Abstract

Background

The purpose of the RAFAS (Risk and Benefits of Urgent Rhythm Control of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Acute Stroke) trial was to explore the risks and benefits of early rhythm control in patients with newly documented atrial fibrillation (AF) during an acute ischemic stroke (IS).

Method and Results

An open‐label, randomized, multicenter trial design was used. If AF was diagnosed, the patients in the early rhythm control group started rhythm control within 2 months after the occurrence of an IS, unlikely the usual care. The primary end points were recurrent IS within 3 and 12 months. The secondary end points were a composite of all deaths, unplanned hospitalizations from any cause, and adverse arrhythmia events. Patients (n=300) with AF and an acute IS (63.0% men, aged 69.6±8.5 years; 51.2% with paroxysmal AF) were randomized 2:1 to early rhythm control (n=194) or usual care (n=106). A total of 273 patients excluding those lost to follow‐up (n=27) were analyzed. The IS recurrences did not differ between the groups within 3 months of the index stroke (2 [1.1%] versus 4 [4.2%]; hazard ratio [HR], 0.257 [log‐rank P=0.091]) but were significantly lower in the early rhythm control group at 12 months (3 [1.7%] versus 6 [6.3%]; HR, 0.251 [log‐rank P=0.034]). Although the rates of overall mortality, any cause of hospitalizations (25 [14.0%] versus 16 [16.8%]; HR, 0.808 [log‐rank P=0.504]), and arrhythmia‐related adverse events (5 [2.8%] versus 1 [1.1%]; HR, 2.565 [log‐rank P=0.372]) did not differ, the proportion of sustained AF was lower in the early rhythm control group than the usual care group (60 [34.1%] versus 59 [62.8%], P<0.001) in 12 months.

Conclusions

The early rhythm control strategy of an acute IS decreased the sustained AF and recurrent IS within 12 months without an increase in the composite adverse outcomes.

Registration

URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT 02285387.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, ischemic stroke, rhythm control, usual care

Subject Categories: Atrial Fibrillation, Cerebrovascular Disease/Stroke

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AAD

antiarrhythmic drug agent

- AHA

American Heart Association

- CHA2DS2VASc

congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years (2 points), type 1 or 2 diabetes, stroke or transient ischemic attack or thromboembolism (2 points), vascular disease (prior myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, or aortic plaque), aged 65–75 years, sex category (female)

- EAST‐AFNET 4

Early Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation for Stroke Prevention Trial

- RAFAS

Risk and Benefits of Urgent Rhythm Control of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Acute Stroke

- IS

ischemic stroke

- mRS

modified Rankin scale

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

In this study, patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who experienced an acute ischemic stroke (IS) were randomized to either an early rhythm control group or usual care group.

Because patients who experience acute IS are at high risk of recurrent stroke, early detection of AF has important clinical implications.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

The purpose of this randomized trial was to evaluate a clinical benefit and risk of early rhythm control of AF in patients who experience acute IS.

The early rhythm control of AF in patients who experienced an acute stroke reduced the risk of sustaining AF and recurrent IS within 12 months without an increase in mortality or hospitalizations.

Finally, in patients with AF and an acute IS, early rhythm control of AF is superior to usual care to prevent recurrent strokes.

Ischemic stroke (IS) accounts for a large proportion of deaths from all cardiovascular diseases, and the 1‐year mortality rate after an IS is ≈12%. 1 Cardiogenic embolisms accounts for ≈20% of IS cases. 2 The atrial fibrillation (AF) detection rate within 30 days by outpatient telemetry is ≈23% in patients with cryptogenic strokes or transient ischemic attacks within a median of 7 days (range, 2–19 days) after an event. 3 , 4 In addition, the probability of a recurrent stroke is 9% to 17% within 3 months of an index stroke and is highest within a month. 5 , 6 Therefore, early detection of AF provides the basis of the risk stratification, recurrent stroke prevention, and appropriate treatment for anticoagulation or AF rhythm control. 7

The recently published EAST‐AFNET 4 (Early Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation for Stroke Prevention Trial) showed that early rhythm control reduced the incidence of a cardiovascular outcome and did not increase the safety outcome in AF that occurred within the past year. 8 This suggests that early rhythm control for AF detected in the acute phase in patients with IS is also important to prevent recurrent IS. However, it is uncertain whether the early rhythm control of AF is beneficial in the acute stage of a stroke. Moreover, although AF is considered a major risk factor for a recurrent stroke, concern remains regarding the risk and adverse events related to early rhythm control, including antiarrhythmic drug agents (AADs), electrical cardioversion, and catheter ablation.

