Abstract

Preterm birth, the leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality, is associated with increased risk of short- and long-term adverse outcomes. For women identified as at risk for preterm birth attributable to a sonographic short cervix, the determination of imminent delivery is crucial for patient management. The current study aimed to identify amniotic fluid (AF) proteins that could predict imminent delivery in asymptomatic patients with a short cervix. This retrospective cohort study included women enrolled between May 2002 and September 2015 who were diagnosed with a sonographic short cervix (< 25 mm) at 16–32 weeks of gestation. Amniocenteses were performed to exclude intra-amniotic infection; none of the women included had clinical signs of infection or labor at the time of amniocentesis. An aptamer-based multiplex platform was used to profile 1310 AF proteins, and the differential protein abundance between women who delivered within two weeks from amniocentesis, and those who did not, was determined. The analysis included adjustment for quantitative cervical length and control of the false-positive rate at 10%. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was calculated to determine whether protein abundance in combination with cervical length improved the prediction of imminent preterm delivery as compared to cervical length alone. Of the 1,310 proteins profiled in AF, 17 were differentially abundant in women destined to deliver within two weeks of amniocentesis independently of the cervical length (adjusted p-value < 0.10). The decreased abundance of SNAP25 and the increased abundance of GPI, PTPN11, OLR1, ENO1, GAPDH, CHI3L1, RETN, CSF3, LCN2, CXCL1, CXCL8, PGLYRP1, LDHB, IL6, MMP8, and PRTN3 were associated with an increased risk of imminent delivery (odds ratio > 1.5 for each). The sensitivity at a 10% false-positive rate for the prediction of imminent delivery by a quantitative cervical length alone was 38%, yet it increased to 79% when combined with the abundance of four AF proteins (CXCL8, SNAP25, PTPN11, and MMP8). Neutrophil-mediated immunity, neutrophil activation, granulocyte activation, myeloid leukocyte activation, and myeloid leukocyte-mediated immunity were biological processes impacted by protein dysregulation in women destined to deliver within two weeks of diagnosis. The combination of AF protein abundance and quantitative cervical length improves prediction of the timing of delivery compared to cervical length alone, among women with a sonographic short cervix.

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Immunology, Systems biology, Biomarkers, Health care, Medical research, Molecular medicine, Risk factors

Introduction

Preterm birth, the leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality1–7, is associated with an increased risk of short- and long-term health outcomes for neonates who survive8–13. Worldwide, preterm birth affects about 15 million babies annually, which accounts for the 11% global preterm birth rate3, 14, 15. In the United States, the rate of preterm birth has been approximately 10% since 2018, and this number remains high as compared to the rate observed in other developed countries3, 16, 17. The rate of preterm birth is even higher in several developing countries3, 4, 18 and contributes to substantial costs related to healthcare services19–22.

The identification of women at risk of preterm birth is central to the development of effective, preventive interventions aimed to reduce the potential negative effects at birth or later in life7, 23–26. Although various strategies to screen women at risk of preterm birth have been proposed by investigators, more accurate methods are yet to be developed, given the multifactorial causes leading to this syndrome7, 27, 28. Risk factors for preterm birth include advanced maternal age29, greater maternal body mass index30, 31, substance use during pregnancy (tobacco or alcohol use)32, 33, exposure to violence (physical or emotional)34–36, and psychosocial stress37, 38. In addition, clinical and obstetrical characteristics, such as a history of previous preterm birth39–41, gestational diabetes and chronic hypertension42, short inter-pregnancy interval43, 44, infection and inflammation45–50, genetic factors51–54, and environmental pollutants55–59, have also been linked to an increased risk of preterm birth. Race/ethnicity-related disparities in preterm birth rates were also reported60–62.

The traditional approach in the screening of imminent preterm birth involves a combination of maternal and obstetrical characteristics63–65. However, the detection rate of this approach is low (sensitivity ~ 20% and positive predictive value ~ 30%)63. Molecular biomarkers, such as fetal fibronectin in cervico-vaginal secretions66–69 and increased concentrations of interleukin (IL)-6 in amniotic fluid (AF)70–73 have also been associated with a higher risk of preterm birth. Novel proteomics platforms and bioinformatics algorithms have enabled a refined characterization of the AF proteome27, 74–87 for the prediction of several pathological conditions in pregnancy88–90, including preterm birth23, 91–94. For example, Lee et al.95 showed that AF cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases in combination with clinical risk factors improve the prediction of early preterm birth compared to a single protein or each clinical factor alone. Other investigators suggested a combination of multiple markers that include those profiled in AF and cervical fluid96–98.

In addition to biochemical markers, a powerful predictor of preterm birth is a transvaginal sonographic short cervix99–106, and women at risk can benefit from vaginal progesterone treatment107–111. We have proposed that the sensitivity of cervical length screening can be further improved by using a customized approach that accounts for maternal characteristics (weight, height, and parity) and exact gestational age at screening112. For women identified as at risk attributable to a short cervix at any time during the second or third trimester, it would be important, to know whether delivery is imminent. Therefore, in this study, we sought to identify AF proteins that can predict imminent preterm delivery in women with a sonographic short cervix.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

This was a retrospective analysis of data collected from pregnant women who were enrolled in a longitudinal biomarker study involving universal cervical length measurement at the Center for Advanced Obstetrical Care and Research of the Perinatology Research Branch of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the Detroit Medical Center, and Wayne State University (Detroit, MI, USA). Briefly, pregnant women were enrolled between 6 and 22 weeks of gestation and followed until delivery. Exclusion criteria included women who had the following diagnosis at the time of recruitment: preterm labor, preterm premature rupture of the membranes, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, active vaginal bleeding, multifetal gestation, and serious medical illness such as renal insufficiency, congestive heart disease, chronic respiratory insufficiency, etc. The protocol called for sonographic cervical length in the midtrimester followed by measurements every four weeks until 24 weeks of gestation, then every two weeks until delivery. When the cervical length measured was 25 mm or less, patients were sent to the obstetrical triage area for evaluation and counseling regarding risks of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation and preterm birth. Treatment with antibiotics were shown successful in a subset of patients with cervical insufficiency and intra-amniotic inflammation113, 114. The decision to offer amniocentesis was at the discretion of treating physicians.

The techniques for sonographic assessments of the short cervix and amniotic fluid sample collection were described in previous reports112, 115, 116. We retrospectively selected women with a singleton pregnancy and a sonographic short cervix (≤ 25 mm) between 16 and 32 weeks of gestation who had a transabdominal amniocentesis performed within two days of the cervical length measurement. Only cases without clinical signs of infection or labor at the time of amniocentesis were included. The primary indication for amniocentesis in this group of asymptomatic patients was to rule out intra-amniotic infection/inflammation due to a short cervix. For a subset of these patients, fetal karyotype and fetal lung maturity testing were also performed. Additional exclusion criteria for this study were labor induction for any reasons within two weeks of the amniocentesis, a positive AF culture for micro-organisms, abnormal fetal karyotypes or chromosomal microarray, and structural fetal anomalies. Participants in the study were recruited between May 2002 and September 2015, and all provided informed written consent prior to the collection of samples and images. The use of the data collected (demographic or clinical information, images, and samples) for research purposes was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of Wayne State University and the Institutional Review Board of NICHD. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Proteomics profiling

The concentration of 1,310 proteins in AF samples was quantified by using the SOMAmer (Slow Off-rate Modified Aptamers) platform and its reagents, and proteomics profiling was performed by Somalogic, Inc. (Boulder, CO, USA), as described in previous publications117–119. Briefly, AF samples were diluted and then incubated with a mixture of SOMAmers on streptavidin-coated beads. Next, the beads were washed to remove all unbounded proteins and other matrix constituents, and proteins that remained bound to their cognate SOMAmer reagents were tagged with an NHS-biotin reagent. Pure cognate-SOMAmer complexes and unbound SOMAmer reagents were released from streptavidin beads by ultraviolet light that cleaved the photo-cleavable linker used to quantitate protein. The photo-cleavage eluate was separated from the beads and then incubated with a second streptavidin-coated bead. The free SOMAmer reagents were then removed during subsequent washing steps. In the final elution step, protein-bound SOMAmer reagents were released from their cognate proteins by using denaturing conditions. SOMAmer reagents were then quantified by hybridization to custom DNA microarrays. The cyanine-3 signal from the SOMAmer reagent was detected on the microarrays.

