Abstract

Background:

Cognitive function is essential to effective self-management of heart failure (HF). Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease related dementias (AD/ADRD) can coexist with HF, but its exact prevalence and impact on health care utilization and death is not well defined.

Methods:

Residents from 7 southeast Minnesota counties with a first-ever diagnosis code for HF between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2018 were identified. Clinically diagnosed AD/ADRD was ascertained using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse algorithm. Patients were followed through 3/31/2020. Cox and Andersen-Gill models were used to examine associations between AD/ADRD (before and after HF) and death and hospitalizations, respectively.

Results:

Among 6,336 patients with HF (mean age [SD] 75 years [14], 48% female), 644 (10%) carried a diagnosis of AD/ADRD at index HF diagnosis. The 3-year cumulative incidence of AD/ADRD after HF diagnosis was 17%. During follow-up (mean [SD] 3.2 [1.9] years), 2,618 deaths and 15,475 hospitalizations occurred. After adjustment, patients with AD/ADRD before HF had nearly a 2.7 times increased risk of death, but no increased risk of hospitalization compared to those without AD/ADRD. When AD/ADRD was diagnosed after the index HF date, patients experienced a 3.7 times increased risk of death and a 73% increased risk of hospitalization compared to those who remain free of AD/ADRD.

Conclusions:

In a large, community cohort of patients with incident HF, the burden of AD/ADRD is quite high as more than one fourth of patients with HF received a diagnosis of AD/ADRD either before or after HF diagnosis. AD/ADRD markedly increases the risk of adverse outcomes in HF underscoring the need for future studies focused on holistic approaches to improve outcomes.

Keywords: heart failure, Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease related dementias, health care utilization, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) is a disease of aging populations that occurs in the context of multimorbidity. Nearly 86% of patients with HF have 2 or more additional chronic conditions.1 Thus, addressing the HF epidemic requires an understanding of multimorbidity in HF populations and, in particular, how coexisting conditions interact with HF to impact clinical outcomes and health care utilization.

Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease related dementias (AD/ADRD) occupy a distinct position within the spectrum of conditions that coexist with HF.2 Indeed, an excess risk of cognitive impairment among persons with HF was recently reported in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study independently of other comorbid conditions.3 However, the prevalence of overt clinical AD/ADRD in HF and its impact on health care utilization and outcomes remains to be fully delineated. AD/ADRD can adversely impact the management of HF given that HF requires effective self-management that in turn relies on cognitive function. Defining the association between AD/ADRD and adverse outcomes in HF is an important first step in designing optimal care plans. Thus, we undertook this study to investigate the occurrence of AD/ADRD and its impact on adverse outcomes, including death and hospitalizations, among patients with HF.

METHODS

Study Setting

This study was conducted within seven counties in southeastern Minnesota (Dodge, Freeborn, Mower, Olmsted, Steele, Wabasha, and Waseca). The Rochester Epidemiology Project, which includes data from various health care institutions (Mayo Clinic Rochester, Mayo Clinic Health System clinics and hospitals, and Olmsted Medical Center and its affiliated clinics), was utilized. The REP is a records linkage system which enables the retrieval of nearly all health care encounters and clinical events of residents living in southeastern Minnesota.4–6

HF Case Identification

Residents of a 7-county area in southeastern Minnesota age 18 or older with a first-ever International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) code 428 or ICD-10 code I50 for HF within the REP records between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2018 were identified. Those with a HF diagnosis code prior to the study period were excluded using a 3 year look back window. A HF case was defined as having at least 2 HF codes (in- or outpatient codes) separated by at least 30 days. This algorithm was selected because it maximizes positive predictive value and sensitivity.7

Clinically Diagnosed AD/ADRD Ascertainment

Clinically diagnosed AD/ADRD before and after the HF diagnosis was ascertained with ICD codes provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse8 using the criterion of the occurrence of at least 1 code for AD/ADRD (Supplementary Table S1). This code set has been shown to have a sensitivity of 87%.9 A 3 year look back window was used to determine AD/ADRD prior to HF, and AD/ADRD after HF diagnosis was ascertained through 3/31/2020.

