Abstract

Sexual health may be disrupted in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) both during and after cancer treatment, irrespective of whether they are diagnosed in childhood, adolescence or young adulthood. Unfortunately, oncology providers often underestimate the relevance of psychosexual issues for AYAs and under-prioritize sexual health throughout treatment andsurvivorship. The purpose of this narrative review is to provide information on (a) the etiology of psychosexual dysfunction in childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer patients and young adult survivors of childhood cancer;(b) strategies for communicating and evaluating potential sexual health issues AYA patients/survivors; and (c) guidance for the practicing pediatric oncologist on how to address sexual health concerns with patients.

Keywords: Sexual health, sexual dysfunction in pediatric cancer survivors, psychosexual health, adolescent and young adult cancer

I. Introduction

Sexual health is a domain extending across physical health, emotional health, and quality of life which may be disrupted in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) both during and after cancer treatment, irrespective of whether they are diagnosed in childhood, adolescence or young adulthood. The World Health Organization defines sexual health as “a state of physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction, or infirmity, in all matters relating to the reproductive system, its functions, and its processes.”(1) Adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients and survivors may be particularly susceptible to impaired sexual health given the specific developmental tasks and sexual milestones which are typically attained during this life period which includesformation of intimate relationships with peers and romantic partners, development of body image, sexuality, sexual identity and orientation, consideration of fertility andfamily planning/contraception, and psychosexual adjustment, all while navigating the physical and psychological changes brought on by cancer treatment.This necessitates receipt of medically accurate, developmentally appropriate, and tailored sexual health education along with access to associated clinical services as relevant to the patient, cancer diagnosis and/or stage of treatment.(2)While the defined age range for AYAs varies by country and organization, in the United States this is generally includes thoseaged 15–39 years(3), and encompasses adolescence, emerging and young adulthood.(4)

Nearly half of AYA childhood cancer survivors (CCS) perceive negative impact of cancer on their sexual lives.(5–7)While CCS report engaging in sexual activity less frequentlyand have poorer sexual function following cancer treatment(8), some data support participation in risky sexual behaviors at rates similar to peers.(9)One large study found significant rates of sexual difficulty/dysfunction amongyoung adult CCS in which 30% reported no/low sexual desire, 23%noted impaired arousal, and 29% reported orgasmic dysfunction.(10)Compared with same-age peers, young adult CCStend to have delayed attainment of sexual milestones includingolder age at first intercourse,(5, 11) fewer lifetime sex partners,(12) and are less likely to marry.(13)Collectively,these data suggest that many young adult CCS may experience problems with their sexual health thereby warranting a need for oncologyproviders to be prepared to discuss sexual health-related issues with their patients.(10)

Oncology providers often underestimate the relevance of psychosexual issues among AYAs and are less likely to discuss sexual health across the course of cancer treatment and into survivorship.(14)The purpose of this narrative review is to provide information on (a) the etiology of psychosexual dysfunction in childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer patients and young adult survivors of childhood cancer;(b) strategies for communicating and evaluating potential sexual health issues AYA patients/survivors; and (c) guidance for the practicing pediatric oncologist on how to address sexual health concerns with patients.

II. How Cancer Treatment May Adversely AffectSexual Function in Males

Sexual dysfunctions among males may include disorders of interest/desire, arousal, orgasm, and pain during sexual activity.Ten to thirty two percent of males surviving childhood cancer will experience sexual dysfunction in adulthood,(15–19) with survivors experiencing a 2.6-fold increased risk for erectile dysfunction (ED) relative to siblings.(20)Beyond these physical issues, problems with psychosexual dysfunction including poor body image, low sexual interest and satisfaction have also been reported.(16, 20–23) Sexual dysfunction in this population has also been associated with poorer physical and emotional functioning,(15) highlighting the need to address this topic more systematically in survivorship.(24)Male sexual function relies on an intact neuroendocrine axis, penile innervation, and penile vasculature; impairment in any/all of these physiologic processes may be a consequence of chemotherapy, radiation, and/or surgery.(24) Erectile or ejaculatory dysfunction can be caused by tumor compression, or surgery/radiation involving the lower spinal cord, pelvis, bladder, distal colon, or rectum.(25, 26) Targeted radiotherapy and nerve sparing approaches have been shown to help preserve post-operative function.(25, 27)

Sexual dysfunction may also be caused by secondary/central hypogonadism (i.e. low testosterone due to gonadotropin deficiency) or primary hypogonadism (i.e. low testosterone due to testicular dysfunction). Secondary/central hypogonadism may occur due to disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis by tumor invasion, central nervous system surgery, or radiation ≥30 Gy,(28) though some studies have also shown gonadotropin deficiency in patients who received ≥22 Gy.(29)Primary hypogonadism most commonly occurs due to exposure to alkylating (cyclophosphamide equivalent dose >20 g/m2(30)) and/or platinum-derived agents, total body irradiation, testicular irradiation, or orchiectomy.(31) Dose-response relationships between testicular radiation and hypoandrogenism have not been clearly identified, with risk thresholds ranging from ≥12–30 Gy(28, 30)and prepubertal males appear more sensitive to effects of testicular irradiation.(32)

Several studies on gonadal function in testicular cancer survivorsdemonstrate impairment. One study showed survivors of stage I testicular germ cell carcinoma had insufficient Leydig cell function one year after unilateral orchiectomy, though it was unclear whether these men would develop permanent hypogonadism.(33)Pre-surgical hypogonadism and testicular microlithiasis are predictive factors for post-treatment hypogonadism;(34) age of survivors also needs to be taken into account, as primary hypogonadism is associated with aging in males.(35)Long-term satisfaction with testicular prostheses appears to be fair, though one study showed 15% indicated their prostheses interfered with sexual activity.(36)Despite the variety of interventions available (e.g., pharmacologic therapies, external erection-facilitating devices, surgical options, psychological intervention, etc.), fewer than 6% of survivors report receiving ED treatment(20).