Statistical analyses

Demographic data analysis

The demographic and clinical characteristics were compared by using Wilcoxon-signed rank tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. A p-value < 0.05 for the differences between the groups was considered statistically significant.

Proteomic data analysis

To identify AF protein dysregulation that can be informative about the timing of delivery, we fit linear models on log2-transformed relative fluorescence unit (RFU) values, using an explanatory variable for the delivery group: within two weeks (imminent delivery) vs. greater than two weeks until delivery. To account for the residual information that quantitative cervical length measurement may provide, we included cervical length as a covariate in the linear models. The significance of the group differences was assessed via moderated t-tests. An advantage of the moderate t-test, as contrasted with the standard t-test, is that it borrows information across the different proteins to derive more robust estimates of protein data variance120, and it has also been shown to improve the selection of predictors for omics data-based multi-variate predictive models121–123. Protein p-values were adjusted for multiple testing, and the false-positive discovery rate was controlled at the 10% level (q-value < 0.1). The linear models were fit by using the limma package in R/Bioconductor124.

Logistic regression models were also implemented to determine the odds of imminent delivery associated with a two-fold change in protein abundance, while adjusting for cervical length. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was calculated to determine whether protein data improves the prediction of imminent delivery as compared to cervical length alone. Combinations of up to four proteins were also evaluated by using multivariate logistic regression and the AUC was determined. In addition, Kaplan–Meier survival curves based on the interval from amniocentesis to delivery were compared between patients with a risk score above and those with a risk score below a cut-off value corresponding to a 10% false-positive rate.

To identify biological processes overrepresented in the list of proteins associated with imminent delivery, we performed a Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis with the clusterProfiler package125 in R/Bioconductor. The enrichment analyses also involved control for the false-positive discovery rate at 10% level. Visualization of the abundance of significant protein profiles was performed by using the heatmap function in the ComplexHeatmap package126.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The study included 90 women diagnosed with a sonographic short cervix (< 25 mm) during the second or third trimester. Of this group, 24 women delivered within two weeks from amniocentesis (n = 24) and the remaining 66 women delivered after two weeks from amniocentesis (n = 66). The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1, and the gestational ages at amniocentesis in both groups are depicted in Figure S1. The two groups were similar with respect to gestational age at amniocentesis, maternal age, weight, body mass index, race, parity, and history of preterm birth (p > 0.05). However, cervical length (median 5 vs. 15 mm, p < 0.001), gestational age at delivery (median 24.2 vs. 38.7 weeks, p < 0.001), and birthweight (median 651 vs. 2985 g, p < 0.001) were lower in women who delivered within two weeks compared to those who did not. In addition, neonates delivered within two weeks from amniocentesis had a significantly higher frequency of an Apgar score < 7 at 5 min [56.57% (13/23) vs. 7.7% (5/65), p < 0.001] and of admission to a neonatal intensive care unit [62.5% (15/24) vs. 13.6% (9/66), p < 0.001], compared to neonates whose delivery occurred after two weeks from amniocentesis. The presence of severe acute histologic chorioamnionitis was also more frequent among the women who delivered within two weeks of amniocentesis [81.2% (13/16) vs. 8.7% (4/46), p < 0.001]. Among the women who delivered within two weeks of amniocentesis, 50% (12/24) had intra-amniotic inflammation, indicated by an elevated AF concentration of IL-6 (IL-6 ≥ 2.6 ng/mL) compared to 7.6% (5/66) of those who delivered more than two weeks after an amniocentesis. Of note, the concentrations of IL-6 measured by ELISA were highly correlated to the relative fluorescence measures derived by the aptamer platform (Spearman’s correlation 0.89, p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristics | Delivery at ≤ 2 weeks (n = 24) | Delivery at > 2 weeks (n = 66) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 22.5 (19–32.2) | 24 (21–26) | 0.993 |

| Height (cm) | 160 (154.3–163.2) | 162.6 (157.5–167.6) | 0.047 |

| Weight (kg) | 69.2 (61–78.9) | 77.1 (57.9–89.8) | 0.404 |

| Body mass index | 28.7 (23.7–30.6) | 28.2 (21.6–34.2) | 0.898 |

| Race (African–American) | 87.5 (21/24) | 80.3 (53/66) | 0.544 |

| Tobacco use | 12.5 (3/24) | 22.7 (15/66) | 0.379 |

| Alcohol use | 0 (0/24) | 3.1 (2/64) | |

| Nulliparous | 54.2 (13/24) | 42.4 (28/66) | 0.348 |

| History of preterm birth | 29.2 (7/24) | 24.2 (16/66) | 0.785 |

| Cervical length (mm) | 5.5 (0–10.8) | 15 (10–19.8) | 0.001 |

| Cervical dilation (cm) | 1.00 (0.00–1.75)a | 0.5 (0.00–1.00)b | 0.07 |

| Progesterone treatment | 4.2 (1/24) | 16.7 (11/66) | 0.17 |

| Indications for amniocentesis | |||

| Detection of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation | 95.8 (23/24) | 98.5 (65/66) | 0.464 |

| Karyotyping | 25 (6/24) | 6.1 (4/66) | 0.02 |

| Polyhydroamnios | 0 (0/24) | 1.5 (1/66) | 1 |

| Fetal lung maturity | 4.2 (1/24) | 0 (0/66) | 0.267 |

| Gestational age at amniocentesis (weeks) | 23 (20.4–25.5) | 24.5 (22.2–27.6) | 0.081 |

| Gestational age at cervical length measurement (weeks) | 23 (20.4–25.5) | 24.5 (22.1–27.6) | 0.082 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 24.2 (21.5–27) | 38.7 (36.2–39.4) | < 0.001 |

| Preterm delivery | 100 (24/24) | 27.3 (18/66) | < 0.001 |

| Baby weight (g) | 650.5 (428.2–945) | 2985 (2387–3364) | < 0.001 |

| Cesarean delivery | 12.5 (3/24) | 24.2 (16/66) | 0.381 |

| Fetal sex (male) | 43.5 (10/23) | 60 (39/65) | 0.223 |

| Apgar score < 7 at 5 min after delivery | 56.5 (13/23) | 7.7 (5/65) | < 0.001 |

| NICU Admission | 62.5 (15/24) | 13.6 (9/66) | < 0.001 |

| Severe histologic chorioamnionitis | 81.2 (13/16) | 8.7 (4/46) | < 0.001 |

| Severe funisitis | 15.4 (2/13) | 2.2 (1/45) | 0.123 |

| IL-6 ≥ 2.6 ng/mL | 50 (12/24) | 7.6 (5/66) | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as median (IQR) for continuous and % (n/N) for categorical variables. P-values calculated by Wilcoxon-signed rank tests and Fisher’s exact tests. Note, data were missing for select variables presented in the Table. NICU: neonatal intensive care unit.

aMissing one datum.

bMissing 7 data points.

Differential protein abundance predictive of preterm delivery within two weeks from amniocentesis

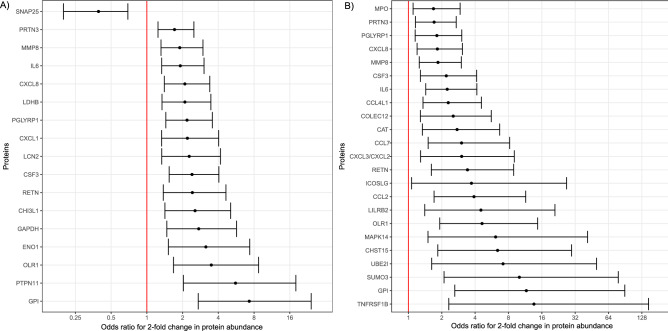

Of the 1,310 proteins profiled in AF, 17 were differentially abundant in women destined to deliver within two weeks of amniocentesis, independently of the cervical length (adjusted p-value < 0.10). A higher abundance of Synaptosome Associated Protein 25 (SNAP25) in AF was associated with lower odds of an earlier delivery (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 0.39) (Fig. 1A). By contrast, the risk of preterm birth within two weeks of amniocentesis increased with the higher abundance of the following proteins: Glucose-6-Phosphate Isomerase (GPI), Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Non-receptor type 11 (PTPN11), Oxidized Low-density Lipoprotein Receptor 1 (OLR1), Enolase 1 (ENO1), Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH), Chitinase-3-like protein 1 (CHI3L1), Resistin (RETN), Colony-Stimulating Factor 3 (CSF3), Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin-2 (LCN2), C-X-C motif ligand 1 (CXCL1) and C-X-C motif ligand 8 (CXCL8), Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein 1 (PGLYRP1), Lactate Dehydrogenase B (LDHB), IL6, Matrix Metalloproteinase-8 (MMP8), and Proteinase 3 (PRTN3) (adjusted OR > 1.5). Of note, for all 17 proteins the significance p-value would be < 0.05 after adjusting for the secondary indication of amniocentesis, i.e. karyotype testing, which was slightly more frequent in women who delivered with two weeks (Table 1). This suggests that this confounding covariate was not a driver of the differential protein abundance observed herein. Therefore, we have attributed the proteomic differences observed to the pathophysiology leading to delivery within two weeks from amniocentesis.

