Abstract

Background

The coronavirus 2019 pandemic placed unprecedented pressures on healthcare services and magnified ethical dilemmas related to how resources should be allocated. These resources include, among others, personal protective equipment, personnel, life-saving equipment, and vaccines. Decision-makers have therefore sought ethical decision-making tools so that resources are distributed both swiftly and equitably. To support the development of such a decision-making tool, a systematic review of the literature on relevant ethical values and principles was undertaken. The aim of this review was to identify ethical values and principles in the literature which relate to the equitable allocation of resources in response to an acute public health threat, such as a pandemic.

Methods

A rapid systematic review was conducted using MEDLINE, EMBASE, Google Scholar, LitCOVID and relevant reference lists. The time period of the search was January 2000 to 6th April 2020, and the search was restricted to human studies. January 2000 was selected as a start date as the aim was to capture ethical values and principles within acute public health threat situations. No restrictions were made with regard to language. Ethical values and principles were extracted and examined thematically.

Results

A total of 1,618 articles were identified. After screening and application of eligibility criteria, 169 papers were included in the thematic synthesis. The most commonly mentioned ethical values and principles were: Equity, reciprocity, transparency, justice, duty to care, liberty, utility, stewardship, trust and proportionality. In some cases, ethical principles were conflicting, for example, Protection of the Public from Harm and Liberty.

Conclusions

Allocation of resources in response to acute public health threats is challenging and must be simultaneously guided by many ethical principles and values. Ethical decision-making strategies and the prioritisation of different principles and values needs to be discussed with the public in order to prepare for future public health threats. An evidence-based tool to guide decision-makers in making difficult decisions is required. The equitable allocation of resources in response to an acute public health threat is challenging, and many ethical principles may be applied simultaneously. An evidence-based tool to support difficult decisions would be helpful to guide decision-makers.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12910-022-00806-8.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Pandemic, Emergencies, Ethics, Ethical principles, Ethical frameworks, Equity, Resource allocation, Healthcare resources

Background

The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic, otherwise known as the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, quickly overwhelmed the most sophisticated of healthcare systems, placing unprecedented pressure on healthcare services. The pandemic has also magnified many ethical issues related to the provision of appropriate standards of care, privacy and confidentiality, informed consent, community engagement, benefit-sharing and resource allocation [1].

Although such a pandemic has long been anticipated, with published recommendations for countries to use in their preparations [2, 3], many countries have struggled to allocate resources and apply control measures. As Thomas and colleagues noted, considering the ethics of a situation requires ethical reflection and discussion, skills that require preparation and practice [4].

In Ireland, as in many neighbouring European countries, the pandemic has forced a shift from person-centred healthcare provision to practices primarily guided by considerations on the well-being of the population as a whole [5]. Due to the overwhelming nature of the pandemic, with demand outstripping capacity in many countries it has been challenging to adhere to a ‘duty of care’ model and respond in an equitable, reasonable, and proportionate way. The published experience of many countries has shown that pandemics can be catastrophic on healthcare systems, decimating resources (i.e. protective equipment), and resulting in a shortage of personnel and life-saving equipment [6–11]. The available literature demonstrates that when faced with an increasing number of people requiring acute care, ethical decisions are required on the allocation of resources. Unique and challenging ethical issues have been raised as a direct result of COVID-19. These include prioritising access to healthcare resources, obligations of frontline workers considering the risk to their own and their families’ health, and the implementation of measures to reduce the spread of the infection while protecting the rights of the individual.

In this context, decision-makers are looking for ethical decision-making tools providing key knowledge-sharing opportunities and complimenting decisions on care provision and delivery, as swiftly—but proportionally and fairly, as possible. Decision-making tools are required, among other reasons, to promote transparency and maintain accountability with policy makers, to ensure collective justice and to encourage engagement with healthcare providers working on the front lines.

After the World Health Organisation (WHO) pronounced the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic in March 2020, and after the first cases of COVID-19 were reported in Ireland (in late February 2019), the National Rehabilitation Hospital (NRH) in Ireland, a complex specialist rehabilitation facility, established the COVID-response committee. The NRH provides complex specialist rehabilitation services to patients who, as a result of an accident, illness or Injury, have acquired a physical or cognitive disability and would therefore be considered vulnerable [12]. Decisions were rapidly taken to limit risks to staff and patients. It was recognised that such decisions had ethical dimensions, and in the absence of national guidance at that time, the matter was escalated to the Hospital Ethics Committee for consideration. The committee recognised that to support hospital management in its decision-making, they needed to be evidence-informed and requested that a rapid review of the literature be completed and presented to the committee. A research team was swiftly convened to conduct a rapid systematic review. The aim of the rapid systematic review was to identify ethical values and principles which related to the equitable allocation of resources in the context of an acute public health threat [13], such as a pandemic. The results of this rapid systematic review were used to support the development of an evidence-based ethical framework to provide guidance on the ethical allocation of resources. It is expected that such a framework would have applicability to a wide range of national and international healthcare settings.

Methods

Scope of the review

A rapid systematic review methodology was selected given the time-sensitive nature of this project. As described by Tricco and colleagues, ‘Rapid reviews are a form of knowledge synthesis in which the components of the systematic review process are simplified or omitted to produce information in a timely manner’ [14]. Rapid reviews have emerged as a streamlined approach to knowledge synthesis, usually to inform urgent decisions faced by decision-makers in a healthcare setting [15, 16]. Although the review team were required to respond to the time-sensitive needs of the ethics committee, they simultaneously had to ensure that the scientific imperative of methodological rigour was satisfied.

