ABSTRACT

Periodontitis is among most common human inflammatory diseases and characterized by destruction of tooth-supporting tissues that will eventually lead to tooth loss. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by chronic hyperglycemia which results from defects in insulin secretion and/or insulin resistance. Numerous studies have provided evidence for the inter-relationship between DM and periodontitis that has been considered as the sixth most frequent complication of DM. However, the mechanisms are not fully understood yet. The impact of DM on periodontitis through hyperglycemia and inflammatory pathways is well described, but the effects of DM on oral microbiota remain controversial according to previous studies. Recent studies using next-generation sequencing technology indicate that DM can alter the biodiversity and composition of oral microbiome especially subgingival microbiome. This may be another mechanism by which DM risks or aggravates periodontitis. Thus, to understand the role of oral microbiome in periodontitis of diabetics and the mechanism of shifts of oral microbiome under DM would be valuable for making specific therapeutic regimens for treating periodontitis patients with DM or preventing diabetic patients from periodontitis. This article reviews the role of oral microbiome in periodontal health (symbiosis) and disease (dysbiosis), highlights the oral microbial shifts under DM and summarizes the mechanism of the shifts.

KEYWORDS: Diabetes mellitus, periodontitis, periodontal disease, subgingival microbiome, oral microbiome, next-generation sequencing

Introduction

Periodontal diseases comprise a wide range of inflammatory conditions of periodontal supporting tissues including gingiva, alveolar bone and periodontal ligament [1]. Gingivitis is the localized inflammation of the gingiva, while periodontitis is characterized by the loss of gingiva, alveolar bone and periodontal ligament. The deep periodontal ‘pocket’ is a hallmark of the disease and can eventually lead to tooth loss [2]. Periodontal diseases are currently considered to share a similar aetiopathogenesis, which is initiated and sustained by the oral microbial biofilm [2]. Other factors such as gene susceptibility and environmental conditions also influence the morbidity of the diseases [3]. Moreover, recent evidence has indicated that periodontitis is epidemiologically associated with several systemic disorders such as atherosclerosis, adverse pregnancy outcomes, rheumatoid arthritis, aspiration pneumonia, certain cancers and diabetes mellitus [4].

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by chronic hyperglycemia which results from defects in insulin secretion and/or insulin resistance over a prolonged period of time. Generally, there are two main types of DM: type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [5]. T1DM is due to autoimmune β-cell destruction, usually leading to absolute insulin deficiency, including latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood [5]. T2DM is due to a progressive loss of adequate β-cell insulin secretion and insulin resistance [5,6]. According to the World Health Organization, DM currently affects approximately 422 million people globally and 1.6 million deaths are directly attributed to DM each year. In 2045, the number of diabetic patients is expected to increase to 629 million [7]. Of all the diagnosed diabetes cases, T2DM accounts for 90%-95% [5] and affects more than 380 million people worldwide, representing 8.8% of individuals aged 20–79 years [8]. Moreover, T2DM may cause long-term complications including retinopathy, nephropathy, peripheral neuropathy and atherosclerotic cardiovascular, peripheral arterial and cerebrovascular diseases [9]. Also, periodontal diseases are highly likely to occur and aggravate in individuals with DM especially in poorly controlled diabetics [10]. Likewise, since periodontal diseases may contribute to the body’s overall inflammatory burden, individuals with periodontitis are more potentially to develop DM [2]. Thus, a ‘two-way’ relationship between the two diseases is established [10].

The impact of DM on periodontal diseases through hyperglycemia and inflammatory pathways is well described [10–12], while the effects of DM on oral microbiome remains controversial. Previous studies failed to reach a consensus on that DM affects the oral microbiome [13], possibly because of the limited numbers of bacteria being surveyed [14]. In recent years, the development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies allowed us to study the oral microbiome more comprehensively and their increasing affordability also facilitated such studies to become the mainstream. Thus, the use of NGS has broadened and deepened our understanding about whether DM may exert a selective pressure on oral microbiome by comprehensively comparing the oral microbiome from nondiabetic and diabetic individuals with and without periodontitis. In the next sections, we will review the oral microbiome in health and periodontitis, highlight the alteration of oral microbiome especially subgingival microbiome under DM and summarize the mechanism by which DM changes oral microbiome. The search strategy and inclusion criteria are as follows: search keywords are ‘oral microbiome’ or ‘subgingival microbiome’, ‘diabetes’ or ‘diabetes mellitus’, ‘periodontitis’ or ‘periodontal diseases’ and ‘next-generation sequencing’; search databases include MEDLINE and WEB OF SCIENCE; inclusion criteria are human studies or animal studies on oral microbiome in diabetics by using next-generation sequencing technology and comparing with non-diabetics.

Oral microbiome and periodontitis

The concern on oral biofilms has been over three hundred years since Antony van Leeuwenhoek peered and observed the existence of microbes from his own dental plaque with a microscope that he constructed himself in the 1700s [15]. With the development of technology, quantities of microorganisms have been isolated from the oral cavity and extensively studied by using cultivation and non-traditional molecular-based approaches [16]. More recently, the next-generation sequencing technology enables microbiologists to study the microorganisms at a specific niche as a whole in unprecedented detail [17]. Consequently, the term ‘microbiome’ was proposed ‘to signify the ecological community of commensal, symbiotic, and pathogenic microorganisms that literally share our body space and have been all but ignored as determinants of health and disease’ by the Nobel laureate microbiologist, Joshua Lederberg [18]. The Human Oral Microbiome Database (HOMD) contains comprehensive information about approximately 775 prokaryote species including both cultivable and non-cultivable isolates that inhabit in the oral cavity, links sequence data with phenotypic, phylogenetic, clinical and bibliographic information and provides tools for use in understanding the role of the microbiome in health and disease [19].

Due to the local environmental features of the oral cavity, members of the oral microbiome co-aggregate and interact with each other by synergism, signaling or antagonism to best adapt to the surrounding environment [20]. Meanwhile, the oral microbial communities interact with host, affecting the oral health of the host. Normally, the oral microbial communities are stable and symbiotic in healthy individuals with healthy food habits and good hygiene, maintaining homeostasis with the host’s local immune system [21–23]. Once the balance was interrupted by external factors such as food habits, tobacco and alcohol consumption, stress, hormonal imbalance, puberty, poor oral hygiene and diabetes, the microbial communities dramatically shift from a symbiotic state to a dysbiotic state, which induces diseases such as periodontitis [16,24,25]. The dysbiotic microbiome can be characterized by three different scenarios that are not mutually exclusive and may occur simultaneously, viz, the overall loss of microbial diversity, relative reduction of the beneficial species and increase of the pathogenic species [26,27].

