Abstract

Sirtuins are NAD+-dependent protein lysine deacylase and mono-ADP ribosylases present in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. The sirtuin family comprises seven isoforms in mammals, each possessing different subcellular localization and biological functions. Sirtuins have received increasing attention in the past two decades given their pivotal functions in a variety of biological contexts, including cytodifferentiation, transcriptional regulation, cell cycle progression, apoptosis, inflammation, metabolism, neurological and cardiovascular physiology and cancer. Consequently, modulation of sirtuin activity has been regarded as a promising therapeutic option for many pathologies. In this review, we provide an up-to-date overview of sirtuin biology and pharmacology. We examine the main features of the most relevant inhibitors and activators, analyzing their structure–activity relationships, applications in biology, and therapeutic potential.

Keywords: : aging, cancer, drug discovery, epigenetics, metabolism, neurodegeneration, protein lysine deacylation, sirtuin modulators, sirtuins

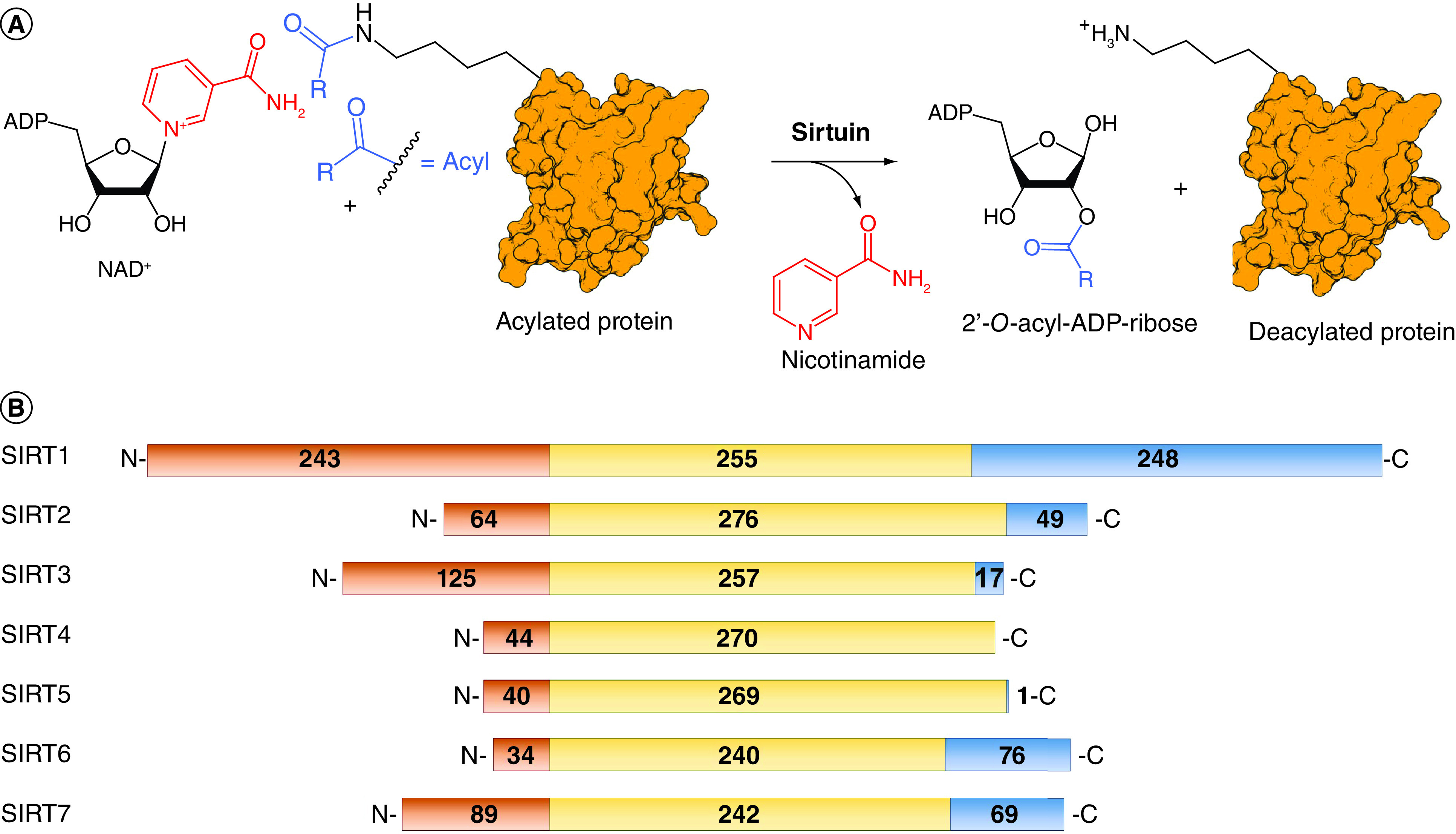

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are epigenetic enzymes that catalyze the removal of acetyl groups from the ε-N-acetyl lysine residues of histones and nonhistone proteins, thus balancing the action of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) [1,2]. Sirtuins (SIRTs) are regarded as class III HDACs, which necessitate nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) as cosubstrate for their catalytic activity [3] (Figure 1A). Originally identified in yeast as regulators of lifespan, mammalian sirtuins are involved in a wide range of biological functions. Their dysregulation is implicated in different disorders, including neurodegeneration, metabolic and cardiovascular diseases and cancer [4]. SIRTs are also viable targets for antiparasitic therapies because they play critical roles in parasites life cycle [5].

Figure 1. . Sirtuins: similar catalytic mechanism but different sequences.

(A) Schematic representation of the deacylation reactions catalyzed by sirtuins. (B) Sirtuins amino acid sequence alignment. The N-terminal domain is represented in orange, the C-terminal domain in blue, and the catalytic domain in yellow.

To date, the sirtuin family includes seven isoforms (SIRT1–7) possessing different subcellular localization and substrate specificity. SIRT1, SIRT6 and SIRT7 are mostly nuclear proteins, although a fraction of SIRT1 can be found in the cytosol. Conversely, SIRT2 is predominantly cytoplasmatic, although a particular spliced isoform is localized in the nucleus in certain conditions. SIRT3–5 are primarily found in mitochondria [6]. As for their catalytic activity, SIRT1–3 mainly act as deacetylases [7], while SIRT4 and SIRT6 possess a substrate-specific mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase activity in addition to their deacetylase activity [8,9]. They also act as deacylases, with a preference for 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl (HMG)-lysines for SIRT4 [10,11], and long-chain fatty acyl moieties in the case of SIRT6 [12]. SIRT5 has been reported to have potent deacylase activity on glutaryl-, succinyl- and malonyl-lysine residues [13–16]. Finally, SIRT7 is endowed with both desuccinylase and deacetylase activity [17].

Structural features & biological roles of sirtuins

Sirtuins share a preserved catalytic domain of 240–276 residues, comprising a small zinc-binding motif and a Rossmann-fold domain. The isoform-specific N- and C-terminal domains of SIRTs regulate their activity and subcellular localization [15]. Notably, SIRT4 and SIRT5 do not possess a C-terminal domain and have a tiny N-terminal mitochondria-localizing tag (Figure 1B) [15]. The binding region for the acylated substrates and NAD+ is located in a groove between the two subdomains, acting as the main catalytic site, close to a cosubstrate-binding loop [15]. Despite the shared catalytic mechanism (Figure 1), each isoform has distinct substrate preferences owing to small variations in their substrate binding pocket. Moreover, the active site channel presents isoform-specific variations determining the preferential binding to different acylated substrates [18]. These differences have been widely exploited to provide selective sirtuin modulators as described in the next sections [19–22].

SIRT1

SIRT1 is the closest mammalian homolog of the yeast protein Sir2 and it is the first human sirtuin to be identified and linked to aging [23]. SIRT1 directly regulates genome stability, stress response, inflammation and apoptosis [24] and has a central role in glucose and lipid metabolism [25].

SIRT1 is involved in several neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson disease (PD), Alzheimer disease (AD) and Huntington disease (HD) [26]. In AD, SIRT1 facilitates the degradation of β-amyloid in primary astrocytes through the deacetylation of lysosome-related proteins, thereby increasing the number of lysosomes [27]. SIRT1 expression was also associated with improved survival rate and brain-derived neurotropic factor expression in a HD mouse model [28]. In contrast, SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of mutant huntingtin has been shown to prevent its degradation [29], and knockout or inhibition of Sir2 (SIRT1 homolog in Drosophila melanogaster) had neuroprotective effects in a HD Drosophila model [30]. In line with this, subsequent studies analyzing cellular and animal HD models suggested that the pharmacological inhibition of hSIRT1 could revert the neurodegenerative process and restore neural functions [31].

SIRT1 is also involved in cardiovascular disorders and cancer, where it shows a double-faced role [32]. For instance, SIRT1-catalyzed deacetylation inactivates the oncosuppressor p53 [23] and activates the DNA repair protein Ku70, leading to suppression of Bax-mediated apoptosis [33]. Although SIRT1 is overexpressed in a wide range of tumors, it can also behave as an onco-suppressor. Indeed, SIRT1 defends cells from oncogenic mutations, mediating pro-apoptotic effects, as exemplified by its role in the sensitization of cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis through the deacetylation of NF-κB [4].

SIRT2

SIRT2 is mainly expressed in the brain and its levels correlate to the onset of several neurological disorders, where it seems to enhance disease progression [26]. For instance, SIRT2 inhibition protects neurons from the toxicity inducted by α-synuclein, a risk factor involved in familial PD [34]. In AD mouse models, suppression of SIRT2 activity was reported to reduce the expression of BACE1, decreasing Aβ accumulation and improving cognitive impairment [35]. SIRT2 inhibition protects neurons and increases lifespan in HD mouse models by decreasing polyglutamination at the N-terminal region of huntingtin [36]. SIRT2 also regulates apoptosis and cell cycle progression by modulating H4K16, p53 and NF-κB p65 subunit acetylation levels [37]. Like other sirtuins, SIRT2 has a controversial role in tumorigenesis because it acts as either a tumor suppressor or promoter in different physiopathological settings [38]. SIRT2 expression is indeed downregulated in certain malignancies (e.g., gliomas, lung and breast cancer) while it is upregulated in others (e.g., acute myeloid leukemia [AML)] and neuroblastoma) [37,38]. Finally, SIRT2 works at cytoplasmatic level mostly as an α-tubulin deacetylase, playing a crucial role in the oligodendrocyte differentiation [39].

SIRT3

SIRT3 is primarily a mitochondrial protein distributed in mitochondria-rich organs such as liver, heart and kidneys [40]. Nonetheless, the existence or catalytic activity of a nuclear long-chain SIRT3 isoform remains disputed, and further experiments are necessary to clarify this controversy [41,42]. Current evidence indicates that SIRT3 is a neuroprotective factor. For instance, SIRT3 upregulation increases neuronal survival and improves motor functions in an HD mouse model [43]. Under caloric restriction, SIRT3 deacetylates and activates IDH2, resulting in higher levels of NADPH and reduced glutathione in the mitochondria, protecting against oxidative stress [44]. Through its deacetylase activity, SIRT3 also activates SOD2, thereby mediating the microglia response to oxidative pressure [45]. SIRT3 plays a controversial role in cancer, where it can act as either a tumor promoter (e.g., in head and neck squamous carcinomas) or suppressor (e.g., in hepatocellular, breast and prostate cancers) in a context-dependent manner [46]. One of the most important tumor suppressive roles of SIRT3 is the inhibition of the Warburg effect, a modification of glucose metabolism in tumor cells in which ATP is produced mostly by anaerobic glycolysis to quickly generate energy and sustain cancer proliferation. Indeed, SIRT3 inhibits HIF1α, one of the main proteins activating glycolysis-related genes. Specifically, SIRT3 deacetylates and activates prolyl hydroxylases, which in turn hydroxylate HIF1α triggering its proteasomal degradation [47].

SIRT4

SIRT4 is a mitochondrial mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase [48], lipoamidase [49] and deacetylase [18,50], which also possesses a significant broad spectrum deacylase activity, with a preference for HMG [10,11], as revealed by the crystal structure of Xenopus tropicalis SIRT4 [10]. Notably, de-HMG-ylation has a relevant role in the control of leucine metabolism and, consequently, insulin secretion [11]. SIRT4 regulates a variety of cellular processes, including glucose, amino acid and lipid metabolism, ROS generation and apoptosis. Hence, its dysregulation is linked to metabolism and aging-related disorders, including cardiac hypertrophy, neurodegeneration, obesity, Type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [51]. Moreover, SIRT4 has multifaceted roles in cancer [8]. Indeed, it may act as oncosuppressor by modulating genome stability both in normal and cancer cells in response to DNA damage [52]. On the other hand, protection of cancer cells from DNA damage or endoplasmic reticulum stress may also promote cancer cell growth and survival [53].

SIRT5

SIRT5 is primarily located in the mitochondria and mainly distributed in brain, liver, kidneys, muscle, heart and testes [14,54]. SIRT5 possesses a weak deacetylase activity, and it mainly catalyzes lysine deglutarylation (highest activity), desuccinylation and demalonylation (lowest activity) at both enzymatic and cellular level [13–16,55]. Its substrates play crucial roles in ROS detoxification and metabolic processes such as fatty acid oxidation, glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, ketone body formation, glutamine metabolism and ammonia detoxification [56]. Given its role in regulating ROS levels, SIRT5 has protective functions in neurodegenerative disorders [57], while it may act as either a tumor promoter or suppressor. SIRT5 facilitates cancer cell proliferation by targeting different metabolic enzymes, including PKM2 and SHMT2 [14]. It promotes tumorigenesis in AML, prostate cancer, melanoma, breast cancer, ovarian cancer and colorectal carcinoma (CRC) [58,59]. Conversely, SIRT5 acts as an oncosuppressor in glioma, gastric cancer and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [59,60]. Furthermore, SIRT5 has a dual function even in the same cancer type, such as in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), lung cancer and breast cancer [14,59]. Hence, the role of SIRT5 in tumorigenesis depends not only on the cancer type but is highly related to the specific stage of the disease.

SIRT6

SIRT6 is a nuclear sirtuin possessing deacetylase, deacylase and NAD+-dependent mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase activities [9], with a preference toward long-chain fatty acyl moieties (e.g., myristoyl) [12]. SIRT6 is a major regulator of DNA damage repair, stem cell differentiation, glucose and lipid metabolism, inflammation, immunity, circadian rhythm and aging processes, and its activity has been linked to beneficial effects on health and lifespan [61]. SIRT6-mediated deacetylation of H3K9 and H3K56 facilitates DNA repair and telomeric preservation [62,63] and also regulates TNF-α secretion through its demyristoylase activity, thereby modulating the inflammation processes [64]. Consistent with its pleiotropic activity, SIRT6 has been reported to act as either a tumor promoter or suppressor depending on the biological context [65]. Through H3K9 deacetylation, SIRT6 reduces HIF1α and glycolytic genes expression, thereby opposing the Warburg effect and acting as an oncosuppressor in colorectal, breast and bladder cancer [66]. Conversely, its protective role against DNA damage may favor tumor growth and resistance to chemotherapy, as in the case of multiple myeloma and prostate cancer [65,66]. Hence, SIRT6 activation or inhibition might be important in specific cancer types.

SIRT7

SIRT7 is exclusively located in the nucleolus [17] and regulates genome stability, cell proliferation, stress protection, rDNA transcription and rRNA expression via its deacetylase and desuccinylase activities on both histone and nonhistone proteins [67,68]. SIRT7 selectively deacetylates H3K18, and this activity supports tumorigenic transformation and proliferation [68]. In addition, SIRT7 is overexpressed in HCC and breast cancer, and it has a clear metastatic potential in prostate and gastric malignancies [69].