Other Patient Characteristics

Educational attainment, marital status, age, and sex were obtained through the electronic indices of the REP record linkage system. Comorbidities were also retrieved from the REP. Chronic conditions identified as a public health priority from the US Department of Health and Human Services were identified.10,11 These conditions were ascertained via the REP by electronically retrieving ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes from both inpatient and outpatient encounters. Two occurrences of a code (either the same code or two different codes within the code set for a given disease) separated by more than 30 days and occurring within 3 years prior to the incident HF date were required to be classified as having the condition. Since all patients had HF and AD/ADRD was the exposure, these conditions were not included. Very few individuals in our cohort had autism, hepatitis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and these were also not included. However, we added anxiety to our list as this is also a common chronic condition, leaving 16 chronic conditions (hypertension, coronary artery disease, arrhythmia, hyperlipidemia, stroke, arthritis, asthma, cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, diabetes, osteoporosis, depression, schizophrenia, substance abuse disorder, and anxiety).

Outcomes

Patients were followed from incident HF diagnosis date through 3/31/2020 for vital status and hospitalizations. Deaths were identified using the REP indices, which compiles death information from medical records, death certificates received from the state of Minnesota, and data from the National Death Index Plus. CVD cause of death was determined from the underlying cause of death using the ICD-10 codes outlined by the American Heart Association.12 Hospitalizations were collected via the REP and in-hospital transfers were counted as one hospitalization.13,14 The primary reason for hospitalization was classified as cardiovascular or non-cardiovascular using ICD-10 codes outlined by the American Heart Association.12

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics are presented as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables, mean (standard deviation) for normally-distributed continuous variables, or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables with a skewed distribution. Chi-square tests or t-tests were used to test differences in characteristics between persons with and without prior AD/ADRD.

The cumulative incidence of AD/ADRD following HF was estimated treating death as a competing risk. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to examine the association between AD/ADRD (prior and post HF) and death. AD/ADRD after HF was modeled as a time-dependent variable. Univariable models were run and then covariates including age, sex, education, and comorbidities were added to the model. To determine if AD/ADRD (prior and post HF) is associated with hospitalizations, Andersen-Gill modeling was used to account for repeated events, censoring subjects at death. Models were run univariably and while controlling for baseline characteristics. Interactions between AD/ADRD and sex were tested. The proportional hazard assumption was tested using the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and was found to be valid.

