Abstract

The discovery in 1987/1988 and 1990 of the cell-surface receptor KIT and its ligand, stem cell factor (SCF), were critical achievements in efforts to understand the development and function of multiple distinct cell lineages. These include hematopoietic progenitors, melanocytes, germ cells, and mast cells, which all are significantly affected by loss-of-function mutations of KIT or SCF. Such mutations also influence the development and/or function of additional cells, including those in parts of the CNS and the interstitial cells of Cajal (that control gut motility). Many other cells can express KIT constitutively or during immune responses, including dendritic cells, eosinophils, ILC2 cells, and taste cells. Yet the biological importance of KIT in many of these cell types largely remains to be determined. We here review the history of work investigating mice with mutations affecting the W locus (that encodes KIT) or the Sl locus (that encodes SCF), focusing especially on the influence of such mutations on mast cells. We also briefly review efforts to target the KIT/SCF pathway with anti-SCF or anti-KIT antibodies in mouse models of allergic disorders, parasite immunity, or fibrosis in which MCs are thought to play significant roles.

Keywords: Allergic disorders, KIT, mast cells, parasite immunity, stem cell factor (SCF)

Introduction

The importance of mutations at both the W (white spotting) locus and Sl (the steel) locus have interested mouse geneticists for many years1. Russell is credited with proposing that the W locus encoded a receptor for a growth factor needed by melanocytes, germ cells, and hematopoietic cells whereas Sl encoded the ligand for that receptor1. This idea was proposed based in part on the observations that the hematopoietic defects in mice with two mutations at W, but not those in mice with two mutations at Sl (which also exhibited defects in hematopoiesis), could be repaired by the adoptive transfer of bone marrow cells of the wild type mice1. By contrast, the transfer of hematopoietic cells from mice with two mutations at Sl could repair the defective hematopoiesis expressed in W mutant mice1. Yukihiko Kitamura and colleagues then made the important observations that mice with two loss-of-function mutations at either W (i.e., WBB6F1-W/Wv mice) or Sl (i.e., WCB6F1-Sl/Sld mice) also were profoundly mast cell (MC) deficient, and that the W mutant mice, but not the Sl mutant mice, could be cured of their MC deficiency by adoptive transfer of normal hematopoietic stem cells2, 3.

In 1988, the exciting discovery that the receptor Kit4 was encoded at W5, 6 stimulated the efforts of several groups to identify the gene for that receptor’s ligand. In 1990, 4 different groups simultaneously reported evidence that the ligand for Kit was encoded by the Sl locus7–14. Once Kit and its ligand, now known primarily as stem cell factor (SCF), but called Kitl in the mouse, were discovered, many studies ensued probing the mechanism of interactions between Kit and SCF and the effects of SCF on various Kit+ cells. It soon became clear that some cells expressed Kit transiently (such as hematopoietic progenitors, which generally lost Kit expression as the cells matured into various hematopoietic lineages15, 16) whereas other cells, such as MCs, expressed Kit constitutively15–20.

It is now clear that KIT and its ligand participate in the development and function of multiple distinct cell lineages, including hematopoietic progenitors, melanocytes, germ cells, and MCs. Mutations in Kit or SCF (Kitl) also influence the development and/or function of additional cells, including melanoblasts, some cells in the central nervous system (CNS), and the interstitial cells of Cajal, that control gut motility. We here review the history of work investigating mice with mutations affecting the W locus that encodes KIT or the Sl locus that encodes SCF, focusing especially on the influence of such mutations on MCs. We also briefly review efforts to target the KIT/SCF pathway with anti-SCF or anti-KIT antibodies in mouse models of allergic disorders, parasite immunity, or fibrosis in which MCs are thought to play major roles.

Mast cell-deficiency in W and Sl mice

MC-deficient mice were first described in the late 1970s by Yukihiko Kitamura and his colleagues. These studies took advantage of WBB6F1-W/Wv mice2, that had one W allele (on the C57BL/6 background, homozygous W mutations were known to be lethal) and one Wv allele, which impaired but did not fully eliminate the function of Kit (now known to be the W product). They reported that MC numbers in adult WBB6F1-KitW/W-v (W/Wv)2 and WCB6F1/J-KitlSl/Sl-d (Sl/Sld)3 mice were <1% of the wild type levels and that the MC-deficiency in W/Wv mice can be repaired by adoptive transfer of bone marrow cells from wild type2 or Sl/Sld 3 mice; by contrast, the transfer of wild type bone marrow cells to Sl/Sld mice did not restore MCs in these mice. They also found that MCs appeared in the skin of MC-deficient W/Wv mice when it was engrafted onto Sl/Sld mice, but not in Sl/Sld skin that had been engrafted onto W/Wv mice3.

Findings from these bone marrow transplantation and skin engraftment experiments confirmed the hematopoietic origin of the MC lineage. They also supported Kitamura’s hypothesis that the MC-deficiency in W/Wv mice was caused by an intrinsic defect of their MC precursors in the bone marrow, whereas the tissue microenvironment required for proper MC development and differentiation was impaired in Sl/Sld mice. In addition to their MC deficiency, W/Wv and Sl/Sld mice exhibited remarkably similar phenotypic abnormalities in fertility, pigmentation and hematopoiesis, despite carrying distinct mutations in W and Sl alleles. These observations suggested interactions between gene products of W and Sl alleles, and that such interactions were critically important for the development of germ cells, melanocytes, and hematopoietic cell lineages, including MCs1, 21.

KIT receptor and its ligand SCF

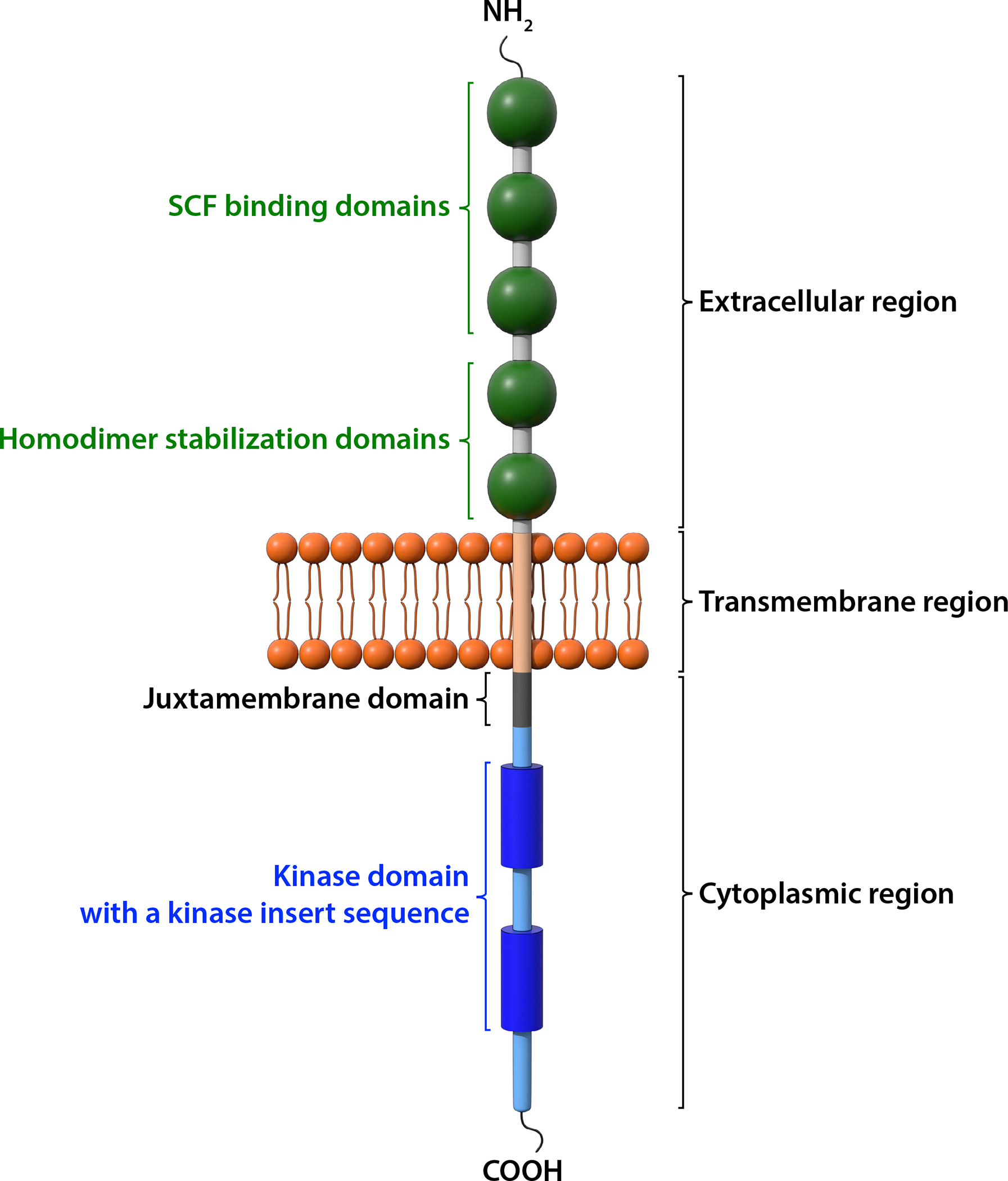

The molecular mechanisms accounting for the abnormal phenotypes of W and Sl mice became clear when their gene products were identified and characterized to have a receptor-ligand relationship. The search for a functional link between W and Sl gene products started with the localization of KIT (CD117) to the W (Dominant white spotting) locus in mice by genetic mapping5, 6. KIT is a type III cell surface tyrosine kinase receptor, consisting of 5 immunoglobulin-like extracellular domains, a transmembrane region, and an intracellular tail with tyrosine phosphorylation sites and kinase activity (Fig. 1). KIT is expressed primarily on the progenitors of the reproductive, hematopoietic, and melanogenesis systems (Table 1). While most of the terminally differentiated cells of hematopoietic origin essentially lose KIT expression on their surface, KIT expression remains high on MCs throughout their developmental history22, 23. Nevertheless, some KIT has been detected on the surface of other differentiated cells, including dendritic cells24, eosinophils25, ILC2 cells26 and taste cells27, either constitutively or during immune reactions (Table 1). KIT is also highly expressed in parts of the CNS28, 29 and in the interstitial cells of Cajal that control gut motility30 (Table 1).

