Abstract

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is one of the most life- and health-threatening malignant diseases worldwide, especially in China. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as important regulators of tumorigenesis and tumor progression. However, the roles and mechanisms of lncRNAs in ESCC require further exploration. Here, in combination with a small interfering RNA (siRNA) library targeting specific lncRNAs, we performed MTS and Transwell assays to screen functional lncRNAs that were overexpressed in ESCC. TMPO-AS1 expression was significantly upregulated in ESCC tumor samples, with higher TMPO-AS1 expression positively correlated with shorter overall survival times. In vitro and in vivo functional experiments revealed that TMPO-AS1 promotes the proliferation and metastasis of ESCC cells. Mechanistically, TMPO-AS1 bound to fused in sarcoma (FUS) and recruited p300 to the TMPO promoter, forming biomolecular condensates in situ to activate TMPO transcription in cis by increasing the acetylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27ac). Targeting TMPO-AS1 led to impaired ESCC tumor growth in a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model. We found that TMPO-AS1 is required for cell proliferation and metastasis in ESCC by promoting the expression of TMPO, and both TMPO-AS1 and TMPO might be potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in ESCC.

Subject terms: Oesophageal cancer, Oncogenes, Long non-coding RNAs

Esophageal cancer: Regulatory RNA increases a hormone that promotes cancer

The role of a regulatory RNA in promoting esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) has been clarified, revealing molecular details that might help in cancer diagnosis and treatment. Xiao-Jing Luo and colleagues at Sun Yat-sen University in China found that overproduction of an RNA molecule called thymopoietin-antisense RNA 1 (TMPO-AS1) in ESCC tissue samples from cancer patients was associated with shorter survival times. Overproduction of this RNA promoted proliferation and spread (metastasis) of the cancer cells. Research on details of the molecular mechanisms involved showed that the RNA ultimately activated the gene that codes for the protein hormone thymopoietin, which has previously been linked with various cancers. The authors suggest that TMPO-AS1 and thymopoietin could serve as diagnostic biomarkers of cancer and become targets for anti-cancer drugs.

Introduction

Esophageal carcinoma (ESCA) is the 6th leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide1. In China, the predominant histological subtype of ESCA is esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), which ranks 4th in cancer-related mortality2. Although the clinical community has achieved some diagnostic and therapeutic advances, patients with advanced ESCC have a poor prognosis due to recurrence and metastasis, leading to a 5-year survival rate of less than 20%2,3. Genetic abnormalities and molecular alterations play essential roles in the progression of ESCC and are potential therapeutic targets4. Therefore, a more comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanism underlying ESCC progression is vital for the development of novel biomarkers and effective therapeutic targets for this disease.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of transcripts with a length of more than 200 nucleotides and virtually no protein-coding potential5. LncRNAs play extensive roles in various physiological and pathological processes, including tumor initiation and progression. Recent reports have revealed diverse functional mechanisms for lncRNAs, such as acting as microRNA sponges, endogenous small interfering RNA (siRNA) precursors, or molecular scaffolds to interact with proteins or other RNAs, and even encoding short peptides6–8. Roles of lncRNAs in ESCC have been reported. For example, the lncRNA DNM3OS confers radioresistance by regulating the DNA damage response9, and AGPG regulates PFKFB3-mediated tumor glycolytic reprogramming10. These studies indicate that targeting lncRNAs could be a novel approach for ESCC therapy. However, further investigations into more specific roles of lncRNAs in ESCC tumorigenesis and progression are still needed.

Natural antisense (NAT) lncRNAs are classified by their genomic location with respect to the cognate protein-coding genes. The sequences of NAT lncRNAs are often partially complementary to the transcripts of their neighboring genes6, and NAT lncRNAs and their neighboring genes often exhibit concordant or discordant expression patterns11. Recent studies have shown that NAT lncRNAs function as epigenetic regulators of the expression of their cognate genes12,13.

In this study, we found that the upregulated NAT lncRNA TMPO-AS1 functions as an oncogenic regulator in ESCC. TMPO-AS1 promoted ESCC cell proliferation, G1/S progression and metastasis. Mechanistically, TAS1 recruited FUS and p300 to the TMPO promoter and formed condensates in situ, which upregulated TMPO expression by increasing the deposition of H3K27ac in the promoter and activating TMPO transcription in cis, subsequently regulating the expression of CyclinD1 and metastasis-associated protein 1 (MTA1) to promote ESCC progression. Overall, this study showed the biological roles and underlying mechanisms of the TMPO-AS1/TMPO axis in ESCC and suggested TMPO-AS1 as a promising prognostic indicator and therapeutic target in ESCC.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

Het-1A and NE-1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD, USA). HEK293T, KYSE30, KYSE150, KYSE180, KYSE410, KYSE510 and KYSE520 cells were obtained from the German Cell Culture Collection (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). TE-1, TE-9, TE-11 and TE-15 cells were obtained from the Cell Bank of Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology (Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Shanghai, China). Cells were grown in basic Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) or RPMI-1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. All cells were further verified via STR-PCR DNA profiling by Guangzhou Cellcook Biotech Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China) and tested negative for mycoplasma contamination before use.

Human tissue specimens

Clinical samples were collected from Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (SYSUCC; Guangzhou, China). All patients were histologically diagnosed with ESCC. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University.

Cell line-derived xenograft (CDX) and patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models

To establish CDX models, ESCC cells expressing control shRNA (shCtrl) or TAS1-targeting sh#1 or sh#2 were injected subcutaneously into the dorsal flanks of 4-week-old female BALB/c nu/nu mice (five mice per group). Tumor growth was monitored every 3 days after transplantation using calipers. Mice bearing xenografts were euthanized at the endpoint, and tumors were weighed. PDX models were established as described previously14 and were used to assess the in vivo therapeutic effects of TAS1 using ASOs. When the volume of the PDXs was ~500 mm3, we began intratumoral injections of 5 nmol of scrambled or in vivo-optimized TMPO-AS1 ASOs (RiboBio; Guangzhou, China) per injection every 3 days, for a total of 4 consecutive doses. The target sequence is provided in Supplementary Table 1. More details are described in the supplementary methods.

In vivo metastasis models

To establish the lung metastasis model, ESCC cells expressing luciferase and transfected with shCtrl or TAS1-targeting sh#1 or sh#2 were intravenously injected into 4-week-old female BALB/c nu/nu mice (six mice per group) through the tail vein. In vivo bioluminescence imaging was performed every four weeks after inoculation. The mice were euthanized 8 weeks after injection. The number of lung nodules was determined in hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained serial lung tissue sections using a microscope.

To establish the popliteal sentinel lymph node metastasis model15, ESCC cells transfected with shCtrl or TAS1-targeting sh#1 or sh#2 were injected into the left footpads of 4-week-old female BALB/c nu/nu mice (six mice per group). Eight weeks after injection, the mice were euthanized, and the lymph nodes were collected. The number of metastasis-positive lymph nodes was determined. More details are described in the supplementary methods.

Nuclear run-on (NRO) assay

The NRO assay was performed as previously described16. Nuclei of 4 × 106 ESCC cells were freshly isolated with NP-40 lysis buffer and kept on ice before use. Nascent RNA transcripts were immunoprecipitated with an anti-BrdU antibody (Abcam, ab6326) and subjected to qPCR analysis to detect the expression of TMPO nascent mRNA. More details are described in the supplementary methods.

RNA pulldown assay

TAS1 RNA was transcribed in vitro using a MEGAscript T7 Transcription Kit (Invitrogen, USA) and labeled with a Pierce RNA 3’ End Desthiobiotinylation Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Cell lysates were prepared with Pierce IP lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific, USA). RNA pulldown was performed with a Pierce Magnetic RNA–Protein PullDown Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) according to the instructions. Briefly, biotinylated RNA was captured on streptavidin magnetic beads and was then incubated with cell lysates at 4 °C for 6 h before washing and elution of RNA–protein complexes. The eluted proteins were subjected to WB analysis.

