Abstract

Background/Aims

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) is the medical manifestation of alcohol use disorder, a prevalent psychiatric condition. Acute and chronic manifestations of ALD have risen in recent years especially in young people and ALD is now a leading indication of liver transplantation (LT) worldwide. Such alarming trends raise urgent and unanswered questions about how medical and psychiatric care can be sustainably integrated to better manage ALD patients before and after LT.

Methods

Critical evaluation of the interprofessional implications of broad and multifaceted ALD pathophysiology, general principles of and barriers to interprofessional teamwork and care integration, and measures that clinicians and institutions can implement for improved and integrated ALD care.

Results

The breadth of ALD pathophysiology, and its numerous medical and psychiatric comorbidities, ensures that no single medical or psychiatric discipline is adequately trained and equipped to manage the disease alone.

Conclusions

Early models of feasible ALD care integration have emerged in recent years but much more work is needed to develop and study them. The future of ALD care is an integrated approach led jointly by interprofessional medical and psychiatric clinicians.

Keywords: integrated, interprofessional, alcohol, multidisciplinary, liver

Abbreviations: ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; AUD, alcohol use disorder; LT, liver transplantation; QI, quality improvement; SUD, substance use disorder

Alcohol remains a primary etiology of liver disease worldwide1 and a major source of global disease burden.2 Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) commonly presents in more advanced stages3 and its morbidity and mortality are increasing including among young people.4 At the core of ALD is alcohol use disorder (AUD), a prevalent, chronic, stigmatized, and deadly psychiatric condition which is often severe among ALD patients and comorbid with other psychiatric disorders of mood, anxiety, and personality.5, 6, 7, 8 This broad and serious medical-psychiatric pathophysiology ensures that no single discipline is adequately trained or equipped to manage ALD. This raises important questions about how different models of integrated care can be developed, implemented, and maintained.

Other authors recognize and call for multidisciplinary care to address such a breadth of serious and chronic ALD problems.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 There is a newer and growing literature about the actual implementation and maintenance of integrated ALD care before and after liver transplantation (LT) as well as the pitfalls that can disrupt the work.7,14,15 While integrated ALD care has obvious application in cirrhosis and LT where preventing further alcohol-related injury is paramount, it is also relevant and desirable in earlier and less severe disease stages where patients’ course toward decompensation and transplant may be delayed or avoided altogether. Care integration is also indicated for at-risk groups, vulnerable populations, and ALD patients with disadvantaged LT access.

This article seeks not only to recapitulate key integrated care principles, preparations, processes, and pitfalls but also to depict in clear and practical fashion the discrete aspects of ALD that require an integrated approach thus equipping the reader with actionable insights and tools to begin their own ALD integration process.

Principles of care integration

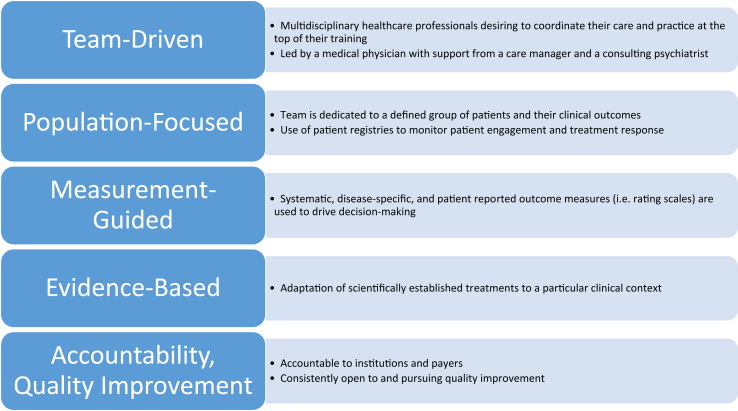

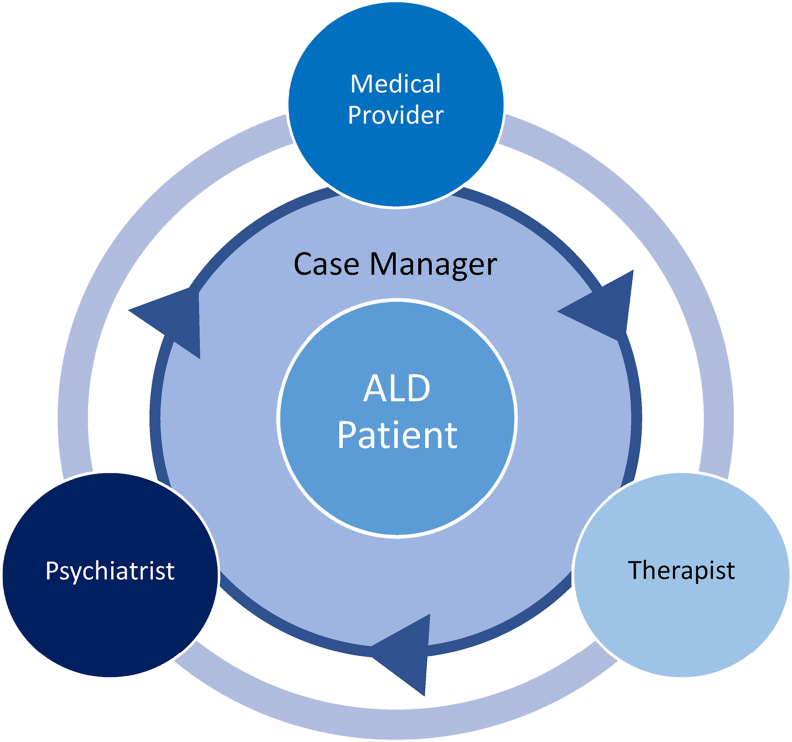

Blending the expertise of clinicians from different disciplines is an established idea. The integration of mental health services into general medical care, so-called collaborative care, is a model that has been well studied in its feasibility and effectiveness.16,17 Collaborative care is governed by several key principles: team-driven, population-focused, measurement-guided, evidence-based, and accountability and quality improvement (Figure 1). These same principles apply to integrating psychiatric and addiction services into liver disease management. These ideas also appear in a 2016 joint report from the American Psychiatric Association and the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry (formerly Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine) regarding the dissemination of integrated care within adult primary care settings.18 This report cites studies examining the relative contributions of different roles on a collaborative team (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Essential elements of collaborative care (adapted from Vanderlip et al).18

Figure 2.

