Abstract

Background:

COVID-19–related critical illness is associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Objective:

These evidence-based guidelines of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) are intended to support patients, clinicians, and other health care professionals in decisions about the use of anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19.

Methods:

ASH formed a multidisciplinary guideline panel, including 3 patient representatives, and applied strategies to minimize potential bias from conflicts of interest. The McMaster University Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Centre supported the guideline development process, including performing systematic evidence reviews (up to January 2022). The panel prioritized clinical questions and outcomes according to their importance for clinicians and patients. The panel used the GRADE approach to assess evidence and make recommendations, which were subject to public comment. This is an update to guidelines published in February 2021 and May 2021 as part of the living phase of these guidelines.

Results:

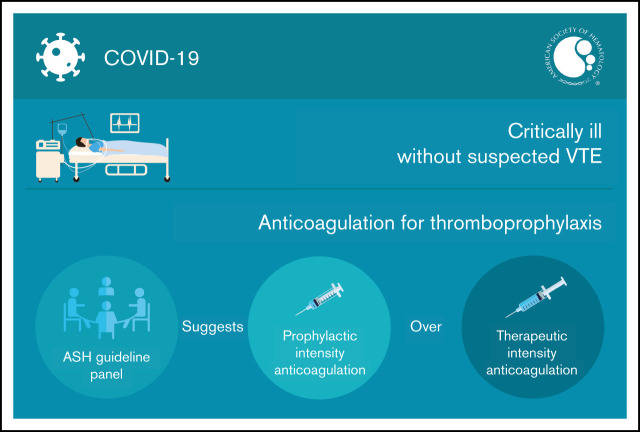

The panel made 1 additional recommendation: a conditional recommendation for the use of prophylactic-intensity over therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness who do not have suspected or confirmed VTE. The panel emphasized the need for an individualized assessment of thrombotic and bleeding risk.

Conclusions:

This conditional recommendation was based on very low certainty in the evidence, underscoring the need for additional, high-quality, randomized controlled trials comparing different intensities of anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness.

Visual Abstract

Summary of recommendations

Recommendation 1b

The ASH guideline panel suggests using prophylactic-intensity over therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness who do not have suspected or confirmed venous thromboembolism (VTE; conditional recommendation based on very low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁◯◯◯).

Remarks:

-

•

Patients with COVID-19–related critical illness are defined as those suffering from an immediately life-threatening condition who would typically be admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU). Examples include patients requiring hemodynamic support, ventilatory support, and renal replacement therapy.

-

•

A separate recommendation (1a) addresses the comparison of intermediate-intensity and prophylactic-intensity anticoagulation in critically ill patients with COVID-19.

-

•

An individualized assessment of the patient’s risk of thrombosis and bleeding is important when deciding on anticoagulation intensity. Risk assessment models to estimate thrombotic risk have been validated in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (critically or noncritically ill), with modest prognostic performance. No risk assessment models for bleeding have been validated for patients with COVID-19. The panel acknowledges that higher-intensity anticoagulation may be preferred for patients judged to be at low bleeding risk and high thrombotic risk.

-

•

At present, there is no direct high-certainty evidence comparing different types of anticoagulants for patients with COVID-19. Unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin was used in the identified studies.

-

•

This recommendation does not apply to patients who require anticoagulation to prevent thrombosis of extracorporeal circuits such as those on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or continuous renal replacement therapy.

Introduction

There is a high incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Earlier in the pandemic, VTE was reported in up to 22.7% of such patients despite the use of standard thromboprophylaxis.1 Thrombosis of the microvasculature contributes to other complications of COVID-19 including respiratory failure and death. At the same time, higher-intensity anticoagulation is associated with an increased risk of bleeding among hospitalized patients with COVID-19.2 Consequently, there has been strong interest in establishing whether intensified anticoagulant regimens improve outcomes.