III. How Cancer Treatment May Adversely AffectSexual Function in Females

Sexual dysfunction among femalesincludes disorders of interest/desire, arousal, orgasm, and pain during sexual activity. Approximately 20–29% of female CCS report impairment in sexual function (15, 37, 38) and, on average, report greater sexual dysfunction in survivorship relative to males.(15, 16, 37, 39) Risk factors for sexual dysfunction in this group include specificcancer types (e.g., germ cell tumors, renal tumors, and leukemia(38), and treatment factors (e.g., cranial, pelvic or total body irradiation, stem cell transplant)along with associated late effects (e.g., ovarian failure, untreated hypogonadism, LH/FSH deficiencies), and developmental factors (e.g.,age and developmental stage at diagnosis and treatment factors (8, 40, 41).Chemotherapy, primarily alkylating agents and heavy metals, and radiation to the ovaries are associated with premature ovarian insufficiencyand ovarian failure,both of which decrease estrogen, which has a significant negative impact on the vaginal tissue.(42–44)Central gonadotropin deficiency due to disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis is also a concern among female cancer patients whose tumor or cancer treatment involves the hypothalamus/pituitary, and central hypogonadism is seen with doses of cranial radiation ≥30 Gy. Females who receive high doses of alkylating agents (≥7.5 g/m2 for post-pubertal and ≥12 g/m2 for pre-pubertal) (personal communication with Dr. Lillian Meacham), radiation tothe ovaries, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, or a combination of these therapies are at highest risk for hormonal disruption after cancer treatment.(45)Unilateral oophorectomy is associated with early menopause (46); bilateral oophorectomy is uncommon among children with cancer, but when indicated, results in a complete cessationof ovarian hormone production.

Vaginal dryness and pain during intercourse are common treatment sequelae reported by survivors of childhood cancer.(22)Radiation to the pelvis can result in vaginal dryness and/or scarring of the vulvar/vaginal tissue, all of which can lead to pain during intercourse.(47) Chronic graft-vs-host disease, a long-term complication of allogenic hematopoietic cell transplant, can result in vulvar scarring or vaginal fibrosis/stenosis.(48)Surgeries, including spinal/neurosurgeryand pelvic surgery, can place patients at risk for nerve damage and potential sexual dysfunction.(26, 49) Limited research has assessed the impact of therapeutic exposures and sexual dysfunction among CCS.

Sexual dysfunction in females surviving cancer is often treatable, and interventions will vary based on etiology and symptoms; therefore a biopsychosocial approach to assessment and treatment is recommended.(50, 51) Intervention approaches may be specific to a sub-specialty or multidisciplinary in nature and may involve medical (e.g., exogenous estrogen or estrogen receptor modulators, androgen or antidepressant therapy) or non-medical approaches (e.g., physical therapy, psychotherapy, lubricants, dilators/devices, etc.). Although 41% of female survivors perceive themselves at-risk for sexual dysfunction, fewer than 3% report having received any intervention.(38) Nevertheless, young adult survivors of childhood cancer describeclinically significant sexual health concerns as well as interruption of psychosexual development, altered perceptions of body image, physical and psychological problems.(22)

IV. The Potential Adverse Impact of Cancer on Psychosexual Development

Immediate and late effects of childhood cancer treatment can directly and/or indirectly affect young survivors’ physical and emotional development via altered body image or cognitive difficulties, which may impair ability to engage in romantic and sexual relationships. The development of one’s sexual identity developsthrough adolescence, which leads to an understanding of the self as a sexual being. Physical attractiveness and positive self-esteem are key components in this process.(52) Thus,cancer treatment during early childhood while coping with potential long-term side effects can be different from being diagnosed throughout adolescence.(53, 54) Experiencing acute side effects like baldness, weight changes, or fatigue, as well as longer-term side effects, like scars, physical disability, and cognitive function, can negatively impact social/interpersonal relationships, diminish autonomy, and contribute to difficulties obtaining sexual health knowledge.Taken together, these can diminish sexual opportunities and delay or impair developmentally appropriate exploration of sexual identity.(55–57) Thus, apart from diverse physical side effects which can cause emotional and social difficulties, the time of diagnosis may indirectly affect psychosexual development.