The research team consisted of a core team of three researchers who performed the database searching, screening and data extraction, and a broader steering group including a medical ethicist, an academic medical consultant and a clinical psychologist. This team set and refined the review question, eligibility criteria, and the outcomes of interest.

The review protocol was developed in line with the PICO evidence-based approach (Problem, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) which was used to frame the research question [17] as follows –

Problem In a context of acute resource limitations in healthcare system, how should limited resources be rationed or allocated fairly in the healthcare setting?

Intervention ethical values or principles to guide allocation of resources

Comparator not applicable for this review

Outcome maximise the protection of a person’s rights to healthcare, minimise the risk for treatment withdrawal based on unethical reasoning, and support for practitioners, administrators and managers making difficult decisions regarding resource allocation.

The protocol was published on the Open Science Framework and is available at https://osf.io/krgsn/

The review was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance and checklist [18]—see Additional File 1.

Search strategy

The search strategy was informed and refined with advice from an information specialist (health sciences liaison librarian). The search is described with reference to the PRISMA-S checklist [19]—see Additional File 2.

A comprehensive literature review search of multiple bibliographic databases including MEDLINE, EMBASE and Google Scholar was conducted. Google Scholar was selected as an effective tool to identify grey literature [20, 21]. A search of references lists of relevant systematic reviews, government and non-governmental organisation reports, opinion pieces, included articles and other relevant grey literature, including LitCOVID was also undertaken. National and International Ethical Frameworks already familiar to the authors were also included. References in identified articles were also reviewed (backwards citation screening).

The search terms used for the MEDLINE search within the title or abstract are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search terms used in MEDLINE

| Search string | Key words |

|---|---|

| 1 | (“Coronavirus” OR “COVID19” OR “epidemic” OR “outbreak” OR “pandemic” OR “humanitarian emergency” OR “catastrophes” OR “disaster”) |

| 2 | (“Resources” OR “Resource Allocation” OR “Rationing” OR “Shortage” OR “Personal Protective Equipment” “Ventilator” OR “Triage” OR “Withholding”) |

| 3 | (“Ethics” OR “Morality” OR “Ethical framework” OR “Health equity” OR “Decision making”) |

| 4 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 |

| 5 | Limit Jan 2000 to 6th April 2020 |

A list of the EMTREE (EMBASE) search terms can be found in Additional File 3. No limits with regard to language were applied.

For MEDLINE and EMBASE, the following limits were applied:

Human studies

Time period January 2000 to 6th April 2020

Within Google Scholar, the search was performed in incognito mode—this ensures that any previous searches will not influence Google’s algorithm when searching for new material/ The first 200 entries were included, as recommended by Haddaway and colleagues [20].

All identified papers were exported to Zotero, and duplicates excluded. All remaining papers were imported to Rayaan for review [22]. Two members of the team (LOS and AOB) independently and blindly screened Titles and Abstracts of all papers in accordance with the Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria detailed below. Additionally, the scope of this rapid review was limited to public health threats, such as pandemics. For this reason, disasters such as plane crashes or hurricane aftermath, where the triage of casualties would be required, were excluded.

Study selection

Title/abstract screening

Articles were included if they met the following Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria.

Inclusion Criteria—selected papers including at least two of the following three concepts:

Acute Resource Limitation or similar

Rationing / Allocation / Decision-making or similar

Ethical perspective

Exclusion Criteria—papers with no abstract or with a focus on the following were excluded:

Accident and Emergency Services

In-flight emergencies

Clinical research taking place during humanitarian emergencies

Ethics in clinical research

Communication strategies

Informed consent

Other clinical emergencies which are not outbreaks/disasters/pandemics

Once Title/Abstract screening was complete, a third member of the research team (EA) resolved any conflicts.

Authors of individual papers were not contacted to collect additional information or to request the full text of inaccessible papers, due to time constraints.

Full text screening

All three team members (EA, LOS, AOB) each reviewed a portion of the full texts. Papers were excluded if:

The full text was not available

They did not contain principles or values relevant to an ethical framework which could be used to support decision-making about the allocation of resources

The topic related solely to triage procedures in pandemics/disasters e.g., operational medical or nursing triage procedures

The topic related to legal aspects, rather than ethical ones

They contained only a clinical case study/case studies i.e., summary of a patient or patients’ clinical condition and outcome

They only gave a brief summary of the main ethical approaches, with no further details

The topic related only to pandemic planning

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction was completed by all three reviewers using a customised data extraction form in Microsoft Excel, all three checked for correctness and completeness of extracted data, and one researcher synthesised all data extractions. The following data items were extracted:

Lead author

Year of publication

Ethical values or principles relevant to an ethical framework

Synonyms of the named ethical value or principle

Related ethical values or principles

Example(s) of a scenario where the ethical values or principles apply

The aim of this rapid systematic review was to identify ethical values and principles, rather than quantitatively assess healthcare interventions or to assess the methodological quality of clinical trials. Therefore, the articles were assessed, and the extracted themes were synthesised, and no risk of bias assessment was performed. Emphasis was placed on high-quality literature and also key publications identified by the key stakeholders—these included peer-reviewed literature, government reports or publications produced by reputable organisations. Due to differences in nomenclature used in the literature, both the terms ‘ethical value’ and ‘ethical principle’ are used to describe the findings.