RIP assay

The RIP assay was performed using a Magna RIP RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore, Bedford, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. IgG isotype control and human anti-FUS antibodies (5 μg/sample, Abcam, ab70381) were used in this assay. After proteinase K digestion, the immunoprecipitated RNAs were extracted, purified, and subjected to qPCR analysis. RNA levels were normalized to those in the 10% input sample.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

The ChIP assay was performed using a ChIP kit from Merck Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR analysis was performed to detect the DNA fragments that coimmunoprecipitated with H3K27ac. The primers specific for the TMPO promoter region are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Chromatin isolation by RNA purification (ChIRP) assay

The ChIRP assay was performed using a Magna ChIRP RNA Interactome Kit (Millipore, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions17. The purified bound DNA was isolated for qRT–PCR, and proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. Probe information is included in Supplementary Table 3.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± S.D. values. Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA and the chi-square test were performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) to compare differences between groups. Correlations between the expression levels of TMPO-AS1 and TMPO were analyzed using Pearson correlation analysis. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences were assessed with SPSS software using the log-rank test. The levels of significance are denoted as follows: * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001 and ns indicates not significant.

Results

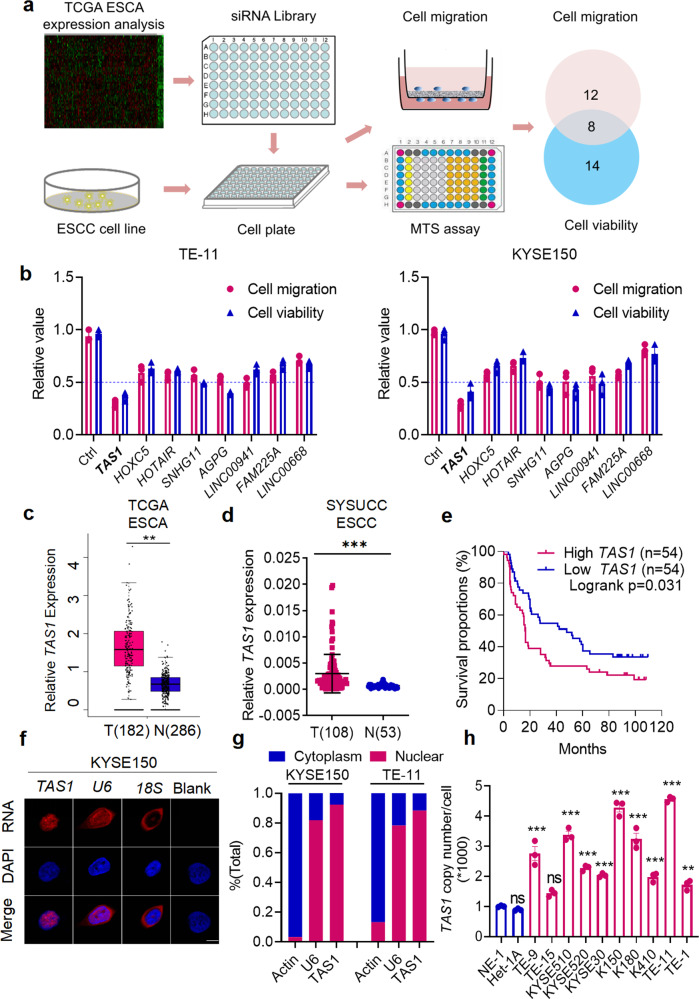

Identification of TMPO-AS1 as an oncogenic natural antisense lncRNA

We previously designed a highly efficient and specific siRNA library targeting the 50 most highly expressed lncRNAs in ESCC tumor samples compared to paired normal adjacent tissues from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Using this library, we previously identified the lncRNA AGPG, which affects cell proliferation and glycolysis10. We transfected the siRNA library into two human ESCC cell lines, KYSE150 and TE-11, and performed MTS cell viability assays and Transwell migration assays to identify the lncRNAs that play essential roles in ESCC tumorigenesis and progression (Fig. 1a). Fourteen lncRNAs were found to exert promotive effects on cell proliferation, and 12 were potentially involved in cell migration; 8 of the lncRNAs were shared between both groups and might thus be involved in both cell proliferation and migration (Fig. 1a). Among these 8 lncRNAs, silencing of TMPO-AS1 most potently attenuated ESCC cell proliferation and migration (Fig. 1b; the p values are shown in Supplementary Table 4). TMPO-AS1 is an antisense lncRNA located on chromosome 12q23.1 and is transcribed from the antisense strand in the opposite direction of TMPO and composed of 2 exons (Supplementary Fig. 1a). To check the coding potential, we performed the in silico analysis with the Coding Potential Assessment Tool (CPAT) to calculate the score for TMPO-AS1. According to CPAT analysis, the coding probability of TMPO-AS1 is 0.001, which is lower than that of other well-characterized lncRNAs, such as nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (NEAT1), colon cancer-associated transcript 1 (CCAT1), and NF-κB interacting lncRNA (NKILA) (Supplementary Fig. 1b). In addition, for in vitro validation of the peptide-coding potential, the TMPO-AS1 sequence was inserted upstream of 3× Flag-Tag cassette in a plasmid, transfected into HEK293T cells, and immunoblotted with the Flag antibody. Consistent with the very low coding probability calculated by CPAT, no peptide or protein was detected (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1. The lncRNA TMPO-AS1 (TAS1) is upregulated in ESCC and indicates poor prognosis.

a Schematic showing the design of the screen for lncRNAs potentially involved in both cell viability and migration in ESCA. b Eight lncRNAs regulated both cell proliferation and migration in KYSE150 and TE-11 cells, including TAS1; n = 3 biologically independent samples. The p values for each group are shown in Supplementary Table 4. c TAS1 expression in ESCA tissues from TCGA data. d, e TAS1 expression and OS analysis in ESCC samples from the SYSUCC cohort. (n = 108, survival analysis: log-rank test, two-sided). f Detection of TAS1 subcellular localization in KYSE150 cells by FISH. Scale bar: 5 μm. g TAS1 expression in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of KYSE150 cells and TE-11 cells, as detected using qPCR. h Determination of the TAS1 copy number in ESCC cell lines and normal esophageal epithelial cell lines; n = 3, compared with NE1. The data are presented as the mean ± S.D. values. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

TMPO-AS1 expression is upregulated in ESCC and associated with poor prognosis in patients

Analysis of TCGA data showed upregulated TMPO-AS1 expression in tumor samples compared to normal tissues in various types of cancer tissues (Supplementary Fig. 1d), especially in ESCA tissues (Fig. 1c). In addition, survival analysis showed that patients with high TMPO-AS1 expression had shorter overall survival (OS) times across the whole set of various types of cancers (Supplementary Fig. 1e), suggesting that TMPO-AS1 may be a pancancer oncogene. Specifically, high TMPO-AS1 expression was also correlated with an unfavorable outcome in TCGA-ESCA patients (Supplementary Fig. 1f, n = 74). Because ESCC is one of the most predominant subtypes of ESCA, we verified that the TMPO-AS1 expression level was significantly higher in ESCC tissues (Fig. 1d). We also performed survival analysis in our independent ESCC cohort (Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (SYSUCC), n = 108). We categorized the TMPO-AS1 expression level according to the median value: the expression level was defined as high if higher than the median value and as low otherwise. High TMPO-AS1 expression was associated with unfavorable OS in patients with ESCC (Fig. 1e). The clinical characteristics of this cohort are shown in Supplementary Table 5. In addition, multivariate analysis showed that TMPO-AS1 was an independent prognostic factor in patients with ESCC (Supplementary Table 6).

Then, we examined the distribution of TMPO-AS1 by performing fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and subcellular fractionation assays followed by qPCR. Our results showed that TMPO-AS1 was localized predominantly in the nucleus, with a small amount localized in the cytoplasm, similar to the distribution pattern of the well-characterized nuclear lncRNA U6 (Fig. 1f, g, Supplementary Fig. 1g).

Next, we examined TMPO-AS1 expression in a panel of ESCC cell lines and two normal esophageal epithelial cell lines (Het1A and NE1) and found that the TMPO-AS1 level was significantly higher in the tumor cell lines than in normal cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 1h). We further determined the copy number of TMPO-AS1 and found that it was also increased in the ESCC cell lines compared to the normal cell lines (Fig. 1h). Together, these findings suggest that TMPO-AS1 upregulation might play a role in ESCC development.

