Summary

Background

This is a paucity of data regarding plastic surgeons' opinions on robotic-assisted surgery (RAS). We developed a questionnaire aimed to survey plastic surgeons regarding training in robotics, concerns about widespread implementation, and new research directions.

Methods

A survey was created using Google Forms and sent to practicing plastic surgeons and trainees. Responses regarding desired conference proceedings about robotics, robotic residency training, and perceived barriers to implementation were elicited. Survey responses were utilized to direct a systematic review on RAS in plastic surgery.

Results

The survey received 184 responses (20.4%; 184/900). The majority (92.8%) of respondents were/are plastic surgery residents, with the most common fellowships being microsurgery (39.2%). Overall, 89.7% of respondents support some integration of robotics in the future of plastic surgery, particularly in pelvic/perineum reconstruction (56.4%), abdominal reconstruction (46.5%), microsurgery (43.6%), and supermicrosurgery (44.2%). Many respondents (66.1%) report never using a robot in their careers. Respondents expressed notable barriers to widespread robotic implementation, with cost (73.0%) serving as the greatest obstacle. A total of 10 studies (pelvic/perineum = 3; abdominal = 3; microsurgery = 4) were included after full-text review.

Conclusions

Evidence from our survey and review supports the growing interest and utility of RAS within the plastic and reconstructive surgery (PRS) and mirrors the established trend in other surgical subspecialties. Cost analyses will prove critical to implementing RAS within PRS. With validated benefits, plastic surgery programs can begin creating dedicated curricula for RAS.

Keywords: robotic-assisted, abdominal wall, microsurgery, pelvic reconstruction, plastic surgery, systematic review

Introduction

The use of robotics in surgery has captivated patients and physicians alike since its FDA-approval1 and the first reported case of a robotic-assisted laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 2002.2 Robotic-assisted surgery (RAS) publications have exponentially increased from over 100 in 20003 to over 3,000 by 2021. Many surgical subspecialties have readily embraced RAS, including urology,4 gynecology,5 and cardiothoracic surgery.6 Yet, plastic and reconstructive surgery (PRS) has been slow to adopt RAS technology. Since the first publication of a porcine free flap by Katz et al. in 2005,7 PRS publications on RAS have only modestly increased to 78 in 2021; compare this to other specialties that have hundreds to thousands of publications per year.

PRS is often considered an innovative specialty that has spearheaded innovation within the surgery. It is also a specialty that commonly works in tandem with other specialties that use RAS. Therefore, PRS surgeons should investigate potential uses for and learn how to incorporate RAS into their surgical armamentarium.

Only one study has previously surveyed PRS surgeons regarding RAS.8 However, this study focused on surgeons who already practiced RAS and was limited in scope to head and neck surgery. This report aimed to nationally survey PRS residents, fellows, and physicians regarding RAS. To complement this survey data, we also present a systematic review focusing on the PRS subspecialties and preferred areas of research focus directed by the survey findings.

Materials and Methods

Survey

To direct the systematic review that follows, an 18-question survey was created using Google Forms (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA). The survey was sent to plastic surgeons and trainees using mailing lists and conference committees. Regional information collected included the respondents’ current region of practice and size/type of city in which practice is located. Academic training data obtained included type of residency and fellowship training, years, and type of practice. Respondents were asked what type of plastic surgery field would likely most benefit from RAS. Responses regarding desired conference proceedings about robotics, robotic residency training, and perceived barriers to implementation were elicited.

Systematic Review

The top three fields of plastic surgery perceived to most benefit from RAS by respondents directed the review of literature. Top conference topics and perceived barriers to implementation were used as primary outcome measures.

Study Identification

The following databases were queried (articles dating up to 2021) for relevant published studies: PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science.

Search Terms and Data Extraction

The systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews. Search terms to identify studies involving RAS included PRS, plastic surgery, abdominal wall repair/reconstruction, ventral hernia, pelvic/perineum reconstruction, microsurgery, supermicrosurgery, da Vinci, robot-assisted, and robotic-assisted. After duplicates were removed, the remaining titles/abstracts were screened for relevance; selected abstracts were then reviewed for full-text review. Three reviewers critiqued abstracts, manuscripts, and extracted data from selected papers using a standardized collection table.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Studies in this systematic review included prospective and retrospective cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, randomized control trials, case-control, and case series. Only publications in English were reviewed. We excluded case reports, review papers, technical reports, and case series with fewer than 10 patients. To qualify for inclusion, studies had to focus on RAS in PRS. Regions of focus included pelvic/perineum, abdominal wall, microsurgery, and supermicrosurgery.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures were the efficacy, cost, and complication rate of robotic-assisted plastic surgery. With this information, we synthesized the data extracted to help summarize the utility of RAS compared to non-robotic options.

Data Analysis

Given the heterogeneity of the papers, quantitative analysis was not performed. Instead, a qualitative analysis of the pertinent findings from each of the eligible papers is presented systematically in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

Table 1.