Pharmacological modulation of sirtuins

The double-faced involvement of SIRTs in many biological processes, including aging, metabolism, neurodegeneration, and cancer prompted many laboratories to develop both sirtuin inhibitors (SIRTi) and activators (SIRTa). These molecules have shown a potential as chemical tools to investigate the roles of SIRTs in several physiological and pathological settings. They also represent the starting point for the development of novel therapeutics, with a preference for activators in the case of SIRT1, SIRT6 and inhibitors for SIRT3, SIRT4 and SIRT5. The following sections describe in detail the most relevant SIRTi and SIRTa identified so far.

Sirtuin inhibitors

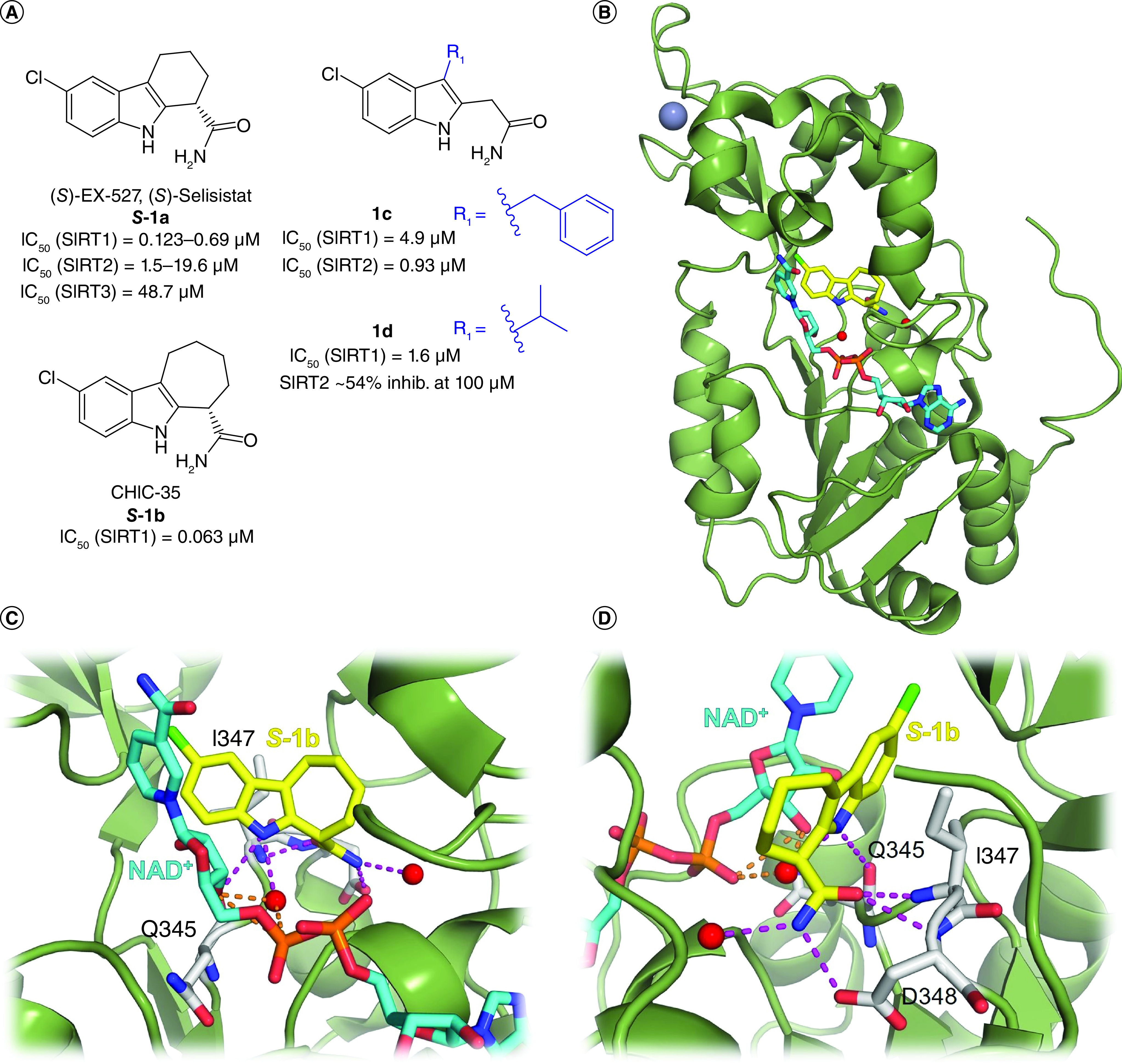

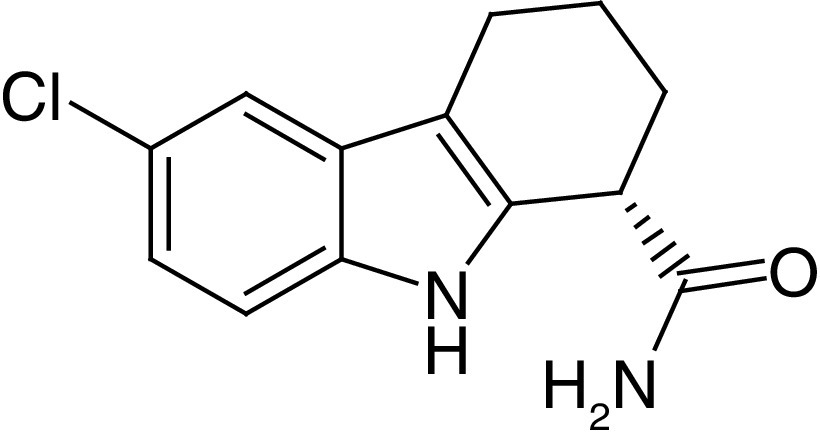

EX-527, also called Selisistat (1a, Figure 2), is the first potent and cell permeable SIRT1i reported in literature. Notably, only the S-enantiomer of 1a (S-1a) possesses inhibitory activity (IC50 = 0.12 μM), while the R-enantiomer is inactive. Different enzymatic tests indicated a SIRT1 selectivity of 1a over SIRT2, SIRT3, class I and II HDACs and NAD+ glycohydrolase (Table 1) [70]. Later reports showed that the inhibitory potency and the selectivity profile were highly affected by assay conditions, particularly the substrate choice, suggesting lower (up to 2-fold) selectivity over SIRT2 [71–73]. In any case, the mode of action of 1a is clear: following the formation of the alkylimidate intermediate, 1a binds to the SIRT1 nicotinamide binding cleft (called C-pocket) in the active site, forming a stable complex with SIRT1 which blocks the release of the coproduct 2′-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose [74]. A co-crystal structure of hSIRT1 catalytic domain bound to NAD+ and a 1a analogue (1b) confirmed the binding mode to SIRT1. The structure showed that the eutomer of 1b (S-1b, also called CHIC-35) binds deeply into the catalytic pocket and forms different hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds, including those with Gln345, Ile347, Asp348 and two conserved water molecules. From the structure, S-1b seems to displace the nicotinamide and forces NAD+ to assume an extended conformation which prevents substrate binding. However, this binding mode does not fully fit kinetic data [75]. Notably, 1a displayed promising pharmacokinetic (PK) properties, consisting of optimal bioavailability, metabolic stability and cell permeability [70], thereby stimulating its use not only as chemical probe but also as a potential drug. Consequently, 1a has been assessed in various clinical trials, and two of them have already been concluded. Specifically, one phase I clinical trial indicated that 1a is safe and well tolerated in early-stage HD patients at 10 and 100 mg/day. At those concentrations, clinical, neuropsychiatric and cognitive improvements from baseline (day -1) to day 1 were observed, with no further amelioration at day 14 [76]. Several reports showed that 1a increases p53 acetylation in different cancer cell lines, improves the efficacy of cytotoxic agents and exhibits anticancer properties in various cellular and xenograft mouse cancer models (Table 1) [77–79]. On the other hand, while 1a augmented the cytotoxicity of gemcitabine in the human pancreatic cancer cell line PANC-1 cells [80], when tested in a pancreatic cancer mouse xenograft using the same cell line, it stimulated tumor growth.

Figure 2. . Selisistat, its derivatives and its binding mode to hSIRT1.

(A) Structures of Selisistat (S–1a) and its derivatives 1b–d with relative sirtuin inhibition data. (B) x-ray crystal structure of hSIRT1 catalytic domain in complex with CHIC-35 (S-1b; PDB ID: 4I5I) [75]. (C & D) Details of SIRT1/S-1b interactions showing the hydrogen bonds with Q345, I347, D348 and conserved water molecules. SIRT1 is colored in green with selected residues shown as white sticks, S-1b is represented as yellow sticks, NAD+ is represented as cyan sticks, the hydrogen bonds in which S-1b is involved are represented as magenta dotted lines, the hydrogen bonds in which NAD+ is involved are represented as orange dotted lines, water molecules are represented as red spheres, Zn2+ is represented as a dark sphere.

Table 1. . Most relevant sirtuin inhibitors.

| Compound | Structure | Effects on sirtuin activity | Cellular and in vivo effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S-1a (S)-EX-527 (S)-Selisistat |

|

IC50 (SIRT1) = 0.12–0.69 μM IC50 (SIRT2) = 1.5–19.6 μM IC50 (SIRT3) = 48.7 μM |

– Safe and well tolerated in HD patients. – Provides benefits in early-stage HD patients. – p53 acetylation increase in different cancer cell lines and improved the efficacy of cytotoxic agents. – Reduction of cell survival and migration in HepG2 and Huh7 HCC cell lines. – Block of cell migration and EMT of chemotherapy-resistant esophageal cancer cells. – Decrease of colony formation of ovarian carcinoma cells. – Reduced tumor growth in both lung and endometrial cancer xenograft mouse models. – Increased gemcitabine cytotoxicity in pancreatic cancer PANC-1 cells, but also increase tumor growth in a PANC-1 xenograft model. |

[70–73,76–80] |

|

3a AGK2 |

|

IC50 (SIRT2) = 3.5 μM IC50 (SIRT1, 3) >50 μM |

– Increases α-tubulin acetylation in HeLa cells. – Rescues dopaminergic neurons from α-synuclein toxicity in various PD models. |

[34] |

|

3b MC2494 |

|

IC50 (SIRT1) = 38.5 μM IC50 (SIRT2) = 58.6 μM Inhib. at 50 μM: SIRT3 ∼45% SIRT4 ∼63% SIRT5 ∼85% SIRT6 ∼55% |

– Anticancer effects in vitro, in vivo (in both allograft and xenograft models) and in leukemic blasts ex

vivo. – Increases RIP1 acetylation and stimulates RIP1/caspase-8-mediated apoptosis. – Counteracts the chemically induced hyperproliferation of mammary gland. – Blocks mitochondrial biogenesis and functions. |

[81,82] |

| 4a Salermide |

|

IC50 (SIRT1) = 42.8 μM IC50 (SIRT2) = 25.0 μM |

– Promotes tumor-specific cell death in a wide range of human cancer cell lines, including CRC and GBM CSCs. – Induces apoptosis in a p53-dependent manner through the reactivation of proapoptotic genes that are epigenetically repressed by SIRT1. – Rescues the toxicity of the SIRT1-regulated mutant PABPN1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mutant PABPN1 causes nuclear collapse and motility defects in C. elegans, whereas in humans it causes oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. |

[83–85] |

| 8a |

|

IC50 (SIRT1) = 10.2 μM IC50 (SIRT2) = 0.048 μM IC50 (SIRT3) = 44.2 μM |

– Increases α-tubulin acetylation. – Cytotoxic activity against breast cancer, chronic myelogenous leukemia and human prostate cancer cell lines, with IC50 values of 30.6, 26.2 and 33.3 μM, respectively. |

[86] |

|

11a TM |

|

IC50 (SIRT1) = 98 μM IC50 (SIRT2) = 0.028–0.034 μM IC50 (SIRT3, 5–7) >200 μM |

– Anticancer activity in human breast cancer cells, particularly c-Myc-driven cancers. – Cancer growth suppression in immunocompromised mouse models of breast cancer. – Induces ubiquitination and degradation of c-Myc through SIRT2 inhibition. |

[87] |

|

13a SirReal2 |

|

IC50 (SIRT2) = 0.14–0.44 μM Inhib. at 100 μM: SIRT1 ∼22% SIRT3 no inhibition Inhibition at 200 μM: SIRT4, 5 no inhibition SIRT6 ∼22% inhibition |

– Hyperacetylation of α-tubulin and microtubule network in HeLa cells, without alteration of cell cycle distribution. | [19,88] |

| 14a |

|

IC50 (SIRT2) = 42 nm IC50 (SIRT1, 3) >300 μM |

– Dose-dependent decrease of the viability of breast cancer cells, and no cytotoxicity detected in a human normal liver cell line. – α-tubulin acetylation increase. |

[89] |

| 16 |

|

IC50 (SIRT2) = 63.0 μM IC50 (SIRT3) = 4.5 μM IC50 (SIRT1, 5) >100 μM |

– Regulates the acetylation levels of mitochondrial proteins and affects the production of ATP. – Increases global mitochondrial acetylation levels of HeLa cells (without affecting protein expression) and causes a reduction of ATP levels. |

[90] |

|

18b DK1-04 |

|

IC50 (SIRT5) = 0.34 μM SIRT1–3, 6 no inhibition at 83.3 μM |

Tested as aceto-methoxy (18c–am) or ethyl ester (18c-et): – both prodrugs increase global succinylation levels in breast cancer cells; – both prodrugs suppress the anchorage-independent growth of breast cancer lines in vitro, with 18c–et being the most potent; – 18c-et inhibits breast cancer growth in vivo, in both genetically engineered and xenotransplant mouse models. |

[91] |

| 19b |

|

IC50 (SIRT5) = 0.37 μM SIRT1–3, 6 no inhibition at 10 μM |

Tested as ethyl ester (19b–et) in SIRT5-dependent (OCI-AML2 and SKM-1) and SIRT5-independent (KG1a and Marimo) AML cell lines showed anticancer activity only in OCI-AML2 and SKM-1 cells. IC50 values between 5 and 8 μM; >80% apoptosis at 5 μM (SKM-1) and 10 μM (OCI-AML2). | [20,58] |

AML: Acute myeloid leukemia; CRC: Colorectal cancer; CSC: Cancer stem cell; EMT: Epithelial–mesenchymal transition; GBM: Glioblastoma multiforme; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; HD: Huntington’s disease; PD: Parkinson’s disease.

In 2020, Laaroussi et al. reported a new series of achiral analogues of 1a obtained by opening its fused cyclohexane [73]. Although the primary carboxyamide was kept because it establishes key interactions with SIRT1, a systematic structure–activity relationship (SAR) study aimed at optimizing the interactions with the small hydrophobic pocket of SIRT1 indicated that substituents in position 3 of the indole core influence the inhibitory activity and selectivity. Indeed, compound 1c, which bears a benzyl substituent at C3 (Figure 2), inhibits both SIRT1 and SIRT2 in the low micromolar range, being more potent toward the latter (IC50 [SIRT1] = 4.9 μM, IC50 [SIRT2] = 0.93 μM), and was more cytotoxic than 1a in CRC cells HCT-116 and HT-29. Compound 1d, which instead carries an isopropyl substituent at the indole C3 position, was the most potent inhibitor of the series (IC50 = 1.6 μM against SIRT1) with high selectivity over SIRT2 (Figure 2A) [73].

