Abstract

The gut microbiome has an important role in host development, metabolism, growth, and aging. Recent research points toward potential crosstalk between the gut microbiota and the growth hormone (GH)/insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) axis. Our laboratory previously showed that GH excess and deficiency are associated with an altered gut microbial composition in adult mice. Yet, no study to date has examined the influence of GH on the gut microbiome over time. Our study thus tracked the effect of excess GH action on the longitudinal changes in the gut microbial profile (ie, abundance, diversity/maturity, predictive metabolic function, and short-chain fatty acid [SCFA] levels) of bovine GH (bGH) transgenic mice at age 3, 6, and 12 months compared to littermate controls in the context of metabolism, intestinal phenotype, and premature aging. The bGH mice displayed age-dependent changes in microbial abundance, richness, and evenness. Microbial maturity was significantly explained by genotype and age. Moreover, several bacteria (ie, Lactobacillus, Lachnospiraceae, Bifidobacterium, and Faecalibaculum), predictive metabolic pathways (such as SCFA, vitamin B12, folate, menaquinol, peptidoglycan, and heme B biosynthesis), and SCFA levels (acetate, butyrate, lactate, and propionate) were consistently altered across all 3 time points, differentiating the longitudinal bGH microbiome from controls. Of note, the bGH mice also had significantly impaired intestinal fat absorption with increased fecal output. Collectively, these findings suggest that excess GH alters the gut microbiome in an age-dependent manner with distinct longitudinal microbial and predicted metabolic pathway signatures.

Keywords: growth hormone, bGH mice, longitudinal gut microbiome, short-chain fatty acids

The gut microbiome has been implicated in maintaining host health from infancy to old age. The microbial community, also termed the gut microbiota, comprises trillions of bacteria, viruses, and fungi that colonize the entire gastrointestinal tract, with the majority concentrated in the distal ileum and colon (1-3). The gut microbiome is accordingly defined as the resident gut microbiota with their collective genomes and by-products, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (2, 4). Early in life, the gut microbiome affects the development of the immune system, intestinal barrier, nervous system, endocrine system, metabolism, and overall growth (5). Microbial immaturity, or a delay in the expected development of the microbial community, has been associated with chronic undernutrition, anorexia nervosa, and acute malnutrition (all of which are states of decreased growth hormone [GH] action) (6-9). In adulthood, the gut microbiome continues to influence host physiology and pathophysiology. For instance, lack of diversity (or dysbiosis) has been associated with metabolic diseases (diabetes, obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular disease) (10); many of which are also associated with GH alterations. Furthermore, specific microbes and microbial by-products like SCFAs delineate between healthy and accelerated aging (11-13).

GH similarly has been associated with both the development (growth) and aging of individuals. That is, GH promotes both linear growth and the growth of many organs (including intestines) and has potent metabolic effects. GH has also been associated with aging, as increased GH decreases longevity whereas decreased GH action is associated with improved longevity (14). This effect on aging has perhaps best been described in mouse lines with altered GH action. GH receptor knockout (GHR–/–) mice with decreased GH action have improved insulin sensitivity, do not develop cancer or diabetes, and are extremely long-lived (15, 16). Inversely, bovine transgenic GH (bGH) mice have constant, ectopic production of GH and chronically increased GH signaling. The bGH mice develop systemic disease, including insulin resistance, cardiac and adipose tissue fibrosis, type 2 diabetes, and accelerated aging, typically dying between age 13 and 15 months compared to approximately 30 months for wild-type (WT) mice depending on background strain (17-21).

Recent research points toward a bidirectional relationship between the GH/IGF-1 axis and the gut microbiota. Several studies have shown that microbes regulate bone and linear growth by altering IGF-1 levels (22-25). For instance, antibiotic-treated and germ-free mice both have decreased IGF-1 levels. Meanwhile, colonization of the commensal microbiota in the gut increases serum IGF-1, likely through SCFAs, and thus, promotes bone formation and host development (22, 23, 26). The addition of Lactobacillus plantarum to the gut flora in nutrient-depleted mice increases IGF-1 levels and restores linear growth (22). Inversely, GH and IGF-1 have both been shown to influence the microbial abundance (the amount of each bacterium) and diversity (which species are present and their proportionality to each other) in adult mice (7, 27). Recently, our laboratory has demonstrated that mouse lines with altered GH action (both GH deficient mice and bGH mice) have opposing microbial findings, suggesting that GH influences the presence of certain microbes (such as Lactobacillus and Lachnospiraceae) and affects microbial maturation and predictive metabolic function (28).

Although research demonstrates a relationship between the GH/IGF-1 axis and the gut microbiota at a single, adult time point, the nature of the longitudinal relationship between GH and the gut microbiome remains unclear. Thus, this study investigated the effect of excess GH on the gut microbial profile from a young, healthy adult age (3 months) to an older adult time point (12 months) in a mouse line that exhibits accelerated aging. Specifically, longitudinal changes were characterized by microbial abundance (or which microbes were present), richness (number of microbial populations), evenness (proportionality of microbes), β diversity (differences in microbial community), maturity of the microbial community (or expected development), and function of the microbiome (predictive metabolic function and SCFA levels) in male bGH mice and littermate controls. Moreover, the relationship of GH and the longitudinal gut microbiome was analyzed in the context of metabolic and intestinal phenotype in an accelerated aging mouse line compared to age-matched littermate controls.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Line

Male bGH mice from a pure C57BL/6J background and their respective littermate controls were used. The bGH mouse line has been previously characterized (17, 18). Mice used in this experiment were all genotyped 4 weeks after birth from tail snips using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers as described previously (18).

Metabolic, intestinal, and microbiome measurements in the bGH mice and their littermate controls occurred at age 3, 6, and 12 to 13 months (n = 7 for the longitudinal cohort and n = 10 for each time point). Male mice were chosen to eliminate the confounding factor of sex on the gut microbiome. These ages match similar time points used in previous studies that have evaluated the metabolic, growth, and accelerated aging phenotype in bGH mice (17, 20). A separate cohort of bGH and control mice were used to assess the intestinal fat absorption at ages 3 months (n = 5 bGH; 4 WT) and 6 months (n = 9 bGH; 10 WT). A subset of the longitudinal cohort (n = 3 per group) was used at age 13 months for the intestinal fat absorption assay and afterwards, euthanized for intestinal gross anatomy and morphology. All bGH mice and littermate controls were housed separately by genotype in a temperature-controlled (23 °C) vivarium and exposed to a 14-hour light, 10-hour dark cycle. All mice were allowed access to chow (ProLab RMH 3000; PMI Nutrition International) and water ad libitum. All procedures performed on the mice were approved by the Ohio University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and are in accordance with all standards set forth by federal, state, and local authorities.

Body Weight and Composition

Body weight and composition were measured in bGH mice and littermate controls (n = 10 per group) at age 3, 6, and 12 months using the NMR Bruker Minispec as previously described (17).

Blood Glucose

Fasting blood glucose levels were collected in bGH mice and littermate controls at age 3, 6, and 12 months after an overnight 12-hour fast from tail vein bleeding using OneTouch test strips and glucometers.

Intestinal Fat Absorption

Fecal pellets were freshly collected from each cohort of bGH mice and littermate controls before the intestinal fat absorption assay using the protocol described previously (28). For the assay, mice were housed individually the first day, and normal chow was replaced with a semisynthetic chow with 5% of the fat content coming from sucrose polybehenate (nonabsorbable food additive) for 4 days. Fecal pellets were collected from each mouse on days 3 and 4 and were stored at –80 °C. The number of fecal pellets was recorded per mouse/cage to approximate fecal output in a 24-hour timespan. Samples were sent to University of Cincinnati Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center (MMPC) for analysis using gas chromatography and evaluation of the ratio of behenate to other fatty acids in the feces as previously described (29).

Fecal Collection and Fecal DNA Isolation for Microbiome Analyses

Fecal pellets were collected following a protocol previously described (28). Mice were allowed to naturally defecate, or after 10 minutes, encouraged to defecate through gentle massage in the hind-back region. All pellets defecated by each mouse at each time point were collected with sterilized forceps, weighed, measured for length, and immediately frozen on dry ice. Equipment and the bench surface were sterilized with diluted 1:10 bleach solution between each mouse collection. Frozen fecal pellets were stored at –80 °C and shipped on dry ice for 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing to the Microbiome and Host Response Core of MMPC at University of California (UC), Davis. Total DNA from each individual pellet was extracted using Qiagen’s QIAamp PowerFecal DNA Isolation kit following the manufacturer’s protocol with minor modifications as previously described (28). Quality of DNA was tested with a Qubit (Invitrogen). DNA was then stored in a –80 °C freezer until 16S rRNA sequencing or shipped back for quantitative PCR (qPCR).

16S Ribosomal RNA Sequencing

Sample libraries were prepared and analyzed by barcoded amplicon sequencing as described previously (30). Purified DNA was amplified on the hypervariable V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene through PCR with primers F515 (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and R806 (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). The resultant amplicons (250 bp) were sequenced using pair end, high-throughput sequencing with Illumina MiSeq (20 000 avg. sequence read depth) at the UC, Davis Genomics Facility.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

qPCR was used to validate our 16S rRNA sequencing microbial abundance findings as previously described (28). In brief, the same DNA isolated for 16S rRNA sequencing was used with several different primers at the kingdom (total microbial populations), phylum, and genus/species level (28). Additional primers for Bifidobacterium, Ruminococaceae, and Lactobacillus plantarum were used in this study (sequences provided in Supplementary Table S1) (31). The same interplate control was used across all plates.

Microbiome Data Analysis

Microbial abundance, richness, evenness, diversity, maturity, and predictive metabolic function were analyzed between bGH mice and littermate controls at each time point and longitudinally to look at the interaction between genotype and age on the adult microbiome. The bGH and control microbiome at the 6-month time point were previously characterized in comparison of 6-month-old GH–/– mice (28).