Characterization of all studies of robotic-assisted abdominal wall reconstruction with greater than 10 patients.

| Author (Year) | Type of Study | Level of Evidence | Population | Cohort size | Control group | Mean age (%female) | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Mean Follow-Up | Outcomes Measured | Results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shakir et al. (2021) | retrospective | II | Endoscopic, laparoscopic, and robotic harvest of deep inferior epigastric vessels Pennsylvania, USA |

135 3 (robotic) |

94 (endoscopic) 38 (total extraperitoneal laparoscopic (TEP-lap)) |

52.2 (endoscopic) 51.7 (laparoscopic) 53.2 (robotic) |

>18 yo. Underwent two-stage autologous breast reconstruction Preoperative computed tomographic angiography > 3 mo. follow-up |

< 90 days follow-up | > 3 mo. | Flap survival Intraoperative complications related to harvest (conversion to open, bleeding, intra-abdominal injury) Postoperative complications |

Flap loss (n = 2) Abdominal wall hematoma (n = 1) requiring operative takeback in endoscopic cohort No flap losses or abdominal wall complications in either TEP-lap or robotic cohorts |

Endoscopic operative time: 344.0 min. Laparoscopic operative time: 425.2 min. Robotic operative time: 535.3 min. Additional disposable costs: Endoscopic: $250 TEP-lap: $500 Robotic: $1500 |

| Choi et al. (2021) | Retrospective | IV | Deep inferior epigastric artery flap harvest Seoul, South Korea |

17 | 4 | N/A | Length of intramuscular pedicle less than 5 cm Either one large perforator or multiple perforators |

N/A | N/A | Operative time of harvest Total operation time |

Avg. operation time of robotic harvest: 65 mins Total operation time: 487 mins |

No comparisons to convential flap harvest Mention of high cost but no cost analysis compared to conventional flap harvest |

| Pedersen et al. (2014) | Case series | IV | Rectus abdominis harvest for extremity coverage and pelvic surgery Chicago, USA |

10 | N/A | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | less than 12 mo. | Hernia or bulge formation Infection |

No hernia or bulge at final followup 1 patient: stage 1 decubitus ulcer |

Average setup time: 15 min. Average harvest time: 45 min. |

Table 2.

Characterization of all studies of robotic-assisted microsurgery with greater than 10 patients.

| Author (Year) | Type of Study | Level of Evidence | Population | Cohort size | Control group | Mean age (%female) | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Mean Follow-Up | Outcomes Measured | Results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| van Mulken et al., 2020 | Prospective | II | Women with breast-cancer related lymphadema Maastricht, Netherlands |

20 Robot, n = 8 |

Manual, n = 12 | 60 years (100%) | Women w/ breast cancer | Not reported | 3 months | Use of compressive garment Manual lymph drainage Mean Lymph-ICF score Mean Upper Extremity Lymphadema (UEL) index of the affected arm |

Daily compressive garment: Robot: 1/8 (12.5%) Manual: 2/12 (16.7%) No sig. differences in mean Lymph-ICF score at 1m or 3m No sig. differences in UEL index at 1m or 3m |

Short f/u period Small sample size Neither surgeon nor patient was blinded to group assignment |

| Boyd et al., 2006 | Case series | IV | Patients with need for TRAM, SGA, SIEA, and SGAP flaps Weston, Florida |

20 (22 flaps) | N/A | 53.7 | Patients with need for TRAM, SGA, SIEA, and SGAP flaps | Not reported | Not reported | Mean time for robotic harvest Mean ICU time Mean chest tube time Mean admission Pedicle and flap properties |

Mean robot harvest time: 113 min Mean ICU time: 2.95 days Mean chest tube time: 2.10 days Mean admission: 7.20 days Complications: Hematomas (n = 6), flap loss (n = 2), positional neuropraxia (n = 2), pneumothroax (n = 1), MRSA pneumonia (n = 1), Mild fat necrosis (n = 1) |

High complication rate No long-term outcomes Expense of robot and difficulty training |

| McCullough et al., 2018 | Retrospective | IV | Men w/ sympathetic hypogonadism undergoing robot-assisted microscopic varicocelectomy (RAMV) Albany, NY |

140 | N/A | 34.5 years (0%) | Normal karyotype and negative microdeletion studies >1 year of infertility Varicocoeles |

No varicocele | Not reported | Operative time Testicular volume, median testosterone, sperm concentration, motility, and WHO morphology Complications Need for pain medications >24h |

No sig. difference in operative time for RAMV vs. traditional Median T and free T increased by 44.3% (p < 0.001) Sperm concentration increased by 37.3% (p<0.03) No difference in sperm motility or WHO morphology 9/258 (3.5%) had complications 37.3% used pain medications >24 h |

High failure rate/persistence rate: 9.7% Comparison to historical controls |

| Lai et al., 2019 | Retrospective | IV | H/N Cancer Patients Taichung, China |

15 17 robot-assisted microanastamoses |

25 microanastamoses with standard operating microscope/hand sewing technique | 52.93 | Patients with H/N SCC | Not reported | 115 months | Operating time Number of suture stitches needed for vessel anastomosis Vessel-related complications Flap survival Outcomes |

Operating time sig. longer for robot No intraoperative complications All flaps survived Recipient blood vessel in robot group non-sig. smaller than traditional Donor blood vessel diameter in robot group sig. smaller than traditional |

Small sample size |

Table 3.