Collaborative care team model on which integrated ALD care models can be based.

Interprofessional implications of ALD pathophysiology

Articles have characterized medical and psychiatric facets of ALD pathophysiology;2,9 it is clear ALD has far-reaching effects on patients and families and places unique demands on care teams and clinicians. Less has been written about the numerous interprofessional implications of ALD (Table 1) or the complicated logistics of integrated and interprofessional treatment models required to address such breadth and complexity.

Table 1.

Interprofessional Implications of ALD Pathophysiology Necessitating Integrated Care.

| Clinical Domain | Description and Context | Interprofessional Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Acute alcohol-related hepatitis |

|

|

| Gastrointestinal bleeding |

|

|

| Hepatic encephalopathy |

|

|

| Visible Cirrhosis Stigmata (Ascites, Jaundice, Spider Angiomas) |

|

|

| Neuropathy |

|

|

| Overeating, obesity, and eating disorders |

|

|

| Polypharmacy |

|

|

| Alcohol withdrawal and AUD relapses |

|

|

| Comorbid non-alcohol SUD |

|

|

| Medical and recreational marijuana |

|

|

| Prescription benzodiazepines and opioids |

|

|

| Insomnia |

|

|

| Suicidal ideation |

|

|

| Anxiety and mood disorders |

|

|

| Physical, sexual, and emotional trauma |

|

|

| Personality disorders |

|

|

| Patient deception, defensiveness, ambivalence, denial, and poor insight |

|

|

| Low social support |

|

|

| Stigma and terminology |

|

|

AA, alcoholics anonymous; AAH, acute alcohol-associated hepatitis; ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; AMS, altered mental status; AUD, alcohol use disorder; BZD, benzodiazepines; CBD, cannabidiol; CBTi, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia; DBT, dialectical behavioral therapy; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; LDLT, living donor liver transplantation; MH, mental health; MI, motivational interviewing; MJ, marijuana; MMJ, medical marijuana; OLT, orthotopic liver transplant; PCP, primary care physician; PD, personality disorders; QofL, quality of life; Rx, prescription; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SA, suicide attempts; SI, suicidal ideation; SRI, serotonergic reuptake inhibitor; SUD, substance use disorder; VS, versus.

Psychiatry and addiction clinicians are accustomed to dealing with a wide array of overlapping psychological disorders and symptoms just as hepatology and other medical clinicians regularly manage pathophysiology spanning multiple organ systems. ALD is unique and challenging in the way its clinical treatment requires a holistic view of its interprofessional medical-psychiatric complexity, as a unified core of ALD pathophysiology, rather than parsed or categorized components which can simply be delegated out to diverse specialists. Few would argue that an ideal liver transplant team is one where surgeons, hepatologists, and nurses rarely collaborated. Similarly, a growing number of clinicians in medicine and psychiatry are acknowledging how optimal ALD care models require integration.

Preparations for ALD care integration

Personal Relationships, Personnel Recruitment, and Team Culture

The foundation of any interprofessional collaboration is a strong a priori set of personal and professional relationships shared among clinicians. The importance of constructive interprofessional team dynamics for complex and multifactorial diseases like ALD can be likened to the crucial natures of hand hygiene and surgical sterility for quality bedside care and procedures. Trust, patience, rapport, and good faith catalyze the complicated work of building and maintaining complex and chronic care models for a challenging ALD patient population. Such quality relationships must be an early objective for integrated care and they will not form automatically or easily; they must be deliberately sought out, built, and maintained. ALD clinicians who minimize the importance of such interpersonal factors do so at their own risk due to numerous clinical and logistical challenges (see later) that accompany ALD care integration. Disagreements, adverse clinical outcomes, and miscommunication inevitably occur on any clinical team and may be more pronounced and impactful amidst complex problems with high stakes like ALD. The culture of an integrated ALD team should be one where problems can be discussed openly and respectfully on the way toward a mutually satisfactory resolution.

Given alarming ALD epidemiological trends and widespread clinical needs, integrated ALD care models are likely to rapidly grow and require eventual additional multidisciplinary clinician recruitment. Team expansion is an opportunity to deliberately acquire individuals with the interpersonal capacity to participate in and promote interprofessional work alongside their primary clinical and research skillsets. By cultivating a strong spirit of collaboration and interprofessional curiosity, a unique and powerful collaborative culture can arise which can stand out to patients, rotating learners and trainees, and colleagues seeking consultation. All clinical and/or research achievements and recognition should benefit the careers and salaries of every clinician on the team.

