Significance

Plants grow from their tips. The gametophore (shoot-like organ) tip of the moss Physcomitrium patens is a single cell that performs the same functions as those of multicellular flowering plants, producing the cells that make leaves and regenerating new stem cells to maintain the shoot tip. Several pathways, including CLAVATA and cytokinin hormonal signaling, regulate stem cell abundance in flowering plants and in mosses, although the mechanisms whereby these pathways regulate stem cell abundance and their conservation between these plant lineages is poorly understood. Using moss, we investigated how PpCLAVATA and cytokinin signaling interact. Overall, we found evidence that PpCLAVATA and cytokinin signaling interact similarly in moss and flowering plants, despite their distinct anatomies, life cycles, and evolutionary distance.

Keywords: plant biology, development, CLAVATA, cytokinin

Abstract

Plant shoots grow from stem cells within shoot apical meristems (SAMs), which produce lateral organs while maintaining the stem cell pool. In the model flowering plant Arabidopsis, the CLAVATA (CLV) pathway functions antagonistically with cytokinin signaling to control the size of the multicellular SAM via negative regulation of the stem cell organizer WUSCHEL (WUS). Although comprising just a single cell, the SAM of the model moss Physcomitrium patens (formerly Physcomitrella patens) performs equivalent functions during stem cell maintenance and organogenesis, despite the absence of WUS-mediated stem cell organization. Our previous work showed that the stem cell–delimiting function of the receptors CLAVATA1 (CLV1) and RECEPTOR-LIKE PROTEIN KINASE2 (RPK2) is conserved in the moss P. patens. Here, we use P. patens to assess whether CLV–cytokinin cross-talk is also an evolutionarily conserved feature of stem cell regulation. Application of cytokinin produces ectopic stem cell phenotypes similar to Ppclv1a, Ppclv1b, and Pprpk2 mutants. Surprisingly, cytokinin receptor mutants also form ectopic stem cells in the absence of cytokinin signaling. Through modeling, we identified regulatory network architectures that recapitulated the stem cell phenotypes of Ppclv1a, Ppclv1b, and Pprpk2 mutants, cytokinin application, cytokinin receptor mutations, and higher-order combinations of these perturbations. These models predict that PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 act through separate pathways wherein PpCLV1 represses cytokinin-mediated stem cell initiation, and PpRPK2 inhibits this process via a separate, cytokinin-independent pathway. Our analysis suggests that cross-talk between CLV1 and cytokinin signaling is an evolutionarily conserved feature of SAM homeostasis that preceded the role of WUS in stem cell organization.

Plant shoot morphology is generated by pluripotent stem cells called shoot apical meristems (SAMs) at growing shoot tips. SAMs perform two essential functions during morphogenesis: To pattern lateral organ initiation and to maintain the stem cell population by replacing cells differentiated during organogenesis. Decades of study in the model flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana have revealed a key role for a negative feedback loop in SAM homeostasis (1). Stem cells at the apex of the meristem secrete a slew of CLAVATA3/EMBRYO SURROUNDING REGION (CLE) peptides, including CLV3 (2, 3). CLV3 acts through a suite of leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinases (LRR-RLKs), including CLAVATA1 (CLV1) and RECEPTOR-LIKE PROTEIN KINASE2 (RPK2) to repress the expression of the stem cell organizing gene WUSCHEL (WUS), thereby limiting the size of the stem cell pool (1, 4–8). WUS promotes expression of CLV3, completing the negative feedback loop (9, 10). In Arabidopsis, wus mutants fail to maintain a SAM (11, 12). In contrast, clv3, clv1, or rpk2 loss-of-function mutants fail to down-regulate WUS expression and produce too many stem cells, leading to an enlarged and fasciated SAM, increased organ numbers, and stem swelling (1, 4).

Unlike the multicellular SAM of flowering plants, the moss SAM comprises a single tetrahedral stem cell (13). Despite this anatomical difference, the moss apical cell accomplishes the same two essential SAM functions: Lateral organ patterning and self-maintenance. In so doing, the moss SAM divides asymmetrically to form a phyllid (leaf-like organ) progenitor cell and a new apical stem cell. The apical division plane rotates to produce phyllids in a spiral pattern around the haploid gametophore (haploid shoot). The transcriptome of the moss SAM shares a high degree of overlap with flowering plant SAMs, suggesting possible deep homology underlying SAM function despite the fact that the moss haploid SAM and the diploid SAM of flowering plants reside in nonhomologous shoots (14).

In contrast to flowering plants, the moss Physcomitrium patens (previously known as Physcomitrella patens) encodes only three orthologs of stem cell–regulating LRR-RLKs: PpCLV1a, PpCLV1b, and PpRPK2. This relative simplicity makes P. patens an appealing model for understanding the role of these receptors in stem cell specification (15). We previously characterized the function of CLV1 and RPK2 orthologs in P. patens and found that these genes performed similar developmental functions in flowering plants and P. patens (16), including regulation of SAM homeostasis. Ppclv1a Ppclv1b double mutants and Pprpk2 single mutants produce ectopic stem cells, suggesting that the canonical roles of CLV1 and RPK2 to reduce stem cell number are conserved. PpCLV1a and PpCLV1b function redundantly (16), so we refer to their combined activity as PpCLV1. Interestingly, whereas the Arabidopsis clv1 and rpk2 stem cell phenotypes are attributed to overaccumulation of WUS, P. patens lacks this WUS function (17). The P. patens genome encodes three WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX (WOX) genes, all of which lack domains critical for the stem cell modulatory function of WUS (17–19). P. patens wox mutants exhibit defective tip growth in regenerating protonemal filaments; however, gametophore development is normal (20). Together, these data suggest that P. patens WOX genes do not function during SAM homeostasis (20). This raises the question: In the absence of WOX-mediated stem cell maintenance, how do PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 inhibit stem cell specification in P patens?

The hormone cytokinin promotes SAM formation in both Arabidopsis and P. patens (21). Several lines of evidence suggest an antagonistic relationship between CLV1 and RPK2, and cytokinin (16, 21). In P. patens gametophores, cytokinin promotes the formation of new SAMs (22), while loss of PpCLV1 or PpRPK2 signaling causes ectopic stem cell formation (16). Intriguingly, in Arabidopsis, cytokinin promotes SAM formation via induction of WUS expression (23, 24). This again begs the question of how cytokinin promotes SAM formation in P. patens, despite the absence of WOX function during stem cell organization. In this study, we ask whether there is cross-talk between PpCLV1, PpRPK2, and cytokinin signaling during stem cell specification in P. patens.

Mathematical models representing competing hypotheses were fit to the empirical data on SAM homeostasis in wild-type versus Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and rpk2 mutant gametophores, with and without cytokinin treatment, and when cytokinin signaling is lost. Maximum support was found for a model where PpCLV1 signaling is upstream of cytokinin-mediated stem cell induction, and PpRPK2 signaling acts via a separate pathway. Overall, our data support a network in which PpCLV1 and cytokinin signaling converge on the regulation of P. patens SAM maintenance. This network is distinct from the canonical angiosperm network in that it lacks a role for a WOX gene as the hub linking cytokinin and CLV1 pathways. Thus our work suggests cross-talk between CLV1 receptors and cytokinin signaling is an evolutionarily conserved feature of SAM homeostasis that preceded the role of WUS in stem cell organization.

Results

PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 Function through Distinct Pathways.

Our previous research revealed a conserved role for the P. patens LRR-RLKs PpCLV1A, PpCLV1B, and PpRPK2 in inhibiting stem cell identity in gametophores (16). Loss-of-function mutations in the two PpCLV11a and PpCLV1b paralogs or in PpRPK2 resulted in gametophores with ectopic apical cells along the lengths of swollen stems (16). In order to determine whether PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 function in the same pathway to regulate stem cell formation, we used CRISPR-Cas9–mediated mutagenesis to target PpRPK2 in a Ppclv1a Ppclv1b double mutant background and generated three independent, triple mutant lines with the same phenotypes (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). We examined wild-type, Ppclv1a Ppclv1b, Pprpk2, and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 mutant gametophores across three developmental timepoints ranging from less than 1 wk old to approximately 4 wk old (Fig. 1).