The dihydro-1,4-benzoxazine carboxamides 4.22 (2a, IC50[SIRT1] = 0.15 μM) and 4.27 (2b, IC50[SIRT1] = 0.22 μM; Figure 3), called Sosbo (‘sirtuin one selective benzoxazines’), have been recently described as submicromolar SIRT1-selective inhibitors [92]. Notably, 2b possesses a stereogenic center and, similar to 1a, the S-enantiomer (S-2b) is the eutomer (IC50[SIRT1] = 0.11 μM), with the R-enantiomer being 400 times less potent. Both 2a and 2b permeate cellular membranes and enhance p53 acetylation levels in human breast adenocarcinoma MDA-MB-231 cells. Kinetic studies indicated that both molecules are uncompetitive inhibitors like 1a. Moreover, docking studies highlighted that the Sosbo benzoxazine core overlaps with S-1b in the SIRT1 crystal structure [92].

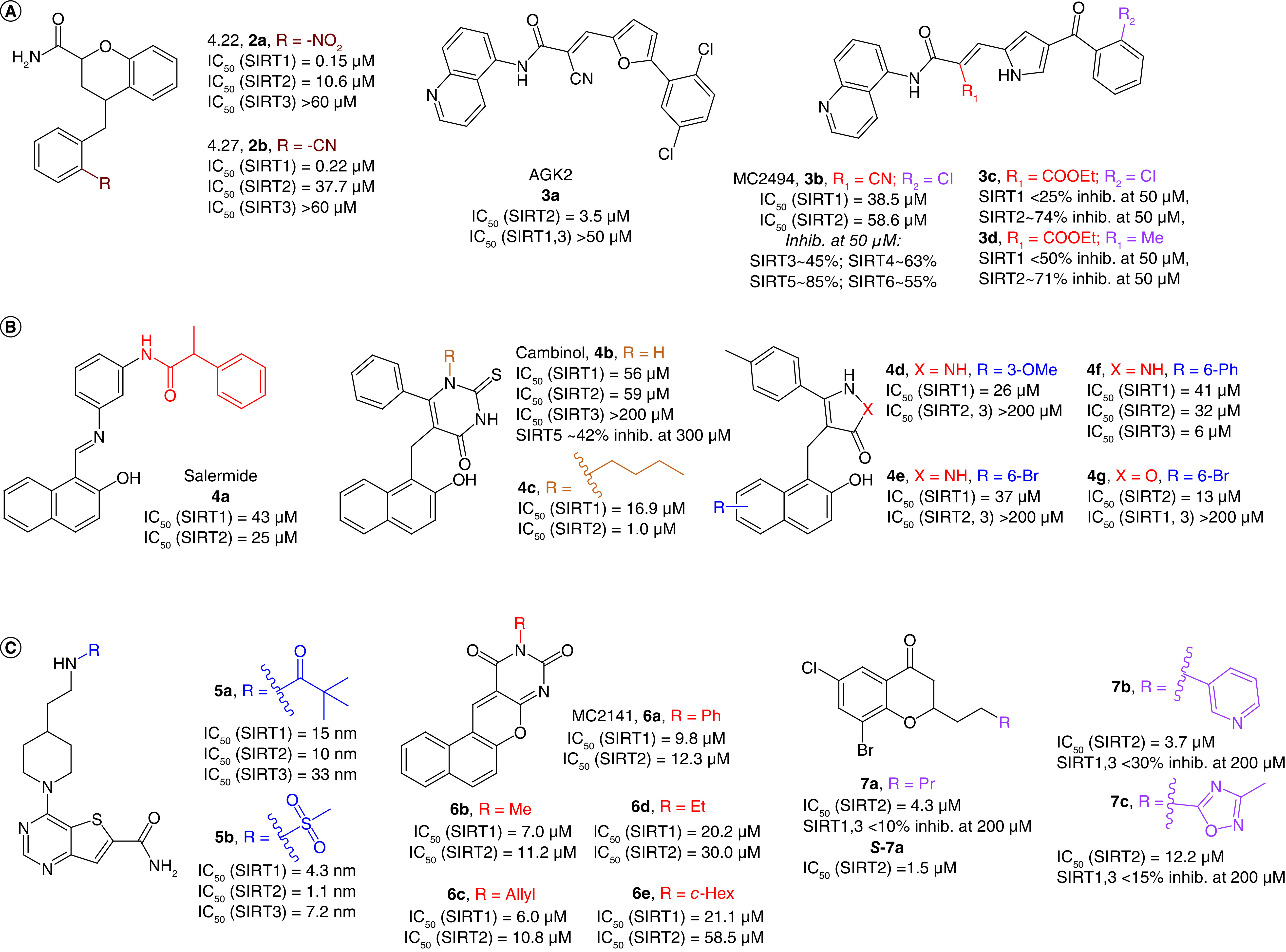

Figure 3. . Structures and enzymatic activities of SIRTi of SIRTi 2–7.

(A) SIRTi 2–3. (B) Salermide (4a) and its related compounds (4b–g). (C) SIRTi 5–7.

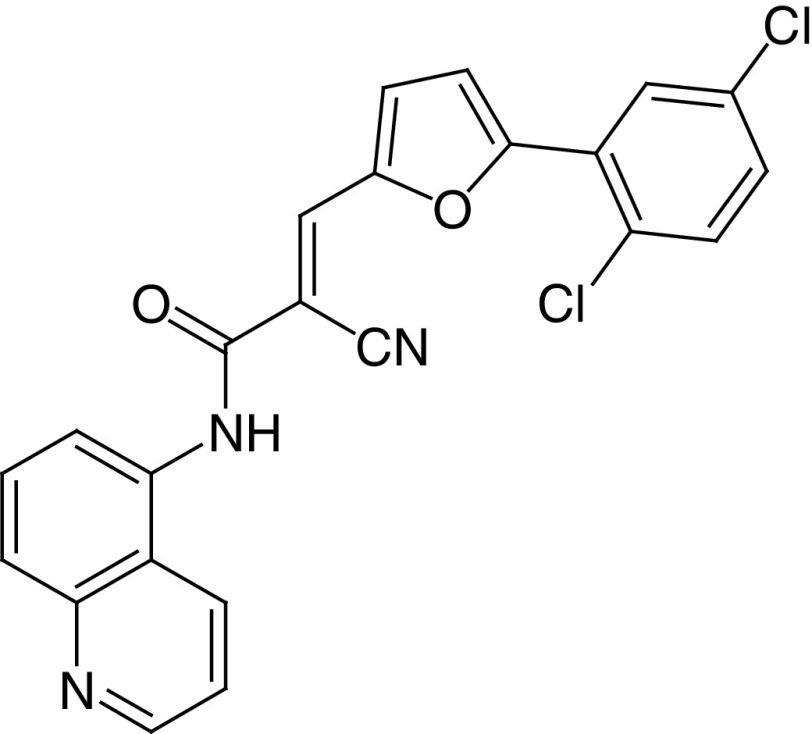

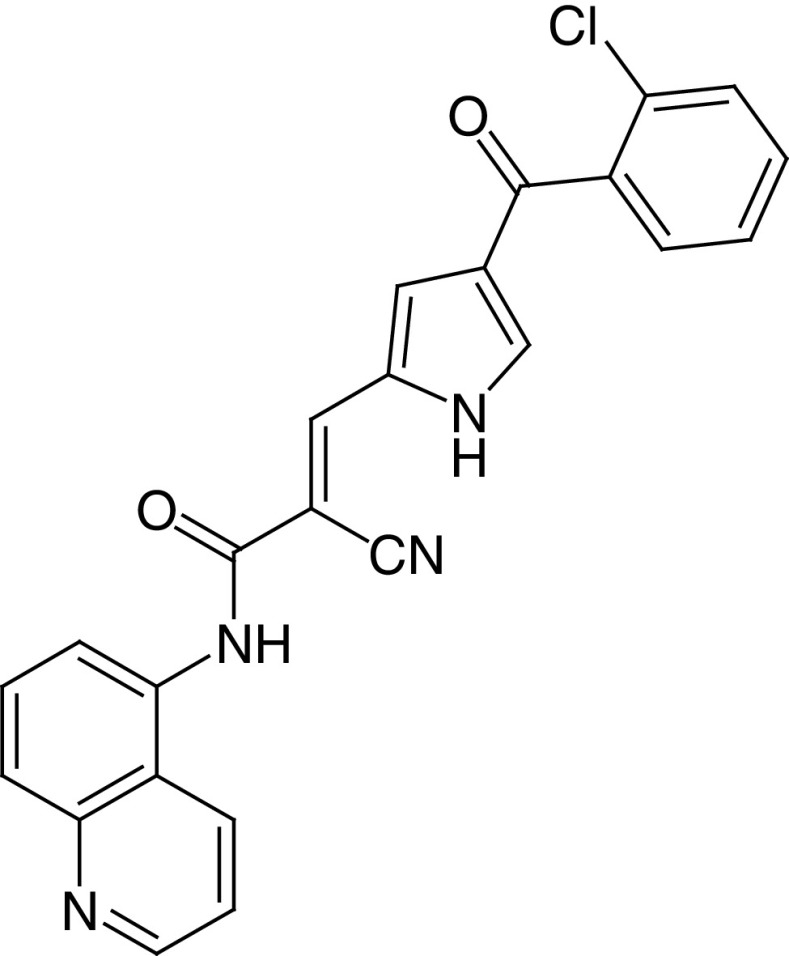

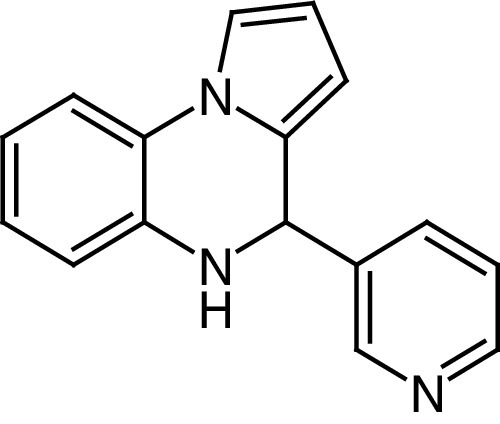

AGK2 (3a, Figure 3A) was reported in 2007 as a single-digit micromolar SIRT2i (IC50 = 3.5 μM), showing selectivity over SIRT1 and SIRT3 (Table 1) [34]. 3a increases α-tubulin acetylation in HeLa cells, and rescues dopaminergic neurons from α-synuclein toxicity, playing a protective role against PD in both cellular and animal models [34]. 3a inspired the design of MC2494 (3b), where the 2,5-dichlorophenyl-substituted furan ring has been replaced by a pyrrole bearing a 2-chlorobenzoyl moiety at the C4 position (Figure 3A). Compound 3b has been reported as a micromolar pan-sirtuin inhibitor (Table 1) [81] endowed with favorable anticancer activity in vitro, in ex vivo leukemic blasts and in vivo in both allograft and xenograft tumor models. Furthermore, 3b increases RIP1 kinase acetylation and stimulates apoptosis via RIP1/caspase-8 [81]. It also possesses cancer-preventive activity in vivo because it counteracts the chemically induced hyperproliferation of mammary gland [81]. 3b also affects mitochondrial homeostasis, as it blocks their biogenesis and functions in terms of metabolism and ATP production [82]. This suggests that 3b could be involved in the regulation of cell response to metabolic stress, leading to propose the mitochondrial damage as a possible mechanism to stop tumor growth by interfering with cancer promotion and progression [82]. Nonetheless, pan-SIRT inhibitors may be dangerous given the key functions played by some sirtuins – for instance, in the context of metabolism regulation and tumor suppression (e.g., SIRT1, 6). Compounds 3c and 3d were obtained through a ligand-based optimization of 3b by replacing the α-cyano group with a carbethoxy moiety [93], with 3d bearing a methyl group instead of Cl at the ortho position of the benzoyl portion (Figure 3A). Both molecules show lower potency against SIRT1 compared with 3d, whereas they are more potent against SIRT2, as confirmed by the marked increase in acetyl α-tubulin levels in leukemia U937 cells and the absence of effect on the acetylation status of the SIRT1 substrates H3K9 and H3K14. Little difference between 3b and its derivatives was observed in terms of cancer cell death induction. However, the data indicate that the replacement of the cyano with a carbethoxy group provides a significant increase in SIRT2 selectivity [93].

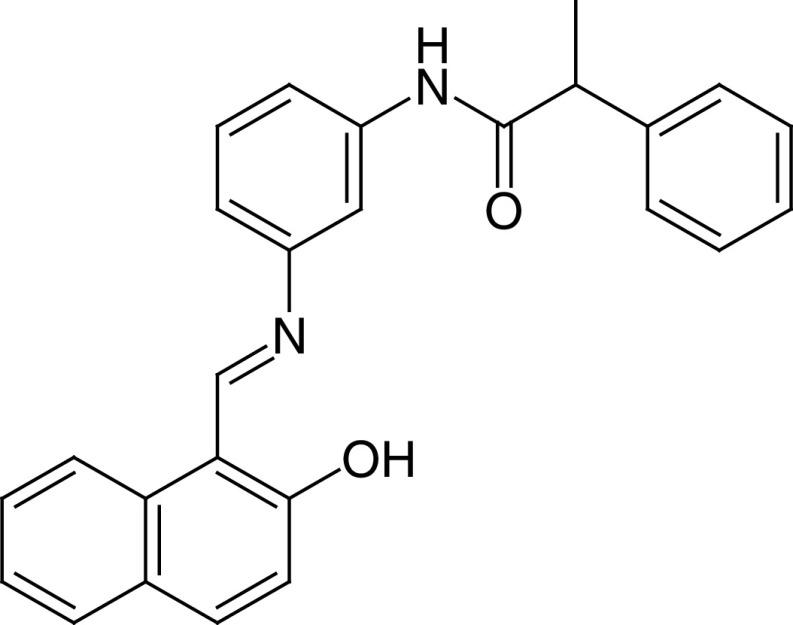

Salermide (4a, Figure 3B) is an analogue of the 2-hydroxynaphthalene derivative sirtinol, initially identified as SIRT1/2 inhibitor. 4a inhibits SIRT1/2 in the mid-micromolar range (IC50 [SIRT1] = 42.8 μM; IC50 [SIRT2] = 25.0 μM, used as racemate) and promotes tumor-specific cell death in many human cancer cell lines, including CRC and glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cancer stem cells (CSCs) [83]. 4a induces p53-dependent cancer-selective apoptosis through the reactivation of proapoptotic genes that are epigenetically repressed by SIRT1 in cancer cells [83,84]. 4a can also rescue the toxicity of mutant Polyadenylate-binding protein nuclear 1 (PABPN1) in a Caenorhabditis elegans model of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy (Table 1) [85].

In 2006, Heltweg et al. identified cambinol (4b), another 2-hydroxynaphthalene derivative with mid-micromolar SIRT1/2 inhibition (IC50[SIRT1] = 56 μM, IC50[SIRT2] = 59 μM; Figure 3B) [94]. 4b promotes hyperacetylation of many SIRT1, 2 substrates, including p53 and α-tubulin, respectively. Moreover, 4b-mediated SIRT1 inhibition makes cells more sensitive to DNA-damaging agents in a p53-dependent way. 4b is the first SIRTi exhibiting antitumoral effects in a Burkitt lymphoma xenograft mouse model [94]. The addition of a n-butyl chain at the N1 position of the 2-thiouracil moiety of 4b led to 4c, showing preferential inhibition for SIRT2 (IC50 = 1.0 μM) over SIRT1 (IC50 = 16.9 μM) [95]. Replacement of the 2-thiouracil of 4b with a pyrazolone ring increases selectivity towards SIRT1 (4d,e) [96], whereas insertion of a phenyl ring at the C6 of the 2-hydroxynaphthalene (4f) or replacement of the pyrazolone with an isoxazol-5-one ring (4g) shifts the selectivity toward SIRT3 and SIRT2, respectively (Figure 3B) [96].

The thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidine-6-carboxamides 5a,b are nanomolar SIRT1–3 inhibitors with 5a (IC50 [SIRT1] = 15 nm; IC50 [SIRT2] = 10 nm; IC50 [SIRT3] = 33 nm), bearing a pivalamide on the sidechain, being slightly less potent than 5b (IC50 [SIRT1] = 4.3 nm; IC50 [SIRT2] = 1.1 nm; IC50 [SIRT3] = 7.2 nm), where the pivalamide is replaced by a methanesulfonamide (Figure 3B) [71]. Co-crystal structures of 5a and 5b bound to SIRT3 indicate that the molecules bind in the catalytic pocket between the Rossman fold and zinc binding domains. Specifically, the carboxamide is inserted into the C-pocket while the aliphatic portion extends towards the substrate binding pocket. Despite the potent in vitro activity, no biological data for these inhibitors have been reported as yet [71].

MC2141 (6a, Figure 3B) is the prototype of a class of benzodeazaoxaflavins inhibiting SIRT1/2 in the low micromolar range (IC50 [SIRT1] = 9.8 μM; IC50 [SIRT2] = 12.3 μM), although their activity has not been assessed against other SIRT isoforms. The replacement of the phenyl moiety at the N10 of the tetracyclic scaffold with a methyl (6b) or allyl (6c) group slightly increases the activity towards both enzymes. Conversely, substitution with an ethyl (6d) or cyclohexyl (6e) group reduces the inhibitory potency. Notably, these molecules show good pro-apoptotic properties in U937 lymphoma cell lines and 6a,c also display growth inhibition of GBM and CRC CSCs in the low micromolar range, while 6b and 6d are less efficient. This suggests that an unsaturated substituent on N10 may be beneficial for cell permeability [97–99].

The chroman-4-one derivative 7a (Figure 3B) is a low-micromolar SIRT2i, selective over SIRT1 and SIRT3 [100] which exhibited an IC50 of 4.3 μM as a racemate, with the S-enantiomer (S-7a) being the eutomer (IC50 = 1.5 μM). As the presence of a carbonyl group was crucial for SIRT2 inhibition and electron-withdrawing substituents at the 6- and 8-positions were favorable for the activity [100], these were kept in derivatives 7b,c (Figure 3B), which also behaved as selective SIRT2i (IC50[7b] = 3.7 μM and IC50[7c] = 12.2 μM, tested as racemate) [101]. Both 7b and 7c showed antiproliferative effects in lung carcinoma (A549) and breast cancer (MCF-7) cells that correlated well with their SIRT2 inhibitory potency and induced dose-dependent α-tubulin hyperacetylation in MCF-7 cells [101].

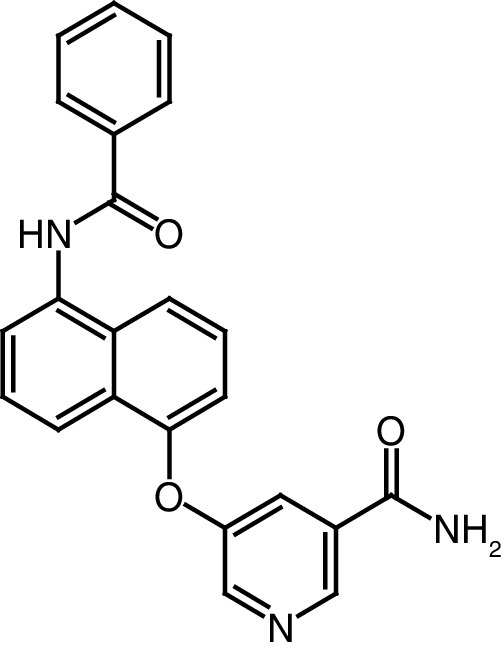

Nicotinamide is a product of the deacylation reactions catalyzed by SIRTs and is an endogenous inhibitor of all SIRT isoforms. On the basis of its structure, Cui et al. developed a series of derivatives through a fragment-based approach (Figure 4A) [86]. Among them, 8a selectively inhibited SIRT2 (IC50 = 0.048 μM) over SIRT1 and SIRT3 (Table 1), acting as a peptide substrate competitive inhibitor and as NAD+ noncompetitive inhibitor [86]. Furthermore, 8a augmented α-tubulin acetylation level in vitro concentration- and time-dependently, whereas it showed mid-micromolar cytotoxicity against chronic myelogenous leukemia (K562), breast cancer (MCF-7) and prostate cancer (DU145) cells (Table 1) [86]. 8a was the prototype for a molecular simplification approach that led, among others, to the 5-((3-amidobenzyl)oxy)nicotinamides 8b and 8c (Figure 4A) [102]. These derivatives were selective for SIRT2 over SIRT1 and SIRT3, acting as competitive inhibitors of both substrate and NAD+ with submicromolar/nanomolar IC50 values (IC50[8b] = 0.11 μM, IC50[8c] = 0.017 μM). 8c exhibited strong protection against the cytotoxicity induced by α-synuclein aggregation in SH-SY5Y cells along with good blood-brain barrier permeability and metabolic stability, thereby representing a promising lead for the development of PD therapeutics [102].

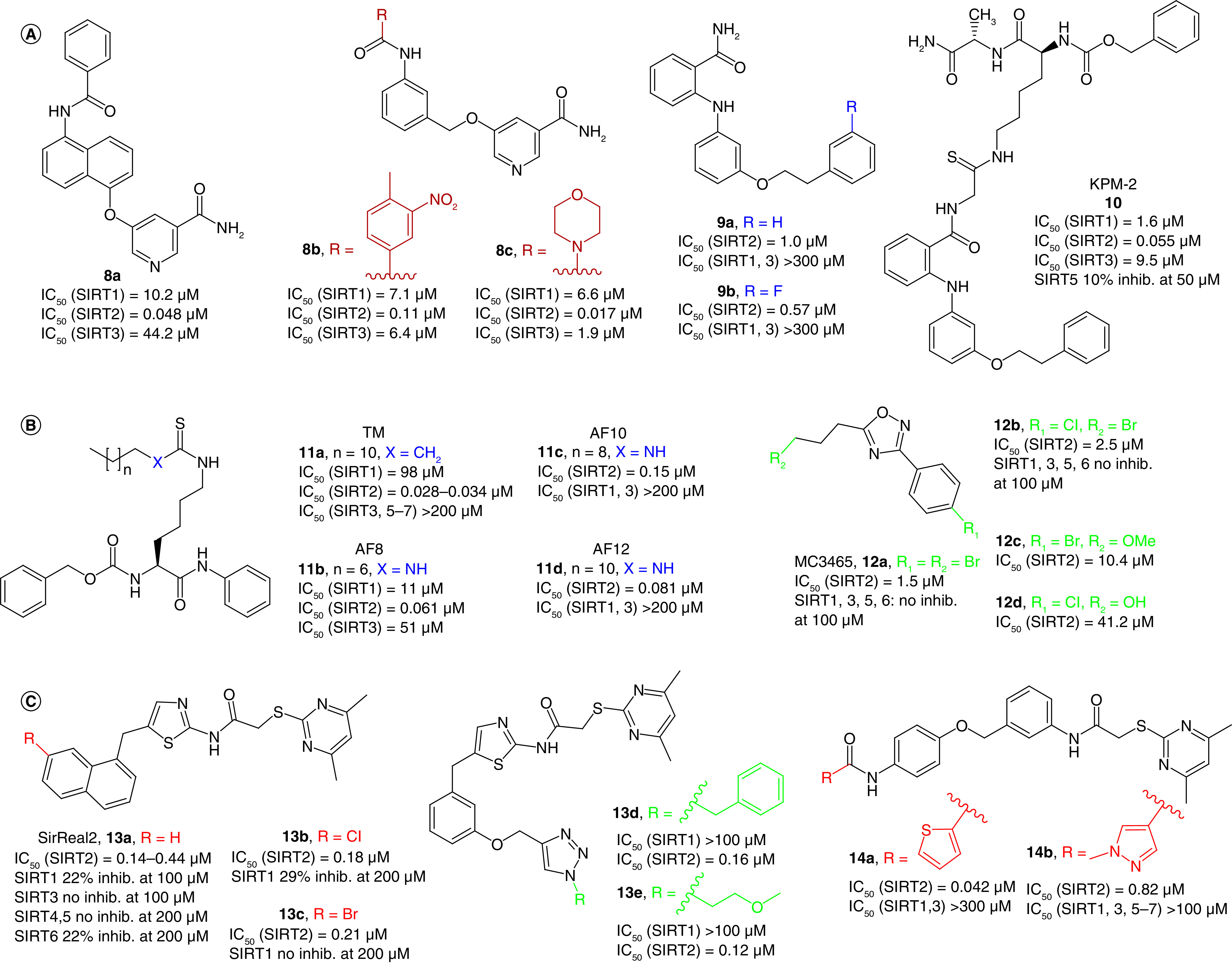

Figure 4. . Structures and enzymatic activities of SIRTi 8–14.

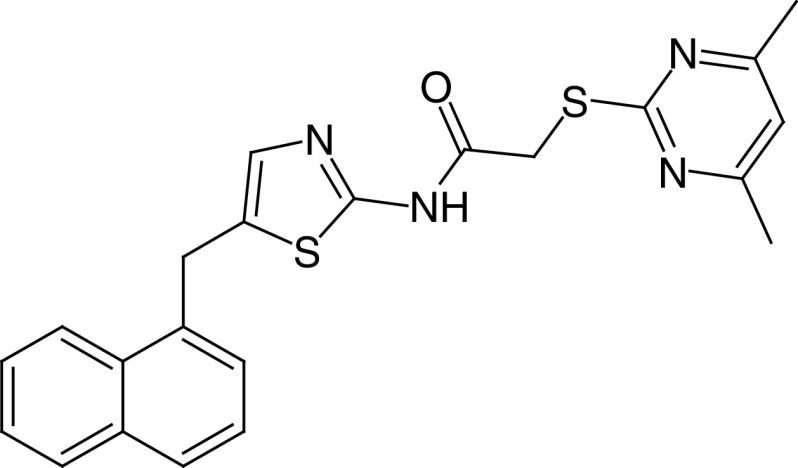

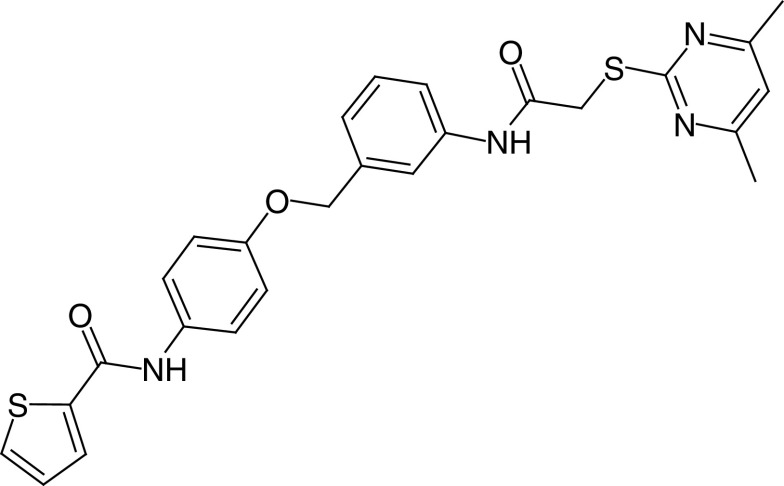

(A) Nicotinamide-based SIRT2-selective derivatives (8–10). (B) The thiomyristoyl lysine derivative TM (11a), its analogues 11b–d and 12a–d. (C) SirReal2 (13a) and its derivatives (13b–e, 14a, 14b).

The 2-anilinobenzamide derivatives 9a and 9b are SIRT2i with IC50 values of 1 and 0.57 μM, respectively, and selective over SIRT1 and SIRT3 [103] (Figure 4A). Compound 9a was also selective over some zinc dependent HDACs (IC50s >30 μM) and only weakly inhibited CYP450s such as 3A4 or 2D6 (IC50s >10 μM). SAR studies suggested that the phenyl group of the phenethoxy side chain is crucial for selectivity, whereas the ethylene linker is essential for the inhibitory potency. Furthermore, 9a increases α-tubulin acetylation levels dose-dependently in colon cancer cells [103]. The SIRT2/9a co-crystal structure indicates that the inhibitor interacts with a hydrophobic pocket at the interface between the Rossmann-fold and a small domain nearby the C-pocket [104]. Specifically, 9a phenethoxyphenyl moiety interacts with Phe131, Leu134, Leu138, Tyr139, Pro140, Phe143 and Ile169 through π-π and H-π contacts, whereas the 2-aminobenzamide portion forms hydrogen bonds with conserved water molecules in the acetyl-lysine tunnel. On the basis of this structure, Mellini et al. designed KPM-2 (10, Figure 4A) as a mechanism-based pseudopeptidic SIRT2i (IC50 = 55 nm) [104]. 10 is a 9a derivative where the benzamide primary amide has been derivatized with a thioacetyl-lysine pseudopeptide, thought to occupy the SIRT2 substrate binding pocket. Notably, the use of thio-acyl substrates to form stalled intermediates is a long-established concept for sirtuins, introduced more than a decade ago by different groups [105,106]. MS-based experiments indicated that the thioacetamide moiety performs a nucleophilic attack toward NAD+ affording a conjugate with ADP and ribose that occupies both substrate and NAD+ binding sites, thus leading to a stalled intermediate. Endowed with 28- and 173-fold SIRT2 selectivity over SIRT1 and SIRT3, 10 showed α-tubulin hyperacetylation and antiproliferative activity in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells with GI50 values of 6.2 and 8.3 μM, respectively. Furthermore, 10 displayed significant neurite outgrowth activity and raised the proportion of differentiated cells compared with control in neuroblastoma N2a cells [104].

TM (11a, Figure 4B) is a thiomyristoyl lysine derivative displaying potent (IC50 = 0.028 μM) and selective SIRT2 inhibition acting as a substrate-competitive mechanism-based inhibitor [87]. Notably, 11a exhibits potent anticancer activity in human breast cancer cells, particularly in c-Myc-driven cancers, and suppresses cancer cell growth in immunocompromised mice models of breast cancer (Table 1). However, its low solubility and synthetic yield prompted the development of new inhibitors endowed with higher solubility and an easier preparation. This led to the thiourea-based compounds AF8 (11b), AF10 (11c) and AF12 (11d), possessing shorter alkyl chains than 11a and endowed with submicromolar IC50 values and SIRT1 and SIRT3 selectivity (Figure 4B) [107]. Moreover, 11b,c show anticancer activity in colon cancer cells, with 11b being also active in a xenograft murine model of colon cancer [107].

Compound 12a is a 1,2,4-oxadiazole-based low micromolar uncompetitive SIRT2-selective inhibitor (IC50 = 1.5 μM, Figure 4B) able to enhance α-tubulin acetylation and possessing antiproliferative and proapoptotic activity in different leukemia cell lines (IC50s = 25–100 μM) [108]. Its analogue 12b, in which Br at C4 is replaced by Cl (Figure 4B), is still SIRT2-selective, but less potent (IC50 = 2.5 μM) and cannot effectively induce apoptosis in the tested cancer cell lines. Interestingly, 12c (IC50 = 10.4 μM), differing from 12a only for the presence of a methoxy group at the phenyl C4, displays improved antiproliferative activity in the same panel of leukemia cell lines (IC50s = 10–62 μM). In an attempt to obtain the co-crystal of SIRT2 bound to 12b and ADP-ribose, Moniot et al. observed that an analogue of 12b with a hydroxyl group instead of the Br at the C5 side chain (12d, Figure 4B) was bound to SIRT2. This is likely a consequence of the hydrolysis of the bromoalkyl chain in the crystallization buffer, probably amplified by the treatments used during crystal soaking. In the SIRT2/12d/ADP-ribose complex, the molecule lies in the acyl channel at the end of SIRT2 active site with its alkyl chain placed in the extended C-pocket and the 4-chlorophenyl moiety positioned in a subcavity of the hydrophobic pocket [108].

