Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) is a Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen that infects patients with cystic fibrosis, burn wounds, immunodeficiency, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), cancer, and severe infection requiring ventilation, such as COVID-19. P. aeruginosa is also a widely-used model bacterium for all biological areas. In addition to continued, intense efforts in understanding bacterial pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa including virulence factors (LPS, quorum sensing, two-component systems, 6 type secretion systems, outer membrane vesicles (OMVs), CRISPR-Cas and their regulation), rapid progress has been made in further studying host-pathogen interaction, particularly host immune networks involving autophagy, inflammasome, non-coding RNAs, cGAS, etc. Furthermore, numerous technologic advances, such as bioinformatics, metabolomics, scRNA-seq, nanoparticles, drug screening, and phage therapy, have been used to improve our understanding of P. aeruginosa pathogenesis and host defense. Nevertheless, much remains to be uncovered about interactions between P. aeruginosa and host immune responses, including mechanisms of drug resistance by known or unannotated bacterial virulence factors as well as mammalian cell signaling pathways. The widespread use of antibiotics and the slow development of effective antimicrobials present daunting challenges and necessitate new theoretical and practical platforms to screen and develop mechanism-tested novel drugs to treat intractable infections, especially those caused by multi-drug resistance strains. Benefited from has advancing in research tools and technology, dissecting this pathogen’s feature has entered into molecular and mechanistic details as well as dynamic and holistic views. Herein, we comprehensively review the progress and discuss the current status of P. aeruginosa biophysical traits, behaviors, virulence factors, invasive regulators, and host defense patterns against its infection, which point out new directions for future investigation and add to the design of novel and/or alternative therapeutics to combat this clinically significant pathogen.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Infection

Introduction to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a critical clinical pathogen and model microorganism

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a multi-drug resistance (MDR) opportunistic pathogens, causing acute or chronic infection in immunocompromised individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis, cancer, traumas, burns, sepsis, and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) including those caused by COVID-19.1–3 P. aeruginosa in biofilm states may survive in a hypoxic atmosphere or other extremely harsh environments.4,5 In addition, treatments of P. aeruginosa infection are extremely difficult due to its rapid mutations and adaptation to gain resistance to antibiotics.6 Furthermore, P. aeruginosa is also one of the top-listed pathogens causing hospital-acquired infections, which are widely found in medical devices (ventilation) because they tend to thrive on wet surfaces.7 Importantly, P. aeruginosa is one of the MDR ESKAPE pathogens, which stand for pathogens Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacter. P. aeruginosa with arbapenem-resistance is listed among the “critical” group of pathogens by WHO, which urgently need novel antibiotics in the clinics.8

Epidemiological studies have shown that nearly 700,000 people died of the antibiotic resistance bacterial infections each year. P. aeruginosa that was isolated from European populations with a combined resistance was 12.9%.9 Hospital-acquired infection caused by P. aeruginosa continues to produce resistance to conventionally effective antibiotics becoming a main healthcare problem.10 The 2016 EPINE survey found that Escherichia coli and P. aeruginosa are the most common cause of hospital-acquired infections in Spain, P. aeruginosa accounting for 10.5% of clinically isolated bacteria infections.11 The 2011–2012 HCAIs report that P. aeruginosa caused almost nosocomial 9% of infections, which is the fourth commonest pathogen of the European hospitals.12 Similarly, 7.1% of HCAI are caused by P. aeruginosa in the United States.13 In addition, the 2016 European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) epidemiological reported that P. aeruginosa causes a variety of ICU-hospital-acquired infections, including pneumonia flares, urinary tract infections, and bloodstream infections.9,10,14,15 Furthermore, data from China Antimicrobial Surveillance Network (CHINET) (http://www.chinets.com/) identified 301,917 clinically isolated pathogenic strains and found P. aeruginosa was the fourth nosocomial infections after Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus, accounting for 7.96%. Altogether, P. aeruginosa is not a local, but a global major threat to human health.

The aforementioned statistics necessitate the identification drug targets and development of new treatments and effective vaccines for P. aeruginosa to improve human health. However, both efforts have met huge difficulty due to the surging cases with MDR strains. This article broadly reviews the recent progress in P. aeruginosa research towards the regulatory and functional mechanisms of virulence factors, gene expression regulators, secretion systems, quorum sensing, and antibiotic resistance, as well as host-pathogen interaction, new technologic advances, and therapeutic development (Fig. 1).

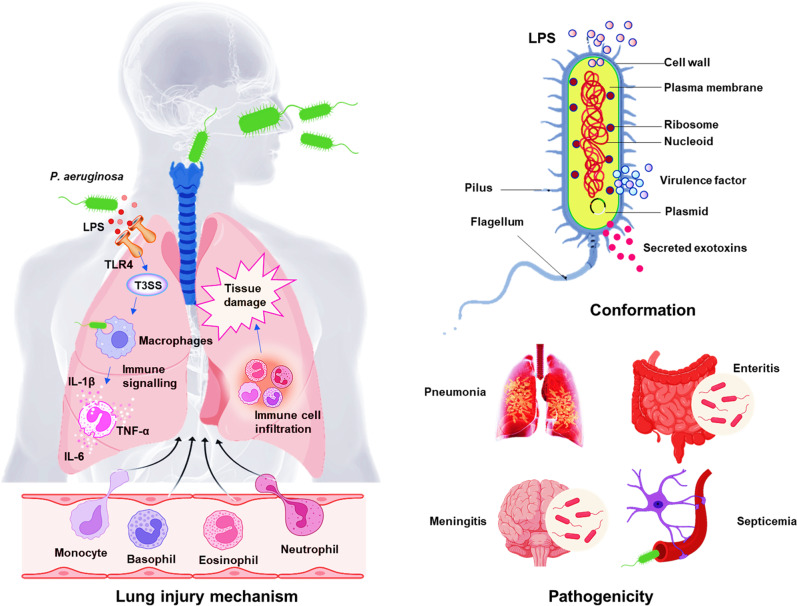

Fig. 1.

Schema of P. aeruginosa pathogenesis. P. aeruginosa can be traced everywhere including hospital environments and cause serious infection of almost any organ. LPS induces TLR-4-dependent and -independent inflammatory responses in the lung after bacterial infection, epithelial cells secrete cytokines and chemokines, thereby recruiting and activating innate immune cells and adaptive immune cells. The recruitment of neutrophils is a sign of inflammatory response activation. Although the activation of neutrophils is critical for host defense, excessively activated immune cell infiltration will cause severe tissue damage and aggravate bacterial infections.478 Therefore, studying the balance between the virulence factors secreted by bacteria and corresponding host immunity is important for the treatment of infections

Virulence factors

P. aeruginosa is able to adapt to the adverse environment in hosts by secreting a variety of virulence factors, which contribute to successful infection and causing disease.16 First, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is an important surface structural component to protect the external leaflet and posion host cells and the endotoxicity of the lipid A in LPS enable tissue damage, attachment, and recognition by host receptors.17 LPS may be related to antibiotic tolerance and biofilm formation.18 Second, out membrane proteins (OMPs) contributes to nutrient exchange, adhesion, and antibiotic resistance.19 In addition, drug resistance caused by the formation of biofilms is associated with the flagellum, pili, and other adhesins.20 Fourth, there are six types of secretion systems, including flagella (T6SS-associated), pili (T4SS), and multi-toxin components type 3 secretion system (T3SS), which function at colonisation of the host, adhesion, swimming, and swarming responding chemotactic signaling. Finally, exopolysaccharides, such as alginate, Psl and Pel, may help facilitate the formation of biofilms, while impairing bacterial clearance.20

In terms of toxins, T3SS is a complex system and may severely impede host defense via injection of cytotoxins including ExoU, ExoT, ExoS and ExoY, which affect the intracellular environment, especially blocking phagocytosis and bacterial clearance. Exotoxin A (ETA) can inhibit host protein synthesis through ADP ribosylation activity.21,22 Pyocyanin is also toxic to hosts to cause disease severity, damage host tissue, and impair organs’ function.23 In addition, LasA and LasB elastases, alkaline protease (AprA) LipC lipases, phospholipase C, and esterase A enzymes comprise a large group of lytic enzymes that modulate other virulence factors.24 Moreover, rhamnolipids-mediated lung surfactant degrading and tight junction destroying can directly injure trachea or lung epithelial cells.25 Furthermore, siderophores (pyoverdine and pyochelin) as iron uptake systems help in bacterial survival in iron-depleted environment to augment virulence strength.26 Finally, antioxidant enzymes, such as catalases (KatA, KatB, and KatE), alkyl hydroperoxide reductases, and superoxide dismutases, neutralize activity of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in phagocyte environments to avoid clearance.27

Virulence factors related to membranes

Lipopolysaccharide as a virulence factor widely interacting with hosts and also target for vaccines

LPS, an important classical structural component of the outer membrane (OM) of most Gram-negative bacteria, is a known potent agonist that elicits robust innate inflammatory immunity, its distal end may be capped with O antigen, a long polysaccharide that can range from a few to hundreds of sugars in length, which is critical for bacterial physiology and pathogenesis.28 At the early stage, scientists were interested in developing vaccines to prevent infection by focusing on LPS, which were later proven highly difficult due to the various serotypes and inefficacious outcomes.28–30

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), as small molecular motifs conserved in a class of microorganisms, can be sensed by toll-like receptors (TLRs) and other pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to activate innate immune responses, which effectively protect the host from infection.31 LPS, as the prototypical PAMP, can be recognized by multiple host receptors, including TLRs, PRRs, and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like (NOD-like) receptors.32 The LPS-PRRs/NOD-like molecules activate inflammasome to produce proinflammatory cytokines,33,34 activating TNF-α and IL-1β, two of the most eminent inflammatory cytokines.35 Furthermore, LPS amongst five major Gram-negative bacteria have the ability to induce the production of NF-κB and proinflammatory IL-8 in a TLR4-dependent manner, suggesting that the pathogenesis of bacterial enhancement of chronic inflammatory diseases may be related to its serotype-specific LPS response.36

Apparently, LPS exhibits a crucial role in regulating the interaction of bacteria with their host, is the main cause of tissue degeneration and chronic damage. LPS induces respiratory tract infections by regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-mediated airway remodeling.37 The mutations of LPS can result in attenuated virulence.38,39 Caffeine alleviates the excessive inflammatory response caused by P. aeruginosa infection by inhibiting the activation of LPS-mediated TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB/miR-301b signaling pathway, and improves lung tissue injury.40 Notably, LPS mutations confer bacteria gain tolerance to phage infection.41 Taken together, in addition to the direct interaction with the host PRRs receptors, LPS may use its unique molecular features to adjust bacterial pathogenesis and damage host immune defense, ultimately benefiting the fitness and invasive strength.

