Abstract

Low back pain is a leading cause of disability worldwide. Intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration is often associated with low back pain but is sometimes asymptomatic. IVD calcification is an often overlooked disc phenotype that might have considerable clinical impact. IVD calcification is not a rare finding in ageing or in degenerative and scoliotic spinal conditions, but is often ignored and under-reported. IVD calcification may lead to stiffer IVDs and altered segmental biomechanics, more severe IVD degeneration, inflammation and low back pain. Calcification is not restricted to the IVD but is also observed in the degeneration of other cartilaginous tissues, such as joint cartilage, and is involved in the tissue inflammatory process. Furthermore, IVD calcification may also affect the vertebral endplate, leading to Modic changes (non-neoplastic subchondral vertebral bone marrow lesions) and the generation of pain. Such effects in the spine might develop in similar ways to the development of subchondral marrow lesions of the knee, which are associated with osteoarthritis-related pain. We propose that IVD calcification is a phenotypic biomarker of clinically relevant disc degeneration and endplate changes. As IVD calcification has implications for the management and prognosis of degenerative spinal changes and could affect targeted therapeutics and regenerative approaches for the spine, awareness of IVD calcification should be raised in the spine community.

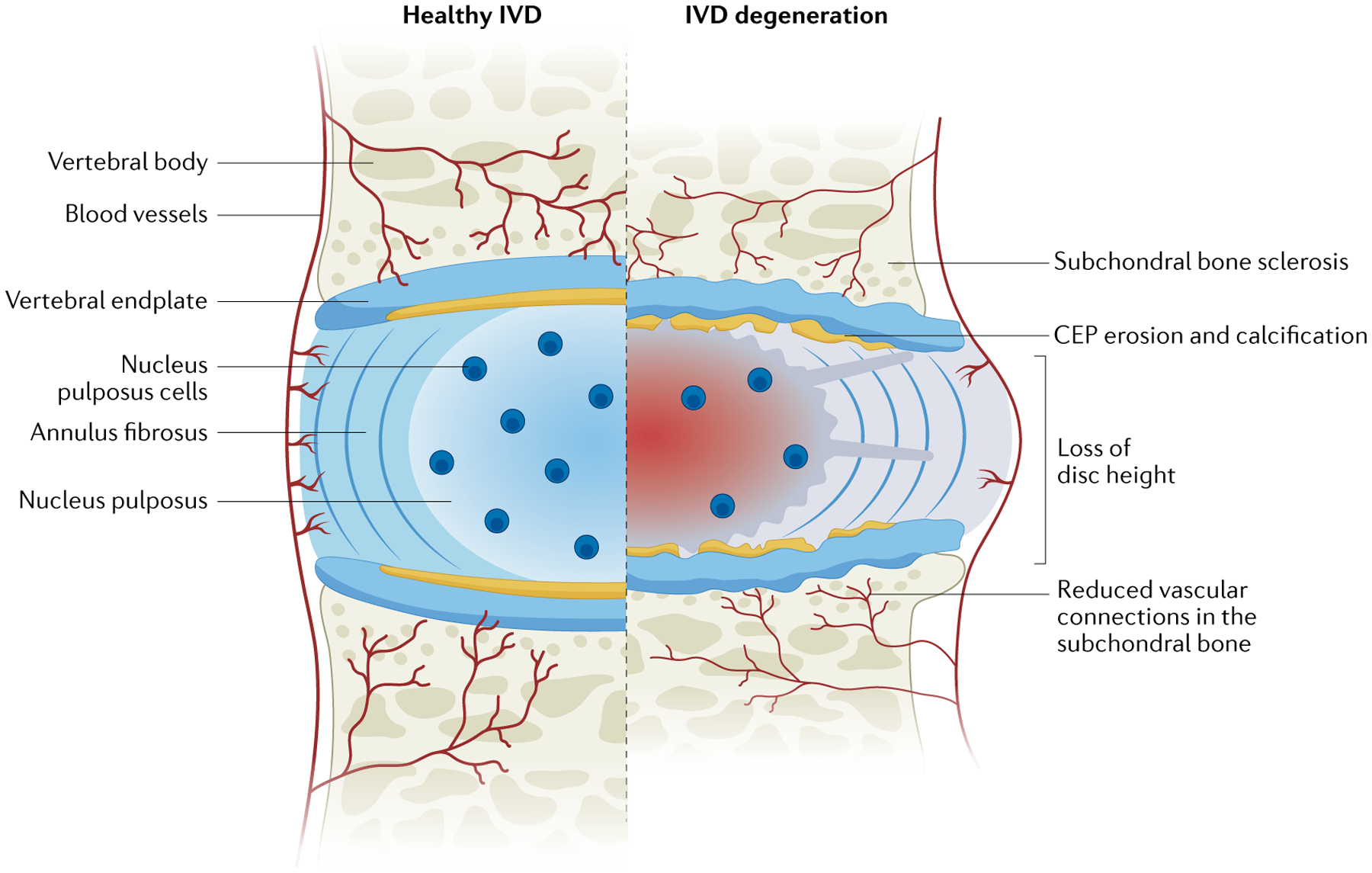

Intervertebral discs (IVDs) are fibrocartilaginous structures that lie between the vertebrae, enable limited movement between the vertebrae and resist spinal compression while distributing the compressive load evenly on the adjacent vertebral bodies. IVDs comprise three main components: the inner nucleus pulposus, the outer annulus fibrosus and the cartilaginous endplates (CEPs)1 (FIG. 1). The nucleus pulposus is a highly hydrated, gelatinous, proteoglycan-rich tissue. The annulus fibrosus encloses the nucleus pulposus and is a highly organized fibrous structure composed of concentric lamellae of tilted collagen fibres with scattered proteoglycans. The nucleus pulposus and the annulus fibrosis are separated from adjacent vertebral bodies by the CEPs, thin layers of hyaline cartilage. Degeneration of the IVD is often involved in low back pain2, and is an intricate event involving multiple morphological, functional and biochemical changes3,4. The degenerated IVD is reduced in height compared with its healthy counterpart owing to extracellular matrix depletion, a fibrous and dehydrated nucleus pulposus, severe structural modifications of annulus fibrosus collagen fibres, extensive damage to the CEP and sclerosis of the subchondral bone (FIG. 1). Among the many degenerative features, IVD calcification can also occur5–7. IVD calcification exists either in the form of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals, which usually deposit in the annulus fibrosus, or as basic calcium phosphate crystals, which affect the central region and are known as calcifying nucleopathy. The resorptive phase of IVD calcification is extremely symptomatic and causes pain, stiffness, paravertebral muscular contracture, and limitation of motion of the spinal segment8,9.

Fig. 1 |. Comparison of a healthy and a degenerated intervertebral disc in the spine.

The intervertebral disc (IVD) is a shock-absorbing structure with three main components: the inner nucleus pulposus, the outer annulus fibrosus and the cartilaginous endplates (CEPs), which anchor the disc to the adjacent vertebrae. The healthy nucleus pulposus is a highly hydrated, gelatinous, proteoglycan-rich tissue. The healthy annulus fibrosus encloses the nucleus pulposus and is a highly organized fibrous structure composed of concentric lamellae of tilted collagen fibres with scattered proteoglycans. The degenerated IVD is reduced in height compared with its healthy counterpart owing to extracellular matrix depletion, a fibrous and dehydrated nucleus pulposus, severe structural modifications of annulus fibrosus collagen fibres, extensive damage to the CEP and sclerosis of the subchondral bone. Reprinted from REF.1, Springer Nature Limited.

For the initial assessment of any spinal pathological condition associated with low back pain, radiography is usually the first diagnostic choice in a clinical setting. Plain radiographs are commonly used to evaluate bony features associated with IVD degenerative characteristics and are a good tool for assessing IVD calcification; however, subtle IVD calcification is sometimes missed owing to either small foci of deposits or rotated or mal-positioned vertebrae. The fact that IVD calcification can easily be missed means that the reported prevalence of IVD calcification is lower in the clinical setting than in cadaveric radiographic studies10. MRI is considered the clinical gold standard method for the qualitative and quantitative assessment of IVDs owing to its sensitivity in assessing soft tissue11. MRIs can assess, to a degree, water content of an IVD, which is an indirect assessment of proteoglycan loss that may not be associated with pain or predict symptoms12. Nonetheless, determining IVD calcification on traditional MRI scans is a challenge in the clinical setting. The correlation of high-intensity zones on MRI with disc calcification has suggested that further improving MRI technology might be helpful in the diagnosis of IVD calcification. High-intensity zones have high specificity and high positive predictive values in identifying a symptomatic IVD13,14; IVD calcification, if synonymous with high-intensity zones, might be more clinically relevant than is currently assumed.

The progression of IVD degeneration is associated with several changes, including functional changes in spinal motion and biomechanical behaviour15. The spinal motion segment has non-linear biomechanical behaviours that vary with loading direction owing to the complex composition and structural organization of the IVD15. Spinal stiffening is generally believed to occur with increasing IVD degeneration but is not always the case, and biomechanical changes with IVD degeneration can be difficult to detect owing to competing changes that can occur as degenerative grade progresses16,17. However, altered mechanics and biomechanical changes can result in disc degenerative changes, especially calcification, as is observed in scoliotic discs18,19. The pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted in disc tissues are known to promote osteoprogenitor differentiation and angiogenesis, which eventually activate ectopic ossification, and altered biomechanical environment might be one factor that leads to the production of these pro-inflammatory cytokines20.

