Key Points

Question

Among African American individuals who are daily smokers, does the addition of varenicline to counseling improve rates of smoking cessation compared with counseling alone?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 500 African American adults, counseling plus 12 weeks of varenicline treatment, compared with counseling plus placebo, showed a statistically significant improvement in rates of 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence at week 26 (15.7% vs 6.5%).

Meaning

The findings support the use of varenicline added to counseling for promoting smoking cessation among African American adults who are daily smokers of all smoking levels.

Abstract

Importance

African American smokers have among the highest rates of tobacco-attributable morbidity and mortality in the US, and effective treatment is needed for all smoking levels.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of varenicline vs placebo among African American adults who are light, moderate, and heavy daily smokers.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Kick It at Swope IV (KIS-IV) trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted at a federally qualified health center in Kansas City. A total of 500 African American adults who were daily smokers of all smoking levels were enrolled from June 2015 to December 2017; final follow-up was completed in June 2018.

Interventions

Participants were provided 6 sessions of culturally relevant individualized counseling and were randomized (in a 3:2 ratio) to receive varenicline (1 mg twice daily; n = 300) or placebo (n = 200) for 12 weeks. Randomization was stratified by sex and smoking level (1-10 cigarettes/d [light smokers] or >10 cigarettes/d [moderate to heavy smokers]).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was salivary cotinine–verified 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence at week 26. The secondary outcome was 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence at week 12, with subgroup analyses for light smokers (1-10 cigarettes/d) and moderate to heavy smokers (>10 cigarettes/d).

Results

Among 500 participants who were randomized and completed the baseline visit (mean age, 52 years; 262 [52%] women; 260 [52%] light smokers; 429 [86%] menthol users), 441 (88%) completed the trial. Treating those lost to follow-up as smokers, participants receiving varenicline were significantly more likely than those receiving placebo to be abstinent at week 26 (15.7% vs 6.5%; difference, 9.2% [95% CI, 3.8%-14.5%]; odds ratio [OR], 2.7 [95% CI, 1.4-5.1]; P = .002). The varenicline group also demonstrated greater abstinence than the placebo group at the end of treatment week 12 (18.7% vs 7.0%; difference, 11.7% [95% CI, 6.0%-17.7%]; OR, 3.0 [95% CI, 1.7-5.6]; P < .001). Smoking abstinence at week 12 was significantly greater for individuals receiving varenicline compared with placebo among light smokers (22.1% vs 8.5%; difference, 13.6% [95% CI, 5.2%-22.0%]; OR, 3.0 [95% CI, 1.4-6.7]; P = .004) and among moderate to heavy smokers (15.1% vs 5.3%; difference, 9.8% [95% CI, 2.4%-17.2%]; OR, 3.1 [95% CI, 1.1-8.6]; P = .02), with no significant smoking level × treatment interaction (P = .96). Medication adverse events were generally comparable between treatment groups, with nausea reported more frequently in the varenicline group (163 of 293 [55.6%]) than the placebo group (90 of 196 [45.9%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among African American adults who are daily smokers, varenicline added to counseling resulted in a statistically significant improvement in the rates of 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence at week 26 compared with counseling and placebo. The findings support the use of varenicline in addition to counseling for tobacco use treatment among African American adults who are daily smokers.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02360631

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial examines the efficacy of varenicline in combination with counseling for smoking cessation among Black adults who are daily smokers.

Introduction

Black adults in the US have higher rates of smoking-related morbidity and mortality compared with White adults, despite having comparable smoking prevalence and smoking fewer cigarettes per day.1,2,3,4 Although they report greater interest in quitting, Black smokers are less likely than White smokers to be advised to quit or achieve sustained smoking abstinence and have been underrepresented in tobacco treatment research.1,5 Advancing treatment for Black smokers must include light smokers, because more than 65% of Black individuals who smoke use 10 or fewer cigarettes per day.2,6 Light smokers report nicotine dependence and experience substantial tobacco-related disease,7,8,9,10 but have been largely excluded from smoking cessation clinical trials.11,12 Clinical practice guidelines articulate the need for research addressing treatment for light smokers and for Black smokers.12,13

Varenicline is considered one of the most effective smoking cessation aids; although it is approved for all levels of smoking, efficacy data come from studies of predominately White smokers who used at least 10 cigarettes per day.14 In the largest randomized trial to date, varenicline, bupropion, and a nicotine patch produced significantly greater abstinence than placebo among White smokers, but only varenicline produced significantly greater long-term abstinence compared with placebo among Black smokers.15 Light smokers were not included, limiting conclusions about the efficacy of varenicline for Black individuals who are light smokers.

