Abstract

Women and gender-diverse individuals have faced disproportionate socioeconomic burden during COVID-19. There have been reports of greater negative mental health changes compared to men based on cross-sectional research that has not accounted for pre-COVID-19 differences. We compared mental health changes from pre-COVID-19 to during COVID-19 by sex or gender. MEDLINE (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), EMBASE (Ovid), Web of Science Core Collection: Citation Indexes, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang, medRxiv (preprints), and Open Science Framework Preprints (preprint server aggregator) were searched to August 30, 2021. Eligible studies included mental health symptom change data by sex or gender. 12 studies (10 unique cohorts) were included, all of which reported dichotomized sex or gender data. 9 cohorts reported results from March to June 2020, and 2 of these also reported on September or November to December 2020. One cohort included data pre-November 2020 data but did not provide dates. Continuous symptom change differences were not statistically significant for depression (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.12, 95% CI -0.09–0.33; 4 studies, 4,475 participants; I2 = 69.0%) and stress (SMD = − 0.10, 95% CI -0.21–0.01; 4 studies, 1,533 participants; I2 = 0.0%), but anxiety (SMD = 0.15, 95% CI 0.07–0.22; 4 studies, 4,344 participants; I2 = 3.0%) and general mental health (SMD = 0.15, 95% CI 0.12–0.18; 3 studies, 15,692 participants; I2 = 0.0%) worsened more among females/women than males/men. There were no significant differences in changes in proportions above cut-offs: anxiety (difference = − 0.05, 95% CI − 0.20–0.11; 1 study, 217 participants), depression (difference = 0.12, 95% CI -0.03–0.28; 1 study, 217 participants), general mental health (difference = − 0.03, 95% CI − 0.09–0.04; 3 studies, 18,985 participants; I2 = 94.0%), stress (difference = 0.04, 95% CI − 0.10–0.17; 1 study, 217 participants). Mental health outcomes did not differ or were worse by small amounts among women than men during early COVID-19.

Subject terms: Psychology, Health policy, Diseases, Psychiatric disorders

Introduction

In just over two years, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused over 6 million deaths and disrupted social and economic activities across the globe1,2. There has been great concern about population-wide mental health ramifications. Evidence from syntheses of longitudinal studies that have compared pre-COVID-19 symptoms to symptoms among the same study sample during the pandemic, however, has suggested that changes, if present, have been, surprisingly, generally small (e.g., standardized mean difference pre-COVID-19 to during COVID-19 = 0.10 to 0.20)3–5.

Small aggregate differences, however, may not reflect important differences in vulnerable populations. By sex, males infected with COVID-19 are at greater risk of intensive care admission and death than females6,7, but, by gender, socioeconomic burden has disproportionately impacted women8–15. Economically, most single parents are women, and women earn less, are more likely to live in poverty, and hold less secure jobs than men, which heightens vulnerability8,11–14. Women are overrepresented in health care jobs, which involves infection risk8–13 and provide most childcare and family elder care8,11–13. Intimate partner violence has increased with the majority directed towards women8,10–13,15. In addition to women, sex and gender minority individuals may face heightened socioeconomic challenges during COVID-1916,17.

Many of the socioeconomic implications of the pandemic that disproportionately affected women are known to be associated with worse mental health, and there is concern that increased burden during COVID-19 on women and gender minorities may have translated into worse mental health outcomes for these groups18–20. Some researchers and prominent news media stories have reported that COVID-19 mental health effects have been greater for women than men21–31. These reports, however, have been cross-sectional studies that evaluated proportions of participants above cut-offs on self-report measures without consideration of pre-COVID-19 differences, even though mental health disorders and symptoms were more common among women prior to the pandemic32–36. No evidence syntheses have directly compared data on symptom changes by sex or gender from pre-COVID-19 to during the pandemic.

Evidence from longitudinal cohorts that compare mental health symptoms pre-COVID-19 to during COVID-19 is needed to determine if there are gender differences. We are conducting a series of living systematic reviews on COVID-19 mental health5,37,38, including mental health changes5. The objective of this study was to compare mental health changes by sex or gender. This study goes beyond analyses presented in our main living systematic review, which reports on symptom levels and changes in many different population groups by conducting direct comparisons in the subset of studies that provide data on mental health changes by sex or gender.

Methods

Our series of living systematic reviews was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020179703) and a protocol was posted to the Open Science Framework prior to initiating searches (https://osf.io/96csg/). The present study is a sub-study of our main mental health changes review5. Results are reported per the PRISMA statement39.

Study eligibility

For our main symptom changes review, studies on any population were included if they compared mental health outcomes assessed between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2019, when China first reported COVID-19 to the World Health Organization40, to outcomes collected January 1, 2020 or later. We only included pre-COVID-19 data collected in the two years prior to COVID-19 to reduce comparisons of COVID-19 results with those collected during different developmental life stages. Compared samples had to include at least 90% of the same participants pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19 or use statistical methods to account for missing follow-up data. Studies with < 100 participants were excluded for feasibility and due to their limited relative value. For the present analysis, studies had to report mental health outcomes separately by sex (assignment based on external genitalia, usually at birth; e.g., female, male, intersex) or gender (socially constructed characteristics of roles and behaviours; e.g., woman, man, trans woman, trans man, non-binary)41.

Search strategy

MEDLINE (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), EMBASE (Ovid), Web of Science Core Collection: Citation Indexes, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang, medRxiv (preprints), and Open Science Framework Preprints (preprint server aggregator) were searched using a strategy designed by an experienced health science librarian. The China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang databases were searched using Chinese terms based on our English-language strategy. The rapid project launch did not allow for formal peer review, but COVID-19 terms were developed in collaboration with other librarians working on the topic. See Supplementary material 1 for search strategies. The initial search was conducted from December 31, 2019 to April 13, 2020 with automated daily updates. We converted to weekly updates on December 28, 2020 to increase processing efficiency.

Selection of eligible studies

Search results were uploaded into DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada). Duplicate references were removed. Then two reviewers independently evaluated titles and abstracts in random order; if either reviewer believed a study was potentially eligible, it underwent full-text review by two independent reviewers. Discrepancies at the full-text level were resolved by consensus, with a third reviewer consulted if necessary. An inclusion and exclusion coding guide was developed, and team members were trained over several sessions. See Supplementary material 2.

Data extraction

For each eligible study, data were extracted in DistillerSR by a single reviewer using a pre-specified form with validation by a second reviewer. Reviewers extracted (1) publication characteristics (e.g., first author, year, journal); (2) population characteristics and demographics, including eligibility criteria, recruitment method, number of participants, assessment timing, age; (3) mental health outcomes which included symptoms of anxiety, symptoms of depression, general mental health, and stress; (4) if studies reported outcomes by sex or gender or used these terms inconsistently (e.g., described using gender but reported results for females and males, which are sex terms); and (5) if sex or gender were treated as binary or categorical.

Adequacy of study methods and reporting was assessed using an adapted version of the Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Prevalence Studies, which assesses appropriateness of the sampling frame for the target population, appropriateness of recruiting methods, sample size, description of setting and participants, participation or response rate, outcome assessment methods, standardization of assessments across participants, appropriateness of statistical analyses, and follow-up42. Each of the 9 items was coded as “yes” for meeting adequacy criteria, "no” for not meeting criteria, or “unclear” if incomplete reporting did not allow a judgment to be made. See Supplementary material 3.

