People with HIV who take antiretroviral therapy as prescribed, and achieve and maintain viral suppression, improve their health and life expectancy. 1 They also have effectively no risk of sexually transmitting the virus to an HIV-negative partner. 2 As of 2018, only 64.7% of people with diagnosed HIV in the United States were virally suppressed. 3 To achieve national goals to end the HIV epidemic, it is critical to address barriers experienced by subpopulations with persistent gaps along the HIV care continuum of linkage to and retention in care, treatment adherence, and viral suppression. 4 Although evidence-informed interventions to improve HIV health outcomes among priority populations exist, the uptake of such interventions in HIV service organizations is slow. To increase scale-up, organizations need more centralized dissemination of interventions with demonstrated effectiveness in real-world settings, as well as sufficient detail and supporting materials for intervention replication by service delivery staff members. 5,6

We describe the application of a novel rapid implementation approach developed by the Health Resources & Services Administration HIV/AIDS Bureau (HRSA HAB) to accelerate the scale-up of intervention strategies in HIV service organizations nationally. 7 One of the first projects to apply rapid implementation is “Using Evidence-Informed Interventions to Improve Health Outcomes Among People Living With HIV (E2i),” a 4-year (2017-2021) initiative designed to improve outcomes and reduce disparities along the HIV care continuum for people with HIV served by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. More than half of all people with diagnosed HIV in the United States receive direct medical care and supportive services from organizations funded by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. 8 Among Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program clients receiving medical care in 2018, 87.1% were virally suppressed; however, disparities persist for several subpopulations, including Black men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender women, and people with mental health and substance use disorders. 8

Broadly speaking, rapid implementation involves (1) systematically identifying intervention strategies with demonstrated effectiveness at improving outcomes for people with HIV, (2) piloting intervention strategies in organizations funded by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program to inform tailoring of the intervention strategies and assess their impact on client outcomes in a real-world setting, and (3) disseminating the strategies through multimedia toolkits for national rapid replication. Rapid implementation uses an implementation science evaluation to measure client outcomes and implementation strategies that drive successful uptake and organizational integration of an intervention. For this article, we highlight the first 2 steps of E2i’s unique rapid implementation process and how this approach was used to select 11 evidence-informed intervention strategies to pilot among 26 organizations funded by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program in diverse cities with high HIV prevalence. We conclude with a discussion of lessons learned and implications for future public health projects that may apply a similar approach.

Focus Areas

An initial review of client-level data from the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program and national epidemiologic evidence informed the decision to identify interventions in 4 focus areas: (1) improving HIV health outcomes for transgender women, (2) improving HIV health outcomes for Black MSM, (3) integrating behavioral health with primary medical care for people with HIV, and (4) identifying and addressing trauma among people with HIV. Transgender women and Black MSM, especially those aged 13-24, have a disproportionate prevalence of HIV. 9 -11 Social and structural determinants of health, including stigma and discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity, race/ethnicity, and HIV status, contribute to poor HIV health outcomes in these communities. 12,13 For example, experiences of stigma can lead to social marginalization, mistrust of medical institutions, and vulnerability to behavioral health problems, all of which impede engagement in care and treatment adherence. 13 -15 Promising interventions for Black MSM and transgender women include interventions that build self-efficacy, address structural barriers to care specific to the local population, 16 and provide culturally tailored programs that affirm sexual and gender minority identities. Examples of such intervention strategies include reducing scheduling barriers through co-located services, extended hours, and appointment reminders; increasing trust and cultural responsiveness by hiring peers (eg, people with HIV who are transgender women or Black MSM) to provide mentorship and navigation; and promoting self-efficacy through motivational interviewing and strengths-based case management. 16,17

Among all people with HIV, trauma exposure, substance use disorders, depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric disorders are highly prevalent and undertreated. 18,19 Behavioral health comorbidities impede the ability of people with HIV to maintain treatment adherence and continuous care. 19,20 Despite the well-established need to identify and treat trauma and behavioral health disorders among people with HIV, few organizations have adopted a systems-wide approach to do so. 21,22 Integrating trauma-informed care 19 and behavioral health services into community-based HIV primary care has the potential to reduce stigma, facilitate access to care, and increase the availability of cognitive–behavioral strategies that increase medication adherence. 23,24

Rapid Implementation Steps

In August 2017, The Fenway Institute (Boston, MA), in partnership with AIDS United (District of Columbia), began leading the rapid implementation process for E2i and providing training and technical assistance to support implementation through collaborative learning and implementation toolkits.

