Abstract

Nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (NAMPT) is considered as a promising target for cancer therapy given its critical engagement in cancer metabolism and inflammation. However, therapeutic benefit of NAMPT enzymatic inhibitors appears very limited, likely due to the failure to intervene non-enzymatic functions of NAMPT. Herein, we show that NAMPT dampens antitumor immunity by promoting the expansion of tumor infiltrating myeloid derived suppressive cells (MDSCs) via a mechanism independent of its enzymatic activity. Using proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) technology, PROTAC A7 is identified as a potent and selective degrader of NAMPT, which degrades intracellular NAMPT (iNAMPT) via the ubiquitin–proteasome system, and in turn decreases the secretion of extracellular NAMPT (eNAMPT), the major player of the non-enzymatic activity of NAMPT. In vivo, PROTAC A7 efficiently degrades NAMPT, inhibits tumor infiltrating MDSCs, and boosts antitumor efficacy. Of note, the anticancer activity of PROTAC A7 is superior to NAMPT enzymatic inhibitors that fail to achieve the same impact on MDSCs. Together, our findings uncover the new role of enzymatically-independent function of NAMPT in remodeling the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, and reports the first NAMPT PROTAC A7 that is able to block the pro-tumor function of both iNAMPT and eNAMPT, pointing out a new direction for the development of NAMPT-targeted therapies.

KEY WORDS: NAMPT, Non-enzymatic function, eNAMPT, Cancer, MDSC, PROTAC, Tumor immunity, Immunotherapy

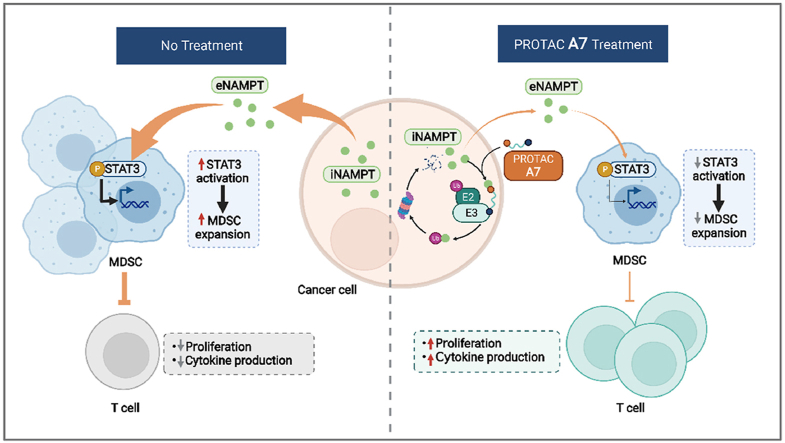

Graphical abstract

eNAMPT secreted from tumor cells suppresses antitumor immunity by promoting the expansion of tumor infiltrating MDSCs. NAMPT-specific PROTAC A7 directly degrades intracellular NAMPT, which in turn downregulates eNAMPT and promotes antitumor immunity.

1. Introduction

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), an indispensable redox carrier in energy metabolism and essential co-substrate for various enzymes (e.g., poly ADP-ribose polymerase, sirtuins, CD38, etc.), plays a fundamental role in multiple cellular processes1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Rather than being generated de novo, in most mammalian cells, NAD+ is predominantly produced via the reusing of nicotinamide (NAM) liberated from NAD+-utilizing enzymes, known as the salvage pathway, in which NAMPT is the rate-limiting enzyme6. In this process, NAMPT catalyzes NAM into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), subsequently catalyzed into NAD+ by nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyl transferase (NMNAT)6.

NAMPT is overexpressed in various types of cancer cells to satisfy the continuous replenishment of NAD+ required for fast proliferation7,8. Beyond being an intracellular enzyme, NAMPT could also be secreted out of the cells, known as extracellular NAMPT (eNAMPT)9. eNAMPT is known to function as a cytokine-like protein independent of its enzymatic activity. eNAMPT promotes the proliferation, epithelial–mesenchymal transition and migration of tumor cells10, modulates angiogenesis11,12 and remodels tumor immune microenvironment13, all of which are engaged in tumor progression. In fact, serum eNAMPT levels were shown to correlate with the prognosis of cancer patients14,15.

Targeting NAMPT has emerged as a promising antitumor strategy. A few NAMPT inhibitors (such as FK866 and CHS828) that impair the enzymatic activity of NAMPT have entered clinical trials for cancer therapy16, yet none of them is able to progress to later stages owing to the limited anti-tumor efficacy17,18. One possible reason is that the inhibition of NAMPT enzymatic activity may not be sufficient to fully impair the oncogenic function of NAMPT. Currently, there lacks a pharmacological approach to intervene the non-enzymatic activity of NAMPT, in which eNAMPT is a major player9.

Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) have emerged as a promising technology for chemical knockdown of target proteins, which consist of three components: a target protein-binding moiety, a degradation machinery recruiting unit, and a linker region that couples these two functionalities. Typically, the utilized degradation machinery involves the recruitment of an E3 ubiquitin ligase followed by the ubiquitination of the target protein and its subsequent degradation by the proteasome via the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS). Once the target protein is eliminated, PROTACs are released and recycled. Compared with classic enzymatic inhibitors, PROTACs exhibit an advantage in disrupting both enzymatic and non-enzymatic activities of NAMPT.

This study discovered that tumor-derived NAMPT dampens antitumor immunity by facilitating the expansion of myeloid derived suppressive cells (MDSCs), which appears mainly mediated by the non-enzymatic activity of eNAMPT. Further, PROTAC A7, the first PROTAC of NAMPT, was rationally designed, which was proved to efficiently decrease both iNAMPT and eNAMPT and in turn boost potent antitumor immunity. These findings provide mechanistic insights into NAMPT-mediated interplay of cancer cell and immune cells via its non-enzymatic activity, and identified PROTAC A7 as an applicable approach to intervene the non-enzymatic activity of NAMPT to revive antitumor immunity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. In vitro NAMPT inhibition assay

All of the enzymatic reaction involved a 50 μL mixture containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 12.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 20 μmol/L nicotinamide, 0.4 mmol/L phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate, 2 mmol/L ATP, 30 μg/mL of alcohol dehydrogenase, 10 μg/mL of NAMPT, 1.5% alcohol, 1 mmol/L DTT, 0.02% BSA, 0.01% Tween 20 and the test compounds. Fluorescence intensity was measured at an excitation of 360 nm and an emission of 460 nm. The data were analyzed using Graphpad Prism. the fluorescent intensity (Ft) achieved in the absence of the compound was defined as 100% activity. The fluorescent intensity (Fb) in the absence of NAMPT was defined as 0% activity. The activity of each compound was calculated according to the following equation Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where F is the fluorescent intensity achieved in the presence of the compound.