Microbial abundance analysis

Data derived from sequencing that were previously demultiplexed at the UC, Davis Genomics Facility were then analyzed through the bioinformatics pipeline of QIIME 2 2019.10 version (32, 33) using dada2 and classify-sklearn with the 99% SILVA 132 16S reference library as described previously (28, 34). Microbial abundance was analyzed from the phylum to genus level for each mouse and averaged for bGH mice and littermate controls at age 3, 6, and 12 months.

Microbial diversity and maturity

Diversity analyses were run on the resultant feature table sequences using QIIME 2 core diversity plugin, as described previously (28). Longitudinal analysis of microbial richness, evenness, and β diversity was assessed through linear mixed-effects models with QIIME 2 longitudinal plugin with age and genotype set as factors.

Microbial maturity is defined by the expected development of the microbial community (species, richness, evenness); this index quantifies the relative change in the microbial community of the experimental group compared to age-matched controls. Maturity was assessed through q2-classifier on QIIME 2 (8). This method establishes, trains, and validates the microbial maturity from a Random Forests regression model on control WT mice at age 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months and then predicts the microbial age both of bGH mice and separate WT controls. Maturity index z scores (MAZ) are calculated based on the predicted microbial age compared to the actual chronological age of the mice. MAZs are calculated based on the predicted microbial age compared to the actual chronological age of the mice.

Unique microbial signature

A partial least square-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) using abundance at the genus level was performed using R to identify bacterial signatures unique to the genotype differences, as described previously (28). An additional analysis, variable influence on projection (VIP) scores, was conducted using R, and a score higher than 1.0 was determined as a genus that differentiated the bGH mouse line compared to the controls between the 3 time points and across all the 3 time points (termed the longitudinal microbial signature).

Predictive metabolic function

The predictive metabolic function was assessed using the full Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States 2 (PICRUSt2) pipeline with EPA-NG, as described previously (28). PLS-DA and VIP analyses were then performed to identify metabolic pathways that differentiate the bGH and littermate controls between the 3 time points and across all time points (referred to as the longitudinal predicted metabolic pathway signature).

Quantification of Short-Chain Fatty Acids

Frozen fecal samples from the longitudinal bGH and WT mice at age 3, 6, and 13 months were sent to the Metabolomics Mass Spectrometry core at the Cleveland Clinic Center for Microbiome and Human Health. Targeted gas chromatography–mass spectrometry was then performed on the samples to determine the concentration of SCFAs (acetic acid, butyric acid, lactic acid, isovaleric acid, propionic acid, and succinic acid) using the following protocol (35). Additional analyses were conducted to analyze the effect of genotype and age on SCFA levels (2-way analysis of variance [ANOVA] and gneiss function in QIIME 2) and correlate to GH-associated microbes and predictive metabolic pathways (using qiime2 songbird) (36).

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as mean ± SEM. Statistics were performed using QIIME 2 2019.10 version and R version 3.6.3. Normality of data was tested plotting the data on a Q-Q plot and through Shapiro-Wilks test. For all single time point measurements, equality of variance was tested using the F test of equal variance. The Levene homogeneity of variance was used when single-point data had an abnormal distribution (microbial abundance) or for data with multiple time points (ie, body composition or microbial richness and evenness). For all single time point measurements that passed normality and homogeneity of variance, t tests were performed. For multiple time point analyses (ie, body weight, body composition, and α diversity [which passed normality and homogeneity of variance metrics]) (37), 2-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey analysis were performed. For microbial abundance, data were transformed using a centered log ratio via compositions on R and then 2-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey analysis were performed. For β diversity, permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with 1000 permutations through QIIME 2.0 with post hoc Bonferroni corrections was performed. For longitudinal analysis of α and β diversity, Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric tests were performed using QIIME 2.0. Statistical significance was set at P less than .05 (except for correlational analysis as indicated later). Effect size was calculated to describe the strength (or “biological significance”) of the findings through 1 of 2 ways: 1) For all single time point data, Cohen d was calculated to determine the effect of genotype; and 2) for multiple time point data, partial omega-squared (ω 2) was calculated to assess the strength of genotype, age, and interaction of genotype and age. Cohen d is defined by the following cutoffs: a very small effect size is 0.01, small effect size 0.20, medium 0.50, large 0.80, and very large 1.20 (38, 39). Partial ω 2 is defined between –1 and 1 with effect size decreasing as it approaches 0.

Correlations were also used to examine the relationship between intestinal and metabolic phenotype measurements and microbial composition and SCFA metabolites. Pearson correlation was used for fecal weight, whereas the nonparametric Spearman correlation was used for body composition measurements due to failed Henze-Zirkler multivariate normality test (40). To correct for the number of correlations tested for each SCFA, the statistical significance was set at P equal to .008. Finally, to understand the context of intestinal/metabolic phenotype and fecal output on the microbiome findings, a linear mixed-effects model was created for microbial diversity and abundance with the following variables: fecal weight, intestinal length, inflammation, and genotype, using R (41, 42).

Results

Metabolic and Intestinal Phenotype of Bovine Transgenic Growth Hormone Mice and Controls at Age 3, 6, and 12 Months

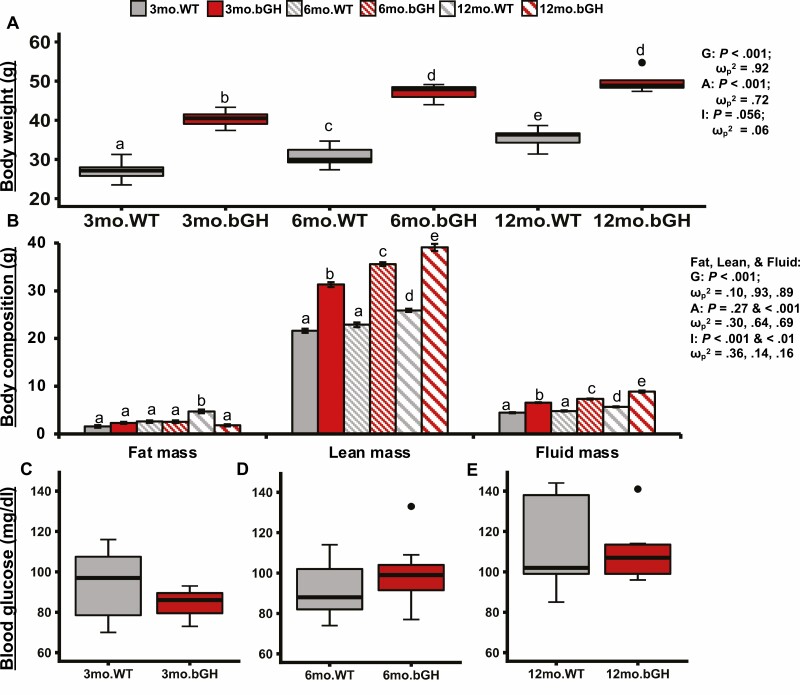

To assess the general metabolic phenotype of the bGH mice at age 3, 6, and 12 months, body weight, body composition, and blood glucose levels were measured (Fig. 1). Body weight significantly increased in both groups as the mice aged (P < .001 and ω p2 = .72). Across all 3 time points, the bGH mice had significantly increased body weight compared to controls with a large effect size (P < .001 and ω p2 = .92) (Fig. 1A). At age 3 months, bGH mice had significantly increased fat, lean, and fluid mass. The absolute weights of both lean and fluid mass remained significantly increased compared to controls at age 6 and 12 months. However, bGH mice stopped accumulating fat mass by 6 months and had significantly decreased fat mass by 12 months compared to controls (Fig. 1B). No significant difference was observed in blood glucose levels between bGH mice and littermate controls at age 3, 6, or 12 months; however, there was a trending decrease in glucose levels in bGH mice at 3 months (Cohen d = 0.58) and a trending increase at 6 months (Cohen d = 0.45) (Fig. 1C-1E).

Figure 1.

Metabolic phenotype in bovine transgenic growth hormone (bGH) mice and littermate controls at age 3, 6, and 12 months. Two-way repeated analysis of variance and post hoc Tukey analysis determined the effect of genotype, age, and the interaction between genotype and age for body composition and weight. A to C, Body weight at 3 time points. A, Body weight at age 3 months in bGH mice and littermate controls. *P less than .05. B, Body weight at age 6 months. *P less than .05. C, Body weight at age 12 months. *P less than .05. D to F, Body composition. All are significantly explained by genotype and interaction of age and genotype; lean and fluid mass are significantly explained by genotype, age, and the interaction. D, Body composition at age 3 months. *P less than .05. E, Body composition at age 6 months. *P less than .05. F, Body composition at age 12 months. *P less than .05 for all 3 measurements. G to I, Fasting blood glucose. G, Blood glucose levels at age 3 months. No significant difference seen between bGH mice and controls with medium effect size (Cohen d = 0.58). H, Blood glucose levels at age 6 months. (Cohen d = 0.45) I. Blood glucose levels at age 12 months (Cohen d = 0.18). Single dots on H and I indicate outliers.

