Abstract

This article provides an updated review of the pharmacological profile and available efficacy and tolerability/safety data for vilazodone, one of the most recent antidepressant drugs to be approved in the USA for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults. The efficacy of vilazodone for MDD in adults is supported by four positive short-term (8–10 weeks), randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Beyond these pivotal trials, we review updated research findings pertaining to the clinical effects of vilazodone for MDD including the results of switch studies, small comparative efficacy trials, key pooled and secondary data analyses focused on important depressive subtypes (anxious depression) and predictors of treatment outcome, and safety studies including direct studies of sexual side-effects. Despite these additional research efforts and use for over a decade, important gaps in the clinical evidence base remain with vilazodone. Hypothesized differences in efficacy and adverse effects between other antidepressants and vilazodone based on its multimodal mechanism of action (combining serotonin reuptake inhibition with serotonin 5-HT1A partial agonist effects) have not been comprehensively demonstrated in clinical studies and its effectiveness as a continuation- or maintenance-phase therapeutic is not yet established. Questions remain regarding its reproductive and lactational safety profiles and its efficacy as a potential next-step therapeutic for patients with MDD who do not respond to first-line antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Suggestions for clinical use of vilazodone and discussion of its place among the broad range of pharmacotherapies for adults with MDD are provided.

Keywords: vilazodone, major depressive disorder, depression, efficacy, safety, comparative effectiveness

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) affects over 350 million people worldwide and is a leading cause of disability and economic burden.1–3 Fortunately, the symptoms of depression can be controlled with appropriate pharmacotherapy and psychosocial treatments.4 Initial and subsequent choices of antidepressants are based on a comprehensive consideration of a variety of factors including symptom profile, patient choice, outcomes of previous trials, adverse effect profiles, drug interactions, treatment cost, product availability, and differential effectiveness, although there is little evidence of clinical superiority of one antidepressant over the others.5,6 However, the clinical response to antidepressants is highly variable and, for far too many patients with MDD, symptomatic improvement and restoration of normal functioning is incomplete or absent after multiple therapeutic trials.7–9 Furthermore, rates of non-adherence to antidepressants range from 50% to 75%, usually owing to adverse effects.10 These observations highlight the importance of having a broad range of antidepressants for treating MDD in adults.

Vilazodone is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist that received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2011 for the acute treatment of MDD in adults.11 Based in part on its combined serotonin reuptake inhibition and 5-HT1A partial agonist effects, there has been interest in the potential advantages of vilazodone over other antidepressants, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), with respect to efficacy (faster onset, broader symptomatic effectiveness) and tolerability (lower risk of sexual side effects).12,13 If true, such advantages could potentially justify vilazodone’s higher expense as a relatively newer entrant into the competitive antidepressant market, compared to other antidepressants for which generic formulations are available.

With over a decade of clinical use and the availability of results from additional studies beyond the pivotal trials, an updated review of published clinical evidence supporting the use of vilazodone for the treatment of adults with MDD is needed. This non-systematic overview summarizes the pharmacological profile of vilazodone and examines more recent data from clinical trials and other key studies of vilazodone for MDD including the results of switch studies, small comparative efficacy trials, key pooled and secondary data analyses focused on important depressive subtypes (such as anxious depression) and predictors of treatment outcome, and safety studies including direct studies of sexual side-effects. Its current role in the context of other available pharmacotherapies for MDD is also discussed.

Data Sources

We conducted a MEDLINE database literature search in September 2021 using the key search term, vilazodone, combined with additional terms (pharmacological profile, pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, adverse effects/side effects/safety, depression, major depression, major depressive disorder) and filters for identifying specific article types (systematic review, randomized controlled trial, meta-analysis). Using this approach, we identified relevant systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized trials, and important non-randomized studies. The reference sections of retrieved papers were reviewed to locate additional reports that were not identified in the initial MEDLINE search. For inclusion, all reports of the clinical effects of vilazodone had to specifically address the efficacy, effectiveness, and/or safety of vilazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorder.

Pharmacological Profile

Chemistry

The molecular weight and molecular formula for vilazodone are C26H27N5O2 and 441.5 g/mol, respectively.14 Vilazodone is classified under the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) name, 5-(4-(4-(5-Cyano-1H-indol-3-yl)butyl)piperazin-1-yl)benzofuran-2-carboxamide. The chemical and pharmacological properties of vilazodone are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Summary of Vilazodone

| Approved Indication(s): | Major Depressive Disorder in Adults |

|---|---|

| Main pharmacological effect(s): | Inhibition of serotonin reuptake and partial agonist effects at serotonin 5HT1A receptors |

| Formulation(s): | Solid oral tablets [10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg] |

| Starting dose: | 10 mg daily, with food |

| Dose-titration: | Increase to 20 mg daily after 7 days; further adjust dose to 40 mg daily as necessary |

| Effective dose range: | 20–40 mg daily |

| Maximum dose: | 40 mg daily |

| Key pharmacokinetic parameters: | Absorption is affected by food. Extensive hepatic metabolism, mainly by CYP3A4 Elimination half-life = 25 hours |

| Potential pharmacogenetic factors: | Unknown; dose adjustments may be necessary for known pharmacogenetic poor metabolizers or ultra-rapid metabolizers at CYP3A4 |

| Interactions and dosing effects: | Maximum dose is 20 mg daily when given with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors; dose may need to be increased when given with strong CYP3A4 inducers |

Pharmacodynamics

Classification

As noted earlier, vilazodone is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and a 5-HT-1A receptor partial agonist.11,15 Based on these combined effects, vilazodone has been classified using various terms. For example, vilazodone is included among “other antidepressants” in the World Health Organization’s Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system, using ATC code N06AX24. Others have classified vilazodone as being a “multimodal” antidepressant with pharmacological activity at more than one molecular target believed to be related to antidepressive effects.16 Vilazodone’s mechanism-based classification is that of a serotonin partial agonist-reuptake inhibitor (SPARI).11

Serotonin Reuptake Inhibition

Vilazodone is a potent serotonin reuptake pump inhibitor (Ki 0.20 nM), a classical pharmacological mechanism that has been the template for numerous predecessor antidepressants.17,18 Serotonin reuptake inhibition, however, fails to distinguish vilazodone from most other commonly used antidepressants. Moreover, it alone cannot explain the lag time between treatment initiation and antidepressant effects.

5-HT1A Partial Agonism

Vilazodone is also a potent 5-HT1A partial agonist (Ki 0.30 nM),19 with is thought to be involved in its antidepressive effects, possibly in a synergistic manner with serotonin reuptake blockade. Rapid increases in the synaptic availability of serotonin following reuptake inhibition lead to the activation of 5-HT1A receptors in midbrain raphe, which inhibits the release of serotonin in nerve terminals.20 Over days to weeks, somatodendritic 5-HT1A autoreceptors down-regulate, causing an increase in serotonergic neurotransmission in downstream brain regions that are important for affective and neurovegetative functioning.21 Because the process of 5-HT1A autoreceptor down-regulation is not immediate, it is a leading hypothesis as to why it takes several weeks for SSRIs and similar antidepressants to work.17

As noted earlier, the relationships between 5HT1A activity and depressive and anxiety symptoms and sexual dysfunction may have implications for the efficacy and adverse effect profiles of vilazodone. Although the results of monotherapy trials of 5-HT1A partial agonists for depression have yielded disappointing results, there is mixed evidence of more rapid and enhanced antidepressant effects when 5-HT1A partial agonists are added to SSRIs.22–24 Like SSRIs, azapirone 5-HT1A partial agonists have been shown, as a group, to be superior to placebo for treating generalized anxiety disorder,25 suggesting that pharmacological activity at 5-HT1A in combination with serotonin reuptake blockade may be especially beneficial for treating co-occurring depressive and anxiety symptoms and MDD with comorbid generalized anxiety.

Selective 5-HT1A agonists and azapirone 5-HT1A partial agonists have also been shown to have pro-sexual effects in animal models and in humans,26–28 suggesting that 5-HT1A activity may limit the risk of sexual side effects associated with serotonin reuptake blockade. The extent to which these putative advantages have been satisfactorily demonstrated in clinical studies of vilazodone is discussed below.