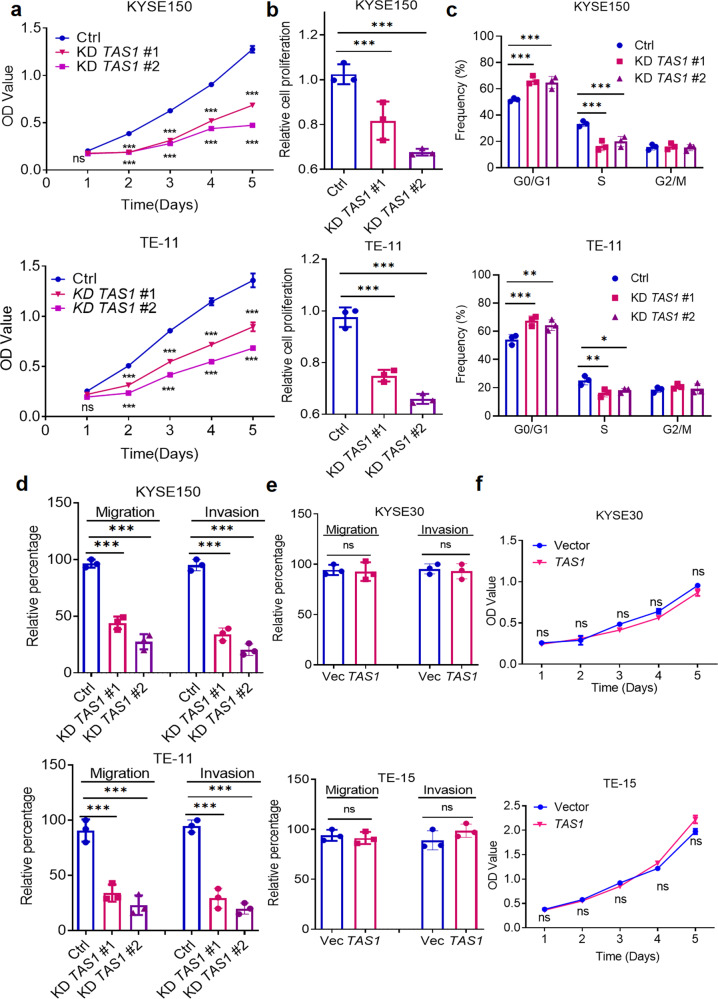

TMPO-AS1 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in vitro

We further investigated the oncogenic function of TMPO-AS1 by customized antisense oligonucleotide (ASO)-induced knockdown and lentiviral-mediated overexpression of TMPO-AS1 in ESCC cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). The target sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 7. Then, we performed MTS assays and found that TMPO-AS1 knockdown significantly reduced cell proliferation (Fig. 2a). In addition, BrdU incorporation assays revealed that silencing TMPO-AS1 reduced ESCC cell proliferation (Fig. 2b). Cell cycle analysis showed that TMPO-AS1 knockdown resulted in G1/S arrest (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, Transwell assays showed that TMPO-AS1 silencing inhibited the migration and invasion of ESCC cells (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 2d). Interestingly, ectopic overexpression of TMPO-AS1 had minimal effects on these parameters (Fig. 2e, f, Supplementary Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2. TAS1 promotes cell proliferation, migration and invasion in vitro.

a MTS assays were performed to measure the proliferation (OD 490 nm) of KYSE150 and TE-11 cells with TAS1 knockdown (KD) compared with control cells (n = 3). b BrdU incorporation assays (OD 450 nm) of KYSE150 and TE-11 cells with TAS1 KD compared with control cells (n = 3). c Statistical analysis of the cell cycle distribution (%) of KYSE150 and TE-11 cells with TAS1 KD compared with control cells. d Statistical analysis of the migration and invasion rates (%) of KYSE150 and TE-11 cells with TAS1 KD (n = 3). e Statistical analysis of the migration and invasion rates (%) of KYSE30 and TE-15 cells with TAS1 overexpression (OE) (n = 3). f MTS assays were performed to measure the proliferation of KYSE30 and TE-15 cells with TAS1 OE compared with control cells (n = 3). The data are presented as the mean±S.D. values. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Consistent with the effects of TMPO-AS1 on ESCC cell proliferation and migration, we also observed a positive yet non-significant association between TMPO-AS1 expression and ESCA pathological stage in the TCGA database (Supplementary Fig. 2f).

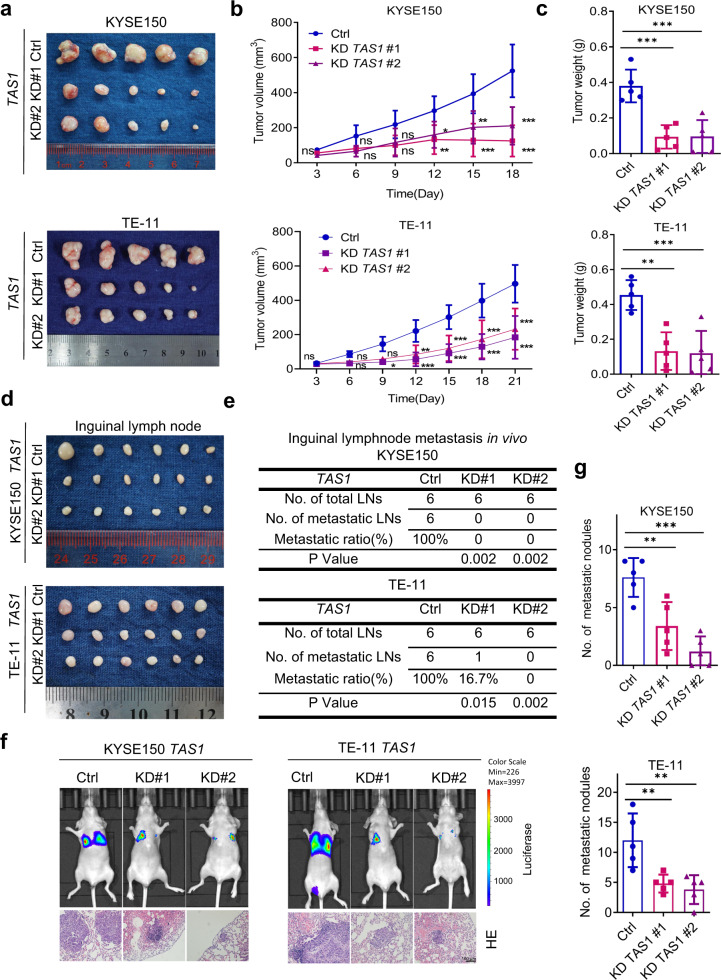

TMPO-AS1 facilitates ESCC tumor growth and metastasis in vivo

Next, we explored the role of TMPO-AS1 in tumorigenesis and tumor development in vivo. In the subcutaneous cell line-derived xenograft (CDX) model, TMPO-AS1 knockdown significantly inhibited tumor growth, as indicated by the decreased tumor volume and tumor weight (Fig. 3a–c). Then, we established a popliteal sentinel lymph node metastasis model in nude mice to evaluate the effects of TMPO-AS1 on ESCC lymph node metastasis15. The popliteal lymph nodes were harvested 8 weeks after tumor cell injection (Fig. 3d). The lymph nodes weighed slightly less in the TMPO-AS1 knockdown group than in the control group (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The metastasis-positive lymph nodes were identified by examining H&E-stained serial sections of each inguinal lymph node for metastatic micronodules. At least one locus of metastatic micronodules was required for classification as a metastasis-positive lymph node. Representative pictures of metastatic micronodules are shown and marked in Supplementary Fig. 3b. Our data revealed a significantly reduced metastasis ratio in the TMPO-AS1-silenced group (Fig. 3e), suggesting that TMPO-AS1 knockdown suppressed lymph node metastasis of ESCC. In addition, tail vein injection of TMPO-AS1-knockdown cells or control cells was performed to examine lung metastasis. In vivo bioluminescence imaging showed a decreased luminescence intensity in the lungs of mice injected with cells group compared to control cells (Fig. 3f). H&E staining of serial sections of lung tissues was performed to confirm metastasis and quantify metastatic nodules (Fig. 3f). The results showed significantly reduced numbers and volumes of metastatic nodules in the TMPO-AS1-silenced group (Fig. 3g), indicating that TMPO-AS1 knockdown suppressed hematogenous metastasis of ESCC.

