Abstract

Objective:

To develop a drug facts label prototype for a combination mifepristone and misoprostol product and to conduct a label comprehension study to assess understanding of key label concepts.

Methods:

We followed U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance, engaged a multi-disciplinary group of experts, and conducted cognitive interviews to develop a drug facts label prototype for medication abortion. To assess label comprehension, we developed 11 primary and 13 secondary communication objectives related to indications for use, eligibility, dosing regimen, contraindications, warning signs, side effects, and recognizing the risk of treatment failure, with corresponding target performance thresholds (80%–90% accuracy). We conducted individual structured video interviews with people born with a uterus aged 12–49 years, recruited through social media. Participants reviewed the drug facts label and responded to questions to assess their understanding of each communication objective. After transcribing and coding interviews, we estimated the proportion of correct responses and exact binomial 95% confidence intervals (CI) by age and literacy group.

Results:

We interviewed 851 people (of 1,507 people scheduled); 844 were eligible for analysis; 35.7% (n=301) were ages 12–17. The overall sample met performance criteria for ten of the eleven primary communication objectives (93%–99% correct) related to indications for use, eligibility for use, the dosing regimen, and contraindications; young people met nine and people with limited literacy met eight of the eleven performance criteria. Only 79% (CI 0.76–0.82) of the overall sample understood to contact a health care professional if little or no bleeding occurs soon after taking misoprostol, not meeting the pre-specified threshold of 85.0%.

Conclusions:

Overall high levels of comprehension suggest that people can understand most key drug facts label concepts for a medication abortion product without clinical supervision and recommend minor modifications.

Precis

High levels of comprehension suggest that people can understand most key concepts of a nonprescription medication abortion drug facts label prototype without clinical supervision.

INTRODUCTION

The most prevalent medication abortion regimen in the U.S. involves taking mifepristone and misoprostol. While the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently eliminated the in-person dispensing requirement for mifepristone, they still require it be prescribed by or under the supervision of a certified healthcare professional who meets certain qualifications.1 Medication abortion is an ideal candidate for over-the-counter (OTC) use.2 The medications are extremely safe, effective, not toxic, have low potential for abuse, people can self-screen for eligibility and contraindications, and lab testing and ultrasound are not required.3–7 As more people access medication abortion without the in-person visit, evidence supporting an OTC switch grows.

Telemedicine, mail-order, and online models of care that reduce or eliminate the in-person visit are proving to be as safe, acceptable, and effective as in-person care.4,8–15 Given medication abortion’s established safety record6,16 and the need to make abortion more accessible,17–19 research assessing whether it should be moved OTC is warranted. For an OTC switch, the FDA requires label comprehension, self-selection, and actual use studies demonstrating safe use of the medications without clinical supervision.7 Label comprehension studies assess whether people can understand key concepts in the drug facts label such as indications for use, dosing regimen, eligibility, contraindications, risks, warning signs, and side effects.20 These drive the development of primary and secondary communication objectives, which, according to the FDA, should be stated a priori and achieve over 80% comprehension.20 The FDA also recommends that label comprehension studies include a general population of consumers with varying literacy levels. To move levonorgestrel emergency contraception (EC) OTC, the FDA required a separate label comprehension study among adolescents ages 17 and under.21,22 An exploratory pilot label comprehension study for an OTC medication abortion product conducted in South Africa among 100 reproductive-age women demonstrated moderate understanding of key concepts and identified areas for modifying their label which informed our drug facts label design.23

The current study developed a drug facts label prototype for a combination mifepristone and misoprostol medication abortion product and conducted a label comprehension study to evaluate understanding of key label concepts among people of varying literacy levels and ages in the U.S.

METHODS

This study included three phases: 1) development of an initial drug facts label prototype; 2) preliminary cognitive interviews to test and refine the drug facts label, and; 3) implementation of a label comprehension study assessing understanding among a large sample of people living across the U.S.

Informed by previous studies and following FDA guidance, we developed a drug facts label prototype by converting the FDA-approved prescription label for mifepristone 200 mg to the OTC format, assuming the same eligibility criteria as the prescription label.20–23 However, unlike most drug facts labels, this one describes two medications (mifepristone and misoprostol) which are taken separately, on different days and in different ways (orally and buccally). We engaged a multidisciplinary group of experts for input on the study and drug facts label design. Experts included people with experience developing drug facts labels and implementing label-comprehension studies, clinicians, researchers, an OTC switch expert, and an advisory board representing reproductive health and justice organizations, who, in their professional roles, represent the lived experiences of people with limited access to abortion.

We developed 11 primary and 13 secondary communication objectives to test label comprehension (Table 1). Key concepts included indications for use (1 question), eligibility for use (2 questions), dosing regimen (7 questions), contraindications (8 questions), warning signs (1 question), side effects (1 question) and recognizing the risk of treatment failure (4 questions). For each primary communication objective, we set a target performance threshold ranging from 80%–90% accuracy, depending upon the clinical significance (Table 1). We developed secondary communication objectives that were less critical to the safe and appropriate use of the product and did not set performance thresholds, per FDA guidance.20 The questions included in the structured interview guide used in the preliminary cognitive interviews and main study mirrored the communication objectives (see below).

Table 1.