Research on psychosexual development among CCS is sparse, and the heterogeneity of CSS, due to the wide age range at diagnosis and diverse types of diagnoses, represents an additional challenge for drawing specific conclusions. Early studies found thatCCS were less likely to marry(13, 58–62),have children(59, 63, 64), be sexually experienced (37, 58, 65, 66),and/or had lower numbers of different sex partners.(23, 67) However, more recent studies suggest that some survivors only delay certain milestones to a later age(63, 66, 68), while others may rush into romantic relationships to achieve normality.(69, 70)Studies also demonstrate that survivors of childhood cancer engage in risky sexual behaviors at rates similar to healthy peers.(9)Survivors have described the interruption of adolescence due to cancer therapy as negatively impacting relationship development.(37) AYA patients also report missing out on romantic and sexual milestones and feeling isolated from peers while undergoing cancer treatment.(22)

A considerable number of CCS identify concerns and/or struggles with romantic relationships and intimacy due to the belief that they are a less valuable dating partner.(22, 71) CCS expressed self-consciousness about their bodies that adversely affected being physically intimate with another person(22, 69, 72–74), and distress about disclosing a past cancer diagnoses to a potential partner(71, 74, 75), particularly if this also included disclosure of potential infertility.(74–77)Concerns about dating, finding a partner, and/or infertility may be more common among female survivors (77, 78), but it remains unclear if such concerns are indeed more prevalent among females or if they are more likely to express them.Nevertheless, many survivors also reported close emotional bonds with others and being appreciative of interpersonal relationships.(71, 77)

Given the limited numberof large-scale and in-depth studies on psychosexual developmental among CCS, few risk factors for impaired psychosexual development and sexual intimacy have been identified. Next to psychological phenomena like low self-esteem and negative body image, some studies indicate that brain tumor survivors(13, 59, 79) or any survivor treated with high-dose neurotoxic treatment regimens,may be at risk for impaired psychosexual development.(80)Age at diagnosis may be another crucial factor, given that cancer during adolescence could directly hinder exploration of sexuality, resulting in survivors who are less sexually experienced.(5, 54) Treatment during adolescence creates increased time in the hospital away from peers, and increased supervision from parents at a time when developing autonomy is crucial. Such lacking opportunities for exploration are not only limited to sexual intimacy, but also experimenting with sexual orientation.(81)

V. Considerations for AYAson Active Treatment

Sexual health of AYAs undergoing cancer treatment may be overlooked by clinicians(82, 83). Oncology providers may assume the patients will not feel well enough to be sexually active or may assume the adolescent is not yet sexually active. However, in the United States for example, nearly half (46.8%) of high school students have ever had sexual intercourse.(84) Although the literature is scant with regard to guidelines for sexual activity during active cancer treatment, there are several points of discussion that should be addressed prior to and during treatment.

First, inquiries about parenthood goals should be assessed before treatment so that referrals and counsel on fertility preservation can be offered. Second, addressing contraception is imperative as AYAs may assume a discussion about potential infertility means they are not capable of siring a pregnancy or becoming pregnant.(85) Contraception is important not only for the prevention of pregnancy but also for prevention of sexually transmitted infections. Moreover, providers should not assume a patient is heterosexual nor in an exclusive or monogamous relationship.Third, normalization of sex-related topics, refraining from judgement, and direct questions about AYAs’ number of partners and type of sexual activity can guide discussions about what precautions should be taken, tailored to the AYA’s type of cancer and treatment as well as activity and partners. Such conversations should take place without parents being present. Fourth, counsel should be offered about the risks associated with penetrative or oral sex for patients with low blood counts or who are neutropenic. Depending on the type of cancer treatment, some patients may be cautioned to always use condoms and/or dental dams during active treatment to prevent partner’s exposure to the chemotherapeuticagents,but specific guidelines on the duration of using such protection is unclear.(86) In general, AYAs who wish to be sexually active while on treatment should be encouraged and anticipatory guidance should be offered in relation to managing common treatment side-effects such as fatigue, decreased desire, vaginal dryness or erectile dysfunction. Many AYAs fear losing a partner or the termination of relationship if they cannot perform sexually.In such cases where patients are concerned about the status of their intimate relationships, counsel may be offered on alternate ways to create intimacy with a partner.

VI. The Role of Pediatric Providers

Several leading organizations highlight the need for pediatric hematology/oncology clinicians to address sexual health with AYApatients. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends pediatricians provide confidential time during a visit to discuss sexuality, sexual health promotion, and risk reduction.(87) The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) states that “Fertility preservation as well as sexual health and function should be an essential part in the management of AYAs with cancer.” (88)The American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends that “there be a discussion with the patient, initiated by a member of the health care team, regarding sexual health and dysfunction resulting from cancer or its treatment. Psychosocial and/or psychosexual counseling should be offered to all patients with cancer, aiming to improve sexual response, body image, intimacy and relationship issues, and overall sexual functioning and satisfaction.”(51)

Despite these recommendations, sexual health conversations rarely take place.(22, 83) Research exploring AYA patient-reported barriers to communication show that current communication gaps are exacerbated by patient discomfort in initiating these conversations, along with the presence of family members.(83)Clinician-reported barriers include lack of knowledge/experience, lack of resources/referrals, low priority in the context of other cancer care needs, presence of parents/family members at visits, perceived patient discomfortwhen discussing sexual health issues, clinician discomfortin discussing sexual health topics, limited time, and lack of rapport between the AYA and clinician.(82)

While there is a clear need for clinician-centered education on common sexual health questions and problems faced by AYAs during and after cancer therapy, clinicians must also have a clear understanding of how to initiate sexual health conversations to appropriately identify issues and provide effective patient education and intervention.Research focused on promoting fertility and fertility preservation communication demonstrates the efficacy of using scripts to help facilitate clinician comfort with conversations.(89) Additionally, the use of pre-visit patient-centered screening forms or questionnaires may be successful in identifying sexual health communication needs of AYA patients, thereby providing guidance to the clinician prior to meeting with the patient.(90)The oncology clinician may partner with a psychologist, medical social worker, or nurse to help assist in the assessment process.

