Abstract

Interdisciplinary research at the interface of chemistry, physiology, and biomedicine have uncovered pivotal roles of nitric oxide (NO) as a signaling molecule that regulates vascular tone, platelet aggregation, and other pathways relevant to human health and disease. Heme is central to physiological NO signaling, serving as the active site for canonical NO biosynthesis in nitric oxide synthase (NOS) enzymes and as the highly selective NO binding site in the soluble guanylyl cyclase receptor. Outside of the primary NOS-dependent biosynthetic pathway, other hemoproteins, including hemoglobin and myoglobin, generate NO via the reduction of nitrite. This auxiliary hemoprotein reaction unlocks a “second axis” of NO signaling in which nitrite serves as a stable NO reservoir. In this Forum Article, we highlight these NO-dependent physiological pathways and examine complex chemical and biochemical reactions that govern NO and nitrite signaling in vivo. We focus on hemoprotein-dependent reaction pathways that generate and consume NO in the presence of nitrite and consider intermediate nitrogen oxides, including NO2, N2O3, and S-nitrosothiols, that may facilitate nitrite-based signaling in blood vessels and tissues. We also discuss emergent therapeutic strategies that leverage our understanding of these key reaction pathways to target NO signaling and treat a wide range of diseases.

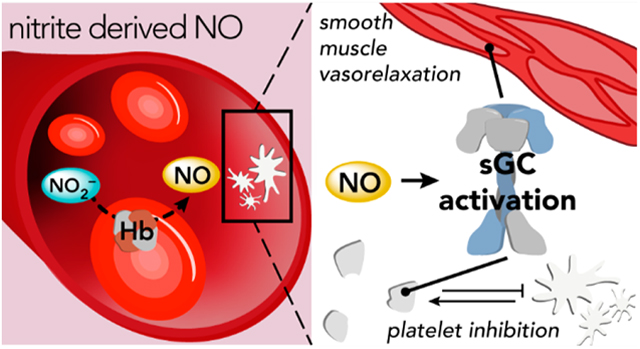

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The connection between nitric oxide (NO), a neutral diatomic molecule bearing a single unpaired electron, and human physiology was first realized in the context of vasoregulation when NO was identified as the endothelium-derived relaxing factor that activates the enzyme soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC). Robert Furchgott, Ferid Murad, and Louis Ignarro received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1998 for seminal contributions to this discovery of “nitric oxide as a signaling molecule in the cardiovascular system”. Central to this connection was the discovery that NO binding to heme directly enhances the activity of sGC, which catalyzes the formation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). As a second messenger, cGMP goes on to stimulate smooth muscle cells, primarily through the activation of protein kinase G (PKG). In the more than 30 years since this NO-dependent regulatory paradigm was established, rich collaborative efforts among investigators in inorganic chemistry, physiology, and biomedicine have elucidated much of the complex chemical reactivity and nuanced physiological regulatory functions of NO. Researchers have uncovered physiological sources of NO through enzymatic biosynthesis [by nitric oxide synthase (NOS)] as well as through redox bioactivation of the stable NO precursor nitrite (NO2−). Additional downstream effects of the NO–sGC–cGMP pathway have been determined, such as the regulation of platelet activation and inflammation. New physiological targets of NO and its derivatives have also been identified, including reactive thiols, tyrosine residues, and unsaturated fatty acids. These new discoveries have expanded the scope of NO-dependent regulation beyond cardiovascular homeostasis, and NO signaling is now implicated in many physiological and pathophysiological processes, such as neurotransmission, host defense, carcinogenesis, and response to oxidative stress. The primary objective of this Forum Article is to review critical oxidative and reductive reactions that govern NO and NO2− signaling, with a particular focus on reactions with hemoproteins. We will also highlight key NO-dependent signaling pathways and review emergent therapeutic strategies that target these pathways. Given our laboratory’s experience in nitrite bioactivation, we specifically emphasize the complex chemical and biochemical pathways that enable nitrite to modulate NO-dependent pathways and the therapeutic approaches that utilize this stable NO precursor.

SGC: THE CENTRAL NO RECEPTOR

NO regulates a number of critical biological processes via the NO–sGC–cGMP signaling pathway. In humans, picomolar-to-nanomolar concentrations of NO in vascular smooth muscle tissue enhance the guanylyl cyclase activity of sGC by several hundredfold, resulting in an increase of the second messenger molecule cGMP.1–3 This activation of sGC occurs within milliseconds of NO exposure in cells.4 cGMP subsequently interacts with downstream targets, including protein kinases and ion channels that regulate physiological processes such as vasodilation, platelet aggregation, and neurotransmission.5 Disruption of the NO–sGC–cGMP pathway is implicated in a large number of cardiovascular diseases, including pulmonary hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and atherosclerosis.6–8 Myriad studies have sought to elucidate the detailed molecular mechanisms of NO-dependent regulation, largely because of the connection between the NO–sGC–cGMP pathway and cardiovascular diseases, which are responsible for 1 in 3 deaths worldwide. In addition to NO itself, sGC has garnered significant therapeutic interest as pharmacological stimulators, and activators of sGC can enhance the enzymatic activity (and subsequent production of cGMP) independent of or in conjunction with NO.9

sGC Structure and Function.

sGC is a 150 kDa heterodimeric protein that contains two polypeptide chains (α, 690 a.a. residues; β, 620 a.a. residues) with modest sequence similarity and identical domain architectures. While multiple sGC polypeptide isoforms exist in humans (α1, α2, β1, and β2), the α1β1 heterodimer is ubiquitously expressed and most commonly studied.10,11 Both α and β subunits contain three domains: an N-terminal heme–nitric oxide binding (HNOB) domain (also referred to as a heme–nitric oxide–oxygen, or HNOX, domain), a HNOB-associated (HNOBA) domain comprised of a Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS)-like domain linked to a long α-helix that forms a parallel dimeric coiled-coil (CC) with the other monomer, and a C-terminal catalytic domain.12,13 A b-type heme binds to the β-subunit HNOB domain via a histidine side-chain ligand (His105), and NO binding to this five-coordinate heme site modulates guanylyl cyclase activity in the catalytic cyclase domain.14–16 Interactions between HNOBA domains facilitate α/β dimerization.17–19 The sGC catalytic domain is a member of the class III cyclase family and contains a single active site at the interface of the α/β heterodimer.17,20,21 In the active site, two Mg2+ cations and several hydrogen (H)-bond-donating amino acid residues stabilize GTP binding and facilitate intramolecular cyclization.22,23

NO-dependent activation of sGC occurs upon formation of a nitrosyl-heme species and ensuing scission of the axial His105 bond. Ignarro and colleagues first proposed this NO-dependent activation model based on several key observations: (1) heme is required to observe a NO-dependent increase in sGC enzymatic function, (2) direct addition of nitrosyl-heme complexes enhances the activity of apo-sGC, and (3) incubation of apo-sGC with iron-free protoporphyrin IX enhances enzymatic activity in a manner similar to that observed upon NO binding to heme-bound enzyme.1,24 A slew of spectroscopic investigations subsequently confirmed this activation model through direct observation of five-coordinate heme-nitrosyl species, which correlated with increased enzymatic activity.15,16,25–29

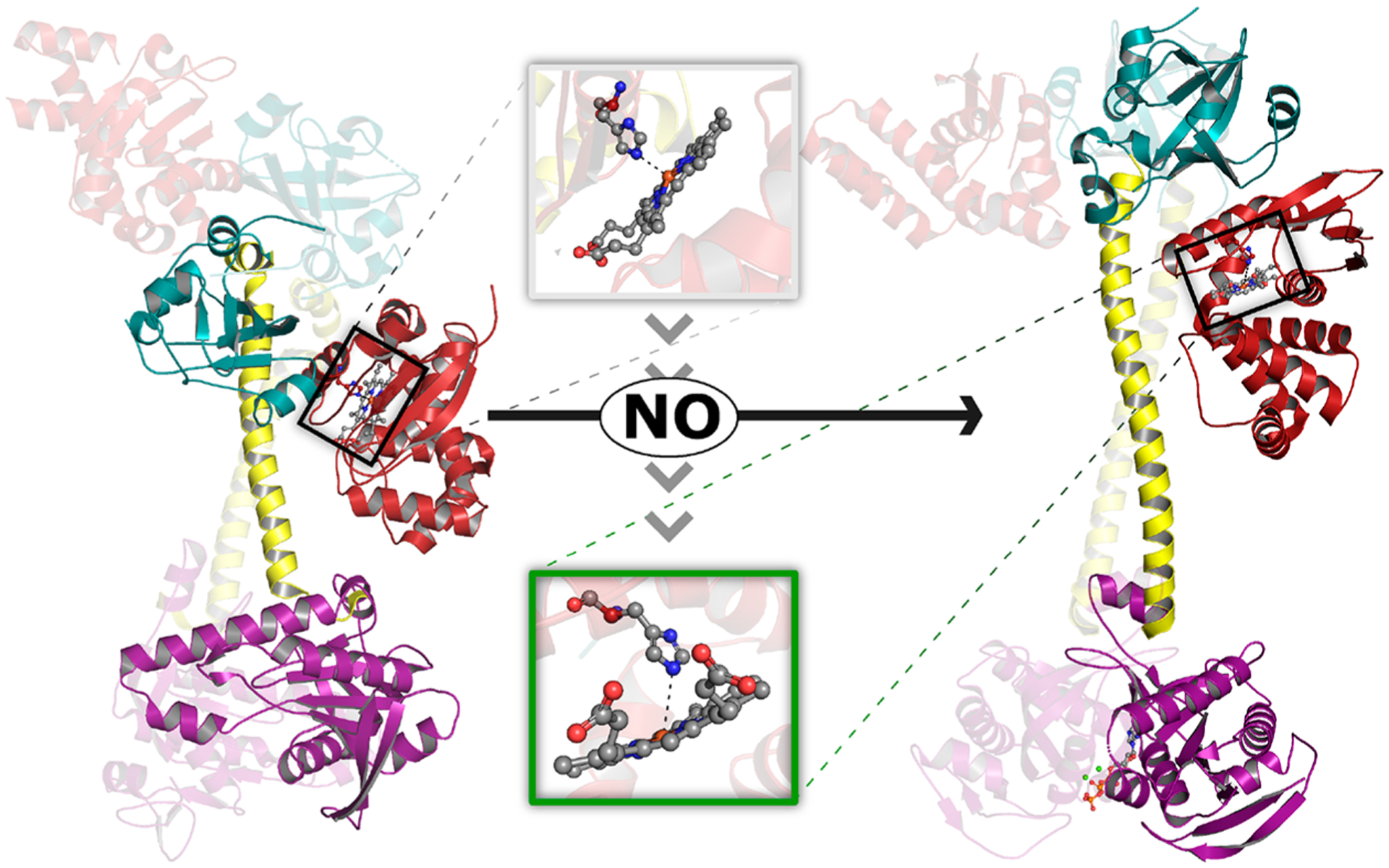

Long-range structural reorganization accounts for NO-induced allosteric signal transduction in sGC. After years of structural studies using sGC truncates, Kang et al. recently reported moderate-resolution (3.8–3.9 Å) cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures of full-length sGC in inactive (ferric and unliganded ferrous) and active (ferrous-NO-bound) forms (Figure 1).30 NO binding to the β-HNOB heme triggers a structural reorganization of the N-terminal sensor module (encompassing HNOB and HNOBA domains from α and β subunits). This conformational change is accompanied by extension of the α and β CC helices, as well as a 70° rotation of the relative orientation of the two helices. Rotation of the CC helices drives reorganization of the catalytic module: the active site volume increases to accommodate Mg2+ cations and the GTP substrate, thereby lowering KM and increasing guanylyl cyclase activity. A second cryo-EM study comparing active and inactive structures of sGC from the moth species Manuca sexta, published shortly after the Homo sapiens sGC study, largely corroborated the proposed structural model.31 These authors also observed reorientation of the sensor module, accompanied by elongation and rotation of the CC helices and ultimately opening of the GTP-binding active site in the catalytic module.