The concept of loss of biodiversity indicates a decline of richness, numbers and distributing evenness of species in a biological community, which may eventually lead to the breakdown of an ecosystem [26,27]. Several studies have reported that loss of biodiversity in dental caries is associated with the severity of the disease [28–33]. However, changes in microbial biodiversity remain controversial in periodontitis with some studies reporting loss of biodiversity in disease [34–38] and others indicating the opposite [39–41]. The latter proposed that the increased microbial diversity in periodontitis is due to the increased amount of nutrients derived from host’s tissue degradation in inflammation [39,40]. In addition, there are also reports indicating no significant difference in oral microbial biodiversity between the healthy individuals and the patients with periodontitis [42,43]. The discrepancy of the results may be attributed to differences in studying methods such as sequencing methods, sequencing region, sequencing depth and sampling sites (periodontal pocket depths) [17,39,44].

Another characteristic of dysbiosis is the loss of some beneficial microorganisms [26]. Those species are important for the development and maturation of the local immune system in the oral cavity [19,26]. Those species stimulate the host to generate appropriate immune response, which can protect the host against oral pathogens and from carcinogenic metabolites [45,46]. Moreover, those beneficial microorganisms also participate in the nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway [47]. Thus, those microorganisms can offer several benefits to the host. Reduction of those beneficial species may weaken the host’s ability to fight against the pathogenic bacteria and predisposing the host to generate an excessive immune response against the host’s own tissue when the host is exposed to carcinogenic metabolites and detrimental vascular changes [19,26]. Loss of beneficial species is an important factor in the development of chronic periodontitis that is persistent and excessive inflammation of periodontal tissues causing the destruction of gingiva, alveolar bone and periodontal ligament and even tooth loss [27].

The most apparent feature of dysbiosis is the overgrowth of pathogenic microorganisms, e.g. the red complex (Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola and Tannerella forsythia) [48]. Although the subgingival microbiome within the healthy periodontal state contains those classically defined oral pathogens, they do not induce any immune responses due to their relatively low abundance in the healthy state [49]. Those microorganisms that do not dominate in the healthy state dramatically increase in periodontitis [17]. But they do not solely cause periodontitis, rather, they synergize to initiate the disease [32]. The recent hypothesis for pathogenesis of periodontitis has been concluded into a Polymicrobial Synergy and Dysbiosis (PSD) model [50,51], which is consistent with the human microbiome studies, the mechanistic studies in animal models and the ‘ecological plaque’ hypothesis, which indicates that environmental factors determine the outgrow of specific pathogenic bacteria, known as pathobionts [32,52,53]. The PSD model proposes that the periodontal disease is not initiated by individual or several causative pathogens but rather by a synergistic polymicrobial community, within which specific constituents, or combinations of functional genes, fulfil distinct roles that converge to shape and stabilize a dysbiotic microbiota, which perturbs host homeostasis [32,54]. For instance, the pathogenic functions require a series of specific molecules instead of a sole molecule. Those molecules include adhesins, receptors, proteolytic enzymes and proinflammatory surface ligands, which cannot be expressed by one species of pathogen. Rather, synergism of the pathogens expressing those molecules sustains a heterotypic and dysbiotic microbial community and acts as a community virulence factor that elicits a non-resolving and tissue-destructive host response [50,55].

Oral microbiome under DM

Overall, regardless of periodontal health, DM patients exhibited distinct oral microbial features (microbial composition, biological diversity and relative abundance of specific bacteria) compared with healthy controls (Table 1) [56–60]. Based on principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), patients with T2DM and healthy cohorts revealed different oral microbial clusters [56,58]. A clear reduced biological and phylogenetic diversity of oral microbiome was apparent in diabetic and pre-diabetic individuals in comparison with that in the normoglycemic controls [59,60]. The phylum Actinobacteria was present significantly less abundant among patients with T2DM than among the controls [56,57]. Genera Actinomyces and Atopobium were associated with 66% and 72% decreased risk of diabetes with p-values of 8.9 × 10–3 and 7.4 × 10–3, respectively [57]. While another study indicated higher abundances of Actinomyces and Selenomonas with lower abundance of Alloprevotella in diabetic patients compared with non-diabetic individuals [58], a subsequent correlational analysis of the differential bacteria and clinical characteristics demonstrated that the oral microbiomes were related to drug treatment for DM and certain pathological changes [60]. But the treatment did not lead to microbial recovery [60]. The subgingival microbiome of diabetics with healthy periodontium reveals lower species richness than non-diabetic healthy controls [60,61], but contains relatively higher abundances of periodontally pathogenic red complex species and a potentially opportunistically pathogenic orange complex and lower abundances of healthy-compatible species [61,62]. This indicates that the subgingival microbiome in diabetic patients with clinically healthy periodontium has a disease-associated community framework, predisposing the individuals to develop periodontal diseases [61–63].

Table 1.

Recent studies on oral (subgingival) microbiome of diabetic patients (with periodontitis) using NGS

| Year | Authors | Study design | Sample size | Groups | Sampling site | Sequencing region | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | Balmasova et al [66] | Cross-sectional | 46 |

|

Four spots of the periodontal pockets/sulcus at the level of the second molars | V3–V4 region and shotgun sequencing for metagenomic analysis |

|

| 2020 | Matsha et al [67] | Cross-sectional | 128 |

|

Subgingival crevice between the maxillary second premolar and the first upper molar | V2, V3, V4, V6-V7, V8 and V9 regions of 16S rRNA |

|

| 2020 | Chen et al [56] | Cross-sectional | 442 |

|

Buccal mucosa | V1–V2 region of 16S rRNA |

|

| 2020 | Yang et al [60] | Cross-sectional | 102 |

|

Salivary samples | V3-V4 region of 16S rRNA |

|

| 2019 | Farina et al [65] | Cross-sectional | 12 |

|

Subgingival plaques without bleeding on probing in P- patients; subgingival plaques at the deepest probing depth among those positive to bleeding on probing in P+ patients. | Metagenomic shotgun sequencing |