Proportion responding correctly to each primary communication objective by age group and literacy level

| Primary communication objective Question to assess understanding (Key concept) | Study group | N | Point Estimate % | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | Performance threshold* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Product is for abortion What is this product used for? (Indications for use) | Total | 844 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 90% |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 | ||

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.92† | 0.86 | 0.96 | ||

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.98 | ||

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.98 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Ineligible if more than 10 weeks pregnant Diana is 12 weeks pregnant. According to the label, is it OK or not OK for her to use this product? (Eligibility for use) | Total | 844 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 90% |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | ||

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.99 | ||

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.99 | ||

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Take pregnancy test 4 weeks later Priya took the medication 4 weeks ago. What does the label say Priya should do? (Recognizing risk of treatment failure) | Total | 844 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 90% |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.97 | ||

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.83† | 0.77 | 0.89 | ||

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.95 | ||

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.93† | 0.89 | 0.95 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Contact health professional if pregnancy test is positive When Priya took the pregnancy test, it was positive. What does the label say Priya should do? (Recognizing risk of treatment failure) | Total | 843 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 85% |

| >=9th grade literacy | 686 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | ||

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.98 | ||

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.98 | ||

| Ages 12–17 | 300 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.99 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Seek medical help or talk to a provider if no or light bleeding within 2 days of taking misoprostol Tikka took this product and had no bleeding within 2 days of taking misoprostol. According to the label, what should Tikka do, if anything? (Recognizing risk of treatment failure) | Total | 844 | 0.79† | 0.76 | 0.82 | 85% |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.79† | 0.76 | 0.82 | ||

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.78† | 0.71 | 0.85 | ||

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.78† | 0.75 | 0.82 | ||

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.81† | 0.76 | 0.85 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Take mifepristone first Vicki is ready to take the medication. Which medication should she take first? (Dosing regimen) | Total | 844 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 85% |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.99 | ||

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.99 | ||

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | ||

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Take misoprostol 24–48 hours after taking mifepristone Vicki took the mifepristone 10 hours ago. Is it okay or not okay for her to take the misoprostol right now? (Dosing regimen) | Total | 844 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 85% |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | ||

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | ||

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.99 | ||

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 ‡ | ||

|

| ||||||

| Contraindicated if using blood thinners Claudia is taking medicine to thin her blood. What does the label say about this? (Contraindication) | Total | 844 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 80% |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.97 | ||

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.93 | ||

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.96 | ||

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.96 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Contraindicated if history of ectopic During a previous pregnancy, Abigail experienced a pregnancy outside the uterus, also called an ectopic pregnancy. She is pregnant again. Is it OK or not OK for her to use this product? (Contraindication) | Total | 844 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 80% |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | ||

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.99 | ||

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.99 | ||

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Contraindicated if history of bleeding disorder Jessica has a bleeding disorder and wants to start to use this product. Is it OK or not OK for her to use this product? (Contraindication) | Total | 844 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 80% |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.99 | ||

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.99 | ||

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | ||

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Contraindicated if history of tubal surgery Laurel had her tubes tied, also called tubal ligation, and became pregnant unexpectedly. She wants to use this product. Is it OK or not OK for her to use this product? (Contraindication) | Total | 844 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 80% |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | ||

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.95 | ||

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.97 | ||

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Average primary communication objectives correct | Total | 844 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | N/A |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | ||

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.94 | ||

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.96 | ||

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.97 | ||

Pre-specified performance threshold for the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval; Objectives that met pre-specified target performance thresholds are indicated in bold font and

indicates that the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval was below the pre-specified performance threshold

One-sided 97.5% confidence interval used for objectives that scored 100% correct; N/A not applicable.

We first conducted cognitive interviews to test initial versions of the drug facts label with 42 women aged 12–49 years living in the U.S. We recruited people from May through August 2020 through Craigslist ads and community outreach, which included posting on listservs. During video interviews we shared the drug facts label onscreen, solicited feedback, assessed understanding of key concepts, assessed literacy using the 66-item Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) or the Rapid Estimate of Adolescent Literacy in Medicine (REALM-teen) for people ages 17 and under, and collected demographic information. 24,25 People who scored 60 or below (equivalent to <9th grade literacy level) on the REALM were coded as having limited literacy. We reviewed responses throughout the interview process and revised the drug facts label language, formatting, and interview questions iteratively, until reaching saturation in participant feedback. We describe the cognitive interview methods and participants in the Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx.

We aimed to recruit 800 participants for the main label comprehension study, including a minimum of 300 young people ages 12–17 years, as requested by the FDA in the label comprehension study for EC inr adolescents.21 This sample size was set to assess whether expected comprehension met the target threshold of 90% (lower limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI)) for the primary communication objective indications for use, using an exact binomial test and setting alpha at 0.05 and power at 80%. A subgroup sample size of 300 assures that the lower limit of the 2-sided 95% CI for the comprehension rate is above 90% if comprehension is 94.5%; a subgroup sample of 150 is sufficient power to assess whether this objective was met if comprehension was 96%. We contracted with PEGUS Research, an OTC consumer behavior research organization, to recruit and interview participants. Participant eligibility criteria included being born with a uterus, ages 12–49, able to read and speak English, living in the U.S., had not participated in a PEGUS-conducted market research study in the past three months, and had a computer and internet access. From November 2020 to February 2021, PEGUS recruited through Facebook, Instagram, and community partner listservs.

