19.1. Introduction

Redox (portmanteau of reduction-oxidation) reactions involve the transfer of electrons between chemical species in biological processes fundamental to life. It is of outmost importance that cells maintain a healthy redox state by balancing the action of oxidants and antioxidants; failure to do so leads to a multitude of diseases including cancer, diabetes, fibrosis, autoimmune diseases, and cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. From the perspective of precision medicine, it is therefore beneficial to interrogate the redox phenotype of the individual—similar to the use of genomic sequencing—in order to design tailored strategies for disease prevention and treatment. This chapter provides an overview of redox metabolism and focuses on how mass spectrometry (MS) can be applied to advance our knowledge in redox biology and precision medicine.

19.1.1. Genesis and Pathophysiological Function of Reactive Oxidants

Since the atmosphere of Earth became aerobic around 600 million years ago as a result of photosynthetic activities [1], oxygen-related redox reactions took center stage and inevitably a collection of chemical species called reactive oxygen species (ROS) arose as byproducts of aerobic metabolism. ROS can be both radical and non-radical; the most known examples include superoxide anion (O2·−), hydroxyl radical (·OH), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Mitochondria, specifically the respiratory chain (complexes I and III) located on the inner membrane, are the primary cellular source of ROS generation, producing O2·− by the one-electron reduction of O2. O2·− can quickly be dismutated to H2O2 through the activity of superoxide dismutases (SODs; SOD2 isoform in mitochondria). In the presence of ferrous iron (Fe2+), ·OH can be generated from H2O2 through Fenton reaction (Fig. 19.1). Other sources of ROS include peroxisomes (acyl-CoA oxidases, xanthine oxidase), endoplasmic reticulum (cytochrome P450), and plasma membrane (NADPH oxidases, lipoxygenases). Besides, many exogenous sources can drive ROS production as well, such as environmental stressors (e.g., UV light, air pollutants, toxins), pathogens, and certain therapies (e.g., cancer chemoradiation therapies). Although the following discussion focuses on the metabolism and function of ROS, one should also be aware that ROS serves to generate other groups of reactive species: reactive nitrogen species (RNS; e.g., peroxynitrite (ONOO−)), reactive sulfur species (RSS; e.g., persulfides (-SSH), polysulfides (-S(S)nSH)), and others.

Fig. 19.1.

Major pathways of ROS metabolism and impact of ROS on biomolecules. O2 −, H2O2, and OH are the major forms of ROS. O2 − can be dismutated to H2O2 by SOD. H2O2 can be dismutated to water by CAT, PRX/TRX/TR, or GPX/GSH/GR systems using in the case of PRX and GPX systems the reducing power of NADPH. ROS can oxidize small molecules, DNA, lipids, and proteins, producing a wide range of oxidation products. 4-HNE, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal; 8-oxo-dA, 8-oxo-2′-deoxyadenosine; 8-oxo-dG, 8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine; CAT, catalase; Cys, cysteine; CySS, cystine; E+, ethidium; GPX, glutathione peroxidase; GR, glutathione reductase; GSH, glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; Pro, proline; M1dG, 3-(2-deoxy-β-d-erythropentafuranosyl)pyrimido[1,2-α]purin-10(3H)-one deoxyguanosine; MDA, malondialdehyde; Met, methionine; NADP+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; PRX, peroxiredoxin; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TR, thioredoxin reductase; TRX, thioredoxin; Tyr, tyrosine

The role of ROS is dichotomous and complex. On the one hand, ROS have been regarded traditionally as unavoidable malign agents that can damage essential cellular macromolecules like DNA, lipids, and proteins (Fig. 19.1). ROS can react with both the bases and deoxyribose backbone of DNA, leading to base loss, single- and double-strand breaks, DNA-DNA crosslinking, and DNA-protein crosslinking. Among all the oxidative DNA modifications, 8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG) is the most common and best-studied lesion and is considered a biomarker of oxidative DNA damage. In addition, ROS can also induce lipid peroxidation, which disrupts membrane lipid bilayer structure and inactivates membrane-bound enzymes and receptors. Products of lipid peroxidation, such as malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), and isoprostanes, have been used for decades as biomarkers of oxidative stress. Finally, ROS can directly damage proteins causing cleavage of peptide bonds via the diamide pathway or α-amidation pathway [2]. ROS can also attack amino acid side chains, primarily sulfur-containing residues cysteine (Cys) and methionine (Met), and aromatic residues tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine (Tyr) resulting in protein crosslinking, denaturing, degradation, and ultimately dysfunction [3, 4].

On the other hand, increasing evidence points to a beneficial function of ROS, the production and elimination of which is tightly regulated (Fig. 19.1). Maintaining a physiological level of oxidative state, recently termed oxidative eustress [5, 6], is essential for supporting normal cellular processes through redox signaling, in which ROS (especially H2O2) serve as important signaling molecules participating in cellular proliferation, differentiation, survival, circadian rhythm, and immune response, just to list a few. One well-established mechanism of redox signaling involves H2O2-mediated oxidation of protein Cys thiols [7]. Certain Cys-SH often residing in the deprotonated form thiolate anion (Cys-S−) can be oxidized by H2O2 and other oxidants to sulfenic acid (Cys-SOH). This oxidation event leads to inhibition of enzymatic activity when the thiol serves a catalytic function, or structural changes and regulation of protein function, affecting cellular epigenetics, signaling, and metabolism [8, 9]. Structural changes are induced, in particular, when a neighboring thiol or amine reacts with Cys-SOH to form an intramolecular or intermolecular disulfide or sulfenyl amide species [10–13] (Fig. 19.2). These reaction products are reversible and represent a mechanism of posttranslational modification analogous to protein phosphorylation. Other oxidized protein species involving Cys residues are formed as well including some that are irreversible. In general, further oxidation of Cys-SOH by H2O2 produces Cys oxoforms sulfinic (Cy-SO2H) or sulfonic acid (Cys-SO3H) and breaks the redox switch [14]. However, specialized enzymatic systems exist to reverse these oxidative modifications such as in the case of peroxiredoxins (PRXs) and a selected number of other proteins, which are repaired by sulfiredoxin [15–17].

Fig. 19.2.

Protein oxidation involving reactive cysteine residues. Specific protein cysteine residues can be oxidized to a variety of oxidized species through the sulfenic acid state

19.1.2. Key Antioxidant Systems

From bacteria, archaea to eukaryotes, organisms have evolved batteries of antioxidant systems to combat the deleterious effects of oxidants. These antioxidants can be divided into two categories based on their activity: enzymatic and non-enzymatic, with the former providing the major defense against oxidants in mammalian systems [18]. As mentioned before, O2·− elimination is primarily provided by SODs, which convert O2·− to H2O2 and O2. Decomposition of H2O2 is accomplished by catalase (CAT), PRXs, and glutathione peroxidases (GPXs), each with different catalytic mechanism of action. CAT contains a heme group in its active site which serves as an electron donor and acceptor in a two-step process of converting H2O2 to H2O and O2 [19, 20]. PRXs are a family of thiol-dependent peroxidases and are considered the ideal H2O2 scavengers given their abundant expression, broad subcellular localization, and fast rate constants towards H2O2 [21, 22]. PRXs reduce H2O2, peroxynitrite, and lipid peroxides at the expense of oxidizing their active site Cys residue, which is subsequently reduced by various systems depending on the specific class of PRXs. For example, PRX1–4 isoforms (typical 2-Cys class) and PRX5 (atypical 2-Cys class) utilize thioredoxins (TRXs) to complete the catalytic cycle. Oxidized TRXs are then restored to their reduced form by thioredoxin reductase (TR) in an NADPH-dependent reaction [23]. Analogous to PRXs, GPXs can also convert H2O2 to H2O in a redox cycle, in which the active site selenocysteine is first oxidized by H2O2 and then reduced by glutathione (GSH). Oxidized GSH (GSSG) is reversed back to GSH by glutathione reductase (GR) using reducing equivalents from NADPH [24]. In addition to GSH, non-enzymatic low molecular weight antioxidants include several vitamins such as ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and tocopherols (vitamin E), and plant flavonoids. They are particularly important for removing oxidants like singlet oxygen (1O2) and ·OH, for which there are no enzymatic mechanisms of elimination.

19.2. Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Small Molecule Redox Biomarkers

19.2.1. Biological and Clinical Significance

Given the critical function and potential detrimental effect of ROS, it is not surprising that many diseases have roots in oxidative stress [25]. However, despite abundant evidence implicating ROS in pathogenesis, most clinical trials have failed to demonstrate health benefits of antioxidant supplements [26–33]. While many argue that better antioxidants, biomarkers, or analytical methodologies are needed [34], this conundrum underscores that oxidative stress-induced damage is not limited to macromolecular damage, but is mediated through disruption of redox signaling, which can occur without impacting the global balance of oxidants and antioxidants. Another explanation could be that, just as genomic sequencing in precision medicine is used to better inform selection of therapies and predict outcomes, redox profiling is needed to identify individuals who may benefit from antioxidant interventions and to aid in the selection of the antioxidants to best compensate for the specific redox deficiency. There is no shortage of research on a wide variety of assays to characterize oxidative stress, and yet consensus is not reached as to which is the most suitable for routine clinical assessment. Of note, most of these assays focus on the end products of oxidation, rather than probing the mechanisms leading to the imbalance of oxidants and antioxidants. The following sections discuss how MS is being applied to measure several redox-relevant small molecules and their value as biomarkers of oxidative stress.