2.2. Cell proliferation assay

For sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay, cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 103–5 × 103 cells per well for overnight and then treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or FK866 as indicated for 72 h. The culture medium was aspirated, and 10% trichloroacetic acid was added into the wells for fixation. Then, the precipitated proteins were stained with 0.4% (w/v) SRB in acetic acid solution 1% (v/v) for 15 min at room temperature, followed by fully washing with 1% acetic acid and then dried. The adherent SRB was solubilised in 10 mmol/L Tris buffer and the absorbance was read at a wavelength of 560 nm for calculation of cell viability inhibition rate.

For live cell imaging, cell plates were put into the cell incubator of Incucyte Live-Cell Analysis System (Essen Bioscience), images were captured every 6 h for 4 consecutive days, and the cell growth curves were generated.

2.3. Intracellular NAD+ measurement

Cells were seeded in 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104/well. After starvation for 12 h with serum-free cell medium culture, compounds at different concentrations were added. After 24 h, every well was added of 1 mol/L HClO4 and the mixture was kept for 30 min on ice and then centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Then, 40 μL of the supernatants were neutralized with 16 μL of 1 mol/L K2CO3 and maintained for 20 min on ice. The mixtures were centrifuged at 18,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min, then 10 μL of the supernatants were added to 100 μL reaction buffer containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 3% ethanol, 1.66 mmol/L phenazineethosulfate, 90 μg/mL alcohol dehydrogenase, 0.42 mmol/L 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide. After incubating at 37 °C for 40 min, the absorbance at 570 nm was read.

2.4. Immunoblot analysis

In iNAMPT degradation assay, cells were seeded in 6-well plate at a density of 1 × 106/well. Compounds at different concentrations were added for 24 h. After washed with PBS, cells were lysed with 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Equal amounts of total protein were separated via SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Then they were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes and then blocked with Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20 (TBST) containing 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 2 h. The membranes were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. After washed with TBST for three times, the membranes were incubated with the secondary antibody for 1 h. After washed with TBST for three times, the membranes were visualized by Odyssey Infrared Imaging.

In eNAMPT degradation assay, cells were seeded in 10-cm dish at a density of 3 × 105 cells/mL. After incubation with A7 for 24 h, cells were refreshed with serum-free medium containing A7 for another 24 h. Proteins in the supernatant were precipitated by 2% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. After washed with acetone for two times, the sediment was dissolved with 2% SDS and used for immunoblot analysis.

2.5. Syngeneic tumor mouse models

MC38 (2 × 105) or CT26 (2 × 105) cells were subcutaneously injected into the flank of syngeneic female C57BL/6 (5–8 weeks of age), BALB/c nude (5–8 weeks of age) or BALB/c mice (5–8 weeks of age), respectively. Mice were treated with MS7, A7 or vehicle control when tumors reached 80–100 mm3 in size. Tumor growth was monitored by the measurement of tumor size using Eq. (2):

| (2) |

Tumor volumes and body weights were monitored every 2 days during the course of treatment. Mice were sacrificed until the tumor volume reached approximately 2000 mm3, and tumors were removed and analyzed. The experiments were approved and performed according to the Institute Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica (Shanghai, China) or the Committee on Ethics of Medicine, Navy Medical University (Shanghai, China). During all the studies, the care and use of animals were conducted in accordance with the regulations of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC).

2.6. Generation of cell lines stably interfering Nampt using shRNA

ShRNA expressing pLKO.1 vector was introduced into CT26 or MC38 cell lines by lentiviral infection according to a standard protocol. Briefly, HEK293T cells were seeded in 6-well plate to 80% confluence and transfected with 4 μg of lentiviral DNA consisting of 2 μg shRNA expressing pLKO.1 plasmid, 1.6 μg psPAX2 packaging plasmid and 0.4 μg pMD2.G envelope plasmid. Viral supernatant was collected at 48–72 h and added to targeted cells containing 8 μg/mL polybrene. Forty-eight hours post infection, cells were selected using puromycin for at least one week.

2.7. In vitro myeloid derived suppressive cells (MDSCs) differentiation assay

MDSCs were generated in vitro by co-culture of MC38 tumor cells with isolated bone marrow cells via the Liechtenstein method. Briefly, 4 × 105 bone marrow cells were isolated from the femurs of mice and cultured in the bottom of 6-well plates in the presence of 2 × 105 MC38 cells placed in Transwell inserts and grown for 6 days. On Day 3, compounds A7, D1, or DMSO vehicle alone was added to the co-culture system. Bone marrow cells cultured alone in the presence of DMSO vehicle (without MC38 cells or compounds treatment) were run in parallel as a negative MDSC induction control. All cultures were supplemented with 10 ng/mL granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF, Pepro Tech). On Day 6, the Transwells were removed and cells in the basal chamber were isolated, washed, and then stained for the indicated surface markers for subsequent flow cytometry analysis.

2.8. Flow cytometry analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells

CT26 cells stably transfected with shNAMPT and shNC were subcutaneously injected into the flank of syngeneic female BALB/c mice (5–8 weeks of age). Cell numbers were adjusted (1 × 106 for shNAMPT and 2 × 105 for shNC) to ensure the comparable tumor sizes between the two groups, hence minimizing the influence of tumor volume difference. For isolation of tumor-infiltrating immune cells from CT26 xenograft, tumor-bearing mice were euthanized and tumors were cut into pieces and digested in RPMI 1640 media containing 0.1% Type IV collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corporation) and 0.01% DNase I (Roche) at 37 °C for 45 min. Single cells were collected and passed through a 70 μm strainer and followed by lysis of red blood cells.

For flow cytometry, single cells were incubated with Fc blocker (BD Biosciences) on ice for 15 min to prevent non-specific binding. Cells were then washed and stained for surface markers in antibody mixture on ice for 30 min. For intracellular staining, cells were incubated at complete culture medium containing 1 × Cell Stimulation Cocktail (Invitrogen) for 4 h in 37 °C 5% CO2 incubator, followed by staining for surface markers. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized and stained for intracellular molecules. For analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in MC38 xenograft, MC38 cells stably transfected with sh-NAMPT (2 × 105) and sh-NC (2 × 105) were subcutaneously injected into the flank of syngeneic female C57BL/6 (5–8 weeks of age). Isolation and surface markers’ staining of tumor-infiltrating immune cells were aforementioned in analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in CT26 xenograft.