Other Pharmacological Targets

Vilazodone does not appear to have meaningful interactions with other pharmacological targets implicated in antidepressive responses or adverse effects. Vilazodone has non-significant binding activity at norepinephrine and dopamine transporters and at serotonin receptors other than 5-HT1A.18,29 Vilazodone displays no significant binding activity at adrenergic, histaminergic, and cholinergic receptors.30

Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Elimination

Vilazodone is readily absorbed after oral ingestion, with peak plasma concentrations achieved within 3–5 hours.30 The Cmax of vilazodone is increased by up to 160% with a high fat meal and by up to 85% with a light meal compared with the fasting state.31 As such, vilazodone should be taken with food. Vilazodone is highly protein-bound (96% to 99%), has a large volume of distribution, and has a mean elimination half-life of about 25 hours.11,32 Vilazodone undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism, mainly by oxidation via the cytochrome P450 3A4 isoenzyme, with minor contributions from CYP2C19 and CYP2D6.32 Vilazodone has no clinically relevant metabolites.33 The maximum dose of vilazodone must be reduced by 50% (to 20 mg/day) when taken with potent CYP3A4 inhibitors.

Modifying Factors

Renal Insufficiency

According to the package label, no dose adjustment is required for vilazodone in patients with mild or moderate renal disease.31 In a Phase I study, a single 20 mg dose of vilazodone was given to 16 nondepressed subjects with mild renal impairment (eGFR >50–80 mL/min) or moderate renal impairment (eGFR ≥30–50) who were matched on age, sex, and BMI to control subjects with normal renal functioning (eGFR >80).34 There were no significant differences in vilazodone exposure between individuals with renal impairment and those with normal renal functioning. Potential changes to the pharmacokinetics of vilazodone in patients requiring hemodialysis have not been investigated, although vilazodone not expected to be dialyzable due to its high volume of distribution.

Hepatic Insufficiency

The pharmacokinetic disposition of vilazodone does not appear to be significantly altered in patients with mild-to-moderate hepatic insufficiency,34 although caution is still advised. The dose of vilazodone should be reduced in patients with severe hepatic impairment. To date, no cases of acute liver injury have been reported with vilazodone.35 However, this may be due to its relatively short duration of clinical availability. Therefore, the hepatic safety of vilazodone compared to other antidepressants is unknown.

Elderly Patients

The disposition of a single 20 mg oral dose of vilazodone appears to be similar between individuals aged >65 years and those aged 24 to 55 years.31 However, low starting doses, slow titration, and vigilance for tolerability problems are recommended when using vilazodone in elderly patients. We also recommend monitoring for hyponatremia when prescribing vilazodone to elderly patients based on the association between SSRIs/SNRIs and incident hyponatremia, which appears to occur at higher rates in the elderly and in patients with multiple medical comorbidities, multiple medications, and poor oral intake.36 To our knowledge, there is only one published case report of vilazodone-associated hyponatremia.37

Drug Interactions

CYP450-Based Interactions

The dose of vilazodone will need to be adjusted when taken with CYP3A4 inhibitors or inducers. The dose of vilazodone should not exceed 20 mg/day when taken with grapefruit juice or medications that are strong CYP3A4 inhibitors. Higher doses of vilazodone may be needed if it is administered with CYP3A4 inducers. According to the package insert, vilazodone has been shown to moderately inhibit CYP2D6 and 2C19 in vitro.31 Therefore, caution may be warranted when vilazodone is coadministered with certain CYP2D6 and 2C19 substrates, including drugs such as clopidogrel or tamoxifen that are converted to their active form by these isoenzymes.

P-Glycoprotein-Based Interactions

Vilazodone is a P-glycoprotein (PGP) inhibitor; however, the clinical significance of PGP inhibition by vilazodone is unclear.38 Still, we recommend caution when administering vilazodone with PGP substrates with narrow therapeutic indices, such as digoxin or sirolimus.

Other Drug Interactions

Vilazodone is contraindicated in patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and drugs with MAOI-like activity (eg, linezolid, methylene blue, etc.), and should not be taken within 14 days of discontinuing an MAOI due to the risk of serotonin toxicity. Like other serotonergic antidepressants, vilazodone may be associated with an increased risk of minor bleeding events when taken with anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.39 Since vilazodone is 96–99% protein bound, there may be some risk of it displacing other highly-protein-bound drugs with narrow therapeutic windows, such as warfarin and digoxin.

Clinical Efficacy

Individual Studies for Acute Treatment of Major Depression

Phase III and IV Randomized Trials

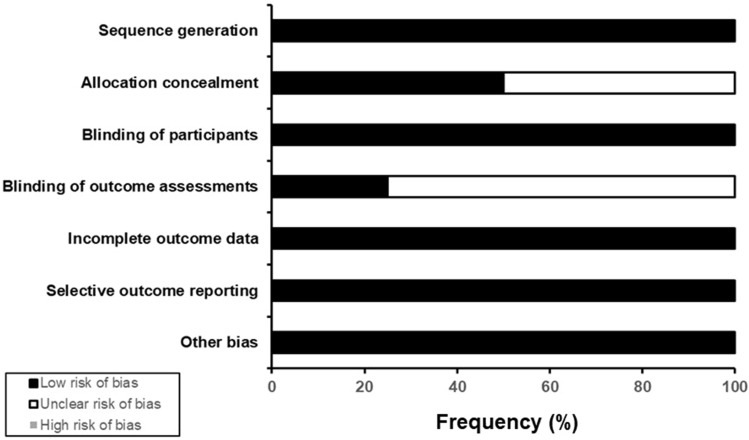

The efficacy of vilazodone for MDD is supported by four positive randomized trials.40–43 Table 2 summarizes the design features of these studies, all of which were multi-center, fixed-dose, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trials of 8–10-week duration. Three of the four studies compared the antidepressive effects of vilazodone 40 mg/day vs placebo, while the remaining study compared two fixed doses of vilazodone (40 and 20 mg/day) and citalopram 40 mg/day with placebo. All four studies were assessed as having low risk of bias (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Summary of Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Design Features of Short-Term Randomized, Placebo (PLC)-Controlled Trials of Vilazodone for Major Depression in Adults

| Reference/ Registration | Setting | Age Range | RCT Design | Depression Severity Threshold for Inclusion | Duration | Total Enrollment | Selected Characteristics by Treatment Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | % Women | Age of MDD Onseta | Duration of Current MDD Episodeb | |||||||

| Croft et al 201440 (NCT01473394) | 14 US centers | 18–70 years | Double-blind, PLC-controlled, parallel-group, fixed-dose, phase IV study | MADRS ≥ 26 | 8 weeks | n = 518 | Vilazodone 40 mg/day | 51.4 | 30.1 years | 7.1 months |

| PLC | 56.1 | 30.7 years | 6.4 months | |||||||

| Khan et al 201141 (NCT00683592) | 15 US centers | 18–70 years | Double-blind, PLC-controlled, parallel-group, fixed-dose, phase III study | HAMD-17 ≥ 22 and HAMD-17 item 1 (depressed mood) score ≥ 2 at screening and baseline | 8 weeks | n = 481 | Vilazodone 40 mg/day | 59.1 | 32.0 years | 52.8% >6 months |

| PLC | 53.2 | 33.2 years | 48.5% >6 months | |||||||

| Matthews et al 201542 (NCT01473381) | 54 US centers | 18–70 years | Double-blind, PLC- and active-controlled, parallel-group, fixed-dose, phase IV study | MADRS ≥ 26 | 10 weeks | n = 1162 | Vilazodone 40 mg/day | 57.1 | 30.4 years | 6.3 months |

| Vilazodone 20 mg/day | 57.6 | 30.9 years | 6.0 months | |||||||

| Citalopram 40 mg/day | 58.5 | 32.3 years | 6.6 months | |||||||

| PLC | 56.2 | 31.1 years | 6.4 months | |||||||

| Rickels et al 200943 (NCT00285376) | 10 US centers | 18–65 years | Double-blind, PLC-controlled, parallel-group, fixed-dose, phase III study | HAMD-17 ≥ 22 and HAMD-17 item 1 (depressed mood) score ≥ 2 at screening and baseline | 8 weeks | n = 410 | Vilazodone 40 mg/day | 62.0 | 33.4 years | 47.8% >6 months |

| PLC | 63.7 | 31.9 years | 46.1% >6 months | |||||||

Notes: aAge of onset of MDD is presented as a mean value (in years) unless otherwise indicated. bDuration of the current episode of MDD is presented as a mean value (in months) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: HAMD-17, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, 17-item version; MADRS, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; PLC, placebo; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Figure 1.

