Abstract

The repeated, rapid and often pronounced patterns of evolutionary divergence observed in insular plants, or the ‘plant island syndrome’, include changes in leaf phenotypes, growth, as well as the acquisition of a perennial lifestyle. Here, we sequence and describe the genome of the critically endangered, Galápagos-endemic species Scalesia atractyloides Arnot., obtaining a chromosome-resolved, 3.2-Gbp assembly containing 43,093 candidate gene models. Using a combination of fossil transposable elements, k-mer spectra analyses and orthologue assignment, we identify the two ancestral genomes, and date their divergence and the polyploidization event, concluding that the ancestor of all extant Scalesia species was an allotetraploid. There are a comparable number of genes and transposable elements across the two subgenomes, and while their synteny has been mostly conserved, we find multiple inversions that may have facilitated adaptation. We identify clear signatures of selection across genes associated with vascular development, growth, adaptation to salinity and flowering time, thus finding compelling evidence for a genomic basis of the island syndrome in one of Darwin’s giant daisies.

Subject terms: Evolutionary genetics, Genome evolution, Plant evolution, Evolutionary ecology

Many island plant species share a syndrome of characteristic phenotype and life history. Cerca et al. find the genomic basis of the plant island syndrome in one of Darwin’s giant daisies, while separating ancestral genomes in a chromosome-resolved polyploid assembly.

Introduction

As European naturalists set sail to explore the world, the distinctiveness of insular species stood out from the remaining biota. The collections carried out in the Galápagos, Cape Verde and Malay archipelagos were key for the development of the theory of natural selection1 and biogeography2. More recently, Ernst Mayr’s work, which set the scene for the modern synthesis3, focused heavily on island biota4. The central role of remote archipelagos in our understanding of evolution is not coincidental. Organisms colonising these regions encounter highly distinct microenvironments that provide abundant ecological niches and thus ideal conditions for rapid and pronounced phenotypic change5. The ‘island syndrome hypothesis’ predicts the repeated and pronounced phenotypic shifts that some species undergo after colonising islands, as a result of a specific set of environmental conditions6. While the island syndrome hypothesis has been well established6,7, its integration with genomic evidence still lags. For instance, the changes in body size observed in insular animal lineages, when compared to their continental counterparts, are the textbook example of an island syndrome (e.g., pygmy mammoths and giant tortoises), however, to the extent to which these changes are hereditary (genetic) or induced by different food sources (diet) has yet to be documented for many lineages. Considering the rapid nature of these changes, it can be expected that rearrangements in genome structure contribute to the adaptation to novel environmental conditions.

Because the most prominent examples of island syndromes feature animal lineages, our understanding of these phenomena in plants lags7. As plants colonise archipelagos, they typically undergo shifts in leaf phenotypes, overall size, woodiness, lifespan and have an altered dispersal ability—the plant island syndrome7. This is well exemplified by the iconic, yet understudied, daisies in the genus Scalesia8–11. This group consists of ca. 15 species, which have colonised moist forests, littoral zones, arid zones, dry forests, volcanic soils, lava gravels and fissured environments across varied elevations8,12. The phenotypic changes undergone by Scalesia include an increased woodiness, leaf-morphology variation, simplified inflorescences, increased growth rates, and gigantism—as expected by the plant island syndrome. Indeed, this outstanding phenotypic and ecological variation has led authors to refer to this group as the ‘Darwin finches of the plant world’13. All Scalesia species are ancestrally tetraploid (2n = 4x = 68)14,15, and the polyploid genetics may have provided the genetic grist for the diversification, as suggested for island floras16.

In this work, we describe a high-quality chromosomal reference genome assembly and annotation for Scalesia atractyloides, an endemic plant to the Santiago Island, Galápagos. This species was selected because it is critically endangered and has low genomic heterozygosity suitable for de novo assembly9. A chromosome-resolved assembly has allowed us to identify and separate the two ancestral genomes that united in the polyploidization event, and to compare gene and transposable element distribution across and between these subgenomes. Annotation of genes using PacBio IsoSeq RNA afforded a high-quality annotation of the genome, and the detection of selection and gene-family expansions that implicate the genomic basis for island syndrome traits in this charismatic group of plants.

Results and discussion

Genome assembly, annotation and quality control

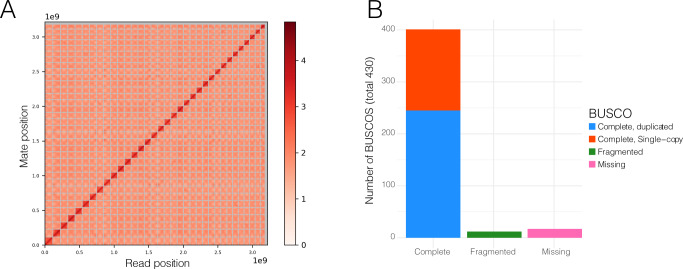

The Scalesia atractyloides genome assembly is highly contiguous (Fig. 1A), consisting of 3,216,878,694 base pairs (3.22 Gbp) distributed over 34 chromosome models, in line with previous cytological evidence11,17,18. The N90 was of 31, corresponding to all but the three smallest chromosomes (n = 34) and L90 was 81.66 Mbp. Flow cytometry estimates (Supplementary Information; Supplementary Table 01), however, suggest a genome size of ca. 3.9 Gbp, and thus ~700 Mbp were likely collapsed by the assembler or removed by purgehaplotigs19. Despite the likely collapse of repeats, we were able to annotate 76.22% of the genome as repeats, which were masked by RepeatMasker (~2.5 Gbp). Considering the whole genome, 47.9% of the genome was composed of long-terminal repeat (LTR) retroelements, of which 16.2% were Copia and 31.54% Gypsy elements (Supplementary Information; Supplementary Table 02), and 26.32% were unclassified repeats.

Fig. 1. Chromosome-resolved assembly of the Scalesia atractyloides nuclear genome.

A Link density histogram, with 34 linkage groups (chromosome models) identified by contiguity ligation sequencing. The x and y axes show mapping positions of the first and second read in read pairs. B Viridiplantae BUSCO set, which offers a characterisation of conserved orthologue genes.

The IsoSeq transcriptome recovered 46,375 genes and 224,234 isoforms (Supplementary Information; Supplementary Fig. 01). Using this RNA as evidence and ab initio models, we retrieved 43,093 genes from the annotation. Of the 430 Viridiplantae odb10 BUSCO groups used in a search of the genome (Fig. 1B), 401 were found as complete (93.3%), of which 245 were found as duplicate (57%) and 156 as a complete and single copy (36.3%), and 12 as fragmented (2.8%). Only 17 were absent (3.9%). When running OrthoFinder including Scalesia and five other Asteraceae chromosome-resolved assemblies, we found that 34% of all the orthogroups included genes from the five genomes, indicating a high-quality gene annotation (Supplementary Information; Supplementary Fig. 02). The proportion of annotated repeats and the number of genes is within the variation reported for Asteraceae. As an example, the closely related sunflower (Helianthus annuus) reference genome includes ~52,000 protein-coding genes and has a repeat content of 74%20 the lettuce genome includes 74% repeats and ~39,000 protein-coding genes21 and the Hawaiian Bidens genome has 70–74% repeats22.

