Abstract

Sterigmatocystin (ST) and aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) are two polyketide-derived Aspergillus mycotoxins synthesized by functionally identical sets of enzymes. ST, the compound produced by Aspergillus nidulans, is a late intermediate in the AFB1 pathway of A. parasiticus and A. flavus. Previous biochemical studies predicted that five oxygenase steps are required for the formation of ST. A 60-kb ST gene cluster in A. nidulans contains five genes, stcB, stcF, stcL, stcS, and stcW, encoding putative monooxygenase activities. Prior research showed that stcL and stcS mutants accumulated versicolorins B and A, respectively. We now show that strains disrupted at stcF, encoding a P-450 monooxygenase similar to A. parasiticus avnA, accumulate averantin. Disruption of either StcB (a putative P-450 monooxygenase) or StcW (a putative flavin-requiring monooxygenase) led to the accumulation of averufin as determined by radiolabeled feeding and extraction studies.

The mycotoxins sterigmatocystin (ST) and aflatoxin (AF) have the same polyketide biosynthetic origin and are derived from the condensation of a hexanoyl starter unit with seven malonate units. ST is the final metabolite produced by A. nidulans, but in the related species A. parasiticus, ST is a late intermediate in the biosynthesis of AF. The biosynthetic and regulatory genes required for ST production in A. nidulans are homologous to those required for AF production in A. flavus and A. parasiticus (4, 27, 33). The genes for ST and AF are clustered in all three species, and the functions of nine ST cluster genes in A. nidulans are known (3, 5, 9, 11–14, 36, 37). Homologs for six of these genes, stcA (27, 34), stcE (26), aflR (6, 19), stcJ (22, 31), stcK (15), and stcU (23), in A. parasiticus and/or A. flavus have been described.

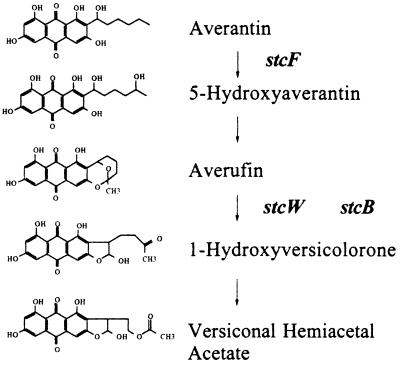

A particularly interesting aspect of this pathway is that several oxidative steps are required for AF or ST biosynthesis. Each of the major nuclear rearrangement steps (anthraquinone → xanthone → coumarin) requires a cytochrome P-450-mediated reaction, as does the desaturation of the dihydrobisfuran. Biochemical studies predict that five oxidases are necessary for ST biosynthesis (reviewed in references 2 and 18). The conversion of averantin to averufin requires at least two enzymatic steps, with one requiring incorporation of an oxygen molecule (2, 18) to form a putative intermediate described as either 5′-hydroxyaverantin (33) or averufanin (16), which is then likely transformed to averufin by a dehydrogenase activity (Fig. 1). Next, oxidation of averufin to form 1′-hydroxyversicolorone (25) (Fig. 1) is followed by oxygen incorporation into 1′-hydroxyversicolorone to produce versiconal hemiacetal acetate (25). A fourth oxidation—critical for the elaboration of carcinogenic metabolites—occurs when desaturation of the bisfuran ring of versicolorin B leads to the production of versicolorin A (17). The last oxidation step in ST formation takes place during the transformation of versicolorin A to demethyl-ST. We have previously described the genes encoding two P-450 monooxygenases responsible for the conversion of versicolorin B to versicolorin A (i.e., stcL) (12) and for the conversion of versicolorin A to demethyl-ST (i.e., stcS) (14). Our objective in this study was to link three more genes, stcF and stcB, encoding probable P-450 monooxygenases, and stcW, encoding a likely flavin monooxygenase, to the remaining oxidation steps in the ST pathway.

FIG. 1.

Proposed conversion of averantin to versiconal hemiacetal acetal in the AF-ST pathway. Steps at which stcF, stcW, and stcB function as described in this paper are indicated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and growth conditions.