19.2.2. GSH/GSSG and Cys/CySS Redox Couples

19.2.2.1. GSH/GSSG

GSH, a tripeptide consisting of Cys, glutamic acid, and glycine, is the major low molecular weight antioxidant in cells, cycling between the reduced and oxidized forms to donate reducing equivalents for cellular defense against oxidants. Other important physiological functions of GSH include cell signaling, cell cycle control, detoxification of xenobiotics, regulation of metal homeostasis, and participation as a coenzyme in metabolic reactions. A low GSH level, high GSSG level, or a low GSH/GSSG ratio are often indicative of oxidative stress and found in a variety of diseases. For example, GSH/GSSG ratio becomes progressively lower in association with age and diabetes [35, 36] and is an independent predictor for the presence of early atherosclerosis [37]. Many analytical methods to detect GSH and GSSG rely on spectrophotometry utilizing the GSH cycling assay [38], imaging using genetically encoded probes like roGFP2-Grx1 [39], or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) followed by UV, fluorescence, or electrochemical detection. In recent years, MS coupled with either gas chromatography (GC) or liquid chromatography (LC) has become increasingly popular for the analysis of GSH and GSSG, with the advantage of superior sensitivity and selectivity.

Regardless of the method used, substantial differences exist in the reported values of GSH and GSSG, even in control groups of healthy participants [34, 40]. The cause of this problem can be at least threefold. First, most GSH is present intracellularly (e.g., erythrocytes) in the range of 1–10 mM; only a small fraction ranging from 2 to 20 μM is in extracellular matrices (e.g., plasma, serum) [41]. Therefore, it is highly critical to avoid hemolysis during processing of blood specimens; even minor hemolysis can result in a dramatic increase in GSH and GSSG plasma values [42, 43]. If measurements are performed in whole blood, hematocrit levels should be taken into account as this may change dramatically with diseases, which many studies fail to do. There is, in fact, no agreement on which biological matrix should be assayed to best connect GSH and GSSG changes to disease. For humans, blood is one of the better choices because of its less invasive nature. By narrowing GSH measurements specifically to erythrocytes, it was possible to decrease deviation between samples while still showing a change in levels correlated to age [36]. On the other hand, because plasma interacts with the whole body, plasma measurement represents a systemic oxidative stress indicator and may not reflect local effects in specific tissues [44].

Second, since most GSH present in tissues is in the reduced form (i.e., the ratio of GSH/GSSG is high (~400) [38]), artifactual GSH oxidation during sample processing can lead to marked overestimation of GSSG. Thiol alkylating agents such as N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), iodoacetic acid (IAA), 2-vinylpyridine, and monobromobimane (mBB) have been used to prevent artifactual GSH oxidation. Derivatization with alkylating agents not only stabilizes GSH and prevents its oxidation to GSSG or reaction with cystine (CySS), albumin-S-S-Cys, or other disulfides [45], but in some cases (e.g., mBB) also forms a fluorescent product and improves the sensitivity of detection. Among different thiol alkylating agents NEM has been proven the best so far because of its fast reaction and cell permeability, the latter important for measurements in intact cells [40, 41, 46, 47]. The rapid reaction of NEM with –SH also means that NEM is a potent inhibitor of GR. While this is problematic for GSH cycling assays, which rely on GR activity, it is advantageous to use NEM to mask GSH for HPLC-based methods because it inhibits GR catalyzing GSSG conversion back to GSH [47]. In addition, reaction with NEM improves ionization efficiency of GSH for MS detection [48]. Alternatively, artifactual GSH oxidation can also be prevented by acidification, based on the notion that the –SH group is less reactive than its ionized thiolate form –S−. Acidification also serves to precipitate proteins before HPLC analysis. Typical acids used for deproteinization include 5-sulfosalicylic (SSA), perchloric acid (PCA), and trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Unfortunately, no consensus has been reached as to the optimal way to prevent artifactual GSH oxidation. Some argue that derivatization with NEM should be performed immediately after blood collection, followed by a separate acid deproteinization step; addition of NEM together with acid or after acid deproteinization is erroneous because NEM is less reactive with GSH at acidic pH and GSH can be oxidized by acidification if not alkylated [41, 47, 49]. Others argue that acidification does not induce GSH oxidation but rather stabilizes it, or NEM reacts with GSH better at acidic pH, and therefore derivatization is not needed or can be combined with acidification to simplify sample processing [50–53].

Third, the deproteinization step for HPLC analysis can introduce errors, and there is no agreement on the best way to remove proteins. Among commonly used acids for deproteinization, SSA does not achieve acceptable sample stability, TCA interferes with the chromatographic separation of species of interest, and there are concerns of poor reproducibility and sensitivity with PCA methods [54, 55]. Organic solvents such as methanol and acetonitrile have also been used for protein removal [54]. However, the use of either acid or organic methods could also deplete glutathione species by co-precipitation with proteins leading to underestimation of GSH and GSSG. Ultrafiltration was proposed as an alternative method of deproteinization, in particular for matrices such as plasma [46].

Table 19.1 summarizes studies using LC-MS to quantify GSH and GSSG in biological matrices from human, mouse, or rat since 2000. It highlights that, as mentioned above, different methodologies regarding derivatization and deproteinization of samples have been applied for GSH and GSSG quantification, and as a result, the reported values, even for untreated healthy samples, are widely variable and likely plagued by artifacts. The Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) should be utilized as a point of reference for the typical values of GSH in human biospecimens under normal and pathological states [56].

Table 19.1.

Determination of GSH and GSSG by LC-MS

| Matrix | Derivatization | Deproteinization | Detection | GSH | GSSG | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human blood | NEM | SSA, together with derivatization | LC-MS | 1310 μM | 0.62 μM | Steghens et al. [51] |

| Human blood | None | TCA | LC-MS/MS | 865.5 μM | 80.7 μM | Squellerio et al. [52] |

| Human blood | NEM | SSA, together with derivatization | LC-MS/MS | 900 μM | 1.17 μM | Moore et al. [66] |

| Human erythrocytes, plasma | IAM, IPCF | PCA, after derivatization | LC-MS/MS | Erythrocytes, 9.51 μmol/g Hb; plasma, 3.35 μM | Erythrocytes, 0.014 μmol/g Hb; plasma, 0.05 μM | Suh et al. [67] |

| Human erythrocytes | IAA | PCA, before derivatization | LC-MS/MS | 1.33–2.21 mM | 0.168–0.313 mM | Reinbold et al. [68] |

| Human blood, erythrocytes, saliva | NEM | Acetonitrile, after derivatization | LC-MS/MS | Blood, 1.46 μmol/g; erythrocytes, 1.69 μmol/g; saliva, 0.78 nmol/g | Blood, 2.4 nmol/g; erythrocytes, 6.1 nmol/g; saliva, 0.34 nmol/g | Fahrenholz et al. [69] |

| Human neutrophils, erythrocytes, HUVEC | NEM | Ethanol, after derivatization | LC-MS/MS | Neutrophils, 1569 pmol/106 cells; erythrocytes, 1549 pmol/107 cells; HUVEC, 1687 pmol/1.2 × 105 cells | Neutrophils, 1.1 pmol/106 cells; erythrocytes 0.8 pmol/107 cells; HUVEC, 1.9 pmol/1.2 × 105 cells | Harwood et al. [70] |

| Human plasma | NEM | Ultrafiltration with a 10 kDa cut-off, after derivatization | LC-MS/MS | 3.89 μM | 7.09 nM | Sutton et al. [46] |

| Human plasma | None | Methanol | LC-MS/MS | 2.94 μM | ND | Jiang et al. [71] |

| Human PBMC | NEM | Acetonitrile, after derivatization | LC-MS | 74.4 nmol/mg protein | 0.9 nmol/mg protein | Camera et al. [72] |

| Human urine | BQB, acidified | Acetonitrile, before derivatization | LC-MS/MS | 0.0566 mmol/mol creatine | 0.102 mmol/mol creatine | Huang et al. [53] |

| Human urine | FEMA, FEM, acidified | None | LC-MS/MS | 0.0175 mmol/mol | 0.184 mmol/mol creatine | Seiwert et al. [73] |

| Human dermis | None | Microdialysis | LC-MS | 50–60 ng/mL | 3.2–3.4 ng/mL | Robin et al. [74] |

| Mouse blood | NEM | SSA, after derivatization | LC-MS/MS | 805.5 μM | 4.8 μM | Lee et al. [49] |

| Mouse serum | NBenzM, NCycloM | SSA, after derivatization | LC-MS | 241.7 μM | 43.1 μM | Iwasaki et al. [75] |

| Mouse liver | IAA | SSA, after derivatization | LC-MS/MS | 53 nmol/mg protein | 3.7 nmol/mg protein | Bouligand et al. [76] |

| Mouse liver | None | Methanol | LC-MS/MS | 2.17 μmol/g tissue | ND | Norris et al. [77] |

| Rat liver, mouse lymphoma cells | None | TCA | LC-MS/MS | Rat liver, 1.51 mg/g tissue; mouse lymphoma cells, 13,273 ng/107 cells | ND | Zhang et al. [78] |

| Rat hepatocytes | IAA | Acetonitrile, after derivatization | LC-MS/MS | 50–60 μM | 0.6 μM | Loughlin et al. [79] |

| Rat plasma, erythrocytes, lung, liver, heart, kidney, brain | Ellman’s reagent | SSA, after derivatization | LC-MS | Brain, 950; plasma, 20; heart, 1346; lung, 1388; liver 7940; erythrocytes, 2338; kidney, 110 nmol/g or mL tissue | Brain, 11; plasma, 8; heart, 34; lung, 31; liver 348; erythrocytes, 18; kidney, 12 nmol/g or mL tissue | Guan et al. [80] |