Subgenome identification and evolution

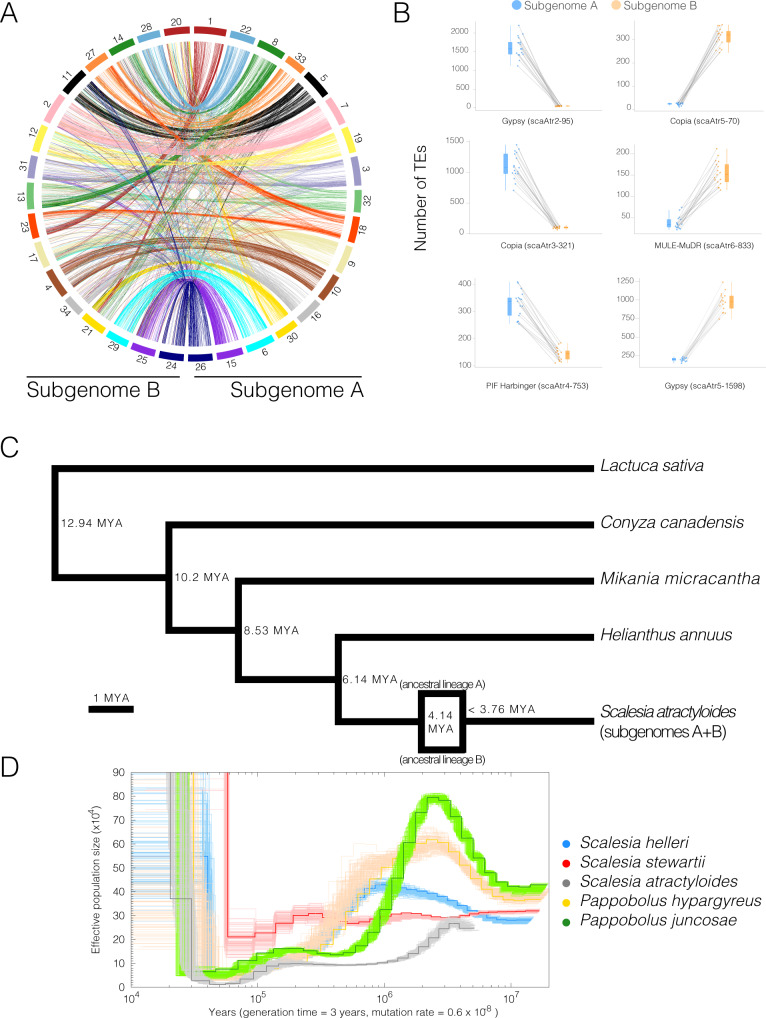

The identification of subgenomes (subgenome A and subgenome B; Fig. 2A) was carried out in two steps. In the first step, we assigned the 34 chromosomes into 17 homeolog pairs by identifying and mapping 1061 duplicated conserved orthologous sequences (COS; Supplementary Information; Supplementary Table 03). While this first step identified chromosome pairs (homeologs), it did not facilitate the assignment of subgenome identity within pairs. Homeolog exchanges23 are therefore not a concern at this point. In the second step, we used the k-mer spectrum to identify ‘fossil transposable elements’ that were actively replicating while the two subgenomes were separated (i.e. before the polyploidization event). Since different genomes accumulate different transposable elements, we hypothesised that some transposable elements should be differentially distributed in different subgenomes24,25. In short, transposable element families active before the divergence of the two ancestral lineages (lineages A and B) are predicted to be approximately equally represented in both subgenomes, whereas transposable elements active after the divergence of the parental species and before the polyploidization event, are predicted to be differently represented within subgenomes. Using the k-mer spectrum, we selected 13-mers that: (i) were highly abundant, specifically, present at least 100 times in the genome. By selecting highly abundant genomic regions, we obtain genomic regions representing repeats/TEs; (ii) were unevenly represented between chromosome pairs (identified in the previous step). By selecting differentially represented 13-mers, we obtained a set of TEs/repeats which were active during the separation period (ancestral lineages A and B). were obtained using Jellyfish and a combination of in-house scripts, and we ended up with an average of 361 13-mers per chromosome pair (max = 934, min = 182, SD = 179). Using this selection of 13-mers, we ran a hierarchical clustering algorithm that grouped chromosomes into two clusters (two subgenomes; Supplementary Information; Supplementary Fig. 04). To clarify these assignments and, in particular, the occurrence of differentially represented transposable element families, we explored the output from RepeatMasker by plotting transposable element families unevenly represented across subgenomes (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Data 4 and Supplementary Fig. 05). The identification of differently represented transposable element families further provides compelling evidence that the Scalesia radiation is of allopolyploid origin, confirming chromosome counts15. Island floras are characterised by a high frequency of paleoallopolyploids (i.e. old allopolyploids)26, and the genetic variation made available at higher ploidy levels may underpin the diversification to multiple environments (Julca et al.27; te Beest et al.28)—a scenario which is in line with the evolutionary history of Scalesia.

Fig. 2. Subgenomes and evolutionary history of Scalesia.

A Circos plots displaying the 34 chromosome models in the assembly. Pairs are organised to the left and right from the top, and have the same colour coding. B Selected families of transposable elements (TEs) that are differently represented on each subgenome (17 pairwise comparisons; each TE is labelled after the assembly (scaAtr), round and family number (2–95) after RepeatMasker). These TE families were likely active while the two subgenomes were separated, being thus unevenly represented. These highlight subgenome identification. Each data point corresponds to a chromosome in a subgenome (subgenome A in blue and B in orange). Chromosome pairs are linked by grey lines. C Single-copy ortholog phylogeny of the studied Asteraceae genome assemblies. Node ages are provided to the right of each node, as well as the predicted time for the polyploidization event. D Pairwise sequentially Markovian coalescent (PSMC) estimation of the demographic history of Scalesia atractyloides, two other Scalesia species, and two members of the Pappobolus genus, which is the sister taxon to Scalesia using bootstrapping (100 replicates). PSMC runs for the whole genome and subgenomes yielded similar results (Supplementary Fig. 03).

Using four other chromosome-level assemblies from Asteraceae (Helianthus annuus, Conyza canadensis, Mikania micrantha and Lactuca sativa) and the two S. atractyloides subgenomes, we estimated groups of orthologous genes using OrthoFinder. We obtained 710 orthogroups in which each genome had only a single member, tolerating no missing data, and used this data to construct a phylogenetic tree. The tree topology agrees with the placement of the Asteraceae lineages from a recent and comprehensive set of genomic analyses29. We performed two separate dating analyses: one to date the nodes of the tree (speciation events) and another to date the polyploidization event. To date the nodes of the tree, we constrained the node separating the Scalesia subgenomes and Helianthus at 6.14 Mya (Fig. 2C) following recent literature 289. Consistent with comparisons of Ks distributions (Supplementary Information; Supplementary Fig. 06), a model-based divergence time estimate (r8s) suggests that the ancestral lineages represented in the Scalesia subgenomes diverged at approximately 4.14 Mya. A second dating analysis was performed to date the polyploidization event using LTR retrotransposons. For this analysis, we used LTR retrotransposons which were evenly represented between subgenomes (to capture families active after the polyploidization event), and which were present in Helianthus (Supplementary Information; Supplementary Fig. 07). By comparing genetic divergence (Jukes Cantor distances) between the Scalesia LTR retrotransposons and Helianthus, we estimated that the ancestral genomes reunited in a single-polyploid genome at least 3.76 Mya (Fig. 2C; Supplementary Information; Supplementary Fig. 06). These dates are concordant with the PSMC analysis which roughly indicate that the three Scalesia species had concordant population sizes of 250,000–300,000 circa 4 Mya (Fig. 2D). Mismatches between the three genomes could result from variation in generation time in Scalesia, and bottlenecks suffered by populations as a result of climatic shifts in the Galápagos30. The PSMC estimates are concordant with a recent dating analysis that estimated the divergence between Pappobolus and Scalesia occurred ~3 Mya9.

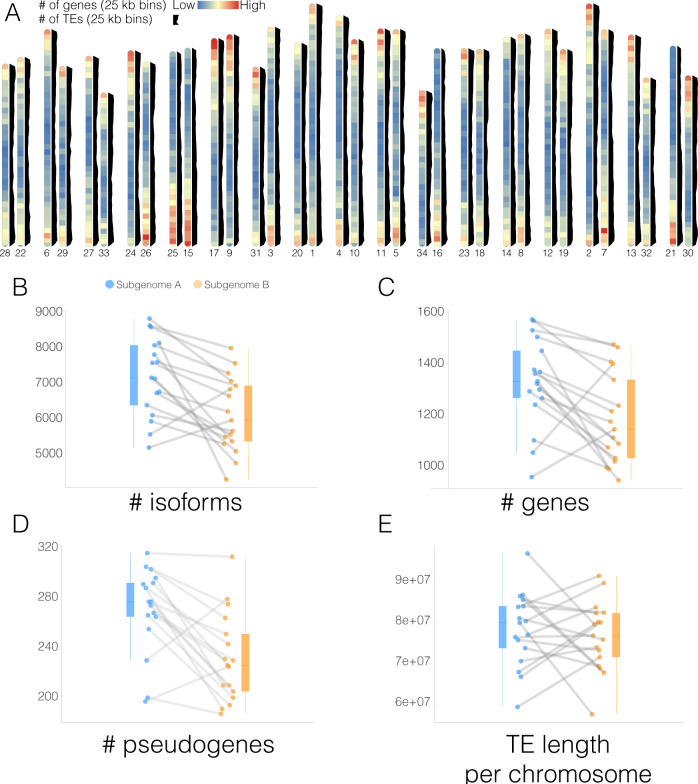

The identification of subgenomes allowed comparing gene and transposable element distribution across homeolog chromosome pairs. We find that gene density is highest near the telomeres on both subgenomes, while transposable elements are more evenly distributed throughout chromosomes (Fig. 3A). This even distribution of transposable elements is different from most other vascular plants, in which transposable element load is highest near the centre and decreases towards the ends of the chromosome, and rather is reminiscent of observations in bryophyte genomes31–33. Even distributions of transposable elements were also observed in the sunflower genome20, which may be indicative of particular transposable element regulation in the Heliantheae. However, these patterns should be confirmed as more Heliantheae genomes are sequenced.

Fig. 3. Subgenome evolution and characterisation.

A Ideogram with gene and transposable element distribution in 25-kbp bins. Gene density is plotted in chromosome representations and transposable element distribution is plotted to the side of each chromosome in black. Chromosomes are arranged in homoelogous pairs. B The number of isoforms detected for each subgenome. Each data point corresponds to a chromosome in a subgenome (subgenome A in blue and B in orange; 17 pairwise comparisons; subgenome A: min = 5176; max = 8817, avg = 7175; Subgenome B: min = 4277; max = 7982, avg = 6103). Chromosome pairs are linked by grey lines. C Number of genes detected for each subgenome (17 pairwise comparisons; subgenome A: min = 1571; max = 1571, avg = 1327; Subgenome B: min = 944; max = 1474, avg = 1181). D The number of pseudogenes detected for each subgenome (17 pairwise comparisons; Subgenome A: min = 196; max = 315, avg = 270; subgenome B: min = 186; max = 312, avg = 230). E Length of transposable elements detected for each subgenome (17 pairwise comparisons; subgenome A: min = 59,440,194; max = 97,142,619, avg = 78,545,717; Subgenome B: min = 57,631,669; max = 91,646,014, avg = 76,870,839).