|

| 2019 | Shi et al [62] | Longitudinal | 31 |

|

Subgingival plaques | Metagenomic shotgun sequencing |

|

| 2019 | Saeb et al [59] | Cross-sectional | 44 |

|

Saliva samples | V2, V3, V4, V6, V7, V8 and V9 regions of 16S rRNA |

|

| 2018 | Longo et al [68] | Cross-sectional | 21 |

|

Mesio-buccal sites of teeth with medium (PD 4–6 mm) and deep pockets (PD ≥7 mm) in two contralateral quadrants | V5-V6 region of 16S rRNA |

|

| 2017 | Long et al [57] | Cross-sectional |

|

Mouth rinse samples | V4 region of 16S rRNA |

|

|

| 2017 | Ganesan et al [61] | Cross-sectional | 175 |

|

Deep (diseased) sites and shallow (healthy) sites of subjects with periodontitis; randomly selected interproximal sites in periodontally healthy subjects | V1–V3 and V7–V9 regions of 16S rRNA |

|

| 2017 | Ogawa et al [58] | Cross-sectional | 24 |

|

Salivary samples | Sequencing V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene |

|

| 2013 | Zhou et al [63] | Cross-sectional | 31 |

|

Subgingival plaque samples from the deepest sites of the molars | V1-V3 region of 16S rRNA |

|

| 2012 | Casarin et al [64] | Cross-sectional | 23 |

|

The bottom of the periodontal pockets | Partial sequence (600bp) of 16S rRNA |

|

In diabetic patients with periodontitis, oral microbial profiles also reveal distinct features compared with non-diabetic patients with periodontitis (Table 1) [60,64,65], with reported either increased [66,67] or reduced microbial diversity [61]. The subgingival microbiome of diabetic patients with periodontitis exhibited relatively higher abundances of Leptotrichiaceae, Neisseriaceae and Dialister; Lactobacillus, Corynebacterium and Pseudomonas; Saccharibacteria, Aggregatibacter, Neisseria, Gemella, Eikenella, Selenomonas, Actinomyces, Capnocytophaga, Fusobacterium, Veillonella, Streptococcus and Actinomyces and relatively lower abundances of Filifactor, Treponema, Porphyromonas, Prevotella, and Parvimonas than non-diabetic patients with periodontitis, while both groups showed similar clinical manifestations [61,63,65,66]. Furthermore, the difference of subgingival microbiome between the periodontitis state and the healthy state in diabetic patients was less prominent than that in non-diabetic patients, since the difference of subgingival microbiome of the disease state and the healthy state in T2DM patients could not be clearly distinguished [62]. It should be mentioned that the pocket depth and bleeding had no significant impact on the subgingival microbiome in diabetic patients [61,66,68], which is different from the cases of non-diabetic patients with periodontitis [39,62]. After treatment (in the resolved state), the subgingival microbiome of both T2DM patients and non-diabetic individuals resembles the subgingival microbiome in the healthy state [62]. However, in the resolved state, the subgingival microbiome of T2DM patients revealed lower abundances of orange complex and red complex species than non-diabetic individuals, which indicates that T2DM patients after periodontal treatment are less tolerant to the periodontitis-associated species and thus have lower periodontal pathogens to maintain the clinically resolved periodontal health [62].

To confirm the effect of DM on oral microbiome and its association with periodontitis, an animal study was carried out by Xiao et al [69]. In this study, the oral microbiome of two groups of mice (one was prone to develop DM and the other was normal littermates) presents similar oral microbiome at the beginning, but revealed apparently different after one group became diabetic [69]. DM reduced the diversity of total oral microbiome in mice but increased the levels of Proteobacteria (Enterobacteriaceae) and Firmicutes (Enterococcus, Staphylococcus and Aerococcus) [69], which was associated with pathologic changes reported in other studies [14]. Furthermore, by transferring the oral microbiota of diabetic and non-diabetic mice to germ-free recipient mice, greater periodontal inflammation and bone loss were observed in the mice receiving bacteria from diabetic mice [69]. Moreover, the same group also found that IL-17 played an important role in the oral microbial alteration of diabetic mice, as local inhibition of IL-17 could not only render the oral microbiome of diabetic mice similar to that of non-diabetic mice but also reduce the pathogenicity of oral microbiota in diabetic mice [69]. However, since the oral microbiome of mice does not share similarity to human oral microbiome, whether these findings are suitable for human requires further studies [70,71].

Further studies indicated that prediabetic and diabetic periodontitis patients with different glycemic levels may harbor different subgingival microbiome [61,67,68]. Subgingival microbiome in periodontitis patients with inadequate glycemic levels (HbA1c ≥ 8%) revealed a reduced biodiversity compared to patients with adequate glycemic levels (HbA1c < 7.8%) [68]. Levels of recognized periodontopathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia and Treponema denticola that are indicative of periodontitis, did not differ between diabetic patients with different glycemic levels [68]. Higher abundances of species that are able to use carbohydrates or their by-products within families Streptococcaceae, Prevotellaceae and Veillonellaceae were seen in patients with a higher glycemic level, whereas those forming butyrate/pyruvate were decreased in patients with inadequate glycemic control [68]. The increased level of S. agalactiae in diabetic patients with an inadequate glycemic level belongs to Group B streptococci (GBS) and is an important invasive pathogen in newborn infants, elderly and those with chronic diseases [68]. Prevotella produces acetate and succinate from glucose fermentation, and the cultivable species Alloprevotella are saccharolytic, producing acetate and major amounts of succinate [68,72,73]. Their growth in liquid media is stimulated by fermentable carbohydrates [72]. The increase of Veillonellaceae in diabetic patients with periodontitis was due to the utilization of fermentation catabolites produced by the fermenting species [68]. This group of bacteria convert lactate and succinate to acetate and propionate and may play an active role in reducing the environment acidity [74,75].

As periodontitis is driven by polymicrobial effects, microorganisms may harbor redundant roles contributing to the development of periodontitis. Thus, detecting the changes of microbial pathways in DM may provide more intrinsic information about how DM predisposes patients to develop periodontitis. In both diabetic and nondiabetic patients with periodontitis, 4 functional pathways of virulence factors were enriched [62]. They are pathways associated with cell motility (bacterial motility, flagellar assembly and bacterial chemotaxis) and a signal transduction pathway (two-component system) [62]. In addition, three pathogenic pathways were less prevalent in T2DM patients with periodontitis than nondiabetic patients with periodontitis [62]. There are two pathways in lipid metabolism (ether lipid metabolism and arachidonic acid metabolism) and one pathway in carbohydrate metabolism (inositol phosphate metabolism), which are linked via lipoprotein-associated phospholipases, a group of inflammatory enzymes associated with oral infections [62]. In contrast, three pathways of carbohydrate metabolism (butanoate metabolism, pentose and glucuronate interconversions, and ascorbate and aldarate metabolism) were more prevalent in T2DM than in non-T2DM in both the periodontitis state and the healthy state [62]. The ascorbate and aldarate metabolism pathway has been associated with inflammatory diseases including periodontitis [76,77] and T2DM [78]. Microbial butanoate metabolism has been indicated as a metabolic signature of periodontal inflammation [79], and butyrate can influence insulin sensitivity [80]. These results might account for the epidemiological studies, which support that periodontal infection has an adverse effect on glycemic control [62].

