Abstract

Health consequences that persist beyond the acute infection phase of COVID-19, termed post-COVID-19 condition (also commonly known as long COVID), vary widely and represent a growing global health challenge. Research on post-COVID-19 condition is expanding but, at present, no agreement exists on the health outcomes that should be measured in people living with the condition. To address this gap, we conducted an international consensus study, which included a comprehensive literature review and classification of outcomes for post-COVID-19 condition that informed a two-round online modified Delphi process followed by an online consensus meeting to finalise the core outcome set (COS). 1535 participants from 71 countries were involved, with 1148 individuals participating in both Delphi rounds. Eleven outcomes achieved consensus for inclusion in the final COS: fatigue; pain; post-exertion symptoms; work or occupational and study changes; survival; and functioning, symptoms, and conditions for each of cardiovascular, respiratory, nervous system, cognitive, mental health, and physical outcomes. Recovery was included a priori because it was a relevant outcome that was part of a previously published COS on COVID-19. The next step in this COS development exercise will be to establish the instruments that are most appropriate to measure these core outcomes. This international consensus-based COS should provide a framework for standardised assessment of adults with post-COVID-19 condition, aimed at facilitating clinical care and research worldwide.

Introduction

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 has placed immense pressure on global health systems and society over the past few years. COVID-19 can have a wide range of consequences, including symptoms that persist beyond the acute phase, affecting not only people who had severe disease, but also those who initially had mild disease. As the pandemic progresses, the number of people with lasting symptoms is rapidly increasing, adding to the health-care and societal burden of COVID-19. The prevalence of COVID-19 sequelae varies substantially between studies, with a few reporting that more than half of individuals admitted to hospital have symptoms lasting for at least 6 months after recovery from acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and some still having symptoms after 12 months.1, 2

Different names have been suggested for this phenomenon, including the widely used term long COVID, as well as post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection and post-COVID syndrome. WHO uses the term post-COVID-19 condition and a recent WHO consensus process defined it as a “condition that occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset of COVID-19 with symptoms that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. Common symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, cognitive dysfunction but also others and generally have an impact on everyday functioning. Symptoms may be new onset following initial recovery from an acute COVID-19 episode or persist from the initial illness. Symptoms may also fluctuate or relapse over time.”3

With a rapid increase in the number of studies investigating post-COVID-19 condition, many different outcomes are being evaluated. Such heterogeneity is a common problem across medical research and hampers the ability to compare research findings and conduct meta-analyses to inform evidence-based decisions, such as those regarding effective treatments. A classic example comes from schizophrenia research, in which, over a 60-year period, 2194 different scales were used to study the effectiveness of various interventions,4 with this heterogeneity prohibiting meaningful comparisons and meta-analyses of studies.

To address the issue of heterogeneity of outcomes and to help ensure that the most important outcomes are assessed consistently, the core outcome set (COS) concept is increasingly recognised,5 and sets of core outcomes have been developed in different fields. A COS is defined as “an agreed standardised collection of outcomes which should be measured and reported, as a minimum, in all trials for a specific clinical area”.6 The COS approach is also suitable for use in other types of research and clinical practice,5 and use of a recommended COS does not prohibit researchers from including other outcomes. The gold-standard approach to COS development has been outlined by the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) framework and consists of two stages to achieve agreement on: (1) the set of core outcomes that should be measured and reported; and (2) the instruments that are most appropriate to measure those outcomes.7, 8 Consensus regarding the importance of outcomes and instrument validity and applicability is typically reached within a large group of various stakeholders for whom the agreed outcomes matter most, including but not limited to people with lived experience and their carers, researchers, health-care professionals, methodologists, and public health experts; the COS approach also has relevance for other stakeholders, including research funding bodies and policy makers.

Key messages.

Rationale and approach

-

•

Post-COVID-19 condition (also known as long COVID) encompasses a broad range of sequelae that can persist for many months after infection with SARS-CoV-2

-

•

Substantial heterogeneity exists in the outcomes that are evaluated for research and clinical care focused on post-COVID-19 condition; there is an urgent need for consensus on a minimum set of key outcomes—a core outcome set (COS)—that should be measured and reported in post-COVID-19 condition to ensure consistency of care and to optimise comparisons and synthesis of research data

-

•

We sought to develop a COS for post-COVID-19 condition in adults for use in clinical research and practice worldwide via a consensus study that involved a literature review, a two-round online modified Delphi process (with 1535 participants, 53% of whom were patients with lived experience and their carers, from 71 countries, rating 26 different outcomes), and an online consensus meeting

Findings

-

•

Eleven outcomes reached consensus for the COS and should be measured and reported in adults with post-COVID-19 condition in clinical research and practice: fatigue; pain; post-exertion symptoms; work or occupational and study changes; survival; and functioning, symptoms, and conditions for each of cardiovascular, respiratory, nervous system, cognitive, mental health, and physical outcomes

-

•

Recovery, an outcome that was part of a previously published COS on COVID-19, was included a priori owing to its relevance to post-COVID-19 condition

Future directions and implications

-

•

An important next step is to achieve consensus on a minimum set of measurement instruments for this COS, balancing their validity and feasibility for use in clinical research and practice globally with continued inclusion of perspectives from people with lived experience and their carers, clinicians, and researchers

-

•

The use and reporting of this COS for adults with post-COVID-19 condition will be crucial to optimise and accelerate research, especially the development of evidence-based treatments, and to ensure consistent evaluation of these important outcomes in clinical settings

