INTRODUCTION

Canine atopic dermatitis (CAD) is a genetically predisposed, progressive, chronically relapsing, inflammatory and pruritic skin disease with characteristic clinical features associated with immunoglobulin (Ig)E antibodies most commonly directed against environmental allergens [1]. CAD is frequently encountered in small animal clinical practice, is known to negatively impact the quality of life of affected dogs and their owners, and oftentimes requires lifelong management [2-4]. The most common and clinically significant feature of CAD is moderate to severe pruritus, which is accompanied by, and typically precedes, erythema, erythematous macular and/or papular eruptions, self-induced alopecia, excoriations, hyperpigmentation, and lichenification (Figs. 1 and 2) [5-7]. The affected skin is frequently complicated by secondary microbial infections with Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and Malassezia pachydermatis, which pose additional therapeutic challenges [6]. The distribution of skin lesions is known to vary between breeds, but generally involves the face, pinnae, ear canals, paws, axillae, ventrum, and inguinum [5-8]. Clinical signs of CAD commonly present before 3 years of age, may be either perennial or seasonal, and overlap with numerous other pruritic and inflammatory skin diseases [5]. Unfortunately, there is no definitive diagnostic test or pathognomonic clinical sign that can be used to make a diagnosis of CAD. For these reasons, clinical criteria and diagnostic algorithms have been established to assist managing clinicians and clinical researchers in making a correct diagnosis [6,7]. Interestingly, striking similarities exist between CAD and atopic dermatitis (AD) in humans (ie, atopic eczema) in their clinical and immunopathological features, therapeutic approaches, and responses to treatment and CAD has been proposed as a naturally occurring, spontaneous animal model of AD in humans [9]. The objective of this review was to provide an overview of the advancements that have been made over the past decade in understanding CAD’s complex pathogenesis as well as in the approaches to disease management.

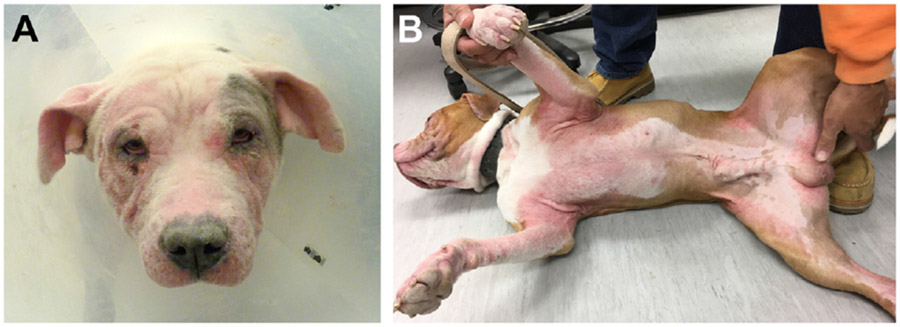

FIG. 1.

Dogs with CAD commonly present with erythema, erythematous macular and papular eruptions, self-induced alopecia, and/or excoriations that involve the (A) face, pinnae, and ear canals, as well as the (B) paws, axillae, ventrum, and inguinum. (Courtesy of the Veterinary Dermatology Service of the William R. Pritchard Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital at the University of California, Davis.)

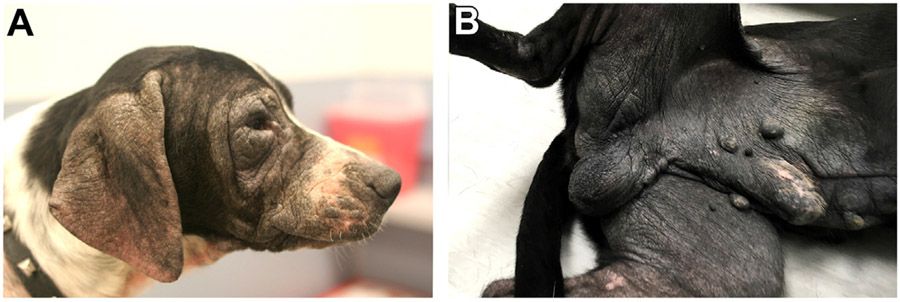

FIG. 2.

With chronicity, the affect skin in CAD may develop varying degrees of (A, B) hyperpigmentation and lichenification. These changes are not specific to CAD and can occur in other chronic skin diseases. (Courtesy of the Veterinary Dermatology Service of the William R. Pritchard Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital at the University of California, Davis.)

PATHOGENESIS

In addition to gastrointestinal signs, urticaria, and angioedema, dogs with adverse food reactions (AFR) are also well-recognized to present with clinical signs that are indistinguishable from CAD [10-12]. Although AFR and CAD have historically been considered 2 separate and distinct clinical entities, dietary components are now recognized as flare factors of CAD in some dogs [5,6,11]. Taking this into consideration, it is critically important to perform an elimination diet trial in dogs with perennial signs of CAD to evaluate for the presence of “food-induced atopic dermatitis” [6]. For the purposes of this review, the pathophysiology of food-induced AD, and the diets used for its diagnosis and management, are not discussed.

The pathogenesis of CAD is incompletely understood, but is believed to involve complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors that lead to epidermal barrier dysfunction, immune dysregulation, and dysbiosis of the cutaneous microbiome. A significant challenge faced by researchers is determining whether epidermal barrier dysfunction, immune dysregulation, and dysbiosis of the cutaneous microbiome play critical roles in disease induction, or are secondary downstream sequela. Evidence to support a role for genetic and environmental factors, epidermal barrier dysfunction, immune dysregulation, and dysbiosis of the cutaneous microbiome are discussed herein.

Genetics

Several lines of evidence have suggested a genetic basis for CAD. First, several pure breeds of dog are well-recognized to be at increased risk for developing CAD, including the golden retriever, Labrador retriever, German shepherd dog, West Highland white terrier (WHWT), and French bulldog [5,8]. Second, pedigree analyses have demonstrated the heritability of CAD [13,14]. Various approaches and methodologies have been used to investigate the genetic basis for CAD, including genome-wide linkage studies, genome-wide association studies, and candidate gene association studies [15]. Thus far, no definitive genetic markers or causative genetic variants of CAD have been identified. The candidate genes that have been implicated in CAD are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Candidate Genes that Have Been Implicated in the Pathogenesis of Canine Atopic Dermatiti

| Gene | Breed and Location | Function of the Encoded Protein |

|---|---|---|

| DPP4 |

|

A cell-surface glycoprotein (ie, CD26) involved in activation of T cells. |

| F2R |

|

A g-protein coupled receptor involved in the regulation of thrombosis. |

| FLG | The polypeptide, profilaggrin, which undergoes posttranslational modification to produce filaggrin peptide monomers. Filaggrin plays a vital role in forming the cornified cell envelope during terminal differentiation of keratinocytes. | |

| INPPL1 |

|

A protein involved in regulation of insulin function, epidermal growth factor receptor turnover, and actin remodeling. |

| MS4A2 |

|

A receptor subunit of the high-affinity immunoglobulin E receptor located on a variety of immune cells (ie, mast cells, basophils, Langerhans cells). |

| PKP2 |

|

A component of the desmosomal plaque that plays a role in maintaining keratinocyte structure and adhesion. |

| PROM1 |

|

A transmembrane glycoprotein (ie, CD133) that binds to cholesterol in cholesterol-containing plasma membranes. |

| P450 26B1 |

|

A cytochrome P450 enzyme involved in retinoic acid metabolism and adipogenesis. |

| PTPN22 | A lymphoid-specific tyrosine phosphatase involved in regulating intracellular signal transduction. | |

| RAB3C |

|

A GTPase involved in vesicular transport and has been shown to play a role in recycling major histocompatibility complex class 1 complexes. |

| RAB7A | A GTPase involved in endocytosis and vesicular transport of endolysosomes and melanosomes. | |

| SORCS2 |

|

A transmembrane receptor protein is involved in neuronal function and viability. |

| TSLPR* |

|

A subunit of the receptor complex used by “thymic stromal lymphopoietin,” a keratinocyte-derived cytokine that promotes the development of Th2-polarized immune responses and induces the sensation of itch. |