Estimated risk of bias of short-term randomized trials of vilazodone for major depressive disorder in adults. This figure provides a summary of an assessment of overall risk of bias across four published studies of vilazodone for treating major depressive disorder in adults, using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment tool.

Across studies, vilazodone resulted in significantly greater improvements in depressive symptoms than placebo, as measured using the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)44 (Table 3). Rates of treatment response were also significantly higher with vilazodone than placebo in all but one study.42 Response rates with vilazodone varied according to the endpoint definition and were higher with vilazodone (40% to 65%) in studies that defined response as a ≥50% reduction in MADRs total scores from baseline and lower (27% to 34%) in studies that focused on sustained response (MADRS total score ≤12 for two consecutive study visits). There were no significant differences in remission rates between vilazodone and placebo (27% vs 20%) in the only study that included remission as a secondary endpoint.41

Table 3.

Summary of Main Efficacy Results of Short-Term Randomized, Placebo (PLC)-Controlled Trials of Vilazodone for Major Depression in Adults

| Reference/ Registration | Treatment Group (n) | Main Results | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completion Rates | Depressive Symptom Change from Baseline, LS-Mean (SE) | Response | Sustained Response | Remission | |||||

| Response Rate | NNT vs PLC | Sustained Response Ratea, b | NNT vs PLC | Remission Rate | NNT vs PLC | ||||

| Croft et al 201440 (NCT01473394) | Vilazodone 40 mg/day (n=260) | 83.1% | −16.1 (0.6)**** | 57.7%*** | 5 | 27.3%** | 10 | Not reported | N/A |

| PLC (n=258) | 82.0% | −11.0 (0.7) | 36.2% | Referent | 17.1%d | Referent | Not reported | N/A | |

| Khan et al 201141 (NCT00683592) | Vilazodone 40 mg/day (n=240) | 80.4% | −13.3 (0.9)** | 43.7%**b | 14 | Not reported | N/A | 27.3%c | 22 |

| PLC (n=241) | 80.9% | −10.8 (0.9) | 30.3% | Referent | Not reported | N/A | 20.3% | Referent | |

| Matthews et al 201542 (NCT01473381) | Vilazodone 40 mg/day (n=291) | 65.9% | −17.6 (0.7)**, e | 64.6%** | 18 | 33.5%d | 24 | Not reported | N/A |

| Vilazodone 20 mg/day (n=292) | 69.1% | −17.3 (0.6)††, e | 64.2%** | 19 | 29.9%e | 47 | Not reported | N/A | |

| Citalopram 40 mg/day (n=289) | 70.9% | −17.5 (0.6)‡‡ | 62.9%* | 20 | 31.1% | 35 | Not reported | N/A | |

| PLC (n=290) | 74.7% | −14.8 (0.6) | 50.5% | Referent | 26.3% | Referent | Not reported | N/A | |

| Rickels et al 200943 (NCT00285376) | Vilazodone 40 mg/day (n=198) | 74.1% | −12.9 (0.8)**** | 40.0%**, b | 15 | Not reported | N/A | Not reported | N/A |

| PLC (n=199) | 75.1% | −9.6 (0.8) | 28.0% | Referent | Not reported | N/A | Not reported | N/A | |

Notes: Key for statistical comparisons: Vilazodone 40 mg/day vs PLC, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001; Vilazodone 20 mg/day vs PLC, †p<0.05, ††p<0.01, †††p<0.005, ††††p<0.001; Citalopram 40 mg/day vs PLC, ‡p<0.05, ‡‡p<0.01, ‡‡‡p<0.005, ‡‡‡‡p<0.001. aSustained response was defined as MADRS total score ≤ 12 for at least two consecutive study visits. Response rates in the vilazodone (58% to 65%) and placebo groups (36% to 51%) were higher when response was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction (improvement) in MADRS total score from baseline. bResponse was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction (improvement) in MADRS total score from baseline. cRemission was defined as MADRS total score < 10. dRepresents differences in LS-mean (95% CI) change from baseline (vilazodone vs PLC) or the number needed to treat (NNT) with vilazodone vs PLC for response or remission. NNT calculations were performed by the author using the intention-to-treat (ITT) population. eNo data for statistical comparisons between vilazodone treatment groups and the citalopram group were available.

In each trial, the antidepressive efficacy of vilazodone was examined at 1 and 2 weeks. There was significantly greater improvement in MADRS and HAMD-17 total scores with vilazodone 40 mg/day than placebo at week 1 in one phase III trial,43 and significantly greater improvement in MADRS scores with vilazodone 40 mg/day than placebo at week 2 in one Phase IV trial.40 There was no evidence of early benefit from vilazodone relative to placebo in the remaining trials, including the study by Matthews et al,42 in which neither vilazodone dose (20 or 40 mg) nor citalopram showed evidence of antidepressive efficacy at 2 weeks or earlier.

Switch Studies

The efficacy of vilazodone for patients with MDD who failed to respond to a prior trial of antidepressant has received only limited investigation. In an 8-week randomized trial of 70 adults with MDD who had an inadequate response to previous treatment with SSRIs or SNRIs,45 subjects received vilazodone at starting doses of 10, 20, or 40 mg/day. There was a significant reduction in MADRS total score from baseline to week 8 in the sample as a whole; however, there were no significant differences in antidepressant efficacy between any of the vilazodone treatment groups. In a separate double-blind switch study, 42 patients with MDD who failed to respond to a prospective 6-week trial of citalopram 20 mg/day were randomly assigned to citalopram 40 mg/day or vilazodone 20 mg/day.46 Further clinical improvement was observed during the additional 6 weeks of double-blind treatment, but no significant between-group differences in any efficacy measures were observed.

Comparative Efficacy

Studies of the efficacy of vilazodone versus other antidepressants are also sparse. Only one large randomized, placebo-controlled trial of vilazodone for MDD included an additional antidepressant, citalopram.42 However, the clinical effects of vilazodone and citalopram were compared with placebo and not with each other. These data were re-analyzed by Wagner et al,47 who reported that vilazodone 40 mg/day and citalopram 40 mg/day had similar reductions in MADRS scores from baseline to week 10 (−17.6 vs −17.5 points) and similar rates of positive treatment response (65% vs 63%).

Three small, randomized trials compared the clinical effects of vilazodone with other antidepressants in depressed adults. In the first study, 60 depressed patients were randomized to 12 weeks of treatment with vilazodone (up to 40 mg/day) or escitalopram (up to 20 mg/day).48 There was an improvement in HAMD scores between baseline and the end of treatment in both treatment groups, with no significant between-group differences observed. In the second study, 60 patients with MDD were randomized to 12 weeks of treatment with vilazodone 40 mg/day or sertraline 50 mg/day.49 Both vilazodone and sertraline resulted in significant improvements in HAMD scores from baseline to the end of treatment with no significant between-group differences reported. In the third study, 60 patients with MDD were randomized to 12 weeks of treatment with vilazodone 20 mg/day, escitalopram 20 mg/day, or amitriptyline 75 mg/day.50 Significant improvement in HAMD and MADRS scores from baseline at 4 and 12 weeks was observed in all three groups. Vilazodone was associated with significantly greater reduction in HAMD and MADRS scores than amitriptyline at 2, 4, and 12 weeks and with significantly greater reduction in HAMD scores at 4 and 12 weeks than escitalopram. All three comparative trials are limited by small sample sizes, open-label designs, and lack of placebo controls.