2.9. Cellular thermal shift assay (CESTA)

A2780 cells (1 × 107) were collected, and washed twice with PBS. After resuspended with 1 mL PBS, three freeze–thaw cycles were taken to lyse cells. Cell lysate was then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was divided into aliquots incubated with A7 at the indicated concentrations for 30 min at 37 °C. After a heat shock at the indicated temperature for 3 min, samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to spin down the sediment. The supernatant was collected and used for immunoblot analysis.

2.10. Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Culture medium of MC38 cells was centrifuged at 11,000 × g, 4 °C for 5 min and the supernatant was collected. NAMPT ELISA Kit (AdipoGen Life Sciences) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.11. Statistics

Data were expressed as means ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple-comparisons test post hoc or Student's t test as appropriate. Log-rank test was conducted for survival analysis. Differences were considered to be statistically.

2.12. RNA-sequencing analysis

Total RNA was isolated from A2780 cells treated with or without PROTAC A7 (10 nmol/L, 24 h). The RNA-sequencing analysis was performed by Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI, Beijing, China). Gene fold change and adjusted P-value between control and A7 groups were obtained using Deseq2. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) analysis were performed using ClusterProfiler on R 4.0.2.

2.13. Proteomic analysis

All the proteins were collected from A2780 cells treated with different compounds (10 nmol/L, 24 h). The proteomic analysis was performed by the Proteomics Platform of Core Facility of Basic Medical Science, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (STJU-SM, Shanghai, China). Before difference analysis, sample correlation, principal component analysis (PCA) and supervised partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) were used to reject the outliers. Volcano map was used to visualize the difference proteins.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. NAMPT promotes the expansion of MDSCs independent of its enzymatic activity

Sporadic evidence suggested that NAMPT could be secreted from tumor cells9,13,14,19, 20, 21. eNAMPT is a key mediator of the non-enzymatic activity of NAMPT, mostly known for its cytokine-like activity in immune modulation22,23. To investigate the therapeutic potential of inhibiting the non-enzymatic activity of NAMPT, we first screened a small panel of cancer cells to identify cells with high eNAMPT secretion. In this study, murine cancer cells were particularly selected for allowing the immunotherapeutic assessment in immune competent mouse models in the following experiments. In fact, eNAMPT was detectable in the culture medium of the most cell lines, though at a variable level that appeared irrelevant to the level of iNAMPT. Among these cells, MC38 exhibited the highest level of eNAMPT, followed by CT26 cells (Fig. 1A). Meanwhile, both cell lines did not show the apparent growth dependency on the enzymatic activity of NAMPT, as examined by exposing to a well-validated NAMPT enzymatic inhibitor FK866 (Supporting Information Fig. S1A). These data indicate that CT26 and MC38 cells might be suitable research models for understanding the non-enzymatic activity of NAMPT, in particular the immune-modulatory activity.

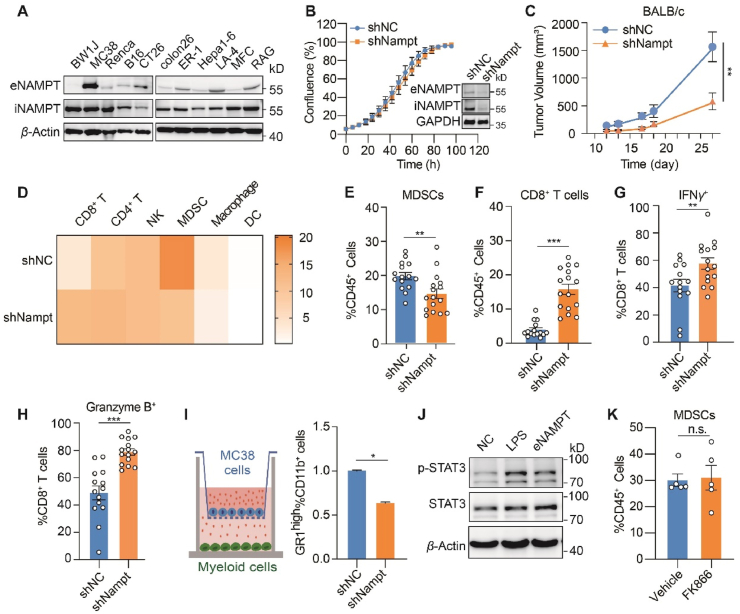

Figure 1.

NAMPT promotes the expansion of MDSCs independent of its enzymatic activity. (A) Immunoblot analysis of iNAMPT (intracellular NAMPT) and eNAMPT (extracellular NAMPT). (B) Cell growth of CT26 cells with stable knockdown of NAMPT. Left, CT26 scramble control (shNC) or shNAMPT cell confluency assessed by incuCyte proliferation assay; Right, immunoblot analysis of NAMPT. (C) Tumor growth curve. CT26 shNC control or shNAMPT cells were inoculated subcutaneously in BALB/c mice (n = 10). (D–H) Tumor infiltrating immune cells analyzed by flow cytometry. CT26 shNC control or shNAMPT cells were inoculated subcutaneously in BALB/c mice (n = 15). (D) Heatmap showing the proportion of the indicated immune cells in tumor infiltrating CD45+ cells. (E) MDSCs; (F) CD8+ T cells; (G) IFNγ+ CD8+ T cells; (H) Granzyme B+ CD8+ T cells. (I) In vitro MDSC differentiation assay. Left, the schematic illustration of co-culture experiment. MC38 scramble control (shNC) or shNAMPT cells were co-cultured with mice bone marrow. Right, normalized counts of GR1high CD11b+ cells analyzed by flow cytometry. (J) Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling change in MDSCs. MDSCs from murine bone marrow were treated with recombinant NAMPT (200 ng) for 2 h and immunoblotting analysis was performed. (K) Proportion of MDSCs in tumor infiltrating CD45+ cells. CT26 tumor-bearing mice were treated with vehicle control or FK866 (16 mg/kg, daily) for 5 days (n = 5). All data depict mean ± SEM. n.s., not significant. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Next, NAMPT was depleted using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) in both CT26 and MC38 cells, which effectively downregulated both iNAMPT and eNAMPT (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1B). Stable knockdown of NAMPT, despite the apparent decrease of intracellular NAD+ level, barely affected the cell growth in vitro (Fig. 1B, Fig. S1B and S1C). However, when the CT26 cell pair were implanted into immune competent mice, knockdown of NAMPT dramatically decreased the tumor volume (Fig. 1C). In parallel, the difference was much more modest in immune-deficient nude mice (Fig. S1D).