SirReal2 (13a, Figure 4C) is a potent SIRT2i (IC50 = 0.14–0.44 μM [19,88]) with minimal effects on SIRT1 and SIRT3–6 (Table 1) [19]. According to the SIRT2/13a co-crystal structure, 13a holds SIRT2 in an open conformation, yielding a ligand-induced conformational change of the active site and interacts with residues situated in a hitherto unknown binding pocket, known as ‘selectivity pocket’, located in the proximity of the zinc-binding domain [19]. In HeLa cells, 13a leads to α-tubulin and microtubules hyperacetylation, without disrupting the cell cycle. Compounds 13b,c, carrying a Cl or Br atom at C7 of the naphthalene ring, respectively (Figure 4C), display SIRT2 IC50 values of 0.18 and 0.21 μM, respectively, and are selective over SIRT1, although they have not been tested against other sirtuins. The inspection of the SIRT2/13c co-crystal structure indicates that 13c adopts a similar binding mode to 13a, mainly driven by hydrophobic interactions. Moreover, 13b can induce α-tubulin hyperacetylation in HeLa cells at lower concentrations compared with 13a. Unfortunately, these halogenated derivatives suffer from poor solubility in aqueous cell culture media; therefore, they can be used only at low concentrations [88]. To improve the SirReal inhibitors, the arylalkyl portion of 13a was elongated to occupy SIRT2 substrate lysine binding channel through a click chemistry methodology that yielded new triazole-based SirReals. Among them, 13d and 13e (Figure 4C), showed improved inhibitory potency against SIRT2 (IC50 values of 0.16 and 0.12 μM, respectively), while keeping the selectivity over SIRT1 and SIRT3. According to x-ray crystallography, 13d has a binding mode similar to 13a, and its triazole moiety forms hydrogen bonds with Arg97 in cosubstrate loop. Both 13d and 13e show higher water solubility and α-tubulin hyperacetylation compared with 13a [109]. Further research from Jung's group led to the exploitation of triazole-SirReal derivatives for the development of different highly potent and selective probes for studying SIRT2 biology, including SirReal-based proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) degraders, chloroalkylated SirReal targeting HaloTag 7 (HT7)-tagged E3 ubiquitin-ligase Parkin, biotinylated and fluorescent SirReal derivatives for biophysical and cellular studies [109–112].

Following a structure-based approach adopting the SIRT2/13a complex structure as template, Yang et al. yielded many derivatives bearing the N-aryl substituted 2-((4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)thio)acetamide moiety of 13a. Among them, 14a was the most potent SIRT2i (IC50 = 0.042 μM), showing significant selectivity over SIRT1 and SIRT3 (Figure 4C) [89]. 14a dose-dependently decreased the viability of breast cancer MCF-7 cells and significantly increased α-tubulin acetylation, whereas no cytotoxicity was detected in the human healthy liver cells HL-7702 [89]. Compound 14b is a 14a analogue in which the thiophene ring has been replaced by a 1-methyl-1H-pyrazole (Figure 4C) displaying lower SIRT2 inhibition (IC50 = 0.82 μM), compensated by higher selectivity over SIRT1 and SIRT3 and 5–7 [113]. The details of SIRT2-14b interactions were elucidated via x-ray crystallography and indicated that 14b induces an enlargement of the hydrophobic pocket and mimics the interactions formed by the myristoyl-lysine substrates within the SIRT2 active site. In H441 non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells, 14b induced dose-dependent α-tubulin hyperacetylation and arrested cell proliferation (IC50 = 3.9 μM), migration and invasion, thus representing a promising starting point for further development.

LC-0296 (15, Figure 5A) is a low-micromolar SIRT3i (IC50 = 3.6 μM) selective over SIRT1, 2 displaying concentration-dependent inhibition of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells (UM-SCC-1 and UM-SCC-17B) proliferation. In the same cells, 15 also promotes apoptosis by increasing reactive oxygen species levels and total mitochondrial acetylation. Specifically, 15 was able to prevent the deacetylation of SIRT3 target proteins such as NDUFA9 and GDH [114].

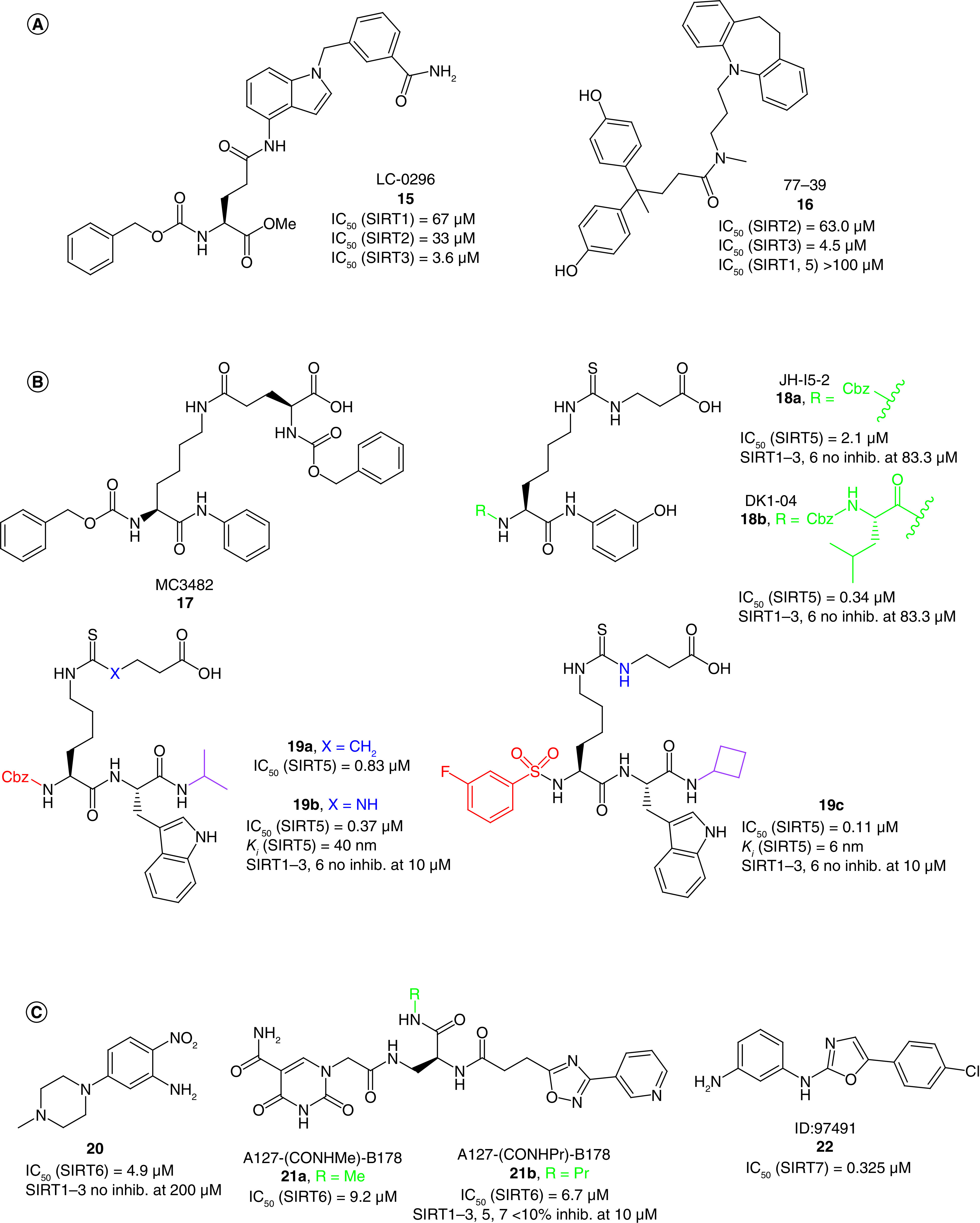

Figure 5. . Structures and enzymatic activities of SIRTi 15-22.

(A) SIRT3i 15 and 16. (B) SIRT5i 17–19. (C) SIRT6i 20–21 and SIRT7i 22.

Recently, through a DNA-encoded chemical library screening, Zhou et al. identified the compound 77–39 (16, Figure 5A) as a SIRT3i (IC50 = 4.5 μM) endowed with selectivity over SIRT1, 2, 5. In line with its SIRT3 inhibitory activity, 16 increased global mitochondrial acetylation without affecting protein expression and determined a reduction in ATP levels in HeLa cells, while showing only little cytotoxicity [90].

In 2015, Polletta et al. reported the Nε-glutaryllysine-based compound MC3482 (17, Figure 5B) as a novel SIRT5i which inhibits SIRT5 desuccinylating activity in both human breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) and mouse myoblasts (C2C12) without affecting its expression. 17 exhibited dose-dependent inhibition of SIRT5-mediated desuccinylation in MDA-MB-231 cells (up to 42% at 50 μM), and displayed selectivity over SIRT1 and SIRT3. In both tested cell lines, 17 raised global protein succinylation, but not acetylation, at 50 μM. Compound 17 also led to enhanced succinylation and consequent activation of glutaminase, thereby increasing cellular ammonia and glutamate levels with the latter triggering autophagy and mitophagy [56]. Consistent with SIRT5 role in modulating the expression of adipogenic transcription factors and mitochondrial respiration, 17 promotes the expression of brown adipocyte and mitochondrial biogenesis markers when administered during the early stages of preadipocyte differentiation [115].

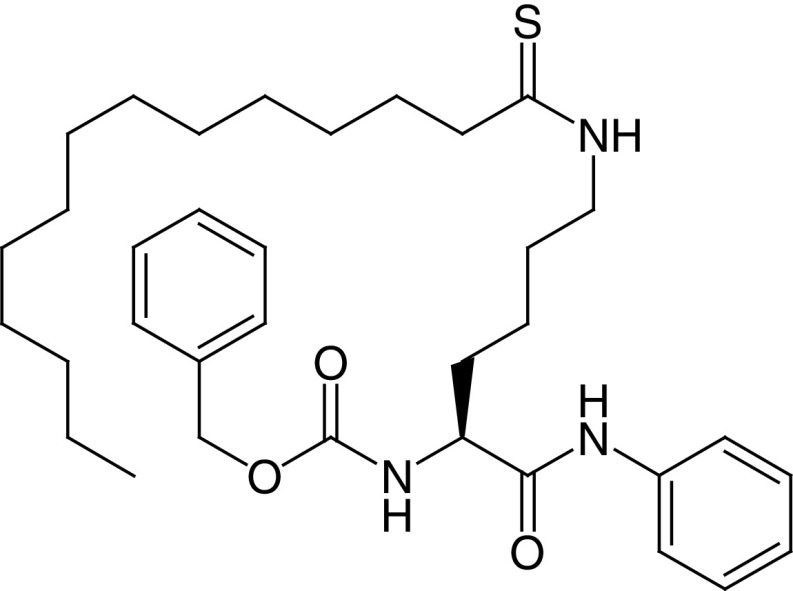

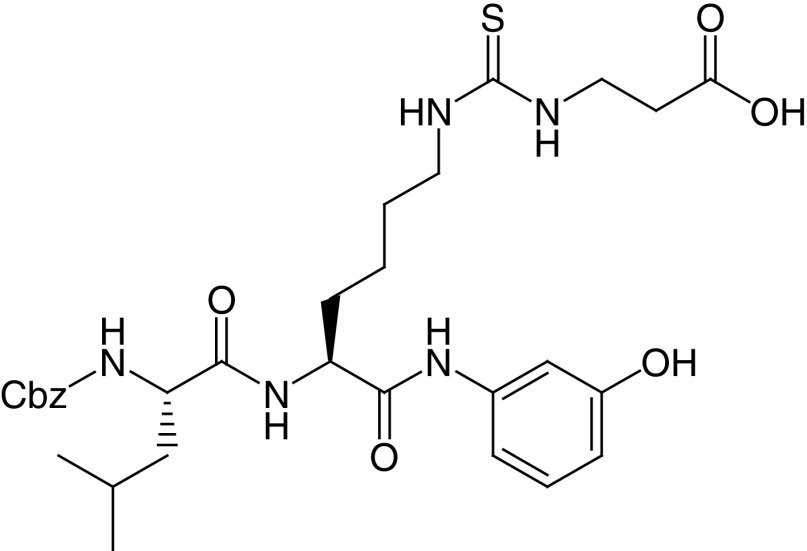

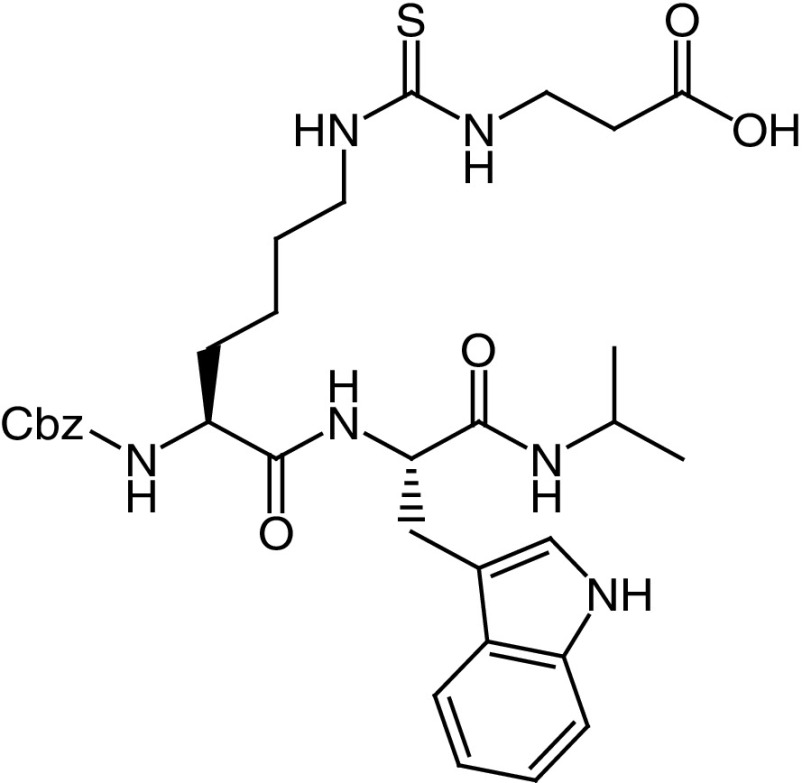

Starting from a SAR study of the previously reported H3K9 thiosuccinylated peptide, Abril et al. gradually shortened the peptide to a N-terminal Cbz-protected thiosuccinyl derivative and then to a thiourea derivative, finally leading to JH-I5–2 (18a), endowed with an IC50 of 2.1 μM against SIRT5-mediated desuccynilation (Figure 5B) [91]. Replacement of the Cbz group of 18a with a Cbz-protected Leu residue led to DK1–04 [18b, IC50(SIRT5) = 0.34 μM] [91]. Both compounds inhibit SIRT5 by forming a covalent 1′-S-alkylamidate stalled intermediate with NAD+ and do not affect SIRT1–3, 6 activity up to 83.3 μM. However, the free carboxylic acid moiety of 18a and 18b impairs their cellular permeability. Hence, the group developed two pro-drug forms, bearing an aceto-methoxy (18a-am and 18b-am) or ethyl ester group (18a-et and 18b-et). All four prodrugs increased global lysine succinylation levels in MCF7 breast cancer cells. The 18b prodrugs were much more effective in suppressing the anchorage-independent growth of MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 breast cancer lines in vitro, with 18b-et being the most potent. In addition, 18b-et significantly inhibited breast cancer growth in vivo, in both genetically engineered and xenotransplant mouse models [91].

