Abstract

Little is known regarding T cell translational regulation. We demonstrate that T follicular helper (TFH) cells use a previously unknown mechanism of selective messenger RNA (mRNA) translation for their differentiation, role in B cell maturation, and in autoimmune pathogenesis. We show that TFH cells have much higher levels of translation factor eIF4E than non-TFH CD4+ T cells, which is essential for translation of TFH cell fate-specification mRNAs. Genome-wide translation studies indicate that modest down-regulation of eIF4E activity by a small-molecule inhibitor or short hairpin RN impairs TFH cell development and function. In mice, down-regulation of eIF4E activity specifically reduces TFH cells among T helper subtypes, germinal centers, B cell recruitment, and antibody production. In experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, eIF4E activity down-regulation blocks TFH cell participation in disease pathogenesis while promoting rapid remission and spinal cord remyelination. TFH cell development and its role in autoimmune pathogenesis involve selective mRNA translation that is highly druggable.

Therapeutic small-molecule inhibition of eIF4E blocks TFH cell differentiation and controls autoimmune pathogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

T follicular helper (TFH) cells are CD4+ T helper (TH) cells that are critical for immune responses to infection and vaccination, but their aberrant accumulation is associated with autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis (MS) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) among others (1). TFH cells promote differentiation of B cells to high-affinity antibody-producing plasma cells through formation of germinal centers (GCs) (2). TFH cells have a central role in the formation and maintenance of ectopic lymphoid follicles (ELFs), which are transitory inducible immunologic centers that generate specific antigen responses, but are also associated with autoimmune disorders (3). TFH cells can be found within ELFs that have established roles in autoimmune disease, along with inflammatory TH1, TH17, and clusters of B cells, which promote the survival of TFH cells (4, 5). While TFH cells represent a potentially attractive therapeutic target for treatment of autoimmune diseases, there have been no specific pharmacologic inhibitors of TFH cells, and their causal role in autoimmune pathogenesis needs greater clarity.

Because selective expansion of TFH cells that recognize self-antigen can result in autoimmune disease, the initiation, commitment, differentiation, and maintenance of TFH cells is regulated by a complex set of coordinated signals. First, T cell receptor (TCR) and CD28, which provide costimulatory signals for T cell activation and survival, are engaged and promote nuclear localization of transcription factors nuclear factor of activated T1 (NFAT1) and NFAT2 (1, 6), transcriptional coactivator POU2AF1 (7), and expression of immune checkpoint proteins inducible T cell Costimulator (ICOS) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) (8). Next, TFH cell differentiation occurs, initiating with activation of protein kinases mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTORC2 (9, 10), and up-regulation of TFH cell lineage–defining transcription factor, B cell CLL/lymphoma 6 (BCL6) (11–13), which coordinates many functional programs including T cell production of interleukins IL-4 and IL-21 and expression of chemokine receptor CXCR5. CXCR5 plays a critical role in TFH cell function by promoting the migration of T cells to B cell zones and their maintenance within these follicles. TFH cells are further maintained in GCs by stable engagement of GC B cells that involves multiple points of contact, including checkpoints and the lymphocyte signaling molecules PD-1, SLAM, CD28, and OX40 (8).

While transcriptional regulation of TFH cells has been well studied (14), the regulation of TFH cell mRNA translation has not. Translational regulation and, in particular, a means for selective mRNA translation of TFH cell mRNAs might be critical in TFH cell development, given the complex multifactorial process required for TFH cell differentiation and immune function. In general, mechanisms of translational control remain unexpectedly uncharacterized in immune cells, including TH cells. The canonical translation initiation process involves the m7 guanosine triphosphate (m7GTP) (cap) binding protein eIF4E, which forms a translation preinitiation complex (PIC) with core scaffolding initiation factor eIF4G and adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–dependent RNA helicase eIF4A. The PIC, along with a number of other translation initiation factors, assembles the translation initiation complex at the mRNA 5′ cap, recruits the 40S ribosome subunit, and scans the mRNA in search of the downstream initiation codon (often an AUG) (15). eIF4E availability is controlled by its sequestration by the eIF4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs), which compete with eIF4G for eIF4E binding and are inhibited by mTORC1 phosphorylation (16). It is therefore notable that TFH cells are dependent on high levels of mTORC1 (and mTORC2) activity (9).

Here, we investigated the translational regulation required for CD4+ T cells to differentiate to TFH cells and its contribution to TFH cell participation in pathogenesis in autoimmune disease in animal models. We demonstrate that TFH cells intrinsically express much higher levels of eIF4E compared to non-TFH CD4+ T cells, which we show is essential for their selective translation of mRNAs that specify TFH cell differentiation and function. These mRNAs constitute established effectors that are critical for TFH cell development and its role in B cell maturation and antibody expression, and include CD28, NFAT1/2, CXCR5, BCL6, ICOS, PD-1, SLAMF1, and others. Their translation in TFH cells, unlike other CD4+ T cell mRNAs, is shown to be acutely inhibited by even moderate down-regulation of eIF4E activity, which blocked CD4+ T cell differentiation to TFH cells.

We characterized the role of TFH cell–selective mRNA translation in Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis (EAE), a rodent model of MS, an autoimmune disorder of the central nervous system (CNS). EAE and MS are characterized by inflammatory autoreactive T cells that infiltrate the spinal cord and brain (3), generate ELFs in the CNS that perpetuate chronic inflammation and demyelination, and are located proximally to demyelinated areas associated with increased pathogenesis of MS (3). TFH cells also circulate at higher frequencies in the blood and CNS of patients with MS (17, 18). We show that pharmacologic reduction of the high levels of eIF4E activity found in TFH cells, either by systemic administration of a small-molecule inhibitor or by TFH cell–specific inducible short hairpin RNA (shRNA), ameliorates EAE disease even when administered late after disease onset; reverses spinal cord demyelination; diminishes ELF formation, autoimmune B cell maturation, and antibody expression; and blocks recruitment of pathogenic T cells to the CNS. Our study further clarifies the role of TFH cells in promotion of autoimmune disease, elucidates a previously unknown mechanism by which selective translation specifies TFH cell differentiation, and demonstrates the specific therapeutic targeting of pathogenic TFH cells by down-regulating eIF4E activity.

RESULTS

Partial pharmacologic inhibition of eIF4E activity inhibits CD4+ T cell differentiation to TFH cells but not other TH cell subsets

Because TH1 and TFH cells require high levels of mTORC1 activity, we determined the sensitivity of all TH cell subsets to reduction in eIF4E activity in their differentiation and effector functions. The small-molecule inhibitor 4EGI-1 blocks engagement of eIF4E with eIF4G, thereby down-regulating eIF4E-mediated mRNA translation (19). Dose level and frequency of administration for 4EGI-1 to mice were established at 25 mg/kg daily as a low dose, the same as in the tumor inhibition setting (20). At this dose and frequency, 4EGI-1 reduced protein synthesis in isolated splenocyte CD4+ T cells by only 20 to 25% (fig. S1A) and eIF4GI interaction with eIF4E by ~50% and increased eIF4E binding to the inhibitory 4E-BPs, shown by m7GTP cap chromatography and immunoblot analysis (fig. S1B). 4EGI-1 therefore only moderately down-regulated eIF4E/eIF4G binding, consistent with a moderate decrease in eIF4E-dependent protein synthesis.

We used animal models that are well established to specifically induce the different TH cell subsets to determine the effect of down-regulation of eIF4E activity on their differentiation and function. This is preferable to in vitro differentiation models that lack the complex regulatory and development environments and do not fully test TH cell subset differentiation. To assess the effect of down-regulation of eIF4E activity specifically on TH1 and TH17 cells, C57BL/6 mice were infected subdermally with Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) in the ear pinnae, a strong classic trigger for TH1 and TH17 responses (21), and then treated with vehicle or 4EGI-1 throughout infection (Fig. 1A). Down-regulation of eIF4E activity at these levels had no significant effect on number and differentiation of TH1 cells using established markers [T-bet+ or interferon-γ (IFN-γ+)] or TH17 cells (RORγT+ or IL17A+) in the skin, or on effector functions measured by levels of general skin inflammation, ear thickness, and skin neutrophil levels (Fig. 1, B to E, and fig. S1, C to J). Moreover, differentiated TH1 or TH17 cells treated in vitro with 4EGI-1 (fig. S1K) were not altered in levels of secretion of IFN-γ or tumor necrosis factor–α (TH1 cells), or IL-17A or IL-17F (TH17 cells) (fig. S1, L to O). Partial eIF4E inhibition therefore does not affect TH1 or TH17 cell induction or function in an established immune model.

Fig. 1. Moderate pharmacologic down-regulation of eIF4E activity inhibits development of TFH but not TH1, TH17, TH2, or regulatory T cells.

(A) Mice infected subdermally in ear pinnae with S. aureus, treated with vehicle (veh) or 4EGI-1. (B to E) Skin CD4+ T cells that are (B) T-bet+, (C) IFN-γ+, (D) RORγt+, and (E) IL-17+. (F) Mice intratracheally sensitized with A. fumigatus, treated with vehicle or 4EGI-1. (G to I) Lung CD4+ T cells that are (G) GATA-3+, (H) IL-13+, and (I) Foxp3+. (J) Mice immunized with OVA/alum, treated with vehicle or 4EGI-1. (K) Representative flow cytometry identification of CD4+ TFH cells in mice. (L and M) Quantification of CD4+ T and TFH cells for splenic (L) CD4+ T cells and (M) TFH cells. (N) OT2 cells were activated, transduced with lentiviruses, transferred into congenic CD45.1 mice, and Dox-induced for NS or eIF4E shRNAs. (O) eIF4E levels determined by flow cytometry in transduced permeabilized spleen OT2 T cells. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. (P and Q) Numbers of (P) splenic OT2 T cells and (Q) OT2 T cells that formed TFH cells at day 15 after transfer. (R) OT2 T cells isolated and activated as in (N), CFSE-labeled, treated in vitro with vehicle or 20 μM 4EGI-1 for 1 hour at 37°C, washed, transferred into CD45.1 recipients, and OVA/alum-immunized 24 hours later, frequency of divided OT2 T cells determined at day 3. ns, not significant, **P < 0.01, ± SEM by two-tailed unpaired t test from three or more independent studies. Dotted line, levels in control mice.

