studies were further grouped by peer relationship. The four types of peer relationships used to group studies were as follows: members of the general public (e.g., volunteers), members of the same sub-community or sociodemographic subgroup (e.g., an ethnic subgroup), members of the same organization or institution (e.g., workplace, school, or correctional facility), and individuals with a lived experience of a mental health condition. This approach allowed for the inclusion of studies in which the peer support intervention was delivered by persons with variable levels of training and formalization of their peer support role from friend or neighbor to authority figures such as police officers to trained peer support providers (persons who use their lived experience of recovery from mental illness, plus skills learned in formal training, to deliver services in behavioral health settings (SAMHSA, 2018).

Across the included studies, 42 distinct peer-based suicide prevention interventions were identified and categorized based on their intervention type and peer relationship status. Across these interventions, four targeted gatekeeper/general public delivery, five interventions targeted gatekeeper/same subgroup delivery, seven interventions targeted gatekeeper/same organization, 12 interventions delivered on-demand crisis support to the general public, one intervention provided on-demand crisis support within a subgroup, seven interventions provided on-demand crisis support within organizations, three interventions provided on-demand crisis support to persons with similar life experiences, two interventions provided acute setting support to persons with shared mental health experiences, two interventions provided crisis/relapse prevention support to persons in the same subgroup, and three interventions provided crisis/relapse prevention support to persons with shared mental health experiences. Several interventions (e.g., Samaritans) had multiple studies which described their core program or evaluated their clinical impact. Three interventions were included in multiple combinations of intervention type and peer relationship (QPR, IOP, Samaritans) given their use in different clinical settings. Summary information on studies included in this review is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Summary of peer suicide intervention types, characteristics, key findings, and representative articles

| Intervention type | Peer relationship status | Function | Modalities | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Gatekeeper1–25 | General public1–9 (Interventions: Mental Health First Aid3,6, QPR2,8,9, ASIST7,9, R U OK?5, OPSI Europe1,4) | Screen for suicidal risk; support follow-up with formal mental health care | In-person; text message | Training results in increased comfort with asking about and responding to suicidal risk in others; no evidence of effect on suicidal behaviors |

| Same subgroup10–14 (Interventions: QPR10, NOCOMIT-J11, Shoalhaven community gatekeeper training12, SPAD13, Commissioned welfare volunteers14) | Identify persons at risk for suicide, offer support, and encourage follow-up with formal mental health care | In-person | Reduced suicide rates in some high-risk subgroups; training valuable in subgroups with restricted access to formal mental health care | |

| Same organization15–25 (Interventions: QPR16,19,23,24, ALIVE@Purdue17, Peer Hero18, DORA20, Niigata City suicide prevention training21, Campus Connect22, ASIST25) | Screen for suicidal risk; support follow-up with formal mental health care | In-person | Training resulted in increased comfort in identifying and responding to suicidal risk, less suicidal ideation; skills learned in training persist over time | |

| Shared lived MH experience | – | – | No articles identified | |

| On-demand crisis support26–73 | General public26–55 (Interventions: Crisis Text Line26, Crisis Call Center27, Samaritans28,31–33,37,41,42,44–51, SANELINE29, Lifeline Australia30,54, SAHAR34,49,53, Montreal suicide line correspondence35, WIRE36, ERAN38–40, Suicide-Action Montreal and Carrefour Intervention Suicide centers43, American volunteer suicide prevention call centers52, Israeli telephone emergency services55) | Provide short-term emergency support; triage and encourage formal mental health follow-up as needed | Phone, online message boards, in-person | Mixed results with regard to impact on community suicide rates, support offered mirrors many aspects of formal mental health care |

| Same subgroup (Interventions: LGBT Community Crisis Training56) | Provide short-term emergency support; enhance advocacy for mental health needs of subgroup | Phone; in-person | Reduced rates of suicide-related hospitalization in vulnerable group; enhanced support for persons less likely to seek formal mental health care | |

| Same organization57–67 (Interventions: POPPA57–58, CISM59–60,66, BOL61, Together for Life62, COP-2-COP63, RPS64, Ukrainian Army gatekeeper training67) |

Screen for suicidal risk; provide short-term emergency support; triage; and encourage formal mental health follow-up as needed | Phone, in-person | Reduced suicide rates within organizations participating in support programs; increased engagement in mental health by members | |

| Shared lived MH experience68–73 (Interventions: Samaritans68–73, IOP68, Suicide Prevention Groups69) |

Screen for suicidal risk; provider short-term emergency support; encourage formal mental health follow-up as needed | In-person | Well-received and feasible to deliver, limited available evidence to estimate impact of interventions | |

| Acute setting crisis support74–75 | General public | – | – | No articles identified |

| Same subgroup | – | – | No articles identified | |

| Same organization | – | – | No articles identified | |

| Shared lived MH experience74–75 (Interventions: IOP74, Inmate Observation Aides75) |

Monitor suicidal behavior; offer emotional support; notify formal mental health as needed for higher-level intervention | In-person | Prisons: presence of peer support reduced time prisoners required active monitoring for suicide | |

| Crisis/relapse prevention76–84 | General public | – | – | No articles identified |

| Same subgroup76–77(Friend Connector76, TSC77) | Provide emotional support; screen for suicidal risk; encourage formal mental health follow-up as needed | Phone, in-person | Support effective at reducing hospitalizations due to suicidality; hypothesized to be due to increasing social connectedness and belonging | |

| Same organization | – | – | No articles identified | |

| Shared lived MH experience78–84 (Interventions: in-person group therapy for suicide prevention78, PREVAIL79, online message boards80–84) | Provide mutual emotional support and problem solving to deal with emotional crises | In-person; online support groups | Forums may allow for access to suicide prevention by persons who would not receive support through formal mental health channels; reduced suicidality in mutual in-person support groups; peer-delivered support well received | |

Note: In addition to the manuscript’s reference list, representative articles for each type of peer intervention identified in this table have a superscript that corresponds to the cited references which can be found more easily in the Supporting Information.