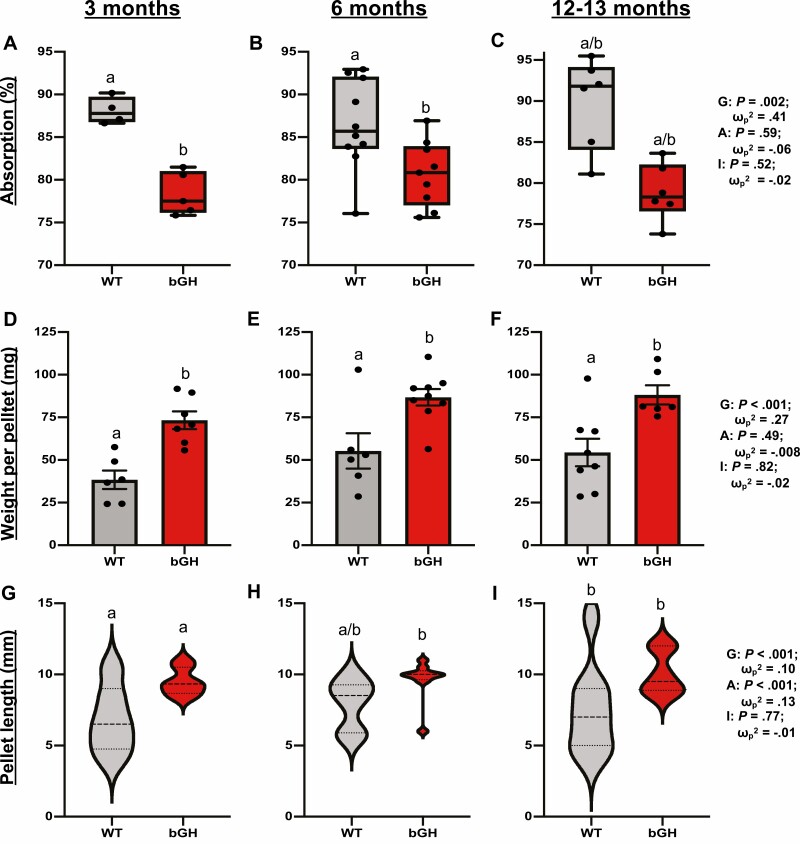

In terms of intestinal phenotype, findings demonstrate that excess GH consistently altered both intestinal fat absorption and fecal output throughout life. Fat absorption was significantly explained by genotype across all 3 ages with a significant decrease observed in bGH mice compared to littermate controls (Fig. 2A-2C). Fecal pellets weighed significantly more in bGH mice relative to controls at age 3, 6, and 12 to 13 months; these changes were also significantly explained by genotype (Fig. 2D-2F). Length of fecal pellets was also significantly explained by genotype and age with a trending increase observed in bGH mice (Fig. 2G-2I). Moreover, the bGH mice tended to produce more fecal pellets in the span of 24 hours at age 3 and 6 months (P = .055 and .08) with no difference observed at 13 months (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Intestinal fat absorption and fecal output metrics in bovine transgenic growth hormone (bGH) mice and littermate controls at age 3, 6, and 12 months. Two-way repeated analysis of variance and post hoc Tukey analysis determined the effect of genotype, age, and the interaction between genotype and age. Letters represent significant differences between genotypes across all 3 time points. A to C, Intestinal fat absorption. A, Fat absorption in bGH mice and controls at age 3 months. B, Fat absorption at age 6 months. C, Fat absorption at age 13 months. D to F, Fecal pellet weight in bGH mice and controls. D, Pellet weight at age 3 months. E, Pellet weight at age 6 months. F, Pellet weight at age 12 to 13 months. G to I, Fecal pellet length in bGH mice and controls. G, Pellet length at age 3 months. H, Pellet length at age 6 months. I, Pellet length at age 12 months.

Intestinal gross anatomy and morphology findings in the longitudinal bGH and littermate control cohort at 13 months were consistent with what was previously seen (43) with significantly increased intestinal length, small intestinal weight, and distinct morphological measurements (ie, muscle thickness in duodenum and ileum).

Excess Growth Hormone Alters Microbial Composition in an Age-dependent Manner

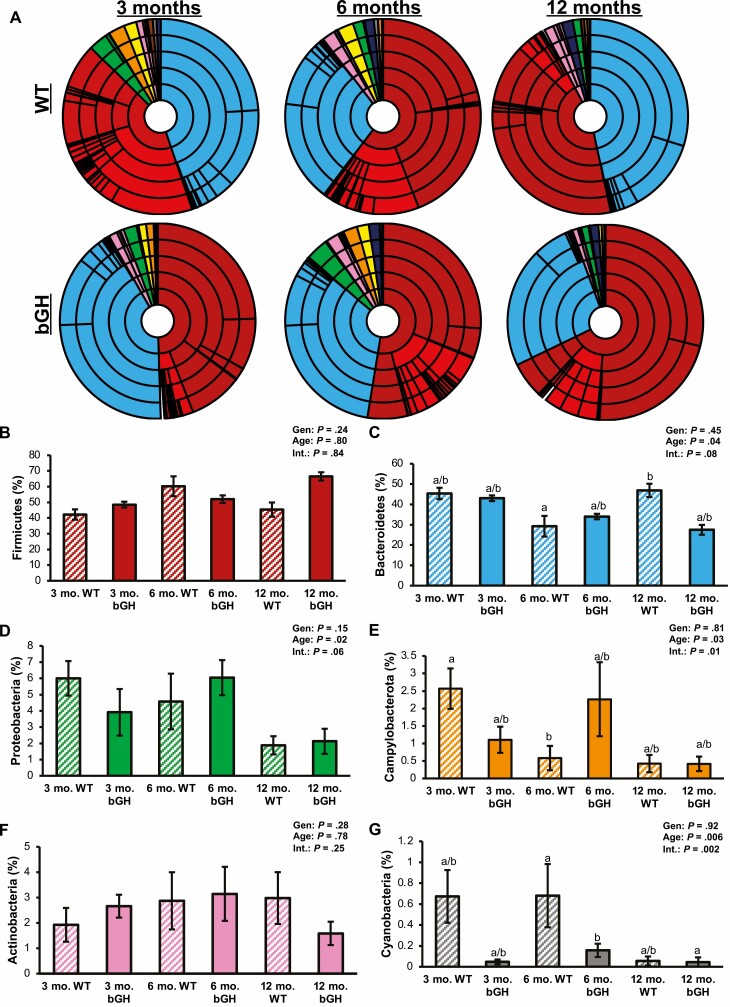

To determine the effect of excess GH on the longitudinal gut microbial community, abundance from the phylum to the genus level was first characterized in the same bGH mice and littermate controls at age 3, 6, and 12 months (Supplementary Table S2 and Fig. 3) (31). The majority of bacteria in the bGH and control microbiome at all 3 time points were found in the Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla; of which, Bacteroidetes was significantly explained by age and closely by interaction between genotype and age (see Supplementary Table S2) (31). Proteobacteria was significantly explained by age, whereas Cyanobacteria and Campylobacterota were significantly explained by both age and interaction between genotype and age.

Figure 3.

Microbial abundance in longitudinal bovine transgenic growth hormone (bGH) and wild-type (WT) microbiome (n = 7). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc Tukey analysis determined the effect of genotype (Gen), age, and interaction between genotype and age (Int) for phyla abundance. A, Microbial abundance at the phylum to genus level in bGH mice and WT controls at age 3, 6, and 12 months. Taxa colors are shared between A and B to G. B, Firmicutes (red) abundance in bGH and WT mice at age 3, 6, and 12 months. C, Bacteroidetes (blue) abundance in bGH and WT mice. D, Proteobacteria (green) in bGH and WT longitudinal microbiome. E, Campylobacterota (orange) abundance. F, Actinobacteria (pink) abundance. G, Cyanobacteria (gray) abundance.

Compared to controls, 3-month-old bGH mice had similar abundance in Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, slightly increased Actinobacteria, and decreased Proteobacteria and Campylobacterota abundance; none of these differences were significant. The bGH mice also had a similar Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (F:B) ratio (0.98 ± 0.37 compared to 1.14 ± 0.2). By age 6 months, all phyla had increased in abundance compared to controls except Firmicutes and Cyanobacteria, which decreased (Fig. 3). By age 12 months, bGH mice had trending increased Firmicutes and decreased Bacteroidetes with a significantly increased F:B ratio (2.27 ± 0.57) compared to controls (1.0 ± 0.33; P = .004). The qPCR results validated these findings (Supplementary Fig. S1) (31).

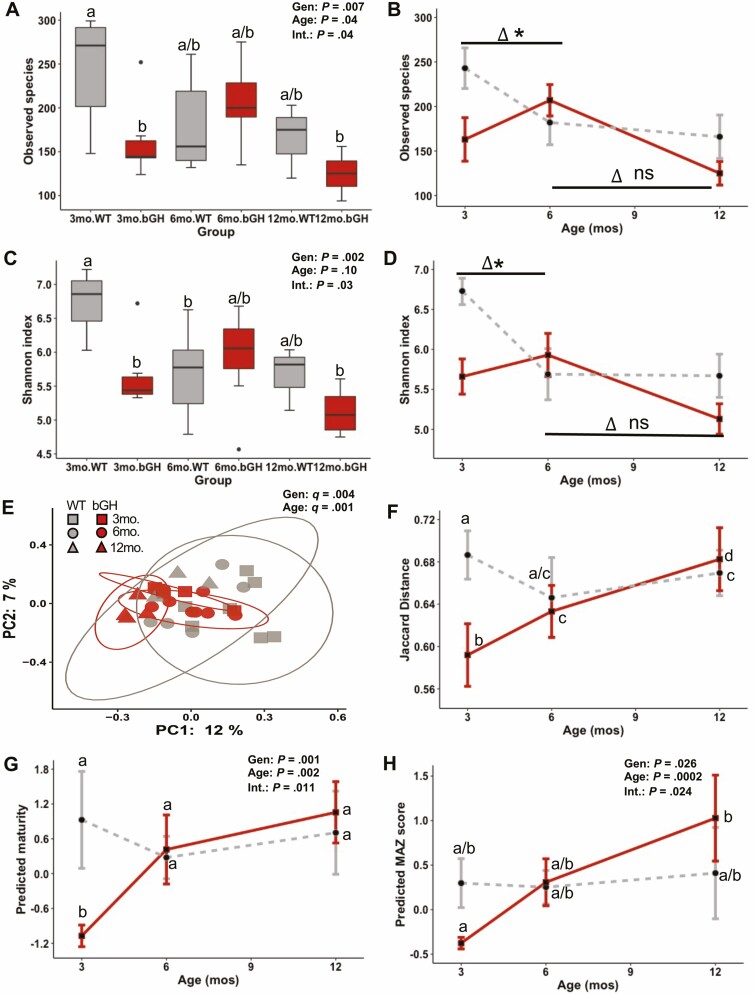

Diversity and Maturity of the Longitudinal Bovine Transgenic Growth Hormone Microbiome Significantly Differs From Controls