Taken together, recent studies on oral microbiome in diabetics using NGS have provided great information about the oral microbial alteration under DM (Table 1), which would contribute to understanding the inter-relationship between periodontitis and DM.

Changes of periodontal immune status in DM

Diabetic complications are frequently linked to increased inflammation, and substantial evidence has indicated that DM increases the inflammation of periodontal tissues. Both T1DM and T2DM lead to increased expression of inflammatory cytokine and chemokine in human periodontal tissues [81,82]. Those cytokines include tumor necrosis factor, prostaglandin E2, interleukin-1beta, interleukin-17, interleukin-23 and interleukin-6 [83,84]. On the contrary, anti-inflammatory factors such as interleukin-4, interleukin-10, transforming growth factor-beta and anti-inflammatory lipid-based mediators are reduced in diabetics, along with reduction of anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells and M2 macrophages [85–87].

The increased expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in diabetics leads to increased vascular permeability and recruitment of inflammatory cells in response to bacterial challenge or other pro-inflammatory stimuli [83,88,89]. Moreover, the behaviors of leukocytes are altered under DM [90]. For instance, DM reinforced the interaction between neutrophils and gingival endothelial cells by increasing the expression of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 and CD11a on neutrophils and P-selectin expression on endothelial cells [89]. Studies of other diabetic complications indicate that DM increases pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage polarization [91,92]. The functions of monocytes and macrophages in patients with DM are influenced by their interactions with the local environment within periodontal tissues, including interactions between receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGEs) and advanced glycation end products (AGEs), toll-like receptor signaling, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and others [90].

High glucose content can lead to the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which are products of irreversible non-enzymatic glycation and glycoxidation of proteins, including lipoproteins, intracellular proteins and plasma proteins [90,93–95]. The excessive accumulation of AGEs can alter cytoplasmic and nuclear factors and induce the formation of stable abnormal cross-links on collagen that changes its structure and function [96]. AGEs also increase the expression of receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGEs) in gingiva [90,97]. The interaction between AGEs and RAGEs can modulate cell behavior and inflammation in periodontal tissues. For instance, the binding of AGEs and RAGEs on gingival fibroblasts can activate nuclear factor-kappa B, which induces the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor and stimulates the production of ROS [98]. Although RAGEs signaling does not directly initiate inflammation, it perpetuate and amplify the responses of monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, endothelial cells and chondrocytes in the context of inflammatory processes, diabetes complications and atherosclerosis [99]. Interference with RAGEs signaling under chronic inflammatory conditions results in improvement in clinical and biochemical signs of inflammation, including suppression in periodontitis-associated bone loss and decreased generation of the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6 in gingival tissues [100].

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) including free radicals (e.g. superoxide O ˙2− and hydroxyl radicals ˙OH), nonradical oxygen species [e.g. hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)] and reactive lipids are generated by cellular functions such as phagocytosis and mitochondrial cell respiration. An overproduction of superoxide by the mitochondrial electron transport chain is considered as the unifying underlying pathological mechanism of diabetic complications [93]. Chronic exposure to high glucose content induces the production of higher levels of ROS that may cause damage to DNA and structural components of cells and cell apoptosis [101]. ROS may also activate mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-kappa B signaling, resulting in the production and release of multiple inflammatory factors [83,102]. Diabetic patients have an increased number of inducible nitric oxide synthase-positive cells in the periodontium, and levels of lipid peroxides are elevated in the gingival crevicular fluid of T2DM patients [81,103]. There is a significant correlation between lipid peroxidation and periodontal inflammation in T2DM patients, which suggests that lipid peroxides may contribute to more severe periodontal inflammation [81,83,103]. Moreover, antioxidant capacity is reduced in diabetic patients, which also contributes to the increased levels of ROS and their adverse impact on periodontium indirectly [83].

Toll-like receptors represent an important mechanism by which the host detects a variety of invading microorganisms and trigger the expression of genes that control the innate immune system when binding to their ligands such as LPS, bacterial DNA, double-stranded RNA, peptidoglycans and lipoproteins [90]. There is some evidence for possible alterations in toll-like receptor expression in the gingival tissues of patients with DM [90]. Elevated expression of toll-like receptor 2 and toll-like receptor 4 is found in gingival tissue biopsies from patients with DM and periodontitis compared with patients with periodontitis alone [83,104]. In vitro studies also indicated increased expression of toll-like receptor 2 in human gingival fibroblasts cultured with high levels of glucose [105].

An important part of the periodontal immune system that has not received much attention is the gingival epithelial barrier. Gingival epithelium serves as an effective barrier in protecting the gingival connective tissue from oral or subgingival microorganisms [106]. The structure and function of gingival epithelium may also be altered by DM since the keratinocytes are affected by DM [107,108]. But the actual impact of DM on barrier function requires further studies to be fully understood.

Mechanisms that DM affects oral microbiome

While recent evidence indicates that DM can alter the oral microbiome, specific mechanisms are not fully understood. According to the ecological plaque hypothesis, changes of the microbiome may be determined by the inherent characteristics of the microbial environment such as oxygen tension, pH, redox potential and nutrition supply [109]. Thus, the oral environment may act as filters to select species that holds suitable habitat within this environment. Besides, the formation of microbial communities also results from interactions of the community members with different metabolic, structural and nutritional traits.