Involvement of people with lived experience is vital, and it has been shown previously that their preferred outcomes might differ from outcomes selected by researchers or clinicians. For example, as part of the Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials (OMERACT), people with rheumatoid arthritis identified the importance of fatigue;9 this unexpected suggestion had a substantial effect on future OMERACT work, and fatigue has subsequently been included as a core outcome measure in clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis management. OMERACT research has also shown that further development and implementation of the COS for rheumatoid arthritis resulted in an increase in the uptake of the COS over time, with 77% of rheumatoid arthritis drug trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov between 2002 and 2016 using this COS, indicating that consistency in outcomes measured across studies can be improved and appropriate outcome assessment achieved.10

There is an urgent need to develop a COS for post-COVID-19 condition to ensure that important outcomes are measured and reported in a consistent manner. To address this need, the Post-COVID-19 Condition Core Outcome Set (PC-COS) project was undertaken by an international, multidisciplinary group of experts and people with lived experience of long COVID and their carers under the auspices of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC), in collaboration with the COMET Initiative and WHO. Here, we report on the PC-COS project findings, which have led to development of a COS for post-COVID-19 condition in adults (≥18 years of age) that is intended for use in clinical research and practice.

Methods

The PC-COS project comprised three stages: (1) a literature review to identify post-COVID-19 outcomes for consideration by the participants; (2) a two-round online modified Delphi consensus process to rate the importance of the selected outcomes for a COS; and (3) an online interactive consensus meeting to review and agree upon the final COS. The study protocol was developed a priori and was approved by the UK Health Research Authority and by the South West–Cornwall and Plymouth Research Ethics Committee (REC number 21/SW/0109). The project was registered on the COMET database.11

Study groups and participants

DM, TN, DMN, and PRW oversaw the PC-COS project, identified and invited individuals with relevant expertise to form the core author group, and were responsible for the study methods and day-to-day project management. The core author group had expertise in methodology, various fields of clinical medicine and clinical research, psychology, epidemiology, public and global health, and public and patient engagement. A methods group (DM, TN, WDG, JP, NSc, NSe, FS, AT, DMN, and PRW) was established to develop and oversee the project methods. A PC-COS steering committee was established by DM, TN, DMN, and PRW in collaboration with the WHO Clinical Characterisation and Management Team (WDG, JVD, JP, and NSc); participants were identified and invited through expert networks including ISARIC, WHO, and the COMET Initiative, and support groups for people with lived experience. The PC-COS steering committee comprised 46 members from 13 countries, including health-care professionals, researchers representing a range of medical fields, methodologists, WHO representatives, and people with post-COVID-19 condition and their carers, and was actively involved in the design and conduct of this project (see appendix 1, pp 1–5, for further details of the PC-COS project steering committee members).

For the Delphi process, potential participants were identified from published studies, international organisations (eg, WHO, ISARIC), and patient organisations, and were invited to take part in the Delphi survey either by direct email from the study team or from relevant patient or professional organisations (appendix 1, pp 6–7). Patients attending long COVID clinical services were invited by email. Calls for participants were also disseminated via international and local patient organisations (appendix 1, pp 6–7) and large, private long COVID social media groups (predominantly on Facebook and VK), and relevant criteria for participation and contact details were provided on the PC-COS study website; individuals who responded to calls for participants were screened for eligibility before being registered for the survey.

Participants were classified into the following three stakeholder groups: people with post-COVID-19 condition and family members or caregivers; health-care professionals and researchers with post-COVID-19 condition; and health-care professionals and researchers without post-COVID-19 condition. Prerequisites for participation for health-care professionals and researchers were experience of treating people with post-COVID-19 condition and research in the field of post-COVID-19 condition, respectively.

Only participants who rated 50% or more of the outcomes in the first round of the Delphi process were invited to take part in the second round. Participants who had completed both rounds of the Delphi survey were eligible to participate in the consensus meeting and were asked to express their interest during the online Delphi process. These expressions of interest were considered to help to ensure international representation and that attendees were distributed across stakeholder groups.

Literature review

An extensive list of potential post-COVID-19 condition outcomes, to inform the COS consensus process, was created using data from a living systematic review,2 clinical trial protocols, and additional studies, including a survey led by people with lived experience of post-COVID-19 condition12 and references suggested by steering committee members. For the living systematic review, MEDLINE, CINAHL (EBSCO), Global Health (Ovid), the WHO Global Research Database on COVID-19, and LitCovid were searched for articles published in English from Jan 1, 2020, to March 17, 2021; further details of the search strategy used for the living systematic review, including search terms, are presented elsewhere.2 As part of the living systematic review, an additional search of Google Scholar was done on March 17, 2021, and the first 500 titles were screened. 2 We manually reviewed selected studies published after the systematic review search period, as well as other systematic reviews, narrative reviews, opinion papers, and relevant references cited in the identified articles. Clinical trial protocol data were extracted from ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and reviewed by one of four independent reviewers (JC, AK, CP, or NSe). All reported outcomes were extracted verbatim.

Unique outcomes from the list were classified into domains using an existing taxonomy by Dodd and colleagues,13 with iterative review and discussion via email and Zoom meetings first by the methods group, then by the core group, followed by the project steering committee to generate a list of outcomes for consideration in the first round of the modified Delphi consensus process. The final list of outcomes was approved by the steering committee.

An additional outcome, recovery, which was included in a previously published COS for COVID-19,14 was considered relevant to post-COVID-19 condition, and the core group, with agreement from the project steering committee, therefore decided that it should be automatically included in the final post-COVID-19 COS.

Delphi process and definitions

The consensus process included a two-round online modified Delphi process.6 In the first round, survey participants were asked to rate each outcome anonymously using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) scale,15 a nine-point scale that is commonly divided into three categories for COS projects: not important (1–3), important but not critical (4–6), and critically important (7–9). An “unable to rate” option and an option to add text-based comments were included for each outcome. The order in which outcomes were presented to participants in the Delphi process was randomised by domain categories. A free-text option to add suggestions for additional outcomes was also included. These suggestions were assessed by the core group for inclusion in the second Delphi round (outcomes that formed ≥1% of the total number of suggested outcomes were included). All outcomes from the first round were included in the second round.