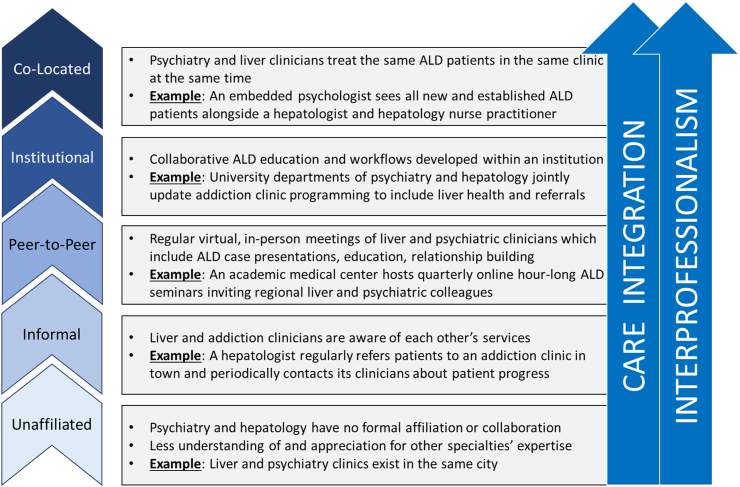

ALD Clinical Model Design and Data Management

Depending on an institution's resources, personnel, and priorities, different models of ALD care may be more feasible than others. Figure 3 depicts ascending tiers of ALD care integration and interprofessionalism which clinicians might consider establishing to incrementally improve their clinical services from their current state. Unaffiliated clinicians may simply seek to contact their medical or psychiatric colleagues as the first step to future integration; inviting a colleague to attend seminar to present a talk is a good early strategy. Clinicians who already share some informal connections (periodically reciprocally referring patients to each other's clinics and providing some clinical updates, for example) may wish to build more substantive relations and opt to begin an open-door quarterly seminar where ALD cases are discussed, interprofessional education offered with continuing medical education credits, open discussions held, and relationships developed.

Figure 3.

Ascending tiers of ALD care integration and interprofessionalism.

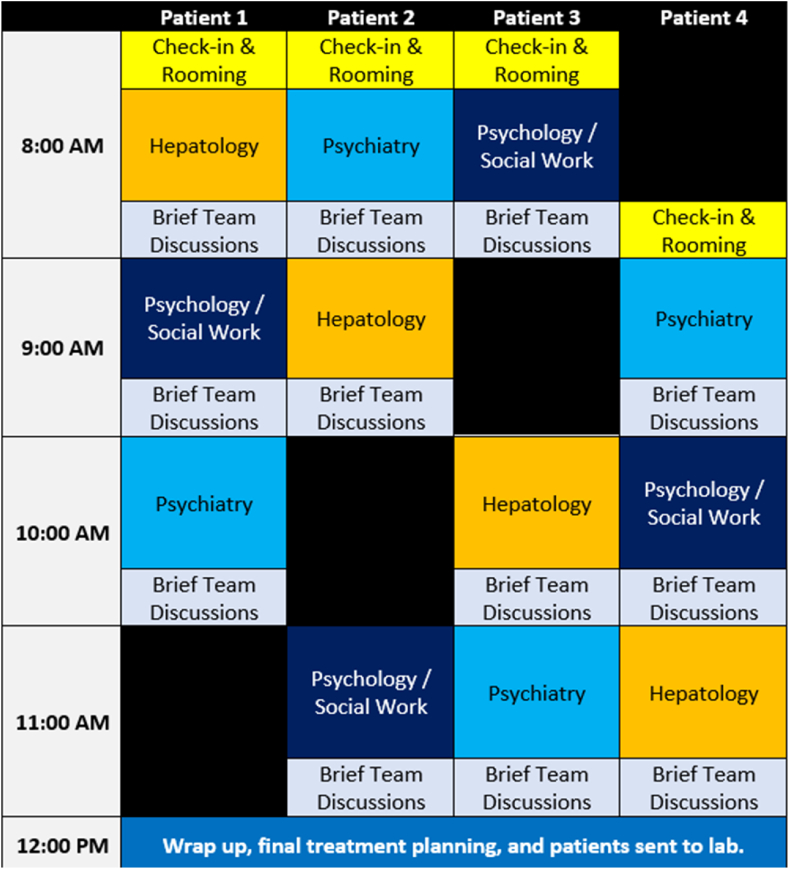

Multidisciplinary clinicians already united within a single institution's mission, facilities, and professional culture may seek to further refine specialty ALD care by developing new specialized connections or workflows among distinct departments and service lines. This could take several forms such as liver clinicians assisting an addiction clinic in developing a curriculum which contains liver topics and hepatology referrals or a psychologist dedicating a half-day per week in her clinic to referrals generated from liver colleagues with whom she regularly corresponds. Arguably, co-location is the epitome of ALD care integration given the high-grade, coordinated specialty care available to ALD patients receiving care from cross-trained clinicians who can easily and rapidly combine, adjust, and personalize comprehensive medical and psychiatric treatment plans. Figure 4 depicts how a morning evaluation clinic might run with each patient remaining in a single examination room while team members rotate. Brief time spent between evaluations allows team members to personalize and fine tune evaluations in interdisciplinary fashion, a capacity unparalleled in other ALD care environments.

Figure 4.

Sample half-day co-located ALD clinic new patient evaluation schedule.

Integrated ALD care generates large amounts of multimodal data including rich qualitative psychosocial data from serial clinical interviews, psychometrics, imaging, vital signs, lab values including toxicology, medical history, and physical examination findings. Attention to data acquisition and management strategies (Table 2) in the design phase will ensure that teams can obtain and review a wide array of data to guide clinical care and facilitate research. A case manager role can be an effective way to coordinate integrated ALD care inside and outside the clinic, collate clinical data, and lead multidisciplinary case review meetings (see later). In our era of open notes where patients and families have access to the medical record, teams must be attentive to their verbiage around sensitive topics to maintain therapeutic alliances and honor the spirit of “do no harm.”

Table 2.

Data Acquisition and Management Strategies for Integrated ALD Care.

| Information Type | Strategies |

|---|---|

| Interview data and past medical and psychiatric histories |

|

| Laboratory values (including toxicology) and imaging |

|

| Psychometrics |

|

| Psychotherapies and mutual support communities |

|

| Patient behavior and adherence |

|

ALD, alcohol-related liver disease.