Fig. 3. TAS1 facilitates tumor growth and metastasis in vivo.

a Image of subcutaneous xenograft tumors formed by KYSE150 and TE-11 cells transduced with shTAS1 #1, shTAS1 #2 or shCtrl in nude mice. (n = 5). b, c Subcutaneous tumor volume curve and statistical analysis of the weight of tumors formed by KYSE150 and TE-11 cells treated as indicated (n = 5). d Image of popliteal lymph nodes harvested 8 weeks after injection of KYSE150 and TE-11 cells with lentiviral shRNA vector-mediated TAS1 KD into the left footpads of nude mice (n = 6). e Statistical analysis of the incidence of popliteal lymph node metastasis in the indicated groups (chi-square test, two-sided). f Representative images of whole-body in vivo bioluminescence and H&E staining (scale bar, 100 μm) in lung sections from mice injected via the tail vein with KYSE150 and TE-11 cells with stable TAS1 (#1 and #2) knockdown or control (Ctrl) cells on Day 56 postinjection. g. Statistical analysis of the metastatic lung nodules confirmed by H&E staining (n = 5). The data are presented as the mean±S.D. values. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

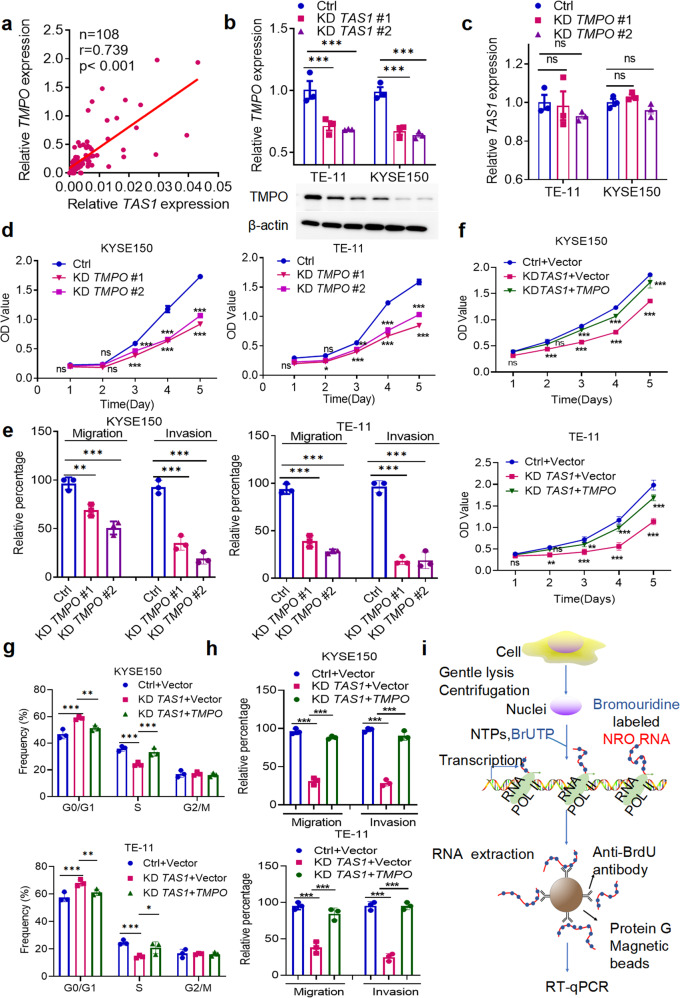

TMPO-AS1 performs its biological functions by regulating TMPO in ESCC

TMPO is located on the opposite strand of TMPO-AS1 on chromosome 12q21.2 and is the cognate gene of TMPO-AS1. Evidence suggests that TMPO plays diverse roles in various cancers18–21. Since some antisense lncRNAs perform their biological functions by regulating neighboring genes12,13,22, we investigated the regulatory relationship between TMPO and TMPO-AS1 expression in ESCC tissues. We found that TMPO expression was positively correlated with TMPO-AS1 expression in the SYSUCC-ESCC dataset (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, TMPO-AS1 silencing obviously reduced the expression of TMPO (Fig. 4b), whereas ectopic overexpression of TMPO-AS1 did not affect the TMPO level (Supplementary Fig. 4a). In contrast, TMPO silencing had no effect on TMPO-AS1 expression (Fig. 4c). The ASOs and siRNAs were designed to specifically target the nonoverlapping sequences of these two genes to exclude any off-target effects. Specific silencing of TMPO was confirmed by qPCR and WB analyses (Supplementary Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4. TAS1 performs its biological functions by cis-activating TMPO transcription.

a The correlation between TAS1 and TMPO mRNA expression in clinical ESCC tissues (SYSUCC, n = 97, Pearson correlation analysis). b Detection of TMPO expression by qPCR and WB in KYSE150 and TE-11 cells with TAS1 KD compared with control cells (n = 3). c Detection of TAS1 expression by qPCR in KYSE150 and TE-11 cells with TMPO KD compared with control cells (n = 3). d MTS assays were performed to evaluate the proliferation (OD 490 nm) of KYSE150 and TE-11 cells with TMPO KD (n = 3). e Statistical analysis of the migration and invasion rates (%) of KYSE150 and TE-11 cells with TMPO KD (n = 3). f–h MTS assays and statistical analysis of the cell cycle distribution (%) of KYSE150 cells treated as indicated and the migration and invasion rates (n = 3). i A schematic diagram of the NRO assay. The data are presented as the mean±S.D. values. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Similar to the TMPO-AS1 expression pattern in ESCC, the TMPO expression level was also increased in ESCC tissues, as confirmed by qPCR and immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d). TMPO was also upregulated in most ESCC cells (Supplementary Fig. 4e). We next investigated the role of TMPO in ESCC. Consistent with the phenotypes we observed after TMPO-AS1 knockdown, the MTS assay showed that TMPO silencing reduced ESCC cell proliferation (Fig. 4d). Cell cycle analysis revealed induction of G1/S phase arrest after TMPO knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 4f). Transwell assays revealed that TMPO knockdown inhibited ESCC cell migration and invasion (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. 4g). Thus, TMPO promotes cell proliferation, migration and invasion, mimicking the effects of TMPO-AS1, on ESCC cells.

We conducted a series of rescue experiments to investigate whether TMPO-AS1 performs its function in ESCC by regulating TMPO. Consistent with our prediction, MTS and Transwell assays showed that TMPO overexpression in TMPO-AS1-silenced cells decreased the inhibition of cell proliferation, G1/S progression, migration and invasion (Fig. 4f-h, Supplementary Fig. 4h). Collectively, these data suggest that TMPO-AS1 might promote ESCC tumorigenesis and metastasis by regulating TMPO expression.

TMPO-AS1 regulates the transcription of its cognate sense gene TMPO in cis

Numerous antisense lncRNAs have been reported to regulate the transcription of their cognate genes12,13. TMPO-AS1 is a NAT lncRNA transcribed in the opposite direction starting from the first intron in the antisense strand of TMPO, and it includes the transcription start site (TSS) and the 5’UTR of TMPO (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Therefore, we conducted an NRO assay to evaluate the regulation between TMPO-AS1 and TMPO. NRO assays can measure the transcription efficiency without the influence of degradation by labeling nascent transcripts with bromouridine (Fig. 4i). The results showed that TMPO-AS1 knockdown reduced the level of nascent TMPO mRNA transcripts (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). We also evaluated TMPO mRNA stability and found that TMPO-AS1 did not affect the degradation rate of TMPO mRNA in the presence of the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D (ActD) (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Together, these results suggest that TMPO-AS1 regulates TMPO transcription instead of affecting TMPO mRNA stability. Combined with the observation that ectopic expression of TMPO-AS1 exerted minimal effects, our results indicate that TMPO-AS1 might act in cis but not in trans to activate TMPO expression.