The studies that have investigated the genetic basis of CAD to date have clearly illustrated that the disease is not a simple dominant or recessive trait. Rather, CAD appears to be a complex, polygenic disorder arising from diverse genetic mutations that vary between breeds and geographic locations. For these reasons, it is now advised that all future investigations into the genetics of CAD be performed in single breeds originating from well-defined geographic regions [15,16]. Despite the advances in our understanding of the genetic basis of CAD, much remains unknown. As such, a genetic screening and breeding program to eliminate CAD in at-risk breeds remains unfeasible and unrealistic at this time [15].

Environment

The worldwide prevalence of AD in humans has increased dramatically over the past several decades and has been attributed to changes in human lifestyles and environmental exposures [23,24]. The “hygiene hypothesis” has been proposed as a possible explanation for this phenomenon. This theory postulates that exposure to diverse microbes early in life modulate the naive immune system against the development of allergic disease by stimulating T-helper-1 (Th1) and regulatory T cell (Treg) immune responses over T-helper-2 (Th2) immune responses [23-25]. Along these lines, it is theorized that increased standards of hygiene and levels of cleanliness associated with modern lifestyles decrease the diversity of infectious agents and pathogens an individual is exposed to and promote the development of allergic inflammation. Research has been performed to better define environmental triggers of AD in humans in hopes of identifying modifiable risk factors that would prevent disease induction and exacerbation [25]. For example, urban living, exposure to air pollutants, tobacco smoke, and prenatal exposure to antibiotics have each been associated with an increased risk for developing AD in humans [25]. In contrast, larger family sizes, the presence of older siblings, exposure to farm animals, and attending childhood daycare have been suggested to protect against the disease [25].

Fewer studies have been performed to define environmental risk factors associated with CAD. Environmental factors found to be associated with CAD include living in an urban environment or in areas of increasing human density, and living primarily indoors [7,26-28]. In fact, the association between an indoor environment and CAD and has led clinical researchers to accept “living in an indoor environment” as one of several diagnostic criteria for the disease [7]. Within the household, a high level of cleanliness, permitting access to upholstered furniture, and passive exposure to high levels of tobacco smoke have been identified as risk factors associated with CAD [29,30]. Other studies have found associations between CAD and being neutered, of the male sex, being born during the autumn, and residing in regions of high average annual rainfall [26,27,29]. One study found that dogs with clinical signs of CAD, as reported by their owner, were more likely to be owned by humans with either atopic rhinitis, dermatitis, and/or asthma than healthy dogs, suggesting that CAD and allergic disease in humans are influenced by mutual environmental factors [31]. Several environmental factors appear to protect against CAD as well. For example, being born and living in a rural environment, living in outdoor facilities or a detached house, living within the household a dog was born in, and regularly walking through woodlands, fields, and/or beaches have each been found to negatively associate with CAD in various studies [28,29,31-33]. Dogs living with and having regular contact with other animals (ie, dogs, cats, farm animals) and dogs living within a family with more than 2 children have also been found less likely to have CAD [28,29,31-33].

It is well-recognized that clinical signs of CAD fluctuate seasonally in association with changing concentrations of environmental allergens in some dogs [5]. Furthermore, dogs with CAD are known to develop immunoglobulin (Ig)E antibodies against environmental allergens, and allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT) remains a widely prescribed therapy known to clinically benefit approximately 60% to 70% of dogs with CAD [34,35]. Taken together, there is strong evidence to support a role for environmental factors in the pathogenies of CAD. However, discrete and definitive environmental triggers of CAD, as well as their mechanisms of action, have not yet been identified. The aforementioned environmental associations do not prove causality or cause-and-effect relationships, as numerous confounding variables are likely present in each study. It is plausible that numerous environmental triggers of CAD exist that have variable effects on disease induction and exacerbation that depend on a dog’s individual genetic background, as well as the environments and climates they are exposed to. Future prospective, longitudinal breed-specific and region-specific studies are needed to define precise environmental triggers of disease in genetically predisposed animals.

Epidermal Barrier Dysfunction

The skin forms a physical, immunologic, biochemical, and microbial barrier that separates the internal environment from the external environment [36]. Dysfunction of the epidermal barrier facilitates the percutaneous absorption of chemical irritants, microbes, and environmental allergens that stimulate the local immune system and induce Th2-polarized immune responses [37]. Th2-polarized immune responses are recognized to further impair epidermal barrier integrity and function by downregulating key structural proteins in the skin and by inducing pruritus, scratching, and self-trauma [24,37]. Epidermal barrier dysfunction is a consistent feature of humans with AD and mounting evidence suggests the same is true for CAD as well [23,24].

The stratum corneum (SC) is the outermost layer of the epidermis and is composed of terminally differentiated keratinocytes (ie, “corneocytes”) that are embedded in intercellular lipid lamellae containing cholesterol, free fatty acids, and ceramides [36]. Ceramides comprise the largest group of intercellular lipids in the SC [36]. The deposition of intercellular lipid lamellae in the nonlesional skin of dogs with CAD has been reported to be abnormal, highly disorganized, discontinuous, and reduced in number relative to the skin of healthy dogs [38,39]. The amount of total lipids and ceramides within the lesional and nonlesional skin of dogs with CAD has also been found to be significantly decreased when compared with the skin of healthy dogs, with one study showing more pronounced decreases in the lesional skin of dogs with CAD compared with nonlesional skin [40-43]. Studies have produced conflicting results when individual ceramide subclasses have been evaluated separately, with one study demonstrating global decreases in all ceramide subclasses, and other studies have reported significant decreases only in specific ceramide subclasses [41,42,44]. In addition to decreased ceramide content, the content of fatty acids in the SC of lesional and nonlesional skin of CAD has also been found to be significantly decreased when compared with the skin of healthy dogs [43,45].

Although there is evidence to support the presence of epidermal barrier dysfunction in CAD, it has not been possible to deduce whether epidermal barrier dysfunction in CAD is a primary defect underlying disease induction, or a secondary phenomenon resulting from local skin inflammation and self-trauma [37]. Nonetheless, restoring epidermal barrier function and integrity remains an integral part of the multimodal approach to managing dogs with CAD.

Immune Dysregulation

Inflammation of the skin is a hallmark finding of both humans with AD and dogs with CAD [5,23,24]. Histologically, CAD is characterized by superficial dermal infiltration of T cells, dendritic cells, eosinophils, and mast cells [5]. Various studies have demonstrated prominent Th2-polarized immune responses in CAD with variably increased levels of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in the serum, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and lesional skin, as well as increased numbers of Th2 cells in the peripheral circulation of affected dogs [46-52]. Th2-polarized immune responses have been proposed to play a critical role in the development and perpetuation of CAD by promoting humoral immunity, including the production of allergen-specific IgE antibodies, and the production and recruitment of inflammatory cells associated with hypersensitivity responses (ie, eosinophils) [53]. Allergen-specific IgE binds to the surface of canine mast cells and Langerhans cells within the skin, and are believed to play a role in CAD by mediating mast cell degranulation, allergen capture, processing, and presentation [35]. In addition to their proinflammatory properties, IL-4 and IL-13 have been shown to play a direct role in inducing pruritus by activating itch-sensing neurons that innervate the skin [54]. Dysregulated Th1 and Treg immune responses have also been documented in the skin and peripheral blood of dogs with CAD, and have been proposed to play roles in the immunopathogenesis of CAD in more chronic stages of disease [48,49,53,55].

