Abstract

Type 1 fimbriae are surface organelles of Escherichia coli. By engineering a structural component of the fimbriae, FimH, to display a random peptide library, we were able to isolate metal-chelating bacteria. A library consisting of 4 × 107 independent clones was screened for binding to ZnO. Sequences responsible for ZnO adherence were identified, and distinct binding motifs were characterized. The sequences selected exhibited various degrees of affinity and specificity towards ZnO. Competitive binding experiments revealed that the sequences recognized only the oxide form of Zn. Interestingly, one of the inserts exhibited significant homology to a specific sequence in a putative zinc-containing helicase, which suggests that searches such as this one may aid in identifying binding motifs in nature. The zinc-binding bacteria might have a use in detoxification of metal-polluted water.

In recent years a variety of expression systems for display of heterologous proteins on the surfaces of bacteria, bacteriophages, and yeasts have been developed (3, 11, 14). Many different types of surface proteins of gram-negative bacteria have been used to display foreign peptides; these surface proteins include LamB (4, 5, 22), flagellin (26, 29), P fimbriae (35, 38), OmpA (9), PhoE (1), peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein (7, 10), OprI (6), Lpp (8), and type 1 fimbriae (13, 20, 30, 36). Enzymes, antigenic determinants, single-chain antibodies, metal-chelating peptides, and random peptide libraries have all been displayed on the surfaces of gram-negative bacteria. Systems in which random peptide libraries are expressed in connection with a surface protein have allowed screening of a vast number of peptides for binding to a certain target (11, 33). This technique allows construction of huge populations of diverse macromolecules and has been used in a number of different research fields.

We are particularly interested in the display of heterologous peptides in type 1 fimbriae. A typical type 1 fimbriated bacterial cell has 200 to 500 peritrichous fimbriae on its surface. A single type 1 fimbria is a rod-shaped structure that is 7 nm wide and approximately 1 μm long and consists of four different components that are added to the base of the growing organelle (25). The bulk of the structure is made up of about 1,000 copies of the major subunit protein, FimA, polymerized into a right-handed helical structure, but small quantities of the minor components, FimF, FimG, and FimH, are also present (18, 24). It has been shown that the receptor-recognizing element of type 1 fimbriae is the 30-kDa FimH protein (23). The FimH protein is located at the tip and also is interspersed along the fimbrial shaft (16, 23). The FimF and FimG components are probably required for integration of the FimH adhesin into the fimbriae (16, 18).

The components of the fimbrial organelle are encoded by the chromosomal fim gene cluster (21). In addition to the structural components, this 9.5-kb DNA segment also encodes the fimbrial biosynthesis machinery, as well as regulatory elements (Fig. 1). The fimbrial organelle components, FimA, FimF, FimG, and FimH, are produced as precursors having N-terminal signal sequences. The N-terminal signal sequences are subsequently removed during export across the inner membrane. Thus, the FimH protein is produced as a 300-amino-acid precursor that is processed into a mature form containing 279 amino acids (12, 18). Further export from the periplasm across the outer membrane is dependent on a fimbria-specific export and assembly system made up of the FimC and FimD proteins (15, 17, 19).

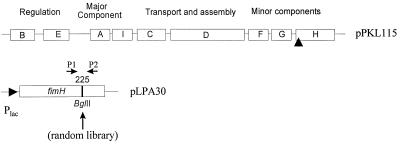

FIG. 1.

Overview of the plasmids used in the FimH display system. Only relevant nonvector regions are shown. Plasmid pPKL115 contains the entire fim gene cluster with a translational stop linker inserted in the fimH gene (indicated by a triangle). The FimH expression vector pLPA30 is shown along with the BglII insertion site at amino acid position 225 and the two primers (P1 and P2) used to monitor the size and distribution of the random library.

In connection with the development of vaccine systems, heterologous sequences that represent immune-relevant sectors of proteins from foreign microorganisms have been authentically displayed on bacterial surfaces as fimbrial fusion proteins (30, 36). Previous work in our lab established that position 225 in FimH is a permissive site for insertion and display of heterologous sequences (30). This information was used to develop a system for display of random peptide libraries in Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae.