As two genomes unite to form a single hybrid genome, an accommodation of the two subgenomes, the process of diploidization takes place34–36. This process can occur very quickly, with changes in transcription between subgenomes observed in 2–3 generations37, and result in pronounced changes in gene numbers. Whereas subgenome dominance in gene expression and retention has been documented in paleopolyploid plant genomes38–40, Scalesia subgenomes contain roughly equal gene and isoform contents (Fig. 3B, C), as well as pseudogene numbers and transposable element load (Fig. 3D, E). In addition to this, when running the Viridiplantae BUSCO set for each subgenome separately, we find 82.7% complete BUSCOs on subgenome A (76.6% single copy, 6% duplicates), and 81.9% complete BUSCOs (77% single copy, 4.9% duplicates) on subgenome B. Both subgenomes are roughly the same length (subgenome A = 1,629,251,263 bp; subgenome B = 1,554,170,668 bp), and have retained the same number of chromosomes (Fig. 3A). This indicates that during the past ~3.76 million years, during which the two subgenomes have been unified in the same organism, there has not been a drastic rearrangement of either subgenome relative to the other, despite a smaller accumulation of genes and pseudogenes on subgenome A. This suggests diploidization is slowed down and, to explain this, we speculate that Scalesia’s adaptation to insular environments has benefited from the genetic variation and diversity stemming from the allopolyploidization event41.

Genome rearrangements in Heliantheae

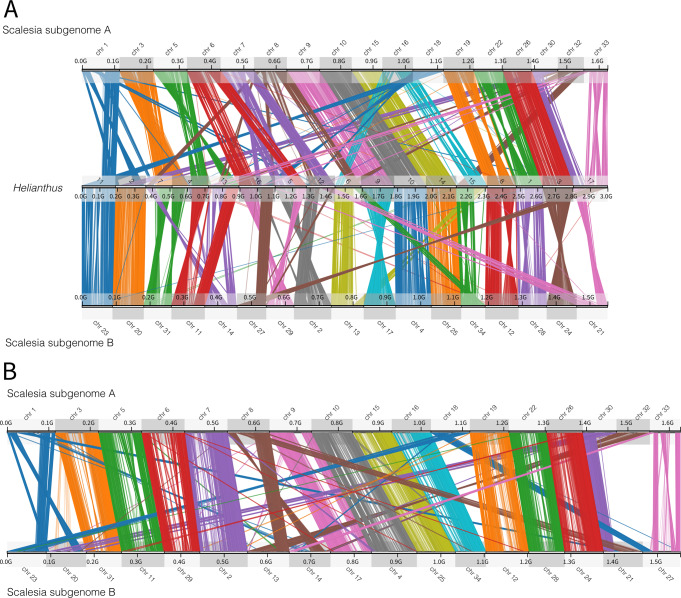

To further dissect the mode and tempo of polyploid subgenome evolution, we used Synolog42 to create chromosome stability plots, which allow us to detect translocations and inversions (Fig. 4). Synolog establishes clusters of conserved synteny by identifying single-copy orthologs shared between two genomes via reciprocal all-by-all BLAST. From the identified synteny clusters, we calculated statistics on the orientation (Forward/Inverted) and chromosome location. We thereby classified genes into four categories: ‘Forward pair’ (FP; i.e. not inverted, and the single-copy orthologs are in chromosomes from the same pair), ‘Inverted pair’ (IP; i.e. inverted, and the single-copy orthologs are in chromosomes from the same pair), ‘Forward translocated’ (FT; i.e. not inverted, and the orthologues are not in chromosomes from the same pair), ‘Inverted translocated’ (IT; i.e. inverted, and the orthologues are not in chromosomes from the same pair). Comparing the two Scalesia subgenomes, we found 4379 FP genes (comprising 111 clusters of 5 or more genes), 5642 IP genes (78 clusters), 747 FT genes (31 clusters), and 1488 IT genes (18 clusters), totalling 12,256 genes included in the analysis (Fig. 4B). In terms of genome length, we classified 1.45 Gbp as FP, 1.15 Gbp as IP, 346.4 Mbp as FT and 343.3 Mbp as IT. Thus, while the majority of the genes have been inverted (7130 genes), a minor fraction of the genome length has been inverted (1.49 Gb). Despite the fact that we were able to identify homeologs and the subgenomes, the synteny plots confirm there are rapid rates of chromosomal rearrangements in the Asteraceae20, and suggest a central role of inversions in the family.

Fig. 4. Chromosome stability plots.

These reveal the role of inversions and translocations in the differential in each subgenome. A Chromosome stability plot between the two Scalesia subgenomes and the Helianthus annuus genome. Each line connects a pair of orthologous genes, colour-coded by chromosome pair. B Chromosome stability between the two Scalesia subgenomes. Each line connects orthologous genes in subgenomes A and B, colour-coded by chromosome pair.

Evidence for the island syndrome

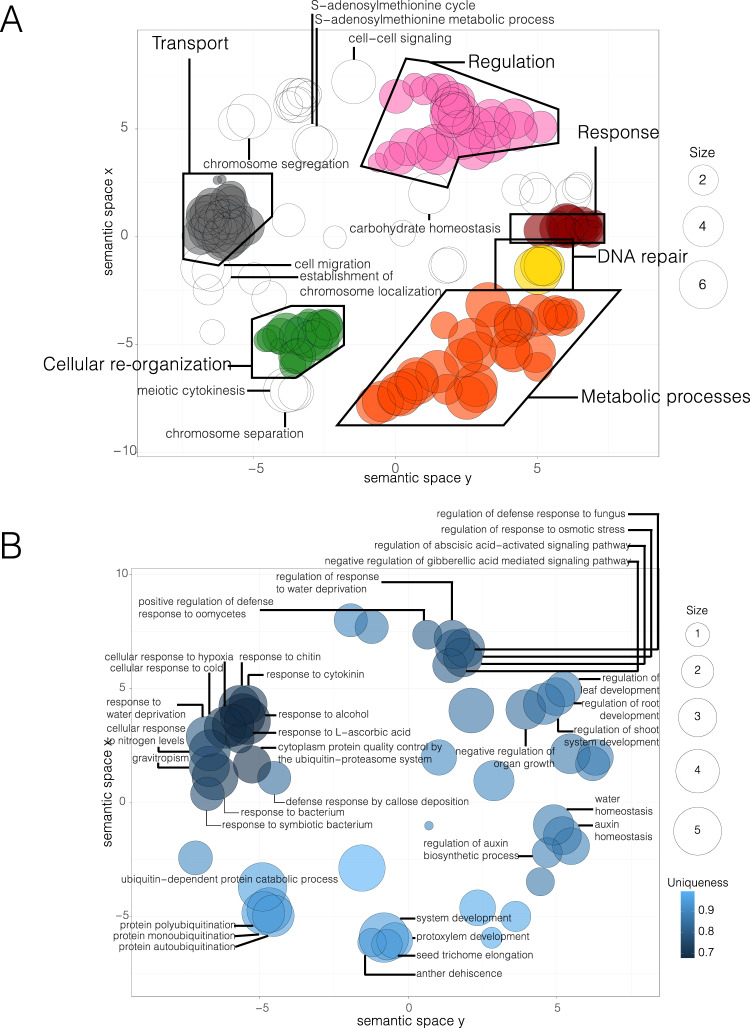

We identified 920 genes under selection (P < 0.05) in the Scalesia genome (478 on subgenome A and 442 on subgenome B), after correcting dN/dS ratios using a Holm–Bonferroni FDR correction. To understand their function we took two approaches, one generalistic using GO enrichment analysis, and a more detailed one where we randomly selected 100 genes (Supplementary Data 1), called Arabidopsis orthologs and read the literature for those genes. Before this analysis, we confirmed that the selection of 100 random genes did not bias the final results by comparing a GO analysis using the 920 genes (Fig. 5A) with a GO analysis with only 100 genes. Subsampling did not bias the major categories. First, we extracted the functional annotation using a Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis, and the results were visualised using Revigo. Revigo organised GOs onto groups, which we coloured and named: metabolic processes (Fig. 5A, orange group), cellular reorganisation (green group), DNA repair (yellow group), response to protein folding (maroon group), and regulation (regulation of metabolic processes, translation, gene expression, translation, nuclear division, chromosome segregation, among others; pink group; Fig. 5A; Supplementary Information; Supplementary Data 2 and 3). Genes inferred to have evolved under positive selection are also associated with meiosis, chromosome arrangement and chromatin status (meiotic cytokinesis, the establishment of chromosome location, chromosome separation and chromosome segregation, among other GO classifications; Fig. 5A, Supplementary Information; Supplementary Data 2 and 3), and this may indicate selection at genes associated with the coexistence of two genomes.