Over the past decade, IL-31 has emerged as an important mediator of pruritus in CAD. IL-31 is a cytokine that is produced by activated T cells that preferentially exhibit a Th2-polarized cytokine profile, in addition to a variety of other innate and adaptive immune cells [56]. IL-31 mediates pruritus directly by activating somatosensory neurons that innervate the skin, as well as indirectly by upregulating the release of proinflammatory mediators from keratinocytes and immune cells [56]. IL-31 has been found to be significantly increased in the serum of client-owned dogs with naturally occurring CAD and serum levels positively correlate with the severity of pruritus [57-59]. Arguably, one of the most impactful and significant advances in CAD over the past decade has been identifying IL-31 as a novel therapeutic target for drug development. Indeed, the importance and clinical relevance of IL-31 in CAD has been further established by the significant improvements reported in pruritus and dermatitis severity in dogs with CAD following administration of lokivetmab (Cytopoint, Zoetis), a commercially available and widely prescribed caninized monoclonal antibody that binds to and neutralizes IL-31 [60-64].

Dysbiosis of the Cutaneous Microbiome

Dogs with CAD have long been recognized to suffer from recurrent microbial skin infections with S pseudintermedius and M pachydermatis, which are known to exacerbate clinical disease and complicate therapeutic responses [6]. Advances in molecular techniques and bioinformatics, and the advent of next-generation sequencing have demonstrated that the skin is inhabited by complex communities of commensal bacteria, archaea, fungi, and parasites that have historically been overlooked using conventional culture-based methods [65]. These communities, their genes, and metabolic by-products are collectively referred to as the “microbiome,” and are believed to play dynamic roles in modulating host immune responses and competing with pathogenic microbes [65,66]. The relationship between the microbiome and CAD has been studied by sequencing the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA and fungal ITS gene in relatively small numbers of dogs that have variably been receiving systemic and topical therapies.

The nonlesional skin of dogs with CAD has been shown to harbor significantly lower number of observed bacterial species (ie, lower “species richness”) relative to the same anatomic sites on healthy dogs [67]. Similarly, the bacterial microbiota inhabiting the skin of dogs with CAD and superficial pyoderma was found to be significantly less diverse relative to the skin of healthy dogs with increased relative abundances of Staphylococcus spp found across all skin sites in dogs with CAD [68]. In dogs with CAD and pyoderma, the diversity of the bacterial microbiota was found to inversely correlate with clinical disease severity scores, measures of epidermal barrier function, and relative abundances of Staphylococcus spp [68]. More importantly, treating pyoderma in dogs with CAD with oral and/or topical antimicrobial therapy was shown to decrease clinical disease severity scores and relative abundances of Staphylococcus spp, improved measures of epidermal barrier function, and increase the diversity of the bacterial microbiota across all skin sites to levels that were indistinguishable from healthy dogs [68].

Similarly, the fungal microbiota (ie, the “mycobiota”) inhabiting the nonlesional skin of dogs with allergic skin disease (ie, CAD, food-induced AD, and/or flea allergy dermatitis) has also been found to be less rich in fungal species relative to the skin of healthy dogs [69]. When the composition of Malassezia spp was evaluated at the species level, the lipid-dependent yeasts Malassezia globosa and Malassezia restricta were found to be significantly more abundant on the skin of healthy dogs, whereas M pachydermatis was found to be significantly more abundant on the nonlesional skin of allergic dogs [70]. M pachydermatis is considered a more versatile yeast that is capable of metabolizing a broader range of lipids [70]. The shift in species composition of Malassezia spp in the nonlesional skin of allergic dogs was suggested to be driven by the decreased lipid content known to occur in the skin of dogs with CAD [70].

Over the past decade, there has been a dramatic rise in the frequency of methicillin-resistant and multidrug-resistant bacterial skin infections with S pseudintermedius in canine patients [71]. This poses a concerning and increasingly common therapeutic challenge of CAD, considering the frequency with which Staphylococcal pyoderma complicates management of the disease. Although dysbiosis of the cutaneous microbiome appears to be a feature of CAD, it remains unknown what specific roles the microbiota play in CAD. Additional research is needed to further define the relationship between the cutaneous microbiome and the induction and exacerbation of CAD. Future discoveries in this field may inform the development of alternative approaches to controlling staphylococcal overgrowth and pyoderma in CAD that may decrease the need for systemic antimicrobials and the promotion of antimicrobial resistance.

TREATMENT

As previously mentioned, pruritus is a hallmark clinical sign of CAD and is often the main presenting complaint when owners of dogs with CAD seek veterinary care. As such, providing immediate and sustained anti-itch relief is a primary therapeutic goal in managing CAD. It is important to recognize that the pruritus experienced by each individual dog with CAD may be complicated by various flare factors, including exposure to environmental allergens (eg, pollens, molds, house dust mites), dietary components, concurrent uncontrolled flea allergy dermatitis, and the development of microbial skin infections. For these reasons, a multimodal approach is typically required when managing CAD to ensure all contributing flare factors of disease are identified and addressed. Unfortunately, CAD cannot be cured at present and, as a chronic skin disease, requires lifelong management. When managing CAD, it is important to determine the right combination of therapies for each individual dog that will provide a safe, effective, and affordable management strategy that the respective pet owner can reliably and willingly execute. A common pitfall in the management of CAD is a failure to identify and address all disease flare factors. Consequently, whenever a dog with CAD is poorly responsive to therapy, the managing clinician should evaluate for the presence of uncontrolled flare factors that are complicating disease management. Therapeutic recommendations for CAD need to be tailored to each individual dog, including their stage and severity of disease, using a combination of topical and systemic therapies. Although significant overlap exists, there are subtle differences in the approaches to managing acute flares and the long-term maintenance of CAD. Current recommendations for the management of acute flares and long-term maintenance of CAD are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Therapeutic Considerations for Acute Flares of Canine Atopic Dermatitis

| Therapeutic Strategy | Consider |

|---|---|

| Identification of flare factors |

|

| Topical therapy |

|

| Reduce pruritus and cutaneous inflammation |

|

TABLE 3.