For all data extraction, including adequacy of study methods and reporting, discrepancies were resolved between reviewers with a third reviewer consulted if necessary.

Statistical analyses

For continuous outcomes, separately for each sex or gender group, we extracted a standardized mean difference (SMD) effect size with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for change from pre-COVID-19 to COVID-19. If not provided, we extracted pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 means and standard deviations (SDs) for each group, calculated raw change scores (SD), and calculated SMD for change using Hedges’ g for each group43, as described by Borenstein et al.44. Raw change scores were presented in scale units and direction, whereas SMD change scores were presented as positive when mental health worsened from pre-COVID-19 to COVID-19 and negative when it improved. We then calculated a Hedges’ g difference in change between sex or gender groups with 95% CI. Positive numbers represented greater negative change in females or women compared to males or men.

For studies that reported proportions of participants above a scale cut-off, for pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 proportions, if not provided, we calculated a 95% CI using Agresti and Coull’s approximate method for binomial proportions45. We then extracted or calculated the proportion change in participants above the cut-off, along with 95% CI, for each sex or gender group. Proportion changes were presented as positive when mental health worsened from pre-COVID-19 to COVID-19 and negative when it improved. If 95% CIs were not reported, we generated them using Newcombe’s method for differences between binomial proportions based on paired data46. To do this, which requires the number of cases at both assessments, which is not typically available, we assumed that 50% of pre-COVID-19 cases continued to be cases during COVID-19 and confirmed that results did not differ substantively if we used values from 30 to 70% (all 95% CI end points within 0.02; see Supplementary Table S1). Finally, we calculated a difference of the proportion change between sex or gender groups with 95% CI47. Positive numbers reflected greater negative change in females or women compared to males or men.

Meta-analyses were done to synthesize differences between sex or gender groups in SMD change for continuous outcomes and in proportion change for dichotomous outcomes via restricted maximum-likelihood random-effects meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was assessed with the I2 statistic. Meta-analysis was performed in R (R version 3.6.3, RStudio Version 1.2.5042), using the metacont and metagen functions in the meta package48. Forest plots were generated using the forest function in meta. Positive values indicated more relatively worse changes in mental health for females or women compared to males or men.

Results

Search results and selection of eligible studies

As of August 30, 2021, there were 64,496 unique references identified and screened for potential eligibility, of which 63,534 were excluded after title and abstract review and 741 after full-text review. Of 221 remaining articles, 209 were excluded, leaving 12 included studies that reported data from 10 cohorts. Supplementary Fig. S1 shows the flow of article review and reasons for exclusion.

Characteristics of included studies

Four publications49–52 reported on 2 large, national, probability-based samples from the United Kingdom (N = 10,918 to 15,376)49,50 and the Netherlands (N = 3,983 to 4,064),51,52 and one publication53 reported on a community sample from Spain (N = 102). Two studies54,55 assessed young adults; one reported on a sample of twins from the United Kingdom (N = 3,563 to 3,694 depending on outcome)54 and another on a sample from Switzerland (N = 786)55. One study assessed adolescents from Australia (N = 248)56, and 3 studies57–59 assessed undergraduate students from China (N = 4,085 to 4,341)57, India (N = 217)58, and the United Kingdom (N = 214)59. One study60 assessed patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (N = 316). Four studies assessed anxiety symptoms54,56,58,60, 4 depression symptoms54,56,58,60, 7 (5 cohorts) general mental health49–53,57,59, and 4 stress55,58–60. Table 1 shows study characteristics. All studies compared women and men or females and males; none included other sex or gender groups. Use of sex and gender terms, however, was inconsistent in 5 of 12 included studies50,54,56,58,59 (e.g., described assessing gender but reporting results for “females” and “males”). Results during COVID-19 were assessed between March and June 2020 for 9 cohorts49–51,53–56,58,59. Two cohorts also reported results from September 202050 and November to December 202052. One cohort did not report data collection dates but was identified in a search on November 9, 202057.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies (N = 12).

| First author | Outcome domains | Description of study design and participants | Country | Pre- and post-COVID-19 dates of data collection | N (%) females or women (F/W) and males or men (M/M) | Mean (SD) participant age or age range (%) | Use of sex or gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety symptoms | Depression symptoms | General mental health | Stress | |||||||

| Dong57 | SCL-90-R | First-year undergraduate students from a single university recruited online who completed two assessments (one prior to COVID-19 and one during) | China |

09/2019 pre-11/2020a |

F/W: 3162–3,277 (75.5–77.4) M/M: 923–1064 (22.6–24.5) |

19 (1) | Gender | |||

| Lim60 | PROMIS Anxiety | PROMIS Depression | PSS | Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus from the Georgians Organized Against Lupus cohort who complete annual surveys | United States |

NR/2018–2019 03–04/2020 |

F/W: 295 (93.4) M/M: 21 (6.6) |

47 (13) | Sex | |

| Magson56 | SCAS-C | SMFQ-C | Adolescents aged 13–16 years who complete annual assessments as part of an ongoing longitudinal cohort that began 4 years prior | Australia |

NR/2019 05/2020 |

Girls: 126 (50.8) Boys: 122 (49.2) |

14 (1) | Inconsistent | ||

| Megías-Robles53 | PANAS-NA | Community sample aged 19–67 years who completed two assessments (one prior to COVID-19 and one during) | Spain |

11/2019 04/2020 |

F/W: 67 (65.7) M/M: 35 (34.3) |

30 (13) | Gender | |||

|

Pierce49 Daly50 |

GHQ-12 | National probability-based sample of adults aged ≥ 18 years who are part of the United Kingdom Household Longitudinal Study; an ongoing longitudinal study which has been collecting data continuously since 2009 | United Kingdom | Pre-COVID-19 wavesb |

F/W: 7181c (46.7) M/M: 8195c (53.3) |

18–34 (11.5)d 35–49 (22.4)d 50–64 (34.5)d 65 + (31.6)d |

Gender Inconsistent |

|||

| 04–09/2020 |

F/W: 6380 (58.4) M/M: 4538 (41.6) |

|||||||||

| Rimfeld54 | GAD-7 | SMFQ | Adult twins born between 1994–1996 who, at age 18 months, were enrolled in the Twins Early Development Study; a longitudinal study which has collected over 14 waves of assessment in 20 years of data collection | United Kingdom |

NR/2018 04–05/2020 |

F/W: 2513–2578e (69.8–70.5) M/M: 1050–1116e (29.5–30.2) |

24–26 (100.0) | Inconsistent | ||

| Saraswathi58 | DASS-21 Anxiety | DASS-21 Depression | DASS-21 Stress | Convenience sample of undergraduate university medical students who completed two assessments (one prior to COVID-19 and one during) | India |

12/2019 06/2020 |

F/W: 139 (64.1) M/M: 78 (35.9) |

20 (2) | Inconsistent | |

| Savage59 | WEMWBS | PSS | Undergraduate students from a single university recruited by email invitation and completed three or more assessments as part of the Student Health Study, a longitudinal cohort study | United Kingdom |