All A. nidulans and A. parasiticus strains (Table 1) were maintained as silica or glycerol stocks. A. nidulans conidial suspensions (106 spores/ml) were made from cultures grown for 5 to 7 days at 37°C on minimal medium with appropriate supplements for auxotrophies (8). Conidial suspensions of A. parasiticus were prepared from fungi grown on potato dextrose agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) plates for 4 to 7 days at 30°C and subsequently transferred to 1 liter of AM (1) medium in 4-liter Erlenmeyer flasks. Flasks were incubated at 28 to 30°C in the dark with shaking at 175 rpm for 84 h.

TABLE 1.

Aspergillus strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| A. nidulans | ||

| PW1 | biA1 argB2 methG1 veA1 | FGSCa |

| TAHK87.15 | biA1 methG1 veA1 stcB::argB | This study |

| TAHK87.29 | biA1 methG1 veA1 stcB::argB | This study |

| TAHK87.59 | biA1 methG1 veA1 stcB::argB | This study |

| TAHK87.70 | biA1 methG1 veA1 stcB::argB | This study |

| TAHK87.78 | biA1 methG1 veA1 stcB::argB | This study |

| TAHK68.44 | biA1 methG1 veA1 stcF::argB | This study |

| TAHK79.4 | biA1 methG1 veA1 stcW::argB | This study |

| A. parasiticus | ||

| ATCC 56775 (SU-1) | Wild type | ATCCb |

| ATCC 24690 (NOR-1) | nor-1 | ATCC |

FGSC, Fungal Genetics Stock Center, Kansas City, Mo.

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.

Gene disruption vectors and fungal transformation.

Each gene (stcB, stcF, or stcW) was mutated in A. nidulans PW1 by either disruption or replacement of an internal portion of the specific coding region with the selectable marker argB by standard transformation procedures (11, 13). The coordinates of the stcB coding region within the ST cluster (GenBank accession no. U34740) are ca. 9005 to 10570, those of stcF are ca. 19510 to 21112, and those of stcW are ca. 52128 to 53663. No disruptions were made in introns. Disruption vectors pAHK87, pAHK68, and pAHK79 were used to transform A. nidulans PW1 to arginine prototrophy. Transformants were analyzed with Southern blots probed with DNA fragments from pAHK83, pAHK57, and pNK10 to identify stcB, stcF, and stcW disruption strains, respectively. Putative stcB::argB mutants also were analyzed by PCR amplification of the disrupted stcB open reading frame (ORF). All manipulations of nucleic acids, including labeling of probes, were carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (21).

stcB disruption plasmid pAHK87.

An ∼7-kb KpnI fragment was subcloned from pL11CO9 into pBluescript KS(−) to obtain pAHK23. A 2.58-kb BglII fragment from pAHK23 containing the stcB ORF was ligated into pK18, generating pAHK83. A 400-bp EcoRV fragment in the stcB ORF was deleted from pAHK83 by digestion and religation to obtain pAHK86. Next, a 1.8-kb SmaI fragment from pJYargB containing the argB gene was ligated into EcoRV-digested pAHK86 to generate pAHK87.

stcF disruption plasmid pAHK68.

A 6.0-kb BamHI fragment was subcloned from pL11CO9 in pBluescript KS(−) to obtain pAHK49. pAHK49 was digested with XbaI and religated to retain an ∼2.8-kb insert, generating pAHK53. The 2.8-kb BamHI/XbaI fragment from pAHK53 (which contained the ORF of stcF) was ligated into pK18, generating pAHK56. Finally, a 1.8-kb XhoI fragment from pSalArgB containing the argB gene was ligated into XhoI-digested pAHK56 to obtain pAHK68.

stcW disruption plasmid pAHK79.

pNK4, an ∼10-kb EcoRI subclone of cosmid pL24BO3 containing the entire stcW gene, was double digested with BglII/BamHI to release an ∼4.5-kb fragment, which was ligated into the BamHI site of pBluescript SK(−) to obtain plasmid pAHK76. The site-directed mutagenesis method of Kunkel (21) was used to eliminate a 504-bp fragment (coordinates 52030 to 52534) of the stcW encoding region in pAHK76. The sequence of the oligonucleotide used to replace this 504-bp region, 5′-GGCCCAGAGCCTCAAGATCTCCGGCGACAGCGG-3′, placed a novel BglII site in resulting plasmid pAHK77. The 1.8-kb argB BamHI fragment from pSalArgB was ligated into BglII-digested pAHK77 to obtain pAHK79.