Figure 1. Structure of the KIT receptor.

KIT is a member of the receptor tyrosine kinase III family. It consists of an extracellular region, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic region. There are five immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains in the extracellular region. The first three Ig-like domains bind to SCF and the 4th and 5th Ig-like domains facilitate dimerization upon ligand binding. The intracellular tyrosine kinase domain is interrupted by a hydrophilic insert sequence. The juxtamembrane domain, the kinase domain and the carboxyl terminal tail are involved in signal transduction when the KIT receptor is activated.

Table 1.

Cellular expression of KIT*

| Activated CD8+ T cells |

| Central Nervous System (mainly in cerebellum) |

| Certain epithelial cells |

| Dendritic cells |

| Eosinophils |

| Germ cells |

| Hematopoietic stem cells and early progenitors |

| ILC2 cells |

| Interstitial cells of Cajal |

| Mast cells |

| Melanocytes |

| Taste cells |

Listed alphabetically, not based on level of expression.

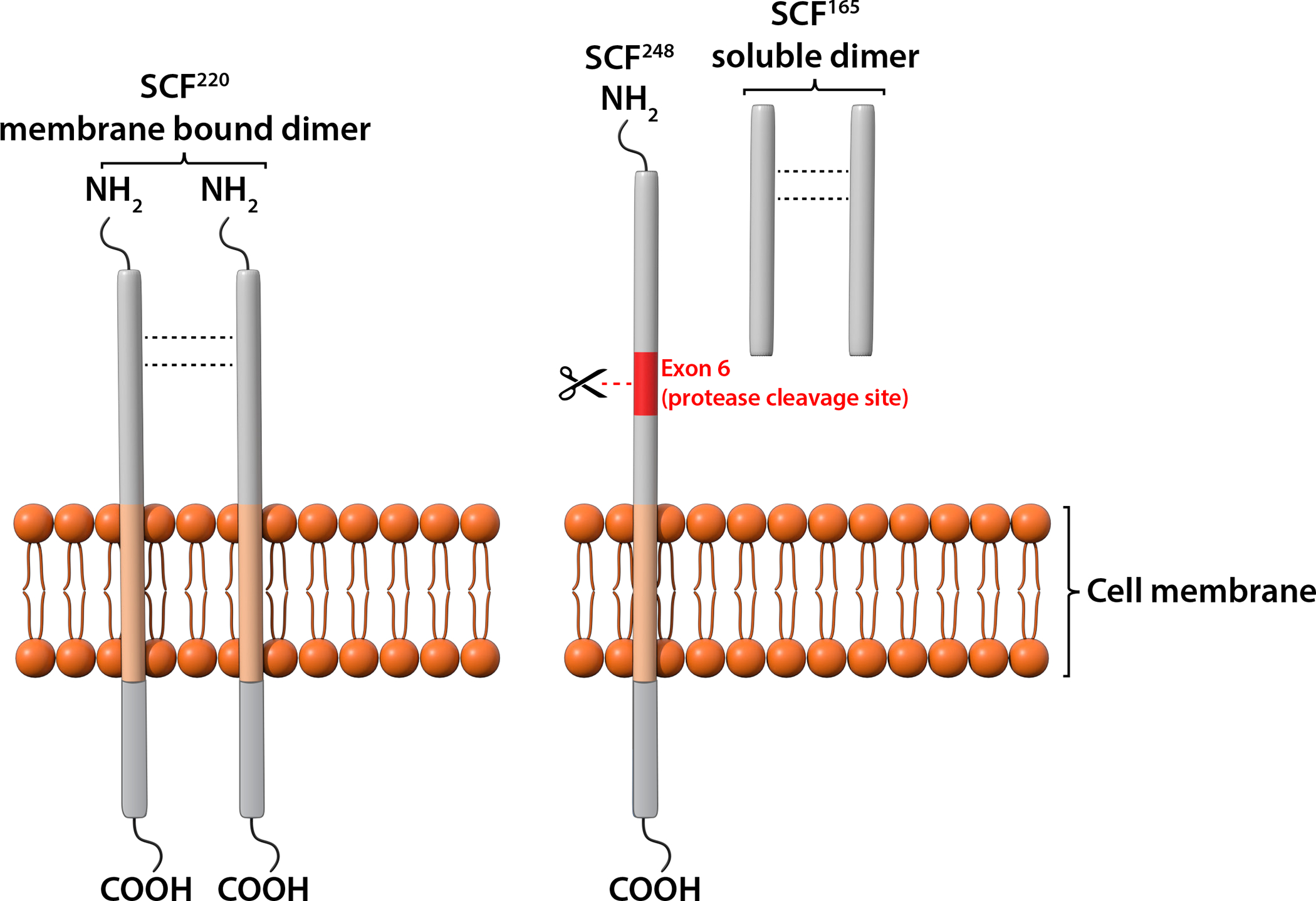

In just 2 years after the localization of KIT to the W locus, several groups independently identified Sl (Steel) encoded SCF as the ligand for KIT7–14. SCF is a potent hematopoietic growth factor with strong activities in promoting MC growth7–14. SCF is expressed mainly by keratinocytes, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells (Table 2). This growth factor supports proliferation, migration, survival, and differentiation of germ cells, melanocytes and hematopoietic cells. SCF maps to chromosome 12 in humans and chromosome 10 in mice and is encoded by 9 exons in both mouse and human. SCF is produced in two main isoforms, SCF220 and SCF248, by alternative splicing31 (Fig. 2). Both SCF220 and SCF248 isoforms encode membrane-bound SCF, which consists of intracellular, transmembrane and extracellular domains. SCF248 has an additional protease cleavage site that is encoded by exon 6 and that can be cleaved by chymase, metalloprotease 9, and proteases of the ADAMs family to generate 165 amino acid soluble SCF16 (Fig. 2). Soluble SCF can also be generated, with less efficiency, from SCF220 by the cleavage of exon 7 (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Cellular expression of SCF*

| Bone marrow stromal cells and macrophages |

| Endothelial cells |

| Eosinophils |

| Fibroblasts |

| Keratinocytes |

| Mast cells |

| Smooth muscle cells |

Listed alphabetically, not based on level of expression.

Figure 2. Structure of two SCF isoforms.

Two main SCF isoforms, SCF220 and SCF248, are produced by alternative splicing. Both SCF220 and SCF248 consist of an extracellular domain, a transmembrane domain and an intracellular tail. Exon 6 in SCF248 encodes a protease sensitive site that can be cleaved to generate soluble SCF165. Minor amounts of soluble SCF also can be generated from SCF220 by an alternative protease cleavage site encoded by exon 7 (not depicted). Biologically active SCF is a non-covalent dimer in either membrane-associated or soluble form.

The active form of SCF is a noncovalently associated homodimer which binds to the first 3 extracellular Ig domains of the KIT receptor16. The 4th and 5th extracellular Ig domains of the KIT help stabilize the homo-dimeric state of the receptors upon ligand binding16. Similar to other tyrosine kinase receptors, dimerization or oligomerization is required for the activation of the intrinsic tyrosine kinase and transphosphorylation of the KIT receptors16. Soluble SCF in circulation exists mostly in a monomeric form that does not activate KIT32. The expression of SCF220 and SCF248 is tissue-specific15 (Table 2). Membrane and soluble SCF homodimers can each activate KIT, but have different biological functions in hematopoiesis with a more critical role for SCF248 in MC development and survival33, 34. Hence, blocking soluble SCF specifically by anti-SCF248 antibody has been used to probe the importance of SCF/KIT interactions in regulating MC functions in animal models of asthma26, pulmonary fibrosis35, and food allergy36.

Mast cell-deficient mice with KIT mutations and newer models of mast cell deficiency

Because the MC-deficiency in W mutant mice can be “repaired” by systemic or local engraftment of MC precursors or differentiated MC populations, these mice have been widely used to investigate MC biology37, 38. Such studies have been used to advance knowledge about MC functions (either beneficial or detrimental) and the regulation of MC developmental pathways. Most work with MC-deficient mice was conducted in WBB6F1-KitW/W-v or C57BL/6-KitW-sh/W-sh mice carrying mutations that affect the structure or expression of KIT. However, because these mutant mice also express many other non-MC abnormalities due to their Kit mutations, we have recommended that in vitro-derived MCs be adoptively transferred into WBB6F1-KitW/W-v or C57BL/6-KitW-sh/W-sh mice to produce “MC knock-in” mice37, 38. This approach permits comparison of results in three groups of mice: Kit mutant MC-deficient mice, the corresponding wild type mice, and Kit mutant mice engrafted with populations of wild type or genetically-altered MCs. If any difference in expression of a biological response in Kit mutant MC-deficient mice and wild type mice is normalized by the engraftment of MCs into the Kit mutant mouse (particularly if similar results are obtained with both WBB6F1-KitW/W-v and C57BL/6-KitW-sh/W-sh mice), this can be interpreted as evidence favoring an important contribution of MCs in the biological response under investigation37, 38.

