Abstract

Salinity stress adversely affects plant growth and causes considerable losses in cereal crops. Salinity stress tolerance is a complex phenomenon, imparted by the interaction of compounds involved in various biochemical and physiological processes. Conventional breeding for salt stress tolerance has had limited success. However, the availability of molecular marker-based high-density linkage maps in the last two decades boosted genomics-based quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping and QTL-seq approaches for fine mapping important major QTL for salinity stress tolerance in rice, wheat, and maize. For example, in rice, ‘Saltol’ QTL was successfully introgressed for tolerance to salt stress, particularly at the seedling stage. Transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics also offer opportunities to decipher and understand the molecular basis of stress tolerance. The use of proteomics and metabolomics-based metabolite markers can serve as an efficient selection tool as a substitute for phenotype-based selection. This review covers the molecular mechanisms for salinity stress tolerance, recent progress in mapping and introgressing major gene/QTL (genomics), transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics in major cereals, viz., rice, wheat and maize.

Subject terms: Plant sciences, Genetics

Introduction

Crop plants experience many biotic and abiotic stresses at different stages during their life cycle. Like other major abiotic stresses (drought and heat), soil salinity threatens global food security, affecting one-quarter to one-third of global crop production (Munns 2002; Abbasi et al. 2015). Soil salinity affects plant growth and development, decreasing agricultural production worldwide (Zhu 2001; Wang et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2021). More than 800 million hectares of land are affected by salinity, accounting for 6% of the earth’s total land area and 20% of the total cultivated land area (Munns and Tester 2008; Sandhu et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2021). The saline area is expected to increase due to the application of high salt irrigation water owing to insufficient rainfall and poor agricultural practices (Luo et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2021), particularly in arid and semi-arid areas with higher evapotranspiration than precipitation (Hanin et al. 2016; Kashyap et al. 2017; Jha et al. 2019). In addition, the climate change-induced rise in mean sea level results in flooding, especially in coastal areas causing soil salinity (Nicholls et al. 2011; Church et al. 2003). Salt-affected land is estimated to reach 50% of the total arable area by 2050 (Wang et al. 2003; Shrivastava and Kumar 2015; Kumar and Sharma 2020), making it challenging to meet the projected food production needs for the increasing human population (Tnay 2019).

Rice, wheat, and maize are the most important cereal crops, accounting for >50% of the world’s calorie consumption (Gibbon 2012; Luo et al. 2019). Human consumption accounts for 85% of total rice, 72% of total wheat, and 19% of total maize production (http://www.knowledgebank.irri.org). Globally, wheat is ranked first for area planted, maize for production, and rice for production value (Benavente and Giménez 2021). The demand for major cereal crops will increase threefold by 2050 to feed nine billion people. However, salt stress is a major concern for cereal crop production globally as it affects different plant growth stages and leads to abnormalities at the phenotypic, morphological, biochemical, and physiological levels (James et al. 2011). Rice is more sensitive to salt stress than maize (moderately sensitive) and wheat (moderately tolerant). Hence, to address yield losses due to salinity, development of salt-tolerant cultivars (without yield penalty under salt-stressed conditions) is an important requirement (Kashyap et al. 2017; Jha et al. 2019). Conventional breeding has had limited success due to the complex genetic nature of salt tolerance. Recent advances in ‘omics’ technologies, such as genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and QTLomics, can help identify key genes and biomolecules regulating salt tolerance (Ahmad et al. 2016).

Several studies have reviewed various aspects of salt tolerance in different crops (Jha et al. 2019; Gupta et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2021b; Singh et al. 2021), but none have comprehensively integrated the literature on the application of all omics approaches for salt stress tolerance in major cereal crops, viz., rice, wheat, and maize. Here, we review, the impact of salinity on the growth and development of rice, wheat and maize, the adaptive mechanisms involved, and progress in genomic-assisted breeding for salinity stress tolerance in cereal crops. Recent progress in transcriptomics and proteomics is also discussed to reveal the candidate genes and proteins imparting salinity stress tolerance in wheat, maize and rice. The comparative assessment of candidate genes or proteins across the major cereal crops revealed key common genes imparting salinity stress tolerance. Hence, this comprehensive review will serve as a useful guide for salinity breeders to understand the common genes/proteins imparting salinity stress tolerance.

Impact of soil salinity on cereal crops

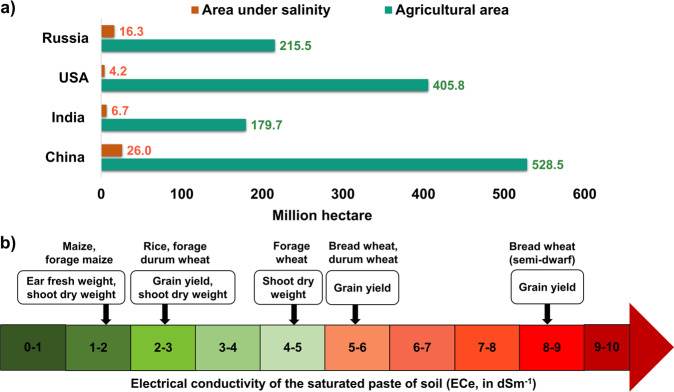

Soil salinity is defined as a high concentration of solute salts in soils, causing more than 4 dS/m electric conductivity. Salinity adversely affects plant growth and development through its effect on physiological and biochemical pathways (Nabati et al. 2011), severely constraining major cereal crop production, with yield losses of 60% in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) (El-Hendawy et al. 2017) and 50% in rice (Oryza sativa L.) (Van Genuchten and Gupta 1993), and reductions of 51.43% dry weight and 53.18% leaf area, in maize (Zea mays L.) (Hussein et al. 2007). However, the extent of crop damage varies with salt-stress timing, crop growth stage, plant type and genotype, and climatic conditions (Shahverdi et al. 2018). Each crop has a salt tolerance threshold level measured as the electrical conductivity of a saturated paste of soil (ECe). Rice is the most sensitive crop to salinity (3 dS/m) (Munns and Tester 2008), maize is moderately sensitive (1.8 dS/m) (Rhoades et al. 1992), and wheat is moderately tolerant (6 dS/m). However, the threshold varies depending on the target trait and crop growth stage (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Salinity stress acreage and thresholds in major cereal crops.

a Area under salinity for important cereal (wheat, maize and rice) producing countries; b Different thresholds for salinity sensitivity of various traits in different crops (refer Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for data source).

Rice is sensitive to salinity particularly at the seedling and panicle initiation to flowering stages (Moradi et al. 2003), whereas wheat is the most vulnerable to salinity during early development (i.e., germination) (Oyiga et al. 2016), hampering water and nutrient uptake, and thus affecting crop growth (Meena et al. 2020). Maize is most vulnerable to salinity stress during germination and seedling establishment; however, at later stages, salinity stress results poor kernel set and reduced grain weight and number, reducing overall yield (Farooq et al. 2015). Under saline conditions, the high concentration of sodium (Na+) ions leads to unbalanced cellular homeostasis, nutrient deficiency, and oxidative stress, affecting growth and causing cell death (Ahanger and Agarwal 2017). Salinity drastically hampers photosynthesis, causing stomatal closure (Munns and Tester 2008), chlorophyll malfunctioning (Jiang et al. 2012), and disrupting the enzymatic machinery of photosynthetic apparatus (Mittal et al. 2012), and chloroplast structure (Quintero et al. 2007; Gengmao et al. 2015). Various studies have revealed that high concentrations of Na+ and Cl– ions in cell sap stimulate a lower osmotic gradient in the nutrient medium, reducing water and nutrient uptake and drastically affecting plant morphological traits (Cantabella et al. 2017; Sapre et al. 2018).

Adaptive mechanisms for salinity stress tolerance

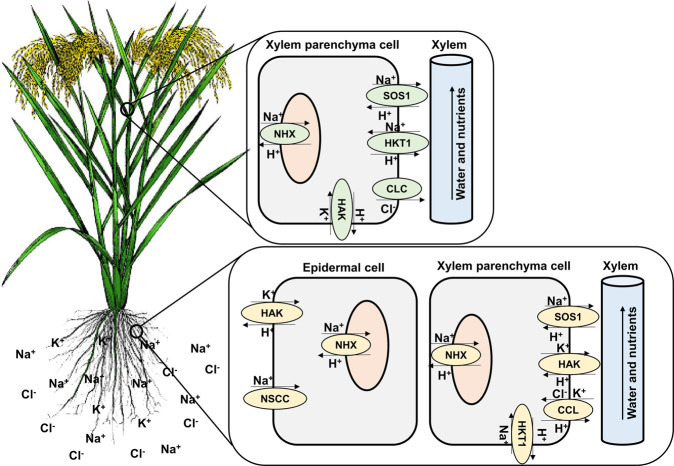

Several physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms are involved in the crop response to salt stress (Munns and Tester 2008, Jha et al. 2019) which can be classified into three main categories (Fig. 2): (1) osmotic tolerance—long-distance signals that reduce shoot growth and positively regulate the production of compatible solutes to maintain leaf expansion and stomatal conductance (Blum 2017); (2) ion exclusion—Na+ transport mechanism in roots that prevents Na+ accumulation reaching to toxic levels in leaves (Munns and Tester 2008); (3) tissue tolerance—high salt concentrations present in leaves but Na+ compartmentalize at the cellular and intracellular level (especially in vacuoles). Osmoprotectant mechanisms include proline and glycine betaine accumulation in maize (Farooq et al. 2015; Iqbal et al. 2020) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging, glycine betaine accumulation, and hormone modulation in wheat (Shahid et al. 2020). The major genes involved in salt exclusion are salt overlay sensitive (SOS) homologs (OsSOS1, OsCIPK24, and OsCBL4) in rice (Martínez-Atienza et al. 2007), TaSOS1 and TdSOS1 in wheat (Xu et al. 2008; Feki et al. 2011) and ZmNHX7 as a Na+/H+ antiporter in maize (Bosnic et al. 2018). The NHX group of tonoplast-based Na+/H+ exchangers render the vacuolar sequestration of Na+. Overexpression of OsNHX1 and OsVP1 improved salinity tolerance in rice. Similarly, several Na+ sequestration NHX genes were characterized in the vacuoles, including five NHX genes in rice (OsNHX1 to OsNHX5) (Fukuda et al. 2011), four in wheat (TaNHX1, TaNHX2, TaNHX3, and TaNHX4-B) (Brini et al. 2007; Lu et al. 2014; Sharma et al. 2020) and six in maize (ZmNHX1 to ZmNHX6) (Zörb et al. 2005). High-affinity potassium (HAK) transporters also help to induce salt tolerance; 27 HAK genes in rice and maize (Yang et al. 2014, 2020; Zhang et al. 2012), and 56 in wheat were reported (Cheng et al. 2018; Amirbakhtiar et al. 2019). Besides ionic mechanisms, phytohormone-mediated salt tolerance mechanisms are well documented in rice, wheat, and maize, such as abscisic acid, salicylic acid, and jasmonic acid in rice (Yang and Guo 2018; Quilis et al. 2008; Kurotani et al. 2015), wheat (Shakirova et al. 2003) and maize (Iqbal et al. 2020; Ahmad et al. 2019).