Characterization of all studies of robotic-assisted pelvic/perineum reconstruction with greater than 10 patients.

| Author (Year) | Type of Study | Level of Evidence | Population | Cohort size | Control group | Mean age (%female) | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Mean Follow-Up | Outcomes Measured | Results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chong et al., 2015 | Retrospective | IV | Patients undergoing abdominoperineal reconstruction with gracilis flap from 2010-2012 Dallas, TX |

16 | N/A | 62 ± 8 years (31.3%) |

Not reported | Not reported | 5-40 months | OR time Major and minor perineal complication Donor site complication Abdominal wound complication Deep venous thrombosis 30 day mortality Hospitalization Days until ambulation |

Major perineal wound complication: 6% minor perineal complication: 19% Gracilis donor site surgical site infection: 3 (19%) Abdominal surgical-site infections: 4 (25%) No abdominal, parastomal, or perineal hernias or bulges No flap losses |

|

| Dy et al., 2021 | Retrospective | IV | Transgender women undergoing Robotic-assisted peritoneal flap gender-affirming vaginoplasty (RPGAV) New York City, NY |

100 (Xi = 47; SP = 53) |

N/A | 36.2 years (Not reported) |

Not reported | Patients with <6 mo of follow-up were excluded. | 11.9 months | Perioperative details (operative time and blood loss) Complications (intra- and postoperative) Postoperative neovaginal dimensions (patient-reported maximum dilator depth and size at the most recent follow-up) |

Average procedure times were 4.2 and 3.7 h in Xi and SP cohorts (p <0.001). Complications: Transfusion (6%) - 5 (11%) in Xi and 1 (2%) in SP system (p = 0.01) Vaginal stenosis (7%) - 6 (13%) in Xi and 1 (2%) in SP system (p = 0.003) Rectovaginal fistula (1%) - 0 in Xi and 1 (2%) in SP system (p = 0.181) Bowel obstruction (2%) - 0 in Xi and 2 (4%) in SP system (p = 0.057) |

Comparing da Vinci Xi robot (Xi) vs. da Vinci Single Port (SP) robot |

| Dy et al., 2021 | Retrospective | IV | Patients underwent robotic peritoneal flap revision vaginoplasty from 2017 to 2020 New York City, NY |

24 transgender women | N/A | 39 years (100%) |

Robotic peritoneal flap revision vaginoplasty Primary penile inversion vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty 6-month follow up appointment |

Not reported | 13.5 months | Postoperative neovaginal dimensions complications |

No intraoperative peritoneal flap harvest complications Post-operative: 1: Bleeding from a prostatic neurovascular bundle requiring perineal suture ligation under anesthesia. 2: granulation tissue at the junction of the neovaginal skin and peritoneal flap 1: curettage and surgical release of scar tissue at 5 months post-op 1: curettage of granulation tissue at 6 months post-op |

Revision vaginoplasty using robotic transabdominal canal dissection and harvest of peritoneal flaps 4 patients (17%) lost to further follow up Small sample size Short follow up |

Results

Respondent Demographics

The survey received a 20.4% (184/900) response rate. Respondents lived and practiced in the Southwest (31.1%), Northeast (21.5%), Midwest (20.3%), Southeast (13.6%), and Northwest (6.2%). Over 82.8% lived in a major metropolitan area (> 250,000 residents) and 17.2% lived in a suburban area (100,000–250,000 residents). Most (62.8%) worked in an academic setting, whereas 16.1% worked in private practice. Residents made up 11.4% of those surveyed. One-third (33.5%) of respondents had been in practice for one to ten years. The most common residency training was PRS (92.8%). Common fellowships included microsurgery (39.2%), hand (26.8%), craniofacial (14.4%), and burn surgery (7.2%). A majority of respondents had never performed RAS (66.1%). A total of 89.7% of respondents believed that RAS should be implemented into future plastic surgery residency training. Among residents (n = 21), 18 (85.7%) believed RAS should be implemented into training. Of those with greater than 21 years of experience (n = 50), 45 (90.0%) responded that RAS should be implemented. Overall, 10.3% (n = 18) believe RAS should not be integrated into residency training.

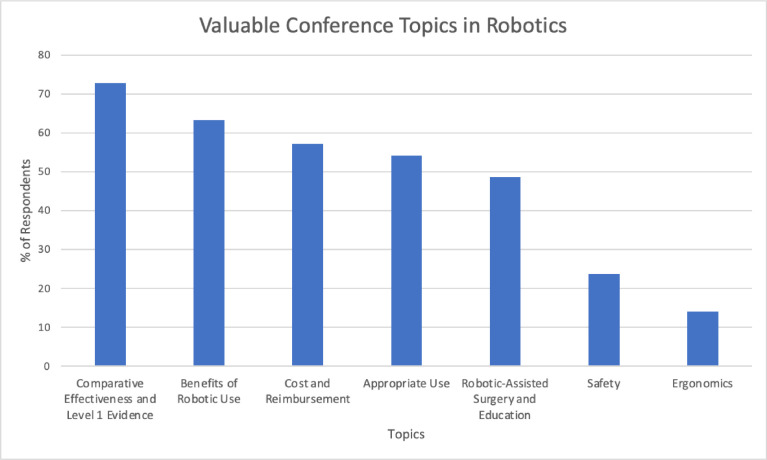

Most Valuable Conference Topics

Most respondents answered that the comparative effectiveness of RAS to non-robotic options and level 1 evidence (72.9%) was the most valuable conference topic (Figure 1). Other valuable conference topics included the benefits of robotic use (63.3%) and the cost and reimbursement of RAS (57.1%). Less than half (48.6%) wanted to learn about RAS training. Few of those surveyed (23.7%) found surgical safety a relevant conference topic.