The strong association of disc degeneration and calcification in the setting of low back pain10 has raised awareness of the clinical importance of this degenerative feature. The inability of conventional imaging techniques, such as plain radiography and MRI, to detect IVD calcification might explain why clinically relevant spinal phenotypes have not previously been defined.

Epidemiology of IVD calcification

The first description of IVD calcification dates back to 1858 in a textbook of anatomy entitled Die Halbgelenke des menschlichen Körpers written by German anatomist Hubert von Luschka21. Later, in 1897, Beneke demonstrated the presence of IVD calcification on cadaveric radiographs22,23. IVD calcification was first shown on human spine radiographs by Calvé and Gallandin 1922 (REFS21,22). IVD calcification can occur in association with certain systemic disorders, such as ochronosis, haemochromatosis, chondrocalcinosis and hyperparathyroidism21, and also in the setting of spinal deformities such as scoliosis, or in progressive inflammatory or congenital conditions whereby the IVD exhibits ossification18. These conditions mostly involve multiple IVDs, whereas calcification resulting from degenerative IVD disease can manifest as focal IVD involvement24. Reports of asymptomatic and symptomatic IVD calcification in children have been reported sporadically25–29. In most paediatric cases, IVD calcification predominantly occurs in the lower cervical and upper thoracic regions and tends to regress spontaneously30–32; however, IVD calcification can affect the lower lumbar spine as well33,34. In children, IVD calcification sometimes coincides with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament27,35. In adults, the prevalence of radiographic IVD calcification has varied from 5% up to 71% in cadaveric radiographic studies21,23,36,37. However, the sampling of individuals in these studies had methodological flaws, which meant that researchers were unable to gauge the true prevalence, risk factors and clinical relevance of IVD calcification within the different age groups and sexes. The diagnostic tool used to assess IVD calcification has usually been conventional plain radiography and occasionally CT. Some studies tried to establish the role of MRI scans in detecting IVD calcification and reported that high signal intensity on T1-weighted MRI was associated with IVD calcification38,39; however, this interpretation was later challenged, with researchers suggesting that high signal intensity of some calcified IVDs on T1-weighted MRI images was associated with fatty infiltration rather than IVD calcification40,41. Conventional plain radiography may not be the most sensitive imaging modality for assessing IVD calcification, as the rotation and/or tilting of the vertebrae can obscure proper visualization and small calcium deposits might go unnoticed42. As such, the occurrence of IVD calcification may be under-reported and its extent as well as its topography within the IVD remains relatively unknown. In adults, calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate or hydroxyapatite crystals can be deposited in the nucleus pulposus or annulus fibrosus and, unlike paediatric IVD calcification, are permanent in most cases19.

IVD calcification and degeneration

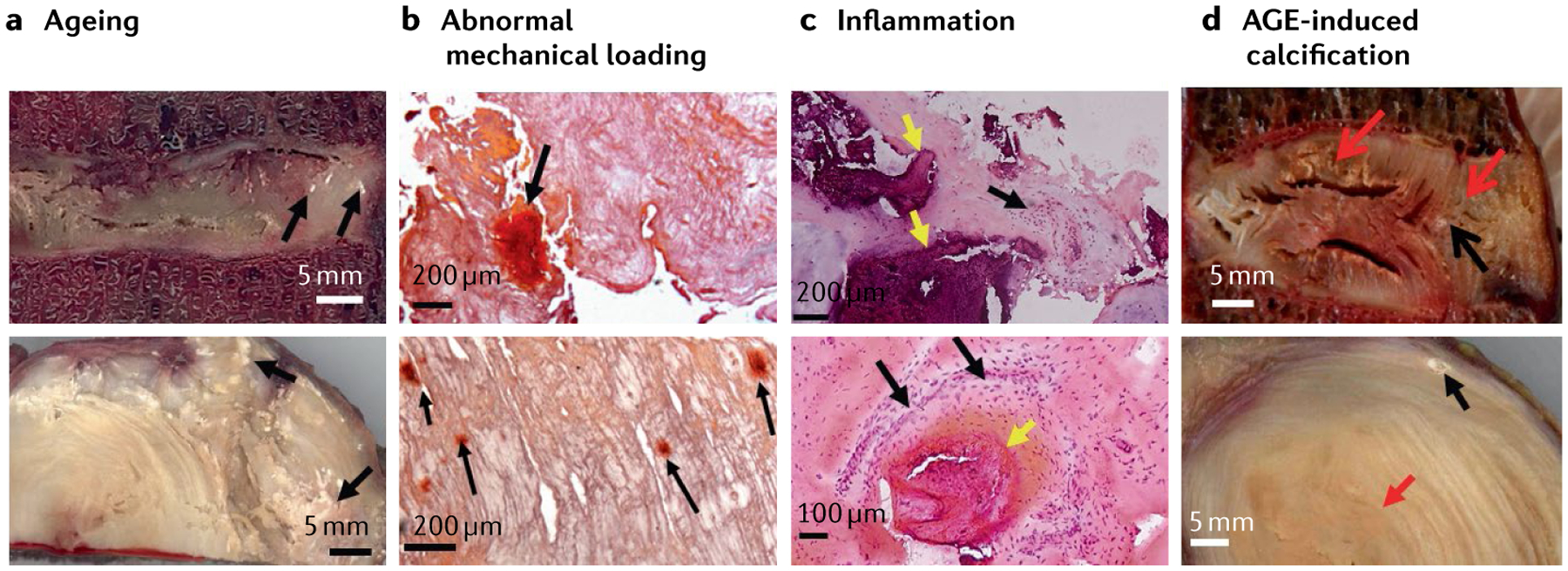

A number of studies have suggested that calcification is a feature of IVD degeneration that tends to increase with increasing grades of degeneration43,44. Studies have also shown that the osteogenic potential of degenerative IVDs increases in direct relation to the severity of degeneration and is related to the enhanced expression of the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR), transcription factors such as osterix (also known as transcription factor Sp7) and Runx, and proteins such as bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) and osteocalcin33,43,45, all of which are markers that have the potential to induce ossification in IVD tissues34,43,46. Active hedgehog signalling has also been shown to correlate positively with the degree of disc degeneration, and Sonic hedgehog proteins had the propensity to facilitate mineral deposition in degenerated nucleus pulposus cells47. On the basis of these insights, it is conceivable that calcification has a role in IVD degeneration (FIG. 2).

Fig. 2 |. Calcification in degenerated discs.

a | Sagittal (top image) and transverse (bottom image) sections of aged intervertebral discs (IVDs) showing several calcified spots (black arrows); scale bar = 5 mm. b | Histological sections of scoliotic discs stained with Alizarin red stain showing that abnormal mechanical loading can induce mineral deposition in the IVDs (black arrows); scale bars = 200 μm. c | Inflammation and calcification are highly associated with each other. H&E stained disc sections of nucleus pulposus (top image) and inner annulus (bottom image) showing the coexistence of inflammation and calcification, calcified deposits (yellow arrows) and adjacent inflammation (black arrows); scale bars upper 200 μm and lower 100 μm. d | Advanced glycation endproduct (AGE)-induced calcification can be seen in the sagittal (top image) and transverse sections (bottom image) of the disc showing the yellowing effect of AGE (red arrows) and calcification (black arrows), suggesting a role of AGEs in calcification; scale bars = 5 mm.

IVD calcification has been observed in all disc locations among patients with IVD degeneration and patients with scoliosis, but the endplate was most frequently affected in patients with scoliosis19,48; calcification is more common in patients with higher degrees of scoliotic deformity. Although scoliosis and IVD degeneration are distinct processes, scoliosis is known to accelerate IVD degenerative changes19,49–51. Hristova et al.18 showed the presence of calcium deposits and collagen type X in IVDs of patients with degenerative disc diseases and patients with scoliosis, but not in control IVDs, and the level of the indicators of calcification potential (for example, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and calcium and inorganic phosphate concentrations) were consistently higher in degenerative and scoliotic IVDs than in control IVDs. These results suggested that IVD degeneration in adults might be associated with ongoing mineral deposition and that the mineralization or calcification process in IVDs from patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) might simply reflect a premature degenerative process.