However, when interpreting findings using this “MC knock-in” approach, one must keep in mind that the numbers, anatomical location and phenotype of the transferred MCs may not be identical to those in the corresponding wild type mice37, 38. Prompted by these concerns, and considering the many phenotypic abnormalities unrelated to MCs in Kit mutant mice, alternative mouse models with inducible or constitutive MC-deficiencies that are independent of Kit mutations were generated by several groups37–41. These newer models, which have been reviewed in detail37, 39–41, employ a variety of approaches for achieving more selective depletion of mast cells than occurs in the various Kit mutant animals. Some of these mice (e.g., Cpa3cre mice) are now available on inbred C57BL/6 or BALB/c genetic backgrounds42 and offer several advantages over Kit mutant mice, in that they are more selective in depleting mast cells while sparing other cell types that express Kit. They are particularly useful for investigations of the MCs’ roles in tissue sites, e.g., the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system, which are difficult to repair of their MC-deficiency by MC engraftment. However, these Kit-independent MC-deficient mice may also have functionally significant defects in other cell lineages, such as basophils37, 39–41.

Regulation of KIT expression and signaling in mast cells

Several intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms are known to modulate KIT expression in MCs. MITF (microphthalmia [mi] associated transcription factor) encoded by the mi locus is a basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factor critical for KIT expression and development of MCs43, 44. Also, KIT signaling controls MITF expression in MCs at posttranscriptional levels, with the involvement of miR-539 and miR-38145. GATA2 is another transcription factor implicated in KIT expression in MCs, and it has been reported that MCs from GATA-2-deficient people express reduced levels of KIT and FcεRI and exhibit lower IgE-mediated degranulation46. 3BP2 (SH3-binding protein 2) is a cytoplasmic adaptor protein that positively regulates FcεRI signaling and degranulation in MCs47. Silencing of 3BP2 in HMC-1 cells (an immature human MC leukemia cell line with activating mutations in KIT), LAD2 cells (another human MC line, but with WT KIT), and CD34+ progenitor-derived human MCs impairs KIT signaling and affects PI3-kinase and MAPK pathways48. Inhibition of 3BP2 also reduces expression of KIT as well as MITF, leading to more apoptosis in these MCs48. Thus, 3BP2 is important for human MC survival by directly controlling KIT expression and KIT-mediated signal transduction48.

KIT levels in MCs are modulated by extrinsic factors such as cytokines, growth factors and environmental pollutants. IL-4 and IL-10 can suppress KIT expression in mouse bone marrow-derived cultured MCs49 and in HMC-150. Addition of IL-4 to fetal liver cells grown in SCF-containing medium markedly down-regulates surface KIT and interferes with MC growth and development51. In mouse bone marrow-derived cultured MCs, TGF-β down-regulates KIT via the transcription factor Ehf 52. Exposure of mouse bone marrow-derived MCs to cigarette smoke-conditioned medium reduces KIT and FcεRI expression, granularity and IgE/antigen-mediated degranulation and cytokine production in these cells53. Cigarette smoke contains over 4,700 chemical compounds, but the compound(s) responsible for KIT suppression was not identified in that study53.

SCF binding of KIT downregulates KIT and triggers several complex membrane and intracellular signaling events in MCs16, 54, 55. Like other tyrosine kinase receptors, crosslinking of KIT by SCF leads to receptor dimerization and conformational changes that facilitate trans-phosphorylation/auto-phosphorylation of the receptors by KIT’s intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity16, 55. These phosphorylated tyrosine residues then serve as docking sites for intracellular signaling molecules, such as Src family kinases (LYN, FYN), and Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-containing intracellular proteins (p85 subunit of PI3K, SHC, GRB2, GAB2, PLCγ, SHP2, etc). The recruitment and activation of these intracellular proteins propagates subsequent downstream signaling cascades, leading to activation of RAS/RAF/MEK/MAPK, JAK-STAT, PI3K/AKT/RPS6K, and PLC/PKC pathways. The KIT signaling circuits are remarkably similar to signaling pathways elicited by FcεRI crosslinking, except that the recruitment and phosphorylation SYK and adaptor protein LAT are associated with the activation of FcεRI but not KIT55. Phosphorylation of the transmembrane adaptor protein, NTAL, is a prerequisite for MC degranulation following FcεRI aggregation and is involved in SCF potentiation of antigen/IgE-induced degranulation56. However, KIT and FcεRI appear to utilize different mechanisms to induce NTAL phosphorylation: FcεRI utilizes LYN and SYK for NTAL phosphorylation whereas KIT can phosphorylate NTAL directly56.

KIT expression and activation have to be tightly regulated in order to maintain MC homeostasis. There are several mechanisms by which KIT signaling can be downregulated. Upon SCF binding, KIT is rapidly internalized and degraded via CBL (an E3 ubiquitin ligase) in an ubiquitin-dependent mechanism16. Inactivation can also be achieved by a negative feedback loop where activation of protein kinase C results in serine phosphorylation and inactivation of KIT16. Dephosphorylation of KIT by intracellular tyrosine phosphatases, e.g. SHP1, can also inactivate KIT16. ALDH2 (Mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase)-deficient MCs have reduced SHP1 activities. These cells over-react to SCF stimulation of proliferation and IL-6 production with enhanced KIT phosphorylation and signaling57. On the other hand, the tyrosine phosphatase, SHP2, can enhance KIT signaling in MCs, by upregulation of ERK and downregulation of Bim 58, and SHP2 can promote survival and chemotaxis toward SCF59. Finally, RABGEF1 is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for RAB5 and forms a complex with rabaptin-5 that is critical for endocytic membrane fusion. RABGEF1-deficient MCs exhibit enhanced SCF/KIT signal transduction and cellular responses60.

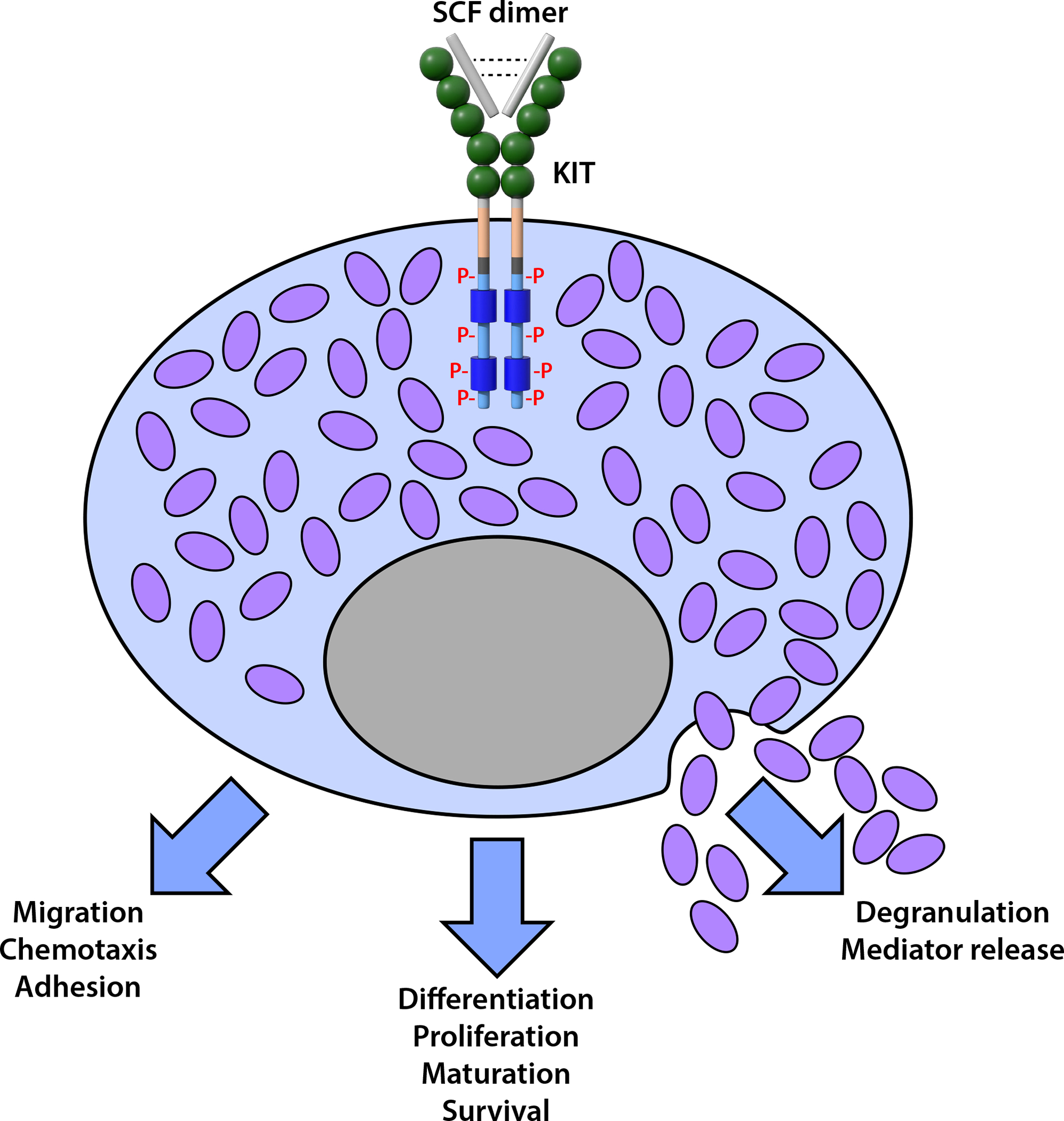

Regulation of mast cell homeostasis by KIT-SCF interactions

MCs retain high levels of KIT throughout all stages of their development. Interactions of SCF and KIT therefore influence multiple aspects of MC cellular responses (Fig. 3) and dysregulation of SCF/KIT activation will significantly perturb MC homeostasis. As described above, loss of function mutations in SCF/Sl or KIT/W result in MC deficiency; by contrast, gain of function mutations in KIT lead to MC hyperplasia and activation, as seen in mastocytosis and MC activation syndromes61–63.

