Abstract

Objective

Paraguay’s health care system is characterized by segmented provision and low public spending, with limited coverage and asymmetries in terms of access and quality of care. The present study provides national estimates of income-related inequality in health care utilization and trends in the country over the past two decades.

Methods

Using data from the Paraguayan Permanent Household Survey, we estimated socioeconomic inequality in health care use during the period 1999–2018. We used poverty-to-income ratio as the socioeconomic stratifier and defined health care use as having reported a health problem and subsequent health care use in the last 90 days before interview. Inequality was summarized by rank- and level-based versions of the Concentration Index for binary outcomes.

Results

Inequalities affecting those with lower incomes were present in all years assessed, although the magnitude of these inequalities declined over time. Inequality as expressed by the rank-based index decreased from 0.209 (95%CI 0.164; 0.253) in 1999 to 0.032 (95%CI -0.010; 0.075) in 2018. The level-based index decreased from 0.076 (95%CI -0.029; 0.182) in 1999 to 0.024 (0.002; 0.045) in 2018. Trends in both indices were generally stable from 1999 to 2009, with a noticeable decrease in 2010. The sharpest decreases relative to the 1999 baseline were observed in the period 2010–2018, reflecting changes in health care use and income distribution. Stratification by area, sex and older people suggest similar trends within subgroups.

Conclusions

Decreases in inequality coincide temporally with increments in public health expenditure, removal of user fees in public health care facilities and the expansion of conditional cash-transfer programmes. Future research should disentangle the role of each of these policies in explaining the trends described.

Keywords: Health care access, socioeconomic inequalities, health equity, concentration index, Paraguay

Introduction

Health care access is crucial to improving population health and reduce health inequalities. Paraguay’s health care system is comprised of providers from the public and private sectors. Coverage is provided in three ways. First, the Social Security Institute provides coverage to formal employees and their dependants, and is financed through contributions from the employee, the employer and the state. Second, private insurance companies provide coverage primarily to middle- and upper-socioeconomic classes through prepaid health plan fees and out-of-pocket copayments. Third, those who are not covered through any of the other two schemes, fall under the responsibility of the Ministry of Public Health and Social Welfare (MSPyBS), financed through the Public Treasury. 1

The system is characterized by low integration among providers, disconnected financing mechanisms and wide variation in terms of coverage and quality of care. 1 Also, it is sustained by private spending, which accounts for the largest share of total health care spending: throughout 2005–2014 the proportion of private spending ranged from 61.2% in 2005 to 54.1% in 2014. 2 Private health expenditure through direct payments can have major negative consequences on health care access. 3 The barriers induced by private expenditures are particularly relevant, as out-of-pocket expenditure accounted for almost 90% of private health expenditure and 45% of total health expenditure in 2018. 4 Out-of-pocket expenditure at the point of service, the most inefficient and regressive form of financing, yields an unstable flow of financial resources and constitutes an access barrier that impedes or delays care, and makes it more expensive for both patients and the system. 3 Furthermore, out-of-pocket expenditure has a relatively greater impact on the poor, as even the smallest payment can represent a substantial portion of their budget.5,6

Regressive health care financing directly impacts access and coverage.3,6 A large fraction of the Paraguayan population lacks formal health insurance. In 2014, 20.3% had Social Security Institute insurance, 7.3% had private insurance and 1.7% had another type of insurance, while around 70% remains dependent on the health services provided by the MSPyBS, 2 with limited coverage and service supply as well as questionable quality of services. 7 Stratified by income, in 2014, the proportion of uninsured was 94.8% for the poorest quintile, 84.7% in the second poorest, 73.5% in the third, 59.9% in the fourth, and 40.6% in the least poor. 2 This shows insurance coverage in Paraguay has a socioeconomic gradient where the lack of insurance is most prevalent among the poorest, thus setting structural conditions to exclude those in most vulnerable socioeconomic circumstances. Despite this context, there have been no rigorous assessments of the magnitude and change of socioeconomic inequalities in health care utilization in the Paraguayan context. Monitoring inequalities in health care is important to assess progress towards more equitable health care systems, but the extent of progress (or lack thereof) in Paraguay is unclear. The present study is aimed at providing national estimates of income-related inequality in health care utilization and trends over the past two decades.