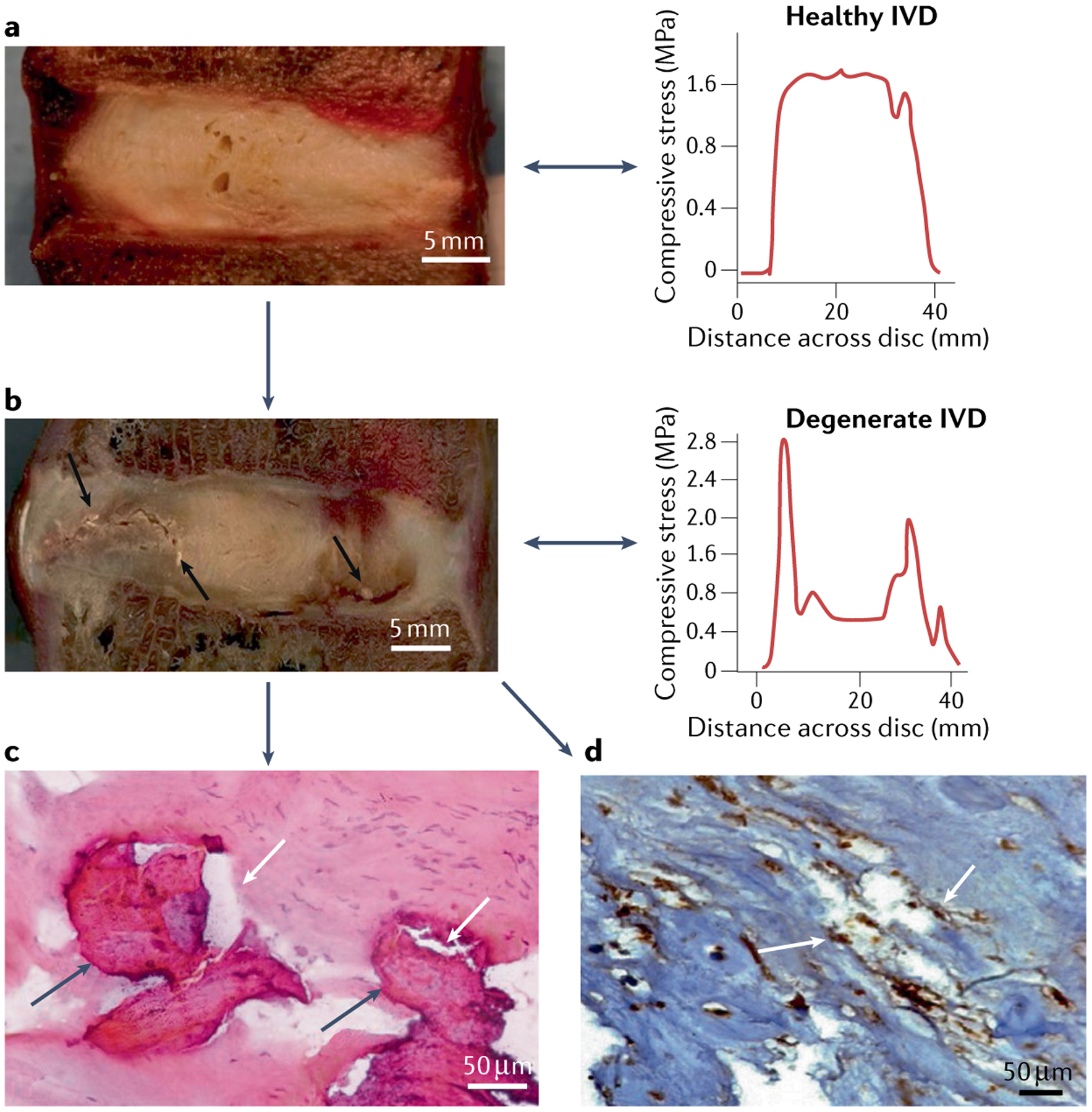

Illien-Junger et al.52 performed histological analyses of human IVDs from several different stages of degeneration and identified areas of calcification within the nucleus pulposus and CEP; these areas of calcification were commonly located close to fissures in degenerated tissue areas (FIG. 3b) and were associated with increased IVD degeneration. The close proximity of calcifications to these IVD defects suggested that calcifications might be nucleation points for these defects. Hard inclusions in soft materials are known to create stress concentrations (areas where the stress is significantly higher than in the surrounding area), and the proximity of the observed calcifications in the relatively soft cartilaginous IVD tissues might have been fracture nucleation sites that initiated cracks and fissures53 (FIG. 3), although CEP defects and/or ruptures are not always associated with IVD degeneration. Excessive calcification is thought to have a role in generalized endplate sclerosis that is assumed to be associated with reduced nutritional supply to the IVD; the occlusion of nutritional channels leads to increased anaerobic metabolism and intradiscal acidity along with reduced metabolic rates and reduced cellularity and could contribute to IVD degeneration54,55. However, a few studies have reported contrary findings and suggested that nutritional diffusion is not interrupted by endplate sclerosis but instead that endplate porosity increases with disc degeneration56,57. These findings suggest that disc degeneration is more mechanically driven rather than being attributed to reduced metabolic transport56,57. IVDs with advanced degeneration, such as Thompson grade V IVDs, involve IVD collapse with extensive ossifications including osteophyte formation, extensive calcification and eventual fusion. Excessive loading and instability can result in IVD collapse and osteophyte formation so that these degenerative changes are mechanically modulated58. As a result, calcifications are likely to contribute to altered biomechanical behaviours (for example, fissure initiation altering IVD stiffness) while also being mechanically modulated (for example, IVD compaction and osteophyte formation from overloading)58.

Fig. 3 |. Images showing presence of fissures near calcified spots.

a | Sagittal image of a cadaveric healthy disc with a representative graph of intradiscal stress; scale bar = 5 mm. b | Sagittal cadaveric section of a degenerated intervertebral disc with fissures (black arrows) near calcified spots with representative images of intradiscal stress; scale bar = 5 mm. The representative images of intradiscal stress show the stress profile of discs: the stress profile of the healthy disc shows an even distribution of stress throughout the disc whereas the stress profile of the degenerated disc shows multiple stress peaks. c | Haematoxylin and eosin stained section of a degenerated intervertebral disc showing coexistence of calcification (dark grey arrows) and fissures (white arrows); scale bar = 50 μm. d | Bone morphogenetic protein 2 immuno-stained sections of a degenerated intervertebral disc, showing association of both calcification and fissures (white arrows); scale bar = 50 μm.

IVD calcification and genetics

Limited evidence in various species suggests that genetic background is involved in IVD calcification. A study in three different mouse strains (C57BL/6, LG/J and SM/J) described different ageing spinal phenotypes59. Notably, the LG/J mouse strain seemed to develop disc calcification at the age of 2 years, equivalent to 70 human years59. This study described in detail the transcriptomic landscape involved in the different ageing and degeneration phenotypes59, but as yet the underlying genes involved in disc calcification in mice remain elusive. In humans, no large-scale, robust study has been performed investigating the genetic underpinnings related to the development of IVD calcification. The −66T > G gene polymorphism in osteopontin has been shown to be associated with susceptibility to cervical spondylotic myelopathy60. Although the underlying mechanism is unknown, it is tempting to hypothesize that this association might be related to the role of osteopontin in the growth plate and in cartilaginous degenerative diseases such as osteoarthritis (OA)61 and IVD degeneration52. In the dachshund, a chondrodystrophic canine breed commonly affected by clinical IVD disease and predis-posed to early-onset IVD degeneration and calcification, a major locus has been identified that affects IVD calcification62. With the aid of targeted resequencing and focusing only on protein-coding regions, two synonymous variants were identified in MB21D1 and one in the 5′-untranslated region of KCNQ5 (REF.63) (which encodes a potassium channel protein) that were associated with IVD calcification. The working mechanism remains unexplored; MB21D1 is a cytosolic DNA sensor and responsible for immune activation, whereas KCNQ5 channels control resting properties of mammalian nerve terminals (synapses)64. In Scandinavian countries, dachshunds are screened for IVD calcification at approximately 2 years old, and preliminary work has shown that IVD calcification at 2 years of age increases the risk of future clinical IVD disease by 42%65. However, dogs treated surgically for IVD herniation at a median age of 74 months are equally likely to present with mineralized IVDs as they are with non-mineralized IVDs, indicating that herniation is not necessarily related to the calcification process itself or perhaps that a different sub-phenotype of IVD changes might exist in the context of calcification66.

Proposed pathogenesis

Physiological and pathological mineralization are complex processes. Although physiological mineralization is regulated within the context of appropriate cellular signalling, pathological calcification encompasses a broad range of processes, some of which involve cells and some of which do not. In adults, IVD calcification is usually perceived as a sign of ageing, although it can also occur in younger adult IVDs22,67. IVD calcification is a frequent finding in degenerated IVDs, but whether it is a cause or a consequence of disc degeneration is not well understood18. IVD calcification might be involved in the accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). AGEs are associated with calcification in multiple conditions including OA and vascular calcification68,69, and researchers have established a role for AGEs in the formation of IVD calcification52. Immunohistochemical assessment of human IVDs demonstrated calcified structures in pericellular regions surrounding cells positive for AGEs, which were often co-localized with collagen type X and osteopontin52. Together with experimental evidence from cell culture studies that demonstrate the role of oxidative stress and consequent degeneration and calcification of both nucleus pulposus52 and CEP cells70, these observations suggest that AGEs induce calcification by increasing the expression of osteogenic markers52,71.

A role for AGE accumulation in IVD calcification has also been suggested in a mouse model in which dietary AGE ingestion was associated with AGE accumulation and calcification in CEPs71. In a mouse model of diabetes mellitus, the same researchers found that fissures and deposition of granulated structures in IVDs correlated with AGE accumulation and the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF72. AGE formation therefore seems to be associated with pro-inflammatory conditions. The potential association of calcification with inflammation has been seen in various vascular studies73,74, but the causal pathway of events is difficult to ascertain75. Microcalcifications are triggered by various cytokines during inflammatory processes; TNF seems to have a particularly important role and might exert its effects by stimulating the release of BMP2, a potent bone anabolic factor73,76. Studies have shown calcification in degenerative IVDs, especially near fissures and tears6,52 (FIG. 3), which supports, at least in part, previous hypotheses that annular fissures and tears are linked with the formation of vascular inflammatory granulation tissue77,78. Investigations have noted increased expression of CaSR in degenerated IVDs, most probably induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF79,80. The common findings of local inflammation and angiogenesis in herniated and ossified discs77–80 indicate that these two processes might be involved in disc calcification. Altered Wnt signalling and the overexpression of some inflammation-related factors are two elements believed to be involved in disc ossification81.