The current study was the fourth of the Kick It at Swope (KIS-IV) series of clinical trials to advance treatment for African American smokers. Individuals receiving counseling and 12 weeks of varenicline were hypothesized to have significantly higher biochemically confirmed smoking abstinence at week 26 compared with those receiving counseling and placebo. A secondary aim was to examine treatment effects independently in light and moderate to heavy smokers at the end of treatment.

Methods

Trial Design

This study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of varenicline in combination with counseling for smoking cessation among African American daily smokers. Participants provided written consent. Study procedures were approved by the human subjects committee at the University of Kansas Medical Center; the complete study protocol and statistical analysis plan are included in Supplement 1. Recruitment was active between June 2015 and December 2017, and final follow-up was completed in June 2018.

Participants

The study was conducted at Swope Health, a federally qualified health center in Kansas City, Missouri. A community advisory board supported study recruitment and implementation. Recruitment in the Kansas City metropolitan area included concurrent clinic- and community-based efforts (eg, physician referral from 3 regional medical centers, television, radio, social media, community health fairs). Eligible individuals self-identified as African American or Black, were 18 years or older, smoked at least 1 cigarette per day for at least 25 of the past 30 days, and were interested in stopping smoking. Exclusion criteria included past allergic reaction to varenicline; past-month use of varenicline, bupropion, or nicotine replacement to stop smoking; past-month use of tobacco products other than cigarettes, including electronic nicotine delivery systems; past-month acute cardiovascular event; past-year history of alcohol or drug treatment or major depression requiring treatment; current moderate to severe depression; history of panic disorder, psychosis, bipolar disorder, anorexia, or bulimia; kidney impairment; anticipated or current pregnancy; or breastfeeding. Prospective participants contacted the study and staff provided information and initial eligibility screening. Final eligibility required authorization by a licensed clinician and was completed in person (week 0).

