SUMMARY

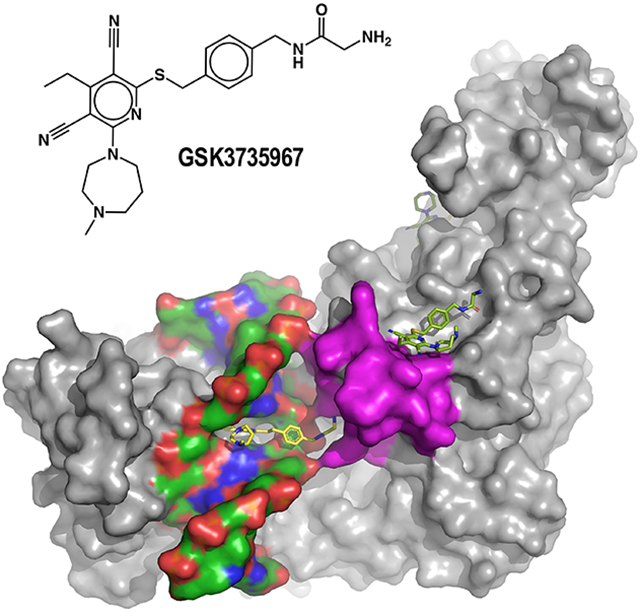

DNMT1 maintains the parental DNA methylation pattern on newly replicated, hemimethylated DNA. Failure of this maintenance process causes aberrant DNA methylation that affects transcription and contributes to the development and progression of cancers such as acute myeloid leukemia. Here, we structurally characterized a set of newly discovered DNMT1-selective, reversible, non-nucleoside inhibitors that bear a core 3,5-dicyanopyridine moiety, as exemplified by GSK3735967, to better understand their mechanism of inhibition. All of the dicyanopydridine containing inhibitors examined intercalate into the hemi-methylated DNA between two CpG base pairs through the DNA minor groove, resulting in conformational movement of the DNMT1 active-site loop. In addition, GSK3735967 introduces two new binding sites where it interacts with and stabilizes the displaced DNMT1 active-site loop and it occupies an open aromatic cage where tri-methylated histone H4 lysine 20 is expected to bind. Our work represents a substantial step in generating potent, selective and non-nucleoside inhibitors of DNMT1.

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Horton et al. show that dicyanopyridine containing, non-nucleoside inhibitors act specifically on DNMT1-bound hemi-methylated DNA. The inhibitors share a 3,5-dicyanopyridine core but vary in their chemical architecture at C2 and C6 of the pyridine ring. The dicyanopydridine moiety competes with DNMT1-active site loop for intercalation from DNA minor groove.

INTRODUCTION

Dynamic, epigenetic alterations can have profound impact on chromatin structure and gene expression, with implications for inheritance, evolution, and human health and diseases, including cancer, and their reversibility makes them attractive therapeutic targets (Allis et al., 2015; Cavalli and Heard, 2019; Kaliman, 2019; Sapienza and Issa, 2016). Methylation is one of the most studied epigenetic modifications in cells. Methylation can occur on DNA, RNA and proteins, and the development of cancer therapeutics targeting S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM)-dependent methylation has been widely pursued. Consequently, drug development targeting methylation is proceeding rapidly, and several DNA hypomethylating agents have been FDA approved for the treatment of specific cancers (Jarrold and Davies, 2019; Siklos and Kubicek, 2021; Yankova et al., 2021; Yoo and Jones, 2006).

In mammals, there are three major DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), belonging to two structurally and functionally distinct families, that act primarily at CpG dinucleotides. DNMT3a and DNMT3b establish the initial cytosine methylation pattern de novo, whereas DNMT1 faithfully maintains this pattern on newly replicated DNA. The general reaction pathway for DNMTs that act on cytosine involves the transfer of the labile methyl group from SAM to the C5 position of the cytosine ring, proceeding through a covalent intermediate at position C6 via a nucleophilic cysteine [reviewed in (Cheng and Roberts, 2001; Roberts and Cheng, 1998) and references therein] (Figure S1A). Historically, DNA hypomethylation in humans has relied on the nucleoside cytosine analogs azacytidine and 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (decitabine) (Flotho et al., 2009; Jones and Taylor, 1980; Yoo and Jones, 2006). These analogs are FDA approved as DNMT-inhibiting prodrugs (Vidaza/Onureg, Dacogen and Inqovi) that after metabolic conversion to their triphosphate form, are incorporated into RNA or DNA, where they trap DNMTs through the formation of an irreversible suicide complex (Ganesan et al., 2019; Santi et al., 1984; Sheikhnejad et al., 1999). In 5-azacytidine, the substitution of C5 with a nitrogen atom renders covalent attack by DNMT irreversible. The irreversible covalent attachment of a DNMT to its DNA recognition sequences presumably leads to the formation of persistent, aberrant nucleoprotein complexes throughout the genome. The subsequent repair of such DNA damaging nucleoprotein adducts have the potential to be error-prone and contribute to the cellular toxicity of these drugs.

Despite their potential, the dose-limiting toxicity of and limited patient tolerance for nucleoside cytosine analog prodrugs as well as their ineffectiveness in treating solid tumors (Sato et al., 2017; Stomper et al., 2021) has led to a persistent search for non-nucleoside DNMT inhibitors. This search has led to the discoveries of RG-108 (Brueckner et al., 2005), the quinoline-based SGI-1027 (Datta et al., 2009) and its analogs MC3343 and MC3353 (Gros et al., 2015; Manara et al., 2018; Valente et al., 2014; Zwergel et al., 2019), quinazoline derivatives (Rotili et al., 2014) and quinazoline–quinoline linked derivatives (Halby et al., 2017), as well as other small-molecule compounds (Huang et al., 2021). However, none of these inhibitors are specific for DNMT1 with a clear translation from in vitro to in vivo activity.

We recently described a new class of reversible, DNMT1-selective inhibitors containing a dicyanopyridine moiety (Pappalardi et al., 2021). These inhibitors, including GSK3685032, are selective for DNMT1 over more than 300 protein kinases and 30 other methyltransferases (MTases), including DNMT3a and 3b (Pappalardi et al., 2021). Most importantly, GSK3685032 inhibits cancer cell growth in vitro and is superior to decitabine (Dacogen) for tumor regression and survival in mouse models of acute myeloid leukemia (Pappalardi et al., 2021).

Within the short time following their discovery, this new class of dicyanopyridine DNMT1-selective inhibitors has shown promising therapeutic potential. For example, in a transgenic mouse model of sickle cell disease, orally administered GSK3482364 was well tolerated and led to increases in both fetal hemoglobin levels and the percentage of erythrocytes expressing fetal hemoglobin (Gilmartin et al., 2021). GSK3484862 (the R-enantiomer of the GSK3482364 racemic mixture) inhibits Dnmt1 in murine pre-implantation Dnmt3a/3b knockout embryos (Haggerty et al., 2021), and results in demethylation in mouse embryonic stem cells, in a level similar to that observed with Dnmt1 knockouts, with minimal non-specific toxicity (Portilho et al., 2021).

Here, we characterize several additional dicyanopyridine-containing derivatives which bind DNMT1-DNA complexes by intercalating into the hemimethylated DNA between two CpG base pairs in the DNA minor groove (site 1), causing displacement of the active-site loop. Additional focus will be given to GSK3735967 which introduces two new binding sites where it interacts with and stabilizes the displaced active-site loop of DNMT1 (site 2) and occupies an open aromatic cage where tri-methylated histone H4 lysine 20 (H4K20me3) is known to bind (site 3).

RESULTS

Use of zebularine to form a stable DNMT1-DNA complex

During our medicinal chemistry optimization, we found that a dicyanopyridine-based series of DNMT1-selective inhibitors bound preferentially and reversibly to DNMT1 in the presence of a hemimethylated CpG oligonucleotide, but not an unmethylated DNA oligonucleotide that could serve as a DNMT3 substrate (Pappalardi et al., 2021). This observation indicates that these inhibitors have a mechanism of action distinct from those of traditional nucleoside analogs.

In order to better understand how the dicyanopyridine-based inhibitors block DNMT1 activity, we took a crystallographic approach. Notably, these dicyanopyridine-based compounds are chemically stable, but bind neither DNMT1 alone nor DNA nonspecifically. It was previously reported that replacing the cytosine targeted with a 5-fluorocytosine resulted in an irreversible DNMT1-DNA complex (Song et al., 2012). This fluorine renders the DNMT covalent attack irreversible following the methyl transfer step because abstraction of F (as opposed to H) cannot be achieved. Nonetheless, using this approach, we were unable to identify an inhibitor that binds to this irreversible DNMT1-DNA complex.

To obtain a stable, potentially reversible, DNMT1-DNA complex that would permit inhibitor binding and activity prior to the methyl transfer step, but that was also sufficiently stable for crystallization, we considered incorporating other cytidine analogues such as 4'-thio-2'-deoxycytidine (Kumar et al., 1997) and 2-H-pyrimidinone, commonly called zebularine (Zhou et al., 2002). An earlier study with bacterial MTases indicated that zebularine-substituted DNA forms high-affinity complexes with MTases in which the catalytic Cys has been replaced by either Ser or Thr (Hurd et al., 1999). Notably, in contrast to 5-fluorocytosine and 5-azacytidine-substituted DNA (Gabbara and Bhagwat, 1995; Klimasauskas et al., 1994), zebularine-modified DNA cannot be methylated by the MTases MspI and HhaI, even after prolonged exposure to SAM (Zhou et al., 2002). We found that DNMT1, like MspI and HhaI, can bind to but cannot methylate zebularine-substituted DNA, even in the presence of bound SAM (Figure S1B-D).