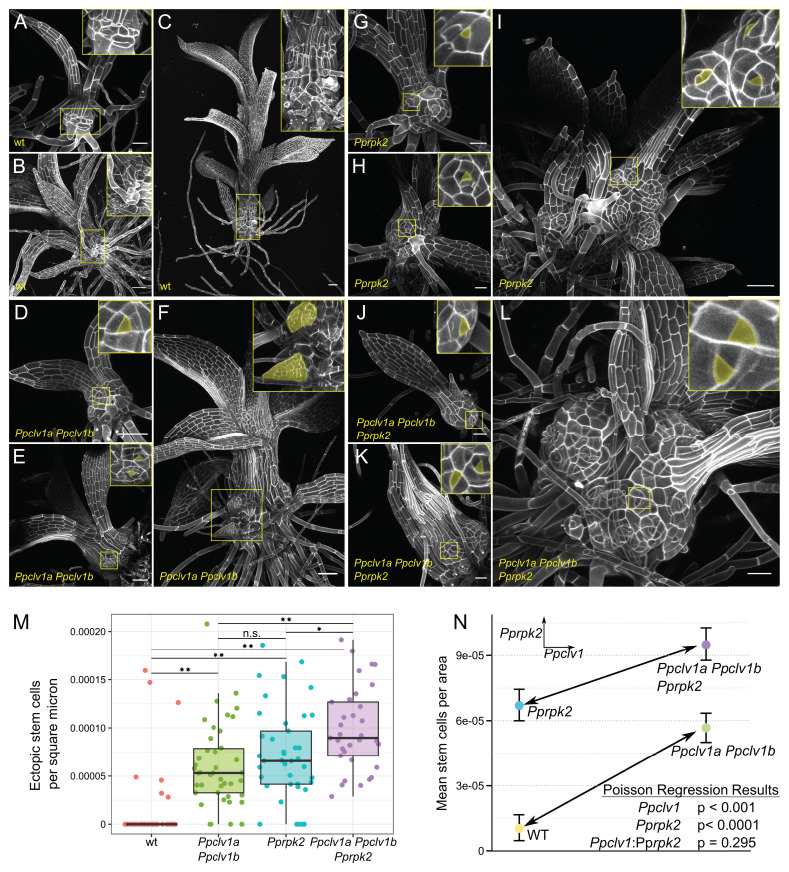

Fig. 1.

Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 mutant phenotypes are additive. Gametophore development at approximately 1 wk (A, D, G, and J), 2 wk (B, E, H, and K), and 3 to 4 wk (C, F, I, and L) in wild type (WT) (A–C), Ppclv1a Ppclv1b (D–F), Pprpk2 (G–I), and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 (J–L). Insets show cells at the base, with ectopic stem cells and outgrowths initiating from stem cells (pseudocolored yellow) in the mutants. (M) Ectopic stem cells per square micrometer of stem tissue from 30 to 40 shoots of each genotype. n.s., not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; two-sided t test with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. (N) An interaction plot showing the effects of Ppclv1 (Left to Right, arrow) and Pprpk2 (Top to Bottom) mutations on ectopic stem cell per square micrometer. The similar slopes of the two lines demonstrate that the effect of the two Ppclv1 mutations is the same in wild-type and Pprpk2 genetic backgrounds. Results for a Poisson regression testing for significant effects from Ppclv1a Ppclv1b mutants, Pprpk2 mutants, and an interaction between the two are given. (Scale bar, 50 µm.)

Wild-type gametophores were mostly covered with phyllids, leaving little exposed stem tissue (Fig. 1 A–C). In contrast, the stems of Ppclv1a Ppclv1b, Pprpk2, and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 mutants were swollen from the earliest stages of development (Fig. 1 D, G, and J). Ectopic apical cells were present on the rounded stems of these mutants at all stages of development. Apical cells were identified by the characteristic triangular shape of their apical surface: The top of the tetrahedron. At later stages, Ppclv1a Ppclv1b, Pprpk2, and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 mutant gametophores produced ectopic phyllids, indicating that the ectopic apical cells observed at earlier stages were indeed functional SAMs (Fig. 1F).

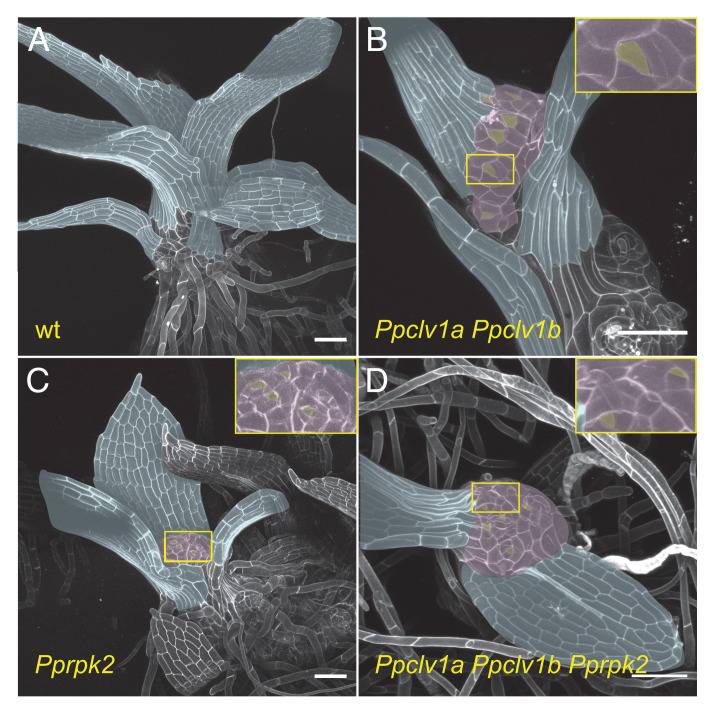

All mutant gametophores stopped elongating earlier than the wild type, often terminating in a swollen apex with abundant apical cells (Fig. 2). After terminating longitudinal growth, Ppclv1a Ppclv1b, Pprpk2, and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 mutant gametophores continued to swell and initiate new growth axes from ectopic stem cells along the length of the stem (Figs. 1 F, I, and L and 2). The swelling of gametophore tips in a mass of stem cells in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 mutant stems was reminiscent of stem cell overproliferation and SAM disorganization seen in Arabidopsis clv and rpk2 mutants (4, 25), again highlighting the conserved function of this pathway in SAM homeostasis (16).

Fig. 2.

Ppclv1a Ppclv1b, Pprpk2, and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 gametophores terminate in a mass of stem cells. Approximately 3-wk-old wild type (A), Ppclv1a Ppclv1b (B), Pprpk2 (C), and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 mutant (D) gametophores. Bare apices (pseudocolored purple) replete with stem cells (pseudocolored yellow) are visible in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b, Pprpk2, and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 mutants, while the single apical cell at the apex of wild-type shoots is well covered by phyllids (pseudocolored blue). (Scale bars, 100 µm.)

However, it was not clear how PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 signaling interact to inhibit ectopic stem cell formation. To determine whether PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 function in the same linear pathway, we quantified the number of visible ectopic stem cells by confocal microscopy on 30 to 40 gametophores of each genotype. Gametophores initiate continuously from a P. patens tuft, making the age of the tuft a poor indicator of gametophore age. To control for variation in gametophore age and any increase in stem cell count due to increased mutant stem size, ectopic stem cell number was normalized to the size of the stem (Fig. 1M and nonnormalized data in SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Ectopic stem cells were observed on almost all Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 gametophores, in contrast to wild type.

If PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 act in a linear genetic pathway, epistasis is predicted in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 triple mutants. In contrast, if PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 have redundant functions but act in distinct complexes, a synergistic increase in stem cell initiation is predicted in triple mutants. Finally, if PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 act nonredundantly, i.e., in distinct signaling pathways, additive effects on stem cell initiation phenotypes are expected. The number of ectopic stem cells per area was significantly higher in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 triple mutants than either Ppclv1a Ppclv1b double mutants (P < 0.001) or Pprpk2 single mutants (P = 0.01) (Fig. 1M). An interaction plot revealed that the effect of mutating PpCLV1a and PpCLV1b is similar in wild type or Pprpk2 mutant backgrounds (the slope of the lower and upper lines, respectively); thus, the effects of the Ppclv1a/Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 mutations appear additive (Fig. 1N). A Poisson regression, which is suited for low count data (such as number of ectopic ACs) and included stem area as an offset to control for stem size, was used to assess the statistical significance (P value) and impact (coefficient) of mutating PpCLV1a/PpCLV1b and PpRPK2 and the interaction between these two (Fig. 1N). The regression revealed significant effects for loss of PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 function (P < 0.0001 for each and coefficients 0.5054 and 0.6358 for Ppclv1a/Ppclv1b and Pprpk2, respectively; see SI Appendix, Dynamical Model Methods for details), but no significant interaction between them (P = 0.29, coefficient −0.1774). In summary, the genetic data suggest that PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 do not function in the same linear pathway during regulation of stem cell abundance in the gametophore.

PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 Signaling Interactions with Cytokinin Signaling.

Exogenous cytokinin application induces swelling and stem cell formation along wild-type gametophores (22), similar to phenotypes observed in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 mutants (Figs. 3 A–C and 1). We hypothesized two possible pathways to explain the convergence of these phenotypes. First, PpCLV1 and/or PpRPK2 could function by inhibiting cytokinin-mediated stem cell specification, i.e., PpCLV1/PpRPK2 function is upstream of cytokinin response. Alternatively, cytokinin signaling might be upstream and inhibit PpCLV1/PpRPK2 function, such that cytokinin derepresses stem cell formation. To better understand how PpCLV1 or PpRPK2 signaling interacts with cytokinin signaling, we characterized the response of Ppclv1a Ppclv1b, Pprpk2, and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 mutants to exogenous treatment (10 nM and 100 nM) of the synthetic cytokinin 6-benzylamino purine (BAP). If PpCLV1 or PpRPK2 function upstream or independently of cytokinin signaling, BAP treatment is predicted to induce stem cell formation in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 mutants. On the other hand, if cytokinin is an upstream inhibitor of PpCLV1 and/or PpRPK2 function, BAP treatment is expected to have no effect on the Ppclv1a Ppclv1b or Pprpk2 mutant phenotypes.

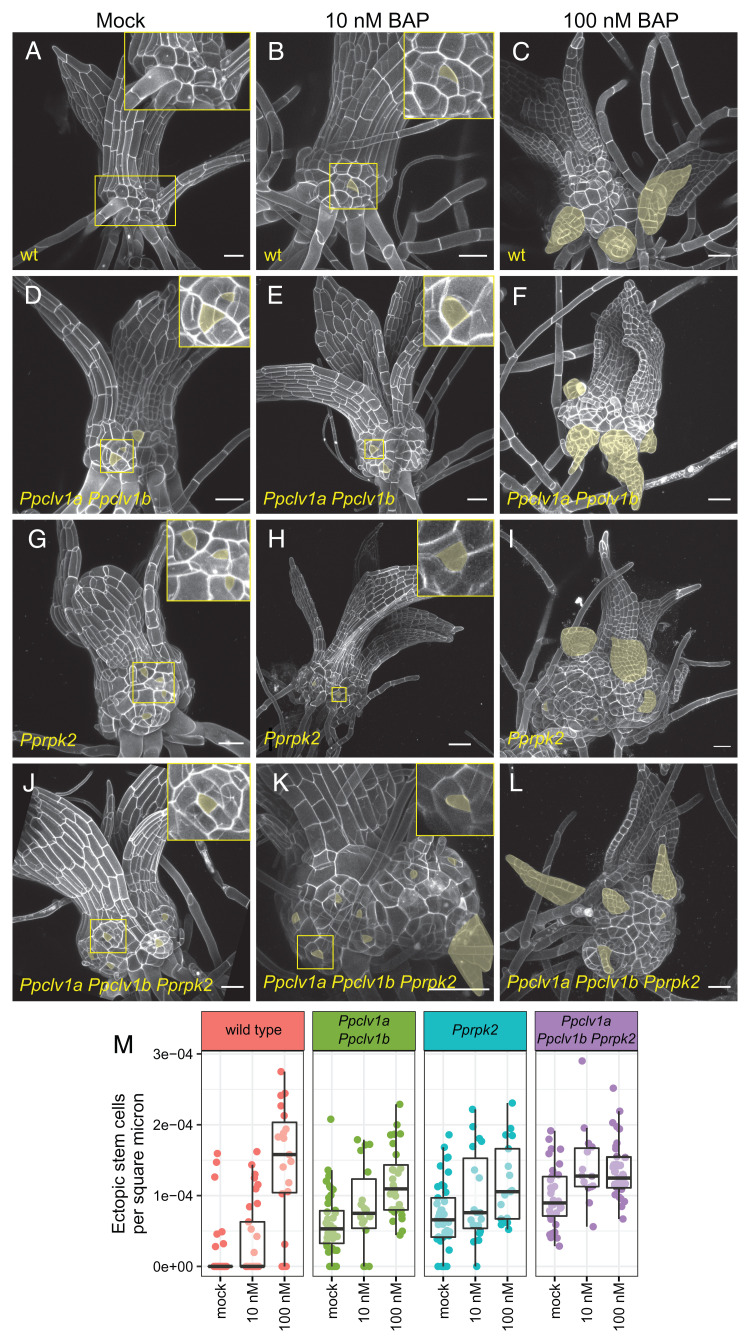

Fig. 3.

Cytokinin induces phenotypes similar to Ppclv1a Ppclv1b/Pprpk2 and increases apical cell formation in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b/Pprpk2 mutants. The 2- to 3-wk-old gametophores grown on mock media (0 nM, A, D, G, and J) or media supplemented with low (10 nM, B, E, H, and K) or high (100 nM, C, F, I, and L) BAP. (M) Quantification of ectopic stem cells per area of exposed stem. Note that M includes data from Fig. 1M for clarity. Ectopic stem cells and ectopic phyllids (indicative of underlying stem cells) are pseudocolored yellow. (Scale bars, 50 µm.) See Results for statistics from Poisson regression.

We quantified the number of ectopic stem cells in each genotype grown on 10 nM and 100 nM cytokinin, normalized to stem area as described above. Wild-type gametophores grown on 10 nM BAP displayed slight swelling and developed ectopic tetrahedral apical cells reminiscent of those seen in Ppclv1a PPclv1b and Pprpk2 mutants (Fig. 3 A and B). A higher concentration of cytokinin induced swollen stems and numerous outgrowths derived from ectopic stem cells in wild-type plants (Fig. 3 C and M). In comparison, 10 nM BAP had mild effects on stem swelling and ectopic apical cell formation in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 mutant gametophores (Fig. 3 E, H, and M), although treatment with 100 nM BAP induced numerous ectopic apical cells and a high degree of stem swelling (Fig. 3 F, I, and M). Interestingly, growing Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 mutants on 10 nM or 100 nM BAP resulted in a similar amount of stem cells per area (Fig. 3 K, L, and M and nonnormalized data in SI Appendix, Fig. S3), suggesting ectopic stem cell formation was already saturated. Overall, stem cell formation increased in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b, Pprpk2, and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 mutants in response to cytokinin. These data support a role PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 upstream or independent of cytokinin response.

