To the Editor: The B.1.1.529 (omicron) variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has a shorter incubation period and a higher transmission rate than previous variants.1,2 Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended shortening the strict isolation period for infected persons in non–health care settings from 10 days to 5 days after symptom onset or after the initial positive test, followed by 5 days of masking.3 However, the viral decay kinetics of the omicron variant and the duration of shedding of culturable virus have not been well characterized.

We used longitudinal sampling of nasal swabs for determination of viral load, sequencing, and viral culture in outpatients with newly diagnosed coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19).4 From July 2021 through January 2022, we enrolled 66 participants, including 32 with samples that were sequenced and identified as the B.1.617.2 (delta) variant and 34 with samples that were sequenced and identified as the omicron subvariant BA.1, inclusive of sublineages. Participants who received Covid-19–specific therapies were excluded; all but 1 participant had symptomatic infection. This study was approved by the institutional review board and the institutional biosafety committee at Mass General Brigham, and informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

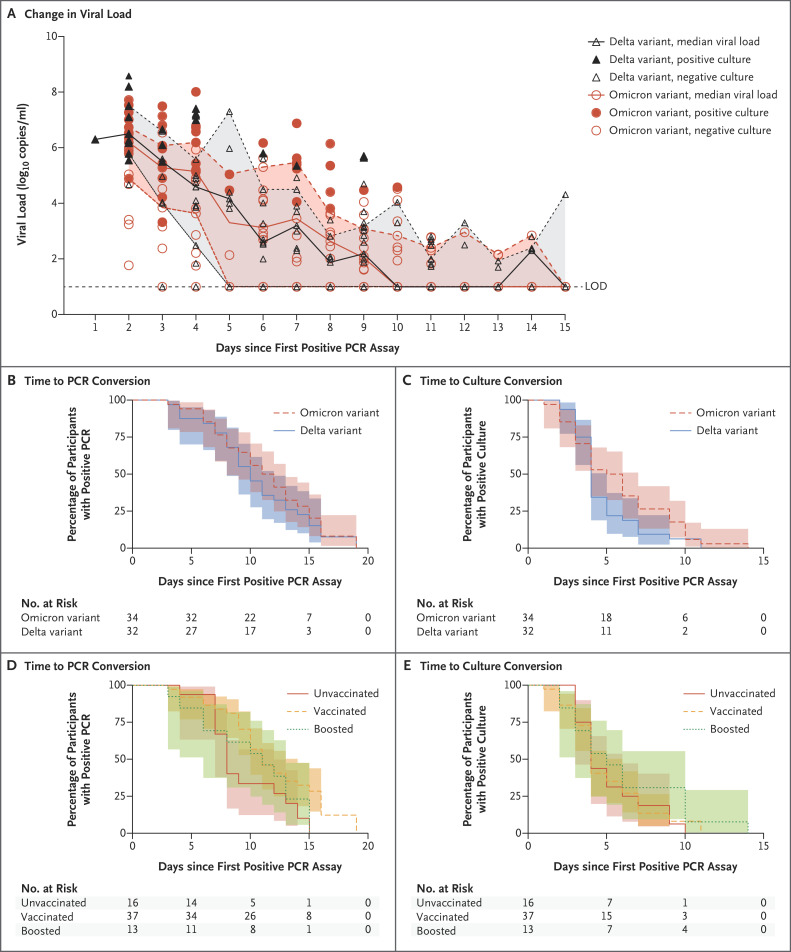

The characteristics of the participants were similar in the two variant groups except that more participants with omicron infection had received a booster vaccine than had those with delta infection (35% vs. 3%) (Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org). In an analysis in which a Cox proportional-hazards model that adjusted for age, sex, and vaccination status was used, the number of days from an initial positive polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) assay to a negative PCR assay (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.33 to 1.15) and the number of days from an initial positive PCR assay to culture conversion (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.44 to 1.37) were similar in the two variant groups (Figure 1A through 1C and S1 through S3, and Tables S3 through S5). The median time from the initial positive PCR assay to culture conversion was 4 days (interquartile range, 3 to 5) in the delta group and 5 days (interquartile range, 3 to 9) in the omicron group; the median time from symptom onset or the initial positive PCR assay, whichever was earlier, to culture conversion was 6 days (interquartile range, 4 to 7) and 8 days (interquartile range, 5 to 10), respectively. There were no appreciable between-group differences in the time to PCR conversion or culture conversion according to vaccination status, although the sample size was quite small, which led to imprecision in the estimates (Figure 1D and 1E).

Figure 1. Viral Decay and Time to Negative Viral Culture.

Panel A shows viral-load decay from the time of the first positive polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) assay. Viral loads from nasal-swab samples obtained from individual participants are shown. Each circle or triangle represents a sample obtained on the specified day. The median viral load at each time point for each variant is also shown. LOD denotes limit of detection. Panels B through E show Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the time from an initial positive PCR assay to a negative PCR assay, according to viral variant (Panel B) and vaccination status (Panel D), and the time from an initial positive PCR assay to a negative viral culture, according to viral variant (Panel C) and vaccination status (Panel E). In all panels, shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. Sequencing showed that all omicron variant strains were the subvariant BA.1, inclusive of sublineages.

In this longitudinal cohort of participants, most of whom had symptomatic, nonsevere Covid-19 infection, the viral decay kinetics were similar with omicron infection and delta infection. Although vaccination has been shown to reduce the incidence of infection and the severity of disease, we did not find large differences in the median duration of viral shedding among participants who were unvaccinated, those who were vaccinated but not boosted, and those who were vaccinated and boosted.

Our results should be interpreted within the context of a small sample size, which limits precision, and the possibility of residual confounding in comparisons according to variant, vaccination status, and the time period of infection. Although culture positivity has been proposed as a possible proxy for infectiousness,5 additional studies are needed to correlate viral-culture positivity with confirmed transmission in order to inform isolation periods. Our data suggest that some persons who are infected with the omicron and delta SARS-CoV-2 variants shed culturable virus more than 5 days after symptom onset or an initial positive test.

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

This letter was published on June 29, 2022, and updated on July 6, 2022, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Supported by grants (to Drs. Goldberg, J.Z. Li, Lemieux, Siedner, and Barczak) from the Massachusetts Consortium for Pathogen Readiness, a grant (to Dr. Vyas) from the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Medicine, and a grant (P30 AI060354, to the BSL3 laboratory where viral culture work was performed) from the Harvard University Center for Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Research.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Abbott S, Sherratt K, Gerstung M, Funk S. Estimation of the test to test distribution as a proxy for generation interval distribution for the omicron variant in England. January 10, 2022. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.01.08.22268920v1). preprint.

- 2.Ito K, Piantham C, Nishiura H. Relative instantaneous reproduction number of omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant with respect to the delta variant in Denmark. J Med Virol 2022;94:2265-2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC updates and shortens recommended isolation and quarantine period for general population. December 27, 2021. (https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s1227-isolation-quarantine-guidance.html).

- 4.Siedner MJ, Boucau J, Gilbert RF, et al. Duration of viral shedding and culture positivity with postvaccination SARS-CoV-2 delta variant infections. JCI Insight 2022;7(2):e155483-e155483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature 2020;581:465-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.