Abstract

The United States healthcare system has increasingly embraced value-based programs that reward improved outcomes and lower costs. Healthcare value, defined as quality per unit cost, was a major goal of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act amidst high and rising US healthcare expenditures. Many early value-based programs were specifically designed for patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and targeted towards dialysis facilities, including the ESRD Prospective Payment System (PPS), ESRD Quality Incentive Program (QIP), and ESRD Seamless Care Organizations (ESCOs). While a great deal of attention has been paid to these ESRD-focused programs, other value-based programs targeted towards hospitals and health systems may also affect the quality and costs of care for a broader population of patients with kidney disease. Value-based care for kidney disease is increasingly relevant in light of the Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) initiative, which introduces new value-based payment models: the mandatory ESRD Treatment Choices (ETC) Model in 2021 and voluntary Kidney Care Choices (KCC) Model in 2022.1 In this review article, we summarize the emergence and impact of value-based programs on the quality and costs of kidney care, with a focus on federal programs. Key opportunities in value-based kidney care include shifting the focus towards chronic kidney disease, enhancing population health management capabilities, improving quality measurement, and leveraging programs to advance health equity.

Keywords: Value-based care, Health policy, Alternative payment models, Chronic kidney disease, Kidney failure, End-stage renal disease, Population health

Introduction

The United States (US) has engaged in a decades-long experiment to incentivize high quality, cost-efficient care through dozens of value-based programs. Healthcare value, defined as quality per unit cost, was an explicit goal of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act amidst high and rising US healthcare expenditures.2 While a great deal of attention has been paid to End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD)-focused programs in the nephrology literature, other value-based programs may also affect the quality and costs of care for a broader population of patients with kidney disease. Value-based care for kidney disease is increasingly relevant in light of the Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) initiative, which introduces new value-based payment models.1

In this review article, we outline the emergence and impact of US value-based programs on the quality and costs of kidney care. We summarize non-kidney-focused and kidney-focused federal value-based programs, which were chosen based on 1) scope and magnitude and 2) inclusion of and/or potential impact on patients with kidney disease. Using publicly available program descriptions from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), we describe the years of implementation, patient population, mandatory vs. voluntary provider participation, type of financial arrangement, quality and cost measures, and relevance to kidney care (Table 1).3 We highlight how learnings from past value-based programs inform future opportunities for value-based kidney care within AAKH and beyond. This article is aimed at nephrologists, payers, and policymakers and seeks to inform future health policy changes.

Table 1.

Summary of Federal Value-Based Programs Relevant to Kidney Disease

| Value-Based Program | Years | Patient Population | Provider Participation | Type of Value-Based Program | Financial Incentives | Quality Measures | Cost Measures | Relevance to Kidney Care† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Non-kidney-focused | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) | 2012 – | All clinical conditions | Voluntary | Shared savings/losses | Shared savings/losses | Measures of patient/caregiver experience, care coordination/patient safety, preventive health, and at-risk populations | Medicare expenditures benchmark | ACO-aligned patients with ESRD had $572 per year lower spending than non-ACO patients27 |

| Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program (HVBP) | 2012 – | Hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries | Mandatory* | P4P | Bonus/penalty on IPPS payments | Measures of clinical outcomes, person and community engagement, and safety | Medicare spending per beneficiary | Hospitalized patients with kidney disease were included in HVBP |

| Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) | 2012 – | Hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries with 6 targeted conditions | Mandatory* | P4P | Penalty on IPPS payments | Risk-adjusted readmission ratios | – | Patients with kidney disease have high readmission ratios, and hospitalized patients were recipients of discharge planning interventions |

| Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) | 2013 – | Patients in 8 Clinical Episode Service Lines Groups | Voluntary | Bundled payments | Reconciliation payments | Up to 5 claims-based measures | Target Price for Clinical Episode | Includes “Renal Failure” episode of care |

| Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) | 2017 – | Ambulatory Medicare beneficiaries | Mandatory* | P4P | Bonus/penalty on Medicare covered professional services | Choose from 209 quality measures in performance year 2021 | Choose from 20 cost measures in performance year 2021 | Mandatory participation for nephrologists |

| Medicare Advantage | 1997 – | All clinical conditions | – | Risk-adjusted capitated payments to private plans | Star ratings program | 47 measures | Private plan assumes financial risk | Patients with ESRD eligible to newly enroll in 2021 |

|

| ||||||||

| Kidney-focused | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Quality Incentive Program (QIP) | 2012 – | ESRD on dialysis | Mandatory | P4P | Up to 2% financial penalty | 14 measures of clinical care, care coordination, safety, and patient and family engagement | SRR SHR |

|

| ESRD Seamless Care Organizations (ESCOs) | 2015 – 2021 | ESRD on dialysis | Voluntary | Shared savings/losses | Shared savings/losses | 26 quality measures in 5 domains | Total costs of care, excluding Part D | |

| ESRD Treatment Choices (ETC) Model | 2021 – | ESRD | Mandatory if randomized to model | P4P | Bonus/penalty on Medicare payments | Home dialysis, transplant waitlisting, and living donor transplant rates | None | |

| Kidney Care Choices (KCC) | 2022 – | CKD 4, CKD 5, ESRD | Voluntary | Capitation, P4P, shared savings/losses | Bonus/penalty based on quality and utilization measures, $15,000 transplant bonus, shared savings/losses | Patient activation measure, depression remission, Optimal ESRD starts | Hospitalization costs, total per capita costs | |

ACO, Accountable Care Organizations; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; IPPS, Inpatient Prospective Payment System; P4P, pay-for-performance.