OMVs are important part of virulence platforms

OMVs are bacterial components that can be released spontaneously to the environment during growth by many Gram-negative bacteria. Bacterial-derived OMVs have been characterized as a novel secretion mechanism that can deliver a variety of bacterial proteins and lipids into host cells without direct contact with host cells.42–44 OMVs can package and enrich a wide variety of proteins and nucleic acids, including lipoproteins, periplasmic proteins (E. coli cytolysin A, enterotoxigenic E. coli heat-labile enterotoxin, and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin), plasmid containing chromosomal DNA fragments, phage DNA, virulence factors (LPS, alkaline phosphatase, phospholipase C, β-lactamase, and Cif et al.45,46 P. aeruginosa secretion of OMVs have been implicated in many virulence-associated behaviors, including the acquisition of drug resistance, the regulation of bacterial density and host immune escape.47–51 Mechanistically, P. aeruginosa secretes OMVs to deliver virulence factors and sRNAs into lung epithelial cells through the diffusion the mucus layer.44,47,52–55 Some studies also illustrate that OMVs could lead to an increased hydrophobicity of cell surface, resulting in enhanced ability to form biofilms.56 OMVs is controlled by quorum-sensing systems, which enable bacteria to colonize and immune escape.54,57 Interestingly, OMVs are naturally immunogenic and self-adjuvation, making them have potential to be developed as antibacterial vaccine, such as OMV vaccine for Neisseria meningitidis.58–60 Therefore, OMVs are not only an important functional constitute, but also a potential biotechnological engineering carrier for vaccination or drug delivery. More details about virulence factors and their associated treatment strategies in P. aeruginosa are listed in Table 1 (45, 82–100).

Table 1.

The major pathogenesis factors of P. aeruginosa and therapeutics

| Pathogenic factor | Features and biological role | Therapeutic intervention | Vaccine availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteases | P. aeruginosa secreted proteases include elastase A, elastase B, large protease, protease IV, alkaline protease, Pseudomonas small protease, MucD, and P. aeruginosa aminopeptidase. They exhibit high proteolytic enzyme activity that damages host tissues by degrading proteins. | Protease inhibitors | Preclinical369,392,408 |

| Toxins | P. aeruginosa produces a variety of extracellular toxins, including pigments, phytotoxic factors, hydrocyanic acid, phospholipase, protein convertase, enterotoxin, exotoxin, and mucus. These exotoxins can cause leukopenia, acidosis, liver necrosis, pulmonary edema, circulatory failure, renal tubular necrosis and bleeding, and many other serious damages. | Bacteriophages | Preclinical410,415,436 |

| LPS | LPS is an integral component of cell envelope. It is the major virulence factor of P. aeruginosa and can be recognized by host pattern-recognition receptors to initiate inflammation and immunity response. | Antibody | Phase III380,389,425 |

| Pili and fimbriae | Pili and fimbriae are the major adherence factors. They contribute to the adherence and motility of P. aeruginosa in host. | Phages380,422,424 | None |

| Flagella | The main protein component of flagella is flagellin. Flagella provide motility and chemotaxis toward specific substrates and provide the ligand for clearance by phagocytic cells. | Bacteriophages | Phase III366,393,410 |

| Leukocidin (cytotoxin) | They are secreted by the typical secretion system (e.g., ExoU secreted by Type III secretion system) and are the main cytotoxin targeting lymphocytes and neutrophils. | Natriuretic peptides376,380 | None |

| Siderophores | There are two siderophores produced by P. aeruginosa: pyoverdine (formerly called fluorescein) and pyochelin. In addition to the iron needs, siderophores can support other virulence factors production by transferring iron, such as biofilms and toxic themselves. | Antibiotic-siderophore387 | None |

| Urease | Urease enzyme is a virulence factor (limited extent) of P. aeruginosa. It can hydrolyze urea to produce ammonia and carbon dioxide (CO2). It is associated with urinary tract infection.378,427 | None | None |

| Outer membrane proteins | The outer membrane contains a large number of outer membrane proteins. These protein members are involved in the transportation of amino acids and peptides, the absorption of antibiotics, and the transportation of carbon sources. They are essential for bacterial adherence, virulence secretion, and host recognition. | Potential receptor for the internalization of host | Phase I372,456,457 |

Secretion systems, an integral part of virulence platforms and mechanisms

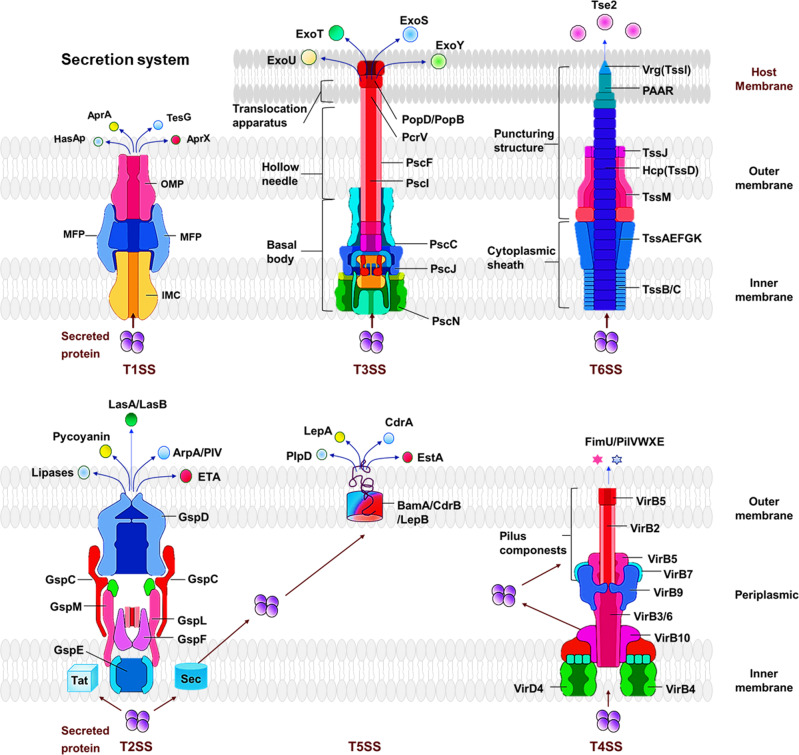

Gram-negative pathogens cause various types of nosocomial infections, and secreted virulence factors often mediate their interactions with the host.61 Bacteria can modulate the host immune response through the secretion system for secreting virulence factors into host cells, which facilitates immune escape and enable bacterial colonization.62 Currently, 6 types of secretion systems (T1SS to T6SS) have been identified in P. aeruginosa. Based on the secretion routes of transport proteins, the secretion systems are divided into two major classes, one-step secretion system (T1SS, T3SS, T4SS, and T6SS) and two-step secretion system (T2SS and T5SS). The one-step secretion system directly secretes proteins from bacterial cytosol to the surface, while the two-step secretion system requires a brief periplasmic stay of the secreted proteins on the export way and then releases the proteins to outside environments of the bacterium (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Protein secretion systems in P. aeruginosa. The secretion systems are divided into two major classes, one-step secretion system (T1SS, T3SS, T6SS) and two-step secretion system (T2SS, T5SS). One-step secretion system exoproteins are directly absorbed into the cytoplasm through their cognate secretion mechanism. In contrast, the exoproteins of two-step secretion system are first exported to the periplasm through the Sec or Tat system, and then crossing outer membranes through specific secretion mechanisms

One-step secretion systems

T1SS

Two different T1SS types in P. aeruginosa elucidated, Apr secretion system and Has secretion system.63 The Apr secretion system consists of three major components: AprD (ATP-binding cassette transporter, ABC transporter), AprE (adaptor), AprF (outer membrane factor, OMF), and secretes two proteins: AprA (alkaline protease), and AprX (protein with unknown function).64 T1SS is found in a variety of bacteria (P. aeruginosa Salmonella enterica, Neisseria meningitidis, and E. coli).65 T1SS major transport proteins (such as proteases and lipases). The substrate protein containing a C-terminal uncleaved secretion signal were recognized by the ABC transporter, were directly transferred across bacterial inner and outer membranes in a one-step process.66 The Has secretion system is composed of HasD (ABC transporter), HasE (adaptor), HasF, and OMF.67 Has secretion system participates in iron regulation by secreting an extracellular haem-binding protein (hasAp).68 Thus far, data relating to T1SS is very limited and its function in pathogenesis and significance for bacterium physiology and fitness are largely unknown, requiring further elucidation in order to know whether it has potential important functions.