In this randomized multicenter study, we evaluate the clinical risks and benefits of early rhythm control among patients with an acute IS and AF by analyzing the safety and effectiveness of early rhythm control of AF, including AADs, in patients diagnosed with an acute IS as compared with usual care (rate control or rhythm control after 2 months).

Methods

Study Design and Oversight

The RAFAS (Risk and Benefits of Urgent Rhythm Control of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Acute Stroke) trial is an open‐label, randomized, multicenter, controlled trial conducted to assess whether early rhythm control of AF after an acute stroke is safe and more effective for protection against recurrent strokes than usual care (ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT02285387). The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The trial was approved by the institutional review board at each participating center (Yonsei University Health System, Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital, Seoul Hospital, Kyung‐Hee University Hospital, and Hanyang University Hospital). The study design was determined through discussion and collaboration between the neurologists and cardiologists among the RAFAS investigators. The RAFAS trial was conducted among patients with acute strokes admitted to 5 tertiary hospitals in Korea since November 2014. Patients for whom AF was diagnosed through intensive ECG monitoring for at least 72 hours were enrolled with the consent of the patient or guardian. All patients provided written informed consent, and if the patient’s consciousness was not clear, written consent was given by the patient’s guardian. In addition, the data safety and monitoring board monitored serious adverse events and the risks biannually during the study.

Patient Selection

This study included patients aged 20 to 80 years who were hospitalized for an acute stroke. At least 72 hours of continuous ECG monitoring was performed from the time of the stroke diagnosis, and regular ECG and 24‐hour Holter monitoring were performed for up to 60 days. If AF was diagnosed, anticoagulation and rate control medications (β‐blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, or digoxin) were administered according to standard guidelines at the discretion of the cardiologist and neurologist. 9 , 10 If patients were assigned to the early rhythm control group, AADs (Vaughan Williams classification class Ic or III) were administered as soon as possible within 2 months after the stroke diagnosis. Anticoagulation, rate control, and cardiovascular medications were mandated in both groups. The major exclusion criteria were: (1) a documented left atrial diameter >55 mm; (2) a contraindication to chronic AADs, anticoagulation therapy, or heparin; (3) acute coronary syndrome, cardiac surgery, or angioplasty within 2 months before enrollment; (4) a planned cardiovascular intervention or surgery; (5) age >80 years, and (6) a life expectancy of <12 months.

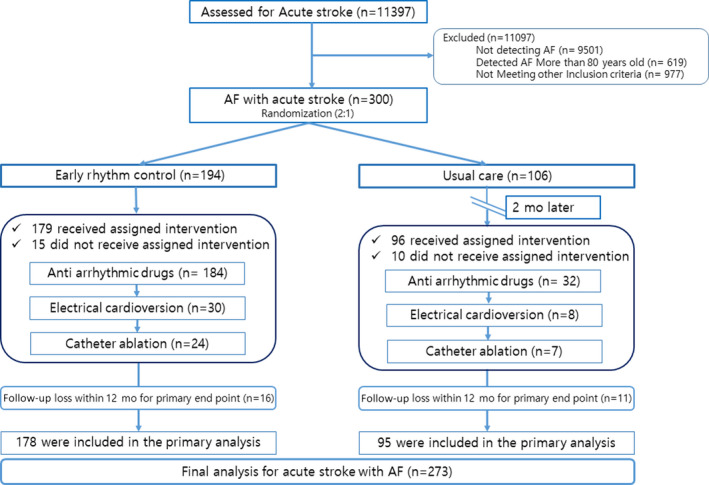

Randomization, Baseline Evaluation, and Follow‐Up

Patients diagnosed with an acute stroke with AF were randomized 2:1 to an early rhythm control group or a usual care group (Figure 1). The basic clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients were analyzed at the time of enrollment. Anticoagulation was the same in both groups according to the guidelines 11 from the time of the diagnosis of AF, and the doses of nonvitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants were adjusted according to the “on‐label guidelines” with reference to the renal function, age, weight, and other factors. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Pharmacological agents for controlling heart rate (β‐blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, or digoxin) were prescribed at the doctor’s discretion, according to the left ventricular function, and presence of asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. All patients underwent ECG and 24‐hour Holter monitoring (3, 6, and 12 months) from enrollment to 12 months. After discharge, the patient’s condition was assessed every 3 months in the outpatient clinic or, if outpatient visits were not conducted, by phone calls.

Figure 1. Trial flow chart.

AF indicates atrial fibrillation.