These guidelines are based on systematic reviews of evidence conducted under the direction of the McMaster University Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Centre with international collaborators. This is an update on the previous American Society of Hematology (ASH) guideline published in May 2021,3 and focuses on the role of anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness. The panel followed best practice for guideline development recommended by the Institute of Medicine and the Guidelines International Network.4-6 The panel used the GRADE approach7-13 to assess the certainty of the evidence and formulate recommendations. The recommendation is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recommendations

| Recommendation | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Recommendation 1b. The ASH guideline panel suggests using prophylactic-intensity over therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness who do not have suspected or confirmed VTE (conditional recommendation based on very low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁◯◯◯). | • Patients with COVID-19–related critical illness are defined as those suffering from an immediately life-threatening condition who would typically be admitted to an ICU. Examples include patients requiring hemodynamic support, ventilatory support, and renal replacement therapy. • A separate recommendation (1a) addresses the comparison of intermediate-intensity and prophylactic-intensity anticoagulation in critically ill patients with COVID-19. • An individualized assessment of the patient’s risk of thrombosis and bleeding is important when deciding on anticoagulation intensity. Risk assessment models to estimate thrombotic risk in hospitalized patients have been validated in patients with COVID-19 (critically or noncritically ill), with modest prognostic performance. No risk assessment models for bleeding have been validated in patients with COVID-19. The panel acknowledges that higher-intensity anticoagulation may be preferred for patients judged to be at low bleeding risk and high thrombotic risk. • At present, there is no direct high-certainty evidence comparing different types of anticoagulants for patients with COVID-19. Unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin was used in identified studies. • This recommendation does not apply to patients who require anticoagulation to prevent thrombosis of extracorporeal circuits such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or continuous renal replacement therapy. |

Values and preferences

-

•

The guideline panel identified all-cause mortality, pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), major bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, ST-elevation myocardial infarction, multiple organ failure, limb amputation, invasive mechanical ventilation, ICU admission, and length of hospitalization as critical outcomes and placed a high value on reducing these outcomes with the interventions assessed.

-

•

Panel members noted that there was possible uncertainty and variability in the relative value that patients place on avoiding major bleeding events compared with reducing thrombotic events.

Explanations and other considerations

Please refer to the original ASH guideline on thromboprophylaxis for patients with COVID-19.3

Interpretation of strong and conditional recommendations

Please refer to the original ASH guideline on thromboprophylaxis for patients with COVID-19.3

Aims of these guidelines and specific objectives

Please refer to the original ASH guideline on thromboprophylaxis for patients with COVID-19.3 All recommendations and updates to these living guidelines are accessible at the ASH COVID-19 anticoagulation webpage.14

Description of the health problem

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant public health impact. As of 5 March 2022, more than 445 million cases and nearly 6 million deaths had been attributed to COVID-19–related illness globally.15 Thrombosis has emerged as an important complication of patients hospitalized with COVID-19–related critical illness, with VTE occurring in up to 22.7% of such patients, often despite the use of standard thromboprophylaxis.1 Moreover, microvascular thrombosis associated with COVID-19 may contribute to other adverse outcomes including respiratory failure and death.16

Previously published ASH guidelines issued a conditional recommendation in favor of prophylactic-intensity rather than higher-intensity anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness without suspected or confirmed VTE.3 Those recommendations were based on very low certainty evidence derived exclusively from observational studies. Since then, 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing therapeutic-intensity vs prophylactic-intensity anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness have been reported.17,18 This living guideline update incorporates evidence from these RCTs to address the role of therapeutic-intensity vs prophylactic-intensity anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness.

Description of the target populations

The target population, patients with COVID-19–related critical illness, is described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Definition of target population

| Target population | Definition |

|---|---|

| Critically ill | Patients with COVID-19 who develop respiratory or cardiovascular failure normally requiring advanced clinical support in the ICU or CCU but could include admission to another department if the ICU/CCU was over capacity. ICU/CCU capacity could vary according to the specific setting. |

Methods

This updated guideline recommendation on the use of therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation in critically ill patients was developed in the living phase of the ASH living guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for thromboprophylaxis for patients with COVID-19. The ASH guideline panel generated recommendation 1b on January 2022 before soliciting public comments.

We followed the same methods as published in the initial guideline,3 with the following important updates and differences for the recommendation reported here:

-

•

Guideline funding and management of conflicts of interest: supplemental File 4 provides updated “Participant Information Forms” for all panel members, detailing financial and nonfinancial interests, as well as the ASH conflict of interest policies agreed to by each individual. Supplemental File 5 provides the updated complete participant information forms of researchers on the systematic review team who contributed to these guidelines.

