Abstract

Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis is a DNA polymorphism assay commonly used for fingerprinting genomes. After optimizing the reaction conditions, samples of Escherichia coli H10407 DNA were assayed to determine the influence of osmotic and/or oligotrophic stress on variations in RAPD banding patterns. Genetic rearrangements or DNA topology variations could be detected as changes in agarose gel electrophoresis banding profiles. A new amplicon generated using DNA extracted from bacteria prestarved by an osmotic stress and resuscitated in rich medium was observed. Enrichment improved recovery of mutator cells and allowed them to be detected in samples, suggesting that DNA modifications, such as stress-induced alterations and supercoiling phenomena, should be taken into consideration before beginning RAPD analyses.

Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) (27), arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR) (26), and DNA-amplified fingerprinting (1) analyses involve the amplification of anonymous segments of genomic DNA by PCR techniques using oligonucleotide primers constructed in the absence of any knowledge about the target DNA sequence. These techniques can be applied to intraspecific strain differentiation (identification and taxonomy) based on the detection of polymorphisms in amplified DNA (2, 17, 20), the detection of interspecific gene flow, the assessment of kinship relationships, the analysis of mixed genome samples, and the production of specific probes (9, 15, 18, 19).

Enterobacteriaceae respond to various stimuli such as oxidative stress, pH extremes, anaerobiosis, heat shock, osmotic shock, and starvation by changing the expression of groups of genes coding for proteins involved in adaptation (3). The response of Escherichia coli during the transition phase from growth to stasis includes sequential changes in the pattern of gene expression. We report here the use of RAPD analysis to assess the impact of an osmotic stress and nutrient-limited conditions on the E. coli genome. Reproductive variations in RAPD banding profiles suggest that these conditions induce molecular genomic reorganization.

The enterotoxigenic E. coli H10407 (serotype 078:K80:H11) strain was used (6). Bacteria were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (AES Laboratories, Combourg, France) for 15 h at 37°C. An overnight culture was inoculated into BHI broth (1‰ inoculum) and grown to the log (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.6, e) and stationary phase (OD600 = 1.3, s). Cells were harvested by centrifugation (4,000 × g for 10 min) and washed twice in filtered, autoclaved distilled water. Four different flasks of sterilized artificial seawater (ASW) (Instant Ocean, Sarrebourg, France) and distilled water (DW) were inoculated with 6 × 107 ml−1 total washed bacterial cells and incubated at 15°C with gentle shaking. Cells were periodically monitored by plate counts on Trypticase soy agar (AES Laboratories). Total counts were determined by acridine orange direct count (AODC) (10) and viable but nonculturable (VNC) bacteria by direct viable count (DVC) (11).

Volumes containing 105 E. coli H10407 cells grown in BHI broth, and then starved in ASW or DW were harvested at 4,000 × g for 10 min. DNA was extracted using sodium dodecyl sulfate (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) and proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim, Meylan, France) as described by Smith et al. (23). The cells starved in ASW or in DW were pelletted after 1 and 18 h.

Resuscitation experiments were conducted in BHI broth on exponential- and stationary-phase cells starved in ASW for 18 h. Exponential-phase bacteria stressed in ASW for 18 h, entering the VNC state by oligotrophic and osmotic shock, were resuscitated in rich medium (1% inoculum). The surviving cells were able to grow and multiply. DNA from resuscitated cells was extracted from bacteria grown to OD600s of 0.6 and 1.3.

RAPD fingerprinting was performed as previously described (27). Briefly, 20 10-base primers from the Z Kit (Operon Technologies, Alameda, Calif.) were tested, and OPZ-13 (5′ GACTAAGCCC 3′) was selected. This primer was chosen because it gave more reproducible and more informative profiles in preliminary tests. The relative intensities and the sizes of the bands were highly reproducible in repeated experiments done under the same conditions. PCR was carried out in a 25-μl volume containing 25 ng of E. coli total DNA; 2 mM MgCl2; 30 pmol of primer; 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega); 0.1 mM (each) dCTP, dGTP, dATP, and dTTP (Boehringer Mannheim) in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3) containing 50 mM KCl; 0.001% gelatin (Sigma); and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma). The mixture was overlaid with mineral oil (Sigma-Aldrich). Negative controls were included (no template DNA). A Hybaid thermal cycler was used for three ramping cycles (94°C for 1 min, 45°C for 1 s, 32°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min) followed by 27 cycles (94°C for 1 min, 32°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min), and completed with one 10-min cycle at 72°C. Each experiment was repeated three times to verify band pattern reproducibility. After PCR, the RAPD patterns were compared by horizontal electrophoresis of 12-μl aliquots in 1.8% SeaKem GTG agarose gel (FMC, Rockland, Maine) containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide (Sigma) per ml in 0.04 M Tris-acetate (Merck)–0.002 M EDTA, pH 8.5 (Merck), and photographed on a UV transilluminator. MVII and MVIII DNA ladders (Boehringer-Mannheim) were used as molecular size markers in all gels.