In the second round of the Delphi process, for each outcome, participants were shown their original rating from the first round alongside overall ratings of the three stakeholder groups; they were then asked to again rate each outcome using the GRADE scale.

Consensus for inclusion of an outcome in the COS was defined a priori as 80% or more of participants in all stakeholder groups rating the outcome as critically important (GRADE rating 7–9). Consensus for exclusion of an outcome from the COS was defined as 50% or less of respondents in all stakeholder groups rating the outcome as critically important (GRADE rating 7–9). Outcomes that did not meet these criteria were considered for discussion at the consensus meeting (see below).

The Delphi materials and all participant information were available in English, Chinese, Russian, French, and Spanish. The Delphi survey was delivered using DelphiManager software.16 Further details of the Delphi consensus process are included in appendix 1 (p 8).

Consensus meeting

An online interactive consensus meeting was held using the Zoom platform. People with lived experience and their carers were also invited to attend a pre-meeting, led by the COMET Patient and Public Coordinator, to provide them with further information about the purpose of the COS, what to expect at the consensus meeting, and an opportunity to ask questions. The consensus meeting was conducted in English and chaired by an experienced independent facilitator. The meeting was structured using results from the second round of the Delphi process on the basis of outcomes that had reached the predefined definitions of consensus for inclusion or exclusion. Outcomes that met the consensus definition for inclusion according to the ratings of at least one stakeholder group, but not all groups, were prioritised for discussion. Outcomes that were rated as critically important by 50% or more, but less than 80%, of participants in each stakeholder group were also included for discussion. All arguments in favour of inclusion of the outcome were invited first, followed by arguments against inclusion. After discussion, participants were invited to confidentially rate the outcome again using the GRADE scale. Stakeholder groups rated outcomes separately and the same threshold as above was used to define inclusion—ie, 80% or more participants in all stakeholder groups rating the outcome as critically important (GRADE rating 7–9). Further details of the consensus meeting process are included in appendix 1 (p 8).

Data analysis

For all outcomes considered at each stage of the consensus process (the two Delphi rounds and the consensus meeting), we used descriptive statistics to show the overall scores of each stakeholder group for the three GRADE categories to determine whether the outcomes met the predefined criteria for inclusion or exclusion. It was agreed a priori that only responses from Delphi participants who rated at least 50% of outcomes would be included in the analysis. Free-text comments were translated from the French, Russian, Spanish, and Chinese surveys into English and collated and reviewed by the core group. Graphs displaying the distribution of ratings for each outcome, stratified by stakeholder group, were produced using R (version 4.0.2) and shown to participants in the second Delphi round.

Selection bias between the Delphi process and the consensus meeting was assessed by comparing the distribution of the mean overall scores from the second Delphi round between participants who attended the consensus meeting and those who did not.

Results

Literature review

The review of available evidence—ie, the living systematic review,2 clinical trial protocols, and additional papers, including a survey led by people with lived experience12—resulted in the identification of 259 studies or trial protocols on post-COVID-19 condition that were eligible for inclusion (appendix 1, pp 9–18); 198 individual outcomes (appendix 1, pp 19–26) were reported in these studies and trial protocols.