Early Rhythm Control and Usual Care

All patients were monitored with continuous ECG for at least 72 hours after the acute stroke. If AF was diagnosed through periodic ECG and 24‐hour Holter monitoring within 2 months, rhythm control in the early rhythm control group was started as soon as possible within 2 months after an acute stroke. Early rhythm control was performed following a stepwise sequential approach: AADs, electrical cardioversion, and catheter ablation. 9 , 16 If AF was diagnosed, AADs were used as the initial treatment. If AF developed despite the use of AADs or if AADs could not be used, catheter ablation was performed. In cases of persistent AF, electrical cardioversion was performed to check sinus node dysfunction along with the use of AADs. AADs were used immediately in patients with a Vaughan Williams classification of class Ic or III at the cardiologist’s discretion, depending on whether the patient had heart failure. In contrast, while heart rate control and anticoagulation medications were prescribed in the usual care group, AADs, cardioversion, and catheter ablation were not performed within 2 months of an acute stroke. Both groups underwent rhythm control according to the physicians’ discretion based on the current guidelines within 2 months of the acute stroke. As mentioned above, the anticoagulation and cardiovascular medications were the same in both groups and prescribed according to standard guidelines. 9 , 11 , 16

Study Outcomes

The primary end points were recurrent IS within 3 and 12 months, respectively. The secondary end points were a composite of all deaths from any cause, unplanned hospitalization from any cause, or recurrent IS and adverse arrhythmia events. In particular, adverse arrhythmia events included syncope related to bradycardia, tachycardia, pacemaker implantations (permanent or temporary), or documented sick sinus syndrome. Sustained AF was defined as documented persistent AF at the 12‐month follow‐up.

Statistical Analysis

Based on 2‐tailed z tests with a pooled variance, the overall sample size of 300 patients (200 in the early rhythm control group and 100 in the usual care group=2:1) achieved an 80% power at a .05 significance level to detect differences between the group proportions of −0.15 when the proportion of composite events in the usual care group was 0.3. The dropout rate was assumed to be 10%. Final analysis was performed in patients except those lost to follow‐up (Figure 1). The primary and secondary end points were acquired at the time of the interim analysis and final analysis. At the time of the interim analysis, although the primary end point was not significant and adverse arrhythmia events among the secondary end points had increased tendencies, the effects were not statistically significant in the early rhythm control group. The trial was maintained to final enrollment as planned after the first interim analysis. The final statistical analysis was performed by the Clinical Trial Center of Ewha Womans University Medical Center. The statistical analyses were conducted in a blind state to avoid researcher bias. The early rhythm control group was compared with the usual care group based on the intention‐to‐treat principle. In addition, a per‐protocol analysis was performed among only those patients who completed the originally assigned treatment, and an on‐treatment analysis was performed according to the treatment actually received. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean with SD or median with interquartile range based on the assumption of a normal distribution. Qualitative variables were described by the count and percentage. Statistical tests on the comparisons between groups were assessed using t tests, Mann−Whitney U tests, and chi‐square tests. The primary and secondary outcomes were evaluated using a Kaplan−Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazard model. Regarding the time‐to‐event, the difference in the survival curve between the 2 groups was evaluated through a log‐rank test, and the relationships were assessed by estimating the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI. The assumptions of the Cox proportional hazards model were satisfied, according to the log minus log plots or Schoenfeld residuals. Through subgroup analysis, we evaluated whether there were differences in the effects of the treatment methods on the clinical outcomes according to the basic characteristics. The test for differences was evaluated by fitting the interaction term to the model. In addition, a multivariate analysis was performed while taking into account the covariates associated with the clinical outcomes or with a P<0.1 in the univariate analysis. Variance inflation factors were used to measure the multicollinearity in the multivariate analysis, and all had values <2.0. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc). Two‐tailed P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Assessment and Baseline Evaluation

This study was conducted using a sample of 300 patients with acute strokes who were admitted to 5 tertiary hospitals in Korea starting in November 2014. The early rhythm control group included 194 patients, and the usual care group included 106 patients (Figure 1). The age, sex, and AF type did not differ between the 2 groups. In addition, there were no differences between the groups regarding the CHA2DS2VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years [2 points], type 1 or 2 diabetes, stroke or transient ischemic attack or thromboembolism [2 points], vascular disease [prior myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, or aortic plaque], aged 65–75 years, sex category [female]) score, so we determined that the randomization was appropriate (Table 1). Among the primary intention‐to‐treat population, the clinical outcomes of 27 (9%) patients were not confirmed at 12 months (follow‐up loss, 16 [8.2%] patients in the early rhythm control group and 11 [10.4%] patients in the usual care group) (Figure 1). In the early rhythm control group, the first point of use of AADs was within 8.9 days of an acute stroke, 82 (42.3%) patients took class Ic AADs, and 102 (52.6%) received class III AADs (Figure S1). Electrical cardioversion was performed at 126.7 days (30–255 days) in 30 (15.5%) patients, and catheter ablation at 200.9 days (61–355 days) in 24 (12.4%) patients in the early rhythm control group (Figure 1). Rate control agents were used at a frequency of β‐blockers in 211 (70.3%) patients, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers in 89 (29.7%) patients, and digoxin in 30 (10%) patients. AADs were prescribed in 32 symptomatic patients (30.2%) in the usual care group 2 months after the acute IS events. In terms of antithrombotic treatment, 89.3% of the patients received nonvitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, 4.5% received vitamin K antagonists, and 5.1% received single or 4.1% dual antiplatelet agents prescribed for a hemorrhagic transformation and high bleeding risk (Table 1). With the recent increase in the use of nonvitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, only 12 patients used warfarin. The time in therapeutic range by Rosendaal method was 40.9%. There was no difference in National Institutes of Health (NIH) stroke score at the time of initial enrollment. However, at 12 months, the early rhythm control group showed better modified Rankin scale (mRS; good outcome) than the usual care group. This appears to be the result of early rhythm control helping patients recover quickly (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients at Baseline