Search for Interventions (August–September 2017)

To find a large, diverse pool of interventions, E2i staff members searched for intervention strategies with various levels of demonstrated effectiveness, including rigorous evidence-based studies and promising evidence-informed interventions that found significant positive intervention effects as well as emerging strategies from community-based HIV organizations that produced unpublished yet compelling data on HIV-related health outcomes.

Initially, we systematically searched PubMed, EbscoHost, and Google Scholar for peer-reviewed articles on intervention findings relevant to the 4 focus areas. The paucity of intervention strategies in the literature led us to expand the search to interventions that were not yet studied among people with HIV but showed promise for adaptation. We also searched for best-practice tools and strategies compiled on websites hosted by academic research centers, nonprofit groups, and federal agencies, such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, AIMS Center of the University of Washington, Center for Engaging Black MSM Across the Care Continuum, HRSA HAB, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Finally, we solicited recommendations from a national pool of consulting experts in the field of HIV and reached out to intervention developers to access unpublished data and intervention manuals. Ultimately, our search found 86 intervention strategies across the 4 focus areas.

Assessment of Interventions (September–October 2017)

After eliminating interventions with implementation costs not allowable under Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program funding, 25 E2i staff members developed criteria for selecting interventions that balanced 3 domains: (1) the quality and strength of the available evidence on effectiveness (eg, study design, strength of evidence); (2) the intervention’s implementation feasibility, cultural and contextual appropriateness, appeal, and relevance for the priority population and Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program–funded organizational staff members; and (3) the quality of available information (eg, intervention manuals, accessible trainers and developers) that would enable implementation of the intervention strategy in new settings. Based on these criteria, we selected 44 interventions for further consideration.

We next developed an automated quantitative scoring rubric based on the criteria. The rubric consisted of dichotomous (0 or 1 point) and Likert scale (0‐3 points) response choices that totaled to 100 points. The rubric also included open-ended questions for commenting on the strengths and weaknesses of each intervention strategy.

We recruited 26 national experts to review the intervention strategies using the scoring rubric. The group of reviewers consisted of medical practitioners, psychologists, Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program direct service providers, clinical researchers, social epidemiologists, community organization leaders, and HIV advocates with lived experience in each focus area. Many of these experts had previously collaborated with E2i’s core leadership on other projects, and several experts were identified during the literature search as specialists in the field of HIV interventions.

Based on the experts’ reviews, E2i staff members tallied a mean score for each intervention strategy and applied thematic qualitative methods to analyze major strengths and weaknesses. 26 Because a common and expected challenge in scoring evidence-informed interventions was the limited empirical evidence available, we gave qualitative responses, feasibility, and cultural appropriateness substantial consideration in the final rankings.

Selection of Interventions (November 2017)

E2i conducted a meeting with the experts, who were divided into workgroups, to discuss the 8 top-ranked intervention strategies in each focus area. Experts considered not just the merits of each strategy but also diversity in delivery methods, personnel types, and technologies used. In addition, experts wanted to ensure that the intervention strategies in each focus area collectively addressed outcomes along the entire HIV care continuum and promoted change at the individual, interpersonal, and systems levels. Ultimately, 16 intervention strategies were selected (4 per focus area) through this consensus process.

Competitive Request for Applicants (December 2017–January 2018)

In December 2017, we released a competitive request for proposals to recruit Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program–funded organizations ready to implement one of the interventions. Eligibility criteria included having either in-house outpatient ambulatory health services or a preexisting relationship with a provider of this service. To prevent a conflict of interest, organizations that had developed the selected intervention strategies were not eligible to apply. E2i held 2 technical assistance webinars that explained the selection criteria to applicants.

Assessment of Applicants (January–February 2018)

Similar to the intervention selection process, E2i engaged a committee of 49 researchers, medical and behavioral health providers, and community leaders to review and score 114 site applications from organizations across the United States and territories. Scoring criteria considered each site’s demonstrated need, organizational capacity, proposed implementation strategies, current level of meaningful engagement of people with HIV, experience in providing culturally responsive services for the priority population, extent of technical assistance needs, capacity to collect evaluation data, and ability to integrate and sustain the program beyond the funding period.