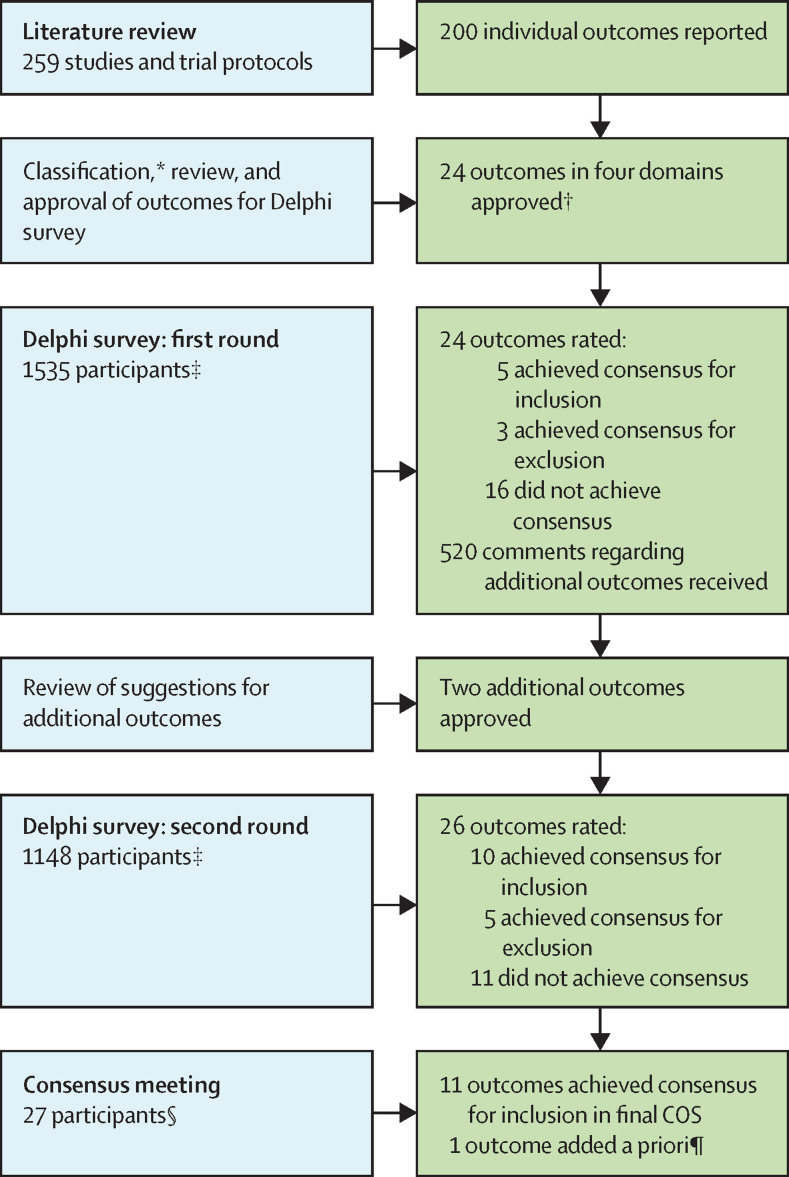

After classification of the outcomes13 and iterative review and discussion by the methods group, the core group, and the project steering committee, 24 outcomes (appendix 1, pp 27–28) were approved by the steering committee for consideration in the first round of the Delphi process. These 24 outcomes were in the following four domains: survival (one outcome); physiological or clinical (16 outcomes); life impact (five outcomes); and resource use (two outcomes). The COS development steps are summarised in the figure .

Figure.

Overview of the COS development process

For the Delphi survey, all outcomes from the first round were included in the second round. COMET=Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials. COS=core outcome set. *Outcomes were classified using COMET taxonomy.13 †Outcomes were classified into survival, physiological or clinical, life impact, and resource use outcomes. ‡Participants were classified into three stakeholder groups: people with post-COVID-19 condition and family members or caregivers, health-care professionals and researchers with post-COVID-19 condition, and health-care professionals and researchers without post-COVID-19 condition. §Participants were classified into two stakeholder groups: people with post-COVID-19 condition and family members or caregivers, and health-care professionals and researchers without post-COVID-19 condition. ¶Additional outcome was part of a previously published COS for COVID-19.14

Delphi process

The first round of the online Delphi process took place from Aug 5 to Sept 13, 2021. 1692 individuals registered to take part in the study and 1535 participants (91%) from 71 countries completed the first round (ie, rated 50% or more of the 24 outcomes). Of these 1535 participants who were invited to take part in the second round of the Delphi process, 1148 (75%) from 59 countries rated 50% or more of the outcomes in this subsequent round. Demographic characteristics, by Delphi round, are presented in table 1 . Further details of Delphi participants are presented in appendix 1 (pp 29–34).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in the Delphi consensus process

| Delphi round 1 (n=1535) | Delphi round 2 (n=1148) | |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder group, n (%) | ||

| People with post-COVID-19 condition and family members or caregivers | 810 (53) | 579 (50) |

| Health-care professionals and researchers with post-COVID-19 condition | 169 (11) | 126 (11) |

| Health-care professionals and researchers without post COVID-19 condition | 556 (36) | 443 (39) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 392 (26) | 301 (26) |

| Female | 1135 (74) | 841 (73) |

| Other | 7 (<1) | 5 (<1) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||

| 18–29 years | 89 (6) | 57 (5) |

| 30–39 years | 404 (26) | 299 (26) |

| 40–49 years | 565 (37) | 423 (37) |

| 50–59 years | 343 (22) | 262 (23) |

| 60–69 years | 119 (8) | 94 (8) |

| 70–79 years | 15 (1) | 13 (1) |

| Geographical area, n (%)* | ||

| Asia | 95 (6) | 60 (5) |

| Africa | 31 (2) | 21 (2) |

| Australasia | 29 (2) | 24 (2) |

| Europe | 1015 (66) | 763 (66) |

| North America | 287 (19) | 226 (20) |

| South America | 77 (5) | 53 (5) |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | ||

| White | 975 (64) | 753 (66) |

| South Asian | 68 (4) | 47 (4) |

| Hispanic, Latino, Spanish | 350 (23) | 246 (21) |

| East Asian, Pacific Islander | 43 (3) | 33 (3) |

| Indigenous peoples | 4 (<1) | 4 (<1) |

| Black | 25 (2) | 16 (1) |

| Middle Eastern, North African | 12 (1) | 10 (1) |

| Other | 58 (4) | 39 (3) |

Not all percentages add up to 100% owing to rounding.

One participant in each Delphi round did not specify their location.

At the end of the first round of the Delphi process, participant ratings suggested that five of the 24 outcomes should be included in the COS, three outcomes should be excluded, and criteria were not met for 16 outcomes (table 2 ; appendix 1, pp 35–41).

Table 2.

Summary of Delphi voting on outcomes stratified by domain

| Delphi round 1 | Delphi round 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Survival | ||

| Survival | No consensus | No consensus: for discussion* |

| Physiological or clinical outcomes | ||

| Cardiovascular functioning, symptoms, and conditions | No consensus | Include |

| Endocrine and metabolic functioning, symptoms, and conditions | No consensus | No consensus: exclude† |

| Hearing-related functioning, symptoms, and conditions | No consensus | Exclude |

| Gastrointestinal functioning, symptoms, and conditions | No consensus | No consensus: exclude† |

| Fatigue or exhaustion | Include | Include |

| Pain | No consensus | Include |

| Sleep-related functioning, symptoms, and conditions | No consensus | No consensus: for discussion* |

| Nervous system functioning, symptoms, and conditions | No consensus | Include |

| Cognitive functioning, symptoms, and conditions | Include | Include |

| Mental functioning, symptoms, and conditions | Include | Include |

| Taste or smell-related functioning, symptoms, and conditions | No consensus | Exclude |

| Kidney and urinary-related functioning, symptoms, and conditions | No consensus | No consensus: exclude† |

| Reproductive and sexual functioning, symptoms, and conditions | Exclude | Exclude |