Our results suggest that NAMPT might be involved in promoting the immunosuppressive tumor environment. As such, the tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were analyzed to examine the alteration of tumor immunity in CT26 tumors with or without NAMPT depletion. Among lymphocytic cell populations, the ratio of infiltrating MDSCs, an immunosuppressive cell population, was mostly affected by NAMPT knockdown (Fig. 1D and E). Meanwhile, infiltrating CD8+ T cells, the major antitumor effector cells in the tumor microenvironment, was increased (Fig. 1D and F). In NAMPT-depleted tumors, the cytotoxic CD8+ T cells exhibited augmented functions, as indicated by enhanced expression of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and granzyme B (Fig. 1G and H), indicating the stimulated tumor immunity by NAMPT depletion. We also analyzed TILs in MC38 tumors. The significant reduction of infiltrating MDSCs was similarly observed upon NAMPT depletion, while the increase of CD8+ T cells were relatively modest (Fig. S1E).

It has been well-documented that MDSCs inhibit the antitumor immunity by preventing T cells infiltration and blocking T cells function24. We hypothesized that the promoted antitumor immunity was likely due to the modulation of MDSCs by NAMPT, which in turn affected T cells. To test this possibility, mouse bone marrow was co-cultured with MC38 scramble control (shNC) or NAMPT stably-depleted cells (shNAMPT). MC38 cells with stable knockdown of NAMPT significantly inhibited the differentiation of MDSCs compared with the control group (Fig. 1I). To test whether the impact on MDSCs were mediated by eNAMPT, the recombinant NAMPT protein that mimics eNAMPT in the tumor microenvironment was directly added to MDSC culture and signaling alteration in MDSCs was examined. We discovered that the recombinant NAMPT could activate Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK–STAT3) signaling in MDSCs without affecting mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling (Fig. 1J and Fig. S1F), both playing important roles in regulating MDSC expansion22,25. We further asked whether the NAMPT catalytic activity was required for its impact on MDSCs. To this end, mice bearing CT26 tumors were treated with FK866. In contrast to NAMPT depletion, FK866 treatment did not affect the infiltrating MDSCs in CT26 tumors (Fig. 1K). These results suggest that tumor-intrinsic NAMPT facilitates MDSCs expansion to suppress the antitumor immunity, which is likely attributed to the non-enzymatic activity of eNAMPT.

3.2. Rational design and synthesis of NAMPT degrading PROTACs

The results above inspired us that the intervention of NAMPT-mediated non-enzymatic effects would be a promising antitumor strategy. To this end, we took the PROTACs approach that aims to recruit the cellular proteolysis apparatus to degrade target proteins and directly regulate the content of target proteins in cells26 (Fig. 2A). NAMPT-specific PROTACs exhibit an advantage to block the activity of eNAMPT, both enzymatic and non-enzymatic activity, via NAMPT degradation (Fig. 2B). Our previous studies identified MS7 as a potent NAMPT inhibitor through high-throughput screening and structure-based drug design27. As the docking models show, the terminal hydrophobic phenyl group of MS7, which extended to the solvent-exposed area, was dispensable for its interaction with NAMPT (Fig. 2C), suggesting that it was a suitable site for modification to acquire PROTACs. We then took an approach of the widely-used Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL)-based PROTAC technology and synthesized NAMPT PROTAC candidates by introducing a carboxyl group at the para, meta and ortho positions of the phenyl group of MS7 and conjugating them to an E3 ubiquitin ligase ligand targeting VHL through aliphatic linkers (Fig. 2D).

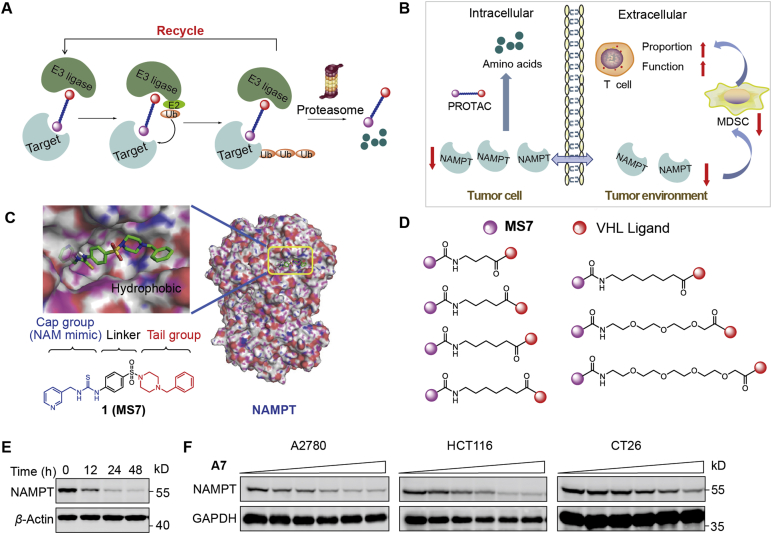

Figure 2.

The rational design of NAMPT-specific proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs). (A) The action mode of PROTACs via the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS). (B) The expected action of PROTACs on tumor cells and the tumor environment. (C) The chemical structure of MS7 and its predicted binding mode to NAMPT (PDB ID: 2GVJ). (D) The linkers of NAMPT-specific PROTACs. (E) Time-dependent NAMPT degradation. CT26 cells were treated with A7 (1 μmol/L) at different timepoints. (F) Dose-dependent degradation of NAMPT. A2780, HCT-116 or CT26 cells were treated with A7 at gradient concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.05, 0.2, 1, and 5 μmol/L) for 24 h.

