Abstract

The DNA sequence of the replication module, part of the lysis module, and remnants of a lysogenic module from the lytic P335 species lactococcal bacteriophage φ31 was determined, and its regulatory elements were investigated. The identification of a characteristic genetic switch including two divergent promoters and two cognate repressor genes strongly indicates that φ31 was derived from a temperate bacteriophage. Regulation of the two early promoters was analyzed by primer extension and transcriptional promoter fusions to a lacLM reporter. The regulatory behavior of the promoter region differed significantly from the genetic responses of temperate Lactococcus lactis phages. The cro gene homologue regulates its own production and is an efficient repressor of cI gene expression. No detectable cI gene expression could be measured in the presence of cro. cI gene expression in the absence of cro exerted minor influences on the regulation of the two promoters within the genetic switch. Homology comparisons revealed a replication module which is most likely expressed from the promoter located upstream of the cro gene homologue. The replication module encoded genes with strong homology to helicases and primases found in several Streptococcus thermophilus phages. Downstream of the primase homologue, an AT-rich noncoding origin region was identified. The characteristics and location of this region and its ability to reduce the efficiency of plaquing of φ31 106-fold when present at high copy number in trans provide evidence for identification of the phage origin of replication. Phage φ31 is an obligately lytic phage that was isolated from commercial dairy fermentation environments. Neither a phage attachment site nor an integrase gene, required to establish lysogeny, was identified, explaining its lytic lifestyle and suggesting its origin from a temperate phage ancestor. Several regions showing extensive DNA and protein homologies to different temperate phages of Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, and Streptococcus were also discovered, indicating the likely exchange of DNA cassettes through horizontal gene transfer in the dynamic ecological environment of dairy fermentations.

Lactococcus lactis is used extensively as starter culture in the dairy industry, where the main function is to convert lactose to lactic acid. One of the predominant reasons for fermentation failures is infection of the starter culture by bacteriophages, resulting in slow acid formation and a product of inferior value. The sources of phage infection for the predominant c2 and 936 species are environmental and include raw milk and in-plant contamination. However, the use of lysogenic starter cultures has recently been implicated in the appearance of virulent P335 phages in the industry (1, 4, 19, 49). To overcome this problem, a variety of different strategies have been implemented, including improved sanitation, rotation of starter cultures (18, 61), use of multiple-strain cultures (64), and the use of phage-resistant starter cultures (for a review, see reference 22).

Lactococcal phages are classified into 12 different species based on morphology, DNA homology, and protein profiles (35), but only three phage species, the prolate-headed c2 species and the isometric-headed 936 and P335 species represent the major virulent types responsible for problems in dairy plants. There are no known temperate phages in the group of the c2 and 936 species, while the P335 species contains both temperate and lytic phages (35). Historically, it was believed that temperate phages did not contribute to the emergence of lytic phages in L. lactis (33). However, the increasing appearance of new lytic phages belonging to the P335 species, supported by DNA homology studies showing extensive homology between lytic and temperate P335 phage species, indicates that temperate phages or a phage remnant constitutes an important source for the development of new lytic bacteriophages (1, 19, 49, 69). Recent studies have shown that introduction of plasmids encoding phage resistance mechanisms selects for new virulent P335 phage species via acquisition of plasmid sequences or chromosomal regions of L. lactis (4, 19, 30, 49). The new recombinant phages are resistant to the original anti-phage system and, in some cases, have acquired new origins of replication (4, 19). Since the first complete phage genome sequence of bIL67 (c2 species) was published (60), several complete genome sequences of both temperate and lytic phages from Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, and Streptococcus thermophilus have become available (2, 22, 44, 67). The sequence information on LAB phages provided important insights into the genome organization, evolution, and relationships between lytic and temperate bacteriophages, which is essential for the future development of new phage-resistant starter culture strains. Genome analysis has shown that obligately lytic phages such as c2 (c2 species) and sk1 (936 species) contain genes required for lytic growth organized in differently oriented clusters (12, 42, 43), while the lytic genes of temperate phages belonging to the P335 species are found in one large cluster (6, 66). To our knowledge, no extensive sequence data are available on lytic members of the P335 species. Temperate phages of the P335 species and other temperate LAB phages are highly modular, organized with genes similar in function clustered together. Typically, genes needed for lysogeny are transcribed divergently and located adjacent to the genes required for lytic propagation. The lysogenic module usually encodes a repressor needed for maintenance of the prophage state and an integrase, which is essential for bacteriophage integration into the bacterial genome. The lytic module is comprised of another repressor, which acts by repressing the lysogeny module during lytic propagation. Following this repressor and in the same transcriptional orientation are gene clusters involved in phage replication, packaging, and lysis of the host cell (for a review, see reference 67).

Previous studies of the lytic phage φ31 (P335 species) have shown that two distinct DNA regions exhibit high sequence identity to temperate members of the BK5-T and P335 species (16, 55, 70). However, no sequence data were available to explain the obligately lytic lifestyle of φ31 and other lytic members of the P335 species. This study was conducted to understand the basis of the obligate lytic behavior of phage φ31. A 10.8-kb DNA region covering the putative replication module and a genetic switch directing lytic or lysogenic components was identified in φ31. The genetic components required to establish lysogeny, however, were incomplete in this virulent member of the P335 species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, bacteriophage, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and bacteriophage used in this study are listed in Table 1. L. lactis strains were grown in M17 broth with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose at 30°C. For selection of plasmids in L. lactis, 1 μg of erythromycin per ml and/or 5 μg of chloramphenicol per ml was added to the medium when appropriate. Escherichia coli strain DH10B was cultivated in Luria-Bertani or brain heart infusion medium, supplemented with 200 μg of erythromycin per ml or 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml when appropriate, at 37°C. Phage φ31, a small, lytic, isometric phage with a DNA genome of 31.9 kb, was propagated on L. lactis NCK203 in GM17 medium supplemented with 10 mM CaCl2. Determination of the efficiency of plaquing (EOP) was performed as previously described (63).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and bacteriophage used in this study

| Bacterium, plasmid, or bacteriophage | Relevant characteristic(s) or DNA inserta | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||

| L. lactis | ||

| NCK203 | Phage φ31-sensitive host | 29 |

| MG1363 | Host for promoter and complementation studies | 23 |

| E. coli DH10B | E. coli cloning host | 27 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript KS II | E. coli cloning vector; Apr | Stratagene |

| pTRKH2 | E. coli-Lactococcus cloning vector, high copy number in Lactococcus; Ermr | 54 |

| pAK80 | Lactococcus promoter probe vector, promoterless lacLM reporter gene; Ermr | 32 |

| pCI372 | E. coli-Lactococcus cloning vector, low copy number in Lactococcus; Camr | 28 |

| pTRK361 | pTRKH2 + 4.5-kb SalI-BamHI ori31 fragment from φ31 | 52 |

| pTRK402 | pTRKH2 + 4.3-kb EcoRV-SalI AbiA sensitivity fragment from φ31 | 16 |

| pTRK409 | pTRKH2 + 1.4-kb EcoRV-HindIII AbiA sensitivity fragment from φ31 | 16 |

| pTRK627 | pBluescript KS II + 1.8-kb PvuII-EcoRV early promoter region from φ31, positions 4–1777 | This study |

| pSMBI 1 | pAK80 + 909-bp XhoI-BamHI PCR fragment, positions 640–1548 | This study |

| pSMBI 4 | pAK80 + 1,240-bp BamHI PCR fragment, positions 640–1879 | This study |

| pSMBI 8 | pAK80 + 1,240-bp BamHI PCR fragment, opposite orientation from pSMBI4 | This study |

| pSMBI 10 | pTRKH2 + 439-bp XhoI-SmaI ori31 fragment, positions 8256–8694 | This study |

| pSMBI 25 | pAK80 + 228-bp BamHI fragment, positions 1321–1548 | This study |

| pSMBI 27 | pAK80 + 228-bp BamHI fragment, opposite orientation from pSMBI25 | This study |

| pSMBI 30 | pAK80 + 909-bp BamHI fragment, opposite direction from pSMBI1 | This study |

| pSMBI 33 | pAK80 + 559-bp BamHI fragment, positions 1321–1879 | This study |

| pSMBI 35 | pAK80 + 559-bp BamHI fragment, opposite orientation from pSMBI33 | This study |

| pSMBI 66 | pCI372 + 909-bp XhoI-BamHI fragment containing cI gene, positions 640–1548 | This study |

| pSMBI 67 | pCI372 + 559-bp BamHI fragment containing cro gene, positions 1321–1879 | This study |

| Bacteriophage φ31 | Small isometric phage for NCK203 P335 species | 1 |

Ermr, erythromycin resistance; Apr, ampicillin resistance; Camr, chloramphenicol resistance.