Results

Article inclusion

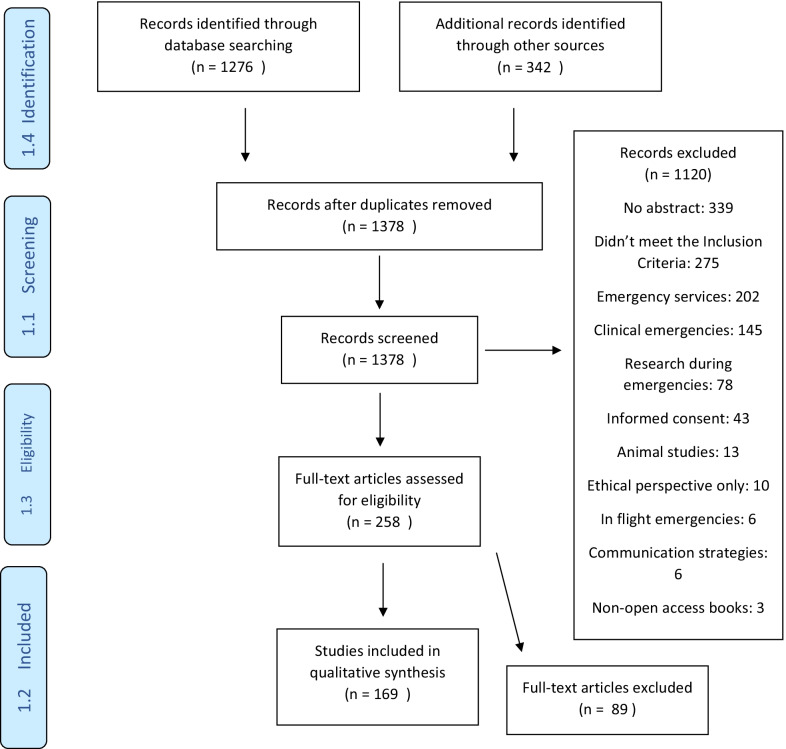

A PRISMA flow diagram of the evidence identified by this rapid review is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the evidence identified by this rapid review

A total of 1276 articles were obtained from the electronic search of international databases, and an additional 342 articles were identified through other sources. After screening and application of eligibility criteria, 169 papers were included in the thematic synthesis.

Characteristics of included articles

The main types of articles included in the full text review were policy papers, e.g. [23–25], discussion papers, e.g. [26, 27], ethical debates, e.g. [28–30] or case studies from previous disaster situations, e.g. [31–33]. Several articles were publications from national or local governments, such as departments of health [5, 34–40].

Ethical values and principles

31 ethical values and principles were identified from the 169 full text articles. Table 2 summarises the ethical principles and values identified. For brevity, only the most recent references are included, but the full list of references is included in Additional File 4. Equity, reciprocity, transparency, justice, duty to care, liberty, utility, stewardship, trust and proportionality were the most common values and principles identified. These values and principles were applied to a wide range of scenarios, including terrorism [41, 42], vaccination distribution [43–45] and quarantine measures such as lockdowns [24, 46–48].

Table 2.

Ethical values and principles extracted from included studies

| 1 | Equity [43] | Fairness [14] | 49 | British Medical Association, 2020 [90] |

| Equality [4] | Chisholm, 2020 [91] | |||

| Antidiscrimination, Non-discriminatory [3] | ||||

| Fair distribution [1] | ||||

| Legitimacy [1] | ||||

| Justice as fairness [1] | ||||

| 2 | Reciprocity [24] | Mutual exchange [1] | 24 | Berlinger, 2020 [92] |

| Society and employers should support and protect | British Medical Association, 2020 [90] | |||

| those who take on increased burden and risk [4] | ||||

| Support for those enduring a disproportionate burden during crisis and address/minimise burden [1] | ||||

| Obligations to healthcare workers [1] | ||||

| Justice-orientated reciprocity [1] | ||||

| 3 | Transparency [19] | Openness and public accessibility [2] | 21 | British Medical Association, 2020 [90] |

| Communication [2] | Scottish Government, 2020 [93] | |||

| Publicly defensible [1] | ||||

| Justification [1] | ||||

| Veracity [1] | ||||

| 4 | (Social) (Distributive) Justice [17] | Justice as fairness [1] | 18 | White, 2020 [94] |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019 [95] | ||||

| 5 | Duty to (provide) care [14] | Professional obligation of non-abandonment [1] | 18 | Department of Health Ireland, 2020 [96] |

| Professional duty to respond [1] | Gostin, 2020 [97] | |||

| Professional responsibility 1] | ||||

| Duty to treat [1] | ||||

| The obligation of healthcare workers to serve under stressful and risky conditions [1] | ||||