The synthetic routes of candidates A1–5, B1–5 and C1–5 are shown in Supporting Information Scheme S1. Detailed procedures and reaction conditions are described in Supporting methods. Supporting structure identification spectra are provided as well. The reaction of compound 2 and tert-butyl piperazine-1-carboxylate under basic conditions afforded intermediate 3. After the reduction in the nitro group under a H2 atmosphere via the catalysis of Pd/C, intermediate 4 was obtained. Then, the addition of di(1H-imidazole-1-yl) methanethione thiourea and subsequent pyridin-3-ylmethanamine provided the thiourea intermediate 6. After the removal of the Boc protecting group with trifluoroacetic acid, intermediate 7 was afforded. Then, substituted methyl(bromomethyl)benzoate was added to give esters, which were converted to corresponding acids 8a–c under basic conditions. The amidation of compounds 8a–c with protected and substituted carboxylic acids and the subsequent hydrolysis afforded intermediates 9a–o. Then, target compounds A1–5, B1–5 and C1–5 were obtained by the amidation of compounds 9a–o and the VHL ligand, which was obtained according to the literature28.

As shown in Supporting Information Scheme S2, compounds 10a and 10b were synthesized according to the literature29. Amidation between the VHL ligand and intermediate 11a or 11b followed by reduction under H2 atmosphere gave intermediates 12a and 12b, which were then reacted with compound 8 through amidation to give target compounds A6 and A7.

We next evaluated NAMPT degradation efficacy of the designed PROTAC candidates. In addition to CT26 murine cancer cell line, we also included two human cancer cell lines, ovarian cancer A2780 and colon cancer HCT-116, to ensure that the discovered compounds was able to degrade both human and murine NAMPT. PROTACs with either meta (B1–5) or ortho (C1–5) position substitutions showed little NAMPT degradation capability (Supporting Information Fig. S2C–S2F). Among the PROTACs with para position substitutions, PROTAC A7 rather than compounds A1–6 (Fig. S2A and S2B) was able to decrease NAMPT protein level in cancer cells. This result suggests that the introduction of a longer hydrophilic linker at para position would facilitate the degradation efficacy of NAMPT. PROTAC A7 was then selected for further studies. A7 effectively degraded NAMPT in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2E and F). The efficiency of PROTAC A7 in NAMPT degradation was variable between the different cancer cells (Fig. S2G), probably due to the different genetic background between cells, causing the difference in capacity of drug efflux, drug metabolism, or the activity of the protein degradation system in the cells30.

3.3. PROTAC A7 is a potent and selective degrader of NAMPT

We next investigated the mechanism of action of A7 in degrading NAMPT in cancer cells. CESTA confirmed that compound A7 could bind both NAMPT and VHL proteins in cancer cells (Fig. 3A). Consistently, both MS7 and the VHL ligand largely rescued A7-mediated degradation of NAMPT, likely due to the competition with A7 for binding to NAMPT or VHL (Fig. 3B). To further confirm the mechanism of A7, its analog D1 that does not possess the binding affinity to VHL28, and E1 that is unable to bind NAMPT17, were designed as negative controls (Fig. 3C, Supporting Information Schemes S3 and S4). As expected, neither D1 nor E1 showed capability in degrading NAMPT (Fig. 3D), highlighting the requirement of simultaneous binding of PROTAC A7 to NAMPT and VHL for its degrading activity. Moreover, combinational treatment of MS7 and VHL ligand failed to impact NAMPT expression as well, excluding the contribution of their additive effect (Fig. 3D).

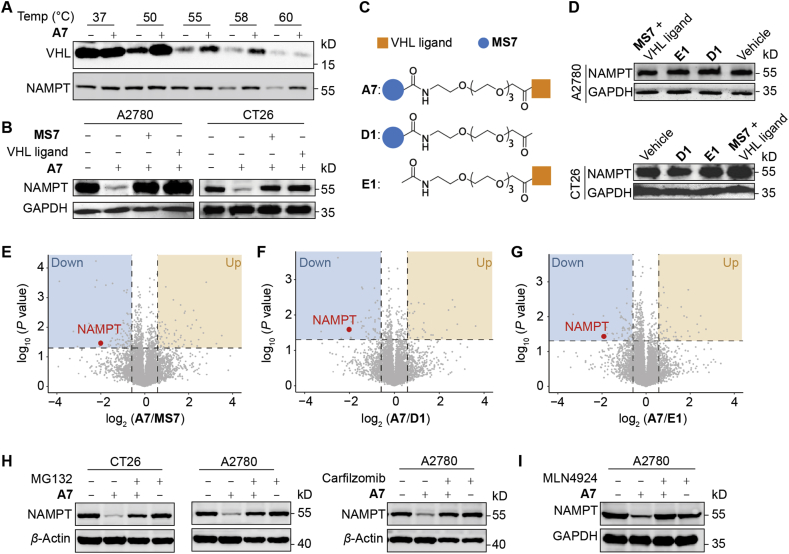

Figure 3.

PROTAC A7 is a potent and selective degrader of NAMPT. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of thermal shift assay in A2780 cell lysate treated with or without A7. (B) The expression level of NAMPT in A2780 or CT26 cells treated with the combination of A7 and MS7 or Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) ligand for 24 h. (C) The design of negative controls D1 and E1. (D) The expression level of NAMPT in A2780 or CT26 cells treated with negative controls or the combination of MS7 or VHL ligand for 24 h. (E–G) The proteomic analysis of A2780 cells. Cells were treated with A7 (10 nmol/L, 24 h) or with MS7, D1, E1 as negative controls. Proteomic analysis was performed to compare the protein level change between A7 and the indicated control treated group. (H) The impact of protease inhibition on A7-caused NAMPT degradation. CT26 or A2780 cells were treated with A7 (1 μmol/L) with or without protease inhibitor MG132 (1 μmol/L) or carfilzomib (200 nmol/L) for 24 h. (I) The impact of E3 inhibition on A7-caused NAMPT degradation. A2780 cells were treated with A7 (1 μmol/L) with or without a neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 (500 nmol/L) for 24 h.

Next, proteomic analysis was performed to confirm the selectivity of A7. A2780 cells were treated with A7 or MS7. Comparison of the global protein level change between A7 and MS7 treatment highlighted the selective downregulation of NAMPT protein by A7 (Fig. 3E, Supporting Information Fig. S3A and S3B). Similar results were obtained by comparing A7 treatment with that with D1 (Fig. 3F) or E1 (Fig. 3G).

