Abstract

Dysregulated protein synthesis is a core pathogenic mechanism in Fragile X Syndrome (FX). The mGluR Theory of FX predicts that pathological synaptic changes arise from the excessive translation of mRNAs downstream of mGlu1/5 activation. Here, we use a combination of CA1 pyramidal neuron-specific TRAP-seq and proteomics to identify the overtranslating mRNAs supporting exaggerated mGlu1/5 -induced long-term synaptic depression (mGluR-LTD) in the FX mouse model (Fmr1−/y). Our results identify a significant increase in the translation of ribosomal proteins (RPs) upon mGlu1/5 stimulation that coincides with a reduced translation of long mRNAs encoding synaptic proteins. These changes are mimicked and occluded in Fmr1−/y neurons. Inhibiting RP translation significantly impairs mGluR-LTD and prevents the length-dependent shift in the translating population. Together, these results suggest that pathological changes in FX result from a length-dependent alteration in the translating population that is supported by excessive RP translation.

Subject terms: Autism spectrum disorders, Cellular neuroscience

Dysregulated protein synthesis is key contributor to Fragile X syndrome. Here the authors identify a relationship between ribosome expression and the translation of long mRNAs that contributes to synaptic weakening in a model of Fragile X syndrome.

Introduction

Several genes involved in mRNA translation have been identified as penetrant risk factors for autism1,2. Most prevalent is the FMR1 gene encoding the RNA binding protein Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP)3. In FX, excessive neuronal protein synthesis is a core phenotype that is conserved from fly to humans4–7, and it is believed to be pathological because targeting translation control signaling pathways can correct electrophysiological and behavioral deficits in Fmr1−/y animal models4–6,8–10. FMRP is an RNA binding protein that has been implicated in the repression of translation11,12. A leading mechanistic model proposes that FMRP slows the elongation of target transcripts, resulting in a depression of the translation of these targets in FX neurons3. Recent studies using ribosome profiling and RNA-seq have provided important support for this model, showing that there is a reduction in ribosome pausing along long mRNAs in Fmr1−/y brain13,14. However, the way in which this dysregulation of protein synthesis results in neurological disruptions in FX has not been established. This is due in large part to the lack of information about the mRNAs over-translated in Fmr1−/y brain that are impeding synaptic function.

A key synaptic phenotype in the Fmr1−/y model is an exaggeration of long-term synaptic depression induced by activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR-LTD) in hippocampal CA1, a major form of synaptic plasticity that contributes to learning15,16. This phenotype has been observed in numerous studies of Fmr1−/y mice and rats, and has been used as a model for synaptic dysfunction in FX7,17. Inhibition of protein synthesis specifically in CA1 pyramidal (pyr) neurons blocks mGluR-LTD, showing that de novo translation in these neurons is required for plasticity18. In the Fmr1−/y hippocampus, LTD is not only greater in magnitude, it is also persistent in the presence of protein-synthesis inhibitors that disrupt mGluR-LTD in WT19. Based on these results and others, The mGluR Theory of FX was proposed as a conceptual framework for interpreting how the loss of FMRP-regulated protein synthesis leads to pathological changes in the FX brain16. According to this model, protein synthesis downstream of group 1 mGluRs (mGlu1/5) is unchecked in the absence of FMRP, causing an exaggeration of mGluR-LTD and other mGlu1/5-associated changes. Multiple studies have shown that inhibition of mGlu5, the predominant group 1 mGluR in the forebrain, correct pathological changes in Fmr1−/y models, including excessive protein synthesis, altered dendritic spine function, exaggerated LTD, epileptiform activity, learning deficits, and expression of audiogenic seizures8,20. Identifying the proteins that are both over-synthesized in Fmr1−/y and synthesized in response to mGlu5 activation thus represents a unique opportunity to assess how altered translation in FX neurons disrupts synaptic function. Although there have been important candidate-driven analyses of this question21,22, there has yet to be a comprehensive cell-type-specific analysis of the mRNAs translated in response to LTD, and analysis of the way that these are altered in the Fmr1−/y hippocampus.

In this study, we identified mRNAs both overtranslated in Fmr1−/y and translated in response to mGluR-LTD stimulation in CA1 pyr neurons using a combination of cell-type-specific Translating Ribosome Affinity Purification and RNA-seq (TRAP-seq) and label-free proteomics. Surprisingly, we find that the most commonly overtranslated and overexpressed population in Fmr1−/y neurons is comprised of ribosomal proteins (RPs). Using multiple methodologies, we confirm a significant per-cell increase in the expression of RPs and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) in Fmr1−/y neurons, which has not been previously described. Furthermore, this first translation profiling analysis of mGluR-LTD in FX reveals a similar significant increase in RP translation that is occluded in Fmr1−/y neurons. In fact, the majority of translation changes induced by mGluR-LTD in WT are strikingly similar to those constitutively changed in Fmr1−/y neurons, providing strong support for the mGluR Theory. Interestingly, further analysis shows that the RP translation that is induced by mGluR-LTD and is constitutive in Fmr1−/y neurons alters the translating population in a manner that reduces the translation of longer-length transcripts. This results in a reduction in the expression of proteins involved in synaptic stability encoded by these long transcripts, including FMRP targets. Incubation with the ribogenesis inhibitor CX-5461 prevents the reduced translation of long mRNAs by mGlu1/5 stimulation and impairs mGluR-LTD, directly linking the translation changes observed in CA1 neurons to a hallmark FX phenotype. Together, these results show that the translating mRNA population in Fmr1−/y neurons is comprised of an overabundance of RPs and a paradoxical deficit in long mRNAs encoding synaptic proteins, which mimics the translation downstream of mGlu1/5 activation. This would suggest a reconceptualization of the relationship between excess translation and pathological synaptic changes in FX.

Results

Ribosomal proteins are overtranslated in Fmr1−/y neurons

Identification of the overtranslating mRNAs in FX is essential for understanding how synaptic pathology emerges. In previous work, we investigated ribosome-bound mRNAs in Fmr1−/y hippocampal CA1 pyr neurons using TRAP-seq, which revealed overtranslated mRNAs that compensate for the loss of FMRP23. While this study identified a novel target that can be positively modulated to correct Fmr1−/y phenotypes, it did not reveal an obvious group of targets driving the pathology of FX. To identify this group, we tried a new approach comparing the mistranslating mRNAs identified by TRAP to the synapse-enriched proteome of the Fmr1−/y hippocampus (Fig. 1a). We reasoned that a comparison of the population both overtranslated and overexpressed, in the same hippocampal slice preparation, would more accurately identify contributors to pathological changes.

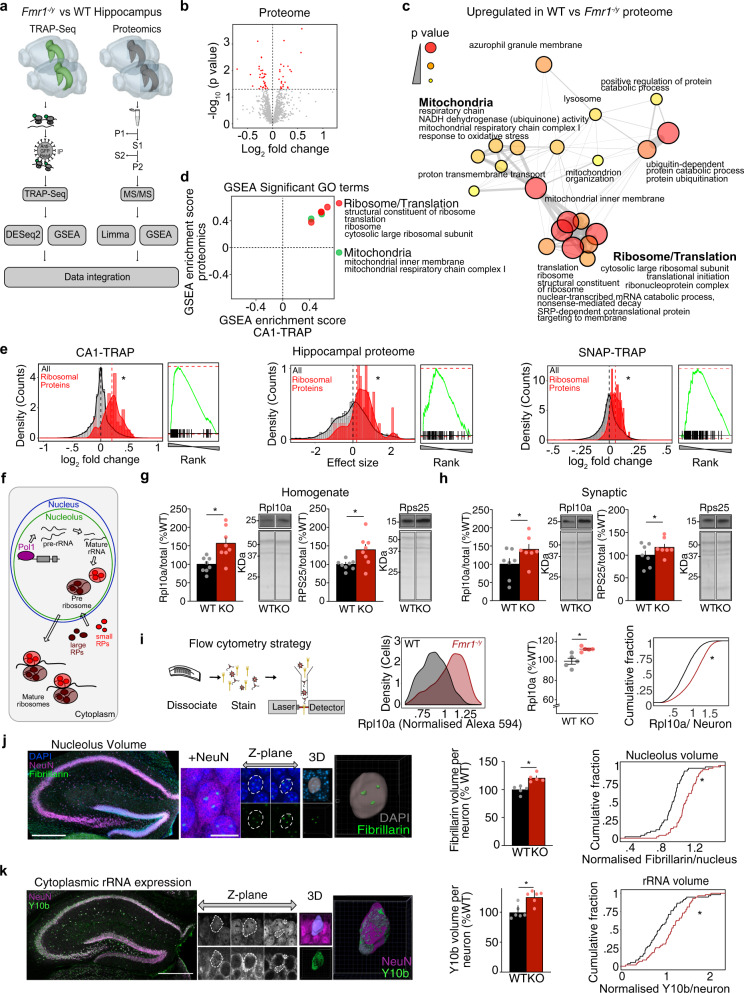

Fig. 1. Ribosomes are overproduced in Fmr1−/y hippocampal neurons.