Therapeutic Considerations for the Chronic Management of Canine Atopic Dermatitis

| Therapeutic Strategy | Consider |

|---|---|

| Avoidance of flare factors |

|

| Interventions to restore epidermal barrier function and integrity |

|

| Interventions to decrease pruritus and skin inflammation |

|

| Disease-modifying interventions |

|

The Role of Topical Therapies

Topical therapies used in the management of CAD are available in a variety of different formulations, including shampoos, foaming mousses, sprays, wipes, spot-ons, creams, and ointments. There are several rationales for using topical therapy in the management of CAD. First, topical therapy directly treats the affected skin, thereby reducing, and potentially eliminating, the need for systemic medications. Depending on the active ingredients of the prescribed productions, topical therapy can also reduce surface colonization of pathogenic bacteria and yeast, improve epidermal barrier function, and deliver pharmacologic antipruritic and anti-inflammatory agents to the skin. Bathing with a medicated shampoo is frequently recommended for dogs with CAD, and the selection of shampoo should be based on the desired therapeutic goal. Regardless of the active ingredients of the prescribed shampoo, the physical act of bathing a dog with CAD can remove environmental allergens from the skin and hair coat, provide mild anti-itch relief, hydrate the skin, and remove exudate, crusting and inflammatory mediators. The efficacy of bathing with medicated shampoos is likely dependent on its frequency of administration, as well as the stage and severity of skin disease [3,72]. Bathing with a medicated shampoo twice weekly is recommended for the initial management of acute flares of CAD. Depending on the extent and severity of skin disease, additional topical products (eg, medicated sprays, foaming mousses, wipes) can be applied between medicated baths. Once a dog’s skin disease is in remission and well-controlled, it is recommended to continue once-weekly bathing with a nonirritating shampoo using lukewarm water for long-term maintenance [3,72].

Antimicrobial topical therapy

As previously mentioned, dogs with CAD are at increased risk for developing recurrent microbial skin infections with S pseudintermedius and/or M pachydermatis. These microbial pathogens can also colonize the external ear canals of dogs with CAD, and are frequently associated with otitis externa. For these reasons, cytologic evaluation of the skin and ear canals of dogs with CAD should be performed to identify secondary complicating skin and/or ear infections in dogs experiencing acute flares of disease as well as in dogs with chronic disease presenting for their first-time evaluation. Topical therapy containing antimicrobial agents, including combinations of chlorhexidine and azole antifungals, are an integral part of treating secondary bacterial and yeast infections in dogs with CAD. Furthermore, topical antimicrobial therapy is also recommended for the long-term maintenance of dogs with CAD to decrease surface colonization of pathogenic microbes in attempts to prevent, or at least decrease the frequency of, recurrent skin infections. However, it is important to consider that certain topical antimicrobial products may be irritating or drying to the skin and may exacerbate epidermal barrier dysfunction and adversely affect disease management. Readers are referred to recent review articles and consensus guidelines for a more comprehensive discussion on the management of staphylococcal pyoderma and Malassezia dermatitis [71,73,74].

Topical therapy to restore epidermal barrier integrity and function

Reparation of the abnormal epidermal barrier is considered an important therapeutic goal in the management of CAD. Essential fatty acids, cholesterol, ceramides, and phytosphingosine (ie, a ceramide precursor) have been incorporated into various topical products, including spot-ons, sprays, and shampoos, with the intent of restoring the epidermal barrier’s integrity and function. In doing so, these products may decrease percutaneous absorption of irritants, allergens, and microbes, and prevent allergic sensitization and inflammation. However, limited clinical trials have been performed to evaluate the clinical efficacy of the available products.

Allerderm Spot-On (Virbac SA) is a topical product that contains ceramides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids. Allerderm has been shown to help restore the ultrastructural lipid abnormalities and significantly improve the severity of dermatitis in small numbers of dogs with CAD [39,75,76]. Similarly, significant improvements in severity of dermatitis and pruritus were reported in dogs with CAD following topical application of Dermoscent Essential 6 Spot-On (Dermoscent, LDCA, France, Bayer Animal Health, USA, Tarrytown, NJ), a topical product that contains fatty acids and essential oils [77]. More recently, a topical spot-on (Atopivet Spot-On, Bioberica S.A.U., Barcelona, Spain) containing sphingomyelin (ie, a ceramide precursor) and glycosaminoglycans (ie, hyaluronic acid) was also found to significantly improve the severity of dermatitis and pruritus in experimental laboratory model of CAD [78]. Topical emollient formulations (ie, shampoos, conditioners, and sprays) containing lipids, complex sugars, and antiseptics (Allermyl, Virbac), or phytosphingosine and raspberry oil (Douxo Calm, Ceva), have also been shown to clinically benefit dogs with CAD [79,80].

As with antimicrobial topical therapy, use of lipid-containing topical therapies are recommended for the long-term maintenance of dogs with CAD. To that goal, various antimicrobial topical therapies are now formulated with lipid complexes, thereby allowing managing clinicians and owners to treat and prevent microbial skin infections, as well as restore epidermal barrier integrity function, with one product. Many studies that have looked at topical products to address barrier dysfunction show promise but well-designed larger clinical trials are still needed to demonstrate the efficacy of the ever-increasing number of lipid-containing topical therapies marketed for CAD.

Topical antipruritic and anti-inflammatory therapies

Topical application of anti-inflammatory agents have long been a mainstay in the management of humans with mild to moderate AD [23,24]. However, frequent application of topical anti-inflammatory agents pose a unique challenge in canine patients, as dogs will often attempt to remove the products by licking, thereby increasing the risk of systemic absorption and toxicity and decreasing therapeutic efficacy. Widespread topical application of creams, gels, and ointments is challenging and impractical in dogs due to the presence of their haircoat. Nonetheless, topical therapies containing glucocorticoids and calcineurin inhibitors have been evaluated in CAD in attempts to decrease the need for systemic therapies.

There is good evidence for the use of medium potency glucocorticoid sprays, containing triamcinolone or hydrocortisone aceponate, in the short-term management of allergic pruritus [3,72,81,82]. A 0.015% triamcinolone acetonide spray (Genesis, Virbac) has been shown to be effective at treating CAD and diminishing pruritus when applied for 4 weeks following a tapering administration schedule [81]. A 0.0584% hydrocortisone aceponate spray (Cortavance; Virbac) also has demonstrated efficacy in the management of CAD [82-84]. Importantly, twice-weekly application of hydrocortisone aceponate spray has been shown to prolong the remission time in dogs with CAD between recurrences of clinical signs, demonstrating its potential role in the long-term management of CAD [85]. Both of the preceding topical glucocorticoid sprays are labeled for short-term use only and the frequency and duration of their application should be monitored closely for adverse effects of topical glucocorticoids. There are numerous topical veterinary products containing glucocorticoids, although many are untested in randomized clinical trials. Glucocorticoid-containing lotions and creams are impractical for treating large body regions, but they can be useful if the affected skin is limited to small areas, such as the paws or pinnae. The efficacy of these products and their side effects will depend on the formulation, duration of application, and potency. Chronic or habitual use of corticosteroids, particularly those of higher potency, can sometimes result in systemic side effects referable to iatrogenic hypercortisolemia from percutaneous absorption; this is of greatest concern in small-sized dogs. The most common adverse effects of prolonged application of potent, topical glucocorticoids include epidermal atrophy (ie, thinning if the skin), alopecia, superficial follicular cysts (ie, “milia”), comedones, striae, alopecia, calcinosis cutis, demodicosis, and pyoderma. Newer topical corticosteroids, like mometasone furoate and hydrocortisone aceponate, are considered “soft-steroids” as they are metabolized into inactive metabolites within the skin, thereby decreasing the risk and frequency of systemic side effects.

Tacrolimus (Protopic, Astellas Pharma, Tokyo, Japan) is a topical calcineurin inhibitor with anti-inflammatory properties that are very similar in activity to Cyclosporine A (CsA) that has been evaluated as an alternative to topical corticosteroids in the management of CAD [72]. It is available as an ointment in 2 different strengths (0.1% and 0.03%). Tacrolimus (0.1%) has been shown to be effective in the management of dogs with CAD when applied to relatively small body regions [86,87]. It is most efficacious when applied twice daily for 1 week, and then tapered as needed to control clinical signs. Tacrolimus has a slow onset of action and therefore is less useful in treating acute flares of CAD. Tacrolimus has comparatively fewer side effects relative to topical corticosteroids, but can be irritating to some patients. The clinical utility of tacrolimus in the management of CAD is somewhat limited as it is frequently cost-prohibitive for most pet owners and is challenging to apply to larger body regions.