Fig. 2. Key players in ion homeostasis in cereals under salt stress.

Non-selective cation channels (NSCC) and high-affinity potassium (HAK) transporters provide entry points for Na+ (huge influx) and K+ in roots, respectively. The role of voltage insensitive NSCC (VI-NSCC) in Na+ uptake under salt stress has been demonstrated in rye, barley, wheat, and several other plant species. HAK transporters work to balance the augmented Na+ levels by increasing K+uptake (for Na+/K+ homeostasis). Once inside root cells, salt overlay sensitive (SOS) homologs jump in to exclude Na+ from cells. SOS1 is a Na+/H+ antiporter belonging to the cation protein antiporter family with homologs in rice (OsSOS1), wheat (TaSOS1 and TdSOS1), and maize (ZmNHX7). It is primarily involved in Na+ exclusion in roots after activation by serine-threonine kinase (SOS2) and myristoylated calcium-binding protein (SOS3) complex. Na+ accumulated in the cytosol is routed to vacuoles through another set of transporters called Na+/H+ exchangers (NHX), which guide the vacuolar sequestration of Na+. NHX transporters are well characterized in roots and leaves of rice (OsNHX1 to OsNHX5), wheat (TaNHX1toTaNHX3 and TaNHX4-B), and maize (ZmNHX1toZmNHX6). HKT are high-affinity K+ transporters involved in excluding Na+ from xylem vessels and candidate genes for salt-tolerance-related QTL in rice, wheat, and maize. The exclusion of Cl– ions is mediated by a set of transporters—cation chloride co-transporter (CCC) and chloride transporter (CLC) genes. CCC mediates the exclusion of Cl– from roots, while CLC transport Cl– and contributes to salt tolerance.

Genomics-assisted breeding for salinity stress tolerance

Genomics-assisted breeding involves genomic mapping and subsequent introgression to develop improved cultivars. Mapping quantitative trait loci (QTL) is an important approach for understanding the genetic basis of different complex traits governed by multiple genes. Salinity stress tolerance is controlled by polygenes and hence exhibits quantitative inheritance (Jha et al. 2019; Ganie et al. 2019). The availability of molecular markers, mainly microsatellites or simple sequence repeats (SSRs) and, more recently, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), facilitate mapping studies. QTL mapping and other mapping approaches, such as association mapping and Bulk-seq/QTL-seq (using extreme, i.e., low and high performing, bulks), have been used extensively to map salt tolerance associated traits, particularly in rice (Prakash et al. 2020).

Mapping major QTL: current status

Numerous minor QTL have been identified using bi-parental mapping populations and association panels, but major QTL are limited (see Tables 1 and 2). Various component traits govern salt tolerance at the seedling stage in rice, particularly root and shoot Na+ and potassium (K+) concentrations, Na+ and K+ uptake, root and shoot length, and leaf chlorophyll concentration (Van Zelm et al. 2020). At the reproductive stage, traits such as root and shoot biomass, grain and straw yield, leaf chlorophyll content, days to flowering, tiller number, and spikelet fertility are typically considered important (Hernández 2019; VanZelm et al. 2020). Several standard visual scoring methods or selection indices (based on key traits), such as the stress susceptibility index (SSI), salt tolerance score (STS), salt injury score (SIS) and salt tolerance ranking (STR) reflect overall plant growth and development, and hence can be used to classify germplasm.

Table 1.

List of QTL/genes conferring salt tolerance in major cereal crops identified during last decade.

| Parents | Population type (size) | Marker type (number) | Major QTL (linked marker) | Traits | Screening conditions | Chr | PVE % | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice (seedling stage) | ||||||||

| Jiucaiqing × IR26 | RILs (150) | SSR (135) | qSH1.3 (RM3482-RM3362) | Seedling height | 0.5% NaCl | 1 | 14.4 | Wang et al. (2012) |

| Gharib × Sepidroud | F2:4 (148) |

SSR (131) AFLP (105) |

qRFW-4b (E36-M59-5-E37-M60-3) | Root fresh weight | EC = 12 dS/m | 4 | 19.1 | Ghomi et al. (2013) |

| qSHL-5 (RM13-RM164) | Shoot length | 4 | 19.5 | |||||

| C258 × IR75862 | BC1F10 (200) | SSR (128) | qSST5 (RM161-RM3476) | Salt toxicity score | 140 mmol/L NaCl | 5 | 13.3 | Qiu et al. (2015) |

| ZGX1 × IR75862 | BC1F10 (200) | SSR (128) | qDSS11 (RM332-RM167) | Seedling survival | 140 mmol/L NaCl | 11 | 12.5 | |

| Dongnong425 × Changbai10 | BC2F2:3, (190) | SSR (137) | qSNC-12 (RM28033-RM1310) | Shoot Na+ concentration | 140 mmol/L NaCl | 12 | 17.9 | Zheng et al. (2015) |

| Bengal × Pokkali | RILs (230) | SNP (9303) | qK1.11 (S1_11529325-S1_11581799) | Shoot K+ concentration | EC = 12 dS/m | 1 | 16.1 | De Leon et al. (2016) |

| qDWT5.4 (S5_4565557-S5_4699921) | Dry weight | 5 | 12.9 | |||||

| IR29 × Hasawi | RILs (142) | SNP (384) | qSFW4.1 (id4001113-id4001932) | Shoot fresh weight | EC = 12 dS/m | 4 | 12.8 | Bizimana et al. (2017) |

| Pokkali × Bengal | BIL (292) | SSR (107) | qSHL6.5 (RM253) | Shoot length |

EC = 12 dS/m EC = 12 dS/m |

6 | 23.5 | De Leon et al. (2017) |

| qDWT2.3 (RM211) | Dry weight | 2 | 27.9 | |||||

| Jupiter × Nona Bokra | CSSL (138) | SSR (126) | qK2.1 (RM5780-RM29) | Shoot K+ concentration | EC = 12 dS/m | 2 | 10.1 | Puram et al. (2017) |

| IR29 × Hasawi | RIL (155) | SNP (145) | qRL3.1 (id3200001-id3010345) | Root length | EC = 12 dS/m | 3 | 21.9 | Rahman et al. (2017) |

| Cheniere × NonaBokra | IL (112) | SSR (116) | qDWT8.1 (RM44-RM515) | Dry weight | EC = 12 dS/m | 8 | 17.6 | Puram et al. (2018) |

| IR29 × Pokkali | RIL (148) | SNP (14470) | qSIS12 (Bin12_4.19-4.35) | Salt injury score | EC = 12 dS/m | 12 | 12.8 | Chen et al. (2020) |

| Capsule × BRRIdhan29 | F2 (94) | SSR (105) | qSPAD10.1 (RM501C-RM5806) | Chlorophyll content | EC = 12 dS/m | 10 | 15 | Rahman et al. (2019) |

| 93-11 × PA64s | RIL (132) | SNP | qRL5 (SNP5-269-SNP5-289) | Root length | 100 mmol/L NaCl | 5 | 23.7 | Jahan et al. (2020) |

| Kalajoha × Ranjit | RIL (68) | SNP (3649) | qSL9.1 (9_19034853-9_19952446) | Reduction in shoot length | 100 mmol/L NaCl | 9 | 25.4 | Mazumder et al. (2020) |

| Rice (reproductive stage) | ||||||||

| Sadri × FL478 | F2 (232) | SSR (123) | qPH1.1s (RM246-RM431) | Plant height | EC = 6–8 dS/m | 1 | 17 | Mohammadi et al. (2013) |

| qTGW8.1s (RM80-RM281) | 1000-grain weight (TGW) | 8 | 17 | |||||

| NERICA-L-19 × Hasawi | F2:3 (113) | SSR (65) | qSES11 (RM536-RM287) | SES score | EC = 6.5–9.5 dS/m | 11 | 37.2 | Bimpong et al. (2014) |

| qPH10 (RM228-RM333) | Plant height | 10 | 44.9 | |||||

| Cheriviruppu × PB1 | F2 (218) | SSR (131) | qPH1.1 (RM128-RM472) | Plant height | EC = 10 dS/m | 1 | 47.1 | Hossain et al. (2015) |

| qPF10.1 (RM6142-RM181) | Pollen fertility | 10 | 12.8 | |||||

| IR36 × Pokkali | F2 (113) | SSR (111) |

qSY3.1 RM007-RM473D |

Straw yield per plant | – | 3 | 81.5 | Khan et al. (2016) |

| PS5 × CSR10 | F2 (140) | SSR (100) | qPL-2 (HvSSR02-66-HvSSR02-68) | Panicle length | EC = 10 dS/m | 2 | 24 | Pundir et al. (2021) |

| qNaR-9 (HvSSR09-11-HvSSR09-39) | Na+ concentration in root | ECe ~ 80 mmol | 9 | 37 | ||||

| Wheat | ||||||||

| Xiaoyan 54 × Jing 411 |

RILs (182) Seedling stage |

SSR, EST-SSR (555) |

QRl-7B (Xgwm297-NP43) QSh-5A (Xgwm156.1-Xgwm328) QRkc-5B(Xgwm133.2-Xgwm274.2) |

Root length Shoot height Root K+ concentration |

Hydroponics 150 mM NaCl |

7B 5A 5B |

14.7 14.6 14.3 |

Xu et al. (2012) |

| Sakha 93 × Gemmeza 7 |

DH (139) Seedling stage |

SSR, AFLP, RFLP (325) |

Gwm368 psr126/Gwm174 |

Na+ concentration K+ concentration |

Hydroponics 150 mM NaCl |

4B 2B/5D |

17.9 29/22 |

Amin and Diab (2013) |

| Chuan 35050 × Shannong 483 |

RILs (131) Seedling stage |

DArt, SSR, EST-SSR (719) | QTdw-4B (Xgwm6-Xwmc413) | Total dry weight | Hydroponics 150 mM NaCl | 4B | 12 | Xu et al. (2013) |

| Berkut × Krichauff |

DH (152) Seedling stage |

SSR (403) | QTL (barc56/gwm186) | Cl– accumulation |

Hydroponics/field EC = 4.1–13.8 dS/m |

5A | 27–32 | Genc et al. (2013) |

| Roshan × Sabalan | RILs (154) Seedling stage | DArT/SSR (239) |

QHt-3A (wPt-8699-wPt-1119) QSfw-1A (wPt0769-wPt666776) |

Plant height Shoot fresh weight |

150 mM NaCl |

3A 1A |

12.9 13.6 |

Ghaedrahmati et al. (2014) |

| Superhead#2 × Roshan | RILs (186) | DArT/SSR (451) | QYld.abrii-1A1.1 (wPt-668205- wPt-731282), QYld.abrii-3B.1 (gwm566- wPt-730063) |