Elderly Patients

One randomized trial focused on the antidepressive effects of vilazodone in elderly patients.51 In that study, 56 older patients with MDD (mean age, 72 years) and a Folstein Mini-Mental Status Exam score >24 were randomized to 12 weeks of double-blind treatment with flexibly dosed vilazodone (10–40 mg/day) or paroxetine (10–30 mg/day). There was significant improvement in depressive symptoms in both treatment groups; however, no significant between-group differences were observed.

Secondary and Pooled Data Analyses from Acute-Phase Studies

Number Needed to Treat for Response and Remission

Combined results from two randomized trials of vilazodone for MDD yielded a pooled response rate of 42% for vilazodone 40 mg/day (vs 29% for placebo) and a number needed to treat (NNT) of 8.33 Pooled remission rates were 25% for vilazodone 40 mg/day and 18% for placebo, resulting in a NNT of 14. A similar approach was applied to a secondary analysis of data from one phase IV study,40 with an estimated NNT of 8 for response and an NNT of 10 for remission (vs placebo).

Anxious Depression

A separate pooled analysis of data from two randomized trials investigated the effects of vilazodone on anxious symptoms in depressed patients.52 Scores on the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA)53 and the psychic anxiety and somatic anxiety items from the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17)54 improved significantly, compared with placebo. Furthermore, subjects in the pooled dataset were subtyped into anxious (82% of subjects) and non-anxious (18% of subjects) depression groups based on a HAMD Anxiety/Somatization subscale score of ≥7. There was significantly greater improvement in HAMD-17 and MADRS scores with vilazodone than placebo in the anxious depressed, while no significant differences between vilazodone and placebo in depressive symptom improvement were observed in the non-anxious depressed group. There were significantly greater improvements in anxiety measures (HAMA total score, HAMD-17 Anxiety/Somatization subscale score) with vilazodone than placebo in the anxious depressed group.

The results of the pooled analysis above were broadly consistent with those of the phase IV study by Croft et al,40 in which significant improvement in HAMA scores was observed with vilazodone 40 mg/day, compared with placebo. However, in the phase IV study by Matthews et al,42 citalopram 40 mg/day resulted in significantly greater improvement in Hamilton Anxiety Scale scores than placebo while vilazodone 20 mg/day and vilazodone 40 mg/day did not.

Suicidal Ideation and Behavior

A pooled analysis of data from 8 clinical studies focused on the effects of vilazodone on measures of suicidal ideation, including treatment-emergent suicidality.55 Among patients with suicidal ideation at baseline, a higher proportion of vilazodone-treated patients reported resolution of suicidal ideation during double-blind treatment than subjects who received placebo (39% to 45% vs 29% to 33%). Rates of treatment-emergent suicidal behaviors (eg, preparatory acts, aborted/interrupted attempts, attempted suicide) were similar between vilazodone and placebo (0.3–0.8% vs 0.1–0.7%). The risk of suicidality and suicidal behavior did not differ significantly between younger (aged 18–24 years) and older patients (aged ≥25 years). Like many other antidepressants, the vilazodone package label contains a Black Box warning regarding the potential for increased risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults, and the need to monitor closely for clinical worsening and treatment-emergent suicidality.

Predictors of Treatment Response

The efficacy of vilazodone was examined within subgroups of patients defined by sex (male, female), age group (<45, 45 to <60, and ≥60 years of age), baseline depression severity (MADRS scores <30, 30–34, and ≥35), illness duration (<2, 2 to <10, and ≥10 years), duration of the current depressive episode (≤6, >6 to ≤12, and >12 months), and recurrent illness status (single episode, recurrent) in a pooled analysis of data from all four published short-term randomized trials.56 In all patient subgroups, vilazodone treatment resulted in significantly greater improvement in MDRS total scores than placebo.

Longer-Term and Maintenance Studies

The efficacy results from long-term studies of vilazodone for major depression in adults are summarized in Table 4. In a 12-month open trial of vilazodone 40 mg/day for MDD (616 patients were enrolled following a 2–12-week washout from previous medications), MADRS scores for observed cases improved by 18.5 points at 8 weeks, 21.7 points at week 24, and 22.8 points at week 52.57 In a more rigorous randomized relapse prevention trial, 1204 adults with MDD received 20 weeks of open treatment with vilazodone 40 mg/day.58 Of those, 564 patients achieved a positive response and were randomized to 28 weeks of double-blind treatment with one of the two fixed doses of vilazodone (20 mg/day or 40 mg/day) or placebo. During the double-blind treatment phase, crude rates of relapse, defined as a MADRS total score ≥18 and diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode having been met, were similar between vilazodone 20 and 40 mg/day and placebo (11% vs 13% vs 13%, respectively). There were no significant between-group differences in MADRS total scores during follow-up or time to relapse.

Table 4.

Summary of Efficacy Results from Longer-Term Studies of Vilazodone for Major Depression in Adults

| References | Study Design | Treatment Group (n) | Completion Rate | Main Efficacy Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive Symptom Change from Baseline | Response Rate | Remission Rate | ||||

| Robinson et al 201157 | 12-month, single-arm, open-label | Vilazodone 40 mg/day (n=616) | 41% | 2 months: −18.5a 6 months: −21.7a 12 months: −22.8a |

Not reported at any time point | Not reported at any time point |

| Crude relapse ratec | Time to first relapse, HR (95% CI)d | |||||

| Durgam et al 201858 e | 28-week, double-blind relapse prevention trialf | Vilazodone 40 mg/day (n=187) | 65% | +0.6b | 13% | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.9) |

| Vilazodone 20 mg/day (n=185) | 64% | +0.8b | 11% | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6) | ||

| PLC (n=192) | 71% | +0.5b | 13% | Ref. | ||

Notes: aIndicates the change from baseline in MADRs total scores at each specified time point (2 months, 6 months, or 12 months). bIndicates change from baseline in MADRS total scores at the last non-missing assessment prior to randomization. cRelapse was defined as a MADRS total score of ≥ 18 and satisfying DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode at any visit; MADRS total score of ≥ 18 at any two consecutive study visits; discontinuation of study drug owing to inefficacy (worsening of depression necessitating a switch in medication and a ≥ 2-point increase [worsening] from randomization in CGI-S score); or hospitalization due to worsening depression. dThe primary efficacy endpoint was time to first relapse (in days) during the double-blind relapse-prevention phase of the study. Hazard ratios (with 95% CIs) were reported without mean times to first relapse. eAll data shown in the table are from the double-blind relapse-prevention phase of the study. fThis study was conducted in two phases, beginning with 20 weeks of open treatment with vilazodone 40 mg/day. Patients who achieved positive treatment response during open treatment were randomized to 28 weeks of double-blind treatment with vilazodone 40 mg/day, vilazodone 20 mg/day, or placebo.

Abbreviations: CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression severity sub-scale; DB, double-blind; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th Edition, Text Revision; HR (95% CI), hazard ratio with 95% confidence interval; MADRS, Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale; PLC, placebo.

Safety and Tolerability

Pooled Analyses of Data from Short-Term Randomized Trials

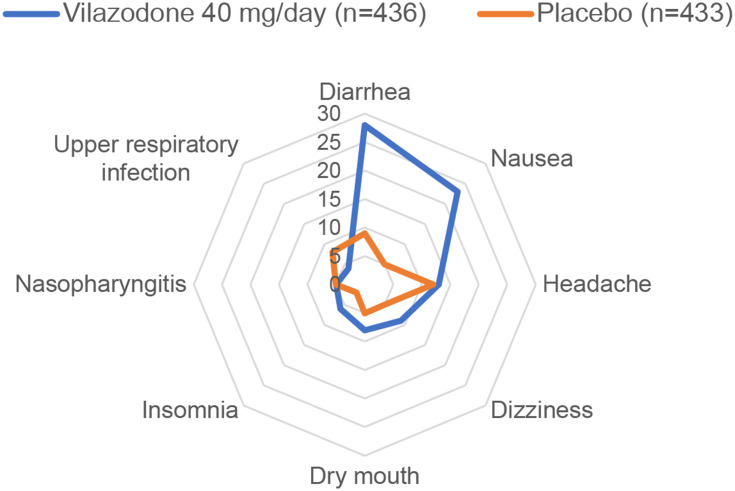

Common adverse effects of vilazodone (≥5% of patients) in short-term randomized trials were diarrhea, nausea, headache, dizziness, dry mouth, insomnia, and nasopharyngitis (Figure 2).59 Most adverse effects were mild or moderate in severity and fewer than 5% of cases required treatment. Rates of discontinuation due to adverse effects were 7% with vilazodone and 3% with placebo in short-term studies.59 In pooled analyses of safety data from two randomized 8-week trials, a higher percentage of patients stopped vilazodone due to adverse effects than placebo (7% vs 3%), with NNH of 27.33,60 Adverse effects that occurred with significantly greater frequency with vilazodone included nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, sexual dysfunction, and insomnia.33 In reanalysis data from one randomized trial,47 the adverse effect profiles of vilazodone 40 mg/day and citalopram 40 mg/day were similar; however, rates of diarrhea (27% vs 11%) and vomiting (7% vs 2%) were higher with vilazodone than citalopram.