All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

RESULTS

HF and Occurrence of AD/ADRD

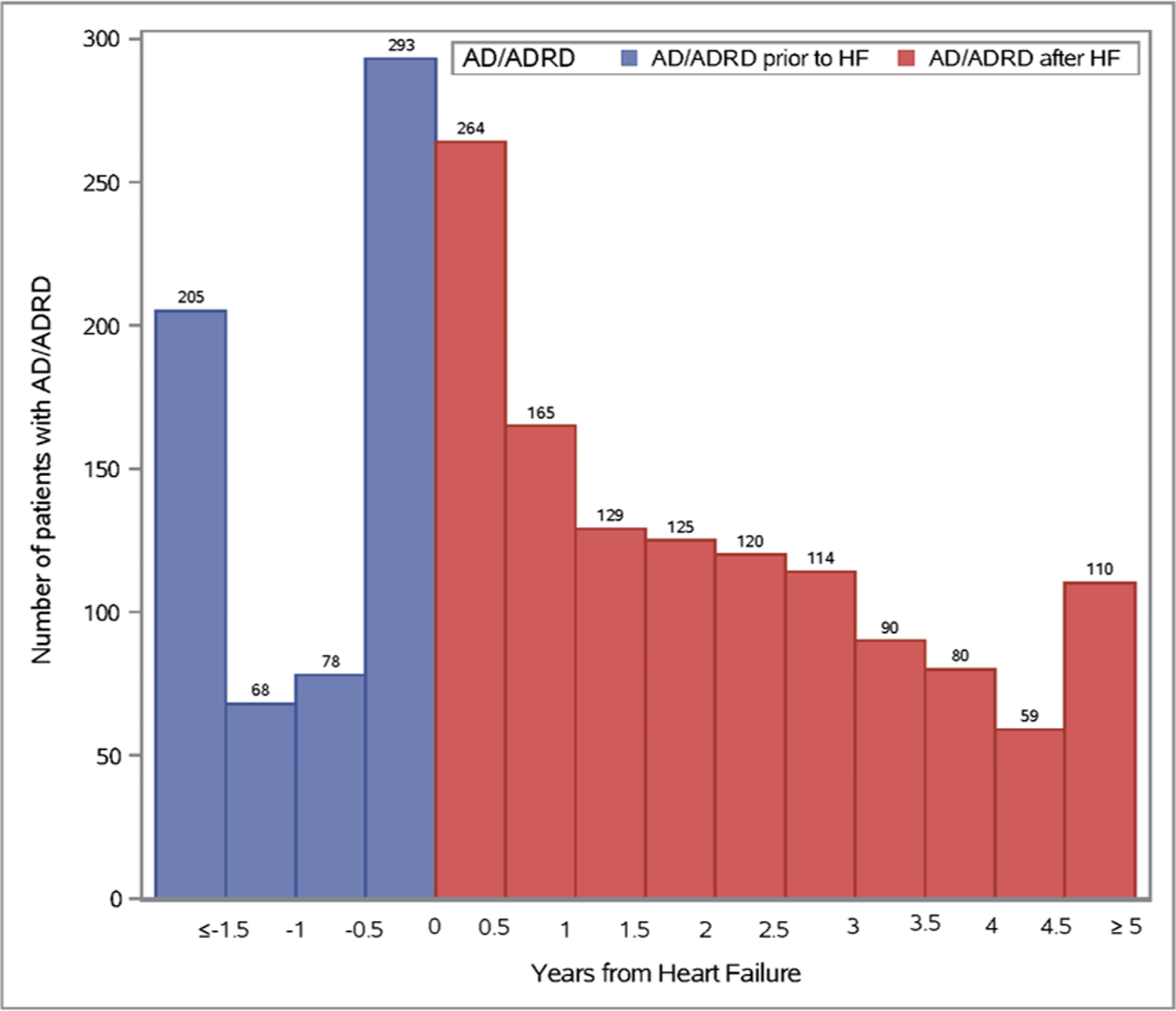

Among 6,336 patients with incident HF (mean [SD] age 75 [14] years, 48% female), a total of 1,990 (30%) had a clinical diagnosis of AD/ADRD either before (n=644 [10%]) or after (n=1,256 [20%]) HF diagnosis (Figure 1). The occurrence of AD/ADRD before diagnosis of HF or within 1 year after diagnosis was high (n=1,073; 17%). Of the 1256 patients that were diagnosed with AD/ADRD after HF diagnosis, the majority were diagnosed early in the course of HF, as 428 cases of AD/ADRD (34%) were identified within 1 year and 682 (54%) within 2 years. The median [Q1-Q3] time from HF to AD/ADRD was 1.7 [0.7–3.1] years. The 1- and 3-year cumulative incidence (95% CI) of AD/ADRD after HF was 7.6% (6.9–8.3%) and 17.1% (16.2–18.0%), respectively.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease related dementias (AD/ADRD) before and after heart failure diagnosis.