Another mechanism that might induce IVD calcification is abnormal mechanical loading, as is seen in disorders affecting spinal alignment, such as scoliosis18,19 (FIG. 2). Parameters of spinopelvic alignment — in particular low pelvic incidence — can predict disc calcification, which shows that altered biomechanics might induce disc calcification that can affect disc kinematics82. Abnormal mechanical loading has been shown to increase levels of collagen type X83,84, which is a known marker of endochondral ossification84,85. Therefore, altered mechanical loading and uneven distribution of stress in IVDs is a possible factor associated with IVD calcification. Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) is highly expressed by annulus fibrosus cells during altered mechanical loading in degenerative discs6. Annulus fibrosus cells have characteristics of progenitor cells and, under appropriate stimuli, are capable of differentiating into chondrocytes and osteoblasts in vitro as well as in vivo86,87.

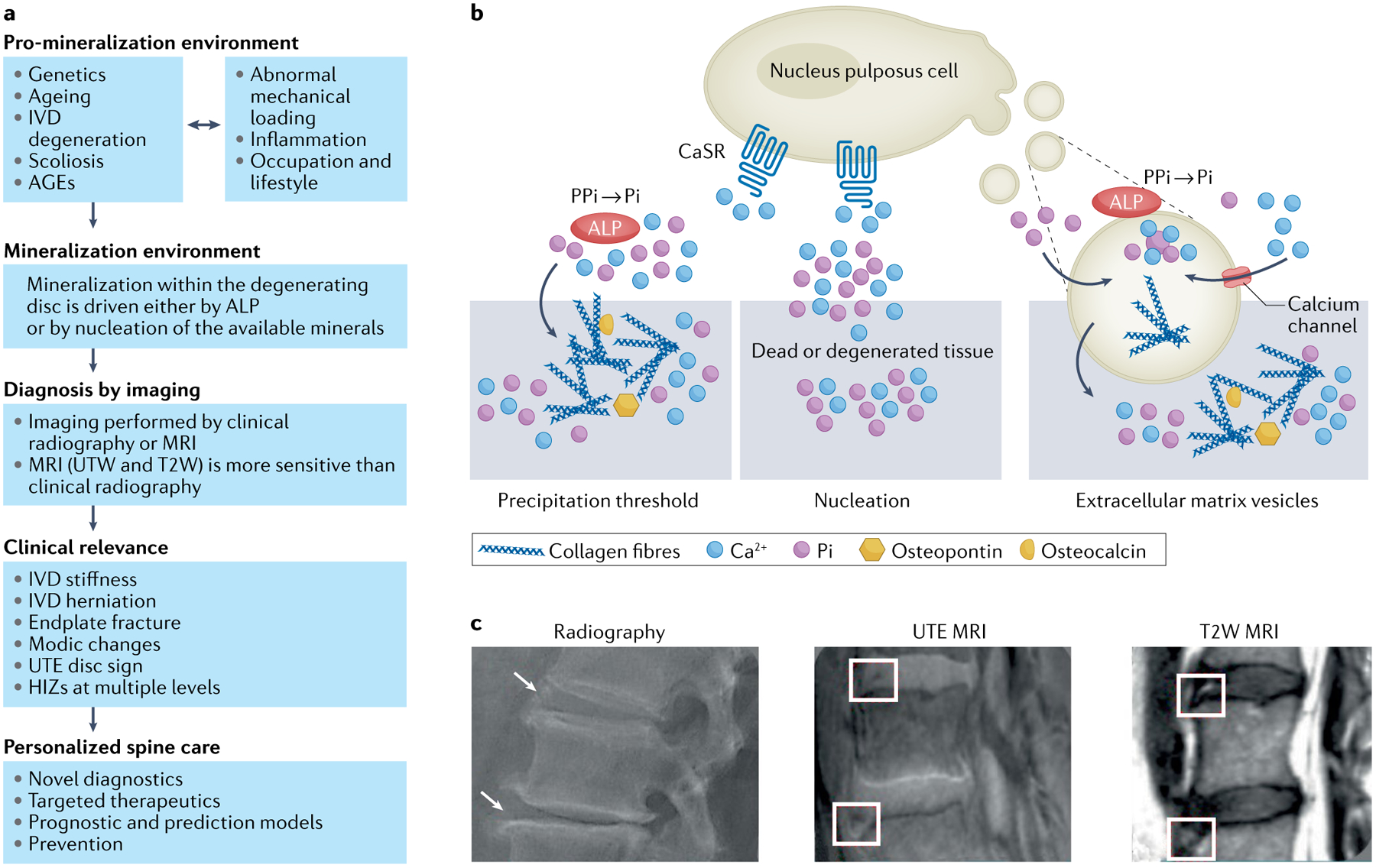

Regardless of the underlying cause, three mechanisms are believed to be involved in the initiation of calcification in IVDs88 (FIG. 4). One mechanism suggests that in order for calcification to occur, the calcium and inorganic monophosphate (Pi) ion product must reach the threshold of precipitation88, which requires Pi to accumulate by ALP activity. A second mechanism (nucleation) suggests that the calcium and Pi ion product can remain at physiological levels and nucleating agents are required to induce precipitation88. A third mechanism involves extracellular matrix vesicles, produced by budding from the cellular membrane of chondrocytes89 and found in the growth plate cartilage. Initially, it was thought that matrix vesicles initiate calcification90,91 because they are enriched with ALP, calcium and Pi92,93 and associated with collagen type X94, all of which are associated with calcification95. More recently, matrix vesicles have been shown to contain enriched populations of microRNA related to bone formation signalling pathways96 and have been suggested to share homology with exosomes97, which, according to the International Society of Extracellular Vesicles, should be termed ‘extracellular vesicles’. Extracellular vesicles mediate cell-to-cell communication, influence signalling pathways and as such might regulate endochondral bone formation and mineralization or calcification98. Many signalling pathways are implicated in mineralization99, but only a few of these have thus far demonstrated to also be related to IVD calcification.

Fig. 4 |. Disc calcification: mechanisms, diagnosis and clinical relevance.

a | Overview of disc calcification, diagnosis and clinical relevance. Mineralization within the degenerating disc has received increasing recognition as being important as the spinal phenotypes identified are associated with pain and disability. Disc mineralization deserves further attention in order to improve patient stratification by novel diagnostics to aid targeted therapeutics and even generate prognostic models to enable prevention of disc disease. b | The initiating factors and mechanisms of disc mineralization. Mineralization within the degenerating disc may involve three mechanisms. In one mechanism, calcium (Ca2+) and inorganic monophosphate (Pi) ions accumulate above physiological levels, reaching the threshold of precipitation; in this process alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity drives accumulation of Pi. In degenerated IVDs there is enhanced expression of calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR), which is involved in Ca2+ sensing and downstream signalling and as such may contribute to the process of intervertebral disc (IVD) calcification. In another mechanism, Ca2+ and Pi present even within physiological levels may precipitate owing to the presence of nucleating agents in dead or degenerated tissue. In a third mechanism, extracellular vesicles secreted by cells are enriched with Ca2+, Pi, and ALP and also contain biological messages (such as microRNAs) involved in bone-formation signalling pathways. Extracellular vesicle biology in the IVD is only beginning to emerge. c | Imaging methods for diagnosing disc mineralization. Mineralization within the intervertebral disc (shown by arrows and boxes) imaged with the aid of multiple imaging modalities, such as plain radiographs, ultra-short time-to-echo (UTE) MRI and T2-weighted MRI (T2W). AGEs, advanced glycation end products; HIZ, high-intensity zone on T2-weighted MRI; UDS, ultra-short time-to-echo disc sign.

The field of extracellular vesicles is only beginning to emerge within the spine community; proteomic analysis has indicated the presence of extracellular vesicles in healthy nucleus pulposus tissue100, and both notochordal cells101 and human degenerated nucleus pulposus cells102 have been shown to secrete extracellular vesicles. What the cargo of these extracellular vesicles is, how the cargo changes with degeneration of the IVD and how the cargo influences IVD calcification remain to be determined. Thus far, the prevailing thought is that IVD calcification is an accumulation of calcium salts103, initiated by ALP104. The substrates of ALP are not all fully known92,105, but among the myriad phosphate substrate suspects is inorganic pyrophosphate106,107, which is an inhibitor of apatite formation92. ALP can hydrolyse inorganic pyrophosphate to generate Pi ions, which are incorporated into the mineral crystals108 in the presence of calcium (Ca2+). Increasing the amount of Ca2+ is known to not only promote calcification in culture but also promote the terminal differentiation of chondrocytes and osteoblasts undergoing maturation109–111. Accumulation of calcium salts occurs normally in bone and growth plate but calcium can be deposited abnormally in blood vessels, articular cartilage, damaged tissue and IVD (cartilage endplate, nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus) using similar mechanisms103,109–112. However, whereas calcium transport and calcium signalling have been widely studied in bone cells, no studies have investigated calcium channels and pathways that regulate intracellular calcium in disc cells. IVD degeneration might provide appropriate calcification conditions through increased calcium and phosphate levels. In the course of IVD degeneration, the pH decreases further owing to raised lactic acid concentrations in the disc113. Once this pH decrease is sensed by the disc cells it can result in increased intracellular calcium concentrations. Furthermore, the increase in phosphate levels is thought to be a result of ALP activity, as discussed above92,104–107.