With certain exclusion criteria.

Listed only for non-kidney-focused programs, as kidney-focused programs are entirely relevant to kidney care.

Emergence of Value-Based Kidney Care

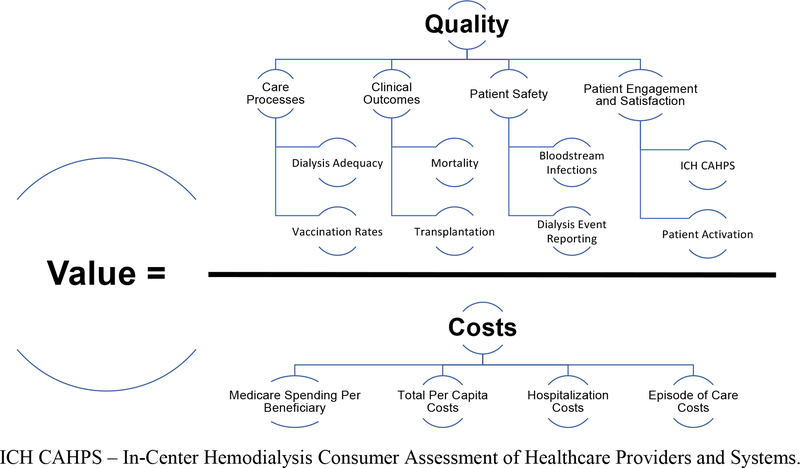

The US is an outlier in health expenditures, which account for 17.7% of its Gross Domestic Product.4 Despite high spending, the US has worse life expectancy, chronic disease morbidity, and avoidable mortality than other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.5 Due to growing recognition of rising healthcare costs, value was prominently featured in the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Healthcare value, defined by Michael Porter as “the health outcomes achieved per dollar spent,” comprises both quality and cost (Figure 1).6 The ACA legislatively mandated CMS to implement several value-based payment models and authorized the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to launch 54 value-based programs over the past 10 years.2,7

Figure 1.

Goals of Value-Based Kidney Care and Example Measures.

Value-based programs offer a promising opportunity to improve kidney disease care, given the tremendous human and financial burden of kidney diseases on society. First, patients with kidney failure (ESRD) have poor clinical outcomes, including >50% 5-year mortality and high rates of cardiovascular events, septicemia, hospitalizations, and symptom burden.8 Furthermore, there is substantial variation in dialysis facility-level quality of care metrics, home dialysis use, and transplant waitlisting, suggesting opportunities for improvement.9–11 Second, costs of care for patients with ESRD have risen substantially and now exceed $49 billion per year, ~7% of Medicare’s FFS budget and ~1% of the entire US federal budget.8 Third, patients with ESRD have a more homogenous payer mix (majority Medicare) than other conditions, meaning that dialysis facilities are highly likely to make care delivery changes in response to CMS value-based programs. Fourth, dialysis facilities are highly consolidated and predominantly for-profit, making them highly responsive to payment changes.12,13

Impact of CMS Value-based Programs on Kidney Care

Accountable Care Organizations

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), in which groups of doctors, hospitals, and other healthcare providers join together and contract with CMS to assume financial risk for a population of patients, have been a flagship value-based program of CMS.14 Several iterations of ACO Models have been implemented, beginning with the Pioneer ACO Model in 2012 and followed by Next Generation ACO Models and the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP). ACOs are eligible for shared savings from CMS if they exceed minimum quality standards and their attributed beneficiaries have lower expenditures than their historical benchmark spending. Similarly, ACOs assume financial risk for shared losses. Thus, ACOs are financially incentivized to implement care delivery interventions such as care management in attempt to reduce total costs of care. While ACOs adopted care coordination and multidisciplinary care activities,15,16 it is unclear if these resulted in improved quality or outcomes.17 Several ACO Models have been associated with improvements in quality at similar cost (i.e. improved value), although most ACO Models did not generate net savings to CMS because reductions in spending were largely offset by shared savings payments.7,18–20

Because patients with ESRD account for high expenditures ($93,191/yr per hemodialysis patient and $78,741/yr per peritoneal dialysis patient) and a substantial percentage of hospitalizations are potentially avoidable, they represent a modifiable opportunity for ACOs to lower costs of care.8,21–26 Evidence thus far on ACOs curbing ESRD costs is promising. Bakre et al. examined the association of ACO alignment with spending for patients with ESRD, finding that ACO-aligned patients had $572 per year lower spending than non-ACO patients in adjusted analyses.27

We, as authors, have served in ACO leadership in two urban, academic medical centers. Both ACOs had nursing, social work, pharmacist, and patient navigator interventions targeted specifically towards patients with ESRD on dialysis, with the goal of reducing emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and readmissions. Early results show these care coordination interventions reduce utilization and are cost saving.28

Value-Based Purchasing and Hospital Readmission Reductions Program

The Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program, a pay-for-performance program implemented in 2012, adjusts hospital reimbursements for inpatient stays based on clinical outcome, safety, cost, and patient engagement metric scores. Measures relevant to kidney disease include central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI), catheter-associated urinary tract infections, Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia, cost measures, and patient satisfaction measures.29 In Fiscal Year 2021, hospitals could receive up to a 3.94% net increase and 1.62% net decrease in Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) payments, but the majority of hospitals received a small incentive/penalty of ± 0.5%.29 Hospitals implemented numerous care delivery changes in response to the VBP, and evidence suggests that care coordination processes were associated with improved patient satisfaction, VBP scores, and clinical outcomes.30 It is unclear whether the VBP Program has resulted in improvements in quality, as VBP hospitals did not have improvements in clinical process or patient experience measures compared with critical access hospitals not in VBP.31 There have been no investigations of the impact of the VBP Program on patients with kidney disease, specifically. Successful hospital-based interventions in the VBP Program for CLABSI and MRSA reduction could potentially inform current dialysis safety initiatives.32