Interestingly, while cytokinin induced stem cell formation in all genotypes, this effect appeared weaker in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 mutants than in wild type (Fig. 3M). To statistically assess how PpCLV1, PpRPK2, and cytokinin interact to control stem cell specification, we analyzed our full dataset, comprising each genotype with and without BAP treatment, using a Poisson regression. Notably, there remained a significant increase in stem cells caused by loss of PpCLV1 or PpRPK2 function, as well as cytokinin treatment (P value and Poisson coefficient for clv1: P = 0.0001, coefficient = 0.64; rpk2: P < 0.0001, coefficient = 0.96; cytokinin treatment: P < 0.0001, coefficient = 0.0133). In agreement with our conclusion from Fig. 1, cytokinin treatment also revealed no significant statistical interactions between the effects of Ppclv1a/Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 mutations (P = 0.240), indicating that these mutant phenotypes are indeed additive. Interestingly, each mutant showed a slight but statistically significant reduced induction of stem cells in response to exogenous cytokinin compared to wild type (Fig. 2I, Ppclv1a Ppclv1b:cytokinin P = 0.033, coefficient = −0.003; Pprpk2:cytokinin P < 0.0001; coefficient = −0.009).

In summary, the phenotypes of Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 were additive across a range of exogenous cytokinin concentrations, suggesting that PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 act via distinct pathways regulating stem cell specification. Cytokinin increases stem cell initiation in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 mutants, supporting a role for PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 upstream or independent of cytokinin signaling. However, loss of PpCLV1 or PpRPK2 function also slightly diminished the effect of exogenous cytokinin on stem cell production. These data suggest that cytokinin response could already be high in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 mutants such that exogenous cytokinin treatments represented a smaller relative increase in cytokinin signaling in the mutants than in wild type. Such a scenario would occur if PpCLV1 and/or PpRPK2 functioned by inhibiting cytokinin-mediated stem cell specification.

Mathematical Modeling Supports Action by PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 through Distinct Pathways.

To test possible regulatory network topologies that integrate PpCLV1, PpRPK2, and cytokinin signaling to control stem cell identity in gametophores, we evaluated a range of hypothetical gene regulatory network models (e.g., Fig. 4A, see model code in Datasets S1 and S2). Given that the data supported PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 signaling through separate pathways, we coded two variables, “x” and “y,” to represent two hypothetical pathways each capable of promoting stem cell formation. It is important to note that x and y do not represent any specific genes, but rather are simplified representations of unknown but postulated signaling outputs. As cytokinin induces stem cell formation, we specified that pathway x denotes cytokinin response, while pathway y represents cytokinin-independent stem cell specification pathways.

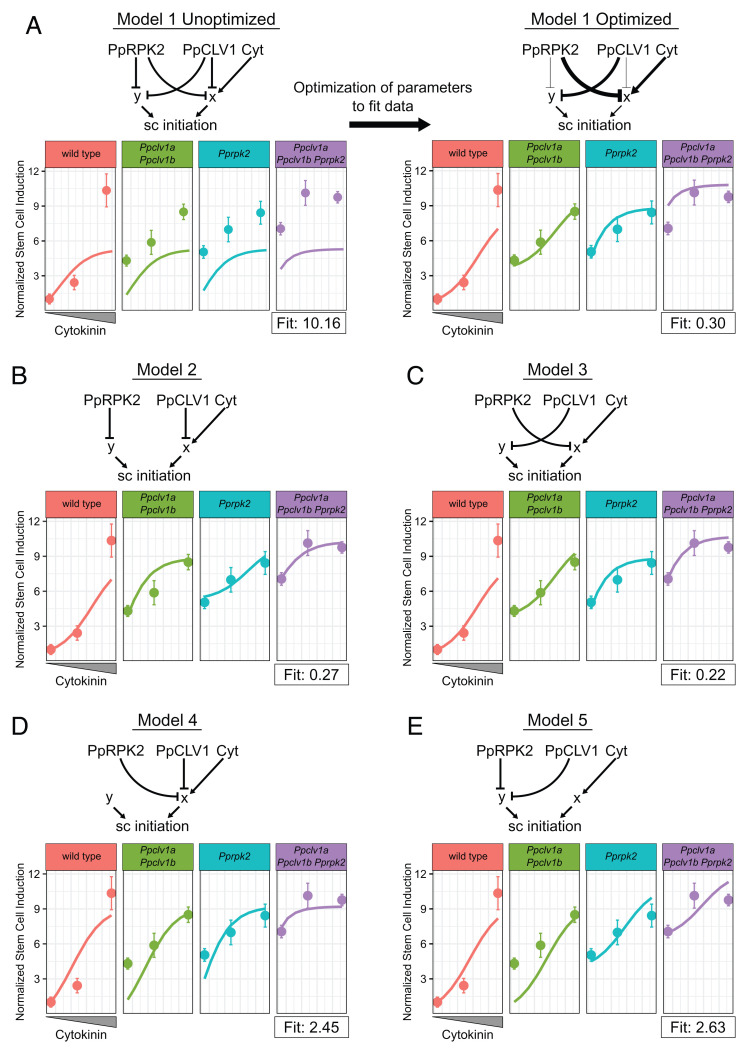

Fig. 4.

Dynamical model simulations of stem cell production by Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 mutants over a range of cytokinin concentrations. Basic network depictions and simulation results of mathematical models formalizing five different hypotheses: Model 1 PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 are partially redundant (A); model 2 PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 are independent with PpCLV1 upstream of cytokinin response (B); model 3 PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 are independent with PpRPK2 upstream of cytokinin response (C); model 4 PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 are redundant and upstream of cytokinin response (D); and model 5 PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 are redundant and upstream of a cytokinin-independent pathway (E). On plots, solid lines represent simulated data over a range of cytokinin concentrations. Dots with error bars represent the mean empirical stem cells per square micrometer data and SEs. From Left to Right, dots represent values from P. patens grown on mock, 10 nM BAP, and 100 nM BAP. In the model on the Right side of A, the thickness of interaction edges is proportional to the corresponding optimized parameters. Note the empirical data points are based on the data in Fig. 3M.

In the first model, PpRPK2 and PpCLV1 are capable of inhibiting stem cell initiation through both cytokinin-dependent and independent pathways, i.e., through both x and y (Fig. 4A). This model has the greatest flexibility and represents a scenario where PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 have overlapping but nonidentical contributions to both the x and y pathways. The second and third models simulate the cases where PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 act completely independently (Fig. 4 B and C). In model 2, PpCLV1 inhibits cytokinin-mediated stem cell induction (x) and PpRPK2 inhibits cytokinin-independent stem cell induction (y), while the roles for PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 are reversed in model 3. As an additional test of whether PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 might be redundant, we included models 4 and 5 wherein each inhibits x (Fig. 4D) or y (Fig. 4E) exclusively, although with potentially different strengths. Thus, these five models represent five competing hypotheses where PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 are partially redundant, completely independent, or completely redundant, and where each acts upstream of a cytokinin-dependent or a cytokinin-independent pathway promoting stem cell specification.

We next compared the extent to which each model could recapitulate the patterns of ectopic stem cell production seen in the empirical data. The behavior and output of a model depends on the parameters selected. Thus, we sought to optimize the parameters in each network to reach the best fit possible to the empirical data. To find the optimal parameters, we coded a random optimizer function (SI Appendix, Dynamical Model Methods). Given a network and a set of starting parameters, we used the model to simulate each relevant mutant genotype (wild type, Ppclv1a Ppclv1b, Pprpk2, and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2) at each level of cytokinin treatment (0 nM BAP, 10 nM BAP, and 100 nM BAP). For each model and set of parameters we thus simulated 12 scenarios that we compared with the corresponding mean values from the empirical data. We generated a single fit score that was proportional to the difference between the model and the empirical data (smaller scores indicate a closer fit). Larger differences between simulated and empirical data points were penalized more heavily than smaller ones (SI Appendix, Dynamical Model Methods). Once a score was generated, each parameter was randomly mutated (adjusted up or down) and a new fit score was calculated and compared to the previous one. If the new fit score was better (lower), the new parameters for that run were adopted as the starting point for the next round of optimization. If the fit score proved worse, the previous parameters were kept as the starting point for the next round of optimization. We ran the optimizer for 300 iterations, allowing the fit score to plateau at a minimum value for each model (SI Appendix, Dynamical Model Methods).