Abbreviations: ASIST, Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training; BOL, Badge of Life Psychological Survival for Police Officers Program; CISM, Critical Incident Stress Management; DORA, Depression OutReach Alliance; ERAN, Israeli Association for Emotional First Aid; IOP, Inmate Observer Program; POPPA, Police Organization Providing Peer Assistance; PREVAIL, Peers for Valued Living; QPR, Question, Persuade, Refer; RPS, Reciprocal Peer Support; SAHAR, Support and Listening on the Net; TSC, The Senior Connection; WIRE, Women’s Information Referral and Exchange

Gatekeeper

Gatekeeper training interventions capitalize on existing social networks by providing brief training to persons who are not mental health providers to prepare them for situations in which they encounter someone experiencing a suicidal crisis. The training may include suicide risk identification, brief crisis intervention, and referral to advanced crisis support services.

Several gatekeeper programs, such as Mental Health First Aid (Dumesnil and Verger, 2009; Svensson & Hansson, 2014), Question Persuade Refer (QPR; Cross et al., 2007), and Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST; Gould et al., 2013), are made open to the general public as part of public health campaigns analogous to training laypersons in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Duration of training for these programs ranges from four to 16 hours. Studies of these programs show improved trainee skills and comfort in assisting suicidal individuals following training, though the effects on suicidal behaviors have not been established (Cross et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2011; Svensson & Hansson, 2014). A variant of the gatekeeper model that provides minimal training is the public health campaign conducted in Australia called “R U OK?” (Mok et al., 2016). This program publicized a national “R U OK?” day, in which individuals were encouraged to connect with those around them who might be struggling with mental health or suicide. Among 1313 community survey respondents, 55% were aware of the campaign and among those aware of the campaign 19% participated by asking others if they were ok. Another approach to enhancing suicide prevention directed at the general public is to offer gatekeeper training to public officials. Of note, there is a large-scale, evidence-based program developed to increase suicide prevention in Europe which has a large gatekeeper component (Optimizing Suicide Prevention Programs and their Implementation in Europe, or OSPI Europe; Arensman et al., 2016; Hegerl et al., 2009) although evidence on its effectiveness has not been reported.

Some gatekeeper programs have focused on particular community subgroups at increased risk for suicide, such as a Japanese Americans in the United States (Teo et al., 2016), rural communities in Japan (Ono et al., 2008), elderly persons in Japan (Noguchi et al., 2014), African American college students (Bridges et al., 2018), and a Shoalhaven Aboriginal community in Australia (Capp et al., 2001). Teo et al. (2016) demonstrated that a one-time, brief gatekeeper training was effective in preparing lay members of a high-risk minority population to provide suicide screening, support, and referral to services. Ono et al. (2008) provided multi-level suicide prevention training (e.g., outreach education to local leadership, focused gatekeeper training to community members) to members of a rural Japanese community and found that the intervention was effective in reducing suicide rates in male and elderly members of the community (two subgroups at increased risk for suicide). Capp et al. (2001), in a study of a gatekeeper training among Aboriginal persons in Australia, found that a one-day gatekeeper training was well-received and resulted in increased willingness to intervene, confidence in how to intervene, and support for engagement in formal suicide prevention services. Bridges et al. (2018) found than an online gatekeeper training course (PRECEDE-PROCEDE) was effective at increasing skills, sympathy, and comfort in supporting peers experiencing depression and increased suicidal risk among African American college students. Noguchi et al. (2014) found that home-based visits with volunteers were associated with decreased suicidal ideation in older adults in Japan, with women benefitting more than men.

Although the majority of gatekeeper evaluations focus on the effects of the gatekeeper training on gatekeeper skill acquisition rather than the outcomes of skill application (Arensman et al., 2016; Capp et al., 2001; Cross et al., 2007; Cross et al., 2010; Matthieu et al., 2008; Taub et al., 2013), there is some evidence that gatekeeper trainings in rural areas focusing on high-risk groups may reduce suicide risk (Ono et al., 2008). Across these studies, gatekeeper training was seen as an essential aspect of suicide prevention based on limited access or engagement in more formal mental health and suicide prevention services, with gatekeeper support framed within shared membership in the same communities.

The gatekeeper model has also been applied to address suicide risk within organizations such as colleges (Cross et al., 2010; Funkhouser et al., 2017; Katsumata et al., 2017; Rallis et al., 2018; Sari et al., 2008; Taub et al., 2013; Thombs et al., 2015; Tompkins & Witt, 2009; Tsong et al., 2019) or military groups (Smith-Osborne et al., 2017). Brief gatekeeper training provided to college residence advisors (McLean & Swanbrow Becker, 2018; Sari et al., 2008) and students (Funkhouser et al., 2017; Katsumata et al., 2017; Rallis et al., 2018; Tsong et al., 2019) has been shown to be effective in increasing awareness of suicide risk factors and skills for referring suicidal students for support (Taub et al., 2013), although one study failed to find evidence of effective skill acquisition (McLean & Swanbrow Becker, 2018). The effects of these trainings appear to have some sustainability, with gatekeeper skill competency persisting across university semesters (Thombs et al., 2015). Gatekeeper training provided within Army reserve platoons in the form of ASIST training was found to be associated with decreased suicide attempts and suicidal ideation (Smith-Osborne et al., 2017). Gatekeeper interventions appear be a highly feasible approach to suicide prevention, with short-term, low-intensity training resulting in improved skills and response confidence. There is limited available information on the acceptability of gatekeeper-delivered suicide prevention services to persons at risk for suicide, as the majority of studies focus on skill acquisition.

On-Demand Crisis Support

Suicide prevention interventions delivered via on-demand crisis support are highly accessible and designed to provide support to individuals in crisis through direct counseling and/or referral to additional community resources or acute care. Compared to gatekeepers, persons providing on-demand crisis support generally have more extensive training and supervision, more advanced suicide prevention skills, and a greater knowledge of available resources. The most prominent models of on-demand crisis support are crisis hotlines, online services, drop-in centers, and immediate peer crisis support within the workplace or institutions.