| Characteristics |

Early rhythm control (n=178) |

Usual care (n=95) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 68.9±8.9 | 70.1±7.8 | 0.270 |

| Men, n (%) | 108 (60.7) | 61 (64.2) | 0.567 |

| Paroxysmal AF, n (%) | 94 (52.8) | 48 (50.5) | 0.719 |

| Weight, kg | 65.3±10.1 | 66.0±9.9 | 0.548 |

| Height, cm | 163.7±8.5 | 165.1±8.5 | 0.186 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.3±3.1 | 24.2±2.9 | 0.686 |

| Thrombolysis, n (%) | 60 (33.7) | 28 (29.5) | 0.476 |

| Echocardiography | |||

| LA volume index, mL/m2 | 44.0 (35.2–53.4) | 41.9 (33.0–59.9) | 0.718 |

| LAAP dimension, mm | 43.8 (23–75) | 42.0 (25–66) | 0.766 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 63.0 (58.0–67.0) | 62.0 (58.0–68.0) | 0.896 |

| E/E’ | 12.2 (9.0–14.9) | 12.1 (9.3–14.7) | 0.960 |

| CHA2DS2VASc score | 4.4±1.5 | 4.3±1.6 | 0.564 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 11 (6.2) | 9 (9.6) | 0.308 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 115 (65.0) | 70 (74.5) | 0.110 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 59 (33.1) | 29 (30.9) | 0.700 |

| Vascular diseases, n (%) | 11 (6.2) | 6 (6.4) | 0.948 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.172 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 76.7±19.8 | 75.2±18.9 | 0.555 |

| Low‐density lipoprotein, mg/dL | 95.3±32.6 | 102.7±36.0 | 0.089 |

| Glycated hemoglobin, % | 5.9 (5.6–6.4) | 5.9 (5.6–6.5) | 0.632 |

| Antithrombotic agents after a stroke, n (%) | |||

| Warfarin | 8 (4.5) | 4 (4.3) | >0.999 |

| NOAC | 158 (89.3) | 85 (89.5) | 0.958 |

| Single antiplatelet agent | 8 (4.5) | 6 (6.4) | 0.568 |

| Dual antiplatelet agent | 7 (4.0) | 4 (4.3) | >0.999 |

| Dual therapy (warfarin‐based) | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 0.545 |

| Dual therapy (NOAC‐based) | 44 (24.9) | 24 (25.5) | 0.903 |

| Triple therapy (warfarin‐based) | 0 | 0 | NA |

| NIH stroke score (initial) | 4.0 (2.0–11.0) | 6.0 (2.0–13.0) | 0.138 |

| mRS (3 mo), n (%) | |||

| Good outcome (0–2) | 109 (71.7) | 47 (60.3) | 0.078 |

| Poor outcome (3–6) | 43 (28.3) | 31 (39.7) | |

| mRS (12 mo), n (%) | |||

| Good outcome (0–2) | 111 (79.3) | 44 (66.7) | 0.05 |

| Poor outcome (3–6) | 29 (20.7) | 22 (33.3) | |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; CHA2DS2VASc, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years (2 points), type 1 or 2 diabetes, stroke or transient ischemic attack or thromboembolism (2 points), vascular disease (prior myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, or aortic plaque), aged 65–75 years, sex category (female); eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LA, left atrium; LAAP, left atrial anterior‐posterior; mRS, modified Rankin scale; NA, not applicable; NIH, National Institutes of Health; and NOAC, nonvitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant.

