Abstract

Several environmental and genetic factors may influence the risk of congenital heart defects (CHDs), which can have a substantial impact on pediatric morbidity and mortality. We investigated the association of polymorphisms in the genes of the folate and methionine pathways with CHDs using different strategies: a case–control, mother–child pair design, and a family-based association study. The polymorphism rs2236225 in the MTHFD1 was confirmed as an important modulator of CHD risk in both, whereas polymorphisms in MTRR, FPGS, and SLC19A1 were identified as risk factors in only one of the models. A strong synergistic effect on the development of CHDs was detected for MTHFD1 polymorphism and a lack of maternal folate supplementation during early pregnancy. A common polymorphism in the MTHFD1 is a genetic risk factor for the development of CHD, especially in the absence of folate supplementation in early pregnancy.

Keywords: congenital heart defects, methylene-tetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1, folate supplementation, genetic risk factors

1. Introduction

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) occur in approximately nine per 1000 births, and they are thus among the more common congenital malformations [1]. Although CHDs can vary from relatively mild to very severe, they can have a significant impact on pediatric morbidity and mortality [2]. CHDs are a very heterogeneous group of diseases, and several systems for their classification have been proposed, including according to symptoms (e.g., cyanotic and a-cyanotic) [3,4], etiology (e.g., the National Birth Defect Prevention Study [NBDPS]) [2], and the ICD-10 World Health Organization classification [5].

Several environmental CHD risk factors have been identified [6], such as maternal folic acid deficiency, maternal diabetes, fever in first trimester, maternal chronic disease, advanced maternal age, and maternal drug exposure. However, the genetics of CHDs remain obscure, including for the numerous genes with weak contributions [7], and the sometimes conflicting effects in different studies.

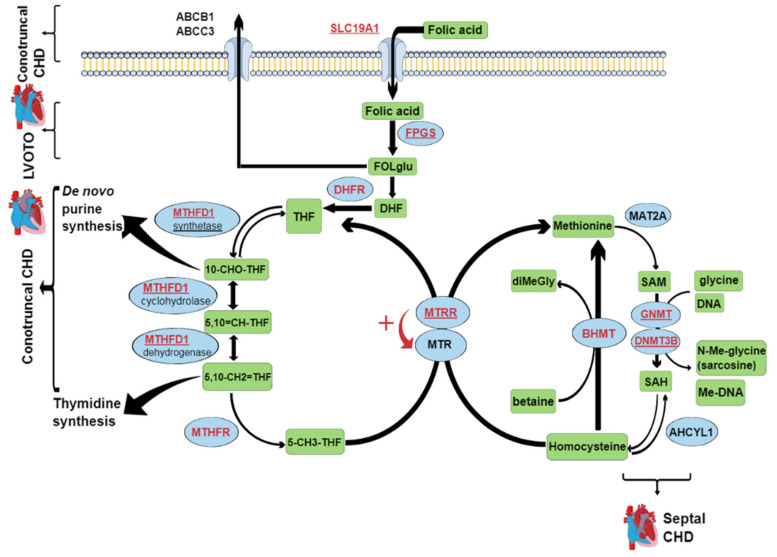

The role of folates and their metabolism in the development of neural tube defects (NTDs) is well established, although a firm connection between maternal folate supplementation during pregnancy and decreased risk of certain forms of CHDs was only recently confirmed [8]. The same association has been defined between food fortification with folic acid and reduction in the birth prevalence of specific CHDs [9]. An intact folate metabolism is crucial during embryo development, as it provides cells with enough one-carbon-activated folate cofactors for sufficient de novo purine and thymidine synthesis and for the production of the essential amino acid methionine and the elimination of the teratogenic homocysteine (Figure 1). In addition, the methionine cycle provides the main methyl donor S-adenosylmethionine, which is crucial to most remethylation reactions (Figure 1), including the DNA methylation that is an important regulator of gene expression during embryogenesis.

Figure 1.

The folate metabolic pathways. Blue ellipses, enzymes; green rectangles, metabolites; written in red, names of genes selected for genotype analysis; underlined, genes that showed a significant association with certain types of CHD (contruncal, septal, and LVOTO). ABCB1, P-glycoprotein; ABCC3, multidrug resistant protein 3; SLC19A1; solute-carrier family 19; FPGS, folypolyglutamyl synthase; FOLglu, polyglutamylated folic acid; DHF, dihydrofolate; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; THF, tetrahydrofolate; MTHFD1, trifunctional methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase/synthase; 10-CHO-THF, 10-formyl tetrahydrofolate; 5,10 = CH-THF, methenyl tetrahydrofolate; 5,10-CH2 = THF, methylene tetrahydrofolate; 5-CH3-THF, 5-methyl tetrahydrofolate; MTR, 5-methyl tetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase; MTRR, 5-methyl tetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase reductase; MAT2A, methionine adenosyltransferase II alpha; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; SAH, S-adenosylhomocysteine; GNMT, glycine N-methyltransferase; DNMT3B, DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 3 beta; ACHYL1, S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase-like 1; BHMT, betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase; diMeGly, dimethylglycine; Me, methyl; LVOTO, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; CHD, congenital heart defect.

Polymorphisms in several genes involved in the folate and methionine cycles have been implicated as genetic risk factors for the development of CHDs, including rs1801131 and rs1801133 in the methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene [10], rs2236225 in the methylene-tetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 (MTHFD1) gene [11], rs1801394 in the methyl-tetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase reductase (MTRR) gene [12], rs1051266 in the solute carrier family 19 member 1 (SLC19A1) gene [13], duplications [14] and deletions [15] in the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) gene, and rs3733890 in the betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase (BHMT) gene [16]. However, the results from these studies have often been conflicting, as sometimes the same polymorphism has been positively or negatively correlated with, or even not at all associated with, CHDs. Furthermore, there are genes in the folate and methionine cycles and the connected methylation pathways that have never been studied in connection with CHDs, such as the genes for folypolyglutamyl synthase (FPGS), glycine N-methyltransferase (GNMT), and DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 3 beta (DNMT3B). Thus, we undertook strategies to investigate the associations of these polymorphisms and genes with CHDs: a case–control, mother–child pair design, and a family-based association study. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the influence on the development of CHDs of polymorphisms in FPGS, GNMT, and DNMT3B.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort

The study cohort consisted of 199 pairs of children (cases) with CHD and their mothers and of 99 pairs of healthy children (controls) and their mothers. Since controls and cases were not paired, all multinomial logistic regression models were adjusted for demographic variables. In some CHD cases, the samples from the fathers were available, such that a total 44 family triads where the child was affected with CHD were collected. The DNA was collected from the children and their mothers and fathers using buccal swabbing. In addition, all of the mothers filled out a questionnaire about the potential demographic and environmental risk factors during their pregnancy with the index child. CHD cases were recruited sequentially. The children with CHD and their mothers were recruited at the Department of Cardiology, University Children`s Hospital, University Medical Centre Ljubljana (Slovenia), during routine check-ups. The buccal swabs from the fathers were obtained by post after they had consented to being involved in the study. The control samples were obtained from healthy newborns and their mothers at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, during their routine postnatal 3-day stays.

Enrolment time for the controls was two months and for CHD cases was 1.5 years. Since the study endpoint was the presence or absence of CHD, the follow-up time for CHD cases was not applicable. Controls were followed-up for a year after the inclusion in the study to assure the absence of any milder forms of CHD that might be detected later after birth.

Informed consent was obtained from all of the participants and/or their legal guardians. The study was approved by the National Medical Ethics Committee of the Republic of Slovenia (NMEC) (No. 57/02/13) and was performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

2.2. Questionnaire

The questionnaire that was completed by all of the mothers for both the case and control children consisted of two parts. The first part focused on exposure to known demographic and environmental risk factors, where the following data were collected: maternal age at conception, height, weight, smoking status, education, number of pregnancies, live births and miscarriages, family anamnesis of CHD and other congenital malformations, child gender, gestational diabetes, other chronic diseases of the mothers, drug and sauna use during pregnancy, fever during pregnancy, and folate and vitamin supplementation before conception and during pregnancy. The second part of the questionnaire was based on the Willett/Harvard food frequency questionnaire [17], and this was used to evaluate the maternal diet in the periconception period. The mothers were asked to recall their diet over the previous 4 weeks. They then reported on the similarity of their food intake during this previous 4 weeks to that in the periconception period. This used a scale ranging from 0 to 5, with 0 designating no recall or total discordance, and 5 denoting a high level of concordance. Based on this data, the monthly intake of folic acid and methionine in the periconception period was calculated for the mothers that reported levels 4 or 5 for diet concordance.

2.3. DNA Extraction and Genotyping

The DNA was extracted from buccal swabs using QIAamp DNA mini kits (Qiagen) or MasterPure complete DNA and RNA purification kits (Epicentre (Illumina) Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer instructions.

The interactions between the genes of interest were evaluated by text and database mining using STRING 10.0 [18]. For each of the selected genes, at least one polymorphism was chosen for the genotype analysis, which showed a minor allele frequency ≥25% and the highest number of PubMed connections to CHD and/or etiologically related conditions (e.g., NTD and orofacial cleft). Ten common polymorphisms in nine genes involved in the folate and methionine cycles were analyzed using the TaqMan (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) or LightSNiP (TIB MOLBIOL, Berlin, Germany) probes, according to the manufacturer instructions. The following polymorphisms were genotyped using TaqMan probes: rs1544105 (FPGS) (assay number C_8342611_10), rs1677693 (DHFR) (assay number C_3103231_10), rs1801133 and rs1801131 (MTHFR) (assay numbers C_1202883_20 and C_850486_20), rs1801394 (MTRR) (assay number C_3068176_10), rs2236225 (MTHFD1) (assay number C_1376137_10), rs3733890 (BHMT) (assay number C_11646606_20), rs10948059 (GNMT) (assay number C_11425842_10), and rs2424913 (DNMT3B) (assay number C_25620192_20). Genotyping of rs1051266 (SLC19A1) was carried out by LightSNiP.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Analysis of Case and Control Mother–Child Pairs

The sample size calculation was based on the reported frequencies of the polymorphisms investigated in Caucasian populations and the detection of a 15% difference between wild-type and variant genotypes at 80% power and α = 0.05.

For continuous variables, the normality of the distribution across four categories (control, septal CHD, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction [LVOTO] CHD, and conotruncal CHD) was checked using Shapiro–Wilk tests. For simple statistical analysis, one-way ANOVA was used for Gaussian continuous variables, Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for non-Gaussian continuous and rank/score variables, and Fisher`s exact tests were used for categorical variables.

For all genotypes (except MTHFR), the dominant, recessive, and additive genetic models were calculated, although only the one with the highest statistical significance was used here. For MTHFR, two relevant polymorphisms were investigated (c.677 C > T; c.1298 A > C), which were analyzed together as genotype combinations. Using this approach, all of the subjects were classified into six genotype combinations. For the statistical analysis, the subjects were segregated into two groups according to the total number of mutated alleles at both loci: the wild-type genotype at both loci (i.e., 677 CC/1298 AA) and all of the other genotype combinations with at least one mutated allele (i.e., 677CT/1298AA, 677CC/1298AC, 677CC/1298CC, 677CT/1298AC, and 677TT/1298AA).

Odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals, and adjusted p values were calculated in multinomial logistic regression models for the mothers and children separately. Separate logistic regression models for the mothers and children were constructed to avoid violation of the assumption of no interactions. Only the variables with unadjusted p values < 0.250 were included in the multinomial logistic regression models. These variables were also adjusted for co-variables.

All of the tests were two-tailed, with the level of significance set at α = 0.05 for multinomial logistic regression. For the one-way ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis, and Fisher’s exact tests, Bonferroni corrections for multiple testing were used, and p < 0.001 was considered significant.

All of the statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.

2.4.2. Likelihood Ratio Test Analysis

To test for association between CHD and the genetic markers studied, likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) were used, as developed by Fan et al. [19], which allows the use of triads, parent-child dyads, and singleton monads in a unified analysis. The associations were tested for each of the single nucleotide polymorphisms with CHD (all) or with subgroups of CHD (e.g., atrial septal defect, conotruncal, LVOTO, patent ductus arteriosus, and septal and ventricular septal defects) using three different models: dominant, recessive, and additive. All of the tests were performed using the statistical package R. The R codes were obtained from the Internet [20] and appropriately adjusted.