T3SS

The T3SS of P. aeruginosa, playing a key role in virulence like quorum sensing, was first discovered in 199669 and is one of the most extensively-studied secreted toxins with increasing evidence for its important virulent effects.70 The T3SS regulon comprises five distinct operons, including the pscN to pscU, the exsD-pscB to pscL operons, the popN-pcr1-pcr2-pcr3-pcr4-pcrD-pcrR operon, the pcrGVH-popBD operon and finally the exsCEBA operon.71,72 The five distinct operons play important roles in the biogenesis and translocation mechanisms of type III secretions. Structurally, the T3SS, similar to a molecular syringe, comprises five components: the needle complex, the translocation apparatus, the regulatory proteins, the effector proteins, and the chaperones.73 T3SS secretes virulence effectors (ExoS, ExoT, ExoY, and ExoU) into the eukaryotic host cells to disrupt intracellular signaling and ultimately causing cell death.74–76 Many bacterial factors regulate T3SS genes of P. aeruginosa. The MgtC and OprF of PAO1 regulate T3SS and ExoS-induced host macrophage damage.77 The T3SS is positively regulated by PsrA,78 HigB,79 Vfr,80 and DeaD,81 but negatively regulated by MexT,82 AlgZR, GacAS/LadS/RetS,83–88 and MgtE.89 No only for P. aeruginosa, the T3SS is a highly important secretion mechanism for Gram-negative bacterial invasion factors, which may also facilitate the bacterial evasion from the host immune responses to establish invasion, colonization, replication, and spread.

T6SS is a novel, important virulence machinery

In P. aeruginosa, T6SS is a newly identified powerful system with diverse and vital functions in virulence, bacterial interaction, and competition with the environmental microorganisms.90 Initially, the genome of P. aeruginosa was thought to constitute three gene clusters called Hcp Secretion Island (HSI) encoding T6SS components, which are later renamed H1-T6SS to H3-T6SS,91,92 with ~15–20 genes for each of them.93 In addition, the apparatus of T6SS, consisting of 13 core components, is divided into a baseplate-like structure, a sheathed inner tube assembled from the baseplate-like structure and a trans-membrane complex.94 The assembled T6SS appears to be an inverted phage tail, with the Hcp (hemolysin coregulated protein)/Vgr (valine-glycine repeat protein) complex forming the distal end of the cell-puncturing device.95 The sheath transits the effectors into targeted cells by a contraction-based mechanism.96 Furthermore, ClpV, an AAA+ family ATPase of T6SS, also provides the energy necessary to drive the secretory apparatus.97

Mechanically, the secretion process by T6SS needs other elements; for example, the H2-T6SS machinery to deliver the novel antibacterial toxin Tle3 requiring a cytoplasmic adaptor Tla3.98 The GacAS/Rsm regulates T6SS (H1-T6SS and H3-T6SS) by activating RsmY/Z to inhibit the binding activity of RsmA/RsmN to fha1/tssA1.99 H3-T6SS secrete TseF to facilitate the import of the PQS-Fe3+ complex into cells by incorporating it into OMVs with Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS).100 Interestingly, it was found that the quorum sensing (QS) system plays an important role in the expression of this secretion system. In P. aeruginosa, QS differentially regulates three loci of encoding T6SS (HSI-I, HSI-II, and HSI-III) by LasR and MvfR.101 The QS systems regulator of Las and Rhl controlls the expression of H2-T6SS in PAO1 strains102 and the QS regulator of MvfR directly modulates the expression of multiple proteins, including virulence factors and other regulators in PA14,103 respectively.

The H1-T6SS-dependent substrates have a broad research foundation, while only little is known about functional roles of H2-T6SSs and H3-T6SSs due to the limited substrates available for research.104 With collaboration efforts, we characterize H2-T6SS-dependent secretomes that are related to copper (Cu2+)-binding effector azurin (Azu).104 Azu and H2-T6SS are both inhibited by CueR while induced by low levels of Cu2+. Furthermore, our studies reveal an Azu-interacting partner OprC, which is a Cu2+-specific TonB-dependent outer membrane transporter and is also modulated by CueR. The Azu-OprC-mediated Cu2+ transport network may contribute to P. aeruginosa virulence. Our follow-up studies indeed illuminate that oprC dampens host response in cells and mice to Pseudomonas infection by potently enhancing Quorum-Sensing-associated virulence.105

In addition, we recently describe a function for H2-T6SS of P. aeruginosa for specific delivery of AmpDh3 (a paralogous zinc protease) to the periplasm of a prey bacterium upon contact.106 AmpDh3 can hydrolyze peptidoglycan located on the cell wall of the prey bacterium to induce prey cell death, which serves as evolutionary advantage for P. aeruginosa in a competitive environment.

In spite of the relative short time since discovery of T6SS, the progress in understanding the potent virulence pathway is fascinating and fast-moving, which may define many unknown functions that can be attributed to T6SS’ virulence and indicate new ways for treating patients who suffer the most severe disease and difficult to treat.107

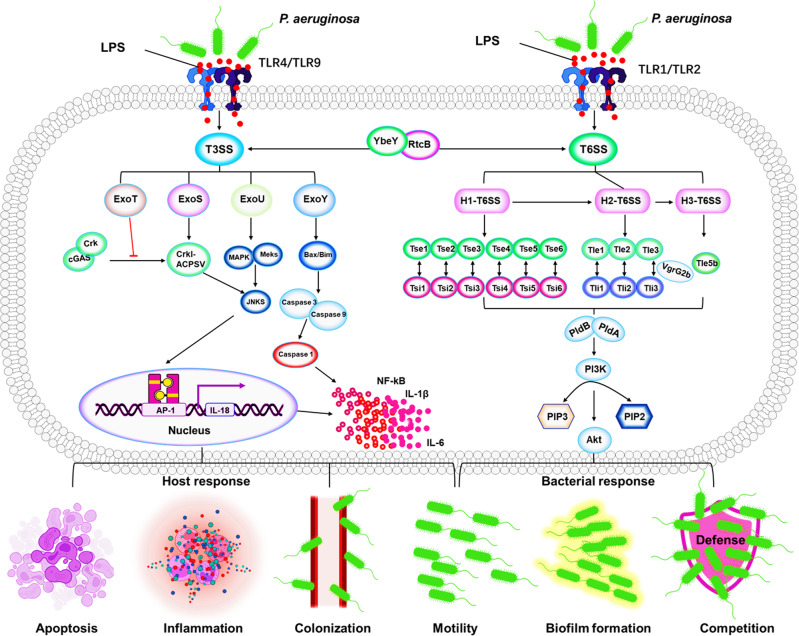

T3SS and T6SS in cooperation for regulating host and bacterial responses

T3SS and T6SS are indicated to regulate host and bacterial responses, including host cell apoptosis, inflammatory response, colonization, motility, biofilm formation, and bacterial competition/interaction108,109 (Fig. 3). Interaction regulation and inter-conversion of T6SS and T3SS may be especially helpful for coping with complex environmental pressures.110 The switch between T6SS and T3SS is directly regulated by the RNA-binding protein RtcB controlling colonization, establishment, and pathogenicity in P. aeruginosa.111 YbeY regulates T3SS and T6SS secretion systems and biofilm formation by controlling RetS.112 The function of T3SS is regulated by various regulators, including four main regulators genes (exsA, exsC, exsD, and exsE), which is involved in the transcription activation of the aforementioned classical effectors (exoS, exoT, exoU, and exoY).72,113 ExoS is a 48.3 kDa protein containing 453 amino acid length. It has been reported early that ExoS participates in host cell apoptosis via its GAP region or ADP-ribosyltransferase (ADPr) activity.114,115 Furthermore, the ExoS possesses ADPRT activity, which induces P. aeruginosa-afflicted host cell apoptosis by targeting a variety of Ras proteins.116 ExoU is the longest P. aeruginosa effector containing 687 amino acids (73.9 kDa).117 ExoU is the most acutely cytotoxic among the four effector proteins because it can induce rapid cell death and is considered to be the main driver of the cytotoxic phenotype.118 ExoU dysregulates the host’s innate inflammatory response by poisoning and killing immune cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells, allowing bacteria to persist, proliferate, and spread, and ultimately leading to sepsis, Alzheimer’s disease, acute respiratory distress syndrome, etc.114 Mechanistically, ExoU transiently represses Capase 1 and NLRC4 inflammasome activation, inhibiting the release of IL-1β, IL-18, and proinflammatory DAMPs, and thereby suppressing the host immune response.119,120 In addition, ExoU can activate AP-1 transcription factors to increase IL-8 production and induce tissue-damaging inflammatory by JNK/MAPK) pathway.121 ExoT containing 457 amino acids (48.5 kDa) has GAP and ADPRT activities, and can induce host cell apoptosis by targeting Crk proteins phosphorylation of p38β and JNK induces apoptosis, which subsequently interferes with integrin-mediated survival signaling via destroying the stability of focal adhesion sites.122 Notably, recent studies have shown that P. aeruginosa ExoT induces G1 cell cycle arrest in melanoma cells, suggesting its potential for regulating the cell cycle.123 ExoY is a 378 amino acid protein with a molecular size of 41.7 kDa, detected in 80–100% of P. aeruginosa.124 ExoY plays a direct role in immune escape by inhibiting TAK1 activation, which is a key factor in the TGF-inducible pathway that directly modulates immune responses, contributing to P. aeruginosa survival and infection severity.125 In addition, ExoY regulates host inflammatory responses by delaying activation of NF-κB and caspase-1.126

Fig. 3.

