Abstract

The Biden-Harris Administration’s FY22 budget includes $1.6 billion to the Community Mental Health Services Block Grants, more than double the FY21 allocation, given the rising mental health crises observed across the nation. This is timely since there have been two inter-related paradigm shifts: one giving attention to the role of environmental context as central in mental health outcomes; and a second moving upstream to earlier mental health interventions at the community level rather than only at the individual level. An opportunity to re-imagine and redesign the agenda of mental health research and service delivery with marginalized communities opens the door to more community-based interventions of care. This involves establishing multi-sector partnerships to address the social and psychological needs that can be addressed at the community-level rather than clinical level. This will require a shift in training, delivery systems and reimbursement models. We describe the scientific evidence justifying these programs and elaborate on opportunities to target investments in community mental health that can reduce disparities and improve well-being for all. We select levers where there is some evidence that such approaches matter substantially, are modifiable, and advance the science and public policy practice. We finalize with specific recommendations and the logistical steps needed to support this transformational shift.

Keywords: Community-level interventions, Disparities, Social determinants of health, Partnerships, Research agenda

The dominant model of mental healthcare in the United States (US) is individual therapy and pharmacological treatment provided by highly trained mental health professionals. However, healthcare professionals have been prompted to shift their conceptualization of care from a focus on the individual to structural factors (e.g., inequalities in wealth, education, neighborhood conditions) linked to mental health outcome disparities (1). For example, the time lag between seeking mental health services and actually receiving care is compounded for many people of color, who are more likely than whites to have severe and persistent mental health conditions yet less likely to access high quality care (2). This is due in part to cultural mistrust (3), racism and discrimination from medical establishments (4), historical traumas and oppression, (5) and under insurance (6). Research consistently demonstrates that Medicaid beneficiaries who are Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Alaska Native on average experience poorer outcomes and more barriers to care compared to white beneficiaries (7). Given the evidence that the quality of mental healthcare for marginalized individuals has not meaningfully improved in the past 20 years (6), it is imperative that we, as a field, answer the long-standing calls for a paradigm shift to make mental healthcare more equitable.

Why a Public Health Approach is Needed to Change the Tide

Efforts towards community-based mental health services increased in the early 1960’s with the passing of the Community Mental Health Act and creation of Medicaid (8), which contributed many advancements in our current model, such as the prioritization of interdisciplinary team-based approaches and evidence-based care (9). However, significant discrepancies in the accessibility and effectiveness of community-based mental healthcare have persisted, due, in part, to inadequate funding (10), high costs of effective services, insufficient insurance payment for providers (9), and the severe lag in translation from research to clinical practice (11).

Community-based mental health services are important for reducing inequities in mental health outcomes. Yet it is unlikely that place-based clinical services alone will reduce inequities anytime soon, largely due to the influence of social determinants of health, shortage of workers in behavioral health professions, and the maldistribution and lack of affordability of professional therapists and medication prescribers in the workforce (12). Nonetheless, there are factors that are modifiable now, such as the low rate of psychiatrists participating in Medicaid (13), which might be increased through Medicaid payment reforms that raise rates to be comparable to Medicare and private insurance (14). Virtual delivery has also reduced disparities in access to mental healthcare (15). And beyond in-person or virtual services, there is also widespread recognition that interpersonal, institutional, community, and policy interventions have a powerful role in influencing mental health (16). Thus, the mental health field has a lot to learn from public health models, which reach more of the nation’s population through the provision of resources that are not only more affordable and accessible, but are also multi-level (17).

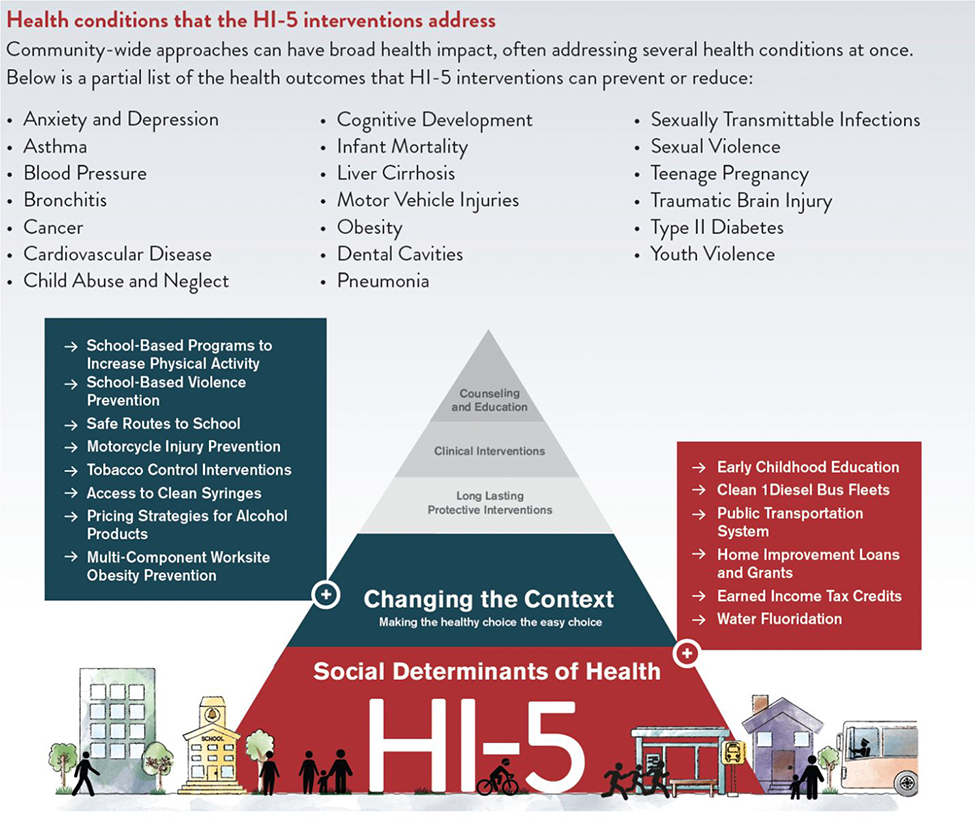

The Health Impact in Five Years (HI-5) initiative is one such framework (18) that emphasizes the importance of community approaches to improve health and exemplifies how investing in these approaches could serve to reduce inequities in communities of color. The HI-5 highlights non-clinical community-level approaches with evidence of positive health impacts within five years as well as cost-effectiveness within the lifetime of the population. The HI-5 pyramid published by the Centers for Disease Control (18) (Figure 1, re-produced with permission) illustrates five tiers of public health interventions. The bottom two tiers - Social Determinants of Health, and Changing the Context (i.e., “making the healthy choice the easy choice”) - are wider and thus reflect approaches with the greatest potential for widespread population impact.

Figure 1:

The CDC’s Health Impact in Five Years Framework

Figure re-produced with permission from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Source: The CDC Health Impact in Five Years [Internet]. Office of the Associate Director for Policy and Strategy; 2018. Available from: www.cdc.gov/hi5

In this paper, we present interventions that have sound evidence of improving mental health (e.g., decreasing or preventing clinical symptoms) or mental health-related outcomes (e.g., increasing quality of life or mental health literacy) among people of color in the U.S. within five years by addressing social determinants of health or changing the context to make the healthy choice the easy choice. In Tables 1–3, we describe the interventions selected and summarize evidence of their impact on mental health and mental health-related outcomes. These interventions are not an exhaustive list but rather serve as illustrative examples of possible investments. Similar to the CDC’s process of developing the HI-5 (18), we searched the Community Guide for interventions listed as “Recommended,” and searched the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation County Health Rankings and Roadmaps for interventions listed as “Scientifically Supported.” We also used search engines (e.g., PubMed, PsycInfo) to identify programs that met our criteria. In selecting the programs, we aimed to identify roughly four per age group - youth, adults, and older adults - so as to cover the lifespan. We also tried to select interventions which represent the different social determinants of health (e.g., income, housing, employment, nutrition), and reflect multiple ways of changing the context (e.g., policies that make it easier to save money for college, parks nearby that make it easier to exercise or socialize, integrated mental-physical health programs that make it easier to prevent disability).