Follow‐Up Period and Crossover

Among 194 patients assigned to the early rhythm control group, 179 (92.3%) patients received the assigned treatment and 15 (8.4%) crossed over to the usual care group for several reasons, as described in Table S1. Furthermore, among the 106 patients who were assigned to the usual care group, 96 (90.6%) received the assigned treatment and 10 (9.4%) crossed over to the early rhythm control group because of symptomatic tachyarrhythmia events (Figure 1). Finally, 273 patients except those lost to follow‐up (n=27) were analyzed for primary and secondary end points.

Primary End Points

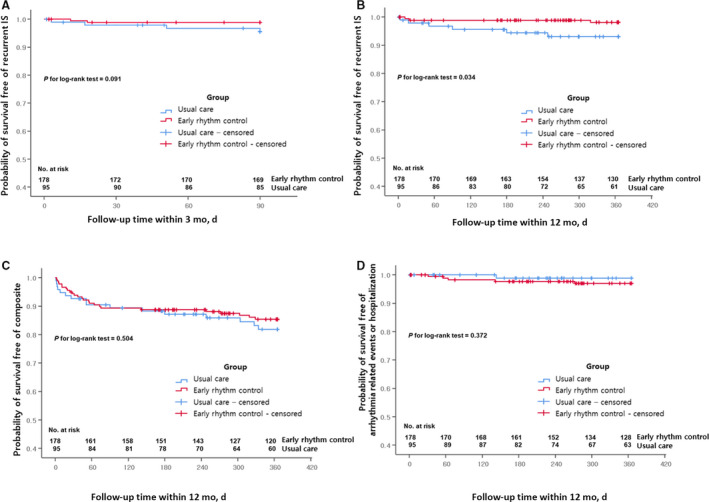

The recurrent IS within 3 months did not significantly differ between the groups (2 [1.1%] versus 4 [4.2%]; HR, 0.257 [P=0.117]). Recurrent IS within 12 months occurred in fewer patients in the early rhythm control group than the usual care group (3 [1.7%] versus 6 [6.3%]; HR, 0.251 [P=0.05]) (Table 2). In addition, when considering the time sequence, Kaplan‐Meier curves showed that the early rhythm control group had fewer recurrent IS within 12 months than the usual care group (P=0.034 by log‐rank test, Figure 2A and 2B). When considering age, NIH stroke scale, and vascular diseases (P<0.1 in univariate analysis), the early rhythm control group had significantly reduced recurrent ISs within 12 months (HR, 0.215; 95% CI, 0.052–0.894 [P=0.035], multivariate Cox regression) (Table 3). A total of 25 (8.3%) patients did not receive the intervention assigned to their original group (Figure 1), so per‐protocol and on‐treatment analyses were performed. The results were consistent with those of the intention‐to‐treat analysis (Tables S2 and S3). In addition, there was no difference in primary outcomes of early rhythm control according to AF type and sex (Table S4).

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Clinical Outcomes

| Early rhythm control (n=178) |

Usual care (n=95) |

HR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome, n (%)* | |||||

| Recurrent stroke in 3 mo | 2 (1.1) | 4 (4.2) | 0.257 | 0.047–1.405 | 0.117 |

| Recurrent stroke in 12 mo | 3 (1.7) | 6 (6.3) | 0.251 | 0.063–1.003 | 0.050 |

| Secondary outcome, n (%)** | |||||

| Composite outcome in 3 mo | 19 (10.7) | 10 (10.5) | 0.995 | 0.463–2.140 | 0.990 |

| Composite outcome in 12 mo | 25 (14.0) | 16 (16.8) | 0.808 | 0.431–1.513 | 0.505 |

| Arrhythmia‐related events in 3 mo | 3 (1.7) | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Arrhythmia‐related events in 12 mo | 5 (2.8) | 1 (1.1) | 2.565 | 0.3–21.958 | 0.390 |

| Sustained AF | 60 (34.1) | 59 (62.8) | <0.001 | ||

| AF detection period in the consecutive Holter during 12 mo, mo | 3.0 (1.0–9.0) | 7.0 (1.0–12.0) | 0.002 | ||

| Stroke to NSR duration, d | 13.0 (2.0–84.0) | 2.0 (0.0–98.5) | 0.083 | ||

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not available; and NSR, normal sinus rhythm.

Primary: recurrent ischemic stroke (IS), recurrent IS in 3 and 12 months.

Secondary: a composite of death from any cause or hospitalization for any cause, recurrent stroke, and arrhythmia‐related events.

Figure 2. Kaplan−Meier curve comparing event‐free survival as the primary end point during short‐ and long‐term follow‐up and the secondary end point during long‐term follow‐up.

*Primary: recurrent ischemic stroke within 3 months (A) and 12 months (B). **Secondary: a composite of deaths from any cause or hospitalizations for any cause or recurrent ischemic stroke (C) or arrhythmia‐related events or hospitalizations (D).