Zebularine has been previously substituted for the target cytidines that bind in the active-sites of the MTases HhaI (Zhou et al., 2002) and DNMT3a (Zhang et al., 2018). For the HhaI study, a 2’-deoxy form of zebularine was specifically synthesized and is present in the crystal structure (Taylor et al., 1993; Zhou et al., 2002) (PDB 1M0E; Figure S1E-F), for DNMT3a the 2’-oxy form was observed in the crystal structure (PDB 5YX2; Figure S1G-H), despite the modified nucleoside being described as 2′-deoxyzebularine (Zhang et al., 2018). Hence, we used a commercially available zebularine phosphoramidite from Glen Research that contains a 2’-OH, as in RNA, for DNA synthesis.

We crystallized human DNMT1 (residues 729-1600) in complex with a hemimethylated, double stranded oligonucleotide containing zebularine in place of the target cytidine with a 12-base-pair duplex, in the presence of either SAM (PDB 7SFG) or the cofactor analogue S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (SAH; PDB 6X91). In the DNMT1 structures, like the HhaI and DNMT3a structures, the 2′-oxyzebularine was flipped out and was bound in the active site, where the catalytic nucleophile Cys1226 formed a covalent-like bond (1.8 Å) with the ring C6 atom (Figure S1D and S1J). In addition, the main chain carbonyl oxygen atom of Gly1577 formed a hydrogen bond with the 2’-OH group. The corresponding glycine is conserved in both HhaI (Gly303) and DNMT3a (Gly890) (Figure S1). Together, the structures of these zebularine-bound MTase complexes reinforced two previous findings. First, human and bacterial DNA MTases bind DNA substrates containing a mismatch at the target base within the recognition sequences (O'Gara et al., 1998; Smith, 1994) (e.g., G:C with 3 H-bonds vs. G:Z with 2 H-bonds). Second, the lack of selectivity toward the target nucleoside extends to the ribose moiety. Dnmt2, a tRNA cytosine MTase, methylates 2’-deoxycytidine (as in DNA) in the context of a tRNA (Kaiser et al., 2017), whereas DNMT3a and DNMT1 accommodate 2′-oxyzebularine (as in RNA) in the context of DNA.

Trapping the DNMT1-DNA-inhibitor complex in the presence of zebularine-substituted DNA

The high-affinity complexes with zebularine-containing DNA allowed us to chromatographically copurify DNMT1 and DNA in an equal molar ratio. To examine this complex in the presence of bound inhibitor, we initially attempted to soak inhibitors into the pre-formed complex crystals but failed to identify bound inhibitor (GSK3543105) but observed that the resolution of the complex structure was decreased, falling to 3.4 Å in the presence of inhibitor from 2.2 Å in the absence of inhibitor, indicating the inhibitor potentially interferes with the complex in the crystal lattice. Next, we mixed the inhibitor with the pre-formed DNMT1-DNA-SAH ternary complex and incubated the mixture for an hour prior to co-crystallization. This mixture crystallized readily under the same conditions we used before, and the resulting crystals were isomorphous with the crystals of the ternary complex without inhibitor. The difference electron density maps unambiguously identified bound inhibitor. Next, we examined the interactions between a set of six inhibitor compounds with the pre-formed DNMT1-DNA-SAH complexes, as determined by crystal structures with resolutions ranging from 1.79-2.65 Å (Figure 1A-1B and Table 1). The inhibitors all share a 3,5-dicyanopyridine core but vary in their chemical architecture at positions C2 and C6 of the pyridine ring. The substitution at C2 links to either a seven-membered diazepane (GSK3543105 and GSK3735967) or a six-membered piperidine (GSK3852279 and GSK3830334). The functionalization at C6 links to a phenylacetamide moiety or similar thio-ester derivative.

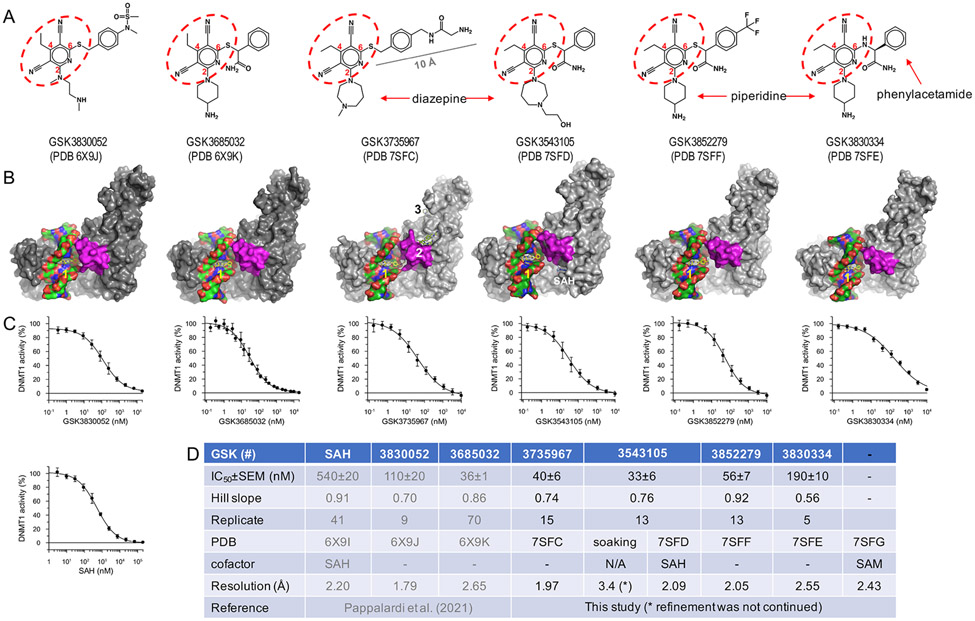

Figure 1. Summary of the six GSK compounds used in this study.

(A) The chemical structures with the common dicyanopyridine moiety circled in red. (B) Surface representations of six inhibitor-bound DNMT1-DNA structures with the inhibitor shown in yellow (site 1) and the active-site loop shown in magenta. Note that GSK3735967 binds to three distinct sites (labeled as 1-3) and that SAH remains bound in the presence of GSK3543105. (C) Representative compound dose-response curves (average ± s.e.m., N≥5) for full-length DNMT1 using a 40-mer hemi-methylated DNA duplex in a radioactive SPA assay. (D) Summary of inhibitory (IC50 and Hill slope) measured by SPA assay and structural information (PDB accession numbers and corresponding resolutions) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of X-ray data collection at wavelength=1Å (APS-SERCAT-22ID) and refinement statistics in space group C2

| Inhibitor | GSK3735967 | GSK3543105 | GSK3830334 | GSK3852279 | - |

| Date of data collection | 10/2019 | 10/2018 | 06/2019 | 04/2019 | 12/2018 |

| cofactor | - | SAH | - | - | SAM |

| PDB Code | 7SFC | 7SFD | 7SFE | 7SFF | 7SFG |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | 161.73, 78.90, 117.34 | 161.60, 77.42, 116.51 | 161.97, 78.49, 117.56 | 161.72, 78.24, 117.06 | 161.78, 77.48, 116.71 |

| α=γ=90°, β (°) | 125.6 | 125.8 | 125.8 | 125.9 | 125.7 |

| Resolution (Å) | 35.35-1.97 (2.06-1.97) | 41.81-2.09 (2.16-2.09) | 42.14-2.55 (2.64-2.55) | 38.75-2.05 (2.12-2.05) | 41.85 -2.43 (2.54-2.43) |

| a Rmerge | 0.139 (1.469) | 0.117 (1.199) | 0.142 (0.845) | 0.084 (0.558) | 0.112 (0.660) |

| Rpim | 0.060 (0.758) | 0.047 (0.629) | 0.064 (0.492) | 0.039 (0.395) | 0.066 (0.464) |

| CC1/2, CC | (0.442, 0.783) | (0.494, 0.813) | (0.429, 0.775) | (0.591, 0.862) | (0.661, 0.892) |

| b <I/σI> | 15.8 (1.6) | 17.6 (1.9) | 11.1 (1.3) | 19.4 (1.9) | 12.4 (2.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.7 (98.2) | 97.7 (96.3) | 98.0 (91.7) | 97.2 (86.7) | 99.5 (98.5) |

| Redundancy | 6.1 (4.4) | 6.7 (3.9) | 5.5 (3.4) | 5.0 (2.5) | 3.7 (2.8) |

| Observed reflections | 495,816 | 452,711 | 208,061 | 358,453 | 159,520 |

| Unique reflections | 80,886 (8,006) | 67,405 (6,563) | 38,168 (3,527) | 71,672 (6,373) | 43,229 (4,231) |

| Refinement | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 1.97 | 2.09 | 2.55 | 2.05 | 2.43 |

| No. reflections | 80,823 | 67,381 | 38,148 | 71,573 | 43,221 |

| c Rwork/d Rfree | 0.171 / 0.204 | 0.197 / 0.223 | 0.187 / 0.239 | 0.181 / 0.219 | 0.176 / 0.218 |

| No. Atoms | |||||

| Protein | 6529 | 6440 | 6532 | 6518 | 6297 |

| DNA | 487 | 487 | 487 | 487 | 487 |

| SAH/SAM | - | 26 | - | - | 27 |

| Inhibitor | 102 | 33 | 30 | 34 | - |

| Zn | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Solvent | 581 | 277 | 264 | 383 | 317 |

| B Factors (Å2) | |||||

| Protein | 42.1 | 57.1 | 67.2 | 51.2 | 54.4 |

| DNA | 97.7 | 111.5 | 120.5 | 104.8 | 82.0 |

| SAH/SAM | - | 34.5 | - | - | 39.2 |

| Inhibitor | 72.4 | 79.4 | 79.5 | 85.7 | - |

| Zn | 42.3 | 65.7 | 69.6 | 54.8 | 70.6 |

| Solvent | 46.8 | 51.4 | 54.9 | 48.7 | 45.4 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

Values in parenthesis correspond to highest resolution shell.

Rmerge = Σ ∣ I - <I>∣ /Σ I, where I is the observed intensity and <I> is the averaged intensity from multiple observations.