| Respiratory functioning, symptoms, and conditions | Include | Include |

| Skin, hair or nail-related functioning, symptoms, and conditions | Exclude | Exclude |

| Post-exertion symptoms | No consensus | Include |

| Eye symptoms and conditions | NA | No consensus: exclude† |

| Muscle and joint symptoms and conditions | NA | No consensus: for discussion* |

| Life impact outcomes | ||

| Physical functioning, symptoms, and conditions | No consensus | Include |

| Social role—functioning and relationship problems | Include | No consensus: for discussion‡ |

| Work or occupational and study changes | No consensus | Include |

| Stigma | No consensus | Exclude |

| Satisfaction with life or personal enjoyment | Exclude | No consensus: for discussion* |

| Resource use outcomes | ||

| Health-care resource use | No consensus | No consensus: for discussion* |

| Family or carer burden | No consensus | No consensus: for discussion‡ |

All outcomes from round 1 were included in round 2, regardless of ratings in round 1. NA=not applicable (outcomes were added after the first Delphi round).

Outcome was given an overall GRADE rating of 7–9 by at least one, but not all, stakeholder groups and was therefore prioritised for discussion at the consensus meeting.

Outcome did not reach the required threshold for inclusion in all three stakeholder groups and was therefore excluded.

Outcome was given an overall rating of 7–9 by 65% or more participants in all three stakeholder groups and was therefore included for discussion at the consensus meeting.

A total of 520 free-text responses regarding additional outcomes were received and reviewed by the core group, two of which met criteria for inclusion in the second round of the Delphi process: eye symptoms and conditions, suggested by 13 participants, and muscle and joint symptoms and conditions, suggested by 16 participants. These two new outcomes were added to the 24 original outcomes, making a total of 26 outcomes for rating in the second round of the Delphi process.

The second Delphi round took place from Oct 1 to Nov 5, 2021, and 1148 participants rated the 26 outcomes. Following this process, 10 outcomes met the definition for inclusion. Eight of these outcomes were in the physiological or clinical outcomes domain (fatigue or exhaustion; pain; cardiovascular functioning, symptoms, and conditions; respiratory functioning, symptoms, and conditions; nervous system functioning, symptoms, and conditions; cognitive functioning, symptoms, and conditions; mental functioning, symptoms, and conditions; post-exertion symptoms) and two outcomes were in the life impact outcomes domain (work or occupational and study changes; physical functioning, symptoms, and conditions). Five outcomes met the definition for exclusion. The following five outcomes were given an overall GRADE rating of 7–9 by at least one, but not all, stakeholder groups: survival; sleep-related functioning, symptoms, and conditions; muscle and joint symptoms and conditions; satisfaction with life or personal enjoyment; and health-care resource use. These five outcomes were discussed at the subsequent consensus meeting. Six outcomes did not reach the required threshold for inclusion in all three stakeholder groups. However, two of these outcomes (social role—functioning and relationship problems; family or carer burden) were rated 7–9 by 65% or more participants in all three stakeholder groups and were therefore also discussed at the consensus meeting (appendix 1, pp 35–41), making a total of seven outcomes to be discussed.

Response rates in the second round, compared with those in the first round, were 71% for the group with post-COVID-19 condition and family members or caregivers, 75% for health-care professionals and researchers with post-COVID-19 condition, and 80% for health-care professionals and researchers without post-COVID-19 condition (appendix 1, p 42). We found no evidence of selection bias: the average Delphi round-2 scores were similar between participants who attended the consensus meeting (7·39) and those who did not attend the meeting (7·27).

Consensus meeting

The online consensus meeting took place on Nov 22, 2021. 30 participants were invited to the consensus meeting, of whom 27 attended: eight people with post-COVID-19 condition and family members or caregivers; five health-care professionals and researchers with post-COVID-19 condition; and 14 health-care professionals and researchers without post-COVID-19 condition.

Owing to the small number of attendees in the group of health-care professionals and researchers with post-COVID-19 condition, for the purposes of consensus voting at the meeting, the participants from this group self-selected allocation into one of the other two groups. Furthermore, three participants were unable to attend the full meeting. Therefore, 12 people in the group with post-COVID-19 condition and family members or caregivers and 12 people in the group of health-care professionals and researchers participated in the rating process. The participants who attended the consensus meeting are described in appendix 1 (p 43).

The seven outcomes were discussed in the following order: survival; sleep-related functioning, symptoms, and conditions; muscle and joint symptoms and conditions; satisfaction with life or personal enjoyment; social role—functioning and relationship problems; family or carer burden; and health-care resource use. After discussion and voting, only one outcome—survival—met the predefined consensus definition for inclusion, with 10 of the 12 participants with post-COVID-19 condition (83%) and 11 of the 12 health-care professionals and researchers (92%) rating it as critically important (GRADE rating 7–9). Survival was therefore added to the ten previously agreed outcomes for inclusion in the COS, along with recovery, which was part of a previously published COS for COVID-19,14 making a total of 12 outcomes (panel ). Results from the Delphi process and the consensus meeting are included in appendix 1 (p 44), and a full report of the consensus meeting is provided in appendix 2.

Panel. COS for adults with post-COVID-19 condition.

Physiological or clinical outcomes

-

1

Cardiovascular functioning, symptoms, and conditions

-

2

Fatigue or exhaustion

-

3

Pain

-

4

Nervous system functioning, symptoms, and conditions

-

5

Cognitive functioning, symptoms, and conditions

-

6

Mental functioning, symptoms, and conditions

-

7

Respiratory functioning, symptoms, and conditions

-

8

Post-exertion symptoms

Life impact outcomes

-

9

Physical functioning, symptoms, and conditions

-

10

Work or occupational and study changes

Survival

-

11

Survival

Outcome from previous COS

-

12

Recovery*

COS=core outcome set.