Extraction and analysis of secondary metabolites from A. nidulans.

Oatmeal (Quaker Oats, Chicago, Ill.) porridge (3 g of oatmeal plus 3 ml of water) was inoculated with 3 × 108 spores of an A. nidulans strain, and the cultures were grown at 30°C for 6 days. Metabolites were extracted and prepared for thin-layer chromatography (TLC) or high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously described (11–14).

TLC analyses.

For ST and ST-AF precursors, samples (10 μl of the extract) were analyzed on TLC plates (silica gel, 250 μm thick, 20 by 20 cm; Analtech Inc., Newark, Del.) using benzene-acetic acid (95:5, vol/vol) or a ternary mixture of toluene-ethyl acetate-acetic acid (80:10:10, vol/vol/vol) with appropriate standards. For chromatographic analyses of AFB1, a ternary mixture of 6:3:1 chloroform-ethyl acetate-formic acid was utilized. ST is visualized by spraying with a 20% (wt/vol) aluminum chloride solution in ethanol (95%, vol/vol), whereas AF and its intermediates can be easily visualized under long-wave UV light. ST and AFB1 standards were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.

HPLC analyses.

Organic extracts were filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size nylon syringe filters (Alltech, Deerfield, Ill.), and 50 μl of this solution was analyzed by HPLC using a C18 column (250 by 4.60 mm; Phenomenex, Torrance, Calif.) on a Varian 5020 liquid chromatograph with an attached ABI model 1000S diode array detector (ABI, Ramsey, N.J.). ST and its intermediates were separated on a linear gradient that extended from 75% A–25% B to 40% A–60% B (where A is 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid–water and B is acetonitrile) in 55 min. The solvent composition was then held at 40% A–60% B from 55 to 59 min, followed by the introduction a mixture of 20% A–80% B, which was initiated at 60 min from the point of injection. Samples were analyzed by monitoring at A310 (flow rate, 1 ml/min).

Feeding experiments with radiolabeled norsolorinic acid.

A. nidulans stcB and stcW strains were cultured on minimal medium containing 1% oatmeal flakes and the appropriate supplements for auxotrophies. Erlenmeyer flasks (250 ml) were inoculated with 106 conidia per 50 ml of medium. The mycelia were cultured for 48 h at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. At 48 h of growth, 1 ml of a 1-mg/ml solution of radiolabeled norsolorinic acid (0.18 Ci/mol) (29) in dimethylformamide was added to each flask. The cells were grown for an additional 120 h at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. The mycelia were harvested by vacuum filtration, rinsed with distilled water, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and steeped in acetone overnight. The organics were concentrated in vacuo. The residue was resolubilized in 1 ml of methanol, and 200 μl of each sample was analyzed by HPLC as described above. Radioactivity in collected fractions was measured with a Beckman (Fullerton, Calif.) LS5801 Liquid Scintillation Counter.

RESULTS

stcB gene replacement.

Transformation of PW1 with pAHK87 resulted in five transformants, TAHK87.15, TAHK87.29, TAHK87.59, TAHK87.70, and TAHK87.78, each showing the 2,229- and 997-bp fragments indicative of an argB replacement of the stcB ORF (data not shown). This was confirmed by SacI restriction where the wild type contained 5,000- and 1,245-bp fragments and the five stcB::argB transformants contained 3,200-, 1,723-, and 1,245-bp fragments.

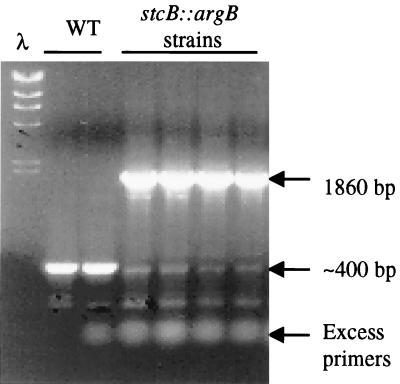

The stcB probe (pAHK83) has some sequence similarity to another genomic DNA fragment, probably from another monooxygenase. We confirmed gene replacement by synthesizing primers to either side of the EcoRV site where the argB gene replaced an internal section of the stcB ORF. PCR amplification of the wild-type strain yielded the expected 400-bp fragment, and amplification of all five stcB::argB strains yielded only the expected 1,860-bp fragment (Fig. 2); only the 400-bp fragments hybridized to the stcB probe (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