Grain yield TGW |

Field EC = 10–12 dS/m |

1A 3B |

11.0 10.3 |

Azadi et al. (2015) |

| Attila/Kauz × Karchia |

RILs (179) 5 locations |

DArT/SSR (118) |

QTL (wpt5505-Xgwm639) QTL (wpt729979-wpt664174) QTL (Xgwm540-wpt4996) |

Grain yield Plant height |

120 mM NaCl irrigation (field) EC = 11/13 dS/m |

5D 6B 5B |

12.4 10.5 |

Narjesi et al. (2015) |

| Roshan × Falat Seri82) | RILs (319) Seedling stage | DArT/SSR (730) |

QTL (wPt-798970-wPt-8303) QTL (wPt-0895-wPt-0013) |

Shoot fresh weight, chlorophyll content, root K+/Na+ content | 150 mM NaC |

3B-1 3B-2 |

19.2 12.1 |

Masoudi et al. (2015) |

| Jandaroi × AUS-14740 | F2 (112) (BSA-seedling stage) | 9K SNP |

QTL (Xm5511) QTL (Xm564) |

Leaf Na+/ K+ concentration and ratio | 100 mM NaCl |

3B 4B |

18 20–27 |

Shamaya et al. (2017) |

| WTSD91 × WN-64 | F2 (164) Seedling stage | SNPs (988) | qRNAX.7A.3/ qSNAX.7A.3 (AX-95248570-AX-95002995) | Root/shoot Na exclusion | 150 (4th), 225 (8th) 300 (12th day) mM NaCl | 7A | 11.2 18.7 | Hussain et al. (2017) |

| Xiaoyan 54 × Jing 411 | RIL (142) Seedling stage | SSR (470) | qRDW.ST-4A (Xbarc170 -Xbarc1136.2), qMRL.ST-6B (X239630-Xcfd13), qTDWR-3A (Xgwm 156.2-Xbarc324) |

Root dry weight Maximum root length Total dry weight |

150 mM NaCl |

4A 6B 3A |

>15 | Ren et al. (2018) |

| Excalibur × Kukri | DH (212) | DArT (222), SSRs (169), GBS | QG (1–5). sl-7A (X2279012.58AC), QNa.asl-7A (wmc0017), QK.asl-5A (Vrn-A1) | Growth, leaf Na+, leaf K+ | 100 mM NaCl | 7A |

14.1 11.3 28.2 |

Asif et al. (2018) |

| Roshan × Superhead | RILs (186) | DArT | QSPL.3A (wPt-3389–wPt-664504) | Spike length | EC = 12.5 dS/m | 3A | 42.1 | Jahani et al. (2019) |

| Kharchia 65 × HD 2009 | RILs (114) | SSR (133) | QSK+.iiwbr-2D (gwm261), QStn.iiwbr-4D (cfd84), QSne.iiwbr-4D (cfd84) | K+ content, tiller number, number of earheads | EC = 3.02 dS/m | 2D, 4D | >10 | Devi et al. (2019) |

| Frontana × Pasban90 | RILs (87) Seedling stage | SSR (202) | qCl.3B.SH (xwmc695-xgwm108), qPro.4B.SH (xgwm314-xgwm538), qNa.6B.CH (Xgwm70-Xbarc361) qSOD.6D.SH (xgdm108-xbarc23) | Chloride, proline, sodium, super oxide dismutase | NaCl (150 mM) | 3B, 4B, 6B, 6D | >15 | Ilyas et al. (2020) |

| Zhongmai 175 × Xiaoyan 60 | RILs (350) | 55K SNP | QPh-4B, QTkw-4B, QKw-4B, QKl/Kw-4B, QHi-4B, QKps-6A, QPh-6A, QGn-6A | Plant height, TGW, kernel length/ width, harvest index, kernels per spike, grain number | Field, salinity, (0.18%, m/m) | 4B, 6A | >10 | Luo et al. (2021) |

| Maize | ||||||||

| F63 × F35 | 161 F2:5 RILs | SNPs (3072) | QFgr1(PZE101140869-PZE101138116) and QFstr1 PZE101140869-PZE101138116 | Field germination rate, field salt tolerance ranking | Field (NaCl, 0.3% w/v adjusted), hydroponics (160 mM NaCl) | 1 | 30.4, 58.3 | Cui et al. (2015b) |

| PH6WC × PH4CV | 240 DH lines | SNPs (1317) | qSPH1 (PZE101094436 and PZE101150513.) | Plant height | Field (Na+ content 0–20 cm, 20–40 cm depth) | 1 | 31.24 | Luo et al. (2017) |

| Zheng58 × Chang7-2 | 540 RILs | SNPs (GBS) | ZmNC1 | Leaf Na+ Concentration | Glass house (100 mM NaCl) | 3 | 12.51 | Zhang et al. (2018) |

| PH6WC × PH4CV based hybrid (Xianyu335) | 209 DH lines | SNPs (1335) | qRLS1, qSLS1-2, qFLS1-2, qRFS1, qSFS1, qFFS1, qFDS1, qRLR1, qSLR1-1, qFLR1, qRFR1, qSFR1-1 & qFFR1 | Root/shoot/total lengths, and fulfill fresh weights, total dry weight, salinity index | Hydroponics (100 mM NaCl) | 1 | 21.2–63.1 | Luo et al. (2019) |

Bold indicates the tolerant parent.

Table 2.

Association studies conducted in rice, wheat, and maize over the last decade.

| Markers | Population | Traits studied | Marker-trait associations (MTAs) identified | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | ||||

| >6K custom-designed array based | 220 collected accessions from different sources | 12 traits; reproductive stage | 64 SNPs linked with different traits | Kumar et al. (2015) |

| >395K SNP | 208 accessions from the mini core collection | 11 traits | 20 QTN | Naveed et al. (2018) |

| 30K SNP | 240 temperate Japonica rice | 8 traits | 27 MTAs | Frouin et al. (2018) |

| >1101K within gene SNP | 708 accessions selected from 3K RGP | Seedling stage; multi-environment trial; 10 traits | 321 MTAs | Liu et al. (2019) |

| >112K SNP | 190 mostly Thai accessions (indica ssp.) | Flowering stage | 448 MTAs | Lekklar et al. (2019) |

| 17 million SNP | 664 cultivated varieties from 3K-RGP | Seedling stage; 7 phenotypic traits | 21 MTAs with 2 candidate genes | Yuan et al. (2020) |

| 2 million SNP | 204 accessions from Bengal and Assam Aus Panel (BAAP) | Seedling stage hydroponic and soil-based evaluation; 10 traits | 97 and 74 MTAs in hydroponic and soil-based evaluation respectively | Chen et al. (2020) |

| >21K SNP | 179 Vietnamese landraces | Seedling stage; 9 traits | 26 MTAs | Le et al. (2021) |

| >33K SNP | 155 varieties, Changi Genetic Resources Center, IRRI | 8 traits | 27 MTAs | Nayyeripasand et al. (2021) |

| Wheat | ||||

| 90K SNP array; | 150 winter and facultative genotypes | 13 traits | 187 SNP linked to 37 MTAs | Oyiga et al. (2018) |

| 90K SNP array; >41K SNPs | 100 bread wheat varieties | Na+ exclusion/accumulation | 9 linked SNP | Genc et al. (2019) |

| 660K SNP array | 191 accessions from diverse sources | 8 phenotyping traits | 389 SNP for 11 MTAs | Hu et al. (2021) |

| Maize | ||||

| Sequencing of ZmHKT1;5 gene | 54 diverse maize inbred lines | Survival rate | 2 SNP | Jiang et al. (2018) |

| >580K SNP | 399 inbred lines | Seedling stage; 6 traits | 57 SNP | Sandhu et al. (2020) |

| Maize SNP50 array; >55K SNP | 419 inbred lines | Seedling stage; shot Na+ content | 1 candidate gene | Cao et al. (2020) |

| >55K SNP | 348 inbred lines | Seedling stage; 27 traits | 104 MTAs | Luo et al. (2021) |

| GBS; >11 million SNPs | 266 inbred lines | Seedling stage; metabolite biomarkers | 10 candidate genes | Liang et al. (2021) |

Bulk segregant analysis (BSA)

BSA-based approaches are quick and effective for mapping major QTL, as evident in rice (Michelmore et al. 1991; Choudhary et al. 2019). Tiwari et al. (2016) performed BSA-based mapping using 6068 polymorphic SNPs in CSR11 and MI48 based recombinant inbred line (RIL) populations to identify 21 QTL associated with salt tolerance. Recently, Wu et al. (2020) performed BSA-based QTL mapping to map the loci qST1.1 contributing to salt- tolerance in ‘Sea Rice 86’. Sun et al. (2019) used a QTL-seq approach and two extreme bulks from a segregating population of ‘Changmaogu’ (salt-tolerant) and ‘Zhefu802’ (salt-susceptible) to identify six candidate genes associated with salt tolerance on rice chromosome 1. They identified OsPP2C8 (Os01g0656200) as a candidate gene with sequence polymorphism in ORFs, differentially expressed at the seedling stage. Lei et al. (2020) mapped a major QTL qRSL7 for relative shoot length on chromosome 7 using a QTL-seq approach in an F2:3 population (‘IR36’ × ‘Weiguo’). Furthermore, Lei et al. (2020) identified a candidate gene Os07g0569700 (OsSAP16) using an RNA-seq and sequence variation approach for salt tolerance. In wheat, Shamaya et al. (2017) conducted BSA using 9K SNP markers to map two major loci for third leaf Na+ concentration on chromosomes 3B and 4B, with the gene on 4B likely to be a high-affinity K+ transporter (HKT1;5-B1).