Interestingly, CaSR expressed on the cellular surface and on free calcium has also been implicated in the calcification process. This family C G protein coupled receptor is expressed in calcitropic tissues (such as the parathyroid glands and the kidneys) and non-calcitropic tissues and has multiple biological roles, alongside its main regulatory role in bone and mineral metabolism as a sensor of free calcium114. Patients with activating mutations of the extracellular CaSR often develop nephrocalcinosis and renal insufficiency with a high degree of ectopic calcifications early in life115. The development of OA has been observed in humans with such mutations, suggesting a link between CaSR activation and disease116. Similarly, in a guinea pig model of OA, CaSR was upregulated in articular cartilage and its activation accelerated degeneration and modulated the function of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β117. A gain-of-function CaSR mutation in mice led to ectopic calcification118.

No role for CaSR in the development or maintenance of other cartilaginous tissues, such as the IVD, has yet been shown, but investigators have hypothesized that an increase in local extracellular Ca2+ in the IVD microenvironment and activation of CaSR can promote degeneration of the cartilaginous endplate79. Ca2+ content was shown to increase in human CEP tissue whereas proteoglycan content decreased with the grade of IVD degeneration79, a finding in agreement with previous reports showing decreased proteoglycan and collagen content in CEP tissue from degenerated IVDs119,120. Increasing the levels of Ca2+ resulted in decreased secretion and accumulation of matrix molecules, such as collagens and proteoglycans, in cultured human CEP cells, through activation of CaSR79. Interestingly, aggrecan content, a major proteoglycan deposited in the CEP, was also reduced independently of CaSR activation as an increase in Ca2+ directly enhanced the activity of aggrecanases79. Finally, supplementing Ca2+ in IVD organ cultures was found to induce degeneration and enhance calcification of the CEP as well as decreasing glucose diffusion into the IVD79. Together, these findings indicate that extracellular CaSR and local levels of Ca2+ have key roles in pathological IVD calcification.

Clinical implications

Despite its close association with IVD degeneration, the clinical significance of IVD calcification remains unclear. Calcified IVDs are more likely to rupture and herniate than non-calcified IVDs either because calcification results in the production of an abnormal stress concentration that leads to fracture and fissures53 or because of spontaneous liquification (where the consistency of the calcified deposit changes and becomes more case-ous) and damage to the annulus fibrosus or surrounding soft tissues, with inflammatory responses that can further weaken tissues, and eventually result in IVD herniation121. Patients with calcified IVD herniations, or calcified IVD tissues identified on pathological examination following herniations, are usually more symptomatic and have larger herniations than those without calcification, often presenting a challenge to resect surgically, particularly when herniations are located in regions with narrowed spinal canals and/or when herniations are in the thoracic region122,123. Calcified herniated discs are associated with myelopathy and intradural extension and are often associated with poor surgical outcomes and postoperative complications such as bleeding, neurological deterioration, cerebrospinal fluid fistula and slow recovery124,125.

A few case reports have documented the possible role of IVD calcification in discogenic low back pain in adults126–128. Some of these cases also showed migration of calcified deposits inside the vertebral body suggesting the role of such deposits in disrupting weaker areas of the vertebral endplate causing marrow oedema126,127. The formation of a calcified hard-tissue inclusion in the bone disrupts the microarchitecture of the trabecular bone and leads to endplate fracture129. Endplate fracture is identifiable on MRI in the form of mostly type I and type II Modic changes (pathological subchondral bone marrow lesions); biomechanical studies have suggested that vertebral endplate microtrauma with the resultant marrow oedema correlates with type I Modic changes129 (FIG. 5). IVD calcification is clearly associated with the development of endplate fractures and potential Modic changes (types I and II), which are highly clinically relevant spinal phenotypes associated with pain and disability, but additional research is required. Using ultra-short time-to-echo (UTE) MRI, Zehra et al.10 found that the UTE disc sign (that is, a hyper-intense or hypo-intense IVD band) correlated highly with radiographic IVD calcification. Their earlier study reporting the presence of the UTE disc sign noted that the UTE disc sign showed a significant positive correlation with worse disability scores, suggesting that IVD calcification might have a role in discogenic low back pain130. Furthermore, the UTE disc sign was also significantly associated with Modic changes130. This finding further underlines the importance of IVD calcification or IVD stiffness (for example, fibrosis), which can affect stress and loading elements as well as IVD kinematics, and might have an implication for the development of Modic changes and perhaps with the further crosstalk that is noted between such lesions and the degenerating IVD (FIG. 5). The location of such IVD changes might be useful for predicting the development of endplate and vertebral marrow lesions. As with the role of calcification in IVD degeneration, these clinical findings support the concept that IVD calcification is likely to have a role in mechanical back pain (for example, a role in initiating and propagating herniation and/or instability) while also being mechanically modulated (for example, a role of mechanical overloading and IVD height loss inducing osteophyte formation and fusion in advanced degeneration)10.

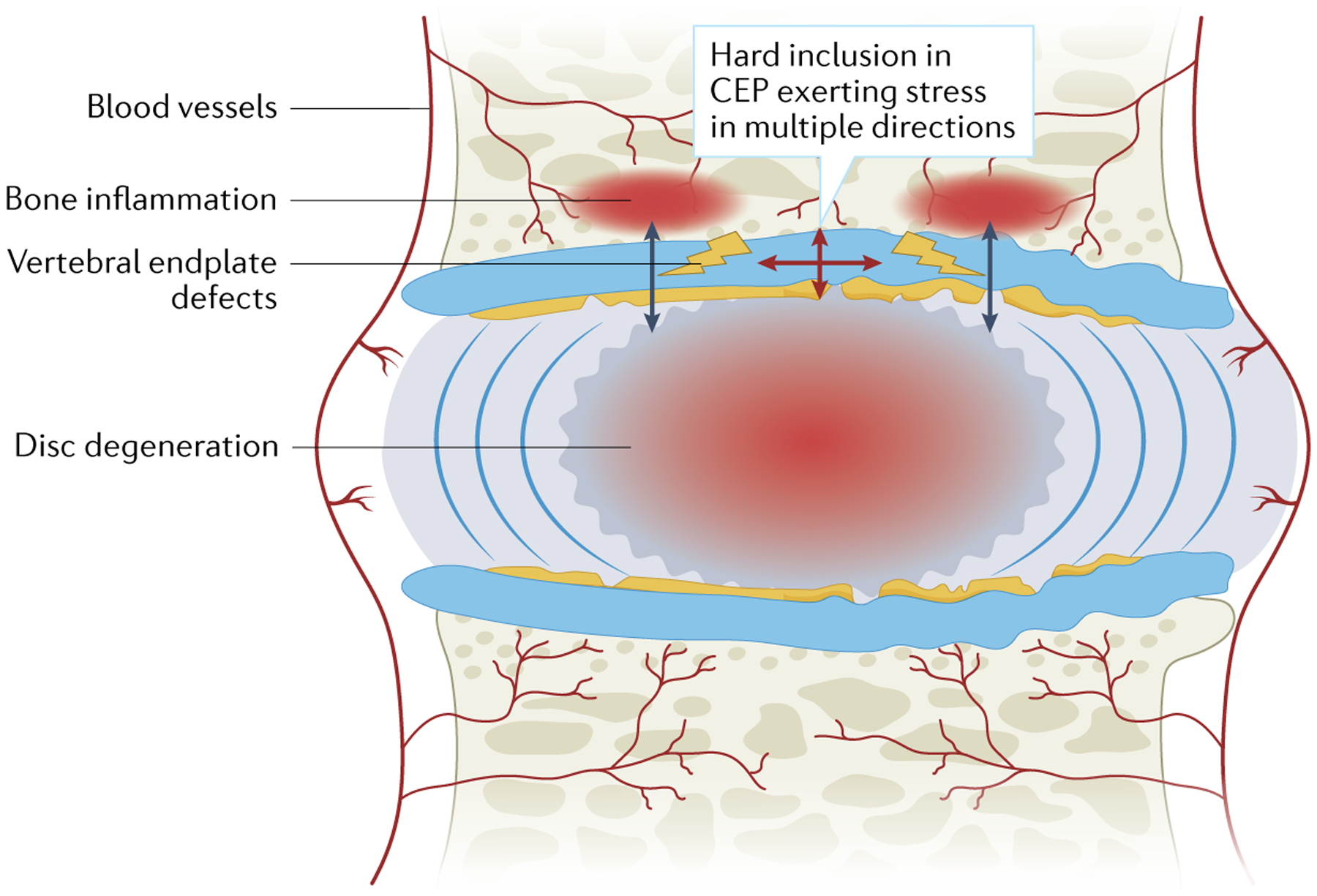

Fig. 5 |. A conceptual overview of the initiation of Modic changes and disc degeneration.

Hard inclusions in the cartilaginous endplate (CEP) can initiate cracks in multiple directions that can lead to vertebral endplate defects. A break in the endplate barrier would facilitate the escape of water, free movement of various cytokines and inflammatory cells and constant crosstalk between the disc and vertebral body, predisposing the disc to decompression, degeneration and Modic changes.