Figure 1.

Valuable conference topics in robotic-assisted surgery.

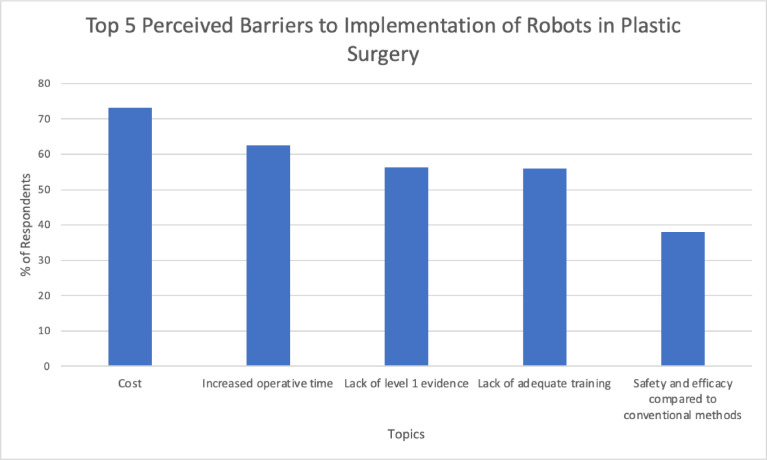

Barriers to Implementation

The majority (73.0%) of respondents perceive cost to be a major barrier to robot implementation in plastic surgery. Respondents believed increased operative time (62.9%), lack of level 1 evidence (56.2%), and lack of adequate training (55.6%) to also be significant barriers. Safety and efficacy were cited by 38.2% as well (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Top 5 perceived barriers to implementation of robotic-assisted surgery in plastic surgery.

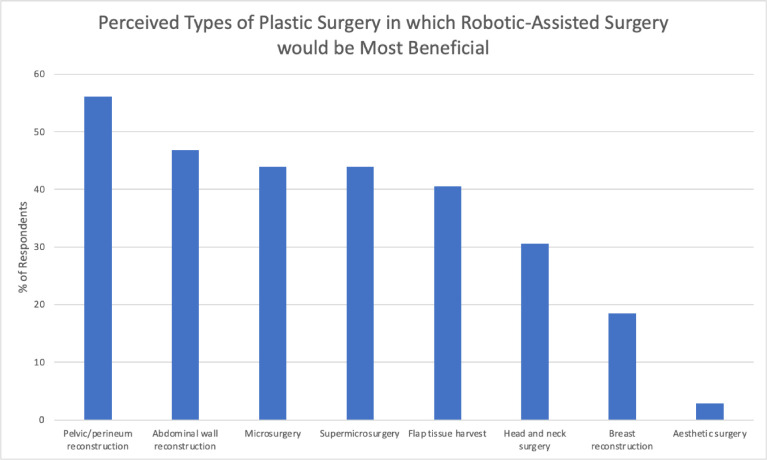

Types of Plastic Surgery in which RAS would be Most Beneficial

The top five types of plastic surgery in which RAS was perceived to be most beneficial were as follows: (1) Pelvic/perineum reconstruction (56.4%), (2) abdominal wall reconstruction (46.5%), (3) microsurgery (43.6%), (4) supermicrosurgery (44.2%), and (5) flap tissue harvest (40.7%). Head and neck surgery (30.8%), breast reconstruction (18.0%), and aesthetic surgery (2.9%) were also cited (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Perceived types of plastic surgery in which robotic-assisted surgery would be most beneficial.

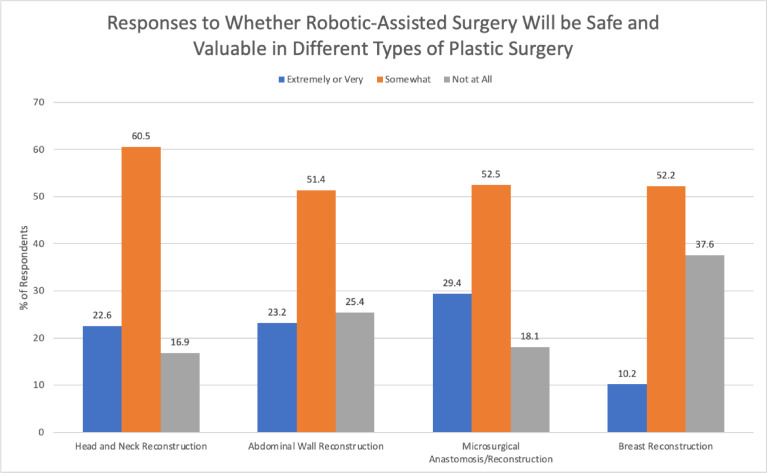

Responses to Whether RAS Will Be Safe and Valuable in Different Types of Plastic Surgery

The majority of the respondents considered RAS safe and valuable in head and neck reconstruction (83.0%), microsurgical anastomosis/reconstruction (81.8%), abdominal wall reconstruction (74.4%), and breast reconstruction (62.1%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Responses to whether robotic-assisted surgery will be safe and valuable in different types of plastic surgery.