Methods

Data source

We obtained data from the Paraguayan Permanent Household Survey (EPH), for the period 1999–2018. EPH are cross-sectional surveys conducted annually, covering employment, income, household demographics and other social factors. Conducted by the National Institute of Statistics, it is designed to be representative of the non-institutionalized population. EPH uses a complex, two-stage probability cluster sample design, with census segments as first-stage primary sampling units and households randomly selected within each primary sampling unit in the second stage. Design and weighting methodology have been consistent over time. Data collection was done through in-person interviews. Details on survey methodology can be found elsewhere. 8 We excluded EPH for the years 2002 and 2011 because health care information was not collected in those years. Our analysis focuses on participants aged 18 or over. All microdata are publicly available at National Institute of Statistics website. 9

Study variables

Health care utilization

Health care use was defined as having reported a health problem and subsequent health care use in the last 90 days before interview. A first question asked participants on the occurrence of any health problem in the last 90 days. A subsequent question asked whether they used any health care due to the problem reported (i.e. consultation, hospitalization and emergency care). Thus, our analysis restricted EPH samples to those adults who reported a health problem in the last 90 days. On average, this restricted sample represented 32% of the full EPH adult sample (range between 21% and 43%). Details of this ‘in-scope’ population are presented in the Online Supplement 1 (Table S1).

Income

EPH measures per-capita income as the ratio between the household income from all sources and the number of family members in the household. We computed the poverty-to-income ratio (PIR) by dividing the per-capita income by year-specific per-capita poverty line. All inequality indices were computed using PIR as a continuous measure. For general sample description and easier contextualization of results, we grouped PIR into five categories: (PIR<1, 1≤PIR<2, 2≤PIR<3, 3≤PIR<5 and PIR≥5). Missing data on income was <1.5% across EPH cycles.

Analysis

Overall income-related inequality in health care use was summarized by the Concentration Index (CIx). 10 As originally proposed by Wagstaff et al., 10 the CIx is a rank-based relative bivariate linear index that quantifies the relationship between socioeconomic ranking (e.g. rank in the cumulative distribution of PIR) and a health outcome (e.g. health care use). The CIx can be visually portrayed by a relative concentration curve – a plot of the cumulative share of health care use accounted for by cumulative proportions of individuals ranked by PIR. Perfect equality in health care use would be represented by a diagonal line in the plot, where, for example, the poorest 50% of the population accounts for 50% of health care use. A curve lying above the diagonal would indicate utilization is disproportionately concentrated among those with lower income, and if below the diagonal, it is concentrated among higher income groups (for hypothetical relative concentration curves, see Figure S1 in the Online Supplement 1). The CIx is defined as twice the area between the curve and the line of equality. For the continuous, unbounded health care variables, the relative CIx ranges from −1 to 1, depending on whether the curve is above or below the diagonal, respectively. A value of zero indicates equal utilization across income levels. The absolute version of this index is computed by multiplying the relative CIx by the utilization rate in the population and can be written as

where is the weight specific to individual i (a function of i’s fractional rank in the cumulative distribution of the sample ranked by PIR) and is the utilization indicator for individual i. Thus, the absolute CIx can be interpreted as a weighted mean of health care use, where the weights depend on the fractional PIR rank. Corrected versions of the index have been proposed to deal with binary variables such as health care use as defined in this study.11,12 Recently, a case has been made to base the CIx on the levels of the socioeconomic stratifier rather than on its rank (e.g. weights as a function of PIR levels rather than ranks, ). 13 Thus, to avoid our results and conclusions being sensitive to the weighting scheme chosen, we estimate and report rank-dependent and level-dependent versions of the Erreygers’ modified CIx for binary outcomes, which also range between −1 and 1.12,14 We estimated, separately, the rank-based and level-based index via OLS regression of rank and level-based transformations of health care use on either the PIR rank or level (i.e. the ‘convenient covariance approach’), 15 which allowed us to account for the complex survey design in the estimation of standard errors and 95% confidence intervals. A replication file including the data and code is available at the Open Science Foundation platform. 16

Results

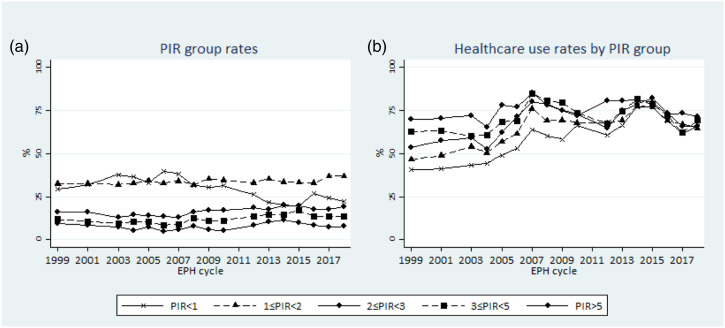

Sample sizes ranged from 2522 (EPH 2007) to 9915 (EPH 2017) participants. On average across the period, people who reported a health problem accounted for 31.4% of the adult population, ranging from 19.2% to 40.0% (see Online Supplement 1, Table S1). Descriptions of each cross-sectional sample regarding health care utilization and income is provided in Table 1. There was a gradual increase in health care utilization rates from 50.3% in 1999 to 66.5% in 2018, with some fluctuations over the period. Regarding the distribution of income, there was not much change in the proportion of groups with incomes above the poverty line. Conversely, the proportion of people below poverty (i.e. with PIR<1) decreased from 29.4% in 1999 to 22.2% in 2018, although this decrease was not consistent over the period. During the first years, poverty rates tended to increase, reaching a pick of 39.9% in 2006. Figure 1, Panel (a), plots the trends in the distribution of income groups over time and shows that the decreasing trend in poverty rates started around the year 2008.