PCR amplification of stcB in wild-type (WT) isolates produce a 400-bp fragment of an internal section of the gene. PCR amplification of the analogous region in the stcB::argB strains produce a 1,860-bp fragment representing the argB gene which was exchanged for the 400 bp of the internal fragment of stcB. Lane λ contained molecular size markers.

stcF disruption.

Transformation of PW1 with pAHK68 resulted in one transformant, TAHK68.44, that carried the expected 6.9-kb and 934-bp fragments predicted for an argB disruption of stcF (data not shown).

stcW gene replacement.

One pAHK79 transformant (TAHK79.4) had the 8,854- and 3,011-bp BglII fragments and 5,964- and 1,853-bp HindIII fragments, indicating replacement of genomic stcW with argB (wild-type stcW patterns were a 6,187-bp HindIII and a 9,890-bp BglII fragment, respectively).

StcF mutant accumulates averantin.

TLC analysis of extracts derived from ΔstcF mutant TAHK68.44 revealed that it accumulated a metabolite that fluoresced yellow when exposed to long-wave UV light. This material had the same Rf as standard averantin when developed under a variety of TLC solvent conditions (including toluene-ethyl acetate-acetic acid at 50:30:4 [vol/vol] and benzene-acetic acid at 95:5 [vol/vol]). stcF (GenBank accession no. U34740) shares >70% identity with avnA (GenBank accession no. U62774), the gene for a putative P-450 from A. parasiticus. Deletion of avnA results in strains that accumulate averantin (35).

stcB and stcW mutants accumulate averufin.

Both the stcB and stcW inactivation mutants (TAHK87.29 and TAHK79.4, respectively) could not produce ST but accumulated averufin. Organic extracts from the stcB and stcW mutants had a peak with the same retention time as averufin but lacked the peak corresponding to ST. Coinjection with averufin confirmed these results. Feeding with 14C-labeled norsolorinic acid showed that both the stcB and stcW mutant strains produced high levels of averufin and that neither mutant demonstrated conversion to hydroxyversicolorone or to any subsequent intermediate of the pathway. Radioactive profiles generated from each strain were nearly identical, and no distinguishing features were observed. The finding that both the stcB and stcW genetic knockouts accumulated averufin was perplexing, as it seems that a single oxidative process mediates the transformation of averufin to hydroxyversicolorone.

DISCUSSION

The role of monooxygenases in metabolic conversions is of considerable interest. These enzymes are involved in both the catabolism and anabolism of many toxic compounds. Several fungal biosynthetic pathways—for example, the ST-AFB1, trichothecene (10), and gibberellin (28) pathways—require monooxygenase activities. Detailed studies of the AF pathway had assigned five monooxygenase steps up to ST synthesis and then an additional monooxygenase step for the conversion of O-methyl-ST to AFB1 (7, 20, 30). As ST biosynthesis in A. nidulans appears to be functionally identical to ST biosynthesis in the AF-producing fungi, the same ST-producing monooxygenase activities are probably present in both species.

The ST gene cluster in A. nidulans (4) includes five putative monooxygenase genes. Four of the genes (stcB, stcF, stcL, and stcS) appeared to encode P-450 monooxygenases, and one (stcW) appeared to encode a probable flavin-requiring monooxygenase. Disruption of stcL and stcS resulted in accumulation of ST and AFB1 intermediates, versicolorins B and A (12, 14), respectively. We hypothesized that the disruption of the three other genes would result in the accumulation of averantin, averufin, and 1′-hydroxyversicolorone. Disruption of stcF yielded a mutant that accumulated averantin, but disruption of either stcB or stcW resulted in the accumulation of averufin. No hydroxyversicolorone was detected in any of the mutants. Putative stcB and stcW homologs have been found in A. flavus and A. parasiticus (32) and are thought to be involved in the conversion of averufin to AF, but the exact function of these genes in these species has not been determined.