Further, we tested whether A7 degraded NAMPT via the ubiquitin (Ub)–proteasome system (UPS). The proteasome inhibitors MG13231 and carfilzomib28 were co-treated with compound A7. Blockage of UPS largely abolished A7-mediated NAMPT degradation (Fig. 3H). Likewise, MLN4924, a neddylation inhibitor deactivating the cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase32, also restored the intracellular NAMPT level in the presence of A7 treatment (Fig. 3I). In these results, it was noted that inhibition of proteasome alone for up to 24 h did not affect NAMPT protein level. To understand this result, protein stability of iNAMPT was examined in the presence of cycloheximide to block protein synthesis. In agreement with our results, NAMPT protein level was barely changed (Fig. S3C), suggesting a relatively inactive turnover of NAMPT. In contrast, PROTAC A7-enforced degradation of NAMPT was almost completely restored by proteasome inhibition. Altogether, our results identified PROTAC A7 as a potent and selective degrader of NAMPT via the UPS pathway.

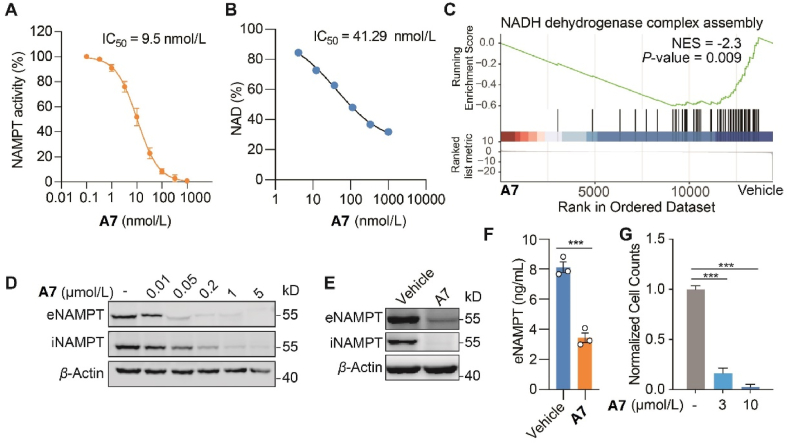

3.4. PROTAC A7 decreases intracellular NAD+ and extracellular NAMPT

Further, the impact of PROTAC A7 on NAMPT activity, both the enzymatic and non-enzymatic activities, were assessed. PROTAC A7 exhibited potent inhibitory effect against the enzymatic activity NAMPT, with an IC50 of 9.5 nmol/L (Fig. 4A). Consistently, intracellular NAD+ was dose-dependently decreased in both CT26 cells (Fig. 4B) and A2780 cells (Supporting Information Fig. S4A) upon A7 treatment. Further RNAseq analysis followed GSEA demonstrated a significant enrichment of mitochondrial electron transport pathway (Fig. S4B), especially the NADH dehydrogenase complex assembly upon A7 treatment (Fig. 4C), possibly acting as a cellular attempt to recover the diminished NAD+ level. Importantly, with the degradation of NAMPT, the secretion of eNAMPT was concomitantly decreased in response to PROTAC A7, as shown by immunoblotting for NAMPT in CT26 cells and MC38 cells (Fig. 4D and E), as well as ELISA measurement for secreted NAMPT in the culture medium (Fig. 4F). Accordingly, we discovered that A7 significantly inhibited the expansion of MDSCs as assessed by the in vitro MDSCs differentiation assay (Fig. 4G). Altogether, these results suggested that A7 could inhibit both the NAMPT enzymatic activity and eNAMPT secretion, and the latter might account for the suppression of expansion of MDSCs.

Figure 4.

PROTAC A7 decreases intracellular NAD+ and extracellular NAMPT. (A) The inhibitory activity of compound A7 against the catalytic activity of NAMPT. (B) Intracellular NAD+ level in CT26 cells treated with PROTAC A7. (C) The enrichment of NADH dehydrogenase complex assembly pathway in A7-treated cells. CT26 cells were treated with A7 (100 nmol/L, 24 h), followed by RNA-seq and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) analysis. (D, E) Immunoblot analysis for eNAMPT and iNAMPT. CT26 (D) or MC38 (E) cells were treated with A7 at the indicated concentrations for 24 h and then refreshed in serum-free medium for extra 24 h. Cell lysates and proteins in the supernatant were collected for immunoblotting analysis of iNAMPT and eNAMPT respectively. MC38 cells were treated with A7 (1 μmol/L). (F) Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assessment of eNAMPT. MC38 cells were treated as in (E). (G) The normalized MDSCs counts. Bone marrow cells were co-cultured with MC38 tumor cells, treated as indicated for 7 consecutive days. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