Systematic Review

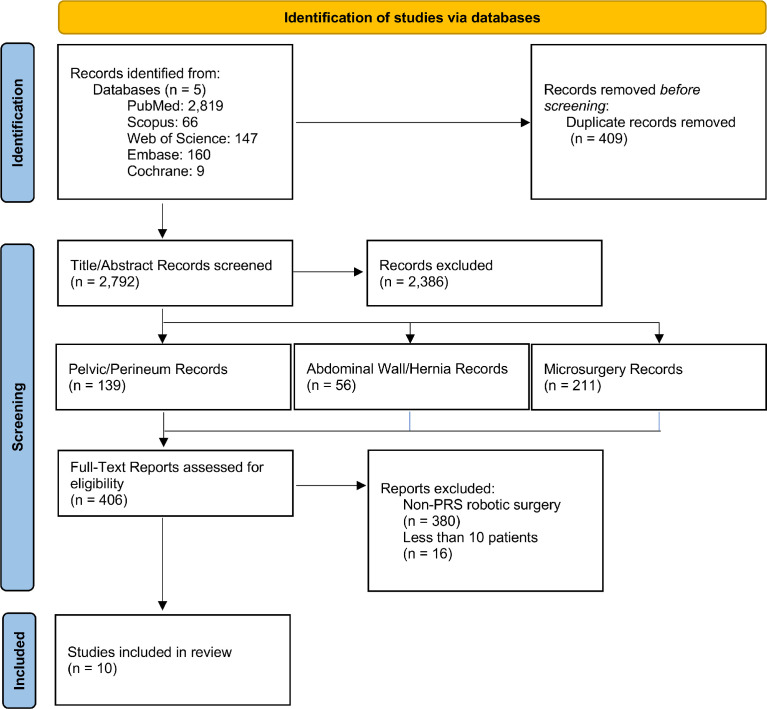

A total of 2,795 studies were initially found on database queries with 409 duplicates. After screening, 406 papers were eligible for full-text review and ten for qualitative synthesis (Figure 5). Sixteen studies had less than 10 total patients and were excluded from formal analysis (Supplemental Table 1).9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24

Figure 5.

PRISMA diagram.

Abdominal Wall

Three studies met inclusion criteria (Table 1) with 53 studies being either case series/reports with n<10 (n=6) or non-PRS (n = 47). The average age at surgery was 53.2 years old. No studies reported the sex distribution. Two studies were comparative retrospective studies25,26, and the other was a case series.27

Outcomes

Shakir et al. (2021) compared endoscopic, laparoscopic, and robotic harvest of deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flaps for breast reconstruction.26 There were 135 patients in total: robotic (n=3), endoscopic (n=94), and total extraperitoneal laparoscopic (TEP-lap) (n=38). There were no instances of complications in the robotic and laparoscopic cohort, compared to two cases of flap loss in the endoscopic cohort. The average operative time was 535.3 min in the robotic cohort, compared to 344.0 min and 425.2 min in the endoscopic and laparoscopic cohorts, respectively.

Choi et al. (2021) compared the use of RAS versus traditional dissection of the vascular pedicle of the DIEP flap for breast reconstruction.25 Seventeen participants underwent robotic harvest compared to four who underwent traditional harvest. The average operative time was 65 min for robotic harvest with a total operative time of 487 min.

Pedersen et al. (2014) described the use of RAS for rectus abdominis harvest for extremity coverage and pelvic surgery.27 Ten patients underwent RAS with a mean follow-up of approximately 12 months. At one year follow-up, no patients had hernias or bulges. The average set-up and harvest time were 15 min and 45 min, respectively.

Microsurgery

A total of four studies met inclusion criteria (Table 2) with the remaining seven consisting of studies with n<10. Across all studies, n=211. The average age among the study groups was 50.2 years old. Two studies were retrospective,28,29 one was prospective,30 and one was a case series.31

Outcomes

Van Mulken et al. (2020) compared the use of RAS vs. traditional surgery for women with breast cancer-related lymphedema.30 They found that at three-month follow-up, 12.5% of patients in the robot group vs. 16.7% of patients in the traditional group used a daily compressive garment. However, they reported no significant differences in lymphedema indices across the two groups.

Boyd et al. (2006) studied RAS flap harvest and recorded harvest time (mean=113 min), ICU time (mean=2.95 days), chest tube time (mean=2.10), and admission days (mean=7.20).31 Complications included hematoma (n=6), flap loss (n=2), pneumothorax (n=1), MRSA pneumonia (n=1), minimal fat necrosis (n=1), and positional neuropraxia (n=2).

Lai et al. (2019) conducted a retrospective study of head and neck cancer patients to evaluate RAS microanastomosis.28 Compared to the standard technique, RAS microanastomosis had a significantly longer operating time. The donor blood vessel diameter in the robot group was significantly smaller than that in the traditional group. All flaps survived across both groups and neither group had any intraoperative complications.

McCullough et al. (2018) investigated robot-assisted varicocelectomy (RAMV) in men with sympathetic hypogonadism.29 The complication rate was 3.5% (9/258), and 9.7% of patients had persistence of symptoms. Their findings demonstrated no significant differences in operative time among the two groups when comparing their cohort with a historical and traditional varicocelectomy control group.

Pelvic and Perineum Reconstruction

A total of three studies met inclusion criteria with the remaining three consisting of studies with n<10 (Table 3). Across all studies, n=139. The average age among the study groups was 39.6 years. All three studies were retrospective.