In a structure-guided SAR study, Rajabi et al. developed a series of peptidomimetics inhibiting SIRT5-mediated deglutarylation in the submicromolar range and co-crystallized two of these molecules with human and zebrafish SIRT5 [20]. These compounds are Nε-thioglutaryllysine derivatives bearing a carbobenzyloxy (Cbz)-protected N-terminus: 19a (IC50[SIRT5] = 0.83 μM, Ki [SIRT5] = 20 nm) contains a thioamide, whereas 19b (IC50[SIRT5] = 0.37 μM, Ki [SIRT5] = 40 nm) bears a thiourea (Figure 5B). The structures revealed that both molecules form a catalytic intermediate with ADP-ribose and showed that the glutaryl carboxylate moiety engages in important hydrogen bonds, whereas the Cbz group lacks specific interactions, suggesting that different moieties may be inserted to increase the binding affinity. This led to the development of further derivatives, among which the thiourea-based compound bearing a 3-fluorobenzenesulfonamide at the N-terminus 19c is the most potent (IC50[SIRT5] = 0.11 μM, Ki [SIRT5] = 6 nM). Compounds 19b and 19c displayed great selectivity over SIRT1–3 and 6, whereas 19a was not tested against other SIRT isoforms [20]. However, these compounds form a covalent stalled intermediate, and thus the use of IC50 values, based on equilibrium measurements, as the only indication of potency may be misleading; they cannot be compared with reversible inhibitors. Differently, the Ki values, obtained from continuous flow experiments, enabled a kinetic analysis of these molecules, indicating slow, tight-binding kinetics and provide a more accurate potency estimate. After this study, 19b and 19c were further assessed in AML cells as ethyl ester prodrugs (19b-et and 19c-et, respectively) to mask the negative charge of the carboxylic group. Both compounds impaired cell proliferation and induced apoptosis only in SIRT5-dependent cells (OCI-AML2 and SKM-1), but not in SIRT5-independent cells (KG1a and Marimo). Notably, 19b-et was the most potent molecule, exhibiting IC50 values of 5–8 μM, while 19c-et displayed IC50 values of 10–20 μM. In line with this, 19b-et induced more than 80% apoptosis at 5 μM (SKM-1) or 10 μM (OCI-AML2), whereas 19c-et led to more than 80% apoptosis only at 20 μM in SKM-1. Moreover, 19b-et resembled the cellular effects induced by SIRT5 knockdown and mice injected with 19b-et pretreated AML samples displayed increased survival compared to controls [58].

5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-2-nitroaniline (20, Figure 5C) is a recently discovered SIRT6i (IC50 = 4.9 μM) selective over SIRT1–3 and HDAC1–11. 20 increased both H3K9 and H3K18 acetylation levels in BxPC-3 cells and augmented the levels of glucose transporter GLUT1 thereby reducing blood glucose content in a mouse model of Type 2 diabetes (Table 1) [116].

In 2019, Yuen et al. through a DNA-encoded library approach identified the carboxamide derivatives A127-(CONHMe)-B178 (21a) and A127-(CONHPr)-B178 (21b; Figure 5C), showing IC50 values against SIRT6-mediated demyristoylation of 9.2 μM, and 6.7 μM, respectively [117]. Notably, compound 21b showed selectivity over all SIRT isoforms, while 21a selectivity was not tested. Docking analysis of 21a indicates that the 5-aminocarbonyluracil moiety interacts with the C-pocket, while the 3-pyridinyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole portion extends to the NAD+ ribose pocket. When tested in human umbilical venous endothelial cells (HUVECs), 21b showed the ability to promote senescence and a dose-dependent increase of TNF-α levels [117].

ID: 97491 (22, Figure 5C) is a recently reported oxazole-based SIRT7i (IC50 = 0.325 μM) [118], although selectivity over other enzymes was not assessed. 22 dose-dependently decreased MES-SA human uterine sarcoma cell proliferation, without causing cytotoxicity. Compound 22 also increased K373/K382 acetylation and S392 phosphorylation of p53, induced the expression of apoptotic proteins Bax and p21, and promoted apoptosis through the caspase pathway. Finally, 22 impaired cancer growth in xenograft mouse models of uterine sarcoma in a dose-dependent manner [118].

A summary of the most relevant SIRTi identified so far is provided in Table 1.

Sirtuin activators

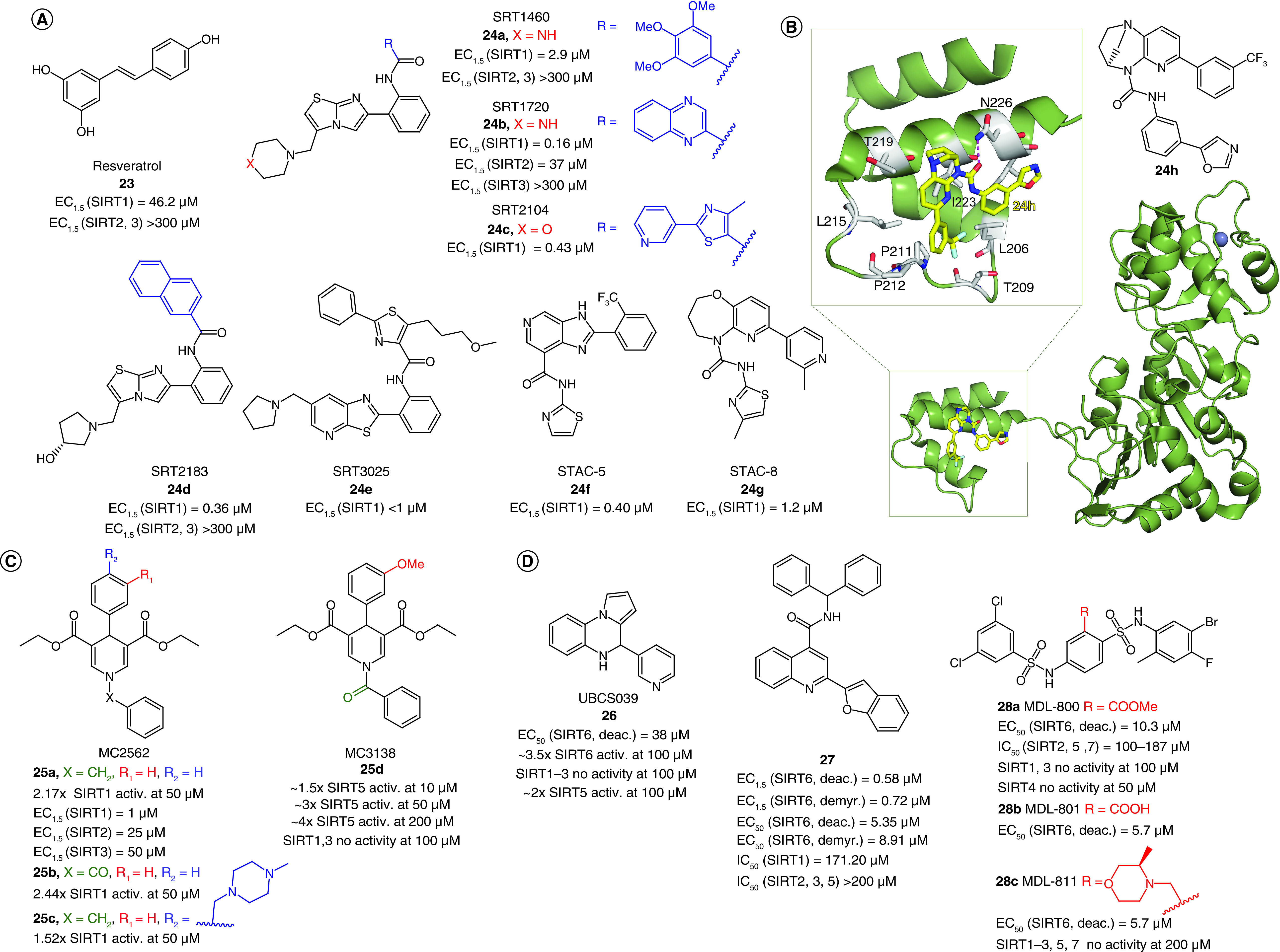

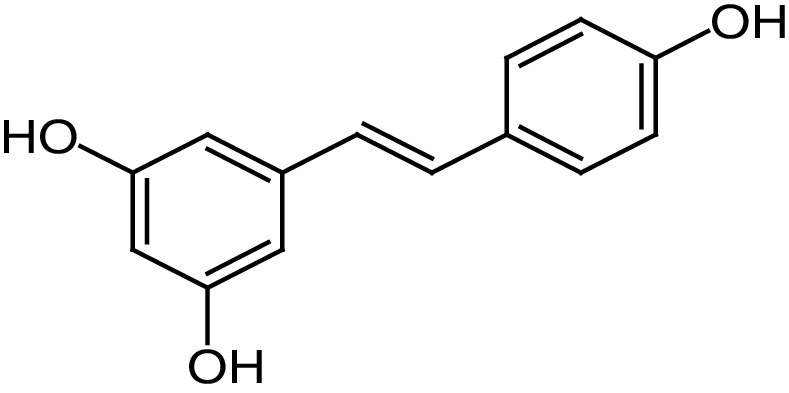

The first SIRT1a reported in literature was the natural compound resveratrol (23), a polyphenolic phytoalexin (Figure 6A) that possesses antioxidant, anti inflammatory, cardioprotective and anticancer properties [119]. 23 is an allosteric activator of SIRT1 able to increase its activity by 50% (EC1.5) at 46.2 μM and to extend the lifespan of many organisms, ranging from yeast to mammals. In mice, 23 was shown to improve mitochondrial functions and lifespan, protecting them against fat diet-induced obesity [120]. More than 70 clinical trials concerning SIRT1 activation by 23 and focused on various disease conditions (e.g., metabolic, cardiovascular and neurological disorders and cancer) have been conducted in the past years, and many are ongoing [121]. In most of the completed trails, 23 showed only neutral effects, confirming the bioavailability issues as a major obstacle. The only trials that led to positive effects were those in which 23 was administered at high doses (≥500 mg/day), with the best results being observed in a phase II trial on patients with Type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease [122]. In this case, treatment with 23 (500 mg/day for 4 weeks) significantly increased high-density lipoprotein levels and insulin sensitivity compared with placebo. Finally, it is important to note that the biological activity of 23 could be related to its multiple and pleiotropic modes of action far beyond SIRT1 activation. Nonetheless, since its identification, 23 has been the starting point for the development of several small molecule sirtuin-activating compounds (STACs).

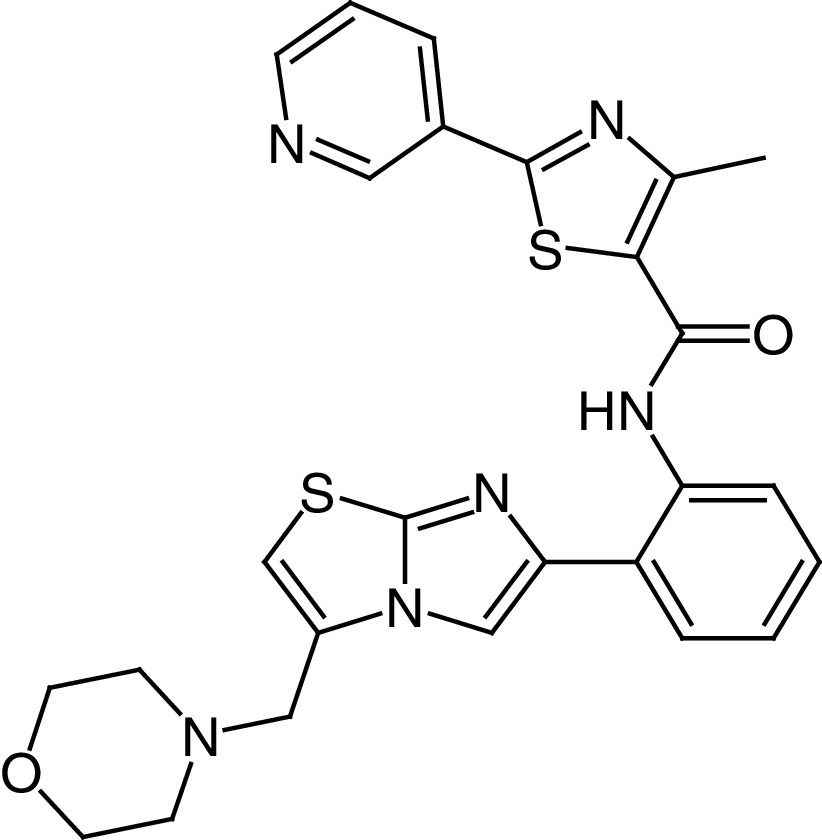

Figure 6. . Sirtuin activators.

(A) Structures and enzymatic activities of SIRT1a 23–24. (B) Structure of STAC 24h and x-ray crystal structure of mini-hSIRT1 in complex with 24h (PDB ID: 4ZZH) [194] with details showing the hydrogen bond with N226 and the hydrophobic interactions with surrounding residues. Mini-hSIRT1 is colored in green with selected residues shown in white sticks, 24h is represented as yellow sticks, the hydrogen bond is represented as a magenta dotted line, Zn2+ is represented as a dark sphere. (C–D) Structures and enzymatic activities of DHP-based SIRTa 25a–d (C) and SIRT6a 26–28 (D).

The most relevant STACs identified so far are SRT1460 (24a, EC1.5 = 2.9 μM), SRT1720 (24b, EC1.5 = 0.16 μM) [123,124], SRT2104 (24c, EC1.5 = 0.43 μM) [125], SRT2183 (24d, EC1.5 = 0.36 μM), and SRT3025 (24e, EC1.5 <1 μM; Figure 6A) [126,127]. All of them are selective SIRT1a more potent than 23 (Figure 6A), increase insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance in genetically and diet-induced obese mice, stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis and regulate lipid metabolism, thus leading to weight loss [123]. Among SRT molecules, 24c is the most studied SIRT1a, and over time it has been evaluated in various clinical trials. Phase I studies focusing on its PK indicated that 24c has poor oral bioavailability [128]. Overall, 24c has been tested in eight clinical trials focused on clinical outcomes, and in five of these it led to neutral or statistically insignificant results [121]. In a phase I trial focused on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and coagulation, treatment with 24c (500 or 2000 mg/day for 28 days) determined anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects [129]. Compound 24c (2000 mg/day for 7 days) was also effective in decreasing cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein levels in elderly volunteers, although variable PK was observed [130]. In a phase II clinical trial carried out in psoriasis patients, treatment with 24c (250, 500 or 1000 mg/day for 84 days) led to promising results in physician global assessment score and histological assessment in 35% of the treated patients, although the PK profile was again highly variable [131]. Compound 24e had also undergone a phase I clinical trial to assess its safety and PK properties, but the study was interrupted after the observation of QT interval prolongation, a warning sign of possible fatal proarrhythmia induction in patients [132]. The molecular mechanism of SIRT1 activation by 23 and STACs has been debated for a long time because there were questions as to whether they directly activate SIRT1 [133,134] because some reports indicated that the observed SIRT1 activation was an in vitro artifact related to the use of peptide substrates containing a fluorophore necessary for the assay [135]. Following studies indicated that the fluorescent moieties on the substrates were dispensable for activation and demonstrated that both 23 and STACs physically interact with SIRT1 [136]. Furthermore, native peptide substrates such as PGC-1α and FOXO3a were shown to facilitate SIRT1 activation mediated by 23, 24a, STAC-5 (24f, EC1.5 = 0.40 μM) and STAC-8 (24g, EC1.5 = 1.2 μM) [137]. These substrates contain hydrophobic residues at the same positions as the fluorophores in the first assays [119,123]. Further reports indicated that the activation is substrate-dependent [138], thus explaining the discrepancies among different studies [133,134]. Recently, Dai et al. determined the co-crystal structure of a 24g analogue possessing the same urea-bridged core (24h, Figure 6B) with an engineered human SIRT1 (mini-hSIRT1), along with two more structures: one in the presence of 24h (Figure 6B) and a substrate inhibitor, and one consisting of a quaternary complex in the presence of acetylated peptide substrate derived from p53 (Ac-p53), and the nonhydrolyzable NAD+ analog carbaNAD+ [139]. These structures, coupled to hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS), reveal that STACs do activate SIRT1 allosterically. In particular, 24h was shown to bind to a shallow hydrophobic pocket at the N-terminus called STAC-binding domain (SBD) for which no endogenous ligand has been identified yet. 24h forms many hydrophobic interactions (with Leu206, Tyr209, Pro211, Pro212, Leu215, Tyr219 and Ile223) and a hydrogen bond with Asn226 (Figure 6B) [139], in line with the observed SAR, indicating the requirement for STACs to possess a flat scaffold maintained by an intramolecular hydrogen bond [124].