QTL mapping: Classical approach

Rice

QTL mapping for salt tolerance at the seedling and reproductive stages in rice used mapping populations derived from a cross between salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive genotypes (Singh et al. 2007). Several salt-tolerant rice genotypes, including ‘Nona Bokra’ (Puram et al. 2018), ‘Jiucaiqing’ (Wang et al. 2012), ‘CSR27’ (Pandit et al. 2010), ‘Pokkali’ (Chen et al. 2019), ‘Gharib’ (Ghomi et al. 2013), ‘Changbai10’ (Zheng et al. 2015), ‘Capsule’ (Rahman et al. 2019), ‘Changmaogu’ (Sun et al. 2019), ‘Kalajoha’ (Mazumder et al. 2020), ‘Sea Rice 86’ (Wu et al. 2020) and ‘Hasawi’ (Rahman et al. 2017), have been used to map traits associated with seedling stage salt tolerance (Table 1).

‘Hasawi’ (Bimpong et al. 2014), ‘Pokkali’ (Khan et al. 2015), and ‘CSR10’ (Pundir et al. 2021) were used as the tolerant parent for mapping salt-tolerance associated traits at the reproductive stage. ‘Pokkali’ is salt-tolerant at the seedling and reproductive stage (Table 1). QTL have been identified in the mapping populations using QTL mapping or a whole-genome resequencing-based QTL-seq approach (Krishnamurthy et al. 2020). In rice, ‘Saltol’ on chromosome 1 is the most commonly occurring QTL governing salt tolerance at the seedling stage (Babu et al. 2017b). The ‘Saltol’ genomic region has been well characterized in several landraces and genotypes (Manohara et al. 2021). A major QTL, qSSISFH8.1, on chromosome 8 (flanked by HvSSR08-25 and RM3395) governing SSI for spikelet fertility under salinity stress at the reproductive stage can be used to impart salt tolerance (Pandit et al. 2010; Pundir et al. 2021). Identified QTL on chromosomes 2, 3, 4, 9, 10, and 11 at the seedling and reproductive stage indicate that these chromosomes are relatively more important for harboring genes for seedling and reproductive stage salinity tolerance in rice (Table 1).

Wheat

QTL mapping efforts in wheat identified >500 QTL (distributed over 21 chromosomes) for salinity tolerance associated traits, with a few dozen major QTL explaining more than 10% of the phenotypic variance (Gupta et al. 2020; Singh et al. 2021). Since 2011, 16 QTL mapping studies have been published, most focusing on salt tolerance at the seedling stage (Table 1). Hussain et al. (2017) reported a major QTL, qSNAX.7A.3, for shoot dry weight, a commonly used direct measure of salinity stress tolerance. Asif et al. (2018) detected three major QTL, QG(1–5), asl-7A (relative growth rate), QNa.asl-7A (leaf Na+ concentration), and QK.asl-5A (leaf K+ concentration), in an ‘Excalibur’ × ‘Kukri’ doubled haploid (DH) population. QK.asl-5A was in the vicinity of the vernalization response gene (Vrn-A1), but QG(1–5).asl-7A was the prominent QTL, present in six of 44 Australian bread and durum wheat cultivars. Devi et al. (2019) identified 25 QTL under sodic conditions using RILs derived from ‘HD2009’ and ‘Kharchia 65’. The study revealed the linkage of SSR marker gwm 26 for K+ content (QSK+.iiwbr-2D) and cfd 84 for tiller number (QStn.iiwbr-4D) and earhead number (QSne.iiwbr-4D). Ilyas et al. (2020) mapped 60 QTL; four (for total chlorophyll, water potential, and Na+ content) were located on chromosome 6B in the vicinity of gwm70 and Xbarc361 markers; hence, chromosome 6B is a good source of salinity stress tolerance in wheat. Recently, Luo et al. (2021) used a wheat 55K SNP array to map 90 stable QTL for 15 agronomic traits in a ‘Zhongmai 175’ × ‘Xiaoyan 60’ RIL population screened under low and high levels of salt stress at the adult stage. Eight QTL from four QTL clusters were validated in natural populations, and competitive allele-specific PCR (KASP) markers were designed for three QTL clusters. Hence, many major QTL are now available in wheat (more than maize but fewer than rice) (Table 1). In wheat, chromosomes 3A, 5B, and 6B possess QTL for salt-tolerance-associated traits at the seedling and adult stage (Table 1), which are relatively anticipated to harbor multi-stage tolerance.

Maize

There are limited QTL mapping studies on salinity stress tolerance in maize (Table 1). Two major QTL, QFgr1 and QFstr1, for field germination rate and field tolerance ranking, respectively, were mapped on chromosome 1 using ‘F63’ × ‘F35’ based RILs phenotyped under saline field conditions. Nine conditional QTL for shoot fresh weight, tissue water content, shoot Na+ concentration, shoot K+ concentration, and shoot K+/Na+ ratio were mapped on chromosomes 1, 3, 4, and 5 (Cui et al. 2015b). Luo et al. (2017) identified a major QTL for plant height, qSPH1 (with phenotypic variance of 31%), on chromosome 1 under saline conditions. The study also identified a major QTL for a plant-height-based salt tolerance index on the same chromosome and two candidate genes, GRMZM2G007555 and GRMZM2G098494, that code for ion homeostasis regulation likely associated with salt tolerance. A major QTL, ZmNC1 conferring leaf Na+ concentration, was reported on chromosome 3 in RILs derived from crossing ‘Zheng58’ and ‘Chang7-2’ (Zhang et al. 2018). The authors also performed transcriptomic analysis to identify a plasma-membrane-localized class I HKT ion transporter (ZmHKT1) as a putative candidate gene for ZmNC1. Later, 65 QTL were mapped for biomass-related traits under salinity stress, with 13 major QTL (for nine salt-tolerance-related traits) on chromosome 1, explaining more than 21% of the phenotypic variation (Luo et al. 2019). Hence, the 17 QTL identified on chromosome 1 can be targeted for introgression to develop salt-tolerant maize cultivars.

Association mapping to identify candidate genes for salinity stress tolerance

The exploitation of historical recombination events through association mapping (AM) or genome-wide association studies (GWAS) has been instrumental in identifying genomic regions responsible for specific traits in various crop species, and salt tolerance is not an exception (Table 2). GWAS has been used widely in cereal crops (Gupta et al. 2014) to identify genes related to abiotic stress tolerance (Kumar et al. 2015; Frouin et al. 2018; Gupta et al. 2020). More GWAS studies for salinity stress tolerance have been conducted in rice than wheat or maize, as rice is the most salt-sensitive (Table 2).

Rice

In an AM panel of 220 rice accessions, mostly indica type, Kumar et al. (2015) identified novel salt-tolerance-related marker-trait associations (MTAs) on chromosomes 1, 4, 6, and 7. Another AM panel of 208 rice accessions from the mini core collection was used (Naveed et al. 2018) to identify 20 MTAs associated with 11 salt-tolerance-related traits. Mild seedling stage salinity stress tolerance was used to map associated genes in a panel of 235 temperate japonica rice accessions (Frouin et al. 2018). After the release of the 3K rice genome sequence, Batayeva et al. (2018) used 203 temperate japonica rice accessions to identify 26 MTAs for nine salt-tolerance-related traits at the seedling stage. Most of the QTL were located close to the genes governing kinase and calcium signaling and metabolism. In another study using a large panel of 708 rice accessions, five known (OsSUT1, OsMYB6, OsHKT1;4, OsGAMYB, and OsCTR3) and two novel (LOC_Os02g49700 and LOC_Os03g28300) genes were significantly associated with yield and related traits under salinity stress at the seedling stage (Liu et al. 2019). A panel of 104 Thai rice accessions of indica rice was evaluated to identify candidate genes related to salinity stress tolerance at the flowering stage; the genes were mainly distributed on chromosomes 1, 2, 8, and 12 (Lekklar et al. 2019). A study using a large panel of 664 accessions from the 3K Rice Genome Project and high-density genotypic data of 17 million SNPs identified 21 QTL with two candidate genes (OsSTL1 and OsSTL2) confirmed via sequence analysis (Yuan et al. 2020). An evaluation of accessions under hydroponic and soil media identified 97 and 74 QTL, respectively, with 11 QTL common to both (Chen et al. 2020). The most significant QTL on chromosome 1 harbored two post-translational modification genes, OsSUMO1 and OsSUMO2. Warraich et al. (2020) identified genomic locations responsible for several salt-tolerance-associated traits, including Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ content, in leaves and stems at the reproductive stage. Recently, Nayyeripasand et al. (2021) identified 29 genomic regions for salinity stress tolerance in a panel of 155 rice varieties, including two and three novel candidate genes on chromosomes 8 and 1, respectively. The above GWAS studies involved different mapping panels, which should help better understand the mechanisms of salinity stress tolerance in rice.

Wheat

Using natural recombination events, a panel of 150 wheat accessions was genotyped with the 90K SNP chip identified 37 QTL for salt-tolerance-related traits at three growth stages, i.e., germination, seedling, and adult (Oyiga et al. 2018). In another mapping panel of 100 bread wheat, seven SNPs were associated with genes (four candidate genes) linked to Na+ accumulation/exclusion. Hu et al. (2021) conducted GWAS at the adult plant stage using a panel of 191 accessions to establish 11 QTL for salt-tolerance-related traits. Significant SNPs were validated using two RIL populations.

Maize

Fewer studies on salinity stress tolerance have been conducted in maize than rice or wheat (Table 2). In a candidate-gene-based AM approach, a panel of 54 diverse Chinese inbred lines was used to find associations with sequence variation (two SNPs within the coding region) in the ZmHKT1-5 gene for salinity stress tolerance (Jiang et al. 2018). In another study, 57 SNPs had significant associations with early-vigor-related traits, with 40 associated with shoot-biomass-related traits (Sandhu et al. 2020). Cao et al. (2020) genotyped a panel of 419 inbred lines with 55K chip-based SNPs to reveal two closely located SNPs significantly associated with shoot Na+ content (candidate gene ZmNSA1 conferring shoot Na+ content variation). Recently, Liang et al. (2021) conducted metabolic GWAS to identify 37 metabolite biomarkers and 10 candidate genes for salt-induced osmotic stress tolerance.

Genomic selection for salinity stress tolerance in cereals

Genomic selection (GS) is an efficient tool for assessing the breeding value of a genotype based on its sequence information (Goddard and Hayes 2007). It is a practical breeding tool for selecting superior genotypes among the available diversity and is a better solution than marker-assisted selection (MAS), especially for complex traits such as salinity stress tolerance (governed by several genes and metabolic pathways), due to the inclusion of minor genes for determining the worth of the genotype. As far as rice, wheat and maize are concerned, there have been no systematic GS efforts for salinity stress tolerance. However, a haplotype-based GS approach can be used to charter customized varieties suitable for a particular region with a specific stress type and consumer quality preferences (Sinha et al. 2020). The publicly available 3K rice genome sequence information can be used to predict haplotypes suitable for salinity stress and design a breeding strategy.

