Abstract

The genetic basis of alcohol use disorder (AUD) is complex. Understanding how natural genetic variation contributes to alcohol phenotypes can help us identify and understand the genetic basis of AUD. Recently, a single nucleotide polymorphism in the human foraging (for) gene ortholog, Protein Kinase cGMP-Dependent 1 (PRKG1), was found to be associated with stress-induced risk for alcohol abuse. However, the mechanistic role that PRKG1 plays in AUD is not well understood. We use natural variation in the Drosophila for gene to describe how variation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) activity modifies ethanol-induced phenotypes. We found that variation in for affects ethanol-induced increases in locomotion and memory of the appetitive properties of ethanol intoxication. Further, these differences may stem from the ability to metabolize ethanol. Together, this data suggests that natural variation in PKG modulates cue reactivity for alcohol, and thus could influence alcohol cravings by differentially modulating metabolic and behavioral sensitivities to alcohol.

Keywords: Foraging, PRKG1, cGMP-dependent protein kinase, alcohol, memory, metabolism, locomotion, AUD, Drosophila

Introduction

Determining the mechanisms through which individual genes influence natural variation in behavior has been difficult due to the complexity of the genetic basis of heritable behavior. A notable exception to the genetic complexity underlying behavior is the foraging (for) gene in Drosophila melanogaster (Sokolowski, 1980). Variants of for show increased (rovers or forR) or decreased (sitters or fors) cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) activity, which affects food search behavior (Osborne et al., 1997). Rovers show increased pathlength while foraging, whereas sitters show decreased pathlength and stay longer at one food source (Hughson et al., 2018; Sokolowski, 1980). for also causes phenotypical pleiotropy in flies, in part due to multiple promotors driving expression in different cell types (Allen, Anreiter, Vesterberg, Douglas, & Sokolowski, 2018), and at different developmental stages (Brown et al., 2014; Graveley et al., 2011; Nègre et al., 2011). The foraging gene affects foraging behavior (Anreiter, Kramer, & Sokolowski, 2017; Anreiter & Sokolowski, 2018a; Pereira & Sokolowski, 1993; Sokolowski, 1980; de Belle & Sokolowski, 1987, Allen et al., 2018), fat and glucose stores (Allen et al., 2018; Kaun, Chakaborty-Chatterjee, & Sokolowski, 2008), food intake (Allen, Anreiter, Neville, & Sokolowski, 2017; Kaun et al., 2008), sucrose response (Belay et al., 2007; Scheiner, Sokolowski, & Erber, 2004), sleep (Donlea et al., 2012), habituation (Eddison, Belay, Sokolowski, & Heberlein, 2012; Engel, Xie, Sokolowski, & Wu, 2000; Scheiner et al., 2004), nociception (Dason et al., 2020), oviposition (McConnell & Fitzpatrick, 2017), stress response (Caplan, Milton, & Dawson-Scully, 2013; Dawson-Scully et al., 2010; Dawson-Scully, Armstrong, Kent, Robertson, & Sokolowski, 2007), as well as learning and memory (Engel et al., 2000; Kaun, Hendel, Gerber, & Sokolowski, 2007; Kuntz, Poeck, Sokolowski, & Strauss, 2012; Mery et al., 2007; Reaume, Sokolowski, & Mery, 2011; Scheiner et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2008).

Moreover, for’s role as a behavioral modifier in a wide range of behaviors is conserved across species including Apis mellifera (Heylen et al., 2008), Xenopus laevis (Robertson & Sillar, 2009), Mus musculus (Armstrong, López-Guerrero, Dawson-Scully, Peña, & Robertson, 2010), Caenorhabditis elegans (Fujiwara, Sengupta, & McIntire, 2002; Raizen et al., 2008), and Homo sapiens (Sokolowski et al., 2017; Struk et al., 2019). Given for’s conserved role, understanding the mechanistic actions through which for affects behavior may lead to insight regarding conserved functions of how natural genetic variation alters behavior.

More recently, Protein Kinase cGMP-Dependent 1 (PRKG1), the human ortholog of for (Hu et al., 2011; Sokolowski et al., 2017), was implicated in stress-induced risk for alcohol abuse (Hawn et al., 2018; Polimanti et al., 2018). A gene-by-environment genome-wide interaction study (GEWIS) investigating mechanisms by which traumatic life events influence genetic variation in relation to alcohol misuse, revealed several risk alleles for alcohol use disorder (AUD) including PRKG1 (Polimanti et al., 2018). Similarly, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) implicated PRKG1 in other stressed induces phenotypes like posttraumatic stress disorder (Ashley-Koch et al., 2015).

Other components of cGMP signaling have also been implicated in alcohol-associated phenotypes. Consumption of alcohol increases cGMP levels in the rat cortex, striatum and hippocampus (Uzbay et al., 2004). Increasing cGMP levels in the rat ventral tegmental area (VTA) or medial pre-frontal cortex (mPFC) reduces the ability of alcohol deprivation to enhance drinking, which is reversed by inhibiting PKG (Romieu, Gobaille, Aunis, & Zwiller, 2008). Finally, deletion of PKG type II in mice reduces alcohol’s sedative effects and increases alcohol consumption (Werner et al., 2004). NO/cGC/cGMP/PKG signaling also causes neuroadaptive changes in synaptic activity, thereby affecting distinct forms of learning and memory, such as object recognition, motor adaptation and fear conditioning (Kleppisch & Feil, 2009; Renger, Yao, Sokolowski, & Wu, 1999; Wen, Zhang, & Zhang, 2018; Xu et al., 2015). This signaling pathway similarly inhibits dopamine release in brain regions that are involved in addiction (Guevara-Guzman, Emson, & Kendrick, 1994; Samson, Bianchi, & Mogg, 1988; Thiriet et al., 2001), and contributes to cocaine self-administration (Deschatrettes, Romieu, & Zwiller, 2013) and morphine induced neuroadaptation (Nugent, Penick, & Kauer, 2007). This compounding evidence suggests PRGK1 plays a critical role in alcohol consumption, and calls for a better understanding of for’s mechanistic role in alcohol induced behaviors.

Drosophila has proven to be a valuable model organism for identifying genes and elucidating mechanisms associated with AUD (Engel, Taber, Vinton, & Crocker, 2019; Park, Ghezzi, Wijesekera, & Atkinson, 2017; Petruccelli & Kaun, 2019). In addition to genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic approaches, simple forward and reverse genetic approaches can be performed to identify genes that affect alcohol-induced behaviors, and to elucidate the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying candidate genes linked to AUD. Due to the huge variety of genetic tools available in Drosophila, many cell types, neural circuits and genes have been linked to an alcohol phenotype (Acevedo, Peru y Colon de Portugal, Gonzalez, Rodan, & Rothenfluh, 2015; Butts et al., 2019; Claßen & Scholz, 2018; Ghezzi, Al-Hasan, Krishnan, Wang, & Atkinson, 2013; Ghezzi, Krishnan, et al., 2013; Kong et al., 2010; Lathen, Merrill, & Rothenfluh, 2020; Lee, Mathies, & Grotewiel, 2019; Ojelade et al., 2015; Parkhurst et al., 2018; Petruccelli et al., 2018; Pinzón et al., 2017; Rodan & Rothenfluh, 2010; Scaplen et al., 2019, 2020; Shalaby et al., 2017; Shohat-Ophir, Kaun, Azanchi, Mohammed, & Heberlein, 2012). Therefore, investigating for’s role in relation to alcohol phenotypes in the fly might help to unravel the function of PRKG1 in alcohol addiction in humans.

Material and methods

Fly stocks and rearing conditions

The following fly strains were used: fors (sitter), forR (rover) and fors2. fors and forR flies carry the natural rover/sitter polymorphisms in for. fors2 flies have a rover genetic background but carry a gamma radiation-induced mutation in for that results in lower PKG activity levels and sitter behavior in many of the for-related phenotypes (de Belle, Hilliker, & Sokolowski, 1989; Osborne et al., 1997; Pereira & Sokolowski). However, the fors2 mutant does not always affect for-dependent phenotypes, and to our knowledge, specific alterations in DNA sequence as a result of the s2 mutation are unknown (Camiletti, Awde, & Thompson, 2014; Kent, Daskalchuk, Cook, Sokolowski, & Greenspan, 2009). Flies were raised on standard cornmeal agar food media with tegosept anti-fungal agent. Flies were kept at 24 °C and 65% humidity with a 14/10-h light/dark cycle. Male flies for all strains were collected 1–2 days after hatching and used for behavioral experiments at day 3–5 after eclosion.