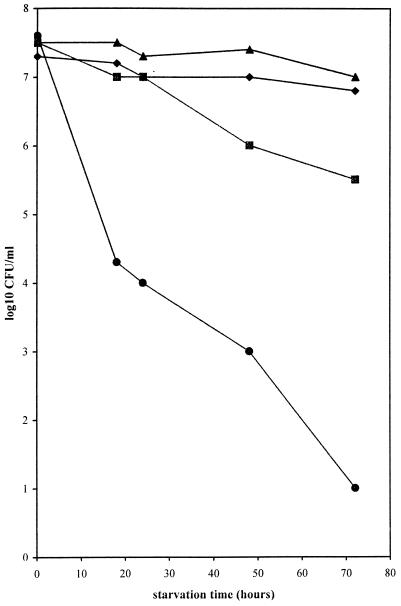

Bacteria were first grown to the exponential phase in rich medium, inoculated into ASW (osmotic and oligotrophic stress), resuscitated in the same rich medium, and grown to the stationary phase. To compare the influence of the physiological state of the bacteria prior to the stress, the same experiment was performed with bacteria first grown to the stationary phase in rich medium. Stationary phase E. coli cultures were more resistant to osmotic stress than mid-log-phase cultures, as expected (7). Exponential-phase E. coli cells starved by inoculation in ASW were no longer detectable by plate counts after 3 days. However, total counts remained constant as measured by the AODC technique. The bacteria were VNC as measured by the DVC technique (Fig. 1). Concurrent experiments, with DW replacing the ASW (oligotrophic stress only), produced the same counts as with stationary-phase bacteria. Regrowth in BHI broth was as easy and quick in the two cases where the bacteria were not subjected to the stress.

FIG. 1.

Survival curves of exponential- and stationary-phase cells of E. coli H10407, starved in ASW. AODC for stationary or exponential phase (▴), DVC for stationary or exponential phase (♦), and plate counts on Trypticase soy agar for stationary phase (▪) and exponential phase (●) are shown.

Samples of bacterial DNA (extracted from bacteria in both the log and stationary phases) were assayed after 1 and 18 h of incubation to determine whether osmotic and/or oligotrophic stress could induce variations in RAPD banding patterns. The DNA was extracted and purified to protect it from breakage during the autolysis process. The amounts of DNA used to generate RAPDs were optimized to ensure reproducibility.