Figure 1.

NO-induced structural rearrangement in sGC. Structural models depicting inactive (left, PDB 6JT1) and active NO-bound (right, PDB 6JT2) sGC were determined using cryo-EM.30 While the entire heterodimer is depicted for each model, the heme-containing β subunit is highlighted for clarity. Binding of NO to ferrous heme in the β-HNOB domain (red) induces a coil-to-helix transition that extends and reorients the central helices of the CC (yellow). CC elongation is accompanied by rotation of the β-HNOB and core HNOBA (cyan) domains away from the catalytic cyclase domain (purple). Together, these structural changes cause rotation of the relative orientation of the two cyclase domains, increasing the volume of the active site and allowing two Mg2+ cations (green spheres) and one GTP molecule (orange ball and stick) to bind at the interface of the catalytic domains. Inset: NO-induced structural changes at the sGC heme. NO binding brings the Fe atom back into the heme plane and is accompanied by a ~0.7 Å increase in the distance between the heme Fe atom and Nε2 atom of His105. We note that the resolution of the structural data (3.9 and 3.8 Å for inactive and active structures, respectively) precludes in-depth analysis of the heme coordination environment (e.g., the authors do not include heme-bound NO in the active structural model).

Ligand Selectivity at the sGC Heme.

A critical detail of the NO–sGC–cGMP pathway is that NO binds sGC via the iron-containing cofactor heme. Metal cofactor binding and subsequent physiological signal transduction occur commonly for NO and other related “small molecule bioregulators”, such as dioxygen (O2), carbon monoxide (CO), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S). These Lewis base-type signaling molecules are historically described as “gasotransmitters”; however, relevant signaling interactions occur between molecules dissolved in solution, not in the gaseous phase, and we therefore refrain from using this term. Because of the ostensible similarity of these small-molecule bioregulators and their respective target metal centers, selectivity by small-molecule-sensing proteins is paramount.

Unlike most hemoproteins, sGC does not bind O2 with a high affinity but exhibits exquisite selectivity for NO. The factors that dictate small-molecule heme-binding affinities have recently been reviewed in terms of a “sliding scale rule” for hemoproteins.32–35 This sliding scale rule posits that five-coordinate iron(II) hemoproteins bearing an axial, neutral His ligand exhibit an intrinsic ligand selectivity for the diatomic small molecules NO, CO, and O2: KD(CO)/KD(NO) ≈ KD(O2)/KD (CO) ≈ 103–104. Four protein-derived structural factors in the heme pocket may alter the absolute and/or relative affinities of these ligands: (1) proximal Fe–N(His) bond strength (also described as “proximal ligand strain”), (2) distal pocket steric hindrance, (3) distal pocket electrostatics, and (4) the presence of a distal pocket H-bond donor. Differences in ligand access channels and heme distortions may also dictate hemoprotein selectivity, but detailed systematic investigations are required to fully understand these factors.34

In sGC, ligand selectivity against O2 is primarily dictated by two factors: a weak proximal Fe–N(His) bond and lack of a distal pocket H-bond donor. The Fe–N(His) bond in ferrous sGC is very weak, as evidenced by the remarkably low Fe–N stretching frequency (204 cm–1)29 compared to those of other His-ligated hemoproteins such as deoxyhemoglobin (215 cm−1)36 and deoxymyoglobin (218 cm−1).37 Changes in the proximal ligand bond strength modulate the ligand affinities for NO, CO, and O2 in a similar manner: the weaker the Fe–N(His) bond, the lower the ligand binding affinity across the board. Distal heme pocket H-bond donation selectively stabilizes O2 binding in five-coordinate hemoproteins, as observed for hemoglobin and myoglobin.38 This structural factor likely contributes to poor O2 binding in sGC, which lacks a H-bond donor in the distal pocket. Supporting this hypothesis, a bacterial H-NOX protein (with sequence and structural homology to sGC) bears a H-bonding Tyr residue in the distal heme pocket and forms a stable oxyferrous species.39,40 While substitution of the analogous distal pocket residue in human sGC (Ile145) with Tyr does not give rise to a stable oxyferrous species,41 steric clashes likely impart geometric constraints that preclude proper H-bond donation in this mutagenic model. Taken together, these factors lead to an estimated binding dissociation constant for O2 of around 1.4 M, far exceeding the solubility of O2 in aqueous solution (~260 μM).32,34

At equimolar concentrations, NO reversibly binds to the five-coordinate sGC heme to form a relatively stable six-coordinate species with a NO dissociation constant of 54 nM (KD = koff,6-c/kon,5-c = 27 s−1/1.4 × 108 M−1 s−1 at 24 °C).3,33 This NO affinity is consistent with the sliding scale rule: the dissociation constant for CO binding to sGC is 97 μM,42 roughly 3 orders of magnitude lower than that of NO.34 Taken in the context of physiological signaling in the vascular wall, which occurs at low nanomolar concentrations of NO,43 it is likely that the above KD value is an overestimation and/or that only a small fraction of sGC is required to trigger the activation of downstream PKG. Unfortunately, it has been difficult to rectify the kinetic properties ascribed to sGC through in vitro experimentation, with the complex NO signaling dynamics observed in vivo. Understanding the exact nature of NO binding and subsequent sGC signaling presents an extreme challenge for the field, and creative cross-disciplinary approaches are needed to fully understand these complexities.

Adding to the complexity of sGC-dependent signaling is the controversial notion that CO activates sGC under physiological conditions. Several studies have invoked CO-induced activation of sGC under physiological conditions in the context of neurotransmission,44 regulation of vascular tone,45 and inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation.46,47 However, as noted above, the CO binding affinity of the sGC heme is ~100 μM, while the basal physiological levels of CO vary between 2 and 5 nM.42,48,49 Even though it is possible that localized CO concentrations may rise above basal levels under pathophysiological conditions (e.g., inhaled CO poisoning), CO-bound sGC remains six-coordinate and exhibits 80-fold lower enzymatic activity compared to that of five-coordinate, NO-bound sGC.26 Likely the only relevant context of CO-induced activation of sGC is in the presence of pharmacological sGC stimulators, which enhance sensitivity to small-molecule bioregulators (vide infra).

While CO is unlikely to activate sGC, mounting evidence suggests that CO itself still possesses properties of a signaling molecule under physiological conditions, indicating other (metalloprotein) targets. CO, which is generated as a byproduct of heme degradation by O2- and NADPH-dependent heme-oxygenase (HO) enzymes, has been implicated in maintaining homeostatic function through transcriptional regulation of circadian rhythm and regulation of large-conductance Ca2+ channels.50–52 The precise molecular targets of CO that confer these effects remain elusive, although spectroscopic investigations have led to the identification of several hemoprotein targets of CO, including NPAS2/CLOCK and Rev-Erbβ as well as Ca2+- and voltage-gated K+ channels.53–59 These hemoproteins exhibit high (nM) CO binding affinities; however, the relative affinities of NO and O2 have not been determined. Additionally, a large conceptual gap still exists between in vitro CO-binding properties of these putative mammalian CO sensors and in vivo conditions that could result in CO-dependent signaling. One step toward closing this gap is to better understand the spatiotemporal distribution of CO and NO in cellular and animal models. Understanding the interplay between and NO and CO signaling is a crucial area of future study because NO and CO likely compete for heme sites under certain physiological and pathophysiological conditions.

sGC as a Therapeutic Target: Pharmacological Stimulators and Activators.

Given the central role of sGC in the NO–sGC–cGMP signaling axis and the relevance of this pathway to cardiovascular disease, many therapeutic strategies that directly target sGC have been developed. Strategies aimed at targeting sGC via NO biosynthesis will be discussed in detail below. In this section, we briefly highlight pharmacological approaches to modulate sGC activity in the context of stimulators and activators. For a comprehensive overview of sGC therapeutic strategies, we direct the reader to recent reviews.9,60

sGC stimulators have emerged as a promising class of therapeutics currently undergoing preclinical and clinical studies to treat pathophysiological conditions including cardiovascular, fibrotic, hematologic, and metabolic diseases. sGC stimulators are organic small molecules that interact directly with the sGC β1 HNOB subunit bearing a ferrous heme that is primed for NO sensing. Pharmacologic enhancement of the sGC enzymatic activity was initially characterized as direct stimulation in an NO-independent manner,61–64 but subsequent studies have demonstrated that sGC stimulators also sensitize the enzyme to NO (and CO), allowing for NO-dependent activation at lower concentrations of NO.65 The detailed molecular interactions that confer stimulatory activity on this class of drugs are not completely understood but likely involve contacts between a stimulator molecule and the heme-containing β1 HNOB domain. Presumably, these interactions stabilize active sGC protein conformation30,31 and/or enhance NO geminate recombination by blocking a heme pocket exit channel.66,67 Preclinical animal models have suggested roles for sGC stimulators in the treatment of a wide variety of diseases, including pulmonary hypertension,68,69 heart failure,70 chronic kidney disease,71,72 fibrosis,73–75 metabolic disease,76 and sickle cell disease.77 Building on these preclinical findings, researchers have conducted (or are currently conducting) clinical trials to extend therapeutic applications of sGC stimulators to human patients. One stimulator compound, riociguat (BAY 63–2521), has been approved to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.78,79 An ongoing phase 2 clinical trial in our laboratory is assessing the use of riociguat to mediate severe adverse cardiovascular events associated with sickle cell disease (NCT02633397). Two recently completed phase 3 trials assessed the efficacy of vericiguat (BAY 1021189), another sGC stimulator,80 as a treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). These studies found that vericiguat treatment improved outcomes (death and incidence of hospitalization) for patients with HFrEF, but outcomes (physical limitation score and 6 min walking distance) for patients with HFpEF did not improve upon treatment.81,82

sGC activators comprise a second class of drugs that enhance the enzymatic activity of sGC with inactive (ferric) heme or no heme present.83 These activators serve as heme analogues that allosterically enhance sGC activity by mimicking the structure of a ferrous nitrosyl-heme adduct, either through direct binding to apo-sGC or replacement of ferric heme.84,85 Oxidation and loss of heme contribute to sGC inactivation and signal degradation. Such sGC loss is exacerbated under conditions of oxidative stress, and sGC activators may serve as a complementary pharmacologic intervention under pathophysiological conditions to enhance sGC activity and prevent enzymatic degradation.86–89 In a preclinical study, mice that express heme-free sGC develop hypertension and exhibit blunted NO-dependent vasodilation; however, treatment with the sGC activator cinaciguat (BAY 58–2667) significantly decreased blood pressure, consistent with heme-independent activation.90 While preclinical studies demonstrating the pharmacological benefits of sGC activators were promising, several clinical trials aimed at treating acute heart failure and peripheral arterial occlusive disease using cinaciguat were stopped after patients exhibited hypotension without clear benefits.70 One open phase 1 clinical trial (NCT04609943) seeks to assess dose limitations of activator compound BAY 1211163 in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Further research is required to better understand the limitations and ideal clinical applications of sGC activators.