10/2019 04/2020 |

F/W: 154 (72.0) M/M: 60 (28.0) |

18–21 (64.5) 22–25 (22.0) 26–35 (7.5) 35 + (6.1) |

Inconsistent | ||

| Shanahan55 | PSS | Young adults who completed 9 assessments since 2004 as part of the Zurich Project on the Social Development from Childhood to Adulthood, a longitudinal cohort study | Switzerland |

NR/2018 04/2020 |

F/W: 378 (48.1) M/M: 408 (51.9) |

22 (0) | Sex | |||

|

van der Velden51 van der Velden52 |

MHI-5 | National probability-based sample of adults aged ≥ 18 years who were enrolled and completed assessments for the Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences since 2007 | The Netherlands |

03/2019 11–12/2019 03/2020 11–12/2020 |

F/W: 2020 (50.7) M/M: 1963 (49.3) F/W: 2062 (50.7) M/M: 2002 (49.3) |

18–34 (24.9)f 35–49 (22.9)f 50–64 (26.1)f 65 + (26.1)f |

Gender Sex |

|||

DASS-21 Anxiety = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale—Anxiety subscale; DASS-21 Depression = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale—Depression subscale; DASS-21 Stress = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale—Stress subscale, GAD-7 Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; GHQ-12 = General Health Questionnaire-12; MHI-5 = Mental Health Index-5; PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule—Negative affect subscale; PROMIS Anxiety = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System—Anxiety subscale; PROMIS Depression = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System—Depression subscale; PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; SCAS-C = Spence Children's Anxiety Scale—Child; SCL-90-R = Symptom Check List-90 Revised; SMFQ = Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; SMFQ-C = Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire—Child Version; WEMWBS = Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale.

aAuthors did not provide dates of data collection. The article was identified in a November 9, 2020 search. bAnalyses compared COVID-19 symptom levels to preceding trends across multiple assessments. cNumber included in fixed effects regression analysis from where the majority of data were extracted. dAge groups reported for Daly48; for Pierce,49 16–24 = 8.8%, 25–34 = 11.2%, 35–44 = 16.0%, 45–54 = 20.1%, 55–69 = 28.9%, 70 + = 15.1%. eNumber of participants differed by outcome. fBased on van der Velden.51.

Adequacy of study methods and reporting

Two studies (1 cohort)51,52 were rated as “yes” for adequacy for all items. Other studies were rated “no” for 1–3 items (plus 0–3 unclear ratings)50,53,55–59 or “no” on none but “unclear” on 2–4 items49,54,60. There were 6 studies53,55–59 rated “no” or “unclear” for appropriate sampling frame (50.0%), 8 “no” or “unclear” for adequate response rate and coverage (66.7%)49,50,53–56,59,60, and 7 “no” or “unclear” for follow-up response rate and management (58.3%)49,50,53,54,56,59,60. See Supplementary Table S2 for results for all studies.