Figure 2.

Frequency of selected adverse effects based on pooled data from short-term trials of vilazodone for major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults. This graph displays the pooled frequencies of selected treatment-emergent adverse effects with vilazodone 40 mg/day (n=436) and placebo (n=433) using data from two 8-week randomized phase III trials of vilazodone for MDD in adults.59 Each ring in the graph represents the frequency of specified treatment-emergent adverse effects (TEAEs), ranging from 0% (at the center) to 30% (at the outer edge). Only selected adverse effects that occurred in ≥ 5% of patients randomized to either vilazodone or placebo are shown.

Safety Data from Longer-Term Studies

Longer term safety data of vilazodone for MDD are from one 52-week single-arm trial and one 24-week randomized relapse prevention trial.57,58 In the 52-week trial, the most frequent adverse effects with vilazodone were diarrhea (36%), nausea (32%), and headache (20%). For over 94% of cases, the severity of these adverse effects was mild to moderate. Most adverse effects occurred within the first week of initiating vilazodone treatment and persisted for a median duration of 7 days. Adverse effects leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 21% of patients—typically nausea and diarrhea. During the initial 20-week open treatment phase of the randomized relapse prevention trial, 8% of patients were discontinued from the study due to adverse effects, the most common of which were diarrhea, nausea and headache.58 Most cases of diarrhea and nausea resolved within 2 weeks with ongoing treatment.58 During the 28-week double-blind relapse-prevention phase, 3% of patients randomized to vilazodone 20 mg/day and 0.5% of patients randomized to vilazodone 40 mg/day or placebo dropped out owing to adverse effects.

Specific Adverse Effects

Sexual Dysfunction

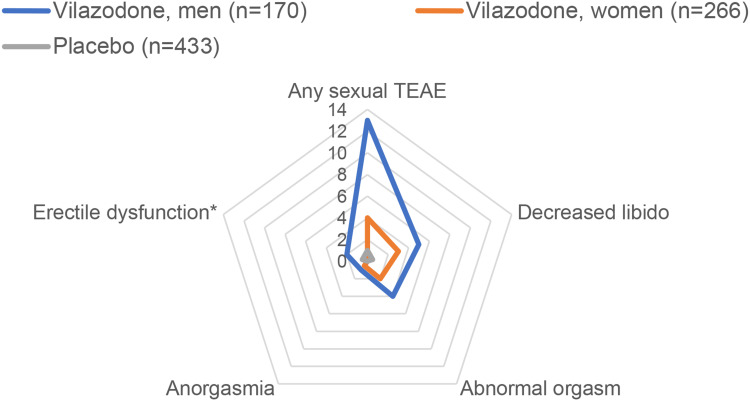

Frequencies of any and specific adverse effects on sexual functioning with vilazodone in short-term trials are shown in Figure 3. A pooled analysis of data from the two randomized trials and one 52-week single-arm study focused on the effects of vilazodone 40 mg/day on various measures of sexual functioning.59 There were high frequencies of sexual dysfunction at baseline (50% in men, 68% in women) across all three studies. In the phase III studies, rates of sexual dysfunction, defined by Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX)62 or Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ)63 cutoff scores, declined from baseline to end of treatment with both vilazodone (from 51% to 48% in men and from 69% to 55% in women) and placebo (from 45% to 40% in men and from 71% to 59% in women). ASEX and CSFQ scores did not change meaningfully from baseline to 8 weeks with vilazodone compared with placebo in men or women in either of the phase III randomized trials;41,43 however, among patients with no sexual dysfunction at baseline, 8% of vilazodone-treated patients and 1% of those who received placebo reported at least one incident adverse effect on sexual functioning.59 Among those who received vilazodone, decreased libido was reported by 5% of men and 3% of women, orgasmic dysfunction was reported by 4% of men and 2% of women, and delayed ejaculation and erectile dysfunction were reported by 2% of men.

Figure 3.

Frequency of selected adverse effects on sexual functioning, based on pooled data from short-term randomized trials of vilazodone for major depressive disorder in adults. This graph displays the pooled sex-specific frequencies of treatment-emergent adverse effects (TEAEs) with vilazodone (n=197) and placebo (n=198) on sexual performance by spontaneous self-report.61 Each ring in the graph represents the frequency of specified treatment-emergent adverse effects (TEAEs), ranging from 0% (at the center) to 14% (at the outer edge). * Erectile dysfunction is reported for men only.

One randomized trial compared the effects of vilazodone 40 mg/day, vilazodone 20 mg/day, paroxetine 20 mg/day, and placebo on CSFQ total scores over 5 weeks in 199 healthy, sexually active adults.64 Adherence was assessed using plasma drug concentrations. In the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, there were no significant differences in CSFQ scores between placebo and any active treatment, including paroxetine. As such, the main study results were analogous to a failed trial. However, in a modified ITT population in which the analyses were restricted to individuals who were adherent to study drugs, changes in CSFQ scores were similar between both vilazodone doses and placebo and were significantly worse with paroxetine than vilazodone 20 mg/day (but not vilazodone 40 mg/day).

Changes in Body Weight

In short-term trials, mean changes in body weight were comparable between vilazodone and placebo (0.2 kg to 0.4 kg vs 0.1 kg to 0.4 kg).40,41 The short-term rates of clinically significant weight gain (≥7% from baseline) were 1% with vilazodone and 0.4% with placebo.40 In a long-term open study,57 mean increase in body weight with vilazodone was 1.7 kg at 52 weeks. Only 2 patients discontinued the trial due to weight gain. During the 20 weeks of open treatment with vilazodone 40 mg/day that preceded the 24-week double-blind relapse prevention phase, body weight gain was reported by 4% of participants.58 During the double-blind phase, weight gain was reported by 5% of individuals who received continued treatment with vilazodone 40 mg/day, 3% of those who received vilazodone 20 mg/day, and 2% who were randomized to placebo.

Cardiac Conduction

There were no significant electrocardiographic changes from baseline in the rate-corrected QT interval (QTc) or occurrences of clinically significant QTc prolongation with vilazodone treatment in randomized short-term trials.40–43 No treatment-related changes in electrocardiographic parameters were observed in the 52-week single-arm study of vilazodone for MDD,57 and only non-significant changes in the QTc occurred during the open (20 weeks) and double-blind (24 weeks) phases of the randomized relapse prevention trial.58 In a more definitive study of vilazodone effects on cardiac conduction, healthy subjects were randomized to receive vilazodone, moxifloxacin, or placebo.65 The starting dose of vilazodone was 10 mg/day, which was then escalated every 3 days to 20, 40, 60, and 80 mg/day. There were no significant effects of any vilazodone dose on QTc, heart rate, PR interval, or QRS interval duration.

Discontinuation Syndrome

Discontinuation syndrome symptoms (eg, dysphoric mood, dizziness, irritability, agitation, anxiety, headache, flu-like symptoms, and confusion) have not been described in patients who abruptly stop treatment with vilazodone. Nevertheless, since vilazodone acts as a serotonin reuptake inhibitor, a gradual tapering down of the vilazodone dose over 1–2 weeks is recommended whenever possible for patients who need to discontinue treatment.38 Patients should be monitored for discontinuation syndrome symptoms even with gradual dose reduction. Based on clinical experience with vilazodone and other antidepressants, some patients may require a more protracted tapering period lasting several weeks.