Measurement of β-galactosidase activity.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed on exponentially growing cultures (optical density at 600 nm ≅0.75) as previously described (32). Measurements were averages of at least three independent experiments.

Cloning, plasmid and bacteriophage DNA isolation, and transformation.

Standard procedures were used for DNA manipulations (59). Large-scale plasmid preparations for sequencing and cloning were isolated from E. coli using Jet Prep columns (Genomed) according to the manufacturer's directions. L. lactis small-scale plasmid preparations were performed as described previously (53). Genomic phage DNA was isolated as described elsewhere (19). E. coli competent cells (ElectroMAX DH10B) were electroporated as described by the manufacturer. L. lactis MG1363 was transformed as described by Holo and Nes (31), and L. lactis NCK203 was transformed as described by Walker and Klaenhammer (69).

PCR and DNA sequencing.

Plasmid DNA sequencing was performed on both strands using an ABI model 377 automated gene sequencer (Perkin-Elmer) or an ALFexpress DNA sequencer (Pharmacia Biotech). DNA and deduced amino acid sequences were analyzed using the BlastN and BlastP programs available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST. PCR amplifications were performed using the Taq DNA polymerase from Gibco BRL as recommended by the manufacturer.

Plasmid constructions.

pTRK627 was constructed by insertion of a 1.8-kb PvuII-EcoRV genomic fragment from φ31 into the EcoRV site of pBluescript KS II (Stratagene). pTRK627 contains the early promoter region of φ31. To study the regulation of the two promoters located in the early region, a collection of promoter fragments were fused to the lacLM reporter gene in the promoter probe vector pAK80 (32). The different promoter fragments were all amplified by PCR using genomic φ31 DNA as the template. A 909-bp XhoI-BamHI fragment obtained by using primers cI-XhoI-P1 (5′GGC CGC TCG AGC CTG TTC CGT CTG CCG 3′) and cI-BamHI-P2 (5′ TAG TAG GAT CCT TTT GGG AGA GAT AAA GCG CC 3′) was cloned into pAK80 digested with XhoI and BamHI, resulting in pSMBI 1. Plasmids pSMBI4 and pSMBI8 were constructed by cloning of a 1,240-bp BamHI fragment, obtained by using primers cro-BamHI-P1 (5′ TAG TAG GAT CCC CTT TCT TTT TAT AAA GTT CAA ATT TTT TGG AC 3′) and cI-BamHI-P2, into pAK80 digested with BamHI. The inserts in pSMBI4 and pSMBI8 are in opposite directions with respect to the lacLM reporter gene in pAK80.

A 228-bp PCR product that only covers the two promoters was obtained by using primer BamHI-Prom1 (5′ TAG TAG GAT CCT GTC TTA ATC CTC GGT CGT TC 3′) and primer cI-BamHI-P1 (5′ TAG TAG GAT CCC CTG TTC CGT CTG CCG 3′). The PCR fragment was digested with BamHI and subsequently ligated into pAK80, resulting in pSMBI25 and pSMBI27. The inserted fragments in pSMBI25 and pSMBI27 are in opposite directions with respect to the lacLM gene. pSMBI30 was constructed by insertion of a 909-bp BamHI fragment, obtained by the use of primers cI-BamHI-P2 and cI-BamHI-P1, into BamHI-digested pAK80. pSMBI1, and pSMBI30 contain inserts that are identical but in opposite directions with respect to lacLM. A 559-bp fragment containing the two promoters, as well as the cro-like gene, was obtained by using primers BamHI-Prom1 and cro-BamHI-P1. Insertion of the fragment into BamHI-digested pAK80, in opposite directions with respect to lacLM, gave rise to pSMBI33 and pSMBI35.

The minimal origin of φ31 was amplified by PCR using primers XhoI-ori-Phi31 (5′ GGC CGC TCG AGG GGA TAG TGA AGA TAA AGA AAA GCC and SmaI-ori1 (5′ ATT CCC CCG GGC CTC GAT TGG TAT CAT AG 3′). The 439-bp PCR product, after digestion with XhoI and SmaI, was inserted into similarly digested pTRKH2, resulting in pSMBI10. To construct pSMBI66, a 909-bp XhoI-BamHI fragment from pSMBI1 was inserted into the SalI-BamHI sites of pCI372. To construct pSMBI67, a 559-bp BamHI fragment from pSMBI33 was moved into the BamHI site of pCI372. All plasmid constructions containing PCR-amplified fragments were sequenced to verify that no errors were introduced by the PCR amplification.

RNA extraction, oligonucleotide labeling, and primer extension.

Total RNA was isolated from L. lactis NCK203 at various time points during the φ31 infection cycle (multiplicity of infection ≅ 5) using the TRIzol reagent from Gibco BRL as described previously (16). Primer extension analysis was performed as described by Kullen and Klaenhammer (38), except for the following modifications. Primers (750 ng) Phi31 Rev3 (5′ CCG TAC TGA ATG CTC CAT GAT TGT TCG C 3′) and BamHI-Prom1 (5′ TAG TAG GAT CCT GTC TTA ATC CTC GGT CGT TC 3′) were end labeled with 30 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP using 10 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase. Approximately 50 μg of total RNA from each time point was mixed with 150 ng of each labeled primer. The subsequent treatments were done as previously described (38). The primer extension products were analyzed on a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel next to a sequence ladder of the same primer and plasmid pTRK627 as the template.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence described in this study has been deposited in the EMBL database under accession number AJ292531.

RESULTS

Mapping of the φ31 origin of replication.

Previous studies have shown that a 4.5 kb SalI-BamHI fragment of φ31 (ori31) is able to protect against φ31 proliferation when carried on a high-copy-number plasmid (52). It was suggested that the plasmid-borne ori31 fragment interfered with phage replication by titrating out one or more of the replication factors needed for phage DNA replication (29, 52). To determine the precise location of the putative origin of replication, the 4.5-kb SalI-BamHI fragment located in pTRK361 was sequenced. Analysis of the sequence obtained showed a DNA region scattered with several open reading frames (ORFs), including a putative primase and a short noncoding region (Fig. 1). Most replication origins of phages from lactic acid bacteria are located within noncoding DNA regions which have a high AT content and are rich in direct repeats, as well as inverted repeats (2, 12, 21, 29). The identification of a 230-bp noncoding AT-rich region located just downstream of a gene encoding a putative primase indicates that this region encodes the replication origin of φ31 (Fig. 2). Several direct and inverted repeats were identified within this area. A BlastN search with the noncoding DNA sequence did not reveal any homology to other DNA sequences in the databases. However, by using the Bestfit program, we obtained 70% identity between the 230-bp putative origin of φ31 and a 253-bp region containing the putative origin of S. thermophilus phage Sfi21 (13) and, importantly, most of the repeats were similarly organized (data not shown). Additionally, the structural gene organization in this particular region of φ31 is very similar to the organization found in several S. thermophilus phages, such as Sfi19, Sfi21, O1205, and DT1 (10, 13, 62, 65), and in Lactobacillus gasseri phage φadh (2). In these phages, noncoding DNA regions were identified immediately downstream of the putative primase gene. Additionally, in some cases, a phage-encoded resistance (per) phenotype against the particular phage was also demonstrated, which is typical of a phage origin of replication (21, 29, 47). The failure of the 4.5-kb SalI-BamHI fragment to support DNA replication of a nonreplicating vector in L. lactis (data not shown) suggests that host factors alone are not sufficient to carry out DNA replication, but additional phage-encoded factors are required.

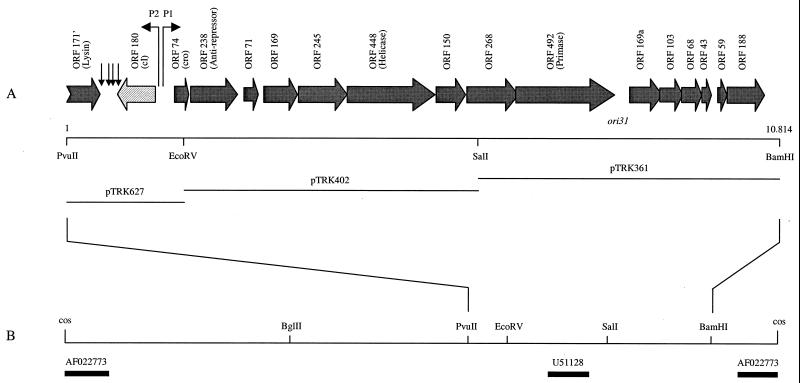

FIG. 1.

