Abstract

Objective

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, informal caregivers’ mental health deteriorated more than that of non-caregivers. We examined the association between increased caregiver burden during the pandemic and severe psychological distress (SPD).

Methods

We used cross-sectional data from a nationwide internet survey conducted between August and September 2020 in Japan. Of 25,482 participants aged 15–79 years, 1,920 informal caregivers were included. SPD was defined as Kessler 6 Scale (K6) score ≥ 13. Self-rated change in caregiver burden was measured retrospectively with a single question item. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association between SPD and increased caregiver burden during the pandemic, adjusted for demographic, socioeconomic, health, and caregiving variables. To examine the differential association between increased caregiver burden and SPD, interaction terms were added and binary logistic regression was separately conducted for all variables.

Results

Participants’ mean age was 52.3 years (standard deviation 15.9), 48.8% of participants were male, 56.7% reported increased caregiver burden, and 19.3% exhibited SPD. Increased caregiver burden was significantly associated with SPD (adjusted odds ratio: 1.90; 95% confidence interval: 1.37–2.66). The association between increased caregiver burden and SPD was stronger among caregivers who were married, those undergoing disease treatment, and those with a care-receiver with a care need level of 1–2.

Conclusions

The results revealed that more than half of caregivers reported increased caregiver burden, and increased caregiver burden was associated with SPD during the pandemic. Measures supporting mental health for caregivers with increased caregiver burden should be implemented immediately.

Keywords: COVID-19, Informal caregiver, Caregiver burden, Mental health

1. Introduction

Mental health deterioration has become a worldwide problem during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. A recent study reported that the number of individuals in Japan experiencing severe psychological distress (SPD) increased from 9.3% in February 2020 to 11.3% in April 2020, representing a significant increase (Kikuchi et al., 2020). Informal caregivers (those who provide unpaid care or assistance to older adults, persons with disabilities, or other individuals requiring assistance) may have been particularly vulnerable to stress during the pandemic. These stressors include a changing or worsening care situation (Budnick et al., 2021; Irani et al., 2021; Rainero et al., 2021; Tsapanou et al., 2021); caring for vulnerable individuals at increased risk of severe illness from COVID-19 (Tsang et al., 2021); and limited access to other caregiving resources. During the pandemic, caregivers reported lower mental health compared with non-caregivers (Gallagher & Wetherell, 2020; Taniguchi et al., 2021; Yoshioka et al., 2021).

A meta-analysis by Del-Pino-Casado et al. (2019) reported that subjective caregiver burden is associated with an increased risk of depression, and Cohen et al. (2021) showed that approximately 50% of caregivers reported increased caregiver burden because of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is unknown whether increased caregiver burden during the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with SPD in caregivers of all ages, and whether this association remains after adjusting for subjective caregiver burden.

To the best of our knowledge, only one study from Japan has examined whether increased caregiver burden during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with caregiver mental health. Noguchi et al. (2021) found that, in caregivers aged 65 years or older who reported an increased burden during the pandemic, the prevalence of depressive symptoms increased from 54% in March 2020 to 79% in October 2020. In caregivers who did not report an increased burden, depressive symptoms increased from 52% to 58% during the same period. However, because 50%–60% of family caregivers in Japan are under the age of 65 (Sun et al., 2021), it is necessary to clarify the relationship between increased burden and mental health in caregivers of all ages. In Japan, 28.4% of the population (35.89 million people) is over the age of 65 (Statistics Bureau, 2021), and family members are the main caregivers (Cabinet Office, 2021). Moreover, because of regional differences in the status of the COVID-19 infection in Japan (Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, 2021), it is particularly important to understand nationwide trends in increasing caregiver burden.

In the current study, we aimed to investigate the percentage of informal caregivers in Japan who experienced increased caregiver burden during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as whether the association between increased caregiver burden and SPD was independent of the level of subjective caregiver burden.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design, participants, and ethics

Data were obtained from the Japan “COVID-19 and Society” Internet Survey (JACSIS) study, conducted between August 25 and September 30, 2020; Japan experienced a third peak in COVID-19 infections at the beginning of August 2020 (Amengual & Atsumi, 2021). The JACSIS study was a nationwide survey conducted by Rakuten Insight, a large internet survey agency with 2.3 million registered respondents (Rakuten Insight Inc., Tokyo, Japan). We distributed the questionnaire to 224,389 individuals aged 15–79 years old using a random sampling method. The sample was representative of the official demographic composition of Japan (as of October 1, 2019) in terms of age, gender, and living area (covering all 47 prefectures). We distributed the questionnaire until the number of participants reached the target for each gender, age, and prefecture category (28,000 participants in total). The response rate was 12.5%. To ensure the quality of the data, we excluded 2,518 respondents with discrepancies and artificial/unnatural responses (remaining respondents, n = 25,482). We excluded participants who selected any option other than the one indicated (“Please choose the option second from the bottom”), those who reported using “all” recreational substances and medications (i.e., sleeping pills, anxiolytic agents, legal/illegal opioids, cannabis, cocaine, etc.), and those with “all” chronic diseases (i.e., diabetes, asthma, stroke, ischemic heart disease, cancer, mental disease, etc.). We excluded respondents who indicated that they were not caregivers by answering “no” to the following question: “Are you currently caring for a family member who is 40 years old or older?” Thus, the final sample included 1,923 informal caregivers.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Osaka International Cancer Institute (approval number: 20084). The survey was conducted in accordance with the Act on the Protection of Personal Information, and web-based informed consent was obtained from all participants before they responded to the questionnaire. “E-points,” credit points that can be used for internet shopping and cash conversion, were offered as compensation for participating.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Psychological distress