Mechanisms of T3SS and T6SS in regulating bacterial pathogenesis and host responses in P. aeruginosa. LPS is recognized by TLRs (TLR1/2 or TLR4/9) and then activates T3SS and T6SS.479 T3SS and and T6SS represent a critical network in regulating bacterial behaviors (growth, biofilm formation, and competition) and host defense (host cell apoptosis, inflammatory response, colonization, and motility). T6SS and T3SS interaction and inter-conversion are regulated by RtcB and YbeY. ExoS/ExoU induce P. aeruginosa-afflicted host cell apoptosis and colonization by targeting JNKS signal pathway. ExoY/ExoT reduces inflammasome activity through inhibition of bacterial motility to dampen NF-κB and caspase-1 activation. T6SS is a powerful antibacterial weapon that can be injected through multiple effectors to compete with other bacteria and allows P. aeruginosa colonization and biofilm formation108,109

The T6SS components and their effectors are diverse and complex beyond bacterial-cell targeting. T6SS systems have been detected in ~200 Gram-negative bacteria, including P. aeruginosa.109 To compete for survival in the living environment, H1-T6SS kills other bacteria by injecting Tse2 effector molecules into other target bacteria possessing antibacterial activity and providing advantages for P. aeruginosa growth. In addition, to protect itself from Tse2 toxins, P. aeruginosa also produces the antitoxin Tsi2.127 Similarly, H1-Tse1 and Tse3 are injected into the periplasm of other bacteria to hydrolyze peptidoglycan, which can be counteracted by periplasmic immune proteins Tse1 and Tse3.128 Tse4, Tse5, Tse6, and Tse7 that also show antibacterial activity are associated with homologous immunity.129 The phospholipase D enzymes PldA and PldB of Tle5 were injected to other bacteria by H2-T6SS and H3-T6SS to exert antibacterial activity.130 Further, VgrG2b is injected into epithelial cells by H2-T6SS, in which it targets the γ-tubulin ring complex component (γ-TuRC) and promotes the recruitment of PI3K at the apical membrane.131,132 Moreover, PldA/B targets the host PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase)/Akt pathway to remodel the PIP3 (phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate) and actin in the apical membrane, which is essential for successful colonization of the host by P. aeruginosa.133 T6SS-related genes hcp1/hcp3 and lasR were significantly higher in the strong biofilm formation (SBF) compared to nonbiofilm formation (NBF) groups, which contributes to the biofilm production by P. aeruginosa.90 Collectively, T6SS is a powerful antibacterial weapon that can be injected with many different effectors to compete with other bacteria and allow P. aeruginosa colonization and biofilm formation.

Two-step secretion systems

Different from the One-Step secretion, Two-step secretion requires a brief periplasmic phase of the secreted proteins on the export route before being exported to the outside of the cell through general export pathways, which plays an important role in the transport of periplasmic and outer membrane proteins.

T2SS

The function of T2SS is one of the less characterized secretion systems and is thought to secrete folded proteins from the periplasm.134 Two different pathways exist in T2SS: the general secretory (Sec) and twin-arginine translocation (Tat).135 The secreted proteins are first transited through the inner membrane, stays briefly in the periplasm and then secreted into the extracellular environment.136,137 The Sec pathway consists of a protein targeting component, a motor protein, and a membrane integrated conducting channel called SecYEG translocase, the secreted proteins with a SecB-specific signal sequence might be guided to the periplasm or the extracellular environment.138 The twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway of Gram-negative consists of TatA and TatB, which can decide whether the secreted is retained in the periplasm or translocated to the extracellular space with a twin-arginine motif.139 Functionally, T2SS participates in the secretion of guanylate cyclase ExoA, proteases lasA/B and multiple other factors and many of which have emerged as potential therapeutic targets.140,141

T5SS

The T5SS of P. aeruginosa is composed of five subtypes (type Va to Ve) and exports the proteins across the inner membrane via the Sec pathway.142 The proteins of the V-type secretion system are often referred to as autotransporters (ATs). Typically, the T5SS consists of only one polypeptide chain with a β-barrel translocator domain in the membrane, and an extracellular passenger or effector region.143 Under the regulation of the Bam complex (β-barrel assembly mechanism) and TAM complex (translocation and assembly module), outer membrane proteins fold to form a β-barrel conformation and insert into the outer membrane.144 T5SS secretes a variety of proteins, including EstA, LepB, and LepA. EstA has esterase activity and is involved in rhamnolipid production and biofilm formation.143

The type Vb secretion system comprises two distinct polypeptide chains encoded in one operon, therefore, it is also known as the dual-partner secretion system (TPSS) containing the passenger domain (TpsA) and the β domain (TpsB).145 TpsA has a TPS secretion motif and a functional/catalytic domain and the TpsB is a 16-chain OM-integrating β-barrel protein with two periplasmic POTRA (polypeptide transport-associated) domains.146 The Vc-type secretion system forms a highly intertwined trimeric structure and is therefore also known as a trimeric autotransporter adhesin (TAA).147 The C-terminal β-barrel domain of the Type Vd consists of 16 β-strands, similar to the β-barrel of TpsB proteins.145 The Ve-type ATs share obvious similarities with Va-type ATs, the main difference is that Ve-type ATs have an inverted domain order, with the β-barrel at the N-terminus and the passenger at the C-terminus.148 Despite these preliminary studies, there is much more to be learnt regarding T5SS for the physiology and virulence in P. aeruginosa.

T4SS

T4SS is a multisubunit cell-envelope-spanning structure that can transfer protein and nucleoprotein complexes across membranes, which is related to horizontal gene transfer-mediated antibiotic resistance, adaptation, evolution, and virulence.149 T4SS in bacteria is divided into the IVA-type secretion system represented by Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 and the IVB-type secretion existed as Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system. Those distinct from the above are classified as “Other T4SS”, which contain genomic islands pKLC102 and PAPI in P. aeruginosa and are less characterized than other two types.149 P. aeruginosa T4SS comprises abundant major pilin subunits, PilA, and low abundance minor pilins FimU and PilVWXE. Both major pilin and minor pilins are processed by the pre-prepilin peptidase, PilD to exert function. T4SS assembly system is evolutionarily associated with T2SS contributing to the process of assembly and disassembly of pili. Minor pilins can impact assembly, retraction, extension, and adhesion.150

Again, the chief function of T4SS is horizontal genetic transfer (HGT) between different microorganisms and potentially relating to pathogenesis.151 For the genetic island containing T4SS, there is a discrepancy: whether a conjugation mechanism exists but this is likely related to differences between strains.152 Nevertheless, there are relatively limited studies of this system compared to other secretion systems such as T3SS. We will further discuss the potential role of T4SS in host response context, initiating/activating inflammasome independent on nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor (NLR) family CARD (C-terminal caspase recruitment domain) domain-containing protein 4 (NLRC4),153 in addition, the virulence factors and their associated secretion systems in P. aeruginosa were summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The virulence factors and their associated secretion systems in P. aeruginosa

| Secretion systems | Virulence factors | Features | Pathogenicity | Inhibition | Interaction\regulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Alkaline protease | Adherence and Colonization342 | Corneal infections | APRin363 | Ca2+372 |

| HasAp | Proliferation375 | Scavenges heme | Metal complexes382 | hasR | |

| T2 | LasB (elastase) | Biofilm formation353 | Antibiotic resistance | Ag-phendione, Cu(phendione)395 | IL-1β438, LasA384,395,397,404,438,451,458 |

| LasA | Biofilm formation and Colonization | Antibiotic resistance459 and Corneal infections370 | Satureja khuzistanica essential oil339,343,369 | LasD | |

| Phospholipase C (PlcH, PlcN) | Host inflammation regulation | Cell hemolysis and Neutrophil activity344,354 | Global regulator Anr | Ca2+, Pi, Zn+, PlcR1, PlcR2, IL-8375,385,420,421,440 | |

| PrpL protease | Biofilm formation | Wound healing and Corneal virulence403 | – | Iron, Pvds, AprA, LasB434,447 | |

| Lipases (LipA, LipC) | Motility, Biofilm formation and Rhamnolipid production | Enhanced PLC-induced 12-HETE and LTB4 generation | DsbC protein381 | PmrA/PmrB401,411 | |

| ToxA | Colonization and Proliferation | Impairment of host defense, Inhibition of protein synthesis and Interference with cellular immune functions | Norepinephrine340 | Iron and PvdS404 | |

| LapA (via Hxc T2SS) | Biofilm formation and Localization adhesin | Antibiotic resistance346 | – | LapF, c-di-GMP374,377,405,419 | |

| Mep72 | – | – | – | PopD, PcrV, ExoS, FliD | |

| T3 | ExoS | Avoid phagocytosis and Kill the host cell | Inhibition of autophagy and mTOR, ROS Production and Induces apoptosis | Cinnamaldehyde and Carvacrol and honey413,417 | RpoS, Rac116,418,429,444,449 |

| ExoY | Enhance acute pathogenicity and infection | Impairs endothelial cell proliferation and vascular repair116,418,429,444,449 | Aspirin | GSH, NF-κB, AP-1, TAK1 | |

| ExoT | Inhibition of internalization by epithelial cells and macrophages | Inhibits lung epithelial wound repair386,398,399,407,437 | – | RhoA, Rac1, Cdc42 | |

| ExoU | Overexpression efflux pumps and AmpC β-lactamase genes | Antibiotic resistance and Augments neutrophil transepithelial migration | Arylsulfonamides388,409,426 | NF-κB, IL-8/KC | |