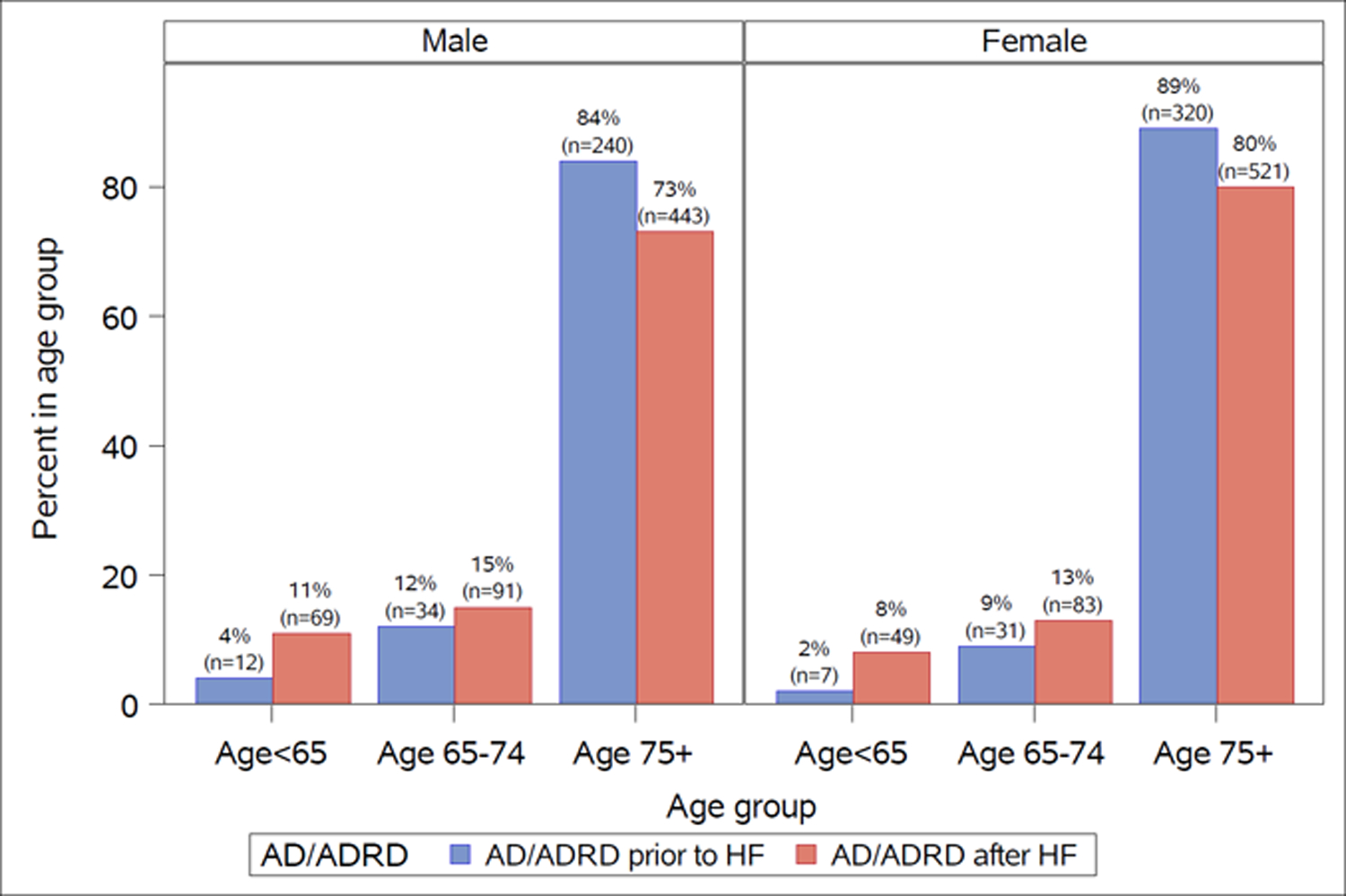

Baseline patient characteristics comparing those with prior AD/ADRD to those without are outlined in Table 1. Patients with prior AD/ADRD were older, more likely to be women, have more comorbidities, and less likely to be married (p<0.001). The proportion of AD/ADRD prior to HF and after HF, stratified by age and sex, is shown in Figure 2. For both males and females, the proportion of AD/ADRD prior to HF and after HF increases with increasing age.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics, Overall and by Prior Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease Related Dementias (AD/ADRD) Status

| Total (N=6336) |

No prior AD/ADRD (N=5692) |

Prior AD/ADRD (N=644) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age, Mean (SD) | 75 (14) | 74 (14) | 84 (8.7) | <0.001 |

| Female | 3048 (48) | 2690 (47) | 358 (56) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 5482 (87) | 4883 (86) | 599 (93) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 3506 (55) | 3133 (55) | 373 (58) | 0.164 |

| Arrhythmia | 5157 (81) | 4621 (81) | 536 (83) | 0.206 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 4759 (75) | 4267 (75) | 492 (76) | 0.425 |

| Stroke | 1318 (21) | 1103 (19) | 215 (33) | <0.001 |

| Arthritis | 3382 (53) | 2963 (52) | 419 (65) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 747 (12) | 682 (12) | 65 (10) | 0.159 |

| Cancer | 2253 (36) | 2012 (35) | 241 (37) | 0.297 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2761 (44) | 2403 (42) | 358(56) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1881 (30) | 1678 (29) | 203 (32) | 0.282 |

| Diabetes | 3447 (54) | 3147 (55) | 300 (47) | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 1023 (16) | 849 (15) | 174 (27) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1720 (27) | 1443 (25) | 277 (43) | <0.001 |

| Schizophrenia | 322 (5.1) | 215 (3.8) | 107 (17) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 1272 (20) | 1096 (19) | 176 (27) | <0.001 |

| Substance abuse disorder | 869 (14) | 786 (14) | 83 (13) | 0.520 |

| Married | 3370 (54) | 3104 (55) | 266 (42) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 71 | 67 | 4 | |

| Education level | <0.001 | |||

| Non-high school graduate | 732 (13) | 623 (12) | 109 (19) | |

| High school graduate | 2269 (39) | 2052 (39) | 217 (39) | |

| Some college/2-year degree | 1499 (26) | 1382 (27) | 117 (21) | |

| 4 year or advanced degree | 1262 (22) | 1143 (22) | 119 (21) | |

| Missing | 574 | 492 | 82 | |

Data presented as N (%) unless otherwise indicated.

SD standard deviation

Figure 2.

Proportion of Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease related dementias (AD/ADRD) before and after heart failure, stratified by age and sex.