BQB bromoacetonylquinolinium bromide, FEM N-(2-ferroceneethyl)maleimide, FMEA ferrocenecarboxylic acid (2-maleimidoyl)ethylamide, HUVEC human umbilical vein endothelial cells, IAA iodoacetic acid, IAM iodoacetamide, IPCF isopropylchlroformate, Hb hemoglobin, LC liquid chromatography, MS mass spectrometry, NBenzM N-benzylmaleimide, NCycloM N-cyclohexylmaleimide, ND not determined, NEM N-ethylmaleimide, PBMC peripheral blood mononuclear cells, PCA perchloric acid, SSA 5-sulfosalicylic acid, TCA trichloroacetic acid

The use of MS in measuring GSH and GSSG is not limited to LC-MS techniques. Although less common, MS has also been coupled with GC [57–62] and capillary electrophoresis [48, 63] to measure GSH. In particular, GSH determination by GC is challenging due to the lack of volatility and thermal stability. Early attempts involved derivatizing GSH or isotopically labeled GSH to generate an N,S-ethoxycarbonylmethyl ester, which was then used to quantify the concentration of GSH and to measure the synthesis rate, respectively, by GC-MS [59–62]. More recently, GSH was also measured as the dimethyl ester-N-pentafluoropropionyl derivative using the electron-capture negative-ion chemical ionization mode in GC-MS [57]. Furthermore, MS/MS without any chromatographic separation was applied to diagnose glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (manifested by lower blood levels of GSH and lower GSH/GSSG) in newborns using dry-blood-spot samples [64]. Quantitative MS imaging has also been used to obtain absolute concentrations of GSH in healthy and cancerous hen ovarian tissues. The results were compared with LC-MS/MS quantification of GSH from the same tissues. While the absolute values differed between these two techniques, there was a consistent approximately twofold increase in GSH concentration in the cancerous tissue [65].

19.2.2.2. Cys/CySS

Cys/CySS is another redox couple commonly measured to assess oxidative stress. Cys-SH is present at low micromolar levels in cells and approximately tenfold higher concentrations in blood (~200 μM) [56]. A nonessential amino acid, Cys is synthesized from homocysteine (Hcy), an intermediate in the Met cycle, via the transsulfuration pathway catalyzed by cystathionine-β-synthase and cystathionine-γ-lyase. The main fate of Cys is incorporation into either proteins or GSH, but it also serves as a source of H2S in cells [81]. H2S reaction with protein Cys-SOH or disulfides leads to the formation of protein Cys-S(S)nH per-/polysulfides [82]. Cys is found in most proteins and often positioned in the functional sites of proteins subject to redox regulation [83, 84]. Cys is the rate-limiting substrate for de novo GSH synthesis, which relies on the enzymatic activity of glutamate cysteine ligase and GSH synthase. When free Cys is oxidized, it forms CySS. While plasma total Cys is a risk factor for atherosclerosis [85, 86], increased CySS in plasma is associated with age, obesity, smoking, alcohol abuse, and multiple disease processes [87, 88]. Cys/CySS is the most abundant low molecular weight thiol/disulfide couple in human plasma, both present in ~10–100-fold higher concentrations than GSH and GSSG [87]. There is a lack of thermodynamic equilibrium between the GSH/GSSG and Cys/CySS redox couples, both intracellularly and extracellularly [88]. In both compartments, the Cys/CySS redox couple is maintained at a more oxidized state than GSH/GSSG [44]. Similar to GSH/GSSG, the Cys/CySS redox couple is oxidized in association with age, albeit with a different rate [35]. A novel plasma CySS/GSH ratio can predict death as an outcome in coronary artery disease patients [89]. In this interpretation, CySS provides a surrogate for overall oxidative burden and GSH provides a surrogate for the NADPH-dependent reductive capacity.

Determination of Cys and CySS suffers from the same issues as mentioned before for GSH and GSSG. Although the differences between intracellular and extracellular Cys levels as well as between Cys and CySS are less dramatic than for the GSH/GSSG redox couple, stabilizing the –SH group with a derivatizing agent remains necessary to avoid artifacts. After derivatization, Cys and CySS can be measured by LC-MS [46, 67, 75, 76, 80, 90, 91]. Alternatively, total Cys (Cys-SH + CysSS) can be measured by LC-MS [71, 92, 93] or GC-MS [59, 60, 94] after reducing the samples with dithiothreitol (DTT) or tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP). Because MS can potentially differentiate a multitude of analytes, measurement of Cys and CySS is often accomplished simultaneously with other thiol metabolites (e.g., GSH, GSSG, Hcy, homocystine, etc.), or sometimes even in a broader metabolomics setting though most often without the necessary precautions to avoid artifacts [46, 48, 95, 96].

19.2.3. NAD(P)H and NAD(P)+Redox Cofactors

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+), and their reduced forms (NADH and NADPH) are essential redox cofactors. Although structurally identical except for the additional 2′ phosphate on the adenosine ribose moieties of NADP+ and NADPH, the functions of NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH are not redundant. While NAD+/NADH participates in catabolic reactions (e.g., glycolysis, citric acid cycle, fatty acid oxidation), NADP+/NADPH supports reductive biosynthesis. In addition to its redox functions, NAD+ is also substrate for poly ADP-ribose polymerases, cyclic ADP-ribose synthases, mono ADP-ribose transferases, and sirtuins [97–100]. Over a century of comprehensive research has expanded the functions of NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H from energy metabolism to calcium homeostasis, gene expression, immune response, cell death, detoxification, and so forth [100]. Of particular interest, NADPH has opposing functions with regard to ROS generation and elimination. On the one hand, NADPH provides the reducing equivalents to regenerate reduced TRXs and GSH via the TR and GR systems, respectively [23, 24], and reactivate CAT [101], all of which are essential for degradation of H2O2 and reduction of many oxidized species. On the other hand, NADPH contributes to ROS generation through the activity of NADPH oxidases in phagocytes and various tissues and cell types [102, 103]. The ratio of NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H determines the redox potential that can affect the activities of numerous metabolic pathways. Consequently, altered levels and ratios of NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H are implicated in disease conditions such as diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancers, and these redox couples have been intensively investigated as therapeutic targets for these diseases [99, 100, 104–106]. Therefore, determining the levels and ratios of NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H serves as a powerful tool to assess cellular metabolic and redox state.

Measurement of NAD(P)H and NAD(P)+ has been achieved by autofluorescence [107], genetically encoded fluorescent sensors [108, 109], nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy [110, 111], HPLC with UV or fluorescence detection [112–116], and enzymatic cycling assays with colorimetric, fluorescent, or luminescent detection [117–120] offered by many commercially available kits. Since LC-MS has become the leading analytical technology in untargeted metabolomics and targeted analysis, this technology has been increasingly applied for quantitation of NAD(P)H and NAD(P)+. Typically, the measurement starts with quick quenching of metabolism to avoid artifacts caused by residual enzymatic activities, which can be done by freezing in liquid nitrogen or mixing with cold organic solvents [121]. Metabolites are then extracted, usually in some mixture of water, ethanol, methanol, or acetonitrile, but typically for cells and tissues 40:40:20 acetonitrile:methanol:water with 0.1 M formic acid [122]. Next, ion pair reversed-phase LC (IP-RP-LC) or hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) is used for separation followed by electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS or -MS/MS usually operating in negative ion mode. Because NAD(P)H and NAD(P)+ are often measured in metabolomics studies, different LC conditions have been tested to achieve the best resolution and data quality. The consensus has been that IP-RP-LC provides superior retention and separation of the targeted compounds, compared to HILIC or other chromatography methods [123, 124].

Accurate measurement of NAD(P)H and NAD(P)+ is still challenging, as manifested by large discrepancies between reported values. Such difficulties can be attributed mainly to the labile nature of these chemicals, especially for NADH and NADPH, which are not stable at low pH and high temperature [125, 126]. Similar to the measurements of cysteine and glutathione redox couples, it would be recommended to have dedicated methods for NAD(P)H and NAD(P)+ quantitation, instead of just extracting the data from broad metabolomics studies. Moreover, most MS studies to analyze NAD(P)H and NAD(P)+ used bacteria [123, 124, 127–133], yeasts [130, 132, 134–137], mammalian cultured cells [122, 124, 129, 132, 135, 138–142], rat kidney [143], mouse liver [122, 130], heart [144], pancreas [124], erythrocytes [140], and brain [141] samples, and only a few studies report measurements in human blood and urine [124, 141, 144, 145]. It is desirable to develop methods using matrices that are applicable to routine clinical assessment. Indeed, new promising approaches are emerging such as using magnetic resonance to monitor NAD+/NADH redox state live in the human brain, providing innovative means to examine this redox couple non-invasively [146].