Table 1.

Children and Adolescents: Summary of Included Studies

| Intervention | Description | Study design and study N | Mental health and mental health-related outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Universal school meal programs | State and federal government-funded programs that provides free meals to all students in public schools K-12. Implemented in Maine, California, and Massachusetts. | Longitudinal - interview assessments with students (N = 97) in 4th–6th grade and their parents, before and 6-months after the start of a universal free breakfast program in 3 Boston Public Schools (23) | Increased daily nutrient intake was associated with improvements in psychosocial functioning, as measured by the Pediatric Symptom Checklist |

| Longitudinal (N = 133) and cross-sectional (N = 1627) study of children in public schools (22) | Reductions in hyperactivity, anxiety, and depression symptoms | ||

| 2. Child Development Accounts (CDAs), also called Child Savings Accounts (CSAs) | Savings accounts – with public and/or private funding - often started at birth. The individual can begin to withdraw funds at age 18 to help pay for college, buy a home, or start a business. Ex: Maine has a universal, automatic program with participation of 100% of newborns in the state | Experimental study with adolescents (N = 267) randomly assigned an intervention or control group (32) | Improved mental health functioning as contrasted to control group |

| Randomized controlled trial where children and their caregiver(s) were assigned to CDAs built on the existing Oklahoma 529 College Savings Plan (n = 1,358) or control (n = 1, 346) group, and followed up after 4 years (31)(34) | Enhanced socio-emotional development outcomes; decrease in mothers’ depression symptoms as compared to control group; greater impact among families with lower income or lower education | ||

| 3. Comprehensive Behavioral Health Model of Boston Public Schools | Tiered model of mental health prevention and intervention currently in 68 Boston Public Schools (39). Tier I (Prevention, for all students) includes teacher and parent consultation, professional development, universal socio-emotional learning curriculum and universal screening. Tier II (Targeted, for some students) includes small group intervention and classroom managements. Tier III (Intensive, for a few students) includes testing, counseling, and crisis work. | Longitudinal study of 1,200 students at 14 participating elementary schools (K-5) over a 3 year period (40); Universal screening data was collected in Fall 2013, 2014, and 2015, and included the teacher-reported Behavior Intervention Monitoring Assessment (BIMAS-2) | Students with “some risk” or “high risk” on the BIMAS-2 screener experienced clinically meaningful improvements in the following BIMAS-2 scales: conduct, negative affect, cognitive attention, and social functioning; Gains in year 1 were sustained into year 2 and no negative effects were observed for students with normative social, emotional, and behavioral health. |

| 4. Community-based interventions delivered by paraprofessionals in afterschool recreational programs | Workforce support –a model of mental health consultation, training, and support, to enhance benefits of publicly-funded recreational afterschool programs in communities of concentrated poverty. | Randomized controlled trial of 3 afterschool sites (n = 15 staff, 89 children) and 3 demographically matched comparison sites (n = 12 staff, 38 children) aiming to assess the feasibility and impact of the workforce support intervention on program quality and children’s psychosocial outcomes (42) | Modest improvements in children’s social and behavioral functioning compared to the demographically matched sites |

| The Fit2Lead intervention is a park-based youth mental health promotion program involving activities for physical activity, meditation, resilience, and life skills. | Open trial design (N = 9 parks) with 198 youth participating in Fit2Lead program, who completed questionnaires before the intervention and after (end of the year); Youth were ages 9–15, in middle-school, predominantly Black and/or Latinx and living in low-income neighborhoods with high rates of community violence (45) | Youth’s and parents’ mental health remained stable over the course of a school year, indicated by no significant change in self-reported mental health before and after the intervention. |

Table 3.

Older Adults: Summary of Included Studies

| Intervention | Description | Study design and study N | Mental health and mental health-related outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Green and blue spaces | Expansions of green (e.g., parks, fields, gardens) and blue (e.g., oceans, lakes) spaces in neighborhoods. Exposure to green and blue natural environments also promotes increased social interactions and exercise. | Cluster randomized trial of greening vacant urban land (74); 442 community-dwelling adults living within 110 vacant lot clusters assigned to 3 study groups: greening, trash cleanup, or no intervention | Decrease in self-reported depression symptoms in the intervention versus control condition |

| Systematic review of 35 quantitative studies, most conducted between 2012–2017 (77); The authors identified 22 studies as being of “good quality” | The 35 studies included had a range of exposures and outcomes, but overall, the evidence suggests a positive association between exposure to outdoor green space and mental health and wellbeing | ||

| Cross-sectional study of 249,405 Medicare Beneficiaries living in Miami-Dade County, Florida (72); analyzed the association of changes in block-level greenness (vegetative presence) with individuals’ mental health outcomes | An increase in the block-level of greenness from 1 standard deviation below the mean to 1 above the mean was associated with lowering the odds of depression by 37% in low-income neighborhoods, 27% in medium-income neighborhoods, and 21% in high-income neighborhoods | ||

| 2. Senior centers offering health promotion activities | Also referred to as “adult day service centers” in the scientific literature, these centers are community organizations for older adults and their caregivers that provide a range of resources such as adult education, health promotion activities, and opportunities for socializing. | Systematic review of 61 studies (83) evaluating the effectiveness of adult day service centers at improving caregiver outcomes (19 studies), participant health outcomes (39 studies), and adult day services and healthcare utilization (10 studies); 8 studies were randomized controlled trials, and the rest were longitudinal, quasi-experimental, or cross-sectional | The majority of quasi-experimental studies assessing participant depression and quality of life found greater improvements for intervention participants compared to controls; Most quasi-experimental studies assessing caregiver burden and stress found greater improvements for intervention caregivers compared to their controls |

| 3. Community-based disability prevention programs | A dual exercise and psychosocial program for older adults. Delivered by para-professionals either virtually, in-person, or hybrid. Available in English, Spanish, Mandarin, and Cantonese | Randomized controlled trial (84) involving 307 participants (intervention = 153; control = 154) in Massachusetts, New York, Florida, and Puerto Rico; most participants were Asian or Latinx | Compared to people receiving enhanced usual care, people in the intervention group experienced reductions in mood symptoms at 6 and 12 months |

| “EnhanceFitness” A low-cost group exercise program implemented across a range of community settings (e.g., religious institutions, recreational and senior centers) | Randomized controlled trial (89) involving 100 older adults (intervention = 53; control = 47) | After 6 months people in the intervention group had fewer depressive symptoms compared people in the control group | |

| Pre and post study (90) inclusive of older adults (n = 382) | Decreased social isolation and loneliness | ||

| “EnhanceWellness” pairs older adults with health and wellness coaches trained in motivational interviewing. | Five-state dissemination of community-based program. Within-group pre and post study (85) of older adults with chronic illness (n = 224) | Among the participants completing the one-year follow-up, there was a significant decrease in their depression symptom severity from enrollment to one-year follow-up | |

| 4. Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) | 6-week peer-led education program designed to help older adults gain skills and improve confidence to better manage chronic conditions | Meta-analysis of 18 studies on CDSMP outcomes among small English-speaking groups (93) | Small to moderate improvements in all measures of psychological health at 4 to 6 months and 9 to 12 months; Significant improvements in energy, fatigue, and selfrated health (4 to 6 months only), cognitive symptom management (4 to 6 months and 9 to 12 months) |

| Randomized community-based outcome trial (94) of the Spanish-language version of the CDSMP, with Spanish speakers (mean age 57) with heart disease, lung disease, or type 2 diabetes; Participants were randomized to the treatment group (n = 327) or the waitlist usual-care control group (n = 224) | At 4 months, intervention participants showed improved health status, health behavior, and self-efficacy and fewer emergency room visits, compared with people in usual care; At 1 year, intervention participants (n = 271 maintained these improvements and were significantly different from their baseline scores |