Discussion

Here, we report the findings of a large, rigorous international consensus study aimed at developing a COS for post-COVID-19 condition that is intended for use with adults (≥18 years of age) in clinical research and practice settings. Eleven outcomes achieved the predefined consensus definition for inclusion in the COS: fatigue or exhaustion; pain; post-exertion symptoms; work or occupational and study changes; survival; and functioning, symptoms, and conditions for each of cardiovascular, respiratory, nervous system, cognitive, mental health, and physical outcomes. It was also agreed before the Delphi process that recovery should be included as an outcome because it was part of a previously published COS on COVID-1914 and has relevance to post-COVID-19 condition.

A COS is defined as an agreed minimum set of outcomes that should be measured and reported in all studies in a specific field, with a focus on outcomes that matter most to relevant stakeholders. Because the recommendation is for use of a minimum set of outcomes, the COS approach does not prohibit researchers from including other outcomes. Previous studies on post-COVID-19 condition have focused on outcomes that were considered to be important by investigators but might not have the same level of importance for those who live with the condition—a key consideration for future research in this field. In Europe17 and the USA,18 there has been major financial investment in long COVID research, with US$1·2 billion allocated in the USA alone. Therefore, COS development is an urgent priority to optimise the findings of the rapidly increasing number of studies by ensuring that they can be compared and synthesised and that outcomes will be relevant to all stakeholders.

International studies, predominantly focused on the more acute stage of COVID-19, have provided recommendations for core outcomes and associated measures—eg, a novel single-item longer-term measure of recovery—following an international survey of more than 9000 respondents from 111 countries, including nearly 800 people with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 and their family members, and more than 3500 members of the general public.14, 19 The COMET Initiative brought together COS developers to agree a so-called meta-COS for acute COVID-1920 to ensure accessibility and harmonisation of the available outcome sets. In addition to the single-item novel recovery measure, the development of a COS for long COVID could build upon successful initiatives in other fields that might have relevance. For example, core outcome measures developed for clinical research in survivors of acute respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome are relevant to studies of survivors of critical COVID-19 disease.21

Consensus regarding the importance of outcomes is often achieved using a modified Delphi process with a group of relevant stakeholders, including researchers, health-care professionals, methodologists, and people with lived experience and their caregivers. In this project, involvement of people with lived experience and their carers was ensured throughout the COS development exercise, with this group comprising 64% of the participants (53% patients and their carers, 11% health-care professionals and researchers with post-COVID-19 condition). The consensus process included participants from 71 countries, under the auspices of ISARIC, in collaboration with the COMET Initiative and WHO, to increase generalisability and worldwide applicability of the project's findings.

The complexity and multidimensionality of post-COVID-19 condition is reflected in numerous studies reporting involvement of many organ systems. It has been hypothesised that different post-COVID-19 condition phenotypes might exist, although exact causes, management, and outcomes are not known. The WHO definition of post-COVID-19 condition3 includes the most prevalent symptoms, such as fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive dysfunction, which generally have an effect on everyday functioning. Fluctuating or relapsing symptoms are also commonly reported.22 As reflected in the WHO definition, people with post-COVID-19 condition can have many other symptoms. Eight of the eleven consensus-based outcomes in the COS presented here are in the physiological or clinical outcomes domain and cover all of the most prevalent symptoms reported in existing research. This COS complements the WHO definition because both are aiming for harmonisation of clinical research and practice for long COVID. The WHO definition provides a standardised term for post-COVID-19 condition, while the COS identifies the minimum outcomes that should be measured in all research studies and clinical practice.

There was general agreement across stakeholder groups for most outcomes. However, for the muscle and joint symptoms and conditions outcome, during the consensus meeting, 92% of people with post-COVID-19 condition and family members or caregivers scored this outcome as critically important (GRADE rating 7–9), whereas only 25% of health-care professionals and researchers rated this outcome as critically important, reflecting distinct perspectives of the stakeholder groups. Although muscle and joint symptoms and conditions did not meet the predefined consensus definition for inclusion in the COS, the importance of this outcome was acknowledged by both stakeholder groups (100% of people with post-COVID-19 condition and family members or caregivers, and 92% of health-care professionals and researchers rated it as important [GRADE rating 4–6] or critically important [GRADE rating 7–9]; appendix 2), and the high importance of this outcome to people with post-COVID-19 condition suggests that it should be considered by researchers and clinicians. As noted, the absence of a particular outcome in the COS does not imply that the outcome is not important.

Our study has several limitations. First, although a broad range of individuals residing in different geographical locations were involved in the Delphi consensus process, nearly two-thirds of the participants were white, and the majority of the respondents resided in the UK, USA, or Spain. Male participants were under-represented in the Delphi process. Both imbalances could potentially result in a lack of external validity or generalisability. Second, only a small number of Delphi participants was involved in the consensus meeting and their views might not be representative of the range of opinions on this topic. This is an accepted and common limitation of all studies that use Delphi methodology. Third, the number of individuals in the group of health-care professionals and researchers with post-COVID-19 condition was insufficient to retain them in a separate group for the consensus meeting. However, this limitation is unlikely to have affected the outcome of the Delphi process. Fourth, owing to the importance of COS development to public health and research in the field, it was necessary to expedite the process, and data regarding chronicity, time from diagnosis, and socioeconomic status of the participants have not been collected, but might be associated with selection bias. However, detailed information collection on study participants is uncommon in Delphi-based research. As per the WHO definition of post-COVID-19 condition, “post-COVID-19 condition occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection”. Thus, individuals with both laboratory-confirmed and suspected COVID-19 were invited to participate, but some individuals with probable COVID-19 might not have been infected.23 It should also be acknowledged that this COS project focuses on adults. Children and young people can also develop post-COVID-19 condition, although data are still emerging. The need for development of a COS for children with post-COVID-19 condition has been highlighted previously24, 25 and was raised during the consensus meeting. Although this study excludes the paediatric population, we acknowledge the importance of COS development for this age group.24