Figure 1.

Odds ratio (and 95% confidence intervals) for the association between amniotic fluid proteins and imminent delivery. (A) Odds ratios for delivery within two weeks and (B) within one week. Odds ratios are adjusted for quantitative cervical length. The odd-ratios are calculated for a two-fold change in protein abundance. Alpha-enolase (ENO1), C–C motif chemokine 2 (CCL2), C–C motif chemokine 4-like (CCL4L1), C–C motif chemokine 7 (CCL7), C-X-C motif ligand 8 (CXCL8), Carbohydrate sulfotransferase 15 (CHST15), Catalase (CAT), Chitinase-3-like protein 1 (CHI3L1), Collectin-12 (COLEC12), Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI), Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (CSF3), Gro-beta/gamma (CXCL3/CXCL2), Growth-regulated alpha protein (CXCL1), ICOS ligand (ICOSLG), Interleukin-6 (IL6), L-lactate dehydrogenase B chain (LDHB), Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor subfamily B member 2 (LILRB2), Matrix Metalloproteinase-8 (MMP8), Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 (MAPK14), Myeloperoxidase (MPO), Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (LCN2), Oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (OLR1), Proteinase 3 (PRTN3), Peptidoglycan recognition protein 1 (PGLYRP1), Resistin (RETN), Small ubiquitin-related modifier 3 (SUMO3), SUMO-conjugating enzyme UBC9 (UBE2I), Synaptosomal-associated protein 25 (SNAP25), Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1B (TNFRSF1B), Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 11 (PTPN11).

Differential protein abundance predictive of delivery within one week from amniocentesis

When comparing the protein abundance between women who delivered within one week from the amniocentesis (n = 9) to the group of women who delivered after one week (n = 81), we have identified 23 proteins with significant differential abundance after controlling the false discovery rate at the 10% level (q < 0.1). The cervical length adjusted ORs for the association of between a two-fold change in protein abundance and delivery within one week from amniocentesis are presented in Fig. 1B. Of note, among the 23 proteins that had higher abundance in the group of women who delivered within one week, nine were also identified as increased in women who delivered within two weeks from amniocentesis. Moreover, the point estimates of odds ratios for delivery with One week were larger than those for delivery within two weeks, suggesting a dose response relation between the timing of delivery and protein abundance changes.

Prediction of delivery within two weeks from amniocentesis by cervical length and amniotic fluid proteins

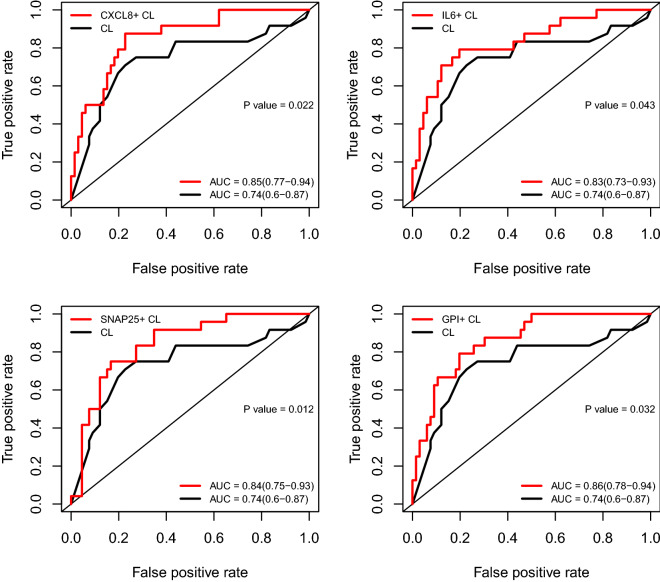

Although all women had an amniocentesis after diagnosis with a short cervix, the exact cervical length (quantitative assessment) was still predictive of delivery within two weeks from amniocentesis, and shorter cervical lengths were associated with increased risk (AUC = 0.74) (Fig. 2). The addition of data from one protein at a time led to improvements in the AUC that ranged from 4% to 12% depending on the specific protein (Fig. 2). The greatest improvement in the AUC statistic, compared to cervical length alone, was noted for GPI (AUC 0.86 vs 0.74), followed by CSF3, CXCL8, SNAP25, GAPDH, PGLYRP1, IL6, OLR1, and LDHB (p < 0.05 for all). Of note, the predictive value of the combination of cervical length and ELISA-based IL-6 (AUC = 0.8) was similar to that of cervical length and aptamers-based multiplex IL-6 (AUC = 0.83) (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

ROC curves for predicting imminent delivery. Each panel compares prediction by cervical length alone and models that combine cervical length with protein abundance. AUC: area under the ROC curve and 95% confidence interval. CL: cervical length.

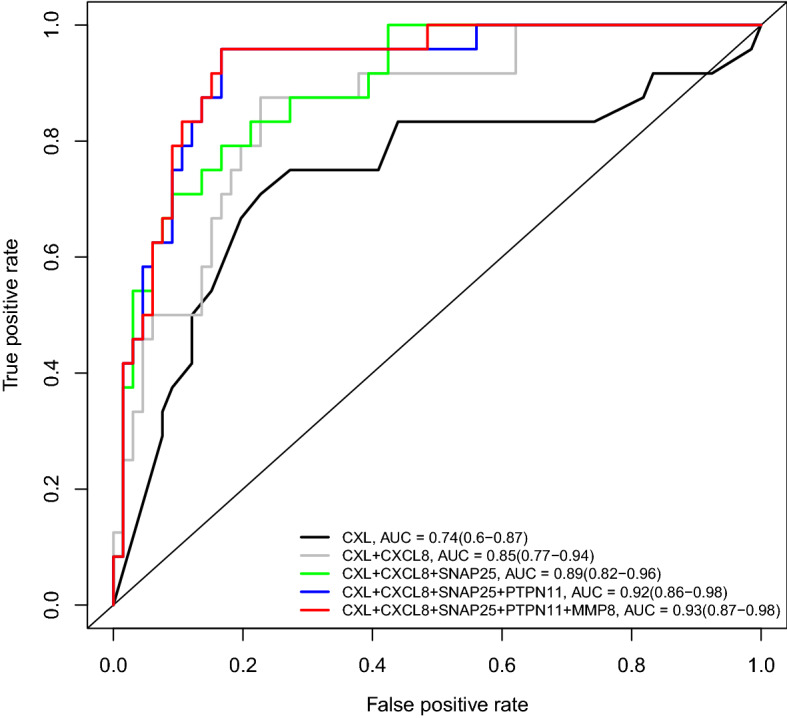

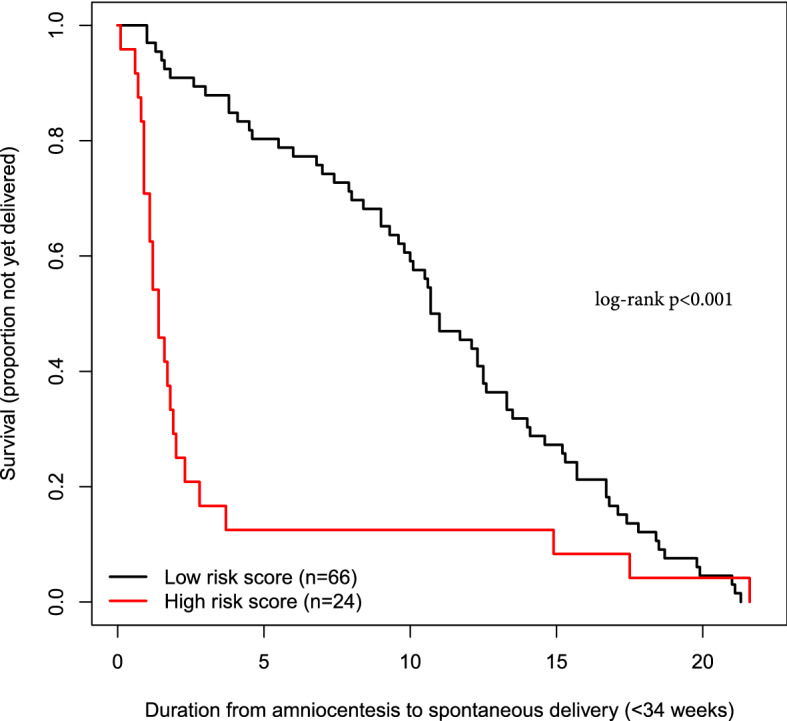

Combinations of the quantitative cervical length with up to four proteins further increased performance, reaching an AUC = 0.93 for the combination of CXCL8, MMP8, SNAP25, and PTPN11 (Fig. 3). The sensitivity, at a 10% false-positive rate, for the prediction of imminent delivery by the quantitative cervical length alone was 38%, yet it increased to 79% in combination with these four proteins. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing duration to delivery between patients with a risk score above and those with a risk score below the risk cut-off value corresponding to a 10% false-positive rate are shown in Fig. 4. Patients with a risk score above the 10% false-positive rate cut-off value had a significantly shorter time to delivery compared to those with a risk score below the cut-off value [median: 1.4 (1.1–2.0) vs. 10.9 (9.8–13.3) weeks; log-rank p < 0.001].