Institutional Leadership Support and Facilities

Integrated ALD care will require resources from the health system in terms of time, money, facilities, and personnel. The initial group of clinicians seeking to integrate care may consider preparing a written proposal detailing their development plan and then meet face to face with relevant leadership stakeholders (i.e. psychiatry, nursing, transplant, social work, internal medicine) about the next steps. Such meetings are also effective ways to build or strengthen interdepartmental relationships.

It would not be unexpected for an integrated and co-located ALD clinic, for example, to use the physical facilities and clerical resources of a transplant clinic while staffing it with internal medicine physicians, nurses, and advanced practice providers alongside several psychiatry clinicians. Given ongoing severe psychiatric and addiction clinician shortages, salary support flowing from medicine or transplant surgery to psychiatry may be used to secure and protect ALD time allocation. ALD teams may request that physical space be optimized to facilitate integrated care (i.e. aesthetically appropriate interview rooms within a medical clinic, medical equipment, and exam space within an addiction clinic). Such diverse mixtures of resources and personnel will only be possible with ongoing leadership support. Teams will also want to develop workflows around how to refer patients for clinical services that may not be offered within their care venue (i.e. calling ambulances for medical or psychiatric emergencies, referrals to residential rehabilitation or intensive outpatient addiction programming, etc.).

The process of ALD care integration

Initiation

Precise early steps and processes of ALD integration will vary greatly according to team composition; individual and institutional relationships, resources, and timelines; and the tier and model design selected (Figure 3). There are numerous permutations of how ALD care can incrementally become more integrated from its present state. Several examples illustrate potential integration initiation points and trajectories:

-

1.

A hepatologist presently unaffiliated with any psychiatric or addiction clinicians is increasingly concerned about the size of her ALD patient census and her patients' ongoing drinking. She begins asking more drinking-related interview questions, dedicates a section of her clinic note to alcohol, and pilots use of a validated alcohol screening questionnaire (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test). She submits a written proposal to department leadership for an ALD nurse case manager (Figure 2) to monitor her ALD patients' medical and psychiatric care including acting as a liaison among their various clinicians.

-

2.

A hepatologist perceives discontinuities and inefficiencies in the way her ALD patients access AUD treatment services within her institution. To explore integrative remedies, she contacts one of the health system's psychiatrists to informally brainstorm over coffee about problems and possible solutions.

-

3.

A hepatologist working alongside psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers in an established co-located ALD clinic reviews and implements treatment guidelines for AUD management in ALD from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases19 and European Association for the Study of the Liver.20 She also enrolls in an upcoming motivational interviewing training to improve her alcohol-related conversations with patients and families.

Scopes-of-Practice

The massive breadth of ALD pathophysiology and its high clinical stakes demand a diverse care team with proportionally broad scopes of practice which overlap and complement each other. For example, both psychiatrists and hepatologists may prescribe AUD medications. Social workers and psychologists both have psychotherapeutic expertise. To reduce frustrating redundancy and confusion and to optimize team operation, team roles must be clearly delineated agreed upon by all parties.

There are many training backgrounds that can fill the general roles and duties pertinent to ALD care. Table 3 reveals not only how multiple training backgrounds can fill similar roles but also the flexible combinations of professionals that could be integrated into innovative ways in different successful models. As more clinicians collaborate with complimentary clinical skillsets and blended scopes of practice, it is easy to conceptualize how new ALD care models can emerge which are simultaneously comprehensive enough to take on a severe and chronic disease like ALD while being flexible enough to meet individual patient needs. ALD patients trust their medically trained clinicians about alcohol and liver matters21 meaning these clinicians can play an essential role in reducing stigma around mental health and substance use thus facilitating patient interaction with psychiatric colleagues.

Table 3.

Integrated ALD Care Scopes-of-Practice by Training Background.

| Training Background | Clinical Duties |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver Disease Management | Psychotropic Medication Management | AUD and Psychosocial Evaluation | Motivational Interviewing and AUD Treatment Engagement | SUD and Psychiatric Disorder Psychotherapy | Case Management and Outreach | |

| Hepatologist | X | X | X | |||

| Hepatology APP | X | X | X | |||

| Hepatology RN | X | X | X | |||

| Social Worker | X | X | X | X | ||

| Psychologist | X | X | X | |||

| Psychiatric APP | X | X | X | X | ||

| Psychiatrist | X | X | X | X | ||

APP, advanced practice provider; AUD, alcohol use disorder; RN, registered nurse; SUD, substance use disorder.

The process of further expanding a clinician's scope of practice can be daunting particularly for specialists who have already spent years accumulating and refining niche expertise. ALD's vast scope requires its clinicians to “re-generalize” their specialty skillsets to include relevant elements of medical or psychiatric training. It is a sizable request to ask transplant hepatologists and addiction psychiatrists, for example, to pursue additional alcohol and liver training, respectively, for which they will receive no additional pay or licensure designation and amidst all their other personal and professional endeavors. Yet there simply may be no other way to build the interprofessional and integrated teams that ALD care requires.

Interprofessional Education and Staff Training

Integrated ALD clinicians benefit from additional training by colleagues from other disciplines. Such training can be formal didactics provided in local case conferences or during professional society annual meetings. More often, however, interprofessional education is provided clinician-to-clinician while collaborating on clinical care or research projects. This person-to-person information transfer highlights the unique value in strong relationships, close clinical proximity, and clear and frequent communication. Several scenarios show the methods and value of additional team training:

-

1.

After the announcement of an integrated ALD clinic, clerical and call center staff in hepatology have concerns about receiving calls from ALD patients with psychiatric emergencies trying to reach their psychiatric or addiction clinicians. The ALD psychologist and psychiatrist hold a lunch hour meeting reviewing relevant institutional policy and procedure and invite open discussion. They also encourage staff to contact them directly when additional assistance is needed.