<I/σI> = averaged ratio of the intensity (I) to the error of the intensity (σI).

Rwork = Σ ∣ Fobs - Fcal ∣ /Σ ∣ Fobs ∣, where Fobs and Fcal are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

Rfree was calculated using a randomly chosen subset (5%) of the reflections not used in refinement.

To see if there was any link between potency and the changes in chemical architecture at positions C2 and C6 of the pyridine ring, the compounds were examined for their ability to inhibit the enzymatic activity of DNMT1 in a radioactive scintillation proximity assay (SPA). In contrast to the crystallization system, the activity assay utilized full-length DNMT1 and a longer 40-mer hemimethylated DNA duplex. Compound potency, measured as the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), lies in a narrow range of ~30-60 nM for GSK3843105, GSK3685032, GSK3735967 and GSK3852279, whereas GSK3830052 and GSK3830334 have reduced potency by ~2-3 or ~3-6 fold, respectively (Figure 1C-1D). For the remainder of the study, we will primarily focus on GSK3735967, while highlighting differences among the compounds. Overall, we identified three sites of inhibitor binding, which we will refer to as sites 1, 2, and 3 (Figure 1B), that will each be discussed in detail below.

General features of inhibitor-bound DNMT1-DNA complexes at site 1

We made three major observations common to all six inhibitor-bound DNMT1-DNA complexes, which are described in detail below. Briefly, these observations are: 1) intercalation of the dicyanopyridine moiety into the DNA between the DNMT1-targeted hemi-methylated CpG dinucleotides; 2) an open conformation in the DNMT1 active-site loop in the presence of DNA; and 3) displacement of the active-site loop that disrupts the interaction between the C6 carbon of the extrahelical zebularine and the sulfur atom of Cys1226 in the active site and allows zebularine to return to intrahelical.

First, the dicyanopyridine moiety intercalates into the DNA between the two C:G base pairs (i.e., 5mC:G and G:Zebularine) in the minor groove, mainly through stacking interactions (Figure 2A-C). The inhibitor penetrates deeply into the DNA and interacts with the side chains of Lys1535 and His1507 located on the major groove side (Figure 2D). To further highlight the importance of His1507, mutation of His1507 to alanine (H1507A) or tyrosine (H1507Y) revealed reduced sensitivity to the dicyanopyridine compounds (Pappalardi et al., 2021). Although a planar moiety of an intercalator molecule inserting between adjacent bases is a well-known process for drug intercalation into DNA or RNA (Figure S2) (Satange et al., 2019; Satpathi et al., 2021) (reviewed in (Soni et al., 2017) and references therein), the rare observation is that here, the insertion of dicyanopyridine-based GSK compounds takes place specifically between the DNMT1-bound hemi-methylated CpG dinucleotides.

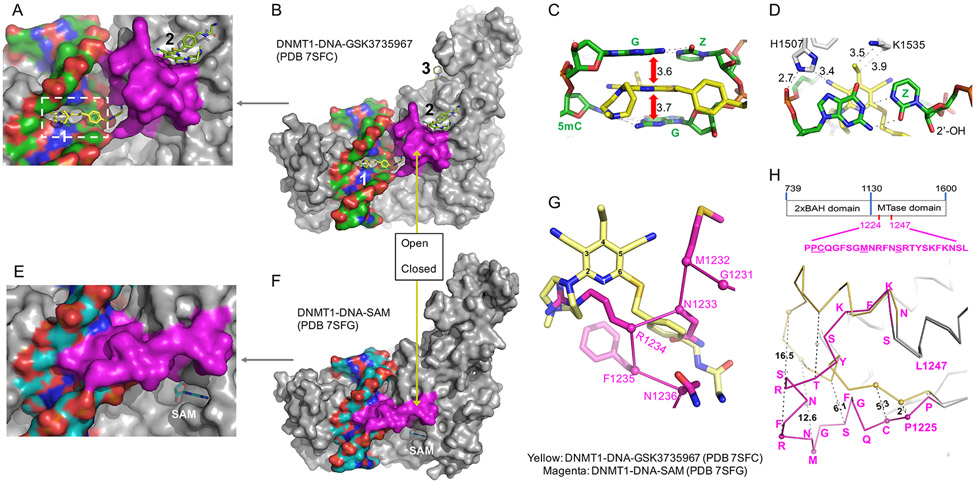

Figure 2. General features of the DNMT1-DNA-GSK3735967 complex.

(A-B) The inhibitor penetrates into DNA from the minor groove. (C) The inhibitor stacks in between two DNA base pairs. (D) Zebularine remains intrahelical and forms two hydrogen bonds with the opposite guanine. (E-F) DNMT1-DNA-SAM with zebularine in place of target cytidine. (G) Superimposition of the inhibitor (yellow) and the active-site loop (magenta) in the native complex. (H) Conformational changes of the active-site loop (residues 1224-1247) in the inhibitor-bound open conformation (yellow) and closed conformation (magenta). The sequence of the active-site loop is shown in the context of the construct used in the study.

Second, the 23-residue DNMT1 active-site loop (residues 1225-1247) is in an open conformation (Comparing Figure 2A and 2E or 2B and 2F). From a structural perspective of the methylation reaction pathway, the active-site loop initially adopts an open conformation in the absence of substrate DNA (Figure S3A). Upon DNA binding, the corresponding loop intercalates into the DNA minor groove and flips the target cytosine out and into the active-site pocket (Figure S3B). Once in the active site, the Cys1226 nucleophile approaches the C6 atom, and the methyl-donor SAM approaches the C5 atom from the opposite face of the cytosine ring, allowing for catalysis (Figure S1A). After methylation at the C5 position, the subsequent elimination of the C5 proton would release the covalent intermediate between the Cys and C6 atom, thus releasing the reaction products (methylated DNA and SAH) prior to the next round of catalysis. Here, the inhibitor appears to compete or displace the active-site loop from the DNA minor groove, thus restoring the open conformation without releasing the DNA (Figure S3C). Superimposition of the complex structures, in the absence and presence of inhibitor, suggests that the inhibitor occupies the space of four residues (Asn1233-Asn1236) within the active-site loop of the closed conformation (Figure 2G). The conformational change within the active-site loop affects the binding of the target nucleoside and cofactor.

Third, the target zebularine is intrahelical and forms two hydrogen bonds (the third hydrogen bond normally present in a C:G pair is lost due to lack of the N4 amino group in zebularine) with the paired guanine (Figure 2D). It appears that the displacement of the active-site loop, which includes Cys1226, can disrupt and reverse the strong interaction between the C6 carbon of the extrahelical zebularine and the sulfur atom of Cys1226 (Figure S1D). This observation agrees well with the previous finding that zebularine-substituted DNA forms high-affinity complexes with MTases in which the catalytic Cys has been replaced with either Ser or Thr (Hurd et al., 1999).

GSK3735967 interacts with the active-site loop at site 2

Our observations at site 1 encompass only one snapshot of the complex captured by our co-crystallization of a stable and high-affinity protein-DNA complex. Unexpectedly, we observed two additional GSK3735967 binding sites on DNMT1, designated sites 2 and 3 in Figure 3A. The compounds bound at the three sites have similar crystallographic thermal B-factor, 66 Å2 (site 1), 56 Å2 (site 2) and 60 Å2 (site 3), indicating a similar occupancy at the three sites. Site 2 is formed, in part by the displacement of the DNMT1 active-site loop in response to the binding of inhibitor to site 1. We note that of the six compounds examined, GSK3735967 has the longest substituent from C6 of the dicyanopyridine moiety (Figure 1A).

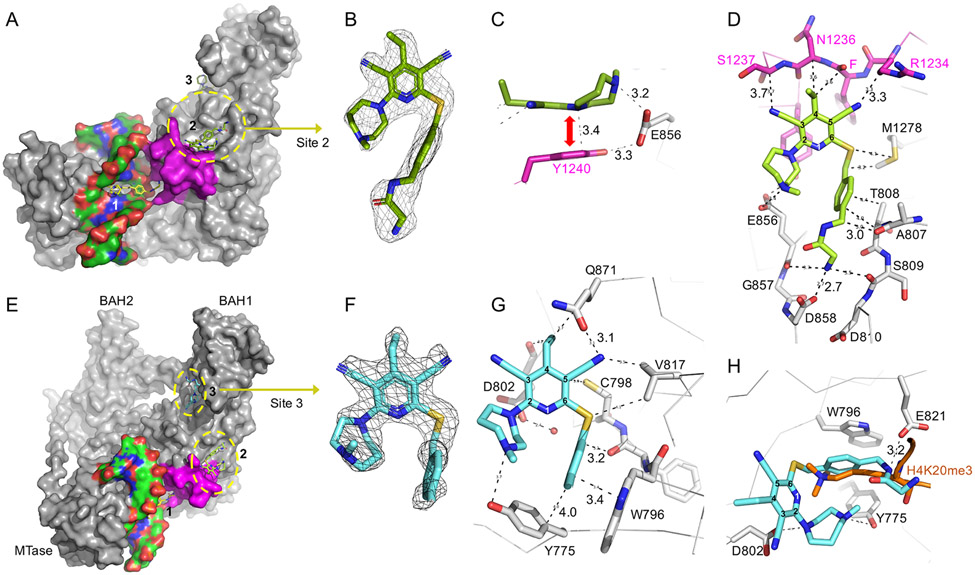

Figure 3. Two additional binding sites unique to GSK3735967.

(A) Binding site 2 is created, in part, by the displaced active-site loop (in magenta). (B) Omit electron density for the inhibitor bound at site 2 contoured at 5σ above mean. (C) The dicyanopyridine moiety of the inhibitor stacks with Tyr1240. (D) Detailed interaction of GSK3735967 at site 2 involving the active-site loop residues (magenta) next to an acidic environment (Glu856, Glu858 and Asp810). (E) Binding site 3 is located in the BAH1 domain. (F) Omit electron density for the inhibitor bound at site 3 contoured at 5σ above mean. (G) Detailed interaction of GSK3735967 at site 3 involving a half aromatic cage (Tyr775 and Trp796). (H) Superimposition of GSK3735967 bound at site 3 and a peptide of histone H4 lysine 20 trimethylation derived from the structure of the bovine Dnmt1 BAH domain (PDB 7LMK).