(A) Structural organization of the sequenced 10,814-bp region of the φ31 genome. The arrowhead indicates the orientation of each ORF, which is named according to its length in amino acids. Bent arrows indicate the two early promoters, P1 and P2. Vertical arrows indicate the positions of inverted repeats, which may be involved in the termination of transcription. The origin of replication of φ31 (ori31) is indicated. Unique restriction sites within the region are marked below the ORFs. The inserts of the three plasmids (pTRK627, pTRK402, and pTRK361) used for DNA sequencing are indicated by black lines. The figure is drawn to scale. (B) Restriction enzyme map of the φ31 (31.9-kb) genome adapted from Alatossava and Klaenhammer (1). Only restriction sites relevant for this study are indicated. The map is linearized at the cos site. Black bars indicate previous φ31 sequences which have been deposited in databases by Walker et al. (70) (AF022773) and Dinsmore and Klaenhammer (16) (U51128). The figure is drawn to scale.

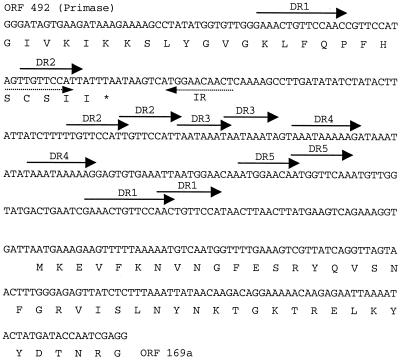

FIG. 2.

Structure and sequence of the origin of replication of phage φ31. The illustrated 439-bp sequence is contained in pSMBI10 and confers the per phenotype. Solid arrows indicate direct repeats, numbered DR1 to DR4, and dashed arrows indicate an inverted repeat (IR). The deduced amino acid sequences of the C terminus of ORF 492 (primase gene) and the N terminus of ORF 169a are shown below the nucleotide sequence. The asterisk represents the stop codon of ORF 492.

If the noncoding region located between the putative primase gene and ORF 169a in φ31 acts as an origin of replication in vivo, it was expected to possess a strong per phenotype when carried on a high-copy-number plasmid. Therefore, a 439-bp region covering the noncoding region and the adjacent flanking sequences were amplified by PCR and inserted into pTRKH2, resulting in plasmid pSMBI10. To assess the effect on phage infection, standard bacteriophage plaque assays were performed on L. lactis strains NCK203(pTRKH2), NCK203(pTRK361), and NCK203(pSMBI10). When strain NCK203 containing pTRKH2 was challenged with phage φ31, the EOP was 1. However, in the presence of pTRK361, containing the original 4.5-kb SalI-BamHI ori31 fragment, or pSMBI10, the EOP was reduced dramatically to approximately 1.2 × 10−6. Therefore, the 439-bp noncoding fragment has a strong per phenotype, which is identical to the original per phenotype observed in high-copy-number vector pTRK361 (52).

Identification of an early expressed promoter.

The inability of the original 4.5-kb ori31 fragment to mediate autonomous DNA replication in L. lactis suggests that phage-encoded factors are essential for DNA replication. Phage genes encoding DNA replication factors are likely expressed from an early promoter that is recognized by the host transcription machinery without the need for additional phage-encoded transcription factors. Therefore, a search was initiated for phage promoters that are recognized immediately after phage φ31 infection. To map early expressed promoters, we employed an RNA transcript-capping method used previously to pinpoint a phage-inducible promoter (17). Total RNA was isolated 3, 10, and 20 min after the onset of φ31 infection and 5′ labeled with vaccinia virus guanylyltransferase and [α-32P]GTP. Phage φ31 genomic DNA was digested with EcoRV, PvuII, and EcoRV plus PvuII and subsequently hybridized with the labeled RNA probes. Based on the hybridization patterns obtained with the RNA probes generated 3 min after infection, a single minimal 1.8-kb PvuII-EcoRV fragment containing an early expressed promoter was identified (data not shown). According to the published restriction map of φ31 (1), this fragment is located immediately upstream of the EcoRV-SalI fragment contained in pTRK402 (16) (Fig. 1). Only one early hybridizing signal was observed in each restriction enzyme digest, indicating that only a single early promoter region is located on the phage genome. The 1.8-kb PvuII-EcoRV fragment was inserted into pBluescript, resulting in pTRK627, and the DNA sequence was determined.

Nucleotide sequence of a 10.8-kb PvuII-BamHI fragment from φ31.

The identification of a region containing an early expressed promoter, the origin of replication, and a gene encoding a putative primase indicated that this region of the phage genome is involved in DNA replication. The DNA sequence and the gene organization of the putative φ31 replication module were determined by assembling previous sequences and closing gaps as needed.

Previously, a 4.3-kb EcoRV-SalI fragment (pTRK402) located downstream of the early promoter (pTRK627) and upstream of the ori31 region (pTRK361) was partially sequenced (Fig. 1) and found to contain a 1.7-kb region involved in sensitivity to the abortive phage defense mechanism AbiA (16). Combination of the DNA sequences obtained from pTRK627, pTRK402, and pTRK361 gave an approximately 10.8-kb contig nucleotide sequence (Fig. 1). Analysis of this sequence revealed the presence of 17 complete ORFs and 1 incomplete ORF. These were identified based on the criteria that an ORF consists of at least 40 amino acids and initiates with the start codon AUG, GUG, or UUG preceded by an appropriate ribosome-binding site complementary to the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA (3′ CUUUCCUCC 5′) from L. lactis. All putative ORFs initiate with the AUG start codon, except the gene encoding a putative helicase (ORF 448), which diverges from the criteria by using either AUA or AUU as the putative start codon. All putative ORFs are located on the same strand, except the putative cI homologue. In addition to the noncoding region containing the origin of replication, two other extended noncoding regions were identified. A 213-bp noncoding region was located between the putative cI and Cro repressors and includes two divergently oriented promoters. Another 368-bp noncoding region was located between the 3′ end of the putative lysin gene and the 3′ end of the putative cI gene. This region contains four inverted repeats, which may function as transcription terminators of the lysin gene and the cI gene. BlastN and BlastP searches of the nucleotide sequences and the deduced amino acid sequences of putative ORFs were conducted and compared with the available databases. The most significant protein sequence similarities are summarized in Table 2 and analyzed below.

TABLE 2.

General features of the putative ORFs within the 10,814-bp region of the φ31 genome

| φ31 gene | Putative function | Start | Stop | Size (aa) | Similar sequence(s) | P valued | Identitye (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF 171′ | Lysin like | 3 | 518 | >171a | ORF 259 from L. lactis φBK5-T | 2e-95 | 98 | 6 |

| ORF 180b | cI repressor like | 1363 | 821 | 180 | ORF 4 from L. lactis φTP901-1 | 2e-40 | 68 | 45 |

| Repressor from S. aureus φPVL | 1e-25 | 49 | 36 | |||||

| ORF 4 from S. thermophilus φO1205 | 5e-20 | 42 | 62 | |||||

| ORF 74 | Cro repressor like | 1637 | 1861 | 74 | ORF 69 from S. thermophilus φSfi11 | 2e-15 | 57 | 44 |

| ORF 69 from S. thermophilus φSfi18 | 4e-15 | 57 | 44 | |||||

| ORF 69 from S. thermophilus φSfi19 | 2e-14 | 56 | 14 | |||||

| ORF 5 from S. thermophilus φO1205 | 2e-14 | 53 | 62 | |||||

| ORF 5 from φTP901-1 | 9e-13 | 50 | 45 | |||||

| ORF 238 | Antirepressor like | 1888 | 2604 | 238 | ORF 6 from φTP901-1 | 1e-66 | 94 | 45 |

| Antirepressor from S. thermophilus φTP-J34 | 1e-31 | 54 | 51 | |||||

| ORF 71 | 2700 | 2915 | 71 | ORF 11 from L. lactis φTuc2009 | 2e-35 | 98 | 47 | |

| ORF 169 | 3000 | 3509 | 169 | ORF 169 from φBK5-T | 4e-74 | 82 | 6 | |

| ORF 245 | 3509 | 4246 | 245 | ORF 11 from L. lactis φTPW22 | e-136 | 98 | 56 | |

| ORF 448c | Helicase like | 4255 | 5601 | 448 | Putative helicase from S. thermophilus φDT1 | e-154 | 58 | 65 |