3. Results

3.1. Study Cohort Description

Of the 199 CHD patients recruited to the study, 113 (56.8%) were male, and 86 (43.2%) were female children; similarly, of the 199 children in the control group, 111 (55.8%) were male, and 88 (44.2%) were female. All of the mothers of both the cases and controls were included in the study, as well as 44 fathers of the CHD cases.

The full classification of the study cohort by CHD symptoms and etiology, and according to ICD-10 (WHO 2016), is given in Table 1. More than one of the malformations given in Table 1 was present in 48 (24%) of the cases.

Table 1.

Classification of the study cohort by CHD symptoms and etiology, and according to ICD-10 (WHO 2016). ACY, acyanotic; CY, cyanotic; NBDPS, National Birth Defect Prevention Study (CDC coordinated USA nationwide study); LVOTO, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; RVOTO, right ventricular outflow tract obstruction; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; Q20, congenital malformations of the cardiac chambers and connections; Q21, congenital malformations of the cardiac septa; Q22, congenital malformations of the pulmonary and tricuspid valves; Q23, congenital malformations of the aortic and mitral valves; Q24, other congenital malformations of the heart; Q25, congenital malformations of the great arteries.

| CHD Type | Cases [n (%)] | Classification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By Symptoms | By Aetiology (NBDPS Level 3) | ICD-10 | ||

| Ventricular septal defect | 80 (40) | ACY | Septal | Q21.0 |

| Atrial septal defect | 60 (30) | ACY | Septal | Q21.1 |

| Aortic stenosis | 21 (11) | ACY | LVOTO | Q25.3 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 16 (8) | ACY | PDA | Q25.0 |

| Coarctation of aorta | 15 (8) | ACY | LVOTO | Q25.1 |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 13 (7) | CY | Conotruncal | Q21.3 |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 10 (5) | LVOTO | Q23.1 | |

| Pulmonary valve stenosis | 8 (4) | ACY | RVOTO | Q22.1 |

| Transposition of great vessels | 7 (4) | CY | Conotruncal | Q20.3 |

| Atrioventricular septal defect | 5 (3) | AVSD | Q21.2 | |

| Double outlet right ventricle | 5 (3) | CY | Conotruncal | Q20.1 |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome | 3 (2) | LVOTO | Q23.4 | |

| Pulmonary valve atresia | 3 (2) | CY | RVOTO | Q22.0 |

| Persistent truncus arteriosus | 3 (2) | CY | Conotruncal | Q20.0 |

| Mitral valve prolapse | 2 (1) | LVOTO | Q23.8 | |

| Aortic regurgitation | 1 (0.5) | LVOTO | Q23.1 | |

| Mitral (valve) stenosis | 1 (0.5) | ACY | LVOTO | Q23.2 |

| Tricuspid atresia | 1 (0.5) | CY | RVOTO | Q22.4 |

| Atrial septal aneurism | 1 (0.5) | |||

| Major aotropulmonary collateral artery | 1 (0.5) | |||

| Single ventricle | 1 (0.5) | Complex | Q20.4 | |

| Overriding aorta | 1 (0.5) | Conotruncal | Q25.4 | |

| Right atrial isomerism | 1 (0.5) | Heterotaxy | Q20.6 | |

| Pulmonary artery stenosis | 1 (0.5) | RVOTO | Q25.6 | |

| Mitral valve insufficiency | 1 (0.5) | LVOTO | Q23.3 | |

| Mitral valve cleft | 1 (0.5) | LVOTO | Q23.8 | |

3.2. Case–Control Study

The case–control study included the 199 CHD cases and their mothers as compared to the 199 control children and their mothers. The comparisons of the children and the mothers were carried out separately for genetic risk factors. First, all of the CHD cases were compared to the controls (i.e., irrespective of CHD type). Next, three of the most common NBDPS CHD classes were compared to the controls (i.e., septal CHD, conotruncal CHD, and LVOTO CHD). Finally, the most common types of the NBDPS CHD classes were compared to the controls (i.e., ventricular septal defect [VSD], atrial septal defect [ASD], aortic stenosis [AS], and tetralogy of Fallot [TOF]).

3.2.1. CHD versus Controls

Among the environmental risk factors, only positive family anamnesis of CHD and not taking folate supplements in the first trimester of pregnancy were associated with the increased risk of CHD after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (α = 0.001) and after adjustment for confounding variables in the logistic regression model. None of the genetic risk factors reached the threshold of significance of α = 0.001. The complete data of these relatively simple statistical and logistic regression analyses are presented in Table S1, Supplementary Materials.

3.2.2. Septal, Conotruncal, and LVOTO CHD versus Controls

Using simple statistical analysis and after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (α = 0.001), the following environmental risk factors reached the threshold of significance: child gender, number of pregnancies and live births, family anamnesis of CHD, and methionine and folic acid intake per month. The complete data for this relatively simple statistical analysis are presented in Table S2.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis was then performed for environmental risk factors. Only the variables with p < 0.250 were included in the model. In short, the risk for septal CHD was increased by the following: being female, maternal smoking, higher parity, positive family anamnesis of CHD, maternal chronic disease, and no intake of folates in early pregnancy. The risk factors for LVOTO were as follows: being male, higher parity, positive family anamnesis of CHD, and no intake of folates in early pregnancy. For conotruncal CHD, the only environmental risk factors identified were as follows: maternal smoking, higher parity, and positive family anamnesis of CHD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multinomial logistic regression models of selected environmental risk factors in the control and congenital heart defect (CHD) sub-groups (septal, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction [LVOTO], and conotruncal). OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

| Variable | Control vs. Septal | Control vs. LVOTO | Control vs. Conotruncal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) ‡ | p adj‡ | OR (95% CI) ‡ | p adj‡ | OR (95% CI) ‡ | p adj‡ | |

| Child gender | ||||||

| Male † vs. female | 2.1 (1.1–4.1) | 0.035 | 0.2 (0.1–0.7) | 0.011 | 0.4 (0.1–1.2) | 0.094 |

| Maternal smoking status | ||||||

| Non-smoker † vs. smoker | 7.3 (2.1–24.9) | 0.002 | 2.9 (0.7–11.8) | 0.139 | 7.7 (1.8–31.9) | 0.005 |