Selection of Sites (February–March 2018)

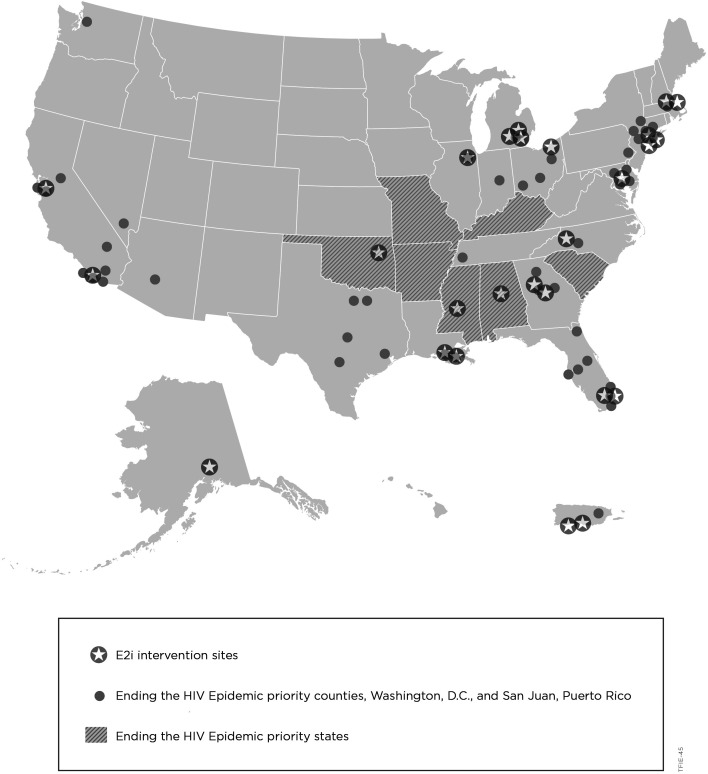

E2i next convened facilitated workgroups to discuss the top-ranked applicants per focus area. In selecting the final group of sites, consideration was also given to ensuring a broad cross-section of Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program–funded provider types and geographic regions with a high prevalence of HIV. In addition, we chose sites that represented a range of cities and rural areas across the United States and that served diverse client populations, particularly Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people. The peer-review consensus process resulted in selecting 26 sites matched to 11 intervention strategies (Table). Each site received a subaward to cover costs associated with implementation, intervention delivery, data collection, and travel for meetings. The E2i sites (selected in 2018) overlap with nearly half of the jurisdictions identified by the federal government in 2019 as counties with >50% of new HIV diagnoses, as well as states with disproportionate prevalence of HIV in rural areas (Figure). 35

Table.

Selected interventions and implementation sites for the Using Evidence-Informed Interventions to Improve Health Outcomes Among People Living With HIV (E2i) initiative, United States, 2017-2021 a

| Intervention name | Care continuum | Intervention description | Site locations (provider types) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus area: transgender women | |||

| Healthy Divas 16 | Linkage to care, retention in care, medication adherence | A manualized intervention that empowers transgender women with HIV to accomplish individualized goals related to gender affirmation, HIV care engagement, and medication adherence. The intervention consists of 6 peer-led individual counseling sessions and 1 group workshop. | Birmingham, Alabama (CBO); Oakland, California (CBO); Newark, New Jersey (AMC) |

| Transgender Women Engagement and Entry To (T.W.E.E.T.) Care Project 28 | Linkage to care, retention in care, medication adherence | Peer leaders recruit newly diagnosed or out-of-care transgender women with HIV into weekly small-group educational sessions to learn about HIV care and related health topics. Peer leaders also help participants engage in HIV care and supportive services. Participants who attend multiple sessions are encouraged to become peer leaders. | Detroit, Michigan (hospital); Ponce, Puerto Rico (HC); New Orleans, Louisiana (HC) |

| Focus area: Black men who have sex with men | |||

| Tailored motivational interviewing (TMI) 29 | Linkage to care, retention in care, medication adherence | People with HIV receive brief motivational interviewing sessions from a peer counselor or other provider to improve retention in care and other key behaviors relevant to self-management. | Macon, Georgia (public health department); Fort Lauderdale, Florida (CBO); Jackson, Mississippi (AMC) |