Outcomes

Chong et al. (2015) compared the use of RAS (n=7) vs. traditional surgery (n=9) for abdominoperineal resection for pelvic/perineal cancers.32 Follow-up time ranged from 5 to 40 months. In the traditional surgery group, four patients had abdominal wound complications, and other patients had a major perineal complication. Minor perineal complications occurred in three patients, one in the RAS group and two in the traditional surgery group.

Dy et al. (2021) reported the use of RAS for peritoneal flap revision vaginoplasty.33 All 24 patients had undergone primary penile inversion vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty, with revision surgery occurring after an average of 35.3 months. Out of 24 patients, only 18 patients presented at a 6-month follow-up and were included in the analysis. The average operative time was 280 min, and the average length of stay was 5.1 days. At 6-month follow-up, a mean increase in vaginal depth and width was 6.9 cm and 1.0 cm, respectively. There were no complications related to peritoneal flap harvest.

Dy et al. (2021) compared the use of two types of robots, da Vinci Xi (Xi) vs. da Vinci Single Port (SP) robot, for peritoneal flap harvest for gender-affirming vaginoplasty.34 A total of 100 patients were included in the analysis, Xi = 47 and SP = 53, and followed up for a minimum of six months. The average operative time was 4.2 h in Xi cohort and 3.7 h in SP cohorts. Vaginal depth and width at 6-month follow-up were 13.6 and 3.7 cm in Xi and 14.1 and 3.7 cm in SP cohorts, respectively. Complications include transfusion (6%), rectovaginal fistula (1%), bowel obstruction (2%), pelvic abscess (1%), and vaginal stenosis (7%). SP robots significantly reduced operative times. However, the authors report that there was no difference in complication rates between two robotic approaches.

Discussion

Twenty years have passed since the first reported case of RAS. While many surgical specialties have embraced RAS,4, 5, 6 adoption by plastic surgeons has been slow. Presumptions regarding RAS are that the technology solely allows for increased visualization to areas of the body that are difficult to access without a large incision. As such, plastic surgery which has generally not been limited by incisions and access has perceived RAS as lacking in utility. However, the evidence found in this report are indicators that the belief in the utility of RAS is changing among plastic surgeons.

There is a paucity of large comparative studies evaluating RAS. Further, many studies failed to conduct significance testing, only presenting descriptive statistics, making it difficult to ascertain any true differences between the two groups. Nonetheless, there were reports of success with the use of RAS. RAS was used to harvest DIEP flap for breast reconstruction that had no flap loss or abdominal complications, whereas endoscopic harvest elicited two instances of flap loss.26 Three studies demonstrated no operative complications and flap survival in all patients at final follow-up;27,28,33 two of the three studies failed to compare outcomes with traditional cohorts.27,34 Lai et al. (2019) noted equal outcomes for both RAS and non-RAS, but also reported that the RAS group used significantly smaller vessels for microanastomosis than non-RAS.28 Similarly, another study demonstrated that RAS improved some lymphedema-related symptoms more than non-RAS following surgical intervention for breast cancer-related lymphedema.30

In terms of complications, RAS was found to have lower complication rates in comparison with non-RAS during abdominoperineal resection of pelvic/perineal cancers.32 Similarly, RAS had no flap loss compared with non-RAS in DIEP harvest.26 Other studies that reported on complications, unfortunately, did not provide a non-RAS comparator group, precluding analysis.27,31,33 One study instead compared two different robots, however, and did not find any differences in complication rates between the two groups.34 Although there have been limited studies on outcomes and complications, there appears to be a weakly positive tendency for RAS over non-RAS. More prospective randomized controlled trials are needed to support this postulation.

Cost considerations for RAS have been a topic of concern and interest since the technology's inception. Over half of the survey respondents cited cost and reimbursement as a preferred conference topic. Shakir et al. (2020) reported that the average disposable material cost of robotic harvest of DIEP flaps was $150026 compared to $500 and $250 in TEP-lap and endoscopic approaches, respectively. Another study included in Supplemental Table 1 found that traditional DIEP cost $14,800 and robotic DIEP cost $16,300.17 While only two studies reported costs associated with different approaches, it is clear that robotic surgery is more expensive. However, no studies performed a true cost-effectiveness or utility analysis. Cost-effectiveness has been studied for robotic surgery in other subspecialties with conclusions varying greatly depending on region, hospital, and institution being analyzed.35, 36, 37 With the market of robotic surgery soaring to $20 billion in 2021 from just $4 billion in 2014,38 the impetus for a PRS-focused cost-effectiveness analysis is difficult to comprehend.

As mentioned above, survey respondents expressed concern about increased operative times in RAS implementation. Our findings were inconclusive with regards to the effect of using RAS on operative time. One study reported no significant difference in the operative time between robot-assisted and traditional varicocelectomy.29 Dy et al. (2021) compared operative time between two different robots (Xi and SP), but did not compare operative time with traditional approaches, thus precluding analysis.34 Shakir et al. (2021) found that robotic operative time was longer than endoscopic and laparoscopic cohorts but did not evaluate for significant differences across the three groups.26 Finally, one study found that in head and neck RAS, the use of robots led to significantly greater operative times than traditional surgery. Unfortunately, there were limited studies reporting on this outcome measure, and thus further investigation is warranted to elucidate the impact of robot use on operative time.