-

•

Formulating specific clinical questions and determining outcomes of interest: this updated manuscript focuses on 1 question: In patients with COVID-19–related critical illness who do not have confirmed or suspected VTE, should we use direct oral anticoagulants, low-molecular-weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, fondaparinux, argatroban, or bivalirudin at therapeutic intensity vs prophylactic intensity? There were no changes in the definitions for population (Table 2), anticoagulation intensity, or outcomes.3

-

•

Evidence review and development of the recommendation: a new evidence-to-decision framework was created for recommendation 1b (see Recommendations) using any applicable evidence and information from the evidence-to-decision (EtD) framework for the initial recommendation 17 and updated with new evidence and considerations specifically for recommendation 1b. The systematic review to identify comparative antithrombotic studies for the entire guideline was updated until 24 January 2022, the literature search strategy (supplemental File 6) was modified only to add search terms for antiplatelet agents for another guideline question, and the protocol (supplemental File 9) was modified to focus on inclusion of only RCTs for the guideline after the initial phase. Baseline risk estimates for outcomes for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness were updated with observational evidence until 27 July 2021 and prophylactic-intensity anticoagulation event rates from RCTs until 24 January 2022. The decision to create this updated guideline recommendation was based on publication of 2 RCTs,17,18 which were critically assessed by the evidence synthesis team and determined to increase the certainty of the evidence for critical outcomes. Decision thresholds were obtained for each critical outcome (Table 3) to support judgements about whether the magnitude of an effect estimate was trivial, small, moderate, or large, as well as for determining imprecision of the effect estimate. Thresholds were calculated using the outcome-specific utility value and results from a decision threshold survey that included the members of this panel.

-

•

Finally, for all outcomes, we report pooled effect estimates based on unadjusted effects from all trials. Because one adaptive multiplatform trial reported adjusted effect estimates for certain outcomes,18 we performed sensitivity analyses by pooling their adjusted effects with the unadjusted effects of the remaining trials to determine whether the results remained similar (see the footnotes of the evidence profile).

-

•

Document review: the initial draft recommendation was reviewed by all members of the panel and made available online from 7 March to 14 March 2022 for external review by stakeholders including allied organizations, other medical professionals, patients, and the public. As part of the public comment, there were 444 views; 1 individual or organization submitted a response that did not require changes to the document. On 11 April 2022, the ASH Guideline Oversight Subcommittee and the ASH Committee on Quality approved that the defined guideline development process was followed, and on 13 April 2022, the officers of the ASH Executive Committee approved submission of the updated guideline manuscript for publication under the imprimatur of ASH. The updated guideline manuscript was then subjected to peer review by Blood Advances.

-

•

How to use these guidelines: we refer readers to the description in the initial guideline publication from February 20213 and the user guide to ASH clinical practice guidelines.19

Table 3.

Decision thresholds per critical outcome

| Outcome | Utility value,mean (SD) | Decision thresholds (events per 1000; 95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trivial/small | Small/moderate | Moderate/large | ||

| Mortality | 0 | 16 (9 to 22) | 31 (22 to 39) | 60 (46 to 73) |

| PE, moderate | 0.42 (0.15) | 27 (15 to 38) | 53 (38 to 68) | 103 (80 to 125) |

| Proximal DVT, moderate | 0.58 (0.14) | 37 (21 to 53) | 73 (53 to 94) | 142 (110 to 173) |

| Major bleeding | 0.33 (0.23) | 23 (13 to 33) | 46 (33 to 59) | 89 (69 to 109) |

| Ischemic stroke, severe | 0.14 (0.10) | 18 (10 to 26) | 36 (26 to 46) | 69 (54 to 85) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.12 (0.10) | 18 (10 to 25) | 35 (25 to 45) | 68 (53 to 83) |

| Multiple organ failure | 0.15 (0.14) | 18 (10 to 26) | 36 (26 to 46) | 70 (54 to 86) |

| ST-elevation MI (STEMI) | 0.31 (0.19) | 23 (13 to 32) | 44 (32 to 57) | 86 (67 to 105) |

| Limb amputation | 0.26 (0.16) | 21 (12 to 30) | 41 (30 to 53) | 80 (63 to 98) |

| Long-term invasive ventilation | 0.20 (0.12) | 20 (11 to 28) | 38 (28 to 49) | 74 (58 to 91) |