Several organizations offer crisis support services to the general public delivered by nonprofessional laypersons. Crisis hotlines are often staffed by nonclinical, lay volunteers, who receive phone calls or messages posted to hotline webpages. The amount of training received by crisis hotline volunteers varies across organizations, with some requiring approximately 35 hours of web-based training (Crisis Call Center, 2018), others requiring 70+ h of training including structured gatekeeper training (Crisis Call Center, 2018; Gould et al., 2013), and others providing in-person training (The Samaritans, 2018). Representative organizations that provide these types of services are the SANELINE and Samaritans in England and Europe, Lifeline in Australia, and ERAN and SAHAR in Israel (Armson, 1997a; Armson, 1997b; Bale, 2001; Barak, 2007; Brunet et al., 1994; Coman et al., 2001; Coveney et al., 2012; Fakhoury, 2002; Gilat & Shahar, 2007; Gilat & Shahar, 2009; Gilat et al., 2011; Gilat et al., 2012; Greenbury, 1999; Hall & Schlosar, 1995; Holding, 1974; Jennings et al., 1978; Keir, 2000; Lester, 2005; Lester, 2009; Mishara & Daigle, 1997; Pollock et al., 2010; Watson et al., 2006;).

On-demand crisis support services have been generalized from primary phone-based support to also include online support (e.g., via responses to online message boards, real-time chat) and in-person, drop-in support centers. In part due to the anonymous and time-limited use of these services by consumers, there is limited research on the effectiveness of this model. Evaluations of the impact of on-demand crisis support services on community suicide rates have been mixed. Assessments of suicide rates in Great Britain, comparing pre- and post-implementation periods for the Samaritans call service, have found that suicide rates decreased after the launch of this service (Bagley, 1968), but this decrease may be reflective of national suicide trends rather than the impact of the Samaritans service per se (Barraclough et al., 1977). Other evaluations have found no effect of the Samaritans services on suicide rates (Jennings et al., 1978; Lester, 2005). Conversely, an evaluation of a suicide prevention hotline in the United States found reduced suicide rates in younger females (Miller et al., 1984). Evaluations of techniques utilized by volunteers and their perceived usefulness by persons seeking support (Barak & Bloch, 2006; Barber et al., 2004; Gilat et al., 1998; Pollock et al., 2010) have found that the conversations provided by volunteers offer many of the same characteristics as sessions conducted by professionally trained therapists, that utilizers find these conversations helpful for managing emotional difficulties, that relationship difficulties are the most common conversation topic, and that crisis lines support community mental health both by providing support to those with chronic mental health symptoms as well as those with more acute stressors.

The only instance of on-demand crisis support involving members of a demographic subgroup we identified in our review was a study that trained lay members of the LGBT community to provide support via a crisis phone line and in-person within community emergency rooms (Enright & Parsons, 1976). The authors reported a reduction in the number of inpatient admissions for suicidal risk among members of the LGBT community and increased collaboration between mental health providers and the LGBT community in raising awareness about suicide risk, self-care, and mental health treatment options (Enright & Parsons, 1976).

On-demand crisis support services have also been developed in several institutional settings to address the mental health needs of workers at increased risk for suicide and emotional crisis given high levels of exposure to traumatic workplace events such as police (Castellano, 2012; Dowling et al., 2005; Dowling et al., 2006; Levenson, 2007; Levenson & Dwyer, 2003; Levenson et al., 2010; Mishara & Martin, 2012; Ramchand et al., 2019; Ussery & Waters, 2006), firefighters (Finney et al., 2015), and military officers (Rozanov et al., 2002). Crisis support services are delivered by peers due to a tendency for workers in these settings to avoid formal mental health services because of concerns that they would be viewed as unable to perform their job duties. Interventions implemented in these settings incorporate aspects of gatekeeper training and on-demand crisis support, allowing for screening and immediate response via in-person and telephone support sessions. In some cases, gatekeeper training is provided to all organization members and coupled with an available crisis line for employees to call and receive additional support, often by a peer. Evidence for the effectiveness of workplace interventions is limited; however, direct comparisons of pre- to post-program implementation found that such programs were associated with decreased suicide rates in Montreal police departments (Mishara & Martin, 2012) and the Ukrainian military service (Rozanov et al., 2002).

Peers with lived experience of mental health conditions have been incorporated into suicide prevention efforts within correctional facilities through the use of models such as the Samaritans, Inmate Observer Programs, and Suicide Prevention Groups (Barker et al., 2014; Biggar & Neal, 1996; Daigle et al., 2007; Dhaliwal & Harrower, 2009; Hall & Gabor, 2004; Perrin & Blagden, 2014). Similar to workplace models, prisoners are trained to support other prisoners experiencing a suicidal crisis on an as-needed basis. Limited available evidence suggests these programs are well-received by prisoners and professional staff, but perhaps less so by correctional officers (Hall & Gabor, 2004), and that prisoners can provide meaningful support and facilitate personal growth (Dhaliwal & Harrower, 2009; Perrin & Blagden, 2014).

Across the studies reviewed, on-demand crisis support appears to have a high level of feasibility, given the ability to train a broad range of volunteer support persons to deliver support across a variety of communication channels and a high level of user acceptability, based on the number of persons at increased suicidal risk who use on-demand crisis support services.

Crisis Support in Acute Care Settings

Suicide prevention delivered in acute care settings is characterized by the provision of suicide-focused support services to individuals who are receiving acute care, such as within hospitals and emergency departments. These services typically focus less on triage and referral and more on assisting individuals in their recovery from the suicidal crisis, navigating acute care experiences, and maintaining immediate safety (Junker et al., 2005; Rakis & Monroe, 1989).

We did not identify any studies of acute care-based crisis support provided by members of the general public, likely due to the need for more advanced clinical training needed to offer support to persons at elevated risk for suicide and the more formal institutional settings in which acute care is typically provided. We similarly did not identify any studies of acute care-based peer support targeting members of the same subgroup or same organization.

There is some limited literature related to the delivery of acute care peer-based crisis support delivered within institutions by persons with lived experiences relevant to the crisis experience (Junker et al., 2005; Rakis & Monroe, 1989). The primary setting in which this support has been documented is within correctional facilities, with prisoners functioning as eyes-on monitors for other prisoners who are under direct observation following the identification of acute suicide risk via the use of interventions such as Inmate Observer Programs. Initial results suggest that this use of peers may have promise in reducing the length of acute suicide risk, with reductions in the average length of time that prisoners needed to be kept on emergency watch (Junker et al., 2005). Such reductions in the length of time that prisoners met emergency, eyes-on suicide risk criteria were found in the overall prisoner population as well as subpopulations which traditionally experience elevated suicide risk (e.g., psychotic disorders; Junker et al., 2005). The available literature on crisis support in acute care settings leaves questions about the acceptability and feasibility of this approach to for at-risk individuals.