All of the interventions included in this paper were evaluated in real-world settings, expanding on the generalizability of the results. Assessments in real-world settings also minimize the gaps between research evidence production and program implementation – gaps such as time, adaptations required, and differences in the resources available. Of the interventions we included, most (10 out of 13) have an experiment cited. The remaining three interventions were evaluated through longitudinal studies (school meals and the comprehensive behavioral health model in schools) and participatory action research with an open trial design (Fit2Lead park program), which are both useful methods for program evaluation when randomization is not feasible or ethical (19). Longitudinal and open trial designs conducted by academic-community partnerships are also well-suited for research on preventive interventions with children and adolescents (20) and for research testing mechanisms to reduce inequality (21).

Identifying Community Factors, Interventions, Programs or Policies as Ideal Targets for Improving Community Mental Health across the Lifespan

Children and Youth

Social Determinants

Universal school meal programs provide free breakfast and/or lunch to all students within a public school, usually through state administration of federal programs such as the National School Lunch Program. Longitudinal studies with assessments prior to program initiation and again after 4 to 6 months demonstrate that higher rates of student participation in school meals are associated with improvements in psychosocial outcomes, including reductions in hyperactivity, anxiety, and depression symptoms (22), and increases in psychosocial functioning scores via the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (23), as well as improvements in a range of academic outcomes such as math scores and school attendance (23)(22). The impacts of universal school meals might also translate to economic benefits, as suggested by a study in Sweden using a difference-in-differences design (24) which found that students exposed to the program earlier and for longer experienced 3% higher lifetime income, with greater effects for youth from poor households. Although school meal programs are widely available, many youth who would benefit from them — particularly those from racial/ethnic minority or low-income backgrounds — do not participate unless these programs are open to all students in the school (i.e., “universal”) (25). Quasi-experimental evidence demonstrates that allowing students to eat in the classroom can also substantially increase school breakfast participation (73.7% participation in the intervention vs. 42.9% in the control group) (26). In 2021, California and Maine passed laws and budgets that fully fund breakfasts and lunches in all K-12 public schools for all students, regardless of family income (27). Massachusetts passed a similar law for schools or districts where the majority of students meet low-income criteria (28), highlighting that these efforts can be adopted at local and state levels. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the US Department of Agriculture extended area eligibility waivers nationwide for summer meal programs, removing the requirement that universal child nutrition programs only be offered in “areas in which poor economic conditions exist.” The Universal School Meals Program Act of 2021 (S.1530) would remove area eligibility requirements year-round, making breakfasts and lunches free for all students in public schools. This bill was introduced to the Senate on May 10th, 2021, and is with the Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry as of this writing. The mental health workforce can play a role in supporting these initiatives by screening for food insecurity and advocating for youth in their communities (29).

One intervention that could make a large improvement in disparities, such as possibly eliminating the racial wealth divide within a generation (30), is universal Child Development Accounts (CDAs). CDAs are savings accounts that are often started at birth, which the individual can access once they turn 18 to use for specific things such as paying for college, buying a home, or starting a business. Compared to children without CDAs, those from low- and moderate-income backgrounds who have CDAs have demonstrated improved socio-emotional outcomes (e.g., self-regulation, compliance, and interaction with others) (31) and mental health outcomes (e.g., self-rated mental health functioning) (32). Youth randomized to receive CDAs were also three times more likely to attend college and four times more likely to graduate (33). Experts have theorized that parental attitudes and behavior may mediate the impact of the savings accounts on youth. There is evidence that CDAs can reduce mothers’ depression symptoms around 3 years after the intervention (34). Although already implemented in 36 states with strong bipartisan support (35), more long-term research is required to confirm CDA impacts on recipients’ mental health once they reach young adulthood.

School-Based Services

Early childhood education and enrichment interventions, such as the Head Start and family-based ParentCorps programs, have been shown to aid the socioemotional development and academic achievement of children from low-income households (36). Such programs are also associated with reductions in child maltreatment (37), which helps mitigate risk of exposure to multiple forms of adversity. Aside from early childhood interventions, school-based mental health services have been shown to be particularly helpful for minoritized youth in urban and low-income neighborhoods (38). Benefits of tiered models include early identification of problems, followed by interventions and/or referrals. However, there is a lack of streamlined triaging of students with more serious behavioral health needs after identification. In response to this, Boston Public Schools launched the Comprehensive Behavioral Health Model (39) in 2012–2013, which operates as a tiered system enhanced by partnerships with community-based behavioral health services. Longitudinal research from the universal screening database over three years finds that students in these schools—a majority of whom are Black and Latinx— demonstrate improvements in socio-emotional, academic, and mental health outcomes within one year, which are sustained at two years (40)(39). In addition, universal interventions delivered in schools can be an effective strategy to combat mental health stigma and increase mental health literacy (41), which remain barriers to treatment seeking.

Community-Based Initiatives

The potential of community-based organizations (CBOs) to play a crucial role in youth wellness cannot be overstated. Frazier and colleagues developed a model of mental health consultation, training, and support of staff at recreational afterschool programs delivered by paraprofessionals (42). An extension to this work resulted in the Fit2Lead program in Miami, FL (43), a park-based program that offers after-school programming (e.g., academic, socioemotional, life skills workshops) at no cost for youth living in disadvantaged neighborhoods. In a longitudinal study comparing zip codes matched by park and sociodemographic characteristics (60% Hispanic, 29% non-Hispanic Black, 33% of residents living in poverty), and after adjusting for covariates the zip codes with Fit2Lead implementation had a mean reduction in the annual rate of youth arrests (ages 12 to 17) compared to zip codes without Fit2Lead implementation (44). In addition, Fit2Lead youth and parents’ mental health remained stable over the course of the school year (45), as opposed to declines commonly observed among adolescents and their parents living in Miami neighborhoods with high levels of community violence. This study demonstrated the promise of Fit2Lead in helping to disrupt a downward trend in mental health trajectories among Latinx and Black families. These findings suggest that task-shifting to paraprofessionals may be an effective way for the benefits of park-based afterschool programs to reach a broader community.

Adults

Social Determinants

Insecure housing and employment are two areas that have garnered attention in addressing mental health outcome disparities among underserved adult populations. For example, Housing First programs, without pre-requisites of demonstrated abstinence or engagement in psychiatric treatment, were shown to lower homelessness by 88% and improve housing stability by 41% compared to Treatment First programs which do require participants to be substance free and in psychiatric treatment (46). There is evidence that Housing First programs can contribute to small reductions in depression, emergency department use, hospitalization, and mortality among people living with HIV (46). More research is needed to examine whether Housing First programs in conjunction with voluntary mental health treatments can effectively reduce morbidity and mortality related to serious mental illness and/or addiction (47). Importantly, many housing policy interventions have worsened racial/ethnic inequities in social determinants of mental health, such as the displacement of Black families during the HOPE VI model (48); thus, Hernandez and Swope (48) highlight the need for health- and equity-specific outcome measures within the design of research evaluating housing policy.