Recommendations

Recommendation 1b

Should direct oral anticoagulants, low-molecular-weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, fondaparinux, argatroban, or bivalirudin be prescribed at therapeutic intensity or prophylactic intensity for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness who do not have suspected or confirmed VTE?

Recommendation 1b

The ASH guideline panel suggests using prophylactic-intensity over therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness who do not have suspected or confirmed VTE (conditional recommendation based on very low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁◯◯◯).

Remarks

-

•

Patients with COVID-19–related critical illness are defined as those suffering from an immediately life-threatening condition who would typically be admitted to an ICU. Examples include patients requiring hemodynamic support, ventilatory support, and renal replacement therapy.

-

•

A separate recommendation (1a) addresses the comparison of intermediate-intensity and prophylactic-intensity anticoagulation in critically ill patients with COVID-19.

-

•

An individualized assessment of the patient’s risk of thrombosis and bleeding is important when deciding on anticoagulation intensity. Risk assessment models to estimate thrombotic risk have been validated in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (critically or noncritically ill), with modest prognostic performance. No risk assessment models for bleeding have been validated for patients with COVID-19. The panel acknowledges that higher-intensity anticoagulation may be preferred for patients judged to be at low bleeding risk and high thrombotic risk.

-

•

At present, there is no direct high-certainty evidence comparing different types of anticoagulants for patients with COVID-19. Unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin was used in the identified studies.

-

•

This recommendation does not apply to patients who require anticoagulation to prevent thrombosis of extracorporeal circuits such as those on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or continuous renal replacement therapy.

Summary of the evidence.

We rated the certainty in the evidence as very low for all critical outcomes, mainly owing to serious indirectness and very to extremely serious imprecision (see evidence profile and EtD framework online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/W_BGvwzgPU0).

We found several systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials that addressed this question, either specifically or as part of a larger systematic review on anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19.20 None of these systematic reviews reported a summary of findings table or evidence profile, with certainty of the evidence assessment, for all critical outcomes prioritized for this recommendation. The living systematic review informing all recommendations for the ASH living guidelines since June 2020 provided the evidence for the evidence profile and EtD framework. Supplemental File 10 presents the characteristics of the included studies.

Two RCTs reported the effect of therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation in critically ill patients with COVID-19.17,18 In the publication, or by providing unpublished data, both trials reported results for all-cause mortality, PE, DVT, major bleeding, ischemic stroke, and ST-elevation myocardial infarction. One trial provided results for multiple organ failure, intracranial hemorrhage, limb amputation, invasive mechanical ventilation, and length of hospital admission. The authors of 1 RCT provided unpublished data for patients in the ICU separately.17 In accordance with the GRADE approach, the overall certainty of the evidence of effects was very low based on the lowest certainty among critical outcomes.

Benefits.

Based on the panel’s thresholds for effect sizes (Table 3), therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation may reduce pulmonary embolism with 52 fewer (95% confidence interval [CI]: 65 fewer to 30 fewer) cases per 1000 patients (odds ratio [OR]: 0.33; 95% CI: 0.18-0.60), may have little to no effect on deep venous thrombosis with 5 fewer (95% CI: 25 fewer to 37 more) cases per 1000 patients (OR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.37-2.01), may have little to no effect on ischemic stroke with 1 fewer (95% CI: 8 fewer to 17 more) cases per 1000 patients (OR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.36-2.45), and may have little to no effect on ST-elevation myocardial infarction with 1 fewer (95% CI: 2 fewer to 3 more) cases per 1000 patients (OR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.28-1.94), but the evidence is very uncertain for all outcomes (very low certainty).

Harms and burden.