Table 1.

Sample description a Paraguayan Permanent Household Survey 1999 to 2018.

| Cycle (n) | Healthcare use | PIR<1 | 1≥ PIR <2 | 2≥PIR <3 | 3≥PIR <5 | PIR≥5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (CI95%) | n | % (CI95%) | n | % (CI95%) | n | % (CI95%) | n | % (CI95%) | n | % (CI95%) | |

| 1999 (4492) | 2243 | 50.3 (48.1, 52.6) | 1534 | 29.4 (27.0, 31.9) | 1332 | 32.7 (30.0, 35.5) | 667 | 16.1 (14.3, 18.2) | 518 | 12.1 (10.6, 13.7) | 441 | 9.7 (8.3, 11.5) |

| 2000–1 (7665) | 3866 | 51.2 (48.8, 53.6) | 2440 | 32.1 (29.4, 35.0) | 2367 | 32.7 (30.2, 35.4) | 1215 | 16.1 (14.3, 18.2) | 922 | 10.7 (9.3, 12.3) | 721 | 8.3 (6.9, 10.0) |

| 2003 (7142) | 3735 | 52.7 (50.9, 54.5) | 2767 | 37.9 (35.5, 40.3) | 2262 | 32.1 (30.1, 34.3) | 905 | 12.8 (11.6, 14.2) | 708 | 9.7 (8.6, 11.0) | 500 | 7.4 (6.2, 8.7) |

| 2004 (6344) | 3236 | 50.6 (48.6, 52.6) | 2338 | 36.7 (34.3, 39.1) | 2053 | 32.8 (30.8, 34.9) | 898 | 14.5 (13.0, 16.1) | 687 | 10.4 (9.1, 11.9) | 368 | 5.6 (4.6, 6.7) |

| 2005 (3795) | 2111 | 57.9 (55.3, 60.5) | 1276 | 33.3 (30.1, 36.7) | 1256 | 34.4 (31.6, 37.4) | 543 | 14.3 (12.4, 16.3) | 419 | 10.4 (8.7, 12.3) | 301 | 7.6 (6.1, 9.5) |

| 2006 (2847) | 1748 | 60.9 (57.6, 64.1) | 1135 | 39.9 (36.3, 43.6) | 922 | 32.8 (29.9, 35.9) | 411 | 13.7 (11.7, 15.9) | 236 | 8.7 (6.9, 10.8) | 143 | 4.9 (3.6, 6.7) |

| 2007 (2522) | 1783 | 73.4 (70.7, 75.8) | 995 | 38.1 (34.9, 41.4) | 855 | 34.3 (31.4, 37.2) | 301 | 12.9 (11.1, 15.0) | 217 | 8.8 (7.3, 10.5) | 154 | 5.9 (4.8, 7.3) |

| 2008 (3211) | 2234 | 70.2 (67.7, 72.6) | 1068 | 31.5 (28.6, 34.6) | 1037 | 31.8 (29.1, 34.6) | 472 | 16.4 (14.1, 18.9) | 390 | 12.7 (10.8, 14.8) | 244 | 7.7 (6.3, 9.3) |

| 2009 (3470) | 2412 | 68.6 (66.1, 71.0) | 1182 | 30.4 (27.6, 33.5) | 1143 | 35.5 (32.5, 38.7) | 495 | 17.1 (14.6, 20.0) | 414 | 10.9 (9.3, 12.8) | 236 | 6.0 (4.8, 7.6) |

| 2010 (4327) | 2990 | 69.2 (67.2, 71.1) | 1404 | 31.4 (28.7, 34.3) | 1399 | 34.7 (32.3, 37.2) | 737 | 17.1 (15.1, 19.3) | 517 | 11.3 (9.5, 13.2) | 270 | 5.5 (4.5, 6.7) |

| 2012 (4991) | 3281 | 66.6 (64.5, 68.6) | 1294 | 26.3 (23.8, 28.9) | 1638 | 33.1 (31.0, 35.2) | 903 | 18.5 (16.7, 20.4) | 687 | 13.7 (12.1, 15.5) | 469 | 8.5 (7.3, 9.8) |