Group activity

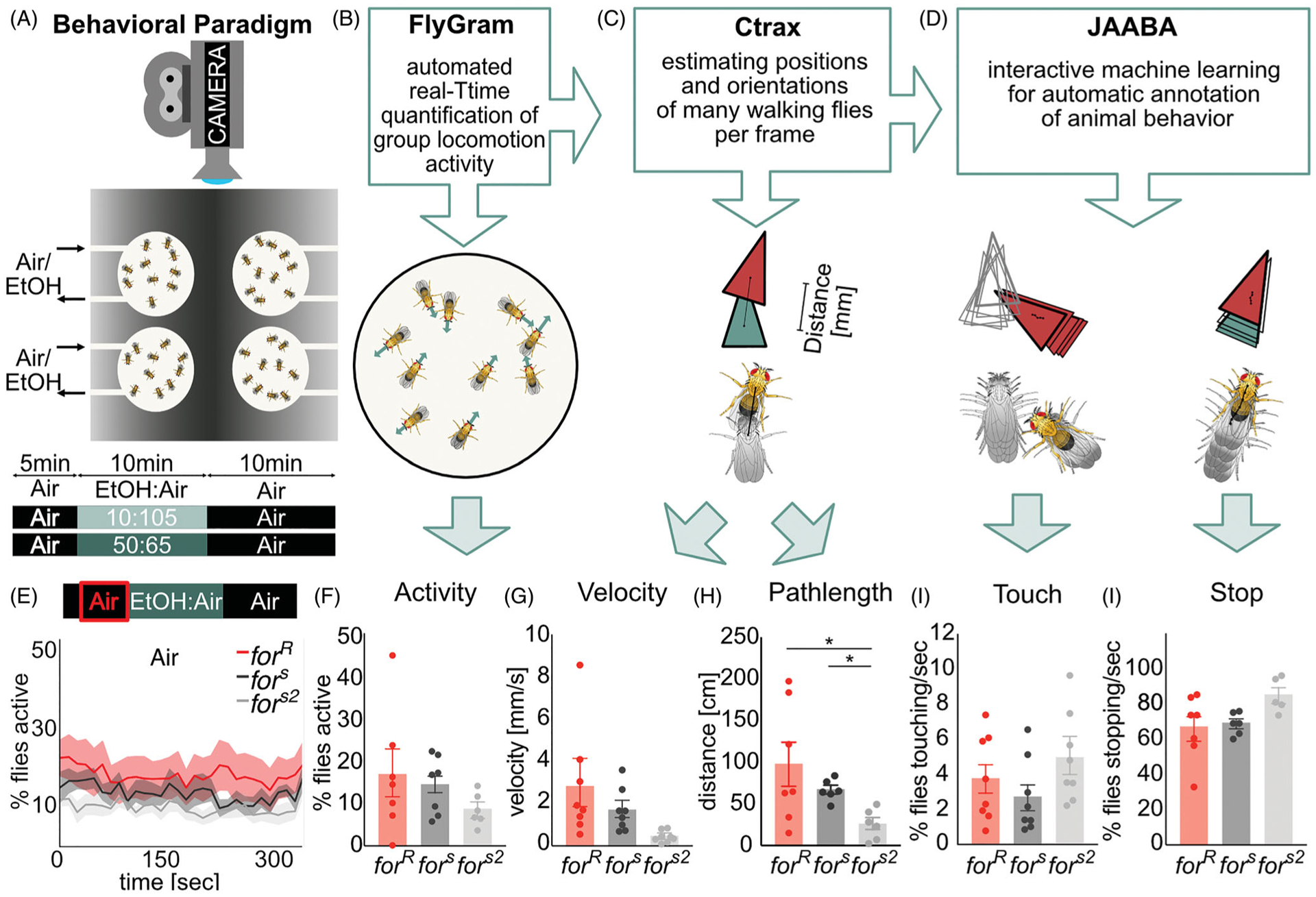

In order to analyze the ethanol-induced changes in activity, we used a video based behavioral apparatus and software that enables an automatic quantification of group locomotion activity in Drosophila (Scaplen et al., 2019) (Figure 1(A)). The fly Group Activity Monitor (FlyGrAM) consists of four circular arenas that are all individually connected to an air and vacuum source to allow for a constant airflow (Figure 1(A,B). Each arena is 37 mm diameter, 2.5 mm tall, and covered with a clear acrylic sheet allowing the flies to walk freely in the arena, but preventing them from flying. Ten male flies (fors, forR or fors2) were placed in each circular arena and placed at 24 °C for 10 min to provide time for flies to adapt to the arena environment. Next, the arena with the flies was placed in the tracking apparatus, and flies were provided a constant humidified airflow of 115 units (~1856 ml/min for four arenas, thus ~466 ml/min per arena) for 15 min, which allowed their locomotion to decrease to a stable baseline (Figure 1(A)).

Ten flies were gently placed via mouth pipette into each arena, and initially provided humidified airflow for five minutes to gain a measurement of baseline activity. Subsequently, vaporized ethanol was introduced to the flies in the arena by changing the gas flow-through to a mix of ethanol:air ratio (high concentration: 50:65, low concentration: 10:105) for 10 min. Finally, the airflow was shifted back to 100% air for 10 min (Figure 1(A)). The group activity of the flies are automatically recorded for the entire duration (Scaplen et al., 2019). Each experiment was replicated 8 times (n=8 comprises 8 groups of 10 flies per group, thus 80 flies). In order to ensure no strain-specific effects were due to a single arena and no spatial bias of placement within the apparatus, the strains tested were counterbalanced across arenas. Experiments were run at a steady temperature around 24 °C ± 1.5 °C in a dark chamber to reduce the influence of visual cues on group activity.

High content tracking

FlyGrAM videos were analyzed using Ctrax (Branson, Robie, Bender, Perona, & Dickinson, 2009) to extract information about individual flies’ position, orientation and trajectories (Figure 1(B)). The output of Ctrax tracking is an ellipse fit to each fly within an arena throughout the experiment. It is defined by the centroid, the fly’s orientation as well as the length of two body axis, the minor and major body axis, needed for the calculation of the perframe features. For example, velocity is defined as the speed of the center of rotation, being the point on the fly that translates the least from one frame to the next. The velocity is calculated by the magnitude of the vector between the fly’s center of rotation in frames t − 1 to t, normalized by the frame rate (Branson et al., 2009). This allowed us to gain information about the velocity of the flies per frame. Total distance travelled (pathlength) before, during and after ethanol exposures was calculated as the integral of speed, i.e. summing the perframe (30fps) velocities (mm/s) measured during 5 min. JAABA Classifiers (Kabra, Robie, Rivera-Alba, Branson, & Branson, 2013) were trained on the Ctrax perframe features to gain information about specific social and locomotion behaviors: Touch and Stop (Figure 1(C)). The JAABA learning algorithm is fed with specific pre-defined behavioral classifiers in order to scan across all frames for the classified behavior. In this study we made use of the existing classifiers for stopping and touching behavior introduced by Branson and colleagues (Kabra et al., 2013). To further analyze the effect of ethanol on these behavioral features, the data was split into 4 phases each lasting 5 min, baseline (0–5min), early ethanol (5–10min), late ethanol (10–15min) and recovery (15–20min). The Stop and Touch data was normalized to the baseline behavior to detect changes in these features caused by alcohol exposure.

Memory for cues associated with alcohol intoxication

To test whether for affected the ability to associate a cue with ethanol, we exposed forR, fors and fors2 flies to two consecutive odor cues (1:36 isoamyl alcohol or ethyl acetate in mineral oil) with the second odor paired with an intoxicating dose of 60% ethanol vapor (90:60 ethanol:air) (Kaun, Azanchi, Maung, Hirsh, & Heberlein, 2011; Nunez, Azanchi, & Kaun, 2018). Flies were exposed to 10 min of the first odor followed by 10 min of the second odor, which is paired with 60% ethanol vapor. Flies were trained three times with 50 min breaks between each session. Flies were placed in perforated 14 ml canonical tubes with mesh lids, and placed in 30cm×15cm×15cm training boxes with passive vacuum while being exposed to odors and ethanol vapor. To avoid a naïve odor bias, reciprocal odor controls were run simultaneously. 30 min or 24 h after training, flies were given a choice between unpaired and paired odors in a Y-maze (Nunez et al., 2018) (Figure 6(A)). A preference index was calculated by subtracting the number of flies entering the unpaired odor vial from the paired odor vial, and dividing this number by the total number of flies tested (Kaun et al., 2011). A conditioned preference index was calculated by averaging the preference index of the two reciprocal training sessions. 60 flies were used for each N=1, 30 flies for each reciprocal conditioning. N=20–26 for each strain per condition.

Alcohol metabolism

To investigate how the different for strains absorb and metabolize alcohol, we exposed flies to 60% vaporized ethanol (90:60 ethanol:air) for 10 min and measured internal ethanol concentration immediately after or 30 min after ethanol exposure. The internal ethanol concentrations were determined from whole fly homogenates of 50 flies per sample (Kaun et al., 2011). To measure the ethanol concentration, flies were first flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then homogenized in 500 μl Tris-HCL (50 mM, pH 7.5, Sigma), followed by centrifugation at 4 °C at 14000 r.p.m. for 20 min. Next, the ethanol concentration of the supernatant was measured using an alcohol dehydrogenase-based spectrophotometric assay (Ethanol Assay Kit 229–29, Diagnostic Chemicals) (Figure 7(A)). To set this data in relation and thereby calculate the fly internal ethanol level, the flies volume was set to ~2 μl (Berger et al., 2008).

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis the locomotion activity data were split in four phases, baseline (0–300 s), early ethanol (300–600 s), late ethanol (600–900 s), and recovery (900–1200s). All early ethanol, late ethanol and recovery data was normalized to baseline. Data for activity, velocity, touch and stop for each phase was averaged and analysed. Due to low sample size (n=8) in behavior tracking experiments, we used more conservative non-parametric tests for the statistical analysis. This increased rigor, ensured consistency in analyses, and allowed for easier comparisons between experiments. For comparisons between the three non-paired strains, a Kruskal Wallis test followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons was performed. In order to analyze changes in behavior of each strain over time (paired data), a Friedmann test followed by paired Wilcoxon multiple comparisons was performed (n.s.=p > 0.05, *=p < 0.05, **=p < 0.01, ***=p > 0.001, **** p < 0.0001). The statistical analysis was performed in PRISM 7 (GraphPad).

Results

foraging does not affect open field behavior in the absence of a stimulus

We first tested whether rovers (forR), sitters (fors) and sitter mutants with a rover background (fors2) differ in spontaneous behavior in an open field arena without an ethanol stimulus, which we termed ‘baseline’ (Figure 1(A,B)). We found all for strains showed the same levels of group activity (H(3, 24)=0.29, p=0.8) (Figure 1(E,F)), velocity (H(3, 24)=4.63, p=0.1 (Figure 1(G)), touching (H(3, 24)=0.08, p=0.9) (Figure 1(I)) and stopping (H(3, 24)=0.4, p=0.8) (Figure 1(J)). The pathlength of fors2 flies was significantly shorter compared to fors and forR (Figure 1(H)) (H(3, 24)=7.88, p=0.01). In general, flies showed a high percentage of stopping behavior (70%, Figure 1(J)), and only around 4% of the flies in each arena interacted with each other (Figure 1(I)).

Figure 1.

for does not affect spontaneous open field behavior. (A) The flyGrAM arena consists of 4 circular arenas each filled with 10 flies of different strains. Flies were tracked while being given humidified air for 5 min, ethanol for 10 min, then humidified air for 5 min. (B) Group activity within each arena was analyzed with the FlyGrAM software while recording the flies during the behavioral paradigm. (C) Ctrax was used to estimate the position and orientation of the 10 flies in each arena per frame. (D) The interactive machine learning for automatic annotation of animal behavior (JAABA) was fed per-frame feature information from Ctrax to reveal information about social interaction of the flies. (E-J) Plots depict mean ± standard error. The spontaneous activity levels of flies given humidified air remain at ~15% and show no significant difference between strains. (G) Velocity of flies given humidified air for 5 min is between 1–3mm/s with no significant difference between strains. (H) Flies cover distances between 30–100cm in five minutes, with no significant differences between strains. (I) Less than 5% of the flies touch per second when given humidified air, with no significant differences between strains. (J) More than 60% of the flies show stopping behavior per second when given humidified air, with no significant differences between strains.