-

2.

Hepatology's more frequent use of alcohol biomarkers raises several questions with medical nurses tasked with following up on the tests and their results. Nursing leadership invites psychiatry and social work to present on technical and practical aspects of the use of toxicology in patients with addiction. Time is set aside at the end of the meeting for candid discussion.

-

3.

An addiction clinic recently launched a service line dedicated to ALD patients. Psychiatric clinicians are uncertain how to respond to patients presenting with altered mental status. Time is set aside during a weekly team meeting where hepatology presents on hepatic encephalopathy and medical emergencies. A protocol is established by which medical consultation can be obtained when needed.

Multidisciplinary Team Meetings

An efficiently run and well-attended meeting is the backbone of integrated ALD operations. Two scenarios depict how efficiently-run and well-attended multidisciplinary team meetings can favorably impact ALD care:

-

1.

The case manager of a co-located ALD clinic contacts a patient by phone who missed recent hepatology and psychiatry visits. The psychometric and interview data she gathers during the call indicates the patient is in psychological distress (elevated depression and anxiety questionnaire scores, missing work due to not feeling well). During that week's team meeting, the entire ALD team reviews these data against the backdrop of recent lab trends which include worsening liver function tests and a note from the lab that patient declined toxicology testing. Concerned about a relapse, the team contacts the patient that day for urgent appointments planning to adjust medication and psychotherapy regimens.

-

2.

Academic clinicians from psychiatry, addiction medicine, transplant surgery, and hepatology hold quarterly lunch hour case conferences which discuss ALD/LT patient cases accompanied by interprofessional didactics. Talks are also streamed online to invited regional colleagues and archived for reference. With her new ALD training and acquaintances, a hepatologist asks a psychiatrist about collaborating on inpatient addiction consultation for the university hospital's GI/liver service.

Patient Education Materials

Integrated ALD care should be reflected in the education materials that patients receive. Online or written materials orienting patients to their ALD care should feature psychological and behavioral topics alongside those from hepatology and pharmacy. Supplemental Figure A shows sample pages from an actual patient ALD booklet which moves seamlessly from detailed discussions of liver decompensation, diet, and medications to psychological topics like cycles of habit, coping strategies, and decision-making principles, among others. Mirroring the pathophysiological realities of ALD, patients should ideally perceive little separation between their liver care and their mental health in what they read and experience in clinic.

Connection to the Transplant Center and Health System

One of the goals of improving ALD care integration is to intervene adequately earlier in the disease process so that patients will not require LT. Many patients, however, will still require LT evaluation and integrated ALD clinics can play a large role in maximizing chances of successful transplant in several ways. Three main LT obstacles and delaying factors for ALD patients are (1) adequate AUD treatment, (2) accumulated sober time, and (3) treatment of psychiatric comorbidities. ALD patients who have previously received integrated care are much more likely to have had these matters addressed prior to LT and have treatment plans in place which satisfy LT listing criteria thus easing the downstream burden on the transplant center. Integrated ALD care elicits and documents large amounts of multimodal data including toxicology which, if accessible to the transplant center, expedites transplant clinicians' understanding of ALD patients’ medical and psychiatric pathology enabling them to more adeptly treatment plan and risk stratify. The degree to which ALD clinicians acquire their own relevant transplant knowledge bases and skillsets only further facilitates ALD patient success in transplant.

Integrated ALD clinicians should remain aware of and involved in other addiction needs and initiatives in their health systems. Other institutional initiatives may proffer additional opportunities for ALD care model expansion such as AUD care in less severe liver disease in the primary care setting or in vulnerable populations. Another example would be a new inpatient addiction medicine consultation service benefitting from ALD-specific training which in turn generates numerous referrals for an integrated ALD outpatient clinic.

The need for integrated addiction care is not confined to AUD treatment in hepatology and other medical or psychiatric colleagues may turn to integrated ALD clinicians for ideas for improving the treatment of other challenging medical substance use disorder (SUD) populations (i.e. patients with comorbid endocarditis and severe opioid use disorder). In fact, lessons learned from ALD care integration could be a return on investment presented to the health system and departmental leadership during planning stages.

Quality Improvement, Research, and Future Directions

Integrated ALD care is a growing field within hepatology and will benefit from close attention to quality improvement (QI) and study. Several multidisciplinary outcomes and metrics (Table 4) may be worth tracking as more institutions adopt various types of integrated ALD care models. As described earlier, an open and warm team culture undergirded by strong interpersonal relationships will facilitate QI information becoming rapidly integrated into team interactions and clinical operations toward problem resolution and improvement.

Table 4.

| Psychiatric | Psychometric score improvement (QofL, anxiety, depression, sleep, et cetera) |

| Negative toxicology (alcohol, other drugs, nicotine) and rates of discordance with patient reports | |

| Reduced alcohol consumption per subjective report and quantitative biomarkers (i.e. PEth) | |

| Rates of alcohol treatment engagement, retention, and completion (residential rehabilitation, intensive outpatient, group and/or individual psychotherapy, mutual support group milestones [i.e. AA sobriety coins]) | |

| Reduced alcohol cravings (subjective report or validated questionnaire) | |

| Rates of regained sobriety and alcohol treatment reengagement after relapse | |

| Medical | Improved LFTs (AST, ALT, Tbili, albumin) and MELD scores |

| Reduced healthcare utilization (hospital admissions, ER visits) | |

| Rates of improved symptoms of decompensated cirrhosis and averted LT evaluations | |

| Reduced mortality | |

| Expedited LT timetables (i.e. accelerated time-to-listing) | |

| Improved LT outcomes (lower rates of de-listing, rates of pre- and post-transplant relapse, graft failure, hospital readmission, post-transplant return-to-function) | |

| Other | Patient and family satisfaction scores and feedback for in-person and/or virtual visits |

| Clinical and administrative personnel satisfaction scores and feedback regarding teamwork quality and clinical operations | |

| Satisfaction scores and feedback from intra- and extramural referring clinicians | |

| Cost savings generated from reduced healthcare utilization rates (hospital admissions, ER visits) | |

| Patient access and utilization rates (no-shows, cancellations, intra- and extramural referrals, et cetera) | |

| Reimbursement and revenue generation |

AA, alcoholics anonymous; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ER, emergency room; LFT, liver function tests; LT, liver transplant; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; PEth, phosphatidylethanol; QofL, quality of life; Tbili, total bilirubin.