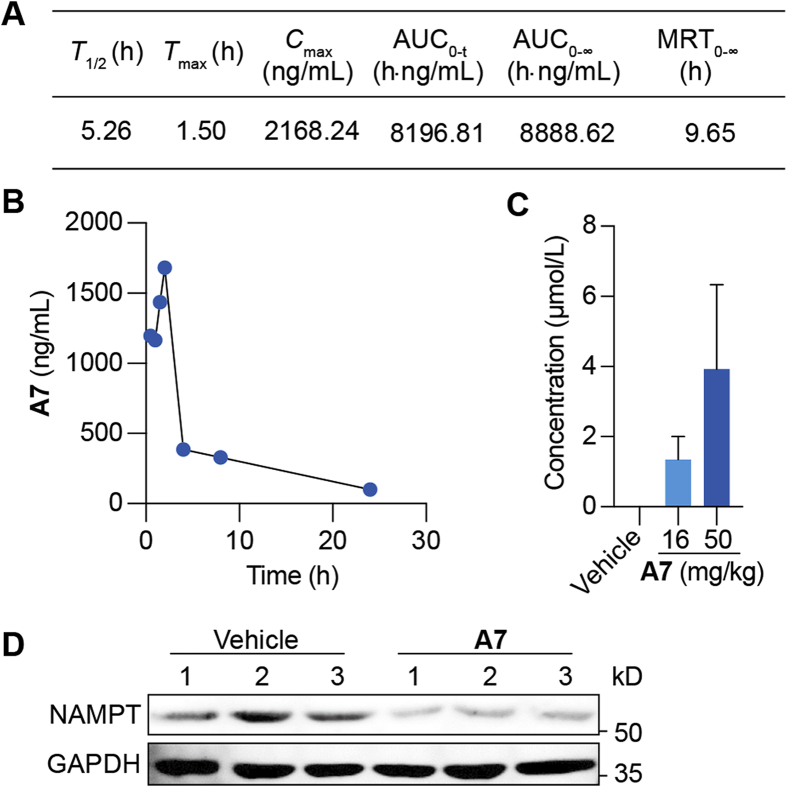

3.5. PROTAC A7 efficiently degrades NAMPT in tumor tissues in vivo

It remains unclear whether PROTAC A7 could degrade NAMPT in vivo. To this end, pharmacokinetic (PK) studies were performed in C57BL/6 mice. After intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration at 50 mg/kg, the concentrations of PROTAC A7 in plasma were detected (Fig. 5A and B). The half-life of A7 was approximately 5.26 h and the peak concentration was 2168 ng/mL. Despite its relatively large size (MW = 1184), PROTAC A7 could be effectively absorbed and achieved a sufficient plasma exposure in mice, with the area under the curve (AUC) value of 8196.81 h·ng/mL. Moreover, upon administration for 7 consecutive days, intratumoral A7 concentration was sufficient to reach the DC50 for NAMPT degradation in vitro (Fig. 5C). In parallel, immunoblot for CT26 tumor tissues confirmed the degradation of NAMPT upon A7 treatment (Fig. 5D). These data together validated that PROTAC A7 is metabolically stable in vivo and could reach proper concentrations in tumor tissues, where it degrades NAMPT efficiently.

Figure 5.

PROTAC A7 efficiently degrades tumoral NAMPT in vivo. (A) The pharmacokinetic parameters of A7. C57BL/6 mice were administrated with single dose of PROTAC A7 (50 mg/kg, i.p.), followed by the collection of plasma. (B) The concentrations of A7 in plasma at the indicated time points. Mice were treated as in (A). (C) The intratumoral concentration of PROTAC A7. CT26 tumor-bearing mice were treated with PROTAC A7 (16 or 50 mg/kg) for 7 consecutive days (n = 3). (D) Immunoblotting analysis for NAMPT in CT26 tumor tissue. Mice were treated as in (C).

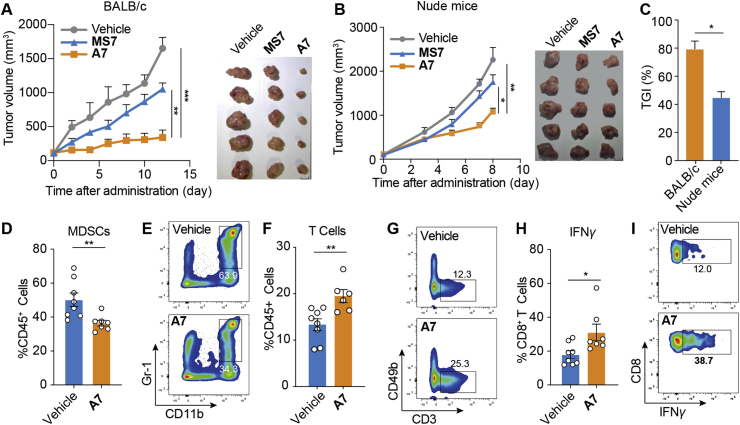

3.6. PROTAC A7 inhibits MDSCs expansion and revives antitumor immunity

We next asked whether PROTAC A7 could boost antitumor immunity for cancer therapy. In fact, with the negligible toxicity (Supporting Information Fig. S5A and S5B), PROTAC A7 significantly suppressed CT26 tumor growth in immune competent mice (Fig. 6A), whereas the efficacy was much weaker in immune-deficient mice (Fig. 6B and C), suggesting the contribution of A7-mediated antitumor immunity. In addition, the tumor-inhibiting effect of PROTAC A7 was superior to that of MS7 (Fig. 6A), highlighting the benefit of non-enzymatic intervention to therapeutic efficacy. In parallel, analysis of TILs showed that PROTAC A7 concurrently decreased the infiltration of MDSCs (Fig. 6D, E and Fig. S5C) and increased the proportion of T cells (Fig. 6F, G and Fig. S5C), consistent with the effect of NAMPT knockdown. Moreover, T cell functions were significantly augmented upon A7 treatment, as indicated by the enhanced expression of IFN-γ in CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6H and I), showing an enhancement of antitumor immunity. All these data together show that PROTAC A7 efficiently revived antitumor immunity by inhibiting the infiltration of MDSCs.

Figure 6.

PROTAC A7 inhibits tumor infiltrating MDSCs and revives antitumor immunity. (A) Tumor growth curve (left) and tumor images at endpoint (right). CT26 tumor bearing BALB/c mice were treated with PROTAC A7 (16 mg/kg, i.p.), MS7 (16 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle for 12 consecutive days (n = 5). Scale bar = 1 cm. (B) Tumor growth curve (left) and tumor images at endpoint (right). CT26 tumor bearing nude mice were treated as in (A) (n = 5). Scale bar = 1 cm. (C) Tumor growth inhibition (TGI) rate at the endpoint of (A) and (B). (D–I) CT26 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice were treated as in (A) for 7 consecutive days (n = 7 or 8). (D, E) The proportion and the representative staining of MDSCs in tumor infiltrating CD45+ cells. (F, G) The proportion and the representative staining of T cells in tumor infiltrating CD45+ cells. (H, I) The proportion and the representative staining of IFNγ+ cells in tumor infiltrating CD8+ T cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrate that tumor cell-derived NAMPT promotes the expansion of MDSCs, thus dampening the T cell-mediated antitumor immunity likely via an enzymatic activity independent function. We also reported the first PROTAC that degrades iNAMPT and diminishes eNAMPT secretion, thus blocking both enzymatic and non-enzymatic function of NAMPT. PROTAC A7 exhibits superior efficacy to reported NAMPT enzymatic inhibitors in syngeneic mice tumor models. Together, our findings provide PROTAC A7 as an applicable approach for both enzymatic and non-enzymatic NAMPT intervention, informing new therapeutic strategies in cancer immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 82030105 to Chunquan Sheng; 91957126 to Min Huang), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant 2020YFA0509100 to Chunquan Sheng).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2021.12.017.

Contributor Information

Guoqiang Dong, Email: dgq-81@163.com.

Min Huang, Email: mhuang@simm.ac.cn.

Chunquan Sheng, Email: shengcq@smmu.edu.cn.