| ORF 10 from φO1205 | e-154 | 57 | 62 | |||||

| ORF 443 from φSfi19 | e-154 | 57 | 14 | |||||

| ORF 150 | 5619 | 6071 | 150 | ORF 34 from φDT1 | 2e-47 | 63 | 65 | |

| ORF 268 | 6074 | 6880 | 268 | ORF 12 from φO1205 | 5e-60 | 44 | 62 | |

| ORF 492 | Primase like | 6855 | 8333 | 492 | Putative primase from φSfi19 | e-133 | 50 | 14 |

| Putative primase from φDT1 | e-133 | 50 | 65 | |||||

| ORF 13 from φO1205 | e-133 | 50 | 62 | |||||

| ORF 169a | 8561 | 9070 | 169 | 19.8-kDa protein from B. subtilis φSPO1 | 3e-22 | 36 | 24 | |

| Group I intron endonuclease from B. subtilis φphi-E | 1e-20 | 41 | 25 | |||||

| Group I intron endonuclease from B. subtilis φSP82 | 2e-19 | 41 | 25 | |||||

| ORF 103 | 9063 | 9374 | 103 | ORF 38 from φDT1 | 2e-33 | 64 | 65 | |

| ORF 68 | 9477 | 9683 | 68 | ORF 68a from L. lactis φul36 | 4e-34 | 100 | 4 | |

| ORF 43 | 9692 | 9823 | 43 | Unknown | ||||

| ORF 59 | 9935 | 10114 | 59 | ORF 17 from L. lactis φr1t | 5e-27 | 98 | 66 | |

| ORF 188 | 10104 | 10670 | 188 | ORF from φul36A | 6e-85 | 84 | 39 |

Only the 171 C-terminal amino acids are available from this study.

The cI homologue (ORF 180) has three potential translational initiation sites; see text.

The helicase homologue (ORF 448) has two potential translational initiation sites; see text.

Probabilities were derived from BlastP scores for obtaining a match by chance.

Percent identity was obtained from the BlastP analysis.

The incomplete lysin gene.

Database searches with the deduced amino acid sequence of incomplete ORF 171′ revealed a high degree of identity (98%) to ORF 259, encoding a cell wall-lytic enzyme from the temperate L. lactis phage BK5-T (6). Despite the lack of the 5′ end of the gene, we propose that ORF 171′ encodes the lysin of phage φ31.

Identification of a regulatory region encoding two repressor homologues, cI and Cro.

Located 368 bp downstream of the putative lysin gene, ORF 180 was identified in the opposite orientation. ORF 180 shows significant similarity to a group of phage proteins that function as repressors of lytic gene expression in temperate bacteriophages. The highest level of identity found (68%) was to ORF 4 (180 amino acids) of the temperate L. lactis phage TP901-1 (45). Similar to ORF 4 of TP901-1 and some other repressor proteins, ORF 180 showed no helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding motif or RecA-mediated cleavage site. The potential ribosome-binding site (5′ AAGAA 3′) located upstream of the AUG start codon shows weak complementarity to the L. lactis 3′ 16S rRNA, indicating weak translation of cI. Alternatively, two other AUG start codons were located in the vicinity that might also serve as translation initiation codons. These would specify proteins of 174 and 187 amino acids, respectively. However, neither was preceded by ribosome-binding sites that were better than the ribosome-binding site located upstream of ORF 180. In the case of the 187-amino-acid alternative, only 6 bp separates the −10 promoter region from the AUG start codon. This is very analogous to the situation seen for the rro gene of the temperate L. lactis phage r1t (50) and for the cI repressor gene of E. coli phage λ (57), where the adenine of the start codon also acts as the transcriptional start site. Despite the high diversity between ORF 180 (alternatively, ORF 174 or ORF 187) and typical cI proteins, we suggest that this ORF specifies a protein with a cI-like repressor function and therefore it was renamed cI.

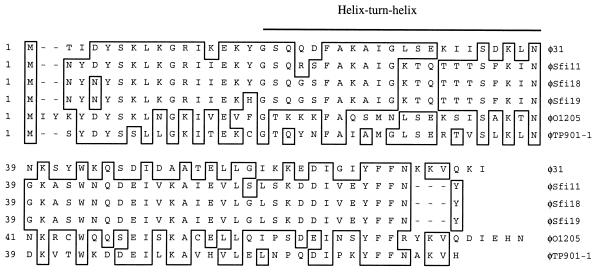

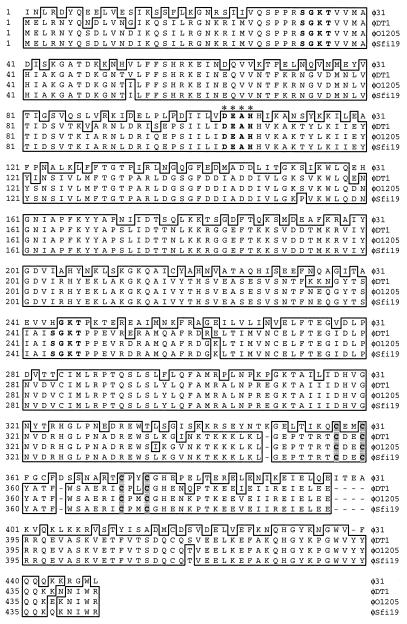

Located 213 bp downstream of the cI gene in the opposite orientation was an ORF of 74 amino acids which showed homology to Cro-like proteins specified by ORF 69 of S. thermophilus phages φSfi11, φSfi18, and φSfi19 (14, 44), ORF 5 of S. thermophilus phage φO1205 (62), and ORF 5 of L. lactis phage TP901-1 (45). Based on their size, relative location, and orientation, it has been proposed that they may have a function analogous to that of the Cro repressor of E. coli bacteriophage λ. The overall levels of identity of ORF 74 to these ORFs were 57, 57, 55, 53, and 50%, respectively (Fig. 3). Analysis of ORF 74 for the presence of HTH motifs using the HTH prediction tool available at http://pbil.ibcp.fr revealed an HTH motif extending from Gly17 to Asn38. Upstream of ORF 74, a strong ribosome-binding site (5′ GAAAGGATG 3′) was identified. Based on the similarity of ORF 74 to other proteins with putative Cro-like functions, the typical gene location, and the HTH DNA-binding motif, we expected that ORF 74 plays a Cro-like role in φ31. ORF 74 was consequently termed Cro.

FIG. 3.

Multiple-sequence alignment of the putative Cro sequence of φ31; ORF69 (accession no. AF158600, AF158601, and AF115102) of S. thermophilus phages Sfi11, Sfi18, and Sfi19; ORF5 (accession no. U88974) of S. thermophilus phage O1205; and ORF 5 (accession no. Y14232) of L. lactis phage TP901-1. Identical amino acids are boxed. The putative HTH motif involved in DNA binding is shown above the sequence.

The region between cI and Cro encodes two divergent promoters.

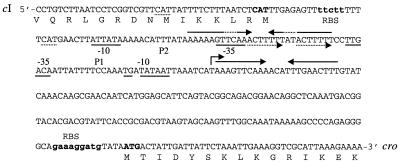

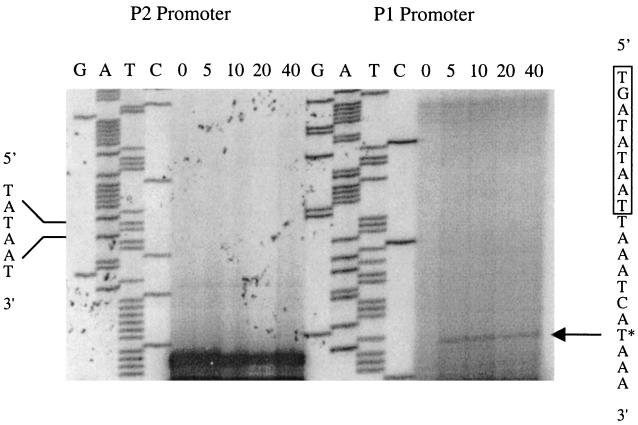

Previous studies with lambdoid and LAB phages have revealed an intergenic region located between cI and Cro that contains two oppositely oriented promoters and an operator site (5, 10, 20, 37, 40, 45, 50, 51). Two putative divergently oriented consensus promoters, designated P1 and P2, were found within the 213-bp intergenic region of φ31. The P1 promoter reading toward the cro gene contained a perfect consensus sequence with an extended −10 motif (15), while P2 reading toward the cI gene deviated slightly from the consensus sequence in the −35 region (Fig. 4). The activity of the two putative promoters during temporal phage development was analyzed by primer extension using a cro-specific primer and a cI-specific primer. RNA was extracted at various time points during the φ31 infection cycle and used for primer extension analysis. With the cro-specific primer, a cDNA product was identified 5 min after infection and it was retained for at least 40 min (Fig. 5). No cDNA product was obtained using RNA isolated from uninfected cells (time zero), demonstrating that the primer extension product obtained 5 min after infection was phage specific. The identified transcription start site is located 8 bp downstream of the extended −10 region of the P1 promoter. In contrast, no transcript initiated from the P2 promoter, suggesting that P2 is repressed during phage φ31 infection. A 164-bp nontranslated mRNA leader region preceded the cro-specific transcript. The distance from the −10 region of the putative P2 promoter to the start codon of the cI gene is between 6 and 45 bp, depending on which initiation codon is used for cI translation. Analysis of the sequences intervening between cI and cro revealed two inverted repeats which may serve as repressor-binding sites for the cI or Cro protein. Binding to this inverted repeat could repress transcription of the cI gene, since one of the inverted repeats overlapped the putative −35 region of the P2 promoter. The other inverted repeat was located in the 5′ end of the untranslated cro mRNA leader and could also act to stabilize mRNA or as a repressor-binding site. Site-directed mutagenesis will be required to deduce the exact role and importance of these inverted repeats for promoter regulation.