In this context, the inflammation imposes a strong ecological selective pressure that drives dysbiosis with the expansion of periodontitis-associated microbial species at the expense of health-compatible species [32,110]. Destruction of periodontal tissues induced by the inflammation generates substances such as collagen fragments and heme-containing compounds, which could be sources of amino acids and iron for those microbial species that utilize them [111]. Those substances can be transferred via increased gingival crevicular fluid into the gingival crevice, fostering the outgrowth of proteolytic and asaccharolytic microbial species with iron-acquisition capacity, such as P, gingivalis, which can uncouple the nutritionally favorable inflammatory response from microbicidal responses [112]. Moreover, inflammation causes low redox potential that favors the development of anaerobic bacteria [110]. Consistently, a community-wide transcriptomic study on periodontitis-associated subgingival microbiome has indicated elevated expression of proteolysis-related genes, genes for peptide transport and acquisition of iron, as well as the genes associated with synthesis of lipopolysaccharides that would enhance the proinflammatory ability of the microbiota [113]. Those species that capitalize on the inflammatory spoils and expand their populations are termed ‘inflammophilic pathobionts’ [111]. Studies also indicated the selective overgrowth of pathobionts by addition of serum, hemoglobin or hemin to the in vitro formed oral multi-bacterial community [114]. Those pathobionts upregulate the expression of virulence-associated genes that encode proteases, hemolysins and proteins associated with hemin transport [114].

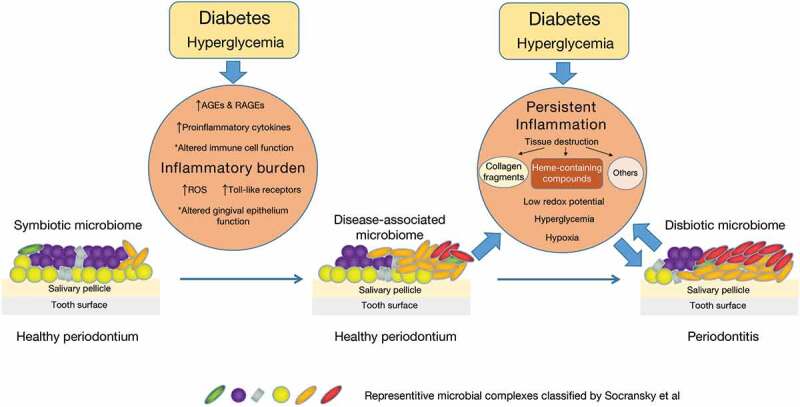

Together, all these findings support hypothesis that the selective pressure induced by the inflammatory environment drives the dysbiosis of the oral microbiome. Certain microorganisms (inflammophilic pathobionts) that thrive under inflammatory conditions stimulate greater inflammation, leading to reciprocal reinforcement between dysbiosis and inflammation. This vicious cyclic process persists and finally causes the clinical manifestations of periodontitis, e.g. attachment loss and periodontal pocket. As mentioned above, DM imposes a pre-existing inflammatory burden on periodontal tissues with increased levels of cytokines and ROS, altered immune cell function, accumulation of AGEs and upregulated expression of RAGEs and toll-like receptors. This pre-existing inflammatory burden and the increased level of glucose in gingival crevice fluid under DM foster the growth of inflammophilic pathobionts including the red complex, orange complex and the pathobionts that metabolize carbohydrates or their by-products, thus causing the oral microbiome to become a disease-associated community framework although the periodontium seems healthy (Figure 1). This dysbiotic microbiome initiates greater inflammation in turn, finally leading to the development of periodontitis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The plausible mechanism of DM altering oral microbiome.

Discussion

Since the first observation of microbes in dental plaque by Antony van Leeuwenhoek using his own microscope almost four hundred years ago, the role of oral microbial species has evolved from being simply considered as ‘passengers’ on the human host to one important factor that can modulate the health of their human host and induce diseases by working as a whole through inter-microbial synergism, signaling or antagonism, instead of by one or several species. The pathogenesis of periodontal disease has been explained by the ‘Polymicrobial Synergy and Dysbiosis (PSD)’ hypothesis, which suggests that the oral microbiome shifts from a healthy state to a diseased state in periodontal disease. Although the reasons for this shift are still not fully understood, ecological studies have shed light on this, indicating that environmental changes, such as pH, oxygen level and nutrition supply in specific oral sites, might drive this microbial alteration.

A mass of data has indicated that patients with DM or poorly glycemic control are more risky to periodontitis, which urges the studies on the oral microbiome in diabetics. The results revealed the alterations in the oral microbiome of subjects with DM or undesired glycemic control, although there were tiny differences in the specific microbial changes within different studies. Also, these findings support the notion that a dysbiotic oral microbiome is a plausible contributory factor in the pathogenesis of diabetes-induced periodontal disease. Since diabetic complications are frequently linked to increased inflammation, changes in the immune status of periodontal tissues in DM play an important role in the oral microbial shift in diabetics. Based on the studies of interactions between host and microbial community or certain microorganisms, this article discusses the mechanism of microbial change in DM that the selective pressure induced by inflammatory environment drives the dysbiosis of the oral microbiome, which in turn enhanced the inflammation. As the vicious cyclic process persists, periodontitis occurs.

There are also shortcomings about this review. First, this article is a narrative review. Although narrative review can be evidence-based, biased point of view may be possibly included in a narrative review. Nevertheless, the authors of this article hope that this review could serve as a valuable resource for interested readers to further explore the literature in periodontal microbial etiology and DM. Second, this article does not discuss the relationship between oral microbial shifts and the microbiome in other sites of digestive tract under DM. Since the oral cavity is a part of digestive tract, changes of intestinal microbiome in DM might have an influence on oral microbiome or vice versa. However, the relationships between intestinal microbiome and DM is complex, which may be beyond the focus of this review.