The diversity of the gut microbial community was assessed within an individual (α diversity, or microbial richness and evenness) and between individuals (β diversity). Microbial richness (or the number of different types of bacteria in the community) was significantly explained by genotype, age, and its interaction (Fig. 4A). Three-month-old bGH mice had significantly reduced microbial richness compared to controls, which appeared to normalize by age 6 months. Similar findings were seen in microbial evenness, or the proportionality of these bacterial populations in the community (Fig. 4C). Moreover, the rate of microbial richness and evenness were significantly altered in the bGH mice between age 3 and 6 months compared to controls (Fig. 4B and 4D). However, no significant difference was observed between age 6 and 12 months as both bGH mice and controls exhibited a similar decrease in microbial richness and evenness. β-Diversity measures the variation of the microbial community within and between groups. β-Diversity can be assessed using only the presence or absence of each species (Jaccard and unweighted UniFrac) or using the abundance of each species (Bray-Curtis and weighted UniFrac). These analyses also adjust according to phylogenetic relationship (weighted and unweighted UniFrac) or taxonomical (equal weight of all species) (Jaccard and Bray-Curtis). Overall, the bGH microbiome is significantly different relative to the WT microbiome in taxonomical and phylogenetic measurements (corrected P value [q] = .001, .003, .02, and .004). No significant differences were observed among age 3, 6, and 12 months within the WT group; however, bGH mice had a significantly different microbiome between ages 3 and 6 months (q = .02), 3 and 12 months (q = .02), and 6 and 12 months (q = .015) (Fig. 4E and 4F). Previous studies have highlighted a potential effect of the GH/IGF-1 axis on microbial maturity, or the expected development of the microbiome. Owing to the age-dependent changes in microbial abundance, richness, and evenness, maturity was investigated by assessing the changes in the microbial community relative to age-matched controls (Fig. 4G and 4H). A significant difference in predictive maturity and relative MAZ score was explained by genotype, age, and the interaction between genotype and age. In terms of predictive maturity, 3-month-old bGH mice had an immature microbiome compared to littermate controls. Both predictive maturity and MAZ score relative to controls showed a general increase in maturity in bGH mice over their lifespan with a significant difference in MAZ score between 3-month-old and 12-month-old bGH mice (Fig. 4G and 4H).

Figure 4.

Microbial diversity and maturity in the longitudinal bovine transgenic growth hormone (bGH) and wild-type (WT) microbiome. A to D, Microbial richness and evenness. Two-way analysis of variance and post hoc Tukey analysis determined the effect of genotype (Gen), age, and the interaction between genotype and age (Int) for all alpha diversity metrics. A, Microbial richness (observed species) in bGH and WT microbiome. B, Developmental differences between age 3, 6, and 12 months in observed species of the bGH microbiome and WT microbiome. *Significant 3 month to 6 month Δ difference between bGH and WT mice (P = .002 and Cohen d = 2.35). C, Shannon index in bGH microbiome and WT microbiome. D, Developmental differences among age 3, 6, and 12 months in Shannon index in bGH microbiome and WT microbiome. *Significant 3 month to 6 month Δ difference between bGH and WT mice (P = .02 and Cohen d = 1.72). Similar findings were observed in other metrics of α diversity (Faith phylogenetic diversity and Pielou evenness). E and F, Jaccard β diversity between bGH mice and littermate controls at age 3 (square), 6 (circle), and 12 months (triangle). E, β Diversity measured by Jaccard taxonomical metric in bGH mice and controls. B, Longitudinal differences between bGH mice and controls as measured by Jaccard β diversity. Similar patterns are seen in Bray Curtis and weighted UniFrac metrics. *Statistical significance q less than .05 (corrected P value). G and H, Microbial maturity in the bGH and WT microbiomes. G, Difference in predicted maturity (by weeks) in bGH mice and respective littermate controls. H, Difference in predicted maturity index z (MAZ) scores score between bGH mice and littermate controls. Both display a significant difference in development of maturity.

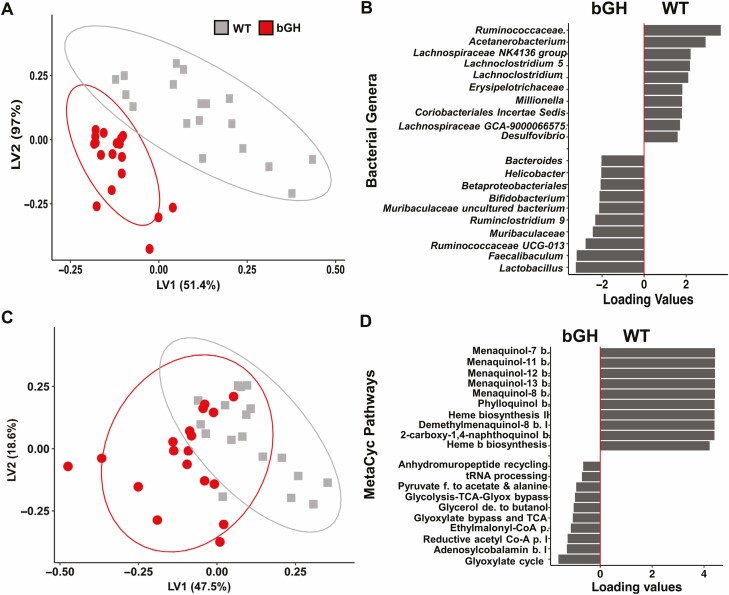

Unique Microbial Signature at Genus Level Observed in Bovine Transgenic Growth Hormone Mouse Line

Two multivariate analyses (PLS-DA and VIP score analysis) were performed to identify the specific microbial signatures that differentiated the 2 cohorts at each age point and across all time points (termed the longitudinal microbial signature). The PLS-DA showed a distinct separation between the bGH mice and controls across all 3 time points and at each time point (Supplementary Fig. S2 and Fig. 5) (31). At the genus level, bGH mice at age 3 and 12 months had a unique microbial signature compared to controls (see Supplementary Fig. S2) (31). It is important to note that the bGH mice also had a unique microbial signature at age 6 months that has been more thoroughly described in a previous study (28). Some microbes appeared to be influential both at age 3 and 12 months, including Lactobacillus, Parasutterella, Faecalibaculum, Lachnospiraceae, and Bifidobacterium (see Supplementary Fig. S2) (31). Others differed between the 3- and 12-month time points. For instance, increased Coriobacteriaceae and decreased Ruminococcaceae were observed at age 3 months, whereas the 12-month-old bGH microbiome had increased abundance of Peptostreptococcaceae and decreased abundance of Helicobacter and Bacteroides.

Figure 5.

Longitudinal signatures in bacteria and predictive metabolic pathways in bovine transgenic growth hormone (bGH) mice and controls. A, Unique microbial signature at the genus level quantified by partial-least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). bGH mice (red) and WT mice (gray) are distinctly different in the longitudinal microbial signature. B, Bacterial genera responsible for differentiating the bGH and wild-type (WT) mice across all 3 time points. C, Predictive metabolic function pathways quantified through MetaCyc abundance with PICRUSt and PLS-DA. bGH mice and WT mice have more overlap in predictive metabolic function longitudinally. D, Metabolic pathways predicted to differentiate the bGH microbiome across all 3 time points compared to the WT microbiome.

Across all 3 time points, many of the aforementioned bacteria were responsible for the differentiation of the bGH microbiome compared to controls (Fig. 5A and 5B). In particular, 12 microbes were identified by both the VIP and PLS-DA analyses. For instance, Lactobacillus (VIP 4.74), Ruminococcaceae UCG-013 (VIP 4.32), Faecalibaculum, and Bifidobacterium were increased in the longitudinal bGH microbiome. Meanwhile, several Lachnospiraceae genera (NK4A136 [VIP 1.443] and GCA-900066575 [VIP 1.71]), Acetanerobacterium (VIP 2.34), and Desulfovibrio (VIP 1.002) were all decreased in the longitudinal bGH microbiome compared to controls (see Fig. 5B).

Distinct Predictive Metabolic Pathways Associated With Increased Short Chain Fatty Acid and Decreased Heme B Biosynthesis

The previous analyses focused on the composition of the gut microbial community associated with excess GH action. Next, we wanted to determine what functional changes might result from the compositional changes that were observed. To further understand how excess GH influences the function of the microbial community, PICRUSt2 was used to predict the metabolic changes that result from the compositional changes that were observed. The longitudinal bGH microbiome exhibited a distinct predictive metabolic profile compared to controls (Fig. 5C). As identified through both VIP analysis and PLS-DA, metabolic pathways associated with fermentation to acetate and butanoate/butyrate, the glycoxylate cycle and bypass pathway, vitamin B12 and folate biosynthesis, and peptidoglycan biosynthesis were all upregulated in bGH mice (Fig. 5D and Table 1). Inversely, predictive metabolic pathways associated with heme B biosynthesis, menaquinol/phylloquinol biosynthesis, L-tyrosine and fucose degradation, and fatty acid salvage were decreased in bGH mice compared to controls (see Fig. 5D and Table 1).

Table 1.