l-ARGININE OXIDATION: NO BIOSYNTHESIS BY NOS

The canonical NO biosynthetic pathway features NOS enzymes that catalyze the oxidation of l-arginine to l-citrulline and NO. NOS enzymes are widely distributed among different tissues and are critical in the maintenance of vascular homeostasis as well as regulation of inflammation, immune response, and neurotransmission.91 NOS-dependent generation of NO directly modulates the NO–sGC–cGMP signaling axis and therefore represents a valuable therapeutic target in NO signaling.

The NOS active site consists of a five-coordinate, thiolate-ligated heme center where two sequential O2- and NADPH-dependent oxidation reactions occur via generation of a highly oxidizing iron–oxo species. First, one of the arginine guanidino N atoms is hydroxylated to form Nω-hydroxy-l-arginine (NOHA), which is subsequently oxidized in a second reaction to form l-citrulline and a ferric nitrosyl species.92 In order to become bioavailable, NO must dissociate from the ferric heme site. Untimely reduction of the ferric nitrosyl-heme to a nonlabile ferrous nitrosyl species initiates a “futile cycle” in which the enzyme returns to the ferric resting state upon reaction with O2 and generation of nitrate. Thus, for optimal NO synthesis, reduction of ferric nitrosyl-heme occurs at a slow rate relative to NO dissociation from the ferric heme; however, reduction of the ferric–superoxo heme species and subsequent disproportionation occurs at a fast rate relative to superoxide dissociation.

To accommodate these kinetic constraints, the NOS enzymatic complex employs several cofactors and intricate quaternary structural interactions. The active site in the N-terminal oxygenase domain binds heme and the electron-transport mediator tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). NADPH, which binds to a C-terminal reductase domain, reduces flavin adenine dinucleotide and flavin mononucleotide cofactors in the reductase domain before ultimately reducing the heme or BH4 cofactors in the oxidase domain. An intervening calmodulin binding domain regulates electron shuttling from the reductase domain to the oxygenase domain: calmodulin binding to a NOS homodimer enables domain swapping in which electrons from one reductase domain monomer reduce the opposite oxygenase domain, triggering NO production in the presence of O2 and l-arginine substrates.93–96

Three NOS isoforms exist in humans: neuronal NOS (nNOS, NOS I), inducible NOS (iNOS, NOS II), and endothelial NOS (eNOS, NOS III). These three isoforms are structurally homologous and share 50–60% overall sequence homology,97,98 although significant differences exist between nNOS, iNOS, and eNOS. These NOS isozymes exhibit differential expression patterns at the tissue and subcellular levels.60 Both nNOS and eNOS are constitutively expressed, and protein activity is primarily dictated by calmodulin/Ca2+ binding and post-translational modifications.99–101 For example, half-maximal activity for nNOS and eNOS occurs at Ca2+ concentrations of 150 and 300 nM, respectively, while iNOS activity exhibits no Ca2+ dependence.98,102 Unlike nNOS and eNOS, iNOS is primarily regulated at the transcriptional level.102 Differences in kinetic parameters, including the heme reduction rate, O2 binding rate, kcat, and NO release rate, enable NOS isoforms to produce NO at different fluxes under different cellular conditions.92,103 We direct the reader to several excellent reviews for more details regarding physiological regulation of isoform-specific NOS activity.60,91,98,100,104,105

Uncoupling of NOS enzymes, particularly eNOS, lowers NO production and often generates highly oxidizing superoxide and peroxynitrite species. Formally, NOS uncoupling occurs when NADPH consumption does not match stoichiometric NO production.60,106–108 Such uncoupling may be caused by a deficiency of the l-arginine substrate, either through trafficking/compartmentalization or metabolism by arginases.109–113 Alternatively, NOS uncoupling may arise when electron shuttling between reductase and oxygenase domains is disrupted. Changes in the quaternary structure, including calmodulin and/or dimer dissociation, give rise to NOS uncoupling, often with concomitant generation of superoxide.114–119 Equivalents of superoxide may rapidly react with nearby NO, resulting in the formation of peroxynitrite, a highly reactive oxidant.120 In the presence of strong oxidants, such as superoxide- or peroxynitrite-derived species, BH4 can be oxidized to dihydrobiopterin (BH2), which competitively binds to eNOS and is unable to facilitate heme reduction and subsequent l-arginine hydroxylation.121–123 Post-translational modifications, including glutathionylation of eNOS cysteine residues and phosphorylation of a critical threonine residue, have been shown to disrupt electron flow and uncouple NOS activity as well.101,124–126 Importantly, eNOS is responsible for the production of basal NO levels that maintain optimum cardiovascular function,127 and eNOS uncoupling is implicated in myriad cardiovascular diseases.128–133 Therapeutic strategies to combat eNOS uncoupling focus on increasing bioavailable l-arginine or BH4 by direct supplementation, stimulation of production pathways, or inhibition of metabolic/decomposition pathways.134–138

NITRITE REDUCTION: THE NITRATE–NITRITE–NO PATHWAY

While NOS enzymes represent the canonical physiological source of NO, additional routes for NO generation have been established in recent years via the nitrate–nitrite–NO pathway. This pathway is critical for NO regulation and metabolism; nitrite and nitrate serve as long-lasting NO storage pools and have become valuable therapeutic targets in the past 20 years. Importantly, many of the chemical and biochemical reactions that convert nitrate and nitrite to NO occur under O2-limited conditions, allowing the nitrate–nitrite–NO pathway to complement O2-dependent NO production in NOS enzymes.

Inorganic nitrate (NO3−) and nitrite (NO2−) act as stable NO precursors under physiological conditions. Facultative anaerobes inhabiting the human salivary glands reduce dietary nitrate—abundant in leafy green vegetables, beets, and cured meats—to nitrite using reductase enzymes analogous to those found in soil-denitrifying bacteria.139–141 Once swallowed, ingested nitrite and nitrate that exceed capacity for oral bacterial reduction can be absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract. Interestingly, as much as 25% of nitrate circulating in the plasma is reconcentrated in saliva via the sialin transporter, driving an enterosalivary recirculation of nitrate and additional nitrate reduction.142,143 Nitrite and nitrate are also generated endogenously through oxidation of NO primarily derived from eNOS.144 In plasma, oxidation of NO to form nitrite is catalyzed by the multicopper oxidase enzyme ceruloplasmin (eq 1).145

| (1) |

Reoxidation of copper occurs in an O2-dependent fashion. Under basal conditions, dietary nitrate reduction accounts for approximately half of the nitrite found in the plasma, while NO oxidation by ceruloplasmin accounts for the other half.146–148 While exogenous sources likely contribute to the majority of nitrate found in the body,149 endogenous oxidation of NO to form nitrate, a process known as NO dioxygenation, is facilitated by oxyferrous heme sites (eq 2).150,151

| (2) |

NO dioxygenation, a reaction common to all oxyferrous hemoproteins, has been specifically characterized in globin proteins found in the vasculature in vivo, including α-hemoglobin and cytoglobin,152–155 and likely contributes to regulation of the NO levels in the vascular endothelium.

Noncatalytic nitrite reduction to NO can occur in vivo as the physiological pH decreases. Nitrite is a weak base with a pKa value of 3.11 at 37 °C,156 and the standard reduction potential for nitrite changes significantly from highly favorable under acidic conditions to unfavorable under basic conditions (eqs 3 and 4).157,158

Reductive half-cell reaction for nitrite under acidic conditions:

| (3) |

Reductive half-cell reaction for nitrite under basic conditions:

| (4) |

Further, a well-accepted mechanism of nitrite reduction in acidic, aqueous solution involves dehydration of nitrous acid to generate dinitrogen trioxide (N2O3; eq 5), followed by disproportionation of N2O3 to generate 1 equiv of NO and 1 equiv of nitrogen dioxide (NO2; eq 6).

| (5) |

| (6) |

This acid-promoted nitrite reduction is viable under conditions of low pH and high nitrite concentrations.159,160 During ischemia, reduced blood flow results in tissue acidosis that may support acid-promoted nitrite reduction.161 Additionally, the above conditions are met in the stomach after a nitrate-rich meal, where NO has been shown to regulate gastric blood flow, mucous production, and host defense.162–164 In addition to liberating NO, N2O3 is a powerful nitrosating agent that can react with primary and secondary amines to form N-nitrosoamines (vide infra). Subsequent metabolism of large quantities of N-nitrosoamines can lead to the formation of carcinogenic methylating agents,165 and some associative studies suggest that this adverse reactivity may contribute to an increased risk of malignancy for those who consume large quantities of processed meats that utilize nitrite in the curing process.166 On the other hand, ingestion of nitrate-rich leafy green vegetables leads to very high nitrite levels via nitrate bioconversion by oral bacteria, yet diets high in leafy green vegetables have not been consistently associated with significant risk of malignancy in large epidemiological studies.143,149,167

BIOACTIVATION OF NITRITE IN RED BLOOD CELLS (RBCS)