To determine the effect of moderate eIF4E inhibition on TH2 and regulatory T (Treg) cells, we used an established model of airway disease caused by repeated sensitization to Aspergillus fumigatus conidia (A. fumigatus), which predominantly promotes a TH2 cell response along with Treg cell induction (22–24). Treatment of C57BL/6 mice with vehicle or 4EGI-1 throughout sensitization (Fig. 1F) had no effect on levels of pulmonary TH2 cells, determined with established markers (GATA3+ or IL-13+), Treg cells (Foxp3+), eosinophils (SiglecF+ CD11c−), mucin production, or airway inflammation (Fig. 1, G to I, and fig. S2, A to G). Furthermore, treatment of in vitro–differentiated TH2 cells with 4EGI-1 did not affect secretion of IL-13, a pathogenic TH2 cytokine, indicative of TH2 function (fig. S2E). Therefore, moderate eIF4E inhibition does not alter TH2 or Treg cell–dependent differentiation or function.

Last, to examine the effect of eIF4E down-regulation on TFH cell development, C57BL/6 mice were immunized with ovalbumin in alum (OVA/alum), an established method that primarily induces TFH cells, only slightly induces TH2 cells, and does not induce TH1 or TH17 cells (25). Animals were treated with vehicle or 4EGI-1 throughout the response (Fig. 1J). 4EGI-1 treatment did not significantly reduce overall CD4+ T cell numbers, whereas TFH cells, identified using well-established double-positive biomarkers CXCR5 and PD-1 on CD4+ T cells (25), were significantly reduced in the spleen (3.5-fold; Fig. 1, K to M).

To understand the acute sensitivity of CD4+ T cell to commit to TFH cell development to modest down-regulation of eIF4E activity, we developed flow cytometry cell permeabilization quantification of eIF4E and eIF4GI levels. We compared eIF4E and eIF4GI levels in TFH cells (CD4+PD1+CXCR5+) to non-TFH CD4+ T cells (CD4+PD1−CXCR5−; fig. S2H) in mice immunized against OVA/alum as described in Materials and Methods. TFH cells had 2.6-fold increased levels of eIF4E and 1.5-fold increased levels of eIF4GI (the major eIF4G member) compared to non-TFH CD4+ T cells based on flow cytometry staining of permeabilized cells (fig. S2, I and J). Because flow cytometry antibody staining of permeabilized cells may underestimate protein levels, immunoblot analysis of eIF4E and eIF4GI levels was carried out on fluorescence-activated cell sorted (FACS) TFH and non-TFH CD4+ T cells (fig. S2K) from OVA/alum-immunized mice. eIF4E levels were approximately fivefold higher, and eIF4GI levels approximately threefold higher in TFH compared to non-TFH CD4+ T cells. Thus, while flow cytometry is a reliable method for intracellular protein quantitation that requires few cells unlike immunoblot analysis, it underquantifies eIF4E and eIF4GI levels by about half. These data suggest a potential greater requirement for high levels of eIF4E in TFH cell development and function, which we explored next.

Intrinsically high levels of eIF4E are essential for TFH cell translation and differentiation

We determined whether the impact of down-regulation of eIF4E activity on TFH cell differentiation is CD4+ T cell intrinsic by engineering reduced levels of eIF4E in a select CD4+ T cell compartment. CD45.2 OT2 T cells, which primarily recognizes OVA peptide, were stimulated in vitro by αCD3/αCD28 to enable transduction by lentivirus vectors expressing doxycycline (Dox)–inducible nonsilencing (NS) or eIF4E shRNAs, puromycin-selected, transferred into CD45.1 congenic recipients that were then Dox-treated, and activated by administration of OVA/alum (Fig. 1N). The eIF4E shRNA was previously established to be eIF4E specific (26). eIF4E levels in shRNA-transduced OT2 T cells was reduced by ~25% in blood and spleen, as quantified by flow cytometry (Fig. 1O and fig. S2L), and reduced 50% by immunoblot (fig. S2L). Reduction in eIF4E levels by half in OT2 cells resulted in no change in OT2 T cell levels but a threefold reduction in levels of splenic OT2 TFH cells (Fig. 1, P and Q). Moreover, the ~25% decrease in eIF4E-directed protein synthesis mediated by 4EGI-1 (fig. S1A) did not impair proliferation of activated OT2 T cells. 4EGI-1–treated and carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)–labeled OT2 T cells were adoptively transferred into congenic CD45.1 recipients before OVA/alum immunization (Fig. 1R). There was no difference in the percentage of divided OVA/alum-stimulated OT2 cells regardless of down-regulation of eIF4E activity. Thus, the high levels of CD4+ T cell–intrinsic eIF4E is required for TFH cell differentiation but not proliferation.

High levels of eIF4E are required for selective translation of mRNAs that drive TFH cell differentiation and function

We next identified which CD4+ T cell mRNAs require intrinsically high levels of eIF4E for their translation in TFH cell development. We immunized mice with OVA/alum, treated them with vehicle or 4EGI-1 (Fig. 2A), and then isolated CD4+ T cells and performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on total mRNA (transcriptome) and well-translated (≥4 ribosome) polysome-associated mRNA, to identify individual mRNAs and their translation activity on the basis of ribosome content, normalized to total mRNA level (translatome). Because 4EGI-1 at 25 mg/kg does not reduce CD4+ T cell numbers but, as shown later, does block their ability to increase eIF4E levels that are essential for CD4+ T cells to become TFH cells, by analyzing the entire CD4+ T cell population, this provides an unbiased identification of CD4+ T cell mRNAs that are dependent on high levels of eIF4E for their translation and are required for TFH cell differentiation. Raw and analyzed transcriptomic and translatomic RNA-seq data are found in dataset S1. The open-source analysis tool Ribosomal Investigation and Visualization to Evaluate Translation (RIVET) (27) was used for genome-wide transcriptomic and translatomic analysis. We identified 641 mRNAs that were significantly altered in abundance and not translation activity (transcription alone), 667 mRNAs altered in translation alone without a change in abundance, and 64 mRNAs altered in both transcription and translation (Fig. 2, B and C). Most of the mRNAs were down-regulated in transcription and/or translation by moderate inhibition of eIF4E activity, with 61% of mRNAs reduced in abundance and 79% reduced in translation (Fig. 2C and fig. S3A).

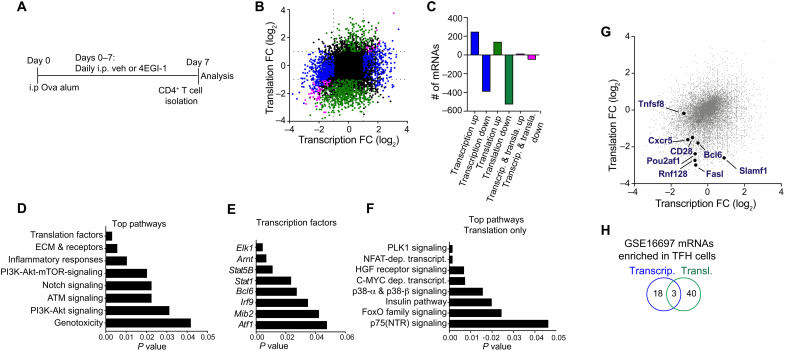

Fig. 2. Effect of down-regulation of eIF4E activity on mRNAs and molecular pathways in CD4+ T cells.

(A) Scheme for OVA/alum immunization and treatment with vehicle or 4EGI-1, isolation of CD4+ T cells, genome-wide translatomic analysis by polysome profiling, and genome-wide transcriptomic analysis by mRNA sequencing. (B) Scatter plot highlighting genes/mRNAs regulated by 4EGI-1 at the level of transcription (blue), translation (green), or both (pink). (C) Numbers of genes/mRNAs affected by 4EGI-1 down-regulation of eIF4E activity. Color code is the same as in (B). (D to F) Top pathway, mRNAs, and their translation that are down-regulated by 4EGI-1 treatment. (D) Top pathways down-regulated with eIF4E moderate inhibition by 4EGI-1. (E) Top transcription factors reduced in mRNA level and/or translation with 4EGI-1 treatment. (F) Top pathways translationally down-regulated with 4EGI-1 treatment. PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; ATM, ataxia telangiectasia mutated. (G) Annotation of select genes/mRNAs that are highlighted in pathway analysis and required for TFH cell differentiation and maintenance that rely on high eIF4E levels for transcription and/or translation. Data from two independent studies. Color code is the same as in (B). (H) Number of genes/mRNAs enriched in TFH cells that are regulated by transcription, translation, or both. Comparison of three or more groups was performed by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis, and data from only two groups were analyzed by a two-tailed unpaired t test. FC, fold change.

mRNAs reduced in abundance and/or translation by blocking induction of high levels of eIF4E activity in CD4+ T cells, informed top pathway characterization, which included down-regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mTOR signaling protein levels, extracellular matrix (ECM), membrane receptor expression proteins, and inflammatory immune response proteins, among others, which are all involved in TFH cell differentiation and function (Fig. 2D). Transcription factors down-regulated either in transcription, translation, or both by 4EGI-1 treatment included the canonical established transcription factors that regulate TFH cell development, including BCL6, signal transducer and activator of transcription 1, and ELK1 [E twenty six (ETS)-like transcription factor 1], a member of the ternary complex factor induced by c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling (Fig. 2E).