Systemic Anti-inflammatory and Antipruritic Therapies

Systemic medications, in combination with topical therapies, are oftentimes required for the management of dogs with moderate to severe CAD. Historically, this was limited to the prescription of oral corticosteroids and oral antihistamines. Several studies have now shown that there is inconsistent evidence to support the use of antihistamines in CAD [72]. Corticosteroids have broad anti-inflammatory effects, a rapid onset of activity, and consequently can still have a useful role in the treatment of acute CAD when prescribed judiciously and appropriately. However, systemic corticosteroids should be avoided in the chronic management of CAD, whenever possible, as there are now more safe, specific, and targeted therapies available, including CsA, oclacitinib maleate (Apoquel, Zoetis), and lokivetmab (Cytopoint, Zoetis). It is important to recognize that each systemic medication is not equally efficacious in every dog with CAD and there may be different advantages or disadvantages for the selection of one medication over another, which may be dictated by their cost, associated adverse effects, or time to clinical effect. The availability of different systemic and topical therapies for CAD provides the opportunity to customize a multimodal management strategy tailored to each dog’s needs and pet owner’s capabilities. For the purposes of this review, the use of systemic corticosteroids in the management of CAD is not discussed.

CsA is considered an effective therapy for the chronic management of CAD and is available as a microemulsion formulated as either a capsule or liquid [3,72]. Cyclosporine inhibits intracellular calcineurin, which is an enzyme involved in the activation of T cells and the transcription of a number of proinflammatory cytokines. There have been several comprehensive reviews that have provided good evidence for the efficacy of microemulsified CsA in the management of CAD when administered at 5 mg/kg orally once daily. CsA has a delayed onset of activity and has been shown to improve dermatitis severity in dogs with CAD after 4 weeks of daily administration [88-90]. Many dogs with CAD are able to reduce the frequency of administration of CsA from once daily to every other day once their disease is in clinical remission; a minority of dogs are able to further decrease CsA administration to twice weekly [88]. Cyclosporine is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme (CYP3A4) in the liver. Drugs that inhibit CYP3A4 (ie, azole antifungals) or compete with P-glycoprotein (ie, ivermectin) can cause drug interactions with cyclosporine. For this reason, managing clinicians are advised to be cognizant of possible drug interactions whenever prescribing this medication. The most common side effects of CsA are gastrointestinal disturbances (ie, vomiting and diarrhea); however, gingival enlargement or overgrowth, opportunistic infections with fungal and/or mycobacterial pathogens, papillomatosis, and hirsutism are also known to occur [91].

Oclacitinib maleate (Apoquel, Zoetis) is a janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor approved for use in dogs and labeled for the control of pruritus associated with allergic dermatitis and the control of CAD in dogs at least 12 months of age. JAK enzymes are involved in intracellular signaling pathways once cytokines bind to their respective receptors. Oclacitinib maleate is most effective at inhibiting JAK1, which plays a key role in the mediating the intracellular signaling of IL- 2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-13, and IL-31 [92]. Oclacitinib maleate is rapidly absorbed with high bioavailability and a half-life of 4 to 6 hours [93]. The labeled dose of oclacitinib is 0.4 to 0.6 mg/kg given orally every 12 hours for 14 days, then given every 24 hours for long-term maintenance. Continuing at the initial induction dose is not recommended, as the risk for adverse effects from broader immune suppression increases. Several clinical trials have demonstrated its rapid speed of onset, favorable safety profile, and clinical efficacy for both acute flares and chronic management of CAD [94-96]. Reported side effects on the package insert include vomiting and diarrhea; however, their frequency were no different from placebo. Some dogs were also reported to develop neoplasia and cutaneous growths during a 6-month continuation study; however, a recent study found no association between administration of oclacitinib maleate and the onset of new cutaneous masses [97]. Per the package insert, Oclacitinib maleate has also been associated with demodicosis and bronchopneumonia in dogs younger than 12 months of age. For this reason, oclacitinib maleate should not be used in puppies or in dogs with a history of demodicosis. Oclacitinib maleate is an effective antipruritic with some anti-inflammatory properties that can be used for both the management of acute flares and ongoing chronic management of CAD.

Lokivetmab (Cytopoint, Zoetis) is a caninized monoclonal antibody that binds IL-31, thereby preventing it from interacting with its receptor and inducing pruritus. Lokivetmab has a mean half-life of 16 days and remains in circulation for several weeks [98]. The manufacturer recommends repeated subcutaneous administration either once a month, or as needed. Lokivetmab was shown to significantly decrease pruritus within 1 to 3 days when dosed at 2 mg/kg in a dose determination study [98]. No side effects reported in the original studies cited on the package insert were found to be significantly different from the placebo control group. In several studies, lokivetmab has been demonstrated to be an effective and safe therapy for both acute flares and chronic management of CAD [60-64] (see Tables 2 and 3)

Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy

Allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT) is considered a first-line treatment recommendation for dogs with CAD. ASIT attempts to promote tolerance to the allergens an affected dog is sensitized to, thereby decreasing the need for systemic anti-inflammatory agents. Formulation of ASIT is based on the results of conventional allergy tests (ie, an intradermal allergy test and/or allergen-specific IgE serology). Numerous protocols exist that follow different administration schedules and routes of administration (ie, subcutaneous, sublingual, or intralymphatic) with no proven superiority of any one ASIT protocol. Published studies evaluating the efficacy of ASIT have shown that approximately 20% of dogs with CAD have an excellent response to ASIT with complete remission of clinical signs and discontinuation of all other therapies, whereas another 40% to 50% have a satisfactory response with improved clinical signs and/or a decrease in need for concurrent therapies, and the remaining 30% to 40% show insufficient response to find ASIT as a beneficial therapy [99]. In addition to managing the clinical signs of CAD, ASIT is also believed to halt, or at least slow down, the progression of disease over time. When effective, ASIT is likely associated with an increase in Treg cells, which may play a role in improving the immune dysregulation noted in CAD [100]. When ASIT is prescribed to dogs with CAD, it is recommended to be continued for at least 12 months to be able evaluate its clinical benefit. Side effects are uncommon and include localized injection site reactions and transient pruritus. Rarely, systemic side effects (ie, vomiting, diarrhea, anaphylaxis) can occur [99]. ASIT is considered a safe and effective therapy for the chronic management of CAD.

Dietary Considerations

Oral supplementation with essential fatty acids (EFAs) has long been advocated as an adjunctive therapy for CAD and has been shown to normalize lipids in the SC of dogs with CAD, similar to some topical lipid formulations [72,101]. Oral supplementation with EFAs is better suited for the chronic management of CAD as their clinical benefits, if any, may not be seen for several months [72]. Several EFA-containing commercial diets have been developed and marketed for the management of allergic skin disease. However, very few clinical trials have been performed to demonstrate their utility and efficacy in the management of CAD.