Predicted metabolic pathways and enzymes to be upregulated and downregulated in the longitudinal bovine transgenic growth hormone (bGH) microbiome compared to control microbiome as identified through variable influence on projection (VIP) and partial least square-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) analyses from MetaCyc abundance, KEGG, and ECM metagenome databases

| Pathways upregulated in bGH mice | ||

|---|---|---|

| ID | Pathway/enzyme | VIP |

| Pathways identified through MetaCyc abundance | ||

| P461-PWY | Hexitol fermentation to lactate, ethanol, and acetate | 4.50 |

| PWY-922 | Mevalonate pathway I | 4.35 |

| PWY-5910 | Superpathway; geranylgeranyldiphosophate biosynthesis I (via mevalonate) | 3.93 |

| TCA-GLYOX-BYPASS | Superpathway of glycoxylate bypass and TCA | 3.51 |

| GLYCOLYSIS-TCA-GLYOX-BYPASS | Superpathway of glycolysis, pyruvate dehydrogenase, TCA, and glycoxylate bypass | 3.44 |

| LACTOSECAT-PWY | Lactose and galactose degradation I | 3.29 |

| PWY0-1338 | Lipopoylsaccharide biosynthesis and polymyxin resistance | 2.89 |

| P122-PWY | Heterolactic fermentation of pyruvate to ethanol and lactate | 2.72 |

| PWY-5507 | Adenosylcobalamin biosynthesis I (anaerobic) | 2.69 |

| P124-PWY | Bifidobacterium shunt, fermentation to acetate and lactate | 2.51 |

| TEICHOICACID-PWY | Poly(glycerol) phosphate wall teichoic acid biosynthesis | 2.29 |

| PWY-6396 | Superpathway of 2,3-butanediol biosynthesis | 2.04 |

| PWY-2941 | L-lysine biosynthesis II | 1.91 |

| PWY-6471 | Peptidoglycan biosynthesis IV | 1.77 |

| Pathways identified through KEGG pathway | ||

| K03970 | Phage shock protein B; type II toxin-antitoxin system | 3.51 |

| K02280 | Pilus assembly protein CpaC; type II secretion system and bacterial motility | 3.02 |

| K10241 | Cellobiose transporter; environmental information processing, saccharide, polyol and lipid transporters | 1.84 |

| K17242 | α-1,4-Digalacturonate transport system permease protein; ABC transporters and environmental information processing | 1.57 |

| K16928 | ABC transporters and vitamin B12 transporters | 1.83 |

| Enzymes identified through ECM metagenome | ||

| EC:2.3.3.9 | Malate synthase; participates in glyoxylate cycle | 6.16 |

| EC:1.6.5.2 | Chromate reductase or quinone dehydrogenase | 5.93 |

| EC:1.1.2.4 | D-lactate dehydrogenase | 5.95 |

| EC:2.7.7.82 | CMP-legionaminic acid synthase | 5.57 |

| EC:1.5.1.34 | Dihydropteridine reductase; involved in formyltetrahydrofolate biosynthesis | 1.23 |

| Pathways downregulated in bGH mice | ||

| Pathways identified through MetaCyc abundance | ||

| PWY-7094 | Fatty acid salvage pathway | 6.08 |

| PWY0-1415 | Superpathway of heme B biosynthesis form uroporphyrinogen-III | 5.61 |

| PWY-5918 | Superpathway of heme B biosynthesis from glutamate | 4.98 |

| PWY-5920 | Superpathway of heme B biosynthesis from glycine | 4.28 |

| PWY-7315 | dTDP-N-acetylthomosamine biosynthesis | 3.94 |

| HEME-BIOSYNTHESIS-II | Heme B biosynthesis (aerobic) | 3.68 |

| TYRFUMCAT-PWY | L-tyrosine degradation I | 3.56 |

| PWY0-1533 | Methylphosphonate degradation I | 3.01 |

| PWY-6641 | Superpathway of sulfolactate degradation | 2.10 |

| FUC-RHAMCAT-PWY | Superpathway of fucose and rhamnose degradation | 1.98 |

| FUCCAT-PWY | Fucose degradation | 1.83 |

| Pathways identified through KEGG pathways | ||

| K00231 | Protoporphyrinogen/coproporphyrinogen III oxidase; heme B biosynthesis | 1.55 |

| K00259 | Alanine dehydrogenase; alanine, glutamate metabolism | 1.82 |

| Enzymes identified through ECM metagenome | ||

| EC:1.3.3.4 | Protoporphyrinogen oxidase | 3.22 |

| EC:1.2.1.3 | Aldehyde or acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase | 2.87 |

| EC:1.4.1.1 | Alanine dehydrogenase | 1.19 |

Abbreviations: bGH, bovine transgenic growth hormone; VIP, variable influence on projection.

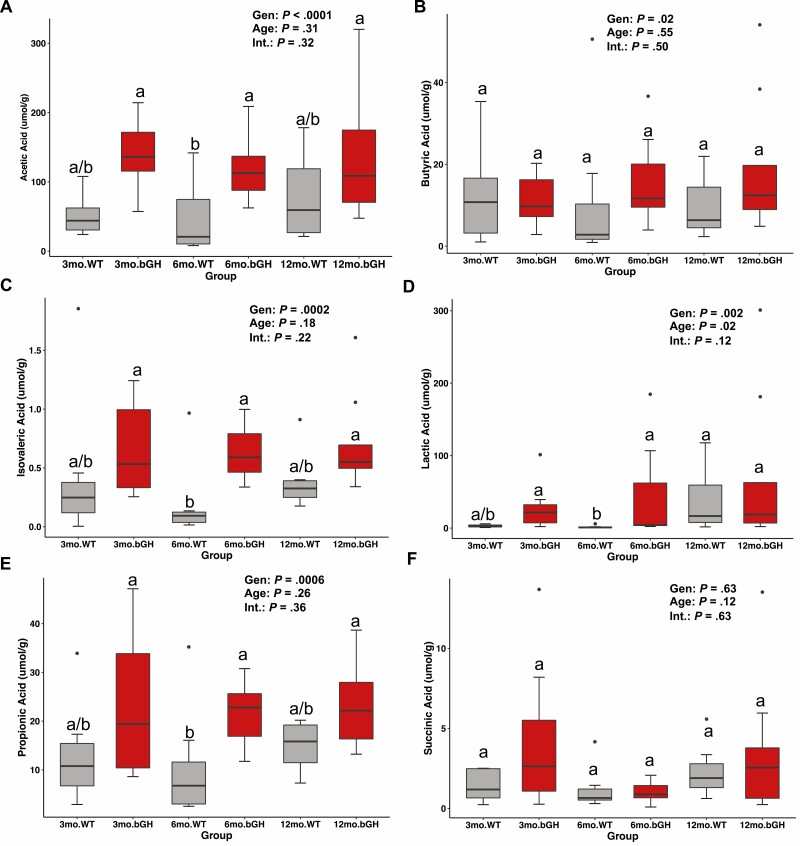

Fecal Short-Chain Fatty Acid Levels in Bovine Transgenic Growth Hormone Mice and Littermate Controls at Age 3, 6, and 12 to 13 Months

Microbial metabolites like SCFAs—independent of gut microbes—have been associated with altered metabolism and growth in the host (44). Moreover, our predictive metabolic function analyses in both this longitudinal study and previous research on 6-month-old bGH and GH–/– mice suggest a potential association between GH and SCFAs, specifically acetate, butyrate, and propionate. To confirm the predictive metabolic analysis, we quantified SCFA levels in feces of bGH and WT mice at age 3, 6, and 12 to 13 months (Fig. 6). Overall, there is a trending increase in SCFA levels in bGH mice across all 3 time points compared to controls. Acetic, butyric, isovaleric, lactic, and propionic acids were all significantly explained by genotype (see Fig. 6). Moreover, significant increases in acetic, isovaleric, lactic, and propionic acid levels were observed in 6-month-old bGH mice compared to WT mice (see Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Fecal short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in bovine transgenic growth hormone (bGH) mice and respective littermate controls at age 3, 6, and 12 to 13 months. A, Acetic acid levels. Significantly explained by genotype (P < .0001 and ω p2 = .333). B, Butyric acid levels. Significantly explained by genotype (P = .02 and ω p2 = .102). C, Isovaleric acid levels. Significantly explained by genotype. D, Lactic acid levels. Significantly explained by genotype. C, Isovaleric acid levels. Significantly explained by genotype (P = .0002 and ω p2 = .272). D, Lactic acid levels. Significantly explained by genotype (P = .002 and ω p2 = .205). E, Propionic acid levels. Significantly explained by genotype (P = .0006 and ω p2 = .239). F, Succinic acid levels. Different letters indicate significant differences between groups (P < .05). Single dots indicate outliers.

Furthermore, we examined the relationship between fecal SCFA levels and the microbial community. There was a trending moderate negative correlation between acetic acid and lactic acid levels and microbial richness and evenness, respectively (Table 2A). Next, we explored the relationship between specific microbes found in the bGH and WT microbiome that were differentiated by fecal SCFA levels via multinomial regression using qiime2 songbird (see Table 2A) (36). Specifically, Lactobacillales and several Lactobacillus species (including Lactobacillus johnsonii), Clostridia UCG-014, and Barnesiella were all positively associated with fecal SCFAs, whereas several Lachnospiraceae species (including Lachnospiraceae NK4A136) along with Eubacterium, Peptostreptococcaceae, and Burkholderiales had a negative association with fecal SCFAs. There was a moderate to strong positive correlation between Clostridia UCG-014 and lactic acid with trending positive correlation with acetic and succinic acid. There was also a moderate to strong positive correlation between Lactobacillales family and acetic acid, trending with isovaleric acid, succinic acid, and lactic acid with a similar trend seen with Lactobacillus and acetic, isovaleric, lactic, and propionic acid. A trending moderate positive correlation was observed between Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 and butyric acid (see Table 2A).

Table 2.