| 2013 (4438) | 3139 | 71.7 (68.9, 74.3) | 1002 | 21.6 (19.2, 24.3) | 1557 | 35.3 (32.9, 37.9) | 772 | 17.7 (15.8, 19.8) | 655 | 14.7 (13.0, 16.6) | 452 | 10.6 (8.7, 12.9) |

| 2014 (3122) | 2401 | 78.8 (76.6, 80.9) | 653 | 19.8 (17.3, 22.6) | 1067 | 33.7 (31.1, 36.5) | 628 | 20.1 (18.1, 22.4) | 443 | 14.7 (12.9, 16.8) | 331 | 11.6 (9.7, 13.7) |

| 2015 (5993) | 4766 | 78.6 (76.5, 80.5) | 1256 | 19.8 (17.7, 22.0) | 1901 | 33.3 (30.8, 35.9) | 1161 | 19.7 (17.9, 21.7) | 990 | 17.0 (15.1, 19.1) | 685 | 10.2 (8.8, 11.8) |

| 2016 (9078) | 6467 | 70.6 (68.9, 72.3) | 2702 | 26.9 (25.0, 28.8) | 3072 | 33.0 (31.2, 34.8) | 1543 | 17.8 (16.4, 19.3) | 1054 | 13.7 (12.4, 15.1) | 707 | 8.6 (7.4, 10.0) |

| 2017 (9915) | 6641 | 65.5 (63.9, 67.1) | 2596 | 24.3 (22.7, 26.0) | 3699 | 37.0 (35.1, 38.9) | 1658 | 17.8 (16.5, 19.2) | 1270 | 13.6 (12.3, 15.0) | 692 | 7.3 (6.3, 8.3) |

| 2018 (4752) | 3236 | 66.5 (64.5, 68.4) | 1156 | 22.2 (20.1, 24.6) | 1734 | 37.0 (34.5, 39.5) | 864 | 19.0 (17.0, 21.1) | 593 | 13.8 (12.0, 15.8) | 405 | 8.0 (6.8, 9.3) |

CI: confidence interval; PIR: poverty-to-income ratio

aSample restricted to those who reported a health problem in last 90 days.

Figure 1.

Poverty-to-income ratio and health care utilization rates, Paraguayan Permanent Household Survey 1999 to 2018.

Figure 1, Panel (b), summarizes trends of health service utilization by income groups (for detailed estimates, see Online Supplement 1, Table S2). Utilization rates increased for all income groups, although not monotonically for any. The greatest increase was among those with the lowest income: the increase between 1999 and 2018 was around 25 percentage points (relative increase 61%). For the second-poorest income group, the increase was 20 percentage points (relative increase of 39%). In terms of the gap between the highest versus lowest income groups, the widest gap in absolute and relative terms was observed in the years 2000–01 (29.4% points, 71.9% of the rate for those with PIR<1), while the narrowest gap was in 2015 (2.8% points, 3.7% of the rate for those with PIR<1). In comparison to 2015, utilization decreased for all income groups in the subsequent years.