| Client-Oriented New Patient Navigation to Encourage Connection to Treatment (Project CONNECT) 30 | Linkage to care, retention in care | New clients attend an orientation and receive a biopsychosocial assessment led by a linkage coordinator within 5 days of initial contact with the HIV clinic. The linkage coordinator attends each client’s first primary care visit and helps clients stay engaged in care. | Cleveland, Ohio (CBO) |

| Text Messaging Intervention to Improve Antiretroviral Adherence Among HIV-Positive Youth (TXTXT) 31 | Medication adherence | Daily, automated, individually tailored, 2‐way text message reminders and encouragement to take HIV medication. | Detroit, Michigan (CBO); Brooklyn, New York (AMC) |

| Focus area: integrating behavioral health with primary medical care | |||

| Clinic-based buprenorphine treatment 23 | Retention in care, medication adherence | Buprenorphine treatment is integrated within HIV primary care to treat opioid use disorder; delivered in ambulatory or mobile settings. | Ponce, Puerto Rico (HC); Methuen, Massachusetts (HC) |

| Collaborative care management for behavioral health 24 | Retention in care, medication adherence | A team consisting of an HIV primary care clinician, behavioral health provider, and psychiatric consultant provide patient-centered behavioral health care. | Detroit, Michigan (CBO); Baton Rouge, Louisiana (AMC); Washington, DC (HC); Tulsa, Oklahoma (AMC) |

| Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) 32 | Retention in care, medication adherence | Clients are screened for alcohol and drug use disorders, provided a brief counseling intervention (using motivational interviewing or other techniques), and referred for further evaluation and treatment as needed. | Wilton Manors, Florida (CBO); Newark, New Jersey (CBO) |

| Focus area: identifying and addressing trauma | |||

| Cognitive processing therapy 33 | Retention in care, medication adherence | 12 weekly sessions of cognitive–behavioral therapy adapted for people with posttraumatic stress disorder. Reduces distress related to traumatic experiences by challenging cognitive “stuck points,” developing an adaptive narrative about the trauma, and developing coping skills for the future. | Asheville, North Carolina (HC); Decatur, Georgia (CBO) |

| Trauma-Informed Approach and Coordinated HIV Assistance and Navigation for Growth and Empowerment (TIA/CHANGE) | Retention in care, medication adherence | A systems-level change program that uses trauma-informed methods of care to address barriers to care, including mental health problems, addictions, trauma, low levels of health literacy, and lack of support services. | Anchorage, Alaska (hospital); Chicago, Illinois (CBO) |

| Seeking Safety 34 | Retention in care, medication adherence | A flexible, manualized, present-focused, cognitive–behavioral therapy program designed for individuals or groups to attain safety from trauma and addiction. | Boston, Massachusetts (CBO); La Jolla, California (AMC) |

Abbreviations: AMC, academic medical center; CBO, community-based organization; HC, Health Resources & Services Administration Health Center Program grantee.

aE2i is a 4-year initiative funded by the Health Resources & Services Administration HIV/AIDS Bureau to (1) identify intervention strategies to improve HIV health outcomes for transgender women, Black men who have sex with men, and people affected by trauma and behavioral health disorders; (2) pilot the implementation of these intervention strategies to assess their impact in real-world settings; and (3) disseminate the strategies through multimedia toolkits for national rapid replication. 27

Figure.

Geographic overlap among implementation sites for the Using Evidence-Informed Interventions to Improve Health Outcomes Among People Living With HIV (E2i) initiative (2017-2021) and priority counties and states identified by the federal government for Ending the HIV Epidemic in the United States. 35 E2i is a 4-year initiative funded by the Health Resources & Services Administration HIV/AIDS Bureau to (1) identify intervention strategies to improve HIV health outcomes for transgender women, Black men who have sex with men, and people affected by trauma and behavioral health disorders; (2) pilot the implementation of these intervention strategies to assess their impact in real-world settings; and (3) disseminate the strategies through multimedia toolkits for national rapid replication. 27

Implementation Planning and Tailoring (March–December 2018)

To launch the pilot implementation phase, E2i provided site staff members with technical assistance to plan and tailor the intervention strategies for their local, cultural, and organizational contexts. An important aspect of the customization process was to first identify the core elements, or “active ingredients,” necessary for achieving the expected outcomes of each intervention strategy. Core elements are activities, processes, or behaviors (eg, providing transgender women with 6 group education and counseling sessions on HIV and other relevant health topics) and may also include methods to implement the intervention strategy (eg, training transgender women to deliver sessions to their peers). Although sites could not alter the core elements, we encouraged sites to develop additional implementation and delivery strategies to further tailor the intervention strategies (eg, recruiting transgender women clients through local outreach events).