In an attempt to create a biological capture system for remediation of heavy metal contamination, we screened a peptide library for binding to ZnO. Here we describe the construction of ZnO-sequestering cells and the peptide sequences responsible for binding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

In this study we used E. coli K-12 strain S1918 (F′ lacIq ΔmalB101 endA hsdR17 supE44 thiI relA1 gyr96 ΔfimB-H::kan) (4). Cells were grown in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. Our FimH display system consisted of two plasmids, the FimH expression vector pLPA30 and auxiliary plasmid pPKL115. Plasmid pLPA30 is a pUC18 derivative containing the fimH gene downstream of the lac promoter. A BglII linker, located in a position corresponding to amino acid 225 (30), was used for integration of the random library. Plasmid pPKL115 is a pACYC184 derivative containing the whole fim gene cluster with a translational stop linker inserted in the fimH gene (30).

DNA techniques.

Plasmid DNA was isolated by using a QIAprep Spin plasmid kit (QIAGEN). Restriction endonucleases were used as recommended by the manufacturer (Biolabs or Pharmacia). PCR to monitor the size and distribution of the random library were performed as previously described (36). The oligonucleotide primers used in these reactions were P1 (5′-CCTGCACAGGGCGTCGGCGTAC) and P2 (5′-GGAATAATCGTACCGTTGCG). The nucleotide sequences of inserts that conferred the ability to bind to metal oxides were determined by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (32).

Construction of the random library.

The random library was constructed essentially as described by Brown (4). Briefly, a template oligonucleotide containing the sequence 5′-GGACGCAGATCT(VNN)9AGATCTAGCACCAGT-3′ was chemically synthesized (N indicates an equimolar mixture of all four nucleotides, and V indicates an equimolar mixture of A, C, and G). A primer oligonucleotide, 5′-ACTGGTGCTAGATCT-3′, was hybridized to the template oligonucleotide and extended with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. The double-stranded oligonucleotide was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and digested with BglII to release an internal 33-bp fragment. This fragment was purified by electrophoresis through a 12% polyacrylamide gel in Tris-borate-EDTA and was eluted into a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 2 mM EDTA, and 0.15 M NaCl. The eluate was filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size Qiagen filter, concentrated by ethanol precipitation, and redissolved in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 M NaCl. The redissolved 33-bp BglII fragment was ligated at various ratios to BglII-digested pLPA30. The ligation products were precipitated with ethanol and electroporated into S1918(pPKL115).

The diversity of the library was calculated to be 4 × 107 individual clones based on extrapolation from the numbers of transformants obtained in small-scale plating experiments. The transformation mixture was made up to 10 ml and grown for approximately seven generations (4 × 109 cells). Aliquots (1 ml) were frozen at −80°C in 25% (vol/vol) glycerol. Each 1-ml aliquot contained approximately 4 × 108 cells, which represented 10 times the library diversity. Random screening of clones by PCR revealed a predominance of one to three 33-bp oligonucleotide inserts; sequencing of the inserts in randomly selected clones revealed that the G+C contents ranged from 30 to 70%.

Enrichment procedure.

The following enrichment procedure was used to identify zinc oxide (ZnO)-binding clones in the random library. Mid-exponential-phase cultures were diluted with M63 salts (28) containing 20 mM methyl α-d-mannopyranoside and 75% (vol/vol) Percoll (Pharmacia). The methyl α-d-mannopyranoside was added to block the natural receptor-binding domain of the FimH adhesin. The Percoll permitted formation of a density gradient upon centrifugation, which resulted in pelleting of the metal oxides and specific separation of any adhering bacteria from nonadherent bacteria. Under these conditions, bacteria expressing wild-type FimH proteins as components of type 1 fimbriae did not sediment with ZnO. ZnO and bacteria expressing the random peptide library in FimH were mixed and allowed to adhere to each other at room temperature with gentle agitation. Centrifugation was then performed, and the ZnO and any adhering bacteria were recovered and inoculated into Luria-Bertani medium containing the appropriate antibiotics. After overnight incubation, exponentially growing cultures were established, and the enrichment procedure was repeated. Following each cycle of enrichment, aliquots of the populations were stored at −80°C. Plasmid DNA was prepared from each aliquot and used in PCR to monitor the size distribution of the inserts in the population.