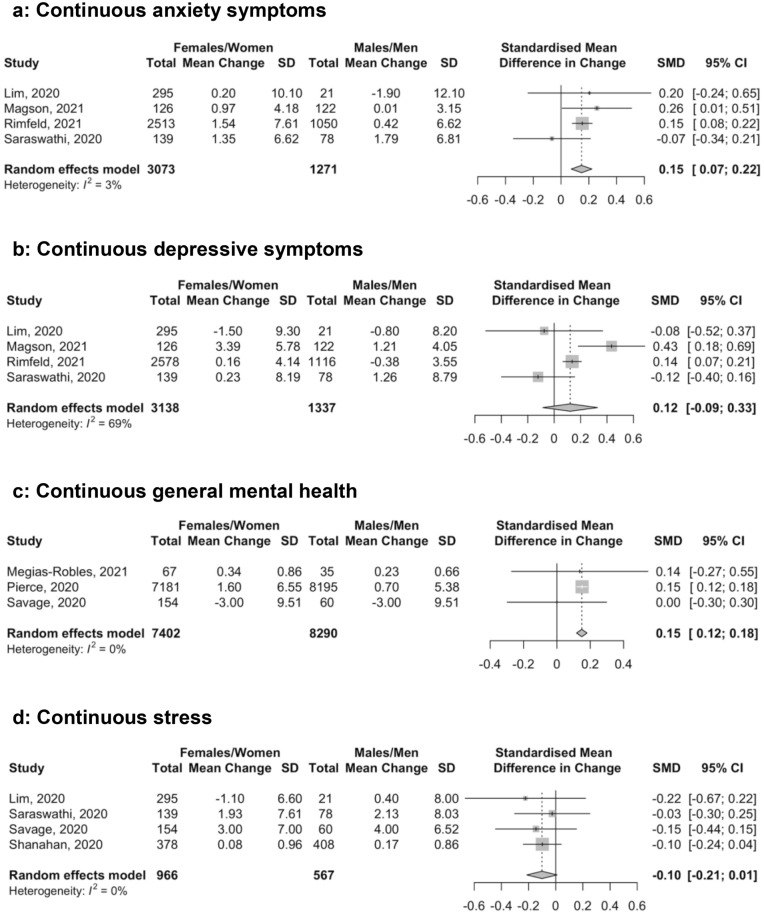

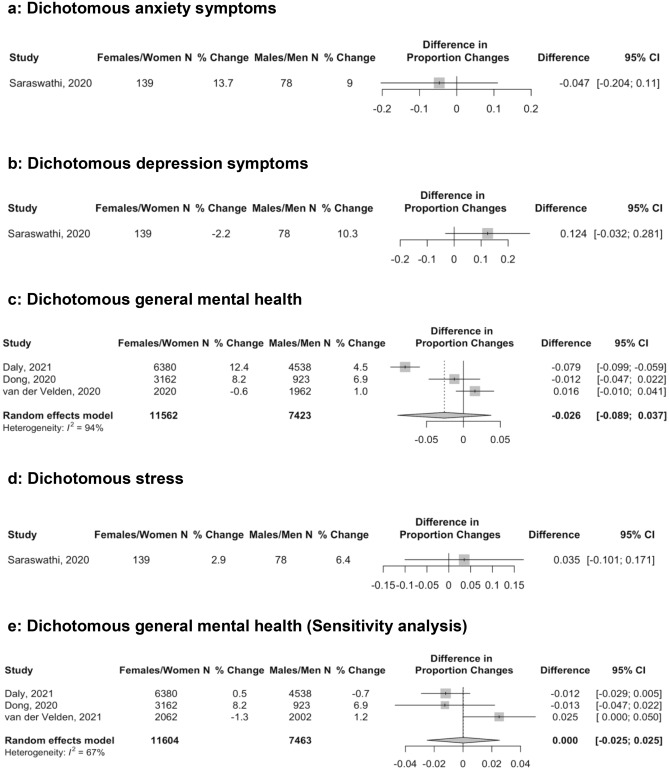

Mental health symptom changes

There was a total of 15 comparisons of continuous score changes and 6 of proportion changes; in 15 out of 21 comparisons, females or women had worse mental health pre-COVID-19. Mental health scores and symptom changes for all outcome domains are reported separately by sex or gender groups in Table 2. Differences in continuous and dichotomous changes by sex or gender are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Estimates of difference in change by sex or gender were close to zero and not statistically significant for anxiety symptoms with dichotomous outcomes (Fig. 2a; proportion change difference = − 0.05, 95% CI − 0.20 to 0.11; N = 1 study58, 217 participants), depression symptoms with continuous (Fig. 1b; SMD change difference = 0.12, 95% CI − 0.09 to 0.33; N = 4 studies54,56,58,60, 4,475 participants; I2 = 69.0%) and dichotomous outcomes (Fig. 2b; proportion change difference = 0.12, 95% CI -0.03 to 0.28; N = 1 study58, 217 participants), general mental health dichotomous outcomes (Fig. 2c [all results from early 2020]; proportion change difference = − 0.03, 95% CI − 0.09 to 0.04; N = 3 studies50,51,57, 18,985 participants; I2 = 94.0%), and stress with continuous (Fig. 1d; SMD change difference = − 0.10, 95% CI − 0.21 to 0.01; N = 4 studies55,58–60, 1,533 participants; I2 = 0.0%) and dichotomous outcomes (Fig. 2d; proportion change difference = 0.04, 95% CI − 0.10 to 0.17; N = 1 study58, 217 participants). Of the 4 studies50–52,57 that reported dichotomous general mental health, 2 studies50,52 also reported outcomes from late 2020; when those results were used, the null finding did not change (Fig. 2e; proportion change difference = 0.00, 95% CI -0.03 to 0.03; N = 3 studies50,52,57 19,067 participants; I2 = 67.0%).

Table 2.

Outcomes from included studies by sex or gender.

| First author | Pre- and post-COVID-19 data collection | Sex or gender | N | Continuous outcome measure | Pre-COVID-19 mean (SD) | Post-COVID-19 mean (SD) | Mean (SD) change | Hedges’ g standardized mean difference (95% CI) | Dichotomous outcome measure | % Pre-COVID-19 (95% CI) | % Post-COVID-19 (95% CI) | % Change (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety symptoms | |||||||||||||

| Lim60 |

NR/2018–2019 03–04/2020 |

Females/Women | 295 | PROMIS Anxiety | 50.20 (11.50) | 50.40 (11.10) | 0.20 (10.10) | 0.02 (− 0.14, 0.18) | –– | –– | –– | –– | |

| Males/Men | 21 | 50.50 (9.90) | 48.60 (11.00) | − 1.90 (12.10) | − 0.17 (− 0.80, 0.45) | ||||||||

| Magson56 |

NR/2019 05/2020 |

Females/Women | 126 | SCAS-C | 5.55 (4.05) | 6.52 (4.31) | 0.97 (4.18) | 0.23 (− 0.02, 0.48) | –– | –– | –– | –– | |

| Males/Men | 122 | 3.63 (3.13) | 3.64 (3.16) | 0.01 (3.15) | 0.00 (− 0.25, 0.26) | ||||||||

| Rimfeld54 |

NR/2018 04–05/2020 |

Females/Women | 2,513 | GAD-7 | 8.15 (7.53) | 9.69 (7.69) | 1.54 (7.61) | 0.20 (0.15, 0.26) | –– | –– | –– | –– | |

| Males/Men | 1,050 | 5.88 (6.66) | 6.30 (6.58) | 0.42 (6.62) | 0.06 (− 0.02, 0.15) | ||||||||

| Saraswathi58 |

12/2019 06/2020 |

Females/Women | 139 | DASS-21 Anxiety | 4.59 (6.29) | 5.94 (6.93) | 1.35 (6.62) | 0.20 (− 0.03, 0.44) | DASS-21 Anxiety > 7 | 18.7 (13.1, 26.0) | 32.4 (25.2, 40.5) | 13.7 (4.4, 22.7) | |

| Males/Men | 78 | 4.62 (6.04) | 6.41 (7.50) | 1.79 (6.81) | 0.26 (− 0.06, 0.58) | 25.6 (17.3, 36.3) | 34.6 (25.0, 45.7) | 9.0 (-4.0, 21.5) | |||||

| Depression symptoms | |||||||||||||

| Lim60 |

NR/2018–2019 03–04/2020 |

Females/Women | 295 | PROMIS Depression | 50.80 (10.70) | 49.30 (9.80) | − 1.50 (9.30) | − 0.15 (− 0.31, 0.02) | –– | –– | –– | –– | |

| Males/Men | 21 | 50.70 (8.60) | 49.90 (9.70) | − 0.80 (8.20) | − 0.08 (− 0.70, 0.54) | ||||||||

| Magson56 |

NR/2019 05/2020 |

Females/Women | 126 | SMFQ-C | 4.77 (5.00) | 8.16 (6.46) | 3.39 (5.78) | 0.58 (0.33, 0.84) | –– | –– | –– | –– | |

| Males/Men | 122 | 2.81 (3.18) | 4.02 (4.76) | 1.21 (4.05) | 0.30 (0.04, 0.55) | ||||||||

| Rimfeld54 |

NR/2018 04–05/2020 |

Females/Women | 2,578 | SMFQ | 4.65 (4.20) | 4.81 (4.07) | 0.16 (4.14) | 0.04 (− 0.02, 0.09) | –– | –– | –– | –– | |

| Males/Men | 1,116 | 3.71 (3.70) | 3.33 (3.40) | − 0.38 (3.55) | − 0.11 (− 0.19, − 0.02) | ||||||||

| Saraswathi58 |

12/2019 06/2020 |

Females/Women | 139 | DASS-21 Depression | 7.71 (7.57) | 7.94 (8.77) | 0.23 (8.19) | 0.03 (− 0.21, 0.26) | DASS-21 Depression > 9 | 36.7 (29.1, 45.0) | 34.5 (27.1, 42.8) | -2.2 (-11.7, 7.4) | |

| Males/Men | 78 | 7.28 (8.40) | 8.54 (9.17) | 1.26 (8.79) | 0.14 (− 0.17, 0.45) | 26.9 (18.3, 37.7) | 37.2 (27.3, 48.3) | 10.3 (-2.9, 22.9) | |||||

| General mental health | |||||||||||||

| Dong57 |

09/2019 NR/2020 |

Females/Women | 3,162–3,277 | –– | –– | –– | –– | –– | SCL-90-R ≥ 160 | 19.7 (18.4, 21.1) | 27.9 (26.4, 29.5) | 8.2 (6.3, 10.0) | |

| Males/Men | 923–1,064 | 14.3 (12.3, 16.5) | 21.2 (18.7, 24.0) | 6.9 (4.0, 9.9) | |||||||||

| Megías-Robles53 |

11/2019 04/2020 |

Females/Women | 67 | PANAS-NA | 1.93 (0.65) | 2.28 (0.79) | 0.34 (0.86) | 0.46 (0.12, 0.81) | –– | –– | –– | –– | |

| Males/Men | 35 | 1.88 (0.67) | 2.11 (0.66) | 0.23 (0.66) | 0.34 (− 0.14, 0.82) | ||||||||