IVD calcification might have a direct role in contributing to the flexibility of the curve in spinal deformities such as AIS131. Curve flexibility is a factor that can predict the response to conservative treatment for curve correction (for example bracing) and surgical management of the curve in patients with AIS. For example, surgical intervention might be able to achieve a greater degree of curve correction in a more flexible spine curve versus a more rigid curve, with less instrumentation and shorter fusion levels. A more rigid curve might require more instrumentation and a greater number of levels fused to obtain a suitable degree of curve correction, increasing the risk of neurological complications and increasing health care costs associated with the addition of more screws as well as resulting in reduced preservation of motion segments132. Furthermore, IVD calcification might indeed be a predictor of an increased rate of curve progression in patients with AIS and of its secondary effects (for example, decreased lung function, truncal shift, back pain and gait abnormalities)133; however, future studies are needed to research these speculative ideas.

Emerging therapies

Studies using stem cells to treat degenerated IVDs in humans have failed to fully and consistently accomplish IVD rehydration or regeneration134,135. This lack of consistent findings might be because unique subphenotypes or endo-phenotypes of IVD calcification (stiffness and poor diffusion of nutrients) may affect the efficacy of such approaches. Furthermore, chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) results in growth plate-like chondrocytes rather than articular cartilage-like chondrocytes136. As such, MSC transplantation within a degenerated IVD that has active calcification processes might provide the ideal environment for hypertrophic differentiation and subsequent mineralization137. In line with this idea, cell leakage of MSCs implanted into degenerated rabbit IVDs was thought to be a cause of excess extradiscal calcifications138. However, these calcifications could even occur within the disc if the MSCs are injected into disc tissue137. As such, combinatory strategies that have the ability to modulate the MSC phenotype upon differentiation might help to minimize the risk of disc calcification caused by hypertrophic differentiation of the MSCs within the chondrogenic lineage. In a rabbit lumbar degeneration model, researchers injected nanofibrous spongy microspheres carrying MSCs that released anti-microRNA-199a; this system promoted the nucleus pulposus phenotype and resisted calcification in vitro and in a subcutaneous environment5. More attention to the topic of IVD calcification in the design of targeted therapeutic approaches and improved patient selection could result in a more personalized approach to spinal care.

Conclusions

Further work is needed to improve our understanding of the pathogenesis, manifestation and clinical relevance of IVD calcification and IVD ‘stiffness’. Advanced techniques, such as UTE and susceptibility-weighted MRI, should be explored in order to detect IVD calcification in routine clinical examinations and to map such changes in the IVD as well as to determine the capacity of such changes to predict specific phenotypes (for example, Modic changes and high-intensity zones). Susceptibility-weighted MRI has shown potential for imaging iron deposition, haemorrhages, microbleeds and calcification in the brain, liver, prostate and spinal cord; therefore, it is a potential tool for evaluating calcification in IVD139. As various spinal phenotypes (including IVD degeneration, IVD herniations, Modic changes, endplate abnormalities and facet joint changes) are known to result in pain, disability and altered spinal alignment, we must improve our understanding of the role of IVD calcification within this context. The possible role of IVD calcification on discogenic low back pain should also be evaluated to improve clinical and surgical outcomes. The clinical implications of IVD calcification inpatient selection for potential therapeutics for IVD regeneration or halting the degenerative process need to be explored. Furthermore, profiling IVDs that are susceptible to adjacent segment degeneration or disease in relation to a fusion or prosthetic IVD replacement has been a challenge with respect to risk stratification and outcome prediction140. The implications of IVD calcification at the adjacent IVD in this setting needs further exploration. Past studies addressing the genetics of IVD degeneration failed to find robust genes that can be replicated141. A confounding factor associated with the unique IVD phenotype of calcification might need to be identified and accounted for in such and any omics analyses. An extensive understanding of IVD calcification might further facilitate blood or refined imaging biomarker discovery. In addition, in the age of artificial intelligence, big data and precision spine care, detailed phenotyping of patients has taken centre stage142,143. In an effort to establish more robust clinical decision trees and algorithms, having a robust understanding of the disc calcification phenotype is imperative. Many funding agencies, such as the NIH in the USA, have initiated multi-centric, extremely well-funded and high-profile programmes (for example, BACPAC and Bridge2AI) that aim to provide high-quality datasets of extensively phenotyped patients in order to test algorithms and provide deep analytics to better understand the mechanisms of pain; these programmes are also aimed at developing more precise management protocols, predictive modelling and improved patient outcomes.

In summary, improved understanding of IVD calcification in both children and adults would enable more personalized and precise approaches to spinal conditions with respect to diagnosis, therapeutics and prognostic measures (FIG. 4a). Such understanding would also help to establish the role of calcification in other important bone-related and joint-related conditions, such as OA, in which the role of calcium crystals in the development and progression of disease might be clinically relevant.

Key points.

Intervertebral disc (IVD) calcification is associated with IVD degeneration and can lead to pain.

IVD calcification may affect disc kinematics and degeneration severity, and can also affect adjacent vertebral endplates, which might lead to pathological non-neoplastic subchondral bone marrow lesions (Modic changes).

Calcification in the IVD degenerative process is comparable with mineralization of the degenerative process of cartilaginous tissues in osteoarthritis.

IVD calcification is a unique phenotype that is clinically relevant, that could influence personalized approaches to patient care and that warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