The implementation of any technology requires adequate training. Current RAS training consists of online training modules, “dry” and “wet” simulation, bedside assists, and console surgery.39 In general surgery, there are no validated RAS curriculums, and existing programs are highly variable.40 Similar problems exist in other subspecialties such as urologic,41 thoracic,42 and gynecologic surgery.43 To our knowledge, there are no validated RAS curricula in any plastic surgery residency programs. Yet, among respondents in our survey, nearly 90% believed that RAS should be implemented into future surgical education and training. Additionally, over half believed that a major barrier to RAS was a lack of adequate training. This reflects a growing understanding of the applicability of RAS, as well as the shortcomings of current RAS training within plastic surgery. Such findings should serve as an indicator to program directors to advocate for RAS curriculum development.

One limitation of this study is the low survey response rate, and as such, does not adequately constitute a true national survey, despite representation from all US regions. Moreover, the majority of our respondents were located from the Southwestern USA, major metropolitan cities, and academic centers, making it difficult to accurately assess the spectrum of perspectives regarding RAS.

Conclusion

Evidence from our survey and systematic review supports the growing interest and utility of RAS within PRS and mirrors the established trend in other surgical subspecialties. Cost analyses will prove critical to implementing RAS within PRS and, as highlighted in our review, have not been published. With validated benefits, plastic surgery programs can begin creating dedicated curricula for RAS.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Funding Source

None.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable to this study.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure Statement: No financial disclosures relevant to this study.

Accepted Presentations: This manuscript has not been accepted/presented at any local, regional, or national conference.