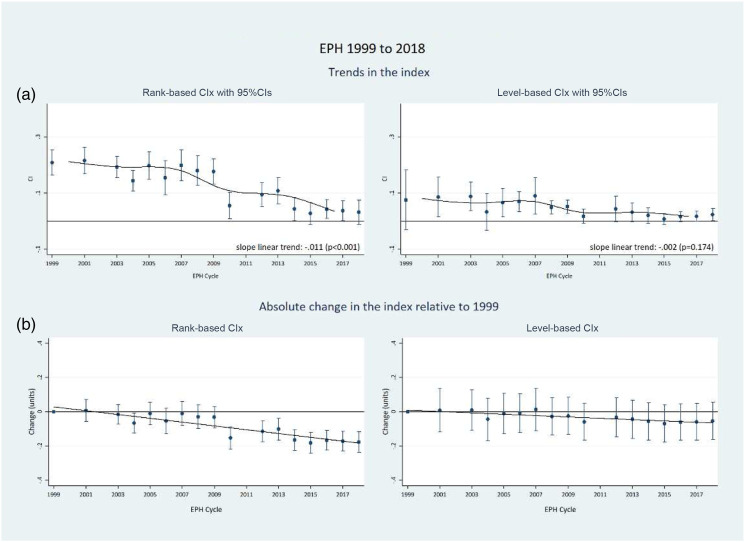

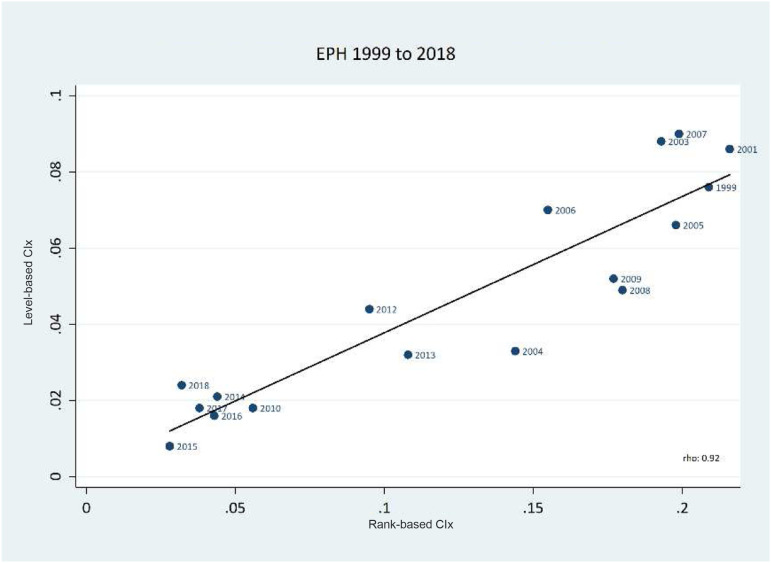

Table 2 shows income-related inequality in health care utilization for each year, as expressed by the rank- and level-dependent CIxs. The positive coefficients show that, in all years, health care utilization was more concentrated among those with higher income. In general terms, the magnitude of the inequality in each year was moderate: the mean rank-based CIx was 0.124 (range: 0.028–0.216), while the mean level-based CIx was 0.047 (range 0.008–0.090). The magnitude of inequality was not uniform across the period of observation. The rank-based CIx decreased from 0.209 (95% CI 0.164, 0.253) in 1999 to 0.032 (95% CI -0.010, 0.075) in 2018 (85% reduction). The level-based CIx decreased from 0.076 (95% CI −0.029, 0.182) in 1999 to 0.024 (95% CI 0.02, 0.045) in 2018 (68% reduction). Both indices showed notable decreases in 2010–2016 relative to 1999. Figure 2, Panel (a), plots these two inequality indices over time. Rank-based and level-based indices show similar trend patterns in the sense that higher inequality was observed in the first decade of our assessment. Between 1999 and 2009 estimates were relatively unchanged, with some fluctuation in point estimates mainly due to sampling variation. In 2010, we found a decrease in comparison to the previous year: from 0.177 to 0.056 for the rank-based index and from 0.052 to 0.018 for the level-based CIx. Between 2010 and 2018 the estimates did not change appreciably but were systematically below the levels observed during the 1999–2009 period. The decrease over time, however, is notably less pronounced for the level-based index for the rank-based index (Figure 2, Panel (b): the slope for linear trend is −0.011/year (95% CI -0.013, −0.009, p < .001) for the rank-based CIx versus −0.002/year (95% CI -0.006, 0.00, p = .174) for the level-based CIx. Figure 3 shows the correlation between the two measures suggesting a general consistency in the ranking of the indices.

Table 2.

Income-related inequalities in healthcare utilization: rank- and level-dependent concentration indices. Paraguayan Permanent Household Survey 1999 to 2018.

| Paraguayan Permanent Household Survey (n) | Rank-based concentration index | Level-based concentration index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95%CI) | Change a (95%CI) | Estimate (95%CI) | Change a (95%CI) | |

| 1999 | 0.209 (0.164, 0.253) | — | 0.076 (−0.029, 0.182) | — |

| 2000–01 | 0.216 (0.169, 0.263) | 0.007 (−0.057, 0.071) | 0.086 (0.015, 0.157) | 0.009 (−0.117, 0.136) |

| 2003 | 0.193 (0.156, 0.229) | −0.016 (−0.073, 0.041) | 0.088 (0.037, 0.139) | 0.011 (−0.106, 0.128) |

| 2004 | 0.144 (0.106, 0.181) | −0.065 (−0.124, −0.007) | 0.033 (−0.032, 0.097) | −0.044 (−0.167, 0.079) |

| 2005 | 0.198 (0.150, 0.247) | −0.010 (−0.077, 0.056) | 0.066 (0.015, 0.117) | −0.010 (−0.127, 0.107) |

| 2006 | 0.155 (0.093, 0.216) | −0.054 (−0.129, 0.021) | 0.070 (0.034, 0.105) | −0.007 (−0.118, 0.104) |

| 2007 | 0.199 (0.145, 0.253) | −0.010 (−0.080, 0.061) | 0.090 (0.024, 0.155) | 0.013 (−0.111, 0.137) |

| 2008 | 0.180 (0.128, 0.232) | −0.029 (−0.098, 0.040) | 0.049 (0.025, 0.073) | −0.027 (−0.135, 0.081) |

| 2009 | 0.177 (0.131, 0.223) | −0.032 (−0.095, 0.032) | 0.052 (0.029, 0.075) | −0.024 (−0.132, 0.083) |