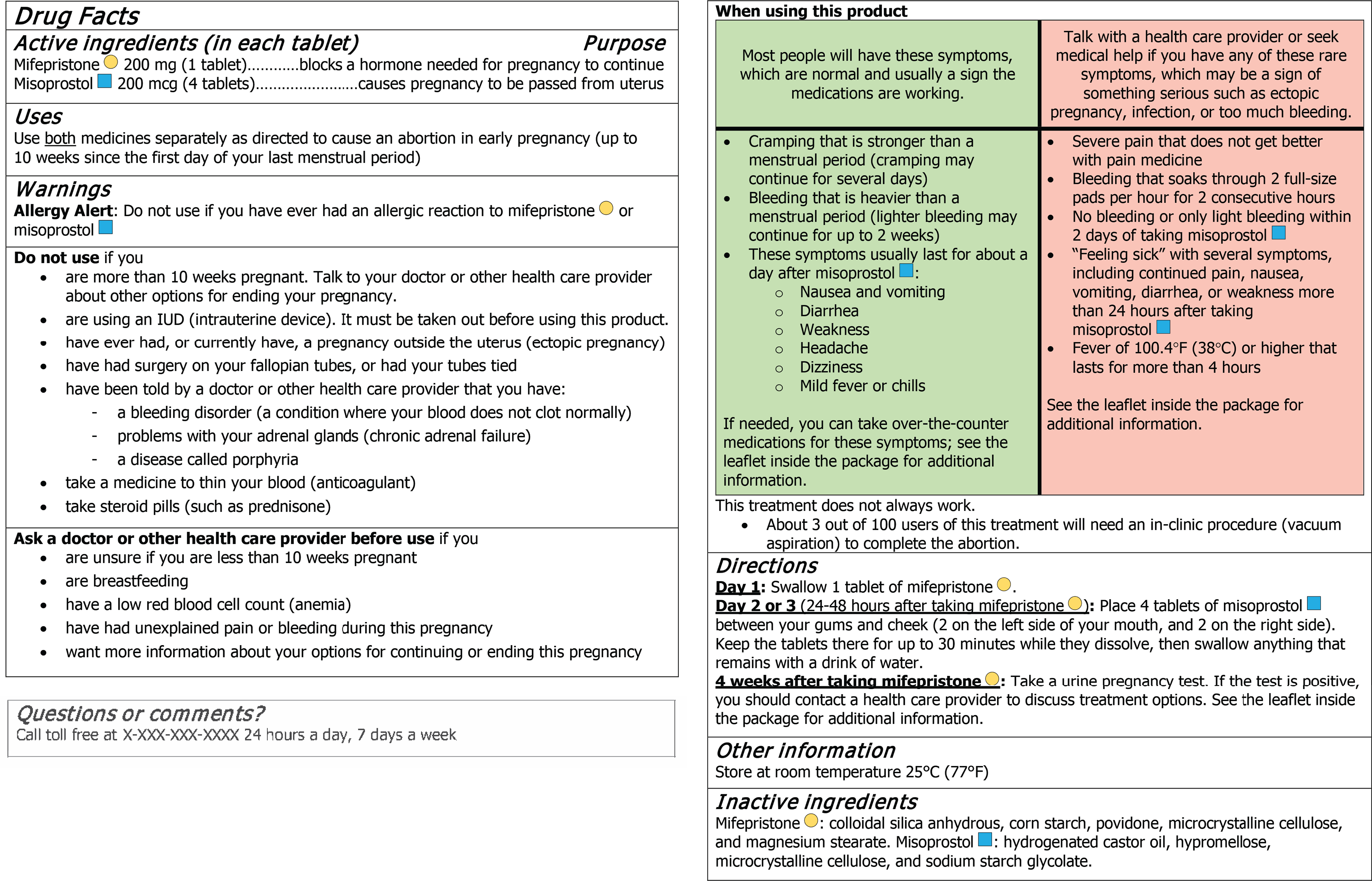

Participants self-screened for eligibility by completing a brief online survey, and those eligible scheduled an interview online or selected to be contacted to schedule an interview. Before the interview, we emailed study details to the participant. At the start of the interview, a trained interviewer obtained verbal informed consent from participants ages 18 and older, verbal assent for participants ages 12–17 and verbal consent from their parent or guardian who was present at the start of the interview. The interviewer then shared their video screen, and assessed participant literacy using the REALM, or the REALM-teen if ages 17 and under. The interviewer showed the drug facts label (Figure 1) on their screen for participants tor review, then asked them a series of questions, most of which posed hypothetical situations designed to address each primary and secondary communication objective, as listed in the first column of Tables 1 and 2. The interviewer invited the participant to refer back to the drug facts label as they were answering questions. Participants were also asked open-ended questions regarding their thoughts about the blue and yellow shapes indicating each medication and the red and green table format. At the end of the interview, we asked participants to report on a series of sociodemographic characteristics including self-reported race (according to prespecified categories), Hispanic, Latina, or Latinx ethnicity, highest level of educational attainment, employment status, gender identity, household, and pregnancy characteristics (see Table 3). We collected data on race, ethnicity, and other household characteristics in order to ensure that our sample was demographically diverse and representative of the U.S. reproductive age population as a whole.

Figure 1.

Drug facts label for a combination mifepristone–misoprostol medication abortion product.

Table 2.