19.2.4. 8-Isoprostane

Isoprostanes are a large family of prostaglandin-like compounds generated by free radical-mediated oxidation of arachidonic acid (AA) and other polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) without the direct action of cyclooxygenases [147, 148]. 8-isoprostane (also known as 15-F2t-isoprostane or 8-iso-PGF2α) has been widely used as a proxy for all general isoprostanes. Historically this is due to the availability of an authentic standard, but subsequent extensive research has established its value as a biomarker of oxidative stress in a wide variety of disease conditions [149–154]. Esterified isoprostanes compromise membrane integrity and fluidity, and cleaved free 8-isoprostane, and some other isoprostanes can exert robust biological activities by acting as ligands for prostaglandin receptors, extending their function as signaling mediators in oxidative stress-related diseases [155, 156]. As a biomarker of oxidative stress, 8-isoprostane has several advantages: 1) it is chemically stable, 2) it is present in a detectable amount, 3) it is produced specifically by free radical-mediated oxidation, and 4) it is not affected by lipid content of a diet [153]. 8-isoprostane has been measured in various bodily fluids including serum, plasma, urine, bile, exhaled breath condensate, amniotic fluid, bronchioalveolar lavage fluid, cerebral spinal fluid, and sputum where is generally found at sub-nanomolar concentrations [56]. Among these, urine is the preferable biospecimen for 8-isoprostane detection because it is non-invasive and there is no artifactual generation of 8-isoprostane by oxidation as found in serum or plasma [153, 157].

It should be noted that although 8-isoprostane was thought to be generated solely by free radical-mediated AA peroxidation, this idea has been challenged by identification of an alternative reaction catalyzed by prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase (PTGS) [158–160]. This means that an increase in 8-isoprostane level does not necessarily indicate oxidative stress, especially during inflammation when PTGS is known to be induced. However, because esterified AA, the predominant form of AA, is not a substrate for PTSG, esterified or total 8-isoprostane should not be significantly impacted by PTGS-mediated 8-isoprostane formation and therefore represent oxidative stress [151]. In addition, one can also measure the 8-isoprostane/prostaglandin F2α ratio to distinguish chemical from enzymatic lipid peroxidation [161].

Typically, 8-isoprostane quantitation is performed by immunoassays or MS-based assays with GC or LC. Immunoassays include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [162] and radioimmunoassay [163]. These are easy to perform and do not require expensive instrumentation but often suffer from cross-reactivity with related compounds, leading to overestimation of 8-isoprostane [164–166]. GC-MS methods offer excellent sensitivity and specificity, but laborious sample preparation including derivatization is needed. A typical procedure requires solid-phase extraction (SPE) using a C18 column, thin-layer chromatography (TLC) purification, and chemical derivatization with pentafluorobenzyl bromide. Quantitation is achieved by using GC-negative ion chemical ionization-MS and employing stable isotope dilution [167–169]. Many variations have been made to improve the assay by simplifying the sample purification steps [170–175] and by using MS/MS for more specific detection [173, 176–178]. LC-MS is an attractive alternative to GC-MS because LC resolves more of the isoprostane isomers than GC [179–181] and does not need derivatization. A typical procedure employs SPE for sample preparation followed by LC-MS with ESI [179, 182–190]. Immunoaffinity chromatography purification has been shown to help distinguish 8-isoprostane from its three isomers for both GC and LC, thus allowing more specific measurements [178, 191–193].

19.2.5. ROS Measurement with 2-Hydroethidium

ROS are highly reactive and short-lived (e.g., O2·− has a half-life of 1–4 μs, ·OH 1 ns, and H2O2 has the longest half-life of the three - more than 1 ms [194]). Thus, ROS exist in vivo at very low concentrations (picomolar to low nanomolar) [195], and direct measurement of ROS is virtually impossible. This has led to the development of many ROS probes, which react with these species and form relatively stable products that are easily detectable (reviewed in [196]). However, many commonly used ROS probes suffer from nonspecific reactions with multiple species, making results difficult to interpret. For instance, hydroethidine (HE; or dihydroethidium) and its mitochondria-targeted analog mito-HE (commercially known as MitoSOX) have been widely used as intracellular and mitochondrial O2 ·− probes, respectively. Although O2·− can oxidize HE or mito-HE to specific products 2-hydroxyethidium (2-OH-E+) or 2-OH-mito-E+, other oxidants lead to ethidium (E+) or mito-E+ species [197]. Because the fluorescent spectra of these products overlap, it is not advisable to use simple fluorescence detection to accurately measure O2·− [197]. On the contrary, HPLC with UV, fluorescence, electrochemical, or MS detection offers great selectivity in detecting and quantifying 2-OH-E+, E+, and their mitochondrial analogs [197, 198]. Recently, by using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) with LC-MS/MS, simultaneous monitoring of HE, mito-HE, and hydropropidine (HPr+, a newly developed extracellular O2·− probe), and their oxidation products was achieved in a cell system [199].

19.3. Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Proteins Oxidation

19.3.1. Biological and Clinical Significance

Collectively, there are >35 oxidative posttranslational modifications in proteins, all of which can be distinguished by MS [200]. The most redox susceptible amino acid in proteins is the sulfur-containing Cys, which can be oxidized to a variety of products as shown in Fig. 19.2. Other amino acids can also be oxidized including Met (Met-O, Met-O2), Tyr (Tyr-OH, Tyr-NO2), and proline (Pro-OH) impacting protein stability and function [201] and leading to disease [202–205]. This section summarizes modern proteomics approaches, especially MS-based proteomics, for detection and quantification of reversible oxidative modifications at protein cysteine sites.

19.3.2. Analysis of Redox Modifications in Intact Proteins by Mass Spectrometry

Intact protein analysis by MS is used for studies of enzyme kinetics, to monitor the formation of various oxoforms, structural investigations, and many other applications. While both matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS) and ESI-MS have been used for this purpose (most frequently with time-of-flight (TOF) analyzers), ESI-MS is the more common method. For kinetic studies, an online or offline reaction quenching step is required as it has been shown in several studies [206–208]. Monitoring thiol oxoforms such as -SOH, nitrosylation (-SNO), glutathionylation (-SSG) and others is of high interest in the field of redox biology. Numerous studies have used ESI-MS with online and offline quenching to monitor thiolbased enzyme kinetics in PRXs and other enzymes [15, 209]. Other studies have used proteins containing reactive Cys in investigations aimed at gaining knowledge of the mechanisms of oxidation and relay of oxidative signals, and for development of chemical reagents with selective reactivity towards a specific thiol oxoform. While these studies often used wild-type enzymes, in several cases mutagenesis was applied to stabilize or enrich in certain oxidative modifications (e.g., AhpC (alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C) [210, 211], bovine seminal ribonuclease [212], and OhrR repressor [213]). For example, the bacterial S. typhimurium PRX AhpC was used in several studies either as the wild-type (-SH and disulfide-linked dimer) or with the resolving Cys165 mutated to alanine or serine to stabilize the -SH and generate -SOH, -SSH, -SNO, -SSG and other oxidative species. These were then employed : 1) to discover the cross-reactivity of commonly used thiol-blocking reagents such as IAM, NEM, and methyl ethanethiosulfonate (MMTS) with protein Cys-SOH [214]; 2) to screen for and identify a new class of biologically compatible thiol-selective reagents, leading to the discovery of MSTP (4-(5-methanesulfonyl-[1,2,3,4]tetrazol-1-yl)-phenol) as a thiol-selective, highly reactive, cell membrane permeable and MS-compatible thiol blocker [215]; and, 3) to characterize the kinetics and selectivity of new chemical probes with a given oxidative modification (e.g., protein sulfenylation probes DCP-Bio1, BP1, Alk-β-KE, and mitochondria-targeted DCP-NEt2C [216–220], and protein sulfenylation and persulfidation probe BCN/BCN-Bio1 [221]). Direct analysis of persulfides (-SSH) and other thiol modifications using ESI-MS was also performed with other intact proteins [222].

19.3.3. Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches for Identification of Protein Oxidation at Cys Residues

In general, the MS analysis of proteins and posttranslational modifications can essentially be divided into “top-down” and “bottom-up” approaches. For top-down proteomics, fragmentation of intact proteins occurs within the mass spectrometer. For bottom-up analysis, proteins are proteolytically digested to peptides before being introduced into the MS.

Most top-down studies are performed using recombinant low molecular weight proteins. However, this approach can also be applied to investigate redox modifications of abundant proteins in a biological matrix of interest [223]. Examples of top-down studies of protein oxidation include identification and quantification of blood cysteinylated human serum albumin (-SSCys), nitrosylated hemoglobin A (-SNO), and Met-oxidized apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) for assessment of redox state linked to the risk of cardiovascular diseases [224], identification and monitoring of reactive Cys residues in the tumor suppressor protein p53 [225], and characterization of oxidized calmodulin in activated macrophages [223]. However, despite these reports, the methodology has limitations for the broad detection of protein oxidation in biological systems.