Supported employment is one of few interventions that can reduce an individual’s dependence on the mental health system (49). Individual Placement and Support (IPS), the only evidence-based model of supported employment for people with serious mental illness (50), includes a rapid job search with an IPS specialist, competitive employment, and integration with mental health treatment, among other core principles. A meta-analysis of randomized trials shows that IPS compared the treatment as usual leads to competitive employment within the short-term (51). Compared to those in the control group, people in the IPS condition were three times more likely to work 20 hours or more per week and maintained employment for four times longer. Most studies have focused on vocational outcomes, but IPS has also been associated with sustaining mental health status and lower likelihood of mental health hospitalization (49), including among people with the most severe mental illness and people prone to crises. IPS has expanded to a wide range of populations, including people on the autism spectrum, people with substance use disorders, borderline personality disorder, and more common mental health conditions (50). There are at least 366 IPS programs in the US and 100 outside the US, thanks to a learning community of researchers and programs (50). However, implementation remains far behind demand. It is estimated that within the US, approximately 60% of people with serious mental illness want to work but fewer than 2% have access to IPS (52). Access to IPS would be increased through the creation of a simple funding mechanism and revision of disability policies (52).

In addition to employment, income support programs have demonstrated mental health benefits. One example is the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED), which aims to sustain families with children through $500 monthly payments over a two-year period. Preliminary results from a randomized control trial suggest reductions in maternal depression and anxiety (53). Another example of the mental health effects of expanded income policies is the Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC) for low-income adults, which reduces poverty, increases life expectancy (54) and decreases depressive symptomatology among low-income women (55). Advance monthly payments of the Child Tax Credits has also been linked with a notable fall in household food insufficiency of 26% (56). A variation of the EITC implemented in New York City, Paycheck Plus, demonstrated promising results among low-income workers (57), with sustained improvements over time, including reductions in psychological distress among women and non-custodial parents (58). The uptake of EITC through the American Rescue Plan to citizens and lawfully present children, even if family members did not comply with certain immigration policies, decreased family poverty (59). However, even though income support policies may improve mental health outcomes (60), they may not influence the racial wealth gap without including a feature for wealth accumulation (61).

Community-Based Initiatives

Help-seeking for common mental health conditions like depression or anxiety often occurs within social services or community organizations rather than healthcare settings, particularly within under-resourced communities. Systematic reviews have identified mental health interventions delivered by paraprofessionals in community-based settings that demonstrate positive mental health outcomes (62). Barnett and colleagues (62) found that out of 38 studies included, 27 were RCTs, and in 69% of the RCTs mental health outcomes were significantly better in the intervention than the control group. One community-based model to address social and clinical factors associated with depression is the formation of multi-sector coalitions, which are networks of healthcare and non-healthcare programs. An example of a coalition intervention is the Community Engagement and Planning program to support depression collaborative care, organized through the Community Partners in Care research team in Los Angeles (63). In a randomized trial, Community Engagement and Planning was more effective than the comparison intervention (technical assistance) at increasing depression remission at 4 years (63).

There is also evidence that mental health literacy can be improved through community-wide interventions, such as awareness campaigns, informational materials online, and Education-Entertainment (64). Two examples of mental health literacy campaigns and tools designed for Spanish-speaking Latinx populations that have been rigorously tested and replicated in multiple studies include La CLAve (65) and Secret Feelings (66). In La CLAve, a 35-minute workshop, community health educators facilitate a discussion for community residents and family members based on a narrative film about signs of psychosis and help-seeking. Through a randomized controlled trial (67), and pretest-posttest evaluations (68)(65), the campaign has been shown to increase psychosis literacy of US Latinx community residents. Secret Feelings is a fotonovela (i.e., a booklet telling a dramatic story with photographs and captions) designed to increase depression literacy, reduce stigma, and increase help-seeking behavior among Latinos. In experiments where adults were randomized to the fotonovela or a comparison group (e.g., text pamphlet about depression), the fotonovela group had greater reductions in stigma of antidepressants and mental health care (69) (70), and greater improvements in self-efficacy related to identifying need for treatment (70). The Secret Feelings fotonovela was more likely than the pamphlet to be shared with family or friends after the study (69), and many participants in the La Clave film focus groups also reported discussing the content of the film with their immediate social networks (71), demonstrating the ability of these literacy campaigns to reach throughout communities and promote dialogue about mental illness.

Older Adults

Social Determinants

Green spaces (e.g., parks, gardens) and blue spaces (e.g., oceans, lakes) may help reduce racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in mental health outcomes (72). For example, greater amounts of green space were associated with up to 37% lower odds of depression among older adults living in low-income neighborhoods (compared to 27% and 21% for those in medium- and high-income neighborhoods, respectively) (73). South and colleagues’ (74) cluster randomized trial of vacant lot greening is a good example of an experimental design capable of testing and demonstrating the benefits of green space exposure for adult mental health. It is also a good example of an innovative place-based intervention in low-income urban neighborhoods. Greater attention to how green/blue spaces specifically impact older adult mental health outcomes and disparities is warranted (75, 76). Observed improvements may be due, in part, to the increased opportunities for social interaction and physical activity that green/blue spaces provide (77). Indeed, a cross-sectional study evaluating data from 18 countries found little evidence for a direct association between green/blue spaces and mental health when recreational visits were accounted for in the models. This finding could suggest that one’s use of these spaces may be more important than one’s proximity and/or access to these spaces (78). Differences in the quality of green/blue spaces (e.g., rates of pollution, crime) may also explain the lack of a direct association, since individuals living in disadvantaged neighborhoods may not be able to access, utilize, and therefore benefit from these spaces to the same degree as individuals in more affluent neighborhoods. If true, an assessment of environmental quality and needed improvements would be an important preemptive step to promoting green/blue spaces in certain neighborhoods.

Overall, the promotion of social relationships and interactions is a recurring theme in the literature on improving healthy aging. Research suggests that feelings of isolation and loneliness are associated with a range of negative mental health outcomes (79), which may be exacerbated among older adults from racial and ethnic minority groups who face additional challenges in their pursuit of care (80). Further, some of the identified correlates and predictors of social isolation and loneliness disproportionately impact those from racial and ethnic minority groups and low-income backgrounds (81). While there is a need for development and evidence-based interventions targeting social isolation among older adult populations (82), the fact that many programs (such as those discussed in the next section) and initiatives (e.g., increasing green/blue infrastructure) indirectly promote social connectedness is meaningful.

Community-Based Initiatives

Most quasi-experimental evaluations of programs at adult day service centers, or “senior centers,” have shown statistically significantly greater reductions in depression symptoms and improvements in quality of life among intervention participants compared to controls (83). Although the impact of adult day centers depends on the specific services offered (83), bolstering these settings’ capacity to deliver evidence-based and culturally-specific mental health programming may be effective in improving mental health outcomes. One example is the Positive Minds-Strong Bodies (PM-SB) disability prevention intervention, a manualized and integrated mental and physical health program delivered by paraprofessionals in four languages. PMSB was found to be an acceptable form of treatment to Asian and Latinx older adults (84), and has been implemented in CBOs across three states and Puerto Rico. A second example is EnhanceWellness (85), an evidence-based program currently offered by 13 CBOs across seven states. The personalized program connects older adults with trained coaches who assist the individual in the identification and modification of target behaviors. While the PM-SB and EnhanceWellness programs differ in scale and empirical support, both have demonstrated significant improvements in mental health outcomes (e.g., decreases in depressive and anxiety symptoms, social isolation and loneliness) as well as adequate feasibility across community sites (84–86).