Proportion responding correctly to each secondary communication objective by age group and literacy level

| Secondary communication objective Question to assess understanding (Key concept) | Study group | N | Point Estimate % | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Ineligible if unsure how many weeks pregnant Beatriz is unsure how far along she is in her pregnancy. What does the label say Beatriz should do? (Eligibility) | Total | 844 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.00 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | |

|

| |||||

| Medication doesn’t always work According to the label, if the medication is used correctly, does it always work? (Recognizing risk of treatment failure) | Total | 844 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.99 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.95 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.98 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | |

| Contraindicated if has porphyria Whitney has a disease called porphyria and is thinking about using this product. Is it OK or not OK for her to start to use this product? (Contraindication) | Total | 844 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.95 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.95 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.97 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.95 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.96 | |

|

| |||||

| Contraindicated if allergic to mifepristone Chris is allergic to mifepristone. They want to use this product. What does the label say, if anything, about that? (Contraindication) | Total | 844 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.96 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.97 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.95 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.95 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.98 | |

|

| |||||

| Contraindicated if unexplained pain or bleeding Daniela has been having unexplained pain and bleeding during her pregnancy and wants to use this product. What does the label say about that? (Contraindication) | Total | 844 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.97 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.94 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.97 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.98 | |

|

| |||||

| Contraindicated if has anemia Maria has a low red blood cell count, also called anemia. She wants to take this product. What does the label say about that? (Contraindication) | Total | 844 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.00* | |

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | |

|

| |||||

| Contact health care provider if signs of infection Sofia finished taking this product one week ago. She has been feeling sick, with a fever of 101°F, and her bleeding has not stopped. According to the label, what should Sofia do, if anything? (Warning signs) | Total | 844 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 686 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.99 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.96 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 542 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.99 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.98 | |

|

| |||||

| Take one mifepristone tablet How many tablets of mifepristone should she take? (Dosing regimen) | Total | 844 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.98 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.99 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.98 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.98 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | |

|

| |||||

| Take mifepristone orally She swallowed the mifepristone medication. Did she take the mifepristone correctly? (Dosing regimen) | Total | 844 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.97 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.98 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.96 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.97 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.98 | |

|

| |||||

| Take misoprostol 24–48 hours after mifepristone Vicki took the first medication on Tuesday at 8 am. When would be the earliest time she could take the next medication? (Dosing regimen) | Total | 844 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.89 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.92 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.73† | 0.66 | 0.80 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.89 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.91 | |

|

| |||||

| Take four misoprostol tablets Vicki is now ready to take the misoprostol. Exactly how many tablets should she take? (Dosing regimen) | Total | 844 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00* | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00* | |

|

| |||||

| Take misoprostol buccally When taking the misoprostol tablets, how should Vicki take them? (Dosing regimen) | Total | 844 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.98 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.97 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.98 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.99 | |

|

| |||||

| Recognize normal side effects Anna started taking this product this morning. She feels dizzy, has strong cramping, and has been bleeding heavier than a menstrual period, but not too heavy. According to the label, what should Anna do, if anything? (Understanding side effects) | Total | 841 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.90 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 684 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.92 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.78† | 0.70 | 0.84 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 542 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.89 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 299 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.94 | |

|

| |||||

| Average secondary communication objectives correct | Total | 844 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| >=9th grade literacy | 687 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | |

| Limited literacy | 157 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.93 | |

| Ages 18–49 | 543 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.96 | |

| Ages 12–17 | 301 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.97 | |

One-sided 97.5% confidence interval used for objectives with point estimates at 100% correct

The lower limit of the 95% confidence interval was below 80%.

Table 3.

Participant characteristics by age group and literacy level

| Age group | Literacy level | Total (N=844) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 12–17 (n=301) | Ages 18–49 (n=543) | * P value | >=9th grade (n=687) | Limited (n=157) | * P value | ||

| Demographic characteristics | n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Age group (years), mean ± standard deviation | 15.9±1.3 | 29.4±9.8 | <0.001 | 24.6±10.3 | 24.5±9.9 | 0.87 | 24.6±10.2 |

| 12–15 | 90 (29.9%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 | 71 (10.3%) | 19 (12.1%) | 0.14 | 90 (10.7%) |

| 16–17 | 211 (70.1%) | 0 (0%) | 184 (26.8%) | 27 (17.2%) | 211 (25.0%) | ||

| 18–24 | 0 (0%) | 222 (40.9%) | 174 (25.3%) | 48 (30.6%) | 222 (26.3%) | ||

| 25–34 | 0 (0%) | 141 (26.0%) | 109 (15.9%) | 32 (20.4%) | 141 (16.7%) | ||

| 35–44 | 0 (0%) | 136 (25.0%) | 112 (16.3%) | 24 (15.3%) | 136 (16.1%) | ||

| 45–49 | 0 (0%) | 44 (8.1%) | 37 (5.4%) | 7 (4.5%) | 44 (5.2%) | ||

| Race and ethnicity | 0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander (Non-Hispanic) | 39 (13.0%) | 89 (16.4%) | 87 (12.7%) | 41 (26.1%) | 128 (15.0%) | ||

| Black (Non-Hispanic) | 27 (9.0%) | 100 (18.4%) | 89 (13.0%) | 38 (24.2%) | 127 (15.2%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latinx, any race | 39 (13.0%) | 52 (9.6%) | 71 (10.3%) | 20 (12.7%) | 91 (10.8%) | ||