We assessed SPD using the Kessler 6 Scale (K6) (Kessler et al., 2002). The K6 has been widely used in epidemiological studies to measure psychological distress among the general population and has been validated in Japan (Furukawa et al., 2008). The K6 comprises six questions, with each question answered on a five-point scale (“0 = never,” “1 = rarely,” “2 = sometimes,” “3 = often,” or “4 = always”). High scores indicate more severe mental disorders (range 0–24). SPD is defined as a K6 score ≥ 13 (Kessler et al., 2003). Cronbach's α coefficient of reliability in the present study was 0.95.

2.2.2. Caregiver burden

The primary predictor variable was the retrospective change in caregiver burden attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic. To assess retrospective changes in caregiver burden, participants were asked the following single question item: “Compared with before the COVID-19 pandemic (before January 2020), do you feel that your caregiver burden has increased?” Participants chose one of five responses: “1 = never,” “2 = occasionally,” “3 = sometimes,” “4 = often,” or “5 = always.” We categorized the responses into two groups: increased caregiver burden compared with that experienced before the COVID-19 pandemic (those who responded 2–5), and no increase in caregiver burden compared with that experienced before the COVID-19 pandemic (those who responded 1). In order to more precisely measure changes in caregiver burden, it might be necessary to measure at two points: one before the COVID-19 pandemic and the other during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as this was a cross-sectional study, the only way to measure the change from the pre-COVID-19 pandemic is retrospective. This method was also employed by the previous studies (Cohen et al., 2021; Noguchi et al., 2021).

Overall caregiver burden was assessed using the 8-item Japanese short version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview (J-ZBI-8), which is widely used to estimate the amount of burden caregivers experience because of caregiving (Zarit et al., 1980). Arai et al. (2003) validated the J-ZBI-8 in the Japanese population. Participants responded to each item on a five-point scale (“0 = never,” “1 = rarely,” “2 = sometimes,” “3 = often,” or “4 = always”). The total scores ranged from 0 to 32, with higher scores indicating greater burden. Cronbach's α coefficient of reliability in the present study was 0.93.

2.2.3. Covariates

We assessed demographic, socioeconomic, health, and caregiving variables of both caregivers and care-receivers. Demographic characteristics included age (“15–39,” “40–59,” and “60–79” years); gender; and marital status (“married” or “not married”). Socioeconomic variables included education (“high school educated or lower,” “college educated or higher,” and “other”); household income (“≤ 2.9 million yen,” “3.0–6.9 million yen,” “≥ 7.0 million yen,” and “unknown/undisclosed”); and employment (“working” or “not working”). For health, we used one variable to note whether caregivers were undergoing any disease treatment (defined as being under treatment for hypertension, angina, myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or cancer). Caregiver variables included caregiver role (“primary caregiver” or “second caregiver”), the number of hours spent caring per day (short: “help only when needed”; middle: “2–3 hours” or “about half the day”; or long: “almost all day”), and their relationship to the care-receiver (“child/child-in-law,” “spouse,” or “other relative”). Care-receiver variables included care level. In Japan, long-term care (LTC) services are provided for residents in nursing homes and for community-dwelling older adults with disabilities. To define the level of care required by care-receivers in our study, we used the government-certified levels for necessary public LTC. There are seven LTC service levels (support levels 1–2 and care need levels 1–5). For our purposes, we divided participants into the following categories: “not qualified or unknown,” “support level 1–2,” “care need level 1–2,” and “care need level 3–5.”