Pregnancy and Lactation

The reproductive safety of vilazodone is poorly understood, including lack of sufficient data on vilazodone and the risk of spontaneous abortion/stillbirth, major or minor congenital malformations, adverse neonatal events (such as neonatal seizures, preterm delivery, large or small for gestational age delivery, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, etc.), and neurocognitive or neurobehavioral maldevelopment in exposed offspring. There is also a lack of specific data on the lactational safety of vilazodone.

Overdose and Toxicity

Based on poison control registry data, the clinical signs of vilazodone toxicity most commonly include drowsiness, vomiting, tachycardia, and agitation.66 The case-fatality rate of vilazodone poisoning is unknown. Vilazodone may be associated with cases of serotonin toxicity even when ingested as the primary agent.67

Discussion

Is Vilazodone Effective?

Vilazodone is effective for the acute treatment of moderate-to-severe MDD in adults based on four positive randomized trials. Differences between vilazodone and placebo on the primary endpoint in each trial—change from baseline in MADRS total scores—were statistically significant but small (2.5 to 5.1 points). However, the differences in improvement in MADRS scores between vilazodone and placebo overlap with the 2- to 4-point advantage of most antidepressants over placebo for MDD in short-term randomized trials.68,69 Moreover, the pooled comparative response rates with vilazodone versus placebo from the phase III trials yielded an NNT of 8,33 which exceeds a minimal clinically important difference threshold of 10 for antidepressant-placebo comparisons for randomized trials.70

The effects of vilazodone for more stringent secondary outcomes are less consistent. Small differences in rates of sustained response with vilazodone and placebo were observed in phase IV trials,40,42 only one of which documented a statistically significant advantage with vilazodone.40 The rate of symptomatic remission, considered the goal of antidepressive treatment by clinicians and patients,71 was numerically but not significantly higher with vilazodone than placebo in the only trial that included remission as an outcome measure.41 Others have suggested that high placebo response rates and the need for vilazodone dose titration may have obscured differences in treatment outcome between vilazodone and placebo in short-term trials.72 However, with only one exception,42 the placebo response rates in short-term vilazodone trials were comparable to average placebo response rates for other antidepressant trials.73 Furthermore, all studies had 6 to 8 weeks of double-blind treatment with vilazodone at target doses—a time duration that equals or exceeds the minimum duration of antidepressant treatment needed to determine its effectiveness.74

The effectiveness of vilazodone as a long-term maintenance treatment has not been satisfactorily demonstrated. In the only published relapse-prevention trial, relapse rates did not differ significantly between two fixed doses of vilazodone and placebo.58 Little information was available about risk factors for relapse in the study sample, such as comorbid anxiety disorders, age of onset of depression, childhood adversity, and others.75 However, the inclusion criteria for the study required that patients have a history of at least three lifetime major depressive episodes including the current depressive episode. Thus, all participants would have qualified for antidepressant maintenance treatment.76 The low rates of relapse that were observed across treatment groups (11% to 13%) raise the question of whether 28 weeks of double-blind follow-up were sufficient for capturing enough relapse events to permit meaningful comparisons between vilazodone and placebo. Though relatively brief compared with other relapse prevention trials, the 28-week relapse prevention phase in the vilazodone study is consistent with previous studies showing benefit of other antidepressants versus placebo after 24 weeks following acute treatment.77 Additional randomized relapse-prevention studies of vilazodone for MDD are needed, ideally with at least a year of post-randomization follow-up, placebo controls and additional active treatment arms.

How Does Vilazodone Compare with Other Antidepressants?

The effectiveness of vilazodone compared to other antidepressants is unknown. In the only randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial that included an additional active treatment arm, vilazodone appeared to be as effective as citalopram 40 mg/day based on their separate effects relative to placebo–not direct statistical comparisons against each other.42 Four small, randomized trials of vilazodone versus other antidepressants for MDD have been published. However, these studies were not blinded and lacked placebo controls.48–51 Short-term response rates and NNTs for response with vilazodone are generally consistent with those of other FDA-approved antidepressants,77 which suggests comparable effects. Nevertheless, well-powered, randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled comparisons of vilazodone and other serotonergic antidepressants, particularly SSRIs and SNRIs, are needed.

Vilazodone has not yet been shown to have an earlier onset of antidepressive efficacy than other agents, and there is no good evidence that the antidepressive efficacy of vilazodone is substantially different than other antidepressants at interim decision points (eg, at 4 weeks, etc.) supported by treatment algorithms. Instead, could vilazodone have differential efficacy for important subpopulations of depressed patients, such as persons with MDD and comorbid anxiety disorders or symptoms?78,79 Randomized trials have shown vilazodone to be efficacious for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD),80–82 which frequently occurs with MDD.83 However, there is no evidence that vilazodone is more efficacious than SSRIs or SNRIs for MDD with co-occurring GAD or anxiety symptoms. We are unaware of large, randomized trials of vilazodone for other anxiety or trauma-related disorders that commonly occur with MDD, such as panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, subthreshold anxiety disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder. To our knowledge, the efficacy of vilazodone has not been tested for other common depressive subtypes such as mild-to-moderate MDD and subthreshold depression.84

It is not yet clear if the adverse effect or safety profiles of vilazodone vary to a clinically significant degree from other antidepressants. The most frequently observed adverse effects with vilazodone are similar to other serotonergic antidepressants, including SSRIs and SNRIs. Like SSRIs and SNRIs, vilazodone appears to have a favorable longer-term safety profile, including low incidence of significant body weight gain. Vilazodone effects on cardiac conduction appear to be minimal at clinically relevant doses. Like many antidepressants, the reproductive and lactational safety profiles of vilazodone are unknown.85,86 The comparative risk of discontinuation syndrome symptoms with rapid discontinuation of vilazodone is also unknown; however, even if such risk was lower with vilazodone than with other antidepressants, the clinical significance would be questionable given that tapering is recommended for most agents to prevent serotonergic rebound,87 vilazodone included.38

A possible advantage of vilazodone over SSRIs or SNRIs for adverse effects on sexual functioning has been proposed, based primarily on its 5-HT1A partial agonist effect.88 If substantiated, differential effects on sexual functioning with vilazodone would be relevant because of the high rates of sexual dysfunction caused by antidepressants and the risk of premature discontinuation of antidepressants owing to sexual side effects.89,90 However, it is unknown if vilazodone has a lower risk of sexual dysfunction than SSRIs or SNRIs. The low, placebo-like effects of vilazodone on sexual side effects in randomized trials may be the result of bias introduced by high frequencies of sexual dysfunction across treatment groups at baseline.61 The relatively low incidence (8%) of sexual side effects with vilazodone among depressed patients with no baseline sexual dysfunction is encouraging. However, the only randomized placebo-controlled comparison of vilazodone and an alternative antidepressant (paroxetine) lacked assay sensitivity.64 Therefore, available results should be interpreted cautiously, and more direct comparisons between vilazodone and other antidepressants on measures of sexual interest and performance are needed.

Clinical Use of Vilazodone

Despite the more recent research efforts reviewed herein, it remains difficult to discern vilazodone’s exact place among first-, second-, and third-line pharmacological options for treating MDD in adults. Confusion regarding the relative priority of vilazodone in the treatment of adults with MDD is reflected in conflicting recommendations for vilazodone in practice guidelines. For example, in the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) practice guideline for treating adult depression in primary care, vilazodone is mentioned as being among the antidepressants that are “frequently recommended” as a first-line treatment option.91 On the other hand, vilazodone is classified as a second-line antidepressant in the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines based on lack of data on comparative effectiveness and prevention of depressive relapses.76 Other guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of MDD that were published or updated since vilazodone’s regulatory approval either highlight vilazodone’s mechanism of action without making specific recommendations regarding its clinical use or do not mention vilazodone specifically.92–95 Additionally, while vilazodone has several features in common with first-line antidepressants (including evidence of short-term efficacy from high-quality randomized trials and favorable short- and long-term adverse effect and safety profiles), many established first-line agents are mostly generic and are less expensive than vilazodone. As such, clinicians, patients, and payors will be looking for specific advantages of vilazodone that justify its higher cost.