Several future challenges relating to the COS developed here for post-COVID-19 condition need to be considered. Importantly, implementation and uptake of COS varies across clinical conditions.26 Known barriers to uptake of COS include lack of validated measurement instruments, lack of involvement of key stakeholder groups in COS development, and lack of awareness of the COS.26 To help mitigate such issues, our project was undertaken in collaboration with major organisations such as ISARIC, COMET, and WHO to ensure wide dissemination of the study results and applicability of the COS across different geographical areas. Moreover, this project team has been actively engaging with additional large initiatives and investigators in the field to seek input and share study results. Recommendations for dissemination provided by previous COS stakeholders are also being followed to assist further with this aim.27 The optimal timepoints for outcome assessment are yet to be established and, although a minimum set of timepoints is required for harmonisation (eg, 3, 6, and 12 months), additional timepoints should be considered to develop a better understanding of changes in post-COVID-19 condition patterns over time. We recommend that the first follow-up assessment for post-COVID-19 condition take place at 3 months after the onset of COVID-19 to be consistent with the WHO clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition.3

Future directions also include achieving consensus on the measurement instruments that are most appropriate for each outcome in the COS, which is needed to enable greater consistency and comparability across research studies. This important objective will be achieved on completion of the second phase of the project, which will continue to consider perspectives from clinicians, researchers, and people with lived experience and their carers, and will also aim to balance the validity and feasibility of relevant potential measurement instruments in global research and clinical settings. Although twelve outcomes is a large number for a typical COS, it is understandable and expected for a new condition such as post-COVID-19 condition and can enable harmonisation in the early stages of research; once the condition is better understood, the COS could be revised and the number of outcomes reduced to improve feasibility. Finally, with millions of children and young people having SARS-CoV-2 infection, potential long-term adverse effects in this age group would result in a substantial burden to health-care services.28 A COS for post-COVID-19 condition in children and young people is urgently needed to ensure harmonisation of international clinical research and practice.24, 25, 29 The PC-COS Pediatric project has been set up with this aim and the COS development process was launched in January 2022.25

With millions of people affected by COVID-19, even a small proportion developing post-COVID-19 condition will result in detrimental effects on health-care systems and society, with many people in need of long-term follow-up, management, and support.30 Integration into clinical practice and research of a COS that is relevant to people with lived experience of post-COVID-19 condition is an urgent priority. The PC-COS project aimed to address this need: we have established a COS that is the result of consensus among clinicians, researchers, and people with lived experience and their carers, and is important to other stakeholder groups, including research funding bodies and policy makers, to ensure that post-COVID-19 condition research is optimised through inclusion of core outcomes. The next step in this COS development exercise will be to establish the instruments that are most appropriate to measure these core outcomes. Ultimately, use of this COS will ensure consistent evaluation of relevant outcomes in clinical settings, and should help to advance research, especially the development of evidence-based treatments, and thus clinical care for the rapidly increasing group of people with persistent symptoms after acute COVID-19.

Declaration of interests

DM is a co-chair of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) Global Paediatric Long COVID working group and a member of the ISARIC working group on long-term follow-up in adults. CA reports grants or contracts from Dr Wolff Group, Bionorica, and The European Cooperation in Science and Technology; consulting fees from the Dr Wolff Group, Bionorica, and Sanofi-Aventis Germany; and honoraria from AstraZeneca. SLG is the project coordinator of the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) Initiative. PRW is chair of the COMET Management Group. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

There was no funding for the first stage of the Post-COVID-19 Condition Core Outcome Set (PC-COS) study; the second stage of the PC-COS study is funded by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR; grant COV-LT2-0072). DM has received grants from the British Embassy in Moscow, the NIHR, and the Russian Foundation for Basic Research. TN and PRW have received funding from the NIHR. We thank all participants of the consensus development process, and particularly the people with lived experience of post-COVID-19 condition and their carers (a full list of participants wishing to be acknowledged is included in appendix 1, pp 45–52); WHO for their collaboration; the translators who provided translation of all English materials to four additional languages; Marjorie Williamson, Valeria Sluzhevskaya, Guo Xiao Yuan, and Ilya Kalinin for their assistance with translation; Aleksandra Pokrovskaya and Nile Saunders for their help with preparation of participant information sheets; Mike Clarke for his work as an independent facilitator of the online interactive consensus meeting; Heather Barrington, Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) Patient and Public Coordinator, for delivering the consensus pre-meeting for people with post-COVID-19 condition and their carers; the COMET People and Patient Participation, Involvement and Engagement working group; the COMET Management Group; and Sara Brookes for developing and sharing the slide set used in the pre-meeting. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium, the NIHR, or WHO.

Contributors

DM and TN conceived the idea for the study. PRW led the methods group. DM, TN, PRW, and DMN designed the study protocol and were responsible for the day-to-day running of the project. NSe, CP, AK, and JC did the literature review, identified outcomes, and categorised outcomes for inclusion in the online Delphi surveys. NSe coordinated the data revision process. NH, SLG, and NSe developed the online Delphi surveys and contributed to the day-to-day management of the project. DM, TN, WDG, NSc, JP, PO, CA, AT, JS, DMN, and PRW participated in discussions about project methods throughout the duration of the project. SLG and NH did the data analysis and organised the consensus meeting. JP coordinated the translation of study materials and communication with WHO. JVD provided the lead for WHO administrative aspects of the study. FS and AA engaged people with lived experience perspectives throughout the study. DM drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors were able to access the study data. DM, TN, DMN, and PRW accessed and verified all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Outcome was included in a previously published COS for COVID-1914 and, owing to its relevance to post-COVID-19 condition, was automatically included in this COS.