Figure 3. Pleiotropic effects of SCF-KIT interactions on mast cell development and function.

The binding of the SCF homodimer induces dimerization and phosphorylation of the KIT receptor, which can promote the differentiation, proliferation, maturation, and/or enhanced survival of cells in the MC lineage. SCF-KIT interactions can also activate MCs to express cellular functions and promote MC migration, chemotaxis, and adhesion, and, at high concentrations, MC degranulation and mediator release. P: phosphorylated tyrosine

Although immortal human MC lines arising from cells with constitutively active KIT are available for in vitro experiments, the discovery of SCF as a key MC growth factor has helped establish culture methods for the generation of MCs carrying normal KIT function. These can be used for biochemical analyses and functional studies that otherwise would be difficult to perform with the limited numbers of MCs that can be obtained from tissues. These in vitro cultured human MCs have been generated from progenitors in cord blood64–66, bone marrow18, 67, 68, peripheral blood18, 66, 68, 69, embryonic stem (ES) cells70, and fetal liver51 in SCF-containing medium. Collectively, these reports have demonstrated that the growth and development of human MCs in vitro depends on SCF, although development of human MC progenitors from peripheral blood in IL-3 and IL-6, but in the absence of SCF, has been reported71. Although mouse MC development in culture can be supported by IL-3 alone without added SCF, the addition of SCF markedly potentiates the growth of mouse MCs in vitro. Thus, mouse MCs can be generated from fetal skin72, fetal liver73, bone marrow74, peritoneal cells75 or ES cells76 in SCF or SCF plus IL-3.

In murine rodents and humans, the phenotype, numbers and functions of MCs generated in SCF can be profoundly influenced by the presence of other cytokines, such as IL-3, IL-4, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, etc77, 78. Mouse bone marrow-derived cultured MCs developed in IL-3 alone or in IL-3+SCF remain phenotypically immature. These MCs are negative with safranin and berberine staining, produce almost no heparin or the chymases, MMCP-4 and −278-80. On the other hand, fetal skin- and ES cell-derived cultured MCs generated in SCF+IL-3 exhibit phenotypic characteristics that more closely mimic a “mature phenotype” like that of connective tissue type MCs (CTMCs), including positive staining for safranin and berberine sulfate, and degranulation in response to substance P and compound 48/8072, 76. MCs with a more mature phenotype also can be generated in vitro by culturing mouse bone marrow cells in SCF alone or sequentially in IL-3 followed by SCF79–81.

A recent report has identified in mouse lung two distinct MC populations based on β7 integrin expression82. MCs with constitutive β7Low expression are heavily granulated, express CTMC signature genes, and remain static in numbers during inflammation. On the other hand, β7High MCs are hypo-granulated, enriched for gene transcripts associated with MMCs, and contribute to allergic airway inflammation. These inducible β7High MCs increase in numbers and exhibit transcriptional changes following type 2 inflammatory stimulation. While multiple mediators and cytokines are likely to induce development and activation of β7High MCs, SCF/KIT-dependent TGF-β stimulation of IL-3-derived BMCMCs was shown to be an important signal that can induce recapitulation of certain aspects of the inflammatory phenotype of β7High MCs in vivo82.

Transcriptome analysis shows that the sequential culture in IL-3 followed by SCF partially programs immature bone marrow-derived MCs toward having a CTMC phenotype through transcriptional upregulation of heparin sulfate biosynthesis enzymes, certain MC-specific proteases, MRGPR family members, and transcription factors required for MC lineage determination81. Exposure of IL-3-derived MCs to SCF and IL-4 greatly enhances their expression of neurokinin 1 receptors and increases sensitivity to substance P stimulation83, 84. In addition to supporting the development of MCs from precursors, SCF can induce proliferation of fully differentiated MCs in vivo85 and in vitro79, sustain MC survival by suppressing apoptosis86, 87, act as a chemotactic factor to induce MC migration88–90, and promote MC adhesion to fibornectin91.

The in vivo effects of SCF on MCs have been demonstrated in murine rodents and humans. SCF injections induce MC development in SCF-deficient Sl/Sld mice14, as well as expansion of MC populations in wild type mice79, 85, 92, rats85, cynomolgus monkeys93 and human subjects94, 95 through the recruitment and/or local expansion of MC progenitors. However, continuous SCF administration is required to maintain high numbers of MCs, as such SCF-induced MCs are eliminated by apoptosis and MC numbers decline rapidly to nearly baseline levels after cessation of SCF treatments92, 93.

In addition to growth and development, MCs are activated by SCF to express functional responses. SCF can induce MCs to secrete cytokines and mediators in vitro96–100 and activate MCs to degranulate and express cellular function in vivo94, 95, 97, 101. However, MC mediator release induced by SCF can result in undesirable side effects that limit the therapeutic value of this growth factor in promoting hematopoiesis and other applications. To mitigate MC side effects, Ho et al. engineered an SCF variant that selectively stimulates hematopoietic progenitors over MCs102. This SCF partial agonist was shown to support hematopoietic expansion but not SCF/MC-mediated anaphylaxis in mice102.

In MCs, SCF/KIT interactions synergize with the activation of other receptors, such as FcεRI96, 103–107, IL-33/ST2108 and TLR109. In vivo, short-term treatment with SCF can potentiate IgE-mediated mediator release by MCs whereas chronic SCF exposure increases MC numbers but reduces certain aspects of IgE-dependent anaphylaxis110. In vitro, prolonged incubation of mouse bone marrow-derived MCs with SCF reduces IgE-dependent degranulation and cytokine production, and is associated with ineffective cytoskeletal reorganization and down-regulation of expression of the Src kinase Hck111.

Targeting the KIT/SCF pathway in mast cell-associated diseases

The use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) for treatment of mastocytosis and mast cell activation disorders in humans is covered in other contributions in this series112–116 and elsewhere117. Briefly, the clinical value of both agents that act on WT KIT (e.g., imatinib) and those that act on the KIT D816V mutant (e.g., midostaurin and avaprotinib) has been demonstrated in the treatment of appropriate advanced systemic mastocytosis patients112–117. By contrast, the clinical utility of KIT/SCF blocking antibodies in mast cell-associated disorders awaits definitive demonstration. We therefore will focus here mainly on experimental studies that have targeted the KIT/SCF pathway with anti-SCF or anti-KIT antibodies in mouse models of allergic disorders, parasite immunity, or fibrosis in which MCs are thought to play a major role. We will also briefly mention promising ongoing studies of a humanized anti-KIT monoclonal antibody in chronic inducible or chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Given the adverse effects of MCs in allergic diseases, inhibition of KIT/SCF-induced MC proliferation and activation would seem to be a plausible approach for the prevention or treatment of some of these disorders. However, there are many other approaches that are now used (or in development) to treat diseases in which MCs and IgE are importantly involved. These include existing agents that neutralize MC-derived mediators (e.g., anti-histamines, anti-leukotrienes) or reduce expression and activation of FcεRI (using anti-IgE antibodies such as Omalizumab or Ligelizumab), drugs such as gluco-corticosteroids (that, among other effects, stabilize MCs), and agents in development that suppress key signaling molecules (e.g., BTK, SYK) downstream of MC receptor activation (using small molecule inhibitors) or enhance relevant inhibitory mechanisms (e.g., Siglec 8; CD200R; CD300a; FcγRIIb)118, 119.

Nevertheless, blocking the KIT/SCF pathway with anti-KIT/anti-SCF antibodies has been explored in models of mastocytosis120, allergy26, 36, 121, 122, and other settings involving MCs35, 123, 124. Another approach to block KIT signaling and activation in MCs employs a bispecific antibody linking KIT with the inhibitory receptor CD300a125. This bispecific antibody can inhibit SCF-induced human MC differentiation, activation and survival, abrogate constitutive KIT activation in HMC-1 cells, and block skin reactions induced by SCF injections in mice125. However, it remains to be determined whether, and in which settings, targeting of the KIT/SCF pathway may have advantages over other treatment approaches now being used or in development.