2.3. Statistical Analyses

We analyzed the data from 1,920 caregivers (excluding three who chose “other” for their education level). First, we used descriptive analysis and bivariate statistics (chi-square and independent t-tests) to determine whether there were significant differences in demographic characteristics or environmental variables between caregivers with SPD and those without SPD, and between caregivers who reported increased caregiver burden and those who did not. Second, we used binary logistic regression adjusted for covariates to examine the association between SPD and increased caregiver burden. We added interaction terms of the increased caregiver burden with demographic, socioeconomic, health, and caregiving variables. Finally, to examine the differential association between increased caregiver burden and SPD, binary logistic regression was separately conducted in demographic, socioeconomic, health, and caregiving status (stratified analysis) while adjusting for covariates other than the stratification variables. An adjusted odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant association. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

Caregiver characteristics are summarized in Table 1 . The mean age was 52.3 years (standard deviation, SD 15.9), and 48.8% of respondents were male. Of the caregivers, 56.7% reported increased caregiver burden, and 19.3% experienced SPD. The mean K6 score was 6.4 (SD 6.5), and the mean J-ZBI-8 score was 11.4 (SD 8.1). Caregivers with SPD had significantly higher J-ZBI-8 scores (t = 11.48, p < 0.001), and a higher proportion of increased caregiver burden (χ2[1] = 107.21, p < 0.001). J-ZBI-8 scores and K6 scores were moderately correlated (r = 0.418, p < .001; not shown in the table). Caregivers with SPD were younger than those without SPD (χ2[2] = 220.30, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of caregivers with and without severe psychological distress (SPD)

| Variable | All n = 1,920 |

Caregivers without SPD K6 < 13, n = 1,549 |

Caregivers with SPD K6 ≥ 13, n = 371 |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Male | 48.8 | 48.3 | 50.7 | 0.409 |

| Female | 51.3 | 51.7 | 49.3 | |

| Age (%) | ||||

| 15–39 years | 21.6 | 15.5 | 46.9 | < 0.001 |

| 40–59 years | 38.7 | 38.3 | 40.2 | |

| 60–79 years | 39.7 | 46.2 | 12.9 | |

| Education (%) | ||||

| High school educated or lower | 28.2 | 28.7 | 26.1 | 0.333 |

| College educated or higher | 71.8 | 71.3 | 73.9 | |

| Marital status (%) | ||||

| Married | 62.8 | 65.7 | 50.7 | < 0.001 |

| Not married | 37.2 | 34.3 | 49.3 | |

| Household income (%) | ||||

| ≤ 2.9 million yen | 18.4 | 17.2 | 23.5 | 0.003 |

| 3.0–6.9 million yen | 37.3 | 37.6 | 36.1 | |

| ≥ 7.0 million yen | 25.9 | 25.6 | 27.2 | |

| Unknown/undisclosed | 18.4 | 19.6 | 13.2 | |

| Current job situation (%) | ||||

| Working | 60.9 | 59.2 | 31.8 | 0.001 |

| Not working | 39.1 | 40.8 | 68.2 | |

| Disease treatment (%) | ||||

| Yes | 31.6 | 31.6 | 31.3 | 0.891 |

| No | 68.4 | 68.4 | 68.7 | |

| Caregiving role (%) | ||||

| Primary caregiver | 35.4 | 35.3 | 35.8 | 0.846 |

| Second caregiver | 64.6 | 64.7 | 64.2 | |

| Caregiver burden (Zarit-8), Mean (SD) | 11.4 (8.1) | 10.4 (7.7) | 15.6 (8.5) | < 0.001 |

| The change of caregiver burden during the COVID-19 pandemic (%) |

||||

| Increased caregiver burden | 56.7 | 50.9 | 80.6 | < 0.001 |

| Not increased caregiver burden | 43.3 | 49.1 | 19.4 | |

| The number of hours spent caring per day (%) |

||||

| Short | 61.8 | 65.4 | 46.6 | < 0.001 |

| Middle | 27.6 | 25.0 | 38.5 | |

| Long | 10.6 | 9.6 | 14.8 | |

| The relationship to the care-receiver (%) | ||||

| Children/children-in-law | 76.4 | 78.9 | 66.0 | < 0.001 |

| Spouse | 8.6 | 8.5 | 9.2 | |

| Other relative | 14.9 | 12.6 | 24.8 | |

| The care-receiver's care level (%) | ||||

| Not qualified/unknown | 19.1 | 17.8 | 24.8 | 0.001 |

| Support level 1–2 | 18.0 | 17.2 | 21.3 | |

| Care need level 1–2 | 31.5 | 32.5 | 27.0 | |

| Care need level 3–5 | 31.4 | 32.5 | 27.0 | |

| The Kessler 6 Scale (K6), Mean (SD) | 6.4 (6.5) | 3.9 (4.1) | 16.8 (3.3) | < 0.001 |

SD: standard deviation.