Author contributions

Guoqiang Dong, Min Huang, Chunquan Sheng conceived the study, designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Ying Wu and Congying Pu conducted the experiments and prepared the manuscript. Yixian Fu assisted in conducting experiments and preparing the manuscript. All authors have approved the final article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Cohen M.S. Interplay between compartmentalized NAD+ synthesis and consumption: a focus on the PARP family. Genes Dev. 2020;34:254–262. doi: 10.1101/gad.335109.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang N., Sauve A.A. Regulatory effects of NAD+ metabolic pathways on sirtuin activity. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2018;154:71–104. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Covarrubias A.J., Kale A., Perrone R., Lopez-Dominguez J.A., Pisco A.O., Kasler H.G., et al. Senescent cells promote tissue NAD+ decline during ageing via the activation of CD38+ macrophages. Nat Metab. 2020;2:1265–1283. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-00305-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houtkooper R.H., Cantó C., Wanders R.J., Auwerx J. The secret life of NAD+: an old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocr Rev. 2010;31:194–223. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sultani G., Samsudeen A.F., Osborne B., Turner N. NAD+: a key metabolic regulator with great therapeutic potential. J Neuroendocrinol. 2017;29:e12508. doi: 10.1111/jne.12508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Revollo J.R., Grimm A.A., Imai S. The NAD biosynthesis pathway mediated by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase regulates Sir2 activity in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50754–50763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408388200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucena-Cacace A., Otero-Albiol D., Jiménez-García M.P., Muñoz-Galvan S., Carnero A. NAMPT is a potent oncogene in colon cancer progression that modulates cancer stem cell properties and resistance to therapy through Sirt1 and PARP. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:1202–1215. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharif T., Ahn D.G., Liu R.Z., Pringle E., Martell E., Dai C., et al. The NAD+ salvage pathway modulates cancer cell viability via p73. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:669–680. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grolla A.A., Travelli C., Genazzani A.A., Sethi J.K. Extracellular nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, a new cancer metabokine. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:2182–2194. doi: 10.1111/bph.13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torretta S., Colombo G., Travelli C., Boumya S., Lim D., Genazzani A.A., et al. The cytokine nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (eNAMPT; PBEF; Visfatin) acts as a natural antagonist of C–C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) Cells. 2020;9:496. doi: 10.3390/cells9020496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adya R., Tan B.K., Chen J., Randeva H.S. Pre-B cell colony enhancing factor (PBEF)/visfatin induces secretion of MCP-1 in human endothelial cells: role in visfatin-induced angiogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adya R., Tan B.K., Punn A., Chen J., Randeva H.S. Visfatin induces human endothelial VEGF and MMP-2/9 production via MAPK and PI3K/Akt signalling pathways: novel insights into visfatin-induced angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78:356–365. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carbone F., Liberale L., Bonaventura A., Vecchiè A., Casula M., Cea M., et al. Regulation and function of extracellular nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase/visfatin. Compr Physiol. 2017;7:603–621. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c160029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H., Bai E., Zhang Y., Jia Z., He S., Fu J. Role of Nampt and visceral adiposity in esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma. J Immunol Res. 2017;2017:3970605. doi: 10.1155/2017/3970605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karampela I., Christodoulatos G.S., Kandri E., Antonakos G., Vogiatzakis E., Dimopoulos G., et al. Circulating eNampt and resistin as a proinflammatory duet predicting independently mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: a prospective observational study. Cytokine. 2019;119:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galli U., Colombo G., Travelli C., Tron G.C., Genazzani A.A., Grolla A.A. Recent advances in NAMPT inhibitors: a novel immunotherapic strategy. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:656. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galli U., Travelli C., Massarotti A., Fakhfouri G., Rahimian R., Tron G.C., et al. Medicinal chemistry of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2013;56:6279–6296. doi: 10.1021/jm4001049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korotchkina L., Kazyulkin D., Komarov P.G., Polinsky A., Andrianova E.L., Joshi S., et al. OT-82, a novel anticancer drug candidate that targets the strong dependence of hematological malignancies on NAD biosynthesis. Leukemia. 2020;34:1828–1839. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0692-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grolla A.A., Torretta S., Gnemmi I., Amoruso A., Orsomando G., Gatti M., et al. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT/PBEF/visfatin) is a tumoural cytokine released from melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2015;28:718–729. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garten A., Petzold S., Barnikol-Oettler A., Körner A., Thasler W.E., Kratzsch J., et al. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT/PBEF/visfatin) is constitutively released from human hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun B.L., Sun X., Casanova N., Garcia A.N., Oita R., Algotar A.M., et al. Role of secreted extracellular nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (eNAMPT) in prostate cancer progression: novel biomarker and therapeutic target. EBioMedicine. 2020;61:103059. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y., Zhang Y., Dorweiler B., Cui D., Wang T., Woo C.W., et al. Extracellular Nampt promotes macrophage survival via a nonenzymatic interleukin-6/STAT3 signaling mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34833–34843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805866200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Audrito V., Serra S., Brusa D., Mazzola F., Arruga F., Vaisitti T., et al. Extracellular nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) promotes M2 macrophage polarization in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:111–123. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-589069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hegde S., Leader A.M., Merad M. MDSC: markers, development, states, and unaddressed complexity. Immunity. 2021;54:875–884. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aghaeepour N., Kin C., Ganio E.A., Jensen K.P., Gaudilliere D.K., Tingle M., et al. Deep immune profiling of an arginine-enriched nutritional intervention in patients undergoing surgery. J Immunol. 2017;199:2171–2180. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou Y., Ma D., Wang Y. The PROTAC technology in drug development. Cell Biochem Funct. 2019;37:21–30. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu T.Y., Zhang S.L., Dong G.Q., Liu X.Z., Wang X., Lv X.Q., et al. Discovery and characterization of novel small-molecule inhibitors targeting nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10043. doi: 10.1038/srep10043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raina K., Lu J., Qian Y., Altieri M., Gordon D., Rossi A.M., et al. PROTAC-induced BET protein degradation as a therapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:7124–7129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521738113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J., Li H., Zou G., Wang L.X. Novel template-assembled oligosaccharide clusters as epitope mimics for HIV-neutralizing antibody 2G12. Design, synthesis, and antibody binding study. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:1529–1540. doi: 10.1039/b702961f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X., He Y., Zhang P., Budamagunta V., Lv D., Thummuri D., et al. Discovery of IAP-recruiting BCL-XL PROTACs as potent degraders across multiple cancer cell lines. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;199:112397. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun Y., Zhao X., Ding N., Gao H., Wu Y., Yang Y., et al. PROTAC-induced BTK degradation as a novel therapy for mutated BTK C481S induced ibrutinib-resistant B-cell malignancies. Cell Res. 2018;28:779–781. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0055-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Y., Morgan M.A., Sun Y. Targeting neddylation pathways to inactivate cullin-RING ligases for anticancer therapy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21:2383–2400. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.