| Non-smoker † vs. ex-smoker | 2.7 (1.1–6.5) | 0.029 | 0.7 (0.2–2.1) | 0.523 | 1.4 (0.4–5.0) | 0.561 |

| Maternal education | ||||||

| MSc, PhD † vs. elementary school | 6.1 (0.5–72.3) | 0.154 | 4.1 (0.1–127) | 0.415 | 1.4 (0.04–45.1) | 0.865 |

| MSc, PhD † vs. vocational school | 2.4 (0.4–13.1) | 0.311 | 3.7 (0.3–47.9) | 0.312 | 3.2 (0.3–30.7) | 0.309 |

| MSc, PhD † vs. high school | 2.8 (0.3–23.4) | 0.345 | 2.8 (0.1–75.6) | 0.549 | NA | |

| MSc, PhD † vs. college | 4.6 (0.8–26.7) | 0.090 | 3.9 (0.2–65.9) | 0.339 | 0.7 (0.04–13.9) | 0.812 |

| MSc, PhD † vs. university | 1.6 (0.3–8.6) | 0.560 | 2.8 (0.2–35.8) | 0.418 | 0.7 (0.06–7.2) | 0.737 |

| No. of live births | 1.8 (1.2–2.6) | 0.004 | 2.1 (1.4–3.3) | 0.001 | 1.9 (1.1–3.1) | 0.017 |

| Family anamnesis of CHD | ||||||

| Negative † vs. Positive | 9.3 (2.3–37.0) | 0.002 | 18.9 (3.8–90.9) | 0.0003 | 11.1 (2.1–58.8) | 0.005 |

| Maternal chronic disease | ||||||

| No † vs. Yes | 2.8 (1.0–7.4) | 0.043 | 3.6 (0.9–13.9) | 0.062 | 0.9 (0.2–5.5) | 0.921 |

| Other drugs in pregnancy | ||||||

| No † vs. Yes | 2.0 (1.0–4.1) | 0.055 | 3.6 (0.9–13.9) | 0.062 | 0.9 (0.2–5.5) | 0.921 |

| Folate supplement initiation | ||||||

| No folate suppl. † vs. before 3 weeks post-conception | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | 0.010 | 0.2 (0.05–0.7) | 0.011 | 0.6 (0.2–2.1) | 0.394 |

| No folate suppl. † vs. after 3 weeks post-conception | 0.4 (0.1–1.1) | 0.067 | 0.5 (0.1–2.0) | 0.350 | 0.4 (0.1–2.0) | 0.286 |

| Folic acid intake per month (mg) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.069 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.417 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.071 |

† Reference category. ‡ Odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI), and adjusted p values were calculated in multinomial logistic regression models for mothers and children separately. Only variables with unadjusted p values < 0.250 were included in the multinomial logistic regression models and adjusted for co-variables. Variables with high levels of correlation were not included in the same model. NA: not applicable (the variable was not tested in the specific model).

Multinomial logistic regression analysis was also performed for genetic risk factors that reached p < 0.250 in the simple statistical tests. Here, the maternal and child genotypes were analyzed in separate multinomial logistic regression models, which were adjusted for the environmental risk factors in Table 2. In multiple logistic regression analysis, no maternal or fetal genetic risk factors for septal and LVOTO CHDs were identified. On the other hand, the presence of genotypes MTHFD1 rs2236225 GG or MTRR rs1801394 AA in a child increased the risk of conotruncal CHD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression models of maternal and children`s selected genetic risk factors in control and CHD sub-groups (septal, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction [LVOTO], and conotruncal). LVOTO, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SLC19A1, solute-carrier family 19; FPGS, folypolyglutamyl synthase; GNMT, glycine N-methyltransferase; DNMT3B, DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 3 beta; MTHFD1, trifunctional methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase/synthase; MTRR, 5-methyl tetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase reductase.

| Variable | Control vs. Septal | Control vs. LVOTO | Control vs. Conotruncal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p adj‡ | OR (95% CI) | p adj‡ | OR (95% CI) | p adj‡ | |

| Child genotype SLC19A1 rs1051266 GG † vs. AG or AA | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | 0.178 | 0.6 (0.2–1.7) | 0.358 | 1.7 (0.5–6.0) | 0.389 |

| Maternal genotype FPGS rs1544105 CC or CT † vs. TT | 0.9 (0.4–2.0) | 0.775 | 1.9 (0.7–5.6) | 0.221 | 0.3 (0.05–1.5) | 0.139 |

| Maternal genotype GNMT rs10948059 CC or CT † vs. TT | 1.5 (0.7–3.2) | 0.316 | 0.8 (0.3–2.7) | 0.745 | 1.6 (0.5–4.9) | 0.402 |

| Maternal genotype DNMT3B rs2424913 CC † vs. CT or TT | 0.5 (0.3–1.1) | 0.090 | 1.3 (0.4–3.8) | 0.649 | 1.3 (0.4–4.0) | 0.686 |

| Child genotype MTHFD1 rs2236225 GG † vs. AG or AA | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 0.543 | 0.9 (0.3–2.6) | 0.895 | 0.2 (0.08–0.7) | 0.007 |

| Child genotype MTHFR 677 CC/1298 AA † vs. at least one mutated allele | 0.8 (0.3–2.5) | 0.761 | 0.7 (0.2–3.0) | 0.647 | 0.4 (0.1–1.5) | 0.190 |

| Maternal genotype MTRR rs1801394 AA or AG † vs. GG | 1.1 (0.5–2.2) | 0.882 | 1.3 (0.5–3.4) | 0.562 | 0.5 (0.2–1.6) | 0.231 |

| Child genotype MTRR rs1801394 AA † vs. AG or GG | 0.9 (0.3–2.4) | 0.838 | 0.7 (0.2–2.8) | 0.660 | 0.2 (0.08–0.7) | 0.013 |

| Number of mutated alleles in mother-child pairs | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.695 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.941 | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 0.095 |

† Reference category. ‡ All genetic risk factors were adjusted for environmental risk factors listed in Table 2. Odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval, and adjusted p values were calculated in multinomial logistic regression models for mothers and children separately. Only variables with unadjusted p values < 0.250 were included in the multinomial logistic regression models and adjusted for co-variables.