Over the years, a number of bottom-up methods were developed to enable broad scale identification and quantification of protein oxidative modifications. Though typically the proteolytic digestion is performed with trypsin, alternative proteases with orthogonal activities to trypsin have been successfully applied, including chymotrypsin, Asp-N, and Glu-C [201]. These are in particular valuable as oxidative modifications may interfere with the binding and enzymatic activity of any single protease. Bottom-up proteomics analysis is most commonly conducted by LC-MS/MS using either untargeted approaches or targeted analysis. Because the level of oxidative modifications in complex samples is relatively low (<5%), special methods for labeling of oxidized proteins and enrichment strategies are employed, as described below. A key aspect of the analysis is also the handling of biological or clinical specimens to limit protein oxidation artifacts during processing, which will be discussed in Sect. 19.3.4.

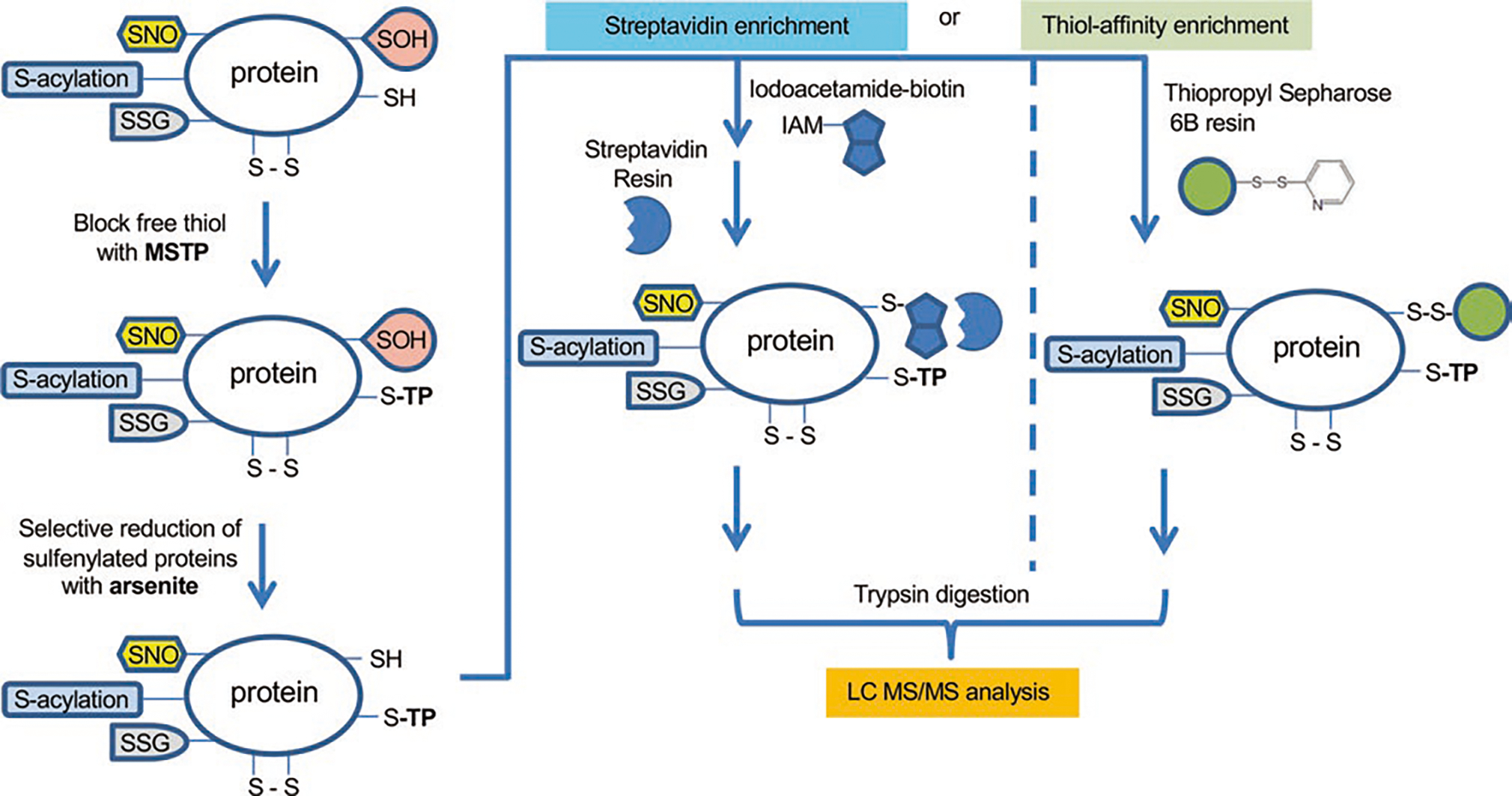

19.3.3.1. Indirect Tag-Switch Methods

The biotin-switch is the most commonly used tag-switch method in redox proteomics. Since its introduction, many modifications have been made that allow for more efficient sample enrichment and interface with MS analysis [226]. This method relies on selective blocking of free thiols, selective or non-selective reduction of particular oxidative modification(s), and labeling of nascent reduced thiols with a biotin-tagged thiol alkylating compound followed by enrichment with streptavidin beads, or direct enrichment of nascent thiol proteins by binding to thiol sepharose or comparable resins. Using this general workflow, the oxidation state of a specific protein can be detected, proteins of a particular oxidation state can be enriched, and changes in protein oxidation can be quantitatively analyzed with MS and further validated with Western blot analysis [214].

Protein Sulfenylation (-SOH).

Figure 19.3 shows the indirect tag-switch method for analysis of protein sulfenylation by MS. Traditionally, IAM, NEM, or MMTS are used for the initial alkylation of reduced thiols; however, these react with both –SH and –SOH cysteine species in proteins and are therefore unsuitable for –SOH determination with this method. Moving forward, it is recommended that reduced thiols are blocked by MSTP, a selective reagent mentioned earlier [215]. Subsequently, –SOH is reduced back to –SH selectively with sodium arsenite [227], followed by labeling of newly generated reduced thiols with biotin-IAM and streptavidin-based enrichment. Alternatively, direct enrichment of newly reduced proteins with thiopropyl sepharose 6B resin [228] could be used to bypass biotin labeling. After the enrichment, proteolytic digestion is performed to generate peptides, followed by the release of tagged or bound Cyscontaining peptides. LC-MS/MS analysis can be used to identify the site of modification, to quantify the site occupancy, and to perform relative quantification of changes in oxidation levels between conditions. This workflow can be adapted to identify and quantify other oxidative modifications by simply switching the conditions for selective reduction of oxidized species as described below.

Fig. 19.3.

Indirect tag-switch method for analysis of protein sulfenylation by MS

Protein Nitrosylation (-SNO).

Ascorbate is widely used to selectively reduce –SNO in the indirect tag-switch method [229, 230]. However, this method is questionable as ascorbate is also known to reduce disulfide bonds and –SOH, thus generating false-positive identifications of –SNO species. The choice of thiol blockers and reductant, as well as other workflow parameters, need to be carefully considered for analysis of this oxidative modification [214].

Protein Glutathionylation (-SSG).

Indirect techniques for analysis of this modification involve the enzymatic and selective release of GSH from glutathionylated proteins with GRX. Several concerns have been raised with this approach as well, such as incomplete reduction and alkylation impacting quantification, issues related to the specificity of bacterial GRX for human glutathionylated proteins, and possible oxidation of newly generated protein thiols during processing. To limit these caveats, alternative methods using biotinylated GSH have been developed, but the concern here is that the bulky biotin tag on the GSH molecule might disturb the function of proteins interacting with GSH and overall redox state of the cell [231]. Nevertheless, identification and quantification of protein –SSG was performed in various biological contexts, including in mouse macrophages treated with diamide (tetramethylazodicarboxamide), a reagent inducing disulfide bond formation in proteins [232].

Global Reversible Oxidation.

Thiol affinity resin-assisted enrichment methods have become standard for profiling total reversible oxidative modifications at protein Cys residues. In general, DTT is applied as a strong reductant to switch all reversible oxidation states back to reduced thiols, followed by enrichment with either biotin-labeling/streptavidin or directly thiol affinity resins like the thiopropyl sepharose described above. A variety of quantitative approaches can be incorporated into the workflows for analysis of oxidative modifications as described in Sect. 19.3.3.4.

19.3.3.2. Direct Methods Using Selective Labeling of Oxidative Modifications

Direct methods rely on the selective reaction of a chemical probe (often biotin-tagged or containing click-ready alkyne or azide tags) with a particular oxidative modification. Compared with the indirect biotin-switch methods, this approach has fewer processing steps, leading to shorter processing time and limited sample loss. Selective chemical probes compatible with MS analysis for labeling of protein –SO2H [233], –SNO [234], and –SOH [216, 218, 219, 235] species have been reported. Another chemical probe BCN-Bio1 can be used to identify and quantify selectively –SOH and –SSH species in the same analysis based on the mass difference in the products of BCN-Bio1 reaction with these species (+16 mass units; –S-BCN-Bio1 for the reaction with protein –SSH versus –S(O)-BCN-Bio1 for the reaction with protein –SOH). Further development of DCP-NEt2C, a fluorescent probe targeting mitochondrial sulfenylated proteins, with biotin or other enrichment tags is expected to enable both imaging and MS analysis of protein sulfenylation [220]. Alternatively, isolation of mitochondria fraction either pre- or post-labeling with chemical probes and other indirect workflows could be used to monitor protein oxidation in this key subcellular organelle [236].