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis of the Primary Outcome (12‐Month Follow‐Up)

| Recurrent IS poststroke at 12 mo | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.072 | 0.972–1.184 | 0.165 | |||

| Men | 2.122 | 0.441–10.218 | 0.348 | |||

| Paroxysmal AF | 1.774 | 0.444–7.094 | 0.418 | |||

| Body mass index | 0.850 | 0.683–1.056 | 0.143 | |||

| Use of NOAC | 0.825 | 0.103–6.598 | 0.856 | |||

| Creatinine | 0.742 | 0.139–3.954 | 0.727 | |||

| NIH stroke scale | 1.105 | 1.011–1.206 | 0.027 | 1.099 | 1.001–1.206 | 0.047 |

| CHA2DS2VASc score | 1.395 | 0.880–2.212 | 0.157 | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 1.603 | 0.200–12.814 | 0.657 | |||

| Hypertension | 0.955 | 0.239–3.818 | 0.948 | |||

| Diabetes | 1.674 | 0.449–6.234 | 0.443 | |||

| Vascular disease | 7.735 | 1.934–30.933 | 0.004 | 6.399 | 1.574–26.020 | 0.010 |

| Early rhythm control | 0.251 | 0.063–1.003 | 0.050 | 0.215 | 0.052–0.894 | 0.035 |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; CHA2DS2VASc, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years (2 points), type 1 or 2 diabetes, stroke or transient ischemic attack or thromboembolism (2 points), vascular disease (prior myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, or aortic plaque), aged 65–75 years, sex category (female); HR, hazard ratio; IS, ischemic stroke; NIH, National Institutes of Health; and NOAC, nonvitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant.

Secondary End Points and Adverse Arrhythmia Events

The secondary end points were a composite of deaths from any cause or unplanned hospitalizations from any cause or recurrent IS. There were no significant differences in the composite outcomes between the groups, regardless of the follow‐up duration: 19 (10.7%) versus 10 (10.5%) (HR, 0.995; P=0.990 within 3 months) or 25 (14.0%) versus 16 (16.8%) (HR, 0.808; P=0.505 within 12 months) (Table 2). In addition, the results of the per‐protocol and on‐treatment analyses were consistent with the intention‐to‐treat analysis (Tables S2 and S3). The proportion of sustained AF was lower in the early rhythm control group than the usual care group (60 [34.1%] versus 59 [62.8%], P<0.001) at 12 months, and the AF duration during the 12 months was shorter in the early rhythm control group (3.0 months [1.0–9.0] versus 7.0 months [1.0–12.0], P=0.002) (Table 2). However, adverse arrhythmia events within 12 months were relatively more frequent in the early rhythm control group. Adverse arrhythmia events included pacemaker implantations for underlying sick sinus syndrome (permanent or temporary pacemaker in 4 patients) and syncope (1 patient). When considering the time sequence, the early rhythm control group did not experience any significantly different effects on the composite outcome (25 [14.0%] versus 16 [16.8%]; HR, 0.808 [P=0.504 by log‐rank test]) (Figure 2C) or adverse arrhythmia events (5 [2.8%] versus 1 [1.1%]; HR, 2.565 [P=0.372 by log‐rank test]) as compared with the usual care group (Figure 2D). A multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that the conventional risk factors, including a greater age (HR, 1.062; 95% CI, 1.012–1.114 [P=0.014]) and high NIH stroke scale score (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.034–1.129 [P<0.001]), were associated with secondary outcomes within 12 months, but early rhythm control was not (P=0.635, Table S5). There was no difference in the secondary outcomes (mainly complication, composite outcome) of early rhythm control according to AF type and sex (Table S4). The subgroup analyses for the primary and secondary outcomes are shown in Figure S2. Each subgroup had similar clinical tendencies, regardless of the clinical factors.

Discussion

Main Findings

The urgent and strict control of the cause after an acute stroke is of primary importance for preventing recurrent IS. However, early rhythm control of AF, which is the most common cause of cardiogenic emboli, is not performed routinely because of concern about adverse events. This study showed that early rhythm control during the acute stage of a stroke did not increase the risk of adverse events within 3 months but rather reduced the risk of recurrent strokes over 12 months. Although adverse arrhythmic events tended to be more frequent in the early rhythm control group than the usual care group, this effect was mostly related to underlying sinus node dysfunction, which was successfully treated by a pacemaker implantation. Early rhythm control of AF during the acute stage of an IS did not increase the frequency of the composite adverse outcomes, such as mortality or hospitalizations.