D.S. is supported by institutional funding from the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at RUSH University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA. M.T. is supported by funding from the Dutch Arthritis Society (LLP22). F.M. is supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR). J.C.I. and S.I.-J. are supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the NIH under Award Number R01 AR 069315.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Francisco V et al. A new immunometabolic perspective of intervertebral disc degeneration. Nat. Rev. Rheum 18, 47–60 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samartzis D et al. A population-based study of juvenile disc degeneration and its association with overweight and obesity, low back pain, and diminished functional status. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am 93, 662–670 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams MA & Dolan P Intervertebral disc degeneration: evidence for two distinct phenotypes. J. Anat 221, 497–506 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckwalter JA Aging and degeneration of the human intervertebral disc. Spine 20, 1307–1314 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng G, Zhang Z, Dang M, Rambhia KJ & Ma PX Nanofibrous spongy microspheres to deliver rabbit mesenchymal stem cells and anti-miR-199a to regenerate nucleus pulposus and prevent calcification. Biomaterials 256, 120213 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutges JP et al. Hypertrophic differentiation and calcification during intervertebral disc degeneration. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 18, 1487–1595 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boos N, Nerlich AG, Wiest I, von der Mark K & Aebi M Immunolocalization of type X collagen in human lumbar intervertebral discs during ageing and degeneration. Histochem. Cell Biol 108, 471–480 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinbach LS Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate and calcium hydroxyapatite crystal deposition diseases: imaging perspectives. Radiol. Clin. North. Am 42, 185–205 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slouma M et al. Calcifying nucleopathy mimicking infectious spondylodiscitis. Acta Reumatol. Port 45, 61–64 (2020). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zehra U, Bow C, Cheung JP, Lu W & Samartzis D The association of lumbar intervertebral disc calcification on plain radiographs with the UTE Disc Sign on MRI. Eur. Spine J 27, 1049–1057 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samartzis et al. Novel diagnostic and prognostic methods for disc degeneration and low back pain. Spine J. 15, 1919–1932 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luk KD & Samartzis D Intervertebral disc “dysgeneration”. Spine J. 15, 1915–1918 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan I, Hargunani R & Saifuddin A The lumbar high-intensity zone: 20 years on. Clin. Radiol 69, 551–558 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito M et al. Predictive signs of discogenic lumbar pain on magnetic resonance imaging with discography correlation. Spine 23, 1252–1258 (1998). discussion 9–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iatridis JC, Nicoll SB, Michalek AJ, Walter BA & Gupta MS Role of biomechanics in intervertebral disc degeneration and regenerative therapies: what needs repairing in the disc and what are promising biomaterials for its repair? Spine J. 13, 243–262 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galbusera F et al. Ageing and degenerative changes of the intervertebral disc and their impact on spinal flexibility. Eur. Spine J 23, S324–S332 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niosi CA & Oxland TR Degenerative mechanics of the lumbar spine. Spine J. 4, 202s–208ss (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hristova GI et al. Calcification in human intervertebral disc degeneration and scoliosis. J. Orthop. Res. Soc 29, 1888–1895 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts S, Menage J & Eisenstein SM The cartilage end-plate and intervertebral disc in scoliosis: calcification and other sequelae. J. Orthop. Res. Soc 11, 747–757 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krzyzanowska AK et al. Activation of nuclear factor-kappa B by TNF promotes nucleus pulposus mineralization through inhibition of ANKH and ENPP1.2021. Sci. Rep 11, 8271 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinberger A & Myers AR Intervertebral disc calcification in adults: a review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum 8, 69–75 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandstrom C Calcifications of the intervertebral discs and the relationship between various types of calcifications in the soft tissues of the body. Acta Radiol. 36, 217–233 (1951). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chanchairujira K et al. Intervertebral disk calcification of the spine in an elderly population: radiographic prevalence, location, and distribution and correlation with spinal degeneration. Radiology 230, 499–503 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castriota-Scanderbeg A, Dallapiccola B Abnormal Skeletal Phenotypes: From Simple Signs to Complex Diagnoses (Springer, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sieroń D et al. Intervertebral disc calcification in children: case description and review of relevant literature. Pol. J. Radiol 78, 78–80 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahemad AM, Dasgupta B & Jagiasi J Intervertebral disc calcification in a child. Indian J. Orthop 42, 480–481 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizukawa K, Kobayashi T, Yamada N & Hirota T Intervertebral disc calcification with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Pediatr. Int 59, 622–624 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lernout C, Haas H, Rubio A & Griffet J Pediatric intervertebral disk calcification in childhood: three case reports and review of literature. Childs Nerv. Syst 25, 1019–1023 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coppa V et al. Pediatric intervertebral disc calcification: case series and systematic review of the literature. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 29, 590–598 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beluffi G, Fiori P & Sileo C Intervertebral disc calcifications in children. Radiol. Med 114, 331–341 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerlach R et al. Intervertebral disc calcification in childhood — a case report and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir. 143, 89–93 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dushnicky MJ, Okura H, Shroff M, Laxer RM & Kulkarni AV Pediatric idiopathic intervertebral disc calcification: single-center series and review of the literature. J. Pediatr 206, 212–216 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato S et al. The distinct role of the Runx proteins in chondrocyte differentiation and intervertebral disc degeneration: findings in murine models and in human disease. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 2764–2775 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haschtmann D, Ferguson SJ & Stoyanov JV B. M. P.−2. and TGF-beta3 do not prevent spontaneous degeneration in rabbit disc explants but induce ossification of the annulus fibrosus. Eur. Spine J 21, 1724–1733 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang G, Kang Y, Chen F & Wang B Cervical intervertebral disc calcification combined with ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament in an-11-year old girl: case report and review of literature. Childs Nerv. Syst 32, 381–386 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng XG et al. Radiological prevalence of lumbar intervertebral disc calcification in the elderly: an autopsy study. Skeletal Radiol. 25, 231–235 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chou CW Pathological studies on calcification of the intervertebral discs. Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi 56, 331–345 (1982). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bangert BA et al. Hyperintense disks on T1-weighted MR images: correlation with calcification. Radiology 195, 437–443 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tyrrell PN, Davies AM, Evans N & Jubb RW Signal changes in the intervertebral discs on MRI of the thoracolumbar spine in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin. Radiol 50, 377–383 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malghem J et al. High signal intensity of intervertebral calcified disks on T1-weighted MR images resulting from fat content. Skeletal Radiol. 34, 80–86 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blandino A, Longo M, Loria G, Gaeta M & Pandolfo I The fatty disc: an unusual cause of bright intervertebral disc on T1-weighted conventional spin-echo MR: a case report. J. Neuroradiol 10, 619–621 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stigen Ø, Ciasca T & Kolbjørnsen Ø Calcification of extruded intervertebral discs in dachshunds: a radiographic, computed tomographic and histopathological study of 25 cases. Acta Vet. Scand 61, 13 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shao J et al. Differences in calcification and osteogenic potential of herniated discs according to the severity of degeneration based on Pfirrmann grade: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord 17, 191 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karamouzian S et al. Frequency of lumbar intervertebral disc calcification and angiogenesis, and their correlation with clinical, surgical, and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Spine 35, 881–886 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takae R et al. Immunolocalization of bone morphogenetic protein and its receptors in degeneration of intervertebral disc. Spine 24, 1397–1401 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Z, Hutton WC & Yoon ST ISSLS Prize winner: effect of link protein peptide on human intervertebral disc cells. Spine 38, 1501–1507 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bach FC et al. Hedgehog proteins and parathyroid hormone-related protein are involved in intervertebral disc maturation, degeneration, and calcification. JOR Spine 2, e1071 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Girodias JB, Azouz EM & Marton D Intervertebral disk space calcification. A report of 51 children with a review of the literature. Pediatr. Radiol 21, 541–546 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bertram H et al. Accelerated intervertebral disc degeneration in scoliosis versus physiological ageing develops against a background of enhanced anabolic gene expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 342, 963–972 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akhtar S, Davies JR & Caterson B Ultrastructural immunolocalization of alpha-elastin and keratan sulfate proteoglycan in normal and scoliotic lumbar disc. Spine 30, 1762–1769 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meir A, McNally DS, Fairbank JC, Jones D & Urban JP The internal pressure and stress environment of the scoliotic intervertebral disc — a review. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H 222, 209–219 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Illien-Junger S et al. AGEs induce ectopic endochondral ossification in intervertebral discs. Eur. Cell Mater 32, 257–270 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iatridis JC & ap Gwynn I Mechanisms for mechanical damage in the intervertebral disc annulus fibrosus. J. Biomech 37, 1165–1175 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberts S, Urban JPG, Evans H & Eisenstein SM Transport properties of the human cartilage endplate in relation to its composition and calcification. Spine 21, 415–420 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benneker LM, Heini PF, Alini M, Anderson SE & Ito K 2004 Young investigator award winner: vertebral endplate marrow contact channel occlusions and intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine 30, 167–173 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zehra U, Robson-Brown K, Adams MA & Dolan P Porosity and thickness of the vertebral endplate depend on local mechanical loading. Spine 40, 1173–1180 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodriguez AG et al. Morphology of the human vertebral endplate. J. Orthop. Res 30, 280–287 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stokes IA & Iatridis JC Mechanical conditions that accelerate intervertebral disc degeneration: overload versus immobilization. Spine 29, 2724–2732 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Novais EJ et al. Comparison of inbred mouse strains shows diverse phenotypic outcomes of intervertebral disc aging. Aging Cell 19, e13148 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu J, Wu D, Guo K, Yuan F & Ran B OPN polymorphism is associated with the susceptibility to cervical spondylotic myelopathy and its outcome after anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion. Cell. Physiol. Biochem 34, 565–574 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gao SG et al. Elevated osteopontin level of synovial fluid and articular cartilage is associated with disease severity in knee osteoarthritis patients. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 18, 82–87 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mogensen MS et al. Genome-wide association study in Dachshund: identification of a major locus affecting intervertebral disc calcification. J. Hered 10.1093/jhered/esr021 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mogensen MS et al. Validation of genome-wide intervertebral disk calcification associations in dachshund and further investigation of the chromosome 12 susceptibility locus. Front Genet 10.3389/fgene.2012.00225 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang H & Trussell LO KCNQ5 channels control resting properties and release probability of a synapse. Nat. Neurosci 14, 840–847 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jensen VF, Beck S, Christensen KA & Arnbjerg J Quantification of the association between intervertebral disk calcification and disk herniation in Dachshunds. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc 233, 1090–1095 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rohdin C, Jeserevic J, Viitmaa R & Cizinauskas S Prevalence of radiographic detectable intervertebral disc calcifications in Dachshunds surgically treated for disc extrusion. Acta Vet. Scand 52, 24 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feinberg J, Boachie-Adjei O, Bullough PG & Boskey AL The distribution of calcific deposits in intervertebral discs of the lumbosacral spine. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 254, 303–310 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brodeur MR et al. Reduction of advanced-glycation end products levels and inhibition of RAGE signaling decreases rat vascular calcification induced by diabetes. PLoS One 9, e85922 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sellam J & Berenbaum F Is osteoarthritis a metabolic disease? Joint Bone Spine 80, 568–573 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Han Y et al. Oxidative damage induces apoptosis and promotes calcification in disc cartilage endplate cell through ROS/MAPK/NF-κB pathway: implications for disc degeneration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 516, 1026–1032 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Illien-Junger S et al. Chronic ingestion of advanced glycation end products induces degenerative spinal changes and hypertrophy in aging pre-diabetic mice. PLoS One 10, e0116625 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Illien-Junger S et al. Combined anti-inflammatory and anti-AGE drug treatments have a protective effect on intervertebral discs in mice with diabetes. PLoS One 8, e64302 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bessueille L & Magne D Inflammation: a culprit for vascular calcification in atherosclerosis and diabetes. Cell Mol. Life Sci 72, 2475–2489 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Joshi FR et al. Does vascular calcification accelerate inflammation? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 67, 69–78 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Raggi P Inflammation and calcification: the chicken or the hen? Atherosclerosis 238, 173–174 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ikeda K et al. Macrophages play a unique role in the plaque calcification by enhancing the osteogenic signals exerted by vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 425, 39–44 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Peng B et al. The pathogenesis of discogenic low back pain. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br 87, 62–67 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saifuddin A, Mitchell R & Taylor BA Extradural inflammation associated with annular tears: demonstration with gadolinium-enhanced lumbar spine MRI. Eur. Spine J 8, 34–39 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grant MP et al. Human cartilaginous endplate degeneration is induced by calcium and the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor in the intervertebral disc. Eur. Cell Mater 32, 137–151 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Canaff L & Hendy GN Calcium-sensing receptor gene transcription is up-regulated by the proinflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1β. Role of the NF-κB pathway and κB elements. J. Biol. Chem 280, 14177–14188 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shao J, Yu M, Jiang L, Wu F & Liu X Sequencing and bioinformatics analysis of the differentially expressed genes in herniated discs with or without calcification. Int. J. Mol. Med 39, 81–90 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zehra U et al. Spinopelvic alignment predicts disc calcification, displacement, and Modic changes: evidence of an evolutionary etiology for clinically-relevant spinal phenotypes. JOR Spine 3, e1083 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Du G et al. Abnormal mechanical loading induces cartilage degeneration by accelerating meniscus hypertrophy and mineralization after ACL injuries in vivo. Am. J. Sports Med 44, 652–663 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roberts S, Bains MA, Kwan A, Menage J & Eisenstein SM Type X collagen in the human invertebral disc: an indication of repair or remodelling? Histochem. J 30, 89–95 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shen G The role of type X collagen in facilitating and regulating endochondral ossification of articular cartilage. Orthod. Craniofac. Res 8, 11–17 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jin L et al. Annulus fibrosus cell characteristics are a potential source of intervertebral disc pathogenesis. PLoS One 9, e96519 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Feng G et al. Multipotential differentiation of human anulus fibrosus cells: an in vitro study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am 92, 675–685 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hsu HH Mechanisms of initiating calcification. ATP-stimulated Ca- and Pi-depositing activity of isolated matrix vesicles. Int. J. Biochem 26, 1351–1356 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ornoy A & Langer Y Scanning electron microscopy studies on the origin and structure of matrix vesicles in epiphyseal cartilage from young rats. Isr. J. Med. Sci 14, 745–752 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Anderson HC Mechanism of mineral formation in bone. Lab. Invest 60, 320–330 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wuthier RE et al. Mechanism of matrix vesicle calcification: characterization of ion channels and the nucleational core of growth plate vesicles. Bone Miner. 17, 290–295 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Balcerzak M et al. The roles of annexins and alkaline phosphatase in mineralization process. Acta Biochim. Pol 50, 1019–1038 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ali SY, Sajdera SW & Anderson HC Isolation and characterization of calcifying matrix vesicles from epiphyseal cartilage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 67, 1513–1520 (1970). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wu LN, Genge BR, Lloyd GC & Wuthier RE Collagen-binding proteins in collagenase-released matrix vesicles from cartilage. Interaction between matrix vesicle proteins and different types of collagen. J. Biol. Chem 266, 1195–1203 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bonucci E Comments on the ultrastructural morphology of the calcification process: an attempt to reconcile matrix vesicles, collagen fibrils, and crystal ghosts. Bone Miner. 17, 219–222 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lin Z et al. Selective enrichment of microRNAs in extracellular matrix vesicles produced by growth plate chondrocytes. Bone 88, 47–55 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shapiro IM, Landis WJ & Risbud MV Matrix vesicles: are they anchored exosomes? Bone 79, 29–36 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Qin Y, Sun R, Wu C, Wang L & Zhang C Exosome: a novel approach to stimulate bone regeneration through regulation of osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci 17, 712 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cui Y, Luan J, Li H, Zhou X & Han J Exosomes derived from mineralizing osteoblasts promote ST2 cell osteogenic differentiation by alteration of microRNA expression. FEBS Lett. 590, 185–192 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bach FC et al. Soluble and pelletable factors in porcine, canine and human notochordal cell-conditioned medium: implications for IVD regeneration. Eur. Cell Mater 32, 163–180 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bach F et al. Notochordal-cell derived extracellular vesicles exert regenerative effects on canine and human nucleus pulposus cells. Oncotarget 8, 88845–88856 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lu K et al. Exosomes as potential alternatives to stem cell therapy for intervertebral disc degeneration: in-vitro study on exosomes in interaction of nucleus pulposus cells and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther 8, 108 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Christoffersen J & Landis WJ A contribution with review to the description of mineralization of bone and other calcified tissues in vivo. Anat. Rec 230, 435–450 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Miller GJ & DeMarzo AM Ultrastructural localization of matrix vesicles and alkaline phosphatase in the Swarm rat chondrosarcoma: their role in cartilage calcification. Bone 9, 235–241 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Borras T & Comes N Evidence for a calcification process in the trabecular meshwork. Exp. Eye Res 88, 738–746 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim EE & Wyckoff HW Reaction mechanism of alkaline phosphatase based on crystal structures. Two-metal ion catalysis. J. Mol. Biol 218, 449–464 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Narisawa S, Frohlander N & Millan JL Inactivation of two mouse alkaline phosphatase genes and establishment of a model of infantile hypophosphatasia. Dev. Dyn 208, 432–446 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Anderson HC et al. Impaired calcification around matrix vesicles of growth plate and bone in alkaline phosphatase-deficient mice. Am. J. Pathol 164, 841–847 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chang W et al. Calcium sensing in cultured chondrogenic RCJ3.1C5.18 cells. Endocrinology 140, 1911–1919 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rodriguez L, Cheng Z, Chen TH, Tu C & Chang W Extracellular calcium and parathyroid hormone-related peptide signaling modulate the pace of growth plate chondrocyte differentiation. Endocrinology 146, 4597–4608 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dvorak MM et al. Physiological changes in extracellular calcium concentration directly control osteoblast function in the absence of calciotropic hormones. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 5140–5145 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yuan FL et al. Apoptotic bodies from endplate chondrocytes enhance the oxidative stress-induced mineralization by regulating PPi metabolism. J. Cell. Mol. Med 23, 3665–3675 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ohshima H & Urban JP The effect of lactate and pH on proteoglycan and protein synthesis rates in the intervertebral disc. Spine 17, 1079–1082 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hannan FM, Kallay E, Chang W, Brandi ML & Thakker RV The calcium-sensing receptor in physiology and in calcitropic and noncalcitropic diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 15, 33–51 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Brown EM Role of the calcium-sensing receptor in extracellular calcium homeostasis. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 27, 333–343 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Stock JL et al. Autosomal dominant hypoparathyroidism associated with short stature and premature osteoarthritis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 84, 3036–3040 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Burton DW et al. Chondrocyte calcium-sensing receptor expression is up-regulated in early guinea pig knee osteoarthritis and modulates PTHrP, MMP-13, and TIMP-3 expression. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 13, 395–404 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hough TA et al. Activating calcium-sensing receptor mutation in the mouse is associated with cataracts and ectopic calcification. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 13566–13571 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Fields AJ, Rodriguez D, Gary KN, Liebenberg EC & Lotz JC Influence of biochemical composition on endplate cartilage tensile properties in the human lumbar spine. J. Orthop. Res 32, 245–252 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rodriguez AG et al. Human disc nucleus properties and vertebral endplate permeability. Spine 36, 512–520 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yue B et al. Thoracic intervertebral disc calcification and herniation in adults: a report of two cases. Eur. Spine J 25, 118–123 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Choi JW et al. Transdural approach for calcified central disc herniations of the upper lumbar spine. Technical note. J. Neurosurg. Spine 7, 370–374 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Dabo X et al. The clinical results of percutaneous endoscopic interlaminar discectomy (PEID) in the treatment of calcified lumbar disc herniation: a case-control study. Pain Phys. 19, 69–76 (2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Court C, Mansour E & Bouthors C Thoracic disc herniation: surgical treatment. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res 104, S31–S40 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yu L et al. Removal of calcified lumbar disc herniation with endoscopic-matched ultrasonic osteotome — our preliminary experience. Br. J. Neurosurg 34, 80–85 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Nogueira-Barbosa MH, da Silva Herrero CF, Pasqualini W & Defino HL Calcific discitis in an adult patient with intravertebral migration and spontaneous remission. Skeletal Radiol. 42, 1161–1164 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rodacki MA, Castro CE & Castro DS Diffuse vertebral body edema due to calcified intraspongious disk herniation. Neuroradiology 47, 316–321 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Azizaddini S, Arefanian S, Redjal N, Walcott BP & Mollahoseini R Adult acute calcific discitis confined to the nucleus pulposus in the cervical spine: case report. J. Neurosurg. Spine 19, 170–173 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Crockett MT, Kelly BS, van Baarsel S & Kavanagh EC Modic type 1 vertebral endplate changes: injury, inflammation, or infection? Am. J. Roentgenol 209, 167–170 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pang H et al. The UTE Disc Sign on MRI: a novel imaging biomarker associated with degenerative spine changes, low back pain and disability. Spine 43, 503–511 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Eyvazov K et al. The association of lumbar curve magnitude and spinal range of motion in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a cross-sectional study. 2017. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord 18, 51 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Samartzis D et al. Selection of fusion levels using the fulcrum bending radiograph for the management of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients with alternate level pedicle screw strategy: clinical decision-making and outcomes. PLoS One 10, e0120302 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Yao G et al. Characterization and predictive value of segmental curve flexibility in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients. Spine 42, 1622–1628 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Yoshikawa T, Ueda Y, Miyazaki K, Koizumi M & Takakura Y Disc regeneration therapy using marrow mesenchymal cell transplantation: a report of two case studies. Spine 35, E475–E480 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Orozco L et al. Intervertebral disc repair by autologous mesenchymal bone marrow cells: a pilot study. Transplantation 92, 822–828 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.van Gool SA et al. Fetal mesenchymal stromal cells differentiating towards chondrocytes acquire a gene expression profile resembling human growth plate cartilage. PLoS One 7, e44561 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Vickers L, Thorpe AA, Snuggs J, Sammon C & Le Maitre CL Mesenchymal stem cell therapies for intervertebral disc degeneration: Consideration of the degenerate niche. JOR Spine 2, e1055 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Vadala G et al. Mesenchymal stem cells injection in degenerated intervertebral disc: cell leakage may induce osteophyte formation. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med 6, 348–355 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Liu S et al. Susceptibility weighted imaging: current status and future directions. NMR Biomed. 10.1002/nbm.3552 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Saavedra-Pozo FM, Deusdara RA & Benzel EC Adjacent segment disease perspective and review of the literature. Ochsner J. 14, 78–83 (2014). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Eskola PJ et al. Genetic association studies in lumbar disc degeneration: a systematic review. PLoS One 7, e49995 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Mallow GM et al. Intelligence-based spine care model: a new era of research and clinical decision-making. Glob. Spine J 11, 135–145 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Samartzis D et al. Precision spine care: a new era of discovery, innovation, and global impact. Glob. Spine J 8, 321–322 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]