| 2010 | 0.056 (0.008, 0.103) | −0.153 (−0.218, −0.089) | 0.018 (−0.008, 0.044) | −0.058 (−0.167, 0.050) |

| 2012 | 0.095 (0.052, 0.137) | −0.114 (−0.175, −0.053) | 0.044 (−0.002, 0.089) | −0.033 (−0.147, 0.082) |

| 2013 | 0.108 (0.061, 0.154) | −0.101 (−0.165, −0.037) | 0.032 (−0.002, 0.066) | −0.044 (−0.155, 0.067) |

| 2014 | 0.044 (0.002, 0.085) | −0.165 (−0.226, −0.104) | 0.021 (−0.006, 0.047) | −0.056 (−0.164, 0.053) |

| 2015 | 0.028 (−0.012, 0.068) | −0.181 (−0.241, −0.121) | 0.008 (−0.011, 0.027) | −0.069 (−0.176, 0.038) |

| 2016 | 0.043 (0.009, 0.078) | −0.166 (−0.222, −0.110) | 0.016 (−0.001, 0.033) | −0.060 (−0.167, 0.047) |

| 2017 | 0.038 (0.003, 0.073) | −0.171 (−0.228, −0.115) | 0.018 (0.001, 0.036) | −0.058 (−0.165, 0.049) |

| 2018 | 0.032 (−0.01, 0.075) | −0.177 (−0.238, −0.115) | 0.024 (0.002, 0.045) | −0.052 (−0.160, 0.055) |

| Mean concentration index | 0.124 | — | 0.047 | — |

CI: confidence interval

aUnit change in comparison to baseline (year 1999).

Figure 2.

Rank-based vs level-based Concentration indices, Paraguayan Permanent Household Survey 1999 to 2018.

Figure 3.

Correlation between rank- and level-based Concentration indices, Paraguayan Permanent Household Survey 1999 to 2018.

We explored for potential heterogeneity in inequality trends by urbanicity, sex, and among older people. In general, trends were similar across urban and rural areas and across men and women, with some sharp increases in inequality during the mid-2000s for women and those ages 65 and more (see Online Supplement 1, Figures S2–S4).

Discussion

We found health care utilization in Paraguay between 1999 and 2018 was more concentrated among those with higher income, but the extent of these inequalities declined over time. Measured inequality can be better explained in terms of the disproportionality between the utilization rate in each income group and the proportion each income group represents in the population. 17 For example, in 1999, 24% of all those who used health services were from the lowest income group, a group that accounted for 29.4% of the population. Conversely, 14% of the total reported health care use was consumed by the highest income group, which was only 10% of the population. This disproportionality, more accentuated in the first years of the period, is not surprising considering low overall levels of health insurance coverage,18,19 high out-of-pocket health care expenditure2,4 and the existence of service fees within the MSPyBS network.1,2,7

Trends in inequality as expressed by both the rank- and level-based CIxs were generally stable from 1999 to 2009, with a noticeable decrease in 2010 and thereafter. From 1999 to 2009 utilization rates increased similarly for all income groups, leading to little change in observed inequality. The decrease in 2010 is mechanically explained by an increase in health care use in the lowest income group and a decrease for all other groups, narrowing the utilization gap between groups. From 2010 onwards, inequality remained lower relative to 1999 baseline levels due to both lower poverty rates and higher utilization rates among lower income groups.

The decline in inequality coincides with relevant policy changes, including the removal of user fees at the MSPyBS health care facilities, 20 the publicly financed provision of essential medicines and the strengthening of primary health care through the implementation of family health care units. 1 In addition, between 2009 and 2014, there was a slight increase in public expenditure in health as percentage of the GDP, and an increase in per capita public health expenditure. 21 Moreover, a conditional cash-transfer programme, ‘Tekopora’, which started as a pilot project in 2005 covering 4500 households in five districts across two departments, was gradually expanded up to more than 100,000 households in 130 districts across all 18 geographic regions in 2014. 22 Similar to other conditional cash-transfer programmes implemented in Latin America, this has been based on the transfer of cash to poor households conditional on meeting, among others, health care-related criteria such as growth and development control, pre-natal check-ups and following the children’s vaccination schedule. Thus, cash transfers and health care-related conditionalities could also have played a role in increasing utilization rates among poorer households. 23 All these strategies could potentially explain the increase in health care utilization among the lowest income groups, but rigorous analyses are needed to assess their impact on the access and use of health care in the country. Despite recent inequality reductions, utilization rates decreased for all income groups in the last years and future monitoring should assess the evolution of this indicator in conjunction with changes in poverty rates. This becomes especially relevant considering the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had, and is projected to have, on income distribution and health care systems response.24,25

Our estimates of inequality trends across selected sub-groups suggest some homogeneity in the trends and allow some generalizations. However, this is a first step in exploring subgroup inequalities. A natural extension of this work would be to conduct subgroup decompositions to estimate how inequalities are explained into between- and within-group inequality, 26 which would provide more elements for a better understanding of health care inequalities in the country.