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

J-ZBI-8: the 8-item Japanese short version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview.

p values were calculated using chi-square and independent t-tests.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of caregivers who did not indicate increased caregiver burden versus those who did. Caregivers with increased caregiver burden were younger (χ2[2] = 78.90, p < 0.001) and spent a longer time caregiving (χ2[2] = 108.64, p < 0.001) than those without increased caregiver burden. Among caregivers who indicated an increased caregiver burden, J-ZBI-8 scores were higher (15.0; SD 7.5) than those among caregivers who did not indicate an increased burden (6.6; SD 6.3, t = 26.54, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of caregivers with and without change in caregiver burden

| Variable | Caregivers not increased caregiver burden n = 832 |

Caregivers increased caregiver burden n = 1,088 |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | |||

| Male | 46.5 | 50.5 | 0.090 |

| Female | 53.5 | 49.5 | |

| Age (%) | |||

| 15–39 years | 13.0 | 28.1 | < 0.001 |

| 40–59 years | 38.5 | 38.9 | |

| 60–79 years | 48.6 | 33.0 | |

| Education (%) | |||

| High school educated or lower | 32.3 | 25.0 | < 0.001 |

| College educated or higher | 67.7 | 75.0 | |

| Marital status (%) | |||

| Married | 33.2 | 40.3 | 0.001 |

| Not married | 66.8 | 59.7 | |

| Household income (%) | |||

| ≤ 2.9 million yen | 17.8 | 18.8 | 0.142 |

| 3.0–6.9 million yen | 38.7 | 36.3 | |

| ≥ 7.0 million yen | 23.7 | 27.6 | |

| Unknown/undisclosed | 19.8 | 17.3 | |

| Current job situation (%) | |||

| Working | 57.8 | 63.3 | 0.014 |

| Not working | 42.2 | 36.7 | |

| Disease treatment (%) | |||

| Yes | 31.9 | 31.3 | 0.812 |

| No | 68.1 | 68.7 | |

| Caregiving role (%) | |||

| Primary caregiver | 31.4 | 38.5 | 0.001 |

| Second caregiver | 68.6 | 61.5 | |

| Caregiver burden (Zarit-8), Mean (SD) | 6.6 (6.3) | 15.0 (7.5) | < 0.001 |

| The number of hours spent caring per day (%) |

|||

| Short | 74.8 | 51.8 | < 0.001 |

| Middle | 16.8 | 35.8 | |

| Long | 8.4 | 12.3 | |

| The relationship to the care-receiver (%) | |||

| Children/children-in-law | 77.8 | 75.4 | 0.041 |

| Spouse | 9.5 | 8.0 | |

| Other relative | 12.7 | 16.6 | |

| The care-receiver's care level (%) | |||

| Not qualified/unknown | 16.9 | 20.8 | 0.065 |

| Support level 1–2 | 17.3 | 18.6 | |

| Care need level 1–2 | 31.7 | 31.3 | |

| Care need level 3–5 | 34.0 | 29.4 | |

| The Kessler 6 Scale (K6), Mean (SD) | 3.5 (5.4) | 8.5 (6.4) | < 0.001 |

SD: standard deviation.

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

J-ZBI-8: the 8-item Japanese short version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview.

p values were calculated using chi-square and independent t-tests.

Table 3 shows the results of binary logistic regression analysis for caregivers with SPD. The analysis revealed that increased caregiver burden was significantly positively associated with SPD (adjusted OR: 1.90; 95% CI 1.37–2.66). J-ZBI-8 was also positively associated with SPD (adjusted OR: 1.05; 95% CI 1.03–1.07). As a sensitivity analysis, we used a continuous variable of increased caregiver burden to examine the association with SPD instead of using a binary variable. The results were similar to the analysis with a binary variable (adjusted OR: 1.20; 95% CI 1.06–1.36, in Supplemental table 1).

Table 3.

Association between severe psychological distress (SPD) and increased caregiver burden: Results of logistic estimates

| Variable | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|

| Burden | |

| Increased caregiver burden (ref: Not increased caregiver burden) | 1.90 (1.37–2.66) |

| Caregiver burden (J-ZBI-8) | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) |

| Gender (ref: Female) | |

| Male | 0.80 (0.60–1.06) |

| Age (ref: 40–59 years) | |

| 15–39 years | 2.31 (1.65–3.22) |

| 60–79 years | 0.24 (0.16–0.36) |

| Education (ref: High school educated or lower) | |

| College educated or higher | 1.03 (0.77–1.38) |

| Marital status (ref: Not married) | |

| Married | 0.94 (0.71–1.25) |

| Household income (ref: ≤ 2.9 million yen) | |

| 3.0–6.9 million yen | 0.67 (0.47–0.96) |

| ≥ 7.0 million yen | 0.66 (0.44–0.97) |

| Unknown/undisclosed | 0.52 (0.34–0.81) |

| Current job situation (ref: Not working) | |

| Working | 1.05 (0.78–1.43) |

| Disease treatment (ref: No) | |

| Yes | 1.33 (0.99–1.77) |

| Caregiving role (ref: Second caregiver) | |

| Primary caregiver | 0.93 (0.69–1.25) |

| The number of hours spent caring per day (ref: Short) | |

| Middle | 1.42 (1.05–1.93) |

| Long | 1.95 (1.26–3.01) |

| The relationship to the care-receiver (ref: Children/children-in-law) | |

| Spouse | 1.60 (0.96–2.65) |

| Other relative | 1.17 (0.82–1.68) |

| The care-receiver's care level (ref: Care need level 3–5) | |

| Not qualified/unknown | 1.10 (0.75–1.61) |

| Support level 1–2 | 1.31 (0.90–1.92) |

| Care need level 1–2 | 0.91 (0.65–1.28) |

Ref: reference.