Association between AD/ADRD prior to HF and death

After a mean [SD] follow-up of 3.2 [1.9] years, 2,618 deaths and 15,475 hospitalizations occurred. After adjustment for age and sex, a prior diagnosis of AD/ADRD was associated with a more than 3 times increased risk of death (HR: 3.04; 95% CI: 2.72, 3.39; Table 2) compared to those who did not have a diagnosis of AD/ADRD. After further adjustment for comorbidities, marital status, and education, the association was only slightly attenuated (HR: 2.71; 95% CI: 2.40, 3.07). Prior AD/ADRD was associated with an increased risk of both non-CVD and CVD-related death compared to AD/ADRD-free counterparts; however, the association with non-CVD death was stronger compared to CVD death (adjusted HR for CVD death: 1.79; 95% CI: 1.47, 2.19; adjusted HR for non-CVD death: HR: 3.73; 95% CI: 3.17, 4.37).

TABLE 2.

Hazard Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for the Associations between Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease Related Dementias (AD/ADRD) and Death and Hospitalization in Heart Failure

| No AD/ADRD N=4436 |

Prior AD/ADRD N=644 |

P-value | Post AD/ADRD N=1256 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Death (N=2618) * | |||||

| Age and Sex Adjusted | 1 (ref) | 3.04 (2.72, 3.39) | <0.001 | 3.98 (3.62, 4.38) | <0.001 |

| Fully Adjusted † | 1 (ref) | 2.71 (2.40, 3.07) | <0.001 | 3.70 (3.34, 4.10) | <0.001 |

| CV-Death (N=1122) | |||||

| Age and Sex Adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.98 (1.65, 2.36) | <0.001 | 3.33 (2.88, 3.84) | <0.001 |

| Fully Adjusted † | 1 (ref) | 1.79 (1.47, 2.19) | <0.001 | 3.12 (2.67, 3.64) | <0.001 |

| Non-CV Death (N=1446) | |||||

| Age and Sex Adjusted | 1 (ref) | 4.16 (3.61, 4.79) | <0.001 | 4.75 (4.17, 5.41) | <0.001 |

| Fully Adjusted † | 1 (ref) | 3.73 (3.17, 4.37) | <0.001 | 4.40 (3.83, 5.06) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalizations** (N=15475) | |||||

| Age and Sex Adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.20 (1.08, 1.33) | <0.001 | 1.89 (1.72, 2.08) | <0.001 |

| Fully Adjusted † | 1 (ref) | 1.04 (0.93,1.16) | 0.515 | 1.73 (1.57, 1.90) | <0.001 |

| CV-hospitalizations (N=4882) | |||||

| Age and Sex Adjusted | 1 (ref) | 0.81 (0.69,0.95) | 0.010 | 1.47 (1.29,1.68) | <0.001 |

| Fully Adjusted † | 1 (ref) | 0.80 (0.67, 0.94) | 0.008 | 1.44 (1.26, 1.66) | <0.001 |

| Non-CV hospitalizations (N=10592) | |||||

| Age and Sex Adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.41 (1.26, 1.58) | <0.001 | 2.09 (1.88, 2.33) | <0.001 |

| Fully Adjusted † | 1 (ref) | 1.15 (1.01, 1.31) | 0.035 | 1.84 (1.66, 2.05) | <0.001 |

50 patients were missing cause of death

Adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, coronary artery disease, arrhythmia, hyperlipidemia, stroke, arthritis, asthma, cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic pulmonary disease, depression, diabetes, osteoporosis, schizophrenia, substance abuse disorder, anxiety, marital status and education.

1 person was missing primary reason of hospitalization

Association between AD/ADRD prior to HF and hospitalizations

Patients who had AD/ADRD prior to HF had a 20% increased risk of hospitalization after adjustment for age and sex (HR: 1.20; 95% CI: 1.08, 1.33), compared to those that did not have a diagnosis of AD/ADRD. Adjustment for additional covariates attenuated this association (adjusted HR: 1.04; 95% CI: 0.93, 1.16). There was an interaction between prior AD/ADRD and sex (p=0.007). Men who had AD/ADRD prior to HF had a 20% increased risk of hospitalization (HR 1.20; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.38) compared to men who did not have AD/ADRD, while there was no association for their female counterparts (HR: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.77, 1.05). Prior AD/ADRD was associated with an increased risk of non-CVD related hospitalization (adjusted HR: 1.15 95% CI: 1.01, 1.31); however, it was associated with a reduced risk of CVD-related hospitalization (adjusted HR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.67, 0.94) compared to those that did not have AD/ADRD.