| ExsE | Negative regulator of type III secretion gene430,455 | – | – | T3SS | |

| T5 | Esterase (EstA) | Enhanced rhamnolipid production, Cell motility and Biofilm formation | – | – | ExsC, ExsD443,448 |

| CupB5 | Activates alginate overproduction | – | – | AlgU, MucA, TpsB4\LepB381,390 | |

| Exoprotease (Lep) | Producing pyocyanin | – | – | Iron396 | |

| T6 | Tse1 (amidase) | Defense against other organisms | Lysis of cells | Tsi1 | Tsi1360 |

| Tse2 | Defense against other organisms | Lysis of cells | Tsi2 | Tsi2431 | |

| Tse3 (muramidase) | Defense against other organisms | Lysis of cells | Tsi3 | Ca2+, Tsi3416,445 | |

| Other secretion systems | HCN | – | – | – | Glycine, AlgR, LasR and RhlR382,383 |

| Pyocyanin | – | Interferes with multiple cellular functions | Baicalin, 4-aminopyridine | BrlR, PhzM383,387,397 | |

| Pyoverdine | High-affinity iron uptake from transferrin and lactoferrin | Keratitis | Phenylthiourea | PvdP tyrosinase439,446 | |

| Rhamnolipids | Biofilm formation | Potentiate aminoglycoside antibiotics | H2S | Oxygen, Polyhydroxyalkanoate371,418,421,422 | |

| Alkyl quinolones | Bacterial communication and quorum sensing | – | – | PqsR, LysR433 | |

| N-acyl homoserine | Biofilm formation | – | – | Propolis379 | |

| Lactones | Biofilm formation | Accelerate host immunomodulation | Th1 and Th2 cytokines401 | – |

Virulence regulatory systems

The regulation of all these virulence factors is cell density-dependent through release of autoinducers of critical quorum sensing (QS) (e.g., Las, Rhl, Pqs, and Iqs), a mass communication system.154 QS may help large population fitness by a hierarchical signal pattern to survive in fierce host environments and thrive, leading to persistent infection in individuals with cystic fibrosis, which cannot be completely cured even with tremendous progress in drug development, drastically improved medcare systems and living conditions.155 Hence, QS systems along with some other critical virulence factors, such as six types of secretion systems (of toxic molecules), two-component systems (TCSs), have become an intense interest in mechanistic understanding of this bacterium.

Quorum sensing is the most-studied systems for regulating gene expression and virulence

Roles and acting mechanisms of QS

QS describes a method that is widely utilized by bacteria for cell–cell mass communication. Both Gram-negative and -positive bacteria detect the local population density by sensing chemical signals and coordinate gene expression and group-beneficial behaviors.156,157 Bacteria produce autoinducer or quoromone as diffusion signaling molecules and release into the environment for communication. Once the population reaching a threshold, the autoinducers activate their cognate receptors to directly or indirectly induce gene expression.158 Over the past two decades, QS has been extensively studied as a potential target for ‘antivirulence agents’, which may be harnessed to counteract bacterial virulence via a noncytotoxic mechanism as alternatives of traditional antibiotics.159,160

Another essential function for QS in P. aeruginosa is to regulate the production of multiple virulence factors, such as extracellular proteases,161 iron chelators,162 efflux pump expression,163 biofilm development,164 swarming motility,165 and the response to host immunity.166 As a model organism, P. aeruginosa serves as one of the most suitable bacteria to study the fundamental mechanisms of QS signaling regulating virulence and search for chemical agents to block the QS system.167,168

Interaction between quorum-sensing systems and environments

Bacteria communicate with each other through the QS, which acts as a global regulatory system by directly or indirectly controlling the expression of genes, has been the central point of research.157 For example, scientists have made significant efforts in understanding the interactions between all the four QS systems and also how environmental cues may affect gene expression and function of the QS. Two canonical N-acyl L-homoserine lactone (AHL) based (Las and Rhl) and two 2-alkyl-4 quinolones (AQ) based (Pqs and its precursor Hhq) signaling systems.70 These systems connect and coregulate each other. Rhl and Pqs were positively regulated by the Las system, while Rhl represses Pqs and Pqs augments Rhl.169 For example, in response to various nutritional and environmental stimuli, the regulatory relationship between Rhl and Pqs systems can change independently of Las.170

The activation of QS genes generally requires a large number of regulatory factors to control receptor expression or function, and/or to coregulate some QS-controlled target genes since the QS systems are functional diverse, organizational complex, and consisting of a spectrum of key regulators (including rpoS, vqsR, mvfR, rhlR, rsaL et al.).171 RpoS indirectly plays a subtle role in activating lasR and rhlR expression and modulating ~40% QS-controlled gene expression during the stationary phase.172 VqsR controls the production of AHL signaling molecules and virulence factors by inhibiting the LuxR-type regulator QscR, which represses lasI expression to regulate the timing of QS activation.173 VqsM positively regulates the QS systems by controlling several relevant QS regulators ranging from QS to antibiotic resistance, and P. aeruginosa pathogenicity.174 MvaT and its homolog MvaU control the magnitude and timing of QS-dependent gene expression,175 which have a massive impact on all three QS systems by directly regulating lasR, lasI, rsaL, pprB, mvfR, algT/U, mexR, and rpoS.176 RsaL binds to the lasI promoter and prevents LasR-mediated activation, regulates las signaling,177,178 and modulates the activity of PqsH and a recently identified regulator, CdpR, which are required for PQS synthesis.179 AmpR activates QS-regulated genes to positively influence acute virulence, while negatively regulating biofilm formation.180 CdpR negatively modulates bacterial virulence by impacting the expression of pqsH, which is positively regulated by LasI and VqsM along with QscR and RsaL.181 We also recently found that BfmR/S and/or its variants modulate the rhl QS system in P. aeruginosa.182 Crc regulates rhl QS by promoting Hfq-mediated suppression of lon gene expression.183 More recently, our laboratory delineated that AnvM is a critical regulator of virulence in P. aeruginosa by directly interacting with the QS regulator MvfR and anaerobic regulator Anr.184 The aforementioned discoveries have highlighted the rapid progress in understanding diverse, heterogenous regulatory mechanisms of QS coordinated by seemingly a large number of unprecedented factors, which may finally characterize powerful, versatile regulatory proteins or systems to be applied to better control the notorious pathogen.

Several factors (such as QscR and QteE) have been identified to regulate the activation threshold of quorum-regulated genes, which control QS activation timing through additional homeostatic mechanisms.174 In addition to the QscR mentioned above, QteE also blocks QS-regulated genes’ expression by preventing LasR and RhlR accumulation and blocking Rhl-mediated signaling.185 Moreover, QslA is found to interact with LasR.186

Based on extensive studies to date, we may presume that QS may be one of the most important regulatory systems in Pseudomonas contributing substantially to bacterial physiology, adaptation, and pathogenesis. Although, various studies have tested the ideas of targeting QS for potential therapy of bacterial infection, the effect of using QS-associated approach for treatment is unsatisfactory.187 In particular, there were only limited reports of in vivo treatments targeting QS.188 Hence, it is necessary to further study the fundamental role of QS in bacterial pathogenesis and identify new anti-virulence targets and approaches that would help develop urgently needed medicines for treating refractory infection in clinics for QS bearing bacteria.

The two-component regulatory systems are critical gene regulators and virulence factors

The two-component systems (TCSs) are ubiquitous, complex signaling regulators that play vital roles in bacterial survival, metabolism, and virulence.189 As a versatile opportunistic pathogen, P. aeruginosa virulence network is tightly controlled by a growing number of TCSs.190 In general, a TCS pair of genes consists of a membrane-bound sensory histidine kinase (HK) and a cytoplasmic response regulator (RR). In P. aeruginosa, 64 HKs and 72 RRs have been identified.191 More than 50% of the TCSs and their corresponding HKs are linked to virulence and/or antibiotic resistance of P. aeruginosa.192 For instance, CzcR/CzcS is implicated in carbapenem-resistance;193 KinB/AlgB is involved in the alginate synthesis and virulence;194 and GacS/GacA is essential for pathogenicity.195 Remarkably, an attenuation in virulence behavior can be achieved by blocking TCS signaling. Goswami et al. reported that inhibition of HKs, especially Rilu-4 and 12, significantly reduced the production of virulence factors and toxins, and severely impacted the motility behavior of PA14.195

Our recent studies discovered a new copper-responsive TCS called DsbRS in P. aeruginosa, in which DsbS (sensor of histidine kinase) and DsbR (cognate response regulator) modulate gene transcription for disulfide bond formation (Dsb). DsbS (phosphatase) targets DsbR to interfere with the transcription of Dsb genes and help the bacterium cope with copper stress.196 Intriguingly, transcription factors can also regulate the behaviors of bacteria to adapt host environments; for instance, imidazole-4-acetic acid (ImAA) and its receptor HinK are recently implicated in the response of P. aeruginosa to histamine.197 These findings help understand the communication between P. aeruginosa and hosts to adjust bacterial health. We have summarized TCSs and their roles in controlling the key virulence factors in P. aeruginosa (Table 3).

Table 3.