Another promising area for improving older adults’ mental health is the promotion of group-based exercise (87). The EnhanceFitness program, associated with EnhanceWellness, has been nationally disseminated and shown to be effective among adults with low SES and diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds (88). EnhanceFitness is a low-cost group exercise and falls-prevention program that has been implemented across a wide range of CBOs and is associated with myriad psychosocial improvements (89)(90). Stanford University’s Chronic Disease Self-Management Program has demonstrated similar results and showcases yet another example of how exercise programs can be utilized as a medium for mental health promotion among older adults (91–94). Community-based initiatives provide additional opportunities for older adults to remain socially engaged, making the group-based format of the programs particularly important to note. When considering the persistent stigma surrounding mental health, the benefit of these programs could be two-fold, as they promote mental health through modalities that are more acceptable to older adults.

Logistics to Support Change

A shift in focus from the individual to the community that fosters the development of the individual is needed to address root sources of disparities across mental health services and outcomes. Below we indicate some logistics needed to support this shift.

Establishing Collaborations between Academic Institutions, Government, and Community Organizations

Community-level partnerships can facilitate the identification of pressing local issues and place-based program implementation aimed at reducing mental health disparities (95). The quality of academic–community partnerships is critical in the effective implementation of initiatives to mitigate disparities. There are several ways that academic institutions collaborate with state or city government agencies and community-based organizations, but approaches vary in effectiveness. The Engage for Equity research team (96) has identified practices of partnerships that contribute to health, research, and community outcomes, and provided recommendations for partnerships aiming to reach health and social equity outcomes, including engaging in collective reflexive practice to strengthen internal power-sharing. Partnerships are more equitable when partners are treated as co-researchers and when shared decision making is promoted from the inception of the study to the implementation phases (97).

The inclusion of government in these academic-community partnerships can amplify the effect of programs, broaden expertise in both agencies and universities and allow for ongoing sustainability of projects beyond the academic funding cycle. For example, the “academic health department” model (98) brings together local health agencies and academic institutions to expand the resource capacity (e.g., funding, research infrastructure, subject matter experts, and professional staff) needed to implement and sustain large-scale public health initiatives. Government-academic relationships can benefit both parties because government departments need workers and problem-solvers, and schools need training and research opportunities for students (99). Researchers need data, and state agencies need to monitor the impact of their programs, both to comply with government reporting requirements and to maximize the public health payoffs of their investments.

More attention should be paid towards increasing community partners’ involvement in project development, ensuring that projects are responsive to community partners’ needs (100), and providing payment to community members for their advice and time invested. Once partnerships have been established, there are many ways that researchers and providers can support CBOs, including referrals, sharing information and financial contracts, cosponsoring projects, and conducting joint needs assessments. One way to cover the costs of community partners’ involvement in projects is through dedicated and protected funding and resources within existing grant mechanisms, similar to the inclusion of support for data safety and monitoring boards within clinical trials. Another way to build and sustain relationships between institutions and organizations is through supplementary funding approaches, such as community partnership supplements or partnership development grants.

In a study of collaborative networks of healthcare and social service organizations for older adults, researchers found that CBOs are consistently more centrally positioned than any other organization in the network (101). The National Network to Eliminate Disparities in Behavioral Health (NNED), funded by multiple government agencies and foundations, is “a network of community-based organizations focused on the mental health and substance use issues of diverse racial and ethnic communities” (102). To that end, the network supports information sharing, training, and technical assistance, including through the Partner Central forum, a private space for NNED members to search for CBOs in the network to connect. The Administration for Community Living has also dedicated funding for a learning collaborative to replicate CBO networks (103), which has the potential to be an important guidepost for integrating community-based social resources and healthcare delivery. From an administration and management perspective, the contracts that are possible with a larger network of CBOs and health systems will enable the hiring of staff and establishment of reliable payment systems. From a research perspective, the data available with larger networks will enable greater comparison of outcomes across racial and ethnic groups to assess whether these initiatives achieve improvements and equity in access, quality of care, and mental health outcomes.

Lastly, the value of paraprofessionals in the implementation of community mental health care services has gained increasing recognition over the years and has presented a promising medium for increasing the accessibility of community services. There is a need for more training for licensed professional mental health providers to work collaboratively with paraprofessionals (e.g., community health workers) and determine how to train, supervise, integrate, support, and sustain this growing workforce in community settings (104). One challenge often noted in this literature is the high turnover rate (105), which has inspired investigations of incentives given that approximately a third of paraprofessionals were unhappy with the incentives provided (106). Overall, increased job security, support, and advocacy are viewed as important avenues for improving cooperation and retention of paraprofessionals in community mental health services (107).

Limitations

There are several limitations of this report that should be acknowledged. The presentation of studies in tables 1–3 was not exhaustive. Although following certain criteria, there could be selection bias in the studies nominated as there are other studies that might not have been selected due to limited or unclear impacts. It is unknown how some of the recommended programs or interventions would work in different contexts or with more diverse populations, and many of them do not have a cost value analysis to help policymakers decide on their feasibility. More importantly these programs cannot be taken off the shelf without the guided work and supervision of the implementers to ensure fidelity in the content and processes of the original programs.

A Vision of Building Community Mental Health

Building on the HI-5 model, we highlight specific community-level or community-based approaches that could significantly shift the mental health landscape for people of color. Through investing in social determinants and preventive interventions like those discussed in this paper – and better coordination between these programs and primary care screening and referral systems – fewer people will need to make their way to a clinic with staff that may be overwhelmed to deal with the structural and social issues contributing to clients’ mental health needs.

When visualizing what it would look like to live in a community where community mental health is prioritized, we found it helpful to borrow several principles from the traditions of community wealth building (108). The first is labor over capital, acknowledging that continued stable employment for all in the community will benefit community mental health and wellbeing far more than increased capital profits for a select few. The second is local and broad-based ownership from people most affected by the intervention who have capacity and commitment to regularly participate and sustain it, rather than absentee ownership. The third is active democratic ownership, where decision making power is shared among community members with agency, as opposed to the current passive consumer model of mental healthcare. The fourth is the concept of multipliers, or investments that pay local dividends and stay within communities. Fifth, building community mental health should be a multi-stakeholder process, not solely a partnership between the state and business, but consumer-driven, at every step of the process. Sixth, place matters, meaning direct investment in neighborhoods and particularly neighborhoods of color is necessary since ‘trickle-down’ benefits remain illusionary. Seventh, systemic change is the long-term goal — since the current system produces inequalities, we need to build systems based on policies, programs, and practices that have demonstrated evidence of producing equitable mental health outcomes.

Investing in social determinants and community-level resources is not a call to divest from evidence-based mental health treatment and individual-level services, but rather to step back and view the greater potential for reducing disparities through interventions that target upstream sources of inequities and change the context for all. Re-designing equity into our public health systems requires that we acknowledge and correct the fatal flaws of under-funding the US public health system for so long (109). Similarly, an explicit call to invest in communities of color is not a call to divest from white communities. Scientists agree that structural racism is a fundamental cause of disease and root of health inequities (110), with a central mechanism being government policies that disadvantage certain communities through depriving resources and creating unequal access to opportunities. Policies aiming to reduce these inequities will be more effective if we alter policies that perpetuate them (111), and invest in community-level resources and programs that could potentially disrupt disparities significantly for the first time.

Table 2.