Vilazodone is distinguished from nearly all other antidepressants by its mechanism of action (combining serotonin reuptake inhibition with 5-HT1A partial agonist activity); however, it is still unclear whether this translates into specific advantages over other antidepressants in terms of efficacy or adverse effects. Vilazodone’s efficacy in treatment-resistant depressed patients has not been tested, and its effectiveness for those who have failed to respond adequately to SSRIs or SNRIs has received only preliminary investigation. It is unknown if switching to vilazodone is more effective than switching within class (eg, from one SSRI to another, etc.) or from an SSRI to an SNRI. Still, vilazodone is different enough from first-line serotonergic antidepressants that it is probably worth trialing in patients who do not respond to (or cannot tolerate) SSRIs or SNRIs, absent prohibitive constraints related to drug cost. Based on available evidence, alternatives to vilazodone should be considered in the context of pregnancy and lactation and for depressed patients with a history of poor response after adequate trials of at least two antidepressants from two or more medication classes.

When vilazodone is used, all doses should be taken with food. Therefore, when vilazodone appears to be ineffective at adequate doses, it is prudent to inquire directly about adherence to instructions that it be taken with food, in addition to checking compliance, drug interactions (including strong CYP3A4 inducers), and other potential reasons for inadequate response. If vilazodone is poorly tolerated at a target dose of 40 mg/day, it may be reasonable to ensure that the patient is not a pharmacogenetic poor metabolizer at CYP3A4 (if such information is available) and that the patient is not taking potent CYP3A4-inhibiting medications. In such cases, a 50% reduction in dose may improve tolerability while ensuring adequate vilazodone exposure.

We generally consider vilazodone therapy in adults with MDD who have failed to respond to an initial trial of antidepressants—most typically with SSRIs—or after failing to respond to a second antidepressant trial. Based on the broad literature regarding vilazodone’s clinical effects in patients with MDD, including more recently published studies and secondary analyses, vilazodone may be an attractive option for patients with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder or MDD with anxious distress, and possibly when prior therapeutic trials were limited by sexual dysfunction (and bupropion or mirtazapine are not desirable alternatives). In our experience, access to vilazodone may be limited for many patients due to drug costs and the need for preauthorization, even after failure to respond to first-line and other agents. Although the cardiac safety profile of vilazodone appears favorable, it is too soon in our opinion to prioritize vilazodone over antidepressants for which a more comprehensive knowledge base exists for treating depressed patients with pre-existing heart disease.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although vilazodone has been available for over a decade, it is still among the newest approved antidepressants for treating MDD in adults. Positive results from short-term randomized trials have formed the basis for regulatory approval of vilazodone for MDD. Vilazodone’s combined serotonin reuptake inhibition and 5-HT1A partial agonist effects have invited speculation about possible advantages over other antidepressants. However, after a decade of use, well-powered randomized comparative effectiveness trials are still needed to determine whether such advantages for vilazodone exist. Reasons for the lack of such studies are likely to involve the logistical challenges and high anticipated costs of conducting comparative outcome studies. Large sample sizes will be needed to detect what are likely to be relatively small differences between vilazodone and other approved antidepressants, even if such differences are clinically meaningful. Therefore, future research endeavors involving vilazodone are likely to focus on broadening its indications to important groups of depressed patients for which the evidence base is sparse and to anxiety disorders. There remains a pressing need for studies suitable for determining its effectiveness as a continuation and maintenance therapeutic. Given the importance of adverse antidepressant effects on sexual functioning, randomized comparison studies of incident sexual side effects with vilazodone and other antidepressants in depressed patients with no sexual dysfunction at baseline are also needed. There are unanswered questions regarding vilazodone’s effectiveness in people with MDD who have not tolerated or responded to trials of SSRIs or SNRIs, leaving its role as a potential next-step treatment following the failure of first-line therapeutics unclear. Finally, registry data will hopefully shed light on the reproductive safety data of vilazodone in the relatively near future.96

Disclosure

WVB’s research has been supported by NIMH, AHRQ, NSF, the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, and the Myocarditis Foundation. WVB has contributed chapters to UpToDate regarding the pharmacological treatment of adults with bipolar major depression. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Depression. Fact sheet No. 369; 2012. Available from: www.who.int.medicentre/factsheets/fs369/en/. Accessed October 25, 2015.

- 2.Greenberg PE, Fournier -A-A, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(2):155–162. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Phillips ML. Major depressive disorder: new clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1045–1055. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60602-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1357–1366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(11):722–785. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culpepper L, Muskin PR, Stahl SM. Major depressive disorder: understanding the significance of residual symptoms and balancing efficacy with tolerability. Am J Med. 2015;128(9 suppl):S1–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fabbri C, Di Girolamo G, Serretti A. Pharmacogenetics of antidepressant drugs: an update after almost 20 years of research. Am J Med Genet Part B. 2013;162B(6):487–520. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Blondeau C, et al. Combination antidepressant therapy for major depressive disorder: speed and probability of remission. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trivedi MH, Lin E, Katon W. Consensus recommendations for improving adherence, self-management, and outcomes in patients with depression. CNS Spectr. 2007;12(8 suppl 13):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz TL, Siddiqui UA, Stahl SM. Vilazodone: a brief pharmacological and clinical review of the novel serotonin partial agonist and reuptake inhibitor. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2011;1(3):81–87. doi: 10.1177/2045125311409486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Paulis T. Drug evaluation: vilazodone—a combined SSRI and 5HT1A partial agonist for the treatment of depression. IDrugs. 2007;10(3):193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stahl SM. Mechanism of action of the SPARI vilazodone: serotonin 1A partial agonist and reuptake inhibitor. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(2):105–109. doi: 10.1017/S1092852914000169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vilazodone [database on the Internet]. National center for biotechnology information. PubChem. Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Vilazodone. Accessed September 30, 2021.

- 15.Heinrich T, Botther H, Gericke R, et al. Synthesis and structure–activity relationship in a class of indolebutylpiperazines as dual 5‐HT1A receptor agonists and serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2004;47(19):4684–4692. doi: 10.1021/jm040793q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richelson E. Multi-modality: a new approach for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(6):1433–1442. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712001605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slattery DA, Hudson AL, Nutt DJ. Invited review: the evolution of antidepressant mechanisms. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2004;18(1):1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2004.00195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopkins CR. ACS chemical neuroscience molecule spotlight on Viibryd (vilazodone). ACS Chem Neurosci. 2011;2(10):554. doi: 10.1021/cn200084v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu XY, Etukala JR, Eyunni WVK, et al. Benzothiazoles as probes for the 5HT1A receptor and the serotonin transporter (SERT): a search for new dual-acting agents as potential antidepressants. Eur J Med Chem. 2012;53:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.03.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hjorth S, Bengtsson JH, Kullberg A, et al. Serotonin autoreceptor function and antidepressant drug action. J Psychopharmacol. 2000;14(2):177–185. doi: 10.1177/026988110001400208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stahl SM. Mechanism of action of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors. Serotonin receptors and pathways mediate therapeutic effects and side effects. J Affect Disord. 1998;51(3):215–235. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00221-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Celada P, Bortolozzi A, Artigas F. Serotonin 5-HT1A receptors as targets for agents to treat psychiatric disorders: rationale and current status of research. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(9):703–716. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0071-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kishi T, Meltzer HY, Matsuda Y, Iwata N. Azapirone 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist treatment for major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2014;44(11):2255–2269. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whale R, Terao T, Cowen P, et al. Pindolol augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4):513–520. doi: 10.1177/0269881108097714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chessick CA, Allen MH, Thase ME, et al.Azapirones for generalized anxiety disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(6):CD006115. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landen M, Bjorling G, Agren H, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of buspirone in combination with an SSRI in patients with treatment-refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(12):664–668. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v59n1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moll JL, Brown CS. The use of monoamine pharmacological agents in the treatment of sexual dysfunction: evidence in the literature. J Sexual Med. 2011;8(4):956–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02190.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snoeren EMSS, Veening JG, Olivier B, Oosting RS. Serotonin 1A receptors and sexual behaviors in male rates: a review. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;121:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes ZA, Starr KR, Langmead CJ, et al. Neurochemical evaluation of the novel 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist/serotonin reuptake inhibitor, vilazodone. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;510(1–2):49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sahli ZT, Banerjee P, Tarazi FI. The preclinical and clinical effects of vilazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2016;11(5):515–523. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2016.1160051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.VIIBRYD (vilazodone hydrochloride) tablets. Trovis Pharmaceuticals, LLC, New Haven, CT; 2010. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/022567s000lbl.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2022.