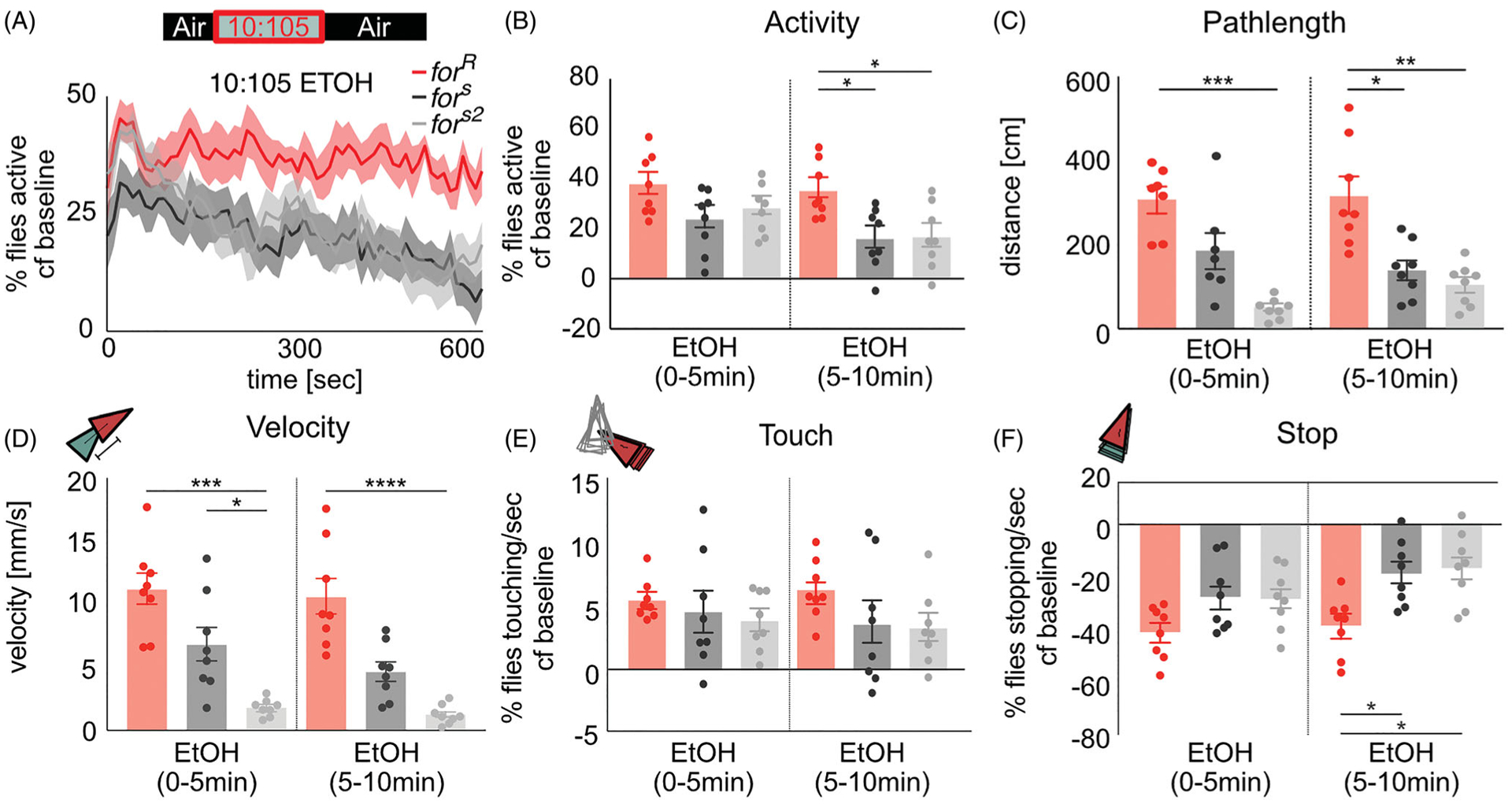

foraging affects locomotion in response to an ethanol odor

We then looked at whether for elicited foraging behavior in response to a non-intoxicating ethanol dose similar to that found in fermenting fruit (Levey, 2004). When the flies were exposed to a non-intoxicating 10 min exposure of 10:105 ethanol:air ratio, the percent of flies’ activity increased to up to 40% in forR flies (p=0.008) and only 25% in fors (p=0.008) and fors2 (p=0.008) flies compared to baseline activity levels (Figure 2(A)). forR flies demonstrated an increased group activity throughout the 10-min ethanol exposure whereas fors and fors2 flies steadily decreased activity over time, resulting in a significantly lower activity at the end of ethanol exposure compared to forR flies (H(3,24)=7.96, p 0.02, forR vs fors (p=0.01), forR vs fors2 (p=0.02)) (Figure 2(B)). Rovers travelled significantly longer distances during low dose ethanol exposure compared to sitters (0–5 min: H(3,24)=13.92, p < 0.0001, forR vs fors2 (p=0.0006), 5–10min: H(3,24)=13.72, p=0.0011, forR vs fors (p=0.02), forR vs fors2 (p=0.001)) (Figure 2(C)). forR flies also show a significantly higher velocity over the time of low dose ethanol exposure compared to fors and fors2 flies (H(3,24)=18, p=0.0001, forR vs fors (p=0.002), forR vs fors2 (p < 0.0001)) (Figure 2(D)). Our values are comparable to a previous study that reported in the presence of food rovers walked 36.17 cm/30 s (361.7 cm/5 min), and sitters walked 17.38 cm/30 s (173.8 cm/5 min), suggesting that the low dose ethanol here represents a food-like odor to the fly (Levey, 2004; Pereira & Sokolowski, 1993).

Figure 2.

for affects activity in response to ethanol odor. (A,B) During the period of low-dose ethanol exposure, the activity for fors and fors2 decreased, whereas the activity level of forR stayed the same. (C) forR traveled significantly longer distances during low dose ethanol exposure compared to fors and fors2 flies. (D) forR showed a significantly higher velocity compared to fors and fors2 flies. (E,F) Touching behavior increased for all strains compared to open field behavior whereas stopping behavior significantly decreased to less than 60% of the flies stopping per second. forR stopped significantly less than fors and fors2 flies. Plots depict mean ± standard error n.s.=p > 0.05, *=p < 0.05, **=p < 0.01, ***=p > 0.001, ****=p < 0.0001.

Ethanol odor increased touching (forR (p=0.008), fors (p=0.02), fors2 (p=0.04)) and decreased stopping (forR (p=0.008), fors (p=0.008), fors2 (p=0.008)) in all strains (Figure 2(E,F)). for did not significantly affect touching (H(3, 24)=1.665, p=0.43) (Figure 2(E)). However, rovers stopped significantly more than sitters after five minutes of ethanol exposure (H(3,24)=9.38, p=0.009, forR vs fors (p=0.03), forR vs fors (p=0.02)) (Figure 2(F)).

foraging does not affect behavior post-ethanol odor stimulus

We hypothesized that once the ethanol odor stimulus was removed, all strains would recover to baseline behavior, resulting in no differences in behavioral measures between the three for strains. As predicted, there were no significant differences in group activity between rovers and sitters (Figure 3(A)) (forR vs fors (p=0.06), forR vs fors2 (p > 0.99)). Although there was a reduction in pathlength (H(2,24)=15.7, p=0.0004), and velocity (H(3, 24)=15.61, p=0.0004) in fors2 flies, and in stopping in fors flies (H(3, 24)=9.97, p=0.007), there were no consistent significant differences between forR and the two sitter strains in any of the metrics reported, so we do not attribute these differences to variation in for (Figure 3(A–F)). There were no significant differences in touching between the three strains (H(3, 24)=3.55, p=0.17) (Figure 3(E)).

Figure 3.

for does not affect recovery from ethanol odor exposure. (A,B) During presentation of humidified air following exposure to low-dose ethanol, the group activity returned to baseline activity with ~300 s, with no significant differences between strains. (C) The total distance travelled (pathlength) after low-dose ethanol exposure returns to baseline behavior in forR and fors2 flies, whereas fors flies still show an increase pathlength compared to baseline. (D) The velocity after low-dose ethanol exposure returns to baseline behavior in forR and fors2 flies, whereas fors flies still show an increase velocity compared to baseline. (E,F) Touch and Stop behavior recover within minutes of humidified air post ethanol odor. fors flies demonstrate less stopping than both forR and fors2 flies. Since there were no consistent differences between rovers and the two sitter strains in any of the metrics reported, we do not attribute these behavioral differences to variation in for. Plots depict mean ± standard error n.s.=p > 0.05, *=p < 0.05, **=p < 0.01, ***=p > 0.001, ****=p < 0.0001.