Based on the panel’s thresholds for effect sizes (Table 3), therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation may increase all-cause mortality with 11 more (95% CI: 30 fewer to 59 more) cases per 1000 patients (OR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.84-1.35), may increase major bleeding with 22 more (95% CI: 6 fewer to 87 more) cases per 1000 patients (OR: 1.95; 95% CI: 0.75-5.09), may increase multiple organ failure with 108 more (95% CI: 38 fewer to 470 more) cases per 1000 patients (OR: 2.68; 95% CI: 0.50-14.18), may have little to no effect on intracranial hemorrhage with no events observed in the trials, may increase invasive mechanical ventilation with 35 more (95% CI: 120 fewer to 281 more) cases per 1000 patients (OR: 1.21; 95% CI: 0.41-3.51), may increase limb amputation with 10 more (95% CI: 2 fewer to 219 more) cases per 1000 patients (OR: 4.43; 95% CI: 0.21-95.06), and may increase length of admission with 2 more (95% CI: 0.44 more to 3.56 more) days, but the evidence is very uncertain for all outcomes (very low certainty).

Other EtD criteria and considerations.

The guideline panel noted that there was possible uncertainty and variability in the relative value patients place on reducing thrombotic events compared with avoiding major bleeding events. The panel agreed that the use of prophylactic-intensity anticoagulation would be acceptable to patients and health care providers. However, given the low certainty in the evidence for some outcomes, there may be regional variation in the acceptability of therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation, particularly in regions where baseline VTE risk may be lower (eg, Asian populations).21,22 In addition, the panel noted possible racial and ethnic disparity in clinical trial enrollment. However, the intervention was not felt to have a differential impact on health equity relative to the comparison.

Conclusions for this recommendation.

The use of decision thresholds (Table 3) allowed the panel to quantify the magnitude of effect per outcome to come to an overall judgement on the balance of health effects. In terms of desirable effects, although there was a suggestion of a small reduction in PE with therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation, this evidence was of very low certainty. Meanwhile, trivial-to-moderate harms were observed for multiple other critical outcomes including mortality, major bleeding, invasive mechanical ventilation, multiple organ failure, and limb amputation, some of which were felt to be independent. Taken together, the panel judged the aggregate harm of the intervention to be moderate, albeit based on very low certainty in the evidence.

These moderate harms were felt to outweigh the small benefits of therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation, and therefore prophylactic-intensity anticoagulation was suggested. The panel acknowledged that an individualized decision based on each patient’s thrombotic and bleeding risk is important.

What are others saying and what is new in these guidelines?

Numerous national and international organizations have published clinical practice guidelines or guidance documents on the role of anticoagulation in hospitalized, critically ill COVID-19 patients. Among those published or updated since 2021, the year that RCTs comparing different intensities of anticoagulation were first published, both the Japanese living guidelines on drug management for COVID-1923 and the European Respiratory Society living guidelines24 recommend anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness but do not specify an intensity. By contrast, the French guideline25 suggests that patients with severe COVID-19 (oxygen requirement greater than 6 L/min or mechanical ventilation) should receive at least intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, although these guidelines were written before the publication of the multiplatform18 and INSPIRATION26 randomized trials. The US National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guideline, the World Health Organization Living Guidance document, and draft guidelines from the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis recommend that patients who require ICU-level care should receive standard prophylactic-intensity (rather than intermediate- or therapeutic-intensity) anticoagulation as VTE prophylaxis.27-29

Major differences between the ASH guidelines and these other documents include use of high-quality systematic reviews and EtD frameworks, marker states to estimate the relative importance of key outcomes to patients, and decision thresholds to facilitate judgments about the magnitude of desirable and undesirable effects.

Limitations of these guidelines

The limitations of these guidelines are inherent in the very low certainty of the evidence we identified for the research question. In addition, dramatic changes have occurred over the course of the pandemic with respect to circulating viral variants, the affected patient population, and the use of treatments other than anticoagulants for management of COVID-19–related critical illness (eg, antiviral agents, corticosteroids, Janus kinase inhibitors, interleukin-6 inhibitors). Much of the evidence included in our systematic review was collected earlier in the pandemic and may not fully reflect baseline risk or the impact of different intensities of anticoagulation in the current phase of the pandemic.