Adults: Summary of Included Studies

| Intervention | Description | Study design and study N | Mental health and mental health-related outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Housing First program | Programs that provide housing and health, mental health, and other supportive services for people with disabilities experiencing houselessness, without requiring them to abstain from substance use or be receiving psychiatric treatment | Systematic review (46) of the literature comparing Housing First to care as usual or Treatment First (which requires clients be “housing ready”, i.e., in psychiatric treatment and substance-free prior to permanent housing); 26 studies assessing Housing First programs implemented in high-income nations serving among persons with disabilities experiencing homelessness | Clients with HIV experienced reductions in depression by 13%, emergency department use by 41%, hospitalization by 36%, and mortality by 37%, compared to Treatment First |

| 2. Individual Placement and Support (IPS) for Employment | An evidence-based model of supported employment for people with serious mental illness, substance use disorders, and other disabilities (50). IPS principles include a rapid job search with an IPS specialist, competitive paid employment, and integration with mental health treatment. | A meta-analysis of 30 studies (51), including 25 original randomized controlled trials, two follow-ups of RCTs, and three secondary analyses of previous RCTs | Compared to treatment as usual, the meta-analysis found a small and heterogenous effect of IPS on improvement in clinical mental health symptoms. IPS is associated with improvements in quality of life and global functioning, sustained mental health status, and lower likelihood of experiencing mental health hospitalizations. |

| 3. Earned Income Tax Credits | Tax credits for individuals of low to moderate income who are eligible | In a randomized controlled trial (58) American adults without dependent children were randomly assigned to either the Paycheck Plus program (N = 2,997) or control group (N = 2,971) | Paycheck Plus participants had reductions in psychological distress compared to the control group. Women and noncustodial parents experienced the greatest reductions in distress. |

| Secondary data analyses from the longitudinal study of National Survey of Families and Households; the sample comprised of 13,007 adults at baseline (55) | Decreased depressive symptomatology among those receiving EITC relative to the comparison group | ||

| 4. Community-led interventions for mental health offered by paraprofessionals in under-resourced communities | Mental health programs offered by community health workers | Systematic review of 38 studies (62); 27 were RCTs offered in mostly low- and middle-income countries that included evidence-based or evidence-informed mental health interventions; 31 studies evaluated a model where a CHW is the sole provider of the intervention | In 69% of the 27 RCTs of CHW-involved mental health interventions, mental health outcomes were significantly better than in comparison condition |

| Community coalitions, including the Community Partners in Care model for depression collaborative care (63) | 95 health care and community programs randomized to a coalition intervention (Community Engagement and Planning) or individual program technical assistance; adults with depression, 3-year sample 2010–2014 (n = 1,018) and 4-year sample 2016 (n = 283)(63) | People attending the sites randomized to Community Engagement and Planning on average experienced increased depression remission at 4 years compared to people attending the sites with the comparison condition of receiving technical assistance | |

| 5. Mental health literacy campaigns | “La CLAve” film workshop facilitated by community health educators | Focus groups and pre -post-workshop evaluations (65) among Latinx adults with serious mental illness (n = 57) and family caregivers of people with schizophrenia (n = 38) | Increased psychosis literacy |

| Pre-post workshop questionnaires (68) among community residents aged 15–84 (n = 81) | Increased psychosis literacy | ||

| Randomized controlled trial (67) where (N = 125) adults from Mexico were randomly assigned to view either La Clave or a psychoeducational program regarding caregiving | Psychosis literacy gains were only observed in the La CLAve intervention condition and not in the control group | ||

| “Secret Feelings” Spanish language fotonovela | Randomized controlled trial with 142 immigrant Latina adults at risk for depression (70) | Increased knowledge of depression and help-seeking self-efficacy and reduced stigma as compared to the control group | |

| Randomized controlled trial with 157 Hispanic adults at a community adult school, randomly assigned to read the fotonovela or a text pamphlet about depression, who completed a survey immediately before reading, immediately after, and 1 month later (69) | Both interventions improved depression knowledge and self-efficacy of identifying depression, but the fotonovela group had larger reductions in stigma around antidepressants and mental health care |

Grant Support:

This study was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, Grant R01MD014737-02 (MA, JZD), the National Institute of Drug Abuse, Grant R25DA035692 (JZD), the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Grant K08AA029150 (JZD), and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Grant F31 HD106768 (KD). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the funders.

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

References

- 1.Hansen H, Metzl JM: Structural competency in mental health and medicine: A case-based approach to treating the social determinants of health. Cham, Switzerland, Springer, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook BL, Hou SS, Lee-Tauler SY, et al. : A Review of Mental Health and Mental Health Care Disparities Research: 2011–2014. Med Care Res Rev 2019; 76:683–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trinh N-HT, Cheung C-YJ, Velasquez EE, et al. : Addressing Cultural Mistrust: Strategies for Alliance Building [Internet], inMedlock MM, Shtasel D, Trinh N-HT, et al., editorsRacism and Psychiatry: Contemporary Issues and Interventions. Cham, Springer International Publishing, 2019, pp 157–179.[cited 2022 Jan 14] Available from: 10.1007/978-3-319-90197-8_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mensah M, Ogbu-Nwobodo L, Shim RS: Racism and Mental Health Equity: History Repeating Itself. PS 2021; 72:1091–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartmann WE, Gone JP: American Indian Historical Trauma: Community Perspectives from Two Great Plains Medicine Men. American Journal of Community Psychology 2014; 54:274–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: 2021 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report: Executive Summary [Internet]. 2021Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/nhqrdr/2021qdr-final-es.pdf

- 7.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Medicaid: An Annotated Bibliography [Internet]. 2021[cited 2022 Jan 14] Available from: https://www.macpac.gov/publication/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-medicaid-an-annotated-bibliography/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank RG, Glied SA: Better but not well: Mental health policy in the United States since 1950 [Internet]. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006[cited 2022 Jan 14] Available from: http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=84898353751&partnerID=8YFLogxK [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drake R, Latimer E: Lessons learned in developing community mental health care in North America. World Psychiatry 2012; 11:47–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huey LY, Cole RF, Ford JD: Chapter 58.1 Public and community psychiatry, inSadock and Kaplan’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Lippincott Wolters Kluwer, 2017, pp 4287-. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J: The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med 2011; 104:510–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck AJ, Manderscheid RW, Buerhaus P: The Future of the Behavioral Health Workforce: Optimism and Opportunity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2018; 54:S187–S189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heberlein M, Holgash K: Physician Acceptance Of New Medicaid Patients: What Matters And What Doesn’t | Health Affairs Forefront [Internet]. Health Affairs Blog 2019; [cited 2022 Jan 14] Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20190401.678690/full/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission: June 2021 Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP [Internet]. 2021Available from: macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/June-2021-Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf

- 15.Coye M: To Address Mental Health Care Inequities, Look Beyond Community-Based Programs [Internet]. Health Affairs Blog 2019; Available from: 10.1377/hblog20210920.571507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alegría M, Pescosolido BA, Williams S, et al. : Culture, Race/Ethnicity and Disparities: Fleshing Out the Socio-Cultural Framework for Health Services Disparities [Internet], inPescosolido BA, Martin JK, McLeod JD, et al., editorsHandbook of the Sociology of Health, Illness, and Healing: A Blueprint for the 21st Century. New York, NY, Springer, 2011, pp 363–382.[cited 2021 Sep 27] Available from: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7261-3_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kazdin AE, Rabbitt SM: Novel Models for Delivering Mental Health Services and Reducing the Burdens of Mental Illness. Clinical Psychological Science 2013; 1:170–191 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Health Impact in Five Years [Internet]. Office of the Associate Director for Policy and Strategy, 2018Available from: www.cdc.gov/hi5 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deaton A, Cartwright N: Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials. Social Science & Medicine 2018; 210:2–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart-Brown S, Anthony R, Wilson L, et al. : Should randomised controlled trials be the “gold standard” for research on preventive interventions for children? Journal of Children’s Services 2011; 6:228–235 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alegría M, O’Malley IS: Opening the black box: Overcoming obstacles to studying causal mechanisms in research on reducing inequality [Internet] William T. Grant Foundation, 2022Available from: http://wtgrantfoundation.org/digest/opening-the-black-box-overcoming-obstacles-to-studying-causal-mechanisms-in-research-on-reducing-inequality [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy JM: The Relationship of School Breakfast to Psychosocial and Academic FunctioningCross-sectional and Longitudinal Observations in an Inner-city School Sample. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998; 152:899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleinman RE, Hall S, Green H, et al. : Diet, Breakfast, and Academic Performance in Children. Ann Nutr Metab 2002; 46:24–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alex-Petersen J, Lundborg P, Rooth D-O: Long-Term Effects of Childhood Nutrition: Evidence from a School Lunch Reform 2017; 57 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basch CE: Breakfast and the Achievement Gap Among Urban Minority Youth. Journal of School Health 2011; 81:635–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anzman-Frasca S, Djang HC, Halmo MM, et al. : Estimating Impacts of a Breakfast in the Classroom Program on School Outcomes. JAMA Pediatr 2015; 169:71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.School Nutrition Association: California and Maine Become First States to Officially Provide Universal School Meals at No Charge [Internet]. School Nutrition Association; 2021; [cited 2022 Jan 14] Available from: https://schoolnutrition.org/news-publications/news/2021/california-and-maine-become-first-states-to-officially-provide-universal-school-meals-at-no-charge/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.House Committee on Ways and Means: An Act Promoting Student Nutrition [Internet]. 2021[cited 2022 Jan 14] Available from: https://malegislature.gov/Bills/192/H3999