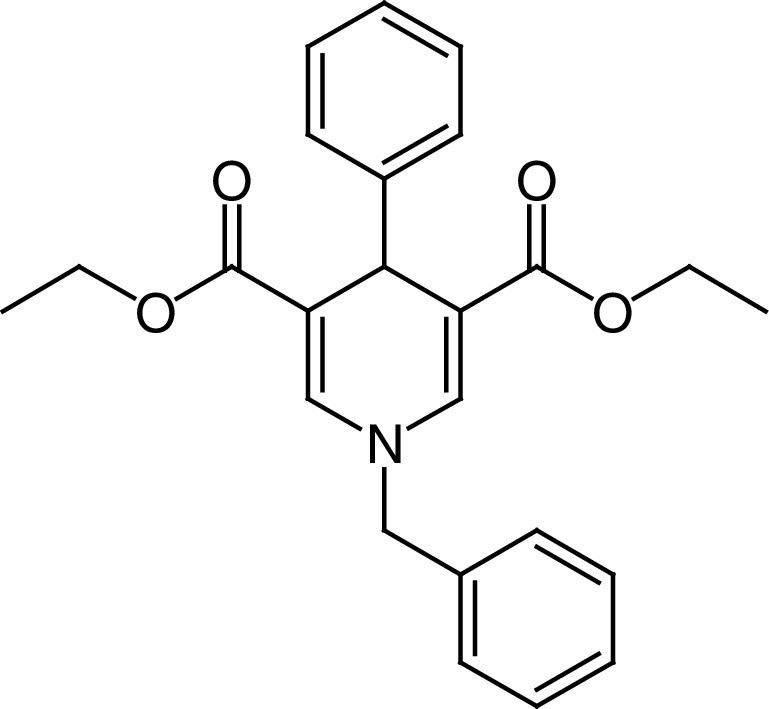

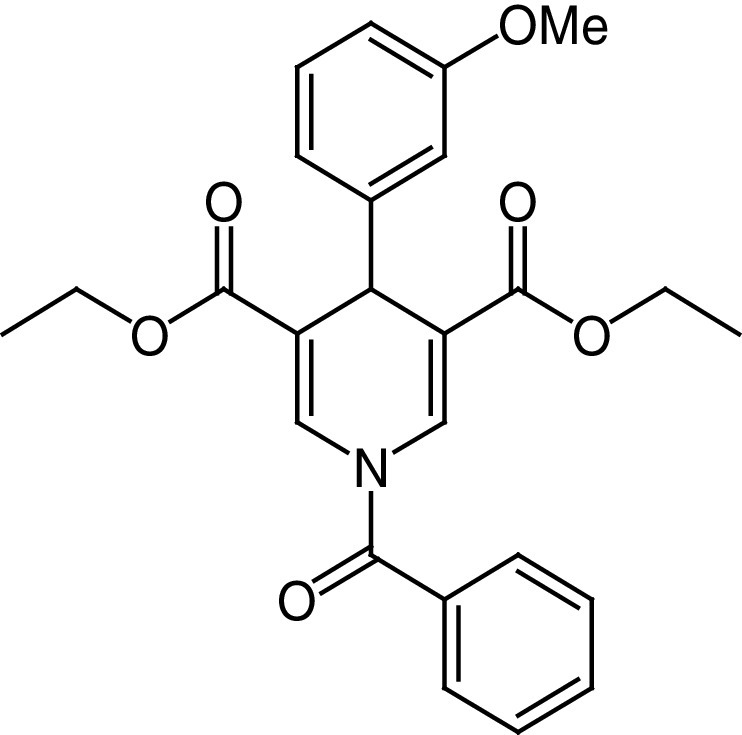

MC2562 (25a, Figure 6C) is the first example of a new class of 1,4-dihydropyridines (DHPs) reported as SIRTa with a preference for SIRT1 (EC1.5 ≃1 μM) over SIRT2 (EC1.5 ≃ 25 μM) and SIRT3 (EC1.5 ≃ 50 μM) [140,141]. 25a and its derivatives were shown to enhance wound healing in mouse models, induce NO release in HaCat cells and decrease α-tubulin acetylation in U937 cells and H4K16 acetylation level in a wide range of cancer cell lines (Table 2) [141]. 25b, in which the N1 benzyl moiety is replaced with a benzoyl group, increased SIRT1 activity 2.44-fold at 50 μM, slightly higher than 25a (2.17-fold SIRT1 activation at 50 μM) and displayed antiproliferative effects only in the CRC cell line LoVo (IC50 = 22 μM). Compound 25c, the water soluble form of 25a, bearing a 4-(4-methylpiperazyn-1-yl)methylphenyl dihydrochloride group in place of the phenyl moiety, showed 1.52-fold SIRT1 activation at 50 μM and antiproliferative activity with IC50 values in the range of 8–35 μM in a wide subset of cancer cell lines [141].

Table 2. . Most relevant sirtuin activators.

| Compound | Structure | Effects on sirtuin activity | Cellular and in vivo effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

23 Resveratrol |

|

EC1.5 (SIRT1) = 46.2 μM EC1.5 (SIRT2, 3) >300 μM |

– Increase of mitochondrial function and lifespan of mouse models, protecting them against fat diet-induced obesity. – Increase of HDL levels and insulin sensitivity in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease in a phase II clinical trial. |

[120–122] |

|

24c SRT2104 |

|

EC1.50 (SIRT1) = 0.43 μM | – Increases insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance in genetically and diet-induced obese mice, along with mitochondrial biogenesis induction, and regulation of lipid metabolism, finally leading to a weight loss. – Antiinflammatory and anticoagulant effects in patients with a lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in a phase I clinical trial. – Reduced cholesterol and LDL levels in elderly volunteers. – Promising results in physician global assessment and histological evaluation in 35% of patients affected by psoriasis in a phase II clinical trial. |

[118,123,126,129–131] |

|

25a MC2562 |

|

EC1.5 (SIRT1) = 1 μM EC1.5 (SIRT2) = 25 μM EC1.5 (SIRT3) = 50 μM |

– Improvement of wound repair in a mouse model of wound healing. – Induction of nitric oxide release in HaCat cells. – Decreased acetylation levels of α-tubulin in U937 cells and of H4K16 in a wide panel of cancer cell lines. |

[141] |

|

25d MC3138 |

|

Effect on SIRT5 deacetylase activity: ∼1.5× SIRT5 activity at 10 μM ∼3× SIRT5 activity at 50 μM ∼4× SIRT5 activity at 200 μM SIRT1, 3 no activity at 100 μM |

– Decreased acetylation of the cytosolic aspartate aminotransferase GOT1, a substrate of SIRT5 in PDAC cells lines. – Impaired PDAC cell viability, with IC50 values in the 25–237 μM range for different cell lines. – Synergistic effect with gemcitabine in PDAC cells and in vivo. Gemcitabine-25d combination was well tolerated and significantly decreased tumor size, weight and proliferation in mice. |

[142] |

|

26 UBCS039 |

|

EC50 (SIRT6, deacetylation) = 38 μM 3.5× SIRT6 activity at 100 μM SIRT1–3 no activity at 100 μM ∼2× SIRT5 activity at 100 μM |

– Activation of SIRT6 in NSCLC, fibrosarcoma, colon and epithelial cervix carcinoma. – Decrease of H3K9 and H3K56 acetylation and autophagy-related cell death. |

[143] |

| 27 |

|

EC1.5 (SIRT6, deacetylation) = 0.58 μM EC1.5 (SIRT6, demyristoylation) = 0.72 μM EC50 (SIRT6, deacetylation) = 5.35 μM EC50 (SIRT6, demyristoylation) = 8.91 μM IC50 (SIRT1) = 171 μM IC50 (SIRT2, 3, 5) >200 μM |

– Cell cycle arrest, inhibition of proliferation (IC50 = 4.1–9.7 μM) and migration in PDAC cells. – Antitumor activity in a human pancreatic tumor xenograft mouse model associated with decrease of H3K9 acetylation. |

[144] |

|

28a MDL-800 |

|

EC50 (SIRT6, deacetylation) = 10.3 μM ×22 SIRT6 activation at 100 μM IC50 (SIRT2, 5, 7) = 100–187 μM SIRT1, 3 no activity at 100 μM SIRT4 no activity at 50 μM |

– Dose-dependent reduction of H3K9Ac and H3K56Ac in HCC and NSCLC, leading to cell cycle arrest. – HCC tumor growth suppression in mouse xenograft models. |

[145,146] |

|

28c MDL-811 |

|

EC50 (SIRT6, deacetylation) = 5.7 μM SIRT1–3, 5, 7 no activity at 200 μM |

– Dose-dependent reduction of H3K9Ac, H3K18Ac and H3K56Ac levels in CRC cell lines. – CRC antiproliferative effect associated with G0/G1 cell cycle arrest (IC50 = 4.7–61.0 μM). – CRC growth suppression in patient-derived organoids. – Antitumor activity in a patient-derived xenografts and a spontaneous CRC mouse model. – Enhancement of vitamin D3 anticancer activity. |

[147] |

CRC: Colorectal cancer; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; NSCLC: Non-small-cell lung cancer; PDAC: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

MC3138 (25d) is a 25b analogue in which the phenyl ring is substituted in meta with a methoxy group (Figure 6C) [142]. Remarkably, 25d increased SIRT5-mediated deacetylation ∼3-fold at 50 μM, without affecting SIRT1 and SIRT3 at 100 μM (Table 2). 25d could mimic the deacetylation effect caused by SIRT5 overexpression in different PDAC cell lines and decreased the acetylation of the cytosolic aspartate aminotransferase GOT1, a substrate of SIRT5. Notably, 25d impaired PDAC cell viability and showed a synergistic effect when administered with gemcitabine both in vitro and in vivo [142].

The development of SIRT6 activators has been initially stimulated by early studies demonstrating that free fatty acids containing 14–18 carbons act as weak SIRT6 activators [12]. UBCS039 (26) is a pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxaline (Figure 6D) reported as the first synthetic activator of SIRT6 deacetylase activity (EC50 = 38 μM and 3.5-fold maximal activation at 100 μM as racemate). Although 26 is selective over SIRT1–3, it can still activate SIRT5-mediated desuccinylation about 2-fold at 100 μM. The SIRT6/26/ADP-ribose co-crystal structure reveals that 26 binds to the acyl binding channel, a hydrophobic tunnel at the end of the catalytic site where the terminal portion of the long chain of acyl substrates is placed. The benzene moiety of the quinoxaline ring of 26 is solvent exposed and the pyridine nitrogen serves as an important anchoring site via hydrogen bonds with the backbone oxygen of Pro62, a residue of major importance for SIRT6 modulators interaction [21]. 26 also decreased H3K18 acetylation at 100 μM on physiological substrates such as HeLa nucleosomes and full-length histones. Follow-up studies indicated that 26 activates SIRT6 and reduces H3K9 and H3K56 acetylation in many cancer cells, including colon and epithelial cervix carcinomas, NSCLC and fibrosarcoma. Finally, 26 induced autophagic cell death in these cancer cell lines via SIRT6 activation [143].

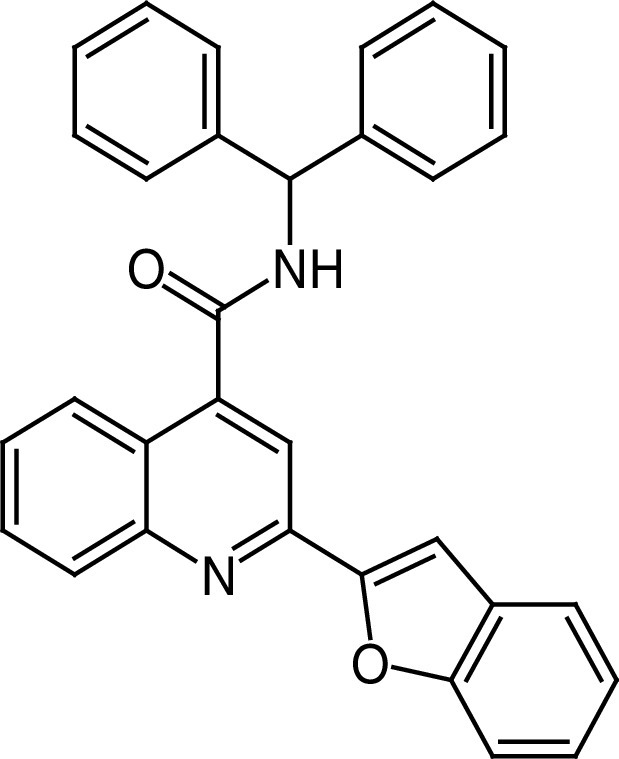

The quinoline-4-carboxamide-based compound 27 (Figure 6D) is a potent and selective SIRT6a obtained from a virtual screening campaign (using the SIRT6/26 complex as a model) followed by structure-guided optimization [144]. 27 selectively activates SIRT6 with EC50 values of 5.35 μM (deacetylation) and 8.91 μM (demyristoylation), and submicromolar EC1.5 values. 27 has no activity against SIRT2, 3, 5, HDAC1–11, and a panel of 415 kinases, while it weakly inhibits SIRT1 (Table 2). Docking experiments suggest that 27 enhances the deacylase activity of SIRT6 via binding toward the end of the acyl binding tunnel. 27 significantly stopped the proliferation and migration of several PDAC cell lines, and cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) executed in intact cells confirmed SIRT6 target engagement. Furthermore, 27 arrested tumor growth in a PDAC xenograft mouse model [144].