|

Pierce49 Daly50 |

Pre-COVID-19 Waves 04/2020 09/2020 |

Females/Women |

7,18122,b 6,380 |

GHQ-12 | 12.00 (5.91) | 13.60 (7.14) |

1.60 (6.55)c 0.88 (NR)d |

0.24 (0.21, 0.28) 0.13 (0.10, 0.17) |

GHQ-12 ≥ 4 |

24.5 (22.5, 26.4)e 24.5 (22.5, 26.4)e |

36.8 (34.8, 38.9)e 25.0 (23.3, 26.8)e |

12.4 (9.9, 14.9)e 0.5 (− 1.8, 2.9)e |

|

| Males/Men |

8,19522,b 4,538 |

10.80 (4.99) | 11.50 (5.75) |

0.70 (5.38)c 0.03 (NR)d |

0.13 (0.10, 0.16) 0.01 (− 0.03, 0.04) |

16.7 (14.6, 18.7)e 16.7 (14.6, 18.7)e |

21.1 (19.0, 23.3)e 16.0 (14.0, 17.9)e |

4.5 (2.0, 7.0)e − 0.7 (− 2.9, 1.5)e |

|||||

| Savage59 |

10/2019 04/2020 |

Females/Women | 154 | WEMWBSf | 43.00 (9.00) | 40.00 (10.00) | − 3.00 (9.51) | 0.31 (0.09, 0.54) | –– | –– | –– | –– | |

| Males/Men | 60 | 47.00 (9.00) | 44.00 (10.00) | − 3.00 (9.51) | 0.31 (− 0.05, 0.67) | ||||||||

|

van der Velden51 van der Velden52 |

03/2019 11–12/2019 03/2020 11–12/2020 |

Females/Women |

2,020 2,062 |

–– | –– | –– | –– | –– | MHI-5 ≤ 59 |

18.9 (17.3, 20.7) 19.1 (17.4, 20.8) |

18.3 (16.7, 20.1) 17.8 (16.2, 19.5) |

− 0.6 (− 2.5, 1.3) − 1.3 (− 3.1, 0.6) |

|

| Males/Mmen |

1,962–1,963 2,002 |

14.6 (13.1, 16.3) 14.7 (13.2, 16.3) |

15.6 (14.1, 17.3) 15.9 (14.4, 17.6) |

1.0 (− 0.8, 2.7) 1.2 (− 0.5, 3.0) |

|||||||||

| Stress | |||||||||||||

| Lim60 |

NR/2018-2019 03-04/2020 |

Females/Women | 295 | PSS | 17.50 (8.00) | 16.40 (8.20) | − 1.10 (6.60) | − 0.14 (− 0.30, 0.03) | –– | –– | –– | –– | |

| Males/Men | 21 | 17.70 (6.60) | 18.10 (6.80) | 0.40 (8.00) | 0.06 (− 0.56, 0.68) | ||||||||

| Saraswathi58 |

12/2019 06/2020 |

Females/Women | 139 | DASS-21 Stress | 6.95 (7.22) | 8.88 (7.99) | 1.93 (7.61) | 0.25 (0.02, 0.49) |

DASS-21 Stress > 14 |

19.4 (13.7, 26.8) | 22.3 (16.2, 29.9) | 2.9 (− 4.9, 10.6) | |

| Males/Men | 78 | 7.95 (7.54) | 10.08 (8.50) | 2.13 (8.03) | 0.26 (− 0.05, 0.58) | 23.1 (15.1, 33.6) | 29.5 (20.5, 40.4) | 6.4 (− 5.6, 18.2) | |||||

| Savage59 |

10/2019 04/2020 |

Females/Women | 154 | PSS | 21.00 (7.00) | 24.00 (7.00) | 3.00 (7.00) | 0.43 (0.20, 0.65) | –– | –– | –– | –– | |

| Males/Men | 60 | 17.00 (6.00) | 21.00 (7.00) | 4.00 (6.52) | 0.61 (0.24, 0.97) | ||||||||

| Shanahan55 |

NR/2018 04/2020 |

Females/Women | 378 | PSS | 3.02 (0.98) | 3.10 (0.94) | 0.08 (0.96) | 0.08 (− 0.06, 0.23) | –– | –– | –– | –– | |

| Males/Men | 408 | 2.57 (0.86) | 2.74 (0.86) | 0.17 (0.86) | 0.20 (0.06, 0.34) | ||||||||

DASS-21 Anxiety = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale—Anxiety subscale; DASS-21 Depression = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale—Depression subscale; DASS-21 Stress = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale—Stress subscale; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; GHQ-12 = General Health Questionnaire-12; MHI-5 = Mental Health Index-5; PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule—Negative affect subscale; PROMIS Anxiety = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System—Anxiety subscale; PROMIS Depression = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System—Depression subscale; PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; SCAS-C = Spence Children's Anxiety Scale—Child; SCL-90-R = Symptom Check List-90 Revised; SMFQ = Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; SMFQ-C = Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire—Child Version; WEMWBS = Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale.

aPositive Hedge’s g sizes and increases in proportions above a threshold indicate worse mental health in COVID-19 compared to pre-COVID-19. Effects for measures where high scores = positive outcomes were reversed to reflect this. b Number included in fixed effects regression analysis from where majority of data were extracted. cBased on difference between 2020 and 2019 outcomes. dBased on estimate from fixed effects regression model that estimates within-person change accounting for pre-COVID-19 trends.eIncluded proportion outcomes from Daly50 since they reported for two time points. f Higher scale scores reflect better mental health; thus, direction of effect sizes reversed.

Figure 1.

Forest plots of standardized mean difference of the difference in change in continuous anxiety symptom scores (a), depression symptom scores (b), general mental health scores (c), and stress scores (d) between females or women and males or men. Positive numbers indicate greater negative change in mental health in females or women compared to males or men.

Figure 2.

Forest plots of standardized mean difference of the difference in change in proportion above a cut-off for anxiety (a), depression (b), general mental health (c), and stress (d) between females or women and males or men. Positive numbers indicate greater negative change in mental health in females or women compared to males or men. (c) reflects dichotomous COVID-19 mental health measured in early 2020, whereas (e) reflects measurements from late 2020 for Daly50 and van der Velden52.