Limitations

Our results should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. First, we measured inequality using the CIx, a summary measure of inequality that simplifies comparisons over several years and which is sensitive to changes in health care use and income distribution across the population. However, alternative summary measures could lead to different conclusions. 17 A variety of concentration indices have been proposed to suit different analytical decisions, including the type of socioeconomic weighting scheme, 13 the measurement properties of the variable in which inequality is to be assessed 14 and the normative principles concerning attitudes towards inequalities.27,28 Recently, level-based CIxs have been proposed as an alternative to rank-based indices. 14 Our analysis is based on the rank-and level-dependent concentration indices, both corrected to deal with binary outcomes.12,29 While the direction of inequality change was consistent across indices, the estimation of the magnitude of the decrease seems somewhat sensitive to the type of index used. This difference might be explained by the fact that rank-based indices only change when the rank of individuals change, a property that can make the index to change ‘spasmodically’ (e.g. in small jumps) rather than smoothly when changes in income distribution take place. 13 A second choice refers to the incorporation of some degree of inequality aversion in the weighting function. That is, whether to weight more (or less) the outcome among individuals across the income distribution (i.e. the incorporation of a ‘sensitivity to inequality’ parameter). We used the ‘basic’ version of the rank (level) based indices, which weight individuals as a linear function of their rank (level) in the income distribution, with a weight of zero for those with median (mean) income. Thus, weights are symmetrical, with individuals with incomes below the median (mean) receiving negative weights and those above the median (mean) receiving positive weights. A third relevant choice has to be made in the context of binary outcomes – such as health care use as measured in the EPH – and refers to satisfying what Erreygers coined as the ‘mirror’ condition (i.e. the absolute value of the index does not depend on whether we consider health care attainments or shortfalls) 12 or the invariance condition (i.e. invariance of the absolute index to equal changes in health care). We used indices which satisfy the first condition. In a sensitivity analysis, we estimated the standard (relative) CIx to see whether trends change when relative invariance is prioritized. We also estimated the Wagstaff’s corrected rank-based CIx 11 to assess whether our results were sensitive to the use of an alternative correction for bounded variables. Figure S5 (Online Supplement) shows similar trends, suggesting robustness of our main conclusions. One potential downside of using the concentration index, in any of its versions, is the lack of a straightforward interpretation, particularly when interpreting the estimated magnitude of inequality for each year. One way to interpret its magnitude is by comparing the estimated index relative to its potential maximum value, but it seems extreme to consider maximum inequality as a plausible bound.

Second, income level in our study was based on household reports, which tend to underestimate true income, especially in higher income groups. 30 This could lead to an underestimation of income inequality and therefore an underestimation of the computed inequality.

Third, information on utilization was collected exclusively on those participants who reported a health problem in the last 90 days. This, to some extent, adjusts health care use to need, but restrict the analysis to a subsample of adults. Furthermore, it assumes that a self-reported health problem in the last 3 months is a good indicator of health care need, which is not necessarily true. For one thing, a health problem of similar severity (i.e. need) could be differentially reported by income groups, thus leading to differential misclassification of the outcome. Moreover, the window of 3 months may not be sufficient to capture the need of care among people with poor health and much need, but who circumstantially did not experience a specific problem in that period (e.g. chronic patients, undiagnosed participants, etc.).

Fourth, a single question on utilization does not discriminate the type of service used, perceived quality, responsiveness and other relevant factors. Therefore, our estimations could be different if more detailed information were available. Considering the financing and delivery characteristics of the health care system as well as the levels of socioeconomic inequality, we expect the inclusion of more detailed information would lead to more accentuated inequality. This highlights the need to improve the measurement of health care utilization in future cycles of the EPH.

Conclusions

This is the first study to rigorously measure socioeconomic inequality in health care utilization at the national level in Paraguay. We took advantage of a survey programme that consistently measured income and utilization over 19 years and which is the most reliable source of national data. We accounted for changes in income-specific utilization rates and changes in income distribution. We expect these results will provide health care policy makers with useful information to better understand how socioeconomic inequalities in health care use has trended in Paraguay over recent decades.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-hsr-10.1177_13558196221079160 for Socioeconomic inequalities in health care utilization in Paraguay: Description of trends from 1999 to 2018 by Diego A Capurro and Sam Harper in Journal of Health Services Research & Policy

Acknowledgements

We thank Maria Lilia Robledo, researcher at the Institute of Social Sciences Paraguay, for her insights and inputs on relevant aspects of the social policy context in Paraguay.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Diego Capurro was funded by the Paraguayan Council for Science and Technology, CONACYT [Grant number: 14-INV-157].