Figure 3.

Combinations of multiple proteins for improving prediction of imminent delivery. AUC: area under the ROC curve and 95% confidence interval. CL: cervical length.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with a risk score above and those with a risk score below the cut-off value corresponding to a 10% false positive rate. The risk scores are determined by quantitative cervical length and four proteins (CXCL8, SNAP25, PTPN11, MMP8).

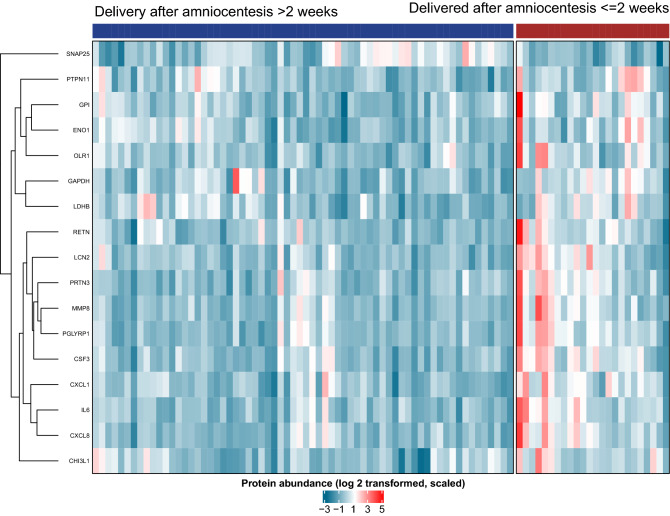

Given the similar predictive value among several proteins, we applied cluster analysis and identified two main sets of proteins with higher abundance in pregnant women destined to deliver within two weeks of amniocentesis (Fig. 5). Cluster #1 was dominated by pro-inflammatory cytokines, including some previously associated with a high risk of preterm birth: MMP8, PGYRP1, PRTN3, CSF3, LCN2, RETN, IL6, CXCL8, CXCL1, and CHI3L1. Member proteins of cluster #2 were ENO1, GPI, OLR1, PTPN11, LDHB, and GAPDH. One protein, SNAP25, formed a cluster by itself, as it was negatively correlated with the risk of imminent delivery.

Figure 5.

Clustered heatmap of protein data. The 17 proteins that were dysregulated in women destined for imminent delivery independent of cervical length were clustered using hierarchical clustering with correlation distance. Higher abundance of amniotic fluid protein levels is represented by a darker red color.

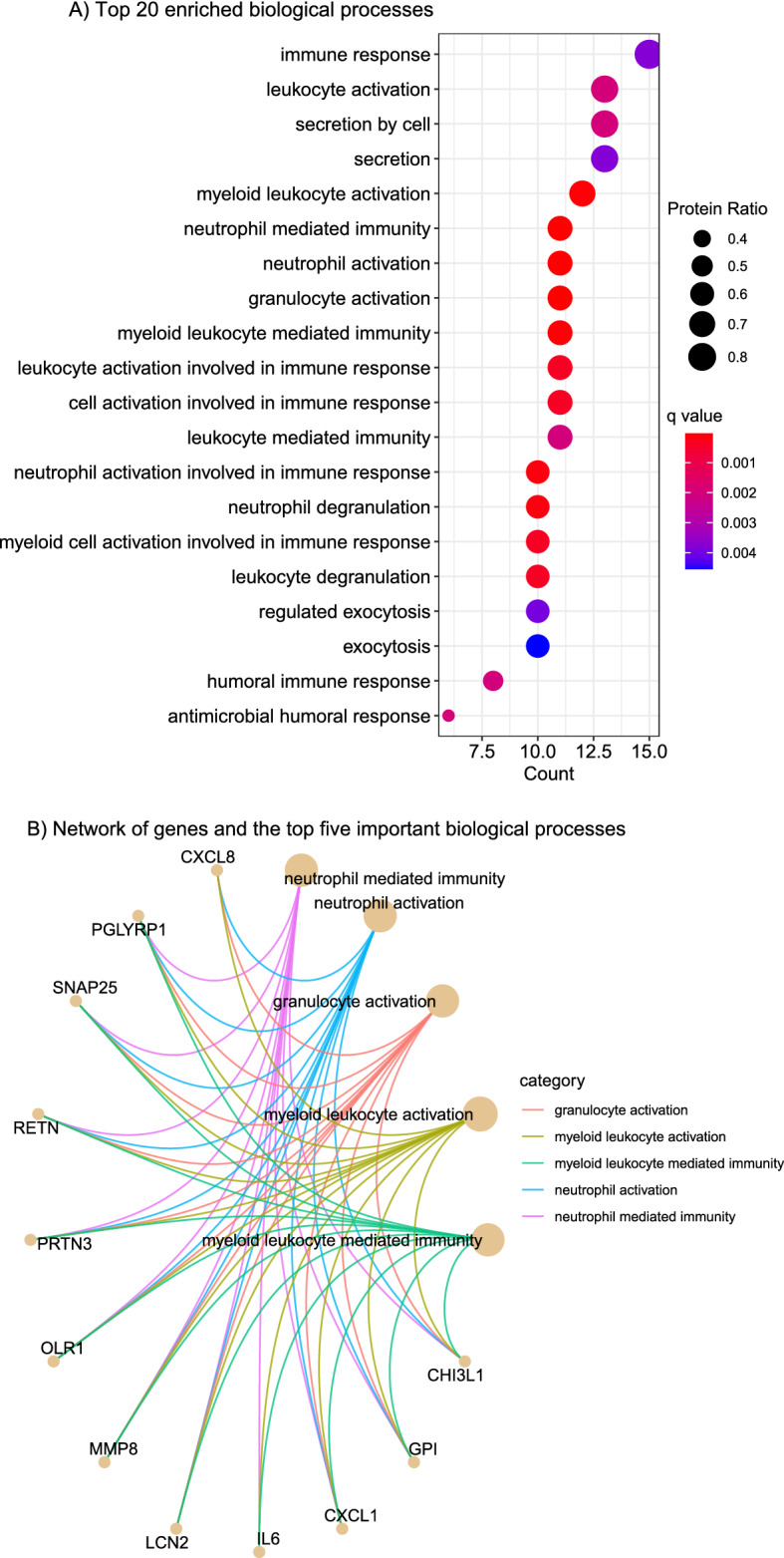

Gene ontology biological processes associated with imminent delivery

Enrichment analysis identified 23 biological processes associated with earlier preterm delivery after amniocentesis (q < 0.05, Table S1), which included neutrophil-mediated immunity, neutrophil activation, granulocyte activation, myeloid leukocyte activation, and myeloid leukocyte-mediated immunity (Fig. 6A,B).

Figure 6.

Gene ontology enrichment analysis of amniotic fluid proteins dysregulated with imminent delivery. Top 20 enriched biological processes (A) and a network representation of proteins involved in the top five enriched biological processes (B). Protein Ratio represents the number of proteins significantly dysregulated per the total number of proteins in a particular biological process. Darker red/blue indicate high/low enrichment, respectively. The size of the dots corresponds to the protein ratio represented by each biological process.