FUTURE AVENUES TO CONSIDER

AD is a heterogeneous disease in humans that is characterized by a variety of subtypes (ie, also known as “endotypes”) that can be stratified by age, ethnicity, disease chronicity, and severity [24,102]. Ongoing research is being performed to define the specific molecular and cellular mechanisms that characterize each subtype [102]. For example, specific cytokine profiles and epidermal barrier defects of human AD have been shown to differ between children and adults, as well as between individuals of different ethnicities with the disease [102]. Characterizing well-defined subtypes of human AD is of particular importance and clinical relevance, as individual subtypes may respond differently to treatment [103]. Similarly, breed-specific clinical phenotypes are well-recognized to exist in CAD [8]. For example, the age of disease onset, type and distribution of skin lesions, and the predilection for skin infections with either bacteria or yeast has been shown to vary between genetically predisposed breeds [8]. Rather than representing a single disease entity, CAD may be better viewed as a clinical syndrome that is united by characteristic clinical features that originate from diverse combinations of environmental and genetic risk factors that vary depending on a dog’s age, breed, and geographic location. The development of oclacitinib maleate and lokivetmab has heralded a new era in veterinary dermatology defined by the commercial availability of small molecule inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies that target specific cytokine axes. Undoubtably, the availability of targeted therapeutics for CAD will continue to grow as the pathologic mechanisms that underly the disease are better understood. Future targeted therapies in CAD may include monoclonal antibodies that bind and neutralize the receptor subunit shared by IL-4 and IL-13 (ie, IL-4Rα), or a receptor subunit used by IL-31 (ie, IL-31RA), as has been developed for humans with AD [5,23,24]. As with endotypes of human AD, it is plausible that the breed-specific clinical phenotypes of CAD may respond differently to treatment. Further characterizing the various breed-specific clinical phenotypes of CAD may therefore optimize clinical outcomes by determining what preventative and therapeutic strategies work best for each breed. In doing so, veterinarians may start to transition from a “one-size-fits-all” or “trial by error” approach to managing dogs with CAD to an approach that is defined by personalized, precision medicine.

KEY POINTS.

Canine atopic dermatitis (CAD) is a common, genetically predisposed, chronically relapsing, progressive, pruritic, and inflammatory skin disease with characteristic clinical features and well-defined breed predispositions.

The pathogenesis of CAD is incompletely understood but is believed to involve complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors that lead to epidermal barrier dysfunction, immune dysregulation, and dysbiosis of the cutaneous microbiome.

CAD is a lifelong disease that requires chronic management that involves combinations of topical and systemic therapies that need to be tailored to each individual dog and dog-owner.

CLINICS CARE POINTS.

Educating clients that CAD is a lifelong and progressive disease that requires chronic management will help set realistic expectations, increase owner compliance, and decrease owner frustration.

Dogs with well-controlled CAD that flare despite no recent therapeutic changes should be evaluated for the development of secondary skin infections and/or exposure to fleas. Also consider dietary indiscretion in those dogs with a confirmed food-induced component to their allergic skin disease.

Frequent antimicrobial topical therapy is often sufficient as a sole therapy to resolve mild to moderate superficial pyoderma in dogs with CAD and is recommended to avoid the promotion of antimicrobial resistance.

Dogs experiencing an acute flare of CAD associated with significant inflammation of the ear canals often benefit from a short, tapering course of corticosteroids to establish clinical remission. Oclacitinib maleate and lokivetmab may not provide adequate anti-inflammatory effects for moderate to severe otitis externa.

Corticosteroids and oclacitinib maleate may precipitate demodicosis in canine patients so deep skin scrapings and/or trichograms should be performed in previously well-controlled CAD dogs that are developing new lesions.

Environmental allergy testing does not diagnose CAD and should only be performed in dogs that have already been determined to have CAD and if the owner is interested in ASIT. When started, ASIT should be continued for at least 1 year before evaluating its clinical efficacy. Allergen-specific IgE serology testing for food allergies is unreliable and not recommended at this time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by US National Institutes of Health grant T320D011130 (T.J.M.J).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have nothing to disclose