By December 2018, all 26 E2i sites had launched the implementation of their intervention strategies. Since then, the sites have been sustainably incorporating the intervention strategies into their service delivery while receiving virtual and in-person technical assistance (eg, conference calls, webinars, site visits) from E2i staff members and intervention trainers and engaging in peer-led collaborative learning (eg, learning sessions).

Implementation Tools Development (May 2018–June 2021)

The ultimate goal of the initiative is to enable all Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program–funded organizations and other HIV service delivery sites to rapidly replicate the intervention strategies with minimal additional funding or technical assistance. To accomplish this goal, E2i is designing multimedia implementation toolkits with succinct, user-friendly information. The toolkits describe how to implement core elements of the intervention strategies. E2i engaged with the original developers and with expert trainers of the intervention strategies to design the first iteration of implementation toolkits that were piloted by the sites beginning in August 2018. Throughout the E2i project, site staff members and developers collaborated with E2i staff members to expand the toolkits by adding demonstration and narrative videos, interactive learning modules, implementation checklists, and case studies. E2i is also iteratively refining the toolkits to reflect lessons learned in the process of adaptation and implementation at the sites. HRSA HAB will centrally disseminate toolkits and other resources through TargetHIV.gov in November 2021.

Evaluation Plan

E2i’s implementation science evaluation plan, as led by the University of California San Francisco’s Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, applies the Proctor Model, 36 a framework that allows for concurrently evaluating intervention strategies, implementation strategies, and 3 types of outcomes: implementation (eg, feasibility, acceptability, sustainability, cost), service (eg, equity, timeliness), and client (eg, retention, viral load). 27 E2i is also monitoring site fidelity to the core components of each intervention to prevent “program drift” and “voltage drop” in effectiveness that often occurs when translating research into practice. 37 In the last year of the initiative (August 2020–July 2021), E2i is finalizing the evaluation and incorporating findings into the implementation toolkits.

Public Health Implications

HRSA’s rapid implementation approach, as applied to the E2i initiative, offers important lessons for public health agencies seeking to scale up the replication of effective interventions to end the HIV epidemic. First, the search for promising interventions must extend beyond the peer-reviewed literature. Because of a lack of funding for evaluation and publication, lengthy peer-review processes, and a traditional research emphasis on HIV prevention and risk behavior outcomes over care continuum outcomes, it can be challenging to identify an adequate breadth of interventions in peer-reviewed journals alone. Word count limits in academic journals may limit sufficient detail about interventions, making replication impossible. Therefore, we recommend also searching website repositories for practice tools and white papers, contacting interventionists to access unpublished data and supporting materials, and considering adaptation of interventions originally developed for HIV prevention and for non-HIV populations.

Second, when choosing interventions to adapt, cultural and contextual factors such as implementation feasibility and acceptability for the priority population(s) may deserve equal or greater weight than methodological rigor and strength of evidence. An intervention strategy shown to have efficacy in a randomized control trial will have no effect in an HIV service organization if the intervention is not perceived as meaningful to clients or staff members. Although our scoring rubric placed more weight toward the quality of study design and evidence, our reviewers corrected this imbalance by qualitatively placing equal weight on acceptability and feasibility. Moreover, although our review process initially identified 16 intervention strategies, we moved forward with only 11 interventions matched to organizations that submitted the most viable applications for implementing those interventions.

Finally, to better understand the minimum resources needed to rapidly replicate interventions at diverse HIV direct service organizations, E2i judiciously allotted training and technical assistance for the E2i sites. This novel paradigm intends to naturally simulate the future replication experience at other HIV direct service organizations that will attempt to adopt these interventions using E2i multimedia implementation toolkits, without access to subawards or robust training and technical assistance by national experts.