a Schematic of the experimental strategy. Multi-Omics approach was used to identify overtranslating and overexpressed proteins. b Volcano plot of proteomics analysis of hippocampal P2 fractions isolated from WT/Fmr1−/y littermates. Significant targets (P < 0.05) are denoted in red. c GSEA analysis of the proteomics dataset identified overexpression of ribosome/translation and mitochondrial-related GO terms in the Fmr1−/y (adjusted P value < 0.1). d Overlap of significantly upregulated gene sets identified by GSEA in both TRAP-seq and proteomic datasets reveals ribosome/translation and mitochondrial GO terms as the most enriched in the upregulated populations. e Analysis of the 80 RP population versus total population in Fmr1−/y versus WT CA1-TRAP, proteomic, and SNAP-TRAP datasets reveal a significant upregulation in all three datasets (two-sample z test: z = 6.54, *P = 6.25 × 10−11, z = 2.51, *P = 0.012, z = 5.12, *P = 3.11 × 10−7, CA1-TRAP, P2 proteomic, Snap-TRAP, respectively). f Schematic of ribogenesis showing precursor rRNA transcription in the nucleolus by RNA Pol I, followed by splicing and folding into mature rRNA subunits, RP production, and association with mature ribosomes upon export to the cytoplasm. g Immunoblotting of hippocampal homogenates from Fmr1−/y and WT littermates revealed a significant increase in the large ribosome-associated protein Rpl10a (WT = 100 ± 7.1%, Fmr1−/y= 158.7 ± 15.19%, two-tailed paired t test *P = 0.0008, N = 8 littermate pairs) and the small ribosome-associated protein Rps25 (WT = 100 ± 4.53%, Fmr1−/y = 139.7 ± 14.28%, two-tailed paired t test *P = 0.0468, N = 8 littermate pairs). h Synaptoneurosomes isolated from WT and Fmr1−/y hippocampi show the same increase in Rpl10a (WT = 100 ± 15.44%, Fmr1−/y = 140.4 ± 13.95%, two-tailed paired t test *P = 0.0436, N = 7 littermate pairs) and Rps25 (WT = 100 ± 9.18%, Fmr1−/y = 117.1 ± 7.1%, two-tailed paired t test *P = 0.0235, N = 7 littermate pairs). i Schematic showing steps for FACS immunostaining. Comparison of CA1 neurons isolated from 5 littermate pairs shows a significant increase in Rpl10a expression in Fmr1−/y vs WT (two-tailed paired t test, WT = 100 ± 3.1%, Fmr1−/y = 112.5 ± 1.08%, *P = 0.02915, KS test *P = 2.2e-16). j Sections from Fmr1−/y and WT littermate brains were immunostained for NeuN, fibrillarin and DAPI or NeuN and Y10b before confocal imaging of the dorsal hippocampal CA1 region (scale bar = 10 μm). Total nucleolar volume was quantified from 3D reconstruction of fibrillarin staining. Analysis shows a significant increase in total nucleolar volume per cell in Fmr1−/y vs WT neurons when quantified per animal (two-tailed paired t test, WT = 100 ± 3.277%, Fmr1−/y = 121.2 ± 3.277% *P = 0.032 N = 5 littermate pairs) or as a cumulative distribution of all neurons (KS test *P = 2.93e-07, N = 52 neurons). k Volume of rRNA was quantified from 3D reconstruction of Y10b staining normalized to NeuN. A significant increase in rRNA volume was observed in in Fmr1−/y neurons (two-tailed paired t test, WT = 100 ± 4.458%, Fmr1−/y = 125.4 ± 4.458%, *P = 0.0358, N = 6 littermate pairs, KS test *P = 0.00792, N = 59 neurons). Data are presented as mean values + /− SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To identify proteomic changes, we isolated hippocampal slices from 5 pairs of littermate WT and Fmr1−/y mice of a juvenile age (P25-32), which is consistent with the CA1-TRAP-seq samples isolated from six pairs of juvenile Fmr1−/y and WT hippocampus. Synapse-enriched P2 fractions were isolated from each set of slices. This latter step is regularly used when examining proteomic changes relevant to synaptic function, and it is necessary to isolate the synapse-relevant proteome from the bulk tissue that contains cell bodies from all cell types including glia24,25. Isolated fractions were processed for label-free Mass Spectroscopy (MS) and differential expression was determined as described in Methods. Consistent with previous proteomic studies of Fmr1−/y cortex, we find that the changes in the steady-state proteome of the Fmr1−/y hippocampus are modest, with 52 proteins identified as significantly altered (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Data 1). We therefore further interrogated this dataset using a rank-based Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), which was developed to identify gene sets that shift together26. This analysis revealed that 20 gene sets were significantly upregulated in the Fmr1−/y proteome (Supplementary Data 2). Surprisingly, the most significantly upregulated gene sets were related to ribosomes (Fig. 1c). Next, we performed the same GSEA on the CA1-TRAP dataset collected in our previous study, identifying 14 gene sets significantly upregulated23 (Supplementary Fig. 1a and Supplementary Data 2). Remarkably, a comparison of gene sets significantly upregulated in both proteomic and CA1-TRAP populations again identified ribosomes (Fig. 1d).

To determine whether the GSEA results reflected an actual increase in ribosomes, we began by assessing the 80 distinct ribosomal proteins (RPs) associated with eukaryotic ribosomes27. Although recent work has discovered that ribosomes can exhibit a specialized composition of RPs, the majority of ribosomes are believed to express RPs in a stoichiometric fashion28. We, therefore, analyzed the expression of the 80 RP gene set as a group. These results show a significant upregulation of RPs in both the CA1-TRAP and proteome of Fmr1−/y hippocampus (Fig. 1e). Quantifying the ribosome-bound mRNAs isolated by TRAP can reflect a difference in transcript abundance as well as translation. To determine whether a change in the abundance of RP transcripts could account for the change seen in the TRAP fraction, we normalized the counts obtained from the TRAP samples to those from the total hippocampal transcriptome. Our results show that although there is a significant increase in RP expression in the total Fmr1−/y mRNA population, the increase in the TRAP-bound fraction is greater and persists after normalization to this total (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Although our investigation was largely focused on CA1 pyr neurons due to the pivotal role these cells play in mGluR-LTD, we wondered whether the increase in RP expression could be seen in the broader neuronal population. To determine this, we performed TRAP-seq on hippocampi isolated from four littermate WT and Fmr1−/y pairs expressing EGFP-L10a under the Snap25 promoter, which exhibits pan-neuronal expression throughout postnatal development (Supplementary Fig. 1c, Supplementary Data 3). Similar to our results from CA1, we find RP transcripts are upregulated in the Fmr1−/y SNAP-TRAP fraction (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1d). This shows increased RP translation is expressed in the broader Fmr1−/y neuron population.

Ribosomes are overproduced in Fmr1−/y neurons

Although surprising, a confirmed increase in ribosome production in Fmr1−/y neurons would have important implications for understanding the protein-synthesis dysregulation seen in FX. Ribogenesis is a complex process that involves both transcription of rRNA subunits in the nucleolus, and production of RPs that ultimately assemble into mature ribosomes that are exported into the cytoplasm (Fig. 1f)27. To determine whether the observed increase in RP translation reflected an increase in ribogenesis in Fmr1−/y neurons, we performed multiple validation experiments. First, we performed immunoblotting for RPs associated with both small and large ribosomal subunits and found both the large subunit-associated Rpl10a and small subunit-associated Rps25 are significantly overexpressed in Fmr1−/y versus WT hippocampus (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 1e). The same increase is also seen in synaptoneurosome fractions (Fig. 1h). Next, it was essential to determine whether the increased RP expression could be seen on a per-neuron basis to rule out the possibility that our results are due to a difference in cell size or composition. To assess per-neuron expression, we immunostained dissociated neurons from Fmr1−/y and WT hippocampi for Rpl10a and quantified per-cell expression using flow cytometry (Fig. 1i). Analysis of six littermate pairs reveals a significant increase in the expression of Rpl10a in individual Fmr1−/y neurons. These results provide strong validation of the results seen in our CA1-TRAP and proteomic datasets.

Along with RPs, functional ribosomes require the presence of 4 core rRNA subunits, which are transcribed in the nucleolus, which increases in size during periods of high ribogenesis29. To verify that expression of the rRNA core was elevated in Fmr1−/y versus WT neurons, we first measured nucleolar volume by immunostaining for the nucleolar marker fibrillarin (Fig. 1j). Analysis of reconstructed confocal z-stacks reveals that nucleolar volume is significantly increased in Fmr1−/y neurons measured as either an increase in total nucleolar volume per neuron (Fig. 1j) or as the average volume of nucleoli per neuron (Supplementary Fig. 1f). To confirm that the amount of mature rRNA outside the nucleolus was also increased, we performed immunostaining using a Y10b antibody raised against rRNA30. Calculation of Y10b staining per volume of NeuN shows a significant increase in rRNA expression in Fmr1−/y versus WT hippocampal neurons (Fig. 1k), with no significant difference in the total volume of NeuN (Supplementary Fig. 1f). Together, our results confirm an elevated expression of ribosomes in Fmr1−/y neurons.

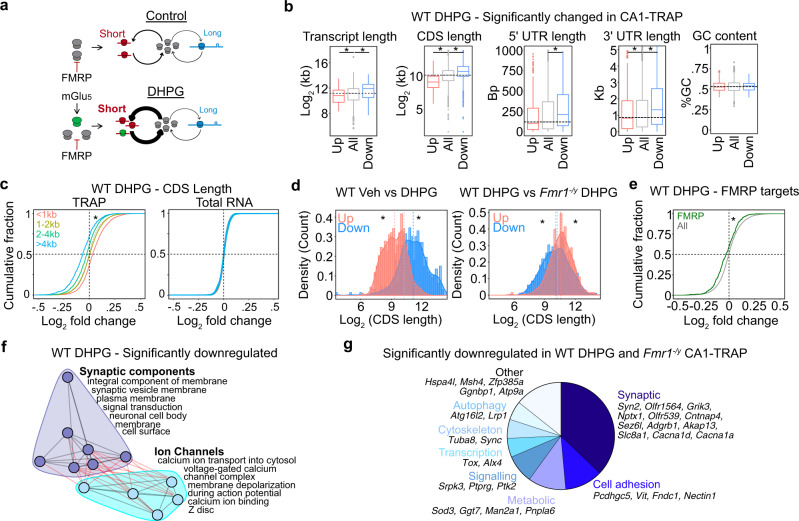

mGluR-LTD induces increased RP translation and decreased translation of synaptic proteins, which is mimicked and occluded in Fmr1−/y

The mGluR Theory suggests that the mRNAs translated in response to mGlu5 activation are already overtranslating in Fmr1−/y neurons, contributing to the protein-synthesis independence of LTD (Fig. 2a). Supporting this, protein-synthesis downstream of mGlu1/5 activation is saturated in Fmr1−/y CA14,31. Although previous work has examined proteomic changes induced by the mGlu1/5 agonist DHPG in cultured neurons32 and hippocampal slices33, a translation profiling analysis of neurons expressing LTD has not been performed. To assess this, we performed TRAP on hippocampal slices prepared from WT and Fmr1−/y littermate CA1-TRAP mice stimulated with DHPG using a protocol that induces mGluR-LTD (Fig. 2b). TRAP-seq was performed at 30 min post stimulation, which is consistent with the timeframe of protein-synthesis-dependent LTD34. Our results show that mGluR-LTD has a striking impact on the translating population in WT CA1 neurons, causing the differential expression of 696 transcripts in the TRAP population (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 2a, and Supplementary Data 4). In contrast, only 15 transcripts are significantly differentially expressed in the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP after DHPG stimulation. These results are consistent with evidence showing that DHPG does not stimulate translation in Fmr1−/y hippocampus, presumably due to a saturation of the translation machinery4,31. This effect in Fmr1−/y neurons is not due to a general disruption in signaling downstream of mGlu1/5, as the activity-driven upregulation in the immediate early genes Npas4 and Arc is seen in both genotypes (Fig. 2d), an effect that is validated by qPCR analysis of additional DHPG-treated slices (Supplementary Fig. 2b)35,36.