J-ZBI-8: the 8-item Japanese short version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview.

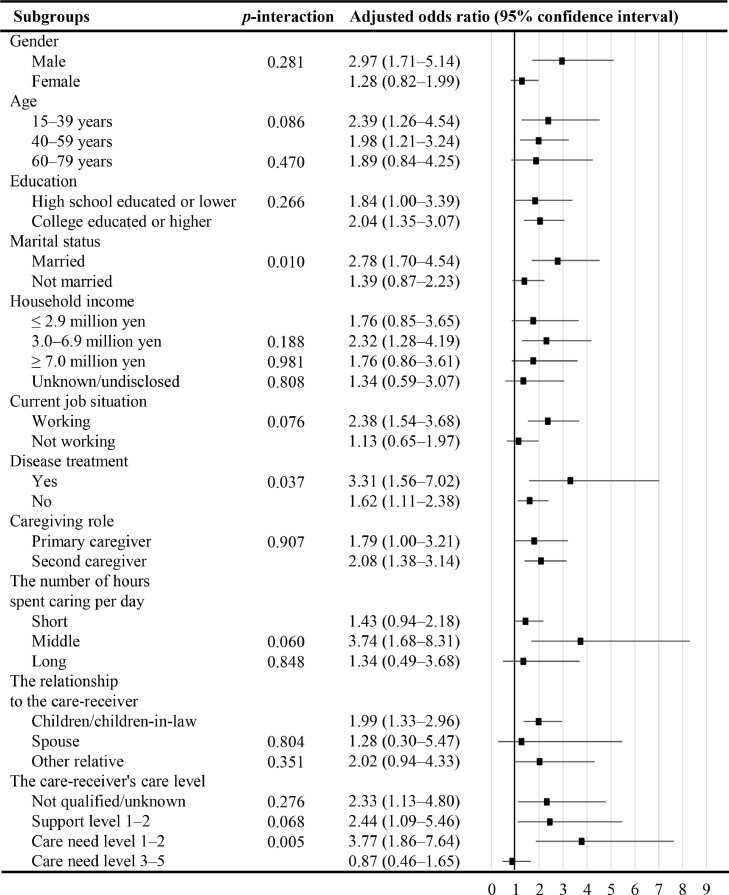

Significant interaction effects indicated an association between increased caregiver burden and SPD by marital status, disease treatment, and the care-receiver's care level in Fig. 1 . In subgroup-stratified analyses, there were stronger associations between increased caregiver burden and SPD in caregivers that were married compared with those who were not married (adjusted OR: 2.78; 95% CI 1.70–4.54, adjusted OR of 1.39; 95% CI 0.87–2.23, respectively), in caregivers who were undergoing disease treatment compared with those who were not undergoing disease treatment (adjusted OR of 3.31; 95% CI 1.56–7.02, adjusted OR of 1.62; 95% CI 1.11–2.38, respectively), and in those with a care-receiver with a care need level of 1–2 compared with those with a care-receiver with a care need level of 3–5 (adjusted OR: 3.77; 95% CI 1.86–7.64, adjusted OR: 0.87; 95% CI 0.46–1.65, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Stratified analysis of the association between increased caregiver burden and SPD by demographic, socioeconomic, health, and caregiving status subgroups. Results of logistic estimates adjusted for all listed variables and current caregiver burden (the 8-item Japanese short version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview score).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association between increased caregiver burden and SPD during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan while also controlling for current caregiver burden. We found that more than half (57%) of caregivers reported increased caregiver burden during the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, Noguchi et al. (2021) found that only 38% of Japanese caregivers aged 65 years or older experienced increased caregiver burden during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the age range of the participants in this study was broad (15–79 years), and the higher proportion of those with increased caregiver burden during the COVID-19 pandemic was observed in younger age group. Thus, the proportion in this study was possibly higher than that in Noguchi et al. (2021).

In the current study, 19.3% of caregivers had SPD, which is a larger percentage than the 6% reported in Japan between 2007 and 2016 (Sun et al., 2021). However, the increase we observed should be interpreted with caution, because our sample included more men, and caregivers were younger on average. In the United States, the proportion of caregivers with depression during the COVID-19 pandemic (May 2020) was greater than that prior to the pandemic (Gallagher & Wetherell, 2020). It is likely that the mental health of caregivers in Japan will continue to deteriorate in a similar manner throughout the pandemic, and this situation may require intervention measures.