FIG. 4.

Nucleotide sequence of the divergent promoter region located between the oppositely directed cI and Cro homologues. The −10 and −35 sequences of promoters P1 and P2 are underlined. A bent arrow indicates the transcriptional start site located downstream of P1. Inverted repeats are indicated by solid arrows, and stippled arrows indicate a direct repeat. The possible translational initiation codons of the two genes are in boldface uppercase letters, while their respective ribosome-bindings sites (RBS) are in boldface lowercase letters. Alternative translational initiation codons of the cI protein are stippled.

FIG. 5.

Primer extension analysis of the early promoter region of phage φ31. Total RNA was extracted at various time points after φ31 infection, indicated above the panels (minutes), and used for determination of transcriptional start sites. The nucleotide sequence ladders obtained with the corresponding primers are also shown (GATC). The relevant nucleotide sequence of P1 is indicated to the right. The extended −10 sequence of P1 is boxed, and the transcriptional start site is marked with an asterisk. The putative −10 sequence of P2 is indicated to the left.

Identification of putative antirepressor ORF 238.

ORF 238 was identified downstream of the Cro homologue and was preceded by a strong ribosome-binding site. The C-terminal half of ORF 238 exhibited 94% amino acid identity to ORF 6 from temperate L. lactis phage TP901-1 (45), while the N-terminal half of ORF 238 showed homology (54% amino acid identity) to a putative antirepressor homologue ORF 238 gene product from temperate S. thermophilus phage TP-J34 (51). No biological function has yet been proven for ORF 6, the putative TP-J34 antirepressor homologue, or related ORF 287 from temperate S. thermophilus phage Sfi21 (9, 10). A bipartite immunity system for control of lysogeny was suggested for Sfi21 (10), but a spontaneous Sfi21 deletion mutant lacking the C terminus of ORF 287 has been isolated (9), demonstrating that the putative antirepressor (ORF 287) is nonessential for both the lytic and lysogenic life cycles.

Identification of a putative helicase and primase.

The deduced protein sequence of ORF 448 (or ORF 449, depending on which start codon is used for translation initiation) shows strong similarity (57 to 58% identity) to a group of helicase-like proteins encoded by several S. thermophilus phages (Fig. 6). Similar to the helicase homologues identified in the S. thermophilus phages, several motifs were found within the coding sequence of ORF 448. In the N terminus, a nucleotide-binding site and a DEAH box was identified, which is typical in a subgroup of helicases (26, 68). A second nucleotide-binding site was found in the middle of the putative helicase protein, and a zinc finger motif (CX2CX11CX2C) was located in the C terminus of ORF 448 (Fig. 6). Based on the homology and the sequence features, it appears likely that ORF 448 is a helicase and plays a role in unwinding the DNA template during φ31 replication.

FIG. 6.

Multiple alignment of the φ31 helicase homologue (ORF 448) with putative helicases from S. thermophilus phages DT1 (accession no. AF085222), O1205 (accession no. U88974), and Sfi19 (accession no. AF115102). Identical amino acids are boxed. Two nucleotide-binding sites (Walker A motifs), located in the N terminus and in the middle of the protein, are marked in boldface letters. The conserved DEAH box is indicated in boldface letters and marked by asterisks above the sequence. The four conserved cysteine residues within the zinc finger motif are shaded.

The predicted protein products from ORF 150 and ORF 268 show significant similarities to proteins encoded by ORFs located in similar genomic positions of several S. thermophilus phages, such as DT1, O1205, Sfi21, and Sfi19. No potential function could be assigned to any of these ORFs.

The protein derived from ORF 492 shows approximately 50% identity to putative DNA primases from a group of S. thermophilus phages, including Sfi19, DT1, and O1205. Just downstream of the primase gene, a noncoding region with features typical of replication origins was identified.

ORF 169a is homologous to intron-encoded endonucleases.

ORF 169a exhibits 36 to 41% identity to several bacteriophage-encoded site-specific endonucleases that all are located within self-splicing group I introns in different B. subtilis phages, such as SPO1, phi-E, and SP82 (24, 25). Whether ORF 169a actually is located within an intron in φ31 is still unclear. All of the bacteriophage introns identified so far interrupt genes with different functions, but no obvious gene seems to be interrupted by ORF 169a in φ31. Furthermore, we were not able to identify the conserved sequence elements common to group I introns (11; Robin Gutell, personal communication). Additionally, attempts to identify a spliced mRNA product using reverse transcription-PCR over this region were unsuccessful.

No functions could be assigned to ORFs 103, 68, 59, and 188, but the ORFs showed 64, 100, 98, and 84% identity, respectively, to different ORFs from S. thermophilus and L. lactis phages.

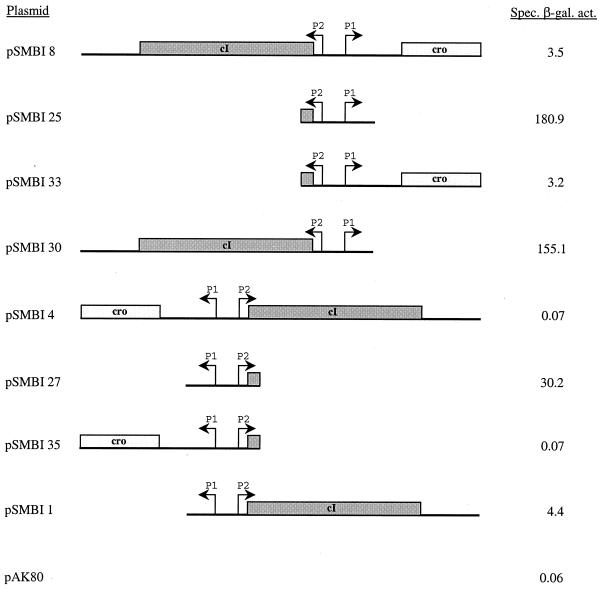

Cro is an efficient repressor of P1 and P2 promoter expression.

To study the regulation of the divergent promoters P1 and P2, located between the cI and Cro repressor homologues, we made a collection of transcriptional gene fusions to the promoterless reporter genes lacLM of pAK80 (32) (Fig. 7). The region encompassing the two promoters and the cognate repressor genes were amplified by PCR and cloned in both orientations with respect to the lacLM reporter gene, allowing analysis of each promoter in the presence of one or both repressor proteins. Measurement of β-galactosidase activity in L. lactis MG1363 in constructs with cI and Cro showed that the P2 promoter (pSMBI4) was completely repressed (<0.1 Miller unit), while the P1 promoter (pSMBI8) was marginally active (∼3.5 Miller units). The closed state of P2 agrees with the primer extension analysis described above showing that no extension product was obtained using the cI gene-specific primer.

FIG. 7.

Analysis of P1 and P2 promoter regulation. The indicated individual fragments were cloned into L. lactis promoter probe vector pAK80. The right endpoint of each fragment was transcriptionally fused to the lacLM reporter gene of pAK80. The plasmids were introduced into L. lactis MG1363, and β-galactosidase (β-gal.) assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The figure is drawn to scale. Spec. act., specific activity.