Transcriptomics for salinity tolerance

Advances in high-throughput methods for next-generation sequencing offer a better understanding of salinity stress tolerance in crops by identifying salt-responsive genes using genomics and transcriptomics (Egan et al. 2012; Duarte-Delgado et al. 2020; Kashyap et al. 2020). Transcriptomics can identify stress-associated essential transcripts, the transcriptional structure of genes, their functional pathways, and other post-transcriptional modifications (Wang et al. 2009). RNA-seq and microarray are gene expression approaches (Table 3) with the former being more popular due to its precise transcript measurement ability (Wang et al. 2009).

Table 3.

List of studies for transcriptomics approaches on salinity stress tolerance in rice, wheat and maize.

| Genotype | Tissue | Experimental conditions | Technique | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | |||||

| Oryza coarctata | Leaves and roots | Control, 450 mM NaCl, 700 mM NaCl, fully submerged plant in RO water, fully submerged plant in 450 mM NaCl | Deep transcriptome sequencing | 15,158 genes are differentially expressed under salinity mostly belonging to MYB, bHLH, AP2-EREBP, WRKY, bZIPand NAC classes of TFs | Garg et al. (2014) |

|

Pokkali (tolerant) IR64 (sensitive) |

Leaves and roots | 200 mM NaCl treatment (14-day-old seedlings | Whole-genome transcriptomics (WGT) | 507 differentially expressed genes, mostly bHLH and C2H2 TF families; terpenoid and wax metabolism genes upregulated in tolerant line | Shankar et al. (2016) |

| Dongxiang wild rice (Oryza rufipogon Griff.) | Leaves and roots | 200 mM NaCl treatment on 14-day-old seedlings for 12 days | WGT | 6867 DEGs in leaves and 4988 DEGs in roots. Most belonging to zinc finger proteins, NAC, bZIP, AP2/ERF & MYB TFs family genes; potassium transporters OsHKT1 and OsHKT7 were downregulated | Zhou et al. (2016) |

| Chilbo | Leaves | 250 mM NaCl treatment on 14-day-old seedlings for 12 days | WGT | 962 upregulated genes identified, mostly belonging to MYB family and ZF family of genes regulating sugar metabolism and amino-acid synthesis | Chandran et al. (2019) |

|

Dongdao-4 Jigeng-88 |

Leaves | 0 mM Na+ (10 mM Na2CO3 and 20 mM NaCl) for 1 day and then 60 mM Na+ (10 mM Na2CO3 and 40 mM NaCl) | RNA-seq | 3523 and 4066 DEGs responding to several gene families, involved in functions related to jasmonic acid, organic acid metabolism, iron homeostasis, phenylpropanoid and gibberellic acid synthesis | Li et al. (2020) |

| Wheat | |||||

| SR3 (tolerant) and JN177 | Root | Half-strength Hoagland solution with 340 mM NaCl at 3-leaf stage | Microarray, semi-quantitative RT-PCR (sqRT-PCR, qRT-PCR) | Upregulated: GST (ta_07226) and diacylglycerol kinase (ta_07191) encoding gene, | Liu et al. (2019) |

| SR3 (tolerant) | Shoots and roots | Hydroponic, 200 mM NaCl for 0-24 h at 3-leaf stage | Microarray, RT-PCR | TaMYB73 upregulated in roots and downregulated in leaves | He et al. (2012) |

| SN6306 | Leaves | MS agar medium with 0.4% NaCl for 2 days | qRT-PCR | Overexpression of TaRUB1 in transgenic Arabidopsis improved stress tolerance | Zhang et al. (2013) |

| Berkut, Krichauff, Gladius and Drysdale | Leaf sheath | First 0 and 75 mM NaCl, and second 1-100 mM NaCl (3-day stress) | Microarray analysis, qRT-PCR | Upregulated 39 genes associated with cellular and metabolic processes, cell organization and biogenesis; at 100 mM, 47 and 96 genes upregulated in Drysdale and Krichauff, respectively | Takahashi et al. (2015) |

| Bezostaja (sensitive) and Seri‐82 (tolerant) | Roots | Controlled condition, liquid Murashige and Skoog (MS) with 200 mM NaCl for 48 h | microRNA‐microarray, stem-loop reverse transcription,qRT‐PCR | 16 novel salt-stress associated miRNAs in roots, upregulated: hvu‐miR5049a, ppt‐miR1074, and osa‐miR444b.2 in sensitive line | Eren et al. (2015) |

| Altay2000 and UZ-11CWA-8 (tolerant) and Bobur (sensitive) | Third leaves | Hydroponics system with an increment of 50 mM NaCl for 3 days, and 150 mM continued upto 24 days | GWAS, RT-qPCR | Upregulated: TraesCS6A01G336500.1, TraesCS4B01G254300.1, TaABCF3 transporter genes | Oyiga et al. (2016, 2019) |

| Arg (tolerant) and Moghan3 (sensitive) | Roots of 3weekold seedlings | Green house; half-strength Hoagland solution with 150 mM NaCl for 12 h | RNA-seq, qRT-PCR,MapMan | Upregulated: ABC transporter gene Ta. ABAC15, 29 NAC genes, and 48 MYB TFs; Ta.ANN4, Ta.ACA7 and Ta.NCL2 genes control cytosolic calcium level increased under salt stress | Amirbakhtiar et al. (2019) |

| Qingmai 6 (tolerant) | Shoots and roots (two-weeks old seedlings) | 150 mM NaCl, and combination with 100 μM ethylene precursor ACC, and with 150 μM ethylene signaling inhibitor 1-MCP for 3, 6, 12, and 24 h | RNA-seq | Upregulated: TaCYP450 under stress; six genes played a role in ethylene dependent salt stress | Ma et al. (2020) |

| Chinese Spring (Triticum aestivum) | Mature leaves, roots, seedlings (30 days) | Half-strength Hoagland solution with 100 mM NaCl from germination to 30 days | RNA-seq,qRT-PCR | Upregulated: LEA, dehydrin and potassium transporter genes in roots, and sodium/cation exchanger and aquaporin genes in shoot | Bhanbhro et al. (2020) |

| Zentos (tolerant) and Syn86 (sensitive) | Leaves | Hydroponics system with 100 mM NaCl; salt stress started 3 days after transplanting | RNA-seq, RT-qPCR | Strongest salt-responsive gene TraesCS2A02G395 000. Few genes related to ABC transport, Na+/ Ca2+ exchange might play a role to exclude Na+ | Duarte-Delgado et al. (2020) |

| Kharchia Local | Roots of 6-day-seedling | Growth chamber, hyroponics, 15 dS/m for 3 days with 5 dS/m salinity daily increment, combination NaCl: CaCl2: Na2SO4 (2:1:1) for salinity treatment | RNA-seq, qRT-PCR | Upregulated genes encoding expansin, xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase, dehydrins, peroxidases, and a few TFs WRKY, MYB, NAC, bHLH, AP2/ERF | Mahajan et al. (2020) |

| Luyuan502 | 2-weeks-old seedlings | Field with 0.3–0.7% salt; 150 mM NaCl for 2 weeks | RNA-seq, qRT-PCR | Upregulated ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTORs (ERFs) (TaERF1, 2, 3, 4, and 6) decreased response of ethylene | Ma et al. (2021) |

| Jimai22 (tolerant) and Yangmai20 (sensitive) | Fourth leaves | Greenhouse; 100 mM NaCl for a week | RNA-seq, qRT-PCR | Upregulated genes encoding flavonoid 3′-mnooxygenase, HSP, cytochrome P450, zinc finger proteins, NAC, and WRKY. Co-expression of glutathione S-transferase (GSTU6) under salinity and drought stress | Dugasa et al. (2021) |

| Maize | |||||

| G.S. 46 | Leaf number 4 of 14-day-old plants | 2 mM KCl and1mM CaCl2 for 6 h and 15 mM Ca (NO3) for 2 h. (7 days after salination) | Real-time PCR | ROS scavenging more pronounced in young cells and comparatively reduced in older cells under salt stress. Ascorbate peroxidase and superoxide dismutase significantly higher in NaCl treatment. | Kravchik and Bernstein (2013) |

| B73 maize seedling | Leaf (2 h after NaCl treatment) | 200 mM NaCl | RNA-seq,qRT-PCR | Upregulated genes encode oxidoreductase, peroxidase, antioxidant, transcription regulator activities, ERFs, MYBs, b-carotene hydroxylase, and 9-cis- epoxy carotenoid dioxygenase undersalt stress | Li et al. (2017) |

| 242 maize inbred lines | Leaf (7 days after 220 mM NaCl treatment) | 220 mM NaCl treated | RNA-seq, qRT-PCR assay | L87, a salt-tolerant maize inbred line had higher ROS-related enzyme activities of superoxide dismutase, peroxidase, ascorbate peroxidase, catalase, SnRK2 (ABA), and WRKY than salt-sensitive line | Wang et al. (2019) |

| P138 (sensitive) and 8723 (tolerant) | Seedling (10 days after stress) | 180 mM NaCl (3 leaf stage) | qRT-PCR | Exogenous application of glycine betaine alleviates damaging effect of salt stress through the upregulation of ion balance, reactive oxygen scavenging mechanism, signal transduction activation and MYB and NAC TF families. | Chen et al. (2020) |

| L2010-3 (tolerant) BML1234 (sensitive) | Seedlings (3-daytreatment) | 150 mM NaCl | RNA-seq | Salt stress upregulated genes reported for Aux/IAA, SAUR, CBL-interacting kinase, ABA signal pathway, WRKY, bZIP, and MYB. | Zhang et al. (2021) |

| B73 | Endosperm and embryo tissue after 6 h of treatment | 200 mM NaCl-treated (germination) | Short-read RNA (srRNA) seq | Alternative splicing could be the more dominant regulatory mechanism in early salt-stress responses. The ABA biosynthesis gene, GRMZM2G127139 ABA1/LOS6/ZEP, was consistently repressed and one ABA-responsive gene, GRMZM2G162659 (EM1), was upregulated | Chen et al. (2021) |

Rice

Kumari et al. (2009) first reported 1,194 salinity-regulated cDNA between two contrasting genotypes, ‘IR64’ and ‘Pokkali’. The latter exhibited enhanced gene expression in the GST, LEA, CaMBP V-ATPase, and OSAP1 zinc finger protein families. Later, in transcriptomic studies involving ‘IR64’ and ‘Pokkali’ under salt stress, Shankar et al. (2016) reported that the upregulation of transcripts was involved in wax and terpenoid metabolism. Whole-genome resequencing and transcriptome analysis of ‘Sea Rice 86’ identified several candidate genes for salt adaptation (Chen et al. 2017). Li et al. (2018) concluded that ‘Pokkali’ (tolerant) has more stable mRNA and can stably load mRNA on polysomes during salt stress than ‘IR29’ (sensitive). Chandran et al. (2019) used RNA-seq based transcriptomic analysis in japonica rice cultivar ‘Chilbounder’ screened under stress and non-stress conditions to identify 447 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), which were mainly involved in carbohydrate and amino-acid metabolic processes. Recently, Xie et al. (2021) reported that the AP2/EREBP-HB-WRKY cascade is activated by stress, imparting melatonin-mediated salt tolerance in rice.