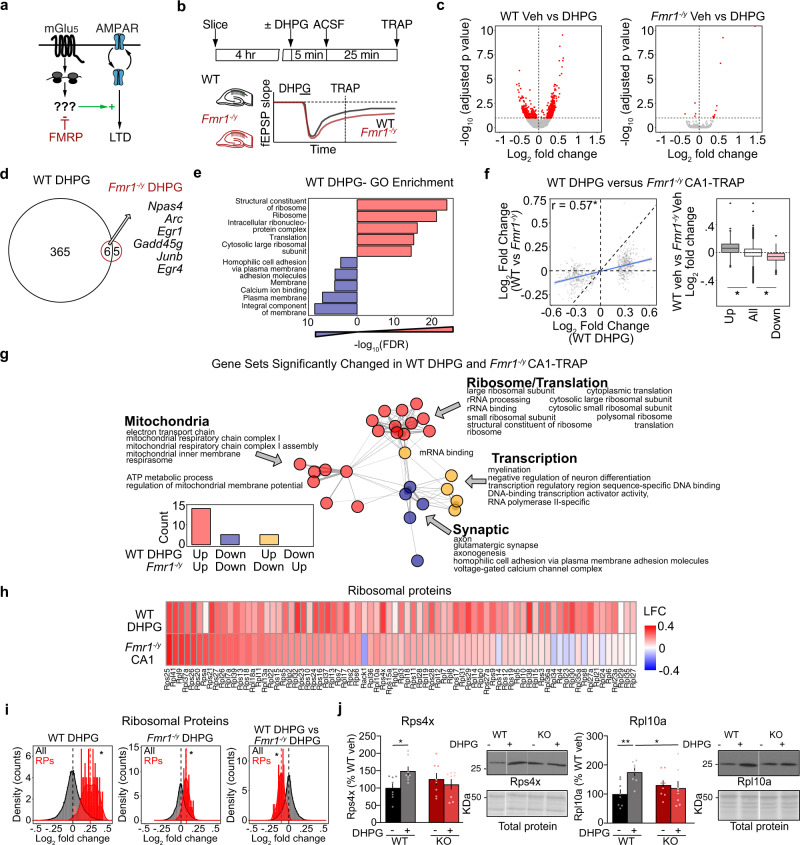

Fig. 2. mGluR-LTD induces translation changes that are mimicked and occluded in Fmr1−/y neurons, including translation of RPs.

a Schematic of the mGluR Theory of FX. b Schematic of the experimental strategy. WT and Fmr1−/y slices were recovered and stimulated for mGluR-LTD using a protocol of 5 min DHPG followed by a washout of 25 min, after which TRAP was performed. c Volcano plots of TRAP-seq data show that DHPG induces substantial significant translational changes in WT but not in Fmr1−/y CA1 neurons (DESeq2 adjusted P value < 0.1). d Quantification shows 371 targets upregulated in WT and only 11 targets in Fmr1−/y. Overlapping include immediate early genes that report neuronal activity, including Npas4 and Arc. e DAVID GO enrichment analysis of the up- and downregulated populations induced by DHPG reveals that ribosome/translation-related transcripts are enriched in the upregulated population whereas membrane/ calcium ion binding transcripts are enriched in the downregulated fraction. f Transcripts significantly changed in WT DHPG are significantly correlated with basal expression changes in Fmr1−/y (r = 0.57, *P < 2.2 × 10−16). Analysis of the significantly up- and downregulated transcripts in the WT DHPG dataset shows they exhibit a significant basal log2 fold change difference in the Fmr1−/y population as well when compared to the total population (up: Minimum −0.1769533, Lower −0.0001, Middle 0.0593, Upper 0.1197, Maximum 0.2970; all: Minimum −0.205203, Lower −0.0527, Middle −0.0026, Upper 0.0489, Maximum 0.2013; down: Minimum −0.251703, Lower −0.1103, Middle −0.0597, Upper −0.0151, Maximum 0.1263, Kruskal–Wallis test *P < 2.2 × 10−16, Post hoc two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test up *P < 2.2 × 10−16, down *P < 2.2 × 10−16). g To determine whether the gene sets altered with LTD are similar to those already altered in the Fmr1−/y translating population, GSEA was performed on the WT DHPG population, and significantly changed gene sets (adjusted P value < 0.1) were compared to those significantly changed in the Fmr1−/y population (P value < 0.01). This reveals a striking overlap with ribosome/mitochondrial terms upregulated in both WT DHPG and Fmr1−/y, and synaptic terms downregulated in both populations. h A heatmap of log2 fold change shows that RPs are basally upregulated in Fmr1−/y and in WT after DHPG stimulation. i RPs show an increase with DHPG in WT CA1-TRAP that is seen to a lesser degree in Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP (z test WT-LTD: z = 14.74, *P < 2.2 × 10−16, Fmr1−/y-LTD: z = 6.35, *P = 2.2 × 10−10). A comparison of the DHPG effect on RP expression shows the response in Fmr1−/y is occluded when compared to WT (z test: z = −8.68, *P < 2.2 × 10−16). j Immunoblot analysis from synaptoneurosome fractions isolated from WT and Fmr1−/y slices stimulated with DHPG shows a significant upregulation of Rps4x (WT = 100 ± 11.6%, WT DHPG = 148.9 ± 11.9%, Fmr1−/y = 125.6 ± 16.4%, Fmr1−/y DHPG = 110.4 ± 14.0%. Two-way ANOVA genotype × treatment *P = 0.0258, WT vs WT DHPG P = 0.0169, N = 8 littermate pairs) and Rpl10a (WT = 100 ± 14.8%, WT DHPG = 175.3 ± 12.9%, Fmr1−/y = 130.9 ± 15.1%, Fmr1−/y DHPG = 120.6 ± 22.8%. Two-way ANOVA genotype × treatment *P = 0.0212, WT vs WT DHPG P = 0.0149. N = 8 littermate pairs) in WT slices and no change in Fmr1−/y. Data are presented as mean values + /− SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further explore these changes, we performed GO analyses on the significantly up- and downregulated transcripts stimulated with DHPG in the WT CA1-TRAP. This revealed a striking functional divergence in the populations increased and decreased in translation (Fig. 2e). Interestingly, the mRNAs most enriched in the WT DHPG upregulated population were related to ribogenesis, similar to what is seen in the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP. In contrast, the population significantly reduced in translation with DHPG is enriched for transcripts encoding ion channels, cell adhesion molecules and structural synaptic elements. GSEA reveals the same functional divergence is seen in the up- and downregulated populations (Supplementary Fig. 2c, d).

Next, to determine whether the translation changes induced by mGluR-LTD in WT are similar to the basal translation changes in the Fmr1−/y CA1, we compared the expression of the LTD transcripts in DHPG-treated WT slices to the CA1-TRAP population isolated from Fmr1−/y hippocampus. Analysis of the transcripts significantly changed with DHPG in WT shows a clear significant correlation to what is basally altered in the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP (Fig. 2f). In addition, analyzing the expression of significantly up- and downregulated populations in the WT DHPG population shows that these are similarly up- and downregulated in the unstimulated Fmr1−/y population as compared to the average. To explore the functional relevance of the translation changes induced by DHPG and occluded in Fmr1−/y neurons, we performed GSEA to compare gene sets significantly altered with DHPG in WT versus those basally altered in the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP. This revealed a striking overlap, with 82% of gene sets significantly changed with DHPG in WT also significantly changed in the same direction in the basal Fmr1−/y population (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Data 5). Interestingly, the population that is both upregulated with DHPG and constitutively upregulated in Fmr1−/y is enriched for RPs and rRNA processing, as well as mitochondrial function. In contrast, the downregulated population is enriched for glutamatergic synapse, homophilic cell adhesion, voltage-dependent calcium channels and axonal function. These results indicate that changes in the translating fraction of CA1 neurons that occur during mGluR-LTD in WT are largely mimicked and occluded in the Fmr1−/y hippocampus, supporting the model put forth by the mGluR Theory.

To identify the newly synthesized proteins most likely involved in the exaggerated LTD phenotype, we examined the targets significantly upregulated in DHPG-treated WT slices and those basally upregulated in the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP population at a threshold of P < 0.05. This analysis shows a significant overlap between the upregulated populations and identified 92 candidates (Supplementary Fig. 2e and Supplementary Data 6). Consistent with our GSEA results, ribosome-related transcripts comprise the greatest proportion of the overlapping population (Supplementary Fig. 2f). Analysis of individual RPs reveals that most are upregulated in both datasets, with 11 of the 12 RPs significantly upregulated in the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP population also significantly upregulated with DHPG in WT (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Data 7). This surprising result led us to question whether new RP synthesis was supporting mGluR-LTD. Although the majority of RP synthesis occurs in the nucleus where ribosomes are assembled, the enrichment of RP mRNAs in neuronal processes is a long-standing observation37–39. Recent studies have confirmed that RPs are locally synthesized and incorporated into existing ribosomes in axons and dendrites. Shigeoka et al. show that newly synthesized RPs incorporate into existing ribosomes in axons, and inhibiting local synthesis of Rps4x impairs the protein synthesis required for axon branching40. Fusco et al. show that RP transcripts in dendrites are rapidly synthesized and incorporated into existing ribosomes41. Both studies show that a subset of RPs proximal to the cytosolic face of the ribosome are found to be more frequently incorporated into existing ribosomes. To determine whether these RPs were translated in response to mGlu1/5 activation, we examined the population upregulated in the CA1-TRAP fraction of WT slice with DHPG stimulation. Our results show that 6 of the 11 rapidly exchanging RPs identified in ref. 41 and 9 of the 11 identified in ref. 40 are significantly increased with DHPG (Supplementary Data 7). Interestingly, Rps4x is one of the most significantly increased RPs in the DHPG dataset. These results suggest that RPs synthesized in response to mGlu1/5 activation are incorporated into existing ribosomes.

To determine whether the upregulation of RPs with DHPG was occluded in Fmr1−/y CA1 neurons, we quantified the RP gene set in both genotypes after stimulation. Our results show that DHPG significantly increases the RP gene set in both WT and Fmr1−/y neurons, however, the effect in the Fmr1−/y population is significantly impaired when compared to that seen in WT (Fig. 2i). To determine whether this effect could be seen at the protein level, we isolated synaptoneurosome fractions from WT and Fmr1−/y slices 1 h after stimulation with DHPG and performed immunoblotting for individual RPs. Our results show that DHPG simulation significantly increases both Rpl10a and Rps4x in the synaptic fractions of WT slices, and these RPs are basally elevated in Fmr1−/y slices (Fig. 2j and Supplementary Fig. 2g). These results confirm that there is a rapid increase in RPs at WT synapses after DHPG treatment that is mimicked and occluded in the Fmr1−/y hippocampus.