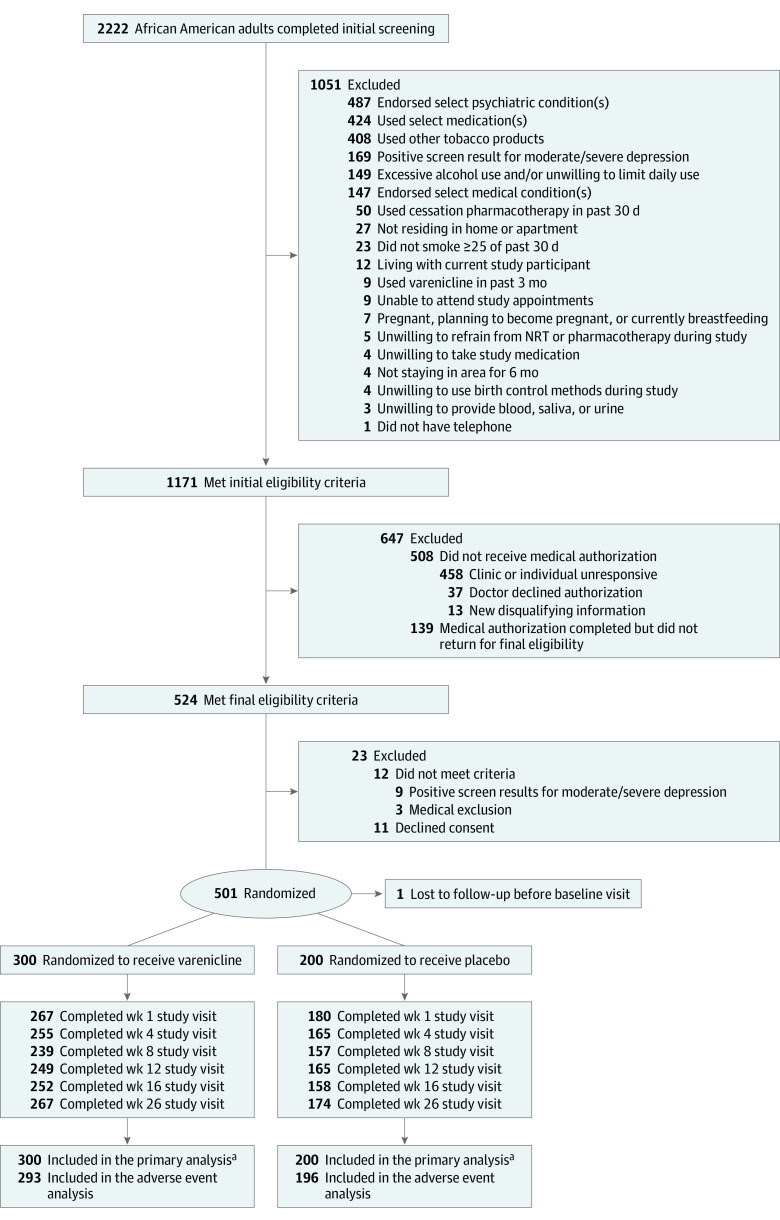

Randomization

After providing written consent, participants were assigned to receive varenicline or placebo in a 3:2 ratio via computer-generated individual random assignment to allow more participants to receive active treatment and concurrently strengthen evaluation of medication adverse events (Figure 1). Randomization was stratified by smoking level (≤10 or >10 cigarettes/d) and sex. A block size of 10 was used to generate the randomization schema. The university pharmacy bottled study medication, per randomization code, labelled with participant ID numbers to ensure that study staff, investigators, and participants were blinded to treatment assignment.

Figure 1. Participant Flow in a Study of the Effect of Varenicline Added to Counseling on Smoking Cessation Among African American Smokers.

NRT indicates nicotine replacement therapy.

aPrimary and secondary analyses of biochemically confirmed 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence used the full sample assigned to treatment (n = 500), with missing observations imputed as smokers. Analyses of other constructs included collected data only.

Intervention

Treatment included 12 weeks of study medication (varenicline or placebo), 6 sessions of counseling, and follow-up through week 26. All participants received the Kick It at Swope: Stop Smoking Guide, a culturally tailored educational guide used in previous studies with African American smokers.16,17

Pharmacotherapy: Varenicline or Placebo

At baseline, counselors gave participants a 30-day supply of the study medication in a pillbox, plus 1 extra week of medication to ensure time to obtain medication refill. Varenicline dosage was 1 mg twice daily, with titration following standard guidelines (0.5 mg once daily for 3 days, 0.5 mg twice daily for 4 days, and 1 mg twice daily for the remaining 11 weeks of treatment); because participants and staff were blinded to treatment, placebo use followed identical procedures. Participants were asked to set a quit date for day 8 of medication use. Participants received verbal and written instruction on proper use of study medication and importance of medication adherence.

Counseling

Cognitive behavioral counseling followed tobacco treatment guidelines.12 Counseling incorporated content from the Kick It at Swope: Stop Smoking Guide, reviewing the disproportionate risks of smoking for African American individuals, benefits of quitting, importance of medication adherence, and development of an individualized quit plan involving behavioral strategies and social support. Follow-up sessions at weeks 1, 4, 8, 12, and 16 promoted rewarding progress, preventing relapse or recovering from lapses, adhering to medication, and adjusting the treatment plan.

Retention

Participants received telephone, text, and postcard reminders before each visit and up to 6 messages to reschedule missed visits. Remuneration based on visit attendance, independent of smoking status, included $30 at weeks 0 and 4, $20 at weeks 8 and 16, $40 at week 12, and $50 at week 26.

Measures

Staff presented self-reported measures in oral and written form. Baseline assessment included age, sex, marital status, education, employment, health insurance, income, number of people in household, past-week cigarettes per day, use of other tobacco or electronic nicotine delivery, menthol use, time to first cigarette, age of initiation of regular smoking, quit attempt history, and previous use of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy. Baseline height and weight were collected to calculate body mass index. Assessments at weeks 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 26 included tobacco use (7-day Timeline Follow Back),18 smoking reward (modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire; range, 1 [not rewarding] to 7 [very rewarding]),19 withdrawal (Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale; range, 0 [none] to 32 [severe]),20,21 craving (Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges; range, 1 [none] to 7 [high]),22 and medication adverse effects (the National Cancer Institute’s Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events). Medication adherence was assessed at weeks 4, 8, and 12 using self-reported 5-day recall of doses taken and was operationalized as greater than or equal to 80% self-reported compliance (ie, use of at least 8 of 10 prescribed doses). Blood samples collected at week 0 measured baseline serum cotinine using standardized methods.23

Outcomes

Saliva was collected from participants who self-reported abstinence at weeks 4, 12, 16, and 26. For participants who reported smoking abstinence and use of nicotine replacement therapy, biochemical verification used urine assessment of anabasine and anatabine as biomarkers of tobacco use, distinguished from nicotine replacement therapy use, confirmed at less than 2 ng/mL.24 Statistical comparisons were preplanned for all time points, but only analyses at week 26 (final follow-up) and week 12 (end of medication) were identified as the primary and secondary aims of the study. The primary outcome was biochemically verified 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence at week 26, confirmed by salivary cotinine less than or equal to 15 ng/mL.25,26 Secondary outcomes included verified 7-day point prevalence abstinence at the end of the medication phase (week 12) for the full sample and for evaluation of light (1-10 cigarettes per day) and moderate to heavy (>10 cigarettes per day) smokers. Tertiary outcomes included medication adherence, adverse events, and self-reported smoking reward, withdrawal, and craving during the medication phase at weeks 4 and 12.