| Professional integrity [1] | ||||

| 6 | Individual Liberty [10] | Liberty [4] | 18 | Gostin, 2020 [97] |

| Least restrictive [3] | White 2020 [94] | |||

| Autonomy [2] | ||||

| Constraints on / restrictions of liberty [3] | ||||

| Individual autonomy [1] | ||||

| Equal liberty and human rights [1] | ||||

| Patient autonomy [1] | ||||

| Patient liberty [1] | ||||

| Choice, Free-will, Self-determination [1] | ||||

| 7 | Utility [9] | Efficiency [1] | 10 | Emanuel, 2020 [53] |

| Effectiveness [1] | Ram-Tiktin [31], 2017 | |||

| Greatest good for the greatest number [1] | ||||

| Utilitarian value [1] | ||||

| 8 | Stewardship [11] | Governance [1] | 13 | Ryus, 2018 [12] |

| Duty to steward resources [1] | Ra-Tiktin, 2017 [31] | |||

| 9 | Trust [9] | Informed and trusted communication [1] | 12 | Gostin, 2020 [97] |

| Fidelity [1] | Eyal, 2012 [98] | |||

| Honouring Patients’ Trust [1] | ||||

| 10 | Proportionality [9] | Fair procedures [1] | 10 | Alberta Government, 2016 [99] |

| Mariaselvam, 2016 [100] | ||||

| 11 | Accountability [8] | 8 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019 [95] | |

| Ryus, 2018 [101] | ||||

| 12 | Privacy [5] | 5 | Department of Health, Ireland, 2020 [96] | |

| Barnett, 2009 [102] | ||||

| 13 | Beneficence [4] | Avoid harm, harm reduction, minimising harm [4] | 9 | Gostin, 2020 [97] |

| Nonmaleficence [1] | British Medical Association, 2020 [90] | |||

| 14 | Protection of the Public from Harm [4] | Good preparedness [1] | 6 | Gostin, 2020 [97] |

| Protection of individuals at highest risk, meeting societal needs, and promoting social justice [1] | Mariaselvam, 2016 [100] | |||

| Ensuring that benefits of relief and rescue activities reach the affected [1] | ||||

| 15 | Autonomy [4] | 4 | Kukora 2016 [103] | |

| Kirby, 2010 [104] | ||||

| 16 | Solidarity [3] | Mutual responsibility [1] | 4 | Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics, 2020 [105] |

| Silva, 2012 [67] | ||||

| 17 | Working together [3] | 3 | British Medical Association, 2020 [90] | |

| Scottish Government, 2020 [93] | ||||

| 18 | Community participation [2] | Community resilience and empowerment [1] | 4 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019 [95] |

| Obligations to community [1] | Mariaselvam, 2016 [100] | |||

| 19 | Responsiveness [2] | Responsiveness to local values [1] | 3 | Mariaselvam, 2016 [100] |

| Trotter, 2010 [106] | ||||

| 20 | Consistency [2] | 2 | Ryus, 2018 [101] | |

| Hick, 2012 [107] | ||||

| 21 | Duty to Plan [1] | Flexibility and adaptability [1] | 2 | British Medical Association, 2020 [90] |

| Ryus, 2018 [101] | ||||

| 22 | Evidence [1] | 1 | Barnett, 2009 [102] | |

| 23 | Others: related to Social-Community | Respect [2] | (*) | |

| Social cohesiveness and collaboration [1] | ||||

| Responsive civic response [1] | ||||

| Dignity [1] | ||||

| Compassion [1] | ||||

| 24 | Others: related to decision-making processes | Reasonableness [1] | (*) | |

| Inclusiveness [1] | ||||

| Sustainability (sustainable action and sustainable outcomes) [1] | ||||

| Relevance [1] |

(*) The most recent references presented in the table. For full reference list of each entry see Additional File 4

It was noted that while some ethical principles were complimentary, e.g., solidarity, social cohesiveness and collaboration, others were potentially in conflict, e.g., liberty/autonomy, and protection of the public from harm. Another example of conflicting ethical principles related to the duty to provide care and reciprocity as healthcare and other frontline workers can be exposed to additional risks while performing their duties in disaster situations.

While there was broad agreement within the included studies regarding the importance of applying the principles of fairness, trust, equity etc., there was some discordance regarding the application of a utilitarian versus an egalitarian perspective [49]. While most authors did not espouse the utilitarian approach, a small number felt that this principle should apply in disaster situations in deciding how resources should be distributed [31, 50–54]. Others felt that utilitarianism should be combined with the principle of fairness, rather than applied in isolation [49, 55].

Several authors noted that the principle of reciprocity might apply to key workers, e.g., healthcare or frontline workers who are at the greatest risk and whose role is crucial to resolving the disaster situation [56–60]. Several studies referred to the ethical values and dilemmas for healthcare professionals arising from their willingness to work in situations of personal danger [61–64].

Several authors emphasised the importance of taking a pre-planned, objective, structured approach when allocating resources, to ensure fairness [5, 65, 66]. Other authors emphasised the importance of public consultation regarding ethical values in a disaster situation, in order to maintain public trust [32, 67–76], bearing in mind that ethical values will vary depending on the local culture [77].

Some authors specifically noted the importance of considering marginalised populations who may have difficulties accessing healthcare [78–80]. Similarly, several authors noted the importance of social justice, for example, with regard to the fair distribution of vaccines globally [44, 45].

Discussion

Summary of key findings

The most frequently cited ethical values and principles included equity, reciprocity, transparency, justice, duty to care, liberty, utility, stewardship, trust, and proportionality. It was also noted that in some cases, there may be a conflict between values and principles—e.g., between liberty/autonomy and protection of the public from harm. The importance of a pre-planned, structured approach, informed by public consultation was evident, as well as the inclusion of marginalised populations and countries with fewer resources.