Current Guidelines for Preventing Recurrent Strokes in Patients With AF

Strokes are a major event that increase the risk of mortality among patients with cardiovascular disease. As the elderly population increases, the prevalence of strokes is also increasing. 17 According to the 2020 statistics for heart disease and strokes published by the American Heart Association (AHA), ≈15% of patients with strokes have a history of a previous transient ischemic attack, and ≈30% of the transient ischemic attacks were diagnosed as strokes by diffusion‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging. 17 A stroke is the most important risk factor for a recurrent stroke, and 3% to 17% of recurrent IS appear to occur early, within 3 months of the initial stroke. 5 , 6 , 18 , 19 The first month is associated with the highest risk of a recurrent IS. 2 , 5 Therefore, the current guidelines recommend active control of blood pressure, diabetes, associated coronary artery disease, and heart failure within the first 3 months of an acute IS. 11 However, it is uncertain whether the early rhythm control of AF is beneficial for this patient group.

The recent EAST‐AFNET 4 trial showed that early rhythm control of AF results in a greater reduction in cardiovascular risk as compared with usual care. 20 However, there was no prior evidence that starting early AF rhythm control was safe or not during the acute, risky stage of an IS. Therefore, early rhythm control has not been routinely performed after the detection of AF, in addition to the use of anticoagulation, according to AHA/American Stroke Association guidelines. 11

Efficacy and Safety of Early Rhythm Control in Patients With Acute Stroke

There are 2 notable points regarding the efficacy and safety of early rhythm control. In patients with an acute stroke, clinicians should focus on examining: (1) how often adverse events related to early rhythm control occur, and (2) whether rhythm control for AF is effective for preventing the recurrence of IS. In the early rhythm control group, symptomatic bradycardia or syncope occurred during AAD use in 3% of the patients and was associated with underlying sinus node dysfunction. However, no other significant adverse effects related to AADs, cardioversion, or catheter ablation were observed in this study. Active rhythm control of AF by methods such as catheter ablation, with appropriate anticoagulation, has been consistently demonstrated to reduce the risk of IS in recent studies. 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 Recurrent stroke prevention by early rhythm control was not significant at 3 months but appeared significant at 12 months after an IS because the AADs were not successful in restoring and maintaining sinus rhythm in patients with AF. However, active rhythm control by consecutive cardioversions or catheter ablation in patients who failed rhythm control with AADs reduced AF burden for 12 months, as well as the risk of a stroke recurrence. When considering the slow improvement in mRS after stroke, real AF burden during 12 months is thought to be more important. In fact, the early rhythm control group showed a shorter AF detection period in the consecutive Holter after stroke (Table 2). As rhythm control was started after 2 months in 19 (17.9%) of the patients in the usual care group, the long‐term clinical outcomes depending on the rhythm status should be examined in longer‐term follow‐up studies.

Clinical Implications

Defining stroke subtypes is an important consideration for recurrent stroke prevention. IS accounts for ≈88% of strokes, among which cardiogenic embolisms or cryptogenic strokes account for 50%. 17 It is thus important to actively detect AF during the first 3 months after a stroke and start anticoagulation and consider rhythm control if AF is detected. 11 However, most physicians hesitate to start rhythm control during the acute stage of an IS because of concern about the risk and cardiovascular events associated with the use of AADs. 25 , 26 In this current trial, early rhythm control with AADs did not increase all‐cause mortality or cardiovascular events, even in patients in the acute stage. Therefore, the collaboration between neurologists and cardiologists significantly improved the patient outcomes.

Limitations

This study was a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. In addition, to actively detect AF in patients with stroke, continuous ECG monitoring was performed for the first 72 hours, according to the current guidelines. Nevertheless, it was not possible to perform continuous ECG monitoring after the early rhythm control in all patients with stroke with AF because of patient refusal of implantable loop recorders or cardiac implantable electronic devices. Therefore, according to the guidelines, this study performed Holter monitoring on an outpatient or a regular basis, and ECG tests were frequently performed when symptoms appeared. In addition, the use of antiplatelet or antithrombotic agents varied depending on the characteristics of the patient, which may have affected the incidence of primary outcomes. Since this is not a double‐blind study, there is a possibility that the early rhythm group received more aggressive drug treatment to prevent stroke recurrence. Finally, the proportion of patients who underwent electrical cardioversion or catheter ablation was low, so the ability to analyze the effects of strict rhythm control was limited. Although the majority of patients underwent transesophageal echocardiography or cardiac computed tomography to exclude intracardiac thrombi, patients aged >80 years were excluded. Therefore, the results of this study cannot be generalized to all patients with acute strokes and AF.