Because acid-promoted nitrite reduction occurs under limited conditions in vivo, nitrite would appear to serve little role in generating bioavailable NO. Very early work exploring the vasodilatory effects of nitrite in vitro seemed to support this theory: supraphysiological concentrations of nitrite were required to induce vasodilation in aortic rings, and these vasodilatory effects could be enhanced at lower pH values.168–171 However, a series of investigations characterizing nitrite levels (which vary from 150 to 1000 nM in plasma and up to 10 μM in tissue)172,173 and nitrite-dependent vasodilation in humans definitively identified a role for nitrite in the regulation of vascular tone through bioactivation. These studies demonstrated that plasma nitrite levels (1) exhibit an arterial–venous gradient, suggesting that nitrite is consumed across the physiological O2 gradient, (2) correlate well with eNOS activity, (3) increase with NO inhalation, and (4) decrease under conditions of hypoxia or exercise-induced stress.147,172,174,175 Additionally, infusion of nitrite (at near-physiological nanomolar concentrations) in the brachial forearm artery decreased systemic blood pressure and increased blood flow.176,177 Subsequent investigations in animals and humans corroborated these findings: infusion of nitrite decreased blood pressure in a dose-dependent manner, and blood pressure returned to basal levels several hours after infusion.178–181 Furthermore, venous nitrosyl-heme levels increased significantly during nitrite infusion, consistent with nitrite bioactivation to generate NO and subsequent up-regulation of vasodilation via the NO–sGC–cGMP pathway.176

Originally, researchers suggested that molybdenum-containing oxidoreductase enzymes, which exhibit nitrite reductase activity under anaerobic conditions,182,183 could facilitate nitrite bioactivation. In preclinical rodent models and in vitro studies at low O2 tensions and very acidic pH values, specific inhibitors of the molybdopterin protein xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) attenuated nitrite reductase activity and subsequent nitrite-dependent vasodilation;179,184 however, specific inhibition of XOR activity did not inhibit nitrite-dependent vasodilatory response in humans given an infusion of nitrite.176,178 While it is likely that molybdopterin enzymes contribute to nitrite bioactivation in tissue under specific physiological O2 and pH conditions, another highly abundant metalloprotein, hemoglobin (Hb), primarily facilitates nitrite bioactivation in circulation.

Consistent with in vivo data indicative of nitrite-dependent vasodilation, in vitro experiments indicate that hemoglobin facilitates nitrite reduction in RBCs. For example, aortic rings exhibit vasodilatory activity in the presence of deoxyhemoglobin (deoxyHb) and nitrite but not in the presence of nitrite alone.176,185 This Hb-facilitated bioactivation of nitrite modulates signaling along the NO–sGC–cGMP pathway because incubation of RBCs with nitrite induces cGMP production and subsequently inhibits platelet activation (vide infra).186–189 Further, NO gas was indirectly observed by a chemiluminescent reporter in reactions of deoxygenated RBCs and rat aortas with nitrite.171,185,188,190

These seminal discoveries prompted exploration of the molecular mechanisms that drive nitrite-mediated signaling, and in this section, we review the proposed chemical and biochemical reaction pathways that occur between hemoglobin, NO, nitrite, and other nitrogen oxides in RBCs. While multifaceted and complex in nature, together these reactions may explain the observed pharmacological and in vivo effects of nitrite acting as a regulator of vascular tone under a variety of physiological and pathophysiological conditions. The elucidation of these pathways has been crucial for the development of nitrite therapeutics targeting cardiovascular diseases.

Hb-Facilitated Nitrite Reduction.

When O2 tensions are low at physiologically relevant pH values, ferrous hemoproteins, specifically globins, facilitate nitrite reduction to generate NO (Figure 2, solid red pathway). Reduction of nitrite occurs via an inner-sphere electron-transfer mechanism in which an equivalent of nitrite binds to deoxyHb, is protonated, and then is reduced, resulting in 1 equiv of NO, ferric hemoglobin (metHb), and water (eq 7).191–194

| (7) |

Importantly, NO binds to ferric heme with an affinity several orders of magnitude lower than that of ferrous heme195 and therefore undergoes facile diffusion away from the site of nitrite reduction to participate in downstream signaling pathways.

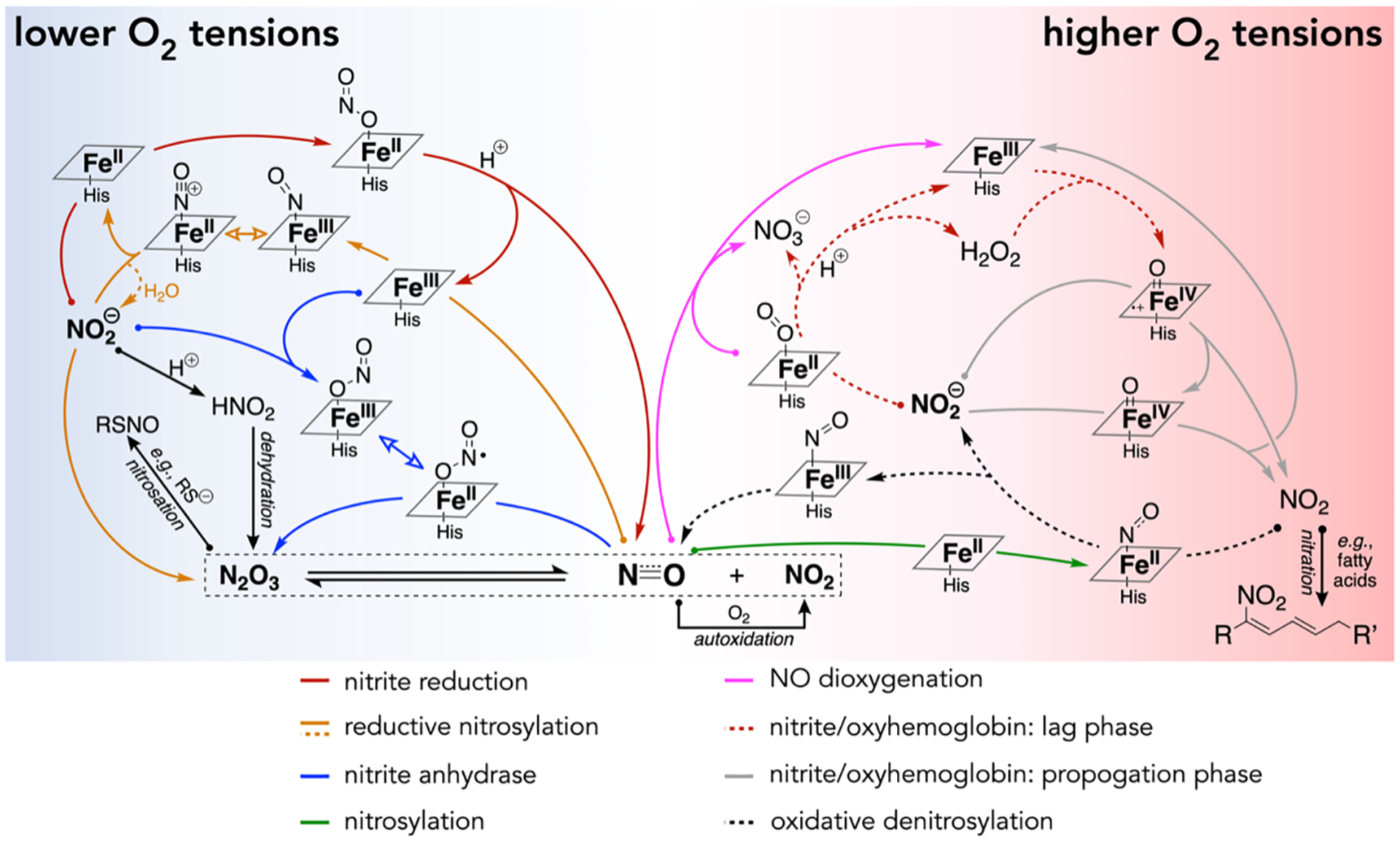

Figure 2.

Compendium of proposed chemical and biochemical pathways that facilitate signaling by NO and NO-related species. Reactions with curved arrows depict processes that are facilitated by hemoproteins. Exact stoichiometries are not shown for clarity but can be found in the text where appropriate.

Evidence from in vitro chemical and biochemical experiments, as well as in vivo preclinical and clinical studies, has coalesced to support a paradigm in which RBC-derived hemoglobin mediates nitrite reduction to produce bioavailable NO; however, three critical biochemical reactions deplete NO and thereby complicate this model. First, as aforementioned, ceruloplasmin (present at concentrations of 1–5 μM in plasma)196,197 readily oxidizes NO and generates about half of the nitrite found in blood plasma (eq 1).145,146 Second, at lower O2 tensions, NO generated by Hb-mediated nitrite reduction in RBCs can rapidly bind to nearby deoxyHb sites (eq 8).

| (8) |

This nitrosylation or “autocapture” reaction occurs with a rate constant of 9 × 107 M−1 s−1 for deoxyHb198 and effectively sequesters NO as a highly stable ferrous nitrosyl-heme species. Third, at higher O2 tensions, NO reacts with oxyHb to generate nitrate through NO dioxygenation (eq 2; Figure 2, pink pathway), which occurs with a near-diffusion-limited rate constant of (6–8) × 107 M−1 s−1 for oxyHb at 20 °C.150,199,200 Taking into account these mechanisms of NO depletion, one model suggests that NO exhibits a half-life of 1 μs in RBCs.201 Thus, a key mechanistic question surrounds nitrite-mediated signaling: how do RBCs facilitate nitrite bioactivation in a manner that produces bioavailable NO? Some evidence suggests that nitrite reduction occurs preferentially at the RBC cell membrane surface,202 which would allow for more facile NO escape, especially considering that NO readily partitions to nonpolar media over aqueous media.160 However, compartmentalization alone likely does not fully rectify the rapid rate of NO depletion in RBCs, and additional chemical and other Hb-mediated reactions are worth considering.

Role of N2O3 in Nitrite-Mediated Signaling.

Nitrite-mediated signaling in RBCs may be facilitated by N2O3,203 which is generated in a very fast radical reaction between NO and NO2 (reverse reaction of eq 6). The requisite equivalent of NO2 may form as a product of NO autoxidation (eq 9).

| (9) |

While this third-order reaction does not typically proceed under physiological conditions in the aqueous cellular environment, more favorable reaction conditions may occur in the nonpolar environment of the RBC cell membrane, where it is estimated that autoxidation may occur up to 30 times faster than that in an aqueous environment due to enhanced solubility of NO and O2.204 Additional nitrite- and Hb-dependent pathways that generate NO2 exist under physiological conditions (vide infra).