There are several future directions for clinical development and research regarding integrated ALD care.22 The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about the widespread usage of virtual visits which may play a role in improving integrated ALD care access and adherence. More work is needed to innovate and understand what team professional compositions (i.e. hepatologist + psychiatric nurse practitioner + addiction social worker) and which visit types (in-person, virtual, phone) and frequencies are optimal. Eventual controlled and multicenter studies will be required to properly evaluate novel integrated care models and establish standards of care.

ALD care integration pitfalls

A detailed discussion of potential pitfalls to efforts integrate psychiatric, social, and medical care in end-stage disease and transplant and their possible remedies exist elsewhere.15 Additional ALD-specific integration pitfalls to consider include over-ambitious patient recruitment resulting in care access problems in a medically ill liver population, vague referral criteria resulting in an overly heterogenous population (i.e. primary non-alcohol SUD, mild liver disease not requiring hepatology care, patients unwilling to speak to psychiatric clinicians), or ill-conceived and/or forced integration efforts which supersede actual clinician buy-in and collaborative capacity. Ideally, ALD clinicians are aware of these humanistic and logistical obstacles early in preparation phases, address them in proposals submitted to leadership, and work to minimize or prevent them during integrated care implementation.

ALD care integration exists in some form in many transplant centers but is much less common elsewhere in hepatology. Given the concerning alcohol epidemiological trends and unique aspects of ALD pathophysiology, the field of hepatology is recognizing the benefits of integrating psychiatric and addiction treatment into liver care. Early models of feasible care integration have emerged in recent years but much more work is needed to develop and study them. If the future of ALD care is an integrated approach, it will be jointly led by medical and psychiatric clinicians who seek to provide collaborative and comprehensive care while seeking their own lifelong interprofessional education and training.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Dr. Winder–conception of the article, drafting of the original and revising manuscript; Dr. Fernandez–conception of the article, reviewing and editing the manuscript; Dr. Mellinger–conception of the article, reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Financial support