Correlation analyses of fecal short-chain fatty acid levels

| Fecal SCFAs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor/Outcome | Acetic acid | Butyric acid | Isovaleric acid | Lactic acid | Propionic acid | Succinic acid |

| Microbial richness (Faith’s PD) | –0.30 (P = .08) |

0.03 (P = .85) |

–0.17 (P = .32) |

–0.35 (P = .03) |

–0.15 (P = .37) |

–0.07 (P = .67) |

| Microbial evenness (Pielou’s evenness) |

–0.27 (P = .11) |

0.14 (P = .41) |

–0.11 (P = .52) |

–0.24 (P = .17) |

–0.19 (P = .27) |

–0.16 (P = .36) |

| Clostrida UCG-014 | 0.42 (P = .011) |

0.04 (P = .82) |

0.29 (P = .08) |

0.57

(P = .0003) |

0.26 (P = .13) |

0.39 (P = .02) |

| Barnesiella | –0.05 (P = .77) |

0.17 (P = .50) |

0.08 (P = .64) |

0.02 (P = .89) |

0.16 (P = .35) |

0.24 (P = .15) |

| Burkholderiales | –0.01 (P = .93) |

0.22 (P = .20) |

0.17 (P = .32) |

–0.13 (P = .46) |

0.14 (P = .41) |

–0.13 (P = .46) |

| Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group | –0.200 (P = .24) |

0.32 (P = .05) |

–0.11 (P = .52) |

–0.17 (P = .32) |

0.11 (P = .52) |

0.15 (P = .37) |

| Lactobacillales |

0.58

(P = .0002) |

–0.06 (P = .74) |

0.37 (P = .02) |

0.65

(P = 1.3e-05) |

0.27 (P = .10) |

0.76

(P = 8.17e-8) |

| Lactobacillus | 0.32 (P = .06) |

–0.0113 (P = .95) |

0.311 (P = .06) |

0.28 (P = .10) |

0.33 (P = .05) |

0.21 (P = .22) |

| Peptostreptococcacaea | –0.21 (P = .22) |

–0.07 (P = .68) |

–0.23 (P = .17) |

–0.07 (P = .67) |

–0.15 (P = .37) |

–0.17 (P = .33) |

| P122.PWY (Heterolactic f.) | 0.35 (P = .04) |

0.02 (P = .90) |

0.200 (P = .24) |

0.26 (P = .12) |

0.31 (P = .06) |

0.24 (P = .15) |

| P461.PWY (Hexitol f. to lactate, ethanol, formate and acetate) | 0.29 (P = .09) |

0.12 (P = .47) |

0.31 (P = .06) |

0.17 (P = .31) |

0.22 (P = .20) |

0.11 (P = .53) |

| P124.PWY (Bifidobacterium shunt [acetate and lactate b.]) | 0.31 (P = .06) |

0.005 (P = .97) |

0.17 (P = .31) |

0.25 (P = .14) |

0.28 (P = .09) |

0.21 (P = .22) |

| PWY.6876 (isopropanol b.) | –0.22 (P = .19) |

–0.18 (P = .29) |

–0.05 (P = .77) |

–0.19 (P = .27) |

–0.23 (P = .18) |

–0.35 (P = .04) |

| PWY.7003 (Glycerol d. to butanol) | –0.04 (P = .83) |

0.19 (P = .27) |

0.12 (P = .49) |

–0.15 (P = .37) |

0.10 (P = .55) |

–0.14 (P = .41) |

| CODH.PWY (reductive acetyl coenzyme A pathway I) | –0.074 (P = .67) |

0.23 (P = .18) |

0.13 (P = .44) |

–0.16 (P = .35) |

0.12 (P = .49) |

–0.11 (P = .53) |

| Fecal weight | 0.39 (P = .02) |

0.15 (P = .38) |

0.34 (P = .04) |

0.46

(P = .005) |

0.40 (P = .01) |

0.03 (P = .88) |

| Fat % | –0.29 (P = .09) |

0.04 (P = .81) |

–0.11 (P = .53) |

–0.40 (P = .02) |

–0.02 (P = .91) |

0.18 (P = .30) |

| Lean mass |

0.49

(P = .008) |

0.21 (P = .24) |

0.39 (P = .02) |

0.50

(P = .002) |

0.42 (P = .01) |

0.09 (P = .62) |

First two sections shows correlations between fecal SCFAs and the microbial community (including microbial richness and evenness) and specific microbes identified through multinominal regression. Third section shows correlations between fecal SCFAs and predictive SCFA biosynthesis pathways associated with the longitudinal bGH microbiome as identified through PICRUSt2 and PLS-DA analysis. Last section shows correlations between fecal SCFAs and the mouse intestinal and metabolic phenotype (eg, body composition and fecal weight). Owing to the number of correlations made for each outcome (microbiome), statistical significance was set at .008 rather than .05 using a Bonferroni correction. Correlations statistically significant with P value less than .008 are shown in bold.

Abbreviations: b, biosynthesis; bGH, bovine transgenic growth hormone; d, degradation; f, fermentation; SCFA, short-chain fatty acid.

We next assessed correlations between fecal SCFAs and predictive SCFA biosynthesis pathways, focusing specifically on several distinct predictive MetaCyc abundance SCFA pathways highlighted in the previous section (Table 2B). There was a trending positive correlation between heterolactic fermentation pathway (which is associated with Firmicutes and Lactobacillus and involved in ethanol and lactic acid fermentation) and acetic, lactic, and propionic acid. Similarly, a trending positive correlation was also observed between P461.PWY (hexitol fermentation) and acetic acid and isovaleric acid, and P124.PWY (Bifidobacterium shunt involved in acetic and lactic acid biosynthesis) and acetic, lactic, and propionic acid. Finally, we assessed correlations between metabolic and intestinal measurements of our longitudinal cohort of bGH and WT mice (ie, body composition) (Table 2C). Interestingly, body composition (ie, fat mass and lean mass) correlated with several SCFA metabolites. There was a moderate negative correlation between body fat percentage and lactic acid. Inversely, there were moderate positive correlations between lean mass and acetic acid and lactic acid and a trending positive correlation between lean mass and isovaleric acid and propionic acid. There was a moderate positive correlation between fecal weight and acetic, isovaleric, lactic, and propionic acid levels.

Discussion

This study is the first to track the effect of chronic, excess GH action on the gut microbiome in adult mice over time in the context of metabolic and intestinal changes and accelerated aging. In terms of overall metabolic phenotype, the bGH mice had increased body weight and lean and fluid mass throughout their life and exhibited an age-dependent decrease in adiposity as has been previously reported (17, 18, 20). Moreover, bGH mice had a distinct intestinal phenotype with impaired fat absorption and increased fecal output. Along with significant differences observed in metabolism and intestinal homeostasis, bGH mice had a significantly altered gut microbiota at age 3, 6, and 12 months compared to controls with age-dependent changes seen in microbial abundance, richness, evenness, and maturity. Trends in microbial maturity were significantly explained by genotype, age, and the interaction between genotype and age. Notably, several bacterial genera and predicted metabolic pathways differentiated bGH mice compared to controls across all 3 time points, suggesting a distinct longitudinal signature. For instance, the abundance of Lactobacillus, Lachnospiraceae, Betaproteobacteriadales, Faecalibaculum, and Bifidobacterium were increased in bGH mice, whereas several Lachnospiraceae (NK4A136 included) and Desulfovibrio were decreased. Likewise, shared predictive metabolic pathways involved in SCFA production, vitamin B12, folate biosynthesis, peptidoglycan biosynthesis (along with antibiotic resistance/virulence factors), and glycoxylate cycle were upregulated in bGH mice, whereas pathways involved in heme B and menaquinol biosynthesis and fatty acid salvage were downregulated in bGH mice across all 3 time points compared to controls. Moreover, fecal SCFA levels were significantly explained by genotype with an overall trending increase observed in bGH mice. Several SCFAs were positively correlated with Lactobacillus, Clostridia UCG-014, and negatively correlated with Lachnospiraceae (except for butyric acid) and Peptostreptococcaceae. These findings suggest that excess GH action is associated with certain microbes and thus, may affect the overall longitudinal microbial community and predictive metabolic function.

In terms of intestinal phenotype, this is the second study to record intestinal measurements throughout the lifespan of bGH mice. Previous studies have examined intestinal morphology and gross anatomy in young bGH mice (28, 45-48) or investigated GH administration to resolve intestinal dysfunction (such as inflammatory bowel disease or short bowel syndrome) (49-51). Recently, our laboratory characterized the intestinal gross anatomy and morphology in several time points of GHR–/– mice and bGH mice, specifically in male and female bGH mice from ages 6 weeks to 13 months (43). This previous characterization observed significantly increased intestinal length, weight, and circumference across the lifespan of bGH mice compared to controls with increased small intestinal morphology along with decreased colonic crypt depth noted later in life (43). Interestingly, colonic metabolism has been associated with maintaining a healthy luminal environment for commensal microbes, whereas hyperplasia has been associated with an increased presence of facultative anaerobes and dysbiosis (52).

Our bGH mice had consistently decreased or impaired intestinal fat absorption at age 3, 6, and 12 months. Several studies have shown that GH administration decreases intestinal permeability and improves fat and macronutrient absorption (53-55). Yet, it is important to note that those studies examined GH from an acute and therapeutic perspective rather than chronically increased GH levels seen in our bGH mice. Fat absorption is closely tied to intestinal permeability (56), which has been shown to decrease with GH (57). This finding potentially explains the metabolic, age-dependent change in fat accumulation and may have an important role in maintaining the intestinal environment that influences the microbial community (56). Furthermore, this finding poses interesting questions about the intestinal function, including bile acid synthesis and reabsorption and motility/transit time. Previous preclinical and clinical studies suggest an association with GH and altered intestinal motility and bile metabolism. To that end, hypophysectomized rats have decreased bile acid excretion, which is normalized on GH replacement (58). Individuals with acromegaly independent of octreotide treatment have been shown to have decreased gut motility/increased transit time (59). Thomas and colleagues (60) further demonstrated that individuals with acromegaly who are receiving octreotide not only have increased gut transit time but also increased fecal gram-positive anaerobes, and increased cholyglycine hydrolase and 7-α-dehydroxyase activity. Although not measured in our present study, bile acids are closely linked to fat digestion/absorption, so changes to bile acid synthesis/reabsorption may offer another explanation for the reduced fat absorption in bGH mice. Additional studies on bile acid metabolism, pancreatic enzymes, and gut transit time in bGH mice are warranted.