Our results revealed that the increased caregiver burden during the COVID-19 pandemic was positively associated with SPD. This association is similar to the finding of a previous study reporting that older caregivers whose caregiver burden increased during the COVID-19 pandemic had a higher risk of depressive symptoms compared with non-caregivers (Noguchi et al., 2021). A recent study in the United States reported that changes in caregivers’ care tasks because of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in concerns about their loved ones’ physical and mental health, limited access to other caregiving sources, and limited opportunities to maintain personal well-being (Irani et al., 2021). By June 2020, the number of users of outpatient LTC services in Japan (including a program to help people with daily tasks like bathing and eating, and another program in which care-receivers could enjoy recreational activities at a facility) was reduced compared with prior to the pandemic (Ito et al., 2021). This may have led caregivers whose care-receiver could not use such outpatient and respite care services to experience increased caregiver burden. It is possible that caregiver SPD was particularly likely in situations where a previously utilized service suddenly became unavailable. Stress caused by limited social contact and increased telework during the pandemic, which further disrupted the balance between work, life, and caregiving, likely worsened mental health along with increased caregiver burden (Xiao et al., 2021). Furthermore, according to social norms in Japan, it is often taken for granted that families will provide care (Pharr et al., 2014), which may have restricted those with increased caregiver burden from seeking help.

The association between increased caregiver burden and SPD was stronger among caregivers who were married, those who were undergoing disease treatment, and those with a care-receiver's care need level of 1–2 compared with those with a care need level of 3–5. Regarding disease treatment, people with diseases had a higher risk of severe illness from COVID-19 (Tsang et al., 2021). This may have led to a higher level of stress related to COVID-19 and a stronger association between increased caregiver burden and SPD. Our results indicated that increased caregiver burden might increase the risk of SPD among caregivers caring for individuals with care need level 1–2 compared with the risk among those caring for individuals with care need level 3–5. Those with care need level 1–2 mainly receive services for life support (e.g., watchful waiting assistance, house cleaning, and laundry) and outpatient services, while those with care need level 3–5 mainly receive services for body care (e.g., toileting, eating, and bathing). The number of users of outpatient services was reduced compared with prior to the pandemic, but other services were not changed (Ito et al., 2021). Therefore, for caregivers of people with care level 1–2 who lost access to services, the increase in caregiver burden may have been more associated with SPD. Regarding marital status, there was a stronger association among married caregivers who were likely to receive support from their spouses. This mechanism could not be explained by the present findings, and further research is needed to address this question. In summary, targeted interventions based on marital status, disease treatment, and the care-receiver's care level may be effective for mitigating the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on caregiver mental health.

We should carefully interpret the findings of this study because cultural differences might influence the perceptions of caregiving and the caregivers’ health. The sociocultural stress and coping model suggests that cultural background has a small effect on the association between caregiver burden and caregivers’ health but does affect caregivers’ health by causing differences in coping styles and social support (Knight et al., 2010). This model is also supported by the study which examined biological pathways. Hartanto et al. (2020) reported that the higher perceived obligation toward family and close friends was associated with poorer biological health (including inflammation and cardiovascular risk as indicated by measures such as interleukin-6, C-reactive protein levels, blood pressure, and total/high-density lipoprotein) among Japanese people, while that was with better biological health in American people. In addition, other articles reported that different cultural groups had different levels of caregiver burden (Knight et al., 2002) and that factors associated with caregiver burden differed by nations (Cho et al., 2020). Therefore, the cultural background that constitutes people's perceptions should be assessed to develop appropriate measures for caregiver mental health.

Several limitations of the current study should be considered. First, we did not collect details of care-receivers’ illness/disability type; some conditions (e.g., dementia) may confer an additional risk and entail differences in the caregiver experience and associated caregiver burden (Altieri & Santangelo, 2021; Kurasawa et al., 2012). Further research into whether increased caregiver burden is more common among caregivers of individuals with particular diseases is needed. Second, the change in caregiver burden was measured retrospectively using a single item. Therefore, future prospective studies should be conducted to provide more robust results with less bias. Third, the use of a cross-sectional design did not allow for causal inferences about the association between deterioration in mental health and increased caregiver burden. However, it would have been difficult to collect data in advance of the unexpected COVID-19 pandemic, and the results of the current study remain important for understanding the pandemic's impact on caregivers. Finally, it is difficult to generalize the results of this study to countries other than Japan. During the study period of August and September 2020, Japan had fewer deaths from COVID-19 than any other country in the world (Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, 2021), and the Japanese government's COVID-19 control measures were not very stringent compared with many other Asian countries (Chen et al., 2021). More severe conditions in other countries may have resulted in more serious mental health conditions.