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 150 (49.8%) | 242 (44.6%) | 347 (50.5%) | 45 (28.7%) | 392 (46.4%) | ||

| More than one race or none of the above | 46 (15.3%) | 60 (11.0%) | 93 (13.5%) | 13 (8.3%) | 106 (12.6%) | ||

| Highest level of education | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Less than a high school diploma | 278 (92.4%) | 16 (3.0%) | 245 (35.7%) | 49 (31.2%) | 294 (34.9%) | ||

| High school diploma or equivalent | 14 (4.7%) | 68 (12.5%) | 51 (7.4%) | 31 (19.7%) | 82 (9.7%) | ||

| Some college or Associates degree | 9 (3.0%) | 226 (41.7%) | 198 (28.9%) | 37 (23.6%) | 235 (27.9%) | ||

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 0 (0%) | 232 (42.8%) | 192 (28.0%) | 40 (25.5%) | 232 (27.5%) | ||

| Working for pay full or parttime | 82 (27.2%) | 322 (59.4%) | <0.001 | 335 (48.8%) | 69 (43.9%) | 0.27 | 404 (47.9%) |

| Female gender identity | 289 (96.0%) | 533 (98.2%) | 0.06 | 665 (96.8%) | 157 (100%) | 0.02 | 822 (97.4%) |

| Limited literacy (<9th grade, <=60 points) | 46 (15.3%) | 111 (20.4%) | 0.07 | 0 (0%) | 157 (100%) | <0.001 | 157 (18.6%) |

| Household characteristics | |||||||

| Type of community where they live | 0.70 | 0.75 | |||||

| Large city | 92 (30.6%) | 164 (30.2%) | 209 (30.4%) | 47 (29.90%) | 256 (30.3%) | ||

| Suburb | 126 (41.9%) | 233 (42.9%) | 289 (42.1%) | 70 (44.6%) | 359 (42.5%) | ||

| Small city | 70 (23.3%) | 114 (21.0%) | 154 (22.4%) | 30 (19.1%) | 184 (21.8%) | ||

| Rural area | 13 (4.3%) | 32 (5.9%) | 35 (5.1%) | 10 (6.4%) | 45 (5.3%) | ||

| Geographic region in the United States | <.001 | 0.33 | |||||

| New England | 18 (6.0%) | 27 (5.0%) | 37 (5.4%) | 8 (5.1%) | 45 (5.3%) | ||

| Mid-Atlantic | 34 (11.3%) | 93 (17.1%) | 106 (15.4%) | 21 (13.4%) | 127 (15.0%) | ||

| South Atlantic | 46 (15.3%) | 117 (21.5%) | 128 (19.1%) | 35 (22.3%) | 163 (19.3%) | ||

| North Central | 57 (18.9%) | 115 (21.2%) | 131 (18.6%) | 41 (26.1%) | 172 (20.4%) | ||

| South Central | 21 (7.0%) | 66 (12.2%) | 73 (10.6%) | 14 (8.9%) | 87 (10.3%) | ||

| Mountain | 26 (8.6%) | 35 (6.4%) | 53 (7.7%) | 8 (5.1%) | 61 (7.2%) | ||

| Pacific | 99 (32.9%) | 90 (16.6%) | 159 (23.1%) | 30 (19.1%) | 189 (22.4%) | ||

| Received government assistance in the past year | 144 (47.8%) | 298 (54.9%) | <0.001 | 349 (50.8%) | 93 (59.2%) | 0.15 | 442 (52.4%) |

| Food insecurity in the past year | 31 (10.3%) | 113 (20.8%) | <0.001 | 107 (15.6%) | 37 (23.6%) | 0.02 | 144 (17.1%) |

| Difficulty paying bills in last year | 20 (6.6%) | 76 (14.0%) | 0.001 | 75 (10.9%) | 21 (13.4%) | 0.38 | 96 (11.4%) |

| Language other than English spoken at home | 43 (14.3%) | 76 (14.0%) | 0.91 | 87 (12.7%) | 32 (20.4%) | 0.01 | 119 (14.1%) |

| Pregnancy characteristics | |||||||

| Parous | 0 (0%) | 196 (36.2%) | <0.001 | 154 (22.4%) | 42 (26.8%) | 0.25 | 196 (23.25%) |

| History of abortion | <0.001 | 0.04 | |||||

| Never had an abortion | 298 (99.3%) | 488 (90.2%) | 640 (93.6%) | 146 (93.0%) | 786 (93.46%) | ||

| Medication abortion (MAB) | 2 (0.7%) | 20 (3.7%) | 14 (2.0%) | 8 (5.1%) | 22 (2.62%) | ||

| Had an abortion, but not MAB | 0 (0%) | 33 (6.1%) | 30 (4.4%) | 3 (1.9%) | 33 (3,92%) | ||

All p-values are based on a chi-square test except for continuous age which is based on a t-test.

Pegus trained all interviewers to strictly follow a script and to give no indication as to whether the respondents’ answers were correct or not. After 50 interviews, we paused the interview process to make minor modifications to the drug facts label and interview guide. In this iteration we changed the drug facts label language from “Light or no bleeding” to “No bleeding or only light bleeding”. We digitally recorded and transcribed all interviews verbatim. Interviews lasted approximately 45 minutes on average. We remunerated participants $50 for their participation in the study. All procedures received ethical approval from the University of California, San Francisco, Institutional Review Board.