Discussion

Principal findings of the study

(1) The AF proteins predicted imminent preterm delivery beyond what was previously possible when using only quantitative cervical length in women with a short cervix, a group already considered at risk for preterm birth (AUC = 0.93 for a combination of four proteins vs AUC = 0.74 for quantitative cervical length alone); (2) the sensitivity at a fixed false-positive rate of 10% for prediction of delivery within two weeks by a short cervix alone was 38%, yet it increased to 79% in combination with up to four AF proteins; and (3) neutrophil-mediated immunity, neutrophil activation, granulocyte activation, myeloid leukocyte activation, and myeloid leukocyte-mediated immunity were among the top biological processes associated with differentially abundant proteins in women who delivered within two weeks from an amniocentesis with a diagnosis of a short cervix.

Our findings in the context of what is already known

Herein, we have assessed the value of AF proteins for the prediction of imminent delivery in pregnant women with a sonographic short cervix. Typically defined as cervical length < 25 mm, a short cervix was shown to be associated with a higher risk of preterm birth than those with a long cervix at any time during preterm gestation. For the 8–31 weeks interval, the 25 mm cut-off value was more extreme (lower) than the 10th percentile among asymptomatic women with term delivery in this population112. Studies from our group have shown that the rate of intra-amniotic infection and inflammation are substantial among women with a short cervix115, 127, 128. Women with a short cervix are already at risk for preterm birth; hence, it is important for patient management to distinguish those destined for imminent delivery. For example, women at risk of delivery within one week from amniocentesis may benefit from the administration of antenatal steroids to improve fetal lung maturity. A unique feature of this study, which confers predictive value, is that the data had been collected prior to any eventual symptoms of preterm labor.

Previous studies have reported that an elevated concentration of IL-6 in the maternal circulation increases the risk for preterm birth94, 98, 129–131. Intra-amniotic inflammation, defined as IL-6 ≥ 2.6 ng/mL71, is a known risk factor for preterm labor and delivery70, 72, 91, 116, 132–136. Increased concentration of IL-6 in cervico-vaginal fluid has also been implicated in women who delivered preterm137, 138. Similarly, a sonographic short cervix is also a risk factor for preterm delivery116, 139. However, few studies have assessed the value of combining AF IL-6 concentrations with cervical length measurement for the prediction of spontaneous preterm birth97. In the current study, we demonstrated that the AF IL-6 concentration adds predictive value to the quantitative cervical length for the prediction of imminent preterm birth in asymptomatic pregnant women with a sonographic short cervix. The same finding holds for MMP8, which is in agreement with previous studies that have linked MMP8 to intra-amniotic infection/inflammation91, 135, 140–144, a causal pathway leading to preterm birth145–156.

Among the family of C-X-C motif chemokines, we observed a significant increase of CXCL1 and CXCL8 levels in patients destined to deliver within two weeks of amniocentesis. The most predictive of these proteins, CXCL8, is also known as IL-8157, 158. We have shown that an abundance of CXCL8 in AF combined with quantitative cervical length improves the prediction of preterm birth as compared to cervical length alone (AUC = 0.85 vs. 0.74, p = 0.022). Several prior studies have related an increased abundance of CXCL8 to an activation of the innate immune system in response to microbial infection/inflammation48, 50, 159–161, while others have argued that such elevation of CXCL8 is physiological as well, resulting from molecular changes in preparation for labor162–165. Of note, increased CXCL8 was also reported in cervico-vaginal fluid of women with preterm delivery166.

The use of multiple biomarkers seems imperative in the overall goal to improve the prediction of preterm birth, given the heterogeneity of these conditions and the multiple causal pathways95–98. In line with these studies, we combined quantitative cervical length with multiple AF proteins (CXCL8, MMP8, PTPN11, and SNAP25) and found a significant improvement in the AUC (AUC = 0.93 for the combined markers vs. AUC = 0.74 for cervical length alone, p = 0.006).

A possible role for neutrophil-mediated immunity in the intra-amniotic inflammatory response observed in pregnant women diagnosed with a short cervix

Neutrophils represent a primary cellular component of innate immunity that protects against microorganisms invading the amniotic cavity through an array of host defense mechanisms167, which may include phagocytosis168, the release of antimicrobial products and cytokines75, 169–178, and the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps178–180. Yet, neutrophils also form a physiological component of the AF cellular repertoire throughout pregnancy181; therefore, they are present in women diagnosed with a short cervix182. Herein, we found that biological processes, such as neutrophil-mediated immunity, neutrophil activation, granulocyte activation, myeloid leukocyte activation, and myeloid leukocyte-mediated immunity, were impacted by protein differential abundance in women who delivered within two weeks of the diagnosis of a short cervix. This finding suggests that AF neutrophils may undergo enhanced activation in women with a short cervix destined to deliver earlier preterm, either as a mechanism in response to bacterial products or “danger signal” in cases of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation115. However, further investigation is required to elucidate the participation of AF neutrophils in the inflammatory processes leading to earlier preterm delivery in women with a short cervix.

Strength and limitations

This is the first study providing a comprehensive evaluation of AF proteins for the prediction of imminent delivery among asymptomatic pregnant women diagnosed with a sonographic short cervix. Some of the AF proteins we identified in the present study (GPI, PTRN11, OLR1, ENO1, GAPDH, CHI3L1, CSF3, LCN2, PGLYRP1, LDHB, PRTN3, and SNAP25) have not been widely explored in previous studies; therefore, they could provide additional insight into the discovery of biomarkers for further understanding of the pathophysiologic pathways leading to preterm birth23. Furthermore, the results of this study contribute to the growing interest in the use of multiple markers to predict preterm birth183. Our study demonstrates that when an asymptomatic patient presents with a sonographic short cervix between 16 and 32 weeks of gestation, specific AF proteins provide additional predictive power for identifying women at risk of imminent delivery (e.g. within 1 or 2 weeks), relative to cervical length alone. Limitations of this study are attributable to the timing of cervical length assessment and amniocentesis being within two days of each other, the limited power for assessing multi-variate prediction of delivery within one week of amniocentesis, and missing detailed obstetrical history such as type of prior preterm term birth and cervical surgery.

Conclusions

Amniotic fluid protein abundance is predictive of imminent delivery among asymptomatic women with a sonographic short cervix. The combination of AF proteins and quantitative cervical length measurement provides improved prediction of the timing of delivery compared to cervical length measurement alone, and this finding could have implications for patient management.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

A.L.T. and R.R. designed the study. D.W.G., B.D. and A.L.T. performed data analysis. D.W.G., A.L.T., N.G-L., J.G. and R.R. wrote the manuscript. G.B., B.D., E.J., S.M.B., D.G., M.B., M.S., R.D.P., C.P., F.G., T.C. provided feedback and suggestions for edits.

Funding

This research was supported, in part, by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Obstetrics and Maternal–Fetal Medicine, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH/DHHS); and, in part, with Federal funds from NICHD/NIH/DHHS under Contract No. HHSN275201300006C. Dr. Romero has contributed to this work as part of his official duties as an employee of the United States Federal Government. Maureen McGerty (Wayne State University) is also acknowledged for proofreading and editing the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Roberto Romero, Email: prbchiefstaff@med.wayne.edu.

Adi L. Tarca, Email: atarca@med.wayne.edu

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-15392-3.

References

- 1.Goldenberg R, et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371(9606):75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu L, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: An updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385(9966):430–440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blencowe H, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: A systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012;379:2162–2172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chawanpaiboon S, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: A systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob. Health. 2019;7(1):e37–e46. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones EO, Liew ZQ, Rust OA. The short cervix: A critical analysis of diagnosis and treatment. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2020;47(4):545–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iams JD, Berghella V. Care for women with prior preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;203(2):89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm labor: One syndrome, many causes. Science. 2014;345(6198):760–765. doi: 10.1126/science.1251816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):261–269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong Y, Yu JL. An overview of morbidity, mortality and long-term outcome of late preterm birth. World J. Pediatr. 2011;7(3):199–204. doi: 10.1007/s12519-011-0290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mwaniki MK, et al. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes after intrauterine and neonatal insults: A systematic review. Lancet. 2012;379(9814):445–452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61577-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luu TM, Rehman Mian MO, Nuyt AM. Long-term impact of preterm birth: Neurodevelopmental and physical health outcomes. Clin. Perinatol. 2017;44(2):305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chehade H, et al. Preterm birth: Long term cardiovascular and renal consequences. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2018;14(4):219–226. doi: 10.2174/1573396314666180813121652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamm L, et al. Early brain abnormalities in infants born very preterm predict under-reactive temperament. Early Hum. Dev. 2020;144:104985. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.104985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu L, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: An updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet. 2016;388(10063):3027–3035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31593-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walani SR. Global burden of preterm birth. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020;150(1):31–33. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bronstein JM, Wingate MS, Brisendine AE. Why is the U.S. preterm birth rate so much higher than the rates in Canada, Great Britain, and Western Europe? Int. J. Health Serv. 2018;48(4):622–640. doi: 10.1177/0020731418786360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin, J.A., et al., Births: Final data for 2019. National Center for Health Statistics, 2021. [PubMed]