Another pathway to form N2O3 occurs via certain Hb-mediated reactions. Because deoxyHb facilitates nitrite reduction, a transient ferric-nitrosyl intermediate forms (Figure 2, orange pathway). This electrophilic intermediate may subsequently react with 1 equiv of nitrite, liberating N2O3 and ferrous hemoglobin (eq 10).159,205,206

| (10) |

Such reductive nitrosylation may also occur when water attacks the ferric-nitrosyl species, liberating 1 equiv of nitrite and ferrous heme (eq 11).

| (11) |

Nitrite accelerates the rate of reductive nitrosylation, presumably because of the enhanced nucleophilicity of nitrite compared to water or hydroxide.206 Alternatively, nitrite may first bind to a ferric heme site and then react with 1 equiv of NO to liberate N2O3 and ferrous heme (eq 12).203

| (12) |

Computational and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopic evidence suggests that the ferric-nitrite species exhibits significant electron delocalization, giving the heme species partial ferrous-NO2 radical character.203,207–209 This radical character would suggest rapid reaction with NO to yield N2O3 in a “nitrite anhydrase” mechanism (Figure 2, blue pathway). Given the highly dynamic nature of nitrogen oxide reactions in RBCs, it is entirely possible that both of the above mechanisms (eqs 10 and 12) operate, although these details have yet to be resolved.

Formation of N2O3 in RBCs may facilitate export of NO via several pathways. As a small, uncharged molecule, N2O3 can readily diffuse across the cell membrane, and the molecule undergoes facile homolytic cleavage to generate NO and NO2.187 As described above, N2O3 is a powerful nitrosating agent (i.e., NO+ donor) because of partial NO+NO2− character.210 Under physiological conditions, N2O3 may transfer NO+ to nucleophilic thiols and amines (eqs 13 and 14).

| (13) |

| (14) |

Reversible S-nitrosation of β-hemoglobin Cys93 (SNO-Hb) has been proposed as an additional mechanism to extend the lifetime of Hb-derived NO;211 however, the details of this proposed mechanism are heavily debated. A recombinantly expressed Cys substitution hemoglobin variant, β-Cys93Ala, did not inhibit nitrite-dependent vasodilation in vitro, and an in vivo study showed that genetically engineered mice with the same β-Cys93Ala substitution do not exhibit impaired hypoxic vasodilation.185,212 While these results demonstrate that SNO-Hb is not a critical intermediate in nitrite-mediated signaling, modifications to β-Hb Cys93, including mutagenic Cys substitution and alkylation using NEM, potentiate nitrite reductase activity by decreasing the heme redox potential and allosterically stabilizing the R-state hemoglobin (vide infra).213–215 Thus, post-translational SNO-Hb may also enhance nitrite reductase activity and thereby potentiate the rate of nitrite reduction. More generally, post-translational modifications of Cys residues via S-nitrosation may alter protein function in many important physiological and pathophysiological contexts, such as reversible inhibition of proteins in the mitochondrial electron-transfer chain.216–219

Allosteric Regulation of Hb-Facilitated Nitrite Reduction.

Fully unliganded hemoglobin exists in the T-state, which exhibits low ligand binding affinity. The binding of ligands, including O2, CO, and NO, to heme sites within hemoglobin favors an allosteric transition to the high-affinity R-state.220 These allosteric changes also influence nitrite reduction as the rate constant for deoxyHb increases from 0.1 M−1 s−1 in the T-state to 6 M−1 s−1 in the R-state at 25 °C.194,221–223 Two factors likely contribute to this allosterically induced change in the nitrite reductase activity. First, nitrite reduction (and subsequent heme oxidation) is thermodynamically favored for R-state hemoglobin, which has a lower redox potential than T-state hemoglobin (E1/2 vs NHE: HbAR = 42 mV; HbAT = 154 mV).185,194,215 Second, nitrite reduction is kinetically favored for R-state hemoglobin, which possesses a more open heme pocket that allows for facile nitrite binding.

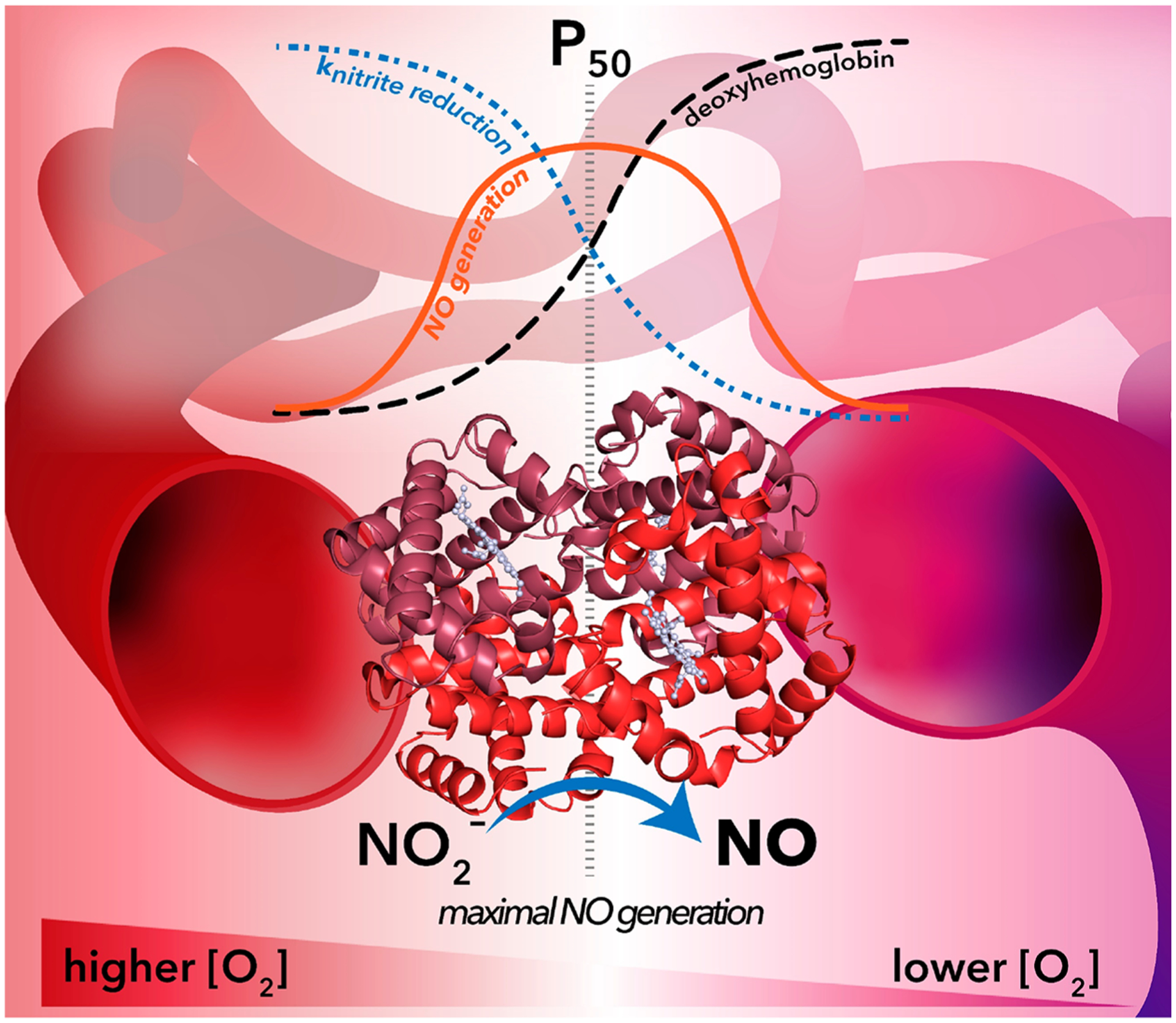

As Hb-mediated nitrite reduction proceeds, NO may bind to a neighboring ferrous heme. NO binding allosterically stabilizes R-state hemoglobin and thereby increases the nitrite reduction rate constant of other heme sites within the tetramer. Simultaneously, NO binding limits the number of available ferrous heme sites for subsequent nitrite reduction. Under anaerobic conditions, this effect is known as “allosteric autocatalysis” and results in a sigmoidal reaction trace for nitrite reduction.194,221 Similarly, O2 binds to deoxyHb under more aerobic conditions, stabilizing the R-state and enhancing nitrite reduction while simultaneously limiting the number of sites where nitrite can react.221 These opposing ligand-dependent effects give rise to a bell-shaped curve upon estimation of the nitrite reductase activity as a function of O2 tensions, with maximal activity occurring between 40 and 60% oxyHb saturation (Figure 3).224,225 Importantly, this range of maximal activity directly coincides with the set point for hypoxic vasodilation in humans, a physiological process in which blood vessels dilate in order to enhance blood flow and match O2 delivery as hemoglobin desaturates.226 The coincidence of oxyHb saturation levels for maximal Hb-mediated nitrite reductase activity and the onset of hypoxic vasodilation further supports the hypothesis that bioactivation of nitrite in RBCs contributes to the regulation of vascular tone under physiological conditions in the capillary bed.

Figure 3.

Maximal nitrite-dependent NO generation coincides with the hemoglobin P50 value for O2 in the vasculature. In RBCs, hemoglobin approaches a maximal nitrite reductase rate constant of 6 M−1 s−1 (blue dotted line) at O2 tensions above P50 when the majority of hemoglobin is stabilized in the R-state.194,223 As O2 tensions fall below P50 (moving from left to right across the figure), O2 dissociates from heme concomitant with an allosteric R-to-T-state transition. At low O2 tensions, the hemoglobin nitrite reduction rate constant approaches a minimum value of 0.1 M−1 s−1.194,222 The number of deoxyHb sites available for nitrite reduction (black dashed line) mirrors O2-dependent changes in the nitrite reduction rate constant values: more deoxyHb sites become available as O2 tensions drop and O2 dissociates from heme sites. These opposing factors (nitrite reduction rate constant and deoxyHb site availability) give rise to a bell-shaped curve for the observed rate of nitrite-dependent NO generation (orange line) as a function of O2 tensions in the vasculature. Importantly, maximal nitrite reductase activity occurs at values between 40% and 60% of the hemoglobin P50 value, a range that coincides with the set point of hypoxic vasodilation in humans.226

Pathways That Propagate Nitrite-Mediated Signaling under Oxygen-Replete Conditions.