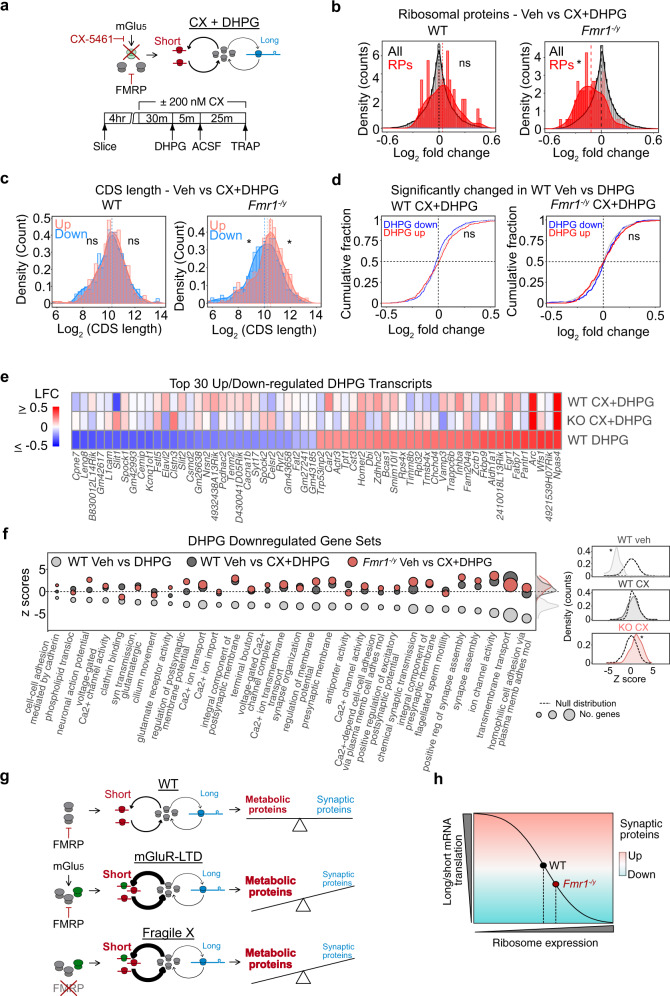

Inhibiting RP translation blocks mGluR-LTD in WT but not Fmr1−/y hippocampal CA1

Our TRAP-seq results showing the significant increase in RP translation upon mGlu1/5 stimulation led us to wonder whether new RP synthesis was required for mGluR-LTD (Fig. 3a). Ribogenesis requires the coordinated activation of RNA polymerase (Pol) I to transcribe 45 S precursor rRNA, RNA Pol II to transcribe RP transcripts, and RNA Pol III to transcribe 5S rRNA42. To inhibit the translation of RPs downstream of mGlu1/5 activation we incubated slices with the selective Pol I inhibitor CX-5461, which blocks the transcription of rRNA and the subsequent transcription of RPs without disrupting general transcription mediated by RNA Pol II43,44 (Fig. 3a). Incubation with CX-5461 has been shown to impact plasticity in acute hippocampal slices within 3 h while preserving overall cell health and baseline activity45. We, therefore, tested whether this compound could effectively block DHPG-induced RP synthesis. First, to confirm the efficacy of CX-5461 in our system, we incubated hippocampal slices with 200 nM drug or vehicle and measured nucleolar volume in CA1 pyr neurons using fibrillarin immunostaining followed by confocal imaging and 3D reconstruction. We find that nucleolar volume is significantly reduced in both WT and Fmr1−/y hippocampal slices within 45 min of incubation with CX-5461 (Fig. 3b). Next, we tested whether CX-5461 blocked the increased RP translation stimulated by mGlu1/5 activation. Slices were pre-incubated in 200 nM CX-5461 for 30 min and stimulated with DHPG for 5 min followed by a 25-min washout. The translation of Rps25 was measured using TRAP and qPCR. Our results show that DHPG induces a significant increase in Rps25 translation in WT slices that is blocked in the presence of CX-5461 (Fig. 3c). Consistent with the RNA-seq results, the increase in Rps25 translation is impaired in Fmr1−/y slices, and this is not significantly altered with CX-5461.

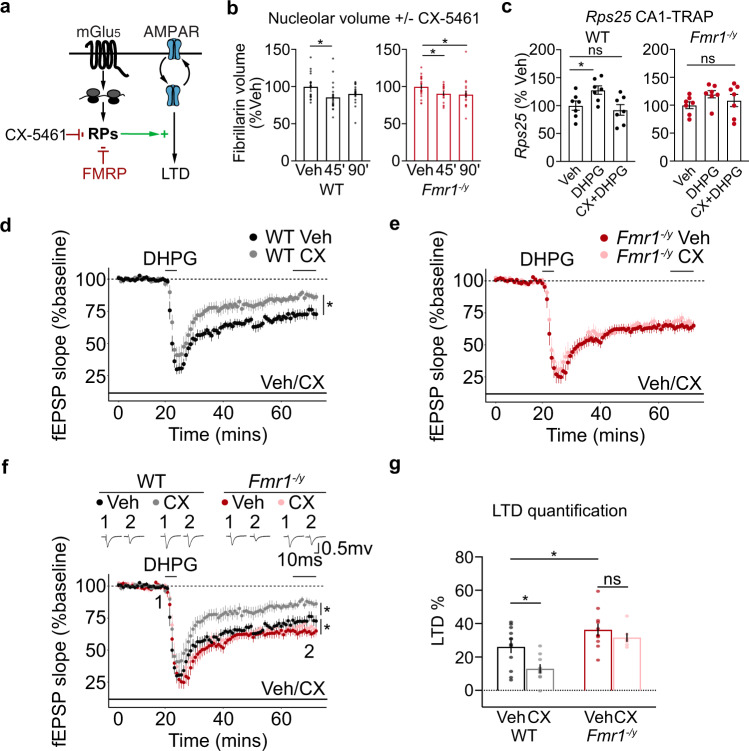

Fig. 3. RP translation is required for mGluR-LTD in WT but not in Fmr1−/y hippocampal CA1.

a Schematic of experimental strategy. Specific RNA Pol1 blocker CX-5461 was used to ribogenesis, including RP translation. b Fibrillarin staining of hippocampal slices shows that nucleolar volume of CA1 pyr neurons is significantly reduced in both genotypes with 200 nM CX-5461 treatment by 45 min (WT: Veh = 100 ± 3.0%, CX 45’ = 85.9 ± 3.8%, CX 90’ = 90.8 ± 2.7%. One-way ANOVA *P = 0.0206, post hoc Veh-45’ *FDR = 0.0141, Veh-90’ FDR = 0.070. N = 20 neurons per group). (Fmr1−/y: Veh = 100 ± 2.5%, CX 45’ = 90.96 ± 2.4%, CX 90’ = 90.05 ± 4.2%. One-way ANOVA *P = 0.0488, post hoc *Veh-45’ FDR = 0.0485, *Veh-90’ FDR = 0.0485, N = 20 neurons per group). c CA1-TRAP and qPCR analysis of Rps25 translation in hippocampal slices confirms an upregulation in the WT in response to DHPG at 30’ that is blocked with 200 nM CX-5461. DHPG does not elicit a significant increase in Rps25 translation in Fmr1−/y slices nor does CX-5461 have a significant effect (WT: Veh = 100 ± 8.22%, DHPG = 127.9 ± 7.5%, CX + DHPG = 92.3 ± 9.5%. One-way ANOVA *P = 0.0388, post hoc Veh-DHPG *FDR = 0.0121, Veh-CXDHPG FDR = 0.3506, N = 7 littermate pairs. Fmr1−/y: Veh = 100 ± 6.2%, DHPG = 119.6 ± 6.5%, CX + DHPG = 108.5 ± 10.9%. One-way ANOVA P = 0.2627). N = 7 littermate pairs. Data are presented as mean values + /− SEM. d, e mGluR-LTD was measured in hippocampal CA1 in the presence of vehicle or CX-5461. Slices were prepared from Fmr1−/y and WT, recovered for at least 2 h, and exposed to vehicle or 200 nM CX-5461 for at least 30 min prior to DHPG application and throughout the LTD recording. CX-5461 causes a significant reduction in LTD magnitude in WT CA1 versus vehicle (Veh = 26.13% ± 3.5% N = 12 animals, CX-5461 = 13.00% ± 2.4% N = 10 animals, *FDR = 0.0031). In contrast, CX-5461 does not significantly reduce LTD magnitude in Fmr1−/y CA1 versus vehicle (Veh = 36.337% ± 3.9% N = 11 animals, CX-5461 = 31.717% ± 2.3% N = 7, animals. FDR = 0.1224). f, g Quantification of all four groups show a differential effect of CX-5461 on LTD in each genotype (WT-Veh = 26.13% ± 3.5% N = 12 animals, WT-CX54611 = 13.00% ± 2.4% N = 10 animals, Fmr1−/y Veh = 36.337% ± 3.9% N = 11 animals, Fmr1−/y CX-5461 = 31.717% ± 2.3% N = 7, animals. Two-way ANOVA, genotype *P < 0.001 treatment *P = 0.01, post hoc: WT-Veh vs Fmr1−/y-Veh *FDR = 0.0107, WT-Veh vs WT-CX-5461 *FDR = 0.0031, Fmr1−/y-Veh vs Fmr1−/y-CX-5461 FDR = 0.1224). Data are presented as mean values + /− SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Having confirmed that CX-5461 blocks the RP translation downstream of mGlu1/5 activation, we next assessed the impact on mGluR-LTD. Hippocampal slices were prepared from juvenile Fmr1−/y and WT littermates as in previous studies, with recordings performed blind to genotype and in an interleaved fashion. Vehicle or 200 nM CX-5461 was pre-incubated for at least 1 h, LTD induced with a 5-min application of 50 µM S-DHPG and fEPSPs were recorded over 1 h. We find that CX-5461 significantly impairs LTD in WT slices, indicating that ribosomal protein translation is required for mGluR-LTD (Fig. 3d). However, in Fmr1−/y slices where ribosomes are overexpressed, CX-5461 has no impact on mGluR-LTD magnitude (Fig. 3e). The significant elevation in vehicle-treated WT and Fmr1−/y slices confirms the exaggerated LTD phenotype is present, and not impacted by CX-5461 (Fig. 3f, g). These results show that preventing the RP translation downstream of mGlu1/5 activation impairs mGluR-LTD in WT, but not Fmr1−/y hippocampus.