J. L. M. is supported by an NIAAA K23 AA02633301 Career Development Award, and A. C. F. is supported by an NIAAA K23 AA023869 Career Development Award.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2022.01.010.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Rehm J., Samokhvalov A.V., Shield K.D. Global burden of alcoholic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2013;59:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seitz H.K., Bataller R., Cortez-Pinto H., et al. Alcoholic liver disease. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2018;4:16. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah N.D., Ventura-Cots M., Abraldes J.G., et al. Alcohol-related liver disease is rarely detected at early stages compared with liver diseases of other etiologies worldwide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:2320–2329. e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tapper E.B., Parikh N.D. Mortality due to cirrhosis and liver cancer in the United States, 1999-2016: observational study. BMJ. 2018;362:k2817. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant B.F., Goldstein R.B., Saha T.D., et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions III. JAMA Psychiatr. 2015;72:757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasin D.S., Stinson F.S., Ogburn E., Grant B.F. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2007;64:830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mellinger J.L., Winder G.S., Fernandez A.C., et al. Feasibility and early experience of a novel multidisciplinary alcohol-associated liver disease clinic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021:108396. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singal A.K., Mathurin P. Diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-associated liver disease: a review. JAMA. 2021;326:165–176. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asrani S.K., Trotter J., Lake J., et al. Meeting report: the Dallas consensus conference on liver transplantation for alcohol associated hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2020;26:127–140. doi: 10.1002/lt.25681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Addolorato G., Mirijello A., Barrio P., Gual A. Treatment of alcohol use disorders in patients with alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;65:618–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinrieb R.M., Van Horn D.H., Lynch K.G., Lucey M.R. A randomized, controlled study of treatment for alcohol dependence in patients awaiting liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:539–547. doi: 10.1002/lt.22259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Addolorato G., Mirijello A., Leggio L., et al. Liver transplantation in alcoholic patients: impact of an alcohol addiction unit within a liver transplant center. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:1601–1608. doi: 10.1111/acer.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Im G.Y., Mellinger J.L., Winters A., et al. Provider attitudes and practices for alcohol screening, treatment, and education in patients with liver disease: a survey from the American association for the study of liver diseases alcohol-associated liver disease special interest group. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2407–2416.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winder G.S., Fernandez A.C., Klevering K., Mellinger J.L. Confronting the crisis of comorbid alcohol use disorder and alcohol-related liver disease with a novel multidisciplinary clinic. Psychosomatics. 2020;61:238–253. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2019.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winder G.S., Clifton E.G., Fernandez A.C., Mellinger J.L. Interprofessional teamwork is the foundation of effective psychosocial work in organ transplantation. Gen Hosp Psychiatr. 2021;69:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Archer J., Bower P., Gilbody S., et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katon W.J., Lin E.H., Von Korff M., et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanderlip E., Rundell J., Avery M., et al. American Psychiatric Association, Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine; Washington DC: 2016. Dissemination of Integrated Care within Adult Primary Care Settings: The Collaborative Care Model. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crabb D.W., Im G.Y., Szabo G., Mellinger J.L., Lucey M.R. Diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-associated liver diseases: 2019 practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2020 Jan;71(1):306–333. doi: 10.1002/hep.30866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Association for the Study of the L EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;69:154–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mellinger J.L., Winder G.S., DeJonckheere M., et al. Misconceptions, preferences and barriers to alcohol use disorder treatment in alcohol-related cirrhosis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;91:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singal A.K., Kwo P., Kwong A., et al. Research methodologies to address clinical unmet needs and challenges in alcohol-associated liver disease. Hepatology. 2021 Sep 8 doi: 10.1002/hep.32143. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34496071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathurin P., Moreno C., Samuel D., et al. Early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1790–1800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louvet A., Labreuche J., Artru F., et al. Main drivers of outcome differ between short term and long term in severe alcoholic hepatitis: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2017;66:1464–1473. doi: 10.1002/hep.29240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cotter T.G., Sandıkçı B., Paul S., et al. Liver transplantation for alcoholic hepatitis in the United States: excellent outcomes with profound temporal and geographic variation in frequency. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:1039–1055. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Abajo F.J. Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on platelet function. Drugs and Aging. 2011;28:345–367. doi: 10.2165/11589340-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Starlinger P., Pereyra D., Hackl H., et al. Consequences of perioperative serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment during hepatic surgery. Hepatology. 2021;73:1956–1966. doi: 10.1002/hep.31601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamdan A.-J., Al Enezi A., Anwar A.E., et al. Prevalence of insomnia and sleep patterns among liver cirrhosis patients. J Circadian Rhythms. 2014;12 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chakravorty S., Chaudhary N.S., Brower K.J. Alcohol dependence and its relationship with insomnia and other sleep disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:2271–2282. doi: 10.1111/acer.13217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tapper E.B., Henderson J.B., Parikh N.D., Ioannou G.N., Lok A.S. Incidence of and risk factors for hepatic encephalopathy in a population-based cohort of Americans with cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2019;3:1510–1519. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konerman M.A., Rogers M., Kenney B., et al. Opioid and benzodiazepine prescription among patients with cirrhosis compared to other forms of chronic disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2018-000271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moon A.M., Jiang Y., Rogal S.S., Tapper E.B., Lieber S.R., Barritt Iv A.S. Opioid prescriptions are associated with hepatic encephalopathy in a national cohort of patients with compensated cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Therapeut. 2020;51:652–660. doi: 10.1111/apt.15639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grønbæk L., Watson H., Vilstrup H., Jepsen P. Benzodiazepines and risk for hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Unit Eur Gastroenterol J. 2017;6:407–412. doi: 10.1177/2050640617727179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volk M.L., Tocco R.S., Bazick J., Rakoski M.O., Lok A.S. Hospital readmissions among patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:247–252. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Julian T., Glascow N., Syeed R., Zis P. Alcohol-related peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2019;266:2907–2919. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9123-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mason B.J., Quello S., Shadan F. Gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Expet Opin Invest Drugs. 2018;27:113–124. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2018.1417383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leung J.G., Hall-Flavin D., Nelson S., Schmidt K.A., Schak K.M. The role of Gabapentin in the management of alcohol withdrawal and dependence. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49:897–906. doi: 10.1177/1060028015585849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guglielmo R., Martinotti G., Clerici M., Janiri L. Pregabalin for alcohol dependence: a critical review of the literature. Adv Ther. 2012;29:947–957. doi: 10.1007/s12325-012-0061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyle M., Masson S., Anstee Q.M. The bidirectional impacts of alcohol consumption and the metabolic syndrome: cofactors for progressive fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;68:251–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bulik C.M., Klump K.L., Thornton L., et al. Alcohol use disorder comorbidity in eating disorders: a multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatr. 2004;65 doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0718. 