Future direction

While the collective analysis of those studies in this field has provided valuable insights, mechanistic and large longitudinal studies as well as intervention trials are still in need to confirm these results. This information will contribute to identification of microbial markers of disease activity, recurrence and responses to different types of treatment [115]. Furthermore, knowing the deleterious effects of the modulation of the periodontal microbiome by diabetes, it becomes important to investigate whether it is possible to reverse these dysbiotic ‘at-risk’ microbial shifts, returning it to hemostasis with therapeutic approaches [115]. There are several new directions that have potential to fill current gaps in this field. In addition to microbiome, other omics such as metabolomics, virome, mycobiome, proteomics and host genomics provide new methodologies to analyze the oral health/disease puzzles by incorporating them into bioinformatics models. As studies have demonstrated that microbial alterations in our body correlate with numerous diseases, manipulation of the microbial communities (via transplants, probiotics or targeted drug delivery) could be used to treat disease. In vitro and in vivo/preclinical studies have shown promise for applying probiotics in treating periodontal disease [116]. Moreover, with the development of large data sets that comprise microbial and clinical information, and the application of robust bioinformatics approaches, it is potentially to make really personalized dentistry in periodontology according to the metadata of individual subjects.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [81800938], National Natural Science Foundation of China [31971282], National Natural Science Foundation of China [82001063], Post-doctoral Program of Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing [cstc2020jcyj-bshX0108], Program for Team Building of Research Supervisor in Chongqing [dstd201903] and Program for Innovation Team Building at Institutions of Higher Education in Chongqing [CXTDG201602006].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- [1].Darveau RP. Periodontitis: a polymicrobial disruption of host homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010. Jul;8(7):481–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN.. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017. Jun 22;3: 17038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hajishengallis G. Immunomicrobial pathogenesis of periodontitis: keystones, pathobionts, and host response. Trends Immunol. 2014a. Jan;35(1):3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021. Jul;21(7):426–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].American Diabetes Association . 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021. Jan;44(Suppl 1):S15–s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Negrini TC, Carlos IZ, Duque C, et al. Interplay among the oral microbiome, oral cavity conditions, the host immune response, diabetes mellitus, and its associated-risk factors-an overview. Front Oral Health. 2021;2:697428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018Apr;138:271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Group IDFDA. Update of mortality attributable to diabetes for the IDF Diabetes Atlas: estimates for the year 2013. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015. Sep;109(3):461–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mellitus, D. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014. Jan;37(Suppl 1):S81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lalla E, Papapanou PN. Diabetes mellitus and periodontitis: a tale of two common interrelated diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011. Jun 28;7(12):738–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Preshaw PM, Alba AL, Herrera D, et al. Periodontitis and diabetes: a two-way relationship. Diabetologia. 2012. Jan;55(1):21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sanz M, Ceriello A, Buysschaert M, et al. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: consensus report and guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes by the International Diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2018. Feb;45(2):138–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chapple IL, Genco R. Diabetes and periodontal diseases: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J Periodontol. 2013. Apr;84(4 Suppl):S106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Graves DT, Corrêa JD, Silva TA. The oral microbiota is modified by systemic diseases. J Dent Res. 2019. Feb;98(2):148–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Verma D, Garg PK, Dubey AK. Insights into the human oral microbiome. Arch Microbiol. 2018. May;200(4):525–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kilian M, Chapple IL, Hannig M, et al. The oral microbiome - an update for oral healthcare professionals. Br Dent J. 2016. Nov 18;221(10):657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Curtis MA, Diaz PI, Van Dyke TE. The role of the microbiota in periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2020. Jun;83(1):14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dewhirst FE, Chen T, Izard J, et al. The human oral microbiome. J Bacteriol. 2010. Oct;192(19):5002–5017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gao L, Xu T, Huang G, et al. Oral microbiomes: more and more importance in oral cavity and whole body. Protein Cell. 2018. May;9(5):488–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Saini R, Saini S, Sharma S. Biofilm: a dental microbial infection. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2011. Jan;2(1):71–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bartold PM, Van Dyke TE. Periodontitis: a host-mediated disruption of microbial homeostasis. Unlearning learned concepts. Periodontol 2000. 2013. Jun;62(1):203–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Belda-Ferre P, Alcaraz LD, Cabrera-Rubio R, et al. The oral metagenome in health and disease. Isme J. 2012. Jan;6(1):46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Krishnan K, Chen T, Paster BJ. A practical guide to the oral microbiome and its relation to health and disease. Oral Dis. 2017. Apr;23(3):276–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015. Jan;15(1):30–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mason MR, Preshaw PM, Nagaraja HN, et al. The subgingival microbiome of clinically healthy current and never smokers. Isme J. 2015. Jan;9(1):268–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Petersen C, Round JL. Defining dysbiosis and its influence on host immunity and disease. Cell Microbiol. 2014. Jul;16(7):1024–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Radaic A, Kapila YL. The oralome and its dysbiosis: new insights into oral microbiome-host interactions. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:1335–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chen H, Jiang W. Application of high-throughput sequencing in understanding human oral microbiome related with health and disease. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gomar-Vercher S, Cabrera-Rubio R, Mira A, et al. Relationship of children’s salivary microbiota with their caries status: a pyrosequencing study. Clin Oral Investig. 2014. Dec;18(9):2087–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gross EL, Leys EJ, Gasparovich SR, et al. Bacterial 16S sequence analysis of severe caries in young permanent teeth. J Clin Microbiol. 2010. Nov;48(11):4121–4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Head D, Devine AD, Marsh PD. In silico modelling to differentiate the contribution of sugar frequency versus total amount in driving biofilm dysbiosis in dental caries. Sci Rep. 2017. Dec 12;7(1):17413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lamont RJ, Koo H, Hajishengallis G. The oral microbiota: dynamic communities and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018. Dec;16(12):745–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lu M, Xuan S, Wang Z. Oral microbiota: a new view of body health. Food Sci Hum Wellness. 2019. Mar 1;8(1):8–15. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ai D, Huang R, Wen J, et al. Integrated metagenomic data analysis demonstrates that a loss of diversity in oral microbiota is associated with periodontitis. BMC Genomics. 2017. Jan 25;18(Suppl 1):1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Almeida VSM, Azevedo J, Leal HF, et al. Bacterial diversity and prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes in the oral microbiome. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0239664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Altabtbaei K, Maney P, Ganesan SM, et al. Anna Karenina and the subgingival microbiome associated with periodontitis. Microbiome. 