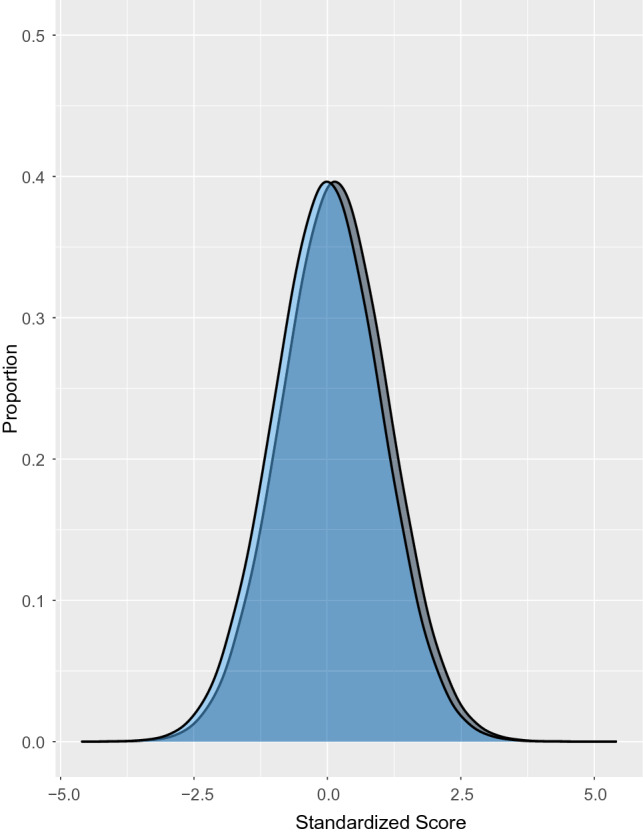

Anxiety, measured continuously, worsened significantly more for females or women than for males or men during COVID-19 (Fig. 1a; SMD change difference = 0.15, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.22; N = 4 studies54,56,58,60, 4,344 participants; I2 = 3.0%). General mental health, measured continuously, also worsened more for females or women than for males or men in early COVID-19 (Fig. 1c; SMD difference in change = 0.15, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.18; N = 3 studies49,53,59, 15,692 participants; I2 = 0.0%). This was predominantly based on a large population-based study from the United Kingdom49. That study did not report results from fall 2020 for continuous outcomes, but as shown in Table 2 and Figs. 2c and e, the difference in change between females or women and males or men decreased between early and late 2020 for dichotomous outcomes in the same cohort50. The magnitude of both statistically significant differences was small (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Illustration of the magnitude of change for SMD = 0.15 assuming a normal distribution. The hypothetical blue distribution represents pre-COVID-19 scores, and the grey distribution represents post-COVID-19 scores with a mean symptom increase of SMD = 0.15.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected women and gender minorities disproportionately8–17. There has been an assumption, seemingly confirmed by cross-sectional data collected during COVID-19, that overall mental health has worsened and that there have been even greater negative changes in mental health among women than for men21–31. We reviewed evidence from 12 studies (10 cohorts) that reported mental health changes from pre-COVID-19 to COVID-19 separately by sex or gender. We compared females or women with males or men; no studies compared gender minorities with any other group. Data were largely from March to June 2020, early in the pandemic. Syntheses of continuously measured anxiety symptoms (SMD = 0.15, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.22) and general mental health (SMD = 0.15, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.18) found that mental health worsened more for females or women than males or men, but the magnitude was small and far below thresholds that are typically considered clinically important (e.g., SMD = 0.50)61. None of the other 6 mental health outcomes that we examined (continuous depression symptoms and stress; dichotomous anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, general mental health, and stress) differed by sex or gender.

Sex and gender differences in mental health disorder prevalence, symptoms, and risk factors are well-established62–65. Likely risk factors include gender inequities and discrimination, economic disadvantage and poverty, higher rates of interpersonal stressors, and violence66,67, and many of these risk factors have been exacerbated for women during COVID-198–15. We did not identify any differences in mental health by sex or gender, however, that appeared to be substantive; all were 0.15 SMD or smaller, which is considered to be a small difference based on commonly used metrics (e.g., < 0.20 SMD)68 and below thresholds for clinical meaningfulness61.

Based on our findings, it is possible that despite the challenges women have faced, many have been resilient and that the mental health disaster that has been predicted by many has not occurred69. Overall, across populations, expected negative changes in mental health during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic levels have not been as dramatic as might have been expected3,70–72. To the best of our knowledge, there have been two systematic reviews that have compared symptoms prior to COVID-19 and after the start of the pandemic. The reviews used somewhat different methods, including study inclusion and exclusion criteria, but findings were consistent. Both reported that symptom scores on measures of general mental health, depression, and anxiety were stable or had worsened by small amounts during the pandemic4,5. This is consistent with the only study, to the best of our knowledge, that has evaluated prevalence of mental health disorders using validated diagnostic interviews rather than symptom changes. That study, which probabilistically sampled Norwegian adults in January to early March 2020 (pre-pandemic), mid-March to May 2020, and June to July 2020, reported that the prevalence of current mental disorders, assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (version 5.0), was stable across time periods73. Similarly, a study on suicide in 21 countries during early COVID-19 found that observed numbers of deaths from suicide was stable or decreased from pre-pandemic to the early pandemic months in all included jurisdictions based on an interrupted time-series analysis72.

Our findings, as well as those from other studies that have reported that mental health implications early in the pandemic may not have been as substantial as expected depart from what has been reported in some research and by the media. Three factors may feed this discrepancy. One is the publication of many cross-sectional studies that report proportions above cut-offs on self-report measures, which are not designed for that purpose74–78, and assume that what are perceived as high numbers, generally, or sex differences, comparatively, must not have been present pre-COVID-195. A second is the use of surveys that ask questions about well-being with COVID-19 explicitly assigned as a cause; illustrating the pitfalls of this, a study of over 2,000 young Swiss adult men found significant angst when questions were asked in this way, but no changes in validated measures of depression symptoms and stress from pre-COVID79. A third reason relates to news media reports that emphasize dramatic events and anecdotes without evidence that demonstrates changes69.

Strengths of our study include the use of rigorous systematic review methods. We searched 9 databases, including Chinese-language databases, without language restrictions and included studies that enabled the direct comparison of mental health changes by sex or gender. Our findings emphasize that we should not assume that mental health effects of COVID-19 have been much greater for females or women than for males or men during the pandemic. Indeed, across the 21 analyses we conducted, differences were consistently null or very small and no individual studies stood out as deviating from this overall finding. Nonetheless, one should be cautious about generalizing our findings to all populations and subgroups. First, included studies were conducted in 8 countries, and it is possible that there could have been differences in other countries, given that the pandemic has manifested itself differently across countries and that countries have managed the pandemic differently (e.g., length and severity of restrictions). Second, all but one of the included studies was on adults, and the findings may not be generalizable to children or adolescents. Third, there were not enough studies to attempt subgroup analyses by sociodemographic or other factors, such as professional groups, for example. Cross-sectional studies have reported that there could be differences in mental health by sex or gender that are related to sociodemographic variables (e.g., age, race or ethnicity) and professional roles (e.g., health care workers)80,81. Cross-sectional analyses, however, do not allow us to determine if any identified associations or differences may have been present prior to the pandemic, and if so, to what degree. Fourth, we were not able to evaluate the influence of potential risk and protective factors that may differ between sex or gender and if these might potentially explain some of the results observed. The information needed to do this was not provided in included studies. Fifth, we did not identify any studies that compared results from gender-diverse individuals to other gender groups. This highlights an important evidence gap in the literature, and indicates the need for more research on this population, especially given that several studies suggest that the mental health of this population group may have been affected negatively since pre-COVID-1916,82,83.

There are other limitations to consider in addition to generalizability. First, this review only included 12 studies from 10 cohorts, and many had limitations related to study sampling frames and recruitment methods, follow-up rates, and management of missing data. Second, our review only included studies with mental health outcomes early in the pandemic. This did not permit us to examine long-term trends in mental health as the pandemic progressed. It is possible that sex or gender differences absent in the early pandemic may have developed. For example, according to a United States Centers for Disease Control report on suicide-related weekly emergency department visits, the numbers for teenage females (aged 12–17 years) increased minimally in 2020, but were over 51% higher in 2021 compared to the same period in 2019, versus an increase of 4% among teenage males84. Analyses of overall mental health that have been reported and the results in our study are based on data from early in the pandemic, and it is not clear to what degree these findings would apply to later stages of the pandemic. Third, heterogeneity was high for some meta-analyses; it was low, however, for others, and results across 8 analyses did not differ substantively. Fourth, in calculating 95% CIs for within-group changes in proportions with the information provided in publications (pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 group proportions), we assumed that 50% of pre-COVID-19 cases continued to be cases during COVID-19. However, the maximum difference in any end point of a 95% CIs across analyses was 0.02 when we varied our assumption from 30 to 70%.