Fig. 5. Positive selection and gene-family expansion across the Scalesia atractyloides genome.

A GO term enrichment of the genes under selection across the genome. GO terms assigned to at least four genes are labelled. Size refers to the number of genes associated with a particular GO term. B GO term enrichment of the genes belonging to expanded gene families across the genome according to a CAFE analysis. Only GOs within a group of three or more overlapping circles are included. Uniqueness measures the degree to which a particular GO term is distinct relative to the whole list.

Considering the astonishing leaf phenotypic variation in the Scalesia lineage, it is particularly interesting that we detected selection on potential regulators of leaf morphology, including genes well known to determine leaf cell number in A. thaliana (E2F1)43,44, cell fate in leaves (YABBY5)45,46, leaf senescence (RANBPM, LARP1C, PEN3)47–49, leaf variegation (THF1)50,51 and leaf growth (PAC)52–54. It has been observed that Scalesia plants grown in shaded conditions, as opposed to the continuous direct light provided by their open Galápagos landscape habitats, show substantially retarded growth55. Thus it is interesting to note that many Scalesia genes under selection are affected by light stimulus. A STRING analysis showed that there was a selection at multiple points in the light regulatory pathways including responses to R/FR and blue light responses (Supplementary Fig. 08). These include an inhibitor of red and far-red light photoreceptor (PHL)56,57, a lysine-tRNA ligase that regulates photomorphogenic responses58, an amino acid aminotransferase-like PLP-dependent enzymes superfamily protein that is regulated under light conditions and is associated with the photorespiration process59,60, and genes for which knock-out mutants experience alterations in light reception (DJC69, COX15; Supplementary Data 1)61,62.

Many of the stress-response genes under selection in Scalesia are associated with osmotic stress in A. thaliana, concomitant with evidence that the Scalesia atractyloides habitat is characterised by arid conditions such as the Galápagos’ arid zone, littoral zone, and fissured lava areas8,12. For instance, we identified selected genes (‘Leucine-rich repeat protein kinase family protein’, MPPBETA, ‘leaf osmotic stress elongation factor 1-β–1’, AT2G21250, VAP27-1) associated with osmotic stress63–68, as well as heat shock proteins and regulators of stomatal closure (THF1)50,51 (Supplementary Data 1). Other stress-associated genes under selection include those involved in response to high irradiation (ZAT10, AT1G06690, DDB2)69–74.

Some genes under selection are associated with growth and transitions between life stages. Scalesia plants’ fast rates of growth have earned them the name ‘weedy trees’, and these genes may regulate these plants’ exceptionally fast growth and tree-like habits. We find three genes under selection that cause the transition between embryonic and vegetative traits (RING1A, SWC4, ABCI20)75, and four genes that regulate flowering time in A. thaliana (ELF8, RING1A, Short-Vegetative-Phase, NRP1)76–80, and height or size of the plant (CLAVATA, GH9C2, ELF8, NSL1, TUA6)81–90.

Finally, we assessed the expansion and contraction of gene families in the Scalesia genome, finding a total of 37 significantly contracted families and 26 significantly expanded families (Fig. 5B). GO enrichment testing of the expanded families uncovered significantly enriched functions associated with vascularisation (secondary cell wall biogenesis, shoot system development, negative regulation of organ growth, xylem vessel member cell differentiation, protoxylem development), likely associated with plant growth in Scalesia9. We also find evidence of evolutionary responses to aridity and changes in osmotic pressure in significantly expanded families (regulation of stomatal closure, response to water deprivation, response to osmotic stress, water homoeostasis), similar to the genes under selection (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, we detect contraction in gene families with GO terms associated with tree habits (shoot system development, regulation of organ growth, regulation of root development, xylem vessel member cell differentiation, gravitropism), adaptation to arid environments (water deprivation, stomatal closure, regulation to osmotic stress) and cold tolerance (cellular response to cold; Supplementary Information; Supplementary Tables 09–14). While this may seem contradictory, it suggests that different families have redundant functions, and the expansion of a family may lead to redundancy in another family and consequent gene loss through the pseudogene formation.

In this study, we were able to elucidate patterns of genome evolution in a critically endangered species (Scalesia atractyloides) of Darwin’s giant daisy tree radiation by attaining a chromosome-resolved genome and by subsequently identifying two ancient genomes underlying its polyploid state. We found that both subgenomes retain a relatively similar number of genes as well as other genetic features, such as pseudogenes and transposable elements, which lead us to speculate on the role of insular evolution underlying these changes. Moreover, we uncovered the role of inversions in gene accumulation, suggesting these may have played an important role in the maintenance of genes in subgenomes, and found a relatively unique pattern of transposable element accumulation within flowering plants which warrants further attention. Expanded gene families and genes under positive selection indicate the first solid evidence for genomic island syndrome in a plant, revealing an underlying genomic basis of the outstanding leaf and growth phenotypic variation in Scalesia. This phenotypic variation may also have been facilitated by the substantial presence of transposable elements and by ploidy.

Methods

Plant material, flow cytometry, DNA extraction, library preparation and sequencing

Tissues used for the de-novo genome assembly and annotation were sampled from living Scalesia atractyloides plant P2000-5406/C2834 cultivated in the greenhouse of the University of Copenhagen Botanical Garden collections. This plant was originally germinated from a seed collected from Santiago Island. Fresh tissue was collected and flash-frozen in dry ice or liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80 °C for later use.

To assist with sequencing coverage strategy and to inform genome assembly, we obtained estimates of genome size using flow cytometry following91. Briefly, 50 mg of freshly collected leaves from the sample material and from the reference standard (Solanum lycopersicum ‘Stupické’; 2 C = 1.96 pg92; were chopped with a razor blade in a Petri dish containing 1 ml of Woody Plant Buffer93. The nuclear suspension was filtered through a 30-µm nylon filter, and nuclei were stained with 50 mg ml−1 propidium iodide (PI) (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland). Fifty mg ml−1 of RNase (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was added to the nuclear suspension to prevent staining of double-stranded RNA. After a 5-min incubation period, samples were analysed in a Sysmex CyFlow Space flow cytometer (532 nm green solid-state laser, operating at 30 mW). At least 1300 particles in G1 peaks were acquired using the FloMax software v2.4d94. The average coefficient of variation for the G1 peak was below 5% (mean CV value = 2.72%). The holoploid genome size in mass units (2 C in pg; sensu95 was obtained as follows: sample 2 C nuclear DNA content (pg) = (sample G1 peak mean/reference standard G1 peak mean) * genome size of the reference standard. Conversion into basepair numbers was performed using the factor: 1 pg = 0.978 Gbp96. Three replicates were performed on two different days, to account for instrumental artefacts.

The commercial provider Dovetail Genomics extracted and purified high-molecular-weight DNA from flash-frozen leaf tissue using the CTAB protocol, and the concentration of DNA was measured by Qubit. For long-read sequencing, they constructed a PacBio SMRTbell library (~20 kb) using the SMRTbell Template Prep Kit 1.0 (PacBio, CA, USA) following the manufacturer recommended protocol. This library was bound to polymerase using the Sequel Binding Kit 2.0 (PacBio) and loaded onto the PacBio Sequel sequencing machine using the MagBeadKit v2 (PacBio). Sequencing was performed on the PacBio Sequel SMRT cell, using Instrument Control Software v5.0.0.6235, Primary analysis software v5.0.0.6236, and SMRT Link Version 5.0.0.6792. PacBio sequencing yielded 41,322,824 reads, resulting in a total of 197-fold coverage of the nuclear genome. For contiguity ligation, they prepared two Chicago libraries as described in ref. 97. Briefly, for each Dovetail Omni-C library, chromatin is fixed in place with formaldehyde in the nucleus and then extracted. Fixed chromatin was digested with DNAse I, and chromatin ends were repaired and ligated to a biotinylated bridge adapter followed by proximity ligation of adapter-containing ends. After proximity ligation, crosslinks were reversed and the DNA was purified. Purified DNA was then treated to remove biotin that was not internal to ligated fragments. Sequencing libraries were generated using NEBNext Ultra enzymes and Illumina-compatible adapters. Biotin-containing fragments were isolated using streptavidin beads before PCR enrichment of each library. These libraries were then sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument, producing a total of 1,463,389,090 sequencing reads.

To obtain RNA transcript sequences for annotation of the genome, we extracted RNA from five tissues (root, stem, young leaf, old leaf, and floral head) of a S. atractyloides plant P2000-5406/C2834 using a Spectrum Plant Total RNA Kit (Sigma, USA) with on-column DNA digestion following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA extracts from all five tissues were pooled. mRNA was enriched using oligo (dT) beads, and the first-strand cDNA was synthesised using the Clontech SMARTer PCR cDNA Synthesis Kit, followed by first-strand synthesis with SMARTScribeTM Reverse Transcriptase. After cDNA amplification, a portion of the product was used directly as a non-size-selected SMRTbell library. In parallel, the rest of the amplification was first selected using either BluePippin or SageELF, and then used to construct a size-selected SMRTbell library after size fractionation. DNA damage and ends were then repaired, followed by hairpin adaptor ligation. Finally, sequencing primers and polymerase were annealed to SMRTbell templates, and IsoSeq isoform sequencing was performed by Novogene Europe (Cambridge, UK) using a PacBio Sequel II instrument, yielding 223,051,882 HiFi reads.