Fmr1−/y neurons exhibit a length-dependent imbalance in mRNA translation that disfavors long transcripts

Our results show that RPs are overtranslated in Fmr1−/y neurons, translated downstream of mGlu1/5, and are required for LTD. However, the mechanism by which a change in ribosome availability could result in LTD remained unclear. Along with the increase in RPs, our TRAP-seq results showed that a consequence of LTD is the downregulation of synaptic transcripts, which tend to be longer than average46. In contrast, we observed an upregulation of transcripts encoding metabolic proteins, which tend to be short47. Interestingly, a conserved property seen in cells from yeast to humans is that the rate of protein production from shorter mRNAs is greater than that of longer transcripts48–50. Modeling studies have proposed that this difference could be due to the slower rate at which translation initiation occurs on long transcripts, often due to secondary structures present in the elongated 5’ untranslated region (5’UTR)50–52. It has also been suggested that the smaller distance between 5’ and 3’ UTRs gives a competitive advantage to mRNAs with shorter coding sequences (CDSs) by facilitating ribosome re-initiation49. These models predict a change in the concentration of ribosomes will disproportionately impact shorter mRNAs because they are more rapidly translating49,53,54. This prediction is consistent with recent work showing that RP mutations that reduce cellular ribosome expression exhibit a disproportionately greater reduction in the translation of short versus long mRNAs44.

Based on these studies, we wondered whether the increased ribosome availability seen in Fmr1−/y neurons and in DHPG-stimulated neurons changed the profile of translating mRNAs in a length-dependent manner. If so, this would result in a reduced translation of long mRNAs encoding synaptic proteins. This change in the composition of the translating population would be consistent with a sustained depression of synaptic strength (Fig. 4a). This model predicts that (1) FX neurons exhibit a reduced translation of long mRNAs, (2) the long mRNAs under-translated in Fmr1−/y neurons are associated with synaptic stability, (3) stimulation of mGlu1/5 induces the same reduction in long mRNA translation in WT, (4) inhibiting ribosome protein translation prevents the reduction of long mRNA translation upon mGlu1/5 stimulation.

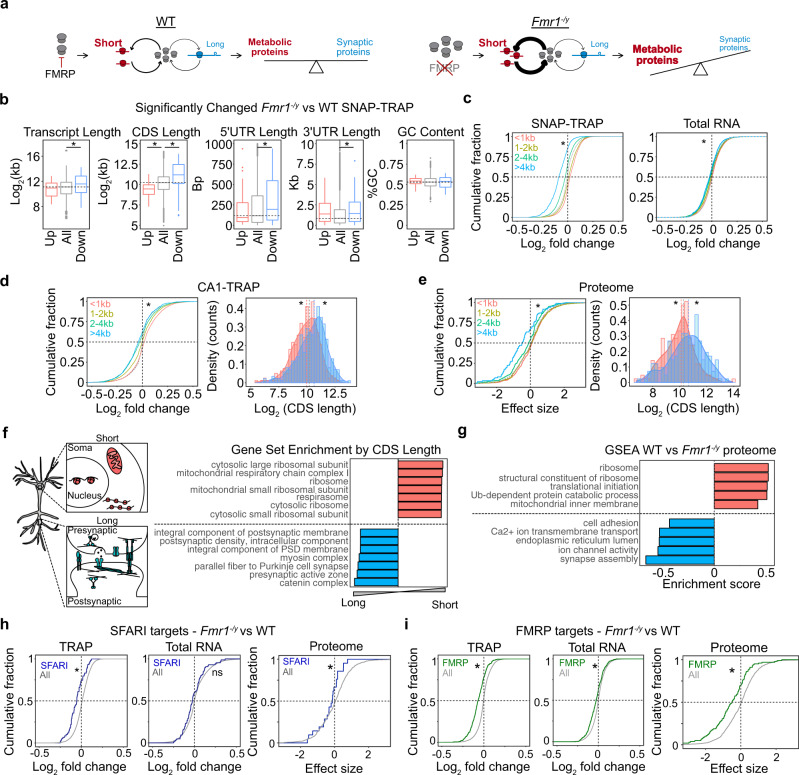

Fig. 4. Under-translation of long mRNAs causes reduced expression of synaptic proteins, autism risk factors, and FMRP targets in Fmr1−/y hippocampal neurons.

a A model of altered translation in FX proposes that increased ribosome production changes the differential rate of translation between short and long mRNAs, which ultimately alters the proportion of proteins with metabolic versus synaptic functions. b The significantly altered Fmr1−/y SNAP-TRAP population (DESeq2 adjusted P value < 0.1) exhibits an imbalance in transcript length, CDS length, 5’UTR length and 3’UTR that indicates under-translation of long, low-initiation mRNAs (transcript length: Kruskal–Wallis *P = 4.01 × 10−5, Wilcoxon rank-sum test all vs up P = 0.733, all vs down *P = 7.28 × 10−6, CDS length: Kruskal–Wallis *P = 2.219 × 10−14, Wilcoxon rank-sum test all vs up *P = 3.181 × 10−5, all vs down *P = 1.516 × 10−11, 5’UTR length: Kruskal–Wallis *P = 0.01179, Wilcoxon rank-sum test all vs up P = 0.9794, all vs down *P = 0.00282, 3’UTR length: Kruskal–Wallis *P = 0.0022, Wilcoxon rank-sum test all vs up P = 0.1103, all vs down *P = 0.001827, coding GC content: Kruskal–Wallis P = 0.5817). c A binned analysis of the total Fmr1−/y SNAP-TRAP population shows that the CDS length imbalance is seen in the whole ribosome-bound population, with the shortest group showing the most positive log2 fold change distribution and the longest group showing the lowest log2 fold change (two-sided KS test, <1 kb vs >4 kb *P < 2.2 × 10−16 d = 0.537). The total transcriptome also demonstrates this property but at a much lower magnitude (KS test <1 kb vs >4 kb *P = 2.00 × 10−11 d = 0.1470). d The Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP population shows a similar CDS length bias that can be seen in a binned analysis or a comparison of the top 500 most up- and downregulated mRNAs ranked by log2 fold change (two-sided KS test <1 kb vs >4 kb *P < 2.2 × 10−16, two-sample z test all vs up z = −3.416, *P = 0.0006356, all vs down z = 5.0454, *P = 4.525 × 10−7). e The Fmr1−/y proteome exhibits a CDS length-dependent imbalance that mirrors the results seen by TRAP, both in a binned analysis (two-sided KS test <1 kb vs >4 kb *P = 2.84 × 10−6) and comparison between the 200 most up- and downregulated proteins (two-sample z test, up vs all: z = −2.8216 *P = 0.005, down vs all: z = 3.0408, *P = 0.0024). f A Gene set analysis ranked by CDS length reveals that shorter transcripts are enriched with the ribosome and mitochondrial genes whereas longer transcripts are enriched with synaptic structure-related genes. g GSEA of the Fmr1−/y proteome shows a significant downregulation of synaptic gene sets and a significant upregulation of ribosome/mitochondrial gene sets. h SFARI targets are downregulated in the Fmr1−/y SNAP-TRAP population (two-sample z test, z = −5.43 P = 5.65 × 10−8) and not changed in the total RNA population (two-sample z test, z = −1.64, P = 0.099). SFARI targets are significantly underexpressed in the Fmr1−/y proteome, consistent with the under-translation seen by TRAP (two-sample z test, z = −2.0008, *P = 0.045). i FMRP targets are significantly downregulated in the Fmr1−/y SNAP-TRAP population (two-sample z test, z = −12.461 *P < 2.2 × 10−16) and changed to a lesser degree in total RNA population (two-sample z test, z = −5.42, P = 5.805 × 10−8). FMRP targets are significantly reduced in the Fmr1−/y proteome (two-sample z test, z = 5.30, *P = 1.135 × 10−7).

To test the first prediction, we investigated whether Fmr1−/y neurons exhibit a length-dependent change in the translating mRNA population by comparing the significantly altered population in the Fmr1−/y SNAP-TRAP fraction. This analysis revealed a striking relationship between differential expression and transcript length in the Fmr1−/y TRAP. The significantly downregulated population contains transcripts with longer CDS regions versus the average population, and the upregulated population contains transcripts with shorter CDS regions (Fig. 4b). Downregulated mRNAs also contain significantly longer 5’ UTRs, consistent with a reduced initiation rate. An alteration in translation GC content of the CDS, which has also been implicated in translation efficiency, is not associated with differential expression52. We next examined differential expression in the total population by comparing groups binned by CDS length <1 kb, 1–2 kb, 2–4 kb, and >4 kb. This analysis again shows a significant shift in Fmr1−/y TRAP fraction that disfavors long transcripts (Fig. 4c). The same imbalance is seen in the total transcriptome, however, the magnitude of this change is significantly smaller. This indicates that the effect seen in the TRAP is not driven by a change in transcript abundance.

Our next question was whether the same length-dependent shift is seen Fmr1−/y CA1 pyr neurons, so we performed the same analysis on the CA1-TRAP population. Our results show the same relationship between fold change and CDS length seen in the SNAP-TRAP population (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 3a). To ensure this difference was not due to a difference in transcript number between groups, we performed an additional analysis comparing an equal number of transcripts (500) in the up- and downregulated population when ranked by nominal p-value (Fig. 4e). This confirmed a significant difference in length between up- and downregulated transcripts in the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP population. This imbalance persists when normalized to the total transcriptome, and is not due to a systemic length bias in the RNA-seq dataset (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c)55. Together these results indicate an under-translation of long mRNAs in Fmr1−/y neurons.

Interestingly, the length of RP transcripts is significantly shorter than average, raising the possibility that the upregulation of RPs is a be a consequence rather than the cause of the length-dependent shift. However, further analyses show that the RP population is significantly more upregulated than equal-length transcripts, suggesting it is not driven by the elevated translation of short mRNAs in Fmr1−/y neurons (Supplementary Fig. 3d).

The length-dependent translation shift in Fmr1−/y neurons reduces the expression of synaptic proteins, autism risk factors, and FMRP targets

Given the length-dependent imbalance in translation seen in Fmr1−/y neurons, we next asked whether this was mirrored in a length-dependent change in protein expression. We, therefore, performed an analysis of length on the most significantly up and downregulated proteins in the Fmr1−/y hippocampal proteome (Fig. 4e). Consistent with our TRAP-seq results, we find the population downregulated in the Fmr1−/y is enriched for proteins encoded by longer CDS transcripts, with proteins encoded by transcripts >4 kb exhibiting the most significant downregulation (Fig. 4e). Similar to TRAP-seq, there is no correlation between significance and protein length (Supplementary Fig. 3e).