The composition and function of the two-component regulatory systems

| Composition | Virulence factor | Function |

|---|---|---|

| PilSR | Type IV pili460 | Twitching and Swimming Motilities |

| RocS1-RocR-RocA1 | CupC fimbriae461 | Biofilm formation/Antibiotic tolerance |

| FimS-AlgR, KinB-AlgB | Alginate462 | Exopolysaccharide alginate synthesis |

| BfiSR | Rnase G463 | Regulation sRNA levels |

| GacSA, RetS | Exopolysaccharides (Pel, Psl)464 | Biofilm formation |

| RcsCB, PvrSR | CupD fimbriae204 | Fimbriae assembly/Biofilm formation |

| BfmSR | Edna465 | Bacteriophage-mediated lysis and DNA release/Biofilm formation |

| PprAB | Cup E fimbriae466 | Fimbriae assembly/Biofilm formation |

| BqsSR | Rhamnolipid467 | Quorum sensing-dependent biofilm |

| FleSR | Flagella468 | Flagellar biogenesis |

| FimS-AlgR | Type IV pili469 | Twitching motility/Biofilm maturation, Surface adhesion/Virulence |

| PA2573-PA2572 | ExoS469 | Virulence and antibiotic tolerance |

| TtsSR | CbpE470 | Specific secretion of the CbpE chitin-binding protein |

| GtrS-GltR | ToxA471 | The expression of exotoxin A and glucose catabolic enzymes |

| GacS-LadS-RetS, CsrA/RsmA | Type III secretion472,473 | Virulence/Secretion systems/Biofilm formation, Quorum sensing/Motility |

| RsmA | Elastase474 | Pyocyanin, rhamnolipids and elastase production |

| LadS | ExoU475 | Virulence and the switch between acute and chronic infections |

| RocS1-RocR-RocA1 | ExoY, ExoT476 | Biofilm formation |

| CbrAB | ExoT, ExoS477 | Metabolism, virulence, and antibiotic resistance |

| FimS-AlgR | Regulated by PilY1469 | Virulence |

The number of TCSs related to the virulence of P. aeruginosa has recently grown considerably, which may be highlighted by the multi-kinase networks containing multiple sensor kinases through crosstalk (network) to impact virulence.192 The networks include: (1) GacS network governs the switch between acute and chronic infections;198–201 (2) Roc network and Rcs/Pvr network control cup fimbriae production;202–204 (3) A complex network of five TCSs (PmrB, PhoQ, ColS, ParS, and CprS) regulates the aminoarabinose modification of lipopolysaccharide;205–207 (4) Wsp chemosensory pathway modulates biofilm formation and chronic infection;208,209 and (5) Chp/FimS/AlgR network involves biofilm formation and virulence.210,211 Although TCSs may control many functions, some of them may have unknown roles that require further studying. TCSs play a significant role in controlling either P. aeruginosa virulence or virulence-related behaviors (such as biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance). The functions of TCSs may contribute to the clinical significance exemplified by a more recently identified BfmRS TCS.182 Indeed, the plasticity of TCSs mediated by spontaneous mutations of BfmRS in patients has been assessed, and the data suggest that mutation-induced activation of BfmRS may be related to host adaptation by P. aeruginosa in chronic infections.212 Despite increasing identification of novel TCSs, several critical questions remain to be answered in future investigation: how multi-kinase networks process and integrate signals, which of the kinases plays a dominant role in multi-kinase networks, and how these TCSs interact with other systems, quorum sensing and secondary messenger signals to confer pathogenicity (e.g., cAMP and c-di-GMP).

Small non-coding regulatory RNAs play roles in regulating gene expression and virulence

Small non-coding regulatory RNAs (sRNAs) range from 50 to 400 nucleotides in length.213 Since the discovery as part of a large group of transcriptional regulators in Escherichia coli in the 1960s, sRNAs are gradually recognized as key modulators to mount rapid responses when necessary and are encoded widespread in the bacterial genomes213–215 despite to different extent (the number of sRNAs in PAO1 is approximately twice higher than that in PA14). sRNAs play an essential role in bacterial pathogenicity and virulence mechanisms, such that participation in quorum-sensing regulation, ion metabolism, biofilm formation, stress responses, host cell invasion, and adaption to growth conditions.216–218 Hfq-dependent sRNAs are instrumental for modulating P. aeruginosa virulence.219 rsmY and rsmZ act as early responders to finely modulate bacterial cooperation under environmental stimuli to optimize population density.220

In P. aeruginosa, sRNAs can regulate bacterial metabolism instantly and precisely to establish successful infection in the hosts.218 A total of 573 sRNAs were detected in PAO1 and 233 sRNAs in PA14, indicating their quantity variation in different strains.201 Although 126 sRNAs are found in common to both strains, sRNAs can evolve rapidly, and many sRNAs exhibit strain‐specific or environmental-dependent expression.221 Interestingly, we recently revealed that sRNA PhrS may help generate CRISPR RNA (crRNA) for initiating bacterial immunity against bacteriophages, which is achieved through inhibiting Rho function on transcription-termination.222 Collectively, it would be intriguing to further understand the functions and underpinning mechanisms involving sRNA in this bacterium, which may identify novel pathway regulators and drug targets for controlling bacterial invasion.

Acquisition of antibiotic resistance contributes to bacterial survival and thriving

The acquisition of drug resistance by P. aeruginosa depends primarily on multiple intrinsic and acquired antibiotic resistance mechanisms, including the biofilm-mediated formation of resistant and multi-drug-resistant persistent cells.223 Therefore, P. aeruginosa can quickly develop resistance to various antibiotics, including aminoglycosides, quinolones, and β-lactams.224

In the course of long-term evolution, bacteria have developed a variety of ancient genetic resistance mechanisms that have significant genetic plasticity against harmful antibiotic molecules, enabling them to respond to various environmental threats, including possible harm (e.g., antibiotics, chemical compounds, and antimicrobial peptides) to their survival. The acquisition of antibiotic resistance with P. aeruginosa is quite diverse, and some primary mechanisms including outer membrane permeability, efflux systems, and antibiotic-inactivating enzymes will be addressed below225 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in P. aeruginosa. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in P. aeruginosa can be divided into intrinsic antibiotic resistance (① outer membrane permeability, ② efflux systems, and ④antibiotic-modifying enzymes or ⑤ antibiotic-inactivating enzymes), acquired antibiotic resistance (⑥ resistance by mutations and acquisition of resistance genes), and adaptive antibiotic resistance (③ biofilm-mediated resistance). Alteration of outer membrane protein porins decreases the penetration of drugs into cells by reducing membrane permeability. The efflux system directly pumps out drugs. Drug-hydrolyzing and modification enzymes render them inactive. Similarly, some enzymes cause target alterations so that the drug cannot bind its target, resulting in drug inactivity. Antibiotic resistance genes carried on plasmids can be acquired via horizontal gene transfer from the same or different bacterial species,225 quorum-sensing signaling molecules activate the formation of biofilms, which act as physical barriers and prevent antibiotics penetrating the cell

Outer membrane permeability

To treat P. aeruginosa infections, most antibiotics need to penetrate the cell membrane to reach the intracellular compartment to function.226 The outer membrane of P. aeruginosa can act as a specific hurdle inhibiting antibiotic penetration. The outer membrane of P. aeruginosa is chiefly composed of bilayer phospholipid molecules, LPS and porins embedded in phospholipids. The outer membrane is responsible for the specific and non-specific uptake of extracellular substances relying on different porin functions, including non-specific porins (OprF), specific porins (OprB, OprD, OprE, OprO, and OprP), gated porins (OprC and OprH), and efflux porins (OprM, OprN, and OprJ).227–230 P. aeruginosa manipulates different porins to limit antibiotic penetration and increase antibiotic resistance. OprF promotes the formation and attachment function of P. aeruginosa biofilm to protect the bacterium against antibiotics.231–233 Mutations of specific porins OprD involving conformational features cause carbapenem resistance, a serious challenge for medical treatment practices.234 Outer membrane protein H (OprH) of P. aeruginosa enhances the stability of the outer membrane through direct interaction with LPS to regulate antibiotic resistance.235,236 Efflux porins (OprM, OprN, and OprJ) contribute to the active efflux of several antibiotics, including tetracycline, norfloxacin, and β-lactam antibiotics.237 These findings demonstrate that the elegant effects and diverse mechanisms by which porins determine antibiotic resistance.

In a separate account, in recent years, OMVs secreted by P. aeruginosa are shown to be able to transport multiple virulence factors, like hemolytic phospholipase C, mRNA, DNA, β-lactamase, alkaline phosphatase, to the host cytoplasm, which may be a part of pathogenic mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. OMVs may be fused with the host plasma membrane through receptor-mediated endocytosis. While OMVs are detrimental to the host by delivering antibiotic resistance molecules or enzymes (β-lactamase), they have been harnessed as alternative delivery vehicles for transporting treatments or vaccines for various diseases including infection and cancer.47,238

Efflux systems for pumping off drug resistance factors

The toxic compounds derived from metabolism or antimicrobials inside bacterial cells are harmful to bacterial survival, and require mechanisms to expel. The efflux pump is a main, conserved mechanism to remove antibiotics. The efflux pump may upregulate virulence genes (QS) for enhancing antibiotic resistance and maintaining bacterial homeostasis. Currently, five components are described in the efflux pump family: ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily, major facilitator superfamily (MFS), and multidrug, toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family, resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family, and small multidrug resistance (SMR) family.239 Among all efflux pumps, the RND efflux pump family has the strongest correlation with antibiotic resistance. Twelve RND family efflux pumps are identified in P. aeruginosa: multidrug efflux AB-outer membrane porin M (MexAB-OprM), multidrug efflux CD-outer membrane porin J (MexCD-OprJ), multidrug efflux EF-outer membrane porin N (MexEF-OprN) and multidrug efflux XY-outer membrane porin M (Mex XY-OprM) can increase resistance to a variety of antibiotics through efflux.240 MexAB-OprM is crucial for developing carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa, which is a lingering clinical issue.237 Upregulation of MexCD-OprJ is closely associated with increased resistance of most clinical strains to ciprofloxacin, cefepime, and chloramphenicol.241 Quinolones MexEF-OprN are overproduced by the QS deficiency due to kynurenine extrusion.242 Furthermore, the resistance of P. aeruginosa to aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and zwitterionic cephalosporins depends on the efflux function of MexXY-OprM.243 These findings suggest that despite some similarity in substrates, their affinity of efflux pumps may vary greatly, displaying different extent of anti-antimicrobial activities.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that the chief mechanism for P. aeruginosa success in infection is highly related to its stubborn resistance to antibiotics or other therapeutics, which is regulated by the efflux pump. Hence, targeting this mechanism such as inhibiting the critical efflux pump—mexAB-oprM or enhancing the repressor—mexR, will likely reveal new strategies to overcome antibiotic resistance mechanisms in the bacterium and achieve the improved treatment efficacy.244