Genome assembly and annotation

An overview of the bioinformatic methods is provided in https://github.com/jcerca/Papers/tree/main/scalesia_genome. The genome was assembled using wtdbg298, specifying a genome size of 3.7 Gbp, PacBio Sequel reads, and minimum read length of 5,000. The wtdbg2 assembly consisted of contigs with 3.62 Gbp total length. This assembly was then assessed for contamination using Blobtools v1.1.199 against the NT database, detecting and removing a fraction of the scaffolds. This filtered assembly was used as input to purge_dups v1.1.2, which removed duplicates based on sequence similarity and read depth100, reducing the assembly length to 3.22 Gbp. This assembly and the Dovetail Omni-C library reads were used as input data for HiRise by aligning the Chicago library sequences to the input assembly. After aligning the reads to the reference genome using bwa, HiRise produces a likelihood model for genomic distance between read pairs, and the model was used to identify misjoints, prospective joints, and make joins. After HiRise scaffolding, the N50 increased to 16, and the N90 to 31, corresponding to all but the three smallest chromosomes (n = 34), while the L50 was 94.2 Mbp and the L90 was 81.66 Mbp. The largest scaffold was 116.23 Mbp. In total, HiRise scaffolding joined 1,329 scaffolds. We then used the Assemblathon 2 script (https://github.com/ucdavis-bioinformatics/assemblathon2-analysis)101 to assess assembly quality.

To annotate genes, we first masked repeats and low complexity DNA using RepeatMasker v4.1.1102 using the ‘Asteraceae’ repeat database with Repbase database. After this first round, we ran RepeatModeler v2.0.1103 on the masked genome to obtain a database of de novo elements. This database was subsequently used as input to RepeatMasker for a second round of masking the genome. To find gene models, we first assembled a transcriptome using PacBio HiFi data and following the IsoSeq3 pipeline (Pacific Biosciences). Processing of the RNA data involved clipping of sequencing barcodes (lima v2.0.0), removal of poly(A) tails and artificial concatemers (Isoseq3 refine v3.4.0), clustering of isoforms (Isoseq3 cluster v3.4.0), alignment of the reads to the reference genome using (pbmm2 align v1.4.0), characterisation and filtering of transcripts (SQANTI3 v1.0.0)104. Genome annotation was carried out using the MAKER2 pipeline v2.31.9105,106, using a combination of ab initio and homology-based gene predictions (using Asteraceae protein sets). Since no training gene models were available for Scalesia atractyloides, we used CEGMA107 to train the ab initio gene prediction software SNAP108. In addition to the ab initio features, we used the IsoSeq transcriptome as a training set for the gene predictor AUGUSTUS109, and as direct RNA evidence to MAKER2. Finally, when running MAKER2 we specified, model_org = simle, softmask = 1, augustus_species = arabidopsis and specifying snapphmm to training of SNAP. To assess the quality of the gene models we used BUSCO and the viridiplantae odb v10 set110–112. Further checks of genome annotation quality were done using OrthoFinder with 4 other high-quality Asteraceae genomes (see below; Supplementary Fig. 02).

Demographic reconstruction using PSMC

To complement the S. atractyloides genome, we generated shotgun genomic data from DNA extracts of specimens of S. helleri B. L. Rob. and S. stewartii Riley, as well as the outgroup species Pappobolus hypargyreus and P. juncosae. Briefly, the S. helleri and S. stewartii specimens were extracted with a Qiagen DNeasy 96 Plant Kit, and the P. hypargyreus and P. juncosae extracts were previously reported (Fernández-Mazuecos et al.9). DNA extracts for these four specimens were sent to the commercial provider Novogene for dsDNA library preparation, and they were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq platform in 150-bp PE mode. For these sequence data, we used FastQC v0.11.8 to check for quality of raw reads113, identified adapters using AdapterRemoval v2.3.1, and removed them using Trimmomatic v0.39114,115. These sequences were then aligned to the S. atractyloides genome using the mem algorithm of bwa116, and reads with a mapping quality below 30 were removed, resulting in a final sequencing depth of about ~15×. Alignments were then processed and analysed using PSMC117. Specifically, running PSMC involved calling variants using the bcftools mpileup and call algorithms, considering base and mapping qualities above 30 and read depths above 5118, and posterior processing of the files using fq2psmcfa. For the PSMC run we specified a maximum of 25 iterations, initial theta ratio of 5, bootstrap, and a pattern of “4 + 25*2 + 4 + 6”. To plot files we used the util psmc_plot.pl specifying a generation time of 3 years and a mutation rate of 6e−9, and constrained the y- and x axes to 50 and 20,000,000, respectively.

Determination of subgenomes, and testing for subgenome dominance

The determination of sugenomes involved two steps, the first using conserved portions of the genome (conserved orthologue sets or COS) and the second involving the exploration of k-mer distribution patterns. For the first step, we reasoned that homologous chromosomes would share COS. We used the Compositae-COS as baits (available through github.com/Smithsonian/Compositae-COS-workflow/raw/master/COS_probes_phyluce.fasta119, running phyluce to mine for COS in the genome assembly120,121. This pipeline, however, is designed for single-copy COS, thus we manually modified the python script to return COS that are duplicated in the genome assembly. We then constructed a pairwise matrix of COS assignment using double-copy COS (Supplementary Information; Supplementary Table 03).

Duplicated COS provided a robust determination of chromosome pairings (homeolog chromosomes) but did not reveal which member of the pair belongs to which subgenome. To distinguish this, we performed a second step, where we analysed the k-mer spectrum24. We hypothesised that the period of separation of the two subgenomes led to the accumulation of different repeat content and transposable elements. To quantify k-mer abundance, we ran the software Jellyfish122 for each chromosome independently, thus obtaining the per-chromosome frequency of 13-mers. To ensure we targeted only repeats, we selected 13-mers represented only >100 times represented at any given chromosome. To ensure that we targeted the period of separation (i.e. differential accumulation of TEs as hypothesised above), we compared 13-mer frequencies in homeolog pairs and kept only 13-mers that were at least twice as abundant within one member of each pair (e.g. if 500 counted in one member of the pair, then either <250 or >1000 counted in the other member). Using R, we computed a distance matrix and a hierarchical clustering, which neatly separated members of each pair into two groups (Supplementary Information; Supplementary Fig. 04). Finally, to confirm whether k-mers separated both subgenomes reliably, we repeated the distance matrix and hierarchical clustering analyses with a slight modification: we randomised chromosome pairs. Under a random pairing, we expected to obtain inconclusive results because chromosomes from the same subgenome should not have differentially represented TEs, and therefore subgenome groupings should not occur. Indeed, in line with this expectation, the randomisation of the chromosome pairs yielded inconclusive results.

To confirm the accuracy of subgenome assignment, we took two independent approaches. First, we created a Circos plot using the masked regions of the genome. To produce the Circos plot, we aligned the masked subgenomes to each other using mummer123,124, and plotted the circos using the ‘Circos, round is beautiful’ software125. Second, we studied transposable element representation in each subgenome benefiting from the transposable element identification accomplished using RepeatMasker. Specifically, we obtained the list of different annotated transposable elements from RepeatMasker (e.g. RTE-BovB, LINE-L1, LINE-L2, Helitron, PIF-Harbinger Gypsy, Copia, CRE; Supplementary Data 4), and separated the families within these groups. For each family, we counted the number of elements present on each subgenome, and plotted all the families using raincloud plots126. To visualise genes and transposable elements along chromosomes, we used the R package Ideogram127. After identifying each subgenome, we ran BUSCO separately for each subgenome as a way of understanding subgenome-specific gene loss (Viridiplantae odb10 as specified above).

Evolutionary history of the Scalesia atractyloides subgenomes and comparative genomics

We searched the literature and NCBI for chromosome-level assemblies of the Asteraceae (February 5, 2021), downloading genomes assemblies of sunflower (Helianthus annuus20), the Canada fleabane (Conyza canadensis128), the ‘mile-a-minute’ weed (Mikania micrantha129), and lettuce (Lactuca sativa21). We downloaded the Arabidopsis thaliana genome from TAIR (Arabidopsis.org).

To obtain sets of orthologous genes, we ran OrthoFinder130 on the predicted amino acid sequences (faa) and coding sequences (cds). Before running this software, we selected only the longest isoforms of both files, and removed sequences with stop codons as done by131. On the amino acid sequences we removed sequences with lengths below 30 bp using kinfin’s filter_fastas_before_clustering.py script132. We ran OrthoFinder on various combinations of the genomes, including: (1) All Asteraceae, with subgenomes separated, (S. atractyloides subgenome A, S. atractyloides subgenome B, C. canadensis, H. annuus, L. sativa, M. micrantha); (2) All Asteraceae, and the Scalesia genome (S. atractyloides (complete), C. canadensis, H. annuus, L. sativa, M. micrantha); (3) A. thaliana and subgenomes (S. atractyloides subgenome A, S. atractyloides subgenome B, A. thaliana). A representation of the run including all Asteraceae and the Scalesia genome and its processed results using an upset plot133.