The second prediction of our model is that the long mRNAs under-translated in Fmr1−/y neurons encode proteins involved in synaptic stability. To determine whether mRNA length was a factor in functional segregation in the CA1 translating mRNA population we performed a gene set analysis ranked by CDS length (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Data 8). This reveals longer CDS transcripts are enriched for synaptic adhesion molecules, pre- and postsynaptic assembly proteins, and calcium channels, while shorter transcripts are enriched for nuclear, ribosomal, and mitochondrial proteins. The CDS length-dependent imbalance in translation in FX neurons, therefore, predicts an underproduction of proteins important for synaptic function. To test this, we employed GSEA on the Fmr1−/y proteome and confirm that the most significantly enriched categories in the underexpressed population are related to synaptic structure and function (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 3f). Although differences in biological fractionation and analysis make it difficult to compare significant differences in individual targets identified in the Fmr1−/y proteome to those identified by TRAP-seq, we nevertheless find there is a significant overlap between the populations of targets significantly downregulated in the Fmr1−/y versus WT (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 3g). Overlapping targets include proteins involved in the synaptic structure that have previously been implicated in FX including Shank1 and Map1b (Supplementary Supplementary Data 9–10). These results show that the long synaptic mRNAs downregulated in the Fmr1−/y TRAP are consistent with those reduced in the Fmr1−/y proteome.

Interestingly, it has been noted that autism risk factors identified by the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) are encoded by long genes56–58. Downregulation of these targets would be predicted to have deleterious consequences on neuronal function, and we therefore investigated whether this group was reduced in Fmr1−/y neurons. Our results show that SFARI transcripts are significantly downregulated in the Fmr1−/y SNAP-TRAP and CA1-TRAP populations, which is consistent with the increased length of this population in our dataset (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 3h, i). Furthermore, there is a significant correlation between differential expression and length even within the SFARI population (Supplementary Fig. 3j). The same downregulation is not seen in the total Fmr1−/y transcriptome, indicating it is not driven by reduced abundance (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 3j). Additional analyses show that the length of the CDS, and not the gene, is driving reduced expression in the TRAP population (Supplementary Fig. 3j, k). Importantly, examination of the Fmr1−/y proteome reveals an underexpression of proteins encoded by SFARI targets, indicating the change in translation has an impact on the steady-state proteome (Fig. 4h).

FMRP targets are also longer in length versus other neuronal transcripts and we and others have shown these targets are underexpressed in the ribosome-bound fraction of Fmr1−/y CA1 neurons23,59,60. Our results confirm that FMRP targets are reduced in the Fmr1−/y SNAP-TRAP fraction consistent with results from CA1 neurons, with a small but significant effect seen in the total transcriptome (Fig. 4i). However, it was not clear that this downregulation would indicate a reduction in protein expression, as recent studies indicate the reduced ribosome binding of these targets may represent accelerated elongation13,61. To investigate this question, we quantified FMRP targets in the Fmr1−/y proteome, and found the same downregulation seen in the TRAP fraction (Fig. 4i). Together, these results confirm an underexpression of SFARI risk factors and FMRP targets that is consistent with the reduced translation of long transcripts.

mGluR-LTD mimics the length-dependent translation imbalance seen in Fmr1−/y neurons

According to the third prediction of our model, the reduced translation of long mRNAs should be a consequence of mGluR-LTD, and this should be occluded in Fmr1−/y neurons (Fig. 5a). To test this, we performed the same analysis of transcript length in the DHPG-induced CA1-TRAP fraction. Remarkably, we find that the same decrease in long mRNAs observed in Fmr1−/y CA1 neurons is induced in WT neurons with the application of DHPG (Fig. 5b). Similar to the downregulated population in Fmr1−/y neurons, these transcripts exhibit a significantly longer 5’UTR indicative of a reduced initiation rate. Analysis of the total significantly altered population binned by kb shows that upregulated targets are significantly shorter than average, and downregulation targets are significantly longer than average, effects that are not seen in the total transcriptome (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. 4a, and Supplementary Data 11). Next, we investigated whether the basal length-dependent shift in the basal Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP population impairs a further shift with DHPG. Our analysis of the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP population shows that there is a small but significant shift in length in the CA1-TRAP after DHPG stimulation, however, this is much smaller than that observed in WT (Supplementary Fig. 4b). To more directly compare the impact of DHPG between genotypes, we examined the 500 most up- and downregulated transcripts. This analysis reveals a significant divergence in length between the up- and downregulated populations in DHPG-treated WT slices that is significantly reduced in DHPG-treated Fmr1−/y slices (Fig. 5d). These changes are not seen in the total transcriptome (Supplementary Fig. 4c). These results show that the length-dependent shift seen with DHPG stimulation is occluded in the Fmr1−/y hippocampus.

Fig. 5. Translation of long mRNAs is reduced in CA1 pyr neurons with induction of mGluR-LTD.

a Our model predicts that the increased ribosome production seen with mGluR-LTD will cause a similar length-dependent imbalance as seen in the Fmr1−/y translating population. b Analysis of the significantly changed population in WT DHPG CA1-TRAP shows a significant imbalance in transcript length, CDS length, 5’UTR length, and 3’UTR length that matches the basal Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP population (transcript length: Kruskal–Wallis P = 2.105 × 10−14, Wilcoxon rank-sum test all vs up P = 6.042 × 10−5, all vs down P = 1.022 × 10−11, CDS length: Kruskal–Wallis *P < 2.2 × 10−16, Wilcoxon rank-sum test all vs up *P < 2.2 × 10−16, all vs down *P < 2.2 × 10−16, 5’UTR length: Kruskal–Wallis *P = 0.0005, Wilcoxon rank-sum test all vs up P = 0.0808, all vs down *P = 0.0006, 3’UTR length: Kruskal–Wallis *P = 0.000, Wilcoxon rank-sum test all vs up *P = 0.03821, all vs down *P = 0.0002, coding GC content: Kruskal–Wallis P = 0.9375). c A binned analysis shows that there is a CDS length shift in the TRAP fraction (two-sided KS test <1 kb vs >4 kb *P < 2.2 × 10−16) and no change in the total transcriptome (two-sided KS test <1 kb vs >4 kb P = 0.698). d Comparison of the top and bottom 500 differentially expressed transcripts in WT DHPG shows a significant effect of length (all vs up z = −17.831, *P < 2.2 × 10−16, all vs down z = 10.774, *P < 2.2 × 10−16). Comparison between WT DHPG vs Fmr1−/y DHPG reveals that the length shift is occluded in Fmr1−/y (all vs up z = 5.2982, *P = 1.16 × 10−7, all vs down z = −2.2827, *P = 0.02). e As predicted by their longer lengths, FMRP targets are reduced with DHPG in the WT CA1-TRAP population (two-sample z test, z = 5.333, P = 9.66 × 10−8). This change is not seen in the total transcriptome (two-sample z test, z = −2.039, P = 0.041). f Network analysis of the downregulated GO terms reveals a concentration of synaptic components and ion-channel clusters. g Analysis of the population significantly downregulated in both WT DHPG and Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP fractions (P < 0.05) identifies 42 transcripts, many of which are involved in synaptic function.

We next asked whether there was a functional similarity in the transcripts downregulated with DHPG in the WT TRAP versus those basally reduced in the Fmr1−/y TRAP. First, we asked whether the reduction in long mRNAs coincides with a reduction in FMRP targets, similar to what is seen in the Fmr1−/y TRAP. Our results show that there is a significant reduction in FMRP targets in the WT CA1-TRAP after DHPG stimulation, which is not seen in the total transcriptome (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 4d). Next, we performed a clustering analysis of GO terms enriched in the population downregulated in WT DHPG. This revealed that downregulated targets largely fell into categories related to synaptic components and ion channels, similar to what is seen in the Fmr1−/y proteome (Fig. 5f). Downregulated targets include those related to synaptic signaling and structural stability including cadherins/protocadherins (Pcdhac2, Pcdh1, Celsr3, Celsr2, Cdh18, Cdh2, Pcdhgc5, etc.) and cell adhesion molecules (L1cam, Nrcam, Focad, Cadm3, etc.) (Supplementary Fig. 4e). In addition, the downregulated population contains multiple targets that are involved in calcium regulation downstream of mGlu1/5 activation, including voltage-gated calcium channel transcripts (Cacna1b, Cacna1c, Cacna1i, Cacna1ad2) and ryanodine receptors (Ryr2 and Ryr3)62 (Supplementary Fig. 4f). To determine the similarity between the specific transcripts altered with DHPG in WT and those basally altered in the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP population, we compared the targets significantly downregulated in both populations (P < 0.05). This analysis shows a significant overlap, with the majority of the 42 overlapping targets related to synaptic function (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Fig. 4g, and Supplementary Data 12). Together, these results show that transcripts downregulated with DHPG in WT are functionally similar to those basally downregulated in the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP.

Inhibition of ribosomal protein production prevents mGluR-induced changes in translation

A critical test of our model is whether disruption of ribosomal protein translation alters the length-dependent change in translation downstream of mGluR-LTD (Fig. 6a). To test this fourth prediction, we stimulated hippocampal slices with DHPG to induce LTD in the presence of 200 nM CX-5461 and performed TRAP-seq to identify CA1 neuron-specific translation (Supplementary Fig. 5a and Supplementary Data 13). Consistent with our first TRAP-seq experiment, we find that DHPG stimulates RP translation in WT neurons, and this is significantly impaired in Fmr1−/y neurons (Supplementary Fig. 5b). In stark contrast, incubation with CX-5461 blocks the increase in RP translation stimulated by DHPG in WT neurons and results in a small but significant downregulation in RPs in Fmr1−/y slices that may be due to elevation in the basal population (Fig. 6b). Remarkably, analysis of the 500 most up- and downregulated targets reveals that CX-5461 also eliminates the length-dependent shift in translation induced by DHPG (Fig. 6c). This provides a causal link between RP translation and the length-dependent shift in translation induced by mGlu1/5 activation. Importantly, CX-5461 does not alter the upregulation of immediate early genes such as Npas4 with DHPG in either genotype, indicating there is no impairment of the general responsiveness to mGlu1/5 stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 5c, d and Supplementary Data 13).