Wheat

Numerous transcriptomics studies have been conducted in wheat using different plant parts (roots, shoots, both or total plant) to understand salt stress tolerance (Table 3). Diacylglycerol kinase encoding gene, signal transduction module gene, and GST were upregulated for stress tolerance in wheat (Liu et al. 2012). Under salt stress, the salt-stress tolerant gene, TaMYB73, was upregulated in roots but downregulated in leaves. However, overexpression of the gene in Arabidopsis improved stress tolerance (He et al. 2012). Mahajan et al. (2020) found that root-growth-enhancing genes encoding expansin, xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase, dehydrins, and peroxidases improve salt stress tolerance. Additionally, the study identified 10,805 unigenes in ‘Kharchia Local’ roots at anthesis, and WRKY, MYB, NAC, bHLH, AP2/ERF transcription factors (TFs) were upregulated during salt stress. For the first time, Amirbakhtiar et al. (2019) identified 26,171 novel transcripts from the roots of ‘Chinese Spring’ seedlings using RNA-seq. Under stress conditions, Ta.ABAC15, an ABC transporter gene, was significantly upregulated. Cytosolic-calcium-level controlling genes Ta.ANN4, Ta.ACA7, and Ta.NCL2,29 NAC genes, and 48 MYB TFs also increased under salt stress. Besides differentially expressed TFs, miRNAs also contribute to stress tolerance, regulating transcription and translation. In wheat roots, 16 novel salt-stress-associated miRNAs were identified. Stress-responsive miRNAs, athmiR5655, osamiR172b and osamiR444b.2, regulated TFs, bHLH135like, AP2/ERBP, and MADS box, respectively (Eren et al. 2015). Duarte-Delgado et al. (2020) found 50 calcium-binding genes and 18 xyloglucans:xyloglucosyl transferase (cell wall genes) that reduce osmotic stress; subgenome D had the most (35.8 ± 1.7%) salt-responsive genes, with TraesCS2A02G395000 the strongest salt-responsive gene. Ma et al. (2020) reported the upregulation of TaCYP450 and six ethylene-dependent genes during salt stress. Upregulation of genes associated with LEA, dehydrin, and potassium transportation, and sodium/cation exchange and aquaporin in roots and shoots, respectively, enhanced salt stress tolerance (Bhanbhro et al. 2020). A reduction in ethylene sensitivity enhances salt tolerance. Upregulation of nine novel ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTORs (ERFs) (TaERF1, 2, 3, 4, and 6) reduced ethylene sensitivity and improved salt tolerance in wheat (Ma et al. 2021).

Maize

In maize, a reasonable number of transcriptomics studies are available (Table 3). Using RNA-seq analysis, Li et al. (2017) reported 1661 DEGs between the salt stress and control treatments at the seedling stage, which were associated with hormone metabolism, signaling, TFs, fatty acid biosynthesis, and lipid signaling. Chen et al. (2020) reported 219 upregulated and 153 downregulated DEGs in salt-sensitive and tolerant lines, respectively, which were associated with ion homeostasis, strong signal transduction activation, and increased ROS scavenging and different TFs (MYB, MYB-related, AP2-EREBP, bHLH, and NAC families). Similarly, Zhang et al. (2021) identified 459 DEGs, of which Aux/IAA, SAUR, and CBL-interacting kinase reportedly regulate salt tolerance. In addition, WRKY, bZIP, and MYB TFs act as regulators in the salt-responsive regulatory network of maize roots. Comparing transcriptomics studies in wheat, maize, and rice revealed some common TF families, such as WRKY, MYB, AP2/ERF, and NAC, important for imparting salinity stress tolerance (Table 3). These TFs maintain cellular homeostasis and osmotic balance in plants by regulating the expression of salt-stress responsive genes and need to be explored to understand their specific modes of action.

Proteomics for salinity stress tolerance

Proteomics helps to capture insights into salt-stress tolerance by identifying protein modulations and pathway modifications (Parvaiz et al. 2016). Proteomics/metabolomics studies for salt tolerance have been mostly conducted in wheat followed by maize and rice (Table 4).

Table 4.

Details of studies for proteomics/metabolomics approaches on salinity stress tolerance.

| Genotype | Tissue and developmental stage | Experimental conditions | Technique | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | |||||

| 38 rice genotypes | Roots | 43 mM NaCl applied on14-day-old seedlings | H-NMR spectroscopy | Accumulated allantoin and glutamate; Decreased glutamine and alanine. | Nam et al. (2015) |

| OsDRAP1 gene overexpressing line of Nipponbare | Leaves at 3-leaf stage | 120 and 150 mM NaCl after 14 days and kept for 7 days | LC-MS/MS analysis | Increased expression of proline, valine, several organic acids (phosphoenolpyruvic acid, glyceric acid, ascorbic acid) and several secondary metabolites | Wang et al. (2021) |

| A highly salt-sensitive Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica (rice variety 02428) | Leaves at 3-leaf stage | Control, 100 mM NaCl, 10 μM melatonin, 100 mM NaCl + 10 μM melatonin | UPLC and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) | The exogenous application of melatonin in increased salt tolerance. Transcriptomics study indicated that melatonin-mediated pathway contributed salt tolerance specifically AP2/EREBP-HB-WRKY transcriptional cascade and phytohormone (auxin and ABA). Furthermore, 64 metabolites including amino acids, organic acids, and nucleotides were found more in plants treated with salt+melatonin. | Xie et al. (2021) |

| Wheat | |||||

| Wheat cv. Keumgang | Chloroplasts from fully developed leaves; t 12- day-old seedlings | Sandy soil; 150 mM NaCl for 1, 2 and 3 days | Extraction: trichloroacetic acid (TCA)/acetone; linear quadruple trap-Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (LTQ-FTICR) hybrid MS | Upregulated cytochrome b6–f (Cyt b6–f), germin-like-protein, c-subunit of ATP synthase, glutamine synthetase, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, S-adenosyl methionine synthase and carbonic anhydrase. Downregulated (day 1) but upregulated (days 2/3) proteins eIFs 5A-1/2 and 5A-3 subunits, photosystem I reaction center subunits II and IV, germin-like-protein and uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase | Kamal et al. (2012) |

| Chinese Spring (CS) and amphiploid (tolerant) | Mitochondria of shoots and roots; seedlings | Hydroponic system with 200 mM NaCl gradually on 1,2,3, and 4 days after sowing for 7 weeks. | Extraction: 100% acetone for leaf and TCA/acetone for root; digestion: gel-bound trypsin; quantification: TOF/TOF | Manganese SOD, serine hydroxymethyl transferase, aconitase, malate dehydrogenase, and β-cyanoalanine synthase were expressed higher in amphiploid. Glutamate dehydrogenase and aspartate aminotransferase upregulated in shoots but downregulated in roots. | Jacoby et al. (2013) |

| Roshan (tolerant) and Ghods (sensitive) | Leaves; 4-leaf stage seedlings | Hoagland solution with 200 mM NaCl for 17 days. | MALDI TOF-TOF-MS | Rubisco activase, Rubisco large and small subunits, chloroplastictrios phosphate isomerase, cytosolic malate dehydrogenase were upregulated | Maleki et al. (2014) |

| T349 and T378 transgenic line with GmDREB1 gene (maize promoter) | First expanded leaves; 10 days older seedlings | Growth chamber; Kimura B nutrient solution with 300 mmol/L NaCl to 10-day-old seedlings for 7 days | Extraction: TCA/acetone; digestion: In-gel with trypsin; quantification: MALDI-TOF MS analysis | Upregulated osmotic stress-associated proteins, methionine synthase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and oxidated stress associated protein glutathione transferase, NADP-dependent malic enzyme and 2-cys peroxiredoxin BAS1 | Jiang et al. (2014) |

| Duilio (Triticum durum) | Leaf (5-day-old seedling) | Hydroponics-two salinity levels (100 and 200 mmol/L)-5-day-old seedlings for 10 days | Orbitrap elite hybrid linear ion trap–Orbitrap mass spectrometer | Upregulated: proteins associated with energy production, signal transduction, and plant defense | Capriotti et al. (2014) |

| T. monococcum | Leaves; seedlings | Hoagland solution with 80, 160, 240, and 320 mM NaCl for two days | Extraction: Urea; labeling: 2-D gel with Coomassie brilliant blue labeling dye; digestion: trypsin; quantification: MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS | Upregulated: Cu/Zn SODs, GSTs, DHNs and LEA; 64 unique DAPs; Biomarkers for salt stress response and defense: cp31BHv, betaine-aldehyde dehydrogenase (BADH), cytosolic (GS1), Cu/Zn SOD, MAT3, leucine aminopeptidase 2, and 2-Cys peroxiredoxin BAS1 | Lv et al. (2016) |

| Enterobacter cloacae SBP-8 bacteria inoculated wheat cv., C-309 | Whole plant; seedlings | Hoagland solution with 200 mM NaCl for 15 days after germination | Extraction: TCA/acetone; digestion: trypsin; quantification: liquid chromatography | Upregulated: cell wall strengthening and cell structure protecting proteins such as tubulin, profilin, retinoblastoma, Casparian strip membrane protein), xyloglucan endotransglucosylase, ion transporter (eg. malate transporter), metabolic pathway and protein synthesis | Singh et al. (2017) |

| Jimai 19 (sensitive) and Han 12 (tolerant) | Roots; seedlings | Growth chamber; Hoagland solution with 350 mM NaCl for 4 days | iTRAQ with isobaric label; validation: RT-PCR; transgenic plant Arabidopsis | Three salt-tolerant genes TaPPDK, TaLEA1 and TaLEA2 associated with PPDK, LEA1 and LEA2 proteins, respectively | Jiang et al. (2017) |

| Bobwhite | Roots and leaves; 2-week-old seedlings | Salt, NaHCO3: Na2CO3 (1:1 M) to create stress 50 mM for 2days | Extraction: TCA/acetone; digestion: trypsin; validation: qRT-PCR | Upregulated in roots: 5 SODs, 3 malate dehydrogenases, dehydrin proteins, and a V-ATPase protein; upregulated in leaves: 2 Cu/Zn SODs, LEA protein and DHN proteins | Han et al. (2019) |

| Chinese Spring | Seeds | Hoagland solution with 150 mM NaCl to seeds for 3days | Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer; validation: qRT-PCR | Upregulated 207 DEPs | Yan et al. (2020) |

| Qingmai 6 (salt tolerant) | Shoot and root; 2-week-old seedlings | Water with 150 mM NaCl, and same combined with 100 μM ethylene precursor ACC, and 150 μM ethylene signaling inhibitor 1-MCP for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h | Shotgun (Orbitrap Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer); validation: Western blot | Upregulated DAPs: ribosomal proteins (RPs), nucleoside diphosphate kinases (CDPKs), transaldolases (TALs), beta-glucosidases (BGLUs), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylases (PEPCs); proteins for metabolism played role in salt response in wheat shoots. | Ma et al. (2020) |

| Zhongmai 175 | Leaves; seedlings | 200 mM NaCl solution at 3-leaf stage for 4 days | Quantification: label-free data-independent mass spectrometric; validation: qRT-PCR | Upregulated: 117 DAPs associated with Calvin cycle, amino-acid metabolism, carbon and nitrogen metabolism, transcription and translation and antioxidation. | Zhu et al. (2021) |

| Dan-4589 | Leaves and roots | Greenhouse; Hoagland nutrient solution with 80 mM salt mixutre: NaCl and Na2SO4 (9:1) for 15 days |