REFERENCES

- [1].Halliwell R Revised nomenclature for veterinary allergy. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2006;114(3):207–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Noli C, Colombo S, Cornegliani L, et al. Quality of life of dogs with skin disease and of their owners. part 2: Administration of a questionnaire in various skin diseases and correlation to efficacy of therapy. Vet Dermatol 2011;22(4):344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Olivry T, DeBoer DJ, Favrot C, et al. Treatment of canine atopic dermatitis: 2010 clinical practice guidelines from the international task force on canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2010;21:233–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hillier A, Griffin CE. The ACVD task force on canine atopic dermatitis (I): Incidence and prevalence. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2001;81:147–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bizikova P, Santoro D, Marsella R, et al. Review: clinical and histological manifestations of canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2015;26:79.e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hensel P, Santoro D, Favrot C, et al. Canine atopic dermatitis: Detailed guidelines for diagnosis and allergen identification. BMC Vet Res 2015;11(1):196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Favrot C, Steffan J, Seewald W, et al. A prospective study on the clinical features of chronic canine atopic dermatitis and its diagnosis. Vet Dermatol 2010;21:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wilhem S, Kovalik M, Favrot C. Breed-associated phenotypes in canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2011;22:143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Marsella R, De Benedetto A. Atopic dermatitis in animals and people: An update and comparative review. Vet Sci 2017;4:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Olivry T, Mueller RS. Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (7): Signalment and cutaneous manifestations of dogs and cats with adverse food reactions. BMC Vet Res 2019;15:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Olivry T, DeBoer DJ, Prélaud P, et al. Food for thought: pondering the relationship between canine atopic dermatitis and cutaneous adverse food reactions. Vet Dermatol 2007;18:390–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Mueller RS, Olivry T. Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (6): prevalence of noncutaneous manifestations of adverse food reactions in dogs and cats. BMC Vet Res 2018;14:341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shaw SC, Wood JLN, Freeman J, et al. Estimation of heritability of atopic dermatitis in Labrador and golden retrievers. Am J Vet Res 2004;65:1014–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rostaher A, Dolf G, Fischer NM, et al. Atopic dermatitis in a cohort of West Highland white terriers in Switzerland. part II: estimates of early life factors and heritability. Vet Dermatol 2020;31:276.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nuttall T The genomics revolution: will canine atopic dermatitis be predictable and preventable? Vet Dermatol 2013;24:10.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wood SH, Ollier WE, Nuttall T, et al. Despite identifying some shared gene associations with human atopic dermatitis the use of multiple dog breeds from various locations limits detection of gene associations in canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2010; 138:193–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Agler CS, Friedenberg S, Olivry T, et al. Genome-wide association analysis in West Highland white terriers with atopic dermatitis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2019;209:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Suriyaphol G, Suriyaphol P, Sarikaputi M, et al. Association of filaggrin (FLG) gene polymorphism with canine atopic dermatitis in small breed dogs. Thai J Vet Med 2011;41(4):509–17. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tengvall K, Kierczak M, Bergvall K, et al. Genome-wide analysis in german shepherd dogs reveals association of a locus on CFA 27 with atopic dermatitis. PLoS Genet 2013;9:e1003475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wood SH, Ke X, Nuttall T, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of canine atopic dermatitis and identification of disease related SNPs. Immunogenetics 2009;61:765–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Roque JB, O’Leary CA, Duffy D, et al. Atopic dermatitis in west highland white terriers is associated with a 1.3-mb region on CFA 17. Immunogenetics 2012;64:209–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Roque JB, O’leary CA, Kyaw-Tanner M, et al. PTPN22 polymorphisms may indicate a role for this gene in atopic dermatitis in West Highland white terriers. BMC Res Notes 2011;4:571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ständer S Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1136–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2020;396:345–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kantor R, Silverberg JI. Environmental risk factors and their role in the management of atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2017;13:15–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nødtvedt A, Egenvall A, Bergval K, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for atopic dermatitis in a Swedish population of insured dogs. Vet Rec 2006;159:241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nødtvedt A, Guitian J, Egenvall A, et al. The spatial distribution of atopic dermatitis cases in a population of insured Swedish dogs. Prev Vet Med 2007;78:210–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Meury S, Molitor V, Doherr MG, et al. Role of the environment in the development of canine atopic dermatitis in Labrador and golden retrievers. Vet Dermatol 2011;22:327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Harvey ND, Shaw SC, Craigon PJ, et al. Environmental risk factors for canine atopic dermatitis: a retrospective large-scale study in Labrador and golden retrievers. Vet Dermatol 2019;30:396.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ka D, Marignac G, Desquilbet L, et al. Association between passive smoking and atopic dermatitis in dogs. Food Chem Toxicol 2014;66:329–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hakanen E, Lehtimäki J, Salmela E, et al. Urban environment predisposes dogs and their owners to allergic symptoms. Sci Rep 2018;8:1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Anturaniemi J, Uusitalo L, Hielm-Björkman A. Environmental and phenotype-related risk factors for owner-reported allergic/atopic skin symptoms and for canine atopic dermatitis verified by veterinarian in a finnish dog population. PLoS One 2017;12:e0178771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nødtvedt A, Bergvall K, Sallander M, et al. A case-control study of risk factors for canine atopic dermatitis among boxer, bullterrier and west highland white terrier dogs in sweden. Vet Dermatol 2007;18:309–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Deboer DJ. The future of immunotherapy for canine atopic dermatitis: a review. Vet Dermatol 2017;28:25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pucheu-Haston CM, Bizikova P, Eisenschenk MNC, et al. Review: the role of antibodies, autoantigens and food allergens in canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2015;26:115.e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Luger T, Amagai M, Dreno B, et al. Atopic dermatitis: role of the skin barrier, environment, microbiome, and therapeutic agents. J Dermatol Sci 2021;102:142–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Santoro D, Marsella R, Pucheu-Haston CM, et al. Review: pathogenesis of canine atopic dermatitis: skin barrier and host-micro-organism interaction. Vet Dermatol 2015;26:84.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Inman AO, Olivry T, Dunston SM, et al. Electron microscopic observations of stratum corneum intercellular lipids in normal and atopic dogs. Vet Pathol 2001;38:720–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Piekutowska A, Pin D, Rème CA, et al. Effects of a topically applied preparation of epidermal lipids on the stratum corneum barrier of atopic dogs. J Comp Pathol 2008;138:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Shimada K, Yoon J, Yoshihara T, et al. Increased transepidermal water loss and decreased ceramide content in lesional and non-lesional skin of dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2009;20:541–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yoon J, Nishifuji K, Sasaki A, et al. Alteration of stratum corneum ceramide profiles in spontaneous canine model of atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol 2011;20:732–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Angelbeck-Schulze M, Mischke R, Rohn K, et al. Canine epidermal lipid sampling by skin scrub revealed variations between different body sites and normal and atopic dogs. BMC Vet Res 2014;10:152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Popa I, Remoue N, Hoang LT, et al. Atopic dermatitis in dogs is associated with a high heterogeneity in the distribution of protein-bound lipids within the stratum corneum. Arch Dermatol Res 2011;303:433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Reiter LV, Torres SMF, Wertz PW. Characterization and quantification of ceramides in the nonlesional skin of canine patients with atopic dermatitis compared with controls. Vet Dermatol 2009;20:260–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chermprapai S, Broere F, Gooris G, et al. Altered lipid properties of the stratum corneum in canine atopic dermatitis. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2018;1860:526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Olivry T, Dean GA, Tompkin MB, et al. Toward a canine model of atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol 1999;8:204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Majewska A, Gajewska M, Dembele K, et al. Lymphocytic, cytokine and transcriptomic profiles in peripheral blood of dogs with atopic dermatitis. BMC Vet Res 2016;12:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Nuttall TJ, Knight PA, McAleese SM, et al. Expression of Th1, Th2 and immunosuppressive cytokine gene transcripts in canine atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy 2002;32:789–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Schlotter YM, Rutten VPMG, Riemers FM, et al. Lesional skin in atopic dogs shows a mixed type-1 and type-2 immune responsiveness. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2011;143:20–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hayashiya S, Tani K, Morimoto M, et al. Expression of T helper 1 and T helper 2 cytokine mRNAs in freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from dogs with atopic dermatitis. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 2002;49:27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kanwal S, Singh SK, Soman SP, et al. Expression of barrier proteins in the skin lesions and inflammatory cytokines in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of atopic dogs. Sci Rep 2021;11:11418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Fruh SP, Saikia M, Eule J, et al. Elevated circulating Th2 but not group 2 innate lymphoid cell responses characterize canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2020;221:110015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Pucheu-Haston CM, Bizikova P, Marsella R, et al. Review: lymphocytes, cytokines, chemokines and the T-helper 1-T-helper 2 balance in canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2015;26:124.e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Oetjen LK, Mack MR, Feng J, et al. Sensory neurons co-opt classical immune signaling pathways to mediate chronic itch. Cell 2017;171:217–28.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hauc kV, Hügli P, Meli ML, et al. Increased numbers of FoxP3-expressing CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in peripheral blood from dogs with atopic dermatitis and its correlation with disease severity. Vet Dermatol 2016;27:26.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Furue M, Furue M. Interleukin-31 and pruritic skin. J Clin Med 2021;10:1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gonzales AJ, Humphrey WR, Messamore JE, et al. Interleukin-31: Its role in canine pruritus and naturally occurring canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2013;24:48.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Messamore JE. An ultrasensitive single molecule arrary (simoa) for the detection of IL-31 in canine serum shows differential levels in dogs affected with atopic dermatitis compared to healthy animals. Vet Dermatol 2017;28:546. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Chaudhary SK, Singh SK, Kumari P, et al. Alterations in circulating concentrations of IL-17, IL-31 and total IgE in dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2019;30:383.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Tamamoto-Mochizuki C, Paps JS, Olivry T. Proactive maintenance therapy of canine atopic dermatitis with the anti-IL-31 lokivetmab. can a monoclonal antibody blocking a single cytokine prevent allergy flares? Vet Dermatol 2019;30:98.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Michels GM, Ramsey DS, Walsh KF, et al. A blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose determination trial of lokivetmab (ZTS-00103289), a caninized, anti-canine IL-31 monoclonal antibody in client owned dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2016;27:478.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Moyaert H, Van Brussel L, Borowski S, et al. A blinded, randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of lokivetmab compared to ciclosporin in client-owned dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2017;28:593.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Souza CP, Rosychuk RAW, Contreras ET, et al. A retrospective analysis of the use of lokivetmab in the management of allergic pruritus in a referral population of 135 dogs in the western USA. Vet Dermatol 2018;29:489.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Szczepanik M, Wilkołek P, Gołyński M, et al. The influence of treatment with lokivetmab on transepidermal water loss (TEWL) in dogs with spontaneously occurring atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2019;30:330.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Rodrigues Hoffmann A The cutaneous ecosystem: the roles of the skin microbiome in health and its association with inflammatory skin conditions in humans and animals. Vet Dermatol 2017;28:60.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Bjerre RD, Bandier J, Skov L, et al. The role of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2017;177:1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Rodrigues Hoffmann A, Patterson AP, Diesel A, et al. The skin microbiome in healthy and allergic dogs. PLoS One 2014;9:e83197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bradley CW, Morris DO, Rankin SC, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of the skin microbiome and association with microenvironment and treatment in Canine Atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2016;136:1182–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Meason-Smith C, Diesel A, Patterson AP, et al. What is living on your dog’s skin? Characterization of the canine cutaneous mycobiota and fungal dysbiosis in canine allergic dermatitis. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2015; 91:fiv139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Meason-Smith C, Olivry T, Lawhon SD, et al. Malassezia species dysbiosis in natural and allergen-induced atopic dermatitis in dogs. Med Mycol 2020;58:756–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Morris DO, Loeffler A, Davis MF, et al. Recommendations for approaches to methicillin-resistant staphylococcal infections of small animals: diagnosis, therapeutic considerations and preventative measures. Vet Dermatol 2017;28:304.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Olivry T, DeBoer DJ, Favrot C, et al. Treatment of canine atopic dermatitis: 2015 updated guidelines from the international committee on allergic diseases of animals (ICADA). BMC Vet Res 2015;11:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Bond R, Morris DO, Guillot J, et al. Biology, diagnosis and treatment of malassezia dermatitis in dogs and cats clinical consensus guidelines of the world association for veterinary dermatology. Vet Dermatol 2020;31:28–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Hillier A, Lloyd DH, Weese JS, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy of canine superficial bacterial folliculitis (antimicrobial guidelines working group of the international society for companion animal infectious diseases). Vet Dermatol 2014;25:163.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Marsella R, Gilmer L, Ahrens K, et al. Investigations on the effects of a topical ceramides-containing emulsion (allerderm spot on) on clinical signs and skin barrier function in dogs with topic dermatitis: a double-blinded, randomized, controlled study. Intern J Appl Res Vet Med 2013;11:110–6. [Google Scholar]