Crisis and Relapse Prevention

Peer-delivered interventions have also been designed to provide support to individuals who are not currently experiencing a suicidal crisis but who may be at elevated risk for suicide during future crises (De Man & Labrèche-Gauthier, 1991; Eichenberg & Schott, 2017; Klein et al., 1998; Miller & Gergen, 1998; Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2016; Pfeiffer et al., 2018; Rodham et al., 2007; Van Orden et al., 2013; Whitlock et al., 2006). Two studies were identified which focused on the development of interventions designed to support relapse prevention. Klein et al. (1998) describe an intervention which provides enhanced intensive case management to dual diagnosed persons with substance use and chronic mental health conditions (the “Friend Connector” program), with the goal of reducing inpatient psychiatric care use by providing increased social support and connectedness. The intervention was found to be effective in reducing hospitalization rates (with some hospitalizations explicitly linked to suicidal ideation), increasing physical and emotional well-being, and overall quality of life (Klein et al., 1998). In another study, developed to address the role of social disconnectedness as a risk factor for suicidality, Van Orden et al. (2013) describe an outreach intervention to contact older primary care patients who endorse loneliness and offer them support from a peer over a 2-year period (“The Senior Connection”). The authors hypothesize that the provision of peer support will result in a reduction in suicide risk by increasing feelings of belonging and reducing perceived burden, both of which are identified suicide risk factors (Van Orden et al., 2013).

A handful of studies describe crisis prevention services developed to allow persons with shared experiences of mental health conditions to support one another in managing suicidal risk. De Man and Labrèche-Gauthier (1991) describe a 12-week, group-based intervention for persons in Montreal with first-time suicidal ideation that focused on problem-solving and emotional coping skills development. The group was found to be effective in promoting self-esteem and stress management, as well as reducing levels of suicidal ideation relative to their pre-group levels (De Man & Labrèche-Gauthier, 1991). Pfeiffer et al. (2018) describe an intervention (PREVAIL) delivered by trained peers which provided support targeting suicide risk to patients discharged from inpatient psychiatric care during a 12-week period following discharge. Patients reported positive experiences in working with peers and the perspective that peers were effective in providing support and advice within discussions on suicide (Pfeiffer et al., 2018).

Another venue for the provision of mutual crisis support is online support groups. Online mutual support groups are an attractive option for many persons experiencing suicidal risk, given the ability to remain anonymous, the freedom to interact with supports as often as desired, and the ability to receive responses more quickly than through more traditional mental health channels. Such online support often takes the form of mutual support within specialty internet chat rooms, where users can post messages related to their stressors and thoughts of self-harm which can be responded to by other forum users. Unfortunately, the freedom that such a forum allows has led to the development of “pro-suicide” groups which advocate for users to act upon suicidal urges including discussion of suicide methods (Eichenberg & Schott, 2017; Miller & Gergen, 1998; Whitlock et al., 2006). The limited evaluation of online suicide-focused mutual support groups finds that participants view the group as a forum to discuss feelings that they would otherwise not process with others and that some participants may inadvertently normalize maladaptive coping strategies (Eichenberg & Schott, 2017; Rodham et al., 2007), but that other participants utilize therapeutic techniques that mirror those used in more formal mental health settings to effect change (De Man & Labrèche-Gauthier, 1991; Whitlock et al., 2006). None of the studies of online mutual support groups identified by our search included evaluations of suicide-related symptoms or outcomes related to participation in online mutual support groups.

No studies were identified which discussed crisis and relapse prevention interventions targeting members of the general public or within organizations. Taken together, the literature on crisis and relapse prevention suggests that these interventions are well-received and are a feasible approach to enhancing available services, although it may be beneficial to have some external monitoring of conversations to reduce the promotion of pro-suicide content.

Other Peer-Delivered Interventions Which May Address Suicide But Are Not Designed with Suicide As a Primary Focus

In the course of conducting this review, we identified additional articles in which peers played important roles in crisis support but not in the specific context of suicide prevention. Many of these interventions had the goal of providing a peer-based alternative to inpatient psychiatric care (e.g., peer respites; Bouchery et al., 2018; Doughty & Tse, 2011; Dumont & Jones, 2002; Greenfield et al., 2008; Lyons et al., 1996; Ostrow & Croft, 2015; consumer-run mental health organizations (Nelson et al., 2006; Nelson et al., 2007; Rosen & O’Connell, 2013), providing community-based crisis support delivered by peer providers (Emotions Anonymous, 2003), creating a forum in which peers could provide emotional support to one another during times of crisis (Scanlan et al., 2017), facilitating a smoother transition into inpatient care (e.g., embedding a peer representative as a patient advocate within the emergency room; Migdole et al., 2011), or providing support in the period following discharge from inpatient psychiatric care (Chinman et al., 2001; Johnson et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2005; Milton et al., 2017; O’Connell et al., 2018; Pfeiffer et al., 2017; Scanlan et al., 2017; Simpson et al., 2014; Sledge et al., 2011). Although suicide prevention was not their stated goal, we mention them briefly because they may represent useful models for addressing suicide risk in addition to other acute stressors and psychiatric conditions.

Research Quality of Studies

Three of the products (3.6%) contained in this review achieved the highest possible rating of research quality (randomized control trial, Level I) using the standards as proposed by the USPSTF (1989), demonstrating the need for more rigorous evaluation of the impact of these interventions on suicide-related outcomes. Considered across the recommended levels proposed by the USPSTF, only two studies (2.4%) were determined to be at the level of well-controlled trials without randomization (Level II-1); 22 studies (26.2%) were rated at the level of well-designed cohort or case-controlled analytic studies (Level II-2); 31 (37.0%) were determined to be equivalent to a multiple time series design (Level II-3), and the remaining 26 (31%) were at the lowest level, equivalent to expert opinion (Level III).

Utilization of CASP Framework Approaches

Forty-two unique interventions were identified by our scoping review. These interventions were characterized according to the CASP framework based on the main suicide prevention strategies promoted within each intervention. Across these interventions, the most frequent intervention approaches in descending order were (interventions could include more than one CASP approach): respond effectively to individuals in crisis (n = 31), increase help-seeking (n = 28), identify and assist persons at risk (n = 21), promoting social connectedness (n = 15), enhancing live skills and resilience (n = 7), ensure access to effective mental health/suicide care and treatment (n = 1), and support safe transitions/create organizational linkages (n = 1). We identified no peer-based interventions that focused specifically on access to lethal means or postvention.