Association between AD/ADRD after HF and death

A clinical diagnosis of AD/ADRD that occurred after HF was associated with nearly a 4 times increased risk of death after adjustment for age and sex (HR: 3.98; 95% CI: 3.62, 4.38), compared to patients that did not have AD/ADRD. Further adjustment for comorbidities, marital status, and education attenuated this association slightly (adjusted HR: 3.70; 95% CI: 3.34, 4.10). Patients who developed AD/ADRD after HF had an increased risk of both CVD-related and non-CVD related death (adjusted HR for CVD death: 3.12; 95% CI: 2.67, 3.64; adjusted HR for non-CVD death: HR: 4.40; 95% CI: 3.83, 5.06) compared to patients that did not have a diagnosis of AD/ADRD.

Association between AD/ADRD after HF and hospitalizations

After adjustment for age and sex, AD/ADRD that occurred after HF was also associated with an increased risk of hospitalizations (HR: 1.89; 95% CI: 1.72, 2.08) compared to patients without AD/ADRD. Results were only slightly attenuated after further adjustment (HR: 1.73; 95% CI: 1.57, 1.90). Patients who developed AD/ADRD after HF had an increased risk of both CVD-related and non-CVD related hospitalizations (adjusted HR for CVD hospitalization: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.26,1.66; adjusted HR for non-CVD hospitalization: HR: 1.84; 95% CI: 1.66, 2.05) compared to patients that did not have a diagnosis of AD/ADRD.

DISCUSSION

In a large, community cohort of patients with incident HF, the burden of AD/ADRD is high as more than one fourth of patients with HF received a diagnosis of AD/ADRD either before or after HF diagnosis. Patients with HF and clinically diagnosed AD/ADRD have an increased risk of death and hospitalization compared to AD/ADRD-free counterparts.

HF and Occurrence of AD/ADRD

Prior studies, including from our group, have uncovered a staggering prevalence of multiple chronic conditions in HF patients (86% of HF patients had 2 or more additional chronic conditions) which adversely impact quantity and quality of life.1,15 The HF-AD/ADRD dyad is particularly concerning as there is no effective cure for these two conditions and they impose an immense burden of symptoms, loss of independence, and excess risk of death.16,17 Older persons experience a disproportionate burden of HF and AD/ADRD. An estimated 6.5 million adult Americans are living with HF, a prevalence of approximately 10% over age 80.12 The prevalence of AD/ADRD is estimated to be 6.5% among persons age 60 or older, equating to approximately 5 million persons.18

Herein, we report that approximately 10% of patients had a clinical diagnosis of AD/ADRD prior to their HF diagnosis and the 3-year cumulative incidence of AD/ADRD after HF was 17%. This equates to more than one fourth of patients with HF receiving a diagnosis of AD/ADRD either before or after HF diagnosis.

Our data are congruent with that from a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries where 10% of hospitalized patients with HF had dementia at baseline,19 and with previous reports20–24 that suggest an excess risk of AD/ADRD in HF. The concept of a “heart–brain connection”25 has been proposed with several pathways suggested to illustrate how heart disease and AD/ADRD interact.26 Indeed, the role of cardiovascular risk factors as shared contributors to both HF and AD/ADRD was highlighted, with HF associated with neurocognitive dysfunction independently of other comorbidities.27 Other possible suggested causes are cerebral hypoperfusion, hemodynamic factors with low cardiac index,28–30 and genetic variants.26

Impact of AD/ADRD on Outcomes in HF

Data on the impact of AD/ADRD on health care utilization and death in HF patients are scarce. A study of a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with HF found that dementia was associated with an increased risk of both short-term (30-day) and long-term (5-year) mortality.19 In our large, community cohort of patients with HF, we found that patients with a diagnosis of AD/ADRD before or after HF had a large increased risk of death. We also found that patients diagnosed with AD/ADRD after HF experienced an increased risk of hospitalization compared to those that did not develop AD/ADRD, while those who had AD/ADRD before HF did not have an increased risk of hospitalization. We further categorized outcomes into CVD and non-CVD related. We found that for both AD/ADRD prior and post HF the association with non-CVD death was stronger compared to CVD death. Furthermore, the association between AD/ADRD post HF and non-CVD related hospitalizations was stronger compared to CVD-related hospitalizations. These results support prior reports, including from our group, that indicate that most hospitalizations in persons with HF are due to coexisting conditions rather than to HF exacerbation.13,14