It is difficult to entertain reasons for the failure to detect hydroxyversicolorone in either the stcB- or stcW-inactivated strains or to differentiate them by their chemical profiles. Could StcW and StcB function as a dimer for both of the averufin-to-versiconal acetate conversion steps or for the averufin-to-hydroxyversicolorone conversion step alone? There are no reports of an oxygenation requiring both a P-450 and a flavin monooxygenase, and such a requirement seems unlikely. Possibly, though, one of the enzymes requires the other for proper functioning in a manner we do not yet understand such that StcW is not functional in a ΔstcB strain. There are some data that suggest that mutations within gene clusters can affect nontargeted genes (24), and perhaps a disruption in stcW could affect stcB expression or vice versa. We also cannot rule out the possibility that an additional monooxygenase, perhaps not located in the ST cluster, is required for this step. However, resolution of this issue lies beyond the scope of this paper and requires investigation of stcB and stcW both individually and pairwise to identify the catalytic function(s) of each and the extent to which protein-protein interaction affects their behavior.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Miguel Arriaga for his technical assistance and Daren Brown for critical reading of the manuscript.

This research was supported by funds from the USDA-Cooperative State Research Service (96-35303-3415) to N.P.K. and T.H.A. and the National Institutes of Health (ES01670) to C.A.T.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adye J, Mateles R I. Incorporation of labelled compounds into aflatoxin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1964;86:418–420. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(64)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatnagar D, Ehrlich K C, Cleveland T E. Oxidation-reduction reactions in biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. In: Bhatnagar D, Lillehoj E B, Arora D K, editors. Handbook of applied mycology. Vol. 5. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1991. pp. 255–286. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown D W, Adams T H, Keller N P. Aspergillus has distinct fatty acid synthases for primary and secondary metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14873–14877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown D W, Yu J-H, Kelkar H S, Fernandes M, Nesbitt T C, Keller N P, Adams T H, Leonard T J. Twenty-five co-regulated transcripts define a secondary metabolism gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1418–1422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butchko R A E, Adams T H, Keller N P. Aspergillus nidulans mutants defective in stc gene cluster regulation. Genetics. 1999;153:715–720. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.2.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang P-K, Cary J W, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Bennett J W, Linz J E, Woloshuk C P, Payne G A. Cloning of the Aspergillus parasiticus apa-2 gene associated with the regulation of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3273–3279. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3273-3279.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleveland T E, Lax A R, Lee L S, Bhatnagar D. Appearance of enzyme activities catalyzing conversion of sterigmatocystin to aflatoxin B1 in late-growth-phage Aspergillus parasiticus cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1711–1713. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.7.1711-1713.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cove D J. The induction and repression of nitrate reductase in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;113:51–56. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6593(66)80120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandes M, Keller N P, Adams T H. Sequence-specific binding by Aspergillus nidulans AflR, a C6 zinc cluster protein regulating mycotoxin biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1355–1365. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hohn T M, Desjardins A E, McCormick S P. The Tri4 gene of Fusarium sporotrichioides encodes a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase involved in trichothecene biosynthesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;248:95–102. doi: 10.1007/BF02456618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelkar H S, Keller N P, Adams T H. Aspergillus nidulans stcP encodes an O-methyltranferase that is required for sterigmatocystin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4296–4298. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4296-4298.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelkar H S, Skloss T W, Haw J F, Keller N P, Adams T H. Aspergillus nidulans stcL encodes a putative P-450 monooxygenase required for bisfuran desaturation during aflatoxin/sterigmatocystin biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1589–1594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller N P, Kantz N J, Adams T A. Aspergillus nidulans verA is required for production of the mycotoxin sterigmatocystin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1444–1450. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1444-1450.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller N P, Segner S, Bhatnagar D, Adams T H. stcS, a putative P-450 monooxygenase, is needed for the conversion of versicolorin A to sterigmatocystin in Aspergillus nidulans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3628–3632. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3628-3632.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahanti N, Bhatnagar D, Cary J W, Joubran J, Linz J E. Structure and function of FAS-1A, a gene encoding a putative fatty acid synthetase directly involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus parasiticus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:191–195. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.191-195.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCormick S P, Bhatnagar D, Lee L S. Averufanin is an aflatoxin B1 precursor between averantin and averufin in the biosynthetic pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:14–16. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.1.14-16.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGuire S M, Townsend C A. Demonstration of Baeyer-Villiger oxidation and the course of cyclization in bisfuran ring formation during aflatoxin B1 biosynthesis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1993;3:653–656. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minto R E, Townsend C A. Enzymology and molecular biology of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2535–2555. doi: 10.1021/cr960032y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Payne G A, Nystrom G J, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Woloshuk C P. Cloning of the afl-2 gene involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis from Aspergillus flavus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:156–162. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.1.156-162.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prieto R, Woloshuk C P. ord1, an oxidoreductase gene responsible for conversion of O-methylsterigmatocystin to aflatoxin in Aspergillus flavus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1661–1666. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.1661-1666.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva J C, Minto R E, Barry III C E, Holland K A, Townsend C A. Isolation and characterization of the versicolorin B synthase gene from Aspergillus parasiticus: expansion of the aflatoxin B1 biosynthetic gene cluster. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13600–13608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skory C D, Chang P-K, Cary J, Linz J E. Isolation and characterization of a gene from Aspergillus parasiticus associated with the conversion of versicolorin A to sterigmatocystin in aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3527–3537. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.11.3527-3537.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sophianopoulou V, Suarez T, Diallinas G, Scazzocchio C. Operator derepressed mutations in the proline utilisation gene cluster of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;236:209–213. doi: 10.1007/BF00277114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Townsend C A, Plavcan K A, Pal K, Brobst S W, Irish M S, Ely E W J, Bennett J W. Hydroxyversicolorone: isolation and characterization of a potential intermediate in aflatoxin biosynthesis. J Org Chem. 1988;53:2472–2477. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trail F, Chang P-K, Cary J, Linz J E. Structural and functional analysis of the nor-1 gene involved in the biosynthesis of aflatoxins by Aspergillus parasiticus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4078–4085. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.11.4078-4085.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trail F, Mahanti N, Rarick M, Mehigh R, Liang S-H, Zhou R, Linz J E. Physical and transcriptional map of an aflatoxin gene cluster in Aspergillus parasiticus and functional disruption of a gene involved early in the aflatoxin pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2665–2673. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2665-2673.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tudzynski B, Hölter K. Gibberellin biosynthetic pathway in Gibberella fujikuroi: evidence for a gene cluster. Fungal Genet Biol. 1998;25:157–170. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1998.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe C M H, Townsend C A. The in vitro conversion of norsolorinic acid to aflatoxin B1. An improved method of cell-free enzyme preparation and stabilization. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:6231–6239. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe C M H, Townsend C A. Incorporation of molecular oxygen in aflatoxin B1 biosynthesis. J Org Chem. 1996;61:1990–1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe C M H, Wilson D, Linz J E, Townsend C A. Demonstration of the catalytic roles and evidence for the physical association of type I fatty acid synthase and a polyketide synthase in the biosynthesis of aflatoxin B1. Chem Biol. 1996;3:463–469. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woloshuk C, Prieto R. Genetic organization and function of the aflatoxin B1 biosynthetic genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;160:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yabe K, Nakamura Y, Nakajima H, Ando Y, Hamasaki T. Enzymatic conversion of norsolorinic acid to averufin in aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1340–1345. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.5.1340-1345.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu J, Chang P-K, Cary J W, Wright M, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Payne G A, Linz J E. Comparative mapping of aflatoxin pathway gene clusters in Aspergillus parasiticus and Aspergillus flavus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2365–2371. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2365-2371.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu J, Chang P-K, Cary J W, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E. avnA, a gene encoding a cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase, is involved in the conversion of averantin to averufin in aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus parasiticus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1349–1356. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1349-1356.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu J-H, Leonard T J. Sterigmatocystin biosynthesis in Aspergillus nidulans requires a novel type I polyketide synthase. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4792–4800. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4792-4800.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu J-H, Butchko A E, Fernandes M, Keller N P, Leonard T J, Adams T H. Conservation of structure and function of the aflatoxin regulatory gene aflR from Aspergillus nidulans and A. flavus. Curr Genet. 1996;29:549–555. doi: 10.1007/BF02426959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]