Conclusions and Implications for Research and Practice

Intervention Classification

This scoping review revealed peers have been integrated into suicide prevention activities across highly diverse settings and roles. By mapping the available literature into four primary functions (gatekeeper, on-demand crisis support, crisis support in acute care settings, crisis/relapse prevention), four relationship types (general public, demographic subgroup, member of same institution, shared lived experience), and three modalities (e.g., in-person, phone, online), we have provided a framework to facilitate synthesis of findings within groups of similar intervention approaches, comparison across groups, and identification of research gaps. Additional parameters identified by Davidson et al. (2006) and Valenstein et al. (2016), such as the degree of mutuality and intervention content focus, were often not sufficiently described to serve as a useful method for grouping interventions.

Surveying the distribution of studies, we found certain combinations of function and relationship types were more common than others. All four relationship types were represented in studies of on-demand crisis support services, whereas only individuals with shared mental health experiences or similar demographic subgroups were involved in suicide/relapse prevention services, suggesting ongoing support after a crisis may be better suited to those with a greater peer connection than being members of the general public. Despite the integration of peer support specialists within many mental health systems, most studies of peer relationships based on shared lived experience of mental health challenges were conducted in other contexts, such as crisis lines or correctional facilities. This may be due to concerns over scope of practice, such that in settings where more highly trained clinicians are available, peers may be discouraged from addressing suicide risk; however, considering many studies involved members of the general public in suicide prevention, peer support specialists would appear adequately qualified to address suicide risk.

Acceptability and Effectiveness

While effectiveness data were lacking for all but a handful of studies, the studies included in our review suggest peer-based suicide support services are highly feasible and acceptable, especially as a complement or alternative to services provided by more formal mental healthcare approaches. Characteristics of peer services such as rapid access, low cost, availability outside of regular business hours, and enhanced privacy all likely contribute to greater acceptability and stand in contrast to the barriers to traditional mental health care (De Man & Labrèche-Gauthier, 1991; Miller & Gergen, 1998; Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2016; Pfeiffer et al., 2018). Additional evidence that peer services are able to reach persons who would not have otherwise sought help include persons participating in online mutual support groups who reported discussing information that would otherwise not been shared with others (Whitlock et al., 2006), similar feedback from crisis line callers (Miller et al., 1984), and the introduction of peer suicide to environments where access to mental health services is likely limited (e.g., within police departments; Dowling et al., 2006; Levenson & Dwyer, 2003).

Although limited by the available evidence, some generalizations can be made regarding effectiveness. Gatekeeper training programs appear to be effective in enhancing awareness of suicide risk and confidence in intervening when faced with a person in crisis. Peer-based interventions which target vulnerable subgroups are associated with reductions in the risk of suicide within these subgroups, though causality is not firmly established. Peer providers utilize many of the same therapeutic techniques in providing support to others that are used by trained therapists, and the feedback and support offered by peers are valued by persons receiving support. Peer-based support approaches allow for targeted outreach to vulnerable groups who might otherwise be unwilling or unable to access mental health support through more formal channels.

Implications for Practice

Due to insufficient controlled trial evidence demonstrating the effectiveness for peer-based programs for reducing suicide attempts or deaths, strong recommendations cannot be made for their implementation. However, the diversity of peer support functions and relationships utilized in suicide prevention services raises important considerations for implementation, including the training, supervision, and prevention of burnout among peer providers. We found wide variation in the training peers receive to deliver suicide prevention services. Training times range from four hours for gatekeeper training to over 70 hours for some crisis line responders and have included in-person and web-based instruction. Training programs should consider the function of the peer support provider, acuity of the clients they serve, and the feasibility of providing the training to the intended population.

Supervision of peer providers is also dependent on the functional role and setting. Gatekeepers who are members of the lay public or similar sociodemographic subgroups are unlikely to receive supervision, whereas crisis line workers or peer specialists working within a health system may benefit from regular meetings with a clinician supervisor who has developed experience supervising peers. Supervision of peers within a first responder workplace or institutions such as a colleges or correctional facilities may have more limited options for qualified peer supervisors, and thus, identifying appropriate supervisors should be considered early in implementation planning.

Furthermore, burnout among mental health clinicians is prevalent and negatively impacts workplace satisfaction and client care (Morse et al., 2012). It is likely that peer providers may also face similar challenges. Approaches to burnout are also likely to vary by setting and provider type. For example, it may be more feasible to limit work hours or provide greater flexibility for volunteers compared with employed peer specialists. Peer specialists working in mental healthcare settings have reported negative interactions with work colleagues, difficulties with understanding their role, and challenges with maintaining professional boundaries (Repper & Carter, 2011). Thus, it may be important for organizations newly adopting peer providers to address negative beliefs or attitudes held by the existing workforce.

Research Agenda

Scientific inquiry into the role of peer support in suicide prevention is in its infancy given the identified literature consists largely of program descriptions and evaluations rather than hypothesis-testing research. We therefore provide a broad framework for future research addressing six core domains (Table 2). To establish effectiveness, future studies should employ rigorous trial designs to better support determinations of causal inference. For population-based intervention such as gatekeeper training or on-demand crisis support available to the public or within institutions, individual-level randomization may not be practical, and therefore, cluster-randomized trials or quasi-experimental designs such as interrupted time series should be employed. Prioritization should be given to interventions that have shown associations with reductions in suicide risk, such as the institutional programs within the Montreal police department or Ukrainian military, or those that are already widely implemented (e.g., gatekeeper training). Recognizing that research opportunities may not be available to many peer-based suicide prevention programs, future program descriptions would be enhanced by incorporating suicide-related outcomes, including deaths, attempts, acute care, or measures of ideation (e.g., Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale; Posner et al., 2011; suicidal ideation item of the PHQ9; Rossom et al., 2017).

TABLE 2.