3.3. Family Triads Study

Next, a different study design was used to confirm the data from the case–control study. In 44 family triads (i.e., CHD-affected child and his/her parents), the over-transmission of alleles from the unaffected parent to the affected child was investigated using LRTs. These LRTs were performed for CHD irrespective of the class, and separately for septal, LVOTO, and conotruncal CHD, using different genetic models (i.e., dominant, recessive, and additive). The statistically significant findings of these LRT analyses are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Likelihood ratio test best hits in the family triads. CHDs, congenital heart defects; LVOTO, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; FPGS, folypolyglutamyl synthase; SLC19A1, solute carrier family 19 member 1; MTHFD1, trifunctional methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase/synthase.

| CHD Type | Gene | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism | Model | Number of Triads | Likelihood Ratio | p (α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHD total | MTHFD1 | rs2236225 | Recessive | 44 | 5.429 | 0.020 |

| LVOTO | FPGS | rs1544105 | Dominant | 7 | 4.861 | 0.027 |

| Conotruncal | SLC19A1 | rs1051266 | Dominant | 4 | 4.052 | 0.044 |

| MTHFD1 | rs2236225 | Recessive | 4 | 5.895 | 0.015 |

The MTHFD1 rs2236225 GG genotype was over-transmitted in the children with CHD for the analysis of both total CHD and conotruncal CHD, which confirmed the results of the case–control study. Conversely, the association of the MTRR rs1801394 AA genotype that was identified in the case–control study was not replicated. Additionally, an association was detected for FPGS rs1544105 T allele and SLC19A1 rs1051266 A allele with LVOTO and conotruncal defects, respectively. This association was not seen in the case–control study.

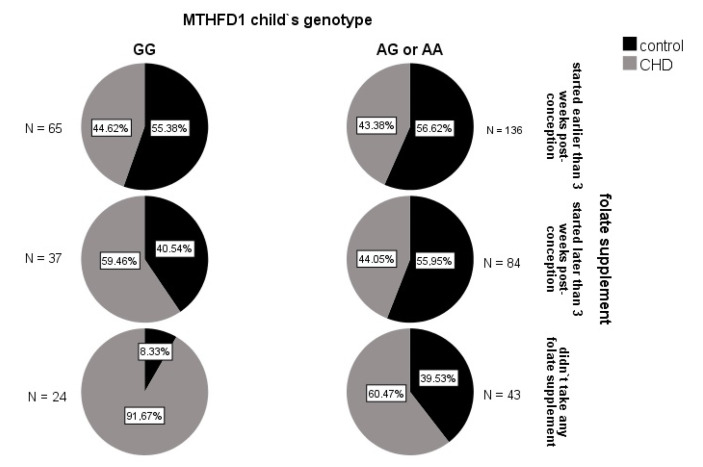

3.4. Gene × Environment Interactions

To investigate whether there were any synergistic influences of the MTHFD1 genotype and folate intake in early pregnancy on the overall CHD risk, the interaction term was included in the basic logistic regression model (see Section 3.2.1). A statistically significant interaction was detected between the MTHFD1 genotype of the child and folate intake during early pregnancy. Namely, the odds ratio of CHD occurrence in MTHFD1 GG versus AG/AA children of the group where the mothers did not use folates was 6.8-fold (95% CI 1.3–36.7; p = 0.025) compared to when the mothers started using folate supplement earlier than 3 weeks post-conception (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Incidence of CHD in the subgroups of the children, according to MTHFD1 genotype and maternal folate supplementation in early pregnancy. The highest incidence of CHD (91.7%) was seen for the MTHFD1 rs2236225 GG children whose mothers did not take any folate supplements. In contrast, the lowest incidences (~44%) were seen for the children of mothers who started folate intake early, irrespective of the MTHFD1 genotype, and in the MTHFD1 AG/AA children of mothers who started folate intake later than 3 weeks post conception.

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to identify possible genetic risk factors for CHD, with a focus on folate and methionine metabolism. In addition to the genetic polymorphisms investigated, known environmental risk factors were also taken into account in the data analysis, to avoid bias. All of the environmental CHD risk factors that were identified in the present study (i.e., child gender, maternal smoking, higher parity, positive family anamnesis of CHD, maternal chronic disease, and a lack of folate supplementation during early pregnancy) had already been detected in previous studies [8,9,21,22,23]. We investigated the association of 10 common polymorphisms in nine genes that code for the enzymes and transporters in the folate-methionine metabolic pathways with CHD and its subtypes. Although the association of six polymorphisms (i.e., MTHFD1 rs2236225, MTRR rs1801394, SLC19A1 rs1051266, GNMT rs10948059, DNMT3B rs2424913, and FPGS rs1544105) with CHD was detected, the only polymorphism that was consistently associated with CHD (particularly conotruncal CHD) after correction for multiple testing and adjustment for environmental factors was MTHFD1 rs2236225, as seen for both the case–control and family triads study designs. Thus, we can be confident that this finding represents a true biological association, and that it did not occur by chance. Table 5 gives the comparison of the data from the present study with data from previous studies of the selected polymorphisms.

Table 5.

Studies that have investigated the involvement of MTHFD1 rs2236225, MTRR rs1801394, SLC19A1 rs1051266, GNMT rs10948059, DNMT3B rs2424913, and FPGS rs1544105 in CHD development. GNMT, DNMT3B, and FPGS have not been studied in association with CHDs. MTHFD1, trifunctional methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase/synthase; MTRR, methyl-tetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase reductase; GNMT, glycine N-methyltransferase; DNMT3B, DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 3 beta; FPGS, folypolyglutamyl synthase; SLC19A1, solute carrier family 19 member 1; CHDs, congenital heart defects.