In sum, we identified small sex- or gender-based differences for anxiety symptoms and general mental health, continuously measured, but other outcomes (continuous depression symptoms and stress; dichotomous anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, general mental health, and stress) did not differ by sex or gender. This finding diverges from what has been reported from cross-sectional studies. These are aggregate results, though, and many individuals have certainly experienced negative mental health changes related to increased socioeconomic burden. It seems plausible, given the divergent ways that the pandemic has affected different people that many people are experiencing improved mental health, whereas large numbers of others may be experiencing worsened mental health, including new onset mental disorders among people without previous morbidity. Thus, mental health changes should continue to be monitored longitudinally in COVID-19, taking into consideration sex and gender, particularly in younger populations. Our research underlines that few studies report results by sex and gender. Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines85 emphasize that all studies should report results by sex and gender, even if there are not enough participants to draw sex- and gender-based conclusions. Reporting by sex and gender, even in small studies, facilitates synthesis of results across studies, which does allow conclusions to be drawn, even if primary studies do not have sufficiently large samples sizes to do this. Ongoing research in COVID-19 should include outcome reports by sex and gender. When not done, peer reviewers and editors should support authors to implement this guidance. Although we did not find aggregate sex differences and overall changes have been minimal, the pandemic has affected different individuals and groups differently. Health care providers should be alert to life changes that may be associated with vulnerability and to physical and emotional or cognitive symptoms that may reflect worsening mental health so that they can assess, if appropriate, and provide mental health care to those in need.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Y.S., Y.Wu., D.B.R., A.B., and B.D.T. were responsible for the study conception and design. J.T.B. was responsible for the design of the database searches. A.K. carried out the searches. T.D.S., Y.S., Y.Wu., C.H., Y.Wang., X.J., K.L., O.B., A.K., D.B.R., S.M., M.A., D.N., A.T., A.Y., I.T.V. and B.D.T. contributed to data extraction, coding, and evaluation of included studies. Y.S., C.H., and O.B. were responsible for study coordination. T.D.S., Y.S., Y.Wu., B.L., A.B., and B.D.T. were involved in data analysis. B.A., C.F., M.S.M., S.S., and G.T. contributed to interpretation of results as knowledge translation partners. T.D.S. and B.D.T. drafted the manuscript. All authors provided a critical review and approved the final manuscript. B.D.T. is the guarantor; he had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. B.D.T. is the corresponding author and attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CMS-171703; GA4-177758; MS1-173070) and McGill Interdisciplinary Initiative in Infection and Immunity Emergency COVID-19 Research Fund (R2-42). YWu and BL were supported by Fonds de recherche du Québec—Santé (FRQS) Postdoctoral Training Fellowships. DBR was supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. AB was supported by a FRQS senior researcher salary award. BDT was supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair.

Data availability

All data used in the study are available in the manuscript and its tables or online at https://www.depressd.ca/covid-19-mental-health.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-14746-1.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 2.World Health Organization. Impact of COVID-19 on people’s livelihoods, their health and our food systems: joint statement by ILO, FAO, IFAD and WHO. https://www.who.int/news/item/13-10-2020-impact-of-covid-19-on-people%27s-livelihoods-their-health-and-our-food-systems (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 3.Aknin, L, et al. The Pandemic Did Not Affect Mental Health the Way You Think. The Atlantic.https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/07/covid-19-did-not-affect-mental-health-way-you-think/619354/ (2021). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 4.Robinson E, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J. Affect Disord. 2022;296:567–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun, Y. et al. Comparison of mental health symptoms prior to and during COVID-19: evidence from a living systematic review and meta-analysis. Preprint at 10.1101/2021.05.10.21256920 (2021). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 6.Peckham H, et al. Male sex identified by global COVID-19 meta-analysis as a risk factor for death and ITU admission. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:6317. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19741-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Islam N, et al. Excess deaths associated with covid-19 pandemic in 2020: age and sex disaggregated time series analysis in 29 high income countries. BMJ. 2021;373:n1137. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connor J, et al. Health risks and outcomes that disproportionately affect women during the Covid-19 pandemic: a review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020;266:113354. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed SB, Dumanski SM. Sex, gender and COVID-19: a call to action. Can. J. Public Health. 2020;111:980–983. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00417-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Gender and COVID-19: advocacy brief—14 May 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Advocacy_brief-Gender-2020.1 (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 11.United Nations. Policy brief: the impact of COVID-19 on women—9 April 2020. https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-impact-covid-19-women (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 12.Azcona, G. et al. From insight to action: gender inequality in the wake of COVID-19. UN Womenhttps://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/09/gender-equality-in-the-wake-of-covid-19 (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 13.De Paz, C., Muller, M., Munoz Boudet, A.M. & Gaddis, I. Gender dimensions of the COVID-19 pandemic. World Bank Grouphttps://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33622#:~:text=With%20regards%20to%20health%20outcomes,health%20outcomes%20in%20several%20countries (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 14.Grall, T. Custodial mothers and fathers and their child support: 2015. United States Census Bureauhttps://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-262.html (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 15.Piquero AR, Jennings WG, Jemison E, Kaukinen C, Knaul FM. Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic - evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crim. Justice. 2021;74:101806. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2021.101806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flentje A, et al. Depression and anxiety changes among sexual and gender minority people coinciding with onset of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020;35:2788–2790. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05970-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittington, C., Hadfield, K. & Calderón, C. The Lives and livelihoods of many in the LGBTQ community are at risk amidst the COVID-19 crisis. Human Rights Campaign Foundationhttps://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/COVID19-IssueBrief-032020-FINAL.pdf (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 18.Hassan, M.F., Hassan, N.M., Kassim, E.S. & Said, Y.M.U. Financial wellbeing and mental health: a systematic review. St. Appl. Econ.39 (2021).