In addition to nitrite reduction with deoxyHb, nitrite undergoes a complex series of reactions with oxyHb to generate nitrate and metHb at O2 tensions near the P50 value for hemoglobin (27 mmHg).227 An initial lag phase is observed when an excess of nitrite is present relative to oxyHb,228,229 which yields hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and nitrate (eq 15; Figure 2, dashed red pathway).

| (15) |

Several key studies suggest that this initial lag phase involves H2O2 but not superoxide (O2•−): catalase, but not superoxide dismutase, inhibits the reaction when added during the initial reaction phase, and kinetic models that incorporate H2O2 generation are consistent with experimentally observed reaction traces.229–231 Reaction of peroxide with metHb results in formation of a ferryl radical cationic [FeIV=O)]•+ species reminiscent of that observed in compound I of cytochrome P450.229,232 Subsequent reactions of 2 equiv of nitrite, first with the [FeIV=O)]•+ ferryl radical cation and second with the reduced diamagnetic [FeIV=O] ferryl intermediate species, result in 2 equiv of NO2 and metHb in an autocatalytic propagation reaction (eq 16; Figure 2, solid gray pathway).

| (16) |

Importantly, when the cellular partial pressure of O2 nears the P50 value of hemoglobin, hemoglobin will exhibit partial O2 saturation. At such physiologically relevant O2 tensions, nitrite reduction by deoxyHb occurs alongside the nitrite–oxyHb reaction.232 Cross-reactivity between the products of these two Hb-mediated reactions provides (1) a means to quench propagation of the nitrite–oxyHb mechanism and (2) another pathway for NO escape from RBCs. NO2, responsible for autocatalysis, oxidizes “inert” ferrous nitrosyl-heme, generated during nitrite reduction, to ferric nitrosyl-heme (eq 17; Figure 2, dashed black pathway).233,234

| (17) |

As described above, ferric heme centers generally exhibit NO dissociation rate constants several orders of magnitude higher than those of ferrous heme centers,195 and therefore this “oxidative denitrosylation” process leads to facile release of Hb-bound NO.232

In summary, numerous physiological data in vitro and in vivo (through human and animal studies) provide evidence that RBC-encapsulated hemoglobin facilitates nitrite-dependent vasodilation and platelet activation via the NO–sGC–cGMP pathway;176–179,181,186,187,189,235 however, the precise mechanisms that enable this bioactivation are not fully understood. A lingering central question is whether inefficient NO diffusion at the RBC membrane accounts for signaling or if intermediate chemical species are required. The above chemical reactions involving hemoglobin, oxygen, nitrite, NO, NO2, N2O3, and S-nitrosothiols, serve as examples of putative pathways that may allow nitrite-derived nitrogen oxides to escape RBCs and participate in the observed downstream signaling. Our investigations all support convergent bioactivation around the P50 value of hemoglobin, where (1) NO signaling has been detected experimentally by NO formation, platelet inhibition, vasodilation, and inhibition of mitochondrial respiration and (2) reactions that generate NO, NO2, and N2O3 are likely operative. It is important to note that the prevalence of these different reaction pathways varies under different conditions (i.e., O2 tension, nitrite concentration and relevant rate constants, pH, membrane localization). Further, there may be undiscovered routes that mediate nitrite-based signaling in RBCs. Fully elucidating the mechanistic details of nitrite signaling in the vasculature and in tissue will provide valuable context for interpretation of the results from clinical trials that employ nitrite therapeutics, described below.

Nitrite Therapeutics.

A growing body of preclinical and clinical studies support the use of nitrate and nitrite therapeutic agents for the controlled delivery of NO. In contrast to NO, which is quickly consumed in the blood (t1/2 < 2 ms),236,237 nitrite persists in circulation long enough to reach peripheral blood vessels and tissues (t1/2 = 30–48 min).178,180,238,239 In fact, the peripheral vasodilatory effects of therapeutically inhaled NO have been ascribed to more stable NO-derived species, such as S- and N-nitrosated proteins (including SNO-albumin and SNO-Hb),211,240 nitrated lipids,241,242 and nitrite,176 which may form in the pulmonary vasculature during NO inhalation.222 Hb-facilitated nitrite reduction occurs at low O2 tensions, and this process offers a complementary pathway to generate NO under physiological or pathological conditions of hypoxia.161,176,178,243,244 This selective bioactivation provides advantages for nitrite as a NO-generating therapeutic compared to other compounds, such as drug-conjugated NO-releasing moieties, S-nitrosothiols, and NONOates, which either undergo premature metabolism before reaching the target tissue or release NO indiscriminately, potentially giving rise to off-target side effects.

By serving as a supplemental source of NO, nitrite may be able to rescue impaired vasodilatory function in patients with hypertension or cardiovascular disease through direct modulation of the NO–sGC–cGMP pathway. Several translational studies have investigated the utility of inhaled, nebulized nitrite in the treatment of PAH associated with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (PAH-HFpEF).238,245–247 Acute, inhaled nitrite lowers pulmonary arterial pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and pulmonary vascular resistance in several preclinical and clinical studies of animals/patients with PAH-HFpEF.181,246,248,249 In a recent investigation of five patients with PAH associated with β-thalassemia, the pulmonary arterial pressure was shown to decrease immediately upon nitrite inhalation but returned to basal levels within 15 min of cessation of ventilation.250

Given the reversibility of cardiac outcomes observed with inhaled or infused nitrite treatment, numerous preclinical and clinical studies have investigated acute and long-term oral nitrite or nitrate supplementation as a means to achieve improvements in cardiac function in conditions linked to cardiovascular disease.251,252 As described above, nitrate can be reduced to nitrite by microorganisms in the oral microbiome,139,253,254 and dietary nitrate supplementation, particularly in beetroot juice and green leafy vegetables, has been utilized extensively as a pharmacological means to increase circulating nitrite levels in humans.167,244,255–257 Several clinical studies have shown that short- and long-term supplementation with oral nitrate reduces blood pressure in hypertensive patients.167,179,256,258–261 Contrary to these findings, other studies have shown no nitrate-dependent changes in blood pressure in hypertensive patients,262,263 although these differences may be due to underpowered study groups, differences in dosing, and variations in participant microbiomes that result in varied nitrate reductase activity and subsequent nitrite bioavailability.264–266 Our laboratory is currently conducting a placebo-controlled phase II clinical trial to examine how oral nitrite (40 mg three times a day for 10 weeks) effects exercise capacity and hemodynamic outcomes in PAH-HFpEF patients (NCT03015402). For a more complete summary of preclinical and clinical studies that probe the therapeutic potential of nitrite, we direct the reader to a recent review by Kapil et al.252

NITRITE-MEDIATED SIGNALING IN ORGANS AND TISSUES

Given its abundance, hemoglobin is likely the primary source of nitrite-derived NO in the vasculature; however, nitrite reductase activity has been observed in a wide variety of additional metalloproteins.60,251 Generally, nitrite reduction is facilitated by two metal-containing cofactors: heme and molybdopterin. Like hemoglobin, other heme-containing globin proteins, including myoglobin (Mb),216,267 neuroglobin (Ngb),268,269 and cytoglobin (Cygb),153,270 exhibit nitrite reductase activity (eq 7). Analogous reactivity has been observed in several nonglobin hemoproteins, including but not limited to eNOS,271 partially unfolded cytochrome c,272,273 cytochrome P450 2B4, and human cystathionine β-synthase.274,275 Molybdopterins comprise an additional class of redox-active metallocofactors that facilitate nitrite reduction via MoIV/V and MoV/VI redox couples. Nitrite reduction occurs more slowly when facilitated by molybdopterin compared to heme, and O2-sensitive molybdoenzymes, such as XOR, primarily contribute to nitrite bioactivation in tissues where nitrite accumulates at higher concentrations and O2 tensions are lower.276,277 Because this Forum Article focuses on hemoprotein reactivity, we direct the reader to other reviews that discuss molybdopterin-facilitated nitrite reduction in greater detail.278,279

Mb-Facilitated Nitrite Signaling in Tissue.

Myoglobin facilitates nitrite reduction in a mechanism analogous to that of hemoglobin and likely mediates NO signaling in cardiac and skeletal muscle tissues. The reaction rate constant for deoxymyoglobin (deoxyMb), 5.5 M−1 s−1 at 25 °C (12 M−1 s−1 at 37 °C), is comparable to that of R-state hemoglobin.216,280 NO dioxygenation is also nearly diffusion-limited in oxymyoglobin (oxyMb, second-order rate constant of 4.4 × 107 M−1 s−1 for equine oxyMb at 20 °C),200 so myoglobin may act as a NO sink, as well as a NO source. Under normoxic conditions, oxyMb likely scavenges NO, protecting mitochondrial proteins from the inhibition of enzymatic activity.281 Parallel NO-scavenging roles are proposed for cytoglobin and α-hemoglobin in vascular endothelial cells, where NO dioxygenation likely prevents excessive vasodilation.152,154,282,283 Under very low O2 tensions (P50 = 3 mmHg for Mb), such as those found in the ventricular walls of the heart, myoglobin may switch from NO scavenger (via dioxygenation) to NO source (via nitrite reductase).243 Thus, Mb-facilitated nitrite reduction likely contributes to the cardioprotective properties of nitrite.

Emerging Roles of Neuroglobin and Cytoglobin.

Two additional heme-containing globin proteins, neuroglobin and cytoglobin, have emerged in recent years as regulators of NO signaling. The expression patterns of these hemoproteins differ drastically from those of hemoglobin and myoglobin: neuroglobin is expressed at high levels (100–200 μM) in retinal cells and at low levels (~1 μM) in other tissues in the nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, and endocrine organs, while cytoglobin is ubiquitously expressed at low levels.284–288 Because neuroglobin and cytoglobin are not expressed at millimolar levels in tissues, these recently discovered globins likely do not play a significant role in gas exchange/O2 transport.

While the specific functions of neuroglobin and cytoglobin in different cellular contexts have not been fully elucidated, in vitro biochemical studies reveal that both proteins facilitate nitrite reduction. Unlike hemoglobin and myoglobin, the distal histidine in neuroglobin and cytoglobin serves as an axial heme ligand, and these proteins exist in equilibrium between distally bound and unbound states.286,289–291 This labile axial His ligand dictates small-molecule ligand binding and reactivity as the heme switches from a coordinatively saturated, six-coordinate environment to a coordinatively unsaturated, five-coordinate environment: e.g., a constitutively five-coordinate neuroglobin variant in which the distal His is mutated to a nonheme-coordinating leucine residue (H64L) exhibits nitrite reductase activity 3 orders of magnitude higher than that of the wild-type protein.268 Interestingly, the distal His binding equilibrium is allosterically regulated by the redox status of two Cys residues outside of the heme pocket. Under oxidizing conditions, a disulfide bridge forms between these two Cys residues (Cys46 and Cys55, which span the CD loop in Ngb; Cys38 and Cys83, which span B and E helices in Cygb), opening the heme pocket and favoring dissociation of the distal His ligand.268,270,292–296 Consequently, this redox-dependent modulation of heme coordination influences NO and nitrite reactivity in Ngb and Cygb. For example, both proteins exhibit faster nitrite reduction in the disulfide form (kS–S = 0.12 M−1 s−1 for Ngb and kS–S = 32.3 M−1 s−1 for Cygb, both at 25 °C) compared to the free thiol form (kS–H = 0.062 M−1 s−1 for Ngb and kS–H = 0.4–0.63 M−1 s−1 for Cygb, both at 25 °C),268,270 suggesting that the cellular redox environment can directly modulate protein reactivity.295 Protein oligomeric status may also influence ligand binding and reactivity because dimeric cytoglobin bearing intermolecular disulfides exhibits significantly diminished nitrite reductase activity (kS–S(dimer) = 0.26 M−1 s−1 for Cygb at 25 °C).270

Under O2-replete conditions, cytoglobin likely attenuates NO signaling by facilitating NO dioxygenation. While virtually all oxyferrous hemoproteins may participate in NO dioxygenation reactions in vitro (eq 2), this reaction results in the formation of iron(III) heme, which cannot undergo subsequent NO dioxygenation. This observation suggests that NO scavenging will be limited to stoichiometric reactions in vivo.297 Importantly, a coupled NADH/cytochrome b5/cytochrome b5 reductase system reduces iron(III) heme in cytoglobin,154 allowing for efficient cytoglobin redox cycling and NO scavenging under physiological conditions.155 Several in vivo studies suggest that Cygb-mediated NO scavenging in vascular endothelial cells prevents excessive vasodilation at high NO fluxes.155,282,298 As aforementioned, analogous NO scavenging is carried out by α-hemoglobin in vascular endothelial cells,152 and the precise interplay between cytoglobin and α-hemoglobin as NO-metabolizing regulators of the vascular tone requires further study.