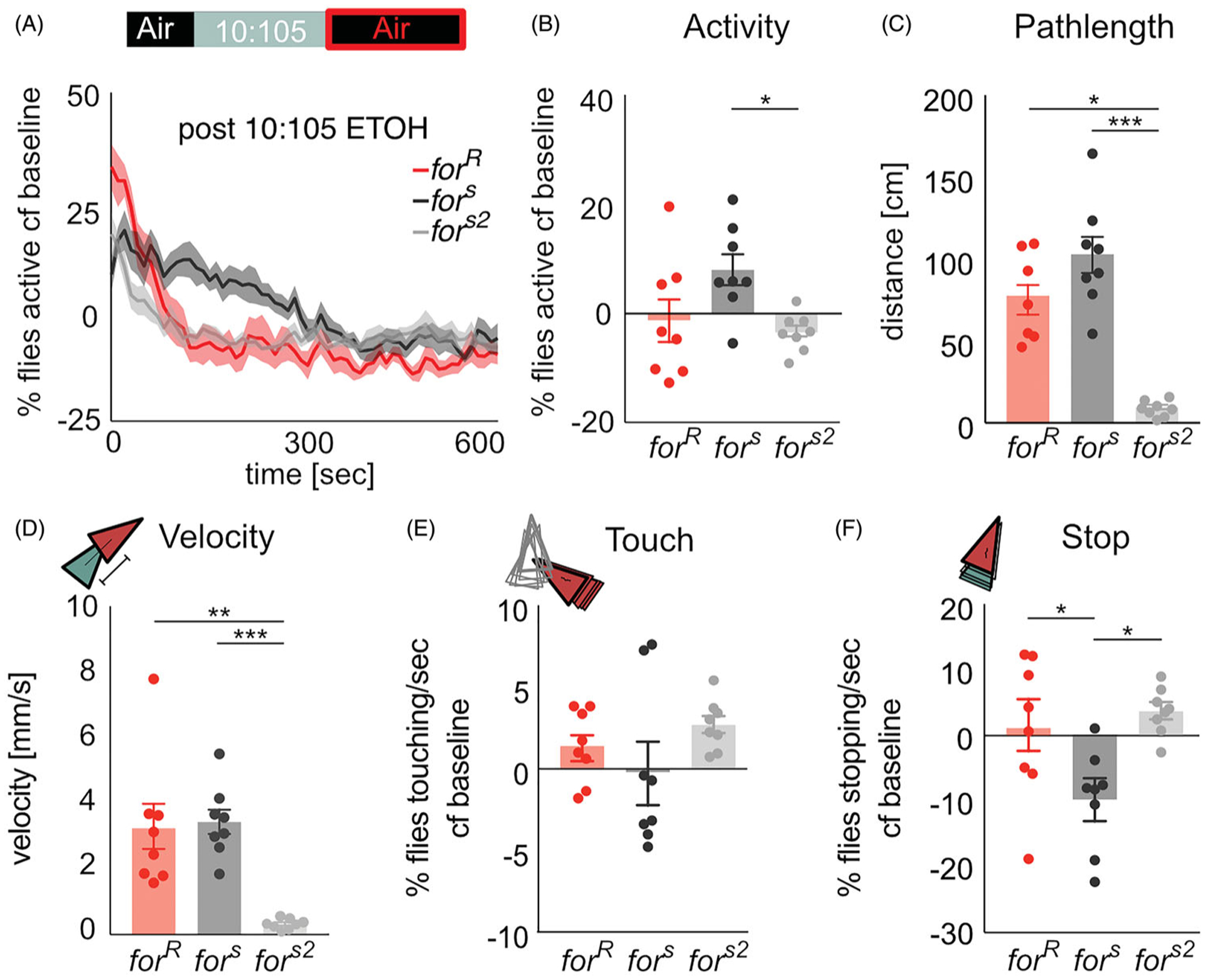

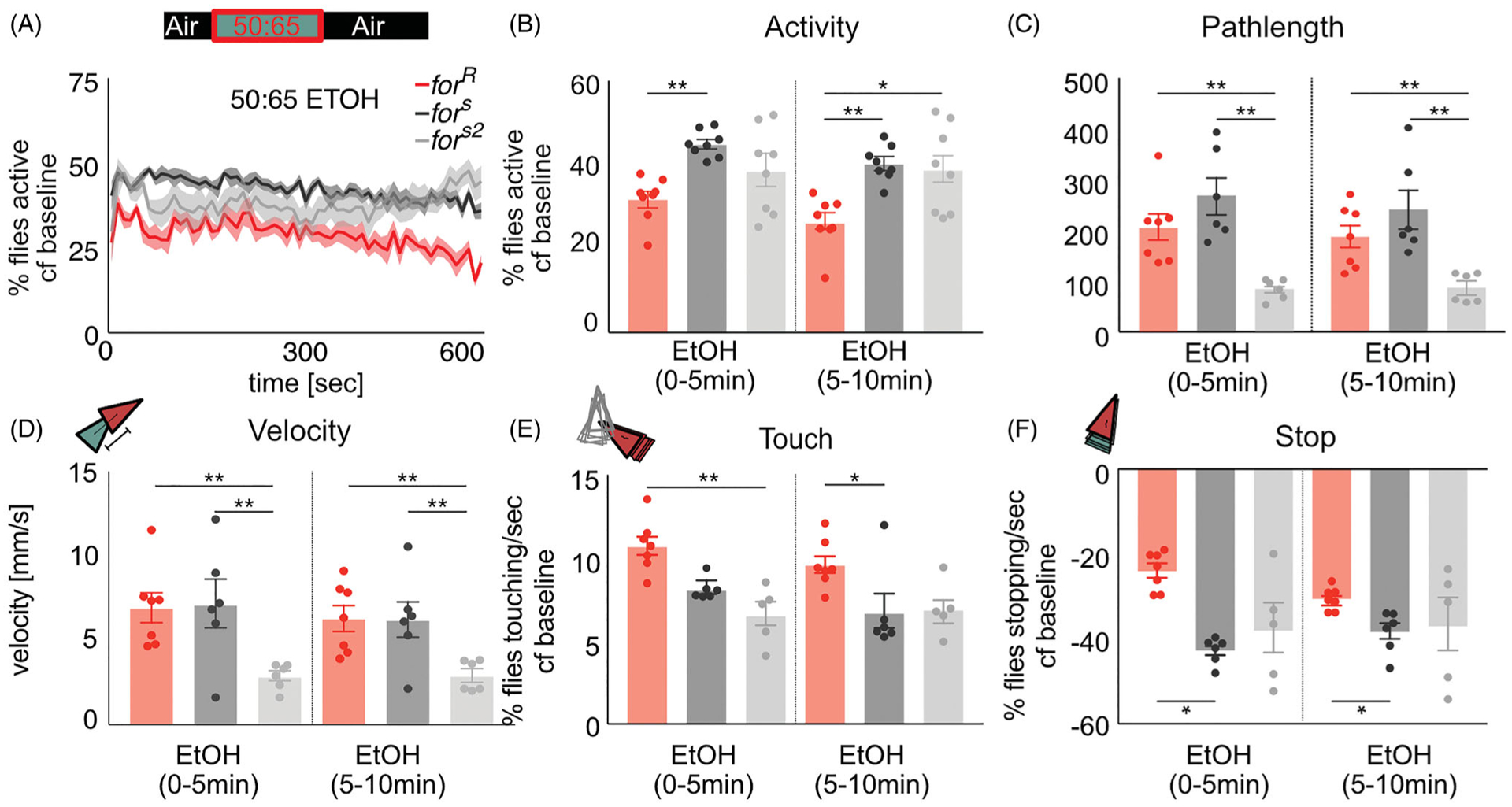

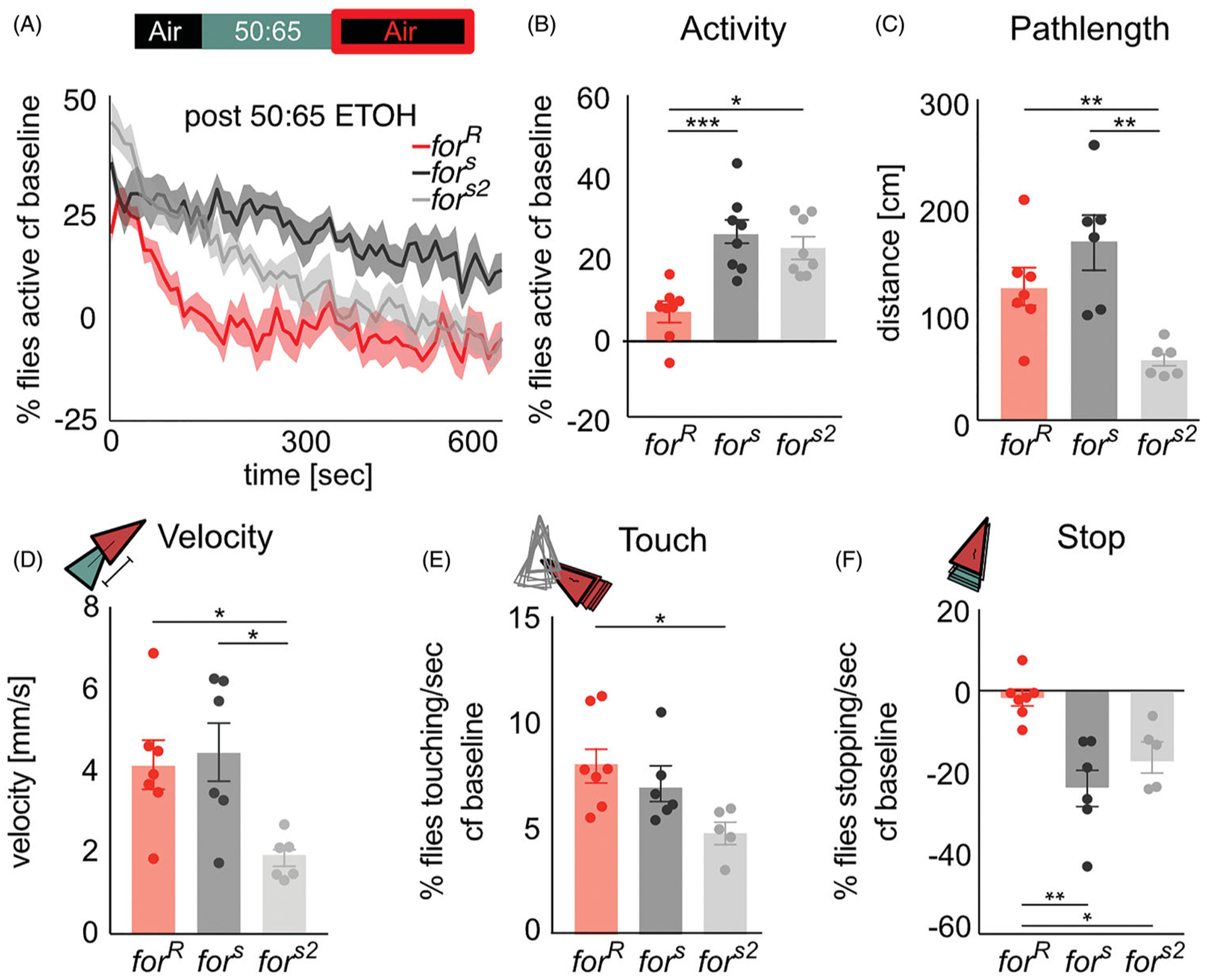

foraging affects ethanol-induced increases in locomotion

We next investigated how variants of for affected these behavioral metrics in response to a dose of ethanol that typically induces sustained increases in locomotor activity (Scaplen et al., 2019), by exposing the flies to a 50:65 ethanol:air mixture (43% ethanol vapor) for 10 min. Sitter strains increased group activity by 40% (fors (p=0.008), fors2 (p=0.008) whereas rovers only showed 30% activity increase (forR (p=0.02) compared to baseline (Figure 4(A)). During ethanol exposure, forR flies showed a significantly lower activity than sitters (H(3, 19)=10.9, p=0.004, for vs for (p=0.006), forR vs fors2 (p=0.04)) (Figure 4(B)). However, forR did not show significantly less distance moved (p > 0.9) or velocity (p > 0.9) compared to fors. fors2 flies showed significantly reduced pathlength (H(3,19)=12.33, p=0.0002) and velocity compared to fors and forR flies (H(3,19)=9.47, p=0.004), but since forR flies did not differ from both sitter strains, we do not attribute these differences to variation in for.

Figure 4.

for affects behavioral sensitivity to the pharmacological properties of ethanol. (A) The percent activity in response to a high dose of ethanol increases to ~35% for rovers and ~ 45% for sitters. (B) During high dose ethanol exposure the group activity of forR is significantly lower than fors and fors2 flies. (C) fors2 flies move a significantly smaller distance than forR and fors flies. (D) fors2 flies are significantly slower than forR and fors flies. (E,F) All strains showed increased touching and decreased stopping during high-dose ethanol exposure. (E) forR showed significantly more touching than fors2 in the first 5 min of ethanol exposure, and significantly more touching than fors in the second 5 min of ethanol exposure. (F) forR showed significantly more stopping than fors flies throughout high dose ethanol exposure. Plots depict mean ± standard error. n.s.=p > 0.05, *=p < 0.05, **=p < 0.01, ***=p > 0.001, ****=p < 0.0001.

This dose of ethanol increased touching (forR (p=0.02), fors (p=0.03), fors2 (p=0.04)) (Figure 4(E)) and decreased stopping (forR (p=0.03), fors (p=0.03), fors2 (p=0.04)) in all strains (Figure 4(F)). During early ethanol exposure, forR flies showed significantly more touching (H(3, 19)=12.19, p=0.0002) than for (p=0.002), whereas this effect trended towards significance with fors (p=0.06). In contrast, forR flies showed significantly more touching (H(3, 19)=6.53, p=0.03) than fors (p=0.04) but not fors2 (p=0.2) during late ethanol exposure (Figure 4(E)). forR flies showed significantly more stopping (H(3,19)=9.17, p 0.005) than fors (p=0.01, p=0.04) but not fors2 (p=0.1, p=0.9) flies during early and late high-dose ethanol exposure (Figure 4(E)).

foraging affects recovery from the pharmacological properties of ethanol

We hypothesized that since for affected the percent of flies active during ethanol intoxication, it may also affect recovery from the pharmacological properties of ethanol. Indeed, significantly fewer rover flies were active compared to sitters after the offset of ethanol (H(3, 19)=14.22, p=0.0008, for vs fors (p=0.0009), forR vs fors2 (p=0.02)) (Figure 5(A,B)). However, forR flies moved significantly more distance than fors2 flies (p=0.04) but not fors flies (p > 0.9) (Figure 5(C)). forR pathlengths returned to baseline within 5 min of recovery (p=0.4), which was not the case for fors (p=0.03) or fors2 (p=0.03). Similarly, forR flies moved significantly faster than fors2 flies (p=0.03) but not fors flies (p > 0.9) (Figure 5(D)). These activity and locomotion metrics suggest that the 50:65 ethanol:air dose did not sedate the flies, and that rovers recover from the pharmacological properties of ethanol faster than sitters.