Plans for updating these guidelines

Our recommendations will continue to be updated based on living reviews of evolving evidence. Our methods of living systematic reviews and recommendations, including criteria for deciding when to reassess and update recommendations, are described elsewhere.3

Updating or adapting recommendations locally

Adaptation of these guidelines will be necessary in many circumstances. These adaptations should be based on the associated EtD frameworks.11

Priorities for research

Based on gaps in evidence identified during the guideline development process, the panel identified the following research priorities:

-

•

Studies assessing baseline VTE risk, major bleeding risk, and mortality in critically ill patients receiving prophylactic-intensity anticoagulation therapy and how these risks have varied over the course of the pandemic

-

•

Additional large, high-quality RCTs comparing therapeutic-intensity with prophylactic-intensity anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19–associated critical illness, as the current evidence of effects is of very low certainty

-

•

Studies examining the impact of non-anticoagulant interventions (eg, vaccines, corticosteroids, antiviral therapies, anticytokine therapies, monoclonal antibody therapies) on thrombotic risk

-

•

Studies examining the impact of different viral variants on thrombotic risk

-

•

Development and validation of risk assessment models for thrombosis and bleeding for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness

-

•

Studies examining the impact of anticoagulant therapy on thrombosis and bleeding outcomes for patients of differing race/ethnicity

-

•

Studies comparing mortality, thrombosis, bleeding, and functional outcomes with different available anticoagulant agents and intensities

-

•

Studies estimating the relative disutility of thrombotic and bleeding outcomes for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Rob Kunkle, Eddrika Russell, Deion Smith, and Kendall Alexander for overall coordination of the guideline panel. The authors also thank the following members of the knowledge synthesis team for contributions to this work: Imad Bou Akl, Angela Barbara, Antonio Bognanni, Emma Cain, Matthew Chan, Heba Hussein, Phillipp Kolb, Razan Mansour, Giovanna Muti-Schünemann, Menatalla Nadim, Atefeh Noori, Thomas Piggott, Yuan Qiu, and Finn Schünemann. Finally, the authors thank the investigators of the HEP-COVID trial for providing unpublished aggregate data specifically for patients who were admitted to the ICU.

D.R.T. was supported by a career development award from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1K01HL135466).

Authorship

Contribution: A.C., E.K.T., and R.N. wrote the manuscript. All other authors contributed to critical revisions of the manuscript and approved of the content. Members of the knowledge synthesis team (R.N., R.A.J., Y.A.J., M.B., R.C., L.E.C.-L., K.D., A.J.D., S.G.K., G.P.M., R.Z.M., B.A.P., Y.R.B., A.S., K.S., W.W.) searched the literature, extracted data from eligible studies, analyzed the data, and prepared evidence summaries and evidence to decision tables. Panel members (A.C., E.K.T., H.J.S., P.A., C.B., K.D., M.T.D., D.D., D.O.G., S.R.K., F.A.K., A.I.L., I.N., A.P., M.R., K.M.S., D.M.S., M.S., D.R.T., K.T., R.A.M.) assessed the evidence, voted, and made judgments within the evidence to decision framework and discussed and issued the recommendations. The methods leadership team (R.N., R.B.-P., K.D., A.S., K.S., A.C., E.A.A., W.W., R.A.M., H.J.S.) developed the methods and provided guidance to the knowledge synthesis team and guideline panel. A.C., R.A.M., and R.N. were the co-chairs of the panel and led panel meetings.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: All authors were members of the guideline panel or members of the systematic review team or both. As such, they completed a disclosure of interest form, which was reviewed by ASH and is available as supplemental Files 4 and 5.