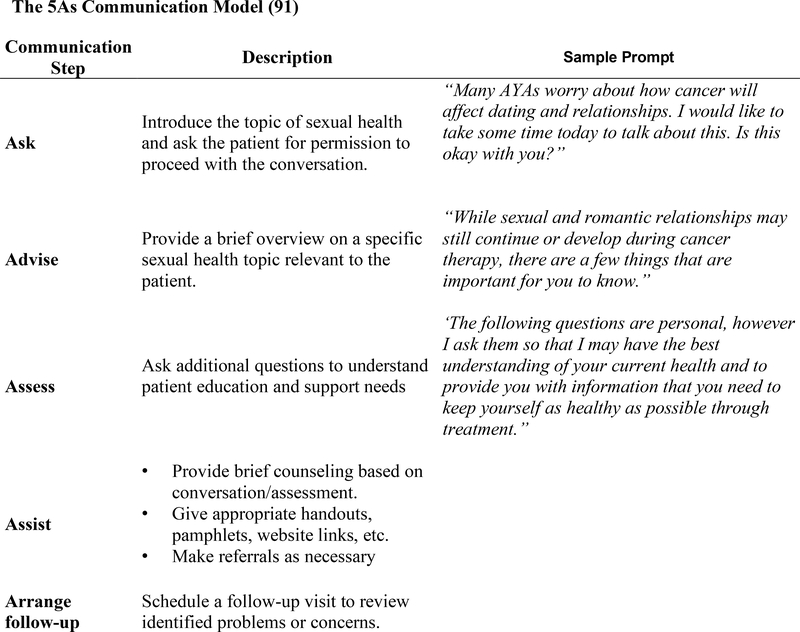

There are several evidence-based strategies developed to guide clinicians through sexual health conversations. One approach is the 5 As (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange)communication model (Fig. 1), which is shown to be an effective strategy used in adult cancer patients for the purpose of discussing sexual health, and is potentially adaptable to the AYA patient population.(91) Additional communication models, such as the extended PLISSIT or 5 Ps models may also be considered for adaptation to the AYA patient population.(87, 92) These models are similar in that they start by guiding the clinician to introduce the topic of sexual health and ask the AYA for permission to proceed with the conversation. This is followed by providing patients with a brief overview on a specific sexual health topic which, depending on the patient, may include puberty/development, contraception, safe sex practices, and/or sexual function. The clinician will then ask the AYA additional questions to understand his or her education and support needs followed by provision of brief counseling and/or making referrals as appropriate (urology, OB/GYN, reproductive endocrinology, adolescent medicine, psychology, etc.). Finally, it is critical that the clinician schedule follow up visits to review the identified problems or concerns and ensure that they are being addressed.

Figure 1.

The 5As Communication Model

Importantly, AYAs have also provided recommendations for clinicians on how to approach sexual health conversations. These recommendations include that the clinicianshould initiate the conversation, offer time alone to speak privately without the presence of parents or other individuals, normalize the conversation, engage in ongoing conversation throughout cancer treatment and survivorship, tailor the conversation to the patient by considering his/her age and developmental stage, gender and gender identify, sexual orientation, sexual activity, cancer type and treatment course,and communicate directly with the AYA (i.e. do not rely on packets, websites, etc.(83, 87).

While pediatric oncology clinicians may play a key role in providing general education and screening for sexual health issues in AYAs, it is important to consider a multidisciplinary approach that includes utilizing existing expertise within a hospital, available referral networks, and comfort and expertise of clinicians directly interacting with patients. Pediatric cliniciansshould be cautious in treating sexual dysfunction as this is generally outside their scope of care and carries potential for harm, underlining the importance of an appropriate referral network. However, as detailed above, it is incredibly important to start these conversations and allow patients to feel comfortable talking about sexual health questions and concerns. (91, 93, 94)

VII. Building a Multidisciplinary Support Team

There are a variety of ways to create teams but the best start may be with institutional/practice policy.(95)Such guidelines may also aid in development of consistent practice across teams and clinics. Identifying team members such as allied health professionals (e.g., nurses, social workers, psychologists, sexologists, physician assistants, physical therapists, etc.) who have the proper experience and skills to communicate about sexual health with AYAs may improve the likelihood that counsel is offered and reduce the burden of time from the oncologist. Resources for additional training among team members should also be available.(Table 1)To enhance patient care coordination of sexual healthissues that may arise during and after cancer treatment, it may be helpful to document conversations and/or recommendations in the medical record. Prior research demonstrates that lack of documentation of fertility conversations, a key component of sexual health,correlates with poor patient-provider communication regarding fertility.(96)Further, such documentation can help with survivorship care planning. For example,discussions of contraception may be needed and may differ from time of diagnosis into survivorship. A standard approach to documentation may enhance communication amongst multiple team providers and highlights both short and long-term care needs of a patient regarding sexual health status, current issues or concerns, necessary referrals, andfollow-up needs.