Figure 5.

for affects recovery from the pharmacological properties of ethanol. (A) During exposure to humidified air following an intoxicating dose of ethanol, fly activity decreases more rapidly in forR than in fors or fors2 flies. (B) Significantly fewer forR flies were active compared to fors and fors2 flies. (C) There is significantly reduced (C) pathlength and (D) velocity in fors2 flies compared to forR and fors flies (E) Touching behavior remained higher than baseline levels for all strains, and was statistically reduced in fors2 compared to forR flies (F) forR stopping behavior returned to baseline levels whereas fors and fors2 flies continued to show significantly less stopping compared to baseline. Plots depict mean ± standard error. n.s.=p > 0.05, *=p < 0.05, **=p < 0.01, ***=p > 0.001, ****=p < 0.0001.

Touching behavior remained higher than baseline levels for all strains (forR (p=0.02), fors (p=0.03), fors2 (p=0.04)), and was significantly greater in forR flies than fors2 (p=0.01) but not fors flies (p > 0.9) (Figure 5(E)). forR flies stopping behavior returned to baseline levels (p=0.6) whereas fors (p=0.03) and fors2 (p=0.03) flies continued to show significantly less stopping compared to baseline (Figure 5(F)). forR flies showed significantly more stops H(3, 19)=11.93, P=0.0002) than fors (p=0.003) and fors2 (p=0.04) flies (Figure 5(F)).

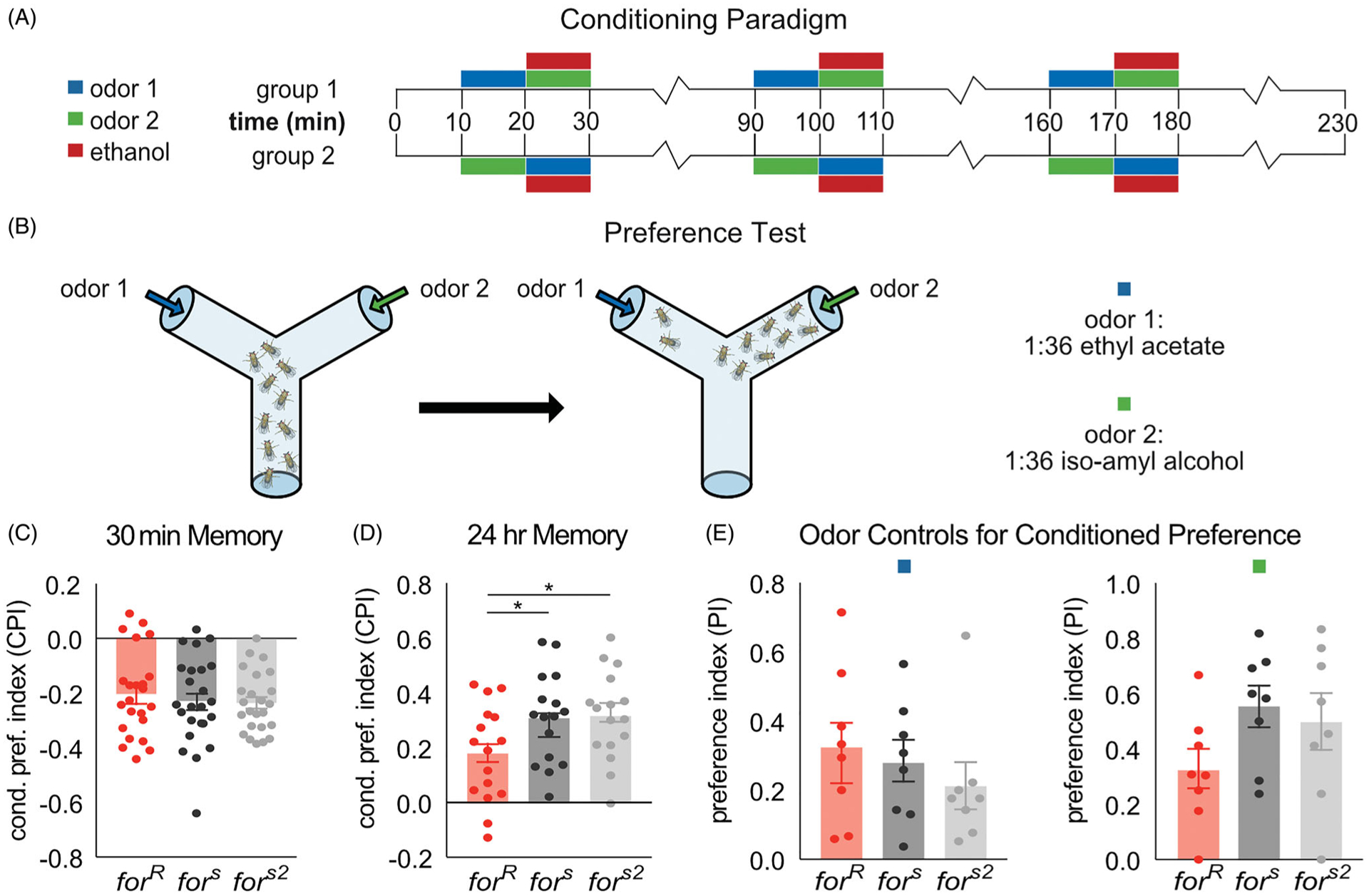

foraging affects reward memory for a cue associated with ethanol

We next hypothesized that the alcohol behavioral sensitivity differences between rovers and sitters would influence how for affects memory for an odor cue associated with ethanol (Figure 6(A,B)). Typically flies demonstrate aversive memory for ethanol when tested within 9 h after training, and an appetitive memory when tested 15 h or more after training (Kaun et al., 2011). Since for has been shown to affect both short-term and long-term memory, we hypothesized that forR would show increased 30-min aversive memory and reduced 24-h appetitive memory compared to fors and fors2. No statistical differences were found between strains when flies were tested 30 min after training (H(3,71)=0.63, p=0.73) (Figure 1(C)). However, 24 h after training, forR flies show reduced memory for ethanol compared to fors and fors2 flies (H(3,71)=10.27, p=0.006, forR vs fors (p=0.03), forR vs fors2 (p=0.002)) (Figure 1(D)). No statistical differences were identified in the ability of the strains to smell the odors used in the conditioning assay (IAA(H(3,24)=3.79, p=0.15), EA(H(3,24)=1.28, p=0.53)) (Figure 1(E)).

Figure 6.

for affects memory for ethanol reward. (A) Flies received 3 training sessions with a 10 min exposure to one odor followed by a 10 min exposure to a second odor paired with 60% ethanol vapor. Training trials were spaced by 1 h. A reciprocal group, in which the opposite odor was paired with ethanol, was run. (B) After the training flies were given the choice of the two odors. A preference index was calculated by subtracting the number of flies entering the Odor− vial from the Odor + vial and dividing this number by the total number of flies. Conditioned preference index was calculated by averaging the preference indexes of the two reciprocal groups. (C) for does not affect conditioned aversion tested 30 min after training. (D) for affects conditioned preference tested 24 h after training. forR flies show decreased memory for ethanol reward compared to fors and fors2 flies. (E) for does not significantly affect preference for the odors used in the conditioning procedure. Plots depict mean ± standard error. n.s.=p > 0.05, *=p < 0.05, **=p < 0.01, ***=p > 0.001, ****=p < 0.0001.

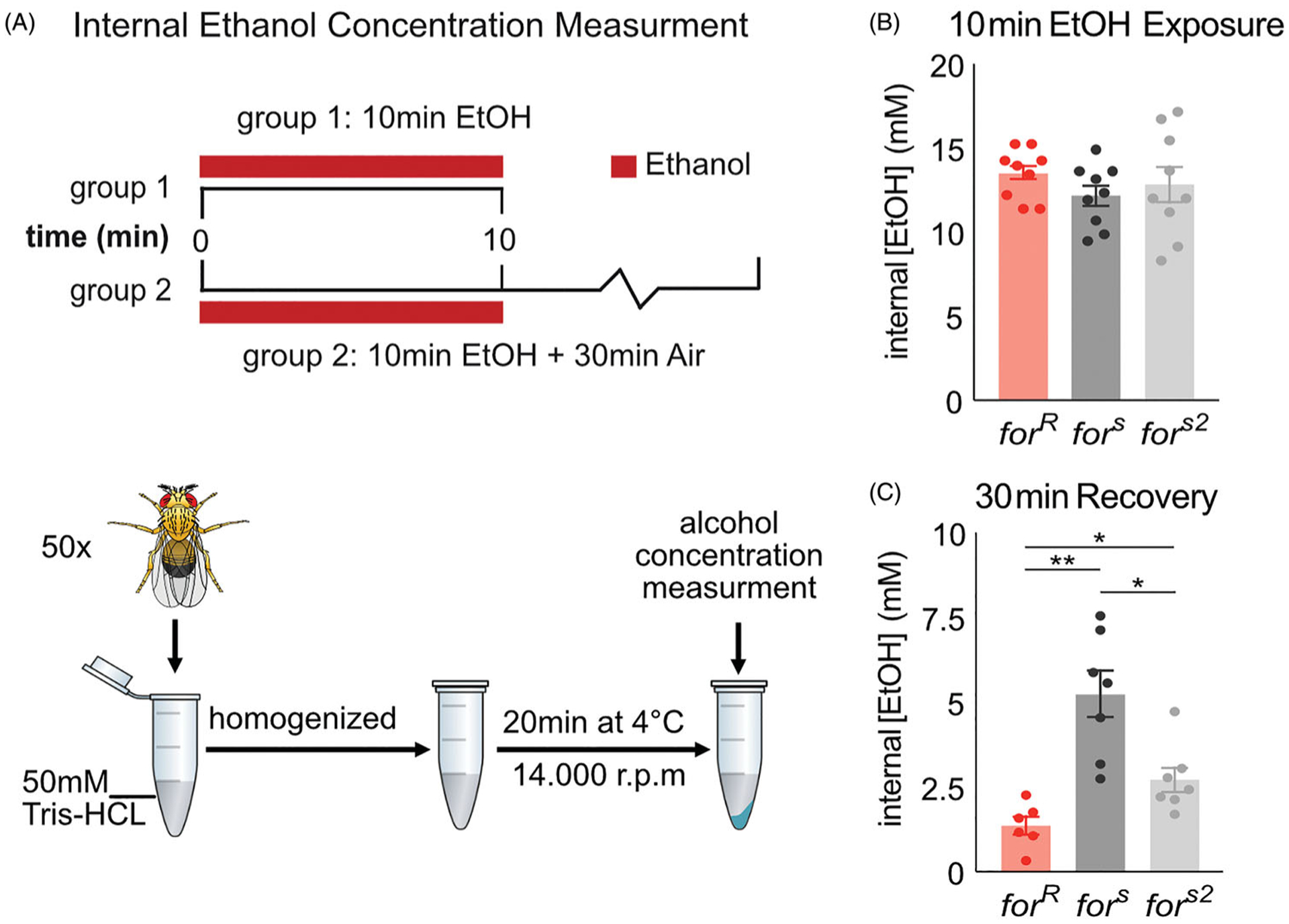

foraging affects ethanol metabolism

Since for affects a number of metabolic phenotypes (Allen et al., 2018; Kaun et al., 2007; Kaun et al., 2008) we hypothesized that the observed behavioral differences between rovers and sitters may stem from the ability to metabolize ethanol differently. Therefore, we tested the internal ethanol levels right after ethanol exposure and after 30 min of recovery. We found that forR flies absorb ethanol at the similar rate (H(3,27)=1.87, p=0.39) (Figure 7(B)), but metabolize ethanol faster than fors and fors2 flies (F(3,20)=13.6, p < 0.0001, forR vs fors (p=0.003), forR vs fors2 (p=0.02)) (Figure 7(C)).