Sample Size

Based on data from previous studies with African American smokers,27,28 including a pilot study of varenicline,29 postulated outcomes at week 26 were 17% abstinence among participants in the varenicline group and 8% abstinence among those in the placebo group, treating those lost to follow-up as smokers per the Russell standard.30 A 9% increase in abstinence in the varenicline group compared with the placebo group would equate to a cessation ratio of 2.125, reflecting a clinically meaningful treatment outcome.31 With 300 participants receiving varenicline and 200 participants receiving placebo, the study was estimated to provide 80% power to detect these expected differences with a type I error rate of 5%.

Statistical Methods

Participants were analyzed according to their randomized treatment condition. Descriptive statistics included frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and SDs for quantitative variables. Verified abstinence rates, imputing missing observations as smokers,30 and unadjusted odds ratios are presented at weeks 4, 12, 16, and 26; χ2 tests evaluated differences between treatment groups at each time point. Post hoc sensitivity analyses of week 26 smoking abstinence examined last observation carried forward as well as multiple imputation, with 100 imputations, using a monotone logistic regression with treatment and smoking level as covariates to impute the missing data. Logistic regression was used to model the main effects of treatment and smoking level along with their interaction to determine whether there was a significant interaction between treatment and smoking level. A priori–defined subset analyses using χ2 tests compared verified abstinence among light smokers and among moderate to heavy smokers independently using χ2 tests. Drug-specific adverse events and overall experiences of adverse events were summarized with frequencies and percentages for each treatment group. Generalized estimating equations modeled drug adherence (≥80% pill adherence) at weeks 4, 8, and 12 in completers only and with missing values imputed as nonadherent. Linear mixed models, controlling for baseline values, assessed the effect of treatment on withdrawal, craving, and reward over the course of treatment. Analyses of primary and secondary outcomes were 2-sided tests conducted with a type I error rate of 5%. No multiple testing adjustments were made, thus statistical significance for secondary outcomes and subgroup analyses should be interpreted as exploratory. SAS, version 9.4M7 (SAS Institute), was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of study participants and Figure 1 depicts screening, enrollment, and retention of trial participants. Of 2222 African American adult smokers who completed screening, 1171 were initially eligible and 37 (3.2%) had clinicians decline medical authorization. Of 524 individuals who attended final eligibility screening, more than 95% were eligible and 501 were randomized to treatment; 1 individual randomized to the placebo group was lost to follow-up prior to the baseline assessment and was removed from the study. There was no significant between-group difference in study session attendance, and retention was 88% at week 26.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics in a Study of the Effect of Varenicline Added to Counseling on Smoking Cessation Among African American Smokers .

| Baseline measures | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Varenicline group (n = 300) | Placebo group (n = 200) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 51.6 (11.9) | 52.4 (11.0) |

| Women | 156 (52.0) | 106 (53.0) |

| Men | 144 (48) | 94 (47) |

| Married or living with partner | 78 (26.0) | 55 (27.5) |

| Education ≥high school | 250 (83.3) | 181 (90.5) |

| Employed | 143 (47.7) | 113 (56.5) |

| Had health insurance | 190 (63.3) | 134 (67.0) |

| Total gross income, mean (SD), $a | 26 662 (21 658) | 29 005 (25 380) |

| Median (25%-75%) | 20 000 (12 000-33 000) | 22 000 (12 000-38 000) |

| No. of people in household, mean (SD) | 2.2 (1.5) | 2.3 (1.4) |

| Median (25%-75%) | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 30.6 (7.1) | 30.1 (7.6) |