Binding experiments.

Zinc oxide and cadmium oxide were purchased from Sigma. Particles of the appropriate size for microscopy were prepared by differential centrifugation. For binding experiments, the metal oxides were suspended in M63 salts at a concentration of 3 nM before bacteria were added. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 15 min with gentle agitation and examined microscopically. Neither ZnO nor CdO had a toxic effect under these conditions. The abilities of individual clones to bind to metal oxides were quantified by counting the cells attached to 20 metal particles in four randomly chosen frames containing five particles. Zn2+-nitrilotriacetic acid resin was prepared by using the specifications of the manufacturers (Qiagen). Binding of cells to the resin was monitored by phase-contrast microscopy.

Agglutination of yeast cells.

The capacity of bacteria to express a d-mannose-binding phenotype was assayed by determining their ability to agglutinate yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) cells on glass slides. Aliquots of washed bacterial suspensions (optical density at 550 nm, 1.0) and 10% yeast cells were mixed, and the time until agglutination occurred was measured.

Insertion of putative helicase motif in fimH.

Two oligonucleotides, oligonucleotide O1 (5′-GATCTAATAGCCGGAGCTCGGCACGCAGCACCGCGCGCAGCGCTCCACGCAGCACCCAACGCAGCA-3′) and oligonucleotide O2 (5′-GATCTGCTGCGTTGGGTGCTGCGTGGAGCGCTGCGCGCGGTGC TGCGTGCACTGCTCCGGCTATTA-3′) encoding the putative helicase motif of Schizosaccharomyces pombe, were designed so that they contained an internal SacI site and were flanked by BglII overhangs. These oligonucleotides were annealed, phosphorylated, and ligated into pLPA30 digested with BglII. The resultant plasmid (pKKJ95) was checked by SacI digestion and sequencing. Plasmid pKKJ95 (containing the putative helicase motif on fimH) was transformed into S1918(pPKL115).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The primary DNA sequences encoding the binding peptides isolated from the random peptide library have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF167286 to AF167294.

RESULTS

Construction of random peptide library in FimH.

We developed a binary plasmid system for displaying random peptides in the type 1 fimbrial adhesin, FimH. Chimeric FimH proteins displaying a random peptide library were engineered by using the FimH expression plasmid pLPA30. This vector contains the fimH gene with an in-frame BglII linker inserted at a position corresponding to amino acid residue 225 of the mature protein and under transcriptional control of the inducible lac promoter (30).

The random library was constructed by inserting various numbers of synthetically synthesized 33-bp oligonucleotides into the BglII linker site. The presence of BglII overhangs in the linker resulted in an arginine-serine flanking sequence for each insertion. In addition, the presence of a VNN code in the random sequences ensured that functional stop codons were not present in an amber suppressing host. This genetic design allowed insertion of various numbers of double-stranded oligonucleotides into fimH, which increased the complexity of the library. In order to express the chimeric FimH proteins as functional constituents of type 1 fimbriae, we also used an auxiliary plasmid (pPKL115) which encodes the rest of the fim gene cluster (Fig. 1).

Selection of ZnO-binding clones from the random library.

Serial selection and enrichment of the random library was performed by using ZnO. To isolate cells adhering to ZnO particles, we used a 75% (vol/vol) Percoll solution which formed a density gradient upon centrifugation. Under these conditions only cells adhering to ZnO were able to sediment when they were centrifuged.

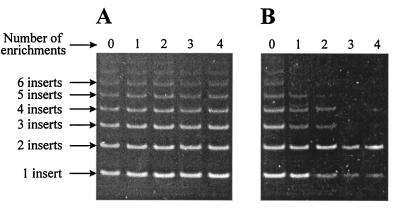

The genetic design of our random library allowed us to monitor the bacterial population by screening for changes in the number of inserts in fimH by PCR. Samples obtained after each enrichment cycle were analyzed by PCR amplification of the insert region by using primers complementary to the vector sequence flanking the insertion site (Fig. 1).