Using this iterative optimizer, we tested our five competing models on how PpCLV1, PpRPK2, and cytokinin regulate stem cell identity. For model 1, the optimizer selected parameters that separated the roles for PpCLV1 and PpRPK2, i.e., the optimizer minimized their redundant activity and emphasized their independent activity (Fig. 4A). Specifically, the optimizer strengthened the regulatory connection between PpRPK2 and cytokinin signaling while weakening the interaction between PpRPK2 and cytokinin-independent stem cell induction, and the optimizer did the opposite for PpCLV1 (Fig. 4A). Thus, the optimized model 1 was similar to model 3 (Fig. 4C). Optimized model 1 reasonably replicated the empirical data with a fit score of 0.3, but notably overestimated the number of ectopic stem cells in the triple mutant grown in the absence of exogenous cytokinin (Fig. 3A). Models 2 and 3 produced similar fits to model 1 after optimization with fit scores of 0.27 and 0.22, respectively (Fig. 4 B and C). Notably, model 2 and model 3 successfully simulated the level of stem cell initiation in triple mutants without exogenous cytokinin. These two models differed from one another predominately in the cytokinin response curves of Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 mutants (Fig. 3 B and C), but neither simulation was far from the empirical data. Finally, model 4 (fit score = 2.45) and model 5 (fit score = 2.63) produced very poor fits to the data (Fig. 2 D and E), highlighting the unlikelihood of redundancy between PpCLV1 and PpRPK2. Altogether, the five models support PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 acting through separate pathways. However, the models do not confidently distinguish whether PpCLV1 or PpRPK2 functions upstream of the cytokinin response, as either scenario could reproduce the empirical data.

Given that models 2 and 3 best reproduce the empirical data, we used them to predict how stem cell initiation would be affected by the absence of cytokinin signaling (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Each model predicted that, if devoid of cytokinin signaling, each genotype would produce even fewer apical cells. This is consistent with data showing reduced branch stem cell initiation after increasing cytokinin degradation (22). Informatively, the model predicted that if PpCLV1 functions upstream of cytokinin, blocking cytokinin signaling would suppress the ectopic stem cell phenotype in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b double mutants. On the other hand, if PpRPK2 functions upstream of cytokinin, blocking cytokinin signaling would suppress the ectopic stem cell formation in Pprpk2 mutants (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Loss of Cytokinin Signaling Reveals a Complex Network Controlling Stem Cell Specification.

Three PpCYTOKININ HISTIDINE KINASE (PpCHK) genes in P. patens encode the known cytokinin receptors, and chk1 chk2 chk3 triple mutants lack the ability to perceive cytokinin (26, 27). Using CRISPR-Cas9 to mutate PpCLV1a, PpCLV1b, and PpRPK2 in the Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 background, we generated and confirmed four independent lines of Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 quintuple mutants, two independent Pprpk2 Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 quadruple mutants, and two Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 sextuple mutants (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). These higher order mutant filaments and gametophores were insensitive to growth on BAP, supporting a complete loss of cytokinin perception (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Our models predicted that if ectopic stem cell formation in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b mutants resulted from increased cytokinin-mediated stem cell initiation, ectopic stem cell formation would be suppressed in the higher order Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 quintuple mutants. Alternatively, if PpRPK2 signaling were upstream of the cytokinin response (x), the Pprpk2 ectopic stem cell phenotype would be suppressed in Pprpk2 Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 quadruple mutants. To test our predictions of how loss of cytokinin signaling impacts stem cell specification, we examined gametophores from multiple independent lines of Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 and higher order mutants at cellular resolution and quantified stem cell abundance (Fig. 5 A–E).

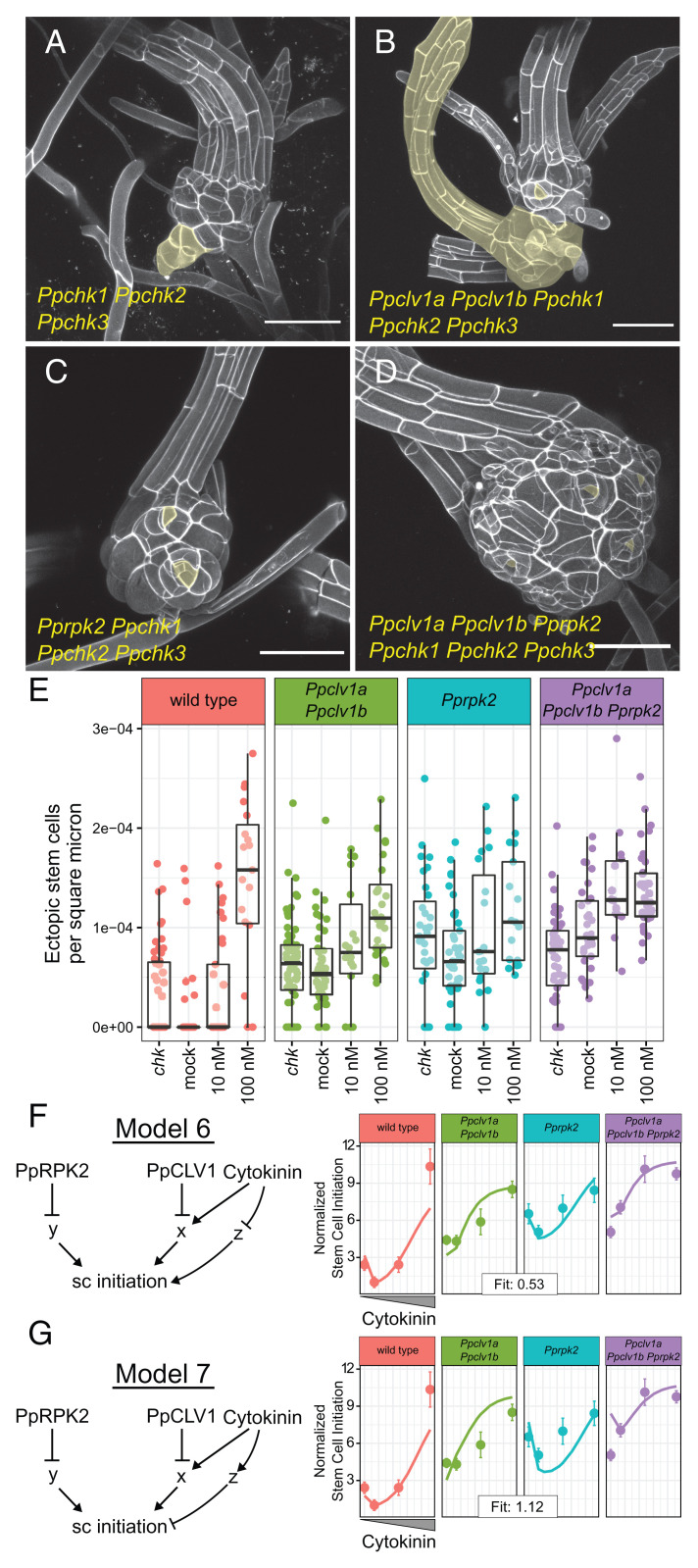

Fig. 5.

Ppchk mutants produce ectopic stem cells and have complex interactions with Ppclv1 and Pprpk2 mutants. Gametophores from 5-wk-old colonies of Ppchk (A), Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 quintuple mutants (B), Pprpk2 Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 quadruple mutants (C), and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 sextuple mutants (D). Ectopic stem cells or derived outgrowths are highlighted in yellow. Quantification of ectopic stem cells per square micrometer of visible stem (E), including data from Fig. 3M. The range of phenotypes quantified are illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S7. Model 6 posits that cytokinin inhibits an inducer of stem cell identity (F). In model 7, cytokinin promotes an inhibitor of stem cell specification (G). In F and G, solid lines represent simulated data, while dots represent mean stem cells per area from the empirical data. Error bars show the SE. See Results for statistics from Poisson regression.