Fig. 6. Inhibition of RP translation prevents reduction of long mRNA translation during mGluR-LTD.

a Our model predicts that preventing the increase in RP translation downstream of mGlu1/5 activation should prevent the length-dependent shift in translation. The experimental timeline for CX + DHPG CA1-TRAP-seq experiment is shown. b Incubation with CX-5461 blocks the increase in RP translation seen with DHPG stimulation in the WT CA1-TRAP population (RP: two-sample z test, z = 0.79134, P = 0.428741). CX-5461 causes a slight reduction in RP translation with DHPG in Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP (RP: two-sample z test, z = −4.30, *P = 1.69 × 10−5). c The length-dependent shift in translation seen with DHPG in WT is eliminated with incubation of CX-5461 (Top 500: two-sample z test, All vs up z = 0.2897, P = 0.77200, all vs down z = 0.10510, P = 0.916292). A slight reversal of the length-dependent imbalance evoked by DHPG is also seen in the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP (top 500: two-sample z test, All vs Up z = 3.1899, *P = 0.0014, all vs down z = −2.282, *P = 0.022). d LTD transcripts were defined as significantly regulated the first in WT DHPG TRAP-Seq dataset. Incubation with CX-5461 eliminates the up- and downregulation of LTD transcripts with DHPG application in WT (two-sample z test, LTD up: z = 1.619, P = 0.1054, LTD down: z = −0.9977, P = 0.3184). Application of CX-5461 has no impact on the response of LTD transcripts to DHPG in the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP (two-sample z test up z = 1.838, P = 0.0659; down z = 1.694, P = 0.0901). e A heatmap of log2 fold change shows the significant impact of CX-5461 on the 30 most up- and downregulated LTD transcripts in WT and Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP. The preserved upregulation of immediate early genes Npas4 and Arc is highlighted. f Gene sets significantly downregulated with LTD in WT are no longer downregulated with CX-5461 in either genotype. Z tests of the distribution of LTD downregulated gene sets show that significant downregulation in vehicle-treated WT (two-sample z test, z = −18.24, *P < 2.2 × 10−16) is no longer changed after incubation with CX-5461 (two-sample z test, WT CXDHPG: z = −0.15442, P = 0.8773), In the Fmr1−/y CA1-TRAP, CX-5461 causes a slight upregulation of these gene sets, indicating a reversal in the translation regulation of these mRNAs (two-sample z test, z = 4.4808, *P = 7.435 × 10−6). g Our results fit a model whereby activation of mGlu1/5 causes an increase in ribosome production that drives an imbalance in the translation of short versus long mRNAs. This imbalance is similarly driven by the loss of FMRP, which increases ribosome production and mimics the LTD translation state. Ultimately, the reduced translation of long mRNAs reduces the expression of proteins that participate in synaptic stability and function. h We propose that the altered translation imbalance driven by excessive ribosome production may underlie a number of phenotypes in FX that are derived from synaptic weakening or instability.

To determine whether CX-5461 had a significant impact on the translation of DHPG-regulated targets, we analyzed the expression of the transcripts identified in our first DHPG TRAP-seq experiment. Validating our original results, targets significantly up- and downregulated in our first dataset are significantly up- and downregulated in the Veh WT DHPG population of the CX + DHPG dataset (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Consistent with the impairment of mGluR-LTD, application of CX-5461 eliminates the differential expression of translating mRNAs seen with DHPG stimulation (Fig. 6d). Examination of individual DHPG-stimulated targets shows that CX-5461 prevents the differential translation of most, with the exception of immediate early genes such as Npas4, Arc, and Junb, which are transcribed in response to changes in neuronal activity (Fig. 6e). To assess the functional impact of CX-5461 on the LTD response, we examined the gene sets identified by GSEA in the population of mRNAs normally downregulated in the DHPG CA1-TRAP. Our results show that these gene sets are no longer altered in the presence of CX-5461 in WT, and are mildly reversed in the Fmr1−/y population. The downregulated transcripts most impacted by CX-5461 are related to cell adhesion, ion-channel activity, and synapse assembly (Fig. 6f). These results show that inhibition of RP translation impairs a translation profile that supports synaptic weakening upon stimulation with DHPG. Together, our results suggest that an imbalance in the translation of longer versus shorter mRNAs is induced by RP translation downstream of mGlu1/5 activation, and this translation state is basally exacerbated in Fmr1−/y CA1 neurons (Fig. 6g).

Discussion

This study provides multiple novel insights into the nature of dysregulated translation in FX neurons. First, a combined TRAP-seq and proteomic screen identify ribosomal protein transcripts as the major gene category overtranslated in Fmr1−/y hippocampal neurons, which is manifested as an overexpression of ribosomes. Second, this elevation in RP translation coincides with a length-dependent shift in the translating mRNA population that favors shorter versus longer mRNAs, a profile that reduces the expression of synaptic proteins, SFARI risk factors, and FMRP targets. Third, stimulation of mGlu1/5 in WT CA1 neurons mimics the increased translation of RPs and decreased translation of long mRNAs, and this is occluded in Fmr1−/y CA1 neurons. Importantly, inhibiting the increase in RP translation with ribogenesis inhibitor CX-5461 prevents the length-dependent shift in translation and blocks mGluR-LTD. This suggests the imbalanced translation of long versus short mRNAs in Fmr1−/y neurons is downstream of excessive RP translation (Fig. 6h).

Our results are consistent with previous work showing that changes in ribosome expression alter the composition of the translating mRNA population in a length-dependent manner44,53. By increasing ribosome availability, we suggest that the translation of shorter versus longer mRNAs has become exacerbated in Fmr1−/y neurons due to the competitive advantage of short transcripts with a higher translation efficiency. We show that the paradoxical reduction in the translation of long mRNAs in Fmr1−/y neurons mimics the translation state of LTD and coincides with a reduced expression of proteins involved in synaptic function, many of which are implicated in autism. Although the effect sizes seen in our RNA-seq and proteomics datasets are relatively small, the modest magnitude of these changes is consistent with the hallmark Fmr1−/y phenotypes of exaggerated mGluR-LTD and excessive protein synthesis, which are expressed no more than 15–20% above WT4,15. These phenotypes have provided important direction for both understanding the biology of FX and for identifying therapeutic strategies including mGlu5 antagonists and lovastatin20,63,64. The prediction from this current study is that a long-term reduction in ribogenesis would alter the translating population in Fmr1−/y neurons to resemble WT, thereby increasing the production of synaptic elements. Future work is needed to test this hypothesis.

Although we show excess RP translation contributes to dysfunction in Fmr1−/y neurons, it is not clear how this cellular phenotype arises from the loss of FMRP. One possibility is that increased RP translation results from hyperactivation of the PI3 kinase (PI3K)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, which has been identified in the Fmr1−/y brain65,66. The mTOR pathway stimulates translation of RPs along with other 5’TOP containing mRNAs. However, mutant models of Tuberous Sclerosis that exhibit hyperactive mTOR do not exhibit the same protein synthesis or mGluR-LTD phenotypes as seen in the Fmr1−/y model, and the role of this pathway in mGluR-LTD in WT is unclear67,68. Alternatively, FMRP loss may directly impact RP translation. Recent CLIP-seq data from CA1 pyr neurons has identified multiple RP transcripts as “low-binding” FMRP binding partners, suggesting a direct repression of RP synthesis60. Interestingly, FMRP has been reported to bind directly to the 80S ribosome69. The observed increase in ribogenesis may therefore arise in response to a change in the structural stability of the ribosome complex. Finally, it is possible that the excess ribogenesis in adult neurons is a compensatory response that arises from altered development imposed by an earlier loss of FMRP. Analysis of the translating population in adult neurons after acute FMRP loss and re-expression will be required to distinguish between these possibilities.

The identification of RPs as a major component of mRNA population translated upon stimulation of mGluR-LTD is somewhat surprising given that ribosome synthesis occurs in the nucleus. However, RP transcripts are frequently identified in the population of mRNAs localized to axons and dendrites37–39, and recent studies support the idea that these transcripts are locally translated to increase ribosome function40,41. The question of why new RPs would be needed to increase the functional capacity of ribosomes is intriguing given the abundance of existing RPs. Both Shigeoka et al. and Fusco et al. propose that the exchange of old or damaged RPs with new ones allows for the restoration of ribosome function without creating new ribosomes, which is energetically expensive. In support of this, both studies show that the RPs with the greatest rate of exchange are those at the outer cytosolic face of the ribosome, which are the most prone to oxidative stress. Our results confirm that these RPs are upregulated with DHPG as well (Supplementary Data 7). It is therefore possible that RP exchange is needed to maintain the protein synthesis supporting mGluR-LTD.

The effects of CX-5461 on mGluR-LTD and translation are more rapid than would be predicted from a disruption of ribosome synthesis, which is a slow process that occurs over days. Instead, these effects are consistent with the disruption of new RP synthesis and incorporation into existing ribosomes that occurs on a much shorter timescale40,70. In dendrites, the translation of RP transcripts was visualized with Puro-PLA labeling in as little as 5 min, and newly translated RPs can be quantified in mature ribosomes within 1–2 h41. This timescale is consistent with our results showing RP transcripts are elevated in the TRAP fraction of CA1 neurons by 30 min post DHPG, and that inhibiting RP production has an impact on LTD at 1 h. It is therefore possible that mGlu1/5 activation increases ribosome availability through RP synthesis and exchange, and this process is saturated in Fmr1−/y neurons that exhibit excessive ribogenesis. However, as we have not demonstrated ribosome exchange after mGlu1/5 activation we cannot be certain that this is the mechanism targeted by CX-5461 that disrupts LTD. Moreover, although we show that CX-5461 disrupts DHPG-stimulated RP translation, our model would be strengthened by a more targeted disruption of RP synthesis. Future work identifying the mechanisms by which new RP synthesis contributes to LTD expression is needed to fully understand the contribution to Fmr1−/y pathology.

Our results provide the first picture of the changing translation landscape in CA1 pyr neurons during LTD. A number of the targets altered suggest interesting mechanisms by which LTD is maintained. We find a significant upregulation of immediate early genes associated with induction of synaptic plasticity and LTD, including Arc, Npas4, and Egr135,36,71,72. Regulators of signaling cascades activated by group 1 mGluRs are also upregulated in the CA1-TRAP population including MAP kinase (mapkak3, mapk4) and Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (cdk5r2)73,74. Conversely, the reduced expression of proteins involved in synaptic signaling and structure such as cadherins (Cdh2, Cdh18, Celsr2, Celsr3) and protocadherins (Pcdh1, Pcdhac2, Pcdhgc5) is consistent with a reduction in synaptic strength75–77. Surprisingly, we find that several members of the Semaphorin-Plexin-Neuropilin signaling pathway (Nrp1, Plxna2, and 3), are downregulated with LTD, suggesting that decreased semaphorin signaling might play a role in the prolonged downregulation of synaptic strength78. In addition, transcripts encoding L-type calcium channel Cav1.2 and ryanodine receptors Ryr2 and Ryr3 are downregulated with DHPG in our CA1-TRAP-seq. These targets are involved in the calcium signaling that occurs in response to mGlu1/5 activation62, and it is possible that the downregulated expression of these proteins is involved in the saturation of further LTD seen after DHPG application34. Further investigation of these and other changes seen in by CA1-TRAP-seq will be interesting for understanding the mechanisms of mGluR-LTD.