We reviewed all transcribed interview transcripts and coded responses for all primary and secondary communication objectives. We coded those that were accurate according to the drug facts label as “correct,” those that demonstrated sufficient but not exact understanding as instructed on the label as “acceptable” (e.g., responded “see a doctor” instead of “do not use”), and coded clearly incorrect responses, don’t know, not sure, and skipped items as “incorrect”. We estimated the proportion and exact binomial 95% confidence intervals (CI) of correct responses by age group (ages 12–17 and ages 18–49) and literacy level (limited literacy and at or above a 9th grade reading level). We examined the proportion of “acceptable” responses if the lower bound of the CI for the primary communication objectives fell below the pre-specified performance threshold. All analyses were conducted in Stata 15.

RESULTS

A total of 2,522 people completed the screening process, of which 1,507 were eligible to participate and scheduled an interview and 851 completed an interview (851/1507, 56.5% response rate). Among those who completed the screening process (n=1507), those participating were significantly more likely to self-identify as Black race than White race and did not differ significantly by age or Hispanic, Latina or Latinx ethnicity. Reasons for ineligibility included being a healthcare professional (n=147), not having video capability (n=171), having participated in research in past 3 months (n=123), a minor without an available parent (n=87), born without a uterus (n=24), not interested (n=22), outside eligible age range (n=7), or unable to speak and understand English (n=5). We removed three people due to poor audio or recording quality, and four people because they were living outside the U.S., leaving a final analytic sample of 844. By design, over one-third (35.7%) of participants were young people ages 12–17 (Table 3). Across age groups and literacy levels, nearly half of participants self-identified as non-Hispanic White (46.4%), 15.2% as non-Hispanic Black, 15.0% as non-Hispanic Asian, Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander, 10.8% as Hispanic, Latina or Latinx, and nearly one in five (18.6%) had limited literacy scores (below a 9th grade literacy level). Participants represented all U.S. regions. Demographic and household characteristics differed significantly by age group and literacy level (see Table 3).

For 10 of the 11 primary communication objectives, point estimates (PE) for the full sample exceeded 92% and the lower bound of the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were well above pre-specified performance thresholds (Table 1). However, the communication objective “seek medical help or talk to a provider if no or light bleeding within 2 days of taking misoprostol” was not met across age groups and literacy levels. Only 79% (CI 0.76–0.82) of the full sample, 78% (CI 0.71–0.85) of people with limited literacy, and 81% (CI 0.76–0.85) of young people ages 12–17 understood that one should seek medical help if no bleeding occurs within 2 days of taking misoprostol. When we consider the 15 “acceptable” responses as correct for this objective, the PE for the full sample reaches 81% (CI 0.78–0.84), still below the performance threshold (not shown). Most incorrect responses erroneously indicated that the label says nothing or that one should do nothing if no bleeding occurs soon after taking misoprostol (n=89). While the performance threshold for “take pregnancy test 4 weeks later” was met for the total sample (PE 0.93, CI 0.91–0.95), adults (PE 0.93, CI 0.91–0.95), and among people with normal literacy (PE 0.95, CI 0.93–0.97), young people (PE 0.93, CI 0.89–0.95) and people with limited literacy (PE 0.83, 95% CI 0.77–0.89) did not meet this threshold. If we consider the 27 acceptable responses as correct, young people meet (PE 0.96, CI 0.93–0.98) but people with limited literacy (PE 0.91, CI 0.85–0.95) do not meet the threshold (not shown). On average, the full sample understood 95% (CI 0.95–0.96) of all primary communication objectives, people with limited literacy understood 92% (CI 0.90–0.94), adults understood 95% (CI 0.94–0.96), and young people understood 96% (CI 0.95–0.97).

For 11 of the 13 secondary communication objectives, PEs were above 90% across groups. For the remaining two objectives – understanding side effects and when to take the second medication – PEs were above 85% for the total sample. However, among people with limited literacy, only 78% (CI 0.70–0.84) understood that dizziness and cramping were expected side effects and 73% (CI 0.66–0.80) understood that the earliest you could take the next medication was the next day at the same time. On average, the full sample understood 95% (CI 0.95–0.96) of the secondary communication objectives, people with limited literacy understood 92% (CI 0.90–0.93), adults understood 95% (CI 0.94–0.96), and young people understood 96% (CI 0.95–0.97).

For the open-ended questions soliciting opinions about the blue and yellow shapes on the label (Figure 1), most people found these symbols helpful (86.3%), primarily to differentiate the medications (75.2%) and to understand the dosing regimen (13.3%) (not shown). Most people also found the red and green table helpful (89.9%), which 78.1% said helped to differentiate between normal or expected symptoms and the “bad” symptoms. A few people (3.9%) suggested that the table could be improved by adding simpler and clearer headings to indicate what each red and green color or column means.

DISCUSSION

Overall comprehension for this drug facts label prototype was excellent, meeting the pre-specified performance criteria for all but one primary communication objective, recognizing what to do if there is little or no bleeding. Despite the complexity of describing two different medications and dosing regimens, comprehension was markedly higher than typically reported in other label comprehension studies.26,27 Over 95% of the full sample understood that the product is used for an abortion and understood the appropriate pregnancy duration for use, and over 90% correctly identified contraindications. The one primary communication objective that did not meet its target threshold was related to understanding that lack of bleeding soon after taking misoprostol could indicate that the medication is not working and requires contacting a health professional. Lack of bleeding may be an indication that the pregnancy is continuing, or, in very rare cases, of an ectopic pregnancy. People may have had difficulty distinguishing among the many bleeding-related symptoms included on the drug facts label. Nonetheless, the point estimate of 79% achieved a moderately high level of comprehension. Changes to the label design, for example describing this concept in bold font or grouping the information on bleeding together, might improve understanding.