19.3.3.3. Analysis of Redox Interactome

Comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions (interactome) is becoming increasingly critical in biological and clinical studies. Redox-based interactions, such as through covalent disulfides, are critical to the assembly of both transient and stable protein complexes. High-resolution MS combined with sophisticated analysis software is needed to identify intermolecular as well as intramolecular disulfide bonds. Key to sample processing is again blocking of free and protein thiols with alkylating agents to prevent artifacts of thiol-disulfide exchange reactions and scrambling of disulfides. This approach was applied to identify intramolecular disulfides in a number of signaling proteins (e.g., Akt isoforms [237], ERK2 [238], and JNK2 [239]). In a particular study, a mechanism-based kinetic trapping technique was used to identify thiol-disulfide exchange interactions on the surface of lymphocytes [240]. The study discovered a redoxcontrolled interaction of TRX1 with the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 8 (TNFRSF8/CD30). Novel interaction partners of FOXO4 were also identified using a proteome-wide screen of ROS-induced disulfide-bound protein complexes [241]. One of these proteins was the nuclear import receptor transportin-1, and the study showed that disulfide formation between FOXO4 and transportin-1 is required for nuclear localization and the activation of FOXO4/DAF-16 under conditions of increased ROS.

19.3.3.4. Quantitative Methods of Analysis

Accurate quantitative information of oxidative modifications and their relative abundance is critical in redox proteomics analysis of both biological and clinical specimens. Quantitative proteomics strategies can be divided into absolute and relative methods, and the relative methods can be further subdivided into label-free or label-based methods [242]. Label-free analysis of total reversible oxidation in red blood cell membranes found increased binding of oxidized hemoglobin and decreased binding of PRX2 to membranes [243]. Label-based approaches include isotope-coded affinity tag (ICAT), isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ), tandem mass tag (TMT), stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC), or the use of isotope labeled chemical probes (e.g., protein sulfenylation [244]). For example, ICAT was used to investigate the redox mechanisms of RyR1 regulation and the dynamics of disulfide bonds formation [245]. The majority of redox proteomics studies rely on iTRAQ [246–248] or TMT [249, 250] labeling for relative quantification. Though limited to cell culture studies, SILAC has the advantages of straightforward implementation, quantitative accuracy, and reproducibility for redox proteomics research [251, 252].

19.3.4. Prevention of Artifacts in Analysis of Protein Oxidation

Giving the high reactivity of ROS with protein amino acids (e.g., Cys, Met, tryptophan), and the possibility of multiple reactions between reduced and oxidized thiol species scrambling the endogenous redox state of proteins, it is critical that sample processing is performed under conditions that limit these events. For example, processing of biological or clinical specimens typically requires the breakdown of natural barriers that restrict endogenous ROS to certain subcellular compartments leading to artifactual oxidation when these ROS or other reactive species are released and come in contact with proteins that would not otherwise be exposed to these species. This situation is similar in a way to the errors introduced in the analysis of plasma GSH when erythrocytes are accidentally lysed during blood processing (discussed in Sect. 19.2.2.1). As mentioned above, another major source of errors in redox proteomics is the possibility of reactions between reduced and oxidized thiol species including thiol-disulfide exchange reactions, the reaction of sulfenylated species with reduced protein or free thiols to produce disulfides or the reaction of H2S with sulfenylated proteins and disulfides to generate persulfides, and others. Thus, the following considerations are key to preventing or at minimum limiting these artifacts: 1) processing of samples on ice and when available in an anaerobic chamber; 2) supplementing lysis buffers with metal chelators, CAT, SOD, selective chemical reagents to block reduced thiols (e.g., MSTP) and sulfenylated states (e.g., BCN or BCN-Bio1) [Note: non-selective blocking of –SH and –SOH species with IAM, NEM, or MMTS may also be used depending on the scope of the study; e.g., if the study focuses on protein glutathionylation]; and, 3) precipitating proteins as quickly as possible after labeling to prevent further reactions of proteins with either small molecule endogenous species (e.g., GSH or GSSG) or with chemical reagents in lysis buffer.

19.4. Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Lipid Oxidation

19.4.1. Biological and Clinical Significance

In general, lipid oxidation is a process in which the double bonds in PUFAs and other unsaturated lipids react with oxidants such as free radical or non-radical oxidative species produced as a consequence of redox imbalance in biological systems. The process consists of three steps: initiation, propagation, and termination [253] (Fig. 19.4). Once lipid peroxidation is initiated, subsequent propagation steps occur as chain reactions until non-radical compounds are produced at the termination step. During the initiation step, a carboncentered lipid radical is produced by hydrogen abstraction, which can be induced by exogenous physical and chemical reagents or endogenous enzymatic systems including NADPH oxidase, xanthine oxidase, nitric oxide synthase, and cytochrome P450. In the case of lipid peroxidation, a peroxyl radical is produced next by the propagation step in which molecular oxygen reacts with a lipid radical in many lipid oxidation events. Sometimes a hydrogen atom is transferred to form a peroxyl radical. Also, propagation can be achieved by other mechanisms including direct peroxyl radical addition, intramolecular radical substitution on peroxide, and peroxyl radical cyclization. In the termination step, a hydrogen atom is donated from antioxidants to form non-radical products.

Fig. 19.4.

General mechanism of lipid peroxidation

Lipid oxidation and peroxidation has been implicated in the etiology of various diseases including a wide range of metabolic diseases, cardiovascular disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 19.5). Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disease with underlying redox mechanisms of pathogenesis [254]. ROS-induced changes in redox state activate stress-sensitive intracellular signaling pathways which mediate insulin resistance and impair insulin secretion. The role of ROS and RNS in cardiovascular diseases is similarly well-established [255–259]. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is a major target of these reactive species (e.g., ONOO−) generating isoprostanes, oxysterols, lipid peroxides, and aldehydes upon oxidation. LDL oxidation is a crucial mechanism of atherosclerosis causing significant complications in the cardiovascular system [260]. There is also increasing clinical evidence that lipid peroxidation impacts neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Lipid peroxidation products such as MDA, acrolein, 4-HNE, and 4-hydroxy-2-hexenal (4-HHE) were shown to be elevated in diseased brain regions in both early and late stages of AD. Furthermore, higher levels of important lipid peroxidation markers, including F2-isoprostanes, MDA, and protein-bound acrolein adducts, were found in plasma and urine of AD patients [261, 262].

Fig. 19.5.

Lipid peroxidation and human diseases. ROS attack membrane lipids, producing various lipid peroxidation products, which can lead to DNA damage/mutation, protein adduct formation/alteration, and/or initiation of further lipid peroxidation, ultimately resulting in neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, and metabolic diseases

This chapter presents a brief overview of key products of lipid peroxidation and describes current MS-based analytical strategies for selective and sensitive identification and quantification of these species.

19.4.2. Primary and Secondary Lipid Peroxidation Products

19.4.2.1. Primary Lipid Peroxidation Products

The reaction of ROS and other reactive species with lipids can produce a variety of compounds due to the inherent structural diversity of lipids. However, the main primary products of lipid peroxidation are defined in general as lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH). LOOH are generated during the propagation step in which the hydroperoxide moiety is attached to various lipid species including free fatty acids, triacylglycerols, phospholipids, and sterols [263].

Primary peroxidation products are more stable than free radicals which are usually unstable and highly reactive [264]. In moderate conditions such as lower temperature and absence of metal ions, intact LOOH can be measured and used as biomarkers of oxidative stress in blood and tissues [263, 264]. On the other hand, decomposed products from one-electron reduction induce oxidative damage by mediating lipid oxidation to form new sets of LOOH [264, 265]. The lipid peroxyl radical (LOO·) generated from the propagation step can attack other lipids, promoting further peroxidation events. These species target mostly PUFAs such as AA. AA is one of the representative omega-6 PUFAs formed primarily by enzymatic cleavage of membrane phospholipids. Many eicosanoids such as prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes are produced from enzymatic oxidation of AA; cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases, and cytochrome P450 enzymes are responsible for these reactions [263]. Isoprostanes and other end products such as MDA and 4-HNE are generated by non-enzymatic processes catalyzed by free radicals (Fig. 19.6).

Fig. 19.6.

Lipid peroxidation products. Different classes of PUFAs can undergo non-enzymatic or enzymatic oxidation, producing primary and secondary lipid peroxidation products. COX, cyclooxygenase; CYP450, cytochrome p450; EET, epoxyeicosatrienoic acid; HETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; 4-HHE, 4-hydroxy-2-hexenal; 4-HNE, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal; HODE, hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid; LOX, lipoxygenase; MDA, malondialdehyde; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; ROS, reactive oxygen species

19.4.2.2. Secondary Lipid Peroxidation Products

Secondary lipid peroxidation is generally defined as peroxidation processes of AA and other PUFAs that lead to the generation of end products such as MDA and 4-HNE [266]. At high levels, MDA is known to be the most mutagenic lipid peroxidation product whereas 4-HNE is the most cytotoxic product [267]. MDA is produced mainly by non-enzymatic processes and is highly reactive towards proteins and DNA [268, 269]. MDA modifies a wide range of proteins including enzymatic proteins, carrier proteins, cytoskeletal proteins, and mitochondrial and antioxidant proteins. It is suggested that DNA alteration by MDA may play critical roles in the initiation of cancer or other genetic diseases and many efforts are given to define the underlying mechanisms [270]. MDA adducts were also shown to accumulate during aging and in other chronic diseases [271, 272].