Metabolomics GC-TOF-MS analysis with Pegasus 4D TOF MS |

Increased gluconeogenesis associated metabolites (in leaves), Glc, 3-PGA, G6P, F6P, Pyr and PEP, and Glu, AGBA, Ala, Asp, Gly, Thr, Ser, Val, Pro associated with glycolysis and amino-acid synthesis, | Guo et al. (2015) |

| Durum wheat: Altar, Cappelli, Creso, Ofanto and Wollaroi | Shoots and roots | Hoagland solution with 50, 100, and 200 mM NaCl for 10 days. | GCMS; quantification: Mass Hunter quantitative analysis (Metabolomics) | Proline, GABA, threonine, leucine, glutamic acid, glycine, mannose and fructose showed genotype-specific stress tolerance. | Borrelli et al. (2018) |

| Maize | |||||

| Salt-resistant maize hybrid SR12 | Root (1 hr after treatment) | 25 mM NaCl (1 h) | IEF and 2-DE | 10 proteins phosphorylated and six proteins dephosphorylated under salt stress. Enhanced phosphorylated proteins; fructokinase, UDP-glucosyl transferase BX9, and 2-Cys-peroxyredoxine | Zörb et al. (2010) |

| Salt-tolerant F63 and salt-sensitive F35 | Roots (2 days after NaCl treatment) | 160 mM NaCl treatment for 2 days | iTRAQ approach | 28 proteins (salt-responsive proteins), 22 specifically regulated in F63 (constant in F35) including cysteine proteases, ribosomal protein S8, 60 S ribosomal protein L3-1, and SOS proteins. | Cui et al. (2015a) |

| CML421, CML448, CML451 and B73 | Roots (after 4 weeks of salt treatment) | Pots in green house, NaCl added directly to soil mix (EC = 9.5 dS/m) | Singular enrichment analysis (SEA) | 1,747 proteins, of which 209 more abundant in response to salt stress (associated with oxidative stress, dehydration, respiration, and translation) specifically to heat-shock protein (HSP)90-2 (A0A096RTH6) and class III peroxidase (K7U159). | Soares et al. (2018) |

| Salt-tolerant Jing724 and salt-sensitive D9H | Seedlings (7 days after 100 mM NaCl treatment) | 100 mM NaCl (7 days) | iTRAQ approach | Upregulated DRPs and key DRPs, such as glucose-6-phosphatedehydrogenase, NADPH-producing dehydrogenase, glutamate synthase, and glutamine synthetase, in salt-tolerant line. | Luo et al. (2018) |

| 8723 (tolerant) and P138 (sensitive) | Seedling roots (10 days post treatment) | 180 mM salt stress (10 days) | iTRAQ approach | In salt-tolerant genotype, DEPs mainly associated with phenyl propanoid biosynthesis, starch and sucrose metabolism and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway | Chen et al. (2019) |

| PH6WC (tolerant) PH4CV (sensitive) | Roots of seedlings (6-day treatment) | 100 mM NaCl (9 days) | Metabolomic assay | Nucleic acid metabolism significantly higher in salt tolerant genotype, some compounds act under salinity such as cis-9-palmitoleic acid, L-pyroglutamic acid, galactinol, deoxyadenosine, and adenine. | Yue et al. (2020) |

Rice

Nam et al. (2015) performed metabolic profiling of 38 rice genotypes using H-NMR spectroscopy and found glutamine and allantoin positively correlated with salt tolerance. Wang et al. (2021) undertook metabolic profiling of rice genotypes to confirm the role of several metabolites, including amino acids (valine and proline) and organic acids (phosphoenolpyruvic acid, glyceric acid, ascorbic acid), in imparting salt tolerance.

Wheat

Phosphoproteomics identified the salt-stress response and defense biomarkers [cp31BHv, betaine-aldehyde dehydrogenase (BADH), cytosolic (GS1), Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD), MAT3, leucine aminopeptidase 2 (LAP2), and 2-Cys peroxiredoxin BAS1] in wheat (Lv et al. 2016). Cu/Zn SODs, GSTs, DHNs, and V-ATPase were upregulated in roots, and Cu/Zn SODs, LEA, and DHN in leaves (Lv et al. 2016). Jiang et al. (2017) analyzed wheat seedling roots and reported three salt-tolerance-associated proteins: a pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase (PPDK) and two late embryogenesis-abundant (LEA) encoded by TaPPDK, TaLEA1, and TaLEA2, respectively. Ubiquitination-related and pathogen-related proteins, membrane intrinsic protein transporters, TFs, and antioxidant enzymes imparted salt-stress tolerance through single cellular homeostasis in roots. Protecting cell structure during salt stress is an important strategy for stress tolerance. Singh et al. (2017) reported the upregulation of tubulin, profilin, retinoblastoma, casparian strip membrane protein, xyloglucan endotransglycosylase, and ion transporter proteins (e.g., malate transporter) for enhanced salt tolerance. Three genes, TraesCS6A01G336500.1, TraesCS4B01G254300.1, and TaABCF3, encoding OPAQUE1, NRAMP-2, and transporter genes, respectively, enhanced salt stress tolerance by balancing the shoot Na+/K+ ratio, specific energy fluxes for absorption, dissipation, and shoot Na+ uptake (Oyiga et al. 2019). Han et al. (2019) reported the upregulation of five SODs, three malate dehydrogenases and dehydrin proteins, and one V-ATPase protein in roots, and two Cu/Zn, one LEA protein, and DHN proteins in leaves under salt stress. Ethylene modifies or activates ribosomal proteins (RPs) in wheat, reducing ROS accumulation and improving stress tolerance. Eight and 49 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were found in roots and shoots, respectively, and 48 RPs in roots (Ma et al. 2020). In chloroplasts of wheat seedling leaves, 117 upregulated differentially accumulated proteins (DAPs) were associated with the Calvin cycle, amino-acid metabolism, carbon and nitrogen metabolism, transcription and translation, and antioxidation (Zhu et al. 2021).

Maize

Protein analysis of ‘F63’ (tolerant) and ‘F35’ (sensitive) maize genotypes using the iTRAQ approach identified 28 salt-responsive proteins, of which 22 were expressed explicitly in ‘F63’ (Cui et al. 2015a). Similarly, Soares et al. (2018) reported 1747 proteins, of which 209 were abundant in response to salt stress and mainly associated with oxidative stress, dehydration, respiration, and translation. Chen et al. (2019) identified 1056 DEPs, of which 626 and 473 were specific to tolerant and sensitive maize inbred lines, respectively. DEPs expressed in the tolerant lines under salt stress were associated with phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, starch and sucrose metabolism, and the MAPK signaling pathway, while those in the sensitive lines were related to the nitrogen metabolism pathway only (Chen et al. 2019). Hence, under salt stress, glucose metabolism is mainly induced in salt-tolerant lines, while nucleic acid metabolism is induced in salt-sensitive lines at the seedling stage.

Comparing proteomics studies across rice, wheat, and maize highlights glutamine as a common, key amino acid (via upregulation of glutamine synthetase) for imparting salinity stress tolerance in salt-tolerant lines (Table 4). Glutamine synthetase enhances salt tolerance in the tolerant cultivars by imparting better photorespiration capacity (Kamal et al. 2012; Nam et al. 2015; Luo et al. 2018). Studies have shown that enhanced proline in rice and wheat, and RPs in wheat and maize impart salt tolerance (Table 4). Hence, these key amino acids can be used as metabolite markers in salinity stress breeding programs in cereal crops.

Meta-analysis for salinity stress tolerance

With the availability of numerous QTL and transcriptomics studies, meta-analysis is the best approach for identifying or predicting consensus genomic regions (candidate genes and meta-QTL i.e., genomic intervals containing two or more QTL from independent studies) for subsequent use in plant breeding programs (Sinha et al. 2021). Meta-analysis can be performed with expression datasets (microarray or RNA-seq) and QTL datasets. For example, Kaur et al. (2016) performed a meta-analysis using a publicly available microarray data set and RNA-seq data to identify 31 candidate genes associated with salt tolerance in rice. Later, Buti et al. (2019) performed a meta-analysis of RNA-seq data in rice to identify chilling, osmotic and salt stress tolerant genes. Later, Islam et al. (2019) predicted 11 meta-QTL for SIS and shoot Na+ and K+ concentrations and identified related candidate genes (using gene expression studies and gene ontology prediction). Kong et al. (2019) performed a meta-analysis of the salt stress transcriptomic response in rice (based on 96 publicly available microarray datasets) and identified 5559 DEGs, with most related to the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, Ca2+ signal transduction, hormone signals, TFs and regulators. Recently, Mansuri et al. (2020) used published transcriptomic and QTL mapping studies to predict 3449 DEGs in 46 meta-QTL, with most involved in functions of ion transport, cell wall organization, transcriptional regulation, cell response to stress, transporter activity, TFs, and oxidoreductase.