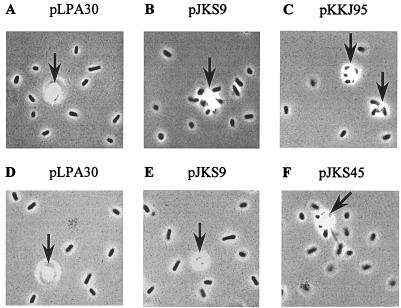

In a control experiment, in which neither Percoll nor metal oxide was added, no perturbation in the distribution of insert sizes was observed during the enrichment procedure (Fig. 2A). However, a PCR analysis of the population after four cycles of enrichment with ZnO revealed that representation of clones having inserts consisting of one and two oligonucleotides increased (Fig. 2B). Cells obtained from the fourth enrichment cycle were spread onto agar plates, and cultures were established from 40 single colonies. The abilities of cells expressing the enriched peptides to adhere to ZnO were examined by phase-contrast microscopy. The behavior of one clone and the behavior of a control strain expressing wild-type FimH are shown in Figure 3A and B. Approximately 63% (25 of 40) of the clones selected exhibited a ZnO-binding phenotype and were examined further.

FIG. 2.

(A) PCR analysis of the insert population obtained in a mock enrichment experiment performed with M63 salts alone, showing the stability of the insert population in the absence of selection for binding to a specified target. The sizes and distributions of the insert population prior to enrichment (lane 0) and after the four enrichment cycles (lanes 1 to 4) are shown. The numbers of insert sequences are indicated on the left. (B) Monitoring of the insert population by PCR performed with primers P1 and P2 during enrichment for sequences that bind to ZnO.

FIG. 3.

Phase-contrast microscopy showing adherence of S1918 cells containing plasmids expressing chimeric fimH genes enriched from the random peptide library for binding to ZnO (A to C) or CdO (D to F). (A) Plasmid pLPA30 (wild-type fimH). (B) Plasmid pJKS9 (random library clone isolated after selection for adherence to ZnO). (C) Plasmid pKKJ95 (putative helicase domain in fimH). (D) Plasmid pLPA30 (wild-type fimH). (E) Plasmid pJKS9 (random library clone isolated after selection for adherence to ZnO). (F) Plasmid pKKJ45 (random library clone isolated after selection for adherence to ZnO). Metal oxide crystals are indicated by arrows.

The fimH-containing plasmids were purified and individually retransformed into S1918(pPKL115) cells. The reconstructed clones exhibited the same capacity to adhere to ZnO as the original isolates, indicating that the ZnO-binding phenotype was indeed plasmid encoded. In addition, the ZnO-binding capacities of these clones were not affected when Percoll and methyl-α-d-mannopyranoside were removed from the M63 salts medium. The agglutination titers of the cells were similar to the agglutination titer of a control strain expressing wild-type FimH, indicating that the inserts did not influence the natural binding domain of FimH or significantly alter the number of fimbriae on the surface of the cells.

Analysis of isolated sequences.

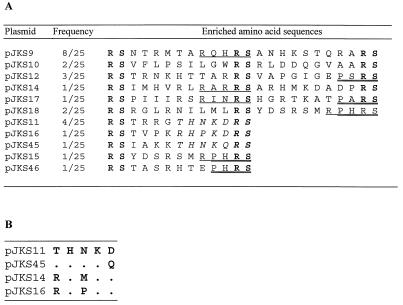

The insert regions in fimH of 25 individual ZnO-binding clones were sequenced, and we identified 11 different sequences which could confer on E. coli cells the ability to bind to ZnO (Fig. 4A). The insert sequences of pJKS9, pJKS11, pJKS12, and pJKS10 were represented eight, four, three, and two times, respectively, in these preparations. Most of the clones had two inserts, which is consistent with the PCR results obtained from monitoring the insert distribution. Interestingly, one of the two inserts in pJKS18 was also found in pJKS15, which provided strong evidence that this sequence plays a role in ZnO binding.