Another major secondary lipid peroxidation product is 4-HNE. 4-HNE is an interesting molecule because of its dual functions as a cytoprotective signaling molecule regulating gene expression, and as a cytotoxic molecule inducing pathological abnormalities [266]. During the past decades, 4-HNE and its role as a signaling molecule have been studied in relation to many diseases. 4-HNE is derived from either enzymatic transformation of omega-6 PUFAs by 15-lipoxygenase or several non-enzymatic oxygen radical-dependent routes involving the formation of hydroperoxides, alkoxyl radicals, epoxides, and fatty acyl crosslinking reactions. Once formed 4-HNE plays pivotal roles to promote cell survival or cause cell death depending on the cell type and cellular circumstances. When the level of 4-HNE is low, cellular protective genes such as Nrf2 are expressed which enhances antioxidant capacity. Medium levels of 4-HNE induce autophagy and cellular senescence, while high levels of 4-HNE induce apoptosis and necrosis. These actions are mediated by the reaction of 4-HNE with proteins or DNA [263].

19.4.3. Targeted Analysis of Primary and Secondary Products of Lipid Peroxidation

The major limiting factor for assessment of lipid peroxidation has been the low stability of endoperoxides which decompose in milliseconds to form downstream metabolites. Furthermore, many peroxidation products (e.g., MDA and 4-HNE described above) bind to macromolecules to form various adducts, which becomes a barrier in the quantitative analysis of these species. Over the past decades, the biological function of lipid peroxidation was broadly investigated with a significant effort being placed into the development of analytical methods to measure the levels of key products of lipid peroxidation.

One of the classical methods for analysis of lipid peroxidation is measuring the optical density of a color pigment formed by oxidation of metal or thiobarbituric acid (TBA) using UV-Vis spectroscopy. Among others, thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) assay is employed to measure hydroperoxides which generate a red pigment (λmax 562 nm) with TBA in acidic conditions [273, 274]. This method is widely used for measurement of MDA and 4-HNE originated from the oxidation of cholesteryl ester and phospholipids in biological specimens such as plasma. Another technique is the ferrous oxidation of xylenol (FOX) assay which detects hydroperoxides from peroxidized lipids. Hydroperoxides oxidize Fe2+ to ferric iron (Fe3+) which binds to xylenol orange to form a red colored complex (λmax 560 nm) [275]. Because of the simplicity and low cost of analysis, these colorimetric methods are still widely accepted. They have often been combined with a chromatography system to enhance selectivity and thus to avoid false positive results from interfering substances. It is, however, still challenging to distinguish lipid hydroperoxides selectively from other oxidized biomolecules using TBARS and FOX assays.

A number of analytical methods for the determination of conjugated dienes of lipid hydroperoxides such as hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids (HODEs) and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) have been reported since the 1990s [276]. Those intermediate products are detectable due to their relatively high stability and UV absorbance (λmax 234 nm), which is often limited by interferences with the UV absorbance of other molecules, in particular when biological samples such as plasma are tested.

MS is one of the fastest evolving analytical platforms in this field with many breakthrough technologies in ionization, mass separation, and detection, which ultimately enable high-throughput analyses. Figure 19.6 shows the main products from enzymatic and non-enzymatic oxidation of PUFAs as well as their peroxidation end products, which can be measured by a variety of MS-based analytical methods.

GC separation has been widely used for analyses of isoprostanes and other end products because of its high chromatographic resolution and sensitivity, although the sample preparation process is time-consuming involving both specialized derivatization and extraction steps. Oxidation products originated from phospholipid membranes such as hydroxylated derivatives of linoleic acid (LA), AA, and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) were identified in animal models using GC-MS [277, 278]. Various modified techniques have been developed to measure peroxidation end products [279]. GC-MS is also routinely used for analyses of a variety of lipid molecules including PUFAs, cholesterol, and oxysterols due to its robustness, which in some cases outweighs some of the disadvantages.

LC-MS has become in recent years the most popular platform for analysis of virtually all analytes. LC-MS is widely applied for analysis of proteins, metabolites, pharmaceuticals, and other small molecules including lipids and lipid mediators, which were previously analyzed with GC-MS. This evolution was facilitated by improvements in separation techniques and increased availability of a wide variety of stationary phases with unique chemistry for separation of complex biological extracts. Unlike GC-MS, analysis by LC-MS does not require chemical derivatization to increase volatility. Although many lipid species such as oxysterols and some peroxidation products remain difficult to detect with LC-MS, LC-MS allows for analysis of thousands of lipid molecules from a single chromatographic separation. During the past decade, numerous research papers reported the application of LC-MS for analysis of lipids and lipid oxidation products including saturated fatty acids and PUFAs, 4-HNE and its adducts, glycerolipids, cholesteryl esters, cholesterol, oxysterols, HETEs, isoprostanes, and MDA employing various data acquisition strategies (Fig. 19.7).

Fig. 19.7.

Overview of MS-based lipidomics strategies

In the following sections, we describe several MS methods for analysis of lipid oxidation by focusing on specific classes of compounds.

19.4.3.1. Unsaturated Aldehydes

GC-MS was applied to quantify 4-HNE after chemical derivatization using O-pentafluorobenzyl and trimethylsilyl [280, 281]. This method enhanced the stability and volatility of intact 4-HNE allowing for its measurement in the low ng/mL range in negative ion mode with selected ion monitoring (SIM). This method was applied with slight modifications for quantification of MDA and other 4-hydroxyalkenal species [282, 283].

An LC-MS/MS method was also developed for analysis of HNE enantiomers [284]. This study was a valuable attempt to profile enantiomers because the targets of HNE and the pathways of HNE metabolism are known to be influenced by its stereochemistry [285, 286]. HNE and its metabolites, (S)-HNE-(S)-carbidopa, (R)-HNE-(S)-carbidopa, HNEAcid, GSHNE (GSH adduct), and GSHNEDiol were separated and quantified, which could constitute useful biomarkers of lipid peroxidation in disease.

The cytotoxic effect of 4-HNE is based on its ability to form adducts with essential cellular biomolecules such as GSH, proteins, and DNA. For example, DNA-HNE adducts (Fig. 19.8) are well known to cause mutagenesis and are implicated in cancer development [287]. Michael adducts of 4-HNE with GSH and the endogenous histidine-containing dipeptides carnosine (CAR) and anserine (ANS) were identified in skeletal muscle using IP-LC-ESI-MS/MS with MRM [288]. The limitation of this method is the requirement for a relatively high amount of biological specimens and the need to protect from oxidation artifacts during sample processing.

Fig. 19.8.

Representative DNA oxidation products and adducts with secondary lipid peroxidation metabolites

The reaction of 4-HNE with proteins is also critical to disease development and progression [287, 289–292]. Because of relatively low abundance of protein 4-HNE adducts, various enrichment strategies are used to measure these species by MS. Recently, a large-scale proteomics approach in 4-HNE treated MCF-7 cells was reported to detect broad protein modifications using derivatization and fluorous solid-phase extraction [289]. With this method, 673 4-HNE modification sites (607 histidine sites, 60 Cys sites, five lysine sites, and one arginine site) were mapped to 432 proteins. While other methods have been reported as well (e.g., 2D SDS-PAGE separation and MALDI-TOF analysis [292]), a bottom-up proteomics approach with enrichment in modified proteins or peptides and LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis produces the most comprehensive results.

19.4.3.2. Eicosanoids

For many years, eicosanoids were used as biomarkers of lipid peroxidation induced by enzymatic and non-enzymatic processes. Primary peroxidation products such as HODEs, HETEs, F2-isoprostanes (pro-inflammatory prostaglandins F2-like compounds such as 8-isoprostane), and some oxysterols are known to be relatively stable in biological systems, allowing quantification with various MS-based methods of analysis.

Reversed phase LC-MS/MS analysis was used to simultaneously measure various glycerophospholipids and sterol oxidation products present in inflammatory and vascular disorders [293]. The study reported high yields of sterol oxidation products and active lipid mediators in the vascular region, such as 1-hexadecanoyl-2-oxovalaryl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, which induced upregulation of endothelial cell adhesion and chemoattractant proteins, and 5-cholesten-3a-ol 7a-hydroperoxide, a potent cytotoxic oxysterol. The results suggested that the formation of oxidized phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and oxysterols is related to ·NO metabolism where neutrophils and myeloperoxidase play important roles as catalysts in lipid peroxidation.

The level of F2-isoprostanes derived from peroxidation of AA was reported to be reduced by dietary omega-3 PUFAs [294]. Omega-3 PUFAs are more susceptible to oxidation compared with omega-6 PUFAs competing for the propagation and termination steps in the peroxidation process, ultimately resulting in decreased levels of F2-isoprostanes. In this study, the levels of 9-HODEs, 5-HEDE, and F2-isoprostanes in mouse liver tissue were successfully measured by LC-MS/MS with MRM. The method was optimized to increase sensitivity allowing trace analysis of omega-3 PUFAs autoxidation products in various biological specimens and this MRM based LC-MS/MS method has become the gold standard for targeted analysis of these species [295–297].