TABLE 1.

Resources for Further Education

| Resource | Summary | Website |

|---|---|---|

| American Society for Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Webinar: Addressing Sexual Health in AYA Patients with Cancer | Online webinar designed for the pediatric oncology provider to provide education on sexual health care issues faced by AYA patients and survivors and strategies for discussing sexual health with these patients. | http://aspho.org/knowledge-center/kc-overview |

| American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Guidelines | Guidelines on how to manage sexual function adverse effects that occur as a result of cancer diagnosis and/or treatment. Targets patients >18 years and excludes childhood cancer survivors. | https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JCO.2017.75.8995 |

| Enriching Communication in Reproductive Health and Oncofertility (ECHO) | An eLearning training program aimed to enhance knowledge and communication skills related to fertility and sexual health in cancer patients. This program is aimed at social workers, psychologists, nurses, and physician assistants. | https://echo.rhoinstitute.org/ |

| Will 2 Love | Online interactive website that aims to assist clinicians and health organizations manage patients with sexual health and fertility problems due to cancer and other conditions. Specific training available for oncology clinicians. Program currently targets adults. Annual fee $600. | https://www.will2love.com/ |

| Scientific Network for Female Sexual Health in Cancer | A global interdisciplinary network of clinicians, researchers and healthcare professionals who work to promote sexual well-being in women and girls affected by cancer by advancing evidence-based education and practice. | http://www.cancersexnetwork.org/ |

Finally, developing a list of resources and referrals such as peer support groups, endocrinologists, and therapists will also help streamline the ability to address each patient’s specific needs. Having written material about sexual function and potential solutions that is developmentally appropriate and context-specific is also a key component of quality care. Such materials may be in the form of a brochure or available on a website. The information provided should be inclusive of all sexual orientations and gender identities and should seek to normalize the idea that psychosexual dysfunction during and after cancer treatment is to be expected and that solutions and referrals are available.

VIII. Conclusions

Sexual health is a critical component of comprehensive care for the AYA oncology patient during treatment and through survivorship. Providers caring for these patients must have an understanding of not only how sexual health may be adversely impacted by cancer treatment, but the skillset to discuss developmentally appropriate aspects of sexual health, provide counsel, and address potential problems. This may require building a support network of clinical experts to assist in patient care and to make appropriate referrals and consistent documentation in the medical record. AYAs have repeatedly prioritized the need for improved sexual health care.There is ongoing need to re-visit established guidelines for preventative measures related to psychosexual health during and after treatment as well as consideration of new evidenced guidelines based on future research.Future research may explore optimal clinician training strategies to help overcome communication barriers and facilitate conversations around specific sexual health topics. Additional areas of exploration also include the development of educational materials and interventions to identify patients most at risk for and to prevent impairment of psychosexual development and sexual functioning.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure

Dr. Nahata is funded by the National Cancer Institute (1K08CA237338-01). The remaining authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Abbreviation

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- ASCO

American Society of Clinical Oncology

- AYA

Adolescent and Young Adult

- COG

Children’s Oncology Group

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- CCS

Childhood Cancer Survivors

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Organization WH. Defining Sexual Health: Report of a Technical consultation on Sexual Health. Geneva, Switzerland; 2002.