FIG. 4.

(A) Isolated sequences conferring the ability to adhere to ZnO. The three different binding motifs from the enriched amino acid sequences are underlined (RX2RS), double underlined (PXRS), and italicized (R/T-HXK-D/Q). The boldface letters represent amino acids encoded by the BglII linkers. (B) Alignment of sequences comprising the motif R/T-HXK-D/Q. Dots indicate identical amino acids.

A number of structural similarities were discerned when we examined the amino acid sequences enriched for binding to ZnO. Enrichment for the amino acids histidine, arginine, aspartate, and methionine was observed. The sequences of plasmids pJKS11 and pJKS45 were very similar and contained a common THNK amino acid segment. Based on additional similarity to plasmids pJKS14 and pJKS16, we were able to identify a common motif, R/T-HXK-D/Q, which may be involved in ZnO binding (Fig. 4B). In addition, two other motifs, R-X2-RS and PXRS, occurred five and four times, respectively.

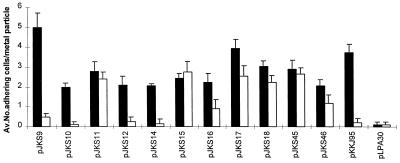

Quantification of binding with enriched sequences.

The presence of the insert sequence from plasmid pJKS9 in 8 of the 25 clones suggested that the sequences which we selected may exhibit different ZnO-binding avidities. In order to investigate this possibility, bacteria associated with ZnO particles were counted directly. Our enumeration of bound cells revealed differences in avidity among the ZnO-binding clones examined (Fig. 5). The strongest binding capacity was observed with cells harboring plasmid pJKS9, which indicated that the FimH display system was able to enrich for sequences with different degrees of affinity for ZnO.

FIG. 5.

Quantification of ZnO binding (solid bars) and CdO binding (open bars) by isolated clones from the random library. The average number of adhering cells per metal oxide particle is indicated for each clone. Plasmid pLPA30 expressing wild-type FimH was the negative control. The values are means ± standard errors of the means (n = 20) based on a 99% level of confidence.

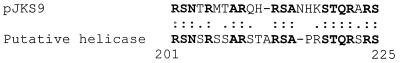

Identification of a zinc-binding motif in a putative helicase.

The isolated sequences in the random library were compared to sequences in the SWISS-PROT database. Interestingly, a database search revealed a striking similarity (level of identity, 63%) between the insert of pJKS9 and a 24-amino-acid portion of a putative helicase from S. pombe (Fig. 6). The level of sequence similarity was 50% if the arginine-serine pairs encoding the BglII sites was not taken into consideration. Since helicases are generally known to be zinc-containing enzymes involved in separation and unwinding of DNA double helixes (34), we hypothesized that this helicase sequence might be involved in zinc binding.

FIG. 6.

Sequence similarity between pJKS9 and the putative helicase domain from S. pombe.

To examine this possibility, two oligonucleotides encoding the identified motif in the putative helicase were annealed and ligated into pLPA30. The resultant plasmid (pKKJ95) was then transformed into S1918(pPKL115). Cells expressing the sequence motif in FimH were observed to bind to ZnO (Fig. 3C).

The binding strength of the putative helicase motif was quantified by counting ZnO-associated bacteria (Fig. 5). Cells harboring pKKJ95 exhibited a binding strength similar to that of the ZnO-binding clone enriched from the random peptide library (pJKS9). These results suggest that metal-binding sequences enriched with the FimH display system may be used to elucidate similar motifs in naturally occurring proteins.

Characterization of the binding specificities of selected sequences.