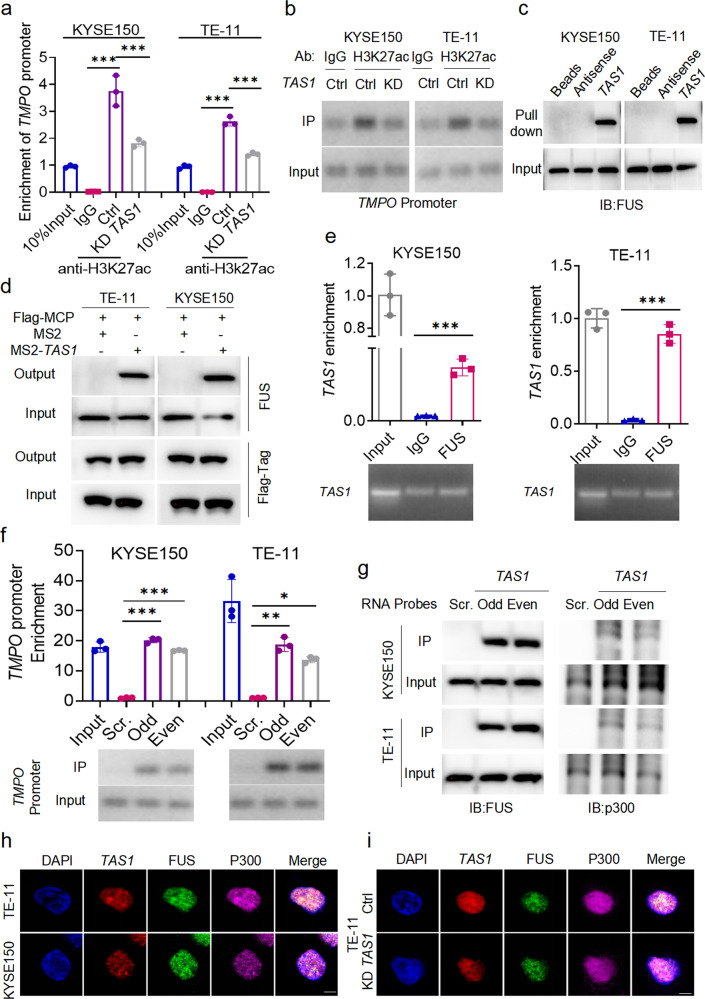

TMPO-AS1 increases the H3K27ac level in the TMPO promoter by recruiting FUS and p300 proteins to form biomolecular condensates

Next, we examined the gene loci of TMPO and TMPO-AS1 in the UCSC Genome Browser. We found that in different cell types, H3K27ac, which is the hallmark of open chromatin with active transcription, was enriched in the TSS-harboring regions of both genes (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Next, we performed ChIP–qPCR using the anti-H3K27ac antibody in KYSE150 and TE-11 cells. Four pairs of primers (P1-P4) specific for the TMPO promoter region were designed, and their sequences are shown at the bottom of Supplementary Fig. 5d. The results of qPCR analysis using P3 revealed that the TMPO promoter region was enriched by the anti-H3K27ac antibody (Fig. 5a, b). Furthermore, TMPO-AS1 silencing significantly reduced the H3K27ac level in the TMPO promoter region (Fig. 5a, b). Therefore, H3K27ac enrichment in the promoter region might be the reason for the upregulated expression of TMPO in ESCC cells.

Fig. 5. TAS1 regulates H3K27ac enrichment in the TMPO promoter by recruiting FUS and p300 to form condensates.

a, b Enrichment of the TMPO promoter by ChIP using an anti-H3K27ac antibody in KYSE150 and TE-11 cells with or without TAS1 KD were evaluated. The TMPO promoter level in the 10% input sample is set to 1. Primer locations in the TMPO promoter are shown at the bottom of Supplementary Fig. 5d. The primer set P3 was used to obtain the results shown (n = 3). c FUS in cell lysates was pulled down by biotin-labeled TAS1 but not its antisense RNA. d TAS1 binding proteins were detected using MS2-TRAP and WB analysis. TAS1-bound FUS was captured on anti-Flag antibody-conjugated affinity agarose beads; IP complexes were separated and identified using specific antibodies. e RIP assays indicated that TAS1 in ESCC cell lysates was enriched by FUS-specific antibodies. f, g ChIRP-purified DNA and proteins were analyzed using qPCR and western blotting, respectively. Odd, Even and Scr. denote the odd- and even-ranked corresponding probes for TAS1 and the negative control probes provided by RiboBio. The TMPO promoter region represented by P3 was enriched by the TAS1 probes. FUS and p300 proteins were also precipitated by the TAS1 probes in ESCC cells. The locations of the primers in the TMPO promoter are shown at the bottom of Supplementary Fig. 5d. h IF and FISH assays showed that TAS1, FUS and p300 were colocalized mostly in the nucleus and existed as puncta. Scale bar: 5 μm. i IF and FISH assays showed a reduction in the number of colocalized puncta formed by TAS1, FUS and p300 after TAS1 silencing in TE-11 cells. Scale bar: 5 μm. The data are presented as the mean±S.D. values. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

The molecular function of lncRNAs is closely associated with their subcellular localization23. We already determined that TMPO-AS1 was localized predominantly in the nucleus (Fig. 1f, g, Supplementary Fig. 1f). Nuclear lncRNAs have been reported to recruit chromatin-remodeling proteins to chromatin and thereby control transcriptional activity. NAT lncRNAs also perform their functions by interacting with RNA binding proteins (RBPs). To identify possible TMPO-AS1-interacting proteins, we performed a targeted screen of intranuclear RBPs and found that TMPO-AS1 was very likely to interact with the RBP FUS, with a probability of 0.9 (http://pridb.gdcb.iastate.edu/RPISeq/). FUS is a well-characterized RNA binding protein with various roles in different cellular processes, such as transcriptional regulation, RNA splicing, RNA transport, DNA repair and the DNA damage response24. FUS is able to phase separate and form biomolecular condensates with itself or other molecular partners, which drives aberrant chromatin looping and cancer development25. Then, we performed RNA pulldown followed by immunoblot analysis on ESCC cell lysates. The results validated the interaction between TMPO-AS1 and FUS (Fig. 5c). We also performed MS2-tagged RNA affinity purification (MS2-TRAP) and immunoblot analysis to further characterize the interaction between TMPO-AS1 and TMPO in situ. Coexpression of MS2-TMPO-AS1 and Flag-tag MS2 coat protein (MCP) led to significant enrichment of FUS by the anti-Flag antibody compared with the isotype control, indicating that FUS specifically binds to TMPO-AS1 (Fig. 5d). This observation was further confirmed by a RIP assay, where TMPO-AS1 was successfully enriched by the anti-FUS antibody (Fig. 5e). However, FUS expression did not change after TMPO-AS1 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Next, we performed a ChIRP assay, which is based on affinity capture of a target lncRNA-chromatin complex, with biotinylated ASO probes for TMPO-AS1 and subjected the precipitated products to qPCR and immunoblot analysis; the results indicated that TMPO-AS1 indeed bound to the promoter sequence of TMPO (Fig. 5f), and the immunoblot analysis further confirmed the direct binding between TMPO-AS1 and FUS (Fig. 5g). Taken together, these results indicate that the expression level of TMPO-AS1 does not affect the expression level of FUS in ESCC cells but influences FUS recruitment to the TMPO promoter.

FUS can form ribonucleoprotein complexes with lncRNAs and recruit the histone acetyltransferase complex to the TSS of target genes to regulate their transcription by interacting with HAT complex members, including p300, CBP, and TIP6026,27. Therefore, we performed co-IP with both anti-FUS and anti-p300 antibodies in ESCC cells. We first confirmed the direction of the interaction between FUS and p300 (Supplementary Fig. 5f). Furthermore, ChIRP followed by immunoblotting showed that p300 was enriched in the TMPO-AS1 probe group compared to the scrambled probe group (Fig. 5g). IF and FISH colocalization analyses showed that TMPO-AS1, FUS and p300 were colocalized in the nucleus, and they were observed as puncta, suggesting the formation of lncRNA-protein biomolecular condensates (Fig. 5h). Interestingly, TMPO-AS1 silencing evidently reduced the number of colocalized puncta (Fig. 5i), indicating that TMPO-AS1 is likely to facilitate the formation of biomolecular condensates with FUS and p300.