- 32.Cruz MP. Vilazodone HCl (Viibryd). Pharm Ther. 2012;37(1):28–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Citrome L. Vilazodone for major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved antidepressant—what is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm and likelihood to be helped or harmed? Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(4):356–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02885.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boinpally R, Alcorn H, Adams MH, et al. Pharmacokinetics of vilazodone in patients with mild or moderate renal impairment. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(3):199–206. doi: 10.1007/s40261-013-0061-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vilazodone. LiverTox: clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury; 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548223/#:~:text=No%20instances%20of%20acute%2C%20clinically,8%20weeks%20of%20starting%20therapy. Accessed February 9, 2022. [PubMed]

- 36.De Picker L, van den Eede F, Dumont G, et al. Antidepressants and the risk of hyponatremia: a class-by-class review of the literature. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):536–547. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das S, Thirthalli J. Does dependent hyponatremia caused by vilazodone: a case report. Asian J Psychiatry. 2019;43:213. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laughren TP, Gobburu J, Temple RJ, et al. Vilazodone: clinical basis for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval of a new antidepressant. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1166–1173. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r06984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bixby AL, VandenBerg A, Bostwick JR. Clinical management of bleeding risk with antidepressants. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(2):186–194. doi: 10.1177/1060028018794005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Croft HA, Pomara N, Gommoll C, et al. Efficacy and safety of vilazodone in major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(11):e1291–e1298. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m08992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan A, Cutler AJ, Kajdasz DK, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week study of vilazodone, a serotonergic agent for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(4):441–447. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathews M, Gommoll C, Chen D, et al. Efficacy and safety of vilazodone 20 and 40 mg in major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30(2):67–74. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rickels K, Athanasiou M, Robinson DS, et al. Evidence for efficacy and tolerability of vilazodone in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(3):326–333. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;124:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reele S, Millet R, Kim S, et al. An 8-week randomized, double-blind trial comparing efficacy, safety, and tolerability of 3 vilazodone dose-initiation strategies following switch from SSRIs and SNRIs in major depressive disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17. doi: 10.4088/PCC.14m01734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grant JE, Redden SA, Leppink EW. Double-blind switch study of vilazodone in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(3):121–126. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagner G, Schultes M-T, Titscher V, et al. Efficacy and safety of levomilnacipran, vilazodone and vortioxetine compared with other second-generation antidepressants for major depressive disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;228:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bathla M, Anjum S. A 12-week prospective randomized controlled compared of trial of vilazodone and sertraline in Indian patients with depression. Indian J Pharmacol. 2020;52(1):10–15. doi: 10.4103/ijp.IJP_618_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bathla M, Anjum S, Singh M, et al. A 12-week comparative prospective open-label randomized control study in depression patients treated with vilazodone and escitalopram in a tertiary care hospital in North India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2019;40(1):80–85. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_368_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kadam RL, Sontakke SD, Tiple P, et al. Comparative evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of vilazodone, escitalopram, and amitriptyline in patients of major depressive disorder: a randomized, parallel, open-Label clinical study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2020;52(2):79–85. doi: 10.4103/ijp.IJP_441_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eyre H, Siddarth P, Cyr N, et al. Comparing the immune-genomic effects of vilazodone and paroxetine in late-life depression: a pilot study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(6):256–263. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-107033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thase ME, Chen D, Edwards J, Ruth A. Efficacy of vilazodone on anxiety symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(6):351–356. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thase ME, Edwards J, Durgam S, et al. Effects of vilazodone on suicidal ideation and behavior in adults with major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder: post-hoc analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(5):281–288. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kornstein S, Chang C-T, Gommoll CP, Edwards J. Vilazodone efficacy in subgroups of patients with major depressive disorder: a post-hoc analysis of for randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;33(4):217–223. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robinson DS, Kajdasz DK, Gallipoli S, Whalen H, Wamil A, Reed CR. A 1-year, open-label study assessing the safety and tolerability of vilazodone in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):643–646. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31822c6741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Durgam S, Gommoll C, Migliore R, et al. Relapse prevention in adults with major depressive disorder treated with vilazodone: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;33(6):304–311. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liebowitz M, Croft HA, Kajdasz DK, et al. The safety and tolerability profile of vilazodone, a novel antidepressant for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2011;44(3):15–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Citrome L. Vortioxetine for major depressive disorder: an indirect comparison with duloxetine, escitalopram, levomilnacipran, sertraline, venlafaxine, and vilazodone, using number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. J Affect Disord. 2016;196:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clayton AH, Kennedy SH, Edwards JB, et al. The effect of vilazodone on sexual function during the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Sex Med. 2013;10(10):2465–2476. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McGahuey CA, Gelenberg AJ, Laukes CA, et al. The Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX): reliability and validity. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(1):25–40. doi: 10.1080/009262300278623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clayton AH, McGarvey EL, Clavet GJ. The changes in sexual functioning questionnaire (CSFQ): development, reliability, and validity. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(4):731–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clayton AH, Durgam S, Li D, et al. Effects of vilazodone on sexual functioning in healthy adults: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, and active-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(1):27–35. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Edwards J, Sperry V, Adams MH, et al. Vilazodone lacks proarrhythmogenic potential in health participants: a thorough ECG study. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;51(6):456–465. doi: 10.5414/CP201826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Heise CW, Malashock H, Brooks DE. A review of vilazodone exposures with focus on serotonin syndrome effects. Clin Toxicol. 2017;55(9):1004–1007. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2017.1332369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baumgartner K, Doering M, Schwarz E. Vilazodone poisoning: a systematic review. Clin Toxicol. 2020;58(5):360–367. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2019.1691221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gibbons RD, Hur K, Brown H, et al. Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of 6-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(6):572–579. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thase ME, Larsen KG, Kennedy SH. Assessing the “true” effect of active antidepressant therapy v. placebo in major depressive disorder: use of a mixture model. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):501–507. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duru G, Fantino B. The clinical relevance of changes in the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale using the minimum clinically important difference approach. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(5):1329–1335. doi: 10.1185/030079908X291958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB, Posternak MA, et al. How should remission from depression be defined? The depressed patient’s perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):148–150. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iranikhah M, Wensel TM, Thomason AR, et al. Vilazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(10):958–965. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.2012.01121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Furukawa TA, Cipriani A, Atkinson LZ, et al. Placebo response rates in antidepressant trials: a systematic review of published and unpublished double-blind randomised controlled studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(11):1059–1066. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30307-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):201–204. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Buckman JEJ, Underwood A, Clarke K, et al. Risk factors for relapse and recurrence of depression in adults and how they operate: a four-phase systematic review and meta-synthesis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;64:13–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 3. pharmacological treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):540–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851–864. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gaspersz R, Nawijn L, Lamers F, Penninx BWJH. Patients with anxious depression: overview of prevalence, pathophysiology and impact on course and treatment outcome. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31(1):17–25. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lydiard RB, Brawman-Mintzer O. Anxious depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 18):10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Durgam S, Gommoll C, Forero G, et al. Efficacy and safety of vilazodone in patients with generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(12):1687–1694. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gommoll C, Durgam S, Mathews M, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose phase III study of vilazodone in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(6):451–459. doi: 10.1002/da.22365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]