At site 2, the bound inhibitor (Figure 3B) interacts with DNMT1 through aromatic, electrostatic, and van der Waals contacts. The plate-like structure of 4-ethylpyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile moiety of the inhibitor is stacked against Tyr1240, an aromatic residue of the active-site loop (Figure 3C), rather than being sandwiched between two DNA base pairs, as seen at site 1 (Figure 2C). The nitrogen of the seven-membered diazepane makes a weak hydrogen bond with Glu856, which bridges the inhibitor and Tyr1240 (Figure 3C). The two symmetric acetonitrile groups form van der Waals contacts with the main chain atoms of the active-site loop from residues Arg1234 to Ser1237 (Figure 3D). We note that Arg1234 undergoes the largest movement during the transition between the DNA-bound closed active site conformation and the inhibitor-induced open conformation (Figure 2H). Further Arg1234 is the residue whose position in the closed conformation is replaced by the inhibitor at site 1 (Figure 2G). The extended structure of the GSK3735967 phenylacetamide derivative makes extensive van der Waals contacts with the side chains of Met1278 and Thr808 and the main chain atoms of Ala807 and Ser809. The terminal amino group of the phenylacetamide derivative lies in the acidic carboxylate group of Asp858 and the main-chain carbonyl oxygen atoms of Gly857 and Ser809 (Figure 3D). The shorter functional groups of the other five compounds are likely unable to interact with Asp858.

GSK3735967 binds the open aromatic cage of H4K20me3 at site 3

The third inhibitor binding site is located on the surface of one of two DNMT1 bromo-adjacent homology domains, the BAH1 domain, a member of the origin recognition complex subunit 1 (ORC1) class of BAH domains (Figure 3E). The inhibitor molecule binding at site 3 (Figure 3F) displays a distinct conformation in the phenylacetamide functionality. The driving force of inhibitor binding at site 3 is the phenyl ring that forms a face-to-face stacking interaction with Trp796 and a face-to-edge interaction with Tyr775 (Figure 3G). Interactions with the seven-membered diazepane involve a negatively charged Asp802 and the side-chain hydroxyl oxygen of Tyr775. The planar 4-ethylpyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile moiety forms van der Walls contacts with Val817 and Cys798 and weak hydrogen bonds with Gln871 and the main-chain carbonyl oxygen atom of Phe797.

Most interestingly, the half aromatic cage (Tyr775 and Trp796) at site 3, together with two negatively charged Asp802 and Glu821 residues, is the site where trimethylated H4K20 (H4K20me3) is expected to bind (Figure 3H). A previous study showed that the BAH domain of ORC1 recognizes H4K20 dimethylation (H4K20me2), enabling regulation of ORC1-chromatin association and DNA replication initiation (Kuo et al., 2012). More recently, the first BAH domain of DNMT1 was identified as a reader for H4K20me3, possibly reinforcing DNA methylation and histone modification at LINE-1 retrotransposons (Ren et al., 2021). Superimposition of the GSK3 73 5967-bound BAH1 domain of human DNMT1 with that of H4K20me3-bound bovine BAH1 revealed that the inhibitor’s phenylacetamide functionality overlaps with the side chain of H4K20me3 and the terminal group of the substituent overlaps with the main-chain atoms of the histone peptide in the bovine structure, confirming that the inhibitor occupies the space normally occupied by H4K20me3. Our finding that GSK3735967 binds at the H4K20me3 cage identifies an additional target for designing small molecule inhibitors that disrupt DNMT1-mediated crosstalk between H4K20me3 and DNA methylation - two important heterochromatin-enriched epigenetic marks that frequently cooperate to silence repetitive elements within the mammalian genome.

A quaternary complex of DNMT1-DNA-SAH-GSK3543105

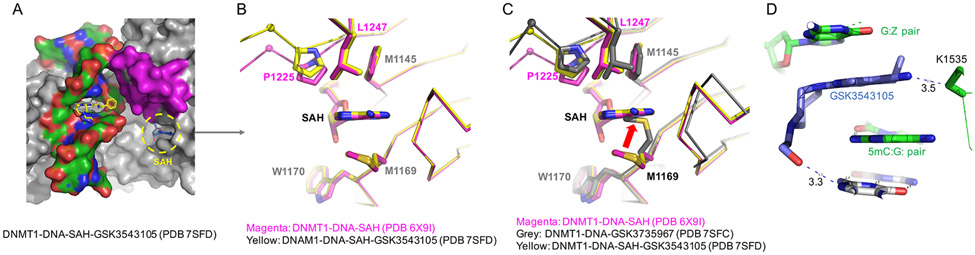

As noted above, we prepared the inhibitor bound complex with a preformed DNMT1-DNA-SAH in the co-crystallization mixture. The cofactor was diffused out in all of the inhibitor-bound complexes except those with GSK3543105, for which we were able to capture the bound SAH in a DNMT1-DNA-SAH-GSK3543105 quaternary complex (Figure 4A) by freezing the crystal shortly after its appearance. The interactions with the bound SAH are nearly identical in the ternary and the quaternary complexes with the residues at the two ends of the active-site loop, Pro1225 and Leu1247, flanking the cofactor binding pocket (Figure 4B). However, compared with the complexes lacking SAH, although the largest movement (~16.5 Å) occurs in the tip of the loop (e.g. Arg1234; Figure 2H), a much smaller movement (~2 Å for Pro1225) at the two ends of the loop is sufficient to weaken cofactor binding, with Met1169 moving into the space previously occupied by the adenosyl moiety in the SAH-bound form (Figure 4C). In addition, GSK3543105 has a longer substituent extending from the pyridine ring C2, containing a hydroxyethyl-diazepane moiety. The seven-membered diazepane takes a chair-like conformation on the minor-groove side of the 5mC:G base pair and the terminal hydroxy oxygen atom makes a H-bond with the base pair immediately outside of the CpG dinucleotide (Figure 4D). In summary, since the dicyanopyridine containing compounds bind outside of the SAH binding pocket, minimal movement in the overall DNMT1 structure is observed in the absence or presence of SAH.

Figure 4. Structure of the DNMT1-DNA-SAH-GSK3543105 quaternary complex.

(A) Surface representation showing that SAH remains bound in the presence of GSK3543105. (B) Superimposition of SAH binding in the ternary DNMT1-DNA-SAH (magenta) and quaternary DNMT1-DNA-SAH-GSK3543105 (yellow) complexes. (C) Superimposition of the two SAH-bound forms (magenta and yellow) with the structure of DNMT1-DNA-GSK3735967 that lacks SAH (grey). (D) The hydroxyethyl-diazepane moiety of GSK3543105 makes interactions with the neighboring base pair beyond 5mC:G pair.

DISCUSSION

Here we examined the structural features of human DNMT1 in complex with a set of six non-nucleoside inhibitors, which are potent, reversible, and selective for DNMT1. These compounds represent a distinct inhibitor chemotype containing a planar dicyanopyridine core that intercalates specifically into the DNMT1-bound, hemimethylated, CpG dinucleotide. Although, we do not yet understand how the inhibitor is initially directed to the CpG site, its ability to interact with the active-site loop, which also intercalates into the same CpG site, might suggest that the inhibitor collaborates and/or competes with the active-site loop to secure DNA access. The interaction of the inhibitor with the active-site loop (as seen in site 2) is likely the key to its specificity against DNMT1, because although Class I MTases share a common structure consisting of a seven-stranded Rossman-fold, the active-site loop size and amino acid sequence are not conserved among DNMTs (Schubert et al., 2003). One clue might come from prior experiments using modified analogues of GSK3685032 bearing photo-reactive tags, which labeled two active-site loop residues, Ser1230 and Gly1231 (Pappalardi et al., 2021). The principles of interactions between intercalating agents and the enzyme-specific active-site loop uncovered here may also be applicable to developing DNMT3a/3b-selective inhibitors.

We have been testing and refining compound designs, with an emphasis on optimizing the functionality at the pyridine ring carbons C2 and C6. The four compounds demonstrated IC50 values in the range of 30-60 nM (Figure 1C-1D). In the case of GSK3543105, the longer hydroxyethyl-diazepane moiety allows it to cover three DNA base pairs in the minor groove (Figure 4D), which extends its DNA intercalation to the minor groove. In the case of GSK3735967, we identified three inhibitor binding sites on DNMT1. The first site, site 1, was shared with all of the dicyanopyridine compounds tested, but the other sites, sites 2 and 3, were unique to GSK3543105 and required its extended benzyl acetamide branch for interaction. Superimposition of the GSK3735967 structures bound to these three distinct sites on DNMT1 (Figure S3D) showed that although the planar dicyanopyridine and diazepine moieties are well overlaid, the benzyl acetamide displays flexibility and can adopt different conformations to accommodate different binding environments.

Our structural findings reveal specific avenues for improving the potency and selectivity of DNMT1 inhibitors. For example, in site 3, the H4K20me3 binding site, the interaction between the inhibitor and Cys798 (Figure 3G) provides a unique opportunity to explore fragment-based inhibitory approaches such as using reversible covalent inhibitors that target the non-catalytic Cys798 (Awoonor-Williams et al., 2017; Horton et al., 2018; Johansson, 2012). Site 3 might also be further exploited by developing compounds that enhance histone peptide mimicry and consequently engage a different and/or expanded set of interactions. In addition, our discovery that the SAM/SAH can diffuse out of the cofactor-binding pocket, suggests that SAM/SAH analogues (Zhang and Zheng, 2016; Zhou et al., 2021) might be tested to determine whether they act additively or synergistically with the dicyanopyridine-based DNA-intercalating agents to further inhibit DNMT1.