Dating of the speciation and the polyploidization event were performed independently. To date the speciation event, we obtained a phylogenetic tree, by running OrthoFinder with the two subgenomes separately (OrthoFinder run 1, above). OrthoFinder retrieved a tree of the single-copy orthologs, which was used for posterior analysis. This tree was converted as ultrametric using r8s134. To date the nodes of the tree, we converted branch lengths to time estimates using a calibration point of 6.14 Mya between H. annuus and S. atractyloides following recent literature29, following the practice of recent literature9.

Dating the polyploidization event was accomplished by combining the tree obtained by OrthoFinder (OrthoFinder run 1) and depended on transposable element distributions along the subgenomes as previously detailed by24,25,135. Briefly, this approach has a simple assumption: before the speciation event (which separates the ancestral lineages A and B) and after the polyploidization event (which brings the ancestral lineages A and B together), the accumulation of transposable elements will be similar on both subgenomes. In other words, transposable element families that are evenly represented on the subgenomes, therefore, represent the pre-speciation and post-allopolyploidization period. We focused on long-terminal repeats (LTRs) given their prevalence along the genome. To obtain high-quality LTR sequences, we started by using LTRharvest to identify LTR elements136, followed by LTRdigest to process these elements. LTRdigest annotated features such as genes and domains inside LTRs, and helped refine the elements. To find features within the LTRs, we downloaded various PFAM domains provided in ref. 137, and complemented these by downloading and concatenating them with the “Gypsy” and “Copia” domains from the PFAM online database. We converted the domains to HMMs using hmmconvert138, and added HMMs from the Gypsy Database139. The identification and annotation of LTRs using these methods was done for the S. atractyloides and Helianthus annuus genomes, with the inclusion of the latter species serving as an outgroup for comparisons of genetic divergences. An important distinction relates to the LTR-element and the LTR-region: the LTR-element involves the whole transposable element including repeated regions and genes inside, while the LTR-region involves only the Long Terminal Repeat of the LTR-element. For the next analyses, we used only the LTR-region (as provided by LTR digest) as alignments were of better quality. Using LTR-domains of the Scalesia and Helianthus genomes as inputs, we ran OrthoFinder to obtain orthogroups consisting of closely related LTR-domains. We processed the OrthoFinder data by selecting orthogroups that met two assumptions: (1) they were in equal representation on both subgenomes (as hypothesised above); (2) and that were present in Helianthus (to calculate genetic distances, see below). Using orthogroups which met these two assumptions, we aligned orthogroups using mafft, and cleaned poorly aligned regions using Gblocks140,141, with non-stringent options including ‘allow smaller final blocks’, ‘allow gap positions within the final blocks’, and ‘allow less strict flanking regions’. After this, we further processed the data by removing sequences with more than 50% missing data, and re-checked whether numbers of TEs were still balanced between subgenomes, thus purging some further orthogroups. We then re-aligned the data using mafft and inferred a tree for each ortholog. We kept only orthogroups where the S. atractyloides LTR sequences were monophyletic, but where both subgenomes were non-monophyletic. For the final set of five orthogroups passing all this filtering (Supplementary Fig. 07), we calculated pairwise Jukes Cantor distances between each (1) S. atractyloides LTR-region, and between (2) S. atractyloides and H. annuus. The Jukes Cantor distances were plotted as frequency histograms in R (see Supplementary Fig. 06), and the peaks of the Scalesia-vs-Scalesia (golden on Supplementary Fig. 07) and Scalesia-vs-Helianthus (grey on Supplementary Fig. 07) were converted to million of years distance by a simple rule of three with the Helianthus divergence with Scalesia of 6.14 Mya (Supplementary Information; Supplementary Fig. 07).

Signatures of selection and expanded gene regions

Using the Scalesia genome together with the remaining Asteraceae genomes we ran CAFÉ analyses142,143 to estimate significant gene-family expansions and contractions. Briefly, we did an all-by-all BLAST to identify orthologues in the dataset and estimated significantly expanded and contracted families using CAFÉ. To interpret the data we relied on Gene Ontology Annotation (GO). We obtained GOs for the annotated Scalesia genes by means of two complementary approaches: (1) by using the Interproscan command-line version144, using the NCBI’s Conserved Domains Database (CDD), Prediction of Coiled Coil Regions in Proteins (COILS), Protein Information Resource (PIRSF), PRINTS, PFAM, ProDom, ProSitePatterns and ProSiteProfiles, the Structure–Function Linkage Database (SFLD), Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART), SUPERFAMILY, and TIGRFAMs databases; (2) by extracting the curated Swiss Prot database from UniProt (Viridiplantae) and blasting blasted the Scalesia genes to this database, keeping hits with an e-value below 1e-10. We then extracted the GOs from genes from the database and assigned these to Scalesia’s correspondent orthologs. Genes belonging to significantly expanded gene families in the S. atractyloides genome were analysed using a GO enrichment analysis. To do so, we used the TopGO package using the ‘elim’ algorithm which takes GO hierarchy into account145,146, this was then summarised using REVIGO147.

To test which genes are under positive selection in S. atractyloides genome, we retrieved the orthogroups from all Asteraceae, and aligned the cds from each orthogroup using prank148. Considering the divergence in the genomes, as well as evidence for fast evolution in Asteraceae genomes (including this paper), we ran zorro149, to assess the alignments. Zorro scores each alignment position between 0 and 10, and we selected only alignments with an average score position of 5 or greater. For each of these, we inferred a tree using IQtree and ran HyPhy using its aBSREL positive selection test150,151. To summarise these results we: (1) ran a GO enrichment analysis (as specified above) to obtain general insights, plotting results using REVIGO; (2) identified the Arabidopsis ortholog to each of the Scalesia genes under selection using BLAST, and analysed the Arabidopsis literature for that particular gene (Supplementary Information; Supplementary Table 08); (3) we ran a STRING analysis (Supplementary Fig. 07) using the Arabidopsis orthologs152, thereby exploring the potential protein-protein interactions among genes under selection. Interaction scores of edges were calculated based on the parameters Experiments, Co-expression, Neighborhood, Gene fusion and Co-occurrence. Edges with interaction score higher than 0.400 were kept in the network. After excluding genes with no physical connection, the STRING network had 627 nodes with 470 edges (PPI enrichment P value < 0.001). To simplify the densely connected network into potential biologically functional clusters, we used the distance matrix obtained from the STRING global scores as the input to perform a k-means clustering analysis (number of clusters = 6). Four of the six clusters are enriched for biological processes related GO terms. Cluster 1 (red bubbles) were enriched for the GO term metabolic processes, cluster 3 (lime green bubbles) for histone modifications and chromosome organisation, cluster 4 (green bubbles) for response to light, and cluster 6 (purple bubbles) for ribosomal large subunit biogenesis and RNA processing.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

J.Ce. is grateful to Simen R. Sandve for fruitful discussion and Martin LaForest for sharing genome annotations. We thank Henning Adsersen for the botanical expertise and logistical support that enabled use of the University of Copenhagen botanical collections. Jennifer Mandel kindly shared the Asteraceae COS. The collection and photography of specimens, and the preparation of this manuscript, benefited enormously from the cooperative assistance of the personnel of the Charles Darwin Foundation Research Station, who made arrangements for collecting trips, arranged laboratory space, and offered encouragement and support throughout the project. Scalesia specimens were initially collected under Galápagos National Park research permit number PC-001/98 PNG and were further normalised via Ecuador Ministry of the Environment genetic permit number MAAE-DBI-CM-2021-0213. This publication is contribution number 2426 of the Charles Darwin Foundation for the Galápagos Islands. This work was supported by the Norwegian Research Council via project number 287327 awarded to M.D.M., and a travel grant (project number 287327) granted to J.Ce. and M.D.M.

Author contributions

J.Ce. designed the experiment, processed and analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. B.P., J.M.L.G., A.R.-C., J.Ca., Q.L., S.B., J.V., S.L. and D.M. helped J.Ce. analyse the data. J.L. was responsible for the flow cytometry analyses. C.K. and L.S.-B. helped in retrieving DNA/RNA, N.W., M.N., P.J.D. and G.R.-T. obtained permits. M.F.-M., P.V. and R.M. obtained the outgroups. G.P., A.S., N.S., N.N., O.S., T. G., J.H. L.-M., L.R. and L.N. contributed expertise in data generation and interpretation, A.S. assisted with the TE analyses. M.D.M. obtained funding, generated the data and helped interpreting. Every author commented, revised and approved the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Zhen Li and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Data availability

The raw data generated in this study have been deposited in the ENA database under accession PRJEB52418. The assembly and the annotation files are available at Cerca, J. (2022), Scalesia atractyloides genome assembly, Dryad, Dataset, 10.5061/dryad.8gtht76rh.