- [76].Fujimura M, Nakatsuji Y, Fujiwara S, et al. Spot-on skin lipid complex as an adjunct therapy in dogs with atopic dermatitis: an open pilot study. Vet Med Int 2011;2011:281846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Blaskovic M, Rosenkrantz W, Neuber A, et al. The effect of a spot-on formulation containing polyunsaturated fatty acids and essential oils on dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet J 2014;199:39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Marsella R, Segarra S, Ahrens K, et al. Topical treatment with sphingolipids and glycosaminoglycans for canine atopic dermatitis. BMC Vet Res 2020;16:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Reme CA, Mondon A, Calmon JP, et al. Efficacy of combined topical therapy with antiallergic shampoo and lotion for the control of signs associated with atopic dermatitis in dogs. Vet Dermatol 2004;15:33. [Google Scholar]

- [80].Bourdeau P, Bruet V, Gremillet C. Evaluation of phytosphingosine-containing shampoo and micro emulsion spray in the clinical control of allergic dermatoses in dogs: preliminary results of a multicentre study. Vet Dermatol 2007;18:177–8. [Google Scholar]

- [81].DeBoer D, Schafer JH, Salsbury CS, et al. Multiple-cen-ter study of reduced-concentration triamcinolone topical solution for the treatment of dogs with known or suspected allergic pruritus. Am J Vet Res 2002;63:408–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Nuttall T, Mueller R, Bensignor E, et al. Efficacy of a 0.0584% hydrocortisone aceponate spray in the management of canine atopic dermatitis: a randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Vet Dermatol 2009;20:191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Nuttall TJ, McEwan NA, Bensignor E, et al. Comparable efficacy of a topical 0.0584% hydrocortisone aceponate spray and oral ciclosporin in treating canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2012;23:4.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Nam EH, Park SH, Jung JY, et al. Evaluation of the effect of a 0.0584 % hydrocortisone aceponate spray on clinical signs and skin barrier function in dogs with atopic dermatitis. J Vet Sci 2012;13(2):187–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Lourenço AM, Schmidt V, São Braz B, et al. Efficacy of proactive long-term maintenance therapy of canine atopic dermatitis with 0.0584% hydrocortisone aceponate spray: a double-blind placebo controlled pilot study. Vet Dermatol 2016;27:88.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Bensignor E, Olivry T. Treatment of localized lesions of canine atopic dermatitis with tacrolimus ointment: a blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Vet Dermatol 2004;15:56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Marsella R, Nicklin CF, Saglio S, et al. Investigation on the clinical efficacy and safety of 0.1% tacrolimus ointment (Protopic®) in canine atopic dermatitis: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Vet Dermatol 2004;15:294–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Steffan J, Favrot C, Mueller R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of cyclosporin for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in dogs. Vet Dermatol 2006;17:3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Olivry T, Foster AP, Mueller RS, et al. Interventions for atopic dermatitis in dogs: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Vet Dermatol 2010;21:4–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Olivry T, Bizikova P. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials for prevention or treatment of atopic dermatitis in dogs: 2008-2011 update. Vet Dermatol 2013;24:97.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Archer TM, Boothe DM, Langston VC, et al. Oral cyclosporine treatment in dogs: a review of the literature. J Vet Intern Med 2014;28:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Gonzales AJ, Bowman JW, Fici GJ, et al. Oclacitinib (APOQUEL®) is a novel janus kinase inhibitor with activity against cytokines involved in allergy. J Vet Pharmcol Ther 2014;37:317–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Collard WT, Hummel BD, Fielder AF, et al. The pharmacokinetics of oclacitinib maleate, a janus kinase inhibitor, in the dog. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2014;37:279–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Cosgrove SB, Wren JA, Cleaver DM, et al. A blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of the J anus kinase inhibitor oclacitinib (Apoquel®) in client-owned dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2013;24:587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Cosgrove SB, Wren JA, Cleaver DM, et al. Efficacy and safety of oclacitinib for the control of pruritus and associated skin lesions in dogs with canine allergic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2013;24:479.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Cosgrove SB, Cleaver DM, King VL, et al. Long-term compassionate use of oclacitinib in dogs with atopic and allergic skin disease: safety, efficacy and quality of life. Vet Dermatol 2015;26:171.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Lancellotti BA, Angus JC, Edginton HD, et al. Age- and breed-matched retrospective cohort study of malignancies and benign skin masses in 660 dogs with allergic dermatitis treated long-term with versus without oclacitinib. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2020;257:507–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Michels GM, Ramsey DS, Walsh KF, et al. A blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose determination trial of lokivetmab (ZTS-00103289), a caninized, anti-canine IL-31 monoclonal antibody in client owned dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2016;27:478.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Mueller R Allergen-specific immunotherapy. In: Noli C, Foster A, Rosenkrantz W, editors. Veterinary allergy. West Sussex (UK): John Wiley and Sons; 2014. p. 85–9. [Google Scholar]

- [100].Keppel KE, Campbell KL, Zuckermann FA, et al. Quantitation of canine regulatory T cell populations, serum interleukin-10 and allergen-specific IgE concentrations in healthy control dogs and canine atopic dermatitis patients receiving allergen-specific immunotherapy. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2008;123:337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Popa I, Pin D, Remoué N, et al. Analysis of epidermal lipids in normal and atopic dogs, before and after administration of an oral omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid feed supplement. A pilot study. Vet Res Commun 2011;35:501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Czarnowicki T, He H, Krueger JG, et al. Atopic dermatitis endotypes and implications for targeted therapeutics. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019;143:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Cabanillas B, Brehler A, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis phenotypes and the need for personalized medicine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;17:309–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]