Pathway analysis of mRNAs that were only translationally down-regulated by moderate inhibition of eIF4E included calcineurin-regulated NFAT-dependent transcription, c-MYC–dependent activation, and FoxO family signaling, among others (Fig. 2F). NFAT1 and NFAT2 signaling is essential for TFH cell development, including IL-21 production (6), MYC activated pathways that are involved in IL2+ T cell development and are precursors of TFH cells (28), and FoxO signaling controls expression of BCL6 (29). While the list of mRNAs down-regulated by reduced eIF4E activity at both transcriptional and translational levels was small, pathway analysis identified those encoding gap and tight junction functions that are required for retention of TFH cells in GCs (fig. S3B) (28). Notably, Egr transcription factor mRNAs were reduced in expression (fig. S3C) and are required for expression of BCL6 and c-Myc (30). Thus, blocking induction of high levels of eIF4E activity found in TFH cells selectively impairs translation of mRNAs that are essential for cellular programs required for CD4+ T cell differentiation to TFH cells.

Transcriptomic and translatomic data were analyzed by log2 scatter plots to simultaneously visualize changes in specific mRNA abundance and/or translation with moderate reduction in eIF4E activity (Fig. 2G). Among the mRNAs strongly transcriptionally and/or translationally down-regulated by moderately reducing eIF4E activity and/or blocking high level induction were those encoding well-established essential proteins for TFH cell development and function. These included transcription factors that are essential for TFH cell differentiation (CD28, Pou2af1, and Bcl6), factors that promote CD4+ T cell migration into GCs (e.g., CXCR5), and expression of co-receptors involved in TFH cell development, function, and maintenance (Slamf1, Fasl, Tnfsf8, and CD28). Protein levels for BCL6, PD-1, SLAM, CD28, and CXCR5, determined by flow cytometry, were also consistent and reduced in 4EGI-1–treated CD4+ T cells, shown later in Fig. 3.

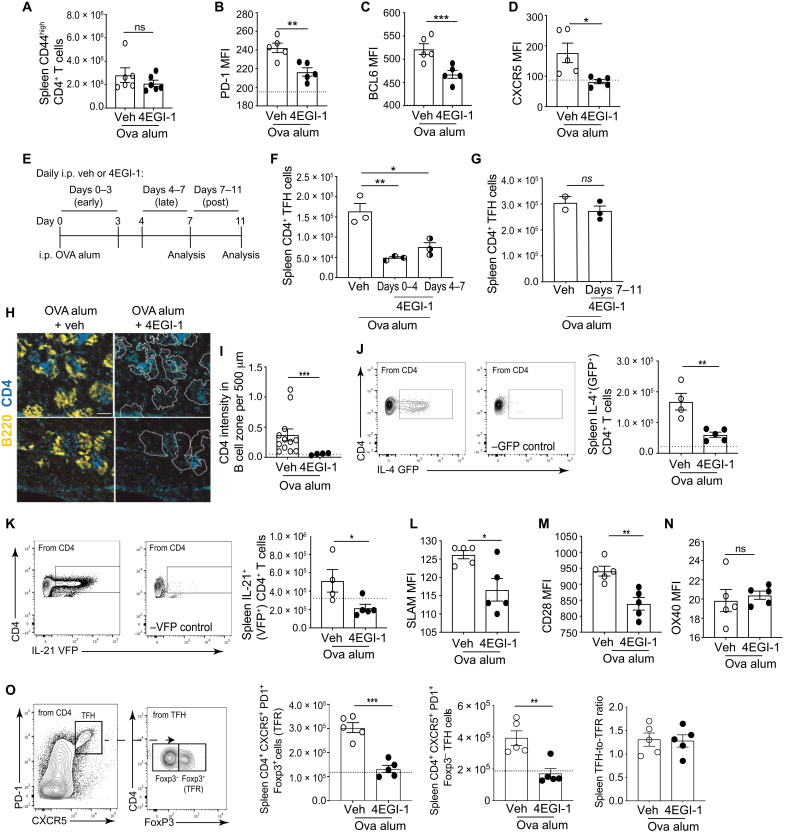

Fig. 3. High levels of eIF4E are required for expression of costimulatory proteins involved in TFH cell development and GC B cell maintenance.

(A to D) OVA/alum immunization and treatment with vehicle or 4EGI-1 as in Fig. 1A. Flow cytometry quantification of CD4+ T cell expression of (A) CD44, (B) PD-1, (C) intranuclear BCL6, and (D) CXCR5. (E to G) High eIF4E activity is essential for TFH cell differentiation but not maintenance. (E) Scheme for testing TFH cell differentiation versus maintenance. (F) Quantification of splenic TFH cells reduced in eIF4E activity early or late after induction or (G) after induction. (H) OVA/alum immunization, treatment with vehicle or 4EGI-1 as in (A). Shown, representative immunofluorescence images of spleen stained for CD4+ T cells (blue) and B220+ B cells (yellow). B cell follicles outlined and overlaid on CD4+ T cell stain (dotted line). (I) Quantification of 12 images from three independent studies of CD4+ T cells in B cell follicles as in (H) normalized to a standard area. Scale bar, 200 μm. (J to N) Quantification of splenic CD4+ T cells that express proteins for (J) IL-4 (GFP+), (K) IL-21 (VFP+), (L) SLAM, (M) CD28, or (N) OX40. (O) Mice immunized with OVA/alum as in (A), treated with 4EGI-1 for 14 days and TFR cells quantified. Dotted line, levels present in control mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ± SEM by two-tailed unpaired t test from three or more independent studies.

We also queried our transcriptomic and translatomic results for 4EGI-1 down-regulation of eIF4E activity in CD4+ T cells against a list of mRNAs that were previously found to be specifically increased in expression in TFH cells compared to non-TFH CD4+ T cells (dataset S2) (11). We identified 18 mRNAs in both datasets that are regulated in transcription alone, compared to 40 mRNAs in our dataset down-regulated by translation alone with eIF4E inhibition (Fig. 2H). We can conclude that translation of a small group of mRNAs is specifically and acutely dependent on high levels of eIF4E to program TFH cell differentiation and function and are down-regulated by 4EGI-1 treatment.

BCL6-dependent TFH cell differentiation is blocked by moderate eIF4E inhibition

We tested the dependence on high levels of eIF4E for expression of receptors, transcription factors, and cytokines identified by genome-wide analysis that are involved in TFH cell differentiation and maintenance. Animals were immunized with OVA/alum with and without moderate inhibition of eIF4E function by 4EGI-1 as in Fig. 1A. In agreement with genome-wide transcriptomic/translatomic analysis, 4EGI-1 down-regulation of eIF4E function and prevention of eIF4E induction did not affect CD4+ T cell activation (CD44high) (Fig. 3A) but did reduce the levels of PD-1, BCL6, and CXCR5 on splenic CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3, B to D). To determine whether high levels of eIF4E activity are required for TFH cell differentiation, maintenance, or both, we carried out three treatment schedules in OVA/alum-immunized mice: early (4EGI-1, days 0 to 3) and late (4EGI-1, days 4 to 7) during TFH differentiation, or after the TFH induction peak (4EGI-1, days 7 to 11). TFH cell number was decreased threefold when mice were treated with the eIF4E inhibitor whether early or late during TFH induction, while moderate inhibition of eIF4E activity did not reduce TFH cell numbers following OVA induction (Fig. 3, E to G). Therefore, moderate reduction of eIF4E activity and blockade of its induction achieved by 25 mg/kg 4EGI-1 treatment specifically impair TFH cell development but not differentiated TFH cell maintenance nor CD4+ T cell activation. It is shown later that a high dose of 4EGI-1 and greater inhibition of eIF4E activity does reduce lineage commitment and maintenance of TFH cells.

CXCR5 is central to CD4+ T cell migration into the B cell zone. Selective translation of CXCR5 mRNA suggests a foundational mechanism for control by levels of eIF4E in TFH cell development and function. 4EGI-1 administration almost abolished infiltration of CD4+ T cells (blue) into B cell zones (yellow, outlined) (Fig. 3, H and I). Once within the B cell zone, TFH cells produce IL-4 and IL-21 and express co-receptors for engagement of GC B cells. We therefore used cytokine reporter mice to assess the sensitivity to eIF4E down-regulation on in vivo production of endogenous IL-4 [green fluorescent protein (GFP+)] and IL-21 [verde fluorescent protein (VFP+)]. 4EGI-1 decreased by 2.5-fold the total number of CD4+ T cells producing IL-4 or IL-21 cytokines in the spleen following OVA/alum immunization (Fig. 3, J and K). We further investigated expression of proteins required for engagement of GC B cells within follicles and continued lineage commitment of TFH cells. CD4+ T cell expression of SLAM and CD28 was decreased following 4EGI-1 treatment, but expression of OX40 was not affected, consistent with our genome-wide studies (Fig. 3, L to N). In summary, by surveying the entire CD4+ T cell population after moderate reduction and/or prevention of eIF4E induction, T cell activation and proliferation were found to be unaffected, preserving the reservoir of CD4+ T cells, whereas TFH cell development was significantly inhibited.

We also investigated the requirement for high levels of eIF4E activity on T follicular regulatory (TFR) cell development as these cells, like TFH cells, rely on CXCR5, BCL6, and CD28 for differentiation (31). We investigated whether TFR cell levels were increased by eIF4E inhibition, which could alternately explain TFH cell inhibition by down-regulation of eIF4E activity. However, similar to TFH cells, TFR cells (PD1+CXCR5+FOXP3+) were reduced threefold by 4EGI-1 down-regulation of eIF4E activity, which was measured at day 14, the peak of the TFR cell response (Fig. 3O) (32). At this time point, levels of FOXP3− cells within the PD1+CXCR5+ compartment (TFH cells) were decreased to a similar extent by 4EGI-1 treatment, as confirmed by the unchanged TFH-to-TFR ratio. Foxp3 was not transcriptionally or translationally affected in the CD4+ T cell compartment with partial eIF4E blockade (dataset S1). This indicates that the reduction in TFR cells is due to a decrease in the total CXCR5+PD1+ population and is Foxp3 independent. Thus, the expression and translation of mRNAs that program TFH cell differentiation (CD28 and BCL6), migration (CXCR5), function (IL-4 and IL-21), and maintenance (SLAM and CD28) all require high levels of eIF4E activity.