Financial disclosure statement: The authors have no relevant financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this manuscript.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2022.05.006.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Meadows M. Robots lend a helping hand to surgeons. FDA Consum. 2002;36(3):10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballantyne GH. Robotic surgery, telerobotic surgery, telepresence, and telementoring. Surgical Endoscopy And Other Interventional Techniques. 2002;16(10):1389–1402. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobbs TD, Cundy O, Samarendra H, Khan K, Whitaker IS. A Systematic Review of the Role of Robotics in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery-From Inception to the Future. Front Surg. 2017;4:66. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2017.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Partin AW, Adams JB, Moore RG, Kavoussi LR. Complete robot-assisted laparoscopic urologic surgery: a preliminary report. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181(6):552–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cadière GB, Himpens J, Germay O, et al. Feasibility of robotic laparoscopic surgery: 146 cases. World J Surg. 2001;25(11):1467–1477. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kappert U, Cichon R, Schneider J, et al. Robotic coronary artery surgery–the evolution of a new minimally invasive approach in coronary artery surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;48(4):193–197. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-6904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz RD, Rosson GD, Taylor JA, Singh NK. Robotics in microsurgery: use of a surgical robot to perform a free flap in a pig. Microsurgery. 2005;25(7):566–569. doi: 10.1002/micr.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konofaos P, Hammond S, Ver Halen JP, Samant S. Reconstructive techniques in transoral robotic surgery for head and neck cancer: a North American survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(2):188e–197e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182778680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang TNJ, Chen LWY, Lee CP, Chang KH, Chuang DCC, Chao YK. Microsurgical robotic suturing of sural nerve graft for sympathetic nerve reconstruction: a technical feasibility study. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(2):97–104. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.08.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asaad M, Pisters LL, Klein GT, et al. Robotic Rectus Abdominis Muscle Flap following Robotic Extirpative Surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148(6):1377–1381. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000008592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sieffert M, Ouellette J, Johnson M, Hicks T, Hellan M. Novel technique of robotic extralevator abdominoperineal resection with gracilis flap closure. Int J Med Robot. 2017;13(3) doi: 10.1002/rcs.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haverland R, Rebecca AM, Hammond J, Yi J. A Case Series of Robot-assisted Rectus Abdominis Flap Harvest for Pelvic Reconstruction: A Single Institution Experience. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(2):245–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selber JC. Transoral robotic reconstruction of oropharyngeal defects: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(6):1978–1987. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f448e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh P, Teng E, Cannon LM, Bello BL, Song DH, Umanskiy K. Dynamic Article: Tandem Robotic Technique of Extralevator Abdominoperineal Excision and Rectus Abdominis Muscle Harvest for Immediate Closure of the Pelvic Floor Defect. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(9):885–891. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vigneswaran Y, Bryan AF, Ruhle B, Gottlieb LJ, Alverdy J. Autologous Posterior Rectus Sheath as a Vascularized Onlay Flap: a Novel Approach to Hiatal Hernia Repair. J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;26(1):268–274. doi: 10.1007/s11605-021-05134-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel NV, Pedersen JC. Robotic harvest of the rectus abdominis muscle: a preclinical investigation and case report. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2012;28(7):477–480. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1287674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gundlapalli VS, Ogunleye AA, Scott K, et al. Robotic-assisted deep inferior epigastric artery perforator flap abdominal harvest for breast reconstruction: A case report. Microsurgery. 2018;38(6):702–705. doi: 10.1002/micr.30297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Özkan Ö, Özkan Ö, Çinpolat A, Arıcı C, Bektaş G, Can Ubur M. Robotic harvesting of the omental flap: a case report and mini-review of the use of robots in reconstructive surgery. J Robot Surg. 2019;13(4):539–543. doi: 10.1007/s11701-019-00949-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Day SJ, Dy B, Nguyen MD. Robotic omental flap harvest for near-total anterior chest wall coverage: a potential application of robotic techniques in plastic and reconstructive surgery. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(2) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-237887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Facca S, Liverneaux P. Robotic assisted microsurgery in hypothenar hammer syndrome: a case report. Comput Aided Surg. 2010;15(4-6):110–114. doi: 10.3109/10929088.2010.507942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naito K, Imashimizu K, Nagura N, et al. Robot-assisted Intercostal Nerve Harvesting: A Technical Note about the First Case in Japan. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(6):e2888. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yilmaz MM, Uzun H, Gudeloglu A, Aksu AE. Robotic-assisted microsurgical penile replantation. Int J Impot Res. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41443-020-00359-7. Published online October 6, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teven CM, Yi J, Hammond JB, et al. Expanding the Horizon: Single-port Robotic Vascularized Omentum Lymphatic Transplant. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9(2):e3414. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang TNJ, Daniel BW, Hsu ATW, et al. Reversal of thoracic sympathectomy through robot-assisted microsurgical sympathetic trunk reconstruction with sural nerve graft and additional end-to-side coaptation of the intercostal nerves: A case report. Microsurgery. 2021;41(8):772–776. doi: 10.1002/micr.30787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi JH, Song SY, Park HS, et al. Robotic DIEP Flap Harvest through a Totally Extraperitoneal Approach Using a Single-Port Surgical Robotic System. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148(2):304–307. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000008181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shakir S, Spencer AB, Piper M, Kozak GM, Soriano IS, Kanchwala SK. Laparoscopy allows the harvest of the DIEP flap with shorter fascial incisions as compared to endoscopic harvest: A single surgeon retrospective cohort study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2021;74(6):1203–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2020.10.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen J, Song DH, Selber JC. Robotic, intraperitoneal harvest of the rectus abdominis muscle. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(5):1057–1063. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai CS, Lu CT, Liu SA, Tsai YC, Chen YW, IC Chen. Robot-assisted microvascular anastomosis in head and neck free flap reconstruction: Preliminary experiences and results. Microsurgery. 2019;39(8):715–720. doi: 10.1002/micr.30458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCullough A, Elebyjian L, Ellen J, Mechlin C. A retrospective review of single-institution outcomes with robotic-assisted microsurgical varicocelectomy. Asian J Androl. 2018;20(2):189–194. doi: 10.4103/aja.aja_45_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Mulken TJM, Schols RM, Scharmga AMJ, et al. First-in-human robotic supermicrosurgery using a dedicated microsurgical robot for treating breast cancer-related lymphedema: a randomized pilot trial. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):757. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14188-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyd B, Umansky J, Samson M, Boyd D, Stahl K. Robotic harvest of internal mammary vessels in breast reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2006;22(4):261–266. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chong TW, Balch GC, Kehoe SM, Margulis V, Saint-Cyr M. Reconstruction of Large Perineal and Pelvic Wounds Using Gracilis Muscle Flaps. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(11):3738–3744. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dy GW, Blasdel G, Shakir NA, Bluebond-Langner R, Zhao LC. Robotic Peritoneal Flap Revision of Gender Affirming Vaginoplasty: a Novel Technique for Treating Neovaginal Stenosis. Urology. 2021;154:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2021.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dy GW, Jun MS, Blasdel G, Bluebond-Langner R, Zhao LC. Outcomes of Gender Affirming Peritoneal Flap Vaginoplasty Using the Da Vinci Single Port Versus Xi Robotic Systems. Eur Urol. 2021;79(5):676–683. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia D, Akinduro OO, De Biase G, et al. Robotic-Assisted vs Nonrobotic-Assisted Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion: A Cost-Utility Analysis. Neurosurgery. 2022;90(2):192–198. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Oliveira RAR, Guimarães GC, Mourão TC, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of robotic-assisted versus retropubic radical prostatectomy: a single cancer center experience. J Robot Surg. 2021;15(6):859–868. doi: 10.1007/s11701-020-01179-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdelmoaty WF, Dunst CM, Neighorn C, Swanstrom LL, Hammill CW. Robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic unilateral inguinal hernia repair: a comprehensive cost analysis. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(10):3436–3443. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-06606-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byrd JK, Paquin R. Cost Considerations for Robotic Surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2020;53(6):1131–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2020.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao B, Lam J, Hollandsworth HM, et al. General surgery training in the era of robotic surgery: a qualitative analysis of perceptions from resident and attending surgeons. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(4):1712–1721. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-06954-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tom CM, Maciel JD, Korn A, et al. A survey of robotic surgery training curricula in general surgery residency programs: How close are we to a standardized curriculum? Am J Surg. 2019;217(2):256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang RS, Ambani SN. Robotic Surgery Training: Current Trends and Future Directions. Urol Clin North Am. 2021;48(1):137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2020.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raad WN, Ayub A, Huang CY, Guntman L, Rehmani SS, Bhora FY. Robotic Thoracic Surgery Training for Residency Programs: A Position Paper for an Educational Curriculum. Innovations. 2018;13(6):417–422. doi: 10.1097/IMI.0000000000000573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gobern JM, Novak CM, Lockrow EG. Survey of robotic surgery training in obstetrics and gynecology residency. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(6):755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.