This study is the first to report on the longitudinal changes on GH-associated microbial abundance in mice. The age-dependent differences in microbial abundance at the phylum level may explain some of the discrepancies seen between studies that previously characterized the microbiome in mouse lines with altered GH action (ie, GH–/– mice, bGH mice, and Ames mice). For instance, the F:B ratio was seen to be shifted in the same direction between Ames mice at age 2 months and in GH–/– mice and bGH mice at age 6 months (27, 28). Yet, the longitudinal bGH microbiome displayed shifts in F:B ratio in an age-dependent manner. That is, compared to controls, the ratio in bGH mice was similar at age 3 months, decreased at age 6 months (same direction observed in mouse lines with GH deficiency), and significantly increased at age 12 months (the opposite direction of mouse lines with GH deficiency). This finding then suggests that the ratio may be influenced by GH more so later in life (in the context of aging) and necessitates future experiments to examine microbial abundance in GH-deficient or -resistant mouse lines at older ages. This delineation would be especially notable since the F:B ratio has been associated with metabolism, energy harvest, and longevity (61, 62). In particular, a decreased F:B ratio has been associated with SCFA production (63); despite their increased F:B ratio at age 12 months, bGH mice have no significant change in SCFA levels.

The longitudinal signature with increased Lactobacillus, Parasutterella (Burkholderiales), and decreased Lachnospiraceae corroborates other studies that have associated certain microbes with the GH/IGF-1 axis (27, 28). For instance, Burkholderiales (Parasutterella and Sutterella) has been positively correlated with GH and IGF-1 (7, 28), whereas Lachnospiraceae has been negatively correlated with GH as seen in 3 distinct mouse lines with altered GH action (27, 28). Bifidobacterium has also been correlated with the GH/IGF-1 axis, associated with increased IGF-1 and leptin, and decreased ghrelin (64-66). Moreover, Lactobacillus has not only been positively associated with GH action (27, 28) but administration of several Lactobacillus species has been shown to increase IGF-1 levels or growth factors across several animal models (eg, mice, pigs, and Drosophila) (22, 64, 67-70). Collectively, these findings suggest that GH consistently influences the growth of certain microbes over a long period of time.

Our findings also demonstrate interesting age-dependent changes in the microbial community, exploring a relationship with premature aging (7, 28). Previous studies have observed age-associated complications in bGH mice by age 12 months, including cardiac fibrosis, scoliosis, and increased incidence of tumors (19, 20). In this study, 2 bGH mice died before age 13 months, and at time of dissection, 2 out of the 3 13-month-old bGH mice had tumors, whereas there was no incidence of tumors in the littermate controls. Aging and age-associated comorbidities have traditionally been associated with dysbiosis or a lack of microbial diversity (richness and evenness) (62). The gut microbiomes of long-lived individuals (semi-supercentenarians) also have decreased microbial richness (12), although these results are not consistent across all studies (71) and may be complicated by internal factors such as underlying health status and external environmental challenges (72). Our data support a more complex perspective among premature aging, microbial diversity, and maturity. Although our 12-month-old bGH mice do exhibit a lack of diversity at the phylum level and a shift in F:B ratio, our mice do not have significantly decreased microbial richness or evenness later in life compared to controls, probably due to an increased number of microbial populations within the Firmicutes phylum. Our bGH mice also have a trending increase in relative maturity (MAZ score) by age 12 months. Inversely, early in life, bGH mice exhibit significantly decreased maturity compared to controls. This low predictive maturity at age 3 months is a potential driving factor for the perceived increase in maturity (especially compared to the relative maturity plateau in the controls from age 3 to 12 months). Our bGH mice also have significantly decreased microbial richness and evenness at age 3 months; interestingly, this finding is similar to the infant microbiome, which has decreased diversity and is typically dominated by a few microbes (including Bifidobacterium) (73). These findings suggest that excess GH—in the context of intestinal and metabolic changes—may promote the presence of certain microbes that create a niche in the intestines early in life and affect the longitudinal microbial community. Collectively, these findings validate future studies to examine the development of the intestinal environment and microbiome in bGH mice.

Excess GH appears to consistently regulate the predictive microbial metabolic pathways associated with SCFA production, vitamin (B12, menaquinol, and folate) biosynthesis, and heme B biosynthesis, along with others associated with potential virulence factors and antibiotic resistance. Quantification of fecal SCFA levels in our bGH mice across all 3 time points further confirm this association. In particular, excess GH appears to affect fecal acetate, propionate, and lactate levels. Importantly, SCFA production has been associated with mediating crosstalk between the gut microbiota and the GH/IGF-1 axis in previous studies. That is, SCFA levels have been shown to increase IGF-1 levels, alter ghrelin and leptin levels, and inhibit GH production in bovine anterior pituitary cells in culture (23, 74-77). Acetate, which has been associated with insulin resistance and is important in lipid metabolism, and butyrate, which alters lipid metabolism and acts as a fuel for colonocytes (5, 44, 78), have been positively associated with GH in our previous research on bGH and GH–/– mice at age 6 months (28). Propionate appears to be gluconeogenic in the colonocytes and hepatocytes and, along with butyrate, affects lipogenesis and regulatory T-cell response and inhibits proinflammatory cytokine production (5, 69, 70).

Although this study was the first to demonstrate that excess GH affects the longitudinal microbiome in adult mice, there are several questions that remain unanswered. First, we chose to focus on the progression of the adult gut microbiome (age 3, 6, and 12 months) in male mice from a young, healthy adult age to middle age in the WT mice and a premature “elderly” age for the bGH mice. This choice discounts the well-known differences seen between sexes and the importance of the early, developing microbiome (before age 3 months) (79-82). Subsequent studies are needed to examine the effect of GH on the longitudinal changes in the gut microbiome in females and at earlier ages to capture the developing microbiome before adulthood. Another limitation for this study is the small sample size of the longitudinal cohort for bGH and WT mice (partially due to attrition), which is important to keep in mind when interpreting results from predictive modeling (such as microbial maturity) and concern for overfitting models or discounting potential confounding variables, including health status or cage effect. Our bGH mice exhibit accelerated aging and aging comorbidities, including metabolic dysfunction (17-20). While this replicates the clinical population of acromegaly and proves to be an important model for studying systemic disease, type 2 diabetes, metabolic dysfunction, and accelerated aging, this phenotype confounds the perspective of GH at physiological levels on the gut microbiome. Subsequent studies to characterize the longitudinal gut microbiome in mouse lines with altered GH action (especially decreased GH action like GH–/– or GHR–/– mice) and with a more robust sample size would further confirm a GH association and investigate GH’s role in microbial maturation and diversity.

Notably, 3 studies to date have examined the gut microbiome in clinical populations of acromegaly. Hacioglu and colleagues characterized the gut microbiome in individuals with newly diagnosed acromegaly with additional comorbidities (eg, diabetes and hypertension) compared to age-, sex-, and body mass index–matched healthy controls (with no incidence of comorbidities); meanwhile, a subsequent study from this team (Sahin et al) and a separate study by Lin et al characterized the gut microbiome in individuals with newly diagnosed or recurrent acromegaly with no comorbidities compared to healthy controls (83-85). Similar to our mouse studies, there is a significant difference in β diversity between individuals with acromegaly and healthy controls (83, 84). All 3 clinical studies show an altered F:B ratio in individuals with acromegaly with an increase in Bacteroidetes; this decreased F:B ratio has been seen in Ames mice (27) and GH–/– mice and bGH mice at age 6 months (28). Both Lin et al and Hacioglu et al (83, 84) importantly show a decrease in microbial richness and evenness, which is interesting since this finding was seen in our 3-month-old bGH group. Finally, there are genus-specific differences among our study and the 3 clinical acromegaly studies; however, Sutterella/Burkholderiales, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus have all been identified in individuals with acromegaly and our bGH mice. These studies have established the foundation for our understanding of the gut microbiome in patients with acromegaly with and without comorbidities, and similarities in findings between our study and these clinical studies demonstrate translational potential. Additional studies on the gut microbiome in clinical populations of altered GH are needed to understand the translatability and potential mechanisms behind this relationship.

In summary, this study is the first to examine the longitudinal microbial profile in a mouse line with excess GH action and a distinct metabolic, intestinal, and aging phenotype. Moreover, this study is the first to report longitudinal changes in intestinal fat absorption and fecal output. Importantly, bGH mice have age-dependent shifts in microbial abundance, richness, evenness, and maturity. Longitudinally, bGH mice have a unique microbial signature and predictive metabolic function. Importantly, bGH mice have impaired intestinal fat absorption, increased fecal output, and altered gross anatomy and morphology; all of which may contribute to the growth of certain bacteria and thus, foster a longitudinal microbial community and modulate metabolic functions like SCFA, folate, vitamin B12, heme B, menaquinol, and peptidoglycan biosynthesis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge several institutions and individuals: 1. Drs Trina Knotts and Helen Raybould (Microbiome and Host Response core at UC, Davis) and Dr William Broach (Ohio University Genomics Facility) for consultation on microbiome analysis; 2. Dr Patrick Tso and MMPC core at University of Cincinnati for their assistance in the intestinal fat absorption; 3. Julie Buckley and the Ohio University Histology core for assistance in preparing intestinal samples; and 4. Dr Naseer Sangwan and the Cleveland Clinic Center for Microbiome and Human Health for assistance in quantification of fecal SCFAs and additional insight on metabolomic analysis.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- bGH

bovine transgenic growth hormone

- F:B

Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio

- GH

growth hormone

- GHR–/–

growth hormone receptor knockout

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor-1

- MAZ

maturity index z score

- MMPC

Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PLS-DA

partial least square-discriminant analysis

- QIIME

Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- rRNA

ribosomal RNA

- SCFA

short-chain fatty acid

- SEM

standard error of the mean; UC, University of California

- WT

wild-type

Contributor Information

Elizabeth A Jensen, Translational Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program, Graduate College, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA.