Clinical Implications

Our results highlight the need to recognize the presence and impact of AD/ADRD on outcomes in HF. Indeed, HF and AD/ADRD are both conditions for which there is no effective cure, which reduce both the quantity and quality of life of patients and profoundly impact families and caregivers. AD/ADRD results in a prolonged course of cognitive decline that can influence the diagnosis and treatment of comorbid conditions and generates complex management challenges. This is particularly problematic for HF which requires effective self-management that relies on cognitive abilities.31 A recent systematic review summarized existing evidence supporting the efficacy of nurse led interventions to improve heart failure knowledge, self-care and quality of life among patients with HF and cognitive impairment or AD/ADRD.32 While these data are encouraging, more research is clearly warranted. Further, the treatment of HF often requires considering invasive cardiac interventions, which carry an inherent risk. Balancing the risk of an intervention against its potential benefits must take into account comorbid conditions in the decision-making process. Specifically, when AD/ADRD and HF coexist such decision-making is particularly challenging. The notion that AD/ADRD is often underdiagnosed, some reports suggest in up to 50% of the cases,33–35 magnifies this concern. Thus, heightened awareness of the frequent coexistence of HF with AD/ADRD should lead to more deliberate assessment of cognition prior to invasive procedures.

Limitations and Strengths

Some limitations should be considered to aid in the interpretation of our findings. We used diagnosis codes to ascertain HF; however, we used a validated EHR algorithm that maximizes PPV and sensitivity.7 While we may have missed some healthcare encounters that happened outside of the REP, our coverage of this population was >90%. We also used diagnosis codes to define AD/ADRD, and as the onset of AD/ADRD is difficult to define in clinical practice, under-ascertainment during early stages is a concern.33–35 However, the REP captures data from primary and specialty care, outpatient visits and hospitalizations, and the reliability of EHR ascertainment of AD/ADRD has been validated in the REP.36 Further, under-ascertainment notwithstanding, the present data document an alarming prevalence of AD/ADRD in HF and a large adverse impact on outcomes, both findings constituting a call for better evaluation of cognitive function in patients with HF. While we did not differentiate the subtypes of AD/ADRD, it is acknowledged that ADRDs share many cognitive and pathological features which can be difficult to distinguish from AD.37 Causes of dementia are multifactorial in the setting of the HF syndrome and several contributing factors likely often coexist, but it is beyond the scope of this paper to address the causes of AD/ADRD in HF. The generalizability of our study may be limited as our region is predominantly white; however, this region has similar age, sex, and racial/ethnic characteristics as the state of Minnesota and the Upper Midwest region of the US.4,6 Finally, as with any observational study, we cannot rule out the possibility of residual confounding due to unmeasured variables.

Our study has many strengths. We report on the occurrence of AD/ADRD before and after HF diagnosis in a large, contemporary, community-based cohort. Utilizing the resources of the REP, we have near complete capture of comorbid conditions and outcomes in a large area of southeastern Minnesota.4 We report on the impact of AD/ADRD on outcomes including both death and hospitalizations, and with our comprehensive data we were able to further classify outcomes into CVD vs. non-CVD related.

Conclusions

More than one fourth of patients with HF received a diagnosis of AD/ADRD either before or after HF diagnosis. AD/ADRD markedly increases the risk of adverse outcomes in HF. These data underscore the importance of improving the detection of AD/ADRD in patients with HF in order to deploy a holistic approach to care delivery and hopefully optimize outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1. Diagnosis codes used to identify Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease Related Dementias

Key Points:

Heart failure requires effective self-management that relies on cognitive function.

The burden of dementia in heart failure is high and associated with adverse outcomes.

Why does it matter?

Improving the detection of dementia in heart failure and deploying a holistic approach to care delivery may optimize outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Deborah Strain for manuscript formatting and preparation.

Funding Source:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R21 AG64804) and used the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA; AG 058738), by the Mayo Clinic Research Committee, and by fees paid annually by REP users. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) or the Mayo Clinic. The funding sources played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

SPONSOR’S ROLE

The funding sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, or preparation of paper.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts. Dr. Knopman serves on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for the DIAN study. He serves on a Data Safety monitoring Board for a tau therapeutic for Biogen but receives no personal compensation. He is an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Biogen, Lilly Pharmaceuticals and the University of Southern California. He has served as a consultant for Roche, Samus Therapeutics, Third Rock and Alzeca Biosciences but receives no personal compensation. He receives funding from the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chamberlain AM, St Sauver JL, Gerber Y, et al. Multimorbidity in heart failure: a community perspective. Am J Med. 2015;128(1):38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolters FJ, Segufa RA, Darweesh SKL, et al. Coronary heart disease, heart failure, and the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(11):1493–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witt LS, Rotter J, Stearns SC, et al. Heart Failure and Cognitive Impairment in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(10):1721–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rocca WA, Grossardt BR, Brue SM, et al. Data resource profile: expansion of the Rochester Epidemiology Project medical records-linkage system (E-REP). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(2):368–368j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(2):151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tison GH, Chamberlain AM, Pletcher MJ, et al. Identifying heart failure using EMR-based algorithms. Int J Med Inform. 2018. (120):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW), CCW Condition Algorithms. Accessed May 7, 2021 from https://www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories.