To separate the possible combined effect of both repressor proteins on promoter regulation, we analyzed transcription from P1 and P2 in the presence of each repressor alone (either Cro alone or cI alone) and in the absence of both. The β-galactosidase activities obtained from pSMBI25 (no repressor genes, P1 fused to lacLM) and pSMBI 27 (no repressor genes, P2 fused to lacLM) were 181 and 30 Miller units, respectively. This illustrates that removal of the repressors allows both P2 (weak) and P1 (strong) promoter activity. The β-galactosidase levels obtained from pSMBI 33 (Cro present, P1 fused to lacLM) were 3.2 U, 50-fold lower than in pSMBI25, indicating that Cro downregulates its own production. In addition, Cro appears to efficiently repress P2 (directed toward cI gene expression), as the β-galactosidase produced by plasmid pSMBI35 (Cro present, P2 fused to lacLM) did not exceed the background level produced by pAK80 without any promoter insert. These results indicate that the cro gene product represses cI gene expression very efficiently.

The effect of cI gene expression on the P1 and P2 promoters was also examined. The β-galactosidase activity obtained from pSMBI 30 (cI present, P1 fused to lacLM) was 155 Miller units, only slightly lower than the 181 Miller units obtained from pSMBI25. Therefore, the cI-like protein shows some repression of P1 promoter activity. Albeit that P2 is a weaker promoter, expression of cI in pSMBI 1 (cI present, P2 fused to lacLM) repressed its activity from 30 Miller units (in pSMBI 27) to 4 Miller units, a sevenfold reduction.

trans-complementation studies of cro and cI.

To confirm the strong negative regulation of both promoters by the Cro protein and the moderate repression of P2 by the cI protein, the two repressor genes were cloned individually into another compatible plasmid, pCI372, for trans-complementation studies. When Cro was provided in trans, a substantial decrease in β-galactosidase activity was observed for both pSMBI25 and pSMBI 27 (Table 3). These data demonstrate that Cro has a trans-acting ability to repress the expression of both promoters. In contrast, the donation of cI in trans did not significantly repress either P1 or P2. These data suggest that the impact of cI, in cis, on P2 expression is likely minor.

TABLE 3.

trans complementation of cro and cIa

| Plasmid | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| pCI372 | pSMBI66 (cI gene) | pSMBI67 (cro gene) | |

| pSMBI25 (P1-lacLM) | 209.4 | 223.8 | 0.57 |

| pSMBI27 (P2-lacLM) | 34.8 | 30.1 | 0.22 |

pSMBI25 and pSMBI27 contain the P1 and the P2 promoters fused to the lacLM reporter genes of pAK80, respectively. The cI gene was cloned into pCI372, resulting in pSMBI66, and the cro gene was cloned into pCI372, resulting in pSMBI67. pSMBI25 and pSMBI27 were separately cotransformed with pCI372, pSMBI66, and pSMBI67 into L. lactis MG1363. Determination of β-galactosidase activity was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have established the sequence of a 10.8-kb region from lytic Lactococcus phage φ31 that encodes remnants from a genetic switch and the DNA replication region. Analysis of the nucleotide sequence revealed the presence of one incomplete ORF and 17 full-length ORFs longer than 40 amino acids. Among these were three ORFs described previously that were involved in sensitivity to the abortive phage infection system AbiA (16). The deduced amino acid sequence of the remaining ORFs was compared to the contents of the available protein databases, and several ORFs showing significant homology to ORFs from other LAB phages were identified. The identified ORFs were clustered in DNA modules that directed key functions responsible for lysis, DNA replication, and control of lifestyle (lytic versus lysogenic).

The φ31 origin of replication (ori31) was originally located on a 4.5-kb fragment (52) by demonstration of its ability to retard phage replication when presented in trans on a high-copy-number plasmid. First demonstrated by Hill et al. (29) using phage 50, this phenomenon has been shown in other Lactococcus and S. thermophilus phages (21, 47). In this study, we mapped ori31 to a 439-bp noncoding DNA sequence located just downstream of a gene encoding the putative φ31 primase. This was based on (i) the ability of the 439-bp fragment to reduce the EOP approximately 106-fold (per phenotype), (ii) a typical structure with several repeats, and (iii) the conserved location for replication origins within a group of related phages from S. thermophilus and L. gasseri. The ori31 sequence was distinct from P335 phage φ50 (29), consistent with our previous functional observation that the presence of ori50 does not interfere with phage 31 replication and that ori31 does not interfere in trans with phage 50 replication.

Flanked by the origin of replication and an early P1 promoter, a group of genes were identified that are likely to constitute the replication module of φ31. This is based on the identification of two ORFs with several motifs that show strong similarity to helicases and primases. Five of the deduced proteins (ORF 245, helicase, ORF 150, ORF 268, and primase) located within the putative replication module of φ31 showed strong similarity to a conserved DNA replication module from a group of virulent and temperate S. thermophilus phages, such as φSfi19, φSfi21, φO1205, and φDT1. Besides the high degree of amino acid identity (38 to 58%) to the S. thermophilus homologues, the sizes of the proteins and the topological organization of the corresponding genes were similar, suggesting that S. thermophilus phages and lactococcal phages belonging to the P335 species are closely related. Finally, we observed significant sequence identity and structural similarity between the origin of replication of φ31 and the origin of replication of Sfi21. This is a very significant observation, given that both Lactococcus and S. thermophilus are used extensively in common dairy fermentation environments and one could anticipate opportunities for coevolution between phages infecting these two bacterial species (8).

Efforts to construct an autonomously replicating plasmid were based on cloning of the entire sequence extending from the P1 promoter to a point just downstream of the origin of replication. These efforts were unsuccessful, suggesting that one or more factors are missing from this region that are essential for phage replication. In a recent study, the complete DNA sequence of temperate L. gasseri phage φadh was determined. A 10-kb fragment covering the putative replication module of φadh was sufficient to mediate autonomously replication in both L. gasseri and L. lactis (2). Interestingly, the topological organization within the replication module of φadh was similar to that of φ31. Homologues of ORF 243, helicase, ORF 150, and the primase were identified in the same order in φadh.

Another interesting feature from the promoter and sequence analysis of φ31 was the identification of a typical genetic switch including two divergently oriented promoters and two cognate repressor genes that regulate promoters P1 and P2. Genetic switches are found in temperate phages, where they control the entrance into either the lytic or the lysogenic life cycle. Identification of a cI repressor homologue in the lytic bacteriophage φ31 was unexpected, as the natural function of this protein is to repress the expression of genes required for lytic proliferation. In this regard, it is interesting that gene fusion experiments with promoter constructs expressing cI failed to significantly retard expression of P1, the promoter directed toward cro and the lytic gene functions of phage φ31 (Fig. 7, construct pSMBI30). Whether or not this is a function of the effectiveness of the cI protein or its ability to bind the operator is unknown. To our knowledge, this is the first example of a lytic Lactococcus phage which contains a gene implicated in the establishment of the lysogenic state. Spontaneous deletion mutants of different temperate LAB phages (L. lactis temperate phage BK5-T, S. thermophilus temperate phage φSfi21, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii temperate phage LL-H) that have lost the capacity to lysogenize host cells have been described in the literature (7, 9, 48). These mutants have incurred deletions in a region covering the phage attachment site (attP) and the integrase gene, which both are required to establish lysogeny. The genome organization in temperate bacteriophages is highly conserved, and the genetic requirements (the attP and int genes) for integration are typically located between the lysin gene and the divergently oriented cI gene. In this study, we identified the 3′ end of the lysin gene, but no attachment site or int gene was identified within the 368-bp sequence located between the lysin gene and the cI gene. These data indicate that φ31 evolved from a temperate phage to an obligately lytic phage by deletion of a specific region that abolishes the ability of φ31 to form stable lysogens. As a direct result of this close relationship to temperate phages within the P335 species, the obligately lytic phage φ31 is further capable of acquiring prophage-encoded sequences essential for virulent replication and development (19).

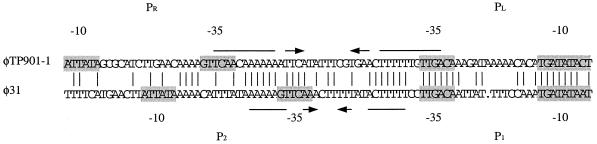

In contrast to the normal situation in temperate phages, where the genetic switch is controlled by a sophisticated regulation mechanism involving differential interactions between the repressor proteins and the operator-binding sites (20, 41, 46, 50), the situation in φ31 seems to be simpler. An example of this high complexity appears in the regulation of the genetic switch from temperate L. lactis phage TP901-1 (46). Despite the high overall similarity between the two repressor proteins of φ31 and the corresponding proteins of TP901-1, the two genetic switches are quite differently regulated. The cI homologue (ORF 4) of TP901-1 was an efficient repressor of both early promoters, whereas the Cro homologue (ORF 5) alone had no effect on either of the two early promoters in TP901-1. In contrast, the cI homologue of φ31 was not an efficient repressor of either P1 or P2 and, interestingly, allowed efficient expression of P1 reading into cro and the DNA replication module. In contrast to TP901-1, the Cro homologue of φ31 efficiently repressed both P1 and P2. Comparison of the DNA sequences of the two early divergent promoter regions of φ31 and TP901-1 showed identity inside the region flanked by the two −35 sequences in the two phages (Fig. 8). While an inverted repeat overlapped both −35 sequences in TP901-1, the equivalent inverted repeat of φ31 only overlapped the −35 sequence of the P2 promoter (cI gene expression). These differences at the DNA level, in addition to the diversity between the repressor proteins, might contribute to the obvious difference in regulation between the two genetic switches of φ31 and TP901-1 and their corresponding virulent and temperate lifestyles.