Code availability

An overview of the bioinformatic methods is provided in https://github.com/jcerca/Papers/tree/main/scalesia_genome.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

8/22/2022

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

Contributor Information

José Cerca, Email: jose.cerca@gmail.com.

Michael D. Martin, Email: mike.martin@ntnu.no

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-31280-w.

References

- 1.Darwin, C. On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or, The preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. (1859). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Wallace, A. R. The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-utan and the Bird of Paradise; a Narrative of Travel, with Studies of Man and Nature (Courier Corporation, 1962).

- 3.Mayr, E. Systematics and the Origin of Species from the Viewpoint of a Zoologist (Columbia Uni. Press, 1942).

- 4.Emerson BC. Speciation on islands: what are we learning? Biol. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 2008;95:47–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01120.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lomolino, M. V., Riddle, B. R., Whittaker, R. J., Brown, J. H. & Lomolino, M. V. Biogeography (Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates, 2017).

- 6.Baeckens S, Van Damme R. The island syndrome. Curr. Biol. 2020;30:R338–R339. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns, K. C. Evolution in Isolation: The Search for an Island Syndrome in Plants (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

- 8.Blaschke JD, Sanders RW. Preliminary insights into the phylogeny and speciation of scalesia (asteraceae), galápagos islands. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Tex. 2009;3:177–191. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernández-Mazuecos M, et al. The radiation of Darwin’s giant daisies in the Galápagos Islands. Curr. Biol. 2020;30:4989–4998.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford DJ, et al. Genetic diversity in Asteraceae endemic to oceanic islands: Baker’s Law and polyploidy. Syst. Evol. Biogeogr. Compos. 2009;139:151. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eliasson U. Studies in Galápagos plants. XIV. The genus Scalesia Arn. Opera Bot. 1974;36:1–117. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itow S. Phytogeography and ecology of Scalesia (compositae) endemic to the Galapagos islands! Pac. Sci. 1995;49:17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stöcklin J. Darwin and the plants of the Galápagos-Islands. Bauhinia. 2009;21:33–48. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ono M. Chromosome number of Scalesia (Compositae), an endemic genus of the Galapagos Islands. J. Jpn. Bot. 1967;42:353–360. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eliasson U. Studies in Galapagos plants. XIV. The genus Scalesia Arn. Opera Bot. 1974;36:1–117. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meudt HM, et al. Polyploidy on islands: its emergence and importance for diversification. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12:637214. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.637214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spring O, Heil N, Vogler B. Sesquiterpene lactones and flavanones in Scalesia species. Phytochemistry. 1997;46:1369–1373. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(97)00464-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schilling EE, Panero JL, Eliasson UH. Evidence from chloroplast DNA restriction site analysis on the relationships of Scalesia (Asteraceae: Heliantheae) Am. J. Bot. 1994;81:248–254. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1994.tb15436.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peona V, Weissensteiner MH, Suh A. How complete are ‘complete’ genome assemblies?-An avian perspective. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2018;18:1188–1195. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badouin H, et al. The sunflower genome provides insights into oil metabolism, flowering and Asterid evolution. Nature. 2017;546:148–152. doi: 10.1038/nature22380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reyes-Chin-Wo S, et al. Genome assembly with in vitro proximity ligation data and whole-genome triplication in lettuce. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14953. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellinger, M. R., Datlof, E., Selph, K. E., Gallaher, T. J. & Knope, M. L. A genome for Bidens hawaiensis: a member of a hexaploid Hawaiian plant adaptive radiation. J. Hered. 10.1093/jhered/esab077 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Edger PP, McKain MR, Bird KA, VanBuren R. Subgenome assignment in allopolyploids: challenges and future directions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018;42:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Session AM, et al. Genome evolution in the allotetraploid frog Xenopus laevis. Nature. 2016;538:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature19840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitros T, et al. Genome biology of the paleotetraploid perennial biomass crop Miscanthus. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5442. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18923-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Funk, V. A. Systematics, Evolution, and Biogeography of Compositae (International Association for Plant Taxonomy, 2009).

- 27.Julca I, et al. Genomic evidence for recurrent genetic admixture during the domestication of Mediterranean olive trees (Olea europaea L.) BMC Biol. 2020;18:148. doi: 10.1186/s12915-020-00881-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.te Beest M, et al. The more the better? The role of polyploidy in facilitating plant invasions. Ann Bot. 2012;109:19–45. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcr277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandel JR, et al. A fully resolved backbone phylogeny reveals numerous dispersals and explosive diversifications throughout the history of Asteraceae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:14083–14088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903871116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whittaker, R. J., School of Geography Robert J Whittaker & Fernandez-Palacios, J. M. Island Biogeography: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation (OUP Oxford, 2007).

- 31.Diop SI, et al. A pseudomolecule-scale genome assembly of the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. Plant J. 2020;101:1378–1396. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li F-W, et al. Anthoceros genomes illuminate the origin of land plants and the unique biology of hornworts. Nat. Plants. 2020;6:259–272. doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-0618-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lang D, et al. ThePhyscomitrella patenschromosome-scale assembly reveals moss genome structure and evolution. Plant J. 2018;93:515–533. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bird KA, VanBuren R, Puzey JR, Edger PP. The causes and consequences of subgenome dominance in hybrids and recent polyploids. N. Phytol. 2018;220:87–93. doi: 10.1111/nph.15256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freeling M, Scanlon MJ, Fowler JE. Fractionation and subfunctionalization following genome duplications: mechanisms that drive gene content and their consequences. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2015;35:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfe KH. Yesterday’s polyploids and the mystery of diploidization. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001;2:333–341. doi: 10.1038/35072009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bird KA, et al. Replaying the evolutionary tape to investigate subgenome dominance in allopolyploid Brassica napus. N. Phytol. 2021;230:354–371. doi: 10.1111/nph.17137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alger EI, Edger PP. One subgenome to rule them all: underlying mechanisms of subgenome dominance. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2020;54:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Renny-Byfield S, Gong L, Gallagher JP, Wendel JF. Persistence of subgenomes in paleopolyploid cotton after 60 my of evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:1063–1071. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Douglas GM, et al. Hybrid origins and the earliest stages of diploidization in the highly successful recent polyploid Capsella bursa-pastoris. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:2806–2811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412277112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barrier M, Baldwin BG, Robichaux RH, Purugganan MD. Interspecific hybrid ancestry of a plant adaptive radiation: allopolyploidy of the Hawaiian silversword alliance (Asteraceae) inferred from floral homeotic gene duplications. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999;16:1105–1113. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Catchen JM, Conery JS, Postlethwait JH. Automated identification of conserved synteny after whole-genome duplication. Genome Res. 2009;19:1497–1505. doi: 10.1101/gr.090480.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Őszi E, et al. E2FB interacts with RETINOBLASTOMA RELATED and regulates cell proliferation during leaf development. Plant Physiol. 2020;182:518–533. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berckmans B, et al. Light-dependent regulation of DEL1 is determined by the antagonistic action of E2Fb and E2Fc. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:1440–1451. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.183384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kojima S, et al. Asymmetric leaves2 and Elongator, a histone acetyltransferase complex, mediate the establishment of polarity in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011;52:1259–1273. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Husbands AY, Benkovics AH, Nogueira FTS, Lodha M, Timmermans MCP. The ASYMMETRIC LEAVES complex employs multiple modes of regulation to affect adaxial-abaxial patterning and leaf complexity. Plant Cell. 2016;27:3321–3335. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crane RA, et al. Negative regulation of age-related developmental leaf senescence by the IAOx pathway, PEN1, and PEN3. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:1202. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fu M, et al. AtWDS1 negatively regulates age-dependent and dark-induced leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2019;285:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang B, Jia J, Yang M, Yan C, Han Y. Overexpression of a LAM domain containing RNA-binding protein LARP1c induces precocious leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cells. 2012;34:367–374. doi: 10.1007/s10059-012-0111-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma Z, Wu W, Huang W, Huang J. Down-regulation of specific plastid ribosomal proteins suppresses thf1 leaf variegation, implying a role of THF1 in plastid gene expression. Photosynth. Res. 2015;126:301–310. doi: 10.1007/s11120-015-0101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Z, et al. Two chloroplast proteins suppress drought resistance by affecting ROS production in guard cells. Plant Physiol. 2016;172:2491–2503. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meurer J, et al. PALE CRESS binds to plastid RNAs and facilitates the biogenesis of the 50S ribosomal subunit. Plant J. 2017;92:400–413. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holding D. The chloroplast and leaf developmental mutant, pale cress, exhibits light-conditional severity and symptoms characteristic of its ABA deficiency. Ann. Bot. 2000;86:953–962. doi: 10.1006/anbo.2000.1263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meurer J, Grevelding C, Westhoff P, Reiss B. The PAC protein affects the maturation of specific chloroplast mRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Gen. Genet. MGG. 1998;258:342–351. doi: 10.1007/s004380050740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lawesson, J. E. Stand-level dieback and regeneration of forests in the Galápagos Islands. Temporal and Spatial Patterns of Vegetation Dynamics 87–93. 10.1007/978-94-009-2275-4_10 (1988).