We intended to further identify the downstream factors of TMPO-AS1 and TMPO involved in ESCC progression. A qPCR array containing 12 genes associated with G1/S phase transition and 89 metastasis-related gene probes28 (Supplementary Table 8) was used to compare the mRNA expression profiles between TMPO-AS1-knockdown cells and control cells as well as between TMPO-knockdown cells and control cells as an approach to further identify downstream factors of TMPO-AS1 and TMPO involved in ESCC cell proliferation and metastasis. Interestingly, the expression of CyclinD1 and MTA1 was downregulated after knockdown of either TMPO-AS1 or TMPO (Supplementary Fig. 5g). Immunoblot analysis showed reduced expression of CyclinD1 and MTA1 in TMPO-AS1-silenced cells (Supplementary Fig. 5h). Rescue experiments indicated that the downregulation of CyclinD1 and MTA1 expression induced by TMPO-AS1 silencing was reversed by TMPO overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 5i). Collectively, these results reveal that TMPO-AS1 recruits FUS/p300 to the TMPO promoter and forms biomolecular condensates by direct binding, promoting H3K27ac and facilitating the transcription of TMPO, resulting in subsequent upregulation of CyclinD1 and MTA1, ultimately leading to ESCC tumor development.

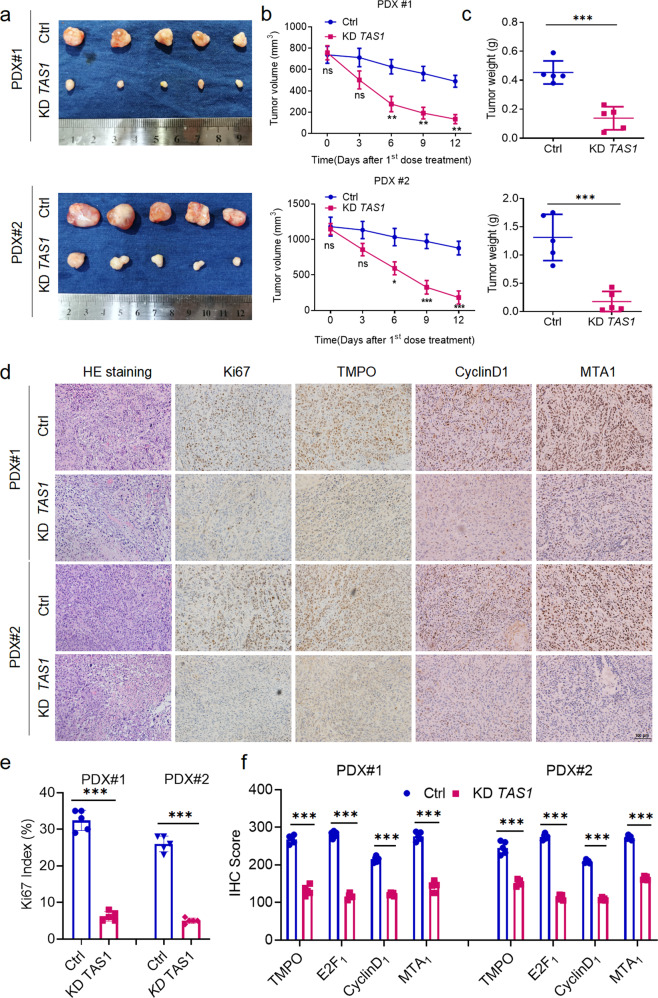

Effects of TMPO-AS1 targeting on ESCC tumors in vivo

To examine the therapeutic potential of targeting TMPO-AS1, we established PDX models derived from two patients diagnosed with ESCC at SYSUCC. We injected ASOs against TMPO-AS1 optimized in the in vitro study intratumorally into PDX-bearing BALB/c nude mice, which resulted in marked decreases in the tumor volume and tumor weight (Fig. 6a–c), suggesting the promising therapeutic potential of targeting TMPO-AS1. H&E staining of the excised tumors showed no obvious morphological differences between the treatment group and the control group (Fig. 6d). Immunohistochemical staining showed that TMPO-AS1 knockdown significantly impaired tumor proliferation, as indicated by the reduced Ki67 index (Fig. 6d, e). Accordingly, the expression levels of TMPO and the downstream proteins CyclinD1 and MTA1 were also obviously reduced, consistent with the results described above (Fig. 6d, f).

Fig. 6. TAS1 constitutes a potential therapeutic target in ESCC.

a Images of ex vivo tumors from the ESCC PDX model (n = 5). b, c Tumor volume curve and statistical analysis of the tumor weight of the PDX tumors. d Representative images of H&E staining and immunohistochemical staining for Ki67, TMPO, CyclinD1 and MTA1 in randomly selected PDX tumors from each group. Scale bar, 100 μm. e Statistical analysis of the Ki67 proliferation index (n = 5). f Statistical analysis of the immunohistochemical scores for the indicated genes (n = 5). The data are presented as the mean±S.D. values. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

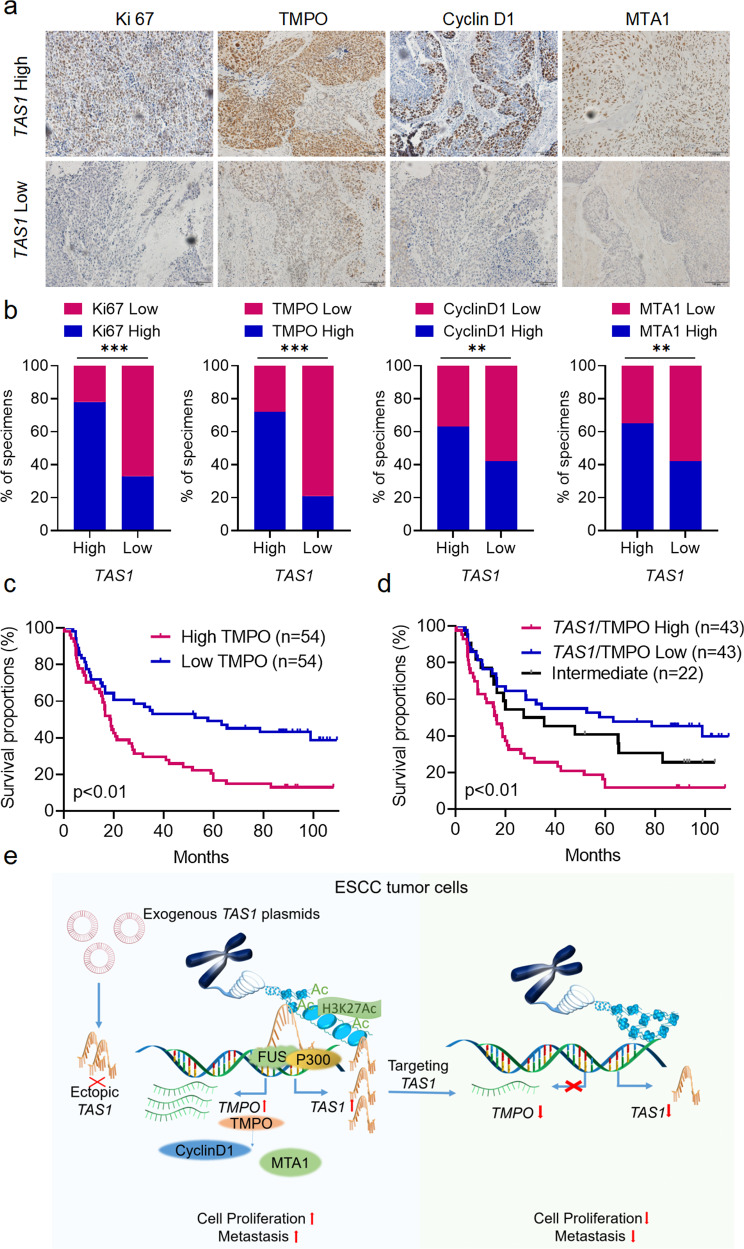

The TMPO-AS1/TMPO axis is associated with ESCC development

We used a cohort of ESCC tissues (SYSUCC, n = 108; clinicopathological information is provided in Supplementary Table 9) to analyze TMPO-AS1 expression using qPCR and to analyze TMPO, Ki67, CyclinD1, and MTA1 expression using IHC in order to collectively evaluate whether the TMPO-AS1/TMPO axis is clinically and pathologically relevant in ESCC. TMPO, Ki67, CyclinD1 and MTA1 were expressed at higher levels in the TMPO-AS1-high group than in the TMPO-AS1-low group (Fig. 7a, b), confirming the promoting effects of TMPO-AS1 on TMPO expression and ESCC progression.