FIG. 8.

Comparison of the early promoter regions of lytic phage φ31 and temperate phage TP901-1. The −10 and −35 regions of all four promoters are shaded. Vertical lines indicate identical base pairs. Inverted repeats are indicated by horizontal arrows. PL, lytic promoter of TP901-1; PR, lysogenic promoter of TP901-1. The depicted sequence is shown as 5′ to 3′. The TP901-1 sequence included extends from position 3219 to position 3307 in EMBL entry Y14232.

Using the BlastN search tool, we identified several regions within the established DNA sequence that showed very high identity to DNA sequences from the temperate L. lactis phage species P335 and BK5-T. The most interesting identities are located around the lysin and cI genes, further supporting the idea that temperate phages contribute to the appearance of lytic phages in these species (19, 34, 49, 58). The presently available DNA sequence of the φ31 lysin gene exhibits 94% identity to 3′ end of the lysin gene of BK5-T. Three other regions of homology around the lysogenic modules of several temperate lactococcal phages and φ31 were identified. (i) Just downstream of the lysin gene, a 22-bp DNA sequence, which is located in corresponding positions on the BK5-T, r1t, Tuc2009, and φLC3 phage genomes, was identified. This sequence is 100% conserved among the three phages and contains, besides a putative transcription terminator, part of the BK5-T core sequence, which was involved in the formation of two spontaneous BK5-T.H2Δ8 and BK5-T.H2Δ10 deletion mutants (7). (ii) A DNA region with extensive homology to the region located downstream of the attP site and the int gene of BK5-T (93% identity; nucleotides 10518 to 10706 of the published sequence [6]) and r1t (97% identity; nucleotides 33069 to 33183 of the published sequence [66]) was identified adjacent to the 3′ end of the cI gene of φ31. (iii) Finally, a region that spans most of the untranslated cro leader was 97 and 98% identical to DNA sequences located in similar positions of r1t and BK5-T. The homologous DNA sequences identified that flank the lysogenic modules of r1t, BK5-T, and the cI gene of φ31 might, therefore, represent recombination hot spots promoting exchange of lysogenic modules among the phages, consistent with the modular theory of phage evolution proposed by Botstein (3).

More evidence of a close evolutionary relationship between φ31 and temperate phages was provided by the identification of a 952-bp region within the φ31 sequence showing 96% sequence identity to temperate phage r1t. The 952-bp sequence is located in the region encoding ORFs 59 and 188 of φ31, which is adjacent to the region containing the late phage inducible promoter that also exhibited high sequence identity to phage r1t (70)

The accumulating sequencing data and molecular studies of bacteriophages from lactic acid bacteria will certainly lead to a better understanding of phage evolution and provide more insight into the emergence of new virulent phages. This investigation adds to the mounting evidence that virulent members of the P335 species have arisen from temperate ancestors and freely exchange prophage-based sequences under the dynamics of the dairy fermentation environment. This perspective should fuel future efforts to identify P335 sequences in the genomic complement of Lactococcus starter cultures and eliminate them in an effort to the minimize genetic routes that support the appearance and adaptation of new virulent phages.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Southeast Dairy Foods Research Center; Dairy Management, Inc.; Rhodia, Inc.; and USDA NRICGP project 97-35503-4368. S. M. Madsen was supported in part by grants from the Danish Academy for Technical Sciences, the Plasmid Foundation, and Dr. Tech. A. N. Neergaards Foundation.