Allergic disorders

Work in MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh and/or KitW/W-v mice has supported the contribution of MCs in the development of multiple features of chronic asthma26, 126, 127. While the detrimental effects of MCs are primarily mediated through IgE/FcεRI aggregation, FcRγ–independent mechanisms of MC activation can also significantly contribute to elevations of serum histamine and increased numbers of airway goblet cells associated with chronic allergic airway inflammation in mice126. The development of many FcRγ-dependent and some FcRγ-independent features of allergic airway disease also depends on MC expression of IFN-γR127. In addition to FcRγ– and IFN-γR-mediated activation, MCs’ responses to SCF can contribute to the severity of allergic airway inflammation, hyper-responsiveness and remodeling26, 54. As fibroblasts in asthmatic lungs overexpress predominately the SCF248 isoform, anti-SCF248 antibody that specifically targets exon 6 of the SCF248 was generated to explore the importance of soluble SCF in allergic asthma. In a mouse model of chronic asthma elicited by cockroach antigen, anti-SCF248 antibody attenuates airway inflammation, airway hyper-responsiveness, Th2 cytokine levels, mucus deposition, and numbers of MCs and other KIT+ cells, ILC2 and eosinophils, in the lungs26. Targeted deletion of SCF specifically in fibroblasts has similar effects as those observed with anti-SCF248 antibody in this chronic asthma model26. This study demonstrated that fibroblast-derived SCF, mainly SCF248, can regulate effector function of MCs as well as KIT+ ILC2 in allergic airway inflammation and remodeling26.

Intestinal MC hyperplasia and activation is a hallmark of food allergy128. Brandt et al. used an anti-KIT blocking antibody (ACK2) to deplete intestinal MCs and plasma MMCP1121. Such anti-KIT treatment also blocked augmented intestinal permeability and diminished oral allergen-induced diarrhea in mice121. In another study, anti-SCF248 antibody treatment attenuated intestinal anaphylaxis (i.e., reduced diarrhea and hypothermia) with reductions in Th2 cytokines, ILC2, eosinophils and intestinal MCs in a mouse model of food allergy elicited by ovalbumin sensitization and intragastric challenges36.

CDX-0519 (Celldex Therapeutics) is a humanized anti-KIT monoclonal antibody that inhibits SCF-mediated activation by binding to the extracellular dimerization domain of KIT129, 130. This antibody is currently being evaluated for safety and efficacy in chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04538794) and chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU) (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04548869). Terhorst-Molawi et al. recently reported that a single dose of CDX-0159 resulted in sustained control of urticaria and reductions of cutaneous MC numbers and circulating tryptase and SCF in antihistamine refractory CIndU122.

Parasite immunity

Anti-SCF and anti-KIT blocking antibodies have been used to investigate the contribution of MCs in parasite immunity. These blocking antibodies abrogate MC hyperplasia induced by the parasite Trichinella (T.) spiralis and result in delayed worm expulsion123. By contrast, while anti-SCF antibody treatment diminish intestinal MC hyperplasia in rats infected with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (or T. spiralis), such treatment decreased parasite egg production during N. brasiliensis infection124. These findings indicate that while activation of SCF/KIT and MCs is protective for certain parasite infection, the effects of SCF and/or MCs may actually favor parasite fecundity in some settings.

Fibrosis

The SCF/KIT pathway also has been implicated in pulmonary fibrosis and remodeling. Lung fibroblasts from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) patients and from mice treated with bleomycin preferentially express the SCF248 isoform35. In fibroblast-MC (LAD2) coculture, anti-SCF248 antibody decreased the expression of COL1A1, COL3A1, and FN1 transcripts in IPF, but not normal, lung-derived fibroblasts. Administration of anti- SCF248 after bleomycin instillation in mice significantly reduced KIT+ MCs, eosinophils, and ILC2 cells and expression of profibrotic genes (col1al, fn1, acta2, tgfb, and ccl2 transcripts)35.

However, like tyrosine kinase inhibitors, the effects of anti-SCF and anti-KIT blocking antibodies do not necessarily reflect solely their actions on MCs. For example, SCF can activate ILC2 cells to produce key allergic cytokines and the effects of anti-SCF antibody in chronic allergic inflammation could be attributable, at least in part, to ILC2 inhibition26. Also, anti-KIT antibody could potentially trigger MC degranulation. In a phase 1 clinical study that examined the anti-KIT antibody drug conjugate for the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), some participants developed rapid hypersensitivity reactions with elevated serum tryptase after infusion131. This anti-KIT antibody drug conjugate was shown to induce degranulation of peripheral blood derived MCs by co-ligation of FcγR and KIT131.

Conclusions

The identification of the receptor Kit as the product of the W (white spotting) locus in the mouse and SCF (Kitl), the Kit ligand, as the product of the mouse Sl (steel) locus were significant achievements. These discoveries have helped to explain many of the phenotypic abnormalities of the mutant mice that have been most central to our understanding of the origin and development of the MC lineage: WBB6F1-W/Wv mice (now known as WBB6F1-KitW/W-v mice) and WCB6F1-Sl/Sld mice (now known as WCB6F1/J-KitlSl/Sl-d mice). And while Kit and its ligand are most strongly involved in the development of hematopoietic precursors, germ cells, melanocytes and MCs, MCs represent an example (perhaps the most striking example) of a hematopoietic cell lineage that retains high levels of expression of Kit on the surface both throughout its development and as “mature” cells residing in the tissues.

However, it has become evident that KIT and its ligand participate in the development and function of multiple distinct cell lineages. These include cells in parts of the CNS, the interstitial cells of Cajal in the gut, taste cells, and several hematopoietic cells in addition to MCs, including dendritic cells, eosinophils, and ILC2 cells. While the importance of KIT and its ligand in influencing the biology of some of these cell types remains to be fully understood, the potential diversity of the roles of this receptor-ligand interaction in regulating multiple distinct lineages should always be kept in mind when evaluating the effects of attempting to antagonize such interactions therapeutically. Many of the concepts developed in mouse studies now appear also to be relevant in humans, including in various human diseases. On the other hand, one should also always consider the possibility of differences in the biology of interactions between KIT and its ligand in mice versus humans.

Considering all of these caveats, when can targeting KIT and/or its ligand be therapeutically useful? If KIT is mutated and has increased function, as in many variants of human mastocytosis, then using agents that target KIT (albeit not fully specifically) can have clinical benefit113–117. Other settings may be certain forms of severe refractory asthma, in which treatment with imatinib (that targets KIT, and other receptors) can have benefit132, 133, or instances of severe mast cell activation112. Finally, recent studies of a humanized anti-KIT monoclonal antibody that inhibits SCF-mediated activation show promise in sustained control of chronic inducible urticaria122. But questions remain as to whether, and in which other conditions, the specific targeting of KIT (or SCF) can be clinically useful - and whether the side effects of such treatment will be tolerable.

Abbreviations:

- acta2

actin alpha 2

- ADAM

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase

- ALDH2

mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase

- BMCMC

bone marrow-derived cultured mast cel

- 3BP2

SH3-binding protein 2

- BTK

bruton tyrosine kinase

- CBL

casitas B-lineage lymphoma

- ccl2

C-C motif chemokine ligand 2

- COL1A1

collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain

- COL3A1

collagen type 3 alpha 1 chain

- CNS

central nervous system

- CTMC

connective tissue type mast cell

- Ehf

ETS homologous factor

- ES

embryonic stem

- FcεRI

Fc epsilon receptor type I

- FcγR

Fc gamma receptor

- FcRγ

Fc receptor gamma chain

- FN1

fibronectin 1

- GAB2

GRB2-associated-binding protein 2

- GRB2

growth-factor receptor-bound protein-2

- HMC-1

human mast cell leukemia-1

- IFN-γR

interferon gamma receptor

- IL

interleukin

- ILC2

type 2 innate lymphoid cell

- IgE

Immunoglobulin E

- IPF

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- JAK

Janus kinase

- Kitl

KIT ligand

- LAD2

laboratory of allergic diseases 2

- LAT

linker for activation of T cells

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MC

mast cell

- MITF

microphthalmia associated transcription factor

- MMC

mucosal mast cell

- MMCP

mouse mast cell protease

- MRGPR

mas-related G protein-coupled receptor

- NTAL

non T cell activation linker

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLCγ

phospholipase C gamma

- RABGEF1

RAB guanine nucleotide exchange factor 1

- RPS6K

ribosomal protein S6 kinase

- SCF

stem cell factor

- SH2

Src homology 2

- SHC

Src homology and collagen

- SHP

tyrosine phosphatase

- Siglec 8

sialic acid binding Ig like lectin 8

- Sl

steel

- ST2

suppressor of tumorigenicity 2

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- SYK

spleen tyrosine kinase

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor beta

- Th2

T helper 2

- TKI

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- W

white spotting

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: Peter Valent: Consultancy (honoraria): Blueprint, Novartis, Deciphera, Celgene, Incyte; Research Grant: Celgene, Pfizer. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Russell ES. Hereditary anemias of the mouse: a review for geneticists. Adv Genet 1979; 20:357–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitamura Y, Go S, Hatanaka K. Decrease of mast cells in W/Wv mice and their increase by bone marrow transplantation. Blood 1978; 52:447–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitamura Y, Go S. Decreased production of mast cells in Sl/Sld anemic mice. Blood 1979; 53:492–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yarden Y, Kuang WJ, Yang-Feng T, Coussens L, Munemitsu S, Dull TJ, et al. Human proto-oncogene c-kit: a new cell surface receptor tyrosine kinase for an unidentified ligand. EMBO J 1987; 6:3341–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chabot B, Stephenson DA, Chapman VM, Besmer P, Bernstein A. The proto-oncogene c-kit encoding a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor maps to the mouse W locus. Nature 1988; 335:88–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geissler EN, Ryan MA, Housman DE. The dominant-white spotting (W) locus of the mouse encodes the c-kit proto-oncogene. Cell 1988; 55:185–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson DM, Lyman SD, Baird A, Wignall JM, Eisenman J, Rauch C, et al. Molecular cloning of mast cell growth factor, a hematopoietin that is active in both membrane bound and soluble forms. Cell 1990; 63:235–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Cho BC, Donovan PJ, Jenkins NA, Cosman D, et al. Mast cell growth factor maps near the steel locus on mouse chromosome 10 and is deleted in a number of steel alleles. Cell 1990; 63:175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flanagan JG, Leder P. The kit ligand: a cell surface molecule altered in steel mutant fibroblasts. Cell 1990; 63:185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang E, Nocka K, Beier DR, Chu TY, Buck J, Lahm HW, et al. The hematopoietic growth factor KL is encoded by the Sl locus and is the ligand of the c-kit receptor, the gene product of the W locus. Cell 1990; 63:225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin FH, Suggs SV, Langley KE, Lu HS, Ting J, Okino KH, et al. Primary structure and functional expression of rat and human stem cell factor DNAs. Cell 1990; 63:203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams DE, Eisenman J, Baird A, Rauch C, Van Ness K, March CJ, et al. Identification of a ligand for the c-kit proto-oncogene. Cell 1990; 63:167–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zsebo KM, Wypych J, McNiece IK, Lu HS, Smith KA, Karkare SB, et al. Identification, purification, and biological characterization of hematopoietic stem cell factor from buffalo rat liver--conditioned medium. Cell 1990; 63:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zsebo KM, Williams DA, Geissler EN, Broudy VC, Martin FH, Atkins HL, et al. Stem cell factor is encoded at the Sl locus of the mouse and is the ligand for the c-kit tyrosine kinase receptor. Cell 1990; 63:213–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broudy VC. Stem cell factor and hematopoiesis. Blood 1997; 90:1345–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lennartsson J, Ronnstrand L. Stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit: from basic science to clinical implications. Physiol Rev 2012; 92:1619–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirshenbaum AS, Goff JP, Kessler SW, Mican JM, Zsebo KM, Metcalfe DD. Effect of IL-3 and stem cell factor on the appearance of human basophils and mast cells from CD34+ pluripotent progenitor cells. J Immunol 1992; 148:772–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valent P, Spanblochl E, Sperr WR, Sillaber C, Zsebo KM, Agis H, et al. Induction of differentiation of human mast cells from bone marrow and peripheral blood mononuclear cells by recombinant human stem cell factor/kit-ligand in long-term culture. Blood 1992; 80:2237–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irani AM, Nilsson G, Miettinen U, Craig SS, Ashman LK, Ishizaka T, et al. Recombinant human stem cell factor stimulates differentiation of mast cells from dispersed human fetal liver cells. Blood 1992; 80:3009–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruse G, Metcalfe DD, Olivera A. Functional deregulation of KIT: link to mast cell proliferative diseases and other neoplasms. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2014; 34:219–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witte ON. Steel locus defines new multipotent growth factor. Cell 1990; 63:5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galli SJ. New insights into “the riddle of the mast cells”: microenvironmental regulation of mast cell development and phenotypic heterogeneity. Lab Invest 1990; 62:5–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valent P, Bettelheim P. Cell surface structures on human basophils and mast cells: biochemical and functional characterization. Advances in immunology 1992; 52:333–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oriss TB, Krishnamoorthy N, Ray P, Ray A. Dendritic cell c-kit signaling and adaptive immunity: implications for the upper airways. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 14:7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan Q, Austen KF, Friend DS, Heidtman M, Boyce JA. Human peripheral blood eosinophils express a functional c-kit receptor for stem cell factor that stimulates very late antigen 4 (VLA-4)-mediated cell adhesion to fibronectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1). J Exp Med 1997; 186:313–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fonseca W, Rasky AJ, Ptaschinski C, Morris SH, Best SKK, Phillips M, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) are regulated by stem cell factor during chronic asthmatic disease. Mucosal Immunol 2019; 12:445–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choo E, Dando R. The c-kit Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Marks Sweet or Umami Sensing T1R3 Positive Adult Taste Cells in Mice. Chemosensory Perception 2021; 14:41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morii E, Hirota S, Kim HM, Mikoshiba K, Nishimune Y, Kitamura Y, et al. Spatial expression of genes encoding c-kit receptors and their ligands in mouse cerebellum as revealed by in situ hybridization. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 1992; 65:123–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manova K, Bachvarova RF, Huang EJ, Sanchez S, Pronovost SM, Velazquez E, et al. c-kit receptor and ligand expression in postnatal development of the mouse cerebellum suggests a function for c-kit in inhibitory interneurons. J Neurosci 1992; 12:4663–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huizinga JD, Thuneberg L, Kluppel M, Malysz J, Mikkelsen HB, Bernstein A. W/kit gene required for interstitial cells of Cajal and for intestinal pacemaker activity. Nature 1995; 373:347–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson DM, Williams DE, Tushinski R, Gimpel S, Eisenman J, Cannizzaro LA, et al. Alternate splicing of mRNAs encoding human mast cell growth factor and localization of the gene to chromosome 12q22-q24. Cell Growth Differ 1991; 2:373–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu YR, Wu GM, Mendiaz EA, Syed R, Wypych J, Toso R, et al. The majority of stem cell factor exists as monomer under physiological conditions. Implications for dimerization mediating biological activity. J Biol Chem 1997; 272:6406–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kapur R, Majumdar M, Xiao X, McAndrews-Hill M, Schindler K, Williams DA. Signaling through the interaction of membrane-restricted stem cell factor and c-kit receptor tyrosine kinase: genetic evidence for a differential role in erythropoiesis. Blood 1998; 91:879–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tajima Y, Moore MA, Soares V, Ono M, Kissel H, Besmer P. Consequences of exclusive expression in vivo of Kit-ligand lacking the major proteolytic cleavage site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95:11903–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rasky A, Habiel DM, Morris S, Schaller M, Moore BB, Phan S, et al. Inhibition of the stem cell factor 248 isoform attenuates the development of pulmonary remodeling disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2020; 318:L200–L11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ptaschinski C, Rasky AJ, Fonseca W, Lukacs NW. Stem Cell Factor Neutralization Protects From Severe Anaphylaxis in a Murine Model of Food Allergy. Front Immunol 2021; 12:604192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galli SJ, Tsai M, Marichal T, Tchougounova E, Reber LL, Pejler G. Approaches for analyzing the roles of mast cells and their proteases in vivo. Advances in immunology 2015; 126:45–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galli SJ, Gaudenzio N, Tsai M. Mast Cells in Inflammation and Disease: Recent Progress and Ongoing Concerns. Annu Rev Immunol 2020; 38:49–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feyerabend TB, Weiser A, Tietz A, Stassen M, Harris N, Kopf M, et al. Cre-mediated cell ablation contests mast cell contribution in models of antibody- and T cell-mediated autoimmunity. Immunity 2011; 35:832–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lilla JN, Chen CC, Mukai K, BenBarak MJ, Franco CB, Kalesnikoff J, et al. Reduced mast cell and basophil numbers and function in Cpa3-Cre; Mcl-1fl/fl mice. Blood 2011; 118:6930–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reber LL, Marichal T, Galli SJ. New models for analyzing mast cell functions in vivo. Trends Immunol 2012; 33:613–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reitz M, Brunn ML, Rodewald HR, Feyerabend TB, Roers A, Dudeck A, et al. Mucosal mast cells are indispensable for the timely termination of Strongyloides ratti infection. Mucosal Immunol 2017; 10:481–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsujimura T, Morii E, Nozaki M, Hashimoto K, Moriyama Y, Takebayashi K, et al. Involvement of transcription factor encoded by the mi locus in the expression of c-kit receptor tyrosine kinase in cultured mast cells of mice. Blood 1996; 88:1225–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sonnenblick A, Levy C, Razin E. Interplay between MITF, PIAS3, and STAT3 in mast cells and melanocytes. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24:10584–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee YN, Brandal S, Noel P, Wentzel E, Mendell JT, McDevitt MA, et al. KIT signaling regulates MITF expression through miRNAs in normal and malignant mast cell proliferation. Blood 2011; 117:3629–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Desai A, Sowerwine K, Liu Y, Lawrence MG, Chovanec J, Hsu AP, et al. GATA-2-deficient mast cells limit IgE-mediated immediate hypersensitivity reactions in human subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 144:613–7 e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ainsua-Enrich E, Alvarez-Errico D, Gilfillan AM, Picado C, Sayos J, Rivera J, et al. The adaptor 3BP2 is required for early and late events in FcepsilonRI signaling in human mast cells. J Immunol 2012; 189:2727–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ainsua-Enrich E, Serrano-Candelas E, Alvarez-Errico D, Picado C, Sayos J, Rivera J, et al. The adaptor 3BP2 is required for KIT receptor expression and human mast cell survival. J Immunol 2015; 194:4309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mirmonsef P, Shelburne CP, Fitzhugh Yeatman C 2nd, Chong HJ, Ryan JJ. Inhibition of Kit expression by IL-4 and IL-10 in murine mast cells: role of STAT6 and phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase. J Immunol 1999; 163:2530–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sillaber C, Strobl H, Bevec D, Ashman LK, Butterfield JH, Lechner K, et al. IL-4 regulates c-kit proto-oncogene product expression in human mast and myeloid progenitor cells. J Immunol 1991; 147:4224–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nilsson G, Miettinen U, Ishizaka T, Ashman LK, Irani AM, Schwartz LB. Interleukin-4 inhibits the expression of Kit and tryptase during stem cell factor-dependent development of human mast cells from fetal liver cells. Blood 1994; 84:1519–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamazaki S, Nakano N, Honjo A, Hara M, Maeda K, Nishiyama C, et al. The Transcription Factor Ehf Is Involved in TGF-beta-Induced Suppression of FcepsilonRI and c-Kit Expression and FcepsilonRI-Mediated Activation in Mast Cells. J Immunol 2015; 195:3427–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Givi ME, Blokhuis BR, Da Silva CA, Adcock I, Garssen J, Folkerts G, et al. Cigarette smoke suppresses the surface expression of c-kit and FcepsilonRI on mast cells. Mediators Inflamm 2013; 2013:813091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Da Silva CA, Reber L, Frossard N. Stem cell factor expression, mast cells and inflammation in asthma. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2006; 20:21–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Draber P, Halova I, Polakovicova I, Kawakami T. Signal transduction and chemotaxis in mast cells. Eur J Pharmacol 2016; 778:11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iwaki S, Spicka J, Tkaczyk C, Jensen BM, Furumoto Y, Charles N, et al. Kit- and Fc epsilonRI-induced differential phosphorylation of the transmembrane adaptor molecule NTAL/LAB/LAT2 allows flexibility in its scaffolding function in mast cells. Cell Signal 2008; 20:195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim DK, Cho YE, Song BJ, Kawamoto T, Metcalfe DD, Olivera A. Aldh2 Attenuates Stem Cell Factor/Kit-Dependent Signaling and Activation in Mast Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharma N, Kumar V, Everingham S, Mali RS, Kapur R, Zeng LF, et al. SH2 domain-containing phosphatase 2 is a critical regulator of connective tissue mast cell survival and homeostasis in mice. Mol Cell Biol 2012; 32:2653–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharma N, Everingham S, Ramdas B, Kapur R, Craig AW. SHP2 phosphatase promotes mast cell chemotaxis toward stem cell factor via enhancing activation of the Lyn/Vav/Rac signaling axis. J Immunol 2014; 192:4859–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalesnikoff J, Rios EJ, Chen CC, Nakae S, Zabel BA, Butcher EC, et al. RabGEF1 regulates stem cell factor/c-Kit-mediated signaling events and biological responses in mast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:2659–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arock M, Hoermann G, Sotlar K, Hermine O, Sperr WR, Hartmann K, et al. Clinical Impact and Proposed Application of Molecular markers, genetic variants and cytogenetic analysis in mast cell neoplasms: status 2022. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022:In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arock M, Sotlar K, Akin C, Broesby-Olsen S, Hoermann G, Escribano L, et al. KIT mutation analysis in mast cell neoplasms: recommendations of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis. Leukemia 2015; 29:1223–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valent P, Akin C, Bonadonna P, Hartmann K, Brockow K, Niedoszytko M, et al. Proposed Diagnostic Algorithm for Patients with Suspected Mast Cell Activation Syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7:1125–33 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mitsui H, Furitsu T, Dvorak AM, Irani AM, Schwartz LB, Inagaki N, et al. Development of human mast cells from umbilical cord blood cells by recombinant human and murine c-kit ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993; 90:735–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Durand B, Migliaccio G, Yee NS, Eddleman K, Huima-Byron T, Migliaccio AR, et al. Long-term generation of human mast cells in serum-free cultures of CD34+ cord blood cells stimulated with stem cell factor and interleukin-3. Blood 1994; 84:3667–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Radinger M, Jensen BM, Kuehn HS, Kirshenbaum A, Gilfillan AM. Generation, isolation, and maintenance of human mast cells and mast cell lines derived from peripheral blood or cord blood. Curr Protoc Immunol 2010; Chapter 7:Unit 7 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shimizu Y, Sakai K, Miura T, Narita T, Tsukagoshi H, Satoh Y, et al. Characterization of ‘adult-type’ mast cells derived from human bone marrow CD34(+) cells cultured in the presence of stem cell factor and interleukin-6. Interleukin-4 is not required for constitutive expression of CD54, Fc epsilon RI alpha and chymase, and CD13 expression is reduced during differentiation. Clin Exp Allergy 2002; 32:872–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kirshenbaum AS, Metcalfe DD. Growth of human mast cells from bone marrow and peripheral blood-derived CD34+ pluripotent progenitor cells. Methods Mol Biol 2006; 315:105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang XS, Sam SW, Yip KH, Lau HY. Functional characterization of human mast cells cultured from adult peripheral blood. Int Immunopharmacol 2006; 6:839–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kovarova M, Latour AM, Chason KD, Tilley SL, Koller BH. Human embryonic stem cells: a source of mast cells for the study of allergic and inflammatory diseases. Blood 2010; 115:3695–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dahlin JS, Ekoff M, Grootens J, Lof L, Amini RM, Hagberg H, et al. KIT signaling is dispensable for human mast cell progenitor development. Blood 2017; 130:1785–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamada N, Matsushima H, Tagaya Y, Shimada S, Katz SI. Generation of a large number of connective tissue type mast cells by culture of murine fetal skin cells. J Invest Dermatol 2003; 121:1425–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maguire ARR, Crozier RWE, Hunter KD, Claypool SM, Fajardo VA, LeBlanc PJ, et al. Tafazzin Modulates Allergen-Induced Mast Cell Inflammatory Mediator Secretion. Immunohorizons 2021; 5:182–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang D, Zheng M, Qiu Y, Guo C, Ji J, Lei L, et al. Tespa1 negatively regulates FcepsilonRI-mediated signaling and the mast cell-mediated allergic response. J Exp Med 2014; 211:2635–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Malbec O, Roget K, Schiffer C, Iannascoli B, Dumas AR, Arock M, et al. Peritoneal cell-derived mast cells: an in vitro model of mature serosal-type mouse mast cells. J Immunol 2007; 178:6465–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsai M, Tam SY, Wedemeyer J, Galli SJ. Mast cells derived from embryonic stem cells: a model system for studying the effects of genetic manipulations on mast cell development, phenotype, and function in vitro and in vivo. Int J Hematol 2002; 75:345–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Valent P, Akin C, Hartmann K, Nilsson G, Reiter A, Hermine O, et al. Mast cells as a unique hematopoietic lineage and cell system: From Paul Ehrlich’s visions to precision medicine concepts. Theranostics 2020; 10:10743–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rennick D, Hunte B, Holland G, Thompson-Snipes L. Cofactors are essential for stem cell factor-dependent growth and maturation of mast cell progenitors: comparative effects of interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-4, IL-10, and fibroblasts. Blood 1995; 85:57–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tsai M, Takeishi T, Thompson H, Langley KE, Zsebo KM, Metcalfe DD, et al. Induction of mast cell proliferation, maturation, and heparin synthesis by the rat c-kit ligand, stem cell factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991; 88:6382–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gurish MF, Ghildyal N, McNeil HP, Austen KF, Gillis S, Stevens RL. Differential expression of secretory granule proteases in mouse mast cells exposed to interleukin 3 and c-kit ligand. J Exp Med 1992; 175:1003–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang Y, Matsushita K, Jackson J, Numata T, Zhang Y, Zhou G, et al. Transcriptome programming of IL-3-dependent bone marrow-derived cultured mast cells by stem cell factor (SCF). Allergy 2021; 76:2288–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Derakhshan T, Samuchiwal SK, Hallen N, Bankova LG, Boyce JA, Barrett NA, et al. Lineage-specific regulation of inducible and constitutive mast cells in allergic airway inflammation. J Exp Med 2021; 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Karimi K, Redegeld FA, Blom R, Nijkamp FP. Stem cell factor and interleukin-4 increase responsiveness of mast cells to substance P. Exp Hematol 2000; 28:626–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.van der Kleij HP, Ma D, Redegeld FA, Kraneveld AD, Nijkamp FP, Bienenstock J. Functional expression of neurokinin 1 receptors on mast cells induced by IL-4 and stem cell factor. J Immunol 2003; 171:2074–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tsai M, Shih LS, Newlands GF, Takeishi T, Langley KE, Zsebo KM, et al. The rat c-kit ligand, stem cell factor, induces the development of connective tissue-type and mucosal mast cells in vivo. Analysis by anatomical distribution, histochemistry, and protease phenotype. J Exp Med 1991; 174:125–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mekori YA, Oh CK, Metcalfe DD. IL-3-dependent murine mast cells undergo apoptosis on removal of IL-3. Prevention of apoptosis by c-kit ligand. J Immunol 1993; 151:3775–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Iemura A, Tsai M, Ando A, Wershil BK, Galli