Those working in the field of social care need to understand the specific causes of increased burden on caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because caregivers are required to perform a wide variety of tasks (e.g., providing emotional support and acute care; Schulz et al., 2020), increased caregiver burden may include physical burden (increased care time owing to lack of availability of formal care; Cohen et al., 2021), emotional burden (concern about the risk of COVID-19 infection of the care-receiver; Todorovic et al., 2020), and financial burden (using home services to prevent COVID-19 infection; Wolff et al., 2016). Understanding the factors that contribute to an individual's caregiver burden during the COVID-19 pandemic and providing the necessary support can help prevent the deterioration of caregivers’ mental health.

5. Conclusions

The current study used a nationwide internet survey in Japan to show that increased caregiver burden was associated with a 1.90-times greater risk of SPD compared with caregivers without increased caregiver burden. Moreover, more than half of the caregivers surveyed indicated that their caregiver burden had increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, mental health interventions should be implemented for caregivers during the pandemic regardless of their level of caregiver burden.

CRediT author contributions statement

Isuzu Nakamoto: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Hiroshi Murayama: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Mai Takase: Writing – review & editing. Yoko Muto: Writing – review & editing. Tami Saito: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Takahiro Tabuchi: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Benjamin Knight, MSc., from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grants [17H03589, 19K10671, 19K10446, 18H03107, 18H03062, and 21H04856], the JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists [19K19439], Research Support Program to Apply the Wisdom of the University to Tackle COVID-19 Related Emergency Problems, University of Tsukuba, and Health Labour Sciences Research Grant [19FA1005 and 19FG2001].

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.archger.2022.104756.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability statement

: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Altieri M., Santangelo G. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on caregivers of people with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amengual O., Atsumi T. COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Rheumatology International. 2021;41(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04744-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai Y., Tamiya N., Yano E. The short version of the Japanese version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview (J-ZBI_8) Jpn J Geriat. 2003;40(5):497–503. doi: 10.3143/geriatrics.40.497. 10.3143/geriatrics.40.497. (in Japanese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budnick A., Hering C., Eggert S., Teubner C., Suhr R., Kuhlmey A., Gellert P. Informal caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic perceive additional burden: findings from an ad-hoc survey in Germany. BMC Health Services Research. 2021;21(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06359-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office. (2021). Annual Report on the Ageing Society: 2018 (Summary). Retrieved from https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/english/annualreport/2018/2018pdf_e.html. Accessed November 27, 2021.

- Chen S., Guo L., Alghaith T., Dong D., Alluhidan M., Hamza M.M., Herbst C.H., Zhang X., Tagtag G.C.A., Zhang Y., Alazemi N., Saber R., Alsukait R., Tang S. Effective COVID-19 control: a comparative analysis of the stringency and timeliness of government responses in Asia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(16):8686. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J., Nakagawa T., Martin P., Gondo Y., Poon L.W., Hirose N. Caregiving centenarians: cross-national comparison in caregiver-burden between the United States and Japan. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(5):774–783. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1544221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S.A., Kunicki Z.J., Drohan M.M., Greaney M.L. Exploring changes in caregiver burden and caregiving intensity due to COVID-19. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine. 2021;7 doi: 10.1177/2333721421999279. 233372142199927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del-Pino-Casado R., Rodríguez Cardosa M., López-Martínez C., Orgeta V. The association between subjective caregiver burden and depressive symptoms in carers of older relatives: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217648. Article e0217648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T.A., Kawakami N., Saitoh M., Ono Y., Nakane Y., Nakamura Y., Tachimori H., Iwata N., Uda H., Nakane H., Watanabe M., Naganuma Y., Hata Y., Kobayashi M., Miyake Y., Takeshima T., Kikkawa T. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2008;17(3):152–158. doi: 10.1002/mpr.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S., Wetherell M.A. Risk of depression in family caregivers: unintended consequence of COVID-19. BJPsych Open. 2020;(6):6. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartanto A., Yee-Man Lau I., Yong J.C. Culture moderates the link between perceived obligation and biological health risk: Evidence of culturally distinct pathways for positive health outcomes. Social Science & Medicine. 2020;244 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irani E., Niyomyart A., Hickman R.L. Family caregivers’ experiences and changes in caregiving tasks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Nursing Research. 2021;105477382110142 doi: 10.1177/10547738211014211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Hirata-Mogi S., Watanabe T., Sugiyama T., Jin X., Kobayashi S., Tamiya N. Change of use in community services among disabled older adults during COVID-19 in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(3):1148. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. (2021). COVID-19 Map. Retrieved from https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed November 27, 2021.