Ethics approval: The present study used anonymized and publicly available survey data and therefore no specific ethical approval was needed. With regards to the EPH data collection, INE asserted all permissions, informed consent, and ethical requirements were met.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Diego A Capurro https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2426-3596

References

- 1.Instituto Suramericano de Gobierno en Salud . Sistemas de salud en Suramerica: desafios para la universalidad, la integralidad y la equidad. Sistema de salud en Paraguay. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: ISAGS, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benitez G. Distribucion del gasto en salud y gastos de bolsillo. Principales resultados. Asuncion, Paraguay: Centro de Analisis y Difusion de la Economia Paraguaya CADEP, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The World Health Organization . The World Health Report 2010. Health systems financing. The path to univeral coverage. Genveva, Switzerland: WHO, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The World Bank . The World Bank Data. Out-of-pocket Expenditure: Paraguay, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS?locations=PY (2020, accessed 9 September 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagstaff A. Poverty and health sector inequalities. Bull World Health Organ 2002; 80: 97–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almeida G, Dmytraczenko T. Toward universal health coverage and equity in Latin America and the Caribbean. evidence from selected countries. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banco Mundial. La volatilidad y la desigualdad como restricciones para la prosperidad compartida: Informe de equidad en Paraguay. Washington DC: Banco Mundial, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Direccion General de Encuestas Estadisticas . Encuesta Permanente de hogares 2015. Apecto metodológico. Asuncion, Paraguay: DGEEC, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas . Datos abiertos. Encuesta permanente de hogares, https://www.ine.gov.py/microdatos/microdatos.php (2019, accessed 17 September 2021).

- 10.Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E, Paci P. On the measurement of horizontal inequity in the delivery of health care. J Health Econ 1991; 10: 169–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagstaff A. The bounds of the concentration index when the variable of interest is binary, with an application to immunization inequality. Health Econ 2005; 14: 429–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erreygers G. Correcting the concentration index. J Health Econ 2009; 28: 504–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erreygers G, Kessels R. Socioeconomic status and health: a new approach to the measurement of bivariate inequality. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017; 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erreygers G, Van Ourti T. Measuring socioeconomic inequality in health, health care and health financing by means of rank-dependent indices: a recipe for good practice. J Health Econ 2011; 30: 685–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Donnell O, van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A. Analyzing health equity using household survey data: a guide to techniques and their implementation. Washington, DC: World Bank Institute, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capurro DA, Harper S. Socioeconomic inequalities in healthcare utilization in Paraguay: description of trends from 1999 to 2018. Replication file, https://osf.io/rhe97/ (2022, accessed 15 March 2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harper S, Lynch J. Commentary: Using innovative inequality measures in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 2007; 36: 926–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Organización Panamericana de la Salud . Hoja resumen sobre desigualdades en salud Paraguay. Washington, DC: OPS, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministerio de Salud Publica y Bienestar Social . Exclusion social en salud. Paraguay 2007. Asuncion, Paraguay: MSPyBS, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministerio de Salud Publica y Bienestar Social . Resolucion S.G. 1074/2009. Asuncion, Paraguay: MSPyBS, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.The World Bank . Health, nutrition and population statistics. Databank, http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=311#advancedDownloadOptions (2021, accessed 2 December 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministerio de Hacienda. Evaluacion de impacto del programa Tekopora. Informe final. Asuncion, Paraguay: Ministerio de Hacienda, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N. The impact of conditional cash transfers on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009: Cd008137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2020; 74: 964–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Litewka SG, Heitman E. Latin American healthcare systems in times of pandemic. Dev World Bioeth 2020; 20: 69–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erreygers G, Kessels R, Chen L, et al. Subgroup decomposability of income-related inequality of health, with an application to Australia. Econ Rec 2018; 94: 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harper S, King NB, Meersman SC, et al. Implicit value judgments in the measurement of health inequalities. Milbank Q 2010; 88: 4–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erreygers G, Clarke P, Van Ourti T. Mirror, mirror, on the wall, who in this land is fairest of all?” Distributional sensitivity in the measurement of socioeconomic inequality of health. J Health Econ 2012; 31: 257–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessels R, Erreygers G. A direct regression approach to decomposing socioeconomic inequality of health. Health Econ 2019; 28: 884–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amarante V. Income inequality in Latin America: data challenges and availability. Soc Indic Res 2014; 119: 1467–1483. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-hsr-10.1177_13558196221079160 for Socioeconomic inequalities in health care utilization in Paraguay: Description of trends from 1999 to 2018 by Diego A Capurro and Sam Harper in Journal of Health Services Research & Policy