While people across age and literacy groups demonstrated clear understanding that this product is not intended for people more than 10 weeks pregnant or people unsure of how far along they are in pregnancy, some people interested in using this product may have difficulty accurately assessing the duration of their pregnancies. Studies suggest that while most people can self-determine pregnancy duration based on the date of their last menstrual period (LMP), this exact date can be difficult for some to recall.28 A recent study of patients seeking abortion across the U.S. found that a combination of three non-LMP questions achieved high accuracy in self-assessment of pregnancy duration; only 2.3% incorrectly self-screened as less than ten weeks’ pregnant when using their responses to whether they were 1) more than 10 weeks pregnant; 2) more than 2 months pregnant or 3) had missed 2 or more periods. Integration of these three statements into the label instructions and as part of an interactive online screening platform could help ensure that people have the best tools to self-screen for pregnancy duration with high accuracy and sensitivity.29

Young people ages 17 and under demonstrated excellent comprehension of the drug facts label, achieving comparable levels of understanding as adults across communication objectives, suggesting that young people can understand drug facts label instructions without the supervision of a licensed practitioner. Similarly, a label comprehension study for EC also found high levels of comprehension among young people.21

An important innovation in the drug facts label development was that we engaged a multi-disciplinary group of stakeholders, including a community advisory board representing reproductive justice organizations, researchers, and health care professionals to provide input into the overall research design, and drug facts label wording and format. During quarterly meetings with this diverse group of stakeholders, we considered how the intersections of race, ethnicity, gender, age, and immigration status create unique challenges and health care needs among the individuals and communities that are likely to benefit from an OTC product. While this process took over two years, it likely contributed to a drug facts label that was clearly understood by a diverse range of people. In particular, the color formatting and shapes that were added to the drug facts label, based on group discussions and early feedback, were well-received by participants. These improved people’s ability to distinguish the medications and to differentiate normal side effects from warning signs. We recommend including such colored formatting in future drug facts labels, while also pairing these with clear labels, as suggested by participants.

While this study captured a diverse range of perspectives across age, income, race, ethnicity, literacy, and geography, our response rate of 56.5% raises the possibility that there are unobserved differences between our sample and the general population. Furthermore, our sample is limited to people with access to a computer and the internet. Studies suggest that people with limited or no internet disproportionately live on low-incomes, live in rural areas, and are less likely to be confident in their ability to obtain health information.30,31 People without access to digital technology may also have limited access to facility-based abortion care and benefit from an OTC product, yet their perspectives are not captured as part of this study.32 While people with limited literacy did not meet performance criteria for three of the primary learning objectives (lower limit of the 95% CIs were below the threshold), only one point estimate was below the pre-specified performance threshold, suggesting that we may lack statistical power given the small sample size (n=157) of this group and also that they may have more difficulty understanding label instructions. Further testing of these three label concepts among people with limited literacy is warranted.

Given the excellent comprehension of this prototype label among people of all ages and literacy levels, we recommend only minor modifications to the label in a future OTC medication abortion product. To support an OTC switch, in addition to label comprehension studies, there is a need for self-selection and actual use studies demonstrating that people can take medication abortion appropriately without clinical supervision. As barriers to abortion care mount,17–19 OTC access has the potential to reduce patient burden, ensure access to abortion care earlier in pregnancy, and to offer a more person-centered model of care.33,34

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by a grant from the Society of Family Planning Research Fund (SFPRF12-MA9). At the time of the study, Dr. Ralph was supported by a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Office of Research on Women’s Health, Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health grant (2K12 HD052163). The funders had no role in the study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; or decision to submit the work for publication. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the funders.

The authors thank the members of this study’s Community Advisory Board for their significant input to improve study design and interpretation, and Rana Barar, Tanvi Gurazada, Jessica Navarro, and Sabrina Serrano for study support activities.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

Ghazaleh Moayedi disclosed that money was paid to them from Merck for the Nexplanon Clinical Training Program. Elizabeth Raymond is a salaried employee of Gynuity Health Projects. Daniel Grossman disclosed that mifepristone and misoprostol for medication abortion are not approved by the FDA for over-the-counter sale. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Presented at the National Abortion Federation Annual Meeting, April 30- May 2, 2022, Orlando, FL.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Mifeprex (mifepristone) Information. Published online December 16, 2021. Accessed December 25, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/mifeprex-mifepristone-information