- 19.Vizheh M, et al. The mental health of healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2020;19:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40200-020-00643-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dillon G, Hussain R, Loxton D, Rahman S. Mental and physical health and intimate partner violence against women: a review of the literature. Int. J. Family Med. 2013;2013:313909. doi: 10.1155/2013/313909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaques-Aviñó C, et al. Gender-based approach on the social impact and mental health in Spain during COVID-19 lockdown: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e044617. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, et al. Psychosocial impacts of the COVID-19 quarantine: a study of gender differences in 59 countries. Medicina. 2021;57:789. doi: 10.3390/medicina57080789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu S, et al. Gender differences in mental health problems of healthcare workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;137:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seens H, et al. The role of sex and gender in the changing levels of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Women’s Health. 2021;17:1–9. doi: 10.1177/17455065211062964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon, D. Mental health got worse during covid-19, especially for women, new survey shows. Forbeshttps://www.forbes.com/sites/debgordon/2021/05/28/mental-health-got-worse-during-covid-19-especially-for-women-new-survey-shows/?sh=17e96a792d03 (2021). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 26.Grose, J. America’s mothers are in crisis. Is anyone listening to them? The New York Timeshttps://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/02/04/parenting/working-moms-coronavirus.html (2021). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 27.Kluger, J. The coronavirus pandemic’s outsized effect on women’s mental health around the world. Timehttps://time.com/5892297/women-coronavirus-mental-health/ (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 28.Lindau ST, et al. Change in health-related socioeconomic risk factors and mental health during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey of US women. J. Womens Health. 2021;30:502–513. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.García-Fernández L, et al. Gender differences in emotional response to the COVID-19 outbreak in Spain. Brain Behav. 2021;11:e01934. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moyser, M. Gender differences in mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Statistics Canadahttps://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00047-eng.htm (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 31.Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. COVID-19 pandemic adversely affecting mental health of women and people with children. https://www.camh.ca/en/camh-news-and-stories/covid-19-pandemic-adversely-affecting-mental-health-of-women-and-people-with-children (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 32.Kessler RC, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: meta-analysis of diagnosis and symptoms. Psychol. Bull. 2017;143:783–822. doi: 10.1037/bul0000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patil PA, Porche MV, Shippen NA, Dallenbach NT, Fortuna LR. Which girls, which boys? The intersectional risk for depression by race and ethnicity, and gender in the US. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018;66:51–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLean CP, Anderson ER. Brave men and timid women? A review of the gender differences in fear and anxiety. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009;29:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011;45:1027–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thombs BD, et al. Curating evidence on mental health during COVID-19: a living systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020;133:110113. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Living systematic review of mental health in COVID-19. https://www.depressd.ca/covid-19-mental-health. Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 39.Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 41.World Health Organization. Gender and health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/gender#tab=tab_1. Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 42.Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools for use in JBI systematic reviews: Checklist for prevalence studies. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 43.Hedges LV. Estimation of effect from a series of independent experiments. Pyschol. Bull. 1982;92:490–499. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.92.2.490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Effect sizes based on means in Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Wiley and Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agresti A, Coull BA. Approximate is better than “exact” for interval estimation of binomial proportions. Am. Stat. 1998;52:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newcombe RG. Improved confidence intervals for the difference between binomial proportions based on paired data. Stat. Med. 1998;17:2635–2650. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981130)17:22<2635::AID-SIM954>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newcombe RG. Estimating the difference between differences: measurement of additive scale interaction for proportions. Stat. Med. 2001;20:2885–2893. doi: 10.1002/sim.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwarzer G. meta: An R package for meta-analysis. R News. 2007;7:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pierce M, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Daly M, Robinson E. Longitudinal changes in psychological distress in the UK from 2019 to September 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from a large nationally representative study. Psychiatry Res. 2021;300:113920. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van der Velden PG, Contino C, Das M, van Loon P, Bosmans MWG. Anxiety and depression symptoms, and lack of emotional support among the general population before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. A prospective national study on prevalence and risk factors. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;277:540–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van der Velden, P.G., Marchand, M., Das, M., Muffels, R. & Bosmans, M. The prevalence, incidence and risk factors of mental health problems and mental health services use before and 9 months after the COVID-19 outbreak among the general Dutch population. A 3-wave prospective study. Preprint at 10.1101/2021.02.27.21251952. (2021). Accessed June 3, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Megías-Robles A, Gutiérrez-Cobo MJ, Cabello R, Gómez-Leal R, Fernández-Berrocal P. A longitudinal study of the influence of concerns about contagion on negative affect during the COVID-19 lockdown in adults: the moderating effect of gender and resilience. J. Health. Psychol. 2021;27:1165–1175. doi: 10.1177/1359105321990794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rimfeld K, et al. Genetic correlates of psychological responses to the COVID-19 crisis in young adult twins in Great Britain. Behav. Genet. 2021;51:110–124. doi: 10.1007/s10519-021-10050-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shanahan L, et al. Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychol. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1017/S003329172000241X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Magson NR, et al. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Youth. Adolesc. 2021;50:44–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dong, X. L. Influence study of COVID-2019 on mental health of normal college students. Xin Li Yue Kan.15, (2020) (in Chinese).

- 58.Saraswathi I, et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on the mental health status of undergraduate medical students in a COVID-19 treating medical college: a prospective longitudinal study. PeerJ. 2020;8:e10164. doi: 10.7717/peerj.10164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Savage MJ, et al. Mental health and movement behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic in UK university students: Prospective cohort study. Ment. Health Phy. Act. 2020;19:100357. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lim, S.S. et al. Unexpected changes in physical and psychological measures among Georgia lupus patients during the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, March 30–April 21, 2020. Arthritis Rheumatol.72, suppl. 10; https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/unexpected-changes-in-physical-and-psychological-measures-among-georgia-lupus-patients-during-the-early-weeks-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-the-united-states-march-30-april-21-2020/. (2020). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 61.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med. Care. 2003;41:189–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riecher-Rössler A. Prospects for the classification of mental disorders in women. Eur. Psychiatry. 2010;25:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boyd A, et al. Gender differences in mental disorders and suicidality in Europe: results from a large cross-sectional population-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 2015;173:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seedat S, et al. Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2009;66:785–795. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wittchen HU, et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:655–679. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuehner C. Why is depression more common among women than men? Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:146–158. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Riecher-Rössler A. Sex and gender differences in mental disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:8–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30348-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. Academic Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bentall, R. Has the pandemic really cause a ‘tsunami’ of mental health problems? The Guardianhttps://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/feb/09/pandemic-mental-health-problems-research-coronavirus (2021). Accessed June 3, 2022.

- 70.Aknin LB, et al. Policy stringency and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of data from 15 countries. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e417–e426. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00060-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ding K, et al. Mental health among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a cross-sectional multi-country comparison. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:2686. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pirkis J, et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:579–588. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00091-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Knudsen AK, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders, suicidal ideation and suicides in the general population before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway: A population-based repeated cross-sectional analysis. Lancet Reg. Health. 2021;4:100071. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thombs BD, Kwakkenbos L, Levis AW, Benedetti A. Addressing overestimation of the prevalence of depression based on self-report screening questionnaires. CMAJ. 2018;190:E44–E49. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Levis B, et al. Comparison of depression prevalence estimates in meta-analyses based on screening tools and rating scales versus diagnostic interviews: a meta-research review. BMC Med. 2019;17:65. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1297-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Levis B, et al. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores do not accurately estimate depression prevalence: individual participant data meta-analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020;122:115–128.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lyubenova A, et al. Depression prevalence based on the edinburgh postnatal depression scale compared to structured clinical Interview for DSM Disorders classification: systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2021;30:e1860. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brehaut E, et al. Depression prevalence using the HADS-D compared to SCID major depression classification: an individual participant data meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020;139:110256. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marmet S, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 crisis on young Swiss men participating in a cohort study. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2021;151:w30028. doi: 10.4414/smw.2021.w30028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brotto LA, et al. The influence of sex, gender, age, and ethnicity on psychosocial factors and substance use throughout phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0259676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pappa S, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bavinton BR, et al. Increase in depression and anxiety among australian gay and bisexual men during COVID-19 restrictions: findings from a prospective online cohort study. Arch Sex Behav. 2022;51:355–364. doi: 10.1007/s10508-021-02276-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kidd JD, et al. Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of transgender and gender nonbinary individuals engaged in a longitudinal cohort study. J. Homosex. 2021;68:592–611. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2020.1868185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yard E, et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 2019–May 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021;70:888–894. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heidari, S, et al. Sex and gender equity in research: rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Res Integr Peer Rev.1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used in the study are available in the manuscript and its tables or online at https://www.depressd.ca/covid-19-mental-health.