- 18.Wagura P, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with preterm birth at Kenyatta national hospital. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1740-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrou S. Economic consequences of preterm birth and low birthweight. BJOG. 2003;110(20):17–23. doi: 10.1016/S1470-0328(03)00013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Underwood MA, Danielsen B, Gilbert WM. Cost, causes and rates of rehospitalization of preterm infants. J. Perinatol. 2007;27(10):614–619. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodek JM, von der Schulenburg JM, Mittendorf T. Measuring economic consequences of preterm birth—Methodological recommendations for the evaluation of personal burden on children and their caregivers. Health Econ. Rev. 2011;1(1):6. doi: 10.1186/2191-1991-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakshmanan A, et al. The impact of preterm birth <37 weeks on parents and families: a cross-sectional study in the 2 years after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0602-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldenberg RL, Goepfert AR, Ramsey PS. Biochemical markers for the prediction of preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;192(5 Suppl):S36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang HH, et al. Preventing preterm births: analysis of trends and potential reductions with interventions in 39 countries with very high human development index. Lancet. 2013;381(9862):223–234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61856-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lackritz EM, et al. A solution pathway for preterm birth: Accelerating a priority research agenda. Lancet Glob. Health. 2013;1(6):e328–e330. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70120-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newnham JP, et al. Reducing preterm birth by a statewide multifaceted program: An implementation study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;216(5):434–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.11.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romero R, et al. The use of high-dimensional biology (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) to understand the preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG. 2006;113(Suppl 3):118–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheikh IA, et al. Spontaneous preterm birth and single nucleotide gene polymorphisms: a recent update. BMC Genomics. 2016;17(Suppl 9):759. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3089-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delbaere I, et al. Pregnancy outcome in primiparae of advanced maternal age. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2007;135(1):41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torloni MR, et al. Maternal BMI and preterm birth: A systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2009;22(11):957–970. doi: 10.3109/14767050903042561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slack E, et al. Maternal obesity classes, preterm and post-term birth: A retrospective analysis of 479,864 births in England. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):434. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2585-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiono PH, Klebanoff MA, Rhoads GG. Smoking and drinking during pregnancy their effects on preterm birth. JAMA. 1986;255:82–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.1986.03370010088030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soneji S, Beltran-Sanchez H. Association of maternal cigarette smoking and smoking cessation with preterm birth. JAMA Netw. Open. 2019;2(4):e192514. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez SE, et al. Risk of spontaneous preterm birth in relation to maternal exposure to intimate partner violence during pregnancy in Peru. Matern. Child Health J. 2013;17(3):485–492. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1012-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silverman JG, et al. Intimate partner violence victimization prior to and during pregnancy among women residing in 26 US states: Associations with maternal and neonatal health. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;195(1):140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sigalla GN, et al. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and its association with preterm birth and low birth weight in Tanzania: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0172540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald SW, et al. Cumulative psychosocial stress, coping resources, and preterm birth. Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 2014;17(6):559–568. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanpradit K, Kaewkiattikun K. The effect of perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth. Int. J. Womens Health. 2020;12:287–293. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S239138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazaki-Tovi S, et al. Recurrent preterm birth. Semin. Perinatol. 2007;31(3):142–158. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laughon SK, et al. The NICHD Consecutive Pregnancies Study: Recurrent preterm delivery by subtype. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;210(2):131 e1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J, et al. Recurrence of preterm birth and early term birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016;128(2):364–372. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berger H, et al. Impact of diabetes, obesity and hypertension on preterm birth: Population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3):e0228743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Weger FJ, et al. Advanced maternal age, short interpregnancy interval, and perinatal outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204(5):421 e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schummers L, et al. Association of short interpregnancy interval with pregnancy outcomes according to maternal age. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018;178(12):1661–1670. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gibbs RS, et al. A review of premature birth and subclinical infection. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992;166(5):1515–1528. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91628-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romero R, et al. Infection and prematurity and the role of preventive strategies. Semin. Neonatol. 2002;7(4):259–274. doi: 10.1053/siny.2002.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Romero R, et al. Bacterial vaginosis, the inflammatory response and the risk of preterm birth: A role for genetic epidemiology in the prevention of preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;190(6):1509–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agrawal V, Hirsch E. Intrauterine infection and preterm labor. Semin. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2012;17(1):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verma I, Avasthi K, Berry V. Urogenital infections as a risk factor for preterm labor: A hospital-based case-control study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India. 2014;64(4):274–278. doi: 10.1007/s13224-014-0523-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romero R, et al. The role of inflammation and infection in preterm birth. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2007;25(1):21–39. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-956773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.York TP, et al. Racial differences in genetic and environmental risk to preterm birth. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8):e12391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dolan SM, et al. Synopsis of preterm birth genetic association studies: the preterm birth genetics knowledge base (PTBGene) Public Health Genomics. 2010;13(7–8):514–523. doi: 10.1159/000294202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Esplin MS, et al. Cluster analysis of spontaneous preterm birth phenotypes identifies potential associations among preterm birth mechanisms. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;213(3):429 e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strauss JF, 3rd, et al. Spontaneous preterm birth: Advances toward the discovery of genetic predisposition. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018;218(3):294–314 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin YT, et al. Associations between ozone and preterm birth in women who develop gestational diabetes. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015;181(4):280–287. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li X, et al. Association between ambient fine particulate matter and preterm birth or term low birth weight: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2017;227:596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Padula AM, et al. Environmental pollution and social factors as contributors to preterm birth in Fresno County. Environ. Health. 2018;17(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s12940-018-0414-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang H, et al. Investigation of association between environmental and socioeconomic factors and preterm birth in California. Environ. Int. 2018;121(Pt 2):1066–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ju L, et al. Maternal air pollution exposure increases the risk of preterm birth: Evidence from the meta-analysis of cohort studies. Environ. Res. 2021;202:111654. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Culhane JF, Goldenberg RL. Racial disparities in preterm birth. Semin. Perinatol. 2011;35(4):234–239. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wallace ME, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in preterm perinatal outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;216(3):306 e1–306 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.11.1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Purisch SE, Gyamfi-Bannerman C. Epidemiology of preterm birth. Semin. Perinatol. 2017;41(7):387–391. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mercer BM, et al. The preterm prediction study: A clinical risk assessment system. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996;174:1885–1895. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beta J, et al. Prediction of spontaneous preterm delivery from maternal factors, obstetric history and placental perfusion and function at 11–13 weeks. Prenat. Diagn. 2011;31(1):75–83. doi: 10.1002/pd.2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fuchs F, et al. Predictive score for early preterm birth in decisions about emergency cervical cerclage in singleton pregnancies. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2012;91(6):744–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peaeeman AM, et al. Fetal fibronectin as a predictor of preterm birth with symptoms: A multicenter trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997;177:13–18. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chien PF, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of cervico-vaginal fetal fibronectin in predicting preterm delivery: an overview. BJOG. 1997;104:436–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leitich H, et al. Cervicovaginal foetal fibronectin as a marker for preterm delivery: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;180:1169–1176. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70612-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hezelgrave NL, Shennan AH. Quantitative fetal fibronectin to predict spontaneous preterm birth: A review. Womens Health (Lond.) 2016;12:121–128. doi: 10.2217/whe.15.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wenstrom KD, et al. Elevated second-trimester amniotic fluid interleukin-6 levels predict preterm delivery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998;178:546–550. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(98)70436-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yoon BH, et al. Clinical significance of intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;185(5):1130–1136. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gervasi MT, et al. Midtrimester amniotic fluid concentrations of interleukin-6 and interferon-gamma-inducible protein-10: Evidence for heterogeneity of intra-amniotic inflammation and associations with spontaneous early (<32 weeks) and late (>32 weeks) preterm delivery. J. Perinat. Med. 2012;40(4):329–343. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2012-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leanos-Miranda A, et al. Interleukin-6 in amniotic fluid: A reliable marker for adverse outcomes in women in preterm labor and intact membranes. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2021;48(4):313–320. doi: 10.1159/000514898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vuadens F, et al. Identification of biologic markers of the premature rupture of fetal membranes: Proteomic approach. Proteomics. 