Research agenda for peer interventions to prevent suicide

| Domain | Priority target questions for research on peer suicide prevention |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Effectiveness | Which peer support intervention models (e.g., gatekeeper training, crisis support lines) reduce suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, or suicide deaths compared to no intervention? Does effectiveness of these intervention models differ when delivered by peers compared to those without a peer relationship? |

| Mechanisms | Which peer support activities (e.g., disclosure of lived experience, tailored information/advice) act on mechanisms (e.g., decreased stigma or loneliness, increased hope or help-seeking) to reduce suicide-related outcomes? |

| Moderators | Are peer support interventions more effective for certain individuals, such as those who are socially isolated, lack peers within their demographic subgroup or institution, or have limited access to other mental health services? Are certain peer characteristics associated with greater effectiveness? |

| Innovation | What new functions can peers provide in suicide prevention (e.g., lethal means restriction) and what new approaches (e.g., computer-based online support) can be utilized to improve effectiveness or reach? |

| Potential harms | What potential harms should be assessed (e.g., increased hopelessness or isolation if unable to relate to a peer; unhelpful advice)? How often do these potential harms occur, how often do they increase adverse suicide-related outcomes, and how can they be mitigated? |

| Implementation | What policies and resources are needed to facilitate adoption, fidelity, and sustainability of effective peer support interventions for suicide prevention? |

Exploration of the mechanisms and moderators of peer support will be critical to replication of effective programs and further intervention development. There are many different approaches; peers might employ in suicide prevention roles including the mutuality of the peer relationship, the degree of structure, and content focus (Davidson et al., 2006; Valenstein et al., 2016). Some aspects of the relationship and content focus are specific to peers (e.g., disclosing a similar lived experience or identity) while many are shared with other support and treatment providers (e.g., empathic listening, advice giving). These activities may in turn have various effects on individuals at risk for suicide, such as decreased stigma or sense of isolation, instillation of hope, or increased help-seeking behaviors. Research is needed to discern the effects of peer-specific activities from common therapeutic elements and which effects reduce the risk of suicide. Not all individuals at risk for suicide are likely to benefit from peer support, and therefore, research should also seek to identify those most likely to benefit, with particular attention to baseline levels of social support, mental health treatment engagement, and shared characteristics (e.g., matching) with the peer support provider.

We used the CASP framework to identify potential areas of innovation in peer-based suicide prevention services. We found peer-based suicide prevention services most often focused on identifying and responding to persons in crisis and increasing help-seeking. However, peer suicide prevention services did not typically focus on reducing access barriers to evidence-based treatments (Gulliver et al., 2010; Haugen et al., 2017; Kantor et al., 2017) or improving life skills to build resilience, and no services focused on reducing access to lethal means of suicide. In addition to the potential for innovation in these potential roles for peers, new models for accessing peer services (e.g., the role of mobile devices), training peer support providers, and ensuring fidelity may be important for improving reach and sustainability of effective programs.

While none of the studies in our review reported harms related to participation in peer support services for suicide prevention, Rennick-Egglestone et al. (2019) describe several harmful outcomes reported by individuals with mental health problems who have listened to other’s mental health recovery narrative including the following: feelings of inadequacy and disconnection when comparing themselves to others that have recovered, pessimism, and being burdened or saddened by the other person’s experiences. Future research should assess the frequency of these and other potential harms and their relationships to adverse suicide-related outcomes.

If peer support interventions are shown to be effective with favorable risk-to-benefit profiles, anticipated barriers to implementation include dissemination of effective models to potential adopters; integration within existing services, training, and selection of peer providers; and sustainable financing. Hybrid implementation-effectiveness trial designs may facilitate future implementation of new intervention models (Curran et al., 2012). Implementation studies will be necessary to clarify differences in barriers and strategies between general population-facing interventions such as gatekeeper training and those delivered within healthcare systems given the differences.

Limitations

This review is limited in that our literature search may have missed some relevant studies. We included only published articles and book chapters available from research database searches—additional information on peer suicide prevention services may be available via resources such as organization websites or agency reports. Publication bias could also result in an over-estimate of the benefits of peer-based suicide prevention services. Our review did not include descriptions of how particular aspects of the peer relationship (e.g., similar race or prior experiences related to suicide) were specifically utilized to impact suicide risk; this level of detail was often missing from intervention descriptions. Because this was a scoping review and not a systematic review of effectiveness, the study was not eligible for PROSPERO registration nor were all PRISMA reporting items applicable (Moher et al., 2009).

Conclusion

Peer-based interventions appear to represent a significant component of available suicide prevention services, allowing for enhanced care opportunities for patients who would not have received support through traditional mental health channels. However, additional work needs to be done to properly evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions in addressing suicidal risk, develop linkages between these services and traditional mental health services, assess the role that peer support professionals can play in the process of addressing suicidal risk, and create appropriate professional support for peer providers Future work would benefit from increased evaluation rigor, the selection of outcome measures linked to suicide-based outcomes, and systematic intervention approaches informed by gaps in the literature.

Highlights.

We conducted a scoping review on peer-delivered suicide prevention services and their outcomes.

Peers of individuals at risk for suicide may be able to play important roles in suicide prevention.

Found that the majority of published studies were program descriptions or uncontrolled trials.

Peer support interventions show promise in addressing suicide risk.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

References

- Arensman E, Coffey C, Griffin E, Van Audenhove C, Scheerder G, Gusmao R et al. (2016) Effectiveness of depression-suicidal behaviour gatekeeper training among police officers in three European regions: Outcomes of the Optimising Suicide Prevention Programmes and Their Implementation in Europe (OSPI-Europe) study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 62(7), 651–660. 10.1177/0020764016668907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armson S (1997a) Suicide and cyberspace – Befriending by e-mail. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 18, 103–105. [Google Scholar]