- 29.Shim RS, Compton MT: The Social Determinants of Mental Health: Psychiatrists’ Roles in Addressing Discrimination and Food Insecurity. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ) 2020; 18:25–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Annie E Casey Foundation: Investing in tomorrow: helping families build savings and assets [Internet]. www.aecf.org, 2016Available from: https://aecfcraftstr01.blob.core.windows.net/aecfcraftblob02/m/resourcedoc/aecf-investingintomorrow-2016.pdf

- 31.Beverly S, Clancy M, Sherraden M: Universal Accounts at Birth: Results From SEED for Oklahoma Kids [Internet]. Center for Social Development Research; 2016; Available from: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/csd_research/326 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ssewamala FM, Han C-K, Neilands TB: Asset Ownership and Health and Mental Health Functioning Among AIDS-Orphaned Adolescents: Findings From a Randomized Clinical Trial in Rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med 2009; 69:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elliott W, Song H, Nam I: Small-dollar children’s savings accounts and children’s college outcomes by income level. Children and Youth Services Review 2013; 35:560–571 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang J, Sherraden M, Purnell JQ: Impacts of Child Development Accounts on maternal depressive symptoms: Evidence from a randomized statewide policy experiment. Social Science & Medicine 2014; 112:30–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cisneros J, Clancy M: The Case for a Nationwide Child Development Account Policy: A policy brief developed by CDA experts and researchers [Internet]. Washinton University, Center for Social Development, 2021Available from: 10.7936/axxv-4t52 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hahn RA, Barnett WS, Knopf JA, et al. : Early Childhood Education to Promote Health Equity: A Community Guide Systematic Review. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 2016; 22:E1–E8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green BL, Ayoub C, Bartlett JD, et al. : The effect of Early Head Start on child welfare system involvement: A first look at longitudinal child maltreatment outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review 2014; 42:127–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: School-Based Strategies for Addressing the Mental Health and Well-Being of Youth in the Wake of COVID-19 [Internet]. Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 2021[cited 2021 Sep 28] Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/26262/school-based-strategies-for-addressing-the-mental-health-and-well-being-of-youth-in-the-wake-of-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearrow MM, Amador A, Dennery S: Boston Public Schools’ Comprehensive Behavioral Health Model. Communique 2016; 45:1–20 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Battal J, Pearrow MM, Kaye AJ: Implementing a comprehensive behavioral health model for social, emotional, and behavioral development in an urban district: An applied study. Psychology in the Schools 2020; 57:1475–1491 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salerno JP: Effectiveness of Universal School-Based Mental Health Awareness Programs Among Youth in the United States: A Systematic Review. J Sch Health 2016; 86:922–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frazier SL, Mehta TG, Atkins MS, et al. : Not just a walk in the park: efficacy to effectiveness for after school programs in communities of concentrated urban poverty. Adm Policy Ment Health 2013; 40:406–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frazier SL, Chou T, Ouellette RR, et al. : Workforce Support for Urban After-School Programs: Turning Obstacles into Opportunities. Am J Community Psychol 2019; 63:430–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D’Agostino EM, Frazier SL, Hansen E, et al. : Two-Year Changes in Neighborhood Juvenile Arrests After Implementation of a Park-Based Afterschool Mental Health Promotion Program in Miami–Dade County, Florida, 2015–2017. Am J Public Health 2019; 109:S214–S220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodman AC, Ouellette RR, D’Agostino EM, et al. : Promoting healthy trajectories for urban middle school youth through county-funded, parks-based after-school programming. J Community Psychol 2021; 49:2795–2817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peng Y, Hahn RA, Finnie RKC, et al. : Permanent Supportive Housing With Housing First to Reduce Homelessness and Promote Health Among Homeless Populations With Disability: A Community Guide Systematic Review. J Public Health Manag Pract 2020; 26:404–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elde S: Housing First Is Not the Key to End Homelessness [Internet]. Manhattan Institute; 2020; [cited 2022 Jan 17] Available from: https://www.manhattan-institute.org/housing-first-effectiveness [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hernández D, Swope CB: Housing as a Platform for Health and Equity: Evidence and Future Directions. Am J Public Health 2019; 109:1363–1366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drake RE, Wallach MA: Employment is a critical mental health intervention. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2020; 29:e178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR: An update on Individual Placement and Support. World Psychiatry 2020; 19:390–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frederick D, VanderWeele T: Supported employment: Meta-analysis and review of randomized controlled trials of individual placement and support. PLOS ONE 2019; 14:e0212208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drake RE, Bond GR, Goldman HH, et al. : Individual Placement And Support Services Boost Employment For People With Serious Mental Illnesses, But Funding Is Lacking. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016; 35:1098–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.West S, Baker A, Samra S, et al. : SEED: Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration: preliminary analysis: SEED’s first year. 2021[cited 2022 Jan 5] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. : The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. JAMA 2016; 315:1750–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boyd-Swan C, Herbst C, Ifcher J, et al. : The earned income tax credit, mental health, and happiness. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 2016; 126:18–38 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shafer PR, Gutiérrez KM, Ettinger de Cuba S, et al. : Association of the Implementation of Child Tax Credit Advance Payments With Food Insufficiency in US Households. JAMA Network Open 2022; 5:e2143296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Courtin E, Aloisi K, Miller C, et al. : The Health Effects Of Expanding The Earned Income Tax Credit: Results From New York City. Health Affairs 2020; 39:1149–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Courtin E, Allen HL, Katz LF, et al. : Effect of Expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit to Americans without Dependent Children on Psychological Distress (Paycheck Plus): a Randomized Controlled Trial [Internet]. American Journal of Epidemiology 2021; [cited 2021 Sep 27] Available from: 10.1093/aje/kwab164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Acevedo-Garcia D, Joshi PK, Ruskin E, et al. : Restoring An Inclusionary Safety Net For Children In Immigrant Families: A Review Of Three Social Policies. Health Affairs 2021; 40:1099–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilson N, McDaid S: The mental health effects of a Universal Basic Income: A synthesis of the evidence from previous pilots. Social Science & Medicine 2021; 287:114374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oliver ML, Shapiro TM: Disrupting the Racial Wealth Gap. Contexts 2019; 18:16–21 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barnett ML, Gonzalez A, Miranda J, et al. : Mobilizing community health workers to address mental health disparities for underserved populations: A systematic review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 2018; 45:195–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arevian AC, Jones F, Tang L, et al. : Depression Remission From Community Coalitions Versus Individual Program Support for Services: Findings From Community Partners in Care, Los Angeles, California, 2010–2016. Am J Public Health 2019; 109:S205–S213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jorm AF: Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. American Psychologist 2012; 67:231–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.López SR, Kopelowicz A, Solano S, et al. : La CLAve to Increase Psychosis Literacy of Spanish-Speaking Community Residents and Family Caregivers. J Consult Clin Psychol 2009; 77:763–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cabassa LJ, Contreras S, Aragón R, et al. : Focus Group Evaluation of “Secret Feelings”: A Depression Fotonovela for Latinos With Limited English Proficiency. Health Promot Pract 2011; 12:840–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Casas RN, Gonzales E, Aldana-Aragón E, et al. : Toward the Early Recognition of Psychosis Among Spanish-Speaking Adults on both Sides of the US-Mexico Border. Psychol Serv 2014; 11:460–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Calderon V, Cain R, Torres E, et al. : Evaluating the message of an ongoing communication campaign to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis in a Latinx community in the United States [Internet]. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 2021; Online early view[cited 2022 Jan 5] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/eip.13140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Unger JB, Cabassa LJ, Molina GB, et al. : Evaluation of a Fotonovela to Increase Depression Knowledge and Reduce Stigma Among Hispanic Adults. J Immigr Minor Health 2013; 15:398–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hernandez MY, Organista KC: Entertainment-education? A fotonovela? A new strategy to improve depression literacy and help-seeking behaviors in at-risk immigrant Latinas. Am J Community Psychol 2013; 52:224–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hernandez MY, Mejia Y, Mayer D, et al. : Using a Narrative Film to Increase Knowledge and Interpersonal Communication About Psychosis Among Latinos. Journal of Health Communication 2016; 21:1236–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brown SC, Perrino T, Lombard J, et al. : Health disparities in the relationship of neighborhood greenness to mental health outcomes in 249,405 US Medicare beneficiaries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018; 15:430–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lu Y, Chen L, Liu X, et al. : Green spaces mitigate racial disparity of health: A higher ratio of green spaces indicates a lower racial disparity in SARS-CoV-2 infection rates in the USA. Environment International 2021; 152:106465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.South EC, Hohl BC, Kondo MC, et al. : Effect of Greening Vacant Land on Mental Health of Community-Dwelling Adults: A Cluster Randomized Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2018; 1:e180298–e180298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Keijzer C, Bauwelinck M, Dadvand P: Long-term exposure to residential greenspace and healthy ageing: A systematic review. Current Environmental Health Reports 2020; 7:65–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saitta M, Devan H, Boland P, et al. : Park-based physical activity interventions for persons with disabilities: A mixed-methods systematic review. Disability and Health Journal 2019; 12:11–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gascon M, Zijlema W, Vert C, et al. : Outdoor blue spaces, human health and well-being: A systematic review of quantitative studies. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 2017; 220:1207–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.White MP, Elliott LR, Grellier J, et al. : Associations between green/blue spaces and mental health across 18 countries. Sci Rep 2021; 11:8903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine: Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system [Internet]. Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 2020Available from: 10.17226/25663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Falgas-Bague I, Wang Y, Banerjee S, et al. : Predictors of Adherence to Treatment in Behavioral Health Therapy for Latino Immigrants: The Importance of Trust [Internet]. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2019; 10[cited 2022 Jan 14] Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cohen-Mansfield J, Hazan H, Lerman Y, et al. : Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults: A review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. International Psychogeriatrics 2016; 28:557–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Blazer D: Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults—A Mental Health/Public Health Challenge. JAMA Psychiatry 2020; 77:990–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fields NL, Anderson KA, Dabelko-Schoeny H: The effectiveness of adult day services for older adults: A review of the literature from 2000 to 2011. Journal of Applied Gerontology 2014; 33:130–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Alegría M, Frontera W, Cruz-Gonzalez M, et al. : Effectiveness of a disability preventive intervention for minority and immigrant elders: the positive minds-strong bodies randomized clinical trial. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2019; 27:1299–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Phelan EA, Williams B, Snyder SJ, et al. : A five state dissemination of a community-based disability prevention program for older adults. Clin Interv Aging 2006; 1:267–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hughes SL, Seymour RB, Campbell RT, et al. : Comparison of Two Health-Promotion Programs for Older Workers. Am J Public Health 2011; 101:883–890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Catalan-Matamoros D, Gomez-Conesa A, Stubbs B, et al. : Exercise improves depressive symptoms in older adults: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatry Research 2016; 244:202–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Petrescu-Prahova MG, Eagen TJ, Fishleder SL, et al. : Enhance®Fitness Dissemination and Implementation,: 2010–2015: A Scoping Review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2017; 52:S295–S299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wallace JI, Buchner DM, Grothaus L, et al. : Implementation and Effectiveness of a Community-Based Health Promotion Program for Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 1998; 53A:M301–M306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mays AM, Kim S, Rosales K, et al. : The Leveraging Exercise to Age in Place (LEAP) Study: Engaging Older Adults in Community-Based Exercise Classes to Impact Loneliness and Social Isolation. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2021; 29:777–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Smith ML, Ory MG, Ahn S, et al. : National Dissemination of Chronic Disease Self-Management Education Programs: An Incremental Examination of Delivery Characteristics [Internet]. Frontiers in Public Health 2015; 2[cited 2022 Jan 14] Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Smith ML, Cho J, Salazar CJ, et al. : Changes in Quality of Life Indicators among Chronic Disease Self-Management Program Participants: an Examination by Race and Ethnicity. Ethnicity & Disease 2013; 23:182–188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brady TJ, Murphy L, O’Colmain BJ, et al. : A Meta-Analysis of Health Status, Health Behaviors, and Health Care Utilization Outcomes of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program. Prev Chronic Dis 2013; 10:E07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, González VM: Hispanic chronic disease self-management: a randomized community-based outcome trial. Nurs Res 2003; 52:361–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Oetzel JG, Wallerstein N, Duran B, et al. : Impact of Participatory Health Research: A Test of the Community-Based Participatory Research Conceptual Model. BioMed Research International 2018; 2018:e7281405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wallerstein N, Oetzel JG, Sanchez-Youngman S, et al. : Engage for Equity: A Long-Term Study of Community-Based Participatory Research and Community-Engaged Research Practices and Outcomes. Health Educ Behav 2020; 47:380–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Zhen-Duan J, et al. : Latinos Unidos por la Salud: The Process of Developing an Immigrant Community Research Team. Collaborations: A Journal of Community-Based Research and Practice 2017; 1:2 [Google Scholar]

- 98.Keck CW: Lessons learned from an academic health department. J Public Health Manag Pract 2000; 6:47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schieve LA, Handler A, Gordon AK, et al. : Public health practice linkages between schools of public health and state health agencies: results from a three-year survey. J Public Health Manag Pract 1997; 3:29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pinto RM, Witte SS, Wall MM, et al. : Recruiting and retaining service agencies and public health providers in longitudinal studies: Implications for community-engaged implementation research. Methodological Innovations 2018; 11:2059799118770996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Brewster AL, Yuan CT, Tan AX, et al. : Collaboration in Health Care and Social Service Networks for Older Adults: Association With Health Care Utilization Measures. Medical Care 2019; 57:327–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.National Network to Eliminat Disparities in Behavioral Health: National Network to Eliminate Disparities in Behavioral Health (NNED) [Internet] 2022; Available from: https://nned.net/about [Google Scholar]

- 103.Robertson L, Chernof B: Addressing Social Determinants: Scaling Up Partnerships with Community-Based Organization Networks. Health Affairs Blog 2020; [Google Scholar]