GC-MS methods were also applied to investigate lipid oxidation and the role of eicosanoids related to various pathological conditions [298, 299]. In these analyses, cellular lipids were typically extracted and trans-esterified, and then the hydroperoxides were reduced followed by SPE and derivatization. Electron impact ionization was applied to quantify 12-HETE, 11-HETE, 9-HETE, and 8-HETE by monitoring ions at m/z 301, 287, 259, and 271, respectively.

Since F2-isoprostanes were first reported as non-enzymatic products of AA peroxidation in the 1990s, this class of compounds has been one of the primary targets for assessment of oxidative stress. GC-MS methods for analysis of F2-isoprostanes and particularly 8-isoprostane were developed [300–302], and these methods are still being used as a complementary platform to LC-MS methods (described in Sect. 19.2.4).

19.4.3.3. Phospholipids

Traditionally, phospholipid species were analyzed using ESI-MS/MS analysis [303]. In the particular study referenced here, glycerophospholipids were separated on a preparative-scale TLC followed by derivatization with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine. Samples were directly injected into a quadrupole mass spectrometer that provided phospholipid profiles including various phosphatidylcholines (PCs), phosphatidylserines (PSs), and phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs). The analysis identified phospholipid peaks with intensities representing relative abundance of each species. Interestingly, the experiment identified primarily oxidized PCs as the unoxidized PCs were not separated on the TLC. Despite the narrow concentration range of linearity, ESI-MS/MS with direct injection provided unbiased compositions of PCs and PEs as also supported by follow-up studies [304].

Nevertheless, measuring phospholipids with this approach yields limited information about oxidation events; however, the method can provide information on the overall degree of unsaturation and therefore susceptibility to peroxidation. Studies using naked mole rats showed that indeed phospholipids containing high PUFAs are particularly prone to peroxidation and the membrane composition may, therefore, influence longevity [305]. Phospholipids analysis using shotgun lipidomics with GC-ESI-MS/MS showed that these animals had low levels of DHA in PCs, PEs, and PSs, which may contribute to the exceptional longevity of these animals. DHA is more susceptible to peroxidation due to a higher degree of unsaturation relative to other PUFAs, and consequently, the phospholipid membrane with higher DHA contents may experience increased oxidative damage.

19.4.3.4. Oxysterols

Oxysterols are oxidation products derived from enzymatic oxidation of cholesterol and its precursors [306]. Oxysterols are considered plasma biomarkers of disorders such as atherosclerosis, neurodegeneration, and inflammation. These species include 24-, 25-, 27-hydroxycholesterol; 7-ketocholesterol; lanosterol; lathosterol; 7-dehydrocholesterol; desmosterol; stigmasterol; sitosterol; and, campesterol. Simultaneous analysis of oxysterols to profile oxidized LDL in plasma samples was performed using GC-MS with SIM [307] while MRM was used in other studies [308].

Although the use of atmospheric-pressure chemical ionization (APCI) is not as widespread as ESI, APCI-MS has shown value for the analysis of lipids and other biological compounds because of its capability to ionize nonpolar compounds. Pentafluorobenzylation can be employed to provide electron-capturing moiety to target molecules and increase compatibility with electron capture detectors [309]. APCI-MS coupled with normal or reverse phase LC was used to determine sterols and oxysterols [310–315], triacylglycerols [316–319], and isoprostanes [320]. An extensive review of the methods for oxysterol analysis [321], points to the need for derivatization methods to enhance ionization efficiency for both APCI and ESI and to improve separation of isomeric peaks. A new derivatization method to convert hydroxyl into N,N-dimethylglycine ester was developed recently [322]. This method was utilized to measure oxysterols in human plasma using LC-APCI-MS/MS [323]. The experiment successfully determined 3β,5α,6β-triol, and 7-ketocholesterol with derivatization enhancing the ionization and fragmentation with APCI-MS. This method provided a rapid and non-invasive assay to detect Niemann-Pick C1 disease with high sensitivity and specificity [324].

19.4.4. Lipidomics Analysis

19.4.4.1. Targeted Lipidomics

While the MS methods described above for analysis of lipid peroxidation products target a select low number of species, advancements in MS instrumentation and chromatographic systems allow for simultaneous determination of tens to hundreds of lipid compounds in a single injection.

LC-MS/MS-based targeted lipidomics was applied to assess plasma lipid profile in high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice. The study analyzed >100 bioactive lipid mediators produced by cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase, and cytochrome P450 enzymes [325]. This approach determined changes of various lipid species and provided a clear profile of metabolic changes resulting from lipid oxidation events in obesity. Another study reported an LC-MS/MS method with MRM for quantification of isoprostanes in blood and tissue specimens [326]. Sample clean-up using SPE with mixed mode polymeric sorbents provided sensitive detection of various isomeric autoxidized products from AA, adrenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and DHA.

Selective and sensitive LC-MS/MS methods have also been developed to quantitate 57 oxylipins [327]. This method covered oxygenated lipids derived from five major omega-6 and omega-3 PUFAs, LA, AA, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), EPA, and DHA. Extraction and enrichment methods are critical for analysis of oxylipins since the hydrophilicity of these species varies widely, and sensitivity of detection is directly related to the rate of recovery from a biological matrix. For example, most PUFAs and their hydroperoxides are hydrophobic and can be efficiently extracted by liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) using a chloroform (or other hydrophobic solvents)/methanol/water system, while F2-isoprostanes are hydrophilic and remain in the polar matrix during LLE. In this case, SPE can be used at acidic pH to include most of the hydrophilic lipid mediators. Most commonly used sample preparation methods were compared [328], and SPE on reverse phase materials (C18) with the removal of the matrix by water and n-hexane before elution with methyl formate showed the best performance for the analysis of a broad spectrum of oxylipins in plasma. Unfortunately, none of the methods guarantee the best recovery of all oxylipin classes, and it is, therefore, important to select the method which best fits the class of compounds targeted by the analysis.

19.4.4.2. Bottom-up Lipidomics

A comprehensive review on shotgun lipidomics [329] describes various quantitative methods to detect intermediate or end products of lipid peroxidation. A select number of studies are highlighted here.

As described in the previous sections, PUFAs are a major target of ROS leading to the production of 4-hydroxyalkenal species. The most common 4-hydroxyalkenal species include 4-HNE and 4-HHE, derived from the oxidative reaction of omega-6 PUFAs and omega-3 PUFAs, respectively. Other 4-hydroxyalkenal species (e.g., 4-hydroxynondienal (4-HNDE) and 4-hydroxydodecatrienal (4-HDTE)) can also be produced through peroxidation of PUFAs. Various methods targeting individual 4-hydroxyalkenal species and their protein adducts were described earlier in this article. A new multi-dimensional MS-based shotgun lipidomics (MDMS-SL) method for quantitative analysis of 4-hydroxyalkenals [330] uses the direct infusion of the aqueous phase from Bligh-Dyer extraction along with isotopically labeled d3–4-HNE to relatively quantitate new 4-hydroxyalkenal species, 4-HNDE and 4-HDTE, in addition to 4-HNE. Carnosine was used as an additive to enhance ionization in positive ion mode, and in-source collision-induced dissociation (CID) was employed to obtain structural information. This method was applied to profile α,β-unsaturated aldehydes in various biological samples [330–332]. Oxidized fatty acids were also analyzed with a modified MDMS-SL [333]. In this approach, the ionization efficiency of oxidized FAs was increased by derivatization with 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbiodiimide enabling analysis of a broad range of oxidized FAs, including HETEs, diHETEs, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), nitrosylated FAs, and others.

High-energy collision-induced dissociation (HCD) is known to aid fragmentation of glycerophospholipid species [334]. An LC-MS-based untargeted lipidomics method was developed using high-resolution mass spectrometry with HCD fragmentation to yield both quantitative and structural information of hundreds of lipid molecules in rat liver mitochondria [335]. This general approach relies on the availability of accurate masses of compounds and fragmentation patterns in annotation systems such as the Metlin database [336], HMDB [56], and the LIPID MAPS database [337] for molecular identification. Phospholipid profiling using untargeted lipidomics can be an orthogonal validation tool for targeted lipid peroxidation studies given the fact that the degree of unsaturation in the fatty acyl group represents susceptibility to ROS attack.

19.5. Mass Spectrometry Analysis of DNA Oxidation

DNA oxidation is an inevitable consequence of cellular metabolism, and the endogenous level of most common DNA oxidation products in mammalian cells was estimated to at least 50,000 lesions [338].

The broad relevance of oxidative DNA damage in disease development remains to be elucidated, but it is clear that one of the consequences of DNA oxidation is mutagenesis [339]. This is supported by clinical evidence of increased oxidative DNA lesions in tumors. DNA mutations and genomic instability are crucial to carcinogenesis [340], and oxidative DNA damage is implicated in the etiology of cancer.

The process of DNA oxidation is triggered mainly by ROS such as 1O2,·OH, hypochlorous acid, and ten-eleven translocation (TET) oxygenases involved in epigenetic regulation [341]. Although a large number of oxidatively damaged base lesions were identified in experimental models (~100) [342], the number of lesions detected in clinical specimens is much lower. This is likely due to both their low natural abundance as well as limitations of current analytical platforms. Also, the measurement of these species is often limited by the instability of certain oxidation products such as hydroperoxides and is overwhelmed by nucleic acids undergoing artefactual oxidation during the course of extraction.