Antibiotic-inactivating enzymes that cleave enzymatic drugs

Antibiotics often contain chemical bonds (e.g., amides and esters), and bacteria can produce antibiotic-inactivating enzymes (hydrolase) to degrade or alter antibiotics, leading to antibiotic resistance.245 P. aeruginosa is highly resistant to various antibiotics including penicillin, cephalosporin, and aztreonam by producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs).246,247 In addition, the bacterium is also resistant to the cefazolin-tazobactam combination therapy via ESBL GES-6.248 Again, the ESBL of P. aeruginosa is thought to be the most significant mechanism in terms of countering antibiotics, which would be a major target for designing and developing the most potent antimicrobial drugs.

From enzymatic angles, P. aeruginosa can modify the amino groups and glycosidic groups of aminoglycoside antibiotics to produce antibiotic resistance. The currently known aminoglycoside modifying enzymes utilize three common mechanisms: aminoglycoside phosphotransferase (APH), aminoglycoside acetyltransferase (AAC), and aminoglycoside nucleotide transferase (ANT).249,250 These enzymes trigger the resistance of different antibiotics through various mechanisms, providing powerful resistant activities towards different types of antibiotics. APH can inactivate streptomycin by transferring the phosphate group to the 3′-hydroxyl group of aminoglycosides.251,252 AAC may cause gentamicin resistance by transferring the acetyl group to the amino group at the 3′ and 6′ positions of the aminoglycoside.253 ANT confers P. aeruginosa resistance to amikacin by transferring adenosine groups to the amino or hydroxyl groups of these aminoglycosides.254 The diverse enzyme list is growing (currently more than 50 enzymes), which helps in bacterial success in the anti-drug battle with humans.

Acquiring the antibiotic resistance throughout bacterial life cycle

Bacteria can acquire antibiotic resistance through mutations or horizontal gene transfer.255,256 Mutations of OprD in P. aeruginosa confers resistance to carbapenems234 and mutations of DNA gyrase (GyrA) causes resistance to quinolone antibiotics.257 Importantly, mutations in the β-lactamase gene ampC causes a significant increase in resistance to cephalosporins.258 There are already a host of enzymes in this bacterium may counter antibiotics while it continues to gain new resistance factors, which is debatably the biggest challenge for drug industry and scientific research. As bacteria can conveniently obtain antibiotic resistance genes from the same or different bacterial species through horizontal gene transfer, despite challenging targeting this mechanism may be a niche to search for better treatments.259 A typical example is that P. aeruginosa may obtain aminoglycoside and β-lactam resistance genes through horizontal gene transfer from the environment or other microbes at an unpredictable, fast pace,223,260 it may be highly difficult for scientists and clinicians to design new tools in impeding this natural robust mechanism in this bacterium.

Adaptive antibiotic resistance

When facing the diverse environmental stimuli, bacteria obtain adaptive resistance to increase the resistance to antibiotics through transient changes in gene and/or protein expression by a spectrum of approaches.261 In P. aeruginosa, the formation of biofilms is the most typical strategy to acquire adaptive antibiotic resistance.262,263 P. aeruginosa can produce biofilms to enhance pathogenicity. Meanwhile, P. aeruginosa infection can also cope with antibiotic treatment by forming persistent cells or persisters, thereby preventing the synthesis of antibiotic targets.223,262,263 Persistent molecules from the persisters can maintain vitality and refill biofilms; once antibiotics are not present, bacteria will resume growth and cause chronic infections.264

Altogether, P. aeruginosa can become exceedingly resistant to antibiotics through myriads of mechanisms, and currently we probably only know a tip of iceberg regarding these bacterial behaviors. It necessitates accelerated research efforts to fully understand the detailed mechanisms by which bacteria constantly grow antibiotic resistance, providing insight into the design and development of innovative and efficious drugs to overcome drug resistance.

Highly complex and multiple mechanisms in host immune responses to the bacterium

The opportunistic pathogen P. aeruginosa exists almost everywhere and in any environmental conditions. In immunosuppressed people, there is extreme susceptibility to P. aeruginosa infection, developing either acute or chronic phenotypes. As the first line of host defense systems, the innate immune system plays a vital role in battling with P. aeruginosa via multiple mechanisms, such as phagocytosis and inflammatory responses. Several types of host systems, such as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), plasma membrane signals, intracellular enzymes, and secreted cytokines/chemokines participate in inflammatory response against the bacterial infections. Although a well-balanced inflammatory response is required for restraining P. aeruginosa invasion, overzealous inflammation is associated with rapid disease progression, tissue injury, and even death. Some host molecules including cytosolic protein annexin A2 (AnxA2), autophagy-related protein 7 (ATG7), NLRC4, as well as non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs and microRNAs), are also implicated in P. aeruginosa-induced inflammation and/or other aspects of host defense mechanisms,265–267 and understanding of the mechanisms of inflammatory response is just beginning to be unfolded.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) instantly recognize invasive pathogens

TLRs are highly conserved transmembrane PRRs, containing leucine-rich repeats and Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) homolog domains, which rapidly recognize invading microorganisms and elicit innate immunity and inflammatory response upon bacterial invasion.268 TLRs play vital roles in initiating innate immunity for eradicating invading pathogens.269 Upon the sensing of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), TLRs activate NF-κB and AP-1 to mediate inflammatory response signal pathways.270 Correspondingly, TLRs are capable of recognizing different pathogen-associated molecular patterns found in P. aeruginosa. LPS is a major component of the outer membrane of P. aeruginosa, responsible for maintaining bacterial membrane structure and initiating immune response as a major antigenic factor. Research shows that a large amount of hex-acylated lipid A from LPS is isolated from infected patients, which is a strong TLR4 agonist, capable of activating TLR4-dependent inflammatory response.271,272 In addition, several TLR4 co-receptors MD-2 and CD14 are indicated necessary for TLR4 recognition of LPS and TLR4 activation.273 Airway epithelial cells and macrophages, both expressed TLR4 in the cell membrane, serve as the first line of host defense for the initial contact to P. aeruginosa. As TLR4 is the essential trigger of host immunity against P. aeruginosa infection, its deficient mice show higher bacterial burdens and severe lung injury under infection.274 Nevertheless, the TLR4 pathway does not function alone and is very complex, which may be impacted or coregulated by a number of signaling systems including AnxA2,275 autophagy,276,277 inflammasome,278 cGAS,279,280 ion channel proteins,281 DNA repair proteins,282 miRNAs,40,266,283 and lncRNA,229 to name a few.

Apart from TLR4, TLR2 has also been reported as an LPS recognizer, which is capable of recognizing P. aeruginosa‐derived lipoproteins and T3SS effector ExoS.269 In addition, TLR5 is responsible for detecting P. aeruginosa flagellin, which can induce specific inflammasome.284 TLR9 is responsible for detecting P. aeruginosa unmethylated bacterial CpG DNA intracellularly.285 Interestingly, TLR9 is also activated by P. aeruginosa infection-induced mtDNA release (Wang Biao et al., under revision, Immunology).

Although paradoxical at times, TLRs are arguably the single most important PPRs for initiating the initial recognition to mount a robust immune defense against both bacteria and viruses. It is imperative that scientists be focused on verifying the roles of played out by TLRs using a comprehensive approach or systems biology in an unbiased manner in animals as well as human subjects,277 which may provide insight into the disease pathogenesis and suggesting new therapeutic development.

Inflammasomes drive inflammation and pyroptosis

The inflammasome is a multiprotein complex, which is attributed to the production and release of inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and IL-18.286,287 Recent work reveals that inflammasome is involved in pyroptosis dependent on the cleavage of Gasdermin D, which contributed to the formation of plasma membrane pores, and in turn promoting the release of inflammatory cytokines and pyroptosis.288,289 Typically, inflammasome consists of cytosolic PRRs, ASC (an apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD), and caspase 1. Inflammasome PRRs are responsible for detecting exogenous PAMPs like TLRs, which are also essential for monitoring P. aeruginosa invasion and activate host inflammatory response for promoting the clearance of P. aeruginosa.269,290 Remarkably, TLRs are involved in the priming of inflammasome activation by promoting the transcription of inflammasome-related genes.290 NLRC4 and AIM2 (absent in melanoma 2) are well characterized among numerous inflammasome PRRs linked to infection of P. aeruginosa.