The Hospital Readmissions Reductions Program (HRRP) is another CMS value-based program. In the HRRP, hospitals receive up to a 3% payment reduction in DRG payments for inpatient hospitalizations, based on their 30-day risk-standardized readmission ratios for the following conditions: acute myocardial infarction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, pneumonia, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, and elective joint replacements. In a survey of hospital leaders, 66% said that the HRRP had a “significant” or “great” impact on efforts to reduce readmissions.33 A study from Gupta finds that financial incentives and quality improvement initiatives under the HRRP were effective in reducing readmissions.34 An analysis by Ibrahim et al. found evidence of spillover effects; HRRP was associated with lower readmission for both targeted and nontargeted conditions in the program.35 Numerous investigations have examined whether decreased readmissions in the HRRP were associated with increased mortality, using different causal inference methodologies and showing conflicting findings.34,36,37 This controversy highlights the need for ongoing assessment of potential unintended consequences in value-based programs.

Patients with ESRD have a 30-day readmission risk of 31.1%, higher than any group targeted in the HRRP program.8 While the HRRP is not specifically directed towards kidney patients, hospitalized patients with kidney disease were also recipients of HRRP interventions to improve discharge planning and transitions of care. The nephrology community could benefit from lessons learned in the HRRP by evaluating interventions to reduce readmissions in kidney patients in cluster randomized trials. For example, Project Better Outcomes for Older adults through Safe Transitions (BOOST), a collection of discharge best practices, has been associated with a 2% reduction in readmission risk, and could be implemented in late-stage chronic kidney disease (CKD) clinics and dialysis facilities.38

Bundled Payments and Episodes of Care

Thus far, we have discussed CMS risk-based payment models (ACOs) and pay-for-performance programs (VBP and HRRP). These payment strategies represent a departure from FFS-based care, tying payments to measures of quality and cost. Another approach is paying a bundled payment for an episode of care, defined as a set of services provided to treat a clinical condition or procedure. Early bundled payments in the 1980s-90s were for cardiac surgeries, and most recently, the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative pays reconciliation payments if episode of care costs are lower than a target price. Performance on quality metrics including readmissions, advanced care planning, and patient safety indicators are used to adjust reconciliation payments.39 BPCI episodes currently start with a hospital admission for selected conditions and end 90 days post-discharge. “Renal failure” is one of the BCPI episodes of care, predominantly including patients with acute kidney injury as a principal diagnosis. Importantly, patients eligible for Medicare due to ESRD are excluded from BPCI. Similar to ACOs, BPCI reduced Medicare FFS payments, but did not result in net savings after reconciliation payments.40 Early results from the BPCI Advanced model suggest that BPCI was associated with lower mortality for patients with renal failure.41 Principles of bundled payments for episodes of care could be further evaluated in future kidney-focused value-based programs. For example, if nephrology practices were reimbursed for an episode of care surrounding dialysis initiation, they would be incentivized to develop cost saving interventions that avoid inpatient hospitalizations, the most costly aspect of the transition to dialysis.8 This episode of care would likely be restricted to patients with pre-existing Medicare coverage, given the three-month waiting period for Medicare entitlement based on ESRD and the 30-month coordination period for private payers.

Merit-Based Incentive Program

The Merit-Based Incentive Program (MIPS) is a CMS value-based program focused on outpatient care. Legislatively authorized by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015, MIPS is a pay-for-performance program that adjusts Medicare reimbursements based on clinician performance on quality, promoting interoperability, improvement activities, and cost measures.42 Promoting interoperability measures focus on the electronic exchange of information, and improvement activities measures focus on quality improvement. MIPS is mandatory for clinicians enrolled in Medicare, unless they meet certain exemption criteria such as participation in Advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs) with two-sided risk.43 MIPS quality measures relevant to kidney disease include MIPS 236: Controlling High Blood Pressure and MIPS 1: Diabetes: Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) Poor Control (>9%), among others. MIPS improvement activities measures require practices to record quality improvement and care coordination strategies, but rely on self-reporting and do not assess the intensity or fidelity of these activities.

Early evidence of nephrologist MIPS performance highlights several program areas in need of reform. In performance year 2018, 7,120 nephrologists participated in MIPS. Excluding non-patient-facing/non-participating nephrologists and those meeting extreme hardship criteria, nephrologists received a median final score of 100 with 99.5% receiving a positive payment adjustment.44 These universally near perfect scores call into question whether MIPS is meaningfully distinguishing between high performing and low performing clinicians. Future investigations of longitudinal data could elucidate if MIPS has driven improvements in quality of care. Low weighting of the cost category (0% in 2017, 10% in 2018, 15% in 2019, 0% in 2020) make it unlikely that MIPS has thusfar driven cost improvements. Cost category weighting is being increased to 20% in 2021 and 30% in 2022. Beginning in 2023, CMS is implementing MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs), a revised version of the MIPS program with a more streamlined and complementary set of measures.45 An MVP for Nephrology – which seeks to select a core set of measures relevant to nephrology, decrease the number of measures to reduce complexity, improve comparability of performance, and serve as a gateway towards APM participation – is currently under development.46

To summarize, while there is a strong conceptual basis for value-based care, evidence on the effectiveness of CMS value-based programs is mixed. Moreover, patients with kidney disease were exposed to ACO, VBP, HRRP, and MIPS programs, but there is little evidence of program effects on the quality and costs of kidney care.