Similar to our results, previous work in ref. 60 shows a reduction in the expression of long FMRP targets in the TRAP fraction of Fmr1−/y CA1 neurons isolated using a Ribotag system. However, the authors interpret these results as changes in transcript abundance rather than translation, reasoning that mRNAs not bound by ribosomes are quickly degraded. This is not inconsistent with our results, as we do see a small but significant reduction in long mRNAs including FMRP targets in the transcriptome of Fmr1−/y hippocampus after filtering for CA1 pyr neuron expression (Fig. 4c, i). The effects seen in the CA1-TRAP fraction are much greater in magnitude and persist after normalizing to the transcriptome, which leads us to conclude that changes in this fraction are indicative of translation. However, it is important to note that we cannot rule out the possibility that underlying changes in transcript abundance partially contribute to the changes we observe as we do not quantify the transcriptome of CA1 neurons specifically. Indeed, although our study focuses on the question of translation, recent ribosome profiling studies of Fmr1−/y brain have reported changes in the transcriptome including a reduction in the stability of long mRNAs and alternative splicing of SFARI targets in the Fmr1−/y transcriptome14,79. Although the contribution of these changes to synaptic or circuit function was not explored in these studies, the evolving picture suggests that there are multiple alterations in transcription, translation and RNA stability that ultimately contribute to neurological phenotypes in the Fmr1−/y brain.

Interestingly, a previous study in Drosophila shows that Fmr1 depletion results in a reduction in the translation of long mRNAs and expression of long proteins that is reminiscent of our findings80. Based on these results, the authors propose that FMRP is in fact an activator of translation for long mRNAs. In contrast, recent studies in refs. 13,61 suggest the reduced ribosome binding of long mRNAs in ribosome profiling from Fmr1−/y cortical lysates represents an increase in the translation of these targets due to a reduction in ribosome stalling by FMRP13,61. Although these studies do not include a corresponding analysis of the proteome, the prediction is an increase in the production of FMRP target proteins. Our study shows that there is a significant reduction in the expression of proteins encoded by long mRNAs including FMRP targets, which is consistent with a reduction in translation (Fig. 4i). However, as TRAP-seq data cannot distinguish between stalled and translating ribosomes, we cannot exclude the possibility that these mRNAs are rapidly elongated but subsequently degraded, resulting in a reduction in the steady-state proteome. What we can conclude is that the reduction seen in the TRAP is indicative of the reduced expression of the encoded proteins, which is significant for determining the impact on synaptic function. Indeed, several targets we identify as reduced in translation have been implicated in FX (i.e., Hcn2, Shank1, Pde2a) or autism (i.e., Cdh2, Cacna1c, Gabra5)81–84, and are consistent with the reductions in calcium channel function, GABA receptor activity and dendritic spine maturity that are seen in the Fmr1−/y mouse77,83,85. These results suggest that the synaptic pathologies caused by altered translation in FX are not due to an overall increase in protein production, but rather a shift in the composition of the translating mRNA pool that favors the production of metabolic proteins at the expense of longer synaptic transcripts. If so, the role of altered protein synthesis in the neuropathology of FX should not be viewed as a general over-production, but rather an imbalance that is driven by excessive ribogenesis (Fig. 6h). This would suggest a new conceptual framework for interpreting the role of altered translation in the development of synaptic pathology in FX.

Methods

Animals

Fmr1−/y (JAX 003025), Snap25-EGFP/Rpl10a (JAX 030273), and CA1-TRAP mice (JAX GM391-TRAP) were bred on a C57BL/6J background. Fmr1−/y and WT littermates were bred using Fmr1+/− females and JAX C57BL/6J males. Fmr1−/y-TRAP and WT-TRAP littermates were bred using Fmr1+/− females and TRAP homozygous males. All experiments were carried out using male littermate mice aged P25-32 with the experimenter blind to genotype. Mice were group-housed (six maximum) in conventional non-environmentally enriched cages with unrestricted food and water access and a 12 h light–dark cycle. Room temperature was maintained at 21 ± 2 °C with ambient humidity. All procedures were performed in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines and the UK Animal Welfare Act 2006, and were approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body at the University of Edinburgh.

Hippocampal slice preparation

Hippocampal slices were prepared from male littermate WT and Fmr1−/y mice (P25-32), in an interleaved fashion, with the experimenter blind to genotype as described previously4. Briefly, mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane and the hippocampus was rapidly dissected in ice-cold ACSF (124 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM dextrose, 1 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM CaCl2, saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2). Slices (500-μm thick) were prepared using a Stoelting Tissue Slicer and transferred into 32.5 °C ACSF (saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2) within 5 min. Slices were incubated in ACSF for 4 h to allow for recovery of protein synthesis4. For DHPG stimulation, hippocampal slices were stimulated with 50 µM S-3,5-Dihydroxyphenylglycine (S-DHPG) or vehicle (ddH2O) for 5 min in ACSF, then transferred to fresh ACSF for an additional 25 min (for TRAP and qPCR) or 55 min (for synaptoneurosome preparation and WB analysis). For CX-5461 experiments, slices were pre-incubated with vehicle or 200 nM CX-5461, and DHPG stimulation carried out with vehicle or 200 nM CX-5461 present throughout.

Proteomics

P2 preparation

Hippocampal slices were prepared and recovered from 5 WT and Fmr1−/y littermate pairs in an interleaved and blinded fashion exactly as previously described4. Slices from two mice per genotype were pooled and homogenized in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 plus 0.32 M sucrose supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). To isolate synapse-enriched fractions, homogenates were centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant (S1) re-centrifuged at 16,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting P2 pellet fractions were processed for MS analysis. Additional slices used for a separate study were prepared, stimulated, and processed for MS alongside the samples in this study, however, analysis of these additional samples was performed separately.

Filter-aided sample preparation (FASP)

In-solution digestion of proteins was done as previously described86. In brief, 20 μg of each sample were mixed with 75 μL 2% SDS, 1 mM Tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine and incubated at 55 °C for 1 h. Cysteines were blocked by adding 0.5 μL 200 mM methyl methanethiosulfonate and incubating 15 min at RT. After mixing with 200 μL 8 M urea in Tris pH 8.8, samples were transferred to Microcon-30 filter tubes (Millipore) and centrifuged at 14,000×g for 15 min at RT. Samples were washed four times with 200 μL 8 M urea and, subsequently, four times with 200 μL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate by centrifugation as stated above. Proteins were digested with 0.7 μg Trypsin/Lys-C Mix (MS grade, Promega) in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate overnight at 37 °C. Peptides were recovered by centrifugation. It was pooled with an additional wash with 200 μL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, dried in a speed vac and stored at −20 °C until used.

SWATH mass spectrometry analysis

Peptides were dissolved in 7 μL 2% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid solution containing iRT reference (Biognosys) and analyzed by micro LC MS/MS using an Ultimate 3000 LC system (Dionex, Thermo Scientific). A 5 mm Pepmap 100 C18 column (300 μm i.d., 5-μm particle size, Dionex) and a 200 mm Alltima C18 column (100 μm i.d., 3-μm particle size) were used to trap and fractionate the peptides, respectively. Acetonitrile concentration in 0.1% formic acid was increased linearly from 5 to 18% in 88 min, to 25% at 98 min, 40% at 108 min and to 90% in 2 min, at a flow rate of 5 μL/min. Peptides were electro-sprayed into the mass spectrometer with a micro-spray needle voltage of 5500 V. Each SWATH cycle consisted of a parent ion scan of 150 msec and 8 Da SWATH windows, with scan time of 80 msec, through 450–770 m/z mass range. The collision energy for each window was calculated for a 2+ ion centered upon the window (spread of 15 eV).

The data were analyzed using Spectronaut 13.7 with a spectral library previously generated from synaptosome preparations by data-dependent acquisition87. The cross-run normalization based on total peak areas was enabled and the peptide abundances were exported for further processing using the R language. Only peptides quantified in at least one group with high confidence were used, i.e., a Q-value ≤10−2 (allowing one outlier within each group). Limma R package version 3.40.6 (Bioconductor) was used to Loess normalize protein abundance (“normalizeCyclicLoess” function) and calculate empirical Bayes moderated t-statistics (“eBayes” and “topTable” functions). FDRs were computed with empirical null distribution from the data using the t statistics value using fdrtool R package version 1.2.16. T-statistics were used as gene rank. Significant targets were defined as P value < 0.05. For individual gene plots we used the variance stabilizing normalization (VSN) method from DEP R package version 1.6.1 to estimate protein abundance.

TRAP and RNA-seq

TRAP-Seq was performed on hippocampi isolated from "four littermate Fmr1−/y and wildtype mice hemizygous for Snap25-EGFP-L10a, as previously described23. For DHPG experiments, hippocampal slices were prepared from ten CA1-TRAP WT/Fmr1−/y littermate pairs. For CX-5461 experiments, hippocampal slices were prepared from 9 CA1-TRAP WT/Fmr1−/y littermate pairs, with slices incubated with vehicle or 200 nM CX-5461 for 30 min, stimulated with DHPG for 5 min (+/− CX-5461), and moved to fresh ACSF (+/− CX-5461) for an additional 25 min. For DHPG experiments, slices from two mice were pooled to obtain a paired vehicle and DHPG samples from the same animals. For CX + DHPG experiments, slices from three mice were pooled to obtain the paired vehicle, CX, DHPG and CX + DHPG conditions from the same animals. Samples were homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, 5 mM MgCl2, 150 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 100 μg/ml cycloheximide, RNase inhibitors and protease inhibitors), and centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 min. Supernatants were then extracted with 1% NP-40 and 1% DHPC on ice and centrifuged at 20,000×g for 20 min. The supernatant was incubated with streptavidin/protein L-coated Dynabeads bound to anti-GFP antibodies (HtzGFP-19F7 and HtzGFP-19C8, Memorial Sloan Kettering Centre) overnight at 4 °C with gentle mixing to isolate translating ribosome-bound mRNA. Anti-GFP beads were washed with high salt buffer (20 mM HEPES, 5 mM MgCl2, 350 mM KCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5 mM DTT, and 100 μg/ml cycloheximide) and RNA was eluted from all samples using PicoPure RNA isolation kit (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA with RIN > 7 was prepared for sequencing using the RNA-seq Ovation V2 kit (Nugen) or Smart-seq 4 low-abundance RNA kit (Takara) and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 or Novaseq 2 platform in collaboration with Oxford Genomics Centre.