- 56.Endo M, Kudo D, Koto T, Shimizu H, Araki T. Light-dependent destabilization of PHL in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2014;9:e28118. doi: 10.4161/psb.28118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Endo M, Tanigawa Y, Murakami T, Araki T, Nagatani A. PHYTOCHROME-DEPENDENT LATE-FLOWERING accelerates flowering through physical interactions with phytochrome B and CONSTANS. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:18017–18022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310631110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li G, et al. Coordinated transcriptional regulation underlying the circadian clock in Arabidopsis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:616–622. doi: 10.1038/ncb2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Basset GJC, et al. Folate synthesis in plants: the last step of the p-aminobenzoate branch is catalyzed by a plastidial aminodeoxychorismate lyase. Plant J. 2004;40:453–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smeekens, S. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Large-scale analysis of mRNA translation states during sucrose starvation in arabidopsis cells identifies cell proliferation and chromatin structure as targets of translational control. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature. 10.3410/f.1032260.373846 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Oravecz A, et al. CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 is required for the UV-B response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1975–1990. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.040097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dal Bosco C, et al. Inactivation of the chloroplast ATP synthase gamma subunit results in high non-photochemical fluorescence quenching and altered nuclear gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:1060–1069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308435200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tan Y-F, O’Toole N, Taylor NL, Millar AH. Divalent metal ions in plant mitochondria and their role in interactions with proteins and oxidative stress-induced damage to respiratory function. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:747–761. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.147942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim JY, et al. Functional characterization of a glycine-rich RNA-binding protein 2 in Arabidopsis thaliana under abiotic stress conditions. Plant J. 2007;50:439–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.ten Hove CA, et al. Probing the roles of LRR RLK genes in Arabidopsis thaliana roots using a custom T-DNA insertion set. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011;76:69–83. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9769-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jakoby MJ, et al. Transcriptional profiling of mature Arabidopsis trichomes reveals that NOECK encodes the MIXTA-like transcriptional regulator MYB106. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1583–1602. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.126979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fox AR, et al. Plasma membrane aquaporins interact with the endoplasmic reticulum resident VAP27 proteins at ER-PM contact sites and endocytic structures. N. Phytol. 2020;228:973–988. doi: 10.1111/nph.16743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang P, et al. Plant AtEH/Pan1 proteins drive autophagosome formation at ER-PM contact sites with actin and endocytic machinery. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5132. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12782-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bittner, A., Hause, B. & Baier, M. Cold-priming causes oxylipin dampening during the early cold and light response of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 10.1093/jxb/erab314 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Kuki Y, Ohno R, Yoshida K, Takumi S. Heterologous expression of wheat WRKY transcription factor genes transcriptionally activated in hybrid necrosis strains alters abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020;150:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Czarnocka, W. et al. FMO1 is involved in excess light stress-induced signal transduction and cell death signaling. Cells9, 2163 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Kleine T, Kindgren P, Benedict C, Hendrickson L, Strand A. Genome-wide gene expression analysis reveals a critical role for CRYPTOCHROME1 in the response of Arabidopsis to high irradiance. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1391–1406. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.098293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Castells E, et al. The conserved factor DE-ETIOLATED 1 cooperates with CUL4-DDB1DDB2 to maintain genome integrity upon UV stress. EMBO J. 2011;30:1162–1172. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lahari T, Lazaro J, Marcus JM, Schroeder DF. RAD7 homologues contribute to Arabidopsis UV tolerance. Plant Sci. 2018;277:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim A, et al. Non-intrinsic ATP-binding cassette proteins ABCI19, ABCI20 and ABCI21 modulate cytokinin response at the endoplasmic reticulum in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 2020;39:473–487. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02503-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen D, Molitor A, Liu C, Shen W-H. The Arabidopsis PRC1-like ring-finger proteins are necessary for repression of embryonic traits during vegetative growth. Cell Res. 2010;20:1332–1344. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shen L, et al. The putative PRC1 RING-finger protein AtRING1A regulates flowering through repressing MADS AFFECTING FLOWERING genes in Arabidopsis. Development. 2014;141:1303–1312. doi: 10.1242/dev.104513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li J, Wang Z, Hu Y, Cao Y, Ma L. Polycomb group proteins RING1A and RING1B regulate the vegetative phase transition in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:867. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.An Z, et al. The histone methylation readers MRG1/MRG2 and the histone chaperones NRP1/NRP2 associate in fine-tuning Arabidopsis flowering time. Plant J. 2020;103:1010–1024. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gómez-Zambrano Á, et al. Arabidopsis SWC4 binds DNA and recruits the SWR1 complex to modulate histone H2A.Z deposition at key regulatory genes. Mol. Plant. 2018;11:815–832. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Glass M, Barkwill S, Unda F, Mansfield SD. Endo-β−1,4-glucanases impact plant cell wall development by influencing cellulose crystallization. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2015;57:396–410. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Markakis, M. N. et al. Identification of genes involved in the ACC-mediated control of root cell elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol.12, 1–11 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Noutoshi Y, et al. Loss of necrotic spotted lesions 1 associates with cell death and defense responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006;62:29–42. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-9001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fukunaga S, et al. Dysfunction of Arabidopsis MACPF domain protein activates programmed cell death via tryptophan metabolism in MAMP-triggered immunity. Plant J. 2017;89:381–393. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Singh S, Kailasam S, Lo J, Yeh K. Histone H3 lysine4 trimethylation‐regulated GRF11 expression is essential for the iron‐deficiency response in Arabidopsis thaliana. N. Phytologist. 2021;230:244–258. doi: 10.1111/nph.17130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fal, K. et al. Phyllotactic regularity requires the Paf1 complex in Arabidopsis. Development10.1242/dev.154369 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.He Y. PAF1-complex-mediated histone methylation of FLOWERING LOCUS C chromatin is required for the vernalization-responsive, winter-annual habit in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2774–2784. doi: 10.1101/gad.1244504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hoson T, et al. Growth stimulation in inflorescences of an Arabidopsis tubulin mutant under microgravity conditions in space. Plant Biol. 2014;16:91–96. doi: 10.1111/plb.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xiong X, Xu D, Yang Z, Huang H, Cui X. A single amino-acid substitution at lysine 40 of an Arabidopsis thaliana α-tubulin causes extensive cell proliferation and expansion defects. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2013;55:209–220. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Whitewoods CD, et al. CLAVATA was a genetic novelty for the morphological innovation of 3D growth in land plants. Curr. Biol. 2020;30:2645–2648. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Galbraith DW, et al. Rapid flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle in intact plant tissues. Science. 1983;220:1049–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.220.4601.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dolezel J, Sgorbati S, Lucretti S. Comparison of three DNA fluorochromes for flow cytometric estimation of nuclear DNA content in plants. Physiologia Plant. 1992;85:625–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1992.tb04764.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Loureiro J, Rodriguez E, Dolezel J, Santos C. Two new nuclear isolation buffers for plant DNA flow cytometry: a test with 37 species. Ann. Bot. 2007;100:875–888. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Suda J, et al. Genome size variation and species relationships in Hieracium sub-genus Pilosella (Asteraceae) as inferred by flow cytometry. Ann. Bot. 2007;100:1323–1335. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Greilhuber J, Dolezel J, Lysák MA, Bennett MD. The origin, evolution and proposed stabilization of the terms ‘genome size’ and ‘C-value’ to describe nuclear DNA contents. Ann. Bot. 2005;95:255–260. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dolezel J, Bartos J, Voglmayr H, Greilhuber J. Nuclear DNA content and genome size of trout and human. Cytom. Part A: J. Int. Soc. Anal. Cytol. 2003;51:127–128. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Putnam NH, et al. Chromosome-scale shotgun assembly using an in vitro method for long-range linkage. Genome Res. 2016;26:342–350. doi: 10.1101/gr.193474.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ruan J, Li H. Fast and accurate long-read assembly with wtdbg2. Nat. Methods. 2020;17:155–158. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0669-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Laetsch DR, Blaxter ML. BlobTools: Interrogation of genome assemblies. F1000Res. 2017;6:1287. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12232.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Guan D, et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:2896–2898. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bradnam KR, et al. Assemblathon 2: evaluating de novo methods of genome assembly in three vertebrate species. Gigascience. 2013;2:10. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Smit, A., Hubley, R. & Green, P. RepeatMasker 4.0 (Institute for Systems Biology, 2013).

- 103.Flynn JM, et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:9451–9457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1921046117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tardaguila M, et al. Corrigendum: SQANTI: extensive characterization of long-read transcript sequences for quality control in full-length transcriptome identification and quantification. Genome Res. 2018;28:1096. doi: 10.1101/gr.239137.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Holt C, Yandell M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinforma. 2011;12:491. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Moore, B., Holt, C., Alvarado, A. S. & Yandell, M. MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome18, 188–196 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 107.Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinforma. 2004;5:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Keller O, Kollmar M, Stanke M, Waack S. A novel hybrid gene prediction method employing protein multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:757–763. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Waterhouse RM, et al. BUSCO applications from quality assessments to gene prediction and phylogenomics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:543–548. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Seppey M, Manni M, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;1962:227–245. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data [Online]. Available online at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (2010).