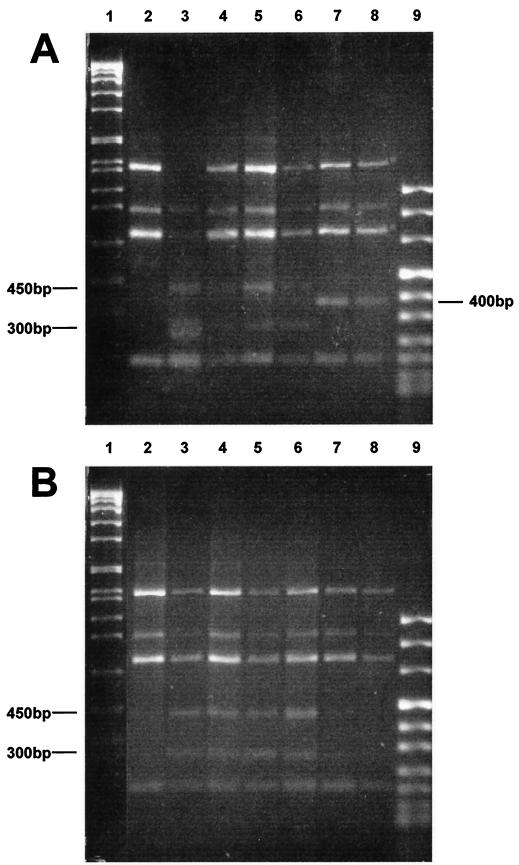

Following amplification, the RAPDs were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2). Several DNA segments were amplified in each sample (200 to 1,500 bp), and variations were apparent in several patterns. No variations were seen between bacteria grown to the log or stationary phase in rich medium (BHI broth) (Fig. 2, lanes 2). RAPD profiles obtained with starved cells (oligotrophic stress with or without osmotic stress) were different from those obtained from BHI broth-grown cells, with two additional bands of approximately 300 and 450 bp showing up (Fig. 2, lanes 3 to 6). Banding patterns from cells stressed in ASW or DW during the stationary phase were identical (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 to 6). On the other hand, bacteria subjected to osmotic and oligotrophic stress during the exponential phase produced altered RAPD profiles when the DNA was extracted 1 h after the stress. The dominant slow band of about 1,500 bp was missing and there were two new bands of approximately 300 bp (Fig. 2A, lane 3). No differences were noted with DNA extracted in the other cases (Fig. 2A, lanes 4 to 6). Following the stress, resuscitation in rich medium could either restore the pre-stress pattern or alter it. When stationary-phase bacteria were stressed, the RAPD banding patterns of the resuscitated bacteria (Fig. 2B, lanes 7 and 8) were restored to the prestress state (Fig. 2B, lane 2). However, when log-phase bacteria were stressed, the RAPD banding patterns of the resuscitated bacteria (Fig. 2A, lanes 7 and 8) were altered, with a new 400-bp fragment appearing compared to the prestress pattern.

FIG. 2.

Electrophoretic agarose gel analysis of RAPD products from total DNA extracted from E. coli H10407. The DNA was extracted from bacteria in different physiological states: exponential phase (A) and early stationary phase (B). Lanes 1, MVII DNA ladder; lanes 2, cells grown in BHI broth; lanes 3 and 5, bacteria stressed in ASW for 1 and 18 h, respectively; lanes 4 and 6, bacteria stressed in DW for 1 and 18 h, respectively; lanes 7 and 8, Bacteria stressed in ASW for 18 h then resuscitated and grown to the exponential and stationary phases respectively; lanes 9, MVIII DNA ladder.

In the work reported here, RAPD products were amplified using DNA from bacterial cells subjected to various stresses. No differences were noted between the RAPD profiles of stationary- and exponential-phase bacteria grown in BHI broth. A number of studies have reported increased movement of IS elements in the stationary phase compared to the log phase (12, 24). IS elements are good targets for RAPD (27). Variations between the two growth phases should thus have been detected. This lack of sensitivity, which may be due to the low resolution of gel electrophoresis, may be useful in the sense that the primer would only detect major genetic rearrangements.

Altered banding patterns were obtained from log-phase cells stressed in ASW when the DNA was extracted 1 h after the osmotic stress, while no differences were seen when the DNA was extracted after 18 h, suggesting that more genetic rearrangements occurred immediately following the osmotic stress. Alterations in RAPD profiles were also seen in stressed bacteria that were resuscitated in rich medium. It is quite difficult to interpret this result, since in one case the banding pattern of the stressed bacteria was restored (stationary-phase bacteria) and in the other, it was not. There are many possible explanations for what appears to be genetic rearrangements in very small populations of viable cells. Unexpected accelerations in mutation rates during nutritional deprivation have already been observed, with the mutated cells able to grow and take over the culture (28). AP-PCR has already been successfully used to detect alterations in DNA patterns in progeny descended from α-irradiated fish (13). Genomic mutations may also produce novel bands, but high mutation rates (7 to 9% per band per generation) would be necessary to generate new banding patterns (21) resulting from the proliferation of phenotype-deficient mutators in rich medium (14). Growing E. coli to the stationary phase could help prevent genetic alterations linked, at least in part, to the topological state of their DNA (8). Structural changes, such as the extrusion of cruciforms, are also strongly influenced by DNA supercoiling (5) and temperature or ionic strength (4, 16). In some cases, cells can undergo extensive genomic reorganization with one or two generations. They also have intricate repair systems to prevent genetic change caused by sporadic physicochemical damage (22). The sensitivity of all cells is highest when they are starved during the early log phase (7), as shown in our experiments. On the other hand, genomic plasticity is one of many mechanisms for maintaining viability during periods when conditions are not propitious for logarithmic growth and has allowed bacteria to survive for billions of years despite widespread environmental upheavals. Warner and Oliver (25) noted variations in the RAPD profiles of stationary-phase Vibrio vulnificus cells, subjected to starvation in ASW, with loss of RAPD amplification products by 4 h of starvation. The signal was therefore regained by the addition of nutrients to the microcosm. The same loss of signal was observed as cells entered the VNC state after a temperature downshift. VNC cells were resuscitated by a temperature upshift and were once again detectable by the RAPD method. The authors suggested that a combination of supercoiling and DNA binding proteins could play a role in the VNC response (25). We agree with this hypothesis, although we noted the appearance of new bands following resuscitation in nutrient broth, indicating that genetic changes are very specific and intricate, with slight variations occurring because of differences in environmental and growth conditions and sampling times.