Application of the principle of equity and social justice

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed a range of social inequalities from crowded living conditions, barriers to accessing healthcare and COVID-19 testing, lower-paid workers having higher rates of exposure, higher rates of transmission of infection for those using public transport, or with public-facing jobs [81, 82]. Currently, developed countries are purchasing stocks of vaccines and have begun vaccination programmes, while developing countries are likely to fall further behind. Even within developed countries, diverse groups are staking their claim to receive the vaccine as a priority and difficult decisions have to be made regarding prioritisation [83]. This demonstrates the importance of employing decision-making tools firmly based on ethical principles and values. It is also evident that lower-income countries, with lesser resources, may face even more difficult decisions with regard to the allocation of resources. It is also important to note that ethical values and principles will vary from culture to culture, emphasising the importance of local engagement.

Considerations for future research

The importance of incorporating ethical decision-making into pandemic planning was highlighted during the previous Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak [84]. During this outbreak, ethical issues were predominantly raised by public health, governments and healthcare workers as opposed to logistical and scientific issues [85, 86]. Furthermore, the absence of clear ethical guidelines during the SARS pandemic resulted in the loss of public trust, low morale amongst healthcare workers, confusion regarding roles and responsibilities, stigmatisation of vulnerable individuals, communities, misinformation and public fear [87].

Ethics contributes minimally to the understanding and mechanism of COVID-19 virus transmission. However, it significantly informs the decision-making process in relation to best clinical practice, the level of harm the public are expected and prepared to accept, how the burden of negative outcomes for specific populations should be addressed and if investment in additional resources is required. It is beyond the scope of this rapid review to discuss the application of each of these ethical principles and values; co-production with relevant stakeholders is needed within individual contexts. However, this rapid systematic review was used to support the development of an evidence-based ethical framework to provide guidance on an ethical process for decision-making on substantive clinical issues, incorporating evidence-based ethical values and thereby potentially mitigating unintended and avoidable collateral damage from COVID-19.

Strengths and limitations

The main advantage of using the rapid systematic review approach is the speed with which evidence can be synthesised. This can provide decision-makers with evidence to inform action, which is particularly important in a pandemic or disaster situation [88]. By incorporating two of the commonly used databases (MEDLINE and EMBASE), in addition to Google Scholar and assessment of grey literature, without language restrictions, a comprehensive review of the literature was completed. However, streamlining the systematic review process, e.g., only a single researcher performing each data extraction, may have introduced some level of bias [89]. There are also limitations associated with using Google Scholar, such as difficulties with reproducibility. As with any rapid review, a balance was sought between rigour and speed. It is also acknowledged that there was also a certain level of linguistic subjectivity associated with the categorization of ethical principles and values identified in this review, and that this a limitation.

Conclusions

Allocation of resources during a pandemic is a complex task, fraught with ethical dilemmas. It is crucial that decision-making in a pandemic is based on the principles of social justice regarding the allocation of resources. This systematic review identifies widely used and valued ethical principles which could be used to inform an ethical framework to support difficult decisions in a time of crisis.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 4. Full reference list of included papers.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to Mr Diarmuid Stokes, Liaison librarian, College of Health and Agricultural Science, University College Dublin for his assistance with informing and refining the search strategy.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- EMBASE

Excerpta Medica database

- MEDLINE

Medical literature analysis and retrieval system online

- NRH

National Rehabilitation Hospital

- PICO

Population; intervention; comparator; outcome

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- WHO

World Health Organisation

Author contributions

CMcG and AC conceptualised the review. CMcG, AC and MN provided substantial input into the design of the review. AC acquired the funding for the project. LOS, EA and AOB designed the search strategy, undertook the search and summarised the findings. All authors contributed to the writing and review of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

This project was funded by the National Rehabilitation Hospital. The design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript was conducted independently of the funder.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable—manuscript does not report on or involve the use of any animal or human data or tissue.

Consent for publication

Not applicable—manuscript does not contain data from any individual person.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Guidance for research ethics committees for rapid review of research during public health emergencies. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2020.

- 2.WHO global influenza preparedness plan: the role of WHO and recommendations for national measures before and during pandemics. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005.

- 3.WHO checklist for influenza pandemic preparedness planning. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005

- 4.Thomas JC, Dasgupta N, Martinot A. Ethics in a pandemic: a survey of the state pandemic influenza plans. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(Supplement_1):S26–S31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.093443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ann Roinn Slainte DoH. Ethical Framewrok for Decision-Making in a Pandemic27th March 2020.

- 6.Vergano M, Bertolini G, Giannini A, Gristina GR, Livigni S, Mistraletti G, et al. Clinical ethics recommendations for the allocation of intensive care treatments in exceptional, resource-limited circumstances: the Italian perspective during the COVID-19 epidemic. Berlin: Springer; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mounk Y. The extraordinary decisions facing Italian doctors. The Atlantic. 2020;11.

- 8.Kuhn A. How a South Korean city is changing tactics to tamp down its COVID-19 surge. NPR 2020;10.

- 9.Campbell D, Busby M. Not fit for purpose’: UK medics condemn Covid-19 protection. The Guardian 2020;16.