- Kessler R.C., Andrews G., Colpe L.J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D.K., Normand S.L., Walters E.E., Zaslavsky A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Barker P.R., Colpe L.J., Epstein J.F., Gfroerer J.C., Hiripi E., Howes M.J., Normand S.-L.T., Manderscheid R.W., Walters E.E., Zaslavsky A.M. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi H., Machida M., Nakamura I., Saito R., Odagiri Y., Kojima T., Watanabe H., Fukui K., Inoue S. Changes in psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: A longitudinal study. Journal of Epidemiology. 2020;30(11):522–528. doi: 10.2188/jea.je20200271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight B.G., Robinson G.S., Flynn Longmire C.V., Chun M., Nakao K., Kim J.H. Cross cultural issues in caregiving for persons with dementia: do familism values reduce burden and distress? Ageing International. 2002;27(3):70–94. doi: 10.1007/s12126-003-1003-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight B.G., Sayegh P. Cultural values and caregiving: the updated sociocultural stress and coping model. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65b(1):5–13. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurasawa S., Yoshimasu K., Washio M., Fukumoto J., Takemura S., Yokoi K., Arai Y., Miyashita K. Factors influencing caregivers’ burden among family caregivers and institutionalization of in-home elderly people cared for by family caregivers. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine. 2012;17(6):474–483. doi: 10.1007/s12199-012-0276-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi T., Hayashi T., Kubo Y., Tomiyama N., Ochi A., Hayashi H. Association between family caregivers and depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults in Japan: A cross-sectional study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2021;96 doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2021.104468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharr J.R., Dodge Francis C., Terry C., Clark M.C. Culture, caregiving, and health: exploring the influence of culture on family caregiver experiences. ISRN Public Health. 2014;2014:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2014/689826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rainero I., Bruni A.C., Marra C., Cagnin A., Bonanni L., Cupidi C., Laganà V., Rubino E., Vacca A., Di Lorenzo R., Provero P., Isella V., Vanacore N., Agosta F., Appollonio I., Caffarra P., Bussè C., Sambati R., Quaranta D., Guglielmi V., Logroscino G., Filippi M., Tedeschi G., Ferrarese C. The impact of COVID-19 quarantine on patients with dementia and family caregivers: A nation-wide survey. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.625781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R., Beach S.R., Czaja S.J., Martire L.M., Monin J.K. Family caregiving for older adults. Annual Review of Psychology. 2020;71(1):635–659. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Bureau. (2021). Statistics Bureau Home Page/Population Estimates/Current Population Estimates as of October 1, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/jinsui/2019np/index.html. Accessed November 27, 2021.

- Sun Y., Iwagami M., Watanabe T., Sakata N., Sugiyama T., Miyawaki A., Tamiya N. Factors associated with psychological distress in family caregivers: Findings from nationwide data in Japan. Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 2021;21(9):855–864. doi: 10.1111/ggi.14250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi Y., Miyawaki A., Tsugawa Y., Murayama H., Tamiya N., Tabuchi T. Family caregiving and changes in mental health status in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2021;104531 doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2021.104531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic N., Vracevic M., Rajovic N., Pavlovic V., Madzarevic P., Cumic J., Mostic T., Milic N., Rajovic T., Sapic R., Milcanovic P., Velickovic I., Culafic S., Stanisavljevic D., Milic N. Quality of life of informal caregivers behind the scene of the COVID-19 epidemic in Serbia. Medicina. 2020;56(12):647. doi: 10.3390/medicina56120647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang H.F., Chan L.W.C., Cho W.C.S., Yu A.C.S., Yim A.K.Y., Chan A.K.C., Ng L.P.W., Wong Y.K.E., Pei X.M., Li M.J.W., Wong S.-C.C. An update on COVID-19 pandemic: the epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention and treatment strategies. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 2021;19(7):877–888. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2021.1863146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsapanou A., Papatriantafyllou J.D., Yiannopoulou K., Sali D., Kalligerou F., Ntanasi E., Zoi P., Margioti E., Kamtsadeli V., Hatzopoulou M., Koustimpi M., Zagka A., Papageorgiou S.G., Sakka P. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on people with mild cognitive impairment/dementia and on their caregivers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2021;36(4):583–587. doi: 10.1002/gps.5457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J.L., Spillman B.C., Freedman V.A., Kasper J.D. A national profile of family and unpaid caregivers who assist older adults with health care activities. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016;176(3):372. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y., Becerik-Gerber B., Lucas G., Roll S.C. Impacts of working from home during COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental well-being of office workstation users. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(3):181–190. doi: 10.1097/jom.0000000000002097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka T., Okubo R., Tabuchi T., Odani S., Shinozaki T., Tsugawa Y. Factors associated with serious psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: a nationwide cross-sectional internet-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051115. Article e051115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit S.H., Reever K.E., Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired seniors ly: correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649–655. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.