Correspondence: Adam Cuker, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, 3400 Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: adam.cuker@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

References

- 1.Nopp S, Moik F, Jilma B, Pabinger I, Ay C. Risk of venous thromboembolism for patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4(7):1178-1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiménez D, García-Sanchez A, Rali P, et al. Incidence of VTE and bleeding among hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2021;159(3):1182-1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuker A, Tseng EK, Nieuwlaat R, et al. American Society of Hematology 2021 guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for thromboprophylaxis for patients with COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2021;5(3):872-888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schünemann HJ, Al-Ansary LA, Forland F, et al. ; Board of Trustees of the Guidelines International Network . Guidelines International Network: principles for disclosure of interests and management of conflicts in guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(7):548-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qaseem A, Forland F, Macbeth F, Ollenschläger G, Phillips S, van der Wees P; Board of Trustees of the Guidelines International Network . Guidelines International Network: toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(7):525-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, et al. ; GRADE Working Group . GRADE evidence to decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: introduction. BMJ. 2016;353:i2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, et al. ; GRADE Working Group . GRADE evidence to decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016;353:i2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S, et al. ; GRADE Working Group . Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations I: critical appraisal of existing approaches yhe GRADE Working Group. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schünemann HJ, Best D, Vist G, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group . Letters, numbers, symbols and words: how to communicate grades of evidence and recommendations. CMAJ. 2003;169(7):677-680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Brozek J, et al. GRADE evidence to decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;81:101-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):395-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. ; GRADE Working Group . GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924-926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Society of Hematology. ASH guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19. Available at: https://www.hematology.org/education/clinicians/guidelines-and-quality-care/clinical-practice-guidelines/venous-thromboembolism-guidelines/ash-guidelines-on-use-of-anticoagulation-in-patients-with-covid-19. Accessed 16 January 2022.

- 15.Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Coronavirus resource center. Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed 6 January 2022.

- 16.Poor HD. Pulmonary thrombosis and thromboembolism in COVID-19. Chest. 2021;160(4):1471-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spyropoulos AC, Goldin M, Giannis D, et al. ; HEP-COVID Investigators . Efficacy and safety of therapeutic-dose heparin vs standard prophylactic or intermediate-dose heparins for thromboprophylaxis in high-risk hospitalized patients with COVID-19: the HEP-COVID randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(12):1612-1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goligher EC, Bradbury CA, McVerry BJ, et al. ; ATTACC Investigators . Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):777-789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izcovich A, Cuker A, Kunkle R, et al. A user guide to the American Society of Hematology clinical practice guidelines. Blood Adv. 2020;4(9): 2095-2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reis S, Popp M, Schmid B, et al. Safety and efficacy of intermediate- and therapeutic-dose anticoagulation for hospitalised patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;11(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang D, Chan P-H, She H-L, et al. Secular trends and etiologies of venous thromboembolism in Chinese from 2004 to 2016. Thromb Res. 2018;166:80-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheuk BLY, Cheung GCY, Cheng SWK. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in a Chinese population. Br J Surg. 2004;91(4):424-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamakawa K, Yamamoto R, Terayama T, et al. ; Special Committee of the Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2020 (J‐SSCG 2020), the COVID‐19 Task Force . Japanese rapid/living recommendations on drug management for COVID-19: updated guidelines (September 2021). Acute Med Surg. 2021;8(1):e706.34815889 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chalmers JD, Crichton ML, Goeminne PC, et al. Management of hospitalised adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a European Respiratory Society living guideline. Eur Respir J. 2021;57(4):2100048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Godon A, Tacquard CA, Mansour A, et al. ; Gihp, the GFHT . Prevention of venous thromboembolism and haemostasis monitoring for patients with COVID-19: Updated proposals (April 2021): From the French working group on perioperative haemostasis (GIHP) and the French study group on thrombosis and haemostasis (GFHT), in collaboration with the French society of anaesthesia and intensive care (SFAR). Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2021;40(4):100919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadeghipour P, Talasaz AH, Rashidi F, et al. ; INSPIRATION Investigators . Effect of intermediate-dose vs. standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation on thrombotic events, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment, or mortality among patients with COVID-19 admitted to the intensive care unit: the INSPIRATION randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(16):1620-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Institutes of Health. The COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel’s statement on anticoagulation in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Available at: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/statement-on-anticoagulation-in-hospitalized-patients/. Accessed 16 January 2022.

- 28.Living guidance for clinical management of COVID-19. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2021-2. Accessed 6 April 2022.

- 29.ISTH draft guidelines for antithrombotic treatment in COVID-19. Available at: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.isth.org/resource/resmgr/guidance_and_guidelines/covid19/covid-19-draft_for_comment.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.