Jonathan A Young, Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Edison Biotechnology Institute, Konneker Research Labs, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA.

Zachary Jackson, Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA.

Joshua Busken, Edison Biotechnology Institute, Konneker Research Labs, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA.

Jaycie Kuhn, Edison Biotechnology Institute, Konneker Research Labs, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; The Diabetes Institute, Parks Hall, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA.

Maria Onusko, The Diabetes Institute, Parks Hall, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Department of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA.

Ronan K Carroll, Department of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Molecular and Cellular Biology Program, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Infectious and Tropical Diseases Institute, Irvine Hall, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA.

Edward O List, Translational Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program, Graduate College, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Edison Biotechnology Institute, Konneker Research Labs, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; The Diabetes Institute, Parks Hall, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA.

J Mark Brown, Department of Cardiovascular & Metabolic Sciences, and The Center for Microbiome & Human Health, Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland, Ohio 44195, USA.

John J Kopchick, Translational Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program, Graduate College, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Edison Biotechnology Institute, Konneker Research Labs, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; The Diabetes Institute, Parks Hall, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Molecular and Cellular Biology Program, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Department of Biomedical Sciences, Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, 45701, USA.

Erin R Murphy, Translational Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program, Graduate College, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Molecular and Cellular Biology Program, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Infectious and Tropical Diseases Institute, Irvine Hall, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Department of Biomedical Sciences, Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, 45701, USA.

Darlene E Berryman, Translational Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program, Graduate College, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Edison Biotechnology Institute, Konneker Research Labs, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; The Diabetes Institute, Parks Hall, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Molecular and Cellular Biology Program, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, USA; Department of Biomedical Sciences, Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, 45701, USA.

Financial Support

This work was partially funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH grant No. AG059779), by the John J. Kopchick Molecular and Cellular Biology/Translational Biomedical Sciences Research Fellowship, and a fellowship from Osteopathic Heritage Foundations, Dual Degree Program at Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine. Research was supported by the NIH (grant No. U24-DK092993 to the Microbiome and Host Response core of Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center at UC, Davis).

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Some data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are publicly available at NCBI Bioproject PRJNA828021. All other data generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- 1. Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(8):e1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bäckhed F, Fraser CM, Ringel Y, et al. Defining a healthy human gut microbiome: current concepts, future directions, and clinical applications. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12(5):611-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ursell LK, Metcalf JL, Parfrey LW, Knight R. Defining the human microbiome. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(Suppl 1):S38-S44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sommer F, Bäckhed F. The gut microbiota—masters of host development and physiology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11(4):227-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rastelli M, Cani PD, Knauf C. The gut microbiome influences host endocrine functions. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(5):1271-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blanton LV, Barratt MJ, Charbonneau MR, Ahmed T, Gordon JI. Childhood undernutrition, the gut microbiota, and microbiota-directed therapeutics. Science. 2016;352(6293):1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen J, Toyomasu Y, Hayashi Y, et al. Altered gut microbiota in female mice with persistent low body weights following removal of post-weaning chronic dietary restriction. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Subramanian S, Huq S, Yatsunenko T, et al. Persistent gut microbiota immaturity in malnourished Bangladeshi children. Nature. 2014;510(7505):417-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tidjani Alou M, Million M, Traore SI, et al. Gut bacteria missing in severe acute malnutrition, can we identify potential probiotics by culturomics? Front Microbiol. 2017;8:899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mouzaki M, Loomba R. Insights into the evolving role of the gut microbiome in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: rationale and prospects for therapeutic intervention. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819858470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buford TW, Carter CS, VanDerPol WJ, et al. Composition and richness of the serum microbiome differ by age and link to systemic inflammation. Geroscience. 2018;40(3):257-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Biagi E, Rampelli S, Turroni S, Quercia S, Candela M, Brigidi P. The gut microbiota of centenarians: signatures of longevity in the gut microbiota profile. Mech Ageing Dev. 2017;165(Pt B):180-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kong F, Hua Y, Zeng B, Ning R, Li Y, Zhao J. Gut microbiota signatures of longevity. Curr Biol. 2016;26(18):R832-R833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Junnila RK, List EO, Berryman DE, Murrey JW, Kopchick JJ. The GH/IGF-1 axis in ageing and longevity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9(6):366-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhou Y, Xu BC, Maheshwari HG, et al. A mammalian model for Laron syndrome produced by targeted disruption of the mouse growth hormone receptor/binding protein gene (the Laron mouse). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(24):13215-13220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bartke A, Westbrook R. Metabolic characteristics of long-lived mice. Front Genet. 2012;3:288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Palmer AJ, Chung MY, List EO, et al. Age-related changes in body composition of bovine growth hormone transgenic mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150(3):1353-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berryman DE, List EO, Coschigano KT, Behar K, Kim JK, Kopchick JJ. Comparing adiposity profiles in three mouse models with altered GH signaling. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2004;14(4):309-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pendergrass WR, Li Y, Jiang D, Wolf NS. Decrease in cellular replicative potential in “giant” mice transfected with the bovine growth hormone gene correlates to shortened life span. J Cell Physiol. 1993;156(1):96-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jara A, Benner CM, Sim D, et al. Elevated systolic blood pressure in male GH transgenic mice is age dependent. Endocrinology. 2014;155(3):975-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Householder LA, Comisford R, Duran-Ortiz S, et al. Increased fibrosis: a novel means by which GH influences white adipose tissue function. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2018;39:45-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schwarzer M, Makki K, Storelli G, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum strain maintains growth of infant mice during chronic undernutrition. Science. 2016;351(6275):854-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yan J, Herzog JW, Tsang K, et al. Gut microbiota induce IGF-1 and promote bone formation and growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(47):E7554-E7563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yan J, Takakura A, Zandi-Nejad K, Charles JF. Mechanisms of gut microbiota-mediated bone remodeling. Gut Microbes. 2018;9(1):84-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Novince CM, Whittow CR, Aartun JD, et al. Commensal gut microbiota immunomodulatory actions in bone marrow and liver have catabolic effects on skeletal homeostasis in health. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lu J, Lu L, Yu Y, Cluette-Brown J, Martin CR, Claud EC. Effects of intestinal microbiota on brain development in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wiesenborn DS, Gálvez EJC, Spinel L, et al. The role of Ames dwarfism and calorie restriction on gut microbiota. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(7):e1-e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jensen EA, Young JA, Jackson Z, et al. Growth hormone deficiency and excess alter the gut microbiome in adult male mice. Endocrinology. 2020;161(4):bqaa026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jandacek RJ, Heubi JE, Tso P. A novel, noninvasive method for the measurement of intestinal fat absorption. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(1):139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4516-4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jensen EA. Supplementary data for “Excess growth hormone alters the mouse gut microbiome in an age-dependent manner.” Figshare. Deposited 20 January 2022. 10.6084/m9.figshare.18782999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32. Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7(5):335-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(8):852-857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D590-D596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zheng X, Qiu Y, Zhong W, et al. A targeted metabolomic protocol for short-chain fatty acids and branched-chain amino acids. Metabolomics. 2013;9(4):818-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morton JT, Marotz C, Washburne A, et al. Establishing microbial composition measurement standards with reference frames. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rai SN, Qian C, Pan J, et al. Microbiome data analysis with applications to pre-clinical studies using QIIME2: Statistical considerations. Genes Dis. 2021;8(2):215-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol. 2013;4:863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Routledge Academic; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Korkmaz S, Göksülük D, Zararsız G. MVN: an R package for assessing multivariate normality. R J. 2014;6(2):151-162. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D; R Core Team. Data from: {nlme}: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. 2018. Accessed April 2022. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme

- 42. Barton K. Data from: MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference. 2018. Accessed April 2022. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn

- 43. Jensen EA, Young JA, Kuhn J, et al. Growth hormone alters gross anatomy and morphology of the small and large intestines in age- and sex-dependent manners. Pituitary. 2022;25(1):116-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Morrison DJ, Preston T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes. 2016;7(3):189-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ohneda K, Ulshen MH, Fuller CR, D’Ercole AJ, Lund PK. Enhanced growth of small bowel in transgenic mice expressing human insulin-like growth factor I. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(2):444-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Williams KL, Fuller CR, Dieleman LA, et al. Enhanced survival and mucosal repair after dextran sodium sulfate–induced colitis in transgenic mice that overexpress growth hormone. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(4):925-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen T, Zheng F, Tao J, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 contributes to mucosal repair by β-arrestin2–mediated extracellular signal-related kinase signaling in experimental colitis. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(9):2441-2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Michaylira CZ, Ramocki NM, Simmons JG, et al. Haplotype insufficiency for suppressor of cytokine signaling-2 enhances intestinal growth and promotes polyp formation in growth hormone-transgenic mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147(4):1632-1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen Y, Tseng SH, Yao CL, Li C, Tsai YH. Distinct effects of growth hormone and glutamine on activation of intestinal stem cells. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2018;42(3):642-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Scopa CD, Koureleas S, Tsamandas AC, et al. Beneficial effects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor I on intestinal bacterial translocation, endotoxemia, and apoptosis in experimentally jaundiced rats. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190(4):423-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]