- 2.Kaye J, Reeves R, Chaiten L. The mifepristone REMS: A needless and unlawful barrier to care. Contraception. 2021;104(1):12–15. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joint Statement on Abortion Access During the COVID-19 Outbreak | ACOG. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.acog.org/news/news-releases/2020/03/joint-statement-on-abortion-access-during-the-covid-19-outbreak [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raymond EG, Grossman D, Mark A, et al. Commentary: No-test medication abortion: A sample protocol for increasing access during a pandemic and beyond. Contraception. 2020;101(6):361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mark A, Foster AM, Grossman D, et al. Foregoing Rh testing and anti-D immunoglobulin for women presenting for early abortion: a recommendation from the National Abortion Federation’s Clinical Policies Committee. Contraception. 2019;99(5):265–266. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Upadhyay UD, Desai S, Zlidar V, et al. Incidence of emergency department visits and complications after abortion. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125(1):175–183. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapp N, Grossman D, Jackson E, Castleman L, Brahmi D. A research agenda for moving early medical pregnancy termination over the counter. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;124(11):1646–1652. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raymond EG, Tan YL, Comendant R, et al. Simplified medical abortion screening: a demonstration project. Contraception. 2018;97(4):292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gambir K, Garnsey C, Necastro KA, Ngo TD. Effectiveness, safety and acceptability of medical abortion at home versus in the clinic: a systematic review and meta-analysis in response to COVID-19. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(12). doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raymond E, Chong E, Winikoff B, et al. TelAbortion: evaluation of a direct to patient telemedicine abortion service in the United States. Contraception. 2019;100(3):173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chong E, Shochet T, Raymond E, et al. Expansion of a direct-to-patient telemedicine abortion service in the United States and experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contraception. 2021;104(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Upadhyay UD, Koenig LR, Meckstroth KR. Safety and Efficacy of Telehealth Medication Abortions in the US During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2122320–e2122320. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.22320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaller S, Muñoz MGI, Sharma S, et al. Abortion service availability during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a national census of abortion facilities in the U.S. Contracept X. 2021;3:100067. doi: 10.1016/j.conx.2021.100067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godfrey EM, Fiastro AE, Jacob-Files EA, et al. Factors associated with successful implementation of telehealth abortion in 4 United States clinical practice settings. Contraception. 2021;104(1):82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Upadhyay UD, Schroeder R, Roberts SCM. Adoption of no-test and telehealth medication abortion care among independent abortion providers in response to COVID-19. Contracept X. 2020;2:100049. doi: 10.1016/j.conx.2020.100049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creinin MD, Grossman DA, Planning C on PBG of F. Medication Abortion Up to 70 Days of Gestation: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 225. Obstet Gynecol 2020;136(4):e31. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson KMJ, Sturrock HJW, Foster DG, Upadhyay UD. Association of Travel Distance to Nearest Abortion Facility With Rates of Abortion. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2115530. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerdts C, Fuentes L, Grossman D, et al. Impact of Clinic Closures on Women Obtaining Abortion Services After Implementation of a Restrictive Law in Texas. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):857–864. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers C, Jones R, Upadhyay U. Predicted changes in abortion access and incidence in a post-Roe world. Contraception. 2019;100(5):367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.07.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Guidance for industry: Label Comprehension Studies for Nonprescription Drug Products. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Published April 24, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/label-comprehension-studies-nonprescription-drug-products [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raymond EG, L’Engle KL, Tolley EE, Ricciotti N, Arnold MV, Park S. Comprehension of a prototype emergency contraception package label by female adolescents. Contraception. 2009;79(3):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raymond EG, Dalebout SM, Camp SI. Comprehension of a prototype over-the-counter label for an emergency contraceptive pill product. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100(2):342–349. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02086-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapp N, Methazia J, Eckersberger E, Griffin R, Bessenaar T. Label comprehension of a combined mifepristone and misoprostol product for medical abortion: A pilot study in South Africa. Contraception. 2020;101(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, et al. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med. 1991;23(6):433–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Arnold CL, et al. Development and validation of the Rapid Estimate of Adolescent Literacy in Medicine (REALM-Teen): A tool to screen adolescents for below-grade reading in health care settings. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6). doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen BR, Mahoney KM, Baro E, et al. FDA Initiative for Drug Facts Label for Over-the-Counter Naloxone. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2129–2136. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1912403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong V, Raynor DK, Aslani P. Design and comprehensibility of over-the-counter product labels and leaflets: a narrative review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36(5):865–872. doi: 10.1007/s11096-014-9975-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schonberg D, Wang LF, Bennett AH, Gold M, Jackson E. The accuracy of using last menstrual period to determine gestational age for first trimester medication abortion: a systematic review. Contraception. 2014;90(5):480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ralph LJ, Ehrenreich K, Barar R, et al. Accuracy of self-assessment of gestational duration among people seeking abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021;0(0). doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.11.1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oshima SM, Tait SD, Thomas SM, et al. Association of Smartphone Ownership and Internet Use With Markers of Health Literacy and Access: Cross-sectional Survey Study of Perspectives From Project PLACE (Population Level Approaches to Cancer Elimination). J Med Internet Res 2021;23(6):e24947. doi: 10.2196/24947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saeed SA, Masters RM. Disparities in Health Care and the Digital Divide. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2021;23(9):61. doi: 10.1007/s11920-021-01274-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cartwright AF, Karunaratne M, Barr-Walker J, Johns NE, Upadhyay UD. Identifying National Availability of Abortion Care and Distance From Major US Cities: Systematic Online Search. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(5):e186. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fay K, Kasier J, Turok D. The no-test abortion is a patient-centered abortion. Contraception. Published online June 5, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramaswamy A, Weigel G, Sobel L, Salganicoff A. Medication Abortion and Telemedicine: Innovations and Barriers During the COVID-19 Emergency. KFF. Published June 8, 2020. Accessed June 18, 2020. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-policy-watch/medication-abortion-telemedicine-innovations-and-barriers-during-the-covid-19-emergency/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.