Fig. 7. Clinical relevance of the TAS1/TMPO axis in ESCC.

a Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for Ki67, TMPO, CyclinD1 and MTA1 in tissues from patients with ESCC exhibiting low or high TAS1 expression. Scale bar, 100 µm. b Percentage of specimens with low or high Ki67, TMPO, CyclinD1 and MTA1 expression in the low and high TAS1 expression groups (SYSUCC, n = 108, chi-square test, two-sided). c Kaplan–Meier analysis of OS for patients with ESCC (SYSUCC) exhibiting low (n = 54) or high (n = 54) TMPO expression (log-rank test, two-sided). d Kaplan–Meier analysis of OS for patients with ESCC (SYSUCC) exhibiting low (low expression of both TAS1 and TMPO, n = 43), high (high expression of both TAS1 and TMPO, n = 43) or intermediate (n = 22) TAS1/TMPO expression (log-rank test, two-sided). e Graphical abstract showing that the lncRNA TAS1 activates TMPO transcription in cis by recruiting FUS and p300 to modulate H3K27ac modification in the promoter region and that targeting TAS1 attenuates ESCC progression. The data are presented as the mean ± S.D. values. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Furthermore, we analyzed the clinical relevance of TMPO to patient outcomes. The correlations between TMPO expression and clinicopathological features are shown in Supplementary Table 10. Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that high TMPO expression was associated with poor outcomes in patients with ESCC (Fig. 7c). Then, according to qPCR analysis of TMPO-AS1 and immunohistochemical staining of TMPO, the samples were classified into the TMPO-AS1/TMPO-high, TMPO-AS1/TMPO-intermediate, and TMPO-AS1/TMPO-low groups, and the patients in the TMPO-AS1/TMPO-high subgroup had the worst prognosis among the three groups (Fig. 7d). In summary, these data further indicated that TMPO-AS1/TMPO potentially constitute promising prognostic indicators and therapeutic targets in ESCC.

Discussion

ESCC is a predominant histological subtype of esophageal malignancy, especially in Asia. More than 90% of esophageal cancer cases in the East Asian region are ESCC29. With the development of cancer therapies, the survival of patients with ESCC has improved. However, the overall therapeutic effect is poor due to the lack of promising targets, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 10% for patients with advanced disease. Therefore, studies aiming to further elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of ESCC are urgently needed. Recently, lncRNAs have emerged as important epigenetic regulators that play essential roles in various physiological and pathological processes30,31. The functions and mechanisms of lncRNAs have been increasingly appreciated in different cancers32. For example, lncRNAs have been reported to be associated with diverse pathological functions, including tumor proliferation, metastasis, angiogenesis, metabolism, and microenvironmental remodeling12,33,34. Therefore, we intended to identify functionally essential lncRNAs in ESCC by performing phenotypic screening of aberrantly expressed lncRNAs using a siRNA library based on TCGA transcriptomic data. TMPO-AS1, an antisense lncRNA of TMPO located on chromosome 12q23.1, was the candidate with the most potent suppressive effects in our screen. TMPO-AS1 expression was upregulated in ESCC, and high TMPO-AS1 expression indicated poor prognosis in patients with ESCC (Fig. 1).

Recent studies have reported that various lncRNAs are abnormally expressed and have crucial functions in ESCC. For example, Zhang et al. revealed that the lncRNA DNM3OS regulates the DNA damage response, which results in radioresistance during ESCC treatment9. A study by Li et al. showed that the long intergenic noncoding RNA POU3F3 promotes ESCC tumor growth by interacting with EZH2 to increase the methylation of POU3F3 and reduce POU3F3 expression35. TMPO-AS1 expression has been reported to be upregulated in various cancers, including bladder cancer, pancreatic cancer, and lung adenocarcinoma36–38. However, the role of TMPO-AS1 in ESCC is less understood. In this study, we reported that TMPO-AS1 promotes tumor progression through activation of TMPO transcription in cis in ESCC. Functionally, TMPO-AS1 promoted ESCC cell proliferation and metastasis both in vitro and in vivo (Figs. 2, 3). Mechanistically, TMPO-AS1 performed its function by activating TMPO transcription in cis (Figs. 4, 5). TMPO-AS1 promoted TMPO transcription by recruiting FUS and p300 and forming condensates in situ to acetylate lysine 27 of histone 3 in the TMPO promoter (Fig. 5). TMPO, also termed lamina-associated polypeptide 2 (LAP2), is the cognate neighboring gene of TMPO-AS1 located on chromosome 12q21.2, and 6 nuclear isoforms can be produced through alternative splicing. Evidence suggests important roles for TMPO in various cancers—TMPO expression is upregulated in non-small-cell lung cancer18, glioblastoma39, and digestive tract carcinomas21, although little is known about its role in ESCC.

Among the various types of lncRNAs, NAT lncRNAs are attracting increasing attention. NAT lncRNAs are widespread in the genomes of diverse species, including humans40,41. These NATs and their cognate genes often show concordant or discordant expression patterns42. Diverse transcriptional or posttranscriptional mechanisms have been associated with the ability of NATs to regulate the expression of their sense transcripts. Cis-acting NAT lncRNAs serve as scaffolds to recruit chromatin-modulating proteins to facilitate DNA methylation, histone modification, and chromatin remodeling, ultimately leading to activated transcription of the cognate gene. NAT lncRNAs may compete with their sense transcripts for binding of RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) and regulatory transcription factors, resulting in transcriptional interference. Trans-acting NAT lncRNAs may affect mRNA stability or modulate protein translation.

For the first time, we reported the transcriptional activation of TMPO mediated by TMPO-AS1 (Fig. 7e). Li et al. reported that TMPO-AS1 promotes thyroid cancer cell proliferation by sponging miR-498 to increase TMPO expression43. Here, we found that TMPO-AS1 acts in cis to activate TMPO expression at the transcriptional level. The difference in the mechanism by which TMPO-AS1 regulates TMPO expression might be tissue specific. The model we proposed echoes the roles played by the lncRNA SATB homeobox 2 antisense RNA 1 (SATB2-AS1) in promoting SATB2 expression12, the lncRNA homeobox A cluster (HOXA) transcript at the distal tip (HOTTIP) in activating HOXA gene expression44, and the lncRNA HEAL in regulating HIV-1 replication26. However, the underlying mechanisms employed by these lncRNAs are different. For example, HOTTIP interacts with WDR5 and recruits the MLL complex to maintain H3K4me3 and activate HOXA gene transcription. However, HOTTIP requires chromosome looping to bring the HOTTIP locus spatially closer to its target genes for its cis-regulatory action44. The different mechanisms might be due to differences in the distances between the TSSs of NAT lncRNAs and their cognate genes. As exemplified by TMPO-AS1, the expression of some lncRNAs is correlated with that of their sense protein-coding genes (Fig. 4). This finding may reflect the observation that NAT lncRNAs are essential for regulating the expression of their paired genes, suggesting that this cis-regulatory mechanism might be universal for NAT lncRNAs.

LncRNAs are attracting increasing attention as novel therapeutic targets, especially in cancer45. Treatments targeting lncRNAs have also become feasible due to technological developments45–47. For example, some ASO-based therapies have recently been evaluated in clinical trials48. With the successful application of RNA-based vaccinations against COVID-19, the prospects of RNA-based therapeutics are promising. The results of in vivo targeted therapy in the PDX model revealed the potential of TMPO-AS1 as an effective therapeutic target in ESCC (Fig. 6). Our work showed that the expression of both TMPO-AS1 and TMPO was upregulated in ESCC and that high expression of either TMPO-AS1 or TMPO was strongly associated with unfavorable patient outcomes. Furthermore, high expression of both TMPO-AS1 and TMPO was associated with even worse prognosis, suggesting that the combination of both genes might constitute a more potent prognostic marker in patients with ESCC (Figs. 1, 7).