Down-regulation of eIF4E activity selectively inhibits GC B cell development and plasma cell formation

CXCR5 is essential for TFH cell development because it mediates CD4+ T cell migration into the follicles (8). TFH cell differentiation and maintenance in the GC is also dependent on expression of co-receptors for engagement of GC B cells (8). We therefore investigated the effect of down-regulation of eIF4E activity on the splenic B cell compartment following OVA/alum vaccination by quantifying total B cells, OVA/alum-induced B cell subsets, and GC light and dark zones (fig. S4, A to H). Reduced eIF4E activity decreased the number of total GC B cells by threefold, including those in the CD86+ light zone, CXCR4+ dark zone, and GC B cells that are class-switched immunoglobulin G+ (IgG1+) or OVA specific (Fig. 4, A to E, and fig. S4, I and J). In addition, with reduced eIF4E activity, the number of total plasmablasts and plasma cells was reduced twofold, OVA-specific IgG1 antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) were almost abolished, and serum OVA-specific IgG1 antibody was reduced by half (Fig. 4, F to I). Because more than 90% of B cells that class-switch following induction by OVA/alum are IgG1 (33, 34), we only characterized this subtype. Thus, moderate inhibition of eIF4E activity significantly impairs development of GC B cells and their maturation to antigen-specific plasma cells following immunization. Moreover, reduced eIF4E activity during S. aureus infection (Fig. 1A) or allergic sensitization with A. fumigatus (Fig. 1F) also strongly reduced formation of TFH cells and GC B cells in cervical lymph nodes (CLNs) (fig. S5, A and B, and fig. S5, C and D, respectively). There was no reduction in TH1 (CD4+ T-bet+) and TH17 (CD4+ RORγt+) cells (fig. S5, E and F); secretion of class-switched immunoglobulins was strongly reduced (fig. S5G). 4EGI-1 down-regulation of eIF4E activity caused a similar reduction in TFH cells in mediastinal LNs (MedLNs) (fig. S5, H and I) but without reduction in TH2 (CD4+ GATA3+) and Treg (CD4+ Foxp3+) cells (fig. S5, J and K), whereas GC B cells and class-switched Igs were strongly reduced (fig. S5, L to N). In summary, three independent inflammatory stimuli all showed similar inhibition of TFH cell development and function and, consequently, inhibition of GC formation and B cell maturation with moderate reduction in eIF4E activity.

Fig. 4. Down-regulation of eIF4E activity inhibits GC B cell and plasma cell development.

(A) Representative flow cytometry identification of GC B cells (B220+ Fas+ GL7+) from mice immunized with OVA/alum-administered vehicle, 4EGI-1, or alum-only control mice, analyzed at day 7 as in Fig. 1A. FAS, fatty acid synthase. (B to G) Quantification of OVA/alum-treated mice with vehicle or 4EGI-1 for (B) splenic GC B cells, splenic GC B cells that are (C) CD86+ (light zone), (D) CXCR4+ (dark zone), (E) IgG1 class-switched, (F) plasmablasts, and (G) plasma cells. (H) Quantification of OVA-specific IgG1 ASCs treated as in (A) per 106 splenocytes. Ab, antibody. (I) Serum levels of OVA-specific IgG1 antibody. Dotted lines, levels present in control mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 ± SEM by two-tailed unpaired t test from three or more independent studies. OD, optical density.

Moderate eIF4E inhibition causes immediate decline in human and mouse CD4+ T cell BCL6 protein levels

CD4+ lymphocytes isolated from Ova/alum-immunized mice were treated with 4EGI-1 in culture for a brief duration to determine the immediate effect on overall protein synthesis and the specific effect on protein levels, given the short half-life reported for the BCL6 protein (8). When treated in vitro at 20 μM, 4EGI-1 reduced protein synthesis by threefold within 4 hours in a dose-responsive manner without reducing cell viability (Fig. 5, A and B). There was a rapid twofold reduction in BCL6 protein levels, demonstrating a requirement for continuous BCL6 mRNA translation to maintain BCL6 protein levels (Fig. 5C). PD-1, CXCR5, and ICOS proteins are long-lived and, accordingly, were unchanged during this short time course of eIF4E inhibition (Fig. 5, D to F) but, as shown in Fig. 2, are dependent on high levels of eIF4E for translation of their mRNAs. We also treated CD4+ T cells isolated from Ova/alum-treated mice with cycloheximide to block protein synthesis and measured relative half-lives for BCL6, ICOS, and PD-1 proteins (fig. S6, A to C). BCL6 protein demonstrated a short half-life of less than 4 hours, whereas PD-1 and ICOS were stable throughout the 8-hour period of follow-up.

Fig. 5. Maintenance of BCL6 expression in mouse CD4+ T cells and TFH cells in human lymph node requires continuous translation by a high level of eIF4E.

(A to F) CD4+ T cells from mice immunized with OVA/Alum were incubated with increasing (0 to 25 μM) concentrations of 4EGI-1 for 4 hours. (A) Quantification of protein synthesis activity by surface sensing of translation (SUnSET) assay. (B) CD4+ T cell viability, (C) MFI of intranuclear BCL6, (D) CXCR5, (E) PD-1, and (F) ICOS. (G and H) From the human TFH cell isolated population, TFH cells were identified as (G) PD1+ and CXCR5+ double positive and quantified for (H) BCL6+ (red; CD4+ CD45RO+ CXCR5+ PD1+ BCL6+ ICOS+). (I to L) Human lymph node cells were incubated with 0-30 μM 4EGI-1 overnight, and CD4+ CD45RO+ T cells quantified for expression of surface CXCR5, ICOS, PD-1, and intranuclear BCL6 from 3 independent human lymph nodes. Data normalized to percent of control (no treatment). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ± SEM. Comparison of three or more groups was performed by a one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis; data from only two groups were analyzed by a two-tailed unpaired t test from three or more independent analyses.

To examine human TFH cells, we obtained reactive but nonmalignant human LN biopsy samples containing TFH cells. LNs were dissociated and cell suspensions treated overnight with 4EGI-1. TFH cells were quantified by flow cytometry (CD4+ CD45RO+ PD1+ CXCR5+ BCL6+ ICOS+) (fig. S6, D to H). Three independent specimens from three different patients showed rapidly reduced levels of BCL6 protein but not CXCR5, ICOS, or PD-1 in activated LN CD4+ T cells treated with 4EGI-1, with no effect on cell viability (fig. S6, I to K, and Fig. 5, I to L).

Onset, progression, and pathogenesis of EAE disease and CNS ELF formation are blocked by moderate inhibition of eIF4E

TFH cells are implicated in the pathogenesis of EAE, but their causal role is not fully established. With the ability to pharmacologically block TFH cell development by down-regulating eIF4E activity and blocking its high level induction, we investigated the impact of moderate eIF4E inhibition on development of EAE, CNS ELFs, and inhibition of spinal cord demyelination. We induced active EAE by myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide (MOG)33–55/Freund’s complete adjuvant (FCA) injection, and then treated animals with vehicle or 4EGI-1 from the time of initiation of EAE throughout progression (Fig. 6A). Mice receiving 4EGI-1 exhibited significantly reduced clinical EAE severity (Fig. 6B) and disease-associated weight loss (Fig. 6C). Moderate inhibition of eIF4E reduced TFH cells in the spleen (threefold; Fig. 6D) and CD4+ T cells in the spinal cord (sevenfold; Fig. 6E) and brain (threefold; Fig. 6F). eIF4E moderate inhibition reduced the percentage of CD4+ T cells within the CD45+ population in spinal cord and brain by fivefold and threefold, respectively (Fig. 6, G to I), and those producing IFN-γ or IL-17A, which were almost abolished in spinal cord and reduced threefold in brain (Fig. 6, J to M). Notably, TFH cells that migrate to the CNS recruit and retain inflammatory TH1 and TH17 cells, which perpetuate ELFs, and with B cells, the survival of TFH cells (4, 5). Therefore, it would be expected that impairing TFH cell development by moderate inhibition of eIF4E would secondarily block the recruitment of TH1 and TH17 cells MOG/FCA-primed in the spleen and draining LNs. However, direct effects of down-regulation of eF4E activity on TH1 and TH17 cells and their trafficking, while not observed in our studies using model systems, also cannot be excluded. Accordingly, overall immune cell infiltration in spinal cord was, in fact, strongly blocked by 4EGI-1 reduction of eIF4E activity (Fig. 6, N and O).

Fig. 6. Onset, progression, and pathogenesis of EAE disease are blocked by moderate inhibition of eIF4E.

(A) Scheme for induction of active EAE by MOG/FCA with daily treatment of vehicle or 4EGI-1 (25 mg/kg). (B) Daily clinical scores of EAE mice treated with vehicle or 4EGI-1. (C) Relative weight of animals at 14 days following onset of EAE disease. (D to F) Quantification at day 21 of EAE for (D) spleen CD4+ TFH cells, (E) spinal cord (SC) CD4+ T cells, and (F) brain CD4+ T cells. (G) Representative flow cytometry of percentage of CD4+ T cells in spinal cord at day 21 of EAE. (H and I) Percentage of CD4+ in CD45+ T cells in spinal cord and brain, respectively at day 21 of EAE. (J to M) At day 21 of EAE, (J) spinal cord CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ+ or (K) IL-17A+, (L) brain CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ+, or (M) IL-17A+. (N) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained cross sections of spinal cords. Clusters of blue nucleoli identify cell infiltration. Scale bar, 500 μm. (O) Quantification of cell infiltration into spinal cord. Dotted line, levels in control animals with no EAE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 ± SEM. Comparison of three or more groups was performed by a one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis; data from only two groups were analyzed by a two-tailed unpaired t test from three or more independent studies.