2003;3(8):1521–1525. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gravett MG, et al. Diagnosis of intraamniotic infection by proteomic profiling and identification of novel biomarkers. JAMA. 2004;292(4):462–469. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Buhimschi IA, Christner R, Buhimschi CS. Proteomic biomarker analysis of amniotic fluid for identification of intra-amniotic inflammation. BJOG. 2005;112(2):173–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Michaels JE, et al. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of the human amniotic fluid proteome: Gestational age-dependent changes. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6(4):1277–1285. doi: 10.1021/pr060543t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Queloz PA, et al. Proteomic analyses of amniotic fluid: Potential applications in health and diseases. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2007;850(1–2):336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bujold E, et al. Proteomic profiling of amniotic fluid in preterm labor using two-dimensional liquid separation and mass spectrometry. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2008;21(10):697–713. doi: 10.1080/14767050802053289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Buhimschi IA, et al. Multidimensional proteomics analysis of amniotic fluid to provide insight into the mechanisms of idiopathic preterm birth. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(4):e2049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Romero R, et al. Proteomic analysis of amniotic fluid to identify women with preterm labor and intra-amniotic inflammation/infection: The use of a novel computational method to analyze mass spectrometric profiling. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2008;21(6):367–388. doi: 10.1080/14767050802045848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fotopoulou C, et al. Proteomic analysis of midtrimester amniotic fluid to identify novel biomarkers for preterm delivery. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2012;25(12):2488–2493. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.712565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tambor V, et al. Proteomics and bioinformatics analysis reveal underlying pathways of infection associated histologic chorioamnionitis in pPROM. Placenta. 2013;34(2):155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bahado-Singh RO, et al. Artificial intelligence and amniotic fluid multiomics: Prediction of perinatal outcome in asymptomatic women with short cervix. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019;54(1):110–118. doi: 10.1002/uog.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hong S, et al. Identifying potential biomarkers related to pre-term delivery by proteomic analysis of amniotic fluid. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):19648. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76748-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jeon HS, et al. Proteomic biomarkers in mid-trimester amniotic fluid associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7):e0235838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bhatti G, et al. The amniotic fluid cell-free transcriptome in spontaneous preterm labor. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):13481. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92439-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cho CK, et al. Proteomics analysis of human amniotic fluid. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;6:1406–1415. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700090-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tsangaris GT, et al. Application of proteomics for the identification of biomarkers in amniotic fluid: Are we ready to provide a reliable prediction? EPMA J. 2011;2(2):149–155. doi: 10.1007/s13167-011-0083-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kamath-Rayne BD, et al. Amniotic fluid: The use of high-dimensional biology to understand fetal well-being. Reprod. Sci. 2014;21(1):6–19. doi: 10.1177/1933719113485292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee SM, et al. Mid-trimester amniotic fluid pro-inflammatory biomarkers predict the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery in twins: A retrospective cohort study. J. Perinatol. 2015;35(8):542–546. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hallingstrom M, et al. Mid-trimester amniotic fluid proteome's association with spontaneous preterm delivery and gestational duration. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0232553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hsu TY, et al. Identifying the potential protein biomarkers of preterm birth in amniotic fluid. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;59(3):366–371. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tarca AL, et al. Crowdsourcing assessment of maternal blood multi-omics for predicting gestational age and preterm birth. Cell Rep. Med. 2021;2(6):100323. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee SM, et al. Prediction of spontaneous preterm birth in women with cervical insufficiency: Comprehensive analysis of multiple proteins in amniotic fluid. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2016;42(7):776–783. doi: 10.1111/jog.12976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Goldenberg RL, et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: Toward a multiple-marker test for spontaneous preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;185:643–651. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.116752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Holst RM, et al. Prediction of spontaneous preterm delivery in women with preterm labor: Analysis of multiple proteins in amniotic and cervical fluids. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:268–277. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ae6a08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Huang L, et al. Serum multiple cytokines for the prediction of spontaneous preterm birth in asymptomatic women: A nested case-control study. Cytokine. 2019;117:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Iams JD, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;334(9):567–572. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hassan SS, et al. Patients with an ultrasonographic cervical length < or =15 mm have nearly a 50% risk of early spontaneous preterm delivery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000;182(6):1458–1467. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Romero R, et al. A blueprint for the prevention of preterm birth: Vaginal progesterone in women with a short cervix. J. Perinat. Med. 2013;41(1):27–44. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2012-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hiersch L, et al. Role of cervical length measurement for preterm delivery prediction in women with threatened preterm labor and cervical dilatation. J. Ultrasound Med. 2016;35(12):2631–2640. doi: 10.7863/ultra.15.12007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Son M, Miller ES. Predicting preterm birth: Cervical length and fetal fibronectin. Semin. Perinatol. 2017;41(8):445–451. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Berghella V, et al. Cerclage for sonographic short cervix in singleton gestations without prior spontaneous preterm birth: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials using individual patient-level data. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;50(5):569–577. doi: 10.1002/uog.17457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rosenbloom JI, et al. Predictive value of midtrimester universal cervical length screening based on parity. J. Ultrasound Med. 2020;39(1):147–154. doi: 10.1002/jum.15091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Maia MC, et al. Is cervical length evaluated by transvaginal ultrasonography helpful in detecting true preterm labor? J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2020;33(17):2902–2908. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1564026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fonseca EB, et al. Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357(5):462–469. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hassan SS, et al. Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38(1):18–31. doi: 10.1002/uog.9017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Romero R, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth and neonatal morbidity and mortality in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix: An updated meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;49(3):303–314. doi: 10.1002/uog.17397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Romero R, et al. Vaginal progesterone for preventing preterm birth and adverse perinatal outcomes in singleton gestations with a short cervix: A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018;218(2):161–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone is as effective as cervical cerclage to prevent preterm birth in women with a singleton gestation, previous spontaneous preterm birth, and a short cervix: Updated indirect comparison meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018;219(1):10–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gudicha DW, et al. Personalized assessment of cervical length improves prediction of spontaneous preterm birth: A standard and a percentile calculator. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021;224(3):288 e1–288 e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Oh KJ, et al. Evidence that antibiotic administration is effective in the treatment of a subset of patients with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation presenting with cervical insufficiency. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019;221(2):140 e1–140 e18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yeo, L., et al., Resolution of acute cervical insufficiency after antibiotics in a case with amniotic fluid sludge. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 1–11 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 115.Romero R, et al. Sterile intra-amniotic inflammation in asymptomatic patients with a sonographic short cervix: Prevalence and clinical significance. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2015;28(11):1343–1359. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.954243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tarca, A.L., et al., The cytokine network in women with an asymptomatic short cervix and the risk of preterm delivery. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 78(3) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 117.Gold L, et al. Aptamer-based multiplexed proteomic technology for biomarker discovery. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):e15004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Davies DR, et al. Unique motifs and hydrophobic interactions shape the binding of modified DNA ligands to protein targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109(49):19971–19976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213933109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Romero R, et al. The maternal plasma proteome changes as a function of gestational age in normal pregnancy: A longitudinal study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;217(1):671–6721. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Phipson B, et al. Robust hyperparameter estimation protects against hypervariable genes and improves power to detect differential expression. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2016;10(2):946–963. doi: 10.1214/16-AOAS920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tarca AL, et al. Strengths and limitations of microarray-based phenotype prediction: Lessons learned from the IMPROVER diagnostic signature challenge. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(22):2892–2899. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Belcastro V, et al. The sbv IMPROVER systems toxicology computational challenge: Identification of human and species-independent blood response markers as predictors of smoking exposure and cessation status. Comput. Toxicol. 2018;5:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.comtox.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Dayarian A, et al. Predicting protein phosphorylation from gene expression: Top methods from the IMPROVER species translation challenge. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(4):462–470. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ritchie ME, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yu G, et al. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16(5):284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gu Z, Eils R, Schlesner M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(18):2847–2849. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Vaisbuch E, et al. Patients with an asymptomatic short cervix (<or=15 mm) have a high rate of subclinical intraamniotic inflammation: Implications for patient counseling. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;202(5):4331–4338. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hassan S, et al. A sonographic short cervix as the only clinical manifestation of intra-amniotic infection. J. Perinat. Med. 2006;34(1):13–19. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2006.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kramer MS, et al. Mid-trimester maternal plasma cytokines and CRP as predictors of spontaneous preterm birth. Cytokine. 2010;49(1):10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sorokin Y, et al. Maternal serum interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 concentrations as risk factors for preterm birth <32 weeks and adverse neonatal outcomes. Am. J. Perinatol. 2010;27(8):631–640. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Shahshahan Z, Hashemi L. Maternal serum cytokines in the prediction of preterm labor and response to tocolytic therapy in preterm labor women. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2014;3:126. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.133243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Figueroa R, et al. Evaluation of amniotic fluid cytokines in preterm labor and intact membranes. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2005;18(4):241–247. doi: 10.1080/13506120500223241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Thomakos N, et al. Amniotic fluid interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha at mid-trimester genetic amniocentesis: Relationship to intra-amniotic microbial invasion and preterm delivery. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2010;148(2):147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.La Sala GB, et al. Protein microarrays on midtrimester amniotic fluids: A novel approach for the diagnosis of early intrauterine inflammation related to preterm delivery. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2012;25:1029–1040. doi: 10.1177/039463201202500420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kim A, et al. Identification of biomarkers for preterm delivery in mid-trimester amniotic fluid. Placenta. 2013;34(10):873–878. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.06.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Theis KR, et al. Microbial burden and inflammasome activation in amniotic fluid of patients with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. J. Perinat. Med. 2020;48(2):115–131. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2019-0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Coleman MA, et al. Predicting preterm delivery: Comparison of cervicovaginal interleukin (IL)-1beta, IL-6 and IL-8 with fetal fibronectin and cervical dilatation. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2001;95(2):154–158. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(00)00450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Torbe A, Czajka R. Proinflammatory cytokines and other indications of inflammation in cervico-vaginal secretions and preterm delivery. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2004;87(2):125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Kiefer DG, et al. Amniotic fluid inflammatory score is associated with pregnancy outcome in patients with mid trimester short cervix. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;206(1):68 e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Weiss A, Goldman S, Shalev E. The matrix metalloproteinases (MMPS) in the decidua and fetal membranes. Front Biosci. 2007;12:649–659. doi: 10.2741/2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Park CW, et al. The antenatal identification of funisitis with a rapid MMP-8 bedside test. J. Perinat. Med. 2008;36(6):497–502. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Oh KJ, et al. Detection of ureaplasmas by the polymerase chain reaction in the amniotic fluid of patients with cervical insufficiency. J. Perinat. Med. 2010;38(3):261–268. doi: 10.1515/jpm.2010.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Park CW, et al. The frequency and clinical significance of intra-amniotic inflammation defined as an elevated amniotic fluid matrix metalloproteinase-8 in patients with preterm labor and low amniotic fluid white blood cell counts. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2013;56(3):167–175. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2013.56.3.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kim SM, et al. The relationship between the intensity of intra-amniotic inflammation and the presence and severity of acute histologic chorioamnionitis in preterm gestation. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2015;28(13):1500–1509. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.961009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Gravett MG, et al. An experimental model for intraamniotic infection and preterm labor in rhesus monkeys. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994;171(6):1660–1667. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(94)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Gravett MG, et al. Immunomodulators plus antibiotics delay preterm delivery after experimental intraamniotic infection in a nonhuman primate model. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007;197(5):518 e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Novy MJ, et al. Ureaplasma parvum or Mycoplasma hominis as sole pathogens cause chorioamnionitis, preterm delivery, and fetal pneumonia in rhesus macaques. Reprod Sci. 2009;16(1):56–70. doi: 10.1177/1933719108325508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Grigsby PL, et al. Maternal azithromycin therapy for Ureaplasma intraamniotic infection delays preterm delivery and reduces fetal lung injury in a primate model. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;207(6):475 e1–475 e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Gomez-Lopez N, et al. Intra-amniotic administration of HMGB1 induces spontaneous preterm labor and birth. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2016;75(1):3–7. doi: 10.1111/aji.12443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Gomez-Lopez N, et al. Intra-amniotic administration of lipopolysaccharide induces spontaneous preterm labor and birth in the absence of a body temperature change. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2018;31(4):439–446. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1287894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Gomez-Lopez N, et al. Inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome can prevent sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, preterm labor/birth, and adverse neonatal outcomes. Biol. Reprod. 2019;100(5):1306–1318. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Faro J, et al. Intra-amniotic inflammation induces preterm birth by activating the NLRP3 inflammasomedagger. Biol. Reprod. 2019;100(5):1290–1305. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Coleman M, et al. A broad spectrum chemokine inhibitor prevents preterm labor but not microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity or neonatal morbidity in a non-human primate model. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:770. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Motomura, K., et al., Intra-amniotic infection with Ureaplasma parvum causes preterm birth and neonatal mortality that are prevented by treatment with clarithromycin. mBio11(3) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 155.Motomura, K., et al., The alarmin interleukin-1alpha causes preterm birth through the NLRP3 inflammasome. Mol. Hum. Reprod. (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 156.Galaz J, et al. Betamethasone as a potential treatment for preterm birth associated with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation: A murine study. J. Perinat. Med. 2021;49(7):897–906. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2021-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Brat DJ, Bellail AC, Van Meir EG. The role of Interleukin-8 and its receptors in gliomagenesis and tumoral angiogenesis. Neuro-oncol. 2005;7:122–133. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704001061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Russo RC, et al. The CXCL8/IL-8 chemokine family and its receptors in inflammatory diseases. Expert. Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2014;10(5):593–619. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2014.894886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Witt A, et al. IL-8 concentrations in maternal serum, amniotic fluid and cord blood in relation to different pathogens within the amniotic cavity. J. Perinat. Med. 2005;33(1):22–26. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2005.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Romero R, et al. The preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG. 2006;113(Suppl 3):17–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Romero R, et al. Evidence of perturbations of the cytokine network in preterm labor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;213(6):8361–83618. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Saito S, et al. Detection and localization of interleukin-8 mRNA and protein in human placenta and decidual tissues. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1994;27:161–172. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Gomez-Lopez N, et al. The role of chemokines in term and premature rupture of the fetal membranes: A review. Biol. Reprod. 2010;82(5):809–814. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.080432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Hamilton SA, Tower CL, Jones RL. Identification of chemokines associated with the recruitment of decidual leukocytes in human labour: potential novel targets for preterm labour. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e56946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Gomez-Lopez N, et al. Immune cells in term and preterm labor. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2014;11(6):571–581. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Kedzierska-Markowicz A, et al. Evaluation of the correlation between IL-1beta, IL-8, IFN-gamma cytokine concentration in cervico-vaginal fluid and the risk of preterm delivery. Ginekol. Pol. 2015;86(11):821–826. doi: 10.17772/gp/59269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Gomez-Lopez N, et al. RNA sequencing reveals diverse functions of amniotic fluid neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in intra-amniotic infection. J. Innate Immun. 2021;13(2):63–82. doi: 10.1159/000509718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Gomez-Lopez, N., et al., Amniotic fluid neutrophils can phagocytize bacteria: A mechanism for microbial killing in the amniotic cavity. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 78(4) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 169.Heller KA, Greig PC, Heine RP. Amniotic-fluid lactoferrin: A marker for subclinical intraamniotic infection prior to 32 weeks gestation. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995;3(5):179–183. doi: 10.1155/S1064744995000573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Otsuki K, et al. Amniotic fluid lactoferrin in intrauterine infection. Placenta. 1999;20(2–3):175–179. doi: 10.1053/plac.1998.0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Pacora P, et al. Lactoferrin in intrauterine infection, human parturition, and rupture of fetal membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000;183(4):904–910. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.108882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Maymon E, et al. Value of amniotic fluid neutrophil collagenase concentrations in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;185(5):1143–1148. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.118166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Espinoza J, et al. Antimicrobial peptides in amniotic fluid: Defensins, calprotectin and bacterial/permeability-increasing protein in patients with microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity, intra-amniotic inflammation, preterm labor and premature rupture of membranes. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2003;13(1):2–21. doi: 10.1080/jmf.13.1.2.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Soto E, et al. Human beta-defensin-2: A natural antimicrobial peptide present in amniotic fluid participates in the host response to microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 2007;20(1):15–22. doi: 10.1080/14767050601036212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Martinez-Varea A, et al. Clinical chorioamnionitis at term VII: The amniotic fluid cellular immune response. J. Perinat. Med. 2017;45(5):523–538. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2016-0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]