In summary, our current study showed that TMPO-AS1 expression was upregulated in ESCC and that high TMPO-AS1 expression was associated with poor prognosis. TMPO-AS1 promotes ESCC cell proliferation and metastasis by activating TMPO transcription in cis. These data suggest that TMPO-AS1 and TMPO may be novel biomarkers and promising diagnostic and therapeutic targets in ESCC. However, further studies must be performed to elucidate the precise molecular mechanisms by which TMPO might regulate cancer cell proliferation and metastasis in ESCC.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFF1201300), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81930065 and 82073112), the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong (2019B020227002), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (201904020046, and 201803040019), the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2019-I2M-5-036), the Guangdong Esophageal Cancer Institute Science and Technology Program (M201911 and M202003), The Postdoctoral Innovative Talent Support Program (BX2021389), and the Guangzhou Science and Technology Program, Basic and Applied Basic Research Project (202102020188).

Author contributions

Z.-L.Z., Z.-X.L., H.-Y.L. and X.-J.L. designed the study. X.-J.L., M.-M.H., J.L., and J.-B.Z. collected the data. X.-J.L., M.-M.H., J.L., J.-B.Z., Q.-N.W., Q.M., Z.-L.Z., Z.-X.L., and H.-Y.L. analyzed and interpreted the data. X.-J.L., Q.-N.W., Y.-X.C. and J.L. performed the statistical analysis. R.-H.X., K.-J.L., D.-L.C. and Z.-L.Z. provided administrative, technical, or material support. X.-J.L., Z.-L.Z., Z.-X.L. and H.-Y.L. wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Data availability

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary files.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The clinical ESCC specimens were used with permission from the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, China. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Animal Care of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, China.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xiao-Jing Luo, Ming-Ming He, Jia Liu, Jia-Bo Zheng.

Contributor Information

Zhao-Lei Zeng, Email: zengzhl@sysucc.org.cn.

Ze-Xian Liu, Email: liuzx@sysucc.org.cn.

Hui-Yan Luo, Email: luohy@sysucc.org.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s12276-022-00791-3.

References

- 1.Bray F, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016;66:115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:2241–2252. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. et al. Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature. 2017;541:169–175. doi: 10.1038/nature20805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kopp F, Mendell JT. Functional classification and experimental dissection of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2018;172:393–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beermann J, Piccoli MT, Viereck J, Thum T. Non-coding RNAs in development and disease: background, mechanisms, and therapeutic approaches. Physiol. Rev. 2016;96:1297–1325. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan YT, et al. LncRNA-mediated posttranslational modifications and reprogramming of energy metabolism in cancer. Cancer Commun. 2020;41:109–120. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiang X, et al. Cellular senescence in hepatocellular carcinoma induced by a long non-coding RNA-encoded peptide PINT87aa by blocking FOXM1-mediated PHB2. Theranostics. 2021;11:4929–4944. doi: 10.7150/thno.55672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast-promoted LncRNA DNM3OS confers radioresistance by regulating DNA damage response in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:1989–2000. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, et al. Long noncoding RNA AGPG regulates PFKFB3-mediated tumor glycolytic reprogramming. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1507. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15112-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katayama S, et al. Antisense transcription in the mammalian transcriptome. Science. 2005;309:1564–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.1112009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu M, et al. LncRNA SATB2-AS1 inhibits tumor metastasis and affects the tumor immune cell microenvironment in colorectal cancer by regulating SATB2. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:135. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1063-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao X, et al. Global identification of Arabidopsis lncRNAs reveals the regulation of MAF4 by a natural antisense RNA. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:5056. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07500-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu QN, et al. MYC-activated LncRNA MNX1-AS1 promotes the progression of colorectal cancer by stabilizing YB1. Cancer Res. 2021;81:2636–2650. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito T, et al. Pituitary tumor-transforming 1 increases cell motility and promotes lymph node metastasis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3214–3224. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts TC, et al. Quantification of nascent transcription by bromouridine immunocapture nuclear run-on RT-qPCR. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:1198–1211. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu, C., Quinn, J. & Chang, H. Y. Chromatin isolation by RNA purification (ChIRP). J. Vis. Exp. 10.3791/3912 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Liu C, et al. Prognostic significance and biological function of Lamina-associated polypeptide 2 in non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:3817–3827. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S179870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parise P, et al. Lap2alpha expression is controlled by E2F and deregulated in various human tumors. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1331–1341. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.12.2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirza AN, et al. LAP2 proteins chaperone GLI1 movement between the lamina and chromatin to regulate transcription. Cell. 2019;176:198–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HJ, et al. LAP2 is widely overexpressed in diverse digestive tract cancers and regulates motility of cancer cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang MH, et al. Nuclear lncRNA HOXD-AS1 suppresses colorectal carcinoma growth and metastasis via inhibiting HOXD3-induced integrin beta3 transcriptional activating and MAPK/AKT signalling. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:31. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0955-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winkler L, Dimitrova N. A mechanistic view of long noncoding RNAs in cancer. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2022;13:e1699. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamaguchi A, Takanashi K. FUS interacts with nuclear matrix-associated protein SAFB1 as well as Matrin3 to regulate splicing and ligand-mediated transcription. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:35195. doi: 10.1038/srep35195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahn JH, et al. Phase separation drives aberrant chromatin looping and cancer development. Nature. 2021;595:591–595. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03662-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chao TC, et al. The long noncoding RNA HEAL regulates HIV-1 replication through epigenetic regulation of the HIV-1 promoter. MBio. 2019;10:e02016–e02019. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02016-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, et al. Induced ncRNAs allosterically modify RNA-binding proteins in cis to inhibit transcription. Nature. 2008;454:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature06992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen ZH, et al. Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A2 promotes experimental metastasis and oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38:196. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:2137–2150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Batista PJ, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell. 2013;152:1298–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harries LW. Long non-coding RNAs and human disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012;40:902–906. doi: 10.1042/BST20120020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huarte M. The emerging role of lncRNAs in cancer. Nat. Med. 2015;21:1253–1261. doi: 10.1038/nm.3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, et al. LncRNA LINRIS stabilizes IGF2BP2 and promotes the aerobic glycolysis in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:174. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1105-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sang L, et al. Mitochondrial long non-coding RNA GAS5 tunes TCA metabolism in response to nutrient stress. Nat. Metab. 2021;3:90–106. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-00325-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li W, et al. Increased levels of the long intergenic non-protein coding RNA POU3F3 promote DNA methylation in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1714–1726. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xue F, et al. Long non-coding RNA TMPO-AS1 serves as a tumor promoter in pancreatic carcinoma by regulating miR-383-5p/SOX11. Oncol. Lett. 2021;21:255. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.12517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, et al. The long non-coding RNA TMPO-AS1 promotes bladder cancer growth and progression via OTUB1-induced E2F1 deubiquitination. Front. Oncol. 2021;11:643163. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.643163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang A, et al. Identification and validation of an autophagy-related long non-coding RNA signature as a prognostic biomarker for patients with lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021;13:720–734. doi: 10.21037/jtd-20-2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, et al. Depletion of thymopoietin inhibits proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest/apoptosis in glioblastoma cells. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2016;14:267. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-1018-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Liu XS, Liu QR, Wei L. Genome-wide in silico identification and analysis of cis natural antisense transcripts (cis-NATs) in ten species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3465–3475. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng J, et al. Transcriptional maps of 10 human chromosomes at 5-nucleotide resolution. Science. 2005;308:1149–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.1108625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen J, et al. Genome-wide analysis of coordinate expression and evolution of human cis-encoded sense-antisense transcripts. Trends Genet. 2005;21:326–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Z, et al. TMPO-AS1 promotes cell proliferation of thyroid cancer via sponging miR-498 to modulate TMPO. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20:294. doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01334-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang KC, et al. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature. 2011;472:120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature09819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esposito R, et al. Hacking the cancer genome: profiling therapeutically actionable long non-coding RNAs using CRISPR-Cas9 screening. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:545–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe S, et al. In vivo rendezvous of small nucleic acid drugs with charge-matched block catiomers to target cancers. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1894. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09856-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bester AC, et al. An integrated genome-wide CRISPRa approach to functionalize lncRNAs in drug resistance. Cell. 2018;173:649–664. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adams BD, et al. Targeting noncoding RNAs in disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:761–771. doi: 10.1172/JCI84424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary files.