Nitrite as a Cytoprotectant.

Nitrite-mediated cytoprotection in tissues has been studied extensively in the context of ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, and most of the cytoprotective mechanisms involve bioactivation of nitrite to generate NO.219 Under ischemic conditions, tissues become hypoxic and may also experience acidosis, leading to favorable nitrite reduction conditions by metalloproteins such as myoglobin.201 The specific metalloproteins responsible for nitrite reduction likely vary organ to organ based on conditions and expression levels. For example, in the ischemic heart, deoxyMb is likely the primary source of nitrite-derived NO: nitrite reduction in heart tissue was abolished in myoglobin global knockout mice,299 while allopurinol, a specific inhibitor of the molybdopterin enzyme XOR, only lessened nitrite-derived NO generation in heart homogenates by 10%216

In ischemic tissues, nitrite-derived nitrogen oxides primarily exhibit cytoprotective effects by targeting specific mitochondrial proteins.219 NO can directly nitrosylate the O2-reducing a3 heme site in complex IV of the electron-transport chain,300–302 slowing the rate of O2 consumption and ameliorating ischemic effects through preservation of high-energy phosphate reserves.299 As alluded, studies in vivo suggest that Mb-facilitated nitrite reduction is the primary source of NO in the heart: the absence of myoglobin abolished nitrite-dependent cytoprotection in a mouse model of cardiac I/R injury.299 Ischemic tissue acidosis would promote formation of N2O3 (eq 5), which can then modify electron-transport chain proteins, including complexes I and III as well as ATP-synthase, via S-nitrosation. These protein modifications confer cytoprotection during reperfusion by reversibly inhibiting enzymatic activity and curbing ATP synthesis and ROS production.219,303 Importantly, thiol nitrosation is temporary, and these enzymes recover normal activity over time after reperfusion.217 Finally, cytoprotection may also be conferred by a NO–sGC–cGMP-dependent mechanism that results in decreased mitochondrial calcium accumulation and ion permeability.304–306

Many animal models of I/R injury have demonstrated nitrite-dependent cytoprotection in all major organ systems; however, results from human clinical trials are variable, with nitrite exhibiting clear cytoprotective effects under certain pathological conditions and little protective effects under other conditions. Early pharmacokinetic and toxicity studies demonstrated the feasibility of nitrite infusion in the context of subarachnoid hemorrhage.180,307 In contrast, intravenous nitrite treatment showed dubious effects in two placebo-controlled phase II clinical trials studying acute myocardial infarction and I/R injury after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).308,309 However, in a follow-up study, Jones et al. also showed that localized intracoronary nitrite treatment prior to PCI attenuated immune response.310 In the context of organ-transplant-induced I/R injury, therapeutic NO inhalation increased plasma nitrite levels and conferred improved organ function and patient outcomes after lung and liver transplantation.311,312 Recently, a large (N = 1502), placebo-controlled phase II clinical trial assessed the therapeutic potential of nitrite administered to patients after cardiac resuscitation outside of a hospital setting (NCT03452917).313 In an earlier phase I trial, acute intravenous treatment of sodium nitrite (45 or 60 mg dose) did give rise to an increase in cGMP and nitrated fatty acid levels;314,315 however, nitrite intervention did not improve survival. Dose-dependent toxicity due to hypotension and methemoglobinemia limited the maximum safe dose for acute nitrite treatment,180,238 and such dose limitations may explain mixed therapeutic benefits observed in clinical trials. Taken together, these clinical results suggest that dose limitations curb the therapeutic benefit of global nitrite treatment; however, localized administration of nitrite at higher doses may improve outcomes in patients facing acute I/R injury.

“Oxidative” Nitrite Signaling: A Putative NO–sGC–cGMP-Independent Pathway.

Intriguing new preclinical research suggests that nitrite may also exhibit blood-pressure-lowering effects independent of NO, sGC, and cGMP in mesenteric resistance vessels.316 This hypothesis builds upon the observation that intermolecular disulfide formation at Cys42 in the α-subunit of PKG-1, the downstream target of cGMP, stabilizes a homodimer with enhanced kinase activity.317,318 By facilitating this disulfide formation, oxidants, such as H2O2 and persulfides (e.g., cysteine persulfide, CysSSH; glutathione persulfide, GSSH), bypass NO, sGC, and cGMP to induce vasodilation and lower blood pressure by directly acting on PKG-1.319 This H2O2-triggered vasodilation is ameliorated in resistance vessels from mice bearing a “redox-dead” Cys-to-Ser substitution that disrupts disulfide formation in PKG-1, and these mice exhibit hypertension in vivo.318 Recently, Feelisch et al. demonstrated that a single intra-peritoneal dose of nitrite exhibits long-lasting hypotensive effects in mice under normoxic conditions in a cGMP-independent manner consistent with this oxidative activation pathway.316 Nitrite treatment increased cellular levels of H2O2 and persulfide species in mesentery resistance vessels, concomitant with enhanced vasodilation. Nitrite-dependent vasodilation was not observed in the resistance vessels of “redox-dead” C42S mice nor were global nitrite-dependent hypotensive effects. The authors speculate that nitrite may indirectly increase H2O2 concentrations due to specific inhibition of catalase;320,321 however, other chemical and hemoprotein-facilitated nitrite reactions may give rise to oxidizing equivalents in tissue (Figure 2). Specifically, nitrite can react directly with oxyHb to generate H2O2 under O2-replete conditions (eq 16). Further studies are required to unravel the chemical and biochemical pathways that support “oxidative” nitrite signaling in this context.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

NO sits at the interface of inorganic chemistry, physiology, and biomedical research. Central to the interdisciplinary studies of NO are the interactions of this small molecule (and its related nitrogen oxides) with hemoproteins, particularly in the vasculature (Figure 4). Heme serves as the NO-sensing cofactor in the central target of NO signaling, sGC, and as the enzyme active site in NOS-dependent NO biosynthesis. Besides these central hemoproteins, which are dedicated to the canonical NO signaling pathway, many other hemoproteins, such as hemoglobin and myoglobin, facilitate nitrite-mediated signaling through a series of complex oxidative and reductive reactions. These auxiliary hemoprotein reactions unlock a “second axis” of NO signaling: nitrite serves as a stable NO reserve, which can be tapped under conditions of physiological and pathophysiological hypoxia, complementing O2-dependent NO biosynthesis by NOS enzymes.

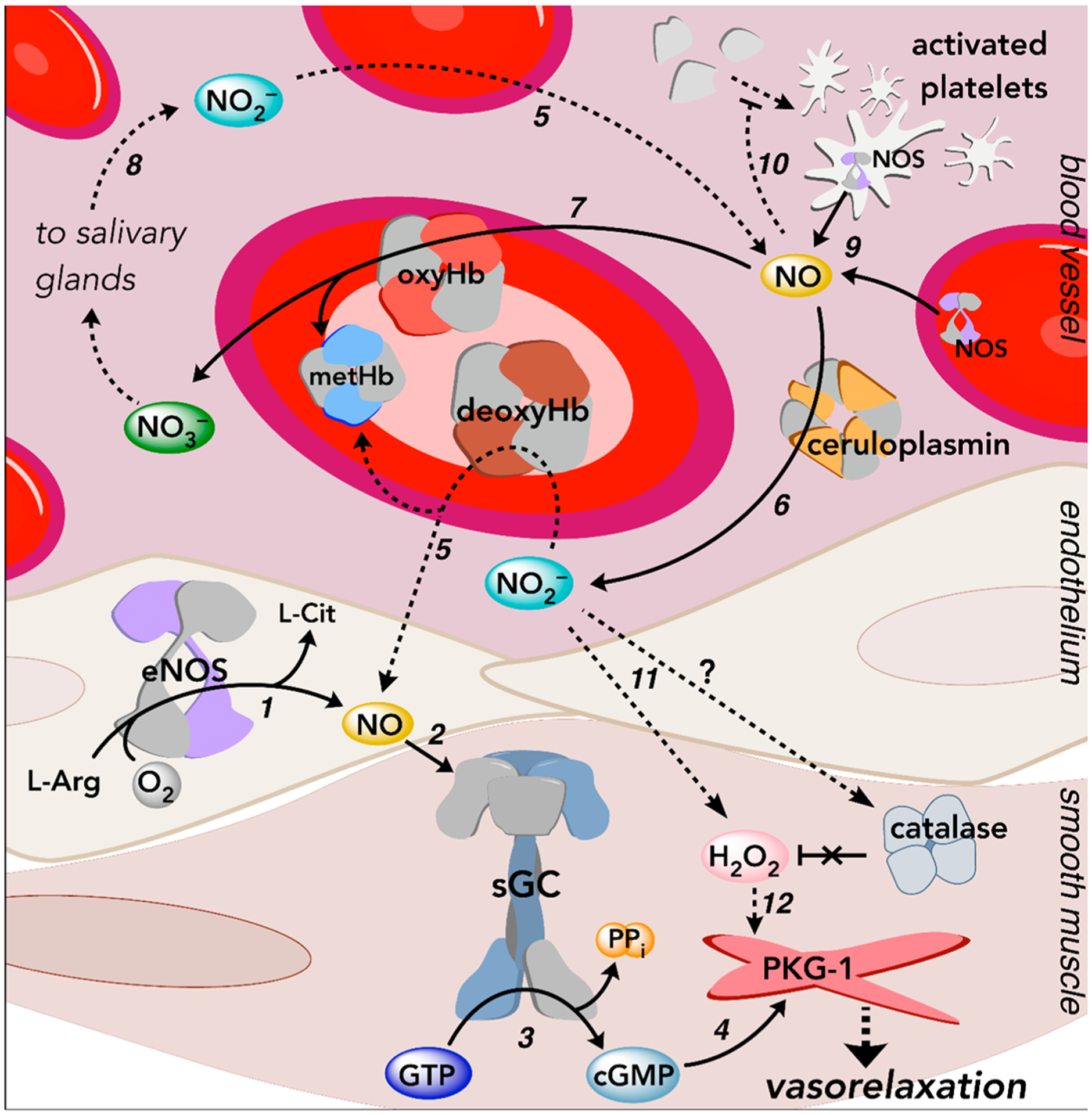

Figure 4.