| No. of cigarettes per day, mean (SD) | 12.9 (6.9) | 12.2 (6.2) |

| Light smoker (1-10 cigarettes/d) | 154 (51.3) | 106 (53.0) |

| Use of other tobaccob | 48 (16.0) | 35 (17.5) |

| Baseline blood cotinine, mean (SD), ng/mL | 245 (144) | 221 (133) |

| Median (25%-75%) | 228 (153-290) | 203 (130-290) |

| Time to first cigarette ≤30 minc | 237 (79.0) | 158 (79.0) |

| Smoked menthol cigarettes | 263 (87.7) | 166 (83.0) |

| Had smoke-free householdd | 72 (24.0) | 56 (28.0) |

| Age of initiation of regular smoking, mean (SD), y | 18.3 (6.0) | 19.4 (6.6) |

| Attempted to quit smoking in past year | 237 (79.0) | 167 (83.5) |

| No. of 24-hr quit attempts in the past year, mean (SD) | 2 (5) | 2 (3) |

| Median (25%-75%) | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-2) |

| Past use of pharmacotherapy to stop smokinge | 142 (47.3) | 100 (50.0) |

| Past use of varenicline | 62 (20.7) | 46 (23.0) |

| PHQ-9 score (depression), mean (SD)f | 2.7 (2.9) | 2.4 (2.7) |

| MNWS score (withdrawal), mean (SD)g | 7.6 (5.8) | 7.1 (5.7) |

| QSU-Brief score (craving), mean (SD)h | 3.5 (1.7) | 3.4 (1.8) |

| mCEQ score (smoking reward), mean (SD)i | 3.0 (1.7) | 2.9 (1.7) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Provided by 479 participants (287 in the varenicline group and 192 in the placebo group).

All participants reported no other tobacco use at screening; during baseline assessment of the past 30 days, 83% of participants reported exclusive use of cigarettes, 14% reported use of 1 additional product, and 3% reported use of 2 other products.

Time to first cigarette after waking; ≤30 minutes indicates clinically significant nicotine dependence.

Had a smoke-free home (no smoking allowed inside the home).

Including nicotine replacement, bupropion, and varenicline.

9-Item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression screening: range, 0 to 27 (most severe); those with a score ≥15 (moderate/severe) were excluded.

Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS): range 0 (none) to 32 (severe).

Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU-Brief): range 1 (none) to 7 (high).

Modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire (mCEQ): range 1-7; higher scores indicate greater experience of withdrawal symptom s, craving, or smoking reward.

Primary Outcome

Effect of Varenicline on Smoking Abstinence at Week 26

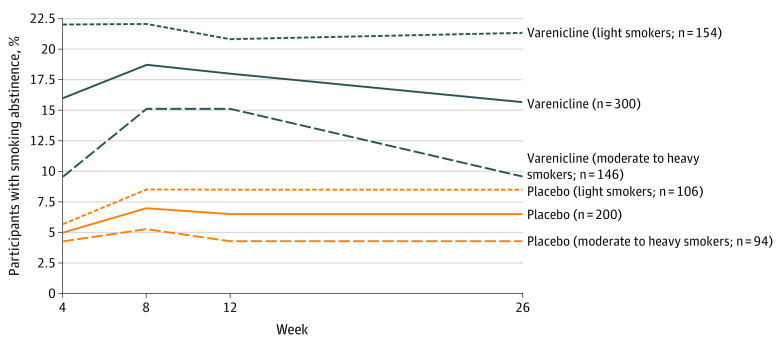

Biochemically verified 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence for each treatment condition is shown in Figure 2. When imputing those lost to follow-up as smokers, within the overall sample, participants who received varenicline were significantly more likely than those who received placebo to be abstinent at week 26 (15.7% vs 6.5%; difference, 9.2% [95% CI, 3.8%-14.5%]; OR, 2.7 [95% CI, 1.4-5.1]; P = .002) (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Findings from sensitivity analyses are presented in eTable 2 in Supplement 2; all analyses showed that participants randomized to receive varenicline had significantly higher abstinence at week 26 than those randomized to receive placebo.

Figure 2. Prevalence of Biochemically Verified 7-Day Point Prevalence Smoking Abstinence.

Secondary Outcomes

Effect of Varenicline on Smoking Abstinence at Week 12

Evaluation of verified point prevalence smoking abstinence at the end of medication treatment demonstrated that participants who received varenicline were significantly more likely than those who received placebo to be abstinent at week 12 (18.7% vs 7.0%; difference, 11.7% [95% CI, 6.0%-17.7%]; OR, 3.0 [95% CI, 1.7-5.6]; P < .001) (see Figure 2 and eTable 1 in Supplement 2 for verified abstinence at weeks 4, 12, and 16).