- Armson S (1997b) The perspective of a volunteer-based suicide-prevention organization. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 18, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Bagley C (1968). The evaluation of a suicide prevention scheme by an ecological method. Social Science & Medicine (1967), 2 (1), 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale C (2001) Befriending in cyberspace: Challenges and opportunities. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 22, 10–11. 10.1027//0227-5910.22.1.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak A (2007) Emotional support and suicide prevention through the Internet: A field project report. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(2), 971–984. 10.1016/j.chb.2005.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barak A & Bloch N (2006) Factors related to perceived helpfulness in supporting highly distressed individuals through an online support chat. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9(1), 60–68. 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber JG, Blackman EK, Talbot C & Saebel J (2004) The themes expressed in suicide calls to a telephone help line. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(2), 121–125. 10.1007/s00127-004-0718-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker E, Kõlves K & De Leo D (2014) Management of suicidal and self-harming behaviors in prisons: Systematic literature review of evidence-based activities. Archives of Suicide Research, 18(3), 227–240. 10.1080/13811118.2013.824830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraclough BM, Jennings C & Moss JR (1977) Suicide prevention by the Samaritans: A controlled study of effectiveness. The Lancet, 310(8031), 237–239. 10.1016/S0140-6736(77)92847-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Brown G, Berchick RJ, Stewart BL & Steer RA (2006) Relationship between hopelessness and ultimate suicide: A replication with psychiatric outpatients. Focus, 147(2), 190–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggar K & Neal D (1996) Caring for the suicidal in custody: Developing a multi-disciplinary approach. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 33(3), 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchery EE, Barna M, Babalola E, Friend D, Brown JD, Blyler C et al. (2018) The effectiveness of a peer-staffed crisis respite program as an alternative to hospitalization. Psychiatric Services, 69(10), 1069–1074. 10.1176/appi.ps.201700451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges LS, Sharma M, Lee JHS, Bennett R, Buxbaum SG & Reese-Smith J (2018) Using the PRECEDE-PROCEED model for an online peer-to-peer suicide prevention and awareness for depression (SPAD) intervention among African American college students: Experimental study. Health Promotion Perspectives, 8(1), 15. 10.15171/hpp.2018.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet AF, Lemay L & Belliveau G (1994) Correspondence as adjunct to crisisline intervention in a suicide prevention center. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 15(2), 65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AE & Arkowitz H (2015) Meta-analysis of the effects of peer-administered psychosocial interventions on symptoms of depression. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(3–4), 455–471. 10.1007/s10464-015-9718-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capp K, Deane FP & Lambert G (2001) Suicide prevention in Aboriginal communities: Application of community gatekeeper training. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25(4), 315–321. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00586.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano C (2012) Reciprocal Peer Support (RPS): A decade of not so random acts of kindness. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 14(2), 105–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien WT, Lui S & Clifton AV (2013). Peer support for schizophrenia (Protocol). Chochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (12), CD010880. 10.1002/14651858.CD010880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinman MJ, Weingarten R, Stayner D & Davidson L (2001) Chronicity reconsidered: Improving person-environment fit through a consumer-run service. Community Mental Health Journal, 37(3), 215–229. 10.1023/A:1017577029956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coman GJ, Burrows GD & Evans BJ (2001) Telephone counselling in Australia: Applications and considerations for use. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 29(2), 247–258. 10.1080/03069880124904 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coveney CM, Pollock K, Armstrong S & Moore J (2012) Callers’ experiences of contacting a national suicide prevention helpline: Report of an online survey. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 33(6), 313–324. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisis Call Center (2018) Suicide prevention training – crisis call center. Available at: http://crisiscallcenter.org/suicide-prevention-training/ [Accessed 07 18 2020].

- Crisis Text Line (2018). Volunteer. Available at: https://www.crisistextline.org/volunteer/ [Accessed 07 18 2020].

- Cross W, Matthieu MM, Cerel J & Knox KL (2007) Proximate outcomes of gatekeeper training for suicide prevention in the workplace. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37(6), 659–670. 10.1521/suli.2007.37.6.659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross W, Matthieu MM, Lezine D & Knox KL (2010) Does a brief suicide prevention gatekeeper training program enhance observed skills? Crisis, 31, 149–159. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM & Stetler C (2012) Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care, 50(3), 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigle MS, Daniel AE, Dear GE, Frottier P, Hayes LM, Kerkhof A et al. (2007) Preventing suicide in prisons, Part II: International comparisons of suicide prevention services in correctional facilities. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 28(3), 122–130. 10.1027/0227-5910.28.3.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgin RS, Maline S & Driscoll P (2011) Sustaining recovery through the night: Impact of a peer-run warm line. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35(1), 65–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Chinman M, Sells D & Rowe M (2006) Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: A report from the field. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32(3), 443–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Man A & Labrèche-Gauthier L (1991) Suicide ideation and community support: An evaluation of two programs. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47(1), 57–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaliwal R & Harrower J (2009) Reducing prisoner vulnerability and providing a means of empowerment: Evaluating the impact of a listener scheme on the listeners. The British Journal of Forensic Practice, 11(3), 35–43. 10.1108/14636646200900021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty C & Tse S (2011) Can consumer-led mental health services be equally effective? An integrative review of CLMH services in high-income countries. Community Mental Health Journal, 47(3), 252–266. 10.1007/s10597-010-9321-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling FG, Genet B & Moynihan G (2005) A confidential peer-based assistance program for police officers. Psychiatric services, 56(7), 870–871. 10.1176/appi.ps.56.7.870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling FG, Moynihan G, Genet B & Lewis J (2006). A peer-based assistance program for officers with the New York City Police Department: Report of the effects of Sept. 11, 2001. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(1), 151–153. 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumesnil H & Verger P (2009) Public awareness campaigns about depression and suicide: A review. Psychiatric Services, 60(9), 1203–1213. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.9.1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont J & Jones K (2002) Findings from a consumer/survivor defined alternative to psychiatric hospitalization. Outlook, 3 (Spring), 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenberg C & Schott M (2017) An empirical analysis of Internet message boards for self-harming behavior. Archives of Suicide Research, 21(4), 672–686. 10.1080/13811118.2016.1259597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emotions Anonymous (2003) It works if you work it. St. Paul, MN: Emotions Anonymous. [Google Scholar]