Kidney-focused Value-based Programs

ESRD Quality Incentive Program and Seamless Care Organizations

In 2012, alongside the ESRD PPS, the ESRD QIP was implemented as the nation’s first mandatory pay-for-performance program, focused largely on facility-based dialysis care. The ESRD QIP evaluates dialysis facilities on 14 quality measures and incurs up to a 2% financial penalty on low performing facilities.47 Lower dialysis facility QIP scores are associated with increased mortality,48 but whether QIP scores or incentives are causally associated with patient outcomes is unclear. An analysis by Sheetz et al. tackles this question by leveraging the threshold for financial penalization in a regression discontinuity design.49 The authors find no evidence that facilities just above versus just below the financial penalty threshold had changes in QIP scores in later years.49,50 One potential explanation for these findings is that the ESRD QIP incentivized performance across all facilities, not just those with previous payment reductions.

ESRD Seamless Care Organizations (ESCOs), implemented in 2015 as the nation’s first specialty-specific ACO, have been one of the most consequential value-based kidney care programs.51 Informed by the ESRD Disease Management Demonstration projects,52–55 dialysis facilities participating in ESCOs are held financially accountable for the quality, costs, and experience of care for patients with ESRD through quality benchmarks and shared savings/losses. ESCOs are assessed on 26 quality measures in 5 domains: patient safety, person- and caregiver-centered experience and outcomes, communication and care coordination, clinical quality of care, population health. A CMS-sponsored evaluation report showed a 4% reduction in hospitalizations and 7% reduction in catheter use among ESCO-aligned compared with non-ESCO-aligned patients across three performance years.56 Reductions in Medicare expenditures were seen and driven largely by reductions in hospitalizations, but offset by shared savings payments.57 In sum, ESCOs had a promising impact on quality and costs of care, representing improvements in value.

Advancing American Kidney Health – ESRD Treatment Choices and Kidney Care Choices

Ongoing quality of care gaps and rising costs for kidney care culminated in the Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) Executive Order in 2019, which includes a sweeping range of initiatives to improve healthcare value for patients with kidney disease.1 As part of AAKH, two new innovative payment models for kidney disease have been introduced: ETC and KCC. ETC, a seven-year mandatory model that started in January 2021, is a pay-for-performance program based on nephrologist and dialysis facility-level home dialysis, transplant waitlisting, and living donation rates.58 Approximately 30% of Hospital Referral Regions have been randomized to participate in the ETC, with the goal of measuring its impact on home dialysis, transplant waitlisting, and living donor transplantation compared to standard care. The KCC Model starting in 2022 includes patients with CKD G4, CKD G5, and ESRD, and includes two versions: 1) Kidney Care First, which is specific to nephrologists and consists of quarterly capitated payments for CKD professional services and a transplant bonus payment for patients successfully transplanted, as well as payment adjustments based on quality metric performance on Patient Activation Measure, depression remission, and Optimal Starts; 2) Comprehensive Kidney Care Contracting, targeted towards nephrologists, transplant centers, dialysis facilities, and other entities, which consists of shared savings/losses for the total cost and quality of care for attributed patients. Both the ETC and KCC, represent the first instance in which nephrologists and their practices are central participants in kidney-focused value-based care, with direct financial incentives tied to professional payments.

Medicare Advantage, including Chronic Condition Special Need Programs

Medicare Advantage (MA) plans, which involve private-sector health insurers providing benefits to Medicare beneficiaries in return for capitated payments from CMS and often in concert with negotiating rates with provider organizations, have historically excluded patients with ESRD from newly enrolling in MA plans. However, as of January 2021, CMS expanded MA enrollment to patients with ESRD. The impact of this change on cost and outcomes is still unclear, as is how many patients will enroll and how dialysis organizations will engage with MA plans. MA Special Need Plans (SNPs), targeting specific high-need beneficiaries, have been trialed in patients with ESRD.59 ESRD SNPs are required to develop interdisciplinary care teams, risk assessments, individual care plans, care transition protocols, and specialized provider networks. Two recent analyses showed that compared to traditional FFS Medicare patients, patients with ESRD enrolled in MA SNPs had lower utilization and lower mortality.60,61 Finally, other private payer-based value-based care programs exist outside of Medicare, many in concert with large dialysis organizations, although private payers may not cover a sufficient number of a patients in a single practice to affect changes in care delivery.62,63

Value-based Kidney Care: Opportunities and Future Directions

Opportunities

Given past evidence of the effects of value-based programs on kidney care, will KCC, MA plans, MVPs, and other future programs be successful in improving quality and reducing costs? Past value-based programs have had mixed success in improving quality and reducing costs, but several considerations could push new kidney care models in a promising direction (Table 2).

Table 2.