Contributor Information

PC-COS project steering committee:

Alla Guekht, Malcolm “Calum” G. Semple, John O. Warner, Louise Sigfrid, Janet T. Scott, Audrey DunnGalvin, Jon Genuneit, Danilo Buonsenso, Manoj Sivan, Bob Siegerink, Frederikus A. Klok, Sergey Avdeev, Charitini Stavropoulou, Melina Michelen, Olalekan Lee Aiyegbusi, Melanie Calvert, Sarah E. Hughes, Shamil Haroon, Laura Fregonese, Gail Carson, Samuel Knauss, Margaret O'Hara, John Marshall, Margaret Herridge, Srinivas Murthy, Theo Vos, Sarah Wulf Hanson, Ann Parker, Kelly K. O'Brien, Andrea Lerner, Jennifer R. Chevinsky, Elizabeth R. Unger, Robert W. Eisinger, Catherine L. Hough, Sharon Saydah, Jennifer A. Frontera, Regis Goulart Rosa, Bin Cao, Shinjini Bhatnagar, Ramachandran Thiruvengadam, Archana Seahwag, Anouar Bouraoui, Maria Van Kerkhove, Tarun Dua, Pryanka Relan, and Juan Soriano Ortiz

Supplementary Materials

References

- 1.Huang L, Yao Q, Gu X, et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398:747–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michelen M, Manoharan L, Elkheir N, et al. Characterising long COVID: a living systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, Relan P, Diaz JV, WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:e102–e107. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00703-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyar J, Adams CE. Content and quality of 10,000 controlled trials in schizophrenia over 60 years. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:226–229. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gargon E, Gorst SL, Matvienko-Sikar K, Williamson PR. Choosing important health outcomes for comparative effectiveness research: 6th annual update to a systematic review of core outcome sets for research. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, et al. The COMET handbook: version 1.0. Trials. 2017;18(suppl 3):280. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkham JJ, Davis K, Altman DG, et al. Core Outcome Set–STAndards for Development: the COS-STAD recommendations. PLoS Med. 2017;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prinsen CA, Vohra S, Rose MR, et al. How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set” – a practical guideline. Trials. 2016;17:449. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1555-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirwan J, Heiberg T, Hewlett S, et al. Outcomes from the Patient Perspective Workshop at OMERACT 6. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:868–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkham JJ, Clarke M, Williamson PR. A methodological approach for assessing the uptake of core outcome sets using ClinicalTrials.gov: findings from a review of randomised controlled trials of rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ. 2017;357 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munblit D, Nicholson T, Williamson P, et al. Core outcome measures for post-Covid condition/long Covid. https://www.comet-initiative.org/Studies/Details/1847

- 12.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dodd S, Clarke M, Becker L, Mavergames C, Fish R, Williamson PR. A taxonomy has been developed for outcomes in medical research to help improve knowledge discovery. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;96:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong A, Baumgart A, Evangelidis N, et al. Core outcome measures for trials in people with coronavirus disease 2019: respiratory failure, multiorgan failure, shortness of breath, and recovery. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:503–516. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.COMET DelphiManager. http://www.comet-initiative.org/delphimanager

- 17.National Institute for Health Research £19.6 million awarded to new research studies to help diagnose and treat long COVID. July 18, 2021. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/news/196-million-awarded-to-new-research-studies-to-help-diagnose-and-treat-long-covid/28205

- 18.National Institutes of Health NIH launches new initiative to study “long COVID”. Feb 23, 2021. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/who-we-are/nih-director/statements/nih-launches-new-initiative-study-long-covid

- 19.Tong A, Elliott JH, Azevedo LC, et al. Core outcomes set for trials in people with coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:1622–1635. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) Initiative Core outcome set developers' response to COVID-19. April 2021. https://www.comet-initiative.org/studies/details/1538

- 21.Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, et al. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors. An international modified Delphi consensus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1122–1130. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0372OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown DA, O'Brien KK. Conceptualising long COVID as an episodic health condition. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matta J, Wiernik E, Robineau O, et al. Association of self-reported COVID-19 infection and SARS-CoV-2 serology test results with persistent physical symptoms among French adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:19–25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munblit D, Sigfrid L, Warner JO. Setting priorities to address research gaps in long-term COVID-19 outcomes in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:1095–1096. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munblit D, Buonsenso D, Sigfrid L, Vijverberg SJH, Brackel CLH. Post-COVID-19 condition in children: a COS is urgently needed. Lancet Respir Med. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00211-9. published online June 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes KL, Clarke M, Williamson PR. A systematic review finds core outcome set uptake varies widely across different areas of health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;129:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akinremi A, Turnbull AE, Chessare CM, Bingham CO, 3rd, Needham DM, Dinglas VD. Delphi panelists for a core outcome set project suggested both new and existing dissemination strategies that were feasibly implemented by a research infrastructure project. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;114:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munblit D, Simpson F, Mabbitt J, Dunn-Galvin A, Semple C, Warner JO. Legacy of COVID-19 infection in children: long-COVID will have a lifelong health/economic impact. Arch Dis Child. 2022;107:e2. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2021-321882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munblit D, Nicholson TR, Needham DM, et al. Studying the post-COVID-19 condition: research challenges, strategies, and importance of core outcome set development. BMC Med. 2022;20:50. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02222-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nature Medicine Meeting the challenge of long COVID. Nat Med. 2020;26 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.