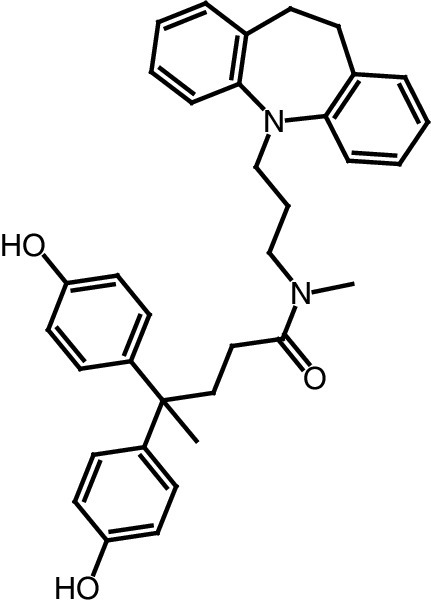

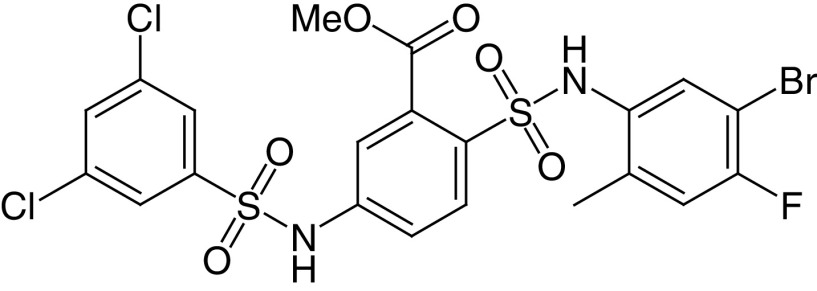

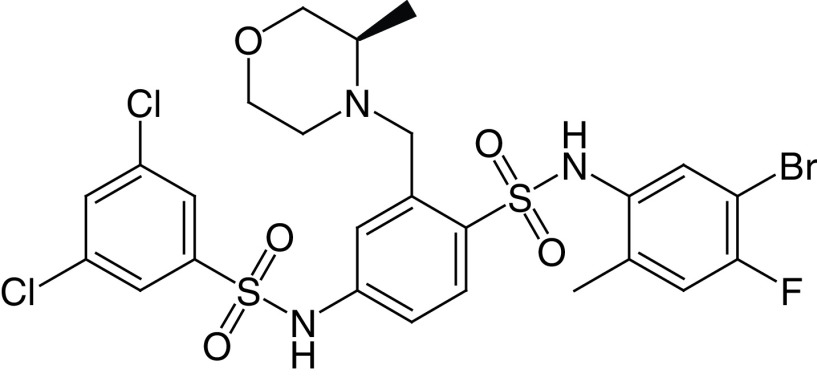

The bis-benzenesulfonamide MDL-800 (28a) and its hydrolysis product MDL-801 (28b) are potent and selective SIRT6a, with EC50 values of 10.3 and 5.7 μM, respectively (Figure 6D) [145]. At 100-μM concentration, both compounds enhance SIRT6 activity by >22-fold and dose-dependently increase the acetylation of nucleosomes. In addition, 28a does not affect the activity of HDAC1–11 and SIRT1, SIRT3 and SIRT4 and displayed minimal inhibition of SIRT2 along with minimal activation of SIRT5 and SIRT7 (Table 2). Because 28b possesses poor cellular permeability and high efflux ratio, it was not tested in cells. Conversely, 28a was able to stop HCC proliferation in cells and in a xenograft mouse cancer model. This effect was coupled with a reduction of H3K9 and H3K56 acetylation in cells and cell cycle arrest. Moreover, 28a inhibited the proliferation of 12 NSCLC cell lines and suppressed tumor growth in an adenocarcinoma xenograft mouse model [146]. According to the co-crystal structure of SIRT6 bound to 28b, ADP-ribose and a myristoylated peptide, the molecule interacts with a surface-exposed area distinct from the acyl binding hydrophobic channel and different from the binding site of 26 [146]. Recently, You and Steegborn reported another SIRT6/ADP-ribose/28b co-crystal structure that indicated that the compound binds inside the acyl binding channel, differently from what was previously reported [148]. In response to this, Huang et al. repeated the crystallization experiment and obtained the same results as in their original publication [149]. Generally, the differences in the binding mode of 28b may be a consequence of the different conditions used for the two crystallization processes. For instance, Huang et al. included H3K9 myristoyl peptide, which was not present in the crystal structure by You and Steegborn. Overall, the two structures may be both valid and represent two conformational states assumed by the protein in the presence of the ligands. In 2020, Shang et al. reported MDL-811 (28c) as a new SIRT6a (EC50 = 5.7 μM), with 2-fold greater activity than 28a [147], showing no activity against HDAC1–11, SIRT1–3, 5, and 7. 28c presents an N-methyl-3-methylmorpholine on C3 of the central benzene, which replaces the methyl carboxylate (Figure 6D) and may be involved in more interactions, thus explaining the improved activity. 28c dose-dependently decreased H3K9, H3K18 and H3K56 acetylation levels in CRC cells and showed antiproliferative effects combined with G0/G1 arrest (Table 2). 28c also inhibited CRC growth in patient-derived organoids (PDOs), in a patient-derived xenograft and in a spontaneous CRC mouse model, also through the enhancement of vitamin D3 anticancer activity [147].

A summary of the most relevant SIRTa is provided in Table 2.

Conclusion

Recent studies have highlighted SIRTs as pivotal modulators of signal transduction pathways given their interactions with nonhistone substrates and their role as epigenetic factors. The pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic disorders and cancer has been correlated with the acylation levels of a wide range of SIRT substrates, with mounting evidence indicating that specific SIRT isoforms need to be downregulated or upregulated to improve the prognosis of specific diseases. This generates an intricate scenery because the same isoform has opposite effects based on tissue localization, stage of the disease, specific microenvironment and external and experimental conditions. Given this situation, isoform-selective sirtuin modulators are particularly important because they ensure specific targeting, paving the way for a more accurate annotation of the biological functions of the single isoforms and, in perspective, for SIRT-targeting personalized therapies.

EX-527 (1a) is one of the first and most promising SIRT1i reported in literature because it has demonstrated a positive safety profile in clinical trials, along with encouraging clinical effects in early HD patients [76]. As for cancer, 1a displayed good results in cell-based experiments [77–80]; however it should be noted that in some cases, the concentrations used in the studies (e.g., 50 μM) could have led to the inhibition of SIRT2, hence the observed effects may not be the consequence of the selective SIRT1 inhibition.

As for SIRT2 inhibition, the release of SirReal2 (13a) [19,88] and the resolution of the structure of the SIRT2-13a complex paved the way for the development of a wide range of inhibitors selectively targeting SIRT2 that have been employed to further clarify SIRT2 biology. Nonetheless, additional target engagement and in vivo studies would be necessary to validate this molecule as a potential therapeutic agent.

For SIRT3–5, the route to the discovery of potent and selective inhibitors is still at its infancy. Indeed, the most potent molecules described to date are peptide-based SIRT5i 18b–c and 19b–c [20,58,91] that exhibit favorable anticancer effects in cells following the esterification of their carboxylic moieties to increase cell permeability. Notwithstanding their great potential as chemical tools, these molecules need to be optimized to decrease their peptide nature. In the case of SIRT6, the most promising molecule identified so far is the low-micromolar SIRT6i 20, which was able to decrease blood glucose levels in a mouse model of diabetes [116]. The simple structure of 20 will allow further ligand-based optimization and the resolution of the SIRT6/20 co-crystal structure would provide the missing information necessary to yield nanomolar SIRT6i. Similar considerations could be valid for the SIRT7i 22, endowed with submicromolar potency against the enzyme, although its selectivity profile still has to be evaluated [118].

As for sirtuin activators, a great deal of work has been carried out in the development of molecules targeting SIRT1. Resveratrol (23) has been evaluated in dozens of clinical trials as a potential SIRT1a, although it mostly exhibited neutral effects and showed some benefits only at high doses because of its extremely low oral bioavailability [120–122]. Moreover, its polyphenolic structure, which is responsible for pleiotropic effects, represents a further issue. In any case, 23 stimulated the development of new SIRTa, leading to the so-called STACs (24a–g). Among them, SRT2104 (24c) [125] showed beneficial effects in phase I and phase II clinical trials [129–131], although its PK properties still represented an issue [128], and the trials were again run using high doses. Importantly, STAC 24h has been co-crystallized with an engineered hSIRT1, thereby providing details on the interactions between SIRT1 and this class of activators [139].

The route to the development of SIRT5a passes through the DHP 25d, which exhibited selective SIRT5 activation accompanied by anticancer activity in both in vitro and in vivo models of PDAC [142]. Finally, compounds 28a–c are low-micromolar SIRT6a, with 28a and 28c also being active in cancer cells and mouse xenograft models [145–147]. The binding mode of 28b sparked some discussion because different groups obtained contrasting results [148,149]. Nonetheless, both models are likely valid given the different conditions used that might have led to distinct conformational states.

Future perspective

Although great progress has been made, the road ahead is long given that only a few SIRT modulators have the potential to be used as chemical probes and there is still an unbalance between the studies on the different SIRT isoforms. Indeed, most research has mainly focused on the development of SIRT1–2 modulators, probably because of the availability of a greater amount of structural, biochemical and biophysical data for these isoforms. In line with this, there is a great shortage of compounds targeting SIRT4 and 7, which are the least investigated isoforms to date. In this context, the release of the structural data for SIRT proteins would provide an important starting point for the development of isoform-selective modulators. To this end, recent advances in cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) [150] could be exploited when x-ray crystallography may not be used.

In the case of sirtuins for which structural data are available, the combination of different chemotypes from molecules with similar modes of action that have been co-crystallized with the target protein, along with scaffold hopping approaches, will likely be crucial in the future development of novel compounds possessing higher potency and selectivity. The integration of structural data with computational approaches and the DNA-encoded libraries coupled to high-throughput assays will enable the faster assessment of huge libraries of molecules and likely lead to a quicker identification of novel isoform-selective chemotypes. In addition, the employment of orthogonal biophysical techniques relying on distinct detection methods (e.g., microscale thermophoresis, surface plasmon resonance and native mass spectrometry) will likely enable the accurate evaluation of the interactions and potency of new modulators and minimize artifacts. The potential therapeutic success of SIRT-targeting modulators will require a more detailed understanding of the SIRT role in specific diseases. Indeed, the current understanding of SIRT biology is still superficial, and it is sometimes difficult to reconcile the different – even contrasting – roles of many SIRTs in various pathologies, particularly cancer. Moreover, the potential candidate drugs need to be improved from a pharmacokinetic point of view and gain nanomolar potency and target selectivity. The combinations of these features will likely yield new potential modulators that will be useful not only as chemical probes for the functional annotation of these fascinating enzymes but also as potential therapeutics for the treatment, alone or in association with other (epi)drugs, of multiple age-related disorders.

Executive summary.

Role of sirtuins in cellular homeostasis

Sirtuins (SIRTs) regulate various cellular processes such as genome maintenance, metabolism, cell cycle progression, apoptosis, reactive oxygen species detoxification and differentiation.

Given their multifaceted roles, the alteration of SIRT activity is linked to various diseases, including cancer, neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disorders and metabolic diseases.

Sirtuin modulators

In the past 2 decades, several inhibitors and activators have been developed, some of them possessing isoform-selectivity and submicromolar potency.

Numerous co-crystal structures elucidated the key interactions between SIRTs and their modulators. The co-crystal structure of SIRT1 bound to the selisistat analogue CHIC-35 (S-1b) and to the activator 24h are shown and discussed.

Some SIRT modulators have been assessed in vivo: MC2494 (3b) and DK1-04 ethyl ester (18b-et) among the inhibitors and MC3138 (25d) among the activators.

Certain SIRT modulators have been evaluated in clinical trials: selisistat (1a) among the inhibitors and resveratrol (23), SRT2104 (24c) and SRT3205 (24d) among the activators.

Overall, SIRT modulators bear great potential for the development of therapeutics targeting aging- and metabolism-related disorders, as well as cancer.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was supported by FISR2019_00374 MeDyCa (A Mai), US National Institutes of Health n. R01GM114306 (A Mai), Progetto di Ateneo ‘Sapienza’ 2017 n. RM11715C7CA6CE53 and Regione Lazio Progetti di Gruppi di Ricerca 2020 – A0375-2020-36597 (D Rotili). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Ho TCS, Chan AHY, Ganesan A. Thirty years of HDAC inhibitors: 2020 insight and hindsight. J. Med. Chem. 63(21), 12460–12484 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiorentino F, Mai A, Rotili D. Lysine acetyltransferase inhibitors from natural sources. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 1243 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mautone N, Zwergel C, Mai A, Rotili D. Sirtuin modulators: where are we now? A review of patents from 2015 to 2019. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 30(6), 389–407 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carafa V, Rotili D, Forgione M et al. Sirtuin functions and modulation: from chemistry to the clinic. Clin. Epigenetics. 8, 61 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fioravanti R, Mautone N, Rovere A et al. Targeting histone acetylation/deacetylation in parasites: an update (2017–2020). Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 57, 65–74 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dang W. The controversial world of sirtuins. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 12, e9–e17 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldman JL, Dittenhafer-Reed KE, Denu JM. Sirtuin catalysis and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 287(51), 42419–42427 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomaselli D, Steegborn C, Mai A, Rotili D. Sirt4: a multifaceted enzyme at the crossroads of mitochondrial metabolism and cancer. Front. Oncol. 10, 474 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiorentino F, Mai A, Rotili D. Emerging therapeutic potential of SIRT6 modulators. J. Med. Chem. 64(14), 9732–9758 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pannek M, Simic Z, Fuszard M et al. Crystal structures of the mitochondrial deacylase Sirtuin 4 reveal isoform-specific acyl recognition and regulation features. Nat. Commun. 8(1), 1513 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson KA, Huynh FK, Fisher-Wellman K et al. SIRT4 is a lysine deacylase that controls leucine metabolism and insulin secretion. Cell Metab. 25(4), 838–855.e815 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman JL, Baeza J, Denu JM. Activation of the protein deacetylase SIRT6 by long-chain fatty acids and widespread deacylation by mammalian sirtuins. J. Biol. Chem. 288(43), 31350–31356 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du J, Zhou Y, Su X et al. Sirt5 is a NAD-dependent protein lysine demalonylase and desuccinylase. Science. 334(6057), 806–809 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • First report demonstrating that SIRT5 possesses lysine demalonylase and desuccinylase activities. The authors combined x-ray crystallography with in vitro and in vivo experiments.

- 14.Kumar S, Lombard DB. Functions of the sirtuin deacylase SIRT5 in normal physiology and pathobiology. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 53(3), 311–334 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schutkowski M, Fischer F, Roessler C, Steegborn C. New assays and approaches for discovery and design of Sirtuin modulators. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 9(2), 183–199 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan M, Peng C, Anderson KA et al. Lysine glutarylation is a protein posttranslational modification regulated by SIRT5. Cell Metab. 19(4), 605–617 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Shi L, Yang S et al. SIRT7 is a histone desuccinylase that functionally links to chromatin compaction and genome stability. Nat. Commun. 7, 12235 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rauh D, Fischer F, Gertz M et al. An acetylome peptide microarray reveals specificities and deacetylation substrates for all human sirtuin isoforms. Nat. Commun. 4(1), 1–10 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rumpf T, Schiedel M, Karaman B et al. Selective Sirt2 inhibition by ligand-induced rearrangement of the active site. Nat. Commun. 6, 6263 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajabi N, Auth M, Troelsen KR et al. Mechanism-based inhibitors of the human sirtuin 5 deacylase: structure-activity relationship, biostructural, and kinetic insight. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56(47), 14836–14841 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.You W, Rotili D, Li TM et al. Structural basis of sirtuin 6 activation by synthetic small molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56(4), 1007–1011 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gai W, Li H, Jiang H et al. Crystal structures of SIRT3 reveal that the alpha2-alpha3 loop and alpha3-helix affect the interaction with long-chain acyl lysine. FEBS Lett. 590(17), 3019–3028 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaziri H, Dessain SK, Eaton EN et al. hSIR2SIRT1 functions as an NAD-dependent p53 deacetylase. Cell. 107(2), 149–159 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vachharajani VT, Liu T, Wang X et al. Sirtuins link inflammation and metabolism. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 1–10 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen HY, Miller C, Bitterman KJ et al. Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 305(5682), 390–392 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Ground-breaking report describing the connection between SIRT1 and aging, through calorie restriction-induced lifespan extension.