Abstinence by Treatment and Smoking Level

Smoking abstinence by treatment condition within the prespecified subgroup analyses for the 260 light smokers (1-10 cigarettes/d) and for the 240 moderate to heavy smokers (>10 cigarettes/d) is shown in Figure 2 (see also eTable 1 in Supplement 2). At the end of treatment week 12, light smokers assigned to receive varenicline vs placebo had significantly greater verified abstinence (22.1% vs 8.5%; difference, 13.6% [95% CI, 5.2%-22.0%]; OR, 3.0 [95% CI, 1.4-6.7]; P = .004). Moderate to heavy smokers assigned to receive varenicline vs placebo also demonstrated significantly greater abstinence at week 12 (15.1% vs 5.3%; difference, 9.8% [95% CI, 2.4%-17.2%]; OR, 3.1 [95% CI, 1.1-8.6]; P = .02). There was no significant treatment × cigarettes per day interaction (P = .96).

Tertiary Outcomes

Adherence to Study Medication

Results of the analysis of adherence by treatment condition in both completers only and with missing data imputed as nonadherent were not significant (eFigure in Supplement 2). Overall medication adherence decreased across weeks 4 (81.5%), 8 (79.9%), and 12 (71.5%) (P < .001).

Adverse Events

Table 2 shows adverse events of study participants. Rates of self-reported adverse events were similar between treatment conditions, with nausea reported more frequently in the varenicline group (163/293 [55.6%]) than the placebo group (90/196 [45.9%]). The varenicline group reported no severe adverse events and the placebo group reported 2 (1 case each of bronchial inflammation and kidney failure).

Table 2. Prevalence of Cumulative Adverse Events in a Study of the Effect of Varenicline Added to Counseling on Smoking Cessation Among African American Smokers .

| Adverse event | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Varenicline (n = 293) | Placebo (n = 196) | |

| By symptom (wk 1-16) | ||

| Gas or flatulence | 191 (65.2) | 130 (66.3) |

| Dry mouth | 183 (62.5) | 129 (65.8) |

| Trouble sleeping | 190 (64.8) | 117 (59.7) |

| Fatigue or loss of energy | 163 (55.6) | 112 (57.1) |

| Irritability | 167 (57.0) | 111 (56.6) |

| Headaches | 157 (53.6) | 95 (48.5) |

| Abnormal dreams | 146 (49.8) | 93 (47.4) |

| Nausea | 163 (55.6) | 90 (45.9) |

| Change in hostility or aggression | 99 (33.8) | 79 (40.3) |

| Constipation | 120 (41.0) | 78 (39.8) |

| Dizziness | 95 (32.4) | 62 (31.6) |

| Global (wk 1-16) | ||

| Serious adverse eventa | 0 | 2 (1.0) |

| Any adverse event | 276 (94.2) | 178 (90.8) |

There was 1 case of bronchial inflammation and 1 case of kidney failure reported in the placebo group.

Reinforcing Effects of Smoking

Linear mixed models longitudinally evaluated the effect of treatment over time (through week 12) on withdrawal (Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale), craving (Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges), and smoking reward (modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire), while controlling for baseline levels. As presented in Table 3, none of the full models illustrated a treatment × time interaction for withdrawal, craving, or smoking reward. In reviewing the main effects model of withdrawal, there was no significant effect of treatment or time. Craving decreased over time but with no significant effect of treatment. Smoking reward exhibited no change over time with no significant effect of treatment.

Table 3. Self-reported Withdrawal, Craving, and Smoking Reward in a Study of the Effect of Varenicline Added to Counseling on Smoking Cessation Among African American Smokers .

| Outcome | Treatment | Week 4 | Week 12 | P value for effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | No. | Mean (SD) | No. | Treatment | Time | Treatment × time | ||

| MNWS score (withdrawal)a | Varenicline | 8.09 (5.82) | 255 | 8.06 (6.85) | 249 | .59 | .90 | .43 |

| Placebo | 8.19 (6.53) | 165 | 8.50 (7.43) | 165 | ||||

| QSU-Brief score (craving)b | Varenicline | 1.57 (0.90) | 255 | 1.44 (0.91) | 249 | .09 | .002 | .68 |

| Placebo | 1.71 (0.88) | 165 | 1.54 (0.98) | 165 | ||||

| mCEQ score (reward)c | Varenicline | 2.03 (1.16) | 247 | 2.03 (1.17) | 170 | .20 | .13 | .66 |

| Placebo | 2.16 (1.07) | 160 | 2.09 (1.25) | 136 | ||||

Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS) score range, 0 (none) to 32 (severe).

Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU-Brief) score range, 1 (none) to 7 (high).

Modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire (mCEQ) score range, 1-7; higher scores indicate greater experience of withdrawal, craving, or smoking reward.