Figure 7.

for affects ethanol metabolism. (A) Flies received a 10 min exposure to 60% ethanol in perforated vials in the training boxes used for ethanol memory. Flies from Group One were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, flies from group two are exposed to air for another 30 min. Ethanol concentrations in supernatants were measured using an alcohol dehydrogenase–based spectrophotometric assay. To calculate fly internal ethanol concentration, the volume of one fly was estimated to be ?2 ?l. (B) for does not affect ethanol absorption. (C) for affects rate of recovery from ethanol exposure. forR flies metabolize ethanol faster than fors and fors2 flies. Plots depict mean ± standard error. n.s.=p > 0.05, *=p < 0.05, **=p < 0.01, ***=p > 0.001, ****=p < 0.0001.

Discussion

We found that for affects alcohol induced locomotion (pathlength, velocity, percent activity, and stopping), cue-associated memory for the intoxicating properties of ethanol, and ethanol metabolism. We first recapitulated previously published work demonstrating that rovers move more than sitters in response to a food stimulus. Rovers showed significantly longer pathlength and moved faster compared to the sitter strains in response to a low-dose ethanol odor. This is consistent with previous work describing how rovers walk longer distances while searching for food whereas sitters tend to stay at one food source once they find it (de Belle & Sokolowski, 1987).

In contrast to these ethologically-relevant ethanol odor responses, we found that a pharmacologically-relevant ethanol concentration induces a sustained increase in the number of flies active within a group of sitters, but not rovers. However, rovers move similar distances and at the same speed as sitters under these conditions and stop less than sitters. This suggests that sitters are more sensitive than rovers to pharmacologically relevant stimulating doses of ethanol. This behavioral phenotype is consistent with the slower return to baseline levels after removal of an ethanol stimulus, and with a slower metabolism of ethanol in sitters.

Here we also showed that the foraging gene affects memory for the intoxicating properties of ethanol, since rovers show reduced preference for an ethanol associated odor cue 24 h after the association. This is consistent with known roles of for in learning and memory. Rover larvae are better able to acquire and remember three but not eight odor-sucrose pairings compared to sitter larvae (Kaun et al., 2007). Similarly, adult rover flies have better short-term olfactory memory, but worse long-term olfactory memory than sitters (Mery et al., 2007). This phenotypic difference is also seen in visual learning paradigms and is conserved in mammals (Feil et al., 2003; Paul et al., 2008). Rovers also show higher retroactive interference, which occurs when the retrieval of previously learned information is less available owing to the acquisition of recently acquired information (Kuntz et al., 2012; Reaume et al., 2011; Z. Wang et al., 2008).

In the case of ethanol reward memory in Drosophila, we speculate that the difference in ethanol sensitivity between for strains alters perception of the intoxicating experience, causing reward to be processed differently in rovers and sitters. This may explain why for does not affect aversive short-term memory for ethanol, as this type of memory is not dependent on intoxicating concentrations of ethanol (Nunez et al., 2018). Since for affects sensitivity to sucrose and other food substances, altering perception of the reward stimulus may be a more general mechanism through which PKG influences alcohol preference (Hughson et al., 2018; Kent et al., 2009). Alternatively, as for also affects alcohol-induced increases in activity, this change in behavior could be affecting memory acquisition independent of reward perception. In support of this, for would not likely affect the behavioral choice during the memory test since the flies are no longer intoxicated during odor choice (Figure 6(A)) and for does not appear to significantly affect preference for the odors used (Figure 6(E)).

Ethanol sensitivity has been associated with greater consumption and risk for developing an AUD (Schuckit, 2018; King, McNamara, Hasin, & Cao, 2014; Piasecki et al., 2012). In humans and rodents, sensitivity to the effects of alcohol intoxication is partially influenced by genes, and reduced sensitivity predicts the development of AUD (Crabbe, Belknap, & Buck, 1994; Schuckit, 1994a, 1994b). Thus, both heightened alcohol stimulation and reward sensitivity, and lower sensitivity to alcohol sedation robustly predicts more AUD symptoms over time in humans (King et al., 2014; Schuckit, 1994b). Studies in Drosophila recapitulate this, where genes influence the level of response to an intoxicating dose of ethanol (Kong et al., 2010; Morozova et al., 2009, Morozova, Anholt, & Mackay, 2007; Scholz, Ramond, Singh, & Heberlein, 2000; Singh & Heberlein, 2000). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for alcohol sensitivity using the sequenced, inbred lines of the Drosophila genetic reference panel (DGRP) together with quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping in an advanced intercross out-bred population derived from sensitive and resistant DGRP lines, revealed 247 candidate genes affecting alcohol sensitivity, 58 of which, including the foraging gene, form a genetic interaction network (Morozova et al., 2015).

Notably, our work did not demonstrate a consistent effect of for on touching. Although we observed a small trend where rovers demonstrated increased touching compared to sitters in the high-ethanol context (Figure 4(E)), this trend was not observed in any other behavioral contexts. Relatedly, for affected locomotion in the presence of a food odor in a similar way in our group assay as it did when flies are isolated in previously published studies (J Steven de Belle & Sokolowski, 1987; Pereira & Sokolowski, 1993). Our lack of findings here was surprising as for affects social behaviors including aggregation behavior (Philippe et al., 2016) and aggression (S. Wang & Sokolowski, 2017), and influences behaviors that are dependent on a social context such as olfactory learning (Kohn et al., 2013), and oviposition (McConnell & Fitzpatrick, 2017), Similarly, for orthologues influence social behaviors in other taxa including bees (Ben-Shahar, Robichon, Sokolowski, & Robinson, 2002, Ben-Shahar, Leung, Pak, Sokolowski, & Robinson, 2003; George, Bröger, Thamm, Brockmann, & Scheiner, 2020), wasps (Wenseleers et al., 2008) and ants (Ingram, Oefner, & Gordon, 2005; Lucas & Sokolowski, 2009). Our results failed to demonstrate an observed decrease in social dynamics in rovers compared to sitters that was recently observed in a similar assay (Alwash, Allen, Sokolowski, & Levine, 2021) We speculate that sensory cues necessary for spontaneous social behaviors may have been obscured in our paradigm by a constant flow of hydrated air or odors through the behavioral chambers. This suggests that our behavioral paradigm was not optimal for identifying how for affected social behavior, or how social context could influence for-dependent behaviors.

Taken together, the work here contributes to a mechanistic understanding of alcohol sensitivity as indication for AUD by demonstrating how natural variation in metabolic phenotypes can impact behavioral response to an addictive substance. Our data predict that variants of for with lower PKG activity in other species will show increased ethanol sensitivity, and increased lasting ethanol preference. This is consistent with results on the role of PKG in ethanol-induced behaviors from rodent models, suggesting the effects of PKG on alcohol behaviors are highly conserved. cGMP-dependent protein kinase type II (cGKII) knockout mice showed elevated alcohol preference in a 2-bottle free choice test (Werner et al., 2004), demonstrating that reduction in PKG is associated with increased alcohol preference in both mice and flies. Moreover, cGMP activates nitric oxide, which inhibits dopamine release in the striatum in rats resulting in decreasing reward response for alcohol (Guevara-Guzman et al., 1994; Romieu et al., 2008). These studies are consistent with rovers showing decreased ethanol preference, as they have higher PKG activity than sitters. Whether this is the mechanism through which variation in PRKG1 increases risk for alcohol abuse in humans remains to be seen (Hawn et al., 2018; Polimanti et al., 2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Ulrike Heberlein (Janelia Research Campus) for helpful early discussions about the alcohol-associated preference and metabolism data. Thanks to Dr. Kristin Branson (Janelia Research Campus), Dr. Alice Robie (Janelia Research Campus), Dr. Mayank Kabra (Janelia Research Campus) and members of the Ctrax and JAABA google groups for ongoing assistance with Ctrax and JAABA. Thanks to members of the Kaun Lab and Dr. Kristin Scaplen (Bryant University) for providing helpful feedback on data visualization, analysis, and writing. Thanks to Dr. Marla Sokolowski (University of Toronto) for providing the for strains.