- 10.Craxì L, Vergano M, Savulescu J, Wilkinson D. Rationing in a pandemic: lessons from Italy. Asian Bioethics Rev. 2020;12:325–330. doi: 10.1007/s41649-020-00127-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinxten W, Denier Y, Dooms M, Cassiman J-J, Dierickx K. A fair share for the orphans: ethical guidelines for a fair distribution of resources within the bounds of the 10-year-old European Orphan Drug Regulation. J Med Ethics. 2012;38(3):148. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurst SA. Vulnerability in research and health care; describing the elephant in the room? Bioethics. 2008;22(4):191–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Public Health Threats: European Medicines Agency; Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats.

- 14.Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):224. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tricco AC, Langlois E, Straus SE, Organization WH. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garritty C, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, King VJ, Hamel C, Kamel C, et al. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;130:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller SA, Forrest JL. Enhancing your practice through evidence-based decision making: PICO, learning how to ask good questions. J Evid Based Dental Pract. 2001;1(2):136–141. doi: 10.1016/S1532-3382(01)70024-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, Ayala AP, Moher D, Page MJ, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, Kirk S. The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0138237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bramer WM, Giustini D, Kramer BMR. Comparing the coverage, recall, and precision of searches for 120 systematic reviews in Embase, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar: a prospective study. Syst Rev. 2016;5:39. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berlinger N, Wynia M, Powell T, Hester DM, Milliken A, Fabi R, et al. Managing uncertainty, safeguarding communities. Guid Pract 2020:12.

- 24.Schröder P, Brand H, Schröter M, Brand A. Ethical discussion on criteria for policy makers in public health authorities for preventative measures against a pandemic caused by a novel influenza A virus. Gesundheitswesen Bundesverband Der Arzte Des Offentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes (Germany)) 2007;69(6):371–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-981675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minnesota Crisis Standards of Care Framework: Ethical Guidance2020 2020.

- 26.Domres B, Koch M, Manger A, Becker HD. Ethics and triage. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2001;16(1):53–58. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X00025590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuschner WG, Pollard JB, Ezeji-Okoye SC. Ethical triage and scarce resource allocation during public health emergencies: tenets and procedures. Hosp Top. 2007;85(3):16–25. doi: 10.3200/HTPS.85.3.16-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Good L. Ethical decision making in disaster triage. J Emerg Nurs. 2008;34(2):112–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tännsjö T. Ethical aspects of triage in mass casualty. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007;20(2):143–146. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3280895aa3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kipnis K. Overwhelming casualties: medical ethics in a time of terror. Account Res. 2003;10(1):57–68. doi: 10.1080/08989620300504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ram-Tiktin E. Ethical considerations of triage following natural disasters: the IDF experience in Haiti as a case study. Bioethics. 2017;31(6):467–475. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kass NE, Otto J, O'Brien D, Minson M. Ethics and severe pandemic influenza: maintaining essential functions through a fair and considered response. Biosecur Bioterror. 2008;6(3):227–236. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2008.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strous RD, Gold A. Ethical lessons learned and to be learned from mass casualty events by terrorism. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2019;32(2):174–8. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health Ethics Considerations: Planning for and Responding to Pandemic Influenza in Missouri.

- 35.Powell T, Christ KC, Birkhead GS. Allocation of ventilators in a public health disaster. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2(1):20–26. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181620794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Devereaux AV, Dichter JR, Christian MD, Dubler NN, Sandrock CE, Hick JL, et al. Definitive care for the critically ill during a disaster: a framework for allocation of scarce resources in mass critical care: from a Task Force for Mass Critical Care summit meeting, January 26–27, 2007, Chicago, IL. Chest. 2008;133(5):51S–66S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daugherty Biddison EL, Faden R, Gwon HS, Mareiniss DP, Regenberg AC, Schoch-Spana M, et al. Too many patients—a framework to guide statewide allocation of scarce mechanical ventilation during disasters. Chest. 2019;155(4):848–854. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laar A, DeBruin D. Ethics-sensitivity of the Ghana national integrated strategic response plan for pandemic influenza. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:30. doi: 10.1186/s12910-015-0025-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kinlaw K, Barrett DH, Levine RJ. Ethical guidelines in pandemic influenza: recommendations of the Ethics Subcommittee of the Advisory Committee of the Director, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009;3:S185–S192. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181ac194f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levin D, Cadigan RO, Biddinger PD, Condon S, Koh HK, Group JMDoPH-HASoCW Altered standards of care during an influenza pandemic: identifying ethical, legal, and practical principles to guide decision making. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness. 2009;3:132–40. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181ac3dd2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iserson KV, Pesik N. Ethical resource distribution after biological, chemical, or radiological terrorism. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2003;12(4):455–465. doi: 10.1017/S0963180103124164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baker MS. Creating order from chaos: part I: triage, initial care, and tactical considerations in mass casualty and disaster response. Mil Med. 2007;172(3):232–236. doi: 10.7205/MILMED.172.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McLachlan HV. On the random distribution of scarce doses of vaccine in response to the threat of an influenza pandemic: a response to Wardrope. J Med Ethics. 2015;41(2):191–194. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2013-101516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wynia MK. Ethics and public health emergencies: rationing vaccines. Am J Bioethics. 2006;6(6):4–7. doi: 10.1080/15265160601021256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grotto I, Levine H, Balicer RD. Pandemic influenza vaccines: from the lab to ethical policy making. Harefuah. 2009;148(10):672–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gostin LO, Moon S, Meier BM. Reimagining global health governance in the age of COVID-19. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:1615–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McLean MM. Ethical preparedness for pandemic influenza: a toolkit. 2012.