Key Opportunities in Value-Based Kidney Care.

| Recommendations | |

|---|---|

| Shift Focus Towards Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) | • Include patients with CKD in mandatory and voluntary payment models |

| • Implement and invest in multidisciplinary care | |

| Enhance Population Health Management Capabilities | • Invest in electronic health record-based population health tools in health systems |

| • Strengthen Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services learning collaboratives that share population health best practices | |

| Improve Data Reporting and Quality Measurement | • Develop and test CKD-specific quality measures that span the spectrum of CKD care |

| • Select quality measures that are meaningful to patients | |

| Leverage Programs to Advance Health Equity | • Stratify quality measures by social risk factors to monitor disparities |

| • Incorporate social risk factors in payment adjustment | |

| • Dedicate resources to screen for and address social needs |

First, policymakers must shift the focus of value-based kidney care upstream to CKD management. Notably, prior to KCC, kidney-focused value-based programs have been restricted to patients with ESRD. Shifting focus to CKD management prior to dialysis could avert incident ESRD, cardiovascular events, and other adverse outcomes, as well as promote preemptive transplantation and home dialysis. Value-based programs such as a bundled payment for dialysis initiation could address financial disincentives of CKD care and incentivize multidisciplinary care addressing the educational, social, and complex medical needs of this population, which is shown to be cost-effective.64,65 Programs that develop and invest in multidisciplinary care and coordination across the spectrum of kidney disease care, like the MA SNP programs, have been shown in multiple settings to improve outcomes and potentially reduce cost.66–71

Second, payers and providers should enhance their population health management capabilities, while also rigorously evaluating them.72 Nephrologists can partner further with health system leaders to develop and implement care delivery changes for patients with kidney disease. Nephrology practices are directly partnering with value-based kidney care companies (e.g. Cricket Health, Strive Health, Somatus) on predictive analytics and risk tiered care management systems.73–75 Nephrology fellowship directors could incorporate health policy sessions or training pathways into fellowship curriculums, such as the Baylor College of Medicine Public Policy pathway.76 Health systems can invest in CKD registries to facilitate real-time population-level tracking and identification of care delivery opportunities.77,78 National professional organizations should further disseminate population health “toolkits” of evidence-based care delivery interventions.79 CMS should continue to incorporate quality improvement learnings in online collaboratives.

Third, improvements in data reporting and measurement are needed to better facilitate value-based care. Quality measurement is an inherent component of value-based programs, and two key data hurdles in incorporating CKD in value-based programs are 1) lack of CKD-specific quality measures that are influenceable by nephrologists and 2) variable and insensitive ICD-10 coding for CKD in claims data.80,81 Additional CKD-specific quality measures are under development, and could be used in KCC, MIPS/MVPs, and future kidney-focused programs.82,83 Similarly, increasing patient-centeredness and engagement within value-based programs could ensure that quality measures selected are meaningful to patients.84

Lastly, value-based programs can and should be leveraged to advance health equity. Robust evidence now shows that safety-net providers and those caring for patients with greater social risk factors, adverse social conditions associated with poor health,85 are more likely to be penalized in value-based programs.86–90 Similar patterns are emerging in kidney-focused programs. Dialysis facilities in low-income ZIP codes or with greater proportions of Black or Medicaid dual-eligible patients had lower scores in the ESRD QIP.91 In the ETC model, dialysis facilities serving more Black, Hispanic, and/or low socioeconomic status patients are expected to incur greater penalties, given disparities in home dialysis and transplant rates.92–94 Several strategies can ensure that value-based programs not only do not exacerbate disparities, but also are leveraged to mitigate health inequities.95 Quality measures should be stratified by social risk factors to monitor disparities in care.96 Health equity incentives, which are being proposed in the ETC Model, could reward narrowing disparities or improving quality in lower socioeconomic groups such as dual-eligible patients.97 Quality measures could be compared within strata of providers to ensure equitable comparisons and reduce penalties to safety-net entities, as currently done in HRRP and proposed in the ETC Model, although this holds certain providers to lower standards.97–100 Finally, payments could be adjusted to dedicate resources to patients with greater social needs; it is important to distinguish performance adjustment, which may mask disparities by “adjusting them away,” from payment adjustment which could provide additional bonus payments to safety-net providers to invest in alleviating inequities.100

Future Directions

The AAKH ETC and KCC models are nascent value-based care models that have the potential to transform how kidney care is delivered across the spectrum of CKD, with nephrologists at the helm of decision-making. Success of KCC, which is inclusive of CKD patients for the first time in a meaningful way, could potentially reduce patient days on dialysis and stem patient and societal burden of the disease. Given that ETC is now underway and involves nearly a third of the US ESRD population, we will soon learn how effective setting and incentivizing clear targets for outcome measures like home dialysis and transplant is in driving improvements in care delivery. In recognition of the investment needed to create multidisciplinary care teams and deploy data tracking capabilities like registries, the KCC models could be strengthened by increased population health resources through higher CKD capitation payments in the first years of implementation. Similarly, less reliance on measures that may be challenging for nephrologists to influence directly, like depression scores and even patient activation, could be reporting measures in the initial model years. Regardless of the final models implemented, AAKH has shifted kidney disease care away from care delivery largely limited to FFS to being more inclusive of value-based care. Nephrologists and their patients are best served by actively engaging policymakers in shaping and providing feedback on these models.

Conclusion

The US healthcare system has increasingly embraced value-based financial structures that reward improved outcomes and lower costs. Federal value-based programs have a great deal of potential that has yet not been realized in kidney disease. Given the intensified federal attention on kidney disease, now is the time for nephrologists, kidney organizations, patients, payers, and policy makers to partner on meaningful value-based care reforms. AAKH-based payment models, MA plan expansion to ESRD patients, and MVP development are positive first steps, but greater iteration will be needed to achieve the most positive outcomes for patients and curtail healthcare expenditures.

Clinical Summary.

Value-based programs reward improved outcomes and lower costs. In addition to ESRD-focused programs, other value-based programs targeted towards hospitals and health systems may also impact the quality and costs of kidney care.

ESRD Seamless Care Organizations have shown promising results in reducing hospitalizations and catheter use, setting the stage for two new value-based programs in the Advancing American Kidney Health initiative: the ESRD Treatment Choices Model and Kidney Care Choices.