| Study | Study Design | Population | Number Cases/Controls | Gene | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism | CHD Risk Genotype or Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christensen KE et al., 2008 [11] | Mother-child pair, case-control | N. European | Children: 158/110Mothers: 199/105 | MTHFD1 | rs2236225 | AA (increased risk) |

| Zeng W et al., 2011 [35] | Case-control | Chinese Han | 599/672 | MTRR | rs1801394 | GG (increased risk) |

| Cai B et al., 2014 [12] | Meta-analysis | Mixed | 914/964441 families | MTRR | rs1801394 | G allele (increased risk) |

| Pei L et al., 2006 [13] | Case-control, family based | Chinese | Families: 67/100 | SLC19A1 | rs1051266 | G allele (increased risk) |

| Gong D et al., 2012. [24] | Case-control | Chinese Han | 244/136 | MTHFD1 | rs2236225 | No association |

| SLC19A1 | rs1051266 | A allele (increased risk) | ||||

| Christensen KE et al., 2013 [36] | Mother-child pair, case-control | N. European | Children: 156/69 | MTRR | rs1801394 | G allele (decreased risk) |

| Mothers: 181/65 | SLC19A1 | rs1051266 | No association | |||

| Wang B et al., 2013 [15] | Case-control | Chinese | 160/188 | MTHFD1 | rs2236225 | No association |

| MTRR | rs1801394 | No association | ||||

| SLC19A1 | rs1051266 | No association | ||||

| Mitchell LE et al., 2010 [16] | Family based | Mixed | 386 case-family triads | MTRR | rs1801394 | No association |

| Goldmuntz E et al., 2008 [37] | Family based | Mixed | 727 case-family triads | MTRR | rs1801394 | No association |

| Huang J et al., 2014 [25] | Case-control | Chinese | 173/2017 | MTHFD1 | rs2236225 | No association (GG more prevalent in cases than controls) |

| Shaw GM et al., 2009 [26] | Case-control | Mixed | 214/359 | MTHFD1 | rs2236225 | No association |

| Guo KN et al., 2017 [38] | Parents of cases and controls | Chinese Han | 99/114 | MTRR | rs1801394 | G allele (increased risk) |

| Yu D et al., 2014 [39] | Meta-analysis Asian | Caucasian | 3.592/3.638 | MTRR | rs1801394 | G allele (increased risk) |

| Elizabeth KE et al., 2017 [40] | Mother-child pair, case-control | Indian | Pairs: 32/32 | MTRR | rs1801394 | G allele (increased risk) |

| Hassan FM et al., 2017 [41] | Case-control | Egyptian | 100/100 | MTRR | rs1801394 | G allele (increased risk) |

| Present study | Case-control and family based | Caucasian | Case-control: 199/199Family triads: 44 | MTHFD1 | rs2236225 | GG (increased risk) |

| MTRR | rs1801394 | AA (increased risk) | ||||

| SLC19A1 | rs1051266 | A allele (increased risk) | ||||

| GNMT | rs10948059 | TT (increased risk) | ||||

| DNMT3B | rs2424913 | CC (increased risk) | ||||

| FPGS | rs1544105 | TT (increased risk) |

As evident from the data given in Table 5, the results from the studies that have investigated the association of MTHFD1 rs2236225 with CHD are ambiguous. The majority of the studies found no correlations between this polymorphism and CHD occurrence [15,24,25,26], and only one study found that AA is a risk genotype for CHD [11]. In contrast, the present study shows an increased risk of CHD in GG children, as well as an over-transmission of the G allele from unaffected parents to affected children. This is not surprising, as all of the above-mentioned studies included relatively small numbers of individuals. At the moment, the number of studies investigating associations between rs2236225 and CHD is too low to objectively evaluate the influence of rs2236225 on CHD development. In contrast, there are more studies that have investigated the influence of MTHFD1 rs2236225 on NTDs, which are congenital malformations with similar etiopathogenesis. A recent meta-analysis including 2132 children with NTD and 4082 healthy controls, and this showed no association of rs2236225 with NTD, while in mothers of the NTD cases (n = 1402) and the control children (n = 3136), the AA genotype increased the NTD risk in their offspring. Interestingly, in the same meta-analysis, the GG genotype in fathers increased the risk of NTD in their children (993 case, 2879 control fathers) [27]. Of note, the rs2236225 G allele was also seen to increase the risk of type II diabetes [28] and lung cancer [29] and was associated with higher hyperactivity and impulsivity scores in children with attention-deficit disorder [30].

Another reason for the ambiguous data across these MTHFD1 rs2236225 studies, apart from the small sample sizes, might be that the metabolic commitment of MTHFD1 is strongly modulated by the cellular levels of folate, which can greatly vary among populations and individuals. MTHFD1 is a trifunctional enzyme, with dehydrogenase, cyclohydrolase, and synthetase activities (Figure 1). MTHFD1 is involved in two key metabolic pathways: thymidine synthesis, which takes place in the cell nucleus, and homocysteine re-methylation, which takes place in the cytosol [31]. In mammalian cells, nuclear translocation of the enzymes of thymidylate synthesis (including MTHFD1) is enabled through their linking to the small ubiquitin-like modifier SUMO [31]. Thus, thymidylate synthesis and re-methylation pathways compete for a limiting pool of methylenetetrahydrofolate cofactors, as does the MTHFD1 enzyme [31,32]. In folate deficiency, MTHFD1 is preferentially located in the nucleus. In this way, thymidylate synthesis is ensured, but at the expense of homocysteine re-methylation [31,32]. However, this effect is less pronounced for MTHFD1 deficiency [32]. The total absence of MTHFD1 activity has severe consequences, as MTHFD1 knock-out mouse embryos (−/−) die at the early stage of gestation, while MTHFD1 +/− females have an increased risk of malformed offspring [33]. However, such severe defects of MTHFD1 are extremely rare in general human populations, while polymorphisms that can cause moderate decreases in MTHFD1 activity are relatively common. One of the most investigated polymorphisms of MTHFD1 is rs2236225, which leads to enzyme thermolability and consequently decreased enzyme activity. Thermolability can be prevented by addition of magnesium adenosine triphosphate or folate [11]. This can explain the interaction between the MTHFD1 rs2236225 genotype and folate supplementation in early pregnancy that was detected in the present study (Figure 2). As in the present study, G alleles corresponding to higher MTHFD1 activity increased CHD risk, and this might also be explained by an interaction mechanism. According to the data obtained for mouse models by two independent research groups [32,34], the test mice with moderately decreased MTHFD1 activity had higher methylation potential in their cells, which indicated a higher flux through the homocysteine re-methylation pathway compared to the wild-type mice. This indicates that, in individuals with higher MTHFD1 activity (i.e., the GG genotype), the thymidylate rescue mechanism is more effective, which results in higher thymidylate synthesis rates, but lower homocysteine re-methylation rates, and consequently higher intracellular levels of the teratogenic homocysteine. In the mouse models previously mentioned [32,34], the test mice with defective MTHFD1 also had lower uracil mis-incorporation rates into DNA compared to the wild-type mice, which was probably due to the higher dUMP-to-dTMP methylation rate. In analogy, the rs2236225 GG individuals might have higher uracil mis-incorporation rates, which will lead to higher mutation rates and DNA damage, thus increasing the risk of congenital malformations (e.g., CHD).