- 48.Torda A. Ethical issues in pandemic planning. Med J Aust. 2006;185:S73–S76. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caro JJ, DeRenzo EG, Coleman CN, Weinstock DM, Knebel AR. Resource allocation after a nuclear detonation incident: unaltered standards of ethical decision making. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011;5:S46–53. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2011.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner JM, Dahnke MD. Nursing ethics and disaster triage: applying utilitarian ethical theory. J Emerg Nurs. 2015;41(4):300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moodley K, Hardie K, Selgelid MJ, Waldman RJ, Strebel P, Rees H, et al. Ethical considerations for vaccination programmes in acute humanitarian emergencies. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(4):290–297. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.113480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garrett JE, Vawter DE, Prehn AW, DeBruin DA, Gervais KG. Ethical considerations in pandemic influenza planning. Minn Med. 2008;91(4):37–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, et al. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.A 6-step ethical framework for COVID-19 care. Big Think. 2020.

- 55.Winsor S, Bensimon CM, Sibbald R, Anstey K, Chidwick P, Coughlin K, et al. Identifying prioritization criteria to supplement critical care triage protocols for the allocation of ventilators during a pandemic influenza. Healthc Q. 2014;17(2):44–51. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2014.23833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Satalkar P, Elger BE, Shaw DM. Prioritising healthcare workers for ebola treatment: treating those at greatest risk to confer greatest benefit. Dev World Bioeth. 2015;15(2):59–67. doi: 10.1111/dewb.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McLachlan HV. A proposed non-consequentialist policy for the ethical distribution of scarce vaccination in the face of an influenza pandemic. J Med Ethics. 2012;38(5):317–318. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Talbot TR, Babcock H, Caplan AL, Cotton D, Maragakis LL, Poland GA, et al. Revised SHEA position paper: influenza vaccination of healthcare personnel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(10):987–95. doi: 10.1086/656558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.A.K. W. Triage for the 2009 human swine influenza pandemic in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2010;17(4):413–4.

- 60.Bailey TM, Haines C, Rosychuk RJ, Marrie TJ, Yonge O, Lake R, et al. Public engagement on ethical principles in allocating scarce resources during an influenza pandemic. Vaccine. 2011;29(17):3111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wynia MK. Ethics and public health emergencies: encouraging responsibility. Am J Bioeth. 2007;7(4):1–4. doi: 10.1080/15265160701307613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barr HL, Macfarlane JT, Macgregor O, Foxwell R, Buswell V, Lim WS. Ethical planning for an influenza pandemic. Clin Med. 2008;8(1):49–52. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.8-1-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rottman SJ, Shoaf KI, Schlesinger J, Klein Selski E, Perman J, Lamb K, et al. Pandemic influenza triage in the clinical setting. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2010;25(2):99–104. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X00007792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levin PJ, Gebbie EN, Qureshi K. Can the health-care system meet the challenge of pandemic flu? Planning, ethical, and workforce considerations. Public Health Reports (Washington, DC: 1974). 2007;122(5):573–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Pena ME, Irvin CB, Takla RB. Ethical considerations for emergency care providers during pandemic influenza—ready or not. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24(2):115–9. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X00006646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gomersall CD, Loo S, Joynt GM, Taylor BL. Pandemic preparedness. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13(6):742–747. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f1bafd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Silva DS, Gibson JL, Robertson A, Bensimon CM, Sahni S, Maunula L, et al. Priority setting of ICU resources in an influenza pandemic: a qualitative study of the Canadian public's perspectives. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:241. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nicoli F, Gasparetto A. Italy in a time of emergency and scarce resources: the need for embedding ethical reflection in social and clinical settings. J Clin Ethics. 2020;31(1):92–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bhatia P. The H1N1 influenza pandemic: need for solutions to ethical problems. Indian J Med Ethics. 2013;10(4):259–263. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2013.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Daugherty Biddison EL, Gwon H, Schoch-Spana M, Cavalier R, White DB, Dawson T, et al. The community speaks: understanding ethical values in allocation of scarce lifesaving resources during disasters. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(5):777–783. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-379OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheung W, Myburgh J, McGuinness S, Chalmers D, Parke R, Blyth F, et al. A cross-sectional survey of Australian and New Zealand public opinion on methods totriage intensive care patients in an influenza pandemic. Crit Care Resusc J Australas Acad Crit Care Med. 2017;19(3):254–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fortes PAC, Zoboli ELCP. A study on the ethics of microallocation of scarce resources in health care. J Med Ethics. 2002;28(4):266–9. doi: 10.1136/jme.28.4.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fortes PAC. To choose who should live: a bioethical study of social criteria to microallocation of health care resources in medical emergencies (1992) Revista Da Associacao Medica Brasileira. 2002;48(2):129–34. doi: 10.1590/S0104-42302002000200031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.DeCoster B. Avian influenza and the failure of public rationing discussions. J Law Med Ethics J Am Soc Law Med Ethics. 2006;34(3):620–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2006.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pablo Beca J, Salas SP. Ethical and health issues posed by the recent Ebola epidemic: What should we learn? Rev Med Chil. 2016;144(3):371–376. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872016000300013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dreweck C, Graf P. The City of Munich's preparations for an influenza pandemic. Gesundheitswesen (Bundesverband Der Arzte Des Offentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes (Germany)) 2007;69(8):470–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bennett B, Carney T. Law, ethics and pandemic preparedness: the importance of cross-jurisdictional and cross-cultural perspectives. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010;34(2):106–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Silva DS, Nie JX, Rossiter K, Sahni S, Upshur REG, Pandemic CPoRoEia Contextualizing ethics: ventilators, H1N1 and marginalized populations. Healthc Q. 2010;13(1):32–6. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2013.21613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaposy C, Bandrauk N. Prioritizing vaccine access for vulnerable but stigmatized groups. Public Health Ethics. 2012;5(3):283–95. doi: 10.1093/phe/phs010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rosoff PM, DeCamp M. Preparing for an influenza pandemic: are some people more equal than others? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(3):19–35. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J, Matthews F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74(11):964–968. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rimmer A. Covid-19: Tackling health inequalities is more urgent than ever, says new alliance. BMJ. 2020;371:m4134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.COVID-19 Virtual Press conference [press release]. World Health Organisation, 2021.