Cytokinin induces the formation of gametophores (22) and promotes cell proliferation in phyllids (Fig. 3 A–C) (28). Consistent with these functions, the Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 triple mutants develop gametophores 2 wk later than wild type (27), and once formed, Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 gametophores produce slender phyllids with elongated cells in fewer cell files (Fig. 5 A–D and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Surprisingly, confocal imaging of Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 mutant gametophores revealed the formation of ectopic growth axes, indicating increased stem cell production. Higher order Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 quintuple, Pprpk2 Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 quadruple, and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 sextuple mutants produced swollen stems with variable degrees of ectopic apical cells (Fig. 5 A–E, range of phenotypes illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S7, and nonnormalized data in SI Appendix, Fig. S8). We statistically analyzed the full dataset including stem cell quantification from all mutants and genotypes generated thus far using a Poisson regression. We found that loss of PpCHK function was significantly associated with increased stem cell abundance (P = 0.013). Although neither loss of PpCLV1 nor PpRPK2 displayed statistically significant interactions with PpCHK loss of function, a negative interaction between Ppclv1 and Ppchk mutations tended toward significance (clv1:chk P = 0.07; rpk2:chk P = 0.11), weakly supporting a role for PpCLV1 upstream of cytokinin. Overall, loss of cytokinin signaling causes ectopic stem cell formation and does not suppress stem cell initiation, contrary to our predictions. Thus, the Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 and higher order mutant phenotypes suggest that important features were missing from our dynamical models of stem cell homeostasis.

Incoherent Feedforward Control of Stem Cell Induction Can Explain chk Phenotypes.

We hypothesized that the ectopic stem cell phenotype of Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 triple mutants could be explained by an incoherent feedforward control: In addition to its primary function of promoting stem cell formation, cytokinin either 1) represses a pathway that induces stem cell specification or 2) promotes a pathway that represses stem cell specification. To test the plausibility of these hypotheses, we formalized each as a dynamical model (models 6 and 7, respectively), each with versions based on models 2 and 3. For each model, we introduced a factor called z, which is independent of PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 signaling. In model 6, z induced stem cell initiation and was inhibited by cytokinin (Fig. 5F), while in model 7, z inhibited stem cell initiation and was itself induced by cytokinin (Fig. 5G). Each model represents an alternative form of the hypothesis that cytokinin promotes stem cell induction, but also provides additional input to temper the sensitivity to stem cell specification cues. We predicted that in the complete absence of cytokinin signaling, the loss of this buffering capacity would render stem cell specification hypersensitive to inputs from other pathways, such as those represented by y in the model.

Optimizing each model to the full dataset provides a test of how well each model can capture key trends in the empirical data. Because we previously found that either PpCLV1 or PpRPK2 acted upstream of cytokinin signaling (x), we simulated both scenarios for each model (Fig. 5 F and G and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Model 6 successfully reproduced the trends in the empirical data and fit better if PpCLV1 was upstream of cytokinin response (fit score = 0.53, Fig. 5F) rather than PpRPK2 (fit score = 0.74, SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Model 7—in which cytokinin induced an independent stem cell inhibitory pathway—fit the data poorly in all cases, as it overestimated the number of ectopic stem cells forming in higher order mutants (model 7 fit scores: 1.12 and 1.36 with PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 upstream of cytokinin, respectively) (Fig. 5G and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). In comparison, when model 2 and model 3 were fit to this dataset they produced fit scores of 1.85 and 1.59, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S10), demonstrating the impact of including z in the model. Overall, a role for cytokinin in buffering stem cell initiation can explain the ectopic stem cell formation in Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 mutants and higher order Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 and Pprpk2 Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 mutants.

To test our model that PpCLV1 regulates cytokinin signaling, we used quantitative PCR to measure the expression level of cytokinin-responsive genes as a proxy for broader cytokinin signaling. However, to do so required the validation of bona fide transcriptional targets of cytokinin signaling in P. patens. Looking through an expressed sequence tag dataset measuring transcriptional response to cytokinin in P. patens, we found that several PpCYTOKININ OXIDASE (PpCKX) genes were up-regulated in response to cytokinin (29). Testing the expression of five different PpCKX revealed that all were up-regulated when colonies were grown on cytokinin, although PpCKX6 was less sensitive than the others (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A). Thus, the expression levels of PpCKX genes might be suitable indicators of transcriptional responses to cytokinin in P. patens (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A).

Our best models posit that PpCLV1 represses responses downstream of cytokinin. We thus predicted that, since the expression level of PpCKX genes might reflect the level of cytokinin signaling, PpCKX expression would be increased in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b mutants but unchanged in Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 mutants. Indeed, this pattern was true for the expression of PpCKX1, but not for any other CKX genes (SI Appendix, Fig. S11B). While these data provide qualified support for our model, they also indicate the complexity in cytokinin signaling.

One mechanism through which cytokinin might buffer stem cell initiation is by promoting the expression of PpCLV1a PpCLV1b or PpRPK2 genes. qPCR on gametophores grown on mock media revealed variable expression for PpCLV1a, PpCLV1b, or PpRPK2 genes, in agreement with previous promoter GUS fusions (16). Additionally, no significant increase in PpCLV1a, PpCLV1b, or PpRPK2 expression was seen for gametophores grown on 50 nM and 100 nM BAP (SI Appendix, Fig. S11C). Therefore, in accordance with our model, it is unlikely that cytokinin buffers stem cell initiation through the transcriptional regulation of PpCLV1 or PpRPK2.

Discussion

Our work demonstrated similar functions for CLV1 and RPK2 orthologs as regulators of stem cell abundance in the moss P. patens as have been previously reported in Arabidopsis. We used a combination of higher-order genetics, hormone treatment, and mathematical modeling to demonstrate that, as in flowering plants, stem cell identity in P. patens gametophores is regulated by interaction between CLV and cytokinin signaling.

PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 Signal through Distinct Pathways.

In Arabidopsis, the roles of CLV1 and RPK2 signaling are similar in multiple contexts, including stem cell maintenance, carpel development, and anther development (4, 21, 30, 31). However, depending on the context, there is conflicting evidence as to whether CLV1 and its paralogs function in separate or overlapping pathways with RPK2, including evidence for protein–protein interactions between these receptors (4, 30–33). The suite of CLV1 and RPK2-like receptors in P. patens is reduced compared to Arabidopsis, making it a powerful system for studying their genetic interactions (16). Ppclv1a Ppclv1b and Pprpk2 have distinct filament phenotypes, where Pprpk2 colonies spread faster than wild type or Ppclv1a Ppclv1b colonies (34). This phenotypic distinction could arise from differences in expression patterns, rather than distinct molecular functions. However, PpCLV1a, PpCLV1b, and PpRPK2 are coexpressed in gametophores, where their loss of function renders similar mutant phenotypes (16). Here we show that in P. patens, PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 act additively in gametophores, in distinct pathways, to regulate stem cell specification. In combination with data in Arabidopsis showing additive effects of clv1 and rpk2 mutants in carpel development (4) and the control of gene expression in the SAM (33), these data support a model where in general, CLV1 and RPK2 are not required to act together as a signaling module in plants.

Cytokinin CLV Cross-Talk Has a Similar Function in P. patens and Arabidopsis.