Although no single initiative can end the HIV epidemic, the goals of E2i strongly align with the goals of the HIV National Strategic Plan 38 and Ending the HIV Epidemic in the United States. 35 By promoting rapid implementation of effective intervention strategies that engage the most affected populations in HIV care and treatment, E2i has the potential to extend and improve the lives of people with HIV and substantially reduce HIV incidence.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following people for their efforts in support of the E2i initiative: the E2i Coordinating Center for Technical Assistance, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health: Richard A. Cancio, MPH; Sarah Mitnick, BA; Tess McKenney, BA; Neeki Parsa, BA; and Reagin Wiklund, BS; AIDS United: Alicia Downes, LMSW; Hannah B. Bryant, MPH; Joseph Stango, BA; Venton Hill-Jones, MS; Marvell Terry; the E2i Evaluation Center, University of California, San Francisco, Center for AIDS Prevention Research: Janet J. Myers, PhD, MPH; Gregory M. Rebchook, PhD; Carol Dawson-Rose, RN, PhD, FAAN; Kimberly A. Koester, PhD; Starley B. Shade, PhD, MPH; Beth Bourdeau, PhD; Mary A. Guzé, MPH; and Andres Maiorana, MA.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: A.K. will receive future royalties as editor of a textbook on transgender and gender diverse health for McGraw-Hill Education.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) (U69HA31067) to The Fenway Institute. No percentage of this project was financed with nongovernmental sources. This information and the content and conclusions of this article are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by, HRSA, HHS, or the US government.

ORCID iD

Hilary Goldhammer, SM https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4382-2296

References

- 1. Samji H., Cescon A., Hogg RS. et al. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One. 2013;8(12): 10.1371/journal.pone.0081355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cohen MS., Chen YQ., McCauley M. et al. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):830-839. 10.1056/NEJMoa1600693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data: United States and 6 dependent areas, 2018. HIV Surveill Rep. 2020;25(2):1-104. Accessed July 12, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-25-2.pdf

- 4. Kapadia F., Landers S. Ending the HIV epidemic: getting to zero and staying at zero. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(1):15-16. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoffmann TC., Erueti C., Glasziou PP. Poor description of non-pharmacological interventions: analysis of consecutive sample of randomised trials. BMJ. 2013;347: 10.1136/bmj.f3755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Curran GM., Bauer M., Mittman B., Pyne JM., Stetler C. Effectiveness–implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217-226. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Psihopaidas D., Cohen SM., West T. et al. Implementation science and the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program’s work towards ending the HIV epidemic in the United States. PLoS Med. 2020;17(11): 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Health Resources and Services Administration . Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program annual client-level data report. 2018. Accessed June 12, 2020. http://hab.hrsa.gov/data/data-reports

- 9. Becasen JS., Denard CL., Mullins MM., Higa DH., Sipe TA. Estimating the prevalence of HIV and sexual behaviors among the US transgender population: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2006-2017. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(1):e1-e8. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018. HIV Surveill Rep. 2020;31:1-119. Accessed June 12, 2020. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html

- 11. Zanoni BC., Mayer KH. The adolescent and young adult HIV cascade of care in the United States: exaggerated health disparities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(3):128-135. 10.1089/apc.2013.0345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. James SE., Herman JL., Rankin S., Keisling M., Mottet L., Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. Accessed June 10, 2020. http://www.ustranssurvey.org/reports