In order to determine the binding specificities of the sequences enriched for binding to ZnO, we examined their abilities to adhere to CdO. Zinc and cadmium are metals that are closely related as determined by various chemical criteria, as expected on the basis of their close proximity in the periodic table of the elements. Interestingly, we found that whereas some of our clones did not exhibit affinity for CdO, about 50% of the clones did indeed bind to this metal (Fig. 3 and 5). Neither of the two closely related insert sequences in plasmids pJKS9 and pKKJ95 conferred an ability to adhere to CdO. Thus, our system could enrich for clones with different binding affinities (i.e., one subset of clones that could adhere only to ZnO and a second subset of clones that could bind to both ZnO and CdO). We also examined the affinities of the clones for different forms of zinc. To do this, we performed two sets of experiments. In the first set, different amounts of ZnCl2 (a soluble form of zinc) were preincubated with the clones before we tested for binding to ZnO, and this treatment had no effect on the ability of the clones to coordinate ZnO. However, it should be noted that at the highest concentration of ZnCl2 used the cells lysed, which prevented us from conducting inhibition experiments with concentrations higher than 2 mM. In the second set of experiments we monitored the abilities of our clones to bind to nitrilotriacetic acid-chelated Zn2+ resin. Consistent with the results of the previous experiments, no affinity for Zn2+ was observed, which indicated that the binding was highly specific for the oxide form of zinc.

DISCUSSION

Accumulation of heavy metals in the environment due to human activities in the biosphere has been a growing threat to soil, groundwater, and public health over the last few decades. Zinc is an important trace metal in many biological processes (37); however, at higher concentrations it is a biological hazard. The spread and accumulation of zinc in the environment are due to the many uses of this metal; it is used in alloys, electroplating, electronics, automotive parts, fungicides, roofing, cable wrapping, and nutrition and health care products. Previously, it has been suggested that the ability of bacteria to sequester and immobilize heavy metals could be used to develop a biological method for remediation of heavy-metal-polluted wastewater (22, 27, 31).

We developed a system for displaying a random peptide library in connection with the FimH adhesin of E. coli type 1 fimbriae. A serial enrichment process was used, and peptide sequences conferring the ability to coordinate ZnO were selected from the random library and characterized. We observed a number of common structural characteristics in the amino acid sequences selected. The oligonucleotide encoding the amino acid sequence YDSRSMRPH was identified independently in plasmids pJKS15 and pJKS18, which suggested that at least part of this sequence is involved in coordination of ZnO. In addition, three different sequence motifs were discerned in the enriched sequences. In some cases these sequences were associated with the arginine-serine linker sequence incorporated into the genetic design of the random library. The ability to coordinate ZnO, however, was not strictly dependent on the presence of these motifs as other sequences were also selected during the enrichment procedure.

Taking into account the VNN design of the random library, we enriched the amino acids histidine, methionine, aspartate, and arginine to various degrees in the ZnO-binding sequences. Significantly, all of these amino acids have been previously observed to participate in metal-protein interactions (2). Histidine is known to be associated with the coordination of Zn2+ in zinc fingers and metalloproteins (37), and the charged radicals in aspartate and arginine could perhaps be involved in chelation of zinc. A sequence lacking histidine (pJKS10) was also isolated, which indicated that histidine is not absolutely required for adherence to ZnO.

In a previous study, Barbas et al. (2) identified peptide sequences that conferred the ability to coordinate Zn2+ in a phage-displayed semisynthetic combinatorial antibody library. Only 50% of the peptides identified contained histidine, which indicated that the presence of histidine in Zn2+-binding peptides is not required. We did not observe any similarities between the Zn2+-binding sequences identified by Barbas et al. (2) and the ZnO-binding sequences identified in this study. However, this could be explained simply by the fact that the metal targets were different in the two studies. In addition, a number of other factors intrinsic to the type of display system, such as the genetic structure of the random library, the buffers, the selection and enrichment procedure employed, and the flanking protein sequences, are known to affect the type of sequences enriched when these techniques are used.

Direct counting of cells of various clones revealed differences in the number of ZnO-binding cells, which indicated that the FimH display system allows selection of peptide sequences with a variety of binding avidities. In particular, one clone (pJKS9) exhibited a high affinity for ZnO compared to the other clones isolated. Furthermore, this sequence exhibited a remarkably high degree of similarity to a putative helicase motif found during a database search. Many helicases are known to be zinc-containing enzymes, and cloning of the putative helicase motif in FimH resulted in ZnO-binding cells, suggesting that this motif is indeed involved in zinc binding. These findings suggest that the technology described here might be used to identify binding domains in naturally occurring proteins.