2021. Apr 30;9(1):97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Deng ZL, Szafrański SP, Jarek M, et al. Dysbiosis in chronic periodontitis: key microbial players and interactions with the human host. Sci Rep. 2017. Jun 16;7(1):3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Liu B, Faller LL, Klitgord N, et al. Deep sequencing of the oral microbiome reveals signatures of periodontal disease. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e37919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Abusleme L, Dupuy AK, Dutzan N, et al. The subgingival microbiome in health and periodontitis and its relationship with community biomass and inflammation. Isme j. 2013. May;7(5):1016–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Griffen AL, Beall CJ, Campbell JH, et al. Distinct and complex bacterial profiles in human periodontitis and health revealed by 16S pyrosequencing. Isme j. 2012. Jun;6(6):1176–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Scannapieco FA, Dongari-Bagtzoglou A. Dysbiosis revisited: understanding the role of the oral microbiome in the pathogenesis of gingivitis and periodontitis: a critical assessment. J Periodontol. 2021. Aug;92(8):1071–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Galimanas V, Hall MW, Singh N, et al. Bacterial community composition of chronic periodontitis and novel oral sampling sites for detecting disease indicators. Microbiome. 2014;2:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Schulz S, Porsch M, Grosse I, et al. Comparison of the oral microbiome of patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis and periodontitis-free subjects. Arch Oral Biol. 2019Mar;99:169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ge X, Rodriguez R, Trinh M, et al. Oral microbiome of deep and shallow dental pockets in chronic periodontitis. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Guglielmetti S, Taverniti V, Minuzzo M, et al. Oral bacteria as potential probiotics for the pharyngeal mucosa. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010. Jun;76(12):3948–3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].La Rosa GRM, Gattuso G, Pedullà E, et al. Association of oral dysbiosis with oral cancer development. Oncol Lett. 2020. Apr;19(4):3045–3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Vanhatalo A, Blackwell JR, L’Heureux JE, et al. Nitrate-responsive oral microbiome modulates nitric oxide homeostasis and blood pressure in humans. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018. Aug 20;124: 21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, et al. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998. Feb;25(2):134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bik EM, Long CD, Armitage GC, et al. Bacterial diversity in the oral cavity of 10 healthy individuals. Isme j. 2010. Aug;4(8):962–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012. Dec;27(6):409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Lamont RJ, Hajishengallis G. Polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis in inflammatory disease. Trends Mol Med. 2015. Mar;21(3):172–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Cugini C, Klepac-Ceraj V, Rackaityte E, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis: keeping the pathos out of the biont. J Oral Microbiol. 2013;5:19804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Dancing with the stars: how choreographed bacterial interactions dictate nososymbiocity and give rise to keystone pathogens, accessory pathogens, and pathobionts. Trends Microbiol. 2016. Jun;24(6):477–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Breaking bad: manipulation of the host response by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Eur J Immunol. 2014. Feb;44(2):328–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Shaikh HFM, Patil SH, Pangam TS, et al. Polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis: an overview. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2018. Mar-Apr;22(2):101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Chen B, Wang Z, Wang J, et al. The oral microbiome profile and biomarker in Chinese type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Endocrine. 2020. Jun;68(3):564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Long J, Cai Q, Steinwandel M, et al. Association of oral microbiome with type 2 diabetes risk. J Periodontal Res. 2017. Jun;52(3):636–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ogawa T, Honda-Ogawa M, Ikebe K, et al. Characterizations of oral microbiota in elderly nursing home residents with diabetes. J Oral Sci. 2017. Dec 27;59(4):549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Saeb ATM, Al-Rubeaan KA, Aldosary K, et al. Relative reduction of biological and phylogenetic diversity of the oral microbiota of diabetes and pre-diabetes patients. Microb Pathog. 2019Mar;128:215–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Yang Y, Liu S, Wang Y, et al. Changes of saliva microbiota in the onset and after the treatment of diabetes in patients with periodontitis. Aging (Albany NY). 2020. Jul 7;12(13):13090–13114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ganesan SM, Joshi V, Fellows M, et al. A tale of two risks: smoking, diabetes and the subgingival microbiome. ISME J. 2017. Sep;11(9):2075–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Shi B, Lux R, Klokkevold P, et al. The subgingival microbiome associated with periodontitis in type 2 diabetes mellitus. ISME J. 2020. Feb;14(2):519–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zhou M, Rong R, Munro D, et al. Investigation of the effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus on subgingival plaque microbiota by high-throughput 16S rDNA pyrosequencing. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Casarin RC, Barbagallo A, Meulman T, et al. Subgingival biodiversity in subjects with uncontrolled type-2 diabetes and chronic periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2013. Feb;48(1):30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Farina R, Severi M, Carrieri A, et al. Whole metagenomic shotgun sequencing of the subgingival microbiome of diabetics and non-diabetics with different periodontal conditions. Arch Oral Biol. 2019Aug;104:13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Balmasova IP, Olekhnovich EI, Klimina KM, et al. Drift of the subgingival periodontal microbiome during chronic periodontitis in Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Pathogens. 2021. Apr 22;10(5):504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Matsha TE, Prince Y, Davids S, et al. Oral microbiome signatures in diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 2020. Jun;99(6):658–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Longo PL, Dabdoub S, Kumar P, et al. Glycaemic status affects the subgingival microbiome of diabetic patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2018. Aug;45(8):932–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Xiao E, Mattos M, Vieira GHA, et al. Diabetes enhances IL-17 expression and alters the oral microbiome to increase its pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe. 2017. Jul 12;22(1):120–128.e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Donos N, Park JC, Vajgel A, et al. Description of the periodontal pocket in preclinical models: limitations and considerations. Periodontol 2000. 2018. Feb;76(1):16–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Oz HS, Puleo DA. Animal models for periodontal disease. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011. 2011;754857. DOI: 10.1155/2011/754857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Downes J, Dewhirst FE, Tanner ACR, et al. Description of Alloprevotella rava gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from the human oral cavity, and reclassification of Prevotella tannerae Moore et al. 1994 as Alloprevotella tannerae gen. nov., comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013. Apr;63(Pt 4):1214–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Willems A, Collins MD. 16S rRNA gene similarities indicate that Hallella seregens (Moore and Moore) and Mitsuokella dentalis (Haapsalo et al.) are genealogically highly related and are members of the genus Prevotella: emended description of the genus Prevotella (Shah and Collins) and description of Prevotella dentalis comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995. Oct;45(4):832–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Biddle AS, Black SJ, Blanchard JL. An in vitro model of the horse gut microbiome enables identification of lactate-utilizing bacteria that differentially respond to starch induction. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Morotomi M, Nagai F, Sakon H, et al. Dialister succinatiphilus sp. nov. and Barnesiella intestinihominis sp. nov., isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008. Dec;58(Pt 12):2716–2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Iwasaki M, Manz MC, Taylor GW, et al. Relations of serum ascorbic acid and α-tocopherol to periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 2012. Feb;91(2):167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Nishida M, Grossi SG, Dunford RG, et al. Dietary vitamin C and the risk for periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2000. Aug;71(8):1215–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Zhou C, Na L, Shan R, et al. Dietary vitamin C intake reduces the risk of Type 2 diabetes in Chinese adults: HOMA-IR and T-AOC as potential mediators. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Sakanaka A, Kuboniwa M, Hashino E, et al. Distinct signatures of dental plaque metabolic byproducts dictated by periodontal inflammatory status. Sci Rep. 2017. Feb 21;7: 42818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Gao Z, Yin J, Zhang J, et al. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes. 2009. Jul;58(7):1509–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Bastos AS, Graves DT, Loureiro AP, et al. Lipid peroxidation is associated with the severity of periodontal disease and local inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012. Aug;97(8):E1353–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Polak D, Shapira L. An update on the evidence for pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontitis and diabetes. J Clin Periodontol. 2018. Feb;45(2):150–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Graves DT, Ding Z, Yang Y. The impact of diabetes on periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2020. Feb;82(1):214–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Salvi GE, Beck JD, Offenbacher S. PGE2, IL-1 beta, and TNF-alpha responses in diabetics as modifiers of periodontal disease expression. Ann Periodontol. 1998. Jul;3(1):40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Acharya AB, Thakur S, Muddapur MV, et al. Cytokine ratios in chronic periodontitis and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2017. Oct-Dec;11(4):277–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Van Dyke TE. Pro-resolving mediators in the regulation of periodontal disease. Mol Aspects Med. 2017Dec;58:21–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Wang M, Chen F, Wang J, et al. Th17 and Treg lymphocytes in obesity and Type 2 diabetic patients. Clin Immunol. 2018Dec;197:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Domingueti CP, Dusse LM, Carvalho M, et al. Diabetes mellitus: the linkage between oxidative stress, inflammation, hypercoagulability and vascular complications. J Diabetes Complications. 2016. May-Jun;30(4):738–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Sima C, Rhourida K, Van Dyke TE, et al. Type 1 diabetes predisposes to enhanced gingival leukocyte margination and macromolecule extravasation in vivo. J Periodontal Res. 2010. Dec;45(6):748–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Sonnenschein SK, Meyle J. Local inflammatory reactions in patients with diabetes and periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2015. Oct;69(1):221–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Sreedhar R, Arumugam S, Thandavarayan RA, et al. Role of 14-3-3η protein on cardiac fatty acid metabolism and macrophage polarization after high fat diet induced type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2017Jul;88:92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Xu F, Zhang C, Graves DT. Abnormal cell responses and role of TNF-α in impaired diabetic wound healing. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:754802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005. Jun;54(6):1615–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Brownlee M, Vlassara H, Cerami A. Nonenzymatic glycosylation and the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. Ann Intern Med. 1984. Oct;101(4):527–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Lapolla A, Brioschi M, Banfi C, et al. Nonenzymatically glycated lipoprotein ApoA-I in plasma of diabetic and nephropathic patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008Apr;1126:295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Chilelli NC, Burlina S, Lapolla A. AGEs, rather than hyperglycemia, are responsible for microvascular complications in diabetes: a “glycoxidation-centric” point of view. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013. Oct;23(10):913–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Katz J, Bhattacharyya I, Farkhondeh-Kish F, et al. Expression of the receptor of advanced glycation end products in gingival tissues of Type 2 diabetes patients with chronic periodontal disease: a study utilizing immunohistochemistry and RT-PCR. J Clin Periodontol. 2005. Jan;32(1):40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Singh VP, Bali A, Singh N, et al. Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014. Feb;18(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Sorci G, Riuzzi F, Giambanco I, et al. RAGE in tissue homeostasis, repair and regeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013. Jan;1833(1):101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Lalla E, Lamster IB, Feit M, et al. Blockade of RAGE suppresses periodontitis-associated bone loss in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest. 2000. Apr;105(8):1117–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Susztak K, Raff AC, Schiffer M, et al. Glucose-induced reactive oxygen species cause apoptosis of podocytes and podocyte depletion at the onset of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2006. Jan;55(1):225–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Coughlan MT, Sharma K. Challenging the dogma of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species overproduction in diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2016. Aug;90(2):272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Shaker O, Ghallab NA, Hamdy E, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in gingival tissues of chronic periodontitis with and without diabetes: immunohistochemistry and RT-PCR study. Arch Oral Biol. 2013. Oct;58(10):1397–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Promsudthi A, Poomsawat S, Limsricharoen W. The role of Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 in gingival tissues of chronic periodontitis subjects with type 2 diabetes. J Periodontal Res. 2014. Jun;49(3):346–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Jiang SY, Wei CC, Shang TT, et al. High glucose induces inflammatory cytokine through protein kinase C-induced toll-like receptor 2 pathway in gingival fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012. Oct 26;427(3):666–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Groeger SE, Meyle J. Epithelial barrier and oral bacterial infection. Periodontol 2000. 2015. Oct;69(1):46–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Hu SC, Lan CE. High-glucose environment disturbs the physiologic functions of keratinocytes: focusing on diabetic wound healing. J Dermatol Sci. 2016. Nov;84(2):121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Silva JA, Lorencini M, Reis JR, et al. The influence of type I diabetes mellitus in periodontal disease induced changes of the gingival epithelium and connective tissue. Tissue Cell. 2008. Aug;40(4):283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Marsh PD, Zaura E. Dental biofilm: ecological interactions in health and disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2017. Mar;44(Suppl 18):S12–s22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Rosier BT, Marsh PD, Mira A. Resilience of the oral microbiota in health: mechanisms that prevent dysbiosis. J Dent Res. 2018. Apr;97(4):371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Hajishengallis G. The inflammophilic character of the periodontitis-associated microbiota. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2014b. Dec;29(6):248–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Maekawa T, Krauss JL, Abe T, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis manipulates complement and TLR signaling to uncouple bacterial clearance from inflammation and promote dysbiosis. Cell Host Microbe. 2014. Jun 11;15(6):768–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Duran-Pinedo AE, Chen T, Teles R, et al. Community-wide transcriptome of the oral microbiome in subjects with and without periodontitis. Isme j. 2014. Aug;8(8):1659–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Herrero ER, Fernandes S, Verspecht T, et al. Dysbiotic biofilms deregulate the periodontal inflammatory response. J Dent Res. 2018. May;97(5):547–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Teles R, Sakellari D, Teles F, et al. Relationships among gingival crevicular fluid biomarkers, clinical parameters of periodontal disease, and the subgingival microbiota. J Periodontol. 2010. Jan;81(1):89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Nguyen T, Brody H, Radaic A, et al. Probiotics for periodontal health-Current molecular findings. Periodontol 2000. 2021. Oct;87(1):254–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]