The discrepancies in identified correlations between ours and other similar studies could be related to the differences among the studied populations. It is known that folate intake can influence the pathogenicity of mutations in genes coding for enzymes and transporters in the folate pathway. Since different populations have different diets and consequently differing folate intake and levels, the pathogenicity of those mutations can be expressed differently in different populations. The second populational influence could be the fact that MAF of rs2236225 varies among populations. For example, rs2236225 MAF is much higher in European and South Asian populations compared to those of East Asia and Africa.

5. Conclusions

We have shown that the common rs2236225 polymorphism in the MTHFD1 gene is an important modulator of CHD risk, especially under conditions of folate deficiency. The results of similar studies have been ambiguous, probably due to the small sample sizes and complex nature of the MTHFD1 metabolic pathways and its compartmentalization between the cell nucleus and cytosol under different folate levels. The limitation of the present study is again the relatively small sample size. However, MTHFD1 rs2236225 was here identified as a CHD risk factor in both of the different study designs (i.e., case–control and family triads), which might at least in part compensate for this limitation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lesar Ida and Skapin Ana for technical assistance, and Christopher P. Berrie for English language editing.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcdd9060166/s1: Table S1: Differences for all of the variables tested between the control and CHD groups using simple statistical tests and logistic regression models; Table S2: Differences in all tested variables between control and CHD etiologic sub-groups, calculated using simple statistical tests; Table S3: Statistically significant and marginally significant differences in genotypes in four most common septal (VSD & ASD), LVOTO (AS) and conotruncal (TOF) defects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K.K. and K.G.; methodology, A.Š., M.V.G. and T.K.; software, A.Š.; formal analysis, A.Š. and M.V.G.; investigation, B.G. and U.M.; resources, I.M.-R. and K.G.; data curation, N.K.K. and A.Š.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K.K.; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, I.M.-R. and K.G.; project administration, I.M.-R.; funding acquisition, K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the National Medical Ethics Committee of the Republic of Slovenia (NMEC) (protocol code 57/02/13).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author on request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy of the study participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS), grant number J3-8207. The APC was funded by ARRS research programs No. P3―0124 and P1―0208.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.van der Linde D., Konings E.E., Slager M.A., Witsenburg M., Helbing W.A., Takkenberg J.J., Roos-Hesselink J.W. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;58:2241–2247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botto L.D., Lin A.E., Riehle-Colarusso T., Malik S., Correa A. Seeking causes: Classifying and evaluating congenital heart defects in etiologic studies. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2007;79:714–727. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhat V., Belaval V., Gadabanahalli K., Raj V., Shah S. Illustrated Imaging Essay on Congenital Heart Diseases: Multimodality Approach Part III: Cyanotic Heart Diseases and Complex Congenital Anomalies. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016;10:TE01–TE10. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/21443.8210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat V., Belaval V., Gadabanahalli K., Raj V., Shah S. Illustrated Imaging Essay on Congenital Heart Diseases: Multimodality Approach Part II: Acyanotic Congenital Heart Disease and Extracardiac Abnormalities. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016;10:TE01–TE06. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/21442.8040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO ICD-10. [(accessed on 17 August 2018)]. Available online: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en#/I50.1.

- 6.Abqari S., Gupta A., Shahab T., Rabbani M.U., Ali S.M., Firdaus U. Profile and risk factors for congenital heart defects: A study in a tertiary care hospital. Ann. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2016;9:216–221. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.189119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azhar M., Ware S.M. Genetic and Developmental Basis of Cardiovascular Malformations. Clin. Perinatol. 2016;43:39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng Y., Wang S., Chen R., Tong X., Wu Z., Mo X. Maternal folic acid supplementation and the risk of congenital heart defects in offspring: A meta-analysis of epidemiological observational studies. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8506. doi: 10.1038/srep08506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu S., Joseph K.S., Luo W., Leon J.A., Lisonkova S., Van den Hof M., Evans J., Lim K., Little J., Sauve R., et al. Effect of Folic Acid Food Fortification in Canada on Congenital Heart Disease Subtypes. Circulation. 2016;134:647–655. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xuan C., Li H., Zhao J.X., Wang H.W., Wang Y., Ning C.P., Liu Z., Zhang B.B., He G.W., Lun L.M. Association between MTHFR polymorphisms and congenital heart disease: A meta-analysis based on 9,329 cases and 15,076 controls. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:7311. doi: 10.1038/srep07311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen K.E., Rohlicek C.V., Andelfinger G.U., Michaud J., Bigras J.L., Richter A., Mackenzie R.E., Rozen R. The MTHFD1 p.Arg653Gln variant alters enzyme function and increases risk for congenital heart defects. Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:212–220. doi: 10.1002/humu.20830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai B., Zhang T., Zhong R., Zou L., Zhu B., Chen W., Shen N., Ke J., Lou J., Wang Z., et al. Genetic variant in MTRR, but not MTR, is associated with risk of congenital heart disease: An integrated meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e89609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pei L., Zhu H., Zhu J., Ren A., Finnell R.H., Li Z. Genetic variation of infant reduced folate carrier (A80G) and risk of orofacial defects and congenital heart defects in China. Ann. Epidemiol. 2006;16:352–356. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie L., Chen J.L., Zhang W.Z., Wang S.Z., Zhao T.L., Huang C., Wang J., Yang J.F., Yang Y.F., Tan Z.P. Rare de novo copy number variants in patients with congenital pulmonary atresia. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e96471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang B., Liu M., Yan W., Mao J., Jiang D., Li H., Chen Y. Association of SNPs in genes involved in folate metabolism with the risk of congenital heart disease. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 2013;26:1768–1777. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.799648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell L.E., Long J., Garbarini J., Paluru P., Goldmuntz E. Variants of folate metabolism genes and risk of left-sided cardiac defects. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2010;88:48–53. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willett W.C., Sampson L., Stampfer M.J., Rosner B., Bain C., Witschi J., Hennekens C.H., Speizer F.E. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1985;122:51–65. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szklarczyk D., Franceschini A., Wyder S., Forslund K., Heller D., Huerta-Cepas J., Simonovic M., Roth A., Santos A., Tsafou K.P., et al. STRING v10: Protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan R., Lee A., Lu Z., Liu A., Troendle J.F., Mills J.L. Association analysis of complex diseases using triads, parent-child dyads and singleton monads. BMC Genet. 2013;14:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-14-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Georgetown University Medical Center. [(accessed on 22 August 2018)]. Available online: https://sites.google.com/a/georgetown.edu/ruzong-fan/about.