Some of the ZnO-binding clones isolated also exhibited an affinity for CdO. Given the chemical relatedness of Zn and Cd, this result is not surprising. However, the presence of clones that adhered to ZnO but not to CdO indicates that metal-specific binding sequences can be identified by the procedures used. We are currently investigating this aspect of the process in order to better understand the rules governing metal-protein interactions.

Bacterial surface display of designer chelators in connection with type 1 fimbriae is a powerful system for engineering bacteria with biosorptive abilities. We can envisage that a heterobinary adhesin suitable for the development of biomatrices could be designed by using the natural d-mannose-binding domain of FimH in combination with a second engineered site. In this context the techniques described here may become valuable tools for capturing or immobilizing metal pollutants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Danish National Strategic Environmental Program.

We thank Stanley Brown for his help during this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agterberg M, Adriaanse H, van Bruggen A, Karperien M, Tommassen J. Outer-membrane PhoE protein of Escherichia coli K-12 as an exposure vector: possibilities and limitations. Gene. 1990;88:37–45. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbas C F, III, Rosenblum J S, Lerner R A. Direct selection of antibodies that coordinate metals from semisynthetic combinatorial libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6385–6389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boder E T, Wittrup K D. Yeast surface display for screening combinatorial polypeptide libraries. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:553–557. doi: 10.1038/nbt0697-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown S. Engineered iron oxide-adhesion mutants of the Escherichia coli phage lambda receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8651–8655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charbit A, Molla A, Saurin W, Hofnung M. Versatility of a vector for expressing foreign polypeptides at the surface of gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1988;70:181–189. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornelis P, Sierra J C, Lim A, Jr, Malur A, Tungpradabkul S, Tazka H, Leitao A, Martins C V, di Perna C, Brys L, De Bactseller P, Hamers R. Development of new cloning vectors for the production of immunogenic outer membrane fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. Bio/Technology. 1996;14:203–208. doi: 10.1038/nbt0296-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubel S, Breitling F, Fuchs P, Braunagel M, Klewinghaus I, Little M. A family of vectors for surface display and production of antibodies. Gene. 1993;128:97–101. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90159-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francisco J A, Campbell R, Iverson B L, Georgiou G. Production and fluorescence-activated cell sorting of Escherichia coli expressing a functional antibody fragment on the external surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10444–10448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freundl R. Insertion of peptides into cell-surface-exposed areas of the Escherichia coli OmpA protein does not interfere with export and membrane assembly. Gene. 1989;82:229–236. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuchs P, Breitling F, Dubel S, Seehaus T, Little M. Targeting recombinant antibodies to the surface of Escherichia coli: fusion to a peptidoglycan associated lipoprotein. Bio/Technology. 1991;9:1369–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt1291-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Georgiou G, Stathopoulos C, Daugherty P S, Nayak A R, Iverson B L, Curtiss R., III Display of heterologous proteins on the surface of microorganisms: from the screening of combinatorial libraries to live recombinant vaccines. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:29–34. doi: 10.1038/nbt0197-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanson M S, Brinton C C., Jr Identification and characterization of E. coli type-1 pilus tip adhesion protein. Nature. 1988;332:265–268. doi: 10.1038/332265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedegaard L, Klemm P. Type 1 fimbriae of Escherichia coli as carriers of heterologous antigenic sequences. Gene. 1989;85:115–124. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90471-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill H R, Stockley P G. Phage presentation. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:685–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones C H, Pinkner J S, Nicholes A V, Slonim L N, Abraham S N, Hultgren S J. FimC is a periplasmic PapD-like chaperone that directs assembly of type 1 pili in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8397–8401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones C H, Pinkner J S, Roth R, Heuser J, Nicholes A V, Abraham S N, Hultgren S J. FimH adhesin of type 1 pili is assembled into a fibrillar tip structure in the Enterobacteriaceae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2081–2085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klemm P. FimC, a chaperone-like periplasmic protein of Escherichia coli involved in biogenesis of type 1 fimbriae. Res Microbiol. 1992;143:831–838. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klemm P, Christiansen G. Three fim genes required for the regulation of length and mediation of adhesion of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;208:439–445. doi: 10.1007/BF00328136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klemm P, Christiansen G. The fimD gene required for cell surface localization of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;220:334–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00260505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klemm P, Hedegaard L. Fimbriae of Escherichia coli as carriers of heterologous antigenic sequences. Res Microbiol. 1990;141:1013–1017. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(90)90143-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klemm P, Jorgensen B J, van Die I, de Ree H, Bergmans H. The fim genes responsible for synthesis of type 1 fimbriae in Escherichia coli, cloning and genetic organization. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;199:410–414. doi: 10.1007/BF00330751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotrba P, Doleckova L, de Lorenzo V, Ruml T. Enhanced bioaccumulation of heavy metal ions by bacterial cells due to surface display of short metal binding peptides. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1092–1098. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1092-1098.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krogfelt K A, Bergmans H, Klemm P. Direct evidence that the FimH protein is the mannose-specific adhesin of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1995–1998. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1995-1998.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krogfelt K A, Klemm P. Investigation of minor components of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae: protein chemical and immunological aspects. Microb Pathog. 1988;4:231–238. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowe M A, Holt S C, Eisenstein B I. Immunoelectron microscopic analysis of elongation of type 1 fimbriae in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:157–163. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.157-163.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Z, Murray K S, van Cleave V, LaVallie E R, Stahl M L, McCoy J M. Expression of thioredoxin random peptide libraries on the Escherichia coli cell surface as functional fusions to flagellin: a system designed for exploring protein-protein interactions. Bio/Technology. 1995;13:366–372. doi: 10.1038/nbt0495-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macaskie L F. An immobilized cell bioprocess for the removal of heavy metals from aqueous flows. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 1990;49:357–379. doi: 10.1002/jctb.280490408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newton S M, Joys T M, Anderson S A, Kennedy R C, Hovi M E, Stocker B A. Expression and immunogenicity of an 18-residue epitope of HIV1 gp41 inserted in the flagellar protein of a Salmonella live vaccine. Res Microbiol. 1995;146:203–216. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)80276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pallesen L, Poulsen L K, Christiansen G, Klemm P. Chimeric FimH adhesin of type 1 fimbriae: a bacterial surface display system for heterologous sequences. Microbiology. 1995;141:2839–2848. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-11-2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pazirandeh M, Wells B M, Ryan R L. Development of bacterium-based heavy metal biosorbents: enhanced uptake of cadmium and mercury by Escherichia coli expressing a metal binding motif. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4068–4072. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.4068-4072.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott J K, Smith G P. Searching for peptide ligands with an epitope library. Science. 1990;249:386–390. doi: 10.1126/science.1696028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi Y, Berg J M. DNA unwinding induced by zinc finger protein binding. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3845–3848. doi: 10.1021/bi952384p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steidler L, Remaut E, Fiers W. Pap pili as a vector system for surface exposition of an immunoglobulin G-binding domain of protein A of Staphylococcus aureus in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7639–7643. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.23.7639-7643.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stentebjerg-Olesen B, Pallesen L, Jensen L B, Christiansen G, Klemm P. Authentic display of a cholera toxin epitope by chimeric type 1 fimbriae: effects of insert position and host background. Microbiology. 1997;143:2027–2038. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-6-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vallee B L, Auld D S. Zinc coordination, function, and structure of zinc enzymes and other proteins. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5647–5659. doi: 10.1021/bi00476a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Die I, Wauben M, van Megen I, Bergmans H, Riegman N, Hoekstra W, Pouwels P, Enger-Valk B. Genetic manipulation of major P-fimbrial subunits and consequences for formation of fimbriae. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5870–5876. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5870-5876.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]