- 9.Taylor DH Jr., Fillenbaum GG, Ezell ME. The accuracy of medicare claims data in identifying Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(9):929–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodman RA, Posner SF, Huang ES, Parekh AK, Koh HK. Defining and measuring chronic conditions: imperatives for research, policy, program, and practice. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services. Multiple chronic conditions - a strategic framework: optimum health and quality of life for individuals with multiple chronic conditions. Washington, DC, December, 2010. Accessed at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ash/initiatives/mcc/mcc_framework.pdf on 5/7/2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139–e596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chamberlain AM, Dunlay SM, Gerber Y, et al. Burden and Timing of Hospitalizations in Heart Failure: A Community Study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(2):184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunlay SM, Redfield MM, Weston SA, et al. Hospitalizations after heart failure diagnosis a community perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(18):1695–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manemann SM, Chamberlain AM, Roger VL, et al. Multimorbidity and functional limitation in individuals with heart failure: a prospective community study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(6):1101–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roger VL. Epidemiology of heart failure. Circ Res. 2013;113(6):646–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson SL, Tong X, King RJ, Loustalot F, Hong Y, Ritchey MD. National Burden of Heart Failure Events in the United States, 2006 to 2014. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(12):e004873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alzheimer’s Disease International. The global voice on dementia. World Azheimer Report 2015. The Global Impact of Dementia - an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. Executive Summary. Accessed at: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/worldalzheimerreport2015summary.pdf 5/7/2021.

- 19.Chaudhry SI, Wang Y, Gill TM, Krumholz HM. Geriatric conditions and subsequent mortality in older patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(4):309–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu C, Winblad B, Marengoni A, Klarin I, Fastbom J, Fratiglioni L. Heart failure and risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):1003–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haring B, Leng X, Robinson J, et al. Cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline in postmenopausal women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(6):e000369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noale M, Limongi F, Zambon S, Crepaldi G, Maggi S, Group IW. Incidence of dementia: evidence for an effect modification by gender. The ILSA Study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(11):1867–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rusanen M, Kivipelto M, Levalahti E, et al. Heart diseases and long-term risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a population-based CAIDE study. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2014;42(1):183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adelborg K, Horvath-Puho E, Ording A, Pedersen L, Toft Sorensen H, Henderson VW. Heart failure and risk of dementia: a Danish nationwide population-based cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(2):253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roger VL. The heart-brain connection: from evidence to action. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(43):3229–3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tublin JM, Adelstein JM, Del Monte F, Combs CK, Wold LE. Getting to the heart of alzheimer disease. Circ Res. 2019;124(1):142–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gottesman RF, Albert MS, Alonso A, et al. Associations between midlife vascular risk factors and 25-year incident dementia in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(10):1246–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jefferson AL, Beiser AS, Himali JJ, et al. Low cardiac index is associated with incident dementia and alzheimer disease: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2015;131(15):1333–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jefferson AL, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, et al. Cardiac index is associated with brain aging: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2010;122(7):690–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jefferson AL, Tate DF, Poppas A, et al. Lower cardiac output is associated with greater white matter hyperintensities in older adults with cardiovascular disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):1044–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovell J, Pham T, Noaman SQ, Davis MC, Johnson M, Ibrahim JE. Self-management of heart failure in dementia and cognitive impairment: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;19(1):99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hickman L, Ferguson C, Davidson PM, et al. Key elements of interventions for heart failure patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: A systematic review. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020;19(1):8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barnes DE, Zhou J, Walker RL, et al. Development and Validation of eRADAR: A Tool Using EHR Data to Detect Unrecognized Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(1):103–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(3):321–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, Williams SP, Singh H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(4):306–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Rocca WA, Larson EB, Ganguli M. Passive case-finding for Alzheimer’s disease and dementia in two U.S. communities. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(1):53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Focus on Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Access at https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Current-Research/Focus-Disorders/Alzheimers-Related-Dementias December 28, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1. Diagnosis codes used to identify Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease Related Dementias