SJ. The c-kit ligand, stem cell factor, promotes mast cell survival by suppressing apoptosis. Am J Pathol 1994; 144:321–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Meininger CJ, Yano H, Rottapel R, Bernstein A, Zsebo KM, Zetter BR. The c-kit receptor ligand functions as a mast cell chemoattractant. Blood 1992; 79:958–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nilsson G, Butterfield JH, Nilsson K, Siegbahn A. Stem cell factor is a chemotactic factor for human mast cells. J Immunol 1994; 153:3717–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sundstrom M, Alfredsson J, Olsson N, Nilsson G. Stem cell factor-induced migration of mast cells requires p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. Exp Cell Res 2001; 267:144–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dastych J, Metcalfe DD. Stem cell factor induces mast cell adhesion to fibronectin. J Immunol 1994; 152:213–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maurer M, Galli SJ. Lack of significant skin inflammation during elimination by apoptosis of large numbers of mouse cutaneous mast cells after cessation of treatment with stem cell factor. Lab Invest 2004; 84:1593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Galli SJ, Iemura A, Garlick DS, Gamba-Vitalo C, Zsebo KM, Andrews RG. Reversible expansion of primate mast cell populations in vivo by stem cell factor. J Clin Invest 1993; 91:148–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Costa JJ, Demetri GD, Harrist TJ, Dvorak AM, Hayes DF, Merica EA, et al. Recombinant human stem cell factor (kit ligand) promotes human mast cell and melanocyte hyperplasia and functional activation in vivo. J Exp Med 1996; 183:2681–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dvorak AM, Costa JJ, Monahan-Earley RA, Fox P, Galli SJ. Ultrastructural analysis of human skin biopsy specimens from patients receiving recombinant human stem cell factor: subcutaneous injection of rhSCF induces dermal mast cell degranulation and granulocyte recruitment at the injection site. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998; 101:793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Columbo M, Horowitz EM, Botana LM, MacGlashan DW Jr., Bochner BS, Gillis S, et al. The human recombinant c-kit receptor ligand, rhSCF, induces mediator release from human cutaneous mast cells and enhances IgE-dependent mediator release from both skin mast cells and peripheral blood basophils. J Immunol 1992; 149:599–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Taylor AM, Galli SJ, Coleman JW. Stem-cell factor, the kit ligand, induces direct degranulation of rat peritoneal mast cells in vitro and in vivo: dependence of the in vitro effect on period of culture and comparisons of stem-cell factor with other mast cell-activating agents. Immunology 1995; 86:427–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gagari E, Tsai M, Lantz CS, Fox LG, Galli SJ. Differential release of mast cell interleukin-6 via c-kit. Blood 1997; 89:2654–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Oliveira SH, Hogaboam CM, Berlin A, Lukacs NW. SCF-induced airway hyperreactivity is dependent on leukotriene production. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2001; 280:L1242–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.MacNeil AJ, Junkins RD, Wu Z, Lin TJ. Stem cell factor induces AP-1-dependent mast cell IL-6 production via MAPK kinase 3 activity. J Leukoc Biol 2014; 95:903–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wershil BK, Tsai M, Geissler EN, Zsebo KM, Galli SJ. The rat c-kit ligand, stem cell factor, induces c-kit receptor-dependent mouse mast cell activation in vivo. Evidence that signaling through the c-kit receptor can induce expression of cellular function. J Exp Med 1992; 175:245–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ho CCM, Chhabra A, Starkl P, Schnorr PJ, Wilmes S, Moraga I, et al. Decoupling the Functional Pleiotropy of Stem Cell Factor by Tuning c-Kit Signaling. Cell 2017; 168:1041–52 e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bischoff SC, Dahinden CA. c-kit ligand: a unique potentiator of mediator release by human lung mast cells. J Exp Med 1992; 175:237–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hill PB, MacDonald AJ, Thornton EM, Newlands GF, Galli SJ, Miller HR. Stem cell factor enhances immunoglobulin E-dependent mediator release from cultured rat bone marrow-derived mast cells: activation of previously unresponsive cells demonstrated by a novel ELISPOT assay. Immunology 1996; 87:326–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hundley TR, Gilfillan AM, Tkaczyk C, Andrade MV, Metcalfe DD, Beaven MA. Kit and FcepsilonRI mediate unique and convergent signals for release of inflammatory mediators from human mast cells. Blood 2004; 104:2410–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tkaczyk C, Horejsi V, Iwaki S, Draber P, Samelson LE, Satterthwaite AB, et al. NTAL phosphorylation is a pivotal link between the signaling cascades leading to human mast cell degranulation following Kit activation and Fc epsilon RI aggregation. Blood 2004; 104:207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Iwaki S, Tkaczyk C, Satterthwaite AB, Halcomb K, Beaven MA, Metcalfe DD, et al. Btk plays a crucial role in the amplification of Fc epsilonRI-mediated mast cell activation by kit. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:40261–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Drube S, Heink S, Walter S, Lohn T, Grusser M, Gerbaulet A, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase c-Kit controls IL-33 receptor signaling in mast cells. Blood 2010; 115:3899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wei JJ, Song CW, Sun LC, Yuan Y, Li D, Yan B, et al. SCF and TLR4 ligand cooperate to augment the tumor-promoting potential of mast cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012; 61:303–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ando A, Martin TR, Galli SJ. Effects of chronic treatment with the c-kit ligand, stem cell factor, on immunoglobulin E-dependent anaphylaxis in mice. Genetically mast cell-deficient Sl/Sld mice acquire anaphylactic responsiveness, but the congenic normal mice do not exhibit augmented responses. J Clin Invest 1993; 92:1639–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ito T, Smrz D, Jung MY, Bandara G, Desai A, Smrzova S, et al. Stem cell factor programs the mast cell activation phenotype. J Immunol 2012; 188:5428–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Valent P, Akin C, Hartmann K, Reiter A, Gotlib J, Sotlar K, et al. Drug-induced mast cell eradication: a novel approach to treat mast cell activation disorders? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022:in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Akin C, et al. Administration of KIT-Targeting Therapies in Indolent Mast Cell Disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022:in press. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Arock M, et al. Molecular Target Expression Profiles and Genetic Variants in Mast Cell Neoplasms. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022:In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hartmann K, et al. Therapy of Skin Lesions in Mastocytosis: Can we Eradicate by Novel KIT Inhibitors? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022:in press. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Reiter A, et al. KIT-Targeting Therapy for the Treatment of Advanced Mast Cell Neoplasms. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022:in press. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Valent P, Akin C, Sperr WR, Horny HP, Arock M, Metcalfe DD, et al. New insights into the pathogenesis of mastocytosis: emerging concepts in diagnosis and therapy. Ann Rev Pathol: Mechanisms of Disease 2022:submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kolkhir P, Elieh-Ali-Komi D, Metz M, Siebenhaar F, Maurer M. Understanding human mast cells: lesson from therapies for allergic and non-allergic diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Paivandy A, Pejler G. Novel Strategies to Target Mast Cells in Disease. J Innate Immun 2021; 13:131–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.London CA, Gardner HL, Rippy S, Post G, La Perle K, Crew L, et al. KTN0158, a Humanized Anti-KIT Monoclonal Antibody, Demonstrates Biologic Activity against both Normal and Malignant Canine Mast Cells. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23:2565–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Brandt EB, Strait RT, Hershko D, Wang Q, Muntel EE, Scribner TA, et al. Mast cells are required for experimental oral allergen-induced diarrhea. J Clin Invest 2003; 112:1666–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Terhorst-Molawi D, Hawro T, Grekowitz E, Kiefer L, Metz M, Alvarado D, et al. The Anti-KIT Antibody, CDX-0159, Reduces Mast Cell Numbers and Circulating Tryptase and Improves Disease Control in Patients with Chronic Inducible Urticaria (Cindu). J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022; 149:AB178. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Donaldson LE, Schmitt E, Huntley JF, Newlands GF, Grencis RK. A critical role for stem cell factor and c-kit in host protective immunity to an intestinal helminth. Int Immunol 1996; 8:559–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Newlands GF, Miller HR, MacKellar A, Galli SJ. Stem cell factor contributes to intestinal mucosal mast cell hyperplasia in rats infected with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis or Trichinella spiralis, but anti-stem cell factor treatment decreases parasite egg production during N brasiliensis infection. Blood 1995; 86:1968–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bachelet I, Munitz A, Berent-Maoz B, Mankuta D, Levi-Schaffer F. Suppression of normal and malignant kit signaling by a bispecific antibody linking kit with CD300a. J Immunol 2008; 180:6064–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yu M, Tsai M, Tam SY, Jones C, Zehnder J, Galli SJ. Mast cells can promote the development of multiple features of chronic asthma in mice. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:1633–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Yu M, Eckart MR, Morgan AA, Mukai K, Butte AJ, Tsai M, et al. Identification of an IFN-γ/mast cell axis in a mouse model of chronic asthma. J Clin Invest 2011; 121:3133–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kanagaratham C, El Ansari YS, Lewis OL, Oettgen HC. IgE and IgG Antibodies as Regulators of Mast Cell and Basophil Functions in Food Allergy. Front Immunol 2020; 11:603050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Maurer M, Khan DA, Elieh Ali Komi D, Kaplan AP. Biologics for the Use in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: When and Which. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9:1067–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Alvarado D, Maurer M, Gedrich R, Seibel SB, Murphy MB, Crew L, et al. Anti-KIT monoclonal antibody CDX-0159 induces profound and durable mast cell suppression in a healthy volunteer study. Allergy 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.L’Italien L, Orozco O, Abrams T, Cantagallo L, Connor A, Desai J, et al. Mechanistic Insights of an Immunological Adverse Event Induced by an Anti-KIT Antibody Drug Conjugate and Mitigation Strategies. Clin Cancer Res 2018; 24:3465–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cahill KN, Katz HR, Cui J, Lai J, Kazani S, Crosby-Thompson A, et al. KIT Inhibition by Imatinib in Patients with Severe Refractory Asthma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:1911–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Galli SJ. Mast Cells and KIT as Potential Therapeutic Targets in Severe Asthma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:1983–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]