Key opportunities in value-based kidney care include shifting the focus towards chronic kidney disease, enhancing population health management capabilities, improving quality measurement, and leveraging programs to advance health equity.

Financial Disclosure:

Dr. Tummalapalli received consulting fees from Bayer AG and funding from Scanwell Health, unrelated to the submitted work. Dr. Mendu received consulting fees from Bayer AG, unrelated to the submitted work.

Support: Dr. Tummalapalli is supported by funding from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (F32DK122627) and the National Kidney Foundation Young Investigator Grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Advancing American Kidney Health. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/262046/AdvancingAmericanKidneyHealth.pdf Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 2.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111–148, 124 Stat. 119 (2010), Codified as Amended 42 U.S.C. § 18001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Value-Based Programs. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs Accessed June 1, 2021.

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditure Data. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 5.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health Statistics 2020. https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 6.Porter ME. What is value in health care. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2477–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith B CMS innovation center at 10 years—progress and lessons learned. N Engl J Med 2021;384:759–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United States Renal Data System. 2020 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saunders MR, Chin MH. Variation in dialysis quality measures by facility, neighborhood and region. Medical care 2013;51:413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briggs V, Davies S, Wilkie M. International variations in peritoneal dialysis utilization and implications for practice. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2019;74:101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melanson TA, Gander JC, Rossi A, Adler JT, Patzer RE. Variation in Waitlisting Rates at the Dialysis Facility Level in the Context of Goals for Improving Kidney Health in the United States. Kidney International Reports 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eliason PJ, Heebsh B, McDevitt RC, Roberts JW. How acquisitions affect firm behavior and performance: Evidence from the dialysis industry. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2020;135:221–67. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thamer M, Zhang Y, Kaufman J, Kshirsagar O, Cotter D, Hernán MA. Major declines in epoetin dosing after prospective payment system based on dialysis facility organizational status. American journal of nephrology 2014;40:554–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ACO Accessed May 1, 2021..

- 15.Lewis VA, Schoenherr K, Fraze T, Cunningham A. Clinical coordination in accountable care organizations: A qualitative study. Health care management review 2019;44:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hearld LR, Carroll N, Hall A. The adoption and spread of hospital care coordination activities under value-based programs. Am J Manag Care 2019;25:397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouayogodé MH, Mainor AJ, Meara E, Bynum JP, Colla CH. Association between care management and outcomes among patients with complex needs in Medicare accountable care organizations. JAMA network open 2019;2:e196939–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Landon BE, Hamed P, Chernew ME. Medicare spending after 3 years of the Medicare Shared Savings Program. New England Journal of Medicine 2018;379:1139–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis VA, Fisher ES, Colla CH. Explaining sluggish savings under accountable care. The New England journal of medicine 2017;377:1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao JM, Navathe AS, Werner RM. The Impact of Medicare’s Alternative Payment Models on the Value of Care. Annual review of public health 2020;41:551–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nissenson AR, Maddux FW, Velez RL, Mayne TJ, Parks J. Accountable care organizations and ESRD: The time has come. American journal of kidney diseases 2012;59:724–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watnick S, Weiner D, Shaffer R, Inrig J, Moe S, Mehrotra R. Dialysis advisory Group of the American Society of nephrology. Comparing mandated health care reforms: the affordable care act, accountable care organizations, and the Medicare ESRD program. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;7:1535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones ER, Hostetter TH. Integrated renal care: are nephrologists ready for change in renal care delivery models? Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2015;10:335–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathew AT, Strippoli GF, Ruospo M, Fishbane S. Reducing hospital readmissions in patients with end-stage kidney disease. Kidney international 2015;88:1250–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathew AT, Rosen L, Pekmezaris R, et al. Potentially avoidable readmissions in United States hemodialysis patients. Kidney international reports 2018;3:343–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Physician visits and 30-day hospital readmissions in patients receiving hemodialysis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2014;25:2079–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakre S, Hollingsworth JM, Yan PL, Lawton EJ, Hirth RA, Shahinian VB. Accountable Care Organizations and spending for patients undergoing long-term dialysis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2020;15:1777–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly Y, Goodwin D, Wichmann L, Mendu ML. Breaking down health care silos. Harvard Business Review 2019;1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program Payments. https://qualitynet.cms.gov/inpatient/hvbp/payment Acessed May 1, 2021.

- 30.Jain S, Thorpe KE, Hockenberry JM, Saltman RB. Strategies for Delivering Value-Based Care: Do Care Management Practices Improve Hospital Performance? Journal of Healthcare Management 2019;64:430–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan AM, Krinsky S, Maurer KA, Dimick JB. Changes in hospital quality associated with hospital value-based purchasing. New England Journal of Medicine 2017;376:2358–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher M, Golestaneh L, Allon M, Abreo K, Mokrzycki MH. Prevention of bloodstream infections in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2020;15:132–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joynt KE, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Opinions on the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program: results of a national survey of hospital leaders. The American journal of managed care 2016;22:e287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta A Impacts of performance pay for hospitals: The readmissions reduction program. American Economic Review 2021;111:1241–83. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibrahim AM, Nathan H, Thumma J, Dimick JB. Impact of the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program on surgical readmissions among Medicare beneficiaries. Annals of surgery 2017;266:617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wadhera RK, Maddox KEJ, Wasfy JH, Haneuse S, Shen C, Yeh RW. Association of the hospital readmissions reduction program with mortality among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia. Jama 2018;320:2542–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khera R, Dharmarajan K, Wang Y, et al. Association of the hospital readmissions reduction program with mortality during and after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. JAMA network open 2018;1:e182777–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, et al. Project BOOST: effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. Journal of hospital medicine 2013;8:421–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. BPCI Advanced. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovationmodels/bpci-advanced. Accessed September 1, 2021..