- Enright MF & Parsons BV (1976) Training crisis intervention specialists and peer group counselors as therapeutic agents in the gay community. Community mental health journal, 12(4), 383–391. 10.1007/BF01411077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhoury W (2002) Suicidal callers to a national helpline in the UK: A comparison of depressive and psychotic sufferers. Archives of Suicide Research, 6(4), 363–371. 10.1080/13811110214532 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finney EJ, Buser SJ, Schwartz J, Archibald L & Swanson R (2015) Suicide prevention in fire service: The Houston Fire Department (HFD) model. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 21, 1–4. 10.1016/j.avb.2014.12.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhr DC, Salisbury TT, De Silva MJ, Atif N, van Ginneken N, Rahman A et al. (2014) Effectiveness of peer-delivered interventions for severe mental illness and depression on clinical and psychosocial outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(11), 1691–1702. 10.1007/s00127-014-0857-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funkhouser CJ, Zakriski AL & Spoltore JD (2017) Evaluating peer-peer depression outreach: College students helping peers approach and respond to students in crisis. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 22(1), 19–28. 10.24839/2325-7342.jn22.1.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter M (1988) Zealous self-help groups as adjuncts to psychiatric treatment: A study of Recovery, Inc. American Journal of Psychiatry, 145(10), 1248–1253. 10.1176/ajp.145.10.1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilat I, Lobel TE & Gil T (1998) Characteristics of calls to Israeli hotlines during the Gulf War. American Journal of Community Psychology, 26(5), 697–704. 10.1023/A:1022146130836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilat I & Shahar G (2007) Emotional first aid for a suicide crisis: Comparison between telephonic hotline and internet. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 70(1), 12–18. 10.1521/psyc.2007.70.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilat I & Shahar G (2009) Suicide prevention by online support groups: An action theory-based model of emotional first aid. Archives of Suicide Research, 13(1), 52–63. 10.1080/13811110802572148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilat I, Tobin Y & Shahar G (2011) Offering support to suicidal individuals in an online support group. Archives of Suicide Research, 15(3), 195–206. 10.1080/13811118.2011.589675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilat I, Tobin Y & Shahar G (2012) Responses to suicidal messages in an online support group: Comparison between trained volunteers and lay individuals. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(12), 1929–1935. 10.1007/s00127-012-0508-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Cross W, Pisani AR, Munfakh JL & Kleinman M (2013) Impact of applied suicide intervention skills training on the national suicide prevention lifeline. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 43(6), 676–691. 10.1111/sltb.12049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbury S (1999) No, it’s not just listening: A column from Befrienders International. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 20(2), 56–58. 10.1027//0227-5910.20.2.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Stoneking BC, Humphreys K, Sundby E & Bond J (2008) A randomized trial of a mental health consumer-managed alternative to civil commitment for acute psychiatric crisis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 42(1–2), 135–144. 10.1007/s10464-008-9180-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver A, Griffiths KM & Christensen H (2010) Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 113. 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall B & Gabor P (2004) Peer suicide prevention in a prison. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 25(1), 19–26. 10.1027/0227-5910.25.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall B & Schlosar H (1995) Repeat callers and the Samaritan telephone crisis line—a Canadian experience. Crisis The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 16(2), 66–71. 10.1027/0227-5910.16.2.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen PT, McCrillis AM, Smid GE & Nijdam MJ (2017) Mental health stigma and barriers to mental health care for first responders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 94, 218–229. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Curtin SC & Warner M (2020). Increase in suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 362. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegerl U, Wittenburg L, Arensman E, Van Audenhove C, Coyne JC, McDaid D et al. (2009) Optimizing suicide prevention programs and their implementation in Europe (OSPI Europe): An evidence-based multi-level approach. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 428. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holding TA (1974) The B.B.C Befrienders’ series and its effects. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 124(582), 470–472. 10.1192/bjp.124.5.470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes D, Molloy L, Beckett P, Field J & Stratford A (2013) Peer Support Workers hold the key to opening up recovery-orientated service in inpatient units. Australasian Psychiatry, 21(3), 282–283. 10.1177/1039856212475332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings C, Barraclough BM & Moss JR (1978) Have the Samaritans lowered the suicide rate? A controlled study. Psychological Medicine, 8(3), 413–422. 10.1017/S0033291700016081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Lamb D, Marston L, Osborn D, Mason O, Henderson C et al. (2018) Peer-supported self-management for people discharged from a mental health crisis team: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 392(10145), 409–418. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31470-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Mason O, Osborn D, Milton A, Henderson C, Marston L et al. (2017) A randomised controlled trial of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a peer delivered self-management intervention to prevent relapse in crisis resolution team users (the CORE self-management trial). British Medical Journal Open, 7(10), e015665. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Nolan F, Pilling S, Sandor A, Hoult J, McKenzie N et al. (2005) Randomised controlled trial of acute mental health care by a crisis resolution team: the north Islington crisis study. BMJ, 31, 599. 10.1136/bmj.38519.678148.8F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junker G, Beeler A & Bates J (2005) Using trained inmate observers for suicide watch in a federal correctional setting: A win-win solution. Psychological Services, 2(1), 20–27. 10.1037/1541-1559.2.1.20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor V, Knefel M & Lueger-Schuster B (2017) Perceived barriers and facilitators of mental health service utilization in adult trauma survivors: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 52, 52–68. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumata Y, Narita T & Nakagawa T (2017) Development of a suicide prevention education program for university students: A single-arm pilot study. Asian journal of psychiatry, 30, 190. 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keir N (2000) Intervention without interference: A column of Befrienders International. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 21(4), 156–158. 10.1027//0227-5910.21.4.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AR, Cnaan RA & Whitecraft J (1998) Significance of peer social support with dually diagnosed clients: Findings from a pilot study. Research on Social Work Practice, 8(5), 529–551. 10.1177/104973159800800503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kryrouz E, Humphreys K & Loomis C (eds.) (2002) Chapter 4: A review of research on the effectiveness of self-help mutual aid groups. In: White B & Madara E (Eds.). American Self-Help Clearinghouse Self-Help Group sourcebook, 7th edition. American Self-Help Group Clearinghouse.71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lester D (2005) The impact of the samaritan centres on suicide in Scotland. Psychological Reports, 97(2), 587–588. 10.2466/pr0.97.2.587-588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester D (2009) The use of the Internet for counseling the suicidal individual: Possibilities and drawbacks. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 58(3), 233–250. 10.2190/OM.58.3.e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RL Jr (2007) Prevention of traumatic stress in law enforcement personnel: A cursory look at the roles of peer support and critical incident stress management. Forensic Examiner, 16(3), 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RL Jr & Dwyer LA (2003) Peer support in law enforcement: Past, present, and future. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 5(3), 147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RL Jr, O’Hara AF & Clark R Sr (2010) The badge of life psychological survival for police officers program. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 12(2), 95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]