STAR*METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Requests for further information, resources, and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Xiaodong Cheng (xcheng5@mdanderson.org).

Materials availability

Requests for GSK reagents should be directed to Melissa Pappalardi (Melissa.B.Pappalardi@gsk.com) and can be made available upon completion of a Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

The atomic coordinates and structure factors of DNMT1-DNA (zebularine)-inhibitor have been deposited to PDB and are publicly available as of the date of publications. Accession numbers and DOI are listed in the key resource table as well as in Table 1.

The paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Full-length DNMT1 protein (human, Gene ID 1786) | Pappalardi et al. (2021) Nature Cancer 2, 1002-1017 | N/A |

| Human DNMT1 residues 729-1600 expressed in E. coil | Hashimoto et al. (2012) Nucleic Acids Res 40, 4841-4849 | pXC896 |

| Human DNMT1 residues 351-1600 expressed in E. coil | Hashimoto et al. (2012) Nucleic Acids Res 40, 4841-4849 | pXC915 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| GSK3735967 | This paper | N/A |

| GSK3543105 | This paper | N/A |

| GSK3852279 | This paper | N/A |

| GSK3830334 | This paper | N/A |

| GSK3830052 | Pappalardi et al. (2021) Nature Cancer 2, 1002-1017 | N/A |

| GSK3685032 | Pappalardi et al. (2021) Nature Cancer 2, 1002-1017 | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Promega bioluminescence assay | Hsiao et al. (2016) Epigenomics 8, 321-339 | MTase-Glo |

| Deposited data | ||

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-GSK3735967 complex structure | This paper | PDB: 7SFC DOI: 10.2210/pdb7SFC/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-GSK3543105-SAH complex structure | This paper | PDB: 7SFD DOI: 10.2210/pdb7SFD/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-GSK3830334 complex structure | This paper | PDB: 7SFE DOI: 10.2210/pdb7SFE/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-GSK3852279 complex structure | This paper | PDB: 7SFF DOI: 10.2210/pdb7SFF/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-SAM complex structure | This paper | PDB: 7SFG DOI: 10.2210/pdb7SFG/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-SAH complex structure | Pappalardi et al. (2021) | PDB: 6X9I DOI: 10.2210/pdb6X9I/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-GSK3830052 complex structure | Pappalardi et al. (2021) | PDB: 6X9J DOI: 10.2210/pdb6X9J/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-GSK3685032 complex structure | Pappalardi et al. (2021) | PDB: 6X9K DOI: 10.2210/pdb6X9K/pdb |

| DNMT1 BAH1 in complex with H4K20me3 | Ren et al. (2021) | PDB: 7LMK DOI: 10.2210/pdb7LMK/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 601-1600)-Sinefungin complex structure | Hashimoto, H. and Cheng, X. (2011) | PDB: 3SWR DOI: 10.2210/pdb3SWR/pdb |

| DNMT3a-DNMT3L in complex with 2′-oxyzebularine | Zhang et al. (2018) | PDB: 5YX2 DOI: 10.2210/pdb5YX2/pdb |

| HhaI in complex with 2′-deooxyzebularine | Zhou et al. (2002) | PDB: 1M0E DOI: 10.2210/pdb1M0E/pdb |

| RNA duplex with a cytosine bulge in complex with berberine | Satpathi et al. (2021) | PDB: 7A3Y DOI: 10.2210/pdb7A3Y/pdb |

| Actinomycin-DNA complex | Satange et al. (2019) | PDB: 6J0H DOI: 10.2210/pdb6J0H/pdb |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| E. coli BL21(DE3) expression | N/A | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| 5’-GAGGCMGCCTGC-3’ (M=5-methylcytosine or 5mC) 3’-CTCCGGZGGACG-5’ (Z=zebularine) | New England Biolabs | N/A |

| 5’ -CCTGCGGAGGCTMGTCATGA-3’ (M=5mC) 3’ -GGACGCCTCCGAGCAGTACT -5’ | IDT | N/A |

| 5'-CCT CTT CTA ACT GCC ATM GAT CCT GAT AGC AGG TGC ATG C-3' (M=5mC) 3'-GGA GAA GAT TGA CGG TAG CTA GGA CTA TCG TCC ACG TAC G-5' | IDT | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

| HKL2000 | Otwinowski et al., 2003 | https://hkl-xray.com |

| PHENIX | Afonine et al., 2009 | https://phenix-online.org |

| COOT | Emsley and Cowtan, 2004 | https://openwetware.org |

| PyMOL | DeLano Scientific LLC | https://pymol.org |

| GraFit | Erithacus Software | http://www.erithacus.com/grafit/ |

| Other | ||

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Recombinant DNMT1 fragments were purified from expression in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3).

METHOD DETAILS

Protein Expression and Purification

The construct containing residues 729-1600 of human DNMT1 and an N-terminal 6xHis-SUMO tag was expressed using the plasmid pXC896 as previously described (Hashimoto et al., 2012). An overnight culture was grown in MDAG medium (Studier, 2005) containing 100 μg kanamycin at 37°C and was used to inoculate 12 L of unautoclaved LB broth containing 100 μg kanamycin. The cultures were grown to an A600 of ~1.0 at 37°C at which point the temperature was lowered to 16°C and the cultures were supplemented with 1 mM each of ZnCl2 and MgCl2. The cells were induced 1 h later with 0.4 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and incubated overnight at 16°C. The cell pellets were collected the next day by centrifugation and stored at −80°C. Pellets were suspended in the 0.5 M NaCl buffer [20 mM Hepes, pH 7.0, 5% glycerol, and 0.5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)] and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) was added before sonication (QSonica Q700) for 14 min with an amplitude of 70 % and a cycle of 5 sec on and 8 sec off. The resulting lysate was clarified by centrifugation and further passed through 3 μm syringe filter units.

A BIO-RAD NGC™ system was used to conduct three-column chromatography. The lysate was loaded onto a Ni-NTA column (GE, HisTrap HP 5 mL), washed with 0.5 M NaCl buffer containing 20 mM imidazole for 100 mL (20 column volumes) and eluted with a gradient from 20 mM to 500 mM imidazole over 100 mL. After assessment by SDS-PAGE, fractions containing DNMT1 were pooled and treated with ULP1 (purified in house) overnight at 4°C to cleave the 6xHis-SUMO tag. This sample of DNMT1 was then diluted to a salt concentration of 0.25 M with salt-free buffer and passed through an anion exchange column (GE, HiTrap Q HP 5 mL) in order to remove nucleic acid contamination. The flow-through containing DNMT1 was further purified through a heparin affinity column (GE 5 mL) with 25 mL of 0.25 M NaCl for washes and a gradient elution from 0.25 M to 1 M NaCl over 75 mL with DNMT1 eluting at ~0.7 M NaCl. DNMT1 was then concentrated to 0.5 mg/mL in the buffer it was eluted in before being flash frozen and stored at −80°C.

A stable complex of DNMT1 with a 12-base pair oligonucleotide containing zebularine in place of the target cytidine and with 5-methylcytosine on the opposite strand (synthesized by New England Biolabs) was formed and purified prior to crystallization (5’-GAGGCMGCCTGC-3’ and 5’-GCAGGZGGCCTC-3’ where M=5-methylcytosine and Z=zebularine). The duplex DNA was annealed in 20 mM Tris, pH 8, 50 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2. A 1.5 mL reaction containing a molar ratio of ~1:5:10 for DNMT1:DNA:SAH (or SAM) (~7-10 μM DNMT1, 50 μM zebularine-containing oligonucleotides, and 100 μM SAH (or SAM) in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl, 2.5 % glycerol, and 0.5 mM TCEP) was conducted at room temperature for 2 h with vigorous shaking on a benchtop shaker. The reaction mixture was then brought up to a volume of 15 mL and loaded onto a heparin column (GE), from which the stable complexes eluted at ~0.25 M NaCl and free DNMT1 eluted at ~0.7 M NaCl. The concentration of the stable complex was determined by comparison with DNMT1 standards via SDS-PAGE and densitometry (BioRad software). The protein-DNA complex was then concentrated to ~5.5 mg/mL (~55 μM) DNMT1 using Millipore Amicon 50-kDa MWCO units, and the concentration was verified by SDS-PAGE.

To prepare DNMT1-DNA-inhibitor complexes, the inhibitors were first suspended in DMSO at a stock concentration of 50 mM, before preparing a 4-fold dilution to 12.5 mM in 0.25 M NaCl buffer (the same buffer as the protein-DNA complexes). To prepare a 32 μL sample for crystallization, 29 μL of DNMT1-DNA complex (at ~55 μM) was mixed with 1 μL of inhibitor (at 12.5 mM) and 2 μL of 0.25 M NaCl buffer. This brought the final concentration of the protein-DNA complexes to ~50 μM and the inhibitor to ~420 μM with the molar ratio of protein to inhibitor being ~1:8.

In vitro DNA methylation inhibition assay

Generation of full-length recombinant DNMT1 protein (human, Gene ID 1786) and activity assessment using a radioactive SPA assay were described previously (Pappalardi et al., 2021). Briefly, final assay concentrations consisted of 15-30 nM DNMT1, 80 nM DNA (40-mer hemi-methylated duplex) and 1.7 μM SAM (comprised of 14-32% 3H-SAM) in 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, and 2.4% DMSO. Compounds (typically 10-point, 3-fold serial dilution) were dissolved in DMSO and pre-stamped into a 96-well plate (Corning, 3884). Reaction was initiated upon the addition of 2x enzyme, incubated for 30 min at room temperature, quenched with SAH, and captured using PEI PVT SPA beads (2 mg/ml, PerkinElmer RPNQ0097). Plates were read on a MicroBeta (PerkinElmer). Data were fit using a three-parameter dose–response equation in GraFit (Erithacus Software) to yield IC50 values.