0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mellinger J.L., Shedden K., Winder G.S., et al. Bariatric surgery and the risk of alcohol-related cirrhosis and alcohol misuse. Liver Int. 2021;41:1012–1019. doi: 10.1111/liv.14805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guglielmo R., Martinotti G., Quatrale M., et al. Topiramate in alcohol use disorders: review and update. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:383–395. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moos R.H., Moos B.S. Rates and predictors of relapse after natural and treated remission from alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:212–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiMartini A., Dew M.A., Day N., et al. Trajectories of alcohol consumption following liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:2305–2312. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mellinger J.L., Fernandez A., Shedden K., et al. Gender disparities in alcohol use disorder treatment among privately insured patients with alcohol-associated cirrhosis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43:334–341. doi: 10.1111/acer.13944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rogal S., Youk A., Zhang H., et al. Impact of alcohol use disorder treatment on clinical outcomes among patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2020;71:2080–2092. doi: 10.1002/hep.31042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winder G.S., Shenoy A., Dew M.A., DiMartini A.F. Alcohol and other substance use after liver transplant. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2020:101685. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2020.101685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cotter T.G., Ayoub F., King A.C., Reddy K.G., Charlton M. Practice habits, knowledge, and attitudes of hepatologists to alcohol use disorder medication: sobering gaps and opportunities. Transplant Direct. 2020;6:e603–e. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dew M.A., DiMartini A.F., Steel J., et al. Meta-analysis of risk for relapse to substance use after transplantation of the liver or other solid organs. Liver Transplant. 2008;14:159–172. doi: 10.1002/lt.21278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chuncharunee L., Yamashiki N., Thakkinstian A., Sobhonslidsuk A. Alcohol relapse and its predictors after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:150. doi: 10.1186/s12876-019-1050-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shawcross D.L., O'Grady J.G. The 6-month abstinence rule in liver transplantation. Lancet. 2010;376:216. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60487-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ait-Daoud N., Malcolm R.J., Johnson B.A. An overview of medications for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal and alcohol dependence with an emphasis on the use of older and newer anticonvulsants. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1628–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller W.R., Rollnick S., Ebook L. Guilford Press; New York ; London: 2013. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change; p. 482. 1 online resource (xii) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Donnadieu-Rigole H., Olive L., Nalpas B., et al. Follow-up of alcohol consumption after liver transplantation: interest of an addiction team? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41:165–170. doi: 10.1111/acer.13276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baxter Sr L., Brown D.L., Hurford D.M., et al. Appropriate use of drug testing in clinical addiction medicine. J Addiction Med. 2017;11:1–56. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Webzell I., Ball D., Bell J., et al. Substance use by liver transplant candidates: an anonymous urinalysis study. Liver Transplant. 2011;17:1200–1204. doi: 10.1002/lt.22370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dimartini A., Dew M.A., Javed L., Fitzgerald M.G., Jain A., Day N. Pretransplant psychiatric and medical comorbidity of alcoholic liver disease patients who received liver transplant. Psychosomatics. 2004;45:517–523. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.6.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Likhitsup A., Hassan A., Mellinger J., et al. Impact of a prohibitive versus restrictive tobacco policy on liver transplant candidate outcomes. Liver Transplant. 2019;25:1165–1176. doi: 10.1002/lt.25497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Likhitsup A., Saeed N., Winder G.S., Hassan A., Sonnenday C.J., Fontana R.J. Marijuana use among adult liver transplant candidates and recipients. Clin Transplant. 2021 doi: 10.1111/ctr.14312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu J., Chen P.-Y., Frankel M., Selby R.R., Fong T.-L. Contemporary policies regarding alcohol and marijuana use among liver transplant programs in the United States. Transplantation. 2018;102:433–439. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan K., Forman L. Cannabinoid use among liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2021 Nov;27(11):1623–1632. doi: 10.1002/lt.26103. Epub 2021 Jul 20. PMID: 34018308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peng J.K., Hepgul N., Higginson I.J., Gao W. Symptom prevalence and quality of life of patients with end-stage liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat Med. 2019;33:24–36. doi: 10.1177/0269216318807051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bruyneel M., Sersté T. Sleep disturbances in patients with liver cirrhosis: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018;10:369. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S186665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bagge C.L., Littlefield A.K., Conner K.R., Schumacher J.A., Lee H.-J. Near-term predictors of the intensity of suicidal ideation: an examination of the 24 h prior to a recent suicide attempt. J Affect Disord. 2014;165:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaplan M.S., McFarland B.H., Huguet N., et al. Acute alcohol intoxication and suicide: a gender-stratified analysis of the national violent death reporting system. Inj Prev. 2013;19:38–43. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dew M.A., Rosenberger E.M., Myaskovsky L., et al. Depression and anxiety as risk factors for morbidity and mortality after organ transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation. 2015;100:988–1003. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blanco C., Xu Y., Brady K., et al. Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder with alcohol dependence among US adults: results from national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:630–638. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Debell F., Fear N.T., Head M., et al. A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:1401–1425. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ruggiero K.J., Smith D.W., Hanson R.F., et al. Is disclosure of childhood rape associated with mental health outcome? Results from the National Women's Study. Child Maltreat. 2004;9:62–77. doi: 10.1177/1077559503260309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith D.W., Letourneau E.J., Saunders B.E., Kilpatrick D.G., Resnick H.S., Best C.L. Delay in disclosure of childhood rape: results from a national survey. Child Abuse Neglect. 2000;24:273–287. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Campbell R., Ahrens C.E., Sefl T., Wasco S.M., Barnes H.E. Social reactions to rape victims: healing and hurtful effects on psychological and physical health outcomes. Violence Vict. 2001;16:287–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Helle A.C., Watts A.L., Trull T.J., Sher K.J. Alcohol use disorder and antisocial and borderline personality disorders. Alcohol Res. 2019;40 doi: 10.35946/arcr.v40.1.05. arcr.v40.1.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Noll L.K., Lewis J., Zalewski M., et al. Initiating a DBT consultation team: conceptual and practical considerations for training clinics. Train Educ Prof Psychol. 2020;14:167. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sansone R.A., Bohinc R.J., Wiederman M.W. Borderline personality symptomatology and compliance with general health care among internal medicine outpatients. Int J Psychiatr Clin Pract. 2015;19:132–136. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2014.988269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laederach-Hofmann K., Bunzel B. Noncompliance in organ transplant recipients: a literature review. Gen Hosp Psychiatr. 2000;22:412–424. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bholah H., Bate J., Rothwell K., Aldersley M. Random blood alcohol level testing detects concealed alcohol ingestion in patients with alcoholic liver disease awaiting liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2013;19:782–783. doi: 10.1002/lt.23664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee S.B., Chung S., Seo J.S., Jung W.M., Park I.H. Socioeconomic resources and quality of life in alcohol use disorder patients: the mediating effects of social support and depression. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Pol. 2020;15:13. doi: 10.1186/s13011-020-00258-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dobkin P.L., Civita M.D., Paraherakis A., Gill K. The role of functional social support in treatment retention and outcomes among outpatient adult substance abusers. Addiction. 2002;97:347–356. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ladin K., Daniels A., Osani M., Bannuru R.R. Is social support associated with post-transplant medication adherence and outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplant Rev. 2018;32:16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Neuberger J. Public and professional attitudes to transplanting alcoholic patients. Liver Transplant. 2007;13 doi: 10.1002/lt.21337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stroh G., Rosell T., Dong F., Forster J. Early liver transplantation for patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis: public views and the effects on organ donation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:1598–1604. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.