NLRC4 inflammasome is shown capable of recognizing needle and inner rod (PrgJ) T3SS proteins, independently of T3SS exotoxins, or intracellular flagellin utilizing different murine NAIP as adaptors.291–294 Unexpectively, only one factor, human NAIP (hNAIP), has been found, homologous to murine NAIP5, responsible for sensing P. aeruginosa T3SS inner-rod protein PscI and needle protein PscF.295 Apart from T3SS, the T4SS pilin is also capable of activating inflammasome independent of NLRC4 and ASC.153 P. aeruginosa-induced mitochondrial dysfunction also promotes the assembly and activation of NLRC4 via T3SS.296 Mitochondrial ROS and release of mitochondrial DNA are key to NLRC4 activation under P. aeruginosa infection, which is also dependent on autophagy.296 Removal of damaged mitochondria blocks the activation of NLRC4.296 However, AIM2 appears to be dispensable for recognizing and promoting P. aeruginosa infection-induced inflammation in most cases.297

Although several P. aeruginosa components are implicated in activating inflammasome-related immune defense, little is known about how the bacterium evades immune response after inflammasome activation.298 Recent research broadens our knowledge that P. aeruginosa takes advantage of bacterial QS-dependent secretant, including proteases, pyocyanin, and 3-oxo-C12-HSL, to inhibit the activation of NLRC4 or NLR family, pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes.298 A further study supports that pyocyanin specifically inhibits activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome (but not NLRC4 and AIM2) through induced excessive oxidation,299 contrary to the positive role of oxidation in NLRP3 activation.300 Hence, the potential role of oxidation in P. aeruginosa infection and inflammasome activation requires further study. In addition, K+ efflux is necessary for the activation of inflammasome against P. aeruginosa infection.301

To date, the role and underlying mechanisms of the inflammasome in host defense against P. aeruginosa remain largely unclear and sometimes paradoxical: some researches show that inflammasome activation enhances host defense to clear P. aeruginosa,302,303 whereas others present opposite results that inflammasome activation triggered severe host tissue damage, which may impact disease progression and mortality.304,305 One explanation for such a mixed response is that infection may involve different pathways dependent on the bacterial strains, model systems, environments, and experimental conditions. Another caveat is that most experiments have not been performed at holistic and/or spatiotemporal levels to evaluate the dynamics, rather a single cell type, specific location, and one or two timepoints. Therefore, enhanced or advanced approaches are needed to further clarify the role and underlying regulatory mechanisms of inflammasome activation in P. aeruginosa infection.277

Nucleic acid sensor cGAS is pivotal for eliciting immune reaction

cGAS is a recently discovered nucleic acid sensor that is initially identified to recognize viruses.306 Typically, activation of cGAS contributes to the induction of inflammasome as a means against viral or intracellular bacterial infection.307 However, the latest research shows that cGAS downstream effector STING may also play an anti-inflammatory role under extracellular bacterial P. aeruginosa infection by inhibiting NF-κB activity.308 More recently, we have found that cGAS may be involved in an uncoupled protein response (UPR) during P. aeruginosa infection. Mechanistically, our studies uncover cGAS as a novel nucleic acids’ sensor to initiate immune responses against P. aeruginosa infection through a canonical pathway involving STING and IRF-1,280,309 suggesting that cGAS pathways may be a critical target for control of this bacterium. It is a new and important function for cGAS since previous reports were primarily focused on viral sensing and intracellular bacterial sensing.

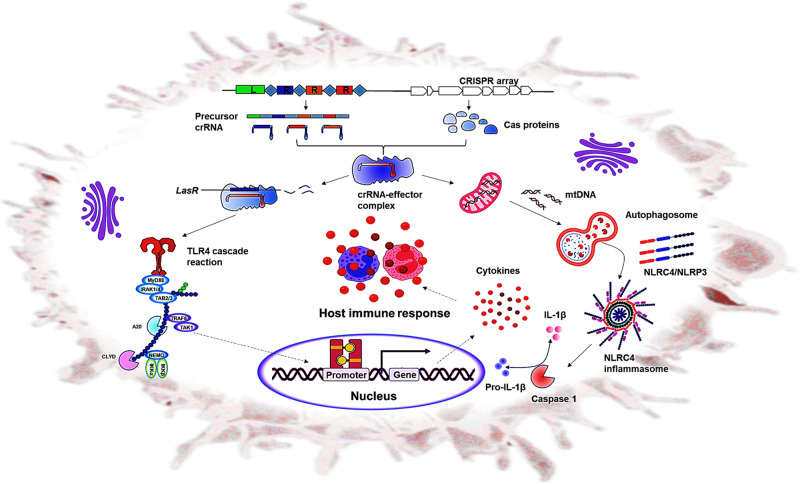

CRISPR-mediated adaptive immunity, a double-edged sword for bacterial self-survival and invasion

CRISPR-Cas (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-CRISPR-associated) is widely existing in bacteria and archaea providing protection against genetic intruders (plasmids), phages (phage) and other parasites.310 To date, two classes, six types of CRISPR-CRISPR-associated (Cas) systems, based on the characteristic of Cas proteins, are present in bacteria.311–313 Class I CRISPR-Cas systems (types II, V, and VI systems) rely on multiple CRISPR-Cas protein effector complexes, while Class II CRISPR-Cas systems (types I, III, and IV systems) are dependent on a single CRISPR-Cas effector protein.314–316 CRISPR-Cas I-C, type I-E and type I-F systems have been found in many clinically isolated P. aeruginosa.317,318 It is known that CRISPR-Cas systems provide adaptive immunity against the invasion of bacteriophages or plasmids.319 However, the role of CRISPR-Cas systems is far beyond the adaptive immunity of bacteria based on the current reports.320 Our research showed that type I CRISPR-Cas targeted the QS regulator LasR to inhibit toll-like receptor 4 recognition, thereby evading mammalian host immunity, suggesting that the CRISPR system is linked to host immunity modulation by targeting their own genes, potentially evading host defense mechanisms.321 Type I CRISPR-Cas systems may elicit inflammasome activation in mammalian hosts by regulating autophagy in P. aeruginosa.278 To ensure maximum CRISPR-Cas function, P. aeruginosa PA14 utilized quorum sensing to activate the expression of cas genes to promote CRISPR adaptation when bacteria are at high risk of phage invasion.322 The adaptability and virulence of P. aeruginosa can be regulated by CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity based on the biological complexity of microbial communities in natural environments.323 The CRISPR-Cas system actively maintains the virulence of P. aeruginosa by limiting virus-like accessory genomic elements.324 Increased expression of phage-related genes initiates CRISPR-mediated biofilm-specific death of P. aeruginosa.325 CRISPR-Cas systems may help mediate antibiotic resistance to multiple membrane irritants, including enhancing the integrity of the envelope in pathogen Francisella novicida.326 Consequently, various corresponding anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins have evolved by phages to inhibit bacterial CRISPR systems.315,327–333 Our previous research identified a series of type VI-A anti-CRISPRs (acrVIA1-7) genes that block the activities of Type VI-A CRISPR-Cas13a system,333 and designed Type III CRISPR endonuclease antivirals for coronaviruses (TEAR-CoV) as an experimental therapeutic to combat SARS-CoV-2 infection,334 suggesting that exploiting the mechanism of CRISPR-mediated adaptive immunity has great potential for treating bacterial and viral infections. However, it is not clear whether CRISPR-Cas systems can regulate antibiotic resistance in P. aeruginosa, which may be studied in future (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

CRISPR-mediated adaptive immunity. Type I-C, type I-E, and type I-F CRISPR-Cas systems have been identified in P. aeruginosa. Type I CRISPR-Cas targeted endogenous LasR gene to decrease TLR4 expression and TLR4-mediated host inflammatory responses. Similarly, type I CRISPR-Cas systems elicited inflammasome activation by promoting mitochondrial-mediated autophagy. Ultimately, CRISPR-mediated adaptive immunity helps P. aeruginosa evade mammalian host immunity

Development of novel therapeutics for P. aeruginosa is not up to the speed

P. aeruginosa have strong ability to develop natural and acquired drug resistance through various mechanisms, including the production of antibiotic inactivating enzymes or antibiotic modifying enzymes, inhibiting the penetration of the drug through the cell wall, changing the target of antibacterial action, and limiting the drug to reach its target and adaptation to the adverse environment.223 Due to the increasing difficulty in treating antibiotic resistance strain infection, the development of the anti-P. aeruginosa therapy depends on targeting the resistance mechanism. Research on the resistance mechanism of P. aeruginosa has been an urgent topic for decades since antibiotic resistance has escalated exceedingly. Even with the intense interest, development of new antibiotics and other therapeutic strategies for P. aeruginosa infections is at a painstakingly slow pace due to the variability and complexity of drug resistance, as well as the lack of a deep understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms for P. aeruginosa. Designing effective therapeutic approaches (including phage therapy, immunotherapy, gene editing therapy, antimicrobial peptides, and vaccine therapies) to counteracting P. aeruginosa invasion has been an increasing urgency, requiring consorted efforts (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Novel therapeutics for P. aeruginosa. Multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa poses a major challenge to traditional antibiotics therapeutics, which have limited efficacy and cause serious side effects. Phage therapy, immunotherapy, gene editing therapy, antimicrobial peptides, and vaccine therapies have become the most promising strategy and garnered great expectations to overcome multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. A full-scale network of regulatory understanding of P. aeruginosa virulence is expected to be unveiled, thus, we will be in a much better position for rationale drug design to control Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections

New antibiotic formulations and compounds

With an alarming rise in pathogens with resistance to existing drugs, a number of new antibiotics have recently entered the antibiotic development pipeline; however, the hope for patients and clinicians is rapidly dwindling once a new antibiotic resistance strain emerges. Hence, we should invest unconventionally research efforts in searching for new treatments of MDR bacteria. Recently developed antimicrobials are discussed below.