- 13. Menza TW., Choi SK., LeGrand S., Muessig K., Hightow-Weidman L. Correlates of self-reported viral suppression among HIV-positive, young, Black men who have sex with men participating in a randomized controlled trial of an internet-based HIV prevention intervention. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(2):118-126. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mizuno Y., Beer L., Huang P., Frazier EL. Factors associated with antiretroviral therapy adherence among transgender women receiving HIV medical care in the United States. LGBT Health. 2017;4(3):181-187. 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baguso GN., Turner CM., Santos GM. et al. Successes and final challenges along the HIV care continuum with transwomen in San Francisco. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(4): 10.1002/jia2.25270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sevelius J., Chakravarty D., Neilands TB. et al. Evidence for the model of gender affirmation: the role of gender affirmation and healthcare empowerment in viral suppression among transgender women of color living with HIV. 2021;25(suppl 1):64-71.doi:1007/s10461-019-02544-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holtzman CW., Brady KA., Yehia BR. Retention in care and medication adherence: current challenges to antiretroviral therapy success. Drugs. 2015;75(5):445-454. 10.1007/s40265-015-0373-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nightingale VR., Sher TG., Mattson M., Thilges S., Hansen NB. The effects of traumatic stressors and HIV-related trauma symptoms on health and health related quality of life. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1870-1878. 10.1007/s10461-011-9980-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brezing C., Ferrara M., Freudenreich O. The syndemic illness of HIV and trauma: implications for a trauma-informed model of care. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(2):107-118. 10.1016/j.psym.2014.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nolan S., Walley AY., Heeren TC. et al. HIV-infected individuals who use alcohol and other drugs, and virologic suppression. AIDS Care. 2017;29(9):1129-1136. 10.1080/09540121.2017.1327646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Durvasula R., Miller TR. Substance abuse treatment in persons with HIV/AIDS: challenges in managing triple diagnosis. Behav Med. 2014;40(2):43-52. 10.1080/08964289.2013.866540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nanni MG., Caruso R., Mitchell AJ., Meggiolaro E., Grassi L. Depression in HIV infected patients: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(1): 10.1007/s11920-014-0530-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Altice FL., Bruce RD., Lucas GM. et al. HIV treatment outcomes among HIV-infected, opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone treatment within HIV clinical care settings: results from a multisite study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(suppl 1):S22-S32. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318209751e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Archer J., Bower P., Gilbody S. et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525. 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Health Resources and Services Administration, HIV/AIDS Bureau . Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program services: eligible individuals & allowable uses of funds. Policy Clarification Notice (PCN) #16-02. Revised October 2018. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://hab.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hab/program-grants-management/ServiceCategoryPCN_16-02Final.pdf

- 26. Guest G., MacQueen KM., Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bourdeau B., Shade S., Koester K. et al. Implementation science protocol: evaluating evidence-informed interventions to improve care for people with HIV seen in Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program settings [published online January 11, 2021]. AIDS Care. 10.1080/09540121.2020.1861585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hirshfield S., Contreras J., Luebe RQ. et al. Engagement in HIV care among New York City transgender women of color: findings from the peer-led, TWEET intervention, a SPNS Trans Women of Color Initiative. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(suppl 1):20-30. 10.1007/s10461-019-02667-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Naar-King S., Outlaw A., Green-Jones M., Wright K., Parsons JT. Motivational interviewing by peer outreach workers: a pilot randomized clinical trial to retain adolescents and young adults in HIV care. AIDS Care. 2009;21(7):868-873. 10.1080/09540120802612824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mugavero MJ. Elements of the HIV care continuum: improving engagement and retention in care. Top Antivir Med. 2016;24(3):115-119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garofalo R., Kuhns LM., Hotton A., Johnson A., Muldoon A., Rice D. A randomized controlled trial of personalized text message reminders to promote medication adherence among HIV-positive adolescents and young adults. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(5):1049-1059. 10.1007/s10461-015-1192-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Babor TF., McRee BG., Kassebaum PA., Grimaldi PL., Ahmed K., Bray J. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT): toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Subst Abus. 2007;28(3):7-30. 10.1300/J465v28n03_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Resick PA., Wachen JS., Mintz J. et al. A randomized clinical trial of group cognitive processing therapy compared with group present–centered therapy for PTSD among active duty military personnel. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(6):1058-1068. 10.1037/ccp0000016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Najavits LM., Weiss RD., Shaw SR., Muenz LR. “Seeking safety”: outcome of a new cognitive–behavioral psychotherapy for women with posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence. J Trauma Stress. 1998;11(3):437-456. 10.1023/A:1024496427434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy, US Department of Health and Human Services . What is ending the HIV epidemic in the U.S.? Updated March 2021. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview

- 36. Proctor EK., Powell BJ., McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chambers DA., Glasgow RE., Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8:117. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy, US Department of Health and Human Services . HIV National Strategic Plan: a roadmap to end the epidemic. Updated January 2021. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/hiv-national-strategic-plan/hiv-plan-2021-2025