The 4EGI-1 reduction of eIF4E activity during EAE prevented demyelination of the spinal cord, with treated animals displaying near-normal levels of myelination (~98%) (Fig. 7, A and B). Formation of ELFs is characterized by clusters of CD4+ T cells and B cells in the spinal cords of EAE mice. ELFs were substantially reduced by treatment with 4EGI-1 in EAE mice, coincident with strongly reduced numbers of CD4+ T cells and B cells, in contrast to their abundance and close proximity in the spinal cords of EAE control untreated mice (Fig. 7, C to E). TFH cell differentiation is therefore dependent on high levels of eIF4E activity, as is the presence of TFH cells in the CNS and formation of ELFs, which are associated with EAE pathology. We can conclude that the high levels of eIF4E found in TFH cells selectively program the translation of TFH cell specification mRNAs as shown in Fig. 2, play an important role in promoting pathogenesis of EAE disease, and can be therapeutically targeted to block CNS immune infiltration and resulting demyelination.

Fig. 7. Inhibition of demyelination and CNS ELF formation in EAE disease by moderate inhibition of eIF4E.

(A) Representative images of Luxol fast blue (LFB)–stained spinal cords from animals with EAE induced as in Fig. 6, treated with vehicle or 4EGI-1. Myelin-stained blue. Scale bar, 500 μm. (B) Quantified spinal cord white matter myelination levels in control (no EAE) and EAE animals treated with vehicle or 4EGI-1. (C to E) Staining of spinal cords from control and EAE mice CD4+ T cells (red) and CD19+ B cells (green) and enlargement of ELFs treated with (C) vehicle, (D) 4EGI-1, or (E) control animals with no EAE. In histogram, dotted line represents levels in control animals with no EAE. **P < 0.01 ± SEM by two-tailed unpaired t test from three or more independent studies.

Down-regulation of eIF4E activity blocks TH17-dependent ELF formation in the CNS

In a model of passive EAE, TH17-differentiated myelin-specific CD4+ T cells migrate to the spinal cord and form TFH-like cells that contribute to ELF formation (35). We therefore used this system to determine whether high levels of eIF4E act in a TFH cell–intrinsic manner to promote pathogenesis. We first used 4EGI-1 to down-regulate eIF4E activity in OT2 T cells before adoptive transfer into congenic animals. Isolated OT2 T cells pretreated with vehicle or 4EGI-1 were adoptively transferred to OVA/alum-immunized (Fig. 8A) or nonimmunized (Fig. 8B) CD45.1 mice and followed for 3 or 34 days. OT2 T cells, whether treated with 4EGI-1 or vehicle, populated the spleen at equal levels when assayed at 3 and 34 days after transfer (Fig. 8, C and D). In contrast, 4EGI-1–treated OT2 TFH cells in the spleen of immunized mice decreased by 65% at 3 days after transfer (Fig. 8E), and when OT2 T cells were recovered as late as day 34 after transfer, they showed sustained reduction in intracellular levels of eIF4E (Fig. 8F). It was unexpected that ex vivo 4EGI-1 inhibition in OT2 T cells resulted in sustained down-regulation of eIF4E levels. While future studies will explore this mechanism in depth, we suspect that inhibition of eIF4E before adoptive transfer blocks feed-forward induction of eIF4E so that the cells never regain the ability to up-regulate it.

Fig. 8. 4EGI-1 pretreatment of TH17-differentiated 2D2 lymphocytes inhibits TFH-like cell development and protects against EAE disease.

(A) Adoptive transfer of activated OT2 T cells pretreated with vehicle or 20 μM 4EGI-1 for 1 hour, transferred into CD45.1 congenic host mice immunized with OVA/alum 4 days prior, and analyzed after 3 days. (B) Adoptive transfer of activated OT2 T cells pretreated with vehicle or 20 μM 4EGI-1 for 1 hour, transferred into nonimmunized CD45.1 congenic host mice, and analyzed after 34 days. (C) Spleen OT2 T cells pretreated 3 days after adoptive transfer. (D) Spleen OT2 T cells 34 days after adoptive transfer. (E) Vehicle- or 4EGI-1–pretreated spleen OT2 TFH cells in spleen at 3 days after transfer. (F) Spleen OT2 T cell eIF4E levels determined by flow cytometry 34 days after transfer. (G) Treatment of TH17-differentiated 2D2 cells with vehicle or 20 μM 4EGI-1 in culture, transfer into congenic mice for induction of passive EAE. (H) Daily clinical score of EAE mice with adoptively transferred pretreated differentiated 2D2 cells. (I) Quantification of TFH-like (ICOShigh) 2D2 T cells in spinal cords of EAE mice at day 34. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 ± SEM. Comparison of three or more groups was performed by a one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis; data from only two groups were analyzed by a two-tailed unpaired t test. Data shown are pooled from three or more independent studies.

Next, we treated TH17-differentiated 2D2 T cells with vehicle or 4EGI-1 in short-term culture before transfer into congenic animals to induce passive EAE (Fig. 8G). TH17-differentiated 2D2 cells infiltrate the CNS and become myelin-specific TFH cells, while also promoting development of endogenous TFH cells by host CD4+ T cells, which together contribute to EAE (17). While vehicle-treated TH17-differentiated 2D2 T cells induced EAE, mice receiving 2D2 T cells pretreated with 4EGI-1 did not develop disease (Fig. 8H). Furthermore, levels of TFH-like 2D2 T cells (characterized as ICOShigh) in the spinal cord of mice after treatment with 4EGI-1 were reduced by half (Fig. 8I). As also found for OT2 T cells, we suspect that partial down-regulation of eIF4E activity before adoptive transfer likely impairs the physiological induction of higher levels of eIF4E following adoptive transfer when 2D2 T cells typically undergo development to TFH cells, so that they never regain the ability to up-regulate eIF4E. Because acquisition of a TFH-like phenotype by 2D2 T is directly involved in EAE pathogenesis (17), these data demonstrate that high levels of CD4+ T cell eIF4E are essential to program selective translation that drives TH17-dependent development of TFH-like cells in the CNS during EAE.

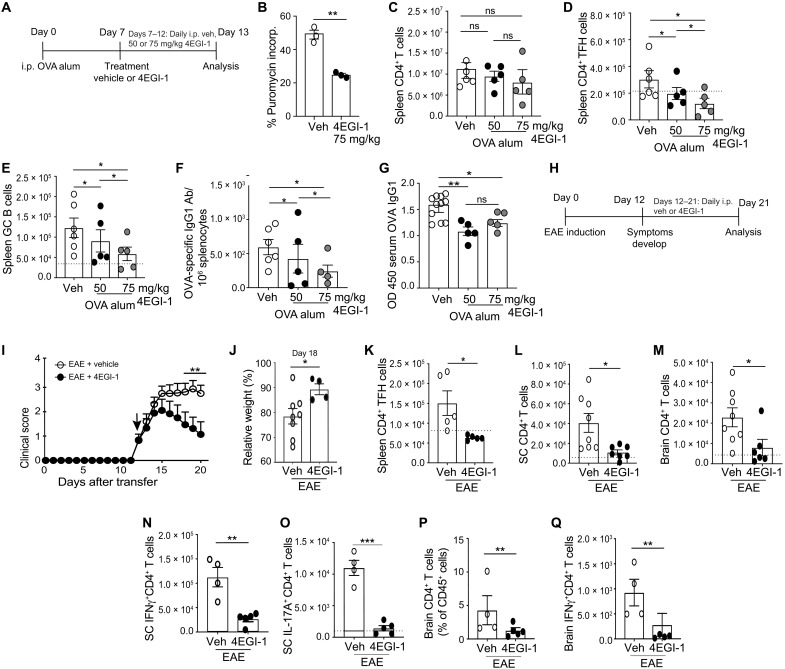

Strongly reduced eIF4E activity impairs TFH cell lineage commitment, inducing rapid remission and remyelination after development of EAE disease

We next determined whether more strongly reducing eIF4E activity can reverse and not just block TFH cell differentiation, thereby halting the progression of EAE disease. Mice were immunized with OVA/alum to induce TFH cells and then, following their development, treated with two and three times the dose of 4EGI-1 as used earlier, to test the effect of stronger reduction in eIF4E-dependent mRNA translation on TFH cell lineage commitment and pathogenesis (Fig. 9A). At 25 mg/kg (~25% inhibition of protein synthesis), there was still a substantial background of existing TFH cells, suggesting an inability to reverse previously established TFH cells. We therefore increased 4EGI-1 to 50 and 75 mg/kg, which is still within its safety range (19). At 75 mg/kg, 4EGI-1 reduced CD4+ T cell protein synthesis up to ~55%, twice that of 25 mg/kg used earlier (Fig. 9B), without significantly reducing the total number of splenic CD4+ T cells (Fig. 9C). In contrast, 4EGI-1 treatment (75 mg/kg) did reduce by threefold levels of preexisting splenic CD4+ TFH cells, GC B cells, and OVA-specific IgG1 ASCs and moderately reduced serum OVA-specific IgG1 antibody (Fig. 9, D to G). We therefore used the 75 mg/kg dose of 4EGI-1 to assess effects of eIF4E down-regulation on progression of EAE.

Fig. 9. Strong down-regulation of eIF4E activity inhibits progression of EAE and TH17-dependent ELF formation in passive EAE.

(A) Mice immunized with OVA/alum, treated at day 7 with 4EGI-1 (50 or 75 mg/kg) for 6 days. (B) CD4+ T cell protein synthesis rates treated with 4EGI-1 (75 mg/kg), determined by SUnSET assay. (C to G) Quantification of splenic (C) CD4+ T cells, (D) TFH cells, (E) GC B cells, (F) OVA-specific IgG1+ ASCs, and (G) serum OVA-specific IgG1. (H) Active EAE induction and treatment with vehicle or 4EGI-1 (75 mg/kg) following clinical symptoms. (I) Daily clinical scores of mice. Arrow, initiation of treatment. (J) Relative weight of mice. (K) Spleen CD4+ TFH cell levels at day 21, active EAE disease. (L and M) CD4+ T cell levels in (L) spinal cord and (M) brain at 21 days after EAE. (N and O) Spinal cord CD4+ T cell levels at 21 days during EAE disease, expression of (N) IFN-γ or (O) IL-17A. (P and Q) Brain CD4+ T cell levels expressing (P) IFN-γ or (Q) IL17A. Dotted line, control mouse levels. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 ± SEM. Comparison of three or more groups was performed by a one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis, and data from only two groups were analyzed by a two-tailed unpaired t test from three or more independent studies.