- 21.Csaky-Szunyogh M., Vereczkey A., Urban R., Czeizel A.E. Risk and protective factors in the origin of atrial septal defect secundum--national population-based case-control study. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health. 2014;22:42–47. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samanek M. Boy:girl ratio in children born with different forms of cardiac malformation: A population-based study. Pediatr. Cardiol. 1994;15:53–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00817606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vereczkey A., Kosa Z., Csaky-Szunyogh M., Czeizel A.E. Isolated atrioventricular canal defects: Birth outcomes and risk factors: A population-based Hungarian case-control study, 1980-1996. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2013;97:217–224. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong D., Gu H., Zhang Y., Gong J., Nie Y., Wang J., Zhang H., Liu R., Hu S. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T and reduced folate carrier 80 G>A polymorphisms are associated with an increased risk of conotruncal heart defects. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2012;50:1455–1461. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2011-0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang J., Mei J., Jiang L., Jiang Z., Liu H., Ding F. MTHFR rs1801133 C>T polymorphism is associated with an increased risk of tetralogy of Fallot. Biomed. Rep. 2014;2:172–176. doi: 10.3892/br.2014.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw G.M., Lu W., Zhu H., Yang W., Briggs F.B., Carmichael S.L., Barcellos L.F., Lammer E.J., Finnell R.H. 118 SNPs of folate-related genes and risks of spina bifida and conotruncal heart defects. BMC Med. Genet. 2009;10:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng J., Lu X., Liu H., Zhao P., Li K., Li L. MTHFD1 polymorphism as maternal risk for neural tube defects: A meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 2015;36:607–616. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-2035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang T., Sun J., Chen Y., Xie H., Xu D., Li D. Associations of common variants in methionine metabolism pathway genes with plasma homocysteine and the risk of type 2 diabetes in Han Chinese. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics. 2014;7:63–74. doi: 10.1159/000365007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu H., Jin G., Wang H., Wu W., Liu Y., Qian J., Fan W., Ma H., Miao R., Hu Z., et al. Association of polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolizing genes and lung cancer risk: A case-control study in Chinese population. Lung Cancer. 2008;61:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saha T., Chatterjee M., Sinha S., Rajamma U., Mukhopadhyay K. Components of the folate metabolic pathway and ADHD core traits: An exploration in eastern Indian probands. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;62:687–695. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2017.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Field M.S., Kamynina E., Stover P.J. MTHFD1 regulates nuclear de novo thymidylate biosynthesis and genome stability. Biochimie. 2016;126:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Field M.S., Kamynina E., Agunloye O.C., Liebenthal R.P., Lamarre S.G., Brosnan M.E., Brosnan J.T., Stover P.J. Nuclear enrichment of folate cofactors and methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 (MTHFD1) protect de novo thymidylate biosynthesis during folate deficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:29642–29650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.599589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christensen K.E., Deng L., Leung K.Y., Arning E., Bottiglieri T., Malysheva O.V., Caudill M.A., Krupenko N.I., Greene N.D., Jerome-Majewska L., et al. A novel mouse model for genetic variation in 10-formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase exhibits disturbed purine synthesis with impacts on pregnancy and embryonic development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:3705–3719. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacFarlane A.J., Perry C.A., McEntee M.F., Lin D.M., Stover P.J. Mthfd1 is a modifier of chemically induced intestinal carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:427–433. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeng W., Liu L., Tong Y., Liu H.M., Dai L., Mao M. A66G and C524T polymorphisms of the methionine synthase reductase gene are associated with congenital heart defects in the Chinese Han population. Genet. Mol. Res. 2011;10:2597–2605. doi: 10.4238/2011.October.25.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christensen K.E., Zada Y.F., Rohlicek C.V., Andelfinger G.U., Michaud J.L., Bigras J.L., Richter A., Dubé M.P., Rozen R. Risk of congenital heart defects is influenced by genetic variation in folate metabolism. Cardiol. Young. 2013;23:89–98. doi: 10.1017/S1047951112000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldmuntz E., Woyciechowski S., Renstrom D., Lupo P.J., Mitchell L.E. Variants of folate metabolism genes and the risk of conotruncal cardiac defects. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2008;1:126–132. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.796342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo Q.N., Wang H.D., Tie L.Z., Li T., Xiao H., Long J.G., Liao S.X. Parental Genetic Variants, MTHFR 677C>T and MTRR 66A>G, Associated Differently with Fetal Congenital Heart Defect. Biomed Res. Int. 2017;2017:3043476. doi: 10.1155/2017/3043476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu D., Yang L., Shen S., Fan C., Zhang W., Mo X. Association between methionine synthase reductase A66G polymorphism and the risk of congenital heart defects: Evidence from eight case-control studies. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2014;35:1091–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00246-014-0948-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elizabeth K.E., Praveen S.L., Preethi N.R., Jissa V.T., Pillai M.R. Folate, vitamin B12, homocysteine and polymorphisms in folate metabolizing genes in children with congenital heart disease and their mothers. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017;71:1437–1441. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2017.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hassan F.M., Khattab A.A., Abo El Fotoh W.M.M., Zidan R.S. A66G and C524T polymorphisms of methionine synthase reductase gene are linked to the development of acyanotic congenital heart diseases in Egyptian children. Gene. 2017;629:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.07.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author on request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy of the study participants.