- 40.The Lewin Group. CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative Models 2–4: Year 7 Evaluation & Monitoring Annual Report. https://innovation.cms.gov/data-and-reports/2021/bpci-models2-4-yr7evalrpt Accessed May 1, 2021..

- 41.The Lewin Group, Inc. with our partners Abt Associates, GDIT, and Telligen. CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Advanced Model: Year 2 Evaluation Report. March 2021. https://innovation.cms.gov/data-and-reports/2021/bpci-yr2-annual-report Accessed September 1, 2021..

- 42.Lin E, MaCurdy T, Bhattacharya J. The Medicare access and CHIP reauthorization act: Implications for nephrology. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2017;28:2590–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng J, Kim J, Bieber SD, Lin E. Four years into MACRA: What has changed? Seminars in dialysis; 2020: Wiley Online Library. p. 26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tummalapalli SL, Mendu ML, Struthers SA, et al. Nephrologist Performance in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System. Kidney Medicine 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Program; CY 2022 Payment Policies under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment Policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; Provider Enrollment Regulation Updates; Provider and Supplier Prepayment and Post-payment Medical Review Requirements. https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2021-14973.pdf Accessed July 26, 2021.

- 46.Personal Communication. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services MIPS Value Pathways Development Team. February 2021.

- 47.Weiner D, Watnick S. The ESRD Quality Incentive Program—can we bridge the chasm? Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2017;28:1697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ajmal F, Probst JC, Brooks JM, Hardin JW, Qureshi Z, Jafar TH. Freestanding dialysis facility quality incentive program scores and mortality among incident dialysis patients in the United States. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2020;75:177–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheetz KH, Gerhardinger L, Ryan AM, Waits SA. Changes in Dialysis Center Quality Associated With the End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program: An Observational Study With a Regression Discontinuity Design. Annals of Internal Medicine 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marr J BA, Griffin S, Yee T, Esposito D, Pearson J, Houseal D, Adeleye AO. ABSTRACT: PO1135 Do Dialysis Facilities Improve Quality After Receiving a Penalty Under the ESRD Quality Incentive Program? https://www.asn-online.org/education/kidneyweek/2020/program-abstract.aspx?controlId=3444366 Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 51.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Comprehensive ESRD Care Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/comprehensive-esrd-care Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 52.Oppenheimer CC, Shapiro JR, Beronja N, et al. Evaluation of the ESRD managed care demonstration operations. Health Care Financing Review 2003;24:7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dykstra DM, Beronja N, Menges J, et al. ESRD managed care demonstration: financial implications. Health Care Financing Review 2003;24:59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pifer TB, Bragg-Gresham JL, Dykstra DM, et al. Quality of life and patient satisfaction: ESRD managed care demonstration. Health Care Financing Review 2003;24:45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arbor Research Collaborative for Health. End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Disease Management Demonstration Evaluation Report: Findings from 2006–2008, the First Three Years of a FiveYear Demonstration. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Reports/Downloads/Arbor_ESRD_EvalReport_2010.pdf Accessed July 26, 2021.

- 56.The Lewin Group. Comprehensive End-Stage Renal Disease Care (CEC) Model. Performance Year 3 Annual Evaluation Report. November 2020. https://innovation.cms.gov/data-and-reports/2020/cec-annrptpy3. Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 57.Marrufo G, Colligan EM, Negrusa B, et al. Association of the comprehensive end-stage renal disease care model with Medicare payments and quality of care for beneficiaries with end-stage renal disease. JAMA internal medicine 2020;180:852–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ESRD Treatment Choices (ETC) Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/esrd-treatment-choices-model Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 59.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Special Needs Plans. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/SpecialNeedsPlans Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 60.Powers BW, Yan J, Zhu J, et al. The beneficial effects of medicare advantage special needs plans for patients with end-stage renal disease. Health Affairs 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Becker BN, Luo J, Gray KS, et al. Association of Chronic Condition Special Needs Plan With Hospitalization and Mortality Among Patients With End-Stage Kidney Disease. JAMA network open 2020;3:e2023663–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Health Payer Intelligence. Payer Launches Value-Based Kidney Care Agreement for CKD, ESKD. https://healthpayerintelligence.com/news/payer-launches-value-based-kidney-care-agreement-for-ckd-eskd Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 63.Health Payer Intelligence. Payer Boosts MA Chronic Kidney Management Access, Patient Outcomes. https://healthpayerintelligence.com/news/payer-boosts-ma-chronic-kidney-management-access-patient-outcomes Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 64.Berns JS, Saffer TL, Lin E. Addressing financial disincentives to improve CKD care. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2018;29:2610–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin E, Chertow GM, Yan B, Malcolm E, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD. Cost-effectiveness of multidisciplinary care in mild to moderate chronic kidney disease in the United States: a modeling study. PLoS medicine 2018;15:e1002532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fishbane S, Agoritsas S, Bellucci A, et al. Augmented nurse care management in CKD stages 4 to 5: a randomized trial. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2017;70:498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen PM, Lai TS, Chen PY, et al. Multidisciplinary care program for advanced chronic kidney disease: reduces renal replacement and medical costs. The American journal of medicine 2015;128:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van Zuilen AD, Wetzels JF, Bots ML, Blankestijn PJ. MASTERPLAN: study of the role of nurse practitioners in a multifactorial intervention to reduce cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease patients. Journal of nephrology 2008;21:261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peeters MJ, van Zuilen AD, van den Brand JA, et al. Nurse practitioner care improves renal outcome in patients with CKD. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2014;25:390–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dixon J, Borden P, Kaneko TM, Schoolwerth AC. Multidisciplinary CKD care enhances outcomes at dialysis initiation. Nephrology Nursing Journal 2011;38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Curtis BM, Ravani P, Malberti F, et al. The short-and long-term impact of multi-disciplinary clinics in addition to standard nephrology care on patient outcomes. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2005;20:147–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mendu ML, Waikar SS, Rao SK. Kidney disease population health management in the era of accountable care: A conceptual framework for optimizing care across the CKD spectrum. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2017;70:122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cricket Health. https://www.crickethealth.com/ Accessed July 26, 2021.