Twelve days following induction of EAE with MOG33–55/FCA injections, mice began to show symptoms and were treated with vehicle or 4EGI-1 (75 mg/kg; Fig. 9, H and I). Within 2 to 3 days of 4EGI-1 administration, mice exhibited marked improvement in clinical symptoms and reduced progression of disease and entered remission by day 15, compared to vehicle-treated mice that progressed. 4EGI-1–treated mice also lost less body weight compared to vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 9J). Reduced EAE disease was associated with threefold decreased levels of splenic TFH cells (Fig. 9K) and fourfold decreased infiltration and retention of CD4+ T cells in spinal cord and brain (Fig. 9, L and M), including those producing IFN-γ or IL-17A (Fig. 9, N to Q). Demyelination in mice treated with 4EGI-1 was reduced compared to vehicle-treated mice, even after initiation of symptoms, and previously demyelinated areas regained myelination to within 90% of normal levels (Fig. 10, A and B). Cessation of disease pathogenesis was associated with marked reduction in spinal cord immune cell infiltration (Fig. 10, C and D). While untreated control mice with EAE disease displayed multiple ELFs in their spinal cords, those treated with 4EGI-1 following onset of symptoms at day 12 had smaller clusters of CD4+ T cells and with a lower frequency of associated B cells (Fig. 10, E to G). Thus, reducing the high level of eIF4E translation activity in TFH cells by half after onset of disease is sufficient to block TFH cell differentiation and retention of pathogenic CNS T cells, induce rapid remission from EAE, and promote spinal cord remyelination.

Fig. 10. Down-regulation of eIF4E activity promotes remyelination after onset of active EAE and ELF formation in spinal cord.

(A) Representative images from control animals (no EAE) and at day 21 from animals with active EAE, treated with vehicle or 4EGI-1 as in Fig. 9H. LFB-stained spinal cords, myelin-stained blue. (B) Quantified spinal cord white matter myelination. (C) Representative H&E-stained cross sections of spinal cords from animals as in (A). Clusters of blue nuclei identify cell infiltration. (D) Quantification of infiltration of cells into spinal cord. (E to G) Staining of spinal cords for CD4+ T cells (red), CD19+ B cells (green), and enlargement of ELFs or CD4+ T cell clusters from mice with EAE that were treated with (E) vehicle, (F) 4EGI-1, or (G) control animals not subject to EAE. Scale bar, 500 μm. Dotted lines represent levels present in mice not subjected to EAE. **P < 0.01 ± SEM by two-tailed unpaired t test from three or more independent studies.

DISCUSSION

This study contributes to an emerging understanding of translational control of T cell and TFH cell differentiation, function, and participation in autoimmune disease. Using an inhibitor of eIF4E activity that is well tolerated, we show that TFH cells have intrinsically high levels of eIF4E in TFH cells compared to non-TFH CD4+ T cells, which are essential for lineage determination and commitment of TFH cells and GC B cells induced during immunization, infection, and allergy. The major impact of partial eIF4E inhibition is in uncommitted CD4+ T cells, which blocks their induction of high levels of eIF4E and prevents TFH cell development. If B cells were the primary target of inhibition by reduced eIF4E activity, there would not be an effect on TFH cells, whereas GC B cells are deficient without TFH cells. While there were no observable perturbations in TH1, TH17, TH2, or Treg cell levels or functions in the different immune cell induction model systems with moderate eIF4E inhibition, we cannot exclude the possibility that in more complex immune responses and in humans, there will not be an impact on the other TH cell subtypes, although TFH cells are the primary target.

Translatome analysis from control and 4EGI-1–treated OVA/alum-immunized mice reveal that the selective defect in TFH cells with moderate down-regulation of eIF4E activity and protein synthesis (~25%) is a result of reduced translation and transcription of largely TFH cell lineage determination and function mRNAs. These mRNAs include, among others, Pou2af1 and CD28, which promote Bcl6 expression (7, 36), and Bcl6 and CXCR5, which program key TFH cell functions, including CD4+ T cell migration into follicles and maintenance of follicles. Most of the TFH cell mRNAs that are dependent on high levels of eIF4E for their translation are downstream of TCR signaling. TCR signaling promotes early TFH cell fate–determining events, such as nuclear localization of NFAT and FoxO expression, which are upstream of BCL6 expression (37, 38). This is important because pharmacologically down-regulating the high levels of eIF4E activity that are essential to initiate TFH cell differentiation blocks their development and therefore acts downstream of TCR signaling pathways common to other TH cell subsets, providing TFH cell specificity. Certain transcription factor mRNAs are preferentially inhibited in translation by blocking induction of the high level of eIF4E activity in CD4+ T cells, which likely accounts for the reduced levels of mRNAs for certain TFH cell factors. These mRNAs are primarily involved in expression of Bcl6 and CXCR5. In addition, expression of receptors that are essential for TFH maintenance in GCs, such as PD-1 and SLAM, require high levels of eIF4E activity for translation of their mRNAs and are remarkably sensitive to inhibition by moderate reduction in eIF4E levels or activity. Increased eIF4E levels and activity are therefore a critical set point for TFH cell development and lineage maintenance that affects the multistage, multifactorial process of CD4+ T cell differentiation to TFH cells by modulating transcription and translation of key mRNAs.

Our investigation into the requirement for high levels of eIF4E in TFH cell differentiation extends several previous studies. For instance, BCL6-controlled regulatory networks identified calcium signaling, cytokine receptor expression, adherence junction, and ECM receptor interaction as important functional categories for expression linked to TFH cell differentiation (14). We demonstrated that these pathways are selectively programmed for translation of their encoding mRNAs by high levels of eIF4E in TFH cells and are acutely sensitive to moderate reduction in eIF4E activity. In addition, depletion of BCL6 in CD4+ T cells only impairs development of TFH cells and not other TH cell subsets (39), consistent with loss of BCL6 protein by down-regulation of the intrinsically high levels of TFH cell eIF4E activity, which also includes CXCR5, Slamf1, CD28, Nfat1/2, and other TFH cell determination factor mRNAs.

While most mRNAs require eIF4E for their translation, including that encoding BCL6 (40), we found that the selective translation of most TFH cell specification mRNAs are exquisitely sensitive to and require high levels of eIF4E. We do not yet have a mechanistic understanding for the increased requirement for eIF4E in translation of TFH cell differentiation mRNAs. Typically, strong 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) secondary structures can increase the requirement for eIF4E, although our computational analysis of TFH cell differentiation mRNA 5′UTRs does not indicate unusually strong RNA 5′ structure. However, there are a number of other mechanisms that can increase the requirement for eIF4E and that remain to be explored. Potential structural impediments to mRNA translation initiation can occur through specific motifs, or sequence-specific binding of RNA binding proteins (41), and by structurally stabilizing elements such as G-quadruplexes and pseudoknots among others, which are not computationally easily predicted with certainty, and remain to be characterized in future studies. Nevertheless, therapeutic use of eIF4E inhibitors could synergistically block both formation of TFH cells and progressive class switching by GC B cells. In this regard, there are numerous examples of small-molecule and antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) inhibition of eIF4E in the antitumor preclinical applications and in early-phase human cancer clinical trials using eIF4E ASOs [e.g., (42, 43, 44)]. In these studies, eIF4E activity was generally inhibited to higher levels to impair tumor growth and metastasis than in our low-dose 4EGI-1 studies and was well tolerated and moderately efficacious. Those studies, combined with our findings here, suggest that eIF4E inhibition is an attractive target in both the cancer and autoimmune disease settings.

TFH cells are associated with MS and EAE disease pathogenesis, although much remains to be understood. Investigation of the role of TFH cells in EAE has been confounded by many factors, including the lack of a TFH-specific inhibitor, TH cell plasticity, and use of different animal models to induce EAE (active versus passive). Although BCL6 inhibitors are sometimes used to block and assess the role of TFH cells, they impair other TH cell subtypes that express low levels of BCL6 during activation (45). Moreover, the high levels of BCL6 in TFH cells requires high concentrations of inhibitor to be effective, which introduces notable toxicity. Use of an eIF4E inhibitor is more feasible, as low levels of eIF4E inhibition dramatically reduce the ability of CD4+ T cells to commit to TFH cell development, by inhibiting translation of key TFH cell differentiation mRNAs including BCL6, without affecting differentiation and function of other TH cell types based on our animal model studies.

It was important in our study to assess the contribution of eIF4E to TFH cell function in both active and passive models of EAE. In active EAE, where mice are immunized with MOG/FCA, TFH cells were found in increased frequencies in secondary lymphoid organs, such as spleen and LNs, and within ELFs in the CNS (5, 17). However, in the absence of a specific TFH cell inhibitor, it was previously not possible to establish whether the contribution of TFH cells to disease is correlative or causative. In recent studies, Bcl6fl/fl × CD4cre mice were used to demonstrate that TFH cells contribute to clinical score in active EAE, although the effects on T cell infiltration into the CNS, demyelination, and ELFs due to loss of TFH cells were not explored (5, 17). Our study demonstrates that down-regulation of eIF4E-dependent mRNA translation, whether initiating at induction of EAE or subsequent to disease onset, results not only in significantly improved clinical score but also in reduced infiltration of CD4+ T cells into the CNS, including TH1 and TH17 cells, which inhibited formation of ELFs in the spinal cord and blocked demyelination. Stronger pharmacologic reduction of eIF4E activity, resulting in ~50% reduction in protein synthesis, following onset of EAE symptoms also rapidly induced remission and, quite remarkably, resulted in notable remyelination of the spinal cord and was well tolerated. Thus, in active EAE, TFH cells substantially contribute to clinical disease, establishment of CNS ELFs, recruitment and maintenance of pathogenic T cells in the CNS, and spinal cord demyelination.