Overview of NO and nitrite-mediated signaling pathways in the vasculature. Dashed arrows depict multistep signaling processes. (1) eNOS generates NO in the endothelium using l-arginine (l-Arg) and O2. (2) NO freely diffuses through cellular membranes into neighboring smooth muscle cells and binds sGC. (3) Activation of sGC results in the conversion of GTP to the second messenger cGMP. (4) cGMP binds to and activates PKG-1 in vascular smooth muscle cells, and PKG-1 subsequently phosphorylates downstream targets to regulate physiological processes, such as smooth muscle relaxation (i.e., vasorelaxation). (5) Inorganic nitrite acts as a stable NO reservoir. At low O2 tensions in the vasculature or under conditions of pathophysiological hypoxia, ferrous deoxyHb reduces nitrite to generate an equivalent of NO and ferric (met)Hb.176,178,193,194 Multiple hemoprotein-facilitated reactions regulate NO signaling and prevent overstimulation.194,203,205,232 (6) The multicopper-containing enzyme ceruloplasmin, found in the plasma, readily oxidizes NO to nitrite,145 while (7) oxyHb (and other O2-bound hemoproteins) rapidly oxidize NO to nitrate in a process called NO dioxygenation. (8) Nitrate can be carried throughout the plasma and concentrated in the salivary glands, where nitrate is secreted and metabolized by commensurate bacteria back to nitrite.141,142 Taken together, these processes (5–8) are collectively part of the nitrate–nitrite–NO pathway, a complementary, O2-independent route to NO. (9) eNOS is also found in RBCs and platelets, which contribute to regulation of the vascular tone.322–324 (10) NO, derived from eNOS and/or nitrite reduction, inhibits platelet activation via the canonical sGC pathway.186–189 (11) Nitrite may increase H2O2 levels by directly inhibiting catalase or reacting with hemoproteins under O2-replete conditions to generate H2O2.229–231 (12) Some evidence suggests that nitrite may therefore also regulate the vascular tone in a NO–sGC–cGMP-independent fashion in mesenteric resistance vessels by facilitating oxidative activation of PKG-1.316 More details regarding each of these pathways can be found in the main body of the text.

The multifaceted chemical reactivity and complex biological signaling pathways regulated by NO have posed many challenges in the development of a thorough understanding of this molecule’s role in human health and disease. However, these complexities have also presented researchers with novel therapeutic strategies that target NO-dependent signaling to treat a range of pathophysiological conditions from cardiovascular disease, organ transplant, infection, and oxidative stress. In particular, nitrite- and nitrate-based therapeutics have shown promise as modulators of NO signaling, and ongoing fundamental and clinical studies are exploring the applicability of localized and systemic nitrite and nitrate supplementation in the treatment of disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P01HL103455 and T32HL110849 (to M.T.G.) as well as Grant R01HL125886 (to M.T.G. and J.T.) and by the Institute for Transfusion Medicine and the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania (to M.T.G.). M.R.D. and A.W.D. are supported by Grant T32 HL110849.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): M.R.D., A.W.D., J.T., and M.T.G. are coinventors of provisional, pending, and/or granted patents for the use of recombinant neuroglobin and other heme-based molecules as antidotes for CO poisoning. Globin Solutions, Inc. has licensed this technology. J.T. and M.T.G. are shareholders in Globin Solutions, which has a sponsored research agreement with the University of Pittsburgh aimed at developing CO poisoning antidotes into therapeutics that partially supports the effort of M.T.G. and J.T. J.T. serves as an officer and director of Globin Solutions, where M.T.G. serves as a director and advisor. M.T.G. is a coinventor on patents directed to the use of nitrite salts in cardiovascular diseases licensed and exclusively optioned to Globin Solutions, Inc. M.T.G. is a coinvestigator in a research collaboration with Bayer Pharmaceuticals to evaluate riociguat as a treatment for patients with sickle cell disease. The financial conflicts of interest of M.R.D., A.W.D., J.T., and M.T.G. are managed by the University of Pittsburgh Conflict of Interest Committee and a data stewardship committee.

Footnotes

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c01048

Contributor Information

Matthew R. Dent, Heart, Lung, Blood, and Vascular Medicine Institute, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15261, United States.

Anthony W. DeMartino, Heart, Lung, Blood, and Vascular Medicine Institute, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15261, United States.

Jesús Tejero, Heart, Lung, Blood, and Vascular Medicine Institute, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15261, United States; Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine and Department of Pharmacology and Chemical Biology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15261, United States; Department of Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

Mark T. Gladwin, Heart, Lung, Blood, and Vascular Medicine Institute, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15261, United States; Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15261, United States; Department of Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Ignarro LJ; Wood KS; Wolin MS Activation of purified soluble guanylate cyclase by protoporphyrin IX. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1982, 79 (9), 2870–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ignarro LJ Signal transduction mechanisms involving nitric oxide. Biochem. Pharmacol 1991, 41 (4), 485–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Zhao Y; Brandish PE; Ballou DP; Marletta MA A molecular basis for nitric oxide sensing by soluble guanylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1999, 96 (26), 14753–14758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Roy B; Garthwaite J Nitric oxide activation of guanylyl cyclase in cells revisited. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103 (32), 12185–12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Evgenov OV; Pacher P; Schmidt PM; Haskó G; Schmidt HHHW; Stasch J-P NO-independent stimulators and activators of soluble guanylate cyclase: discovery and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2006, 5 (9), 755–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Giaid A; Saleh D Reduced Expression of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase in the Lungs of Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med 1995, 333 (4), 214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Pacher P; Beckman JS; Liaudet L Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol. Rev 2007, 87 (1), 315–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Stasch JP; Pacher P; Evgenov OV Soluble guanylate cyclase as an emerging therapeutic target in cardiopulmonary disease. Circulation 2011, 123 (20), 2263–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Sandner P; Zimmer DP; Milne GT; Follmann M; Hobbs A; Stasch J-P, Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulators and Activators. In Reactive Oxygen Species: Network Pharmacology and Therapeutic Applications; Schmidt HHHW, Ghezzi P, Cuadrado A, Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp 355–394. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Derbyshire ER; Marletta MA Structure and Regulation of Soluble Guanylate Cyclase. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2012, 81 (1), 533–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Koesling D; Mergia E; Russwurm M Physiological Functions of NO-Sensitive Guanylyl Cyclase Isoforms. Curr. Med. Chem 2016, 23 (24), 2653–2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Iyer LM; Anantharaman V; Aravind L Ancient conserved domains shared by animal soluble guanylyl cyclases and bacterial signaling proteins. BMC Genomics 2003, 4 (1), 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Mistry J; Chuguransky S; Williams L; Qureshi M; Salazar GA; Sonnhammer ELL; Tosatto SCE; Paladin L; Raj S; Richardson LJ; Finn RD; Bateman A Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49 (D1), D412–d419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Wedel B; Humbert P; Harteneck C; Foerster J; Malkewitz J; Böhme E; Schultz G; Koesling D Mutation of His-105 in the beta 1 subunit yields a nitric oxide-insensitive form of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1994, 91 (7), 2592–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Stone JR; Marletta MA Spectral and kinetic studies on the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase by nitric oxide. Biochemistry 1996, 35 (4), 1093–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Dierks EA; Hu S; Vogel KM; Yu AE; Spiro TG; Burstyn JN Demonstration of the Role of Scission of the Proximal Histidine-Iron Bond in the Activation of Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase through Metalloporphyrin Substitution Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119 (31), 7316–7323. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Montfort WR; Wales JA; Weichsel A Structure and Activation of Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase, the Nitric Oxide Sensor. Antioxid. Redox Signaling 2017, 26 (3), 107–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ma X; Sayed N; Baskaran P; Beuve A; van den Akker F PAS-mediated dimerization of soluble guanylyl cyclase revealed by signal transduction histidine kinase domain crystal structure. J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283 (2), 1167–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ma X; Beuve A; van den Akker F Crystal structure of the signaling helix coiled-coil domain of the beta1 subunit of the soluble guanylyl cyclase. BMC Struct. Biol 2010, 10, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Allerston CK; von Delft F; Gileadi O Crystal structures of the catalytic domain of human soluble guanylate cyclase. PLoS One 2013, 8 (3), No. e57644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Seeger F; Quintyn R; Tanimoto A; Williams GJ; Tainer JA; Wysocki VH; Garcin ED Interfacial residues promote an optimal alignment of the catalytic center in human soluble guanylate cyclase: heterodimerization is required but not sufficient for activity. Biochemistry 2014, 53 (13), 2153–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Sunahara RK; Beuve A; Tesmer JJG; Sprang SR; Garbers DL; Gilman AG Exchange of Substrate and Inhibitor Specificities between Adenylyl and Guanylyl Cyclases. J. Biol. Chem 1998, 273 (26), 16332–16338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Sinha SC; Sprang SR Structures, mechanism, regulation and evolution of class III nucleotidyl cyclases. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol 2006, 157, 105–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Ignarro LJ; Degnan JN; Baricos WH; Kadowitz PJ; Wolin MS Activation of purified guanylate cyclase by nitric oxide requires heme comparison of heme-deficient, heme-reconstituted and heme-containing forms of soluble enzyme from bovine lung. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj 1982, 718 (1), 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Yu AE; Hu S; Spiro TG; Burstyn JN Resonance Raman Spectroscopy of Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase Reveals Displacement of Distal and Proximal Heme Ligands by NO. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116 (9), 4117–4118. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Stone JR; Marletta MA Soluble guanylate cyclase from bovine lung: activation with nitric oxide and carbon monoxide and spectral characterization of the ferrous and ferric states. Biochemistry 1994, 33 (18), 5636–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Burstyn JN; Yu AE; Dierks EA; Hawkins BK; Dawson JH Studies of the heme coordination and ligand binding properties of soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC): characterization of Fe(II)sGC and Fe(II)sGC(CO) by electronic absorption and magnetic circular dichroism spectroscopies and failure of CO to activate the enzyme. Biochemistry 1995, 34 (17), 5896–5903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Stone JR; Sands RH; Dunham WR; Marletta MA Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectral Evidence for the Formation of a Pentacoordinate Nitrosyl-Heme Complex on Soluble Guanylate Cyclase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1995, 207 (2), 572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Stone JR; Babcock GT; Marletta MA; Deinum G Binding of Nitric Oxide and Carbon Monoxide to Soluble Guanylate Cyclase as Observed with Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Biochemistry 1996, 35 (5), 1540–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]