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial among African American adults who are daily smokers, varenicline added to counseling produced statistically significantly greater verified 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence compared with placebo and counseling. Adverse events reported by participants were similar between varenicline and placebo groups, and no severe adverse events were reported by participants receiving varenicline. These findings support the use of varenicline for the treatment of Black adults who are daily smokers. To our knowledge, this study marks the first placebo-controlled trial to evaluate varenicline efficacy for the full spectrum of Black adults who are light, moderate, and heavy daily smokers.

This study informs clinical approaches to treating light smokers. The current findings demonstrated that light smokers in the varenicline group had greater odds of quitting smoking at the end of 12 weeks of medication use compared with light smokers receiving placebo. Considering the negative health consequences of low-level smoking7,10 and challenges in treating Black adults who are light smokers in previous clinical trials,17,27 the magnitude of the current findings is clinically important. Although current clinical practice guidelines recommend pharmacotherapy and counseling for treating tobacco use, they do not offer specific pharmacotherapy guidelines for treating light smokers due to limited published data to date.12,13 The current findings add to evidence of varenicline efficacy in samples of predominantly White smokers using 5 to 10 cigarettes per day32 and Latino smokers using 1 to 10 cigarettes per day.33 Together with current findings, these studies provide evidence to inform clinical practice guidelines, supporting efficacy of varenicline for treatment of light smokers.

Abstinence outcomes in this trial were consistent with findings from Black smokers (daily use of 3-20 cigarettes/d) in the Quit2Live clinical trial,34 supporting external validity of the current study. The addition of the placebo comparison in this trial reinforces the conclusion that although lower abstinence rates may be seen relative to White smokers,34 varenicline significantly increases abstinence in Black smokers relative to placebo, showing greater odds of achieving abstinence at week 26. Similarly, secondary analyses of the EAGLES trial demonstrated that, compared with other pharmacotherapy, varenicline had greater relative efficacy for Black adults who are moderate to heavy smokers.15

In an effort to understand the demonstrated treatment effects, analyses examined potential mechanisms contributing to greater abstinence rates in the varenicline group compared with the placebo group. Although medication effects on reducing withdrawal, craving, and reward have been found in some placebo-controlled trials of varenicline,35,36,37 the current trial found no significant between-group differences in these factors. The majority of individuals in both groups continued to smoke and, therefore, would not be expected to report significant changes in withdrawal or craving, limiting examination of potential reinforcing effects of medication. Further, self-reported adverse events, counseling attendance, and medication adherence were comparable between groups. In this study, 18.5% of participants reported under-adherence to medication within the first month of treatment. Given the benefit of varenicline in supporting abstinence, further methods of increasing adherence are needed to maximize the effect of pharmacotherapy. Multiple research efforts are needed to increase efficacy of all pharmacotherapy options (eg, enhancing treatment utilization, extending treatment duration, changing pharmacotherapy or repeating cycles of treatment, harnessing personalized medicine), with attention to individual treatment needs and the full spectrum of tobacco users to reduce treatment disparities and improve health outcomes.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, generalizability of findings has limitations related to study inclusion criteria. Participants in this study were restricted to those interested in stopping smoking and without major psychiatric comorbidities. The EAGLES study, published after the launch of this trial, has now established the safety of varenicline in smokers with psychotic, anxiety, and mood disorders.38 Second, this study had ample power to measure statistically significant treatment effects for the full sample at week 26; however, the study may have had insufficient power to assess differences among subsets of light and heavy smokers.

Conclusions

Among African American daily smokers, varenicline added to counseling resulted in statistically significant improvement in the rates of 7-day point prevalence abstinence at week 26 compared to counseling and placebo. The findings support the use of varenicline in addition to counseling for tobacco use treatment among African American daily smokers.

Study Protocol

eTable 1. Verified 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence over time by treatment and smoking level (cigarettes/day)

eTable 2. Week 26 self-reported and verified 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence

eFigure. Self-reported medication adherence over time by treatment

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Leventhal AM, Dai H, Higgins ST. Smoking cessation prevalence and inequalities in the United States: 2014-2019. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(3):381-390. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen-Grozavu FT, Pierce JP, Sakuma KK, et al. Widening disparities in cigarette smoking by race/ethnicity across education level in the United States. Prev Med. 2020;139:106220. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, Giles WH. Vital signs: racial disparities in age-specific mortality among Blacks or African Americans—United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(17):444-456. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, Homa DM. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(11):397-405. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7111a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A Socioecological Approach to Addressing Tobacco-Related Health Disparities. National Cancer Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakuma KK, Felicitas-Perkins JQ, Blanco L, et al. Tobacco use disparities by racial/ethnic groups: California compared to the United States. Prev Med. 2016;91:224-232. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schane RE, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Health effects of light and intermittent smoking: a review. Circulation. 2010;121(13):1518-1522. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.904235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bronars CA, Faseru B, Krebill R, et al. Examining smoking dependence motives among African American light smokers. J Smok Cessat. 2015;10(2):154-161. doi: 10.1017/jsc.2014.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheuermann TS, Nollen NL, Cox LS, et al. Smoking dependence across the levels of cigarette smoking in a multiethnic sample. Addict Behav. 2015;43:1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hackshaw A, Morris JK, Boniface S, Tang JL, Milenković D. Low cigarette consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: meta-analysis of 141 cohort studies in 55 study reports. BMJ. 2018;360:j5855. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiffman S. Light and intermittent smokers: background and perspective. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(2):122-125. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leone FT, Zhang Y, Evers-Casey S, et al. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults: an official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5-e31. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1982ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30272-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nollen NL, Ahluwalia JS, Sanderson Cox L, et al. Assessment of racial differences in pharmacotherapy efficacy for smoking cessation: secondary analysis of the EAGLES randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2032053. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox LS, Faseru B, Mayo MS, et al. Design, baseline characteristics, and retention of African American light smokers into a randomized trial involving biological data. Trials. 2011;12:22. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahluwalia JS, Okuyemi K, Nollen N, et al. The effects of nicotine gum and counseling among African American light smokers: a 2 x 2 factorial design. Addiction. 2006;101(6):883-891. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01461.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychol Addict Behav. 1998;12(2):101. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.12.2.101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, Baker CL, Merikle E, Olufade AO, Gilbert DG. Confirmatory factor analyses and reliability of the modified cigarette evaluation questionnaire. Addict Behav. 2007;32(5):912-923. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toll BA, O’Malley SS, McKee SA, Salovey P, Krishnan-Sarin S. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21(2):216-225. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43(3):289-294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3(1):7-16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benowitz NL, Zevin S, Jacob P III. Sources of variability in nicotine and cotinine levels with use of nicotine nasal spray, transdermal nicotine, and cigarette smoking. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;43(3):259-267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1997.00566.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacob P III, Hatsukami D, Severson H, Hall S, Yu L, Benowitz NL. Anabasine and anatabine as biomarkers for tobacco use during nicotine replacement therapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(12):1668-1673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benowitz NL, Bernert JT, Caraballo RS, Holiday DB, Wang J. Optimal serum cotinine levels for distinguishing cigarette smokers and nonsmokers within different racial/ethnic groups in the United States between 1999 and 2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(2):236-248. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):13-25. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000070552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox LS, Nollen NL, Mayo MS, et al. Bupropion for smoking cessation in African American light smokers: a randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(4):290-298. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahluwalia JS, Harris KJ, Catley D, Okuyemi KS, Mayo MS. Sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation in African Americans: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(4):468-474. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nollen NL, Cox LS, Nazir N, et al. A pilot clinical trial of varenicline for smoking cessation in black smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(9):868-873. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West R, Hajek P, Stead L, Stapleton J. Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction. 2005;100(3):299-303. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes JR. A quantitative estimate of the clinical significance of treating tobacco dependence. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(3):285-286. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebbert JO, Croghan IT, Hurt RT, Schroeder DR, Hays JT. Varenicline for smoking cessation in light smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(10):2031-2035. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Dios MA, Anderson BJ, Stanton C, Audet DA, Stein M. Project Impact: a pharmacotherapy pilot trial investigating the abstinence and treatment adherence of Latino light smokers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;43(3):322-330. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nollen NL, Mayo MS, Sanderson Cox L, et al. Factors that explain differences in abstinence between Black and White smokers: a prospective intervention study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(10):1078-1087. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cinciripini PM, Robinson JD, Karam-Hage M, et al. Effects of varenicline and bupropion sustained-release use plus intensive smoking cessation counseling on prolonged abstinence from smoking and on depression, negative affect, and other symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(5):522-533. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West R, Baker CL, Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG. Effect of varenicline and bupropion SR on craving, nicotine withdrawal symptoms, and rewarding effects of smoking during a quit attempt. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2008;197(3):371-377. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1041-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandon TH, Drobes DJ, Unrod M, et al. Varenicline effects on craving, cue reactivity, and smoking reward. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;218(2):391-403. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2327-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evins AE, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with psychotic, anxiety, and mood disorders in the EAGLES trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;39(2):108-116. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study Protocol

eTable 1. Verified 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence over time by treatment and smoking level (cigarettes/day)

eTable 2. Week 26 self-reported and verified 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence

eFigure. Self-reported medication adherence over time by treatment

Data Sharing Statement