In passive EAE, where only MOG-specific T cells are transferred to induce EAE, TFH cells appear to play several roles. First, transferred MOG-specific TFH cells on their own do not induce EAE. Instead, donor MOG-specific TH17 cells differentiate into TFH-like cells and promote the differentiation of host TFH-like cells in the CNS, where ELFs are induced. Both host and transferred TFH cells likely contribute to continued TH17-dependent disease pathogenesis, as indicated by reduction in disease severity with anti-CXCL13 treatment, a ligand for CXCR5 (5, 35). To complement these studies, we confined eIF4E deficiency to the TH17-differentiated 2D2 T cell compartment and asked whether higher levels of eIF4E contribute to TFH-like differentiation from TH17 cells in the CNS. 4EGI-1–pretreated TH17 cells failed to induce EAE and form TFH cells, which further demonstrates that the level and activity of eIF4E govern TFH cell differentiation.

Study limitations

Our work highlights the relevance of selective mRNA translational regulation in the development and function of TFH cells and their role in autoimmune pathogenesis. A limitation of this study is that many murine models of autoimmune diseases involve acute induction of autoimmune pathogenesis and therefore may not be sufficiently predictive of treatment response in humans, where autoimmune disease progresses slowly, chronically, and with greater immune complexity. While the results of eIF4E partial inhibition as a therapeutic intervention are notable in mice using an EAE model, in human MS and other autoimmune diseases that involve TFH cells, including SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, and type 1 diabetes, it cannot be definitely known from this work whether pharmacologic down-regulation of eIF4E activity will prove to be efficacious and restricted to the TFH cell compartment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statements

All studies involving cells and animals were conducted in a biosafety level 2 (BSL2) or 3 laboratory as appropriate. Experiments using recombinant DNA and viruses were approved by the New York University (NYU) Langone Health Institutional Biosafety Committee. Animal studies were approved by the NYU Langone Health Animal Institutional Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and approved under IACUC protocol IA16-00660. Animal studies were carried out in BSL3 animal facilities. Humane end points for EAE studies were predefined by IACUC protocols. Deidentified discarded human nonmalignant reactive LNs from surgical resection were obtained under NYU Langone Health Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocol IRB i13-00523.

Study design

Non-autoimmune studies: Experiments were performed with 5 to 10 mice per group, and end points were predetermined from previously published studies or expected drug efficacy ranges. Autoimmune studies: Experiments were performed with 10 to 20 mice per group.

Animals

C57BL/6 CD45.2, CD45.1 (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ), OT2 (B6.Cg-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/J) (46), 2D2 (C57BL/6-Tg(Tcra2D2,Tcrb2D2)1Kuch/J) (47), and IL-21 vivid VFP (B6.Cg-Il21tm1.1Hm/DcrJ) (48), along with BALB/c IL44get (C.129-Il4tm1Lky/J) (49) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and maintained under specific pathogen–free conditions using animal protocols approved by the NYU Langone IACUC.

Identification of mouse cell subsets by flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were stained with a viability marker diluted 1:1000 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min, washed in PBS, and stained with antibodies to specific cell surface markers. Viability dye, antibody clones, and dilutions used to identify these populations are detailed in dataset S3. Identification of cellular subsets in mice is detailed in figs. S1, S2, and S4. In brief, the following gating strategy was used to identify mouse TFH cells: (CD4+ PD1+ CXCR5+), TFR cells (CD4+ PD1+ CXCR5+ Foxp3+), IL-21+ CD4+ T cells (CD4+ VFP+), IL-4+ CD4+ T cells (CD4+ GFP+), OT2 T cells (CD4+ CD45.2+ Vβ5+), OT2 TFH cells (CD4+ CD45.2+ Vβ5+ PD1+ CXCR5+), 2D2 T cells (CD4+ CD45.2+ Vα3.2+), TFH-like 2D2 T cells (CD4+ CD45.2+ Vα5+ ICOShigh), plasma cells (B220− CD138+), plasmablasts (B220mid CD138+), GC B cells (B220+ GL7+ Fas+), light-zone GC B cells (B220+ GL7+ Fas+ CD86+), dark-zone GC B cells (B220+ GL7+ Fas+ CXCR4+), IgG1-switched GC B cells (B220+ GL7+ Fas+ IgG1+), OVA-specific GC B cells (B220+ GL7+ Fas+ OVA-647+), skin neutrophils (Ly6G+ CD11b+), lung eosinophils (SiglecF+CD11c−), and brain and spinal cord CD4+ T cells (CD45+ CD4+). CD4+ T cell expression of surface ICOS, PD-1, CXCR5, CD28, SLAM, OX-40, and intranuclear BCL6 was also determined. All flow cytometry procedures were performed on a ZE5 Cell Analyzer (Bio-Rad) and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

OVA alum immunizations and 4EGI-1 treatments

OVA protein (Sigma-Aldrich, A5503) was diluted in PBS and then in Imject alum (20 mg/ml; Thermo Fisher Scientific, 77161) and mixed at room temperature for 30 min before intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg of OVA in 200 μl. When stated, mice were treated intraperitoneally daily from days 0 to 6 or days 0 to 13 (just for TFR analysis) following OVA/alum immunization with 4EGI-1 (25 mg/kg; MedChemExpress) or from days 7 to 13 following OVA/alum immunization with 4EGI-1 (50 or 75 mg/kg). Vehicle control mice were administered 6 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide in 194 μl of PBS.

CD4+ T cell intranuclear stain

Single-cell suspensions of noted tissues were incubated with a live/dead viability marker and extracellular stain before fix and permeabilization with Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions to detect intranuclear transcription factors Foxp3, GATA-3, T-bet, RORγt, or BCL6. Concentration and clones of flow cytometry antibodies used for staining detailed in dataset S3.

Detection of intracellular eIF4E or eIF4GI levels by flow cytometry

Cells were incubated with a live/dead viability marker and extracellular stain before fix and permeabilization with a fixation/permeabilization solution kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions to detect intracellular eIF4E and eIF4G1. Concentration and clones of primary and secondary antibodies used for staining are detailed in dataset S3.

Western immunoblot

FACS-isolated T cells were lysed in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors, cleared by centrifugation at 20,000g 10 min at 4°C, and quantified by the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of protein were resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and probed by immunoblotting as described in (50). Clarity Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad) was used for detection. Primary and secondary antibodies used are detailed in dataset S3.

m7G-Sepharose cap chromatography

Isolated splenocyte CD4+ T cells were treated with vehicle or 25 μM 4EGI-1 for 4 hours, lysed [50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5% NP-40], and quantified as above. Protein extract (50 μg) was subjected to m7GTP-Sepharose cap chromatography (Jena Bioscience). m7GTP-Sepharose beads were washed in lysis buffer and incubated with bovine serum albumin (1 mg/ml; BSA) to block nonspecific binding for 30 min at 4°C. Beads were then washed and incubated with the protein extracts for 1 hour at 4°C. After centrifugation, flow-through was collected for analysis, and beads were washed in lysis buffer, added with 2× Laemmli buffer, boiled (100°C, 5 min), and vortexed. Beads were then centrifuged and supernatant (cap-bound proteins) collected. Input, cap-bound, and unretained flow-through proteins were identified by immunoblot analysis as detailed above. Primary and secondary antibodies used are detailed in dataset S3.

Cycloheximide treatment of mouse splenocytes for identification of short-lived proteins

Mice were immunized with 100 μg of OVA/alum, and 7 days following, spleens were harvested, and single-cell suspensions were generated. Splenocytes were incubated in mouse T cell media with cycloheximide (100 μg/ml) for 0, 1, 5, and 8 hours at 37°C. Cells were stained with a live/dead viability marker and then for extracellular expression of CD4, PD-1, or ICOS or intranuclear expression of BCL6.

In vitro treatment of mouse splenocytes with 4EGI-1 and surface sensing of translation (SUnSET) assay

Mice were immunized with 100 μg of OVA/alum, and 7 days following, spleens were harvested, and single-cell suspensions were generated. Splenocytes were incubated in mouse T cell medium (detailed in the “Silencing of eIF4E in OT2 T cells by lentivirus transduction” section) with 0 to 25 μM 4EGI-1 for 4 hours at 37°C. Cells were stained with a live/dead viability marker and then for extracellular expression of CD4, CXCR5, PD-1, or ICOS or intranuclear expression of BCL6. For the surface sensing of translation (SUnSET) assay, cells from above were incubated at 37°C with puromycin (10 μg/ml) for 10 min. Control samples were incubated with puromycin and cycloheximide (100 μg/ml). Cells were incubated with a live/dead viability marker and extracellular stain before fixation and permeabilization (BD Biosciences fixation/permeabilization solution) and intracellular staining with anti-puromycin followed by anti-mouse IgG2a antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488.

In vitro treatment of human LN cells with 4EGI-1

Discarded, deidentified, reactive, but nonmalignant human LN single-cell suspensions were obtained. Presence of TFH cells was confirmed by identification of CD4+ CD45RO+ T cells that are PD1+, CXCR5+, BCL6+, and ICOS+. LN suspensions were incubated overnight at 37°C in X-VIVO medium (Lonza) containing 5% human AB serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and GlutaMAX with 0 to 25 μM 4EGI-1. Cells were then stained with a live/dead viability marker and then for extracellular expression of human CD4, CD45RO, CXCR5, PD-1, or ICOS or intranuclear expression of BCL6. Expression of markers was normalized to percentage of control (0 μM 4EGI-1) to allow for combined statistical analysis of all three patients. Antibody clones and dilutions used to identify these populations are detailed in dataset S3.