In addition, DNA methylation activity was measured using the Promega bioluminescence assay (MTase-Glo) in which the reaction by-product SAH is converted into ATP in a two-step reaction, and ATP can be detected through a luciferase reaction (Hsiao et al., 2016). The recombinant DNMT1 (residues 351-1600; pXC915) used in the assay and the reaction conditions were described previously (Hashimoto et al., 2012). The DNA substrate is a double-stranded oligonucleotide containing a single hemi-methylated CpG site (5’ -CCT GCG GAG GCT MGT CAT GA -3’ where M=5-methylcytosine and its complementary strand 3’ -GGA CGC CTC CGA GCA GTA CT -5’). Briefly, reactions were carried out at 37°C for 1 h in duplicates with 10 μL reaction mixture containing 100 nM DNMT1, 5.5 μM SAM, 1.0 μM DNA and inhibitors at the designated concentrations in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 1 mM EDTA. DNMT1 was pre-incubated with SAM for 10 min at 37°C, prior to the addition of DNA and inhibitor. Reactions were terminated by the addition of trifluoroacetic acid to a final concentration of 0.1% (v/v). A 5-μL reaction sample was transferred to a low-volume 384-well plate and the luminescence assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A Synergy 4 multimode microplate reader (BioTek) was used to measure luminescence signal.

Crystallography

Solutions of complexes including components of DNMT1, DNA and inhibitor were incubated for 1h at 4°C before crystallization. Crystals of DNMT1-DNA complexes, in the absence and presence of inhibitor, were grown via the sitting drop vapor diffusion method using an Art Robbins Gryphon Crystallization Robot at room temperature (~19°C). The crystallization conditions contained 14-18% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350, 0.1 M citric acid (pH 5.1) which was mixed with equal volumes of DNMT1-DNA complex and precipitating agents (drop sizes ranged from 0.4 μL - 4 μL). Crystals usually appeared overnight and were picked up and flash frozen in mother liquor supplemented with 20 % ethylene glycol.

All X-ray diffraction datasets were collected at the SER-CAT beamline 22ID of the Advanced Photon Source at the Argonne National Laboratory with an X-ray wavelength of 1.0000Å. The crystals were cooled at 100K. Crystallographic datasets were processed with HKL2000 (Otwinowski et al., 2003). The structures of DNMT1 in complex with zebularine-containing DNA in the presence of cofactor with or without inhibitor were solved by the difference Fourier method using our previously determined structures (PDB 6X9I or 6X9J). All crystals were isomorphous, and rigid body refinement was used for positioning the new structures in the unit cell, and difference electron density maps (2Fo-Fc and Fo-Fc) were used for locating bound inhibitor molecules. SMILES strings were input into the PHENIX eLBOW module (Moriarty et al., 2009) to generate and optimize inhibitor restraints and supply its structure in PDB format. PHENIX REFINE (Afonine et al., 2012) was used for all refinements which had 5% randomly chosen reflections for validation by the R-free value. COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) was used for inhibitor placement and model corrections between refinement rounds. Structure quality was analyzed during PHENIX refinements and later validated by the PDB validation server. Molecular graphics were generated using PyMOL (Schrödinger).

Chemical syntheses

The syntheses of compounds of GSK3830052 and GSK3685032 have been described recently (Pappalardi et al., 2021). The following guidelines apply to all chemistry experimental procedures described herein. All reactions were conducted under a positive pressure of nitrogen, unless otherwise indicated. The designated temperatures are external and approximate. Air and moisture-sensitive liquids were transferred via syringe. Reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used as received. For solvents, those listed as “anhydrous” by vendors were used. Molarities listed for reagents in solutions are approximate, and were used without prior titration against a corresponding standard. All reactions were agitated by stir bar, unless otherwise indicated. Anhydrous grade magnesium sulfate and sodium sulfate were used interchangeably as drying agents. Solvents described as being removed “in vacuo” or “under reduced pressure” were subjected to rotary evaporation.

Preparative normal phase silica gel chromatography was carried out using one of three instruments: a Teledyne ISCO CombiFlash Companion instrument with RediSep or ISCO Gold silica gel cartridges (4 g – 330 g); an Analogix IF280 instrument with SF25 silica gel cartridges (4 g – 300g); or a Biotage SP1 instrument with HP silica gel cartridges (10g – 100 g). Reverse phase HPLC purification was conducted using one of the following methods: (i) Gilson HPLC (UV detection at a wavelength of 214 or 254 nm) with a Phenomenex Gemini C18 column (5 μm, 50 mm x 30 mm), eluting with a CH3CN/H20 gradient with either a 0.1% TFA modifier or a 0.1% NH4OH modifier; (ii) Waters mass-directed auto purification system (MDAP) (UV detection was an averaged signal of 210 to 350 nm) with a XSELECT CSH C18 column (5 μm, 150 mm x 30 mm) coupled with a Waters Acquity QDa mass detector (positive and negative ESI), eluting with CH3CN/H2O gradient with either a 0.1% TFA modifier or with a 0.1% NH4HCO3 modifier.

LCMS analysis was conducted using one of the following methods: (i) Sciex LCMS analysis was performed on a PE Sciex Single Quadrupole 150EX, using a Thermo Hypersil Gold C18 column (1.9 μm, 20 × 2.1 mm), 4–95% CH3CN/H2O (with 0.1% TFA) over 2 min, flow rate = 1.4 mL/min at 55°C; (ii) Waters LCMS analysis was performed on a Waters Acquity SQD UPLC/MS system, using a CSH C18 column (1.7 μm, 30 x 2.1 mm), 1-99% CH3CN/H2O (with 0.1% TFA) over 2 min, flow rate = 1.3 mL/min at 45°C. All tested compounds were determined to be >95% purity by LCMS unless otherwise noted. Analytical HPLC purity determinations were performed on an Agilent 1200 HPLC equipped with a ZORBAX XDB C18 column (3.5 μm, 150 x 4.6 mm), 5-95% CH3CN/H2O (with 0.1% TFA) over 10 min, flow rate = 1.5 mL/min. The retention time (Rt) is expressed in minutes at a UV detection wavelength of 214 or 254 nm.

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Advance or Varian Unity 400 MHz spectrometer and data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity, coupling constants, integration. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to an internal solvent reference. Apparent peak multiplicities are described as s (singlet), brs (broad singlet), d (doublet), dd (doublet of doublets), t (triplet), q (quartet), or m (multiplet). Coupling constants (J) are reported in hertz (Hz).

Synthesis of 2-amino-N-(4-(((3,5-dicyano-4-ethyl-6-(4-methyl-1,4-diazepan-1-yl)pyridin-2-yl)thio)methyl)benzyl)acetamide (GSK3735967)

The title compound was prepared according to patent WO2017216727A1 Example 80 (Substituted Pyridines as Inhibitors of DNMT1). LCMS m/z = 478.3 [M+H]+. Analytical HPLC purity = 100% (Rt 4.2 min, 254 nm). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 8.29 (s, 1H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.47 (s, 2H), 4.27 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 3.82-3.95 (m, 4H), 3.12 (s, 2H), 2.78 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.60-2.69 (m, 2H), 2.24 (s, 3H), 1.88-1.97 (m, 2H), 1.80 (br. s, 2H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H), (2H obscured by DMSO). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C25H32N7OS, 478.2389; found, 478.2391.

2-((3,5-dicyano-4-ethyl-6-(4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1,4-diazepan-1-yl)pyridin-2-yl)thio)-2-phenylacetamide (GSK3543105)

The title compound was prepared according to patent WO2017216727A1 Example 318 (Substituted Pyridines as Inhibitors of DNMT1). LCMS m/z = 465.3 [M+H]+. Analytical HPLC purity = 97.3% (Rt 3.9 min, 214 nm). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 7.91 (s, 1H), 7.49 (br. d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.40-7.23 (m, 4H), 5.51 (s, 1H), 4.38 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 3.95-3.80 (m, 4H), 3.47 (q, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 2.88-2.72 (m, 4H), 2.56-2.52 (m, 2H), 2.52-2.42 (m, 2H), 1.89 (br. s, 2H), 1.21 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C24H29N6O2S, 465.2073; found, 465.2069.

2-((6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)-3,5-dicyano-4-ethylpyridin-2-yl)thio)-2-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)acetamide trifluoroacetate (GSK3852279)

The title compound was prepared according to patent WO2017216727A1 Example 410 (Substituted Pyridines as Inhibitors of DNMT1) with the modification that reverse phase HPLC purification was performed with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid as the mobile phase modifier to provide the trifluoroacetate salt. LCMS m/z = 489.1 [M+H]+. Analytical HPLC purity = 100% (Rt 6.2 min, 254 nm). 1H NMR (non-trifluoroacetate salt) (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.07 (s, 1H), 7.84-7.69 (m, 4H), 7.49 (s, 1H), 5.68 (s, 1H), 4.41 - 4.28 (m, 2H), 3.32 - 3.22 (m, 2H), 2.95 - 2.86 (m, 1H), 2.75 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.95-1.66 (m, 4H), 1.35-1.17 (m, 5H).

(R)-2-((6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)-3,5-dicyano-4-ethylpyridin-2-yl)amino)-2-phenylacetamide (GSK3830334)

Step 1: To a stirred solution of tert-butyl (1-(6-chloro-3,5-dicyano-4-ethylpyridin-2-yl)piperidin-4-yl)carbamate (For preparation, see WO2017216727A1 Example 81, Step 1) (3.5 g, 8.82 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (THF) (40 mL) at 0 °C was sequentially added (R)-2-amino-2-phenylacetamide (1.324 g, 8.82 mmol) and triethylamine (2.46 mL, 17.6 mmol). After stirring for 16 h at 25 °C, the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure, diluted with water (50 mL), and extracted with ethyl acetate (2 x 60 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The remaining residue was triturated with diethyl ether (20 mL) to provide (R)-tert-butyl (1-(6-((2-amino-2-oxo-1-phenylethyl)amino)-3,5-dicyano-4-ethylpyridin-2-yl)piperidin-4-yl)carbamate (3 g, 68%) as an off-white solid. LCMS m/z = 504.2 [M+H]+.