With gratitude to Dr. Marla Sokolowski: Thanks especially to Dr. Marla Sokolowski, whose guidance was integral to the conceptualization of this work. It is the people that we work with, including incredible mentors like Marla, that help shape us as scientists. Marla has been a huge inspiration to me (Karla), and more broadly an entire generation of behavioral geneticists. Her contributions have made an important and indelible mark on the field. I’m extremely grateful to her for her rigorous scientific training and continued patience, encouragement and immense knowledge. Marla is a lifelong mentor, and I consider myself incredibly fortunate to have the opportunity to conduct a study related to her research in my own lab. I’m delighted this work will join several other similar and relevant papers highlighting the important contributions of Marla in this special edition of Journal of Neurogenetics. This work was completed with immense gratitude to Marla, for setting the stage and making it possible for generations of scientists to use foraging as an example of how natural genetic variation affects behavior. We all thank-you Marla, for being the amazing mentor and scientist that you are.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health [R01AA024434 to K.R.K].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Acevedo SF, Peru y Colon de Portugal RL, Gonzalez DA, Rodan AR, & Rothenfluh A (2015). S6 kinase reflects and regulates ethanol-induced sedation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 35(46), 15396–15402. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1880-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen AM, Anreiter I, Vesterberg A, Douglas SJ, & Sokolowski MB (2018). Pleiotropy of the Drosophila melanogaster foraging gene on larval feeding-related traits. Journal of Neurogenetics, 32(3), 256–266. doi: 10.1080/01677063.2018.1500572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen AM, Anreiter I, Neville MC, & Sokolowski MB (2017). Feeding-related traits are affected by dosage of the foraging gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics, 205(2), 761–773. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.197939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwash N, Allen A, Sokolowski MB, & Levine J (2021). The Drosophila melanogaster foraging gene affects social networks. Journal of Neurogenetics. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anreiter I, Kramer JM, & Sokolowski MB (2017). Epigenetic mechanisms modulate differences in Drosophila foraging behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(47), 12518–12523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710770114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anreiter I, & Sokolowski MB (2018). Deciphering pleiotropy: How complex genes regulate behavior. Communicative & Integrative Biology, 11(2), 1–4. doi: 10.1080/19420889.2018.1447743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong GAB, López-Guerrero JJ, Dawson-Scully K, Peña F, & Robertson RM (2010). Inhibition of protein kinase G activity protects neonatal mouse respiratory network from hyperthermic and hypoxic stress. Brain Research, 1311, 64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley-Koch AE, Garrett ME, Gibson J, Liu Y, Dennis MF, Kimbrel NA, … Hauser MA (2015). Genome-wide association study of posttraumatic stress disorder in a cohort of Iraq–Afghanistan era veterans. Journal of Affective Disorders, 184, 225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belay AT, Scheiner R, So AK-C, Douglas SJ, Chakaborty-Chatterjee M, Levine JD, & Sokolowski MB (2007). The foraging gene of Drosophila melanogaster: Spatial-expression analysis and sucrose responsiveness. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 504(5), 570–582. doi: 10.1002/cne.21466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shahar Y, Leung H-T, Pak WL, Sokolowski MB, & Robinson GE (2003). cGMP-dependent changes in phototaxis: A possible role for the foraging gene in honey bee division of labor. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 206(Pt 14), 2507–2515. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shahar Y, Robichon A, Sokolowski MB, & Robinson GE (2002). Influence of gene action across different time scales on behavior. Science, 296(5568), 741–744. doi: 10.1126/science.1069911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger KH, Kong EC, Dubnau J, Tully T, Moore MS, & Heberlein U (2008). ethanol sensitivity and tolerance in long-term memory mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(5), 895–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00659.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branson K, Robie AA, Bender J, Perona P, & Dickinson MH (2009). High-throughput ethomics in large groups of Drosophila. Nature Methods, 6(6), 451–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JB, Boley N, Eisman R, May GE, Stoiber MH, Duff MO, … Celniker SE (2014). Diversity and dynamics of the Drosophila transcriptome. Nature, 512(7515), 393–399. doi: 10.1038/nature12962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts AR, Ojelade SA, Pronovost ED, Seguin A, Merrill CB, Rodan AR, & Rothenfluh A (2019). Altered actin filament dynamics in the Drosophila mushroom bodies lead to fast acquisition of alcohol consumption preference. The Journal of Neuroscience, 39(45), 8877–8884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0973-19.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camiletti AL, Awde DN, & Thompson GJ (2014). How flies respond to honey bee pheromone: The role of the foraging gene on reproductive response to queen mandibular pheromone. Die Naturwissenschaften, 101(1), 25–31. doi: 10.1007/s00114-013-1125-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan SL, Milton SL, & Dawson-Scully K (2013). A cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) controls synaptic transmission tolerance to acute oxidative stress at the Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction. Journal of Neurophysiology, 109(3), 649–658. doi: 10.1152/jn.00784.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claßen G, & Scholz H (2018). octopamine shifts the behavioral response from indecision to approach or aversion in Drosophila melanogaster. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, 131. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe J, Belknap J, & Buck K (1994). Genetic animal models of alcohol and drug abuse. Science, 264(5166), 1715–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.8209252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dason JS, Cheung A, Anreiter I, Montemurri VA, Allen AM, & Sokolowski MB (2020). Drosophila melanogaster foraging regulates a nociceptive-like escape behavior through a developmentally plastic sensory circuit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(38), 23286–23291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1820840116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-Scully K, Bukvic D, Chakaborty-Chatterjee M, Ferreira R, Milton SL, & Sokolowski MB (2010). Controlling anoxic tolerance in adult Drosophila via the cGMP-PKG pathway. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 213(Pt 14), 2410–2416. doi: 10.1242/jeb.041319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-Scully K, Armstrong GABB, Kent C, Robertson RM, & Sokolowski MBMB (2007). Natural variation in the thermotolerance of neural function and behavior due to a cGMP-dependent protein kinase. PLoS One, 2(8), e773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Belle JS, Hilliker AJ, & Sokolowski MB (1989). Genetic localization of foraging (for): A major gene for larval behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics, 123(1), 157–163. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.1.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Belle JS, & Sokolowski MB (1987). Heredity of rover/sitter: Alternative foraging strategies of Drosophila melanogaster larvae. Heredity, 59(1), 73–83. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1987.98 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deschatrettes E, Romieu P, & Zwiller J (2013). Cocaine self-administration by rats is inhibited by cyclic GMP-elevating agents: Involvement of epigenetic markers. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 16(7), 1587–1597. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712001630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlea J, Leahy A, Thimgan MS, Suzuki Y, Hughson BN, Sokolowski MB, & Shaw PJ (2012). foraging alters resilience/vulnerability to sleep disruption and starvation in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(7), 2613–2618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112623109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddison M, Belay AT, Sokolowski MB, & Heberlein U (2012). A genetic screen for olfactory habituation mutations in Drosophila: Analysis of novel foraging alleles and an underlying neural circuit. PLoS One, 7(12), e51684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL, Taber K, Vinton E, & Crocker AJ (2019). Studying alcohol use disorder using Drosophila melanogaster in the era of ‘Big Data’. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 15(1), 7. doi: 10.1186/s12993-019-0159-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel JE, Xie X-J, Sokolowski MB, & Wu C-F (2000). A cGMP-dependent protein kinase gene, foraging, modifies habituation-like response decrement of the giant fiber escape circuit in Drosophila. Learning & Memory, 7(5), 341–352. doi: 10.1101/lm.31600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil R, Hartmann J, Luo C, Wolfsgruber W, Schilling K, Feil S, … Hofmann F (2003). Impairment of LTD and cerebellar learning by Purkinje cell-specific ablation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I. The Journal of Cell Biology, 163(2), 295–302. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara M, Sengupta P, & McIntire SL (2002). Regulation of body size and behavioral state of C. elegans by sensory perception and the EGL-4 cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Neuron, 36(6), 1091–1102. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01093-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George EA, Bröger A, Thamm M, Brockmann A, & Scheiner R (2020). Inter-individual variation in honey bee dance intensity correlates with expression of the foraging gene. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 19(1), e12592. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi A, Al-Hasan YM, Krishnan HR, Wang Y, & Atkinson NS (2013). Functional mapping of the neuronal substrates for drug tolerance in Drosophila. Behavior Genetics, 43(3), 227–240. doi: 10.1007/s10519-013-9583-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi A, Krishnan HR, Lew L, Prado FJ, Ong DS, & Atkinson NS (2013). Alcohol-induced histone acetylation reveals a gene network involved in alcohol tolerance. PLoS Genetics, 9(12), e1003986. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveley BR, Brooks AN, Carlson JW, Duff MO, Landolin JM, Yang L, … Celniker SE (2011). The developmental transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature, 471(7339), 473–479. doi: 10.1038/nature09715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara-Guzman R, Emson PC, & Kendrick KM (1994). Modulation of in vivo striatal transmitter release by nitric oxide and cyclic GMP. Journal of Neurochemistry, 62(2), 807–810. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62020807.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawn SE, Sheerin CM, Webb BT, Peterson RE, Do EK, Dick D, … Amstadter AB (2018). Replication of the interaction of PRKG1 and trauma exposure on alcohol misuse in an independent African American sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(6), 927–932. doi: 10.1002/jts.22339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberlein U (2000). Genetics of alcohol-induced behaviors in Drosophila. Alcohol Research & Health, 24(3), 185–188. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11199289 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heylen K, Gobin B, Billen J, Hu T, Arckens L, & Huybrechts R (2008). Amfor expression in the honeybee brain: A trigger mechanism for nurse-forager transition. Journal of Insect Physiology, 54(10–11), 1400–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Flockhart I, Vinayagam A, Bergwitz C, Berger B, Perrimon N, & Mohr SE (2011). An integrative approach to ortholog prediction for disease-focused and other functional studies. BMC Bioinformatics, 12(1), 357. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughson BN, Anreiter I, Jackson Chornenki NL, Murphy KR, Ja WW, Huber R, & Sokolowski MB (2018). The adult foraging assay (AFA) detects strain and food-deprivation effects in feeding-related traits of Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of Insect Physiology, 106 (Pt 1), 20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2017.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram KK, Oefner P, & Gordon DM (2005). Task-specific expression of the foraging gene in harvester ants. Molecular Ecology, 14(3), 813–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02450.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabra M, Robie AA, Rivera-Alba M, Branson S, & Branson K (2013). JAABA: Interactive machine learning for automatic annotation of animal behavior. Nature Methods, 10(1), 64–67. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaun KR, Azanchi R, Maung Z, Hirsh J, & Heberlein U (2011). A Drosophila model for alcohol reward. Nature Neuroscience, 14(5), 612–619. doi: 10.1038/nn.2805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaun KR, Chakaborty-Chatterjee M, & Sokolowski MB (2008). Natural variation in plasticity of glucose homeostasis and food intake. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 211(Pt 19), 3160–3166. doi: 10.1242/jeb.010124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaun KR, Hendel T, Gerber B, & Sokolowski MB (2007). Natural variation in Drosophila larval reward learning and memory due to a cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Learning & Memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.), 14(5), 342–349. doi: 10.1101/lm.505807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent CF, Daskalchuk T, Cook L, Sokolowski MB, & Greenspan RJ (2009). The Drosophila foraging gene mediates Adult Plasticity and gene-environment interactions in behaviour, metabolites, and gene expression in response to food deprivation. PLoS Genetics, 5(8), e1000609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, McNamara PJ, Hasin DS, & Cao D (2014). alcohol challenge responses predict future alcohol use disorder symptoms: A 6-year prospective study. Biological Psychiatry, 75(10), 798–806. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleppisch T, & Feil R (2009). cGMP signalling in the mammalian brain: Role in synaptic plasticity and behaviour. In: Schmidt HHHW et al. (eds.), Handbook of experimental pharmacology (Vol. 191, pp. 549–579), Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn NR, Reaume CJ, Moreno C, Burns JG, Sokolowski MB, & Mery F (2013). Social environment influences performance in a cognitive task in natural variants of the foraging gene. PLoS One, 8(12), e81272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong EC, Allouche L, Chapot PA, Vranizan K, Moore MS, Heberlein U, & Wolf FW (2010). Ethanol-regulated genes that contribute to ethanol sensitivity and rapid tolerance in Drosophila. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(2), 302–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01093.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz S, Poeck B, Sokolowski MB, & Strauss R (2012). The visual orientation memory of Drosophila requires Foraging (PKG) upstream of Ignorant (RSK2) in ring neurons of the central complex. Learning & Memory, 19(8), 337–340. doi: 10.1101/lm.026369.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathen DR, Merrill CB, & Rothenfluh A (2020). Flying together: Drosophila as a tool to understand the genetics of human alcoholism. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(18), 6649. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KM, Mathies LD, & Grotewiel M (2019). Alcohol sedation in adult Drosophila is regulated by cysteine proteinase-1 in cortex glia. Communications Biology, 2(1), 252. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0492-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey DJ (2004). The evolutionary ecology of ethanol production and alcoholism. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 44(4), 284–289. doi: 10.1093/icb/44.4.284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas C, & Sokolowski MB (2009). Molecular basis for changes in behavioral state in ant social behaviors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(15), 6351–6356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809463106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell MW, & Fitzpatrick MJ (2017). ‘Foraging’ for a place to lay eggs: A genetic link between foraging behaviour and oviposition preferences. PLOS One, 12(6), e0179362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mery F, Belay AT, So AK-C, Sokolowski MB, Kawecki TJ, K-C So A, … Kawecki TJ (2007). Natural polymorphism affecting learning and memory in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(32), 13051–13055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702923104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova TV, Anholt RR, & Mackay TF (2007). Phenotypic and transcriptional response to selection for alcohol sensitivity in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Biology, 8(10), R231. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova TV, Ayroles JF, Jordan KW, Duncan LH, Carbone MA, Lyman RF, … Anholt RRH (2009). Alcohol sensitivity in Drosophila: Translational potential of systems genetics. Genetics, 183(2), 733–745. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.107490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova TV, Huang W, Pray VA, Whitham T, Anholt RRH, & Mackay TFC (2015). Polymorphisms in early neurodevelopmental genes affect natural variation in alcohol sensitivity in adult drosophila. BMC Genomics, 16(1), 865. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2064-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nègre N, Brown CD, Ma L, Bristow CA, Miller SW, Wagner U, … White KP (2011). A cis-regulatory map of the Drosophila genome. Nature, 471(7339), 527–531. doi: 10.1038/nature09990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent FS, Penick EC, & Kauer JA (2007). Opioids block long-term potentiation of inhibitory synapses. Nature, 446(7139), 1086–1090. doi: 10.1038/nature05726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez KM, Azanchi R, & Kaun KR (2018). Cue-induced ethanol seeking in Drosophila melanogaster is dose-dependent. Frontiers in Physiology, 9(APR), 438. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojelade SA, Jia T, Rodan AR, Chenyang T, Kadrmas JL, Cattrell A, … Rothenfluh A (2015). Rsu1 regulates ethanol consumption in Drosophila and humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(30), E4085–E4093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417222112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne KA, Robichon A, Burgess E, Butland S, Shaw RA, Coulthard A, … Sokolowski MB (1997). Natural behavior polymorphism due to a cGMP-dependent protein kinase of Drosophila. Science, 277(5327), 834–836. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A, Ghezzi A, Wijesekera TP, & Atkinson NS (2017). Genetics and genomics of alcohol responses in Drosophila. Neuropharmacology, 122, 22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst SJ, Adhikari P, Navarrete JS, Legendre A, Manansala M, & Wolf FW (2018). Perineurial barrier glia physically respond to alcohol in an Akap200-dependent manner to promote tolerance. Cell Reports, 22(7), 1647–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.01.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul C, Schoberl F, Weinmeister P, Micale V, Wotjak CT, Hofmann F, & Kleppisch T (2008). Signaling through cGMP-Dependent protein kinase i in the amygdala is critical for auditory-cued fear memory and long-term potentiation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 28(52), 14202–14212. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2216-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira HS, & Sokolowski MB (1993). Mutations in the larval foraging gene affect adult locomotory behavior after feeding in Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 90(11), 5044–5046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruccelli E, Feyder M, Ledru N, Jaques Y, Anderson E, & Kaun KR (2018). Alcohol activates scabrous-notch to influence associated memories. Neuron, 100(5), 1209–1223.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruccelli E, & Kaun KR (2019). Insights from intoxicated Drosophila. Alcohol, 74, 21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe A-S, Jeanson R, Pasquaretta C, Rebaudo F, Sueur C, & Mery F (2016). Genetic variation in aggregation behaviour and interacting phenotypes in Drosophila. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 283(1827), 20152967. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.2967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Alley KJ, Slutske WS, Wood PK, Sher KJ, Shiffman S, & Heath AC (2012). Low sensitivity to alcohol: Relations with hangover occurrence and susceptibility in an ecological momentary assessment investigation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73(6), 925–932. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinzón JH, Reed AR, Shalaby NA, Buszczak M, Rodan AR, & Rothenfluh A (2017). Alcohol-induced behaviors require a subset of Drosophila JmjC-domain histone demethylases in the nervous system. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 41(12), 2015–2024. doi: 10.1111/acer.13508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polimanti R, Kaufman J, Zhao H, Kranzler HR, Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, … Stein MB (2018). A genome-wide gene-by-trauma interaction study of alcohol misuse in two independent cohorts identifies PRKG1 as a risk locus. Molecular Psychiatry, 23(1), 154–160. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizen DDM, Zimmerman JEJ, Maycock MMH, Nature UT, 2008, U., Ta UD, … Pack AI (2008). Lethargus is a Caenorhabditis elegans sleep-like state. Nature, 451(7178), 569–572. doi: 10.1038/nature06535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaume CJ, Sokolowski MB, & Mery F (2011). A natural genetic polymorphism affects retroactive interference in Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 278(1702), 91–98. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renger JJ, Yao W-D, Sokolowski MB, & Wu C-F (1999). Neuronal polymorphism among natural alleles of a cGMP-dependent kinase gene, foraging, in Drosophila. The Journal of Neuroscience, 19(19), RC28–RC28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-j0002.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson RM, & Sillar KT (2009). The nitric oxide/cGMP pathway tunes the thermosensitivity of swimming motor patterns in Xenopus laevis tadpoles. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(44), 13945–13951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3841-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodan AR, & Rothenfluh A (2010). The genetics of behavioral alcohol responses in drosophila. International Review of Neurobiology, 91, 25–51. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(10)91002-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romieu P, Gobaille S, Aunis D, & Zwiller J (2008). Injection of the neuropeptide CNP into dopaminergic rat brain areas decreases alcohol intake. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1139(1), 27–33. doi: 10.1196/annals.1432.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson WK, Bianchi R, & Mogg R (1988). Evidence for a dopaminergic mechanism for the prolactin inhibitory effect of atrial natriuretic factor. Neuroendocrinology, 47(3), 268–271. doi: 10.1159/000124922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaplen KM, Mei NJ, Bounds HA, Song SL, Azanchi R, & Kaun KR (2019). Automated real-time quantification of group locomotor activity in Drosophila melanogaster. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 4427. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40952-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaplen KM, Talay M, Nunez KM, Salamon S, Waterman AG, Gang S, … Kaun KR (2020). Circuits that encode and guide alcohol-associated preference. eLife, 9, e48730. doi: 10.7554/eLife.48730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiner R, Sokolowski MB, & Erber J (2004). Activity of cGMP-Dependent Protein Kinase (PKG) affects sucrose responsiveness and habituation in Drosophila melanogaster. Learning & Memory, 11(3), 303–311. doi: 10.1101/lm.71604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz H, Ramond J, Singh CM, & Heberlein U (2000). Functional ethanol tolerance in drosophila. Neuron, 28(1), 261–271. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00101-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA (1994a). Alcohol sensitivity and dependence. In Toward a molecular basis of alcohol use and abuse (pp. 341–348). Basel: Birkhäuser. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7330-7_34 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA (1994b). Low level of response to alcohol as a predictor of future alcoholism. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(2), 184–189. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.2.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA (2018). A critical review of methods and results in the search for genetic contributors to Alcoholism Sensitivity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 42(5), 822–835. doi: 10.1111/acer.13628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby NA, Sayed R, Zhang Q, Scoggin S, Eliazer S, Rothenfluh A, & Buszczak M (2017). Systematic discovery of genetic modulation by Jumonji histone demethylases in Drosophila. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 5240. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05004-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shohat-Ophir G, Kaun KR, Azanchi R, Mohammed H, & Heberlein U (2012). Sexual deprivation increases ethanol intake in Drosophila. Science, 335(6074), 1351–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1215932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh CM, & Heberlein U (2000). Genetic control of acute ethanol-induced behaviors in Drosophila. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(8), 1127–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02075.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolowski HM, Vasquez OE, Unternaehrer E, Sokolowski DJ, Biergans SD, Atkinson L, … Sokolowski MB (2017). The Drosophila foraging gene human orthologue PRKG1 predicts individual differences in the effects of early adversity on maternal sensitivity. Cognitive Development, 42, 62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolowski MB (1980). Foraging strategies of Drosophila melanogaster: A chromosomal analysis. Behavior Genetics, 10(3), 291–302. doi: 10.1007/BF01067774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struk AA, Mugon J, Huston A, Scholer AA, Stadler G, Higgins ET, … Danckert J (2019). Self-regulation and the foraging gene (PRKG1) in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(10), 4434–4439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809924116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiriet N, Jouvert P, Gobaille S, Solov’eva O, Gough B, Aunis D, … Zwiller J (2001). C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) regulates cocaine-induced dopamine increase and immediate early gene expression in rat brain. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 14(10), 1702–1708. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01791.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzbay İT., Çelik T, Aydın A, Kayir H, Tokgöz S, & Bilgi C (2004). Effects of chronic ethanol administration and ethanol withdrawal on cyclic guanosine 3’,5’-monophosphate (cGMP) levels in the rat brain. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 74(1), 55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, & Sokolowski MB (2017). Aggressive behaviours, food deprivation and the foraging gene. Royal Society Open Science, 4(4), 170042. doi: 10.1098/rsos.170042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Pan Y, Li W, Jiang H, Chatzimanolis L, Chang J, … Liu L (2008). Visual pattern memory requires foraging function in the central complex of Drosophila. Learning & Memory, 15(3), 133–142. doi: 10.1101/lm.873008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen R-T, Zhang F-F, & Zhang H-T (2018). Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: Potential therapeutic targets for alcohol use disorder. Psychopharmacology, 235(6), 1793–1805. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-4895-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenseleers T, Billen J, Arckens L, Tobback J, Huybrechts R, Heylen K, & Gobin B (2008). Cloning and expression of PKG, a candidate foraging regulating gene in Vespula vulgaris. Animal Biology, 58(4), 341–351. doi: 10.1163/157075608X383665 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werner C, Raivich G, Cowen M, Strekalova T, Sillaber I, Buters JT, … Hofmann F (2004). Importance of NO/cGMP signalling via cGMP-dependent protein kinase II for controlling emotionality and neurobehavioural effects of alcohol. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 20(12), 3498–3506. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03793.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Pan J, Sun J, Ding L, Ruan L, Reed M, … O’Donnell JM (2015). Inhibition of phosphodiesterase 2 reverses impaired cognition and neuronal remodeling caused by chronic stress. Neurobiology of Aging, 36(2), 955–970. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]