Induction of active EAE, scoring, and 4EGI-1 dosing

Ten-week old female mice purchased from the Jackson Laboratory were subcutaneously injected at two sites with 100 μl of MOG33–55 emulsified in FCA (Hooke Labs) per flank. On the same day, 6 hours later, and on day 2, mice were injected with pertussis toxin [100 ng, intraperitoneally (ip)] in 200 μl. Mice were monitored daily and scored on a scale of 0 to 5 where 0, no disease; 1, tail paralysis; 2; hindlimb paresis; 3, complete hindlimb paralysis; 4, front limb weakness and hindlimb paralysis, and 5, moribund state. When stated, mice were either administered 4EGI-1 (25 mg/kg, ip) or vehicle from days 0 to 21 following EAE induction or 4EGI-1 (75 mg/kg, ip) or vehicle from days 12 to 21 following EAE induction and randomization.

Induction of passive EAE and pretreatment of 2D2 cells with 4EGI-1

CD4+ T cells were isolated from female 2D2 mice (>90% Vα3.2) and cultured under select TH17 conditions (20 ng/ml mouse IL-6, 20 ng/ml mouse IL-23, 20 ng/ml mouse IL-1β, 50 U/ml human IL-2, 10 μg/ml anti-mouse IL-4, and 10 μg/ml anti-mouse IFN-γ) on anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml)–coated plates for 3 days. TH17 2D2 T cells were removed from activation and treated with vehicle or 20 μM 4EGI-1 for 1 hour at 37°C in vitro before transfer of 9.3 × 106 2D2 T cells intraperitoneally per recipient. Mice were given pertussis toxin (200 ng, ip) 6 and 25 days following T cell injection. Animals were monitored daily for 35 days and scored on a scale of 0 to 5 as described above. At day 35, TFH-like (ICOShigh) Vα3.2 cells were identified from the spinal cord.

S. aureus growth and infection

S. aureus subspecies Rosenbach [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 25923] was grown overnight in tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Corning). Following quantification, 1 × 108 colony-forming units of S. aureus in 100 μl were injected subdermally in the base of the ear pinnae. On days 0 through 7, mice were treated daily with 4EGI-1 or vehicle (25 mg/kg, ip). On days 8, mice were euthanized, and the whole infected ear was collected along with the CLN and blood. Blood was allowed to clot at room temperature and spun at 2000g for 30 min, and serum was collected and frozen until analysis. Ear thickness was measured with a digital caliper on day 8.

A. fumigatus isolation and sensitization

A. fumigatus Fresenius (ATCC 13073) was grown for 7 days on potato dextrose agar plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C. Conidia were harvested by agitation in a flask with sterile PBS + 0.1% Tween 20 and filtered through a 40-μm nylon mesh. Mice were intratracheally sensitized with 1.8 × 106 conidia in 5 0 μl of PBS on days 0, 7, and 11. On days 0 through 17, mice were treated daily with 4EGI-1 or vehicle (25 mg/kg, ip). On day 18, mice were euthanized, and lungs were collected along with MedLN and blood. Serum was obtained and stored as described above.

Lentivirus production

Human embryonic kidney 293 T cells (ATCC catalog no. CRL3216) were transfected with pTRIPZ plasmid expressing NS shRNA (ACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAATT) or eIF4E shRNA (GCGTCAAGCAATCGAGATTTG) along with psPAX2 and pMD2.G in Lipofectamine 2000 and Opti-MEM. Supernatant was collected 48 hours later and centrifuged at 3000g for 15 min at room temperature. Cell debris pellet was discarded, and supernatant was incubated with PEG-it (System Biosciences) at 4°C for 24 to 48 hours and then centrifuged for 1500g for 30 min at 4°C. Supernatant was discarded, and viral pellet was resuspended in cold PBS and frozen at −80°C until use.

Silencing of eIF4E in OT2 T cells by lentivirus transduction

CD4+ T cells were isolated (EasySep CD4+ T cell isolation, StemCell) from OT2 mice (>95% Vβ5.1/5.2) using negative selection. OT2 T cells were activated in mouse T cell medium [RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), 25 mM Hepes, 100 μM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM GlutaMAX, nonessential amino acids, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml)] and soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml) with IL-2 (50 U/ml) on plates coated with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) for 3 days. Following activation, cells were spin-transfected at 3 × 106 cells in 1 ml in six-well plates with lentivirus and dextran (4 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, D9885) at 2000g for 60 min at 30°C with no acceleration or break (51). Following spinoculation, cells were centrifuged, and supernatant was decanted and replaced with fresh medium. The next day (day 5), puromycin (2 μg/ml; Gibco) and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)/ionomycin (BioLegend) are added to the T cells and incubated for 3 days. On day 8, medium was replaced, and cells were incubated with puromycin again for another 3 days. On day 10, it was confirmed that control cells not transfected with virus were >98% dead, and 1.5 × 106 OT2 NS or OT2 eIF4Esh were transferred intraperitoneally to CD45.1 mice. One day following adoptive transfer, mice were placed on Dox diet (200 mg/kg) and remained on this diet for the entire study. After 7 days on Dox diet (day 8 following transfer), mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 100 μg of OVA/alum, and 7 days following immunization (15 days following transfer), mice were euthanized for analysis of OT2 T cells.

Mouse tissue processing

Spleens, draining LNs, and brains were dissociated with the plunger end of a syringe and passed through a 70-μm nylon filter. Splenocytes were subject to red blood cell lysis with ACK (ammonium-chloride-potassium). Ears were subject to mechanical dissociation with scissors before incubation in 1 ml of PBS in a 48-well plate with Liberase TL (100 μg/ml) and deoxyribonuclease (DNase I, 20 μg/ml) for 1.5 hours at 37°C. Following incubation, cells were further dissociated by passing through a syringe, quenched with PBS plus 2% fetal calf serum (FCS), and filtered through a 70-μm nylon filter. Lungs were mechanically dissociated with a razor blade and incubated in a 6-cm dish with 5 ml of RPMI 1640 containing collagenase (250 μg/ml), Liberase TL (50 μg/ml), hyaluronidase (1 mg/ml), and DNase I (200 μg/ml) for 30 min. Following incubation, cells were quenched with PBS plus 2% FCS and filtered through a 70-μm nylon filter. Ear and lung cells were subject to lymphocyte isolation using a gradient (Lymphocyte Separation Medium, Cellgro). Vertebral columns were flushed with PBS through a 19-gauge needle to remove intact spinal cords. Spinal cords were subject to mechanical dissociation with scissors and incubation in 1 ml of PBS with DNase I (200 μg/ml) and Liberase TL (50 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. Following incubation, cells were quenched with PBS plus 2% FCS and filtered through a 70-μm nylon filter.

Mouse in vitro CD4+ T cell differentiation and cytokine production

Naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated (EasySep Naïve CD4+ T cell isolation, StemCell) and incubated in mouse T cell medium (described in the “Silencing of eIF4E in OT2 T cells by lentivirus transduction” section) containing soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml), cytokines, and anti-cytokine antibodies as detailed for polarization to TH1: mouse IL-12 (10 ng/ml), human IL-2 (50 U/ml), and anti-mouse IL-4 (10 μg/ml); TH2: mouse IL-4 (10 ng/ml), human IL-2 (50 U/ml), and anti-mouse IFN-γ (10 μg/ml); TH17: mouse IL-6 (20 ng/ml), mouse IL-23 (10 ng/ml), mouse IL-1β (10 ng/ml), human TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml), human IL-2 (50 U/ml), IL-4 (10 μg/ml), and anti-mouse IFN-γ (10 μg/ml); and Treg: mouse TGFβ (2 ng/ml) and human IL-2 (300 U/ml). TH1, TH2, and TH17 differentiation kits (Cytobox) along with human IL-2 were purchased from Miltenyi Biotec. Mouse TGFβ was purchased from BioLegend. Naïve CD4+ T cells in conditions described above were activated on anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml)–coated plates for 3 days. Following differentiation, 20 μM 4EGI-1 was added to T cell cultures for 48 hours. Supernatant was removed and cytokine levels were determined using LEGENDPlex Mouse Th Cytokine Panel (BioLegend).

Polysome profiling

Mice were treated with OVA/alum + vehicle or 4EGI-1 (25 mg/kg) as described. Following removal of spleens through CD4+ T cell isolation, tissue and cells remained in cycloheximide (0.1 mg/ml) until pelleted and flash-frozen. Cell pellets were lysed for 10 min on ice with 400 μl of polysome extraction buffer [15 mM tris-Cl (pH7.4), 15 mM MgCl2, 0.3 M NaCl, cycloheximide (0.1 mg/ml), 100 U of Superasin, and 1% Triton X-100]. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 13,200g for 10 min. Equal RNA concentrations were layered onto 20 to 50% sucrose gradients. Gradients were sedimented at 151,263g for 103 min in an SW55 Ti rotor at 4°C. An ISCO UA-6 (Teledyne) fraction collection system was used to collect 12 fractions, which were immediately mixed with 1 volume of 8 M guanidine HCl. RNA was precipitated from polysome fractions by ethanol precipitation and dissolved in 20 μl of H2O. Briefly, fractions were vortexed for 20 s, 600 μl of 100% ethanol was added, and fraction was vortexed again. Fractions were incubated overnight at −20°C to allow for complete RNA precipitation. Fractions were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. The RNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol. The pellet was resuspended in 400 μl of 1× tris-EDTA (pH 8.0). NaOAc (pH 5.3; 0.1 volumes of 3 M) and 2.5 volumes 100% ethanol were added, and fractions were incubated at −20°C to precipitate RNA. Fractions were centrifuged at 13,0000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. The RNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol. RNA was resuspended in 20 μl of H2O. Total RNA samples were isolated from cell lysates using TRIzol per the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA sequencing, data analysis, and data availability