- 74.Strive Health. https://www.strivehealth.com/ Accessed July 26, 2021.

- 75.Somatus. https://somatus.com/ Accessed July 26, 2021.

- 76.Tummalapalli SL, Peralta CA. Preparing the nephrology workforce for the transformation to value-based kidney care: Needs assessment for advancing American kidney health. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2019;14:1802–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Navaneethan SD, Jolly SE, Schold JD, et al. Development and validation of an electronic health record– based chronic kidney disease registry. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2011;6:40–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mendu ML, Ahmed S, Maron JK, et al. Development of an electronic health record-based chronic kidney disease registry to promote population health management. BMC nephrology 2019;20:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Choi M ME, Saffer T, Vassalotti J.. National Kidney Foundation Chronic Kidney Disease Change Package. https://www.kidney.org/sites/default/files/02-11-8036_jbl_ckd_change-pack-v17.pdf Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 80.Mendu ML, Tummalapalli SL, Lentine KL, et al. Measuring quality in kidney care: an evaluation of existing quality metrics and approach to facilitating improvements in care delivery. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2020;31:602–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Diamantidis CJ, Hale SL, Wang V, Smith VA, Scholle SH, Maciejewski ML. Lab-based and diagnosis-based chronic kidney disease recognition and staging concordance. BMC nephrology 2019;20:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Garimella PS, Weiner DE. Value-Based Kidney Care: Aligning Metrics and Incentives to Improve the Health of People with Kidney Disease. Am Soc Nephrol; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Verberne WR, Das-Gupta Z, Allegretti AS, et al. Development of an international standard set of value-based outcome measures for patients with chronic kidney disease: a report of the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) CKD Working Group. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2019;73:372–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nair D, Wilson FP. Patient-reported outcome measures for adults with kidney disease: Current measures, ongoing initiatives, and future opportunities for incorporation into patient-centered kidney care. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2019;74:791–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. The Milbank Quarterly 2019;97:407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Figueroa JF, Wang DE, Jha AK. Characteristics of hospitals receiving the largest penalties by US payfor-performance programmes. BMJ quality & safety 2016;25:898–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thompson MP, Waters TM, Kaplan CM, Cao Y, Bazzoli GJ. Most hospitals received annual penalties for excess readmissions, but some fared better than others. Health Affairs 2017;36:893–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen LM, Epstein AM, Orav EJ, Filice CE, Samson LW, Maddox KEJ. Association of practice-level social and medical risk with performance in the Medicare Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier Program. Jama 2017;318:453–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hsu HE, Wang R, Broadwell C, et al. Association between federal value-based incentive programs and health care–associated infection rates in safety-net and non–safety-net hospitals. JAMA network open 2020;3:e209700–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Khullar D, Schpero WL, Bond AM, Qian Y, Casalino LP. Association between patient social risk and physician performance scores in the first year of the merit-based incentive payment system. Jama 2020;324:975–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Qi AC, Butler AM, Joynt Maddox KE. The role of social risk factors in dialysis facility ratings and penalties under a Medicare quality incentive program. Health Affairs 2019;38:1101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shen JI, Chen L, Vangala S, et al. Socioeconomic factors and racial and ethnic differences in the initiation of home dialysis. Kidney medicine 2020;2:105–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schold JD, Mohan S, Huml A, et al. Failure to Advance Access to Kidney Transplantation over Two Decades in the United States. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2021;32:913–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Purnell TS, Luo X, Cooper LA, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with live donor kidney transplantation in the United States from 1995 to 2014. Jama 2018;319:49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Casalino LP, Elster A, Eisenberg A, Lewis E, Montgomery J, Ramos D. Will Pay-For-Performance And Quality Reporting Affect Health Care Disparities? These rapidly proliferating programs do not appear to be devoting much attention to the possible impact on disparities in health care. Health affairs 2007;26:w405–w14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liao JM, Lavizzo-Mourey RJ, Navathe AS. A National Goal to Advance Health Equity Through Value-Based Payment. JAMA 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Services CfMM. End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Prospective Payment System (PPS) Calendar Year (CY) 2022 Proposed Rule (CMS-1749-P) Fact Sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/end-stage-renal-disease-esrd-prospective-payment-system-pps-calendar-year-cy-2022-proposed-rule-cms Accessed July 26, 2021.

- 98.Maddox KEJ, Reidhead M, Qi AC, Nerenz DR. Association of stratification by dual enrollment status with financial penalties in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA internal medicine 2019;179:769–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shashikumar SA, Waken R, Luke AA, Nerenz DR, Maddox KEJ. Association of Stratification by Proportion of Patients Dually Enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid With Financial Penalties in the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program. JAMA internal medicine 2021;181:330–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Evaluation OotASfPa. Report to Congress: Social Risk Factors and Performance Under Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing Programs. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//171041/ASPESESRTCfull.pdf Accessed July 26, 2021. [Google Scholar]