In Arabidopsis, CLV1, RPK2, and cytokinin regulate stem cell identity as part of a network centered around the master regulator gene WUSCHEL. In P. patens, PpWOX genes do not regulate SAM homeostasis (20). Both exogenous cytokinin and decreased PpCLV1/PpRPK2 function cause similar gametophore phenotypes, including stem swelling and ectopic stem cell formation. This overlap in phenotypes led us to ask whether PpCLV1/PpRPK2 and cytokinin interact to regulate stem cell identity in P. patens. We tested the response of Ppclv1a Ppclv1b, Pprpk2, and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 mutants to cytokinin and loss of cytokinin signaling (Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3) and used mathematical modeling to determine which of seven different hypothetical networks describing PpCLV1, PpRPK2, and cytokinin function could best recapitulate empirical stem cell specification data. Our data and modeling suggest that either PpCLV1 or PpRPK2 acts upstream of cytokinin-mediated stem cell induction, with greater support for PpCLV1 performing this role. Our models represent overarching signaling networks, where x and y represent whole signaling cascades, not single genes. Thus, a number of specific molecular networks could fall within the frameworks of the model. Interestingly, this cytokinin-dependent pathway (x in the model, Figs. 4 and 5) occupies the same position as WUS in models describing stem cell specification in the Arabidopsis SAM (1, 35). This suggests that in the absence of WUS, stem cell abundance is regulated by similar mechanism as described in Arabidopsis, although WUS function is replaced by some unknown factor(s).

Cytokinin Signaling Both Induces and Inhibits SAM Formation.

Our analysis of Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 triple mutants and higher order Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3, Pprpk2 Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3, and Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 mutants revealed several unexpected phenotypes. First, we observed that Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 mutants make ectopic stem cells, contrasting with cytokinin’s role promoting stem cell formation. We proposed several models to explain the counterintuitive Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 and higher-order mutant phenotypes. An incoherent feedforward model where cytokinin signaling buffers stem cell initiation through a PpCLV1- and PpRPK2-independent pathway successfully replicated the trends seen in the empirical data, over a wide range of mutant genotypes and hormone treatments. However, because little is known about genes promoting SAM formation in P. patens, it is difficult to speculate as to the nature of z in the model. It is possible that auxin signaling, which is upstream of stem cell formation on filaments and gametophores, is deregulated in Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 mutants (22, 36). However, known stem cell–inducing genes downstream of auxin are not modulated by cytokinin treatment (36, 37). Thus, elucidating the identity of z requires better understanding of cytokinin-responsive genes in gametophores. Recently, PpRPK2 was shown to modulate auxin homeostasis and transport in protonema (34). If this interaction holds true in the gametophore, it is also possible that auxin signaling is represented by the y portion of the model.

Common Molecular Mechanisms Can Underlie Disparate Developmental Functions across Plant Evolution.

Similarities and differences in stem cell regulation between the moss P. patens and Arabidopsis raise important questions about the evolution of this signaling network. Current phylogenies support a monophyletic clade containing mosses and liverworts, such that mosses and liverworts are equally related to flowering plants. However, unlike in P. patens and Arabidopsis, CLV1 function in the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha enhances stem cell specification (38). Interestingly, MpCLV1-mediated control of the meristem in Marchantia is also independent of WOX genes, supporting the later recruitment of WOX genes to regulation of the SAM (38). Since SAM specification occurs in a WUS-independent pathway in bryophytes, is there also a WUS-independent pathway in angiosperms? Overall, it is curious how the P. patens SAM transcriptome is highly enriched for orthologs of genes that function in angiosperm SAMs, but lacks a role for WOX genes, which establish the canonical connection between CLV and cytokinin signaling in flowering plants. These observations raise the question of whether similarities between moss and flowering plant stem cell specification pathways are convergent or whether CLV–cytokinin interactions are ancient, with WOX genes incorporated with the evolution of the multicellular SAM.

Materials and Methods

P. patens Culture.

The Gransden 04 strain of P. patens was used for all experiments (39). To propagate P. patens, protonemal tissue was blended in 5 to 7 mL of sterile water using a Dremel with a custom propeller blade attachment, and 1 to 2 mL of moss tissue was inoculated onto BCDAT (minimal media supplemented with ammonium tartrate) (SI Appendix, Table S4) plates overlain with sterile cellophane. Moss was grown under continuous light at 25 °C. For phenotyping gametophores, small samples of freshly blended protonema were placed onto BCD agar media supplemented with the specified amount of filter sterilized BAP. These tufts of tissue grew for the specified time before gametophores were dissected for imaging.

P. patens Transformation.

P. patens transformation (40) was conducted as in Whitewoods et al. (16) but with smaller amounts of tissue (two to four plates of protonemal tissue) and DNA (10 µg). Smaller transformations were possible due to the efficiency of CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis. Transformants were subjected to a single round of selection with 20 mg/L G418 in BCDAT plates 7 d after transformation.

Plasmid Construction.

For routine cloning of gRNAs into a transient expression vector suitable for use in P. patens, we used the pENT-U6pro::Bsa1:sgRNA and pENT-U3pro::Bsa1:sgRNA constructs generated previously (16). To clone gRNA expression vectors, oligonucleotides with overhangs complementary to the type IIS restriction enzyme BsaI cut sites (GGC and CAT for U3 and U6 promoters, and AAAC to ligate on the 3′ end with, and were annealed. The annealed oligonucleotides were ligated into pENT-U3pro::Bsa1:sgRNA or pENT-U6pro::Bsa1:sgRNA digested with BsaI. Clones were verified by sequencing. gRNA sequences were selected using the CRISPOR online service (41). We tried four gRNAs for the PpCLV1a gene before finding one that cleaved effectively; the first gRNAs designed for PpCLV1b and PpRPK2 genes successfully induced mutations.

Staining and Imaging.

Gametophores were dissected from the periphery of tufts and stained with 5 µg/mL propidium iodide solution. Imaging was conducted using a Zeiss 710 laser scanning confocal microscope. We used a 514-nm laser for excitation and collected an emission spectrum from 566 to 650 nM. Images were captured using either a 20× water immersion numerical aperture 1.0 or 10× lens.

Gametophore Samples.

For Ppclv1 and Pprpk2 mutant lines, the previously characterized Ppclv1ab line 6 and Pprpk2 line a32 were used for all imaging and analysis. For the Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 triple mutant, Ppclv1a Ppclv1b Pprpk2 line 3 was used. All data for these lines were collected from tissue grown and imaged on over three separate occasions, with the exception of 10-nM BAP treatments, which were replicated twice. For Ppchk1 Ppchk2 Ppchk3 and higher order Ppclv1a Ppclv1b, Pprpk2, and Ppchk mutants, data represent a mix of CRISPR lines for each genotype grown and imaged on two separate occasions (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 D and E).

Ectopic Apical Cell Quantification.

Areas of stem visible on maximum intensity projections (not including phyllids) were manually measured using FIJI (42). These stem measurements were used to account for variability in size and developmental stage across samples. Ectopic apical cells were identified as triangular cells and distinguished from illusory tetrahedral cells seen in maximum intensity projections by manually looking through Z stacks. Regions of ectopic growth and phyllid production were also counted as ectopic stem cells.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using the R statistical programming language. For regressions, genotypes were coded as a combination of two factors (Ppclv1 and Pprpk2) for the purposes of our analysis, since Ppclv1a and Ppclv1b single mutants were not analyzed separately. The effects of mutating PpCLV1 and PpRPK2 and of growth on 10 nM and 100 nM BAP as well as the interactions between these three factors (PpCLV1, PpRPK2, and the exogenous cytokinin) were modeled using a Poisson general linear model that included stem area as an offset [model: glm(total_ectopic ∼ clv1 + rpk2 + exock + clv1L:rpk2L + clv1L:exock + rpk2L:exock + (log(area)), family = “poisson”]. BAP concentrations were treated as a continuous variable with levels of 0, 10, and 100.

qPCR.

RNA was extracted from gameotophores using the Qiagen plant RNeasy Mini Kit, followed by reverse transcription with the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR. Reactions were run in a Roche Lightcycler 480 with three biological and three technical replicates for each sample. 60s ribosomal RNA was used as a reference, and data were analyzed using the delta delta Ct method (43).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Cornell Statistical Consulting unit and Celine Cammarata for advice on statistical analyses and data processing. We thank Klaus von Schwartzenberg for sharing the cytokinin histidine kinase triple mutant lines. We also thank Jill Harrison and Zoe Nemec Venza for thoughtful and helpful discussions about this work. We finally would like to acknowledge Jill Harrison, Zoe Nemec Venza, Mingyuan Zhu, Kate Harline, and Shuyao Kong for comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by NSF IOS-1238142 to M.J.S. and NSF IOS-1553030 to A.H.K.R., the Schmittau-Novak Small Grant to J.C., the Cornell Provost Diversity Dissertation Completion Fellowship to J.C., funding from the Weill Institute for Cell and Molecular Biology to A.H.K.R., and the NSF-funded Boyce Thompson Institute Cornell Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) program support for C.M.F. (REU 1850796).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2116860119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All data are included in the article and the SI Appendix. The R code to run the models is available in the SI Appendix. The moss lines or CRISPR constructs will be shared upon request.