Epigenomics and genome editing approaches for salt tolerance: recent progress

Recent progress in the technological advances of epigenetics and transgenics is promising for delivering climate-resilient genotypes. The epigenetic changes include chromatin modification, several post-transcriptional histone modifications and DNA methylation which play an important role in imparting salt stress tolerance in crops. The hypermethylation of cytosines at HKT genes in shoots and roots imparted salt tolerance in wheat (Kumar et al. 2017). Wang et al. (2011) reported altered DNA methylation in salt-sensitive and salt-tolerant rice genotypes. Subsequently, methylation-sensitive amplification polymorphism analysis revealed the role of DNA methylation for salt tolerance in rice, evident from enhanced DNA methylation and differential gene expression under high salinity conditions (Karan et al. 2012). Similarly, overexpression of miR156 reduced the expression of TFs (SPL9 and DFR), imparting salt tolerance in rice (Cui et al. 2014). Furthermore, high-throughput sequencing (MeDIP-seq) technologies resolved the differentially methylated regions at the whole-genome level in salt-tolerant rice (Ferreira et al. 2015) and maize (Sun et al. 2018). Recently, Rajkumar et al. (2020) reported cultivar-specific DNA methylation with hypermethylation prominent in salt-tolerant rice cultivar ‘Pokkali’ and hypomethylation in drought-tolerant cultivar ‘Nagina22’ under salt stress. These recent findings indicate the potential role of epigenetic factors in imparting salinity tolerance in rice, wheat and maize.

In recent years, advancements in CRISPR/Cas technology have provided a new avenue for genome editing, enabling target site-editing of desirable alleles to produce desirable phenotypes (Kumar et al. 2020). Salinity tolerance in rice was induced by editing the OsRR22 gene using CRISPR-Cas9 (Zhang et al. 2019). Kumar et al. (2020) used CRISPR-Cas9 based gene editing to produce a mutant Cas9-freedst Δ184–305 in indica rice cultivar ‘MTU1010’, which showed a moderate level of osmotic stress under seedling-stage salt stress. Further, several transgenes were used to induce salinity tolerance in rice for salt exclusion and Na+ compartmentation viz., PpENA1, PyKPA1, SOD2, AtHKT1;1, HmHKT1;5, HvHKT1;5, OsVP1, OsNHX1, CgNHX1, AdNHX1, OsNHX1, PgNHX1 and AtNHX1 (Kotula et al. 2020). The use of genome editing for salt stress tolerance is limited but has the potential for developing salt-tolerant cereal crops.

Genomics-assisted bred salt-tolerant cultivars: achievements

Crop responses to salinity and their tolerance to salinity are complex genetic and physiological phenomena. Only major QTL can be targeted through marker-assisted backcrossing (MABC) as evident in rice (Krishnamurthy et al. 2020). Maize and wheat lack introgression studies for major QTL, which may be due to complex genome size or lack of validation of functionality of identified QTL. However, one successful example is ‘Line149’ in wheat (Munns et al. 2012) developed through introgressing TmHKT1;5-A, a gene from Triticum monococcum that confers Na+ exclusion. Dominant markers, gwm410 and gwm291 and co-dominant marker, cslinkNax2 were used to select favorable lines (Munns et al. 2012). In contrast, there have been remarkable achievements in introgressing major QTL for salinity stress tolerance in rice. ‘Saltol’ is the most celebrated and widely used genomic region for seedling-stage salt tolerance, adapted from ‘FL478’ (derived from local landrace ‘Pokkali’ from Kerala, India) (Bonilla et al. 2002). Fine mapping of this region revealed a major gene, SKC1, which stabilizes K+ homeostasis in the salt-tolerant variety (Ren et al. 2005). SKC1 encodes an HKT-type transporter that is Na+ selective, and maintains K+/Na+ homeostasis under salt stress. ‘FL478’ was used as a universal donor for ‘Saltol’ QTL in the MABC program to improve seedling-stage salt tolerance in several commercial cultivars (Krishnamurthy et al. 2020). In India, several ‘Saltol’ introgression lines, (i.e., near-isogenic lines) have been developed in popular released cultivars, including ‘Sarjoo52’, ‘Pusa Basmati-1’, ‘Pusa Basmati 1121’, and ‘Pusa 1509’, with yields on par with the original variety under non-stressed conditions and better in salinity prone areas (Krishnamurthy et al. 2020; Singh et al. 2018; Babu et al. 2017a). Rana et al. (2019) used the hitomebore salt-tolerant-1 (hst1) gene from an EMS mutant line governing the seedling and reproductive stage to develop the salt-tolerant variety, ‘Kaijin’, which was used to introgress the hst1 gene in ‘Yukinko-mai’ to develop ‘YNU31-2-4’, a salt-tolerant cultivar. The Hst1 gene encodes a B-type response regulator called OsRR22 (Os06g0183100). A substitution mutation in the third exon of this gene governs salt tolerance in this genotype. Marker-assisted recurrent selection (MARS) was recently used to improve drought and salt tolerance in the ‘IR58025B’ genetic male sterile maintainer line, the most common maintainer line used for hybrid rice development in India (Suryendra et al. 2020). The complete list of improved rice lines/cultivars using genomics-assisted breeding is presented in Table 5. The physiological mechanisms of salt tolerance at the reproductive stage in rice differ from those at the seedling stage; hence, a separate breeding strategy should be followed (Pundir et al. 2021; Singh et al. 2021).

Table 5.

Details of saline-tolerant improved rice cultivars developed through marker-assisted backcrossing (MABC) or marker-assisted recurrent selection (MARS) in rice.

| QTL | Donor | Recipient | Line/Cultivar developed | Trait improved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saltol | FL478 | ASS996 | ASS996-Saltol | SSST | Huyen et al. (2012) |

| Saltol | FL478 | BT7 | BT7-Saltol | SSST | Linh et al. (2012) |

| Saltol | FL478 | Binadhan-5 | Binadhan-5-Saltol | SSST | Moniruzzaman et al. (2012) |

| Saltol | FL478 | Q5DB | Q5DB-Saltol | SSST | Huyen et al. (2013) |

| Saltol | FL478 | BRRI dhan49 | BRRI dhan49-Saltol | SSST | Hoque et al. (2015) |

| Saltol | FL478 | Rassi | Rassi-Saltol | SSST | Bimpong et al. (2016) |

| Saltol | FL478 | IR64 | IR64-Saltol | SSST | Ho et al. (2016) |

| Saltol | FL530 | KDML105 | KDML105-Saltol | SSST | Punyawaew et al. (2016) |

| Saltol | FL478 | PB1121 | Pusa1734-8-3-3 | SSST | Babu et al. (2017a) |

| Saltol | FL478 | Pusa Basmati-1 | Pusa Basmati-1-Saltol | SSST | Singh et al. (2018) |

| hst1 | Kaijin | Yukinko-mai | YNU31-2-4 | SSST&RSST | Rana et al. (2019) |

| Saltol | FL478 | Improved WP | Improved WP - Saltol | SSST | Valarmathi et al. (2019) |

| Saltol | FL478 | Pusa44 | Pusa44-Saltol | SSST | Krishnamurthy et al. (2020) |

| Saltol | FL478 | Sarjoo52 | Sarjoo52-Saltol | SSST | Krishnamurthy et al. (2020) |

| Saltol | Pokkali | RD6 | RD6-Saltol | SSST | Thanasilungura et al. (2020) |

| Saltol | FL478 | PB 1509 | PB1509-Saltol | SSST | Yadav et al. (2020) |

| Saltol | FL478 | Aiswarya | Aiswarya-Saltol-Sub1 | SSST | Nair and Shylaraj (2021) |

| Saltol | FL478 | IR58025B | IR58025B-Saltol-qDTY12.1 | SSST | Suryendra et al. (2020) |

SSST seedling-stage salinity tolerance, RSST reproductive stage salinity tolerance.

Conclusion and future perspectives

Salinity is a major abiotic stress that adversely affects crop growth and development, resulting in yield losses. The reclamation of saline ecologies is a time-consuming and challenging task. Developing salt-tolerant cultivars of rice, wheat, and maize, the staple food crops, is a sustainable and cost-effective approach to safeguard food security. The availability of molecular markers, modern breeding tools, and omics techniques can help to understand the genetic basis of salt tolerance by identifying relevant genomic regions for the quick development of tolerant cultivars instead of the time-consuming conventional breeding approach. A systems biology approach that integrates all omics approaches (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics and phenomics) is necessary to understand salt-stress tolerance mechanisms in different crops. However, a pre-breeding approach (using wild relatives and landraces) is needed to broaden the genetic base of germplasm for traits associated with salinity stress tolerance, as most crop breeding programs are based on a few donor lines. Rice has witnessed remarkable success, particularly with the Saltol QTL. Similar success is expected in wheat and maize considering the availability of major QTL and emphasis on salinity stress studies. The availability of multi-parent mapping populations in these crops will help identify novel alleles for salinity stress tolerance (Gireesh et al. 2021). Using molecular breeding approaches combined with omics and rapid generation techniques, such as speed breeding to shorten generations and genome editing to edit the target gene, will further hasten the development of salt-tolerant cultivars (Watson et al. 2018; Kumar et al. 2020). Recently, rice witnessed the use of CRISP-Cas for salinity improvement by targeting the OsRR22 and OsDST genes; wheat and maize will likely witness the success of genome-edited cultivars in the near future. Using a pangenomics approach and wild relatives will help identify the core and unique genes for salinity stress adaptation in rice, wheat, and maize (Khan et al. 2020). Identifying cross-tolerance for multiple abiotic stresses and stress memory development is another worth exploring area to develop multi-stress tolerant cultivars (Choudhary et al. 2021). Considering the worldwide salinity crisis, better policies, and allocation of grants and funding for salinity stress research will assist in the sustainable development of salt-tolerant elite cultivars.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) for support received in preparing the manuscript. The first author thanks the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB) Government of India for financial support through the EEQ (2018/001394) scheme.

Author contributions

PK and MC conceptualized the manuscript. PK, MC, TH, NRP, VS, VTV, SS, NL and RKT interpreted the literature and drafted the manuscript: section wise. SR and KHMS critically edited the manuscript. PK, MC and NRP contributed equally in the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41437-022-00516-2.

References

- Abbasi GH, Akhtar J, Ahmad R, Jamil M, Anwar-Ul-Haq M, Ali S, et al. Potassium application mitigates salt stress differentially at different growth stages in tolerant and sensitive maize hybrids. Plant Growth Regul. 2015;76:111–125. doi: 10.1007/s10725-015-0050-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahanger MA, Agarwal RM. Salinity stress induced alterations in antioxidant metabolism and nitrogen assimilation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L) as influenced by potassium supplementation. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;115:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad P, Abdel Latef AA, Rasool S, Akram NA, Ashraf M, Gucel S. Role of proteomics in crop stress tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1336. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]