- 84.Pena ME, Irvin CB, Takla RB. Ethical considerations for emergency care providers during pandemic Influenza-Ready or Not…. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24(2):115–119. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X00006646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bernstein M, Hawryluck L. Challenging beliefs and ethical concepts: the collateral damage of SARS. Crit Care. 2003;7(4):1–3. doi: 10.1186/cc2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Singer PA, Benatar SR, Bernstein M, Daar AS, Dickens BM, MacRae SK, et al. Ethics and SARS: lessons from Toronto. BMJ. 2003;327(7427):1342–1344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7427.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Upshur R, Faith K, Gibson J, Thompson A, Tracy C, Wilson K, et al. Ethical considerations for preparedness planning for pandemic influenza. A report of the University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics Pandemic Influenza Working Group. 2005.

- 88.Schünemann HJ, Moja L. Reviews: Rapid! Rapid! Rapid! …and systematic. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):4. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hamel C, Michaud A, Thuku M, Skidmore B, Stevens A, Nussbaumer-Streit B, et al. Defining Rapid Reviews: a systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;129:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.COVID-19: ethical issues. The British Medical Association is the trade union and professional body for doctors in the UK. 2020.

- 91.Chisholm J. Doctors will have to choose who gets life-saving treatment. Here's how we'll do it | John Chisholm 2020; 2020.

- 92.Ethical Framework for Health Care Institutions & Guidelines for Institutional Ethics Services Responding to the Coronavirus Pandemic. The Hastings Center. 2020.

- 93.Coronavirus (COVID-19): ethical advice and support framework: Scottish Government; 2020 Available from: https://www.gov.scot/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-ethical-advice-and-support-framework.

- 94.White DB, Lo B. A framework for rationing ventilators and critical care beds during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1773–1774. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.CDC - ACD Ethics Subcommittee Documents - OSI - OS. 2019: Centers for Disease Prevention and Control; 2019. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/os/integrity/phethics/ESdocuments.htm.

- 96.Gov.ie - Ireland's response to COVID-19 (Coronavirus). 2020.

- 97.Gostin LO, Friedman EA, Wetter SA. Responding to Covid-19: how to navigate a public health emergency legally and ethically. Hastings Cent Rep. 2020;50(2):8–12. doi: 10.1002/hast.1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.N. E, P. F. Repeat triage in disaster relief: questions from Haiti. PLoS Curr 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.Alberta's Ethical Framework for Responding to Pandemic Influenza. 2016:15.

- 100.Mariaselvam S, Gopichandran V. The Chennai floods of 2015: urgent need for ethical disaster management guidelines. Indian J Med Ethics. 2016;1(2):91–95. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2016.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ryus C, Baruch J. The duty of mind: ethical capacity in a time of crisis. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2018;12(5):657–662. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2017.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Barnett DJ, Taylor HA, Hodge JG, Links JM. Resource allocation on the frontlines of public health preparedness and response: report of a summit on legal and ethical issues. Public Health Rep (Washington, DC: 1974) 2009;124(2):295–303. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kukora S, Laventhal N. Choosing wisely: Should past medical decisions impact the allocation of scarce ECMO resources? Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr. 2016;105(8):876–8. doi: 10.1111/apa.13457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kirby J. Enhancing the fairness of pandemic critical care triage. J Med Ethics. 2010;36(12):758–761. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.035501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Overview: Ethical Concerns in Responding to Coronavirus: Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics; 2020. Available from: https://bioethics.jhu.edu/news-events/news/coronavirus-ethical-concerns-in-planning-a-response/.

- 106.Trotter G. Sufficiency of care in disasters: ventilation, ventilator triage, and the misconception of guideline-driven treatment. J Clin Ethics. 2010;21(4):294–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hick JL, DeVries AS, Fink-Kocken P, Braun JE, Marchetti J. Allocating resources during a crisis: you can't always get what you want. Minn Med. 2012;95(4):46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 4. Full reference list of included papers.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.