References

- 1.Brand U., Fletcher J. C., Hobe M., Meyerowitz E. M., Simon R., Dependence of stem cell fate in Arabidopsis on a feedback loop regulated by CLV3 activity. Science 289, 617–619 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher J. C., Brand U., Running M. P., Simon R., Meyerowitz E. M., Signaling of cell fate decisions by CLAVATA3 in Arabidopsis shoot meristems. Science 283, 1911–1914 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rojo E., Sharma V. K., Kovaleva V., Raikhel N. V., Fletcher J. C., CLV3 is localized to the extracellular space, where it activates the Arabidopsis CLAVATA stem cell signaling pathway. Plant Cell 14, 969–977 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinoshita A., et al. , RPK2 is an essential receptor-like kinase that transmits the CLV3 signal in Arabidopsis. Development 137, 3911–3920 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kayes J. M., Clark S. E., CLAVATA2, a regulator of meristem and organ development in Arabidopsis. Development 125, 3843–3851 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark S. E., Running M. P., Meyerowitz E. M., CLAVATA3 is a specific regulator of shoot and floral meristem development affecting the same processes as CLAVATA1. Development 121, 2057–2067 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller R., Bleckmann A., Simon R., The receptor kinase CORYNE of Arabidopsis transmits the stem cell-limiting signal CLAVATA3 independently of CLAVATA1. Plant Cell 20, 934–946 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoof H., et al., The stem cell population of Arabidopsis shoot meristems is maintained by a regulatory loop between the CLAVATA and WUSCHEL genes. Cell 100, 635–644 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yadav R. K., et al. , WUSCHEL protein movement mediates stem cell homeostasis in the Arabidopsis shoot apex. Genes Dev. 25, 2025–2030 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daum G., Medzihradszky A., Suzaki T., Lohmann J. U., A mechanistic framework for noncell autonomous stem cell induction in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 14619–14624 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laux T., Mayer K. F. X., Berger J., Jürgens G., The WUSCHEL gene is required for shoot and floral meristem integrity in Arabidopsis. Development 122, 87–96 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer K. F. X., et al. , Role of WUSCHEL in regulating stem cell fate in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Cell 95, 805–815 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison C. J., Roeder A. H. K., Meyerowitz E. M., Langdale J. A., Local cues and asymmetric cell divisions underpin body plan transitions in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Curr. Biol. 19, 461–471 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank M. H., Scanlon M. J., Transcriptomic evidence for the evolution of shoot meristem function in sporophyte-dominant land plants through concerted selection of ancestral gametophytic and sporophytic genetic programs. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 355–367 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cammarata J., Scanlon M. J., A functionally informed evolutionary framework for the study of LRR-RLKs during stem cell maintenance. J. Plant Res. 133, 331–342 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitewoods C. D., et al. , CLAVATA was a genetic novelty for the morphological innovation of 3D growth in land plants. Curr. Biol. 28, 2365–2376.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nardmann J., Werr W., The invention of WUS-like stem cell-promoting functions in plants predates leptosporangiate ferns. Plant Mol. Biol. 78, 123–134 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikeda M., Mitsuda N., Ohme-Takagi M., Arabidopsis WUSCHEL is a bifunctional transcription factor that acts as a repressor in stem cell regulation and as an activator in floral patterning. Plant Cell 21, 3493–3505 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin H., et al. , Evolutionarily conserved repressive activity of WOX proteins mediates leaf blade outgrowth and floral organ development in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 366–371 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakakibara K., et al. , WOX13-like genes are required for reprogramming of leaf and protoplast cells into stem cells in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Development 141, 1660–1670 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cammarata J., Roeder A. H., Scanlon M. J., Cytokinin and CLE signaling are highly intertwined developmental regulators across tissues and species. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 51, 96–104 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coudert Y., et al. , Three ancient hormonal cues co-ordinate shoot branching in a moss. eLife 4, 1–26 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng W. J., et al. , Type-B ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATORs is critical to the specification of shoot stem cell niche by dual regulation of WUSCHEL. Plant Cell 29, 1357–1372 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon S. P., et al. , Pattern formation during de novo assembly of the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Development 134, 3539–3548 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark S. E., Williams R. W., Meyerowitz E. M., The CLAVATA1 gene encodes a putative receptor kinase that controls shoot and floral meristem size in Arabidopsis. Cell 89, 575–585 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishida K., Yamashino T., Nakanishi H., Mizuno T., Classification of the genes involved in the two-component system of the moss Physcomitrella patens. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 74, 2542–2545 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Schwartzenberg K., et al. , CHASE domain-containing receptors play an essential role in the cytokinin response of the moss Physcomitrella patens. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 667–679 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barker E. I., Ashton N. W., Heteroblasty in the moss, Aphanoregma patens (Physcomitrella patens), results from progressive modulation of a single fundamental leaf developmental programme. J. Bryol. 35, 185–196 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishiyama T., et al. , Comparative genomics of Physcomitrella patens gametophytic transcriptome and Arabidopsis thaliana: Implication for land plant evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 8007–8012 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hord C. L. H., Chen C., Deyoung B. J., Clark S. E., Ma H., The BAM1/BAM2 receptor-like kinases are important regulators of Arabidopsis early anther development. Plant Cell 18, 1667–1680 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui Y., et al. , CIK receptor kinases determine cell fate specification during early anther development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 30, 2383–2401 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimizu N., et al. , BAM 1 and RECEPTOR-LIKE PROTEIN KINASE 2 constitute a signaling pathway and modulate CLE peptide-triggered growth inhibition in Arabidopsis root. New Phytol. 208, 1104–1113 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nimchuk Z. L., CLAVATA1 controls distinct signaling outputs that buffer shoot stem cell proliferation through a two-step transcriptional compensation loop. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006681 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nemec-Venza Z., et al. , CLAVATA modulates auxin homeostasis and transport to regulate stem cell identity and plant shape in a moss. New Phytol. 234, 149–163 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gordon S. P., Chickarmane V. S., Ohno C., Meyerowitz E. M., Multiple feedback loops through cytokinin signaling control stem cell number within the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16529–16534 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aoyama T., et al. , AP2-type transcription factors determine stem cell identity in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Development 139, 3120–3129 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moody L. A., et al. , Genetic regulation of the 2D to 3D growth transition in the Moss Physcomitrella patens report genetic regulation of the 2D to 3D growth transition in the Moss Physcomitrella patens. Curr. Biol. 28, 1–6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirakawa Y., et al. , Induction of multichotomous branching by clavata peptide in Marchantia polymorpha. Curr. Biol. 30, 3833–3840.e4 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashton N. W., Cove D. J., The isolation and preliminary characterisation of auxotrophic and analogue resistant mutants of the moss, Physcomitrella patens.Mol. Gen. Genet. MGG 154, 87–95 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaefer D., Zryd J.-P., Knight C. D., Cove D. J., Stable transformation of the moss Physcomitrella patens. Mol. Gen. Genet. 226, 418–424 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haeussler M., et al. , Evaluation of off-target and on-target scoring algorithms and integration into the guide RNA selection tool CRISPOR. Genome Biol. 17, 148 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schindelin J., et al. , Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D., Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Δ Δ C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the article and the SI Appendix. The R code to run the models is available in the SI Appendix. The moss lines or CRISPR constructs will be shared upon request.