- 2.Murphy D, Klosky JL, Reed DR, Termuhlen AM, Shannon SV, Quinn GP. The importance of assessing priorities of reproductive health concerns among adolescent and young adult patients with cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(15):2529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Group AaYAOR. Closing the gap: Research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Report of the Adolescent and Young Adult Progress Review Group US Department of Health and Human Services US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute and LiveStrong Young Adult Alliance. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Dijk E, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Kaspers G, Van Dam E, Braam K, Huisman J. Psychosexual functioning of childhood cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17(5):506–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wettergren L, Kent EE, Mitchell SA, Zebrack B, Lynch CF, Rubenstein MB, et al. Cancer negatively impacts on sexual function in adolescents and young adults: The AYA HOPE study. Psycho-Oncology. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geue K, Schmidt R, Sender A, Sauter S, Friedrich M. Sexuality and romantic relationships in young adult cancer survivors: satisfaction and supportive care needs. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24(11):1368–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford JS, Kawashima T, Whitton J, Leisenring W, Laverdière C, Stovall M, et al. Psychosexual functioning among adult female survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2014:JCO. 2013.54. 1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klosky JL, Foster RH, Li Z, Peasant C, Howell CR, Mertens AC, et al. Risky Sexual Behavior in Adolescent Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Health Psychol. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bober SL, Zhou ES, Chen B, Manley PE, Kenney LB, Recklitis CJ. Sexual function in childhood cancer survivors: a report from Project REACH. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2013;10(8):2084–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerhardt CA, Vannatta K, Valerius KS, Correll J, Noll RB. Social and romantic outcomes in emerging adulthood among survivors of childhood cancer. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(5):462 e9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson AL, Marsland AL, Marshal MP, Tersak JM. Romantic relationships of emerging adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18(7):767–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janson C, Leisenring W, Cox C, Termuhlen AM, Mertens AC, Whitton JA, et al. Predictors of marriage and divorce in adult survivors of childhood cancers: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2009;18(10):2626–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson K, Dyson G, Holland L, Joubert L. An exploratory study of oncology specialists’ understanding of the preferences of young people living with cancer. Soc Work Health Care. 2013;52(2–3):166–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bober SL, Zhou ES, Chen B, Manley PE, Kenney LB, Recklitis CJ. Sexual function in childhood cancer survivors: a report from Project REACH. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10(8):2084–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zebrack BJ, Foley S, Wittmann D, Leonard M. Sexual functioning in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19(8):814–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kornblith AB, Anderson J, Cella DF, Tross S, Zuckerman E, Cherin E, et al. Comparison of psychosocial adaptation and sexual function of survivors of advanced Hodgkin disease treated by MOPP, ABVD, or MOPP alternating with ABVD. Cancer. 1992;70(10):2508–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Relander T, Cavallin-Stahl E, Garwicz S, Olsson AM, Willen M. Gonadal and sexual function in men treated for childhood cancer. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;35(1):52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Iersel L, Li Z, Chemaitilly W, Schover LR, Ness KK, Hudson MM, et al. Erectile Dysfunction in Male Survivors of Childhood Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(11):1613–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritenour CW, Seidel KD, Leisenring W, Mertens AC, Wasilewski-Masker K, Shnorhavorian M, et al. Erectile Dysfunction in Male Survivors of Childhood Cancer-A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. The journal of sexual medicine. 2016;13(6):945–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haavisto A, Henriksson M, Heikkinen R, Puukko-Viertomies LR, Jahnukainen K. Sexual function in male long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2016;122(14):2268–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frederick NN, Recklitis CJ, Blackmon JE, Bober S. Sexual Dysfunction in Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(9):1622–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundberg KK, Lampic C, Arvidson J, Helstrom L, Wettergren L. Sexual function and experience among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2011;47(3):397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenney LB, Antal Z, Ginsberg JP, Hoppe BS, Bober SL, Yu RN, et al. Improving Male Reproductive Health After Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer: Progress and Future Directions for Survivorship Research. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(21):2160–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zippe C, Nandipati K, Agarwal A, Raina R. Sexual dysfunction after pelvic surgery. International journal of impotence research. 2006;18(1):1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albright TH, Grabel Z, DePasse JM, Palumbo MA, Daniels AH. Sexual and Reproductive Function in Spinal Cord Injury and Spinal Surgery Patients. Orthopedic reviews. 2015;7(3):5842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahmood J, Shamah AA, Creed TM, Pavlovic R, Matsui H, Kimura M, et al. Radiation-induced erectile dysfunction: Recent advances and future directions. Advances in radiation oncology. 2016;1(3):161–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenney LB, Cohen LE, Shnorhavorian M, Metzger ML, Lockart B, Hijiya N, et al. Male reproductive health after childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(27):3408–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chemaitilly W, Li Z, Huang S, Ness KK, Clark KL, Green DM, et al. Anterior hypopituitarism in adult survivors of childhood cancers treated with cranial radiotherapy: a report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(5):492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mostoufi-Moab S, Seidel K, Leisenring WM, Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, Stovall M, et al. Endocrine Abnormalities in Aging Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(27):3240–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brignardello E, Felicetti F, Castiglione A, Nervo A, Biasin E, Ciccone G, et al. Gonadal status in long-term male survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2016;142(5):1127–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shalet SM, Tsatsoulis A, Whitehead E, Read G. Vulnerability of the human Leydig cell to radiation damage is dependent upon age. The Journal of endocrinology. 1989;120(1):161–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandak M, Aksglaede L, Juul A, Rorth M, Daugaard G. The pituitary-Leydig cell axis before and after orchiectomy in patients with stage I testicular cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(17):2585–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eberhard J, Stahl O, Cwikiel M, Cavallin-Stahl E, Giwercman Y, Salmonson EC, et al. Risk factors for post-treatment hypogonadism in testicular cancer patients. European journal of endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2008;158(4):561–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sprauten M, Brydoy M, Haugnes HS, Cvancarova M, Bjoro T, Bjerner J, et al. Longitudinal serum testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone levels in a population-based sample of long-term testicular cancer survivors. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(6):571–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yossepowitch O, Aviv D, Wainchwaig L, Baniel J. Testicular prostheses for testis cancer survivors: patient perspectives and predictors of long-term satisfaction. The Journal of urology. 2011;186(6):2249–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Dijk EM, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Kaspers GJ, van Dam EW, Braam KI, Huisman J. Psychosexual functioning of childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2008;17(5):506–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bjornard K HC, Klosky JL, Chemaitilly W, Srivastava DK, Brinkman TM, Green DM, Willard VW, Jacola L, Krasin M, Hudson MM, Robison LL, &, KK N. Psychosexual function in sexually active female survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(7):136.29220298 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrera M, Teall T, Barr R, Silva M, Greenberg M. Sexual function in adolescent and young adult survivors of lower extremity bone tumors. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2010;55(7):1370–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beneventi F, Locatelli E, Simonetta M, Cavagnoli C, Pampuri R, Bellingeri C, et al. Vaginal development and sexual functioning in young women after stem cell transplantation, chemotherapy, and/or radiotherapy for childhood hematological diseases. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(9):1157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zulpaite R, Bumbuliene Z. Reproductive health of female childhood cancer survivors. Ginekol Pol. 2018;89(5):280–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chemaitilly W, Li Z, Krasin MJ, Brooke RJ, Wilson CL, Green DM, et al. Premature Ovarian Insufficiency in Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Report From the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(7):2242–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chemaitilly W, Mertens AC, Mitby P, Whitton J, Stovall M, Yasui Y, et al. Acute ovarian failure in the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(5):1723–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilmoth MC, Spinelli A. Sexual implications of gynecologic cancer treatments. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2000;29(4):413–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hudson MM. Reproductive outcomes for survivors of childhood cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1171–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas-Teinturier C, El Fayech C, Oberlin O, Pacquement H, Haddy N, Labbe M, et al. Age at menopause and its influencing factors in a cohort of survivors of childhood cancer: earlier but rarely premature. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(2):488–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carter J, Goldfrank D, Schover LR. Simple strategies for vaginal health promotion in cancer survivors. The journal of sexual medicine. 2011;8(2):549–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frey Tirri B, Hausermann P, Bertz H, Greinix H, Lawitschka A, Schwarze CP, et al. Clinical guidelines for gynecologic care after hematopoietic SCT. Report from the international consensus project on clinical practice in chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50(1):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Children’s Oncology Group. Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers, Version 5.0. Monrovia, CA: Children’s Oncology Group; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barbera L, Zwaal C, Elterman D, McPherson K, Wolfman W, Katz A, et al. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(3):192–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carter J, Lacchetti C, Andersen BL, Barton DL, Bolte S, Damast S, et al. Interventions to Address Sexual Problems in People With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario Guideline. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(5):492–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eccles JS, Midgley C, Wigfield A, Buchanan CM, Reuman D, Flanagan C, et al. Development during adolescence. The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. Am Psychol. 1993;48(2):90–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robertson EG, Sansom-Daly UM, Wakefield CE, Ellis SJ, McGill BC, Doolan EL, et al. Sexual and Romantic Relationships: Experiences of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2016;5(3):286–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ford JS, Kawashima T, Whitton J, Leisenring W, Laverdiere C, Stovall M, et al. Psychosexual functioning among adult female survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(28):3126–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gavaghan MP, Roach JE. Ego identity development of adolescents with cancer. Journal of pediatric psychology. 1987;12(2):203–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evan EE, Kaufman M, Cook AB, Zeltzer LK. Sexual health and self-esteem in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer. 2006;107(7 Suppl):1672–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woodgate RL. A different way of being: adolescents’ experiences with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28(1):8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dieluweit U, Debatin KM, Grabow D, Kaatsch P, Peter R, Seitz DC, et al. Social outcomes of long-term survivors of adolescent cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19(12):1277–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gunnes MW, Lie RT, Bjorge T, Ghaderi S, Ruud E, Syse A, et al. Reproduction and marriage among male survivors of cancer in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood: a national cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(3):348–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Winter DL, Jenkinson HC, Hawkins MM, British Childhood Cancer Survivor S. Long-term population-based marriage rates among adult survivors of childhood cancer in Britain. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(4):846–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crom DB, Lensing SY, Rai SN, Snider MA, Cash DK, Hudson MM. Marriage, employment, and health insurance in adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1(3):237–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Font-Gonzalez A, Feijen EL, Sieswerda E, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Grootenhuis M, Maurice-Stam H, et al. Social outcomes in adult survivors of childhood cancer compared to the general population: linkage of a cohort with population registers. Psychooncology. 2016;25(8):933–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pivetta E, Maule MM, Pisani P, Zugna D, Haupt R, Jankovic M, et al. Marriage and parenthood among childhood cancer survivors: a report from the Italian AIEOP Off-Therapy Registry. Haematologica. 2011;96(5):744–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Green DM, Kawashima T, Stovall M, Leisenring W, Sklar CA, Mertens AC, et al. Fertility of female survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(16):2677–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kokkonen J, Vainionpaa L, Winqvist S, Lanning M. Physical and psychosocial outcome for young adults with treated malignancy. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;14(3):223–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lehmann V, Tuinman MA, Keim MC, Hagedoorn M, Gerhardt CA. Am I a 6 or a 10? Mate Value Among Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer and Healthy Peers. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2018;7(1):72–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lehmann V, Hagedoorn M, Gerhardt CA, Fults M, Olshefski RS, Sanderman R, et al. Body issues, sexual satisfaction, and relationship status satisfaction in long-term childhood cancer survivors and healthy controls. Psychooncology. 2016;25(2):210–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF. The course of life of survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2005;14(3):227–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Puukko LR, Hirvonen E, Aalberg V, Hovi L, Rautonen J, Siimes MA. Sexuality of young women surviving leukaemia. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76(3):197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Crawshaw MA, Sloper P. ‘Swimming against the tide’--the influence of fertility matters on the transition to adulthood or survivorship following adolescent cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2010;19(5):610–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lehmann V, Gronqvist H, Engvall G, Ander M, Tuinman MA, Hagedoorn M, et al. Negative and positive consequences of adolescent cancer 10 years after diagnosis: an interview-based longitudinal study in Sweden. Psychooncology. 2014;23(11):1229–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jervaeus A, Nilsson J, Eriksson LE, Lampic C, Widmark C, Wettergren L. Exploring childhood cancer survivors’ views about sex and sexual experiences -findings from online focus group discussions. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:165–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moules NJ, Estefan A, Laing CM, Schulte F, Guilcher GMT, Field JC, et al. “A Tribe Apart”: Sexuality and Cancer in Adolescence. Journal of pediatric oncology nursing : official journal of the Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses. 2017;34(4):295–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thompson AL, Long KA, Marsland AL. Impact of childhood cancer on emerging adult survivors’ romantic relationships: a qualitative account. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10 Suppl 1:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zebrack BJ, Casillas J, Nohr L, Adams H, Zeltzer LK. Fertility issues for young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13(10):689–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nilsson J, Jervaeus A, Lampic C, Eriksson LE, Widmark C, Armuand GM, et al. ‘Will I be able to have a baby?’ Results from online focus group discussions with childhood cancer survivors in Sweden. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(12):2704–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lehmann V, Ferrante AC, Winning AM, Gerhardt CA. The perceived impact of infertility on romantic relationships and singlehood among adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2019;28(3):622–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stinson JN, Jibb LA, Greenberg M, Barrera M, Luca S, White ME, et al. A Qualitative Study of the Impact of Cancer on Romantic Relationships, Sexual Relationships, and Fertility: Perspectives of Canadian Adolescents and Parents During and After Treatment. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2015;4(2):84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Koch SV, Kejs AM, Engholm G, Moller H, Johansen Christoffer., Schmiegelow K Marriage and Divorce Among Childhood Cancer Survivors. Journal of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 2011;33(7):500–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lehmann V, Tuinman MA, Keim MC, Winning AM, Olshefski RS, Bajwa RPS, et al. Psychosexual development and satisfaction in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: Neurotoxic treatment intensity as a risk indicator. Cancer. 2017;123(10):1869–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nightingale CL, Quinn GP, Shenkman EA, Curbow BA, Zebrack BJ, Krull KR, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life of Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Review of Qualitative Studies. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2011;1(3):124–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Frederick NN, Campbell K, Kenney LB, Moss K, Speckhart A, Bober SL. Barriers and facilitators to sexual and reproductive health communication between pediatric oncology clinicians and adolescent and young adult patients: The clinician perspective. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2018:e27087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Frederick NN, Revette A, Michaud A, Bober SL. A qualitative study of sexual and reproductive health communication with adolescent and young adult oncology patients. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2019;66(6):e27673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Kawkins J, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2013. MMWR Suppl. 2014;63(4):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Murphy D, Klosky JL, Termuhlen A, Sawczyn KK, Quinn GP. The need for reproductive and sexual health discussions with adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Contraception. 2013;88(2):215–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chasle S, How CC. The effect of cytotoxic chemotherapy on female fertility. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2003;7(2):91–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Marcell AV, Burstein GR, Committee On A. Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Services in the Pediatric Setting. Pediatrics. 2017;140(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Coccia PF, Pappo AS, Beaupin L, Borges VF, Borinstein SC, Chugh R, et al. Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, Version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(1):66–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vadaparampil ST, Kelvin J, Murphy D, Bowman M, Schovic I, Quinn GQ Fertility and Fertility Preservation: Scripts to Support Oncology Nurses in Discussions with Adolescent and Young Adult Patients. JCOM. 2016;22(2):73–8. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Griffin SJ, Kinmonth AL, Veltman MW, Gillard S, Grant J, Stewart M. Effect on health-related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trials. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(6):595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bober SL, Reese JB, Barbera L, Bradford A, Carpenter KM, Goldfarb S, et al. How to ask and what to do: a guide for clinical inquiry and intervention regarding female sexual health after cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2016;10(1):44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Taylor B, Davis S. Using the extended PLISSIT model to address sexual healthcare needs. Nurs Stand. 2006;21(11):35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sodergren SC, Husson O, Robinson J, Rohde GE, Tomaszewska IM, Vivat B, et al. Systematic review of the health-related quality of life issues facing adolescents and young adults with cancer. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2017;26(7):1659–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kemertzis MA, Ranjithakumaran H, Hand M, Peate M, Gillam L, McCarthy M, et al. Fertility Preservation Toolkit: A Clinician Resource to Assist Clinical Discussion and Decision Making in Pediatric and Adolescent Oncology. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2018;40(3):e133–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nahata L, Quinn GP, Tishelman A. A Call for Fertility and Sexual Function Counseling in Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2016;137(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Quinn GP, Block RG, Clayman ML, Kelvin J, Arvey SR, Lee JH, et al. If you did not document it, it did not happen: rates of documentation of discussion of infertility risk in adolescent and young adult oncology patients’ medical records. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]