RAPDs can be used to define genetic relationships between organisms in evolutionary, phylogenetic, and taxonomic studies. However, DNA rearrangements result in changes in primer sites that sometimes manifest themselves as the presence or absence of DNA fragments. All causes of DNA alterations, including stress, should be taken into consideration before beginning an RAPD analysis to study phenotypic variations among species.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caetano-Anolles G, Bassam B J, Gresshoff P M. DNA amplification fingerprinting using very short arbitrary oligonucleotide primers. Bio/Technology. 1991;9:553–557. doi: 10.1038/nbt0691-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cave H, Bingen E, Elion J, Denamur E. Differentiation of Escherichia coli strains using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. Res Microbiol. 1994;145:141–150. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Csonka L N, Hanson A D. Procaryotic osmoregulation: genetics and physiology. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:569–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dayn A, Malkhosyan S, Duzhy D, Lyamichev V, Panchenko Y, Mirkin S. Formation of (dA-dT)n cruciforms in Escherichia coli cells under different environmental conditions. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2658–2664. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2658-2664.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drlica K. Control of bacterial DNA supercoiling. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans D J, Jr, Evans D G. Three characteristics associated with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from man. Infect Immun. 1973;8:322–328. doi: 10.1128/iai.8.3.322-328.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gauthier M J, Munro P M, Breittmayer V A. Influence of prior growth conditions on low nutrient response of Escherichia coli in seawater. Can J Microbiol. 1989;35:379–383. doi: 10.1139/m89-058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gauthier M J, Labedan B, Breittmayer V A. Influence of DNA supercoiling on the loss of culturability of Escherichia coli cells incubated in seawater. Mol Ecol. 1992;1:183–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1992.tb00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadrys H, Balick M, Schierwater B. Application of random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) in molecular ecology. Mol Ecol. 1992;1:55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1992.tb00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobbie J E, Daley R J, Jasper S. Use of Nucleopore filters for counting bacteria by fluorescence microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;33:1225–1228. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.5.1225-1228.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kogure K, Simidu U, Taga N. A tentative direct microscopic method for counting living marine bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1979;25:415–420. doi: 10.1139/m79-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolter R. Life and death in stationary-phase cultures of E. coli reveal answers—and more questions—about cell viability. ASM News. 1992;58:75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubota Y, Shimada A, Shima A. DNA alterations detected in the progeny of paternally irradiated Japanese mekada fish (Oryzias latipes) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:330–334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mao E F, Lane L, Lee J, Miller J H. Proliferation of mutators in a cell population J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:417–422. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.417-422.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Murcia A J, Rodriguez-Valera F. The use of arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR) to develop taxa specific DNA probes of known sequence. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;124:265–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClellan J A, Boublikova P, Palecek E, Lilley D M J. Superhelical torsion in cellular DNA responds directly to environmental and genetic factors Proc. Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8373–8377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ménard C, Mouton C. Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis confirms the biotyping scheme of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Res Microbiol. 1993;144:445–455. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ménard C, Mouton C. Clonal diversity of the taxon Porphyromonas gingivalis assessed by random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2522–2531. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2522-2531.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ménard C, Gosselin P, Duhaime J-F, Mouton C. Polymerase chain reaction using arbitrary primers for the design and construction of a DNA probe specific for Porphyromonas gingivalis. Res Microbiol. 1994;145:595–602. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pacheco A B F, Guth B E C, De Almeida, Ferreira L C S. Characterization of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli by random amplification of polymorphic DNA. Res Microbiol. 1996;147:175–182. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)80217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riedy M F, Hamilton III W J, Aquadro C F. Excess of non-parental bands in offspring from known primate pedigrees assayed using RAPD PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:8. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.4.918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shapiro J A. Natural genetic engineering in evolution. Genetics. 1992;86:99–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00133714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith G L F, Socransky S S, Smith C M. Rapid method for purification of DNA from subgingival microorganisms. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1989;4:47–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1989.tb00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tormo A, Almiron M, Kolter R. surA, an Escherichia coli gene essential for survival in stationary phase. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4339–4347. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4339-4347.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warner J M, Oliver J D. Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis of starved and viable but nonculturable Vibrio vulnificus cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3025–3028. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.3025-3028.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welsh J, McClelland M. Fingerprinting genomes using PCR with arbitrary primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:7213–7218. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams J G K, Kubelik A R, Livak K J, Rafalski J A, Tingey S V. DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6531–6535. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zambrano M M, Siegele D A, Almiron M, Tormo A, Kolter R. Microbial competition: Escherichia coli mutants that take over stationary phase cultures. Science. 1993;259:1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.7681219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]