Conclusions

In patients with acute strokes and AF, early rhythm control within 2 months reduced sustained AF and recurrent IS within 12 months without increasing the composite adverse outcomes, including mortality and hospitalizations.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by grants HI19C0114 and HI21C0011 from the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, and grants NRF‐2020R1A2B01001695 and NRF‐2017R1E1A1A01078382. In addition, this work was supported by the Korea Medical Device Development Fund grant funded by the Korea government (the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, the Ministry of Health & Welfare, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety) (project number: 9991006899, KMDF_PR_20200901_0234, NTIS, KMDF‐RnD 202014X28‐00). The funders had no role in the design or conducting the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the article; and decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

List of RAFAS Investigators

Tables S1–S5

Figures S1–S2

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr John Martin for his linguistic assistance.

A complete list of the RAFAS Investigators can be found in the Supplemental Material.

Supplemental Material for this article is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.121.023391

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

References

- 1. Kleindorfer D, Panagos P, Pancioli A, Khoury J, Kissela B, Woo D, Schneider A, Alwell K, Jauch E, Miller R, et al. Incidence and short‐term prognosis of transient ischemic attack in a population‐based study. Stroke. 2005;36:720–723. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000158917.59233.b7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Das SR, et al; American Heart Association Council on E, Prevention Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S . Heart disease and stroke statistics‐2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tayal AH, Tian M, Kelly KM, Jones SC, Wright DG, Singh D, Jarouse J, Brillman J, Murali S, Gupta R. Atrial fibrillation detected by mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry in cryptogenic TIA or stroke. Neurology. 2008;71:1696–1701. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000325059.86313.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Elijovich L, Josephson SA, Fung GL, Smith WS. Intermittent atrial fibrillation may account for a large proportion of otherwise cryptogenic stroke: a study of 30‐day cardiac event monitors. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;18:185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2008.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu CM, McLaughlin K, Lorenzetti DL, Hill MD, Manns BJ, Ghali WA. Early risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2417–2422. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giles MF, Rothwell PM. Risk of stroke early after transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:1063–1072. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70274-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta‐analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:857–867. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, Brandes A, Eckardt L, Elvan A, Fetsch T, van Gelder IC, Haase D, Haegeli LM, et al. Early rhythm‐control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1305–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2019422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, Castella M, Diener HC, Heidbuchel H, Hendriks J, et al, Group ESCSD . 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2893‐2962. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Furie KL, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task force on clinical practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society in collaboration with the society of thoracic surgeons. Circulation. 2019;140:e125–e151. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, Biller J, Brown M, Demaerschalk BM, Hoh B, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50:e344–e418. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al‐Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981–992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Halperin JL, Waldo AL, Ezekowitz MD, Weitz JI, Spinar J, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2093–2104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, Conti JB, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, et al. AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;2014:e1–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Delling FN, et al; American Heart Association Council on E, Prevention Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S . Heart disease and stroke statistics‐2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e139–e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen‐Huynh MN, Giles MF, Elkins JS, Bernstein AL, Sidney S. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369:283–292. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60150-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, Sidney S. Short‐term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA. 2000;284:2901–2906. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, Brandes A, Eckardt L, Elvan A, Fetsch T, van Gelder IC, Haase D, Haegeli LM, et al. Early rhythm‐control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1305–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2019422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Srivatsa UN, Danielsen B, Amsterdam EA, Pezeshkian N, Yang Y, Nordsieck E, Fan D, Chiamvimonvat N, White RH. CAABL‐AF (California study of ablation for atrial fibrillation): mortality and stroke, 2005 to 2013. Circ: Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018;11:e005739. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.117.005739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saliba W, Schliamser JE, Lavi I, Barnett‐Griness O, Gronich N, Rennert G. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation is associated with reduced risk of stroke and mortality: a propensity score‐matched analysis. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:635–642. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Packer DL, Mark DB, Robb RA, Monahan KH, Bahnson TD, Poole JE, Noseworthy PA, Rosenberg YD, Jeffries N, Mitchell LB, et al. Effect of catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic drug therapy on mortality, stroke, bleeding, and cardiac arrest among patients with atrial fibrillation: the cabana randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:1261–1274. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Friberg L, Tabrizi F, Englund A. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation is associated with lower incidence of stroke and death: data from Swedish health registries. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2478–2487. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, Domanski MJ, Rosenberg Y, Schron EB, Kellen JC, Greene HL, Mickel MC, Dalquist JE, et al; Atrial Fibrillation Follow‐up Investigation of Rhythm Management I . A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1825–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saksena S, Slee A, Waldo AL, Freemantle N, Reynolds M, Rosenberg Y, Rathod S, Grant S, Thomas E, Wyse DG. Cardiovascular outcomes in the AFFIRM trial (Atrial Fibrillation Follow‐Up Investigation of Rhythm Management). An assessment of individual antiarrhythmic drug therapies compared with rate control with propensity score‐matched analyses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1975–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of RAFAS Investigators

Tables S1–S5

Figures S1–S2