Many thanks are offered to many colleagues at North Carolina State University for their assistance and hospitality. We thank Evelyn Durmaz for helpful discussions and Pernille Smith for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Paper FSR-00-19 of the Journal Series of the Department of Food Science, North Carolina State University, Raleigh.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alatossava T, Klaenhammer T R. Molecular characterization of three small isometric-headed bacteriophages which vary in their sensitivity to the lactococcal phage resistance plasmid pTR2030. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1346–1353. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.5.1346-1353.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altermann E, Klein J R, Henrich B. Primary structure and features of the genome of the Lactobacillus gasseri temperate bacteriophage phi adh. Gene. 1999;236:333–346. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botstein D. A theory of modular evolution for bacteriophages. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1980;354:484–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb27987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouchard J D, Moineau S. Homologous recombination between a lactococcal bacteriophage and the chromosome of its host strain. Virology. 2000;270:65–75. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyce J D, Davidson B E, Hillier A J. Identification of prophage genes expressed in lysogens of the Lactococcus lactis bacteriophage BK5-T. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4099–4104. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.4099-4104.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyce J D, Davidson B E, Hillier A J. Sequence analysis of the Lactococcus lactis temperate bacteriophage BK5-T and demonstration that the phage DNA has cohesive ends. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4089–4098. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.4089-4098.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyce J D, Davidson B E, Hillier A J. Spontaneous deletion mutants of the Lactococcus lactis temperate bacteriophage BK5-T and localization of the BK5-T attP site. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4105–4109. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.4105-4109.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brussow H, Bruttin A, Desiere F, Lucchini S, Foley S. Molecular ecology and evolution of Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophages. Virus Genes. 1998;16:95–109. doi: 10.1023/a:1007957911848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruttin A, Brussow H. Site-specific spontaneous deletions in three genome regions of a temperate Streptococcus thermophilus phage. Virology. 1996;219:96–104. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruttin A, Desiere F, Lucchini S, Foley S, Brussow H. Characterization of the lysogeny DNA module from the temperate Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophage phi Sfi21. Virology. 1997;233:136–148. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cech T R. Conserved sequences and structures of group I introns: building an active site for RNA catalysis. Gene. 1988;73:259–271. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandry P S, Moore S C, Boyce J D, Davidson B E, Hillier A J. Analysis of the DNA sequence, gene expression, origin of replication and modular structure of the Lactococcus lactis lytic bacteriophage sk1. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:49–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5491926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desiere F, Lucchini S, Bruttin A, Zwahlen M C, Brussow H. A highly conserved DNA replication module from Streptococcus thermophilus phages is similar in sequence and topology to a module from Lactococcus lactis phages. Virology. 1997;234:372–382. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desiere F, Lucchini S, Brussow H. Evolution of Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophage genomes by modular exchanges followed by point mutations and small deletions and insertions. Virology. 1998;241:345–356. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vos W M, Simons G F M. Gene cloning and expression systems in lactococci. In: Gasson M J, de Vos W M, editors. Genetics and biotechnology of lactic acid bacteria. London, United Kingdom: Chapman and Hall; 1994. pp. 52–105. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinsmore P K, Klaenhammer T R. Molecular characterization of a genomic region in a Lactococcus bacteriophage that is involved in its sensitivity to the phage defense mechanism AbiA. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2949–2957. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2949-2957.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djordjevic G M, Klaenhammer T R. A method for mapping phage-inducible promoters for use in bacteriophage-triggered defense systems. Methods Cell Sci. 1998;20:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durmaz E, Klaenhammer T R. A starter culture rotation strategy incorporating paired restriction/modification and abortive infection bacteriophage defenses in a single Lactococcus lactis strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1266–1273. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1266-1273.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durmaz E, Klaenhammer T R. Genetic analysis of chromosomal regions of Lactococcus lactis acquired by recombinant lytic phages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:895–903. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.3.895-903.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engel G, Altermann E, Klein J R, Henrich B. Structure of a genome region of the Lactobacillus gasseri temperate phage phi adh covering a repressor gene and cognate promoters. Gene. 1998;210:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foley S, Lucchini S, Zwahlen M C, Brussow H. A short noncoding viral DNA element showing characteristics of a replication origin confers bacteriophage resistance to Streptococcus thermophilus. Virology. 1998;250:377–387. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forde A, Fitzgerald G F. Bacteriophage defence systems in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:89–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasson M J. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:1–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.1-9.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodrich-Blair H, Scarlato V, Gott J M, Xu M Q, Shub D A. A self-splicing group I intron in the DNA polymerase gene of Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage SPO1. Cell. 1990;63:417–424. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90174-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodrich-Blair H, Shub D A. The DNA polymerase genes of several HMU-bacteriophages have similar group I introns with highly divergent open reading frames. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3715–3721. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.18.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorbalenya A E, Koonin E V. Helicases: amino acid sequence comparisons and structure-function relationships. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1993;3:419–429. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant S G, Jesse J, Bloom F R, Hanahan D. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4645–4649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayes F, Daly C, Fitzgerald G F. Identification of the minimal replicon of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis UC317 plasmid pCI305. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:202–209. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.1.202-209.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill C, Miller L A, Klaenhammer T R. Cloning, expression, and sequence determination of a bacteriophage fragment encoding bacteriophage resistance in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6419–6426. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6419-6426.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill C, Miller L A, Klaenhammer T R. In vivo genetic exchange of a functional domain from a type II A methylase between lactococcal plasmid pTR2030 and a virulent bacteriophage. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4363–4370. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4363-4370.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holo H, Nes I F. High-frequency transformation, by electroporation, of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris grown with glycine in osmotically stabilized media. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:3119–3123. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.12.3119-3123.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Israelsen H, Madsen S M, Vrang A, Hansen E B, Johansen E. Cloning and partial characterization of regulated promoters from Lactococcus lactis Tn917-lacZ integrants with the new promoter probe vector, pAK80. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2540–2547. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2540-2547.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jarvis A W. DNA-DNA homology between lactic streptococci and their temperate and lytic phages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:1031–1038. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.5.1031-1038.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jarvis A W. Bacteriophages of lactic acid bacteria. J Dairy Sci. 1989;72:3406–3428. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jarvis A W, Fitzgerald G F, Mata M, Mercenier A, Neve H, Powell I B, Ronda C, Saxelin M, Teuber M. Species and type phages of lactococcal bacteriophages. Intervirology. 1991;32:2–9. doi: 10.1159/000150179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaneko J, Kimura T, Narita S, Tomita T, Kamio Y. Complete nucleotide sequence and molecular characterization of the temperate staphylococcal bacteriophage phiPVL carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes. Gene. 1998;215:57–67. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kodaira K I, Oki M, Kakikawa M, Watanabe N, Hirakawa M, Yamada K, Taketo A. Genome structure of the Lactobacillus temperate phage phi g1e: the whole genome sequence and the putative promoter/repressor system. Gene. 1997;187:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kullen M J, Klaenhammer T R. Identification of the pH-inducible, proton-translocating F1F0-ATPase (atpBEFHAGDC) operon of Lactobacillus acidophilus by differential display: gene structure, cloning and characterization. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1152–1161. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Labrie S, Moineau S. Multiplex PCR for detection and identification of lactococcal bacteriophages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:987–994. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.3.987-994.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ladero V, Garcia P, Bascaran V, Herrero M, Alvarez M A, Suarez J E. Identification of the repressor-encoding gene of the Lactobacillus bacteriophage A2. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3474–3476. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3474-3476.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ladero V, Garcia P, Alonso J C, Suarez J E. A2 cro, the lysogenic cycle repressor, specifically binds to the genetic switch region of Lactobacillus casei bacteriophage A2. Virology. 1999;262:220–229. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lubbers M W, Waterfield N R, Beresford T P, Le Page R W, Jarvis A W. Sequencing and analysis of the prolate-headed lactococcal bacteriophage c2 genome and identification of the structural genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4348–4356. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4348-4356.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lubbers M W, Schofield K, Waterfield N R, Polzin K M. Transcription analysis of the prolate-headed lactococcal bacteriophage c2. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4487–4496. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4487-4496.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lucchini S, Desiere F, Brussow H. Comparative genomics of Streptococcus thermophilus phage species supports a modular evolution theory. J Virol. 1999;73:8647–8656. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8647-8656.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Madsen P L, Hammer K. Temporal transcription of the lactococcal temperate phage TP901–1 and DNA sequence of the early promoter region. Microbiology. 1998;144:2203–2215. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-8-2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Madsen P L, Johansen A H, Hammer K, Brondsted L. The genetic switch regulating activity of early promoters of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901–1. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7430–7438. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.24.7430-7438.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGrath S, Seegers J F, Fitzgerald G F, van Sinderen D. Molecular characterization of a phage-encoded resistance system in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1891–1899. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.1891-1899.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mikkonen M, Dupont L, Alatossava T, Ritzenthaler P. Defective site-specific integration elements are present in the genome of virulent bacteriophage LL-H of Lactobacillus delbrueckii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1847–1851. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.5.1847-1851.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moineau S, Pandian S, Klaenhammer T R. Evolution of a lytic bacteriophage via DNA acquisition from the Lactococcus lactis chromosome. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1832–1841. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.6.1832-1841.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nauta A, van Sinderen D, Karsens H, Smit E, Venema G, Kok J. Inducible gene expression mediated by a repressor-operator system isolated from Lactococcus lactis bacteriophage r1t. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1331–1341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neve H, Zenz K I, Desiere F, Koch A, Heller K J, Brussow H. Comparison of the lysogeny modules from the temperate Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophages TP-J34 and Sfi21: implications for the modular theory of phage evolution. Virology. 1998;241:61–72. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Sullivan D J, Hill C, Klaenhammer T R. Effect of increasing the copy number of bacteriophage origins of replication, in trans, on incoming-phage proliferation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2449–2456. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2449-2456.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O'Sullivan D J, Klaenhammer T R. Rapid mini-prep isolation of high-quality plasmid DNA from Lactococcus and Lactobacillus spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2730–2733. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2730-2733.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Sullivan D J, Klaenhammer T R. High- and low-copy-number Lactococcus shuttle cloning vectors with features for clone screening. Gene. 1993;137:227–231. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90011-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O'Sullivan D J, Walker S A, West S G, Klaenhammer T R. Development of an expression strategy using a lytic phage to trigger explosive plasmid amplification and gene expression. Biotechnology. 1996;14:82–87. doi: 10.1038/nbt0196-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petersen A, Josephsen J, Johnsen M G. TPW22, a lactococcal temperate phage with a site-specific integrase closely related to Streptococcus thermophilus phage integrases. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7034–7042. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.22.7034-7042.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ptashne M, Backman K, Humayun M Z, Jeffrey A, Maurer R, Meyer B, Sauer R T. Autoregulation and function of a repressor in bacteriophage lambda. Science. 1976;194:156–161. doi: 10.1126/science.959843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Relano P, Mata M, Bonneau M, Ritzenthaler P. Molecular characterization and comparison of 38 virulent and temperate bacteriophages of Streptococcus lactis. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:3053–3063. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-11-3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schouler C, Ehrlich S D, Chopin M C. Sequence and organization of the lactococcal prolate-headed bIL67 phage genome. Microbiology. 1994;140:3061–3069. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-11-3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sing W D, Klaenhammer T R. A strategy for rotation of different bacteriophage defenses in a lactococcal single-strain starter culture system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:365–372. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.2.365-372.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stanley E, Fitzgerald G F, Le Marrec C, Fayard B, van Sinderen D. Sequence analysis and characterization of phi O1205, a temperate bacteriophage infecting Streptococcus thermophilus CNRZ1205. Microbiology. 1997;143:3417–3429. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-11-3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Terzaghi B E, Sandine W E. Improved media for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1975;29:807–813. doi: 10.1128/am.29.6.807-813.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thunell R K, Sandine W E. Phage-insensitive, multiple strain starter approach to cheddar cheesemaking. J Dairy Sci. 1981;64:2270–2277. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tremblay D M, Moineau S. Complete genomic sequence of the lytic bacteriophage DT1 of Streptococcus thermophilus. Virology. 1999;255:63–76. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Sinderen D, Karsens H, Kok J, Terpstra P, Ruiters M H, Venema G, Nauta A. Sequence analysis and molecular characterization of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage rlt. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1343–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Venema G, Kok J, van Sinderen D. From DNA sequence to application: possibilities and complications. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:3–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walker J E, Saraste M, Runswick M J, Gay N J. Distantly related sequences in the α- and β-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Walker S A, Klaenhammer T R. Molecular characterization of a phage-inducible middle promoter and its transcriptional activator from the lactococcal bacteriophage φ31. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:921–931. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.921-931.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Walker S A, Dombroski C S, Klaenhammer T R. Common elements regulating gene expression in temperate and lytic bacteriophages of Lactococcus species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1147–1152. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.1147-1152.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]