Step 2: To a stirred solution of (R)-tert-butyl (1-(6-((2-amino-2-oxo-1-phenylethyl)amino)-3,5-dicyano-4-ethylpyridin-2-yl)piperidin-4-yl)carbamate (1 g, 1.98 mmol) from Step 1 in 1,4-dioxane (10 mL) at 0 °C was added HCl solution (4.0 M in dioxane, 4.96 mL, 19.8 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 4h at 25 °C. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo and the remaining crude product triturated with diethyl ether (2 x 30 mL) and dried under vacuum to afford (R)-2-((6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)-3,5-dicyano-4-ethylpyridin-2-yl)amino)-2-phenylacetamide hydrochloride (570 mg, 64% yield) as an off-white solid. LCMS m/z = 404.2 [M+H]+. Analytical HPLC purity = 98.4% (Rt 3.7 min, 254 nm). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 7.96 - 8.19 (m, 3H), 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.44 - 7.52 (m, 2H), 7.20 - 7.43 (m, 5H), 5.46 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 4.38 (br. d, J = 14.5 Hz, 2H), 3.32 - 3.39 (m, 1H), 3.10 (q, J = 11.3 Hz, 2H), 2.71 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.97 (br. t, J = 12.9 Hz, 2H), 1.51 - 1.61 (m, 1H), 1.34 - 1.42 (m, 1H), 1.20 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C22H26N7O, 404.2199; found, 404.2200.

QUANTIFICATION AND ATATISTICAL ANALYSIS

X-ray crystallographic data were measured quantitatively and processed with HKL2000. Structure refinements were performed by PHENIX Refine with 5% randomly chosen reflections for validation by R-free values. The data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table 1. Structure quality was analyzed during rounds of PHENIX refinements and validated by the PDB server. Statistic details on inhibitory experiments can be found in Figure 1D (including IC50 ± SEM, N number of replicates) and in the legend of Figure S4.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Dicyanopydridine containing DNMT1-specific inhibitors act on DNMT1-bound DNA

Dicyanopydridine intercalates into the hemi-methylated DNA between two CpG base pairs

The bound inhibitor results in displacement of the DNMT1 active-site loop

GSK3735967 has three binding sites including an open aromatic cage where H4K20me3 binds

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Hideharu Hashimoto for his initial work preparing expression constructs, purifying human DNMT1 protein, and determining the DNMT1-Sinefungin structure (PDB 3SWR). We thank Ms. B. Baker of New England Biolabs for synthesizing the oligonucleotides containing zebularine. We also thank the Drug Discovery Unit at Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute as well as the Cancer Epigenetics Research Unit and the Medicinal Science & Technology group at GlaxoSmithKline for their contributions towards the identification of this series of DNMT1 selective inhibitors. We thank Dr. Briana Dennehey for editing the manuscript and insightful comments. This work in MDACC was supported by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) grant (RR160029) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant (R35GM134744) to X.C., who is a CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

M.B.P., K.W., L.R., D.T.F., D.H., M.T.M. and B.W.K. are/were employees and/or shareholders of GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH, and Adams PD (2012). Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 68, 352–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allis CD, Jenuwein T, and Reinberg D (2015). Epigenetics, second edition (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Awoonor-Williams E, Walsh AG, and Rowley CN (2017). Modeling covalent-modifier drugs. Biochim Biophys Acta 1865, 1664–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brueckner B, Garcia Boy R, Siedlecki P, Musch T, Kliem HC, Zielenkiewicz P, Suhai S, Wiessler M, and Lyko F (2005). Epigenetic reactivation of tumor suppressor genes by a novel small-molecule inhibitor of human DNA methyltransferases. Cancer Res 65, 6305–6311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli G, and Heard E (2019). Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature 571, 489–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, and Roberts RJ (2001). AdoMet-dependent methylation, DNA methyltransferases and base flipping. Nucleic Acids Res 29, 3784–3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta J, Ghoshal K, Denny WA, Gamage SA, Brooke DG, Phiasivongsa P, Redkar S, and Jacob ST (2009). A new class of quinoline-based DNA hypomethylating agents reactivates tumor suppressor genes by blocking DNA methyltransferase 1 activity and inducing its degradation. Cancer Res 69, 4277–4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Emsley P, and Cowtan K (2004). Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flotho C, Claus R, Batz C, Schneider M, Sandrock I, Ihde S, Plass C, Niemeyer CM, and Lubbert M (2009). The DNA methyltransferase inhibitors azacitidine, decitabine and zebularine exert differential effects on cancer gene expression in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Leukemia 23, 1019–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbara S, and Bhagwat AS (1995). The mechanism of inhibition of DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferases by 5-azacytosine is likely to involve methyl transfer to the inhibitor. Biochem J 307 (Pt 1), 87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan A, Arimondo PB, Rots MG, Jeronimo C, and Berdasco M (2019). The timeline of epigenetic drug discovery: from reality to dreams. Clinical epigenetics 11, 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin AG, Groy A, Gore ER, Atkins C, Long ER, Montoute MN, Wu Z, Halsey W, McNulty DE, Ennulat D, et al. (2021). In vitro and in vivo induction of fetal hemoglobin with a reversible and selective DNMT1 inhibitor. Haematologica 106, 1979–1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros C, Fleury L, Nahoum V, Faux C, Valente S, Labella D, Cantagrel F, Rilova E, Bouhlel MA, David-Cordonnier MH, et al. (2015). New insights on the mechanism of quinoline-based DNA Methyltransferase inhibitors. J Biol Chem 290, 6293–6302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty C, Kretzmer H, Riemenschneider C, Kumar AS, Mattei AL, Bailly N, Gottfreund J, Giesselmann P, Weigert R, Brandl B, et al. (2021). Dnmt1 has de novo activity targeted to transposable elements. Nat Struct Mol Biol 28, 594–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halby L, Menon Y, Rilova E, Pechalrieu D, Masson V, Faux C, Bouhlel MA, David-Cordonnier MH, Novosad N, Aussagues Y, et al. (2017). Rational Design of Bisubstrate-Type Analogues as Inhibitors of DNA Methyltransferases in Cancer Cells. J Med Chem 60, 4665–4679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Liu Y, Upadhyay AK, Chang Y, Howerton SB, Vertino PM, Zhang X, and Cheng X (2012). Recognition and potential mechanisms for replication and erasure of cytosine hydroxymethylation. Nucleic Acids Res 40, 4841–4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JR, Woodcock CB, Chen Q, Liu X, Zhang X, Shanks J, Rai G, Mott BT, Jansen DJ, Kales SC, et al. (2018). Structure-Based Engineering of Irreversible Inhibitors against Histone Lysine Demethylase KDM5A. J Med Chem 61, 10588–10601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Zegzouti H, and Goueli SA (2016). Methyltransferase-Glo: a universal, bioluminescent and homogenous assay for monitoring all classes of methyltransferases. Epigenomics 8, 321–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Stillson NJ, Sandoval JE, Yung C, and Reich NO (2021). A novel class of selective non-nucleoside inhibitors of human DNA methyltransferase 3A. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 40, 127908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd PJ, Whitmarsh AJ, Baldwin GS, Kelly SM, Waltho JP, Price NC, Connolly BA, and Hornby DP (1999). Mechanism-based inhibition of C5-cytosine DNA methyltransferases by 2-H pyrimidinone. J Mol Biol 286, 389–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrold J, and Davies CC (2019). PRMTs and Arginine Methylation: Cancer's Best-Kept Secret? Trends Mol Med 25, 993–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson MH (2012). Reversible Michael additions: covalent inhibitors and prodrugs. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry 12, 1330–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA, and Taylor SM (1980). Cellular differentiation, cytidine analogs and DNA methylation. Cell 20, 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser S, Jurkowski TP, Kellner S, Schneider D, Jeltsch A, and Helm M (2017). The RNA methyltransferase Dnmt2 methylates DNA in the structural context of a tRNA. RNA Biol 14, 1241–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaliman P (2019). Epigenetics and meditation. Curr Opin Psychol 28, 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimasauskas S, Kumar S, Roberts RJ, and Cheng X (1994). HhaI methyltransferase flips its target base out of the DNA helix. Cell 76, 357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Horton JR, Jones GD, Walker RT, Roberts RJ, and Cheng X (1997). DNA containing 4'-thio-2'-deoxycytidine inhibits methylation by HhaI methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res 25, 2773–2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo AJ, Song J, Cheung P, Ishibe-Murakami S, Yamazoe S, Chen JK, Patel DJ, and Gozani O (2012). The BAH domain of ORC1 links H4K20me2 to DNA replication licensing and Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Nature 484, 115–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manara MC, Valente S, Cristalli C, Nicoletti G, Landuzzi L, Zwergel C, Mazzone R, Stazi G, Arimondo PB, Pasello M, et al. (2018). A Quinoline-Based DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitor as a Possible Adjuvant in Osteosarcoma Therapy. Molecular cancer therapeutics 17, 1881–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty NW, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, and Adams PD (2009). electronic Ligand Builder and Optimization Workbench (eLBOW): a tool for ligand coordinate and restraint generation. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 65, 1074–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Gara M, Horton JR, Roberts RJ, and Cheng X (1998). Structures of HhaI methyltransferase complexed with substrates containing mismatches at the target base. Nat Struct Biol 5, 872–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Borek D, Majewski W, and Minor W (2003). Multiparametric scaling of diffraction intensities. Acta Crystallogr A 59, 228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappalardi MB, Keenan K, Cockerill M, Kellner WA, Stowell A, Sherk C, Wong K, Pathuri S, Briand J, Steidel M, et al. (2021). Discovery of a first-in-class reversible DNMT1-selective inhibitor with improved tolerability and efficacy in acute myeloid leukemia. Nature Cancer. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portilho NA, Saini D, Hossain I, Sirois J, Moraes C, and Pastor WA (2021). The DNMT1 inhibitor GSK-3484862 mediates global demethylation in murine embryonic stem cells. bioRxiv, 2021.2009.2012.459949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren W, Fan H, Grimm SA, Kim JJ, Li L, Guo Y, Petell CJ, Tan XF, Zhang ZM, Coan JP, et al. (2021). DNMT1 reads heterochromatic H4K20me3 to reinforce LINE-1 DNA methylation. Nat Commun 12, 2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RJ, and Cheng X (1998). Base flipping. Annu Rev Biochem 67, 181–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotili D, Tarantino D, Marrocco B, Gros C, Masson V, Poughon V, Ausseil F, Chang Y, Labella D, Cosconati S, et al. (2014). Properly Substituted Analogues of BIX-01294 Lose Inhibition of G9a Histone Methyltransferase and Gain Selective Anti-DNA Methyltransferase 3A Activity. PLoS ONE 9, e96941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi DV, Norment A, and Garrett CE (1984). Covalent bond formation between a DNA-cytosine methyltransferase and DNA containing 5-azacytosine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81, 6993–6997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapienza C, and Issa JP (2016). Diet, Nutrition, and Cancer Epigenetics. Annu Rev Nutr 36, 665–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satange R, Chuang CY, Neidle S, and Hou MH (2019). Polymorphic G:G mismatches act as hotspots for inducing right-handed Z DNA by DNA intercalation. Nucleic Acids Res 47, 8899–8912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Issa JJ, and Kropf P (2017). DNA Hypomethylating Drugs in Cancer Therapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satpathi S, Endoh T, Podbevsek P, Plavec J, and Sugimoto N (2021). Transcriptome screening followed by integrated physicochemical and structural analyses for investigating RNA-mediated berberine activity. Nucleic Acids Res 49, 8449–8461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert HL, Blumenthal RM, and Cheng X (2003). Many paths to methyltransfer: a chronicle of convergence. Trends Biochem Sci 28, 329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikhnejad G, Brank A, Christman JK, Goddard A, Alvarez E, Ford H Jr., Marquez VE, Marasco CJ, Sufrin JR, O'Gara M, et al. (1999). Mechanism of inhibition of DNA (cytosine C5)-methyltransferases by oligodeoxyribonucleotides containing 5,6-dihydro-5-azacytosine. J Mol Biol 285, 2021–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siklos M, and Kubicek S (2021). Therapeutic targeting of chromatin: Status and opportunities. FEBS J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS (1994). Biological implications of the mechanism of action of human DNA (cytosine-5)methyltransferase. Progress in nucleic acid research and molecular biology 49, 65–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Teplova M, Ishibe-Murakami S, and Patel DJ (2012). Structure-based mechanistic insights into DNMT1-mediated maintenance DNA methylation. Science 335, 709–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni A, Khurana P, Singh T, and Jayaram B (2017). A DNA intercalation methodology for an efficient prediction of ligand binding pose and energetics. Bioinformatics 33, 1488–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stomper J, Rotondo JC, Greve G, and Lubbert M (2021). Hypomethylating agents (HMA) for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes: mechanisms of resistance and novel HMA-based therapies. Leukemia 35, 1873–1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier FW (2005). Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr Purif 41, 207–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C, Ford K, Connolly BA, and Hornby DP (1993). Determination of the order of substrate addition to MspI DNA methyltransferase using a novel mechanism-based inhibitor. Biochem J 291 (Pt 2), 493–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente S, Liu Y, Schnekenburger M, Zwergel C, Cosconati S, Gros C, Tardugno M, Labella D, Florean C, Minden S, et al. (2014). Selective non-nucleoside inhibitors of human DNA methyltransferases active in cancer including in cancer stem cells. J Med Chem 57, 701–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankova E, Blackaby W, Albertella M, Rak J, De Braekeleer E, Tsagkogeorga G, Pilka ES, Aspris D, Leggate D, Hendrick AG, et al. (2021). Small-molecule inhibition of METTL3 as a strategy against myeloid leukaemia. Nature 593, 597–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo CB, and Jones PA (2006). Epigenetic therapy of cancer: past, present and future. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5, 37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, and Zheng YG (2016). SAM/SAH Analogs as Versatile Tools for SAM-Dependent Methyltransferases. ACS Chem Biol 11, 583–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZM, Lu R, Wang P, Yu Y, Chen D, Gao L, Liu S, Ji D, Rothbart SB, Wang Y, et al. (2018). Structural basis for DNMT3A-mediated de novo DNA methylation. Nature 554, 387–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Horton JR, Yu D, Ren R, Blumenthal RM, Zhang X, and Cheng X (2021). Repurposing epigenetic inhibitors to target the Clostridioides difficile-specific DNA adenine methyltransferase and sporulation regulator CamA. Epigenetics, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Cheng X, Connolly BA, Dickman MJ, Hurd PJ, and Hornby DP (2002). Zebularine: a novel DNA methylation inhibitor that forms a covalent complex with DNA methyltransferases. J Mol Biol 321, 591–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwergel C, Schnekenburger M, Sarno F, Battistelli C, Manara MC, Stazi G, Mazzone R, Fioravanti R, Gros C, Ausseil F, et al. (2019). Identification of a novel quinoline-based DNA demethylating compound highly potent in cancer cells. Clinical epigenetics 11, 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The atomic coordinates and structure factors of DNMT1-DNA (zebularine)-inhibitor have been deposited to PDB and are publicly available as of the date of publications. Accession numbers and DOI are listed in the key resource table as well as in Table 1.

The paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Full-length DNMT1 protein (human, Gene ID 1786) | Pappalardi et al. (2021) Nature Cancer 2, 1002-1017 | N/A |

| Human DNMT1 residues 729-1600 expressed in E. coil | Hashimoto et al. (2012) Nucleic Acids Res 40, 4841-4849 | pXC896 |

| Human DNMT1 residues 351-1600 expressed in E. coil | Hashimoto et al. (2012) Nucleic Acids Res 40, 4841-4849 | pXC915 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| GSK3735967 | This paper | N/A |

| GSK3543105 | This paper | N/A |

| GSK3852279 | This paper | N/A |

| GSK3830334 | This paper | N/A |

| GSK3830052 | Pappalardi et al. (2021) Nature Cancer 2, 1002-1017 | N/A |

| GSK3685032 | Pappalardi et al. (2021) Nature Cancer 2, 1002-1017 | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Promega bioluminescence assay | Hsiao et al. (2016) Epigenomics 8, 321-339 | MTase-Glo |

| Deposited data | ||

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-GSK3735967 complex structure | This paper | PDB: 7SFC DOI: 10.2210/pdb7SFC/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-GSK3543105-SAH complex structure | This paper | PDB: 7SFD DOI: 10.2210/pdb7SFD/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-GSK3830334 complex structure | This paper | PDB: 7SFE DOI: 10.2210/pdb7SFE/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-GSK3852279 complex structure | This paper | PDB: 7SFF DOI: 10.2210/pdb7SFF/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-SAM complex structure | This paper | PDB: 7SFG DOI: 10.2210/pdb7SFG/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-SAH complex structure | Pappalardi et al. (2021) | PDB: 6X9I DOI: 10.2210/pdb6X9I/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-GSK3830052 complex structure | Pappalardi et al. (2021) | PDB: 6X9J DOI: 10.2210/pdb6X9J/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 729-1600)-DNA-GSK3685032 complex structure | Pappalardi et al. (2021) | PDB: 6X9K DOI: 10.2210/pdb6X9K/pdb |

| DNMT1 BAH1 in complex with H4K20me3 | Ren et al. (2021) | PDB: 7LMK DOI: 10.2210/pdb7LMK/pdb |

| DNMT1 (residues 601-1600)-Sinefungin complex structure | Hashimoto, H. and Cheng, X. (2011) | PDB: 3SWR DOI: 10.2210/pdb3SWR/pdb |

| DNMT3a-DNMT3L in complex with 2′-oxyzebularine | Zhang et al. (2018) | PDB: 5YX2 DOI: 10.2210/pdb5YX2/pdb |

| HhaI in complex with 2′-deooxyzebularine | Zhou et al. (2002) | PDB: 1M0E DOI: 10.2210/pdb1M0E/pdb |

| RNA duplex with a cytosine bulge in complex with berberine | Satpathi et al. (2021) | PDB: 7A3Y DOI: 10.2210/pdb7A3Y/pdb |

| Actinomycin-DNA complex | Satange et al. (2019) | PDB: 6J0H DOI: 10.2210/pdb6J0H/pdb |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| E. coli BL21(DE3) expression | N/A | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| 5’-GAGGCMGCCTGC-3’ (M=5-methylcytosine or 5mC) 3’-CTCCGGZGGACG-5’ (Z=zebularine) | New England Biolabs | N/A |

| 5’ -CCTGCGGAGGCTMGTCATGA-3’ (M=5mC) 3’ -GGACGCCTCCGAGCAGTACT -5’ | IDT | N/A |

| 5'-CCT CTT CTA ACT GCC ATM GAT CCT GAT AGC AGG TGC ATG C-3' (M=5mC) 3'-GGA GAA GAT TGA CGG TAG CTA GGA CTA TCG TCC ACG TAC G-5' | IDT | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

| HKL2000 | Otwinowski et al., 2003 | https://hkl-xray.com |

| PHENIX | Afonine et al., 2009 | https://phenix-online.org |

| COOT | Emsley and Cowtan, 2004 | https://openwetware.org |

| PyMOL | DeLano Scientific LLC | https://